Abstract

Gram-positive bacteria coordinate social behavior by sensing the extracellular level of peptide signals. These signals are biosynthesized through divergent pathways and some possess unusual functional chemistry as a result of posttranslational modifications. In this chapter, the biosynthetic pathways of Bacillus intracellular signaling peptides, Enterococcus pheromones, Bacillus subtilis competence pheromones, and cyclic peptide signals from Staphylococcus and other bacteria are covered. With the increasing prevalence of the cyclic peptide signals in diverse Gram-positive bacteria, a focus on this biosynthetic mechanism and variations on the theme are discussed. Due to the importance of peptide systems in pathogenesis, there is emerging interest in quorum-quenching approaches for therapeutic intervention. The quenching strategies that have successfully blocked signal biosynthesis are also covered. As peptide signaling systems continue to be discovered, there is a growing need to understand the details of these communication mechanisms. This information will provide insight on how Gram-positives coordinate cellular events and aid strategies to target these pathways for infection treatments.

Keywords: Gram-Positive Bacteria, cyclic peptides, quorum sensing, signal transduction

I. INTRODUCTION

There is growing appreciation that bacteria are social creatures. Most representative organisms under investigation have evolved a system to coordinate regulatory events by communicating with neighbors using signaling molecules. This social behavior allows the bacterial population to invest energy in cellular processes only at the appropriate time, usually when a neighboring population has reached a critical mass or “quorum” for a specific response.15, 52, 66 Thus, this type of communication has been coined “quorum-sensing” for the cell density dependence of the regulatory events that ensue. For a pathogen, this coordinated activity can have benefits, allowing the invader to fly under the radar of an immune system until the opportune time to produce virulence factors and overwhelm host defenses. Similarly for symbiotic bacteria, communicating with neighbors allows bacteria to synchronize an important cellular response with the host that facilitates the cooperative lifestyle.

In general, the signaling molecules used for quorum-sensing in Gram-negative bacteria are predominantly small chemicals. The best known class of these signals is the acyl-homoserine lactones, although more divergent signal chemistry continues to be discovered. Many excellent reviews are available on the Gram-negative quorum-sensing mechanisms and the reader is referred to these articles for more information.24, 25 In contrast, Gram-positive bacteria prefer to communicate with signals that are based on short peptides. These peptide signals, sometimes called “autoinducing peptides,” can be secreted as unmodified structures or they can be the target of diverse posttranslational modifications (Figure 1).

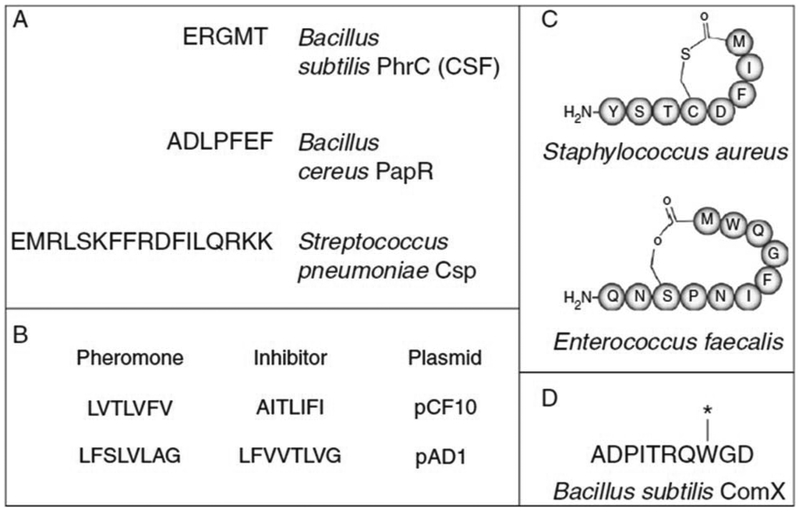

Figure 1.

Examples of quorum-sensing signals produced by Gram-positive bacteria. (A) Unmodified linear peptide signals produced by Bacillus and Streptococcus. (B) Enterococcus plasmid pheromones and their corresponding inhibitors. (C) The cyclic autoinducing peptides produced by many Gram positives. (D) The ComX competence pheromone of B. subtilis 168. The tryptophan residue is farnesylated through an unusual posttranslational modification.

Among the Gram-positive peptide signals, there is a surprising amount of chemical variation. The simplest of these signals are the unmodified, linear peptides that are secreted by many Gram-positives. Some of the best known examples of this signal class are the Bacillus peptide signals, the competence peptide of Streptococcus pneumoniae, and the Enterococcus pheromones. An emerging class of peptide signals are the cyclic lactones and thiolactones produced by Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, and many other genera of Gram-positives. Finally, some peptide signals are the subject of more complex posttranslational modification, such as the Bacillus subtilis competence pheromones.

Among the peptide signals, there is surprising diversity and complexity within the biosynthetic pathways. For the Gram-negatives, acyl-homoserine lactones are freely permeable across membranes, making the production of these signals dependent on usually one enzyme and otherwise simplistic. However, the Gram-positive peptides are not permeable and thus are the subject of more complex biosynthesis and export mechanisms. Although the peptide signals are ribosomally generated, there is considerable diversity within the pathways to achieve the functional, extracellular end product. This area of research is constantly evolving as new details are being elucidated. At this time, three general mechanisms of biosynthesis and export have emerged and most of the peptide signals fall into one of these three groupings (Figure 2). In this review, the three biosynthetic pathways of the signaling peptides will be covered in detail. Although the Enterococcus pheromones mediate conjugation and not a typical quorum-sensing response, the unusual features of their biosynthetic pathway warrant attention and are covered herein. Due to the growing importance of the cyclic peptide systems, there is a focus on the paradigm biosynthetic pathways of the Staphylococcus aureus autoinducing peptides. Emerging information about quorum-quenching approaches and peptide signals from other Gram positives are also discussed.

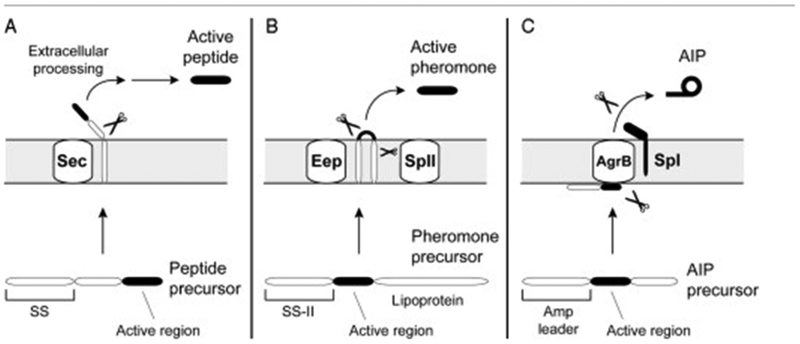

Figure 2.

