Abstract

Background and purpose

Next‐generation sequencing has greatly improved the diagnostic success rates for genetic neuromuscular disorders (NMDs). Nevertheless, most patients still remain undiagnosed, and there is a need to maximize the diagnostic yield.

Methods

A retrospective study was conducted on 72 patients with NMDs who underwent exome sequencing (ES), partly followed by genotype‐guided diagnostic reassessment and secondary investigations. The diagnostic yields that would have been achieved by appropriately chosen narrow and comprehensive gene panels were also analysed.

Results

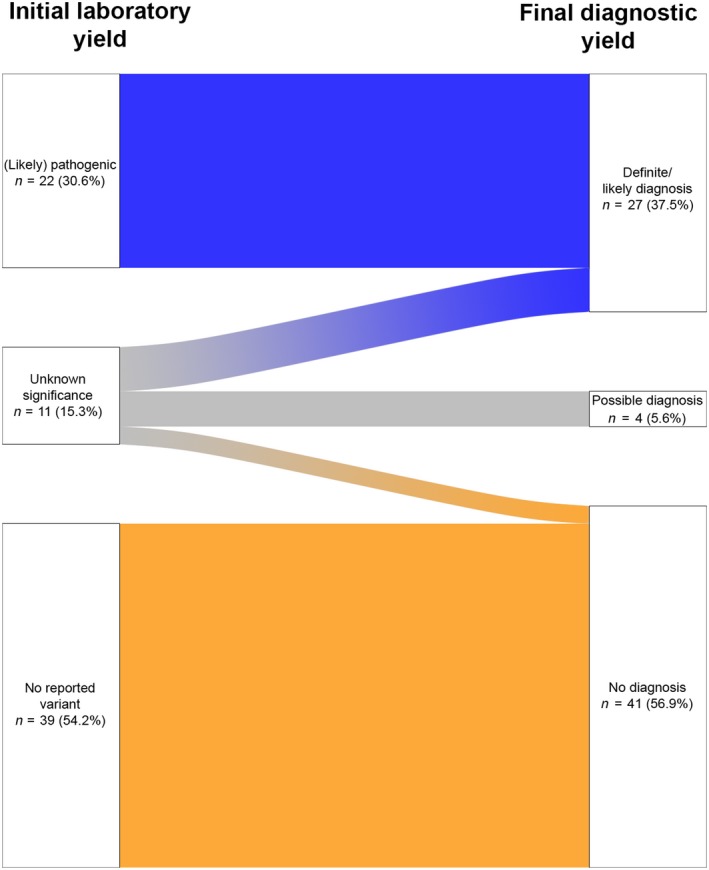

The initial diagnostic yield of ES was 30.6% (n = 22/72 patients). In an additional 15.3% of patients (n = 11/72) ES results were of unknown clinical significance. After genotype‐guided diagnostic reassessment and complementary investigations, the yield was increased to 37.5% (n = 27/72). Compared to ES, targeted gene panels (<25 kilobases) reached a diagnostic yield of 22.2% (n = 16/72), whereas comprehensive gene panels achieved 34.7% (n = 25/72).

Conclusion

Exome sequencing allows the detection of pathogenic variants missed by (narrowly) targeted gene panel approaches. Diagnostic reassessment after genetic testing further enhances the diagnostic outcomes for NMDs.

Keywords: diagnostic reassessment, diagnostic yield, exome sequencing, gene panels, neuromuscular disorders, next‐generation sequencing

Introduction

Neuromuscular disorders (NMDs) represent a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of diseases affecting motor neurons, peripheral nerves, the neuromuscular junction or muscle tissue, often with an overlapping range of symptoms. A considerable proportion of NMDs are known or suspected to have a monogenic aetiology. However, due to the marked phenotypic overlap and the contribution of as yet unidentified disease genes, single gene testing has been widely unsuccessful.

With the advent of next‐generation sequencing (NGS) approaches such as gene panels, exome sequencing (ES) or genome sequencing, a growing number of causative variants can be identified 1, 2, 3. Even so, the majority of patients with NMDs still remain undiagnosed with variable success rates, mainly depending on the selected patient population and the applied method 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12. It is therefore a major challenge facing clinicians and geneticists to further enhance the application of NGS techniques.

For example, it is a subject of ongoing debate which exact NGS approach is optimal from a diagnostic and cost‐point perspective 13. ES has the inherent potential to identify novel disease genes and allows a diagnostic re‐evaluation at a later time, whereas gene panels are postulated to secure a higher coverage. The diagnostic utility of comprehensive panels and ES has been considered to be comparable in practice 14, 15. In contrast, it is still unclear whether the widely used small‐scale panels – as often mandated by national health care providers – achieve similar results.

