SUMMARY

Energy homeostasis requires precise measurement of the quantity and quality of ingested food. The vagus nerve innervates the gut and can detect diverse interoceptive cues, but the identity of the key sensory neurons and corresponding signals that regulate food intake remains unknown. Here we use an approach for target-specific, single-cell RNA sequencing to generate a map of the vagal cell types that innervate the gastrointestinal tract. We show that unique molecular markers identify vagal neurons with distinct innervation patterns, sensory endings, and function. Surprisingly, we find that food intake is most sensitive to stimulation of mechanoreceptors in the intestine, whereas nutrient-activated mucosal afferents have no effect. Peripheral manipulations combined with central recordings reveal that intestinal mechanoreceptors, but not other cell types, potently and durably inhibit hunger-promoting AgRP neurons in the hypothalamus. These findings identify a key role for intestinal mechanoreceptors in the regulation of feeding.

Graphical Abstract

A molecular map of vagal sensory neurons innervating the abdominal viscera Molecular identity correlates with innervation pattern and axon terminal morphology Stimulation of vagal IGLE mechanoreceptors, but not mucosal endings, inhibits feeding Intestine distension or mechanoreceptor activation inhibits hypothalamic AgRP neurons

A single cell approach cataloging the sensory neurons in the vagus nerve identifies populations that suppress hunger through mechanosensation in the intestine.

INTRODUCTION

The size of each meal is tightly regulated by a physiologic system that measures the quantity and quality of ingested food (Chambers et al., 2013; Cummings and Overduin, 2007; Grill and Hayes, 2012). This measurement happens primarily in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, but the identity of the key cells, signals, and pathways remains poorly defined.

The vagus nerve contains the primary sensory neurons that monitor GI signals (Berthoud and Neuhuber, 2000; Dockray, 2013; Travagli and Anselmi, 2016). Vagal sensory neurons have cell bodies located in nodose ganglia and axons that bifurcate into two branches, one of which innervates visceral organs and the other of which projects to the brainstem. Vagal afferents are anatomically heterogeneous, and their peripheral axons form characteristic sensory endings that are specialized for detection of chemical (mucosal endings) or mechanical (primarily intraganglionic laminar endings, or IGLEs) stimuli (Berthoud et al., 2004; Brookes et al., 2013). Within these broad classes, electrophysiological studies have revealed a diversity of response properties, including cells that respond to hormones, GI luminal nutrients, osmolytes, pH, GI distension or luminal stroking (Berthoud and Neuhuber, 2000; Brookes et al., 2013; Dockray, 2013; Grundy and Scratcherd, 1989). Thus vagal afferents represent a diverse class of sensory neurons that survey the gastrointestinal milieu and relay this information to brain.

Given their sensory capabilities, vagal afferents are uniquely positioned to regulate food intake. One way this is thought to occur is through hormones, such as cholecystokinin (CCK), peptide YY (PYY), and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), which are secreted from enteroendocrine cells in the intestine in response to nutrient ingestion (Dockray, 2013). These hormones can directly modulate vagal afferent terminals within the intestinal mucosa that are in proximity to (or direct synaptic contact with) enteroendocrine cells (Berthoud and Patterson, 1996; Kaelberer et al., 2018). Food intake also results in gastric distension, which can stimulate vagal sensory neurons with mechanosensitive IGLEs innervating the muscular layer of the stomach (Williams et al., 2016; Zagorodnyuk et al., 2001). This gastric distension signal may, in combination with vagal signals of nutrients arising from the intestine, contribute to the emergence of satiation during a meal (Berthoud, 2008; Cummings and Overduin, 2007; Powley et al., 2005).

Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether these mechanisms can fully account for how satiation is naturally regulated (Woods et al., 2018). One fundamental obstacle has been the absence of techniques for manipulating the vagus with cell-type-specificity in awake, behaving animals. Traditional approaches, such as surgical or chemical vagotomy (Berthoud, 2008) or bulk stimulation (Browning et al., 2017; Han et al., 2018), do not target individual pathways that carry specific types of information, and consequently cannot be used to test their causal role in behavior.

We reasoned that if we could identify genetic markers for functionally-distinct populations of vagal neurons, and then manipulate their activity during behavior, this might provide new insight into the nature of the gastrointestinal signals that regulate food intake. A similar approach has been applied to study the role of the vagus in autonomic reflexes (Chang et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2016), but to date the effect of manipulating vagal cell types on behavior has not been described. Here, we have used target-guided, single-cell sequencing to generate a molecular map of vagal sensory cell types that innervate the GI tract, and then systematically characterized their innervation pattern, terminal morphology, and behavioral and autonomic functions. This has revealed an unexpected role for intestinal mechanoreceptors in the regulation of feeding.

RESULTS

Anatomical characterization of vagal sensory neurons that innervate GI tract

We set out to relate the molecular identity of vagal sensory neurons to their anatomy and function. As a first step, we catalogued the innervation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract by vagal afferents with different terminal morphologies. We injected AAV9-DIO-tdTomato bilaterally into the nodose ganglia of vGlut2Cre mice, which resulted in tdTomato expression in the majority of vagal sensory neurons but not vagal motor neurons in the brainstem (Figure 1A, S1A–S1C). We then quantified the innervation of different parts of the GI tract by whole-mount staining and imaging.

Figure 1. Anatomical characterization of vagal sensory neurons that innervate the GI tract.

(A) Anterograde tracing strategy.

(B-C) Schematic for the distribution (B) or morphology (C) of vagal sensory terminals.

(D-H) Whole-mount (D-F and H, top-down view) and cross sections (G) showing the innervation of tdTomato+ vagal sensory terminals (magenta) in different tissues. Autofluorescence in the UV channel (gray) shows villi or crypts. FluoroGold (green) labels enteric neurons.

(I-L) Distribution of tdTomato+ vagal sensory terminals (mean ± SEM).

(M) Schematic of the two ways vagal-GI innervation could be organized.

(N-O) Whole-mount nodose ganglion showing segregation of vagal sensory neurons that are retrogradely labeled from different GI targets (N) and quantification (O).

Scale bar: 100 μm. See also Figure S1.

In the stomach, we observed three types of classical sensory endings with distinct patterns of innervation (Figure 1B and 1C) (Fox et al., 2000; Wang and Powley, 2000). Intraganglionic laminar endings (IGLEs), which are thought to be the mechanoreceptors detecting GI stretch (Berthoud and Neuhuber, 2000; Williams et al., 2016; Zagorodnyuk et al., 2001), densely innervated the antrum, fundus, and the greater curvature of corpus (Figure 1D and 1I). A second type of putative mechanoreceptor, intramuscular arrays (IMAs), showed highly restricted innervation near pyloric antrum and cardiac sphincter, and were sparser across the rest of the stomach (Figure 1F). The mucosal endings of putative chemosensory vagal terminals were restricted to the antrum and corpus, with the highest density near the cardiac sphincter (Figure 1E, 1K, and S1D). Those mucosal afferents may also be responsive to gentle luminal stroking, but are not activated by innocuous GI distension (Grundy and Scratcherd, 1989). In the intestine, we observed the highest density of IGLEs and mucosal endings proximal to the pylorus, consistent with prior reports (Berthoud et al., 2004; Fox et al., 2000; Wang and Powley, 2000), but both endings were also distributed throughout the entire length of the intestine, including the large intestine (Figure 1D, 1E, 1H–1L).

We also examined visceral organs other than the GI tract. Vagal innervation of the portal vein has been proposed to contribute to metabolic regulation by detecting absorbed nutrients en route from the intestine to the liver (Berthoud et al., 1992). Consistent with this possibility, we observed sparse vagal-derived tdTomato+ fibers running along the portal blood vessels and nearby medial lobe of liver (Figure 1G). We also observed occasional vagal fibers in the gallbladder, but not the pancreas (data not shown). The sparsity of this innervation indicates that the vast majority of subdiaphragmatic vagal sensory neurons innervate either the stomach or intestine.

To test whether these regions receive innervation from distinct sets of vagal sensory neurons, we performed dual-color retrograde tracing by injecting fluorescent tracers into combinations of five targets and then quantifying overlap in nodose ganglion (Figure 1M–1O and S1H). Only a small percentage of vagal sensory neurons were double labeled by injections into any two different sites (ranging from 3% to 17%). In contrast, tracer injection into the same structure tended to label the same cells (ranging from 86% to 97%), and control experiments confirmed that, in the periphery, fluorescent tracers were restricted to the injection site (Figure S1E–S1G). This indicates that different regions of the GI tract are innervated by different vagal sensory neurons.

Target-scSeq identifies vagal cell types innervating distinct visceral organs

To identify the vagal sensory cell types innervating different regions of the GI tract, we performed RNA sequencing of individual cells retrogradely labeled from different peripheral innervation targets (target-scSeq) (Y.L., A.D., and M.A.K, in preparation). We injected a retrograde tracer into different sites within the abdominal viscera and then manually picked 501 fluorescently labeled vagal sensory neurons from nodose ganglion of 34 mice (Figure 2A). After filtering out samples that produced low quality sequencing data, we obtained 395 single cell profiles for analysis, with an average of 1.72 million mapped reads per cells (Figure S2A–S2E).

Figure 2. Target-scSeq identifies vagal cell types innervating distinct visceral organs.

(A) Target-scSeq strategy.

(B-C) Spectral tSNE colored by gene-based clusters (B) or retrograde-tracing targets (C).