Comparison of peptide signal biosynthetic pathways in Gram positives. (A) The biosynthesis of intracellular acting peptides in Bacillus. The active region is usually on the C-terminus of the precursor peptide, and the leader is a standard signal sequence (SS). Following Sec secretion, the precursor is processed outside the cell by extracellular proteases. (B) The biosynthesis of Enterococcus pheromones. The precursor has a Type II signal sequence and a long lipoprotein C-terminal tail (not drawn to scale). Type II signal peptidase (SpII) removes the lipoprotein tail, and an integral membrane peptidase (Eep) removes the N-terminal leader (SS-II). In some cases, extracellular processing also occurs. (C) The biosynthesis of cyclic peptide signals. The precursor has an amphipathic leader and a charged C-terminal tail. The tail is removed by an AgrB-like membrane endopeptidase, and the leader is removed by Type I signal peptidase (SpI). AgrB is proposed to also catalyze the ring formation and export of the AIP signal.

II. BACILLUS INTRACELLULAR SIGNALING PEPTIDES

Peptide-mediated regulation is an important part of the spore-forming Bacillus lifestyle. Many critical cellular events, such as competence, spore formation, and virulence factor expression are all under the control of these intracellular acting regulatory peptides. Similar to the Enterococcus pheromones, Bacillus signaling peptides are exported out of the cell and then are reimported through an oligopeptide permease to perform an intracellular regulatory function (Figure 2A). The active form of these peptides is a linear segment of unmodified amino acids, usually five to seven residues in length. The signaling peptides are chromosomally encoded and expressed as polypeptide precursors of about 40–45 amino acids. The precursors have an amino-terminal leader with a signal peptidase cleavage site, and the business end is located at the C-terminal region. For most of the regulatory peptides, the active form is the last five residues of the C-terminal region, but in some cases, such as PhrE of B. subtilis, the active form is located internally in the region.

A. B. subtilis CSF

Perhaps the best studied of the Bacillus intracellular acting signaling peptides is CSF (PhrC), named for its ability to stimulate competence and sporulation. CSF is a five-residue, unmodified peptide that is encoded in the phrC gene and is expressed as a 40-amino acid precursor. The active form of CSF is reimported through an oligopeptide permease and the peptide exerts its regulatory action inside the cell (Figure 3). The CSF regulatory functions have been described in detail elsewhere and will not be covered here.37, 38 More recently, important details of the biosynthetic pathway leading to functional CSF peptide have been investigated. The N-terminal leader of the PhrC polypeptide precursor has all the features of a standard signal sequence, including a consensus AXA cleavage site for Type I signal peptidase. Surprisingly, attempts to demonstrate that signal peptidase is required for processing through genetic and biochemical approaches have not been successful.62 The reason for the lack of processing is not clear. Signal peptidase is an essential enzyme and there are five encoded on the B. subtilis chromosome, making genetic analysis of this function challenging. Additionally, kinetic studies have demonstrated that signal peptidase enzymes process peptides inefficiently unless the substrate is presented in a manner more similar to actual secretion.61

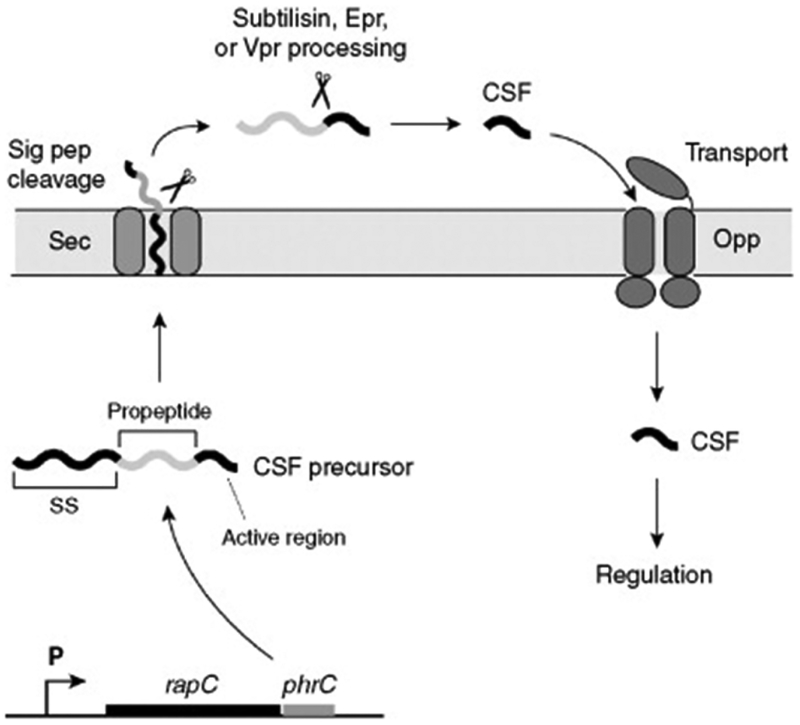

Figure 3.

CSF biosynthesis in B. subtilis. The precursor of the CSF signal is ribosomally synthesized from the phrC gene. Following synthesis, the signal sequence directs the section through the Sec system, and Type I signal peptidase removes the leader. Outside the cell, the propeptide is processed to the active form of CSF through the cleavage activities of the extracelluar serine proteases subtilisin, Epr, and Vpr. Once active CSF is generated, the signal can be reimported through an oligopeptide permease (Opp), and CSF can exert its regulatory function inside the cell

Following export of the PhrC propeptide into the extracellular environment, the propeptide has to be processed into the active pentapeptide form of CSF. In recent studies by Lanigan-Gerdes et al.,35 protease inhibitor profiling, localization studies, and regulatory tests demonstrated that the processing enzyme was an extracellular serine protease under sigma-H control. The subtilisin, Epr, and Vpr proteases meet these criteria and purified subtilisin and Vpr processed the propeptide into functional CSF signal. Further mutational analysis of the propeptide residues in the −1 to −5 location from the CSF cleavage site demonstrated that these residues are critical for extracellular processing.36

B. Bacillus cereus PapR

Additional examples of intracellular acting peptides among the Bacillus species continue to be discovered. Perhaps the most notable example is the PapR peptide from B. cereus. The functional form of PapR is a linear, unmodified heptapeptide that is derived from a 48-residue precursor.9 After import through an oligopeptide permease, PapR activates the PlcR global transcriptional regulator and induces virulence gene expression.60 The biosynthetic pathway shows similarity to B. subtilis CSF and related Phr peptides. The PapR N-terminal leader looks like a signal sequence that facilitates Sec secretion, and following cleavage, a 27-residue propeptide is released into the extracellular environment. Synthetic versions of this propeptide activate gene expression, supporting the release of this sequence.60 However, oligopeptide permeases prefer shorter peptide segments and, coupled with the known active form of PapR as a heptapeptide, extracelluar processing is necessary to remove the leader on the propeptide. Recently, Pomerantsev and colleagues identified the NprB protease as having a role in processing the 27-residue propeptide into the active form of PapR.53 In support of this finding, exogenous addition of the propeptide cannot complement an nprB mutant, while the active form of PapR was functional. Interestingly, the nprB gene is flanking the plcR-papR region on the B. cereus chromosome, suggesting that this molecular arrangement may be informative for future identification of signaling peptides.

