The RASopathies are developmental syndromes caused by germline gain-of-function mutations in genes of the RAS/MAPK signalling pathway. RIT1 mutations are particularly associated with cardiovascular disease, including hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) distinct from that seen in sarcomeric mutations. Here, we report two patients with severe, early-onset HCM caused by RIT1 mutations, who responded well to MEK inhibition.

Patient 1: At 33 weeks of gestation, fetal echocardiogram revealed dysplasia of all four valves as well as mild polyhydramnios. Three weeks later, HCM and sub-pulmonary stenosis developed. Postnatal examination showed macrosomia, hypertelorism, and low-set ears. Neonatal echocardiography confirmed prenatal findings. Propranolol was introduced (up to 9 mg/kg/day). A NS gene panel revealed a heterozygous RIT1 c.104G>C; p.Ser35Thr (reference transcript: NM_006912.5) de novo mutation. Despite high-dose propranolol, we observed progression of HCM.

Patient 2: At 13 weeks of pregnancy, increased nuchal translucency was diagnosed. Gestational diabetes and polyhydramnios developed at 24 weeks. Fetal echocardiography was normal. Postnatally, she required mechanical ventilation for 10 days, thereafter continuous noninvasive ventilation. Clinical examination showed hypertelorism and low-set ears. Genetic testing revealed a heterozygous RIT1 c.246T>G, p.Phe82Leu de novo mutation. Echocardiography showed progressive biventricular hypertrophy and subvalvular obstruction. Propranolol was started (up to 10 mg/kg/day). Chest X-rays revealed progressive pulmonary congestion. Cardiac catheterization at the age of 2 months revealed postcapillary pulmonary hypertension. An attempt to relieve concomitant pulmonary stenosis by balloon valvuloplasty remained unsuccessful. Clinical deterioration at the age of 3 months required resuscitation, mechanical ventilation and pleural tubes for drainage of bilateral chylothoraces.

We discussed therapeutic options including heart transplantation and opted for off-label pharmacological MEK inhibition. We chose to seek approval from local ethics boards and obtained informed consent. We started trametinib, funded through the patients’ insurance, at 14 and 13 weeks of age for patients 1 (0.02 mg/kg/d) and 2 (0.027 mg/kg/d), respectively.

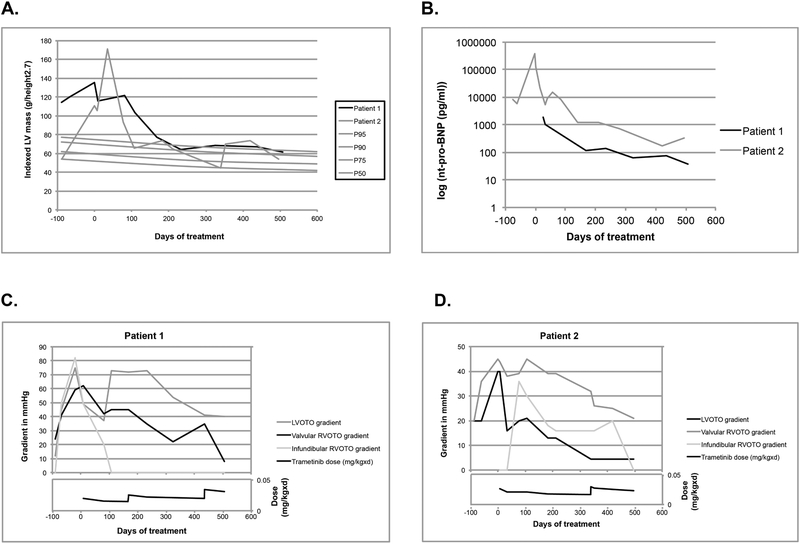

After three months of treatment, we observed dramatic improvement of clinical and cardiac status (Table 1). Hypertrophy regressed in both patients, with sustained improvement over a total of 17 months of treatment, and normalization of nt-pro-BNP. In patient 2, cardiac hypertrophy and pulmonary edema regressed, allowing extubation at 18 weeks of age. MRI confirmed echocardiographic findings after 3½ months of treatment. Valvular and subvalvular obstruction improved. Both patients showed better growth after treatment initiation.