(D-E) Percentage of cells retrogradely labeled from different targets within individual clusters (D), or vice versa (E).

(F) The relative expression of subtype-enriched genes (rows) across cells sorted by cluster (column).

(G) Dendrogram showing relatedness of clusters, followed by violin plots showing the expression of cluster-specific marker genes.

(H) Immunostaining reveals the overlap between vagal cell-type markers (magenta) and retrograde tracer (green).

(I) RNAscope reveals that Gpr65+ cells are partially labeled by Dbh (t10-t12) and Edn3 (t09).

(J) Quantification of (H), showing the percentage of stomach- or intestine-projecting cells that express each marker gene (mean ± SEM).

(K) Quantification of (I), n = 4 mice.

Scale bar: 100 μm. See also Figure S2.

We first performed unsupervised graph clustering based on the gene expression profiles and identified 12 sets of genetically distinct subdiaphragmatic vagal sensory neurons (Figure 2B, S2F–S2H). For most of clusters, we were able to identify individual genes that function as unique markers, including: t01 (Oxtr+), t02 (Olfr78+), t03 (Npas1a+), t04 (Sst+), t05 (Calca+), t06 (Vip+/Uts2b+), t07 (Prom1+), and t09 (Edn3+). Other clusters lacked a single unique marker but could be identified by the combined expression of two or more genes (Figure 2G and S2L).

Many of these purely gene expression-based clusters were associated with a unique pattern of putative gastrointestinal innervation (Figure 2B–2E, S2I and S2J). Seven clusters are mainly composed of neurons labelled by injection into one or two of the visceral organs: t04 and t05 were highly enriched in neurons labelled by stomach injection (59% and 77% respectively); t12, t9, t8 were enriched in neurons labelled by injection into proximal intestine (79%), middle/distal intestine (73%), or large intestine (57%), respectively; and t01 and t03 were enriched in cells labeled by injection into stomach or large intestine (54% and 76%, respectively). Finally, three clusters, t06, t07, and t11, contained cells that were labelled by injection into many targets, suggesting that these clusters may identify vagal neurons with broad projection patterns.

The correspondence between the gene-based clustering and the retrograde tracing targets (Figure 2B–2E) suggests that these clusters identify cell types with organ-specific projection patterns. To confirm this, we injected retrograde tracers into visceral organs and then quantified their overlap in nodose ganglion with marker genes identified by target-scSeq (Figure 2H and 2J). We identified Sst and Calca as markers for putative stomach-projecting neurons in clusters t04 and t05, and, consistent with this, we found that Sst and Calca each labelled approximately 10% of stomach-projecting vagal neurons but less than 1% of neurons retrogradely labeled from intestine. Likewise, Uts2b was identified as a marker for cells in cluster t06 that broadly innervate the intestine, and this marker co-localized with tracer injected into the intestine but not the stomach. Our data also revealed heterogeneity in the previously identified markers Glp1r and Gpr65 (Williams et al., 2016), which marked neurons labelled by tracers injected into both stomach and intestine (Figure 2G–2K, and S4K). This demonstrates that target-scSeq can robustly link the anatomy of sensory neurons to their molecular identity.

Comparison of whole-nodose and target-scSeq reveals the organization of vagal sensory subtypes

In addition to the abdominal viscera, vagal sensory neurons also innervate the heart, lung and other supradiaphragmatic targets. To place our target-scSeq data in this broader context, we next performed unbiased, droplet-based scSeq of the entire nodose ganglion. We sequenced 1108 individual cells from the nodose ganglion of adult mice, removed low-quality cells and non-neuronal cells (Figure S3A–S3E) (Kupari et al., 2019), and obtained 956 vagal sensory neurons for subsequent analysis. Next, we merged this whole nodose-scSeq with the GI target-scSeq datasets, and performed integrated clustering analysis based on gene expression (Stuart et al., 2019). This revealed 27 clusters of vagal sensory cell types (n1–27; Figure 3A), each associated with the expression of unique marker genes (Figure 3D–3H and S3F). 17 of the clusters are putative subdiaphragmatic vagal sensory subtypes (n9–20 and 22–26), based on the fact that (1) more than 10% of cells in each of these subdiaphragmatic clusters is derived from the GI target-scSeq (Figure S3H) and (2) each cluster is defined by marker genes that are also expressed in one or two of the GI target-scSeq clusters (Figure 3E). On the other hand, 10 clusters lacked cells from the GI target-scSeq or were labeled by marker genes not expressed in the target-scSeq (n1–8, 21, and 27; Figure 3E and S3H), suggesting they contain cells with supradiaphragmatic innervation.

Figure 3. Comparison of whole-nodose and target-scSeq reveals the global organization of vagal sensory subtypes.

(A) Spectral tSNE plot shows gene-based clusters, combining GI target-scSeq and unbiased whole-nodose scSeq.

(B-C) tSNE plots (left) or stacked bar graphs (right) showing neurons in each cluster that originated from individual target-scSeq clusters (B), or were labeled from individual GI targets (C).

(D-H) Dendrogram showing relatedness of clusters (D), followed by violin plots showing gene expression across clusters of combined nodose scSeq (top, n1-n27) and GI target-scSeq (bottom, t01-t12) (E-H). Genes included are cluster markers of combined scSeq (E), markers enriched or excluded in subdiaphragmatic clusters (F), markers used for later anatomical characterizations (G), and genes listed in prior literature (H). Blue shadow marks putative subdiaphragmatic clusters from the combined whole-nodose scSeq.

See also Figure S3.

We also identified genes that are broadly enriched in, or excluded from, the vagal sensory subtypes that project to the abdominal viscera (Figure 3F). For example, Scn10a and Fxyd2 were enriched in all 17 putative subdiaphragmatic clusters, but were excluded from most non-subdiaphragmatic clusters. In contrast Fxyd7 was highly expressed in all non-subdiaphragmatic clusters but only weakly expressed in a small subset of abdominal clusters (n19, 20, 23, and 26). Thus, these marker genes identify vagal sensory neurons based on their pattern of innervation above or below the diaphragm and may provide useful genetic access to these broad subsets of cells.

Genetic identification of vagal subtypes with unique morphologies and innervation patterns

We next used the genetic markers identified by ScSeq to determine the terminal morphology and innervation targets of a panel of vagal neuron subtypes. For this purpose we characterized six Cre mouse lines predicted to label distinct subsets of vagal sensory neurons (Uts2b, Oxtr, Vip, Sst, Calca, and Nav1.8) as well as two lines that label previously characterized populations (Gpr65 and Glp1r). We then visualized the anatomy of these cell types by bilateral injection of AAV9-DIO-tdTomato into nodose ganglia of the corresponding Cre driver mice, which captures the expression pattern of these marker genes in the adult. The visceral innervation pattern of these cells was then cataloged by quantitative histological analysis and benchmarked to the innervation of Vglut2Cre mice, which labels all vagal sensory neurons (Figure 4G).

Figure 4. Genetic markers identify vagal subtypes with unique morphologies and innervation patterns.

(A-F) Distribution of gastric mucosal endings (A-D), intestinal mucosal endings (C-D), and gastrointestinal IGLEs (E-F) labeled by seven nodose-subtype Cre lines. (A, C, E) Schematic of distribution. (B, D, F) Top-down view of whole-mount GI tissue. Magenta: tdTomato+ vagal sensory terminals. Gray: villi visualized by the autofluorescence in UV channel. Green: FluoroGold-labeled enteric neurons.

(G) Quantification of mucosal ending- and IGLE-distributions labeled by vGlut2Cre, Nav1.8Cre, and the seven nodose-subtype Cre lines (mean ± SEM).

Scale bar: 100 μm. See also Figure S4.

Sst and Calca are predicted to label two populations of neurons innervating the stomach based on our ScSeq data (t04 and t05, respectively; Figure 2B–2D and 2G). Consistent with this, we found that SstCre and CalcaCreER both label vagal sensory neurons that are mainly restricted to the stomach. These two cell types form mucosal endings innervating gastric villi, but do so with distinct topography (Figure 4A, 4B, and 4G). Sst+ mucosal endings are enriched in the pyloric antrum and very sparse in the stomach corpus. In contrast, Calca+ neurons form extensive villi innervation near the lesser curvature of the corpus, with density dramatically decreased near the pyloric antrum and greater curvature of the corpus. A subset of Calca+ neurons also forms IMAs near the gastric antrum and large intestine (Figure S4K). Staining of cell bodies in the nodose ganglion further confirmed that the Sst+ and Calca+ neurons are non-overlapping (Figure S4A and S4B). Thus Sst and Calca define distinct subtypes of gastric mucosal-ending neurons with unique innervation patterns.

The intestine is also densely innervated by mucosal endings (Figure 1K and 1L) (Berthoud et al., 2004). We observed expression of the mucosal marker Gpr65 (Williams et al., 2016) in five clusters with broad intestinal projections (t08–12) (Figure 2I, 2K, and S2K) as well as in the Sst+ gastric mucosal-ending cluster (t04) (Figure S4A). Consistently, dense Gpr65+ mucosal endings were found in the stomach with a distribution that resembles the Sst+ cells (Figure 4A, 4B, and 4G). We also found that Gpr65+ mucosal endings innervate not only proximal intestine but also middle and distal intestine, accounting for approximately a third of total mucosal endings in the latter two regions (Figure 4C, 4D, and 4G). Thus Gpr65 labels multiple subtypes of mucosal-ending vagal afferents distributed across the entire GI tract.