At this time, the CSF and PapR-like peptide signals appear limited to the species of Bacillus. Challenges have precluded the discovery of additional intracellular acting peptides of this class. For instance, the biosynthetic mechanism is performed entirely by housekeeping functions, such as the Sec system, signal peptidase, and a variety of extracellular proteases. None of these functions has unique qualities making the potential for bioinformatic discovery of new regulatory peptides difficult. Also, the target protein encoded next to the propeptide gene, such as the plcR gene flanking papR, is not conserved among the Bacillus peptide signals, limiting its utility as a mining tool. There have been proposals that mutations in the oligopeptide permease (Opp) could be a means for detecting functional, intracellular acting peptides, and Opp mutants have phenotypes in some Gram positives37. However, many Gram positives have two or more of these permease systems, making this approach to uncovering new peptides less straightforward.

III. ENTEROCOCCUS PHEROMONES

Another well-known peptide signaling system is the regulation of Enterococcus faecalis plasmid conjugation using pheromones. Like other Gram-positive peptide systems, this mechanism relies on the accumulation of a pheromone peptide that activates a response, in this case the assembly of the conjugation machinery to transfer a plasmid from a donor cell to a recipient. Unlike other peptide systems, the threshold peptide concentration cannot be reached when only a donor cell is around. Recipient cells without plasmid must be present for enough activating pheromone to be produced. This control is mediated by plasmid-encoded inhibitory peptides which resemble the activating pheromones but function to inhibit their activity. Additional cell-bound proteins decrease pheromone levels produced by donor strains,14, 27 maintaining the tight regulatory control. This design prevents the energy-intensive assembly of the conjugative apparatus until a plasmid-free recipient cell is present. For more detailed information on the regulation of this system, the reader is referred to comprehensive reviews.17,18

A number of studies have investigated the biosynthetic mechanism of the E. faecalis activating and inhibitory pheromones. Interestingly, the pheromones themselves are encoded within the N-terminal signal sequences of lipoproteins.19 The first step of pheromone synthesis occurs when these lipoproteins are transported across the membrane and cleaved by Type II signal peptidase (Figure 2B). This enzyme cleaves at the N-terminal side of a cysteine residue in the leader to allow lipid modification at the cysteine side chain. The released peptide consists of the 12–16 N-terminal residues that correspond to the signal sequence and another seven- to eight-residue pheromone. For one pheromone precursor, cCF10p, the signal peptidase cleavage also leaves three residues on the C-terminal end of the final pheromone product, which are later removed by an unknown carboxy exopeptidase mechanism.5

The integral membrane protease, named Eep for enhanced expression of pheromone, mediates the second cleavage in the pheromone precursor.3 The second cut occurs at the N-terminal leader to release the peptide from the rest of the signal sequence. Eep belongs to a class of metalloproteases capable of carrying out regulated intramembrane proteolysis (RIP). These proteases cleave at transmembrane segments within the cell membrane and are conserved from bacteria to humans.11 Studies using truncated pheromone peptides lacking the attached lipoprotein demonstrated that the signal sequences alone serve as substrates for Eep, suggesting that Eep cleavage occurs after signal peptidase II18. This sequence of events coincides with other RIP systems in which intramembrane proteolysis follows an initial cleavage by another protease. Production of inhibitory peptides of the pheromone system occurs via a similar mechanism. These inhibitory peptides, which are encoded on the conjugatable plasmids, consist of only an N-terminal signal sequence and the active peptide region without the C-terminal lipoprotein domain.19 The inhibitory peptides are cleaved by Eep and released from the cell in a manner thought to be similar to the activating pheromones.19

IV. S. AUREUS AUTOINDUCING PEPTIDES

A. The agr system and AIP signal

The accessory gene regulator (agr) system serves as the quorum-sensing system in S. aureus and is a major regulator of virulence factor production. Activation of agr results in the upregulation of many genes, most notably secreted virulence factors, while also downregulating production of many surface proteins.46 Not surprisingly, the agr locus has been demonstrated to be important for pathogenesis in numerous animal models of infection.1, 12, 13

The agr locus consists of two divergent transcripts controlled by the P2 and P3 promoters. P2 drives transcription of a four-gene operon (agrBDCA) whose products are involved in the production (agrBD) and sensing (agrCA) of the quorum-sensing signal autoinducing peptide (AIP). P3 activates transcription of RNAIII, a 514-nucleotide regulatory RNA which acts as the effector molecule to upregulate and downregulate agr-controlled genes.20, 47 Extracellular AIP is detected by histidine kinase, AgrC, which is localized to the cell surface and acts in concert with AgrA to form a two-component sensory system. AIP binding activates AgrC to phosphorylate AgrA, and the activated AgrA proceeds to induce the P2 and P3 promoters,34 leading to autoinduction of the system and production of RNAIII effector. The mechanism of AIP sensing by AgrC and the agr regulatory effects is an active area of research and beyond the scope of this review, and the reader is referred elsewhere for more information.39,46

The AIP signal itself is a seven- to nine-residue peptide with the C-terminal five residues wrapped into an unusual cyclic thiolactone (Figure 1C). In the ring structure, the cysteine side chain is directly linked to the carboxylic acid moiety on the C-terminal residue. Among Staphylococcal species, the cysteine residue is conserved except in S. intermedius where it is replaced with a serine, resulting in lactone ring formation.31, 32 Not surprisingly, the cysteine (or serine in the case of S. intermedius) is essential for AIP biosynthesis.64

Among S. aureus stains, there are four classes of AIP signals that fall into three cross inhibitory groups.28, 30 These signals all share the same five-residue thiolactone ring with a short N-terminal extension, but the actual amino acids in the signal are divergent. The inhibitory activity comes into play when two different agr types are in close proximity. The AIP of one strain, such as AIP Type I (AIP-I), will interfere with the function of AgrC on the opposing S. aureus cell by competing for the receptor. The inhibition is surprisingly effective with near-equal affinity for both activating and inhibiting receptors, and the mechanism has been coined “agr interference”.30 Why S. aureus has evolved this mechanism is unknown, although fitness tests suggest that the producing strain has a competitive advantage.22 Exploiting this interference mechanism has been useful in quenching the agr response and blocking S. aureus infection.68 To simplify coverage of the biosynthetic pathway, hereafter only the Type I class of AIP molecule will be discussed unless otherwise stated.