Another issue requiring refinement is the correct identification of causative variants against the abundance of irrelevant background variation. The widely used guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) consider various strands of genetic and clinical evidence for variant classification 16. Whilst some variants can reliably be classified as benign or pathogenic right away, the causative effect often remains uncertain after genetic testing (variants of unknown significance, VUS) 17. It has already been shown that uncertain findings can be successfully reclassified using clinical reconsideration, complementary family genotyping or supporting functional data 18, 19, 20. Such approaches have the ability to reveal minor and initially overlooked clinical features, bringing to light specific phenotypic fits potentially underpinning the pathogenic relevance of variants.

In this retrospective analysis of routine ES in patients with NMDs, an evaluation was made of the degree to which a critical reassessment after ES may enhance the diagnostic outcomes in a real‐world setting. Secondly, diagnostic ES was virtually compared to frequently used NGS gene panels.

Methods

Patients

All patients with neuromuscular phenotypes seen at the Department of Neurology (Medical University of Vienna, Austria) who underwent diagnostic ES between July 2015 and December 2018 were retrospectively selected. The indication was determined after reviewing and complementing prior diagnostic procedures. A genetic aetiology was considered by NMD specialists, if no acquired cause could be established after an extensive diagnostic work‐up.

Informed consent (also regarding actionable findings) was obtained from included patients. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna.

Exome sequencing and data analysis

Exomes were enriched in solution with SureSelect Human All Exon Kits 50 Mb V5 and 60 Mb V6 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). DNA fragments were sequenced as 100 bp paired‐end runs on an Illumina HiSeq2500 or HiSeq4000 system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The mean average coverage in our exome dataset was 146.8×.

Variants were filtered based on the minor allele frequency (MAF), which was estimated using our in‐house database (>15 000 exomes) and confirmed by ExAC, (https://exac.broadinstitute.org) or gnomAD, (https://gnomAD.broadinstitute.org). Variant prioritization was based on autosomal recessive (MAF < 0.1%) and autosomal dominant (MAF < 0.01%) filters. Copy number variation analysis was done using ExomeDepth 21 and Pindel 22. A detailed description of the sequencing and data analysis pipeline is provided as supplementary file (Data S1).

Variant interpretation by genetic laboratory

Using ACMG criteria, variants were classified as (i) pathogenic, (ii) likely pathogenic or (iii) VUS 16. VUS that were not related to the phenotype in question and (likely) benign variants were not reported. (Likely) pathogenic variants were considered sufficient for establishing a genetic diagnosis for dominant disorders. For recessive disorders, two (likely) pathogenic variants were required. Otherwise, for example in the case of one pathogenic variant and one VUS, the laboratory conclusion was considered of ‘unknown clinical significance’. Exomes were screened for actionable variants as recommended by ACMG 23. At the time of initial analysis, basic clinical information was available for geneticists.

Diagnostic reassessment and variant reclassification

After ES, all (likely) pathogenic variants were considered causative, if compatible with the inheritance pattern and phenotype (definite/likely diagnoses). VUS in genes related to the NMD phenotype guided diagnostic reassessment with the aim of clarifying their clinical relevance. Investigations such as family genotyping, histology or biochemical analyses were initiated. Existing literature on previously reported families with mutations in the same gene was specifically screened to compare the phenotypes with our index cases. After reassessment, VUS were re‐evaluated and partly reclassified according to ACMG 16. Since ACMG only provides categories for variants, the following categories were additionally defined to provide patients with a firm diagnostic conclusion (as suggested by Shashi et al. 19): (i) definite diagnosis (one pathogenic variant for dominant and two pathogenic variants for recessive disorders), (ii) probable diagnosis (one likely pathogenic variant for dominant and at least two likely pathogenic variants for recessive disorders), (iii) possible diagnosis (one VUS for dominant and either one VUS and one (likely) pathogenic variant or two VUS for recessive disorders) and (iv) no diagnosis. Final decisions were made after an interdisciplinary discussion involving NMD specialists and a geneticist.

Comparison of exome sequencing to gene panels

To virtually compare the diagnostic yields between gene panels and ES, one commercially available targeted panel comprising less than 25 kilobases (kb) that seemed most appropriate for each individual phenotype (4–17 genes) and one comprehensive NGS panel (up to 344 genes) were retrospectively selected. The diagnostic yields of both selected panels were compared to the outcome of ES (Table S1).