The marker genes Vip and Uts2b identify a fourth type of mucosal ending neurons in our target-scSeq data. Visualization of these cells using VipCre mice revealed that they exclusively innervate the intestinal villi and were evenly distributed across proximal, middle, and distal intestine (Figure 4C, 4D, and 4G). We confirmed this by generating a Uts2bCre mouse (Figure S2M–S2S), which showed an identical pattern of labelling (Figure 4D and 4G). Vip/Uts2b expression showed no overlap with the other intestinal mucosal ending marker, Gpr65 (Figure S4A and S4E–S4F), indicating that the t06 Vip/Uts2b+ cluster defines a unique population of sensory neurons that innervates small intestine villi.

In addition to the diversity of mucosal ending neurons, we observed multiple cell types forming mechanosensitive IGLEs. Beyond the previously identified IGLE marker gene Glp1r, we found that OxtrCre exclusively labels neurons that form IGLEs (Figure 4F). Both Oxtr and Glp1r are expressed in the cluster t01 (Figure 2G), but are mutually excluded from each other (Figure S4A and S4I), suggesting they may label distinct subtype of cells. Indeed, quantitative examination of their anatomy revealed that Oxtr+ IGLEs are largely restricted to the intestine, with the highest density in the proximal intestine, whereas Glp1r+ IGLEs extensively innervate the stomach but not the intestine (Figure 4E–4G). Thus Oxtr and Glp1r identify two distinct subsets of IGLE mechanoreceptors with different innervation patterns in the abdominal viscera.

Activation of gastrointestinal mechanoreceptors potently inhibits food intake

The identity of the vagal cell types that regulate feeding is unknown. To investigate this, we selected two sets of mucosal-ending neurons (VipCre and Gpr65Cre) and two sets of IGLE mechanoreceptors (OxtrCre and Glp1RCre) for functional analysis (Figure 5B). Three of these cell types (Vip+, Oxtr+, Glp1r+) express Cckar and all four express Htr3a, indicating that they are poised to receive nutritional signals from the gut (Figure 5A and S5A). We then targeted the excitatory opsin ChR2 to these cells and installed an optical fiber above the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) for selective photostimulation of their central terminals (Figure 5C–5E).

Figure 5. Activation of gastrointestinal mechanoreceptors potently inhibits food intake.

(A) Expression of hormonal receptors and Trpv1 across target-scSeq clusters.

(B) Summary of the four vagal Cre lines for functional analysis.

(C) Optogenetic activation strategy.

(D-E) ChR2-mCherry expression in the vagal sensory cell bodies (D) and their central terminals in the NTS and AP (E).

(F-I) Cumulative food intake (F-H) or water intake (I) comparing trials with and without photostimulation across the four vagal-ChR2 lines and control (no ChR2). Blue indicates the period of photostimulation.

(J) Chemogenetic activation strategy.

(K) hM3D-mCherry expression in the vagal sensory cell bodies.

(L-O) Cumulative food intake (L-N) or water intake (O) comparing trials with CNO or saline treatment across the four vagal-hM3D lines and control (no hM3D).

(P) Place-preference assay.

(Q-R) Percentage of time spent in photostimulation-paired chamber, comparing baseline and the third stimulation session, using fasted (Q) or fed (R) mice.

(S-T) Cumulative food intake (S) or water intake (T) tested 30min after CNO or saline treatment. Error bars and shaded areas represent mean ± SEM. N mice is annotated within figures. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA, Sidak correction.

Scale bar: 100 μm. See also Figure S5.

We first measured food intake in overnight-fasted mice. The Vip+ t06 cluster showed the highest expression of Cckar in our sequencing data (Figure 5A and S5A), and Gpr65+ neurons are activated by nutrients in the intestinal lumen (Williams et al., 2016). However, we observed no effect on food intake following optogenetic stimulation of either Vip+ or Gpr65+ neurons (Figure 5F–5H). To confirm this result, we targeted the chemogenetic actuator hM3Dq to these two cell types and treated mice with clozapine-N-oxide (CNO). This increased Fos expression in the brainstem targets of these vagal neurons (Figure S5D), but again had no effect on food intake in either fasted or fed animals (Figure 5J–5N and 5S). Thus activation of Vip+ or Gpr65+ mucosal-ending neurons is not sufficient to modulate feeding.

Gastric distension is thought to be an important signal that promotes meal termination (Phillips and Powley, 1996). A subset of Glp1r+ neurons are IGLE mechanoreceptors that innervate the stomach and are activated by gastric distension (Williams et al., 2016), suggesting that these cells may contribute to stretch-induced meal termination. Consistent with this, we observed a partial reduction in food intake following either optogenetic (Figure 5F–5H) or chemogenetic (Figure 5L, 5M, and 5S) stimulation of Glp1r+ neurons. Although Glp1r is also expressed in intestine-innervating cells that form mucosal endings (Vip/Uts2b+ t06 cluster, Figure 2G, S4A, S4G–S4H), these cells are unlikely to account for the suppression of feeding by Glp1r+ neurons, as stimulation of Vip+ neurons alone had no effect on behavior (Figure 5F–5H and 5L–5N).

In addition to the stomach, IGLE mechanoreceptors also innervate the intestine (Figure 1I), but their potential role in feeding has received little attention (Berthoud, 2008; Cummings and Overduin, 2007). The identification of Oxtr as a specific marker for intestinal IGLEs (Figure 4E–4G) permits us to directly examine their function in vivo. To our surprise, we found that both optogenetic and chemogenetic stimulation of vagal Oxtr neurons dramatically reduced food intake (Figure 5F, 5G, 5L, and 5M). This effect was rapidly reversible, as feeding rebounded shortly after optogenetic stimulation was terminated (Figure 5H). This suggests that mechanical signals from the intestine, such as distension, may regulate feeding by acting through Oxtr+ neurons.

Food intake can also be influenced by a variety of indirect or non-specific mechanisms. To probe the specificity of the feeding suppression induced by Oxtr+ and Glp1r+ neurons, we characterized the effect of activating these and other neurons in a battery of behavioral and physiological tests. First, we investigated the valence of these vagal sensory subtypes using a closed-loop place-preference assay, in which optogenetic activation is coupled with occupancy of one side of a two chamber arena. Mice failed to develop preference for either side of the chamber throughout multiple days of testing in either fasted or fed conditions, indicating that activation of these neurons induces neither real-time nor conditioned place preference (Figure 5P–5R).

In addition to feeding, vagal afferents have also been implicated in the regulation of thirst, digestion, body temperature, and blood pressure (Hanyu et al., 1990; Madden et al., 2017; Masclee et al., 1990; Szekely, 2000; Watanabe et al., 2010; Zimmerman et al., 2019). We found that optogenetic activation of Oxtr+ and Glp1r+ neurons had no effect on drinking after overnight water deprivation (Figure 5I and S5E), whereas chemogenetic stimulation of Oxtr+ neurons did cause a decrease in water intake (Figure 5O, 5T and S5F). This suggests that the ability of these cells to reduce drinking depends on the strength of stimulation. We also failed to observe any changes in body temperature or blood pressure following optogenetic stimulation of any of these vagal subtypes (Figure S5G–S5I). CCK is well known for regulating bile acid secretion from the gallbladder (Spellman et al., 1979) and three of these subtypes express the Cckar, but we observed no effect on gallbladder emptying following chemogenetic stimulation of any of these neurons (Figure S5B and S5C). Taken together, these data suggest that the effects of Oxtr+ and Glp1r+ neuron stimulation on feeding are unlikely to be secondary to malaise or broader physiological changes.

Stimulation of gastrointestinal mechanoreceptors modulates feeding centers in the brain