B. AgrD and AgrB properties

The process of transforming the propeptide encoded by agrD into the functional AIP molecule is surprisingly complex. The propeptide has to be cleaved two times, cyclized to generate the thiolactone ring, and exported. Production of AIP begins with the synthesis of AgrD, the propeptide that is processed into the final, functional AIP signal. AgrD is a 46-amino acid peptide consisting of three distinct regions. The N-terminal leader forms an amphipathic helix, the middle segment encodes the final AIP sequence, while the C-terminal tail is highly charged and more conserved than the first two segments. Studies on the amphipathic helix domain have demonstrated that its role is to target the AgrD propeptide to the cell membrane.71 Removal of the N-terminal helix prevents association with the membrane, while swapping the native helix with a different amphipathic helix preserves the function of AgrD. It is important to stress that the N-terminal region is not a signal sequence, and replacing the region with a prototype Sec signal peptide blocked AIP production.71

Continuing with AgrD, the middle segment consists of eight residues that make up the final AIP molecule, while the C-terminal domain is composed of 14 residues, many of which are negatively charged. The role of the C-terminal tail in AIP production remains to be fully determined and has been an active area of investigation. Experiments in our laboratory have demonstrated that the terminal four residues are dispensable, but the remaining 10 are essential for optimal AIP production.64 Of note, glutamate 34 and leucine 41 play important roles in the tail’s function, as replacing either of these residues prevents AgrD cleavage and AIP production. We have hypothesized that the C-terminal region interacts with AgrB, facilitating orientation of the peptide for cleavage.

AgrB is a 22-kDa integral membrane endopeptidase.56, 64 PhoA mapping studies indicate that the enzyme contains six transmembrane helices with the N and C-terminal ends located in the cytoplasm.70 One known role of AgrB is the removal of the AgrD C-terminal tail. Two residues, histidine 77 and cysteine 84, have been shown to be essential for AgrB peptidase activity, suggesting that AgrB acts as a cysteine endoprotease despite a lack of homology to known proteases.56 Both of the catalytic residues are predicted to be exposed to the cytoplasmic face,70 indicating that cleavage of the AgrD C-terminal domain occurs in the cytoplasm. To date there are no reports of a tertiary or quaternary structure of AgrB, in large part due to the difficulty of overexpressing and purifying integral membrane proteins. Studies of this nature would be useful in examining the proposed role of AgrB as a possible transport protein for AIP secretion.

C. AIP biosynthetic mechanism

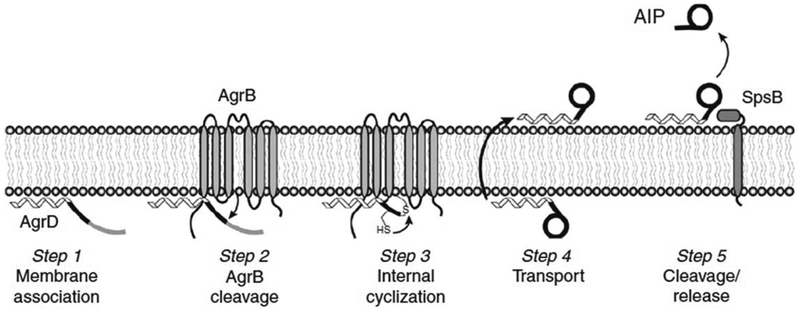

The detailed mechanism of how AgrD is processed into AIP remains an active area of investigation. Figure 4 provides a summary of a proposed model for the sequence of AgrD processing and how the AIP thiolactone structure might be formed.64 Initially, the AgrD propeptide associates with the cytoplasmic membrane via its amphipathic N-terminal helix (Step 1). AgrB then interacts with AgrD and removes the C-terminal region of AgrD by carrying out a nucleophilic attack with the essential cysteine (C84) residue (Step 2). The nature of this initial interaction remains unclear; however, it is interesting to note that the cytoplasmic loop portions of AgrB contain numerous positively charge residues, while the C-terminal portion of AgrD is highly negatively charged, suggesting a potential charge–charge interaction. The cleavage reaction creates an intermediate in which the N-terminal leader and AIP regions of AgrD are covalently linked to the AgrB cysteine residue (C84) via a thioester bond. Following formation of this intermediate, the AgrD cysteine (C28) within the AIP region attacks the activated carbonyl to carry out thioester exchange, resulting in thiolactone ring formation between the cysteine side chain and the C-terminal carboxylic group of the peptide (Step 3). This thioester exchange could be spontaneously driven by structurally positioning the nucleophilic thiol near the labile thioester. After ring formation, the intermediate structure would be released from AgrB and must be moved to the outer face of the membrane (Step 4). It has been proposed that AgrB is capable of mediating this transport, though this remains to be experimentally demonstrated. Other possible mechanisms include the use of housekeeping export functions, cell lysis, or self-mediated membrane flipping as a means of reaching the outer face. AIP can be produced in Escherichia coli by providing only agrB and agrD, which indicates that alternative Staphylococcus transport proteins would have to be retained in E. coli.64 In the final step of processing, the N-terminal helix of AgrD is removed to release AIP into the extracellular environment (Step 5). Type I signal peptidase (SpsB) has been shown to mediate this cleavage for S. aureus AIP-I production,33 though it has yet to be shown that this mechanism is used by other Staphylococcus species.

Figure 4.

Schematic of AIP biosynthesis in S. aureus. Step 1: the AgrD N-terminal amphipathic helix associates with the cytoplasmic membrane. Step 2: the endopeptidase activity of AgrB removes the C-terminal tail of AgrD. Step 3: the remaining AgrD peptide fragment (N-terminal and AIP regions) is covalently bound to AgrB as a linked thioester at cysteine residue C84. Nucleophilic attack of the AgrD cysteine residue (C28) can displace the peptide and form the thiolactone ring through thioester exchange. Step 4: the N-terminal leader and thiolactone is transported to the outer face of the membrane. Step 5: Type I signal peptidase (SpsB) removes the leader and releases AIP into the extracellular environment. This figure was originally published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.64

Interestingly, AgrB-mediated processing of AgrD occurs in a species and agr group specific manner. In a study by Ji et al.,30 AgrB proteins from S. aureus agr groups I, II, and III and Staphylococcus lugdunensis were coexpressed with AgrD peptides from each group and tested for AIP production. The Type I and III versions of AgrB were both able to produce type AIP-I or AIP-III; however, Type II AgrB was able to produce only AIP-II, and the same restriction was observed with S. lugdenensis. It is worth noting that that the S. aureus Type II agr system is the most divergent of the agr subtypes. AgrB and AgrD must have coevolved to maintain the specific interactions necessary for AgrD processing.

V. OTHER CYCLIC PEPTIDE SIGNALING SYSTEMS

Many Gram-positive species contain quorum-sensing systems that are analogous to the agr system of S. aureus. These systems possess similar production and sensory components as found in agr, and they also use cyclic peptides as their signaling cue. While two-component sensory components are ubiquitous in bacteria, the defining feature of these analogous peptide systems is the presence of AgrB-like proteins with sequence similarity to those found in S. aureus. In fact, the uniqueness of AgrB enables the use of this protein as a bioinformatics mining tool to uncover new peptide signaling systems in sequenced genomes.69 Through a simple alignment search, it is apparent that many diverse genera of Gram positives, even noted pathogens, contain open reading frames that encode AgrB-like proteins. Whether or not these diverse bacteria all have cyclic peptide systems remains to be determined, but the conserved nature of the system across many Gram positives is striking.