Results

Patient characteristics

In all, 72 patients with neuromuscular phenotypes underwent diagnostic ES between July 2015 and December 2018 and were selected for analysis.

The median age at the time of ES was 47 years (range 19–78 years). 54.2% of all patients (n = 39) were male; 45.8% (n = 33) were female. In 30.6% (n = 22) a positive family history for the disease or a similar disease phenotype was reported. The median age at disease onset was 30 years (range 0–74 years). In 41.7% (n = 30) either the muscle or the neuromuscular junction was the predominant lesion site; 40.3% (n = 29) exhibited a more complex phenotype involving anterior horn cells or motor neurons, and 18.1% (n = 13) displayed a peripheral nerve disorder.

Molecular diagnoses

The initial diagnostic yield according to the laboratory reports was 30.6% (n = 22/72 patients). In addition, for 11 patients (15.3% of the cohort), 12 VUS in 11 different genes were reported to be potentially associated with the phenotype. After genotype‐guided diagnostic reassessment and additional investigations, the final diagnostic yield was increased to 37.5% (n = 27/72 patients). In 39 individuals (54.2%) no relevant variants were identified. The main characteristics of patients with the reported variants are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and genetic characteristics of all patients with reported variants after ES

| Patient ID | Sex | Clinical diagnosis | Age at ES (years) | Gene(s)/variant(s) | Inheritance pattern | OMIM diagnosis (#MIM) | Laboratory ACMG variant classification | Diagnostic reassessment | Final ACMG variant classification | Final diagnostic conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Female | Myasthenic syndrome | 26 |

CHRNE (hom) c.1327del, p.E443Kfs*64 |

AR | CMS4C (#608931) | Pathogenic | N.A. | Pathogenic | Definite diagnosis |

| 4 | Female | Limb girdle muscular dystrophy | 45 |

SGCA (comp het) c.229C>T, p.R77C c.739G>A, p.V247M |

AR | LGMD2D (#608099) |

Pathogenic Pathogenic |

N.A. |

Pathogenic Pathogenic |

Definite diagnosis |

| 6 | Female | Cardiomyopathy, skeletal myopathy | 32 |

RBCK1 (hom) c.896_899del, p.E299Vfs*46 |

AR | PGBM1 (#615895) | Pathogenic | Literature search, immune phenotyping | Pathogenic | Definite diagnosis |

| 8 | Female | Spastic paraparesis | 55 |

SPG7 (hom) c.233T>A, p.L78* |

AR | SPG7 (#607259) | Pathogenic | N.A. | Pathogenic | Definite diagnosis |

| 9 | Male | Limb girdle muscular dystrophy and myotonia | 49 |

DMD (hem) NM_000109.3: deletion of exons 48 and 49 SCN4A (het) c.3386G>A, p.R1129Q |

DP |

BMD (#300376) HOKPP2 (#613345) |

Pathogenic Likely pathogenic |

N.A. |

Pathogenic Likely pathogenic |

Likely diagnosis (dual pathology) |

| 10 | Male | Upper and lower motor neuron disease | 47 |

DNM2 (het) c.1493A>C, p.N498T |

AD | CMTDIB (#606482) | VUS | Family genotyping (including trio ES) | VUS | No diagnosis |

| 11 | Male | Spastic paraparesis, neuropathy | 19 |

MFN2 (het) c.1252C>T, p.R418* |

AD | CMT2A2A (#609260) | Pathogenic | Re‐phenotyping (rare association between MFN2 and spasticity described), NCS compatible | Pathogenic | Definite diagnosis |

| 12 | Female | Spastic paraparesis | 55 |

SPAST (het) NM_014946.3:c.1493 + 2_1493 + 5del, p.(?) |

AD | SPG4 (#182601) | Pathogenic | N.A. | Pathogenic | Definite diagnosis |

| 13 | Female | External ophthalmoplegia, ptosis | 25 |

CHRNE (hom) c.1327del, p.E443Kfs*64 |

AR | CMS4C (#608931) | Pathogenic | N.A. | Pathogenic | Definite diagnosis |

| 17 | Female | Lower limb‐predominant muscular atrophy | 33 |

BICD2 (het) c.1673G>C, p.R558P |

AD | SMALED2 (#615290) | VUS | Re‐phenotyping (specific phenotype fit, predominant affection of lower limbs) | Likely pathogenic | Likely diagnosis |