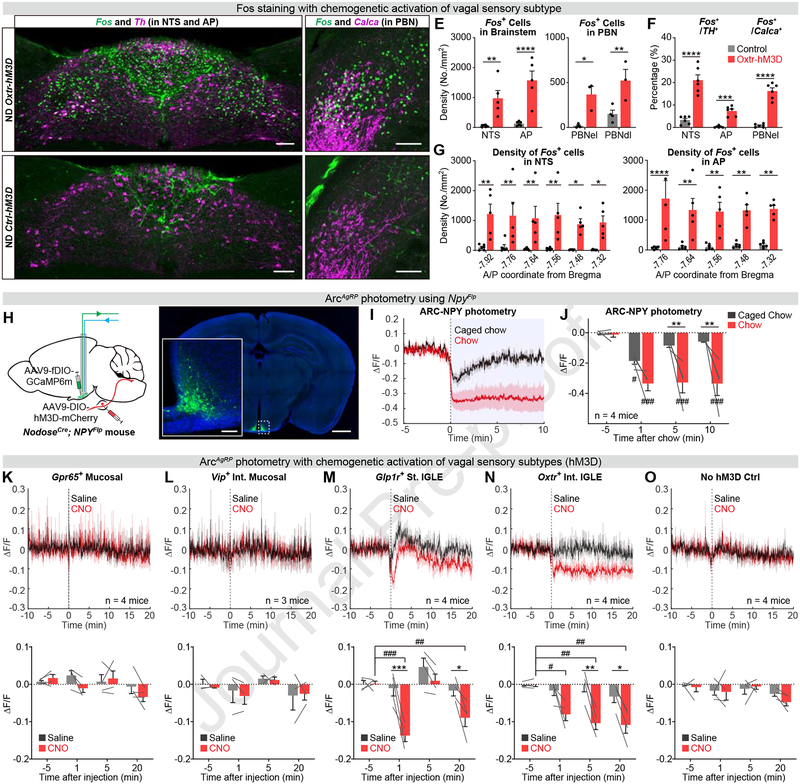

We next investigated how these vagal signals of GI distension are represented in the brain. The caudal NTS and area postrema (AP) receive direct innervation from vagal sensory neurons and are known to be critical for satiation (Berthoud and Neuhuber, 2000; Grill and Hayes, 2012). Consistent with this, we observed robust induction of Fos expression in both regions following stimulation of Oxtr+ neurons (Figure 6E, 6G, S6A, and S6B). The Fos expression induced in the NTS co-localized extensively with tyrosine hydroxylase (Th), which marks a subset of NTS neurons that promote satiation (Figure 6A, 6B, and 6F) (Kreisler et al., 2014; Maniscalco and Rinaman, 2013; Roman et al., 2016). The parabrachial nuclei (PBN) also control food intake and receive ascending sensory inputs from the NTS/AP. Consistently, we observed extensive Fos expression in the PBN following stimulation of Oxtr+ neurons (Figure S6C and S6D). A subset of Fos+ neurons were localized to the external lateral PBN (PBNel) and overlapped with appetite-inhibiting Calca+ neurons (Figure 6C–6F) (Campos et al., 2016). Additionally we also noticed many Fos+ neurons in the dorsal lateral PBN (PBNdl) (Figure 6E, S6C and S6D), a region that shows high Fos expression following treatment with CCK but not LiCl (Han et al., 2018).

Figure 6. Stimulation of gastrointestinal mechanoreceptors modulates feeding centers in the brain.

(A-G) Immunostaining of Fos and Th in the NTS/AP (A-B), Fos and Calca in the PBN (C-D), and quantification (E-G), comparing Oxtr-hM3D and control mice after CNO treatment.

(H) Concurrent Arc-photometry recording and vagal sensory neuron activation (left). The expression of GCaMP6m is restricted within the Arc (right).

(I-J) Normalized AgRP neuron calcium signal in fasted mice presented with chow and caged chow (I) and quantification (J).

(K-O) Normalized AgRP neuron calcium signal in fasted mice after CNO or saline treatment (top) and quantification (bottom), across the four vagal-hM3D lines or control.

Values are reported as mean ± SEM. Comparisons were made between groups (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) or from baseline (#P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001), two-way ANOVA, Sidak correction.

Scale bar: 100 μm (A-D) or 1 mm (H). See also Figure S6.

In addition to the hindbrain, the hypothalamus is also critical for the regulation of food intake. Hunger-promoting Agouti-related Peptide (AgRP) neurons in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) are activated by food deprivation and inhibited by GI nutrients (Beutler et al., 2017; Hahn et al., 1998; Su et al., 2017). To monitor AgRP neurons while simultaneously manipulating vagal neuron subtypes, we targeted expression of GCaMP6m to AgRP neurons by using NpyFlp mice (which labels AgRP neurons in the ARC) and independently targeted expression of hM3Dq to vagal sensory neurons by using the corresponding Cre drivers (Figure 6H–J).

Although AgRP neurons are potently inhibited by intragastric nutrients (Beutler et al., 2017; Su et al., 2017), we observed no change in their activity following stimulation of nutrient-activated Gpr65+ neurons (Figure 6K). We likewise observed no response of AgRP neurons to stimulation of Vip+ neurons, a distinct population of cells that innervate the intestinal mucosa and highly express Cckar (Figure 6L). In contrast, AgRP neurons were rapidly inhibited by activation of IGLE mechanoreceptors innervating the stomach (Glp1r+) and intestine (Oxtr+) (Figure 6M–6O). Interestingly, these two mechanoreceptor subtypes inhibited AgRP neurons with different kinetics. Stimulation of stomach-innervating Glp1r+ neurons caused a rapid but transient reduction of AgRP neuron activity, whereas stimulation of intestine-innervating Oxtr+ neurons induced a rapid and sustained response. Stimulation of Oxtr+ neurons also strongly attenuated the response of AgRP neurons to the sensory detection of food, whereas stimulation of other vagal subtypes including Glp1r+ had no effect (Figure S6E–S6H). The relative inhibition of AgRP neurons by these vagal subtypes mirrored their ability to inhibit food intake (Figure S6F). Thus these data reveal that hypothalamic feeding circuits are modulated specifically by mechanoreceptors in the stomach and intestine.

Gastrointestinal distension is sufficient to inhibit food intake and AgRP neuron activity

Prior work has emphasized the importance of nutrients rather than stretch in regulating AgRP neurons (Beutler et al., 2017; Su et al., 2017). More broadly, studies of the role of stretch in ingestive behavior have traditionally focused on the stomach, not the intestine (Cummings and Overduin, 2007; Phillips and Powley, 1996). To find conditions that would allow us to manipulate stomach or intestinal volume preferentially in awake animals, we considered the possibility that the level of gastric versus intestinal distension may differ depending on the substance ingested and its kinetics of distribution in the GI tract. To explore this, we delivered a panel of solutions to the stomach by oral gavage and then measured the contents of the stomach and different segments of the intestine five minutes later (Figure 7A, and S7A–S7E). We found that lipid and glucose induced a significant increase of fluid content of the stomach and/or proximal intestine, whereas hyperosmolar, non-nutritive solutions, including hypertonic saline and mannitol, induced a more dramatic increase in the fluid content of the middle intestine. By contrast, methylcellulose, a highly viscous solution, only increased the contents of the stomach. Thus gastric delivery of these non-nutritive substances makes it possible to differentially introduce stomach versus intestinal fill.

Figure 7. Gastrointestinal distension is sufficient to inhibit food intake and regulate AgRP neuron activity.

(A) Normalized weight of GI contents measured 5 min after sham treatment or oral gavage of 500 uL of various solutions.

(B-C) Cumulative (B) and total (C) food intake of fasted mice after oral gavage of 500 uL of various solutions.

(D-E) Average of normalized AgRP neuron calcium signal of fasted mice following oral gavage of 500 uL of various solutions (D) and quantification (E). Gray bars indicate the period of oral gavage.

(F-G) Average of normalized AgRP neuron calcium signal in fasted mice, after gastric or intestinal infusion of 1mL various solutions (F) and quantification (G). Gray bars indicate the infusion period.

Values are reported as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA, Sidak correction.

See also Figure S7.

We then tested whether filling the stomach or intestine with these substances would have a differential effect on food intake or AgRP neuron activity (Figure 7B–7E, and S7F). As expected, gavage of lipid and glucose inhibited AgRP neurons, as well as subsequent food intake, relative to controls (Beutler et al., 2017; Su et al., 2017). Strikingly, we also observed an inhibition of food intake and AgRP neuron activity following gastric delivery of hypertonic saline and mannitol, which induce marked intestinal distension but have no nutritive value. In contrast, gavage of cellulose, which induces gastric but not intestinal distension (Figure 7A), failed to modulate food intake or AgRP neuron activity. These effects of hyperosmotic solutions were not due to dehydration, because subcutaneous hypertonic saline had no effect on AgRP neuron activity or food consumption (Figure S7G–S7I), consistent with previous work showing that AgRP neurons are not modulated by water deprivation or drinking (Zimmerman et al., 2016). Thus the ability of non-nutritive substances to inhibit food intake and AgRP neurons correlates with their ability to fill the intestine, further suggesting a role for intestinal distension in these processes.

To test directly whether infusions that bypass the stomach can modulate AgRP neurons, we generated mice for photometry recordings of AgRP neurons and then equipped these mice with catheters that enable infusion into either the stomach or the duodenum. As before, we observed robust inhibition of AgRP neurons following intragastric infusion of lipid or glucose, as well as significant but weaker inhibition by mannitol (Figure 7F and 7G). Infusion of these three substances into the intestine also inhibited AgRP neurons, including importantly pronounced inhibition by non-nutritive mannitol (Figure 7F and 7G). Intestinal infusion also mimicked the ability of intragastric infusion to inhibit subsequent food intake and to attenuate the response of AgRP neurons to the sensory detection of food (Figure S7J–S7N). This demonstrates that gastric signals are not required for inhibition of AgRP neurons and, together with our optogenetic and chemogenetic findings, suggests a key role for intestinal distension in the regulation of feeding.

DISCUSSION

A central task of physiology is to explain how food intake reduces hunger. While many studies have emphasized the role of mechanical and chemical signals originating from the gut (Cummings and Overduin, 2007; Dockray, 2013), the identity and properties of the key sensory neurons that detect these signals has remained unclear. Here we have used an approach for target-guided, single-cell RNA sequencing to catalog the molecular identity of the vagal sensory neurons innervating the abdominal viscera. We then annotated these cell types by comprehensively characterizing their innervation patterns, sensory endings, and behavioral function. We found that food intake was most potently inhibited by vagal afferents that innervate the intestine and form IGLEs - the putative mechanoreceptors that sense intestinal stretch. Stimulation of these intestinal mechanoreceptors was sufficient to activate satiety-promoting pathways in the brainstem and inhibit hunger-promoting AgRP neurons in the hypothalamus. Consistently, increasing intestinal volume was sufficient to inhibit food intake and AgRP neuron activity even in the absence of nutrients. These findings demonstrate an unexpected role for intestinal distension in satiation, and provide genetic access to key sensory neurons that regulate food intake.