The AgrD-like propeptides also show strong conservation in their overall organization of three distinct regions, with the middle portion always encoding the final cyclic thiolactone or lactone. One key area of variability is the presence of divergently transcribed regulatory RNA near the signaling operons. Bioinformatic analysis suggests that the RNAIIIlike molecule is limited to the Staphylococcus species.69 In other bacteria, there seems to be a more primary role for the response regulator in controlling transcription of the target genes. Several examples of cyclic peptide systems from non-Staphylococci are outlined below.

A. E. faecalis fsr system

After the S. aureus agr system, the fsr system of E. faecalis is perhaps the second most intensively studied cyclic peptide sensory mechanism. The fsr system was originally identified by its proximity to the gelE gene encoding gelatinase. The locus consists of four genes, fsrABDC, whose products show significant homology to the agr genes in S. aureus. However, the molecular arrangement of the fsr locus is divergent from the agr system. In the fsrABDC operon, the first and last genes encode a two-component sensory pair, FsrA and FsrC, while the middle two genes encode factors involved in signal biosynthesis, FsrB and FsrD.

The signaling peptide produced is a cyclic lactone named the gelatinase biosynthesis-activating pheromone (GBAP). GBAP is an 11-residue peptide containing a nine-membered ring and a two-amino acid tail (Figure1c). Originally the GBAP peptide was thought be produced as the C-terminal end of FsrB, from which the peptide precursor was cleaved and processed to make GBAP. While the FsrD propeptide is encoded in frame with FsrB, further studies revealed that a Shine–Dalgarno sequence and start codon are present within the 30 end of the fsrB gene. Disruption of either of these elements dramatically reduced GBAP activity, while inserting a stop codon between fsrB and fsrD did not affect GBAP production.43 Taken together, it is clear that FsrD is indeed translated independently of FsrB.

The FsrD propeptide shares the same three-domain structure of AgrD; however, the C-terminal portion of FsrD has an overall positive charge. Interestingly, many of the positively charged residues in a cytoplasmic loop of AgrB have been replaced with neutral or negatively charged residues in FsrB, again suggesting a possible interaction between the membrane peptidase cytoplasmic loop and the C-terminal portion of the signaling propeptide.43 It is plausible that FsrD is processed in a mechanism similar to the one proposed for AgrD in S. aureus, with the exception being that the serine of GBAP substitutes for the cysteine to form a lactone bond. Activation of fsr in E. faecalis results in upregulation of gelatinase and serine protease production,54, 55 both of which are encoded immediately downstream of the fsr operon. Other global transcriptional regulatory effects also occur following fsr activation.10 Importantly, the fsr locus is required for E. faecalis pathogenesis in models of mouse peritonitis, invertebrate infection,59 and rabbit endophthalmitis.42

B. Listeria monocytogenes agr system

L. monocytogenes is a foodborne pathogen capable of causing parasitic infections in humans. A chromosomal locus with similarity to the agrBDCA operon was identified in a transposon mutagenesis screen and found to affect virulence in an intravenous mouse model.6 Mutations in either agrA or agrD resulted in decreased biofilm formation,58 unlike the S. aureus agr system, where agr mutations increase biofilm formation.8 The L. monocytogenes agrD mutant also displayed moderate attenuation in a mouse infection model.57 Although studies were performed showing the supernatants contain active signal,57 the autoinducing peptide has yet to be purified from these strains, leaving the exact structure of the final peptide unknown.

C. Clostridium perfringens agr system

C. perfringens is another human pathogen in which the agr system plays an important role in virulence gene regulation.48 Strains lacking agrBD showed a significant reduction in the transcription of theta-, alpha-, and kappa-toxin genes. Unlike other agr-containing species, C. perfringens (and other Clostridium species) does not encode an AgrCA-like two-component sensory system next to the agrBD genes. The VirR/VirS system in C. perfringens has been demonstrated to be necessary for toxin gene activation in response to the quorum-sensing signal; however, further studies demonstrating direct activation of VirR/VirS by the AIP are needed to confirm that these proteins are filling the sensory role.

D. Lactobacillus plantarum agr system

L. plantarum is an example of a nonpathogenic, environmental isolate that contains an agr-like quorum-sensing system. L. plantarum is found in diverse environmental niches, such as plant material and fermented food, and is often identified as part of the intestinal microflora. The agr-like system on the chromosome is called the lamBDCA operon and has a similar molecular arrangement with the biosynthetic machinery encoded before the two-component system.63 The lam regulatory system is important for adherence and biofilm development, in contrast to the S. aureus agr system. To structurally identify the lam signal, the lamBD genes were overexpressed and a peptide corresponding to a cyclized version of the sequence CVGIW was purified. Similar to the Staphylococcal AIPs, the five residues were joined as a thiolactone ring with the cysteine side chain linked to tryptophan carboxy terminus. However, this peptide is notable for its lack of N-terminal tail residues found in other AIP-like molecules. Whether this structure represents the full secreted peptide remains unclear given that exogenous addition of synthesized peptide was unable to induce lam operon expression. It is interesting to note that L. plantarum possesses dual two-component systems (lamCA and lamKR) capable of responding to the quorum-sensing signal, both of which regulate the same subset of genes.23

VI. B. SUBTILIS COMPETENCE PHEROMONES

One of the most interesting biosynthetic mechanisms of the peptide signaling systems is the B. subtilis competence pheromones. These peptides are ribosomally synthesized from the comX gene, which encodes a 55-amino acid precursor of the pheromone in the B. subtilis 168 type strain.41 The comX gene is part of a four-gene operon, comQXPA, and the overall molecular arrangement has similarity to the S. aureus agr locus.7, 29, 65 For the encoded functions, ComQ would be the AgrB counterpart and ComX is the signal precursor like AgrD, while ComA and ComP compromise a two-component regulatory system that detects the mature form of extracellular ComX pheromone.

The functional form of the pheromone in the 168 type strain is a 10-residue linear peptide derived from the C-terminal end of the ComX 55-residue precursor.41 Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the signal is the posttranslational modification on the tryptophan residue.4 The tryptophan is isoprenylated through an unusual addition of a farnesyl group to form a ring-like structure.50 Depending on the Bacillus isolate, the exact sequence of the functional peptide pheromone and type of isoprenylation can vary. Other strains, such as B. subtilis RO-E-2, secrete an active pheromone that is comprised of only five residues with a tryptophan residue that is geranylated.49, 50

For the biosynthetic pathway in B. subtilis 168, the comX and comQ genes are essential for pheromone production. Expression of comX and comQ in E. coli reconstitutes biosynthesis, suggesting that these encoded proteins are the only unique functions in B. subtilis required to produce the pheromone.65 To date, only limited information about ComQ is available and there is no obvious homology to S. aureus AgrB. For this reason, we have not included this biosynthetic pathway in Figure 2.