| 19 | Female | Limb girdle muscular dystrophy | 36 |

CAPN3 (comp het) c.1342C>T, p.R448C c.1722del, p.S575Lfs*20 |

AR | LGMD2A (#253600) |

Likely pathogenic Pathogenic |

N.A. |

Likely pathogenic Pathogenic |

Likely diagnosis |

| 22 | Male | Spastic paraparesis | 63 |

SPG7 (hom) c.1552 + 1G>T, p.(?) |

AR | SPG7 (#607259) | Pathogenic | Family genotyping (affected brother with same homozygous variant) | Pathogenic | Definite diagnosis |

| 25 | Male | Spastic paraparesis | 62 |

SPG7 (hom) 2:c.233T>A, p.L78* |

AR | SPG7 (#607259) | Pathogenic | N.A. | Pathogenic | Definite diagnosis |

| 27 | Male | Lower limb predominant myopathy, dysarthria, dysphagia | 62 |

PABPN1 (het) c.19_2(4), p.A7(4) |

AD | OPMD (#164300) | Pathogenic | N.A. | Pathogenic | Definite diagnosis |

| 30 | Female | Polyneuropathy | 33 |

MARS (het) c.181_183del, p.S61del HARS (het) c.1488G>T, E496D |

AD AD |

CMT2U (#616280) CMT2W (#616625) |

VUS VUS |

Family genotyping (unaffected mother and sister) |

VUS VUS |

Possible diagnosis |

| 32 | Female | Lower limb predominant myopathy | 28 |

TTN (comp het) c.96697C>T, p.R32233* c.107578C>T, p.Q35860* |

AR | LGMD2J (#608807) |

Pathogenic Pathogenic |

Family genotyping (confirming biallelic location) |

Pathogenic Pathogenic |

Definite diagnosis |

| 35 | Male | Spastic paraparesis, mild cerebellar atrophy | 38 |

FA2H (comp het) c.968C>T, p.P323L c.1119A>T, p.*373Cext*48 |

AR | SPG35 (#612319) |

Likely pathogenic Likely pathogenic |

N.A. |

Likely pathogenic Pathogenic |

Likely diagnosis |

| 38 | Male | Lower motor neuron disease | 52 |

TRPV4 (het) c.935C>T, p.A312V |

AD |

SPSMA (#181405) HMN8 (#600175) |

VUS | Literature search (fitting phenotype, early respiratory involvement) | Likely pathogenic | Likely diagnosis |

| 39 | Female | Proximal myopathy, vertical gaze palsy | 48 |

RYR1 (comp het) c.14647‐3_14647del, p.(?) c.4405C>T, p.R1469W |

AR | Minicore myopathy (#255320) |

Likely pathogenic VUS |

Muscle biopsy (specificity of phenotype) |

Likely pathogenic Likely pathogenic |

Likely diagnosis |

| 40 | Male | Inclusion body myopathy | 70 |

MYOT (het) c.179C>T, p.S60F |

AD | MFM3 (#609200) | Likely pathogenic | N.A. | Likely pathogenic | Likely diagnosis |

| 41 | Male | Proximal myopathy | 52 |

MYH2 (het) c.1267G>A, p.V423M |

AD/AR | MYPOP (#605637) | VUS | Muscle biopsy/histology | VUS | Possible diagnosis |

| 44 | Female | Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy | 29 |

SMCHD1 (het) c.2510T>C, p.V837A |

Digenic | FSHD2 (#158901) | VUS | D4Z4 methylation status (normal) | VUS | No diagnosis |

| 50 | Female | Spastic paraparesis, polyneuropathy | 38 |

KIF1A (comp het) c.2909G>A, p.R970H c.1214_1215dup, p.N405fs*1 |

AR | SPG30 (#610357) |

VUS Pathogenic |

Segregation analysis, specific phenotype |

Likely pathogenic Pathogenic |

Likely diagnosis |

| 52 | Male | Polyneuropathy | 72 |

PMP22 (het) 1.5 Mb deletion Chr17:14,075,320‐15,472,674 |

AD | HNPP (#162500) | Pathogenic | Duo ES analysis (including affected daughter) | Pathogenic | Definite diagnosis |

| 53 | Male | Spastic paraparesis | 57 |

SPAST (het) c.1553T>C, p.L518P |

AD | SPG4 (#182601) | Likely pathogenic | N.A. | Likely pathogenic | Likely diagnosis |