A genetic map of vagal afferents innervating the GI tract

Early anatomical and electrophysiological studies subdivided GI vagal afferents into three major types: the IGLEs, which innervate the muscle layer and respond to GI distension; the mucosal afferents, which innervate the mucosal membrane and are therefore adjacent to sites of hormone release; and the IMAs, a less common subtype that may be activated by GI stretch but has not been functionally characterized (Berthoud and Neuhuber, 2000; Brookes et al., 2013). However it has remained unclear to what extent subsets of these broad classes of vagal afferents exist that have distinct molecular identities, innervation patterns, and physiological functions. Addressing this question requires not only cataloging the molecular diversity of vagal neurons (Kupari et al., 2019) but also systematically linking that molecular heterogeneity to anatomy and function.

Here we have used a combination of target-specific and whole-nodose scSeq to comprehensively identify the vagal sensory neurons that innervate the abdominal viscera. We then used genetic tools to characterize their morphology, innervation pattern, and function. This revealed a diversity of molecularly and functionally distinct cell types. For example, we have identified three novel vagal cell types that form mucosal endings: Sst+ and Calca+ neurons that innervate different parts of the stomach, and Vip+ neurons that innervate the intestine. These three cell types are distinct from the previously identified Gpr65+ mucosal ending neurons that innervate the proximal intestine (Williams et al., 2016), and all four of these cell types express different combinations of receptors for nutritionally-regulated hormones. We similarly show that major subsets of the IGLEs within the stomach and intestine can be defined by the molecular markers Glp1r and Oxtr, respectively. These findings provide a roadmap for the use of genetic tools to monitor and manipulate vagal cell types with high specificity, thereby allowing systematic analysis of their physiologic function.

Regulation of feeding by IGLE mechanoreceptors

The vagus nerve is thought to be critical for satiation, yet the causal role of specific vagal cell types in the control of feeding behavior has not been tested. To investigate this, we selected four vagal subtypes that differ in their innervation pattern (stomach versus intestine), sensory endings (IGLE versus mucosal), and hormone receptor profiles (including receptors for CCK, PYY, and 5HT). We manipulated the activity of these cells using optogenetics and chemogenetics, and measured the response in a battery of behavioral and physiological assays.

We found that feeding was potently inhibited by stimulation of Oxtr+ vagal neurons, which represent IGLE mechanoreceptors innervating the intestine. Stimulation of Glp1r+ neurons, which cover the majority of gastric IGLE mechanoreceptors, also attenuated feeding but to a lesser extent. This weaker inhibition of feeding by Glp1r+ neurons was somewhat unexpected, given that artificial distension of the stomach is well-known to promote meal termination (Phillips and Powley, 1996). However, this discrepancy could reflect differences in the intensity of stimulation, or the involvement of compensatory autonomic reflexes that could attenuate the effect of neural stimulation but not mechanical distension of the tissue.

In contrast to the mechanoreceptors, we observed no phenotype following stimulation of two intestine-innervating, mucosal-ending vagal subtypes predicted to be important for the regulation of food intake: Gpr65+ neurons, which are activated by intestinal nutrients (Williams et al., 2016), and Vip+ neurons, which had the highest expression of the Cckar in our sequencing data. This suggests that Gpr65+ and Vip+ mucosal afferents may be more involved in other aspects of GI physiology. In future studies, it will be important to further investigate these cell types in additional assays and following loss-of-function manipulations.

We have emphasized in this study the fact that Glp1r+ and Oxtr+ neurons are IGLE mechanoreceptors, but this does not exclude a role for additional, nutrient-specific mechanisms of satiation that act through either these cells or other vagal cell types. Electrophysiological recordings have shown that the vagal neurons activated by gastric and intestinal distension are also activated by CCK (Schwartz et al., 1991, 1995), and our sequencing data show that both Glp1r+ and Oxtr+ IGLE neurons express the Cckar (Figure 5A and S5A). We have also shown that subthreshold levels of CCK can potentiate the inhibition of AgRP neurons by GI distension (Figure S7O–S7R). These synergistic interactions between CCK and GI distension could serve as a mechanism for the integration of GI mechanical and chemical signals.

Central circuits underlying the vagal regulation of food intake

A number of key nodes in the brain that regulate feeding have been identified, but how these nodes encode sensory information, especially signals from the abdominal visceral, remains poorly understood. In this study, we chemogenetically stimulated the four vagal sensory subtypes above and then recorded the response of AgRP neurons in vivo. Stimulation of Oxtr+ intestinal mechanoreceptors rapidly and durably inhibited AgRP neurons in hungry mice, whereas activation other vagal subtypes had lesser (Glp1r+) or no effect (Gpr65+, Vip+). Consistently, AgRP neurons were inhibited by delivery of a volumetric (non-nutritive) load to the intestine, but not to the stomach. This reveals that hypothalamic hunger circuits, which traditionally have been studied in the context of long-term nutritional signals such as leptin, also receive real-time information about the mechanical status of the gut.

The ascending pathway that transmits this information from vagal mechanoreceptors to AgRP neurons is unknown, but likely involves NTS neurons that project to the hypothalamus either directly (Agostino et al., 2016; Roman et al., 2017) or via a relay in the PBN (Rinaman, 2007; Roman et al., 2016). Indeed, we found that stimulation of Oxtr+ intestinal mechanoreceptors activated cells in the NTS and AP as well as their downstream target, the PBN, including two cell types that are known to inhibit food intake: Th+ neurons in the NTS and Calca+ neurons in the PBN. These two cell types are activated by food ingestion, and NTSTh neurons directly project to and stimulate PBNCalca neurons (Rinaman, 2007; Roman et al., 2016). This suggests that Oxtr+ vagal mechanoreceptors inhibit feeding, at least in part, by activating the NTSTh → PBNCalca satiation pathway.

The role of intestinal distension in satiation

Prior work has focused on the role of gastric stretch in regulating feeding, in part because gastric distension can be readily manipulated using a balloon or pyloric cuff (Phillips and Powley, 1996). However we have shown that hyperosmotic solutions can introduce intestinal distension, which may explain earlier findings showing that intraduodenal osmolytes can potently inhibit feeding (Davis and Collins, 1978; Houpt et al., 1983). Despite the lower density of intestinal IGLEs compared to the stomach, the intestine receives similar total IGLE innervation due to its larger surface area (Figure 1J). Perhaps the strongest prior evidence implicating intestinal IGLEs in satiation comes from neurotrophin overexpression or knockout mouse models (Chi and Powley, 2007; Fox, 2006). While interpretation is complicated by potential pleotropic effects, these mutants exhibit selective alterations in intestinal IGLE innervation that correlate with changes in meal patterns in a way that is consistent with our data from optogenetic and chemogenetic manipulations.

A final important question regards when and how intestinal distension is naturally triggered. During normal feeding, the intestinal load is determined by the rate of gastric emptying, which can vary greatly depending on the properties of the food consumed (including liquid versus solid, caloric density, and osmolarity) (Janssen et al., 2011; Kaplan et al., 1992). However one setting in which intestinal distension is exaggerated is following bariatric surgeries, such as Roux-en-Y and vertical sleeve gastrectomy, that reduce food intake. While these procedures are surgically diverse, they share the common property that they result in extraordinarily high rates of gastric emptying (Chambers et al., 2014). This is thought to promote satiety by over-activating intestinal nutrient sensors, thereby causing exaggerated release of gut peptides, but it has been challenging to confirm this model experimentally (Abdeen and le Roux, 2016; Woods et al., 2018). Our data suggest an alternative explanation for this phenomenon: that mechanical distension of the intestine may itself be the signal that triggers the profound reduction in hunger caused by bariatric surgery. The tools described in this paper provide a means to test this and related hypotheses.

STAR★METHODS

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

Further information and requests for reagents and resources should be directed to the Lead Contact, Zachary A. Knight (zachary.knight@ucsf.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Animals were maintained in temperature- and humidity-controlled facilities with 12 hours light-dark cycle and ad libitum access to water and standard chow (PicoLab 5053). All transgenic mice used in these studies were on the C57Bl/6J background, except Uts2bCre mice that were maintained on a mixed FVB/C57Bl/6J background. Mice were at least six weeks old at the time of surgery. All studies employed a mixture of male and female mice and no differences between sexes were observed. All experimental protocols were approved by the University of California, San Francisco IACUC following the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

METHOD DETAILS

Mouse Strains

The Uts2bCre allele was generated by homologous recombination at the endogenous Uts2b locus, aided by targeted CRISPR endonuclease activity. Briefly, a sgRNA (TGTTTCAAGCTCTAAGAAACTG) was selected to introduce CRISPR double strand breaks within the 3’UTR. The targeting vector contained a T2A-Cre cassette inserted immediately upstream of the endogenous stop codon, a 1kb upstream homology arm, and a 2kb downstream homology arm with a TG to GT mutation introduced into the 3’UTR (114–115bp after stop codon) to avoid cleavage by the sgRNA. Super-ovulated female FVB/N mice were mated to FVB/N stud males, and fertilized zygotes were collected from oviducts. Cas9 protein (100 ng/uL), sgRNA (250 ng/uL), and targeting vector DNA (100 ng/mL) were mixed and injected into the pronucleus of fertilized zygotes. 125 injected zygotes were implanted into oviducts of pseudopregnant CD1 female mice. 4 out of 16 pups contained the Cre cassette, with one of these also containing the targeting vector inserted randomly as a transgene. The other three independent founder lines were crossed to reporter mice, and reporter expression patterns from these lines were identical and similar to the ISH result from Allen brain atlas. All Uts2b2A-Cre mice used here were maintained on mixed FVB/C57BL/6J background. Founder pups and offspring were genotyped for the presence of the knock-in allele by qPCR.