The ComQ protein is 299 residues in length and appears to have membrane spanning regions,67 although further analysis is necessary to confirm this prediction. Interestingly, the ComQ protein shows sequence similarity to isoprenyl phosphate synthases.7 Considering the homology to isoprenyl transfer enzymes, the known farnesylation of the pheromone, and E. coli reconstitution experiments, it seems likely that ComQ is the primary enzyme involved in processing the 55-residue precursor to the functional pheromone. Consistent with this proposal, mutations in a putative isoprenoid binding domain on ComQ blocked signal production,7 supporting the proposed isoprenyl transfer activity of the enzyme. However, the ComQ enzyme has not been biochemically characterized in further detail to elucidate the complex enzymatic mechanism. Based on available information, the precursor peptide has to be proteolytically cleaved, isoprenylated on a tryptophan, and secreted all through the action of ComQ. It is possible that some of these functions could be performed by house-keeping proteins, but they would have to be conserved in E. coli.65 Further studies are necessary to unravel these complex questions about ComX pheromone biosynthesis.

VII. QUENCHING SIGNAL BIOSYNTHESIS

The requirement for bacterial communication in pathogenesis has raised considerable interest in quorum-quenching approaches (Figure 5). The essential nature of communication mechanisms in S. aureus and L. monocytogenes infections highlights the value of this research direction.12, 13, 57 Currently, most of these approaches have targeted the signals themselves or the receptors, while attempts to block the biosynthesis of the signals have remained relatively unexplored. As the knowledge of these biosynthetic mechanisms grows, this remains a fertile area for future development of innovative approaches towards quorum-quenching.

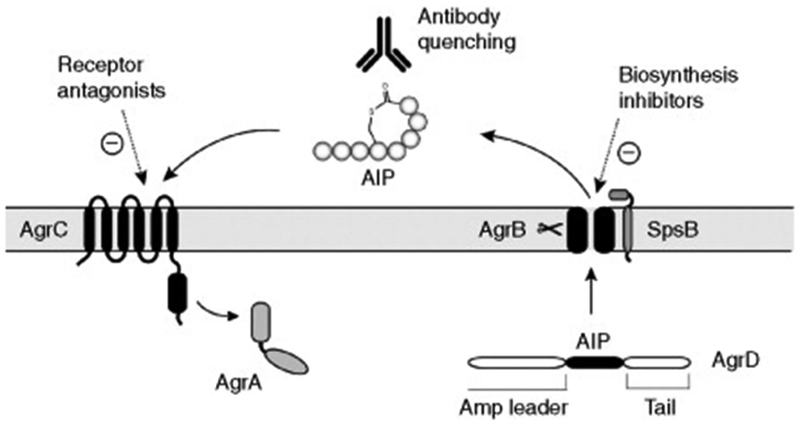

Figure 5.

Strategies to quench peptide communication mechanisms. A schematic of the S. aureus agr system is shown as an example. A common approach for interrupting peptide quorum sensing is through receptor antagonists, and there are many examples of successful inhibitors that have been identified through synthesis and screening approaches. Recently, an antibody sequestering strategy against AIP was shown to be successful in quenching the S. aureus agr system in vitro and in vivo. For interrupting signal biosynthesis, several successful attempts have been reported, the most notable being against the E. faecalis fsr system.

Whether or not the biosynthetic apparatus in Gram-positive pathogens becomes an appealing target remains to be determined. The current target of choice for inhibitor development is the signal receptor, especially for the cyclic-based signals. Antagonist discovery for the receptors is appealing due to their extracellular exposure and lack of outer membrane barriers, diversifying the functional chemistry that can be employed in inhibitor design.16, 26,39 The eventual challenge of this approach is the variation among signal receptor classes even within one species of bacterial pathogen. While efforts at identifying broad-spectrum inhibitors have been made,26,40 there will always be challenges due to the inequality of antagonist activity across a particular pathogen subgroup. Thus, the receptor-based approach faces the ongoing difficulty of narrowness in application, which could limit the therapeutic potential.

As a counter to this problem, researchers have stepped back further in the quorum-sensing mechanism and focused on the peptide signals themselves (Figure 5). The appeal of this strategy is that nature has already taken this approach and evolved multiple host defense mechanisms to either inactivate or sequester the signal. One successful therapeutic strategy has been the preparation of monoclonal antibodies to the S. aureus AIP Type IV signal.51 Normally in the host, the AIP signals are transient by design to facilitate the temporal response of the bacterial regulatory systems. To counter this challenge, synthetic mimics of the AIP were prepared, and mouse monoclonal antibody was generated from the hapten. The most effective antibody quenched the agr system response, and most importantly prevented acute infection in abscess models.

Stepping back even further in the pathway, there are several examples of small-molecule inhibition of cyclic peptide signal biosynthesis (Figure 5). For S. aureus, linear peptide inhibitors of Type I signal peptidase were identified and found to reduce AIP-I production and quench agr function.33 Signal peptidase is an essential enzyme and also a promising antimicrobial target due to the extracellular location of the active site. In E. faecalis, screens of actinomyces extracts lead to the identification of siamycin I, a known lantibiotic, as a quencher of the fsr quorum-sensing system.44 Further investigation lead to the discovery that siamycin directly reduced the amount of GBAP signal produced. The inhibition was potent, functioning at submicromolar levels, but whether siamycin reduces GBAP levels through the inhibition of FsrB or another mode of action is not clear.

In one of the most impressive quorum-quencher reports, Nakayama et al.45 identified ambuic acid as a powerful inhibitor of cyclic peptide signal biosynthesis. Ambuic acid quenches the fsr quorum-sensing system in E. faecalis and reduces the amount of GBAP secreted. Importantly, ambuic acid found was found to directly inhibit FsrB proteolytic activity, suggesting that this membrane endopeptidase is the inhibitor target. Perhaps most notable, ambuic acid functions as a general quencher of cyclic peptide quorum-sensing across numerous Gram positives. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS) studies revealed that the production of S. aureus AIP-I and the Listeria innocua peptide signal (structure unknown) were inhibited following ambiuc acid treatment.45 Whether or not the compound targets the AgrBtype enzymes in S. aureus and L. innocua is not clear, but it seems likely based on the FsrB precedent from the E. faecalis studies. The broadspectrum activity of ambuic acid highlights the value of inhibitor screening on the peptide signal biosynthetic machinery versus the divergent signal receptors. While this approach has promise for future inhibitor discovery, the lack of knowledge of AgrB/FsrB type enzymes is currently limiting screening or rational design efforts.

VIII. CONCLUSIONS

While tremendous effort has been placed on unraveling the complexities of Gram-negative quorum-sensing systems, the corresponding Gram-positive systems have not received the same research attention. This is somewhat surprising considering that the peptide systems are essential for pathogenesis in S. aureus, E. faecalis, and L. monocytogenes. Moreover, peptide communication mechanisms are conserved in environmental and commensal isolates, suggesting that an improved understanding of these regulatory systems has broad implications.