| 54 | Female | Intermittent rhabdomyolysis | 35 |

CPT2 (hom) c.338C>T, p.S113L |

AR | CPT II deficiency, myopathic (#255110) | Pathogenic | N.A. | Pathogenic | Definite diagnosis |

| 56 | Female | Spastic paraparesis | 50 |

CYP7B1 (comp het) c.825T>A, p.Y275* c.1091C>T, p.S364L |

AR | SPG5A (#270800) |

Pathogenic VUS |

Biochemical analysis (elevated plasma 27‐hydroxycholesterol) |

Pathogenic Likely pathogenic |

Likely diagnosis |

| 57 | Male | Motor neuron disease | 71 |

TRPV4 (het) c.664A>G, p.N222D |

AD |

SPSMA (#181405) HMN8 (#600175) |

VUS | N.A. | VUS | Possible diagnosis |

| 59 | Female | Polyneuropathy, action‐induced myoclonus | 23 |

SCARB2 (hom) c.134del, p.N45Mfs*54 |

AR | EPM4 (#254900) | Pathogenic | Epilepsy monitoring, assessment of renal function (mild proteinuria) | Pathogenic | Definite diagnosis |

| 67 | Male | Distal myopathy | 65 |

HNRNPA1 (het) c.1064‐12_1086del |

AD | IBMPFD3 (#615424) | VUS | N.A. | VUS | Possible diagnosis |

| 68 | Female | Spastic paraparesis, ataxia | 63 |

SPG11 (hom) c.5381T>C, p.L1794P |

AR | SPG11 (#604360) | Pathogenic | N.A. | Pathogenic | Definite diagnosis |

| 69 | Female | Sensorimotor polyneuropathy | 26 |

GDAP1 (hom) c.349dup, p.Y117Lfs*13 |

AR | CMTRIA (#608340) | Pathogenic | N.A. | Pathogenic | Definite diagnosis |

| 70 | Female | Spinal muscular atrophy | 45 |

DYSF (hom) c.5302C>T, p.R1768W |

AR | LGMDR2 (#253601) | Pathogenic | Muscle biopsy due | Pathogenic | Definite diagnosis |

ACMG, American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics; AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; comp het, compound heterozygous; DP, dual pathology; ES, exome sequencing; hem, hemizygous; het, heterozygous; hom, homozygous; N.A., not applicable; NCS, nerve conduction studies; OMIM, Online Mendelian Inheritance of Man; VUS, variant of unknown significance.

Eighteen of 27 patients (66.7%) with a genetic diagnosis after reassessment had an autosomal recessive disorder and eight (29.6%) an autosomal dominant disorder. In one patient (3.7%) a dual pathology involving DMD (hemizygous two exon deletion) and SCN4A (heterozygous missense variant) was diagnosed.

Overall, a total of 24 different OMIM (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man) diagnoses could be established. SPG7 (MIM#607259) was represented three times and SPG4 (MIM#182601) and CMS4C (MIM#608931) were each represented twice in this cohort. Each of the remaining 21 diagnoses was represented once.

Genotype‐guided diagnostic reassessment and variant reclassification

After diagnostic reassessment, the results of unknown clinical significance were reconsidered to be (probably) disease‐related in five of 11 patients (Fig. 1, Table S2). In three of these five patients, this was due to specific phenotype features revealed in a second diagnostic step, e.g. muscle histology (ACMG criterion PP4), segregation analysis (ACMG criteria PM3 + PP1) and biochemical (functional) confirmation of pathogenicity (ACMG criterion PS3). One VUS in DNM2 was not considered disease‐related due to the carriership of an unaffected parent, and another patient carrying a VUS in SMCHD1 showed normal D4Z4 methylation (no diagnosis). In the remaining four patients with reported VUS, pathogenicity remained uncertain after diagnostic reassessment (possible diagnosis).

Figure 1.

Comparison of diagnostic ES conclusion according to the genetic laboratory (left) with the final yield after genotype‐guided diagnostic reassessment (right).