Wild-type mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Genotypes and sources of transgenic animals used are listed in the Key Resources Table.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| mouse anti-cFos (1:1000, IHC) | Biosensis | Cat# M-1752–100 |

| Rabbit anti-CGRP (1:1000, IHC) | Immunostar | Cat# 24112; RRID: AB_572217 |

| Chicken anti-GFP (1:1000, IHC) | Aves | Cat# GFP 1020; RRID: AB_10000240 |

| Goat anti-mCherry (1:500, IHC) | Sicgen | Cat# Ab0040–200; RRID: AB_2333092 |

| Rabbit anti-NeuN (1:1000, IHC) | Millipore | Cat# ABN78; RRID: AB_10807945 |

| Rabbit anti-TH (1:1000, IHC) | Millipore | Cat# AB152; RRID: AB_390204 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| AAV9-CAG-DIO-tdTomato-WPRE-bGH | Addgene | Cat# 51503 |

| AAV9-hSyn-DIO-hM3D(Gq)-mCherry | Boston Children Viral Core | N/A |

| AAV9-EF1-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-mCherry-WPRE-hGH | Addgene Viral Core | Cat# 20297 |

| AAV9-CAG-DIO-ChR2(H134R)-mCherry-WPRE-hGH | Boston Children Viral Core | N/A |

| AAV9-CAG-DIO-ChR2(H134R)-mCherry-WPRE-hGH | Janelia Viral Core | N/A |

| AAV8-EF1a-fDIO-GCAMP6m-WPRE-SV40 | Stanford Viral Core | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Cholecystokinin octapeptide (sulfated) ammonium salt (CCK) | Bachem | Cat# 4033010.0001, Lot# 1068721 |

| Clozapine N-oxide (CNO) | Fisher Scientific | Cat# A3317–50 |

| Tamoxifen | Sigma | Cat# T5648–1g |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Nextera DNA Library Prep Kit | Illumina | Cat# FC-121–1031 |

| RNAscope Fluorescent Multiplex Kit | Advanced Cell Diagnostics (ACD) | Cat# 320850 |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Glp1r-C2 | ACD | Cat# 418851-C2 |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Vip-C1 | ACD | Cat# 415961 |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Oxtr-C1 | ACD | Cat# 412171 |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Gpr65-C2 | ACD | Cat# 431431-C2 |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Dbh-C1 | ACD | Cat# 407851 |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Edn3-C1 | ACD | Cat# 505841 |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Uts2b-C1 | ACD | Cat# 468331 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Target-scSeq raw and analyzed data | This paper | GEO: GSE138651 |

| Whole-nodose scSeq raw and analyzed data | This paper | GEO: GSE138651 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: wild-type: C57BL/6J | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX:000664 |

| Mouse: CalcaCreER: Calcatm1.1(cre/ERT2)Ptch | (Song et al., 2012) | MGI: 5460801 |

| Mouse: Glp1rCre: Glp1rtm1.1(cre)Lbrl/RcngJ | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 029283 |

| Mouse: Gpr65Cre: Gpr65tm1.1(cre)Lbrl/RcngJ | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 029282 |

| Mouse: Nav1.8Cre: Scn10atm2(cre)Jnw | (Nassar et al., 2004) | MGI: 3053096 |

| Mouse: NpyFlp: B6.Cg-Npytm1.1(flpo)Hze/J | (Daigle et al., 2018) | JAX:030211 |

| Mouse: Oxtrcre: B6.Cg-Oxtrtm1.1(cre)Hze/J | (Daigle et al., 2018) | JAX: 031303 |

| Mouse: vGlut2Cre: Slc17a6tm2(cre)Lowl/J | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 016963 |

| Mouse: SstCre: B6N.Cg-Ssfm2.1(cre)Zjh/J | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 018973 |

| Mouse: Uts2bCre: Uts2b2A-Cre | This paper | NA |

| Mouse: VipCre: Viptm1(cre)Zjh/J | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 010908 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Uts2b sgRNA sequence: TGTTTCAAGCTCTAAGAAACTG | This paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pAAV-hSyn-DIO-hM3D(Gq)-mCherry | Addgene | Cat. 44361 |

| pAAV-CAG-DIO-ChR2(H134R)-mCherry | Addgene | Cat. 18916 |

| pAAV8-EF1a-fDIO-GCAMP6m-WPRE-SV40 | This paper | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| ArrayStar Version 11.0 | DNASTAR Inc. | N/A |

| ImageJ | NIH | RRID: SCR_003070 |

| MATLAB 2016b | MathWorks | RRID: SCR_001622 |

| PRISM 7.01 | GraphPad | RRID: SCR_002798 |

| RStudio version 3.4.3 | RStudio | RRID:SCR_000432 |

| Seurat 2.0 and 3.0 | Satija Lab | RRID:SCR 007322 |

Target-ScSeq Methods

Nodose ganglion dissociation

Target-ScSeq was developed by Y.L. and M.A.K. and will be described in more detail elsewhere. Briefly, thirty-four 8–12 week old C57BL/6JN mice (18 males and 16 virgin females) were used for the target-scSeq preparation. 7–14 days following WGA555 visceral organ injection, mice were anesthetized under isoflurane and then transcardially perfused with HBSS containing 10 U/mL Heparin. Nodose ganglia were rapidly dissected out within ice-cold HBSS, and chopped into 2–3 pieces, and digested in papain solution (Worthington, LS003119) 10 min at 37°C, followed by collagenase/dispase solution (Worthington, LS004188 and LS02109) for 30 min at 37°C. Tissue was centrifuged at 400 g for 4 min, resuspended in L15 medium (Gibco, 11415), then triturated with a P1000 pipette. The dissociated cell suspension was loaded on top of a Percoll/L15 solution (1:4) (Sigma, P1644–25ML) and centrifuged for 9 min at 400 g. The cell pellet was washed with L15 medium, resuspended in L15 medium, and then kept on ice until use.

Lysis buffer preparation

A similar protocol has been described before (Tabula Muris Consortium T, 2018). Briefly, a 4 uL lysis buffer was aliquoted into PCR tubes and included the following reagents: nuclease free water (Thermo Fisher, AM9937), 1 Unit RiboLock RNase Inhibitor (Thermo Fisher, EO0381), 0.05% Triton X-100 (Sigma, 93443–100ML), 2.5 mM dNTP (Thermo Fisher, R0193), 2.5 uM dT (Integrated DNA Technologies, 5′AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGTACT30VN-3′). The lysis buffer was freshly prepared and kept on ice before cell picking.

Cell picking

The cell suspension was placed on microscope slides (Fisher Scientific, 12-550-15) and examined under the epifluorescence microscope (Nikon, Eclipse Ts2). WGA-555 labeled cells were then individually collected by glass micropipettes (Sutter Instrument, B100-58-10) and transferred to a 2-uL drop of L15 medium to wash and confirm the presence of a single cell. Each cell was then collected again by a glass micropipette and transferred to a separate PCR tube containing 4 uL lysis buffer. The cell picking was done within 1.5 hours after the preparation of cell suspension. The single-cell lysates were kept on ice until the end of cell picking, then frozen at −80°C until processed for cDNA synthesis and library preparation.

cDNA synthesis

cDNA synthesis was performed using the Smart-seq2 protocol. Briefly, PCR tubes containing single-cell lysates were thawed on ice and followed by first-strand synthesis. Primer annealing was carried out by incubating lysates on thermal-cycler at 72°C for 3 min, and hold at 4°C. Immediately after, reverse transcription reaction mix (6 uL) was added to each well. Each 6 uL of reaction mix contained 1 units SMARTScribe Reverse Transcriptase (Takara, 639538), 1.67 U/uL Recombinant RNase Inhibitor (Takara, 2313B), 1.67X First-Strand Buffer (Takara, 639538), 1.67 μM TSO (Exiqon, 5’-AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGTGAATrGrGrG-3’), 8.33 mM dithiothreitol (Thermo Fisher, P2325), 1.67 M Betaine (Sigma, B0300–5VL), and 10 mM MgCl2 (Thermo Fisher, AM9530G). Reverse transcription was carried out by incubating wells on a thermal-cycler at 42°C for 90 min, stopped by heating at 70°C for 5 min, and held at 4°C.

Subsequently, 15 ulL of DNA amplification mix was added to each well. Each amplification mix contained 1.67X KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (Kapa Biosystems, KK2602), 0.17 μM IS PCR primer (IDT, 5’-AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGT-3’), and 0.038 U/uL Lambda Exonuclease (NEB, M0262L). Second-strand synthesis was performed on a thermal-cycler by using the following program: 1) 37°C for 30 min, 2) 95°C for 3 min, 3) 17 cycles of 98°C for 20 s, 67°C for 15 s and 72°C for 4 min, 4) 72°C for 5 min, and 5) held at 4°C.

The DNA amplicon was cleaned up using Ampure XP beads (Beckman-Coulter, A63880). 18 uL Ampure XP beads was added to each amplicon (0.7:1 ratio), mixed by pipetting, incubated at RT for 5 min, and placed on magnetic stand for 3 min. The supernatant was carefully removed. Beads were washed twice with 80 uL of 80% EtOH (freshly prepared), then air-dried for 5 min. Beads with amplicon were then removed from magnetic stand, added with 18 uL TE buffer (Thermo Fisher, AM9849), mixed by pipetting, incubated at RT for 5 min, and placed on magnetic stand for 3 min. The supernatant was carefully moved to the elution plate, and frozen at −20°C until use.