The aspect of peptide quorum sensing with the most unanswered questions is signal biosynthesis. As outlined in Figure 2, there are three general pathways of biosynthesis that accommodate the known classes of signals. For some peptides, such as the intracellular acting Bacillus signals, the route of biosynthesis appears straightforward through a Sec secretion and extracellular processing mechanism. In contrast, for signals with posttranslational modifications (Figure 1), essential enzymes in the biosynthetic pathways have been identified, but there is limited information on how these enzymes catalyze steps at a biochemical level. Perhaps more striking, almost nothing is known about how the processed signals are transported into the extracellular environment. Despite the limited information, quorum-quenching approaches are growing in popularity as a means of therapeutic intervention for treating infections. Further, evidence is emerging that interrupting signal biosynthesis may be attractive for quenching across diverse genera of pathogens. Considering the contrast between available knowledge and the rising interest in the targets, there is a growing need to fill the void and address the open questions. With the steady improvement in genetic and molecular approaches for investigating Gram positives, hopefully continued progress can be made on unraveling the mechanistic details of the peptide quorum-sensing systems.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M. Thoendel was supported by NIH Training Grant No. T32 AI07511. Research in the laboratory of A. R. Horswill was supported by award AI078921 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdelnour A, Arvidson S, et al. (1993). The accessory gene regulator (agr) controls Staphylococcus aureus virulence in a murine arthritis model. Infect. Immun 61(9), 3879–3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An FY, and Clewell DB (2002). Identification of the cAD1 sex pheromone precursor in Enterococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol 184(7), 1880–1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.An FY, Sulavik MC, et al. (1999). Identification and characterization of a determinant (eep) on the Enterococcus faecalis chromosome that is involved in production of the peptide sex pheromone cAD1. J. Bacteriol 181(19), 5915–5921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ansaldi M, Marolt D, et al. (2002). Specific activation of the Bacillus quorum-sensing systems by isoprenylated pheromone variants. Mol. Microbiol 44(6), 1561–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antiporta MH, and Dunny GM (2002). ccfA, the genetic determinant for the cCF10 peptide pheromone in Enterococcus faecalis OG1RF. J. Bacteriol 184(4), 1155–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Autret N, Raynaud C, et al. (2003). Identification of the agr locus of Listeria monocytogenes: Role in bacterial virulence. Infect. Immun 71(8), 4463–4471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bacon Schneider K, Palmer TM, et al. (2002). Characterization of comQ and comX, two genes required for production of ComX pheromone in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol 184(2), 410–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boles BR, and Horswill AR (2008). agr-Mediated dispersal of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. PLoS Pathogens 4(4), e1000053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouillaut L, Perchat S, et al. (2008). Molecular basis for group-specific activation of the virulence regulator PlcR by PapR heptapeptides. Nucleic Acids Res 36(11), 3791–3801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourgogne A, Hilsenbeck SG, et al. (2006). Comparison of OG1RF and an isogenic fsrB deletion mutant by transcriptional analysis: The Fsr system of Enterococcus faecalis is more than the activator of gelatinase and serine protease. J. Bacteriol 188(8), 2875–2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown MS, Ye J, et al. (2000). Regulated intramembrane proteolysis: A control mechanism conserved from bacteria to humans. Cell 100(4), 391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bubeck Wardenburg J, Bae T, et al. (2007a). Poring over pores: Alpha-hemolysin and Panton-Valentine leukocidin in Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Nat. Med 13(12), 1405–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bubeck Wardenburg J, Patel RJ, et al. (2007b). Surface proteins and exotoxins are required for the pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Infect. Immun 75(2), 1040–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buttaro BA, Antiporta MH, et al. (2000). Cell-associated pheromone peptide (cCF10) production and pheromone inhibition in Enterococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol 182(17), 4926–4933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Camilli A, and Bassler BL (2006). Bacterial small-molecule signaling pathways. Science 311(5764), 1113–1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan WC, Coyle BJ, et al. (2004). Virulence regulation and quorum sensing in staphylo- coccal infections: Competitive AgrC antagonists as quorum sensing inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 47(19), 4633–4641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chandler JR, and Dunny GM (2004). Enterococcal peptide sex pheromones: Synthesis and control of biological activity. Peptides 25(9), 1377–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandler JR, and Dunny GM (2008). Characterization of the sequence specificity determinants required for processing and control of sex pheromone by the intramembrane protease Eep and the plasmid-encoded protein PrgY. J. Bacteriol 190(4), 1172–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clewell DB, An FY, et al. (2000). Enterococcal sex pheromone precursors are part of signal sequences for surface lipoproteins. Mol. Microbiol 35(1), 246–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunman PM, Murphy E, et al. (2001). Transcription profiling-based identification of Staphylococcus aureus genes regulated by the agr and/or sarA loci. J. Bacteriol 183(24), 7341–7353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunny GM (2007). The peptide pheromone-inducible conjugation system of Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pCF10: Cell-cell signalling, gene transfer, complexity and evolution. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci 362(1483), 1185–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleming V, Feil E, et al. (2006). Agr interference between clinical Staphylococcus aureus strains in an insect model of virulence. J. Bacteriol 188(21), 7686–7688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujii T, Ingham C, et al. (2008). Two homologous Agr-like quorum-sensing systems cooperatively control adherence, cell morphology, and cell viability properties in Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. J. Bacteriol 190(23), 7655–7665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuqua C, and Greenberg EP (2002). Listening in on bacteria: Acyl-homoserine lactone signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 3(9), 685–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuqua C, Parsek MR, et al. (2001). Regulation of gene expression by cell-to-cell communication: Acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing. Annu. Rev. Genet 35, 439–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.George EA, Novick RP, et al. (2008). Cyclic peptide inhibitors of staphylococcal virulence prepared by Fmoc-based thiolactone peptide synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 130(14), 4914–4924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hedberg PJ, Leonard BA, et al. (1996). Identification and characterization of the genes of Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pCF10 involved in replication and in negative control of pheromone-inducible conjugation. Plasmid 35(1), 46–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jarraud S, Lyon GJ, et al. (2000). Exfoliatin-producing strains define a fourth agr specificity group in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol 182(22), 6517–6522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ji G, Beavis RC, et al. (1995). Cell density control of staphylococcal virulence mediated by an octapeptide pheromone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92(26), 12055–12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ji G, Beavis R, et al. (1997). Bacterial interference caused by autoinducing peptide variants. Science 276(5321), 2027–2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ji G, Pei W, et al. (2005). Staphylococcus intermedius produces a functional agr autoinducing peptide containing a cyclic lactone. J. Bacteriol 187(9), 3139–3150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalkum M, Lyon GJ, et al. (2003). Detection of secreted peptides by using hypothesisdriven multistage mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100(5), 2795–2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kavanaugh JS, Thoendel M, et al. (2007). A role for Type I signal peptidase in Staphylococcus aureus quorum-sensing. Mol. Microbiol 65, 780–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koenig RL, Ray JL, et al. (2004). Staphylococcus aureus AgrA binding to the RNAIII-agr regulatory region. J. Bacteriol 186(22), 7549–7555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lanigan-Gerdes S, Dooley AN, et al. (2007). Identification of subtilisin, Epr and Vpr as enzymes that produce CSF, an extracellular signalling peptide of Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol 65(5), 1321–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lanigan-Gerdes S, Briceno G, et al. (2008). Identification of residues important for cleavage of the extracellular signaling peptide CSF of Bacillus subtilis from its precursor protein. J. Bacteriol 190(20), 6668–6675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lazazzera BA (2001). The intracellular function of extracellular signaling peptides. Peptides 22(10), 1519–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lazazzera BA, Solomon JM, et al. (1997). An exported peptide functions intracellularly to contribute to cell density signaling in B. subtilis. Cell 89(6), 917–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lyon GJ, and Novick RP (2004). Peptide signaling in Staphylococcus aureus and other Gram-positive bacteria. Peptides 25(9), 1389–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lyon GJ, Mayville P, et al. (2000). Rational design of a global inhibitor of the virulence response in Staphylococcus aureus, based in part on localization of the site of inhibition to the receptor-histidine kinase, AgrC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97(24), 13330–13335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Magnuson R, Solomon J, et al. (1994). Biochemical and genetic characterization of a competence pheromone from B. subtilis. Cell 77(2), 207–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mylonakis E, Engelbert M, et al. (2002). The Enterococcus faecalis fsrB gene, a key component of the fsr quorum-sensing system, is associated with virulence in the rabbit endophthalmitis model. Infect. Immun 70(8), 4678–4681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakayama J, Chen S, et al. (2006). Revised model for Enterococcus faecalis fsr quorum-sensing system: The small open reading frame fsrD encodes the gelatinase biosynthesisactivating pheromone propeptide corresponding to staphylococcal agrd. J. Bacteriol 188(23), 8321–8326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakayama J, Tanaka E, et al. (2007). Siamycin attenuates fsr quorum sensing mediated by a gelatinase biosynthesis-activating pheromone in Enterococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol 189(4), 1358–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakayama J, Uemura Y, et al. (2009). Ambuic acid inhibits the biosynthesis of cyclic peptide quormones in Gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 53(2), 580–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Novick RP, and Geisinger E (2008). Quorum sensing in staphylococci. Annu. Rev. Genet 42, 541–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Novick RP, Ross HF, et al. (1993). Synthesis of staphylococcal virulence factors is controlled by a regulatory RNA molecule. EMBO J 12(10), 3967–3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohtani K, Yuan Y, et al. (2009). Virulence gene regulation by the agr system in Clostridium perfringens. J. Bacteriol 191(12), 3919–3927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okada M, Sato I, et al. (2005). Structure of the Bacillus subtilis quorum-sensing peptide pheromone ComX. Nat. Chem. Biol 1(1), 23–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Okada M, Yamaguchi H, et al. (2008). Chemical structure of posttranslational modification with a farnesyl group on tryptophan. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem 72(3), 914–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park J, Jagasia R, et al. (2007). Infection control by antibody disruption of bacterial quorum sensing signaling. Chem. Biol 14(10), 1119–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parsek MR, and Greenberg EP (2005). Sociomicrobiology: The connections between quorum sensing and biofilms. Trends Microbiol 13(1), 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pomerantsev AP, Pomerantseva OM, et al. (2009). PapR peptide maturation: Role of the NprB protease in Bacillus cereus 569 PlcR/PapR global gene regulation. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol 55(3), 361–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qin X, Singh KV, et al. (2000). Effects of Enterococcus faecalis fsr genes on production of gelatinase and a serine protease and virulence. Infect. Immun 68(5), 2579–2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qin X, Singh KV, et al. (2001). Characterization of fsr, a regulator controlling expression of gelatinase and serine protease in Enterococcus faecalis OG1RF. J. Bacteriol 183(11), 3372–3382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qiu R, Pei W, et al. (2005). Identification of the putative staphylococcal AgrB catalytic residues involving the proteolytic cleavage of AgrD to generate autoinducing peptide. J. Biol. Chem 280(17), 16695–16704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Riedel CU, Monk IR, et al. (2009). AgrD-dependent quorum sensing affects biofilm formation, invasion, virulence and global gene expression profiles in Listeria monocytogenes. Mol. Microbiol 71(5), 1177–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rieu A, Weidmann S, et al. (2007). Agr system of Listeria monocytogenes EGD-e: Role in adherence and differential expression pattern. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 73(19), 6125–6133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sifri CD, Mylonakis E, et al. (2002). Virulence effect of Enterococcus faecalis protease genes and the quorum-sensing locus fsr in Caenorhabditis elegans and mice. Infect. Immun 70(10), 5647–5650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Slamti L, and Lereclus D (2002). A cell-cell signaling peptide activates the PlcR virulence regulon in bacteria of the Bacillus cereus group. EMBO J 21(17), 4550–4559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stein RL, Barbosa MD, et al. (2000). Kinetic and mechanistic studies of signal peptidase I from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 39(27), 7973–7983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stephenson S, Mueller C, et al. (2003). Molecular analysis of Phr peptide processing in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol 185(16), 4861–4871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sturme MH, Nakayama J, et al. (2005). An agr-like two-component regulatory system in Lactobacillus plantarum is involved in production of a novel cyclic peptide and regulation of adherence. J. Bacteriol 187(15), 5224–5235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thoendel M, and Horswill AR (2009). Identification of Staphylococcus aureus AgrD residues required for autoinducing peptide biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem 284(33), 21828–21838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tortosa P, Logsdon L, et al. (2001). Specificity and genetic polymorphism of the Bacillus competence quorum-sensing system. J. Bacteriol 183(2), 451–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Waters CM, and Bassler BL (2005). Quorum sensing: Cell-to-cell communication in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 21, 319–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weinrauch Y, Msadek T, et al. (1991). Sequence and properties of comQ, a new competence regulatory gene of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol 173(18), 5685–5693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wright JS 3rd, Jin R, et al. (2005). Transient interference with staphylococcal quorum sensing blocks abscess formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102(5), 1691–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wuster A, and Babu MM (2008). Conservation and evolutionary dynamics of the agr cellto-cell communication system across firmicutes. J. Bacteriol 190(2), 743–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang L, Gray L, et al. (2002). Transmembrane topology of AgrB, the protein involved in the post-translational modification of AgrD in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem 277(38), 34736–34742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang L, Lin J, et al. (2004). Membrane anchoring of the AgrD N-terminal amphipathic region is required for its processing to produce a quorum-sensing pheromone in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem 279(19), 19448–19456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]