As an example, a VUS in BICD2 (patient 17) led to an extensive review of the literature by the treating clinicians. Although family genotyping could not be done, previously reported families with missense variants in BICD2 were strikingly reminiscent of the patient's specific clinical presentation (lower motor neuron disease, areflexia and marked predominance of lower limbs), and so the variant was upgraded to ‘likely pathogenic’ (likely diagnosis). Similarly, a VUS in TRPV4 (affecting a functional protein domain) was also upgraded to ‘likely pathogenic’ due to a highly specific phenotypic fit in patient 38 (lower motor neuron disease, vocal cord palsy and early respiratory involvement). One VUS in the RYR1 gene (which coexisted with one likely pathogenic variant in the same gene) in patient 39 could be changed to ‘likely pathogenic’ based on the specific features of a secondarily performed muscle biopsy, supporting RYR1‐related myopathy. Patient 50 with spastic paraparesis carried one VUS (along with one pathogenic variant) in KIF1A. After ES, these variants were shown to segregate with the phenotype in two affected out of four siblings, leading to the (likely) diagnosis of SPG30. A heterozygous carriership was confirmed in both unaffected parents. Another patient with spastic paraparesis (patient 56) had one VUS in CYP7B1 (along with a pathogenic variant). A biochemical analysis of serum 27‐hydroxycholesterol levels led to an upgrade to ‘likely pathogenic’, confirming SPG5A.

Comparison of ES to gene panels

Simulated targeted gene panels (<25 kb) included the underlying gene in 16/27 patients diagnosed by ES, leading to a diagnostic yield of 22.2%. In contrast, comprehensive gene panels would have covered the causative gene in 25/27 cases resolved by ES, resulting in a yield of 34.7%. Two patients would not have been diagnosed with either gene panel due to atypical disease manifestations which would have led to the selection of a wrong panel. Patient 11 carrying a mutation in the polyneuropathy gene MFN2 could only be diagnosed with ES because of spastic paraparesis being the leading phenotype. Another patient (patient 59) with a predominant polyneuropathy phenotype and action‐induced myoclonus was eventually diagnosed with progressive myoclonic epilepsy due to biallelic pathogenic variants in SCARB2 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of ES to a targeted gene panel (<25 kb) and a comprehensive panel in all patients with a final diagnosis

| Patient ID | Gene | Selected targeted panel (<25 kb) | Selected comprehensive panel | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | CHRNE | CMS (13 genes) | NMD (344 genes) | Targeted and comprehensive |

| 4 | SGCA | LGMD (14 genes) | NMD (344 genes) | Targeted and comprehensive |

| 6 | RBCK1 | LGMD (14 genes) | NMD (344 genes) | Comprehensive only |

| 8 | SPG7 | HSP (9 genes) | HSP (56 genes) | Targeted and comprehensive |

| 9 | DMD, SCN4A | LGMD (14 genes) | NMD (344 genes) | Comprehensive only |

| 11 | MFN2 | HSP (9 genes) | HSP (56 genes) | None |

| 12 | SPAST | HSP (9 genes) | HSP (56 genes) | Targeted and comprehensive |

| 13 | CHRNE | CPEO (17 genes) | NMD (344 genes) | Comprehensive only |

| 17 | BICD2 | Infantile SMA (10 genes) | NMD (344 genes) | Targeted and comprehensive |

| 19 | CAPN3 | LGMD (14 genes) | NMD (344 genes) | Targeted and comprehensive |

| 22 | SPG7 | HSP (9 genes) | HSP (56 genes) | Targeted and comprehensive |

| 25 | SPG7 | HSP (9 genes) | HSP (56 genes) | Targeted and comprehensive |

| 27 | PABPN1 | Adult SMA (14 genes) | NMD (344 genes) | Comprehensive only |

| 32 | TTN | Distal myopathies (10 genes) | NMD (344 genes) | Comprehensive only |

| 35 | FA2H | HSP (9 genes) | HSP (56 genes) | Targeted and comprehensive |

| 38 | TRPV4 | Adult SMA (14 genes) | NMD (344 genes) | Comprehensive only |

| 39 | RYR1 | Congenital myopathies (7 genes) | NMD (344 genes) | Targeted and comprehensive |

| 40 | MYOT | IBM (4 genes) | NMD (344 genes) | Comprehensive only |

| 50 | KIF1A | HSP (9 genes) | HSP (56 genes) | Comprehensive only |

| 52 | PMP22 | Inherited neuropathies (14 genes) | NMD (344 genes) | Targeted and comprehensive |

| 53 | SPAST | HSP (9 genes) | NMD (344 genes) | Targeted and comprehensive |

| 54 | CPT2 | Metabolic myopathies (17 genes) | NMD (344 genes) | Targeted and comprehensive |

| 56 | CYP7B1 | HSP (9 genes) | HSP (56 genes) | Targeted and comprehensive |

| 59 | SCARB2 | Inherited neuropathies (14 genes) | NMD (344 genes) | None |

| 68 | SPG11 | HSP (9 genes) | HSP (56 genes) | Targeted and comprehensive |

| 69 | GDAP1 | Inherited neuropathies (14 genes) | NMD (344 genes) | Targeted and comprehensive |

| 70 | DYSF | Adult SMA (14 genes) | NMD (344 genes) | Comprehensive only |

CMS, congenital myasthenic syndrome; CPEO, chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia; HSP, hereditary spastic paraplegia; IBM, inclusion body myopathy; LGMD, limb girdle muscular dystrophy; NMD, neuromuscular disorder; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy.