The concentration and quality of cDNA was examined by running 1 uL on a High Sensitivity DNA chip (Agilent, 5067–4627), using Agilent Technology 2100 Bioanalyzer. cDNA with a concentration lower than 50 pg/uL or abnormal peak distribution was not be used. 449 out of 501 samples passed this criterion and were used for sequencing library synthesis.

Sequencing library synthesis

The cDNA was diluted in TE buffer to a final concentration of 200 pg/uL. cDNA samples with a concentration between 50 pg/uL to 200 pg/uL were directly used without any dilution. Sequencing libraries were prepared using Nextera DNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina, FC-121–1031). Briefly, 1.25 uL (diluted) cDNA was mixed with 2.5 uL tagmentation DNA buffer and 1.25 μl Amplification Tagment, Tagmentation reaction was carried out at 55°C for 10 min and then held at 10°C. The reaction was stopped by adding 1. 25 μl Neutralize Tagment Buffer and centrifuging at room temperature at 2,250g for 5 min. Indexing PCR reactions were performed by adding 3.75 uL NPM buffer, 1.25 uL of 5 uM i5 indexing primer, and 1.25 uL of 5μM i7 indexing primer. PCR amplification was carried out on a thermal cycler using the following program: 1) 72°C for 3 min, 2) 95°C for 30 sec, 3) 12 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec, 55°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 60 sec, 4) 72°C for 5 min, and 5) held at 10°C.

Library pooling, quality control and sequencing

After library preparation, wells of each library plate were pooled and purified twice using 0.8x AMPure XP beads (Beckman-Coulter, A63880). Library quality was assessed using a High Sensitivity DNA chip (Agilent, 5067–4627) on an Agilent Technology 2100 Bioanalyzer. Libraries were sequence on the HighSeq 4000 Sequencing System (Illumina) using 2 × 150 bp paired-end reads. Raw and analyzed data deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (accession number GSE138651).

Whole-nodose ScSeq Methods

Generation of nodose ganglion neuron suspension

Seven 6-week-old C57BL/6JN mice (4 males and 3 virgin females) were used to collect nodose ganglion neurons, following the same dissociation protocol described above (for target-scSeq). All nodose ganglia were collected within an hour and were pooled into two eppendorf tubes for digestion. At the end, cells were resuspended in L15 medium and kept on ice prior to sequencing. 10 uL of cell suspension was loaded on a cell counter to estimate the density. Before sequencing, cells were centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min and resuspended in PBS with 0.1% BSA to reach a density of 1000 cell/uL.

Droplet-based scSeq

Single cells were processed through the GemCode Single Cell Platform using the GemCode Gel Bead, Chip and Library Kits (10X Genomics, Pleasanton) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, a nodose neuron suspension (1000 cell/uL in PBS with 0.1% BSA) was loaded. The cells were then partitioned into Gel Beads in Emulsion in the GemCode instrument where cell lysis and barcoded reverse transcription of RNA occurred, followed by amplification, shearing, and 5’ adaptor and sample index attachment. Libraries were sequenced on the Illumina Highseq 4000. Raw and analyzed data deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (accession number GSE138651).

Analysis of Target-scSeq data

Reads alignment

Sequences from the HighSeq 4000 were de-multiplexed to generate a fastq file. Reads were aligned to annotated mRNAs in the mouse genome (UCSC, Mus musculus assembly mm10) and the read count for each gene was calculated using ArrayStar software (DNAstar). Sequence of 449 picked cells were collected and used for further analysis.

Cluster analysis and identification of injured cells

The Seurat (v2) package was used to perform the clustering analysis of the target-scSeq dataset as described (Satija et al., 2015). Gene expression was normalized for each cell by the total expression (global-scaling method), multiplied by a scale factor (10,000) to create TPM-like values (TPM: transcripts per million), and finally computed as ln(TPM+1) to be used for all following data analysis. 5633 variable genes (mean 0.1–10, dispersion > 0.5) were used to compute principle components (PCs). The first 40 PCs were significant based on the jackstraw analysis and were used further for graph-based clustering and tSNE visualization. Cluster specific marker genes were identified by comparing the mean gene expression within the cluster to the median gene expression in all other clusters.

Of note, cells in cluster 1 highly expressed injury induced genes (Figure S2D–S2E). This was likely due to peripheral axonal injury in the tracer-injection surgeries. Consistent with this, most of the injured cells were collected from the stomach or portal vein tracing. Those tracings required injection or manipulation near vagal nerve bundles and were likely to introduce axonal injury.

Cluster analysis without injured cells

To analyze neurons without injury (Figure 2, S2F–S2L), we removed 54 putative injured cells using cutoffs sprr1a < 10 UMI and Ecel1 <10 UMI. Gene expression of the remaining 395 cells was normalized using the method described above and used for further clustering analysis. 3912 variable genes (mean 0.1–10, dispersion > 0.5) were used to compute principle components (PCs). The first 36 PCs were significant based on the jackstraw analysis and were used for graph-based clustering and tSNE visualization (resolution = 3). 395 cells were assigned into 12 cell type clusters.

Average expression of the variable genes for each cluster was determined and used as an input for constructing phylogenetic tree (dendrogram). Cluster specific marker genes were identified by comparing the average gene expression of one cluster to the median gene expression of all other clusters. Pearson’s correlation between cells or clusters was calculated using average expression of the variable genes.

Analysis of whole-nodose scSeq data

Reads alignment

De-multiplexing alignment to the mm10 transcriptome and unique molecular identifier (UMI)-collapsing were performed using Cell Ranger version 2.0.1, available from 10x Genomics with default parameters. A gene-barcode matrix was generated. 1108 cells were captured with 0.3 million mean reads per cell and 7.7 thousand median genes per cell.

Cluster analysis and identification of glial/endothelial cells

The Seurat (v2) package was used to perform the clustering analysis of whole-nodose scSeq dataset as described (Satija et al., 2015). Gene expression of a total of 1108 cells was normalized using the method described above. ln(TPM+1) was calculated and used for the following analysis. 2438 variable genes were used to compute the principle components (PCs). The first 20 PCs were used for graph-based clustering and tSNE visualization (resolution = 0.5). Cluster specific marker genes were identified by comparing the mean gene expression within the cluster to the median gene expression in all other clusters (min.pct = 0.25, thresh.use = 0.25).

Cluster 1 (41 cells) highly expressed marker genes for either satellite glial cells (Apoe, Fabp7, Dbi, and Plp1) or endothelial cells (Emcn, Ecscr, Cdh5, and Igfbp7) and did not express neuronal marker genes (Nefl, Nefm, Snap25, and Tubb3), similar to nodose and jugular ganglion scSeq results described previously (Kupari et al., 2019). All other cells (1067 cells within cluster 2–11) contained neurons which highly expressed Nefl, Nefm, Snap25, and Tubb3. Of note, subsets of neuronal cells also weakly expressed the glial cell marker genes (enriched within cluster 3, 4, 6, 9). This is likely derived from samples containing neurons that are tightly attached to satellite glial cells. Marker genes for cluster 1 (1204 genes) were used to define genes that are enriched in non-neuronal cells and will be used for later analysis.

Analysis of combined scSeq datasets

The Seurat (v3) package was used to perform the data integration and clustering analysis of the combined scSeq datasets as described (Stuart et al., 2019). The target-scSeq dataset and whole-nodose scSeq dataset were filtered and normalized separately, then integrated for clustering analysis (Figure S3). Briefly, 54 putative injured cells were removed from target-scSeq (sprr1a < 10 UMI and Ecel1 <10 UMI), leaving 395 uninjured target-scSeq cells for further analysis. 115 low quality cells (nGene < 6000, percentage of mitochondrial genes > 18%) and 63 non-neuronal cells (endothelial marker Ecscr > 0.5, satellite glial cell marker Apoe > 400) were removed from the whole-nodose scSeq dataset, leaving 956 cells for further analysis.

Of note, samples that contained both neuron and satellite glial cells were included for analysis, since neurons are much larger than satellite cells and contain more reads per cell (Kupari et al., 2019). However, to avoid the contaminated glial cell from biasing the cluster analysis and cell type identification, we removed non-neuronal cell marker genes (1204 genes enriched in the satellite glial cells and endothelial cells, described above) from the variable gene list for clustering analysis. Briefly, 4000 variable genes were identified in each dataset, using the default method of Seurat v3. After removing the non-neuronal marker genes, 3591 and 3520 variable genes were used for the target-scSeq and whole-nodose scSeq dataset, respectively.

Lastly, the filtered target-scSeq and whole-nodose scSeq dataset were integrated (anchor.features = 2000, dims = 1:30). Graph-based clustering was performed using the first 40 PCs and a resolution = 3.5. Cluster specific marker genes were identified by comparing the mean gene expression within the cluster to the median gene expression in all other clusters.