Table 1:

Evolution of clinical and echocardiographic parameters at birth, at start of therapy and at 3½ and 17 months follow up. (4)

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At birth (38 weeks) | At start of therapy | After 3½ months of therapy | After 17 months of therapy | At birth (36 weeks) | At start of therapy | After 3½ months of therapy | After 17 months of therapy | |

| Length in cm (percentile) | 51.5 (P90) | 62 (P78) | 66 (P69) | 86 (P99) | 49 (P46) | 53 (<P3) | 62 (P72) | 79 (P54) |

| Weight in kg (percentile) | 4.2 (P99) | 6.18 (P65) | 8 (P86) | 16 (>P99) | 3.05 (P35) | 4.49 (<P3) | 5.95 (P46) | 10.8 (P81) |

| Weight/length ratio (percentile) | P90 | P75 | P75 | >P97 | P50 | P75 | P25 | P50 |

| Left ventricular mass index in g/height2.7 by echo (percentile) | 114.5 (P>>99) | 135.7 (>>P99) | 103.5 (>>P99) | 61.6 (P90–95) | 54.9 (P50) | 111.0 (>>P99) | 65.4 (P90) | 54.0 (P75–90) |

| Left ventricular mass in g/m2 by MRI | n/a | 75 | 59 | n/a | n/a | 119 | 65.4 | n/a |

| nt-pro-BNP | n/a | n/a | 2470 | 37 | n/a | 127560 | 8217 | 172 |

| Left ventricular outflow tract gradient | 12 | 49 | 73 | 40 | 20 | 40 | 21 | normal |

| Right ventricular outflow tract gradient | 24 | 62 | 45 | 8 | 20 | 45 | 45 | 21 |

| Infundibular right ventricular outflow tract gradient | 0 | 49 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 16 | 0 |

| Concomitant medications | n/a | Propranolol Trametinib | Propranolol Trametinib | Propranolol Trametinib | n/a | Propranolol Trametinib | Propranolol Trametinib | Propranolol Trametinib |

Infants less than 6 months old with NS, HCM and congestive heart failure have a poor prognosis with a one-year survival of 34%.(1) Trametinib, a highly selective reversible allosteric inhibitor of MEK1/2 activity, is approved treating specific cancers with activation of the RAS/MAPK pathway. As RIT1 mutations cause RAS pathway activation, we postulated that MEK inhibition might limit myocardial hypertrophy. Such beneficial effects were demonstrated in preclinical mouse models for both cardiac and extra-cardiac manifestations of RASopathies. (2,3) Trametinib was associated with reversal of progressive myocardial hypertrophy within four months after initiation of treatment, preceded by a favorable clinical response, in particular for patient 2, who was in critical condition at initiation of treatment. We also observed a catch-up pattern in somatic growth, which is rather unusual for RASopathy mutations and may, at least in part, reflect the recovery from heart failure. (3) In patient 2, chylous effusions ceased within 33 days after initiation of treatment.

Trametinib treatment was associated with reversal of HCM and valvular obstruction in two patients with RIT1-associated NS. While our case series is limited in patient number and allelic spectrum, it raises important questions for the treatment of such cases, in particular with respect to long-term efficacy, long-term side effects, optimal dosing, optimal treatment windows, and impact on other RASopathy manifestations. These outcomes suggest that MEK inhibition merits further study as a mechanistic treatment option for patients with RASopathies. It is conceivable that MEK inhibition may prove most effective during a fixed time window before the onset of irreversible cardiac remodeling in RASopathies, including those caused by genes other than RIT1.

Funding:

G.A. is a Senior Research Scholar of the Fonds de Recherche du Québec — Santé and holder of the Banque Nationale Research Excellence Chair in Cardiovascular Genetics. M.Z. received support from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF): NSEuroNet (FKZ 01GM1602A), GeNeRARe (FKZ 01GM1519A). B.D.G received support from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (HL135742).

Footnotes

Disclosures: G.A., M.A.D., M.Z. and B.D.G. declare that they have consulted with Novartis concerning the possibility of a prospective trial of trametinib in selected patients with RASopathies. They do not have significant financial interests such as consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interests or patent-licensing arrangements. B.D.G. also declares that he receives royalties for genetic testing for Noonan syndrome from LabCorp, Prevention Genetics, GeneDx, and Correlegan. C.M., M.J.R., Y.T., S.W., G.W. and M.H. do not have any disclosures.

References

- 1.Wilkinson JD, Lowe AM, Salbert BA et al. Outcomes in children with Noonan syndrome and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a study from the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry. Am Heart J 2012;164:442–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernandez-Porras I, Fabbiano S, Schuhmacher AJ et al. K-RasV14I recapitulates Noonan syndrome in mice. Proceedings National Academy Sciences USA 2014;111:16395–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu X, Simpson J, Hong JH et al. MEK-ERK pathway modulation ameliorates disease phenotypes in a mouse model of Noonan syndrome associated with the Raf1(L613V) mutation. J clinical investigation 2011;121:1009–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khoury PR, Mitsnefes M, Daniels SR, Kimball TR. Age-specific reference intervals for indexed left ventricular mass in children. J Am Soc Echocardiography. 2009;22:709–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]