Actionable variants

In our cohort of 72 individuals, an actionable variant was reported in one male patient aged 52 years (1.4%). The mutation in BRCA2 (NM_000059.3:c.5073dup) was considered pathogenic according to ClinVar, (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar).

Discussion

Several studies have stressed the importance of a critical reconsideration of initial genetic laboratory results from a clinical perspective 19, 20. Diagnostic reassessment approaches after NGS testing are increasingly entering medical practice, since ACMG recommends not using VUS for clinical decision‐making 16.

In our study, data are provided that argue in favour of such an approach. The diagnostic yield of ES in our cohort of 72 patients with NMDs was 30.6% based on the initial laboratory reports. This number could be increased to 37.5% after genotype‐guided diagnostic reassessment and conducting further investigations. Evidence that led to an upgrading of VUS was either derived from additional histological, biochemical or segregation analysis or by reassessing phenotypes in comparison with families from the literature. This was the case for two of our patients (with variants in BICD2 and TRPV4), whose phenotypic overlap with previously reported patients was so specific that the reported VUS were eventually considered likely pathogenic. As exemplified by these two patients, genotype‐guided secondary phenotyping makes sense, as it might reveal highly specific but initially overlooked clinical features. However, one has to be aware that this approach harbours the danger of a biased reassessment, especially if done by the treating clinician alone. Any decisions regarding variant reclassification should therefore be discussed by a multidisciplinary team to minimize this risk.

Our study also adds data for the discussion whether a targeted or an exome‐based NGS approach is most appropriate for routine diagnostics. Whilst comprehensive gene panels seem to offer yields similar to ES, it is questionable how well narrow gene panels perform in clinical practice (some health insurance companies, e.g. in Germany, set a limit of 25 kb) 5. This point is particularly relevant for ambiguous phenotypes as often observed in NMDs, easily leading to a wrong panel selection.

In our cohort, a considerable proportion of patients exhibited such complex phenotypes with overlapping symptoms between various neuromuscular disease subgroups (and thus panels). For instance, in patient 11, the clinically leading feature was spastic paraparesis. ES revealed a pathogenic variant in the ‘polyneuropathy gene’ MFN2, a gene which has been associated with an additional spasticity in rare cases 24. The usually prominent polyneuropathy phenotype was clinically not noticeable and only in retrospect evident in nerve conduction studies. Another patient (patient 59) clinically presented with a demyelinating polyneuropathy and action‐induced myoclonus. ES was performed due to the complex, syndromic phenotype and surprisingly revealed a clearly pathogenic homozygous mutation in SCARB2, a gene that is usually associated with progressive myoclonic epilepsy. Subsequently, the condition could be stabilized by antiepileptic treatment with levetiracetam. The association between SCARB2 and a polyneuropathy phenotype is rare but has already been described as part of the clinical spectrum 25.

Our analysis demonstrated that appropriately chosen simulated gene panels <25 kb would have covered only 59.3% of the responsible disease genes detected by ES. More comprehensive panels expectedly achieved a higher diagnostic yield, covering 92.6% of the detected genes. However, the two aforementioned cases resolved by ES would have been missed even by the comprehensive gene panel.

In conclusion, our analysis supports a systematic genotype‐guided diagnostic reassessment after NGS in a multidisciplinary setting involving referring clinicians and geneticists. Our data further argue against the use of narrowly targeted gene panels in NMDs due to ambiguously overlapping phenotypes.

Disclosure of conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest related to this article.

Supporting information

Table S1. Genes included in targeted and comprehensive panels.

Table S2. Basis on which VUS were upgraded after diagnostic reassessment according to ACMG.

Data S1. Supplementary methods. Detailed description of sequencing and data analysis pipeline.

Acknowledgements

MK wants to thank the Austrian Society of Neurology (ÖGN) and the Austrian Society of Epileptology (ÖGfE) that supported him with research fellowships. The authors did not receive any funding for this study.