Surgeries

Stereotaxic injection and implantation

Animals were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and placed in a stereotaxic head frame on a heating pad. Ophthalmic ointment was applied to the eyes and subcutaneous injections of meloxicam (5 mg/kg) and sustained-released buprenorphine (1.5 mg/kg) were given to each mouse prior to surgery. The scalp was shaved, scrubbed (betadine and alcohol three times), local anesthetic applied (Bupivacaine 0.25%), and then incised through the midline. A craniotomy was made using a dental drill (0.5 mm). Virus was injected at a rate of 50 nl/min using glass pipette connected with 10 uL Hamilton syringe (WPI, Sarasota, FL), controlled by a micro-injector (Drummond, Nanoject II injector). The needle was kept at the injection site for 3 min before withdrawal. Fiberoptic cannulas were implanted after virus injection in the same surgery, and were secured to the skull using adhesive dental cement (a-m systems 525000 and 526000). At the end of surgery, the skin incision was closed using 5–0 nylon sutures (Henry Schein, 101–7137).

For AgRP neuron photometry (Figure 6–7 and S6–S7), NPYFlp mice were injected with 200 nl of AAV8-fDIO-G6m virus in the Arc (−1.8 mm AP; −0.3 mm ML; −6.0 mm DV relative to the bregma). Photometry cannula (Doric Lenses, MFC_400/430–0.48_6.1mm_MF2.5_FLT) with sleeve (Doric Lenses, SLEEVE_BR_2.5) were implanted unilaterally in the Arc 0.1mm above the virus injection site (−1.8 mm AP; −0.3 mm ML; −5.9 mm DV relative to the bregma). Mice are allowed to recover for a minimum of three weeks before the first photometry experiment.

For vagal afferent optogenetic experiments (Figure 5 and S5), custom-made fiberoptic implants (Thorlabs; 0.39 NA Ø200 mm core FT200UMT and CFLC230–10) were placed unilaterally above the NTS (+ or −0.2mm AP; +1.2mm ML; −4.0mm DV relative to the occipital crest with 20° in the AP direction). Mice are allowed to recover for a minimum of two weeks before optogenetic experiments.

Nodose ganglion injection

Animals were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (100mg/kg ketamine + 10mg/kg xylazine, IP injection). Ophthalmic ointment was applied to the eyes and subcutaneous injections of meloxicam (5 mg/kg) and sustained-released buprenorphine (1.5 mg/kg) were given to each mouse prior to surgery. The skin under neck was shaved and scrubbed (betadine and alcohol three times). A midline incision (~1.5 cm) was made and nodose ganglia were exposed. 200 nl virus containing 0.02 mg/ml Fast Green (Sigma, F7252–5G) was injected at a rate of 100 nl/min using glass pipette. At the end of surgery, the skin incision was closed using 5–0 nylon sutures (Henry Schein, 101–7137).

For histology analysis (Figure 1 and 4), mice were injected with AAV9-DIO-tdTomato and recovered for a minimum of four weeks before perfusion. For chemogenetic experiments (Figure 5 and 6), mice were injected with AAV9-DIO-hM3D-mCherry and were allowed to recover for a minimum of two weeks before behavior tests. For optogenetic experiments (Figure 5), mice were injected with AAV9-DIO-ChR2-mCherry and were allowed to recover for one to two weeks before the stereotaxic optic-implant surgery.

Retrograde tracing from visceral organs

Animals were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (100 mg/kg ketamine + 10 mg/kg xylazine, IP injection). Ophthalmic ointment was applied to the eyes and subcutaneous injections of meloxicam (5 mg/kg) and sustained-released buprenorphine (1.5 mg/kg) were given to each mouse prior to surgery. The abdominal skin was shaved and scrubbed (betadine and alcohol three times). A midline abdominal incision (2 cm) was made along the linea alba running approximately 1 cm caudal from the xiphisternum. Blunt glass probe was used to position the internal organ. A sharp glass needle was used to inject retrograde tracer (Thermo Fisher, WGA555 or WGA647, 5 mg/ml), which was controlled by air pressure applied from a 5 ml syringe. For gastric or intestinal injections, 3 uL tracer was injected at multiple sites into the layer between muscularis externa and serosa layer. For the portal vein injection, 0.5–1 uL tracer was injected to the connective tissue wrapping the portal vein. After injection, the skin incision was closed using 5–0 nylon sutures. 2–14 days following surgery, animals were euthanized and labeled tissue was harvested for histology or sequencing experiments.

Intragastric or intraintestinal catheter implantation

Mice were anesthetized deeply with ketamine/xylazine and surgical sites were shaved and cleaned with betadine and ethanol. Subcutaneous injections of meloxicam (5 mg/kg) and sustained-released buprenorphine (1.5 mg/kg) were given to each mouse prior to surgery. A midline abdominal skin incision was made, extending from the xyphoid process about 1.5 cm caudally, and a secondary incision of 1 cm was made between the scapulae for externalization of the catheter. The skin was separated from the subcutaneous tissue using blunt dissection, such that a subcutaneous tunnel was formed between the two incisions along the left flank to facilitate catheter placement. A small incision was made in the abdominal wall and the catheter (Instech, C30PU-RGA1439) was pulled through the intrascapular skin incision and into the abdominal cavity using a pair of curved hemostats. The stomach was externalized using atraumatic forceps and a purse string stitch was made in the middle of the forestomach using 7–0 non-absorbable Ethilon suture. A puncture was then made in the center of the purse string and the end of the catheter was inserted and secured by the purse string suture. For gastric implant, 2–5 mm of catheter end was fixed within the stomach. While for the intestinal catheter implant, the end of catheter was gently advanced and positioned distal to the pyloric sphincter, and about 2.5 cm of catheter end was fixed within the gastrointestinal tract.

At the end of surgery, the abdominal cavity was irrigated with ~1mL of sterile saline and the stomach was replaced. The abdominal incision was closed in two layers, and the catheter was sutured to the muscle layer at the interscapular site. The interscapular incision was then closed and the external portion of the catheter capped using a 22-gauge PinPort (Instech, PNP3F22). Mice received baytril (5 mg/kg) and warm saline at the end of surgery, and were allowed to recover for 7–10 days prior to behavioral experiments.

Post-surgical care

Post-surgery mice were placed over a heating pad and monitored for their recovery from anesthesia. The health of the mice is monitored daily post-surgery. All mice were given post-surgery analgesia by a subcutaneous injection of meloxicam (5 mg/kg) on post-surgery day 2 and day 3.

Treatments

Intragastric or intraintestinal infusions

All animals were fasted overnight before infusion. All solutions were infused via intragastric catheters using a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, 70–2001). Each infusion was delivered at a rate of 100 ul/min with a total volume of 1 ml. Infusion solutions were prepared accordingly using deionized water: 0.240 g/mL glucose (1.33 M), 0.256 g/mL mannitol (1.33 M), 0.039 g/mL hypertonic salt (0.66 M), 0.009 g/mL saline (0.15 M, 0.9%), and 0.45 g/ml collagen peptide (Sports Research). 20% intralipid (Sigma, I141–100ML) was used without dilution. All solutions were prepared freshly at the beginning of the day.

Oral Gavage

Oral gavage experiments were performed using a 24-gauge reusable feeding tube (FST, 18061–24). All animals were fasted overnight before oral gavage. The tube was introduced through the esophagus to the stomach and 500 uL of various solution was manually infused within 20 to 30 sec. Solutions for oral gavage were prepared the same as those for intragastric infusions, except 1% methylcellulose (Sigma, M0512–100G) prepared using deionized water.

Tamoxifen treatment

Tamoxifen (Sigma, T5648–1g) was dissolved in ethanol (20 mg/ml), mixed with equal volume of sun flower seed oil (Sigma), vortexed for 5–10 min, and centrifuged under vacuum for 20–30 min to remove the ethanol. The solution was kept at −20°C and delivered via intraperitoneal injection treatment. Two weeks after AAV nodose injection, the CalcaCreER mice received 4 mg tamoxifen each day for five days and were euthanized for histology at least four weeks after tamoxifen treatment.

FluoroGold treatment

FluoroGold (Fluorchrome) was injected 20 mg/kg intraperitoneally to either label enteric neurons (Figure 1C and 4F), or to retrogradely label vagal efferent neurons in the DMV (Figure S1C). 3–7 days following surgery, animals were euthanized and labeled tissue was harvested for histology.

Optogenetic stimulation

Construction of the photostimulation system has been previously described (Chen et al., 2016). For RTPP experiments, the laser modulated at 10 Hz with a 10 ms pulse width. For other optogenetic experiments (feeding, drinking, and blood pressure tests), the laser was modulated at 20 Hz for a 2s ON and 3s OFF cycle with a 10 ms pulse width. Laser power was set to 15–18 mW, measured at the tip of each patch cable before each day’s experiments. To prepare mice for optogenetic experiments, AAV9-DIO-ChR2-mCherry was bilaterally injected into the nodose ganglion of the indicated Cre line (experimental group) or Cre− liter mates (control group), and an opto-fiber was implanted over the NTS to activate the central terminals of ChR2+ vagal sensory neurons.

Chemogenetic stimulation

Clozapine N-oxide (CNO) (Fisher Scientific, A3317–50) stock solution was prepared in DMSO as 40 mg/mL. Before experiments, CNO was diluted 1:100 in saline (0.4 mg/mL with 1% DMSO). Mice received an intraperitoneal injection (50 uL for 20 g animal) of either CNO (1 mg/kg) or the control vehicle (saline with 1% DMSO). To prepare mice for chemogenetic experiments, AAV9-DIO-hM3D-mCherry was bilaterally injected into the nodose ganglion of the indicated Cre line (experimental group) or Cre− liter mates (control group)

Behavior Tests

Fiber photometry recording