References

- 1. Yang Y, Muzny DM, Reid JG, et al Clinical whole‐exome sequencing for the diagnosis of Mendelian disorders. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 1502–1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee H, Deignan JL, Dorrani N, et al Clinical exome sequencing for genetic identification of rare Mendelian disorders. JAMA 2014; 312: 1880–1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yavarna T, Al‐Dewik N, Al‐Mureikhi M, et al High diagnostic yield of clinical exome sequencing in Middle Eastern patients with Mendelian disorders. Hum Genet 2015; 134: 967–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chae JH, Vasta V, Cho A, et al Utility of next generation sequencing in genetic diagnosis of early onset neuromuscular disorders. J Med Genet 2015; 52: 208–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ankala A, da Silva C, Gualandi F, et al A comprehensive genomic approach for neuromuscular diseases gives a high diagnostic yield. Ann Neurol 2014; 77: 206–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tian X, Liang WC, Feng Y, et al Expanding genotype/phenotype of neuromuscular diseases by comprehensive target capture/NGS. Neurol Genet 2015; 1: e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gorokhova S, Cerino M, Mathieu Y, et al Comparing targeted exome and whole exome approaches for genetic diagnosis of neuromuscular disorders. Appl Transl Genom 2015; 7: 26–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haskell GT, Adams MC, Fan Z, et al Diagnostic utility of exome sequencing in the evaluation of neuromuscular disorders. Neurol Genet 2018; 4: e212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fattahi Z, Kalhor Z, Fadaee M, et al Improved diagnostic yield of neuromuscular disorders applying clinical exome sequencing in patients arising from a consanguineous population. Clin Genet 2016; 91: 1–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ghaoui R, Cooper ST, Lek M, et al Use of whole‐exome sequencing for diagnosis of limb‐girdle muscular dystrophy. JAMA Neurol 2015; 72: 1424–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Klein CJ, Middha S, Duan X, et al Application of whole exome sequencing in undiagnosed inherited polyneuropathies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014; 85: 1265–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Evilä A, Arumilli M, Udd B, Hackman P. Targeted next‐generation sequencing assay for detection of mutations in primary myopathies. Neuromuscul Disord 2016; 26: 7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schofield D, Alam K, Douglas L, et al Cost‐effectiveness of massively parallel sequencing for diagnosis of paediatric muscle diseases. NPJ Genom Med 2017; 2: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Volk AE, Kubisch C. The rapid evolution of molecular genetic diagnostics in neuromuscular diseases. Curr Opin Neurol 2017; 30: 523–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. LaDuca H, Farwell KD, Vuong H, et al Exome sequencing covers >98% of mutations identified on targeted next generation sequencing panels. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0170843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 2015; 17: 405–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Petersen B‐S, Fredrich B, Hoeppner MP, Ellinghaus D, Franke A. Opportunities and challenges of whole‐genome and ‐exome sequencing. BMC Genet 2017; 18: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tsai GJ, Rañola JMO, Smith C, et al Outcomes of 92 patient‐driven family studies for reclassification of variants of uncertain significance. Genet Med 2018; 22: 925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shashi V, McConkie‐Rosell A, Schoch K, et al Practical considerations in the clinical application of whole‐exome sequencing. Clin Genet 2015; 89: 173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baldridge D, Heeley J, Vineyard M, et al The Exome Clinic and the role of medical genetics expertise in the interpretation of exome sequencing results. Genet Med 2017; 19: 1040–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Plagnol V, Curtis J, Epstein M, et al A robust model for read count data in exome sequencing experiments and implications for copy number variant calling. Bioinformatics 2012; 28: 2747–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ye K, Schulz MH, Long Q, et al Pindel: a pattern growth approach to detect break points of large deletions and medium sized insertions from paired-end short reads. Bioinformatics 2009; 25: 2865–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Green RC, Berg JS, Grody WW, et al ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet Med 2013; 15: 565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Del Bo R, Moggio M, Rango M, et al Mutated mitofusin 2 presents with intrafamilial variability and brain mitochondrial dysfunction. Neurology 2008; 71: 1959–1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dibbens LM, Karakis I, Bayly MA, Costello DJ, Cole AJ, Berkovic SF. Mutation of SCARB2 in a patient with progressive myoclonus epilepsy and demyelinating peripheral neuropathy. Arch Neurol 2011; 68: 812–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Genes included in targeted and comprehensive panels.

Table S2. Basis on which VUS were upgraded after diagnostic reassessment according to ACMG.

Data S1. Supplementary methods. Detailed description of sequencing and data analysis pipeline.