Synopsis

Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) can be a challenging disease to manage. In recent years, hyperthermia therapy in conjunction with intravesical therapy has been gaining traction as a treatment option. Hyperthermic intravesical chemotherapy is an alternative method of managing NMIBC, especially if BCG might not be available. Trials of intravesical chemotherapy with heat are few and there has been considerable heterogeneity between studies. However, multiple new trials have accrued and high-quality data is on its way. In this review, we discuss the role of combined intravesical hyperthermia and chemotherapy as a novel approach for the treatment of bladder cancer.

Keywords: bladder hyperthermia, heated chemotherapy, heated mitomycin, intravesical chemotherapy, intravesical Mitomycin, HIVEC

INTRODUCTION

Bladder cancer (BC) is the 4th most commonly diagnosed cancer in men and more than 75% are non-muscle invasive (NMIBC) at diagnosis.1,2 NMIBC is generally treated with transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURBT) as a first step. In high-grade tumors, a repeat TURBT is often performed to ensure complete tumor removal and the absence of muscle-invasive cancer.3 Patients determined—based on grade, stage, number of tumors, size of tumors, etc…—to be at intermediate or high risk of recurrence are usually treated with adjuvant intravesical chemotherapy or Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG). BCG-treated patients are generally offered maintenance therapy for 1 year if intermediate risk or 3 years if high-risk.4 Despite these years of active therapy, many (up to half) patients with NMIBC will experience a disease recurrence.5 For those patients who tumors are BCG unresponsive, radical cystectomy is the standard of care salvage treatment but carries a significant morbidity and mortality risk.6 For this reason, most patients faced with the prospect of cystectomy inquire about bladder preserving alternatives and one such alternative is the combination of intravesical chemotherapy with heat.

Hyperthermia as a treatment for NMIBC

The application of mild fever-range heat (40-44°C) to the bladder is called hyperthermia (HT).7 HT is different from thermal ablation where temperatures reach 60-90°C. In general, HT can be used to 1) improve drug delivery to the bladder, 2) kill malignant urothelial cells directly, 3) improve bladder cancer sensitivity to chemotherapy, and 4) trigger anti-cancer immune responses.8-10

1). Drug delivery

When a tumor is heated between 38-42°C, several important vascular physiological effects occur. Local vasodilation occurs and results in increased blood flow to the tumor and adjacent tissue.11 The warmer environment causes the lipid-protein membrane bilayer that contains cells to become more permeable, resulting in easier drug penetration into the cell through the cell membrane. These two mechanisms work synergistically to make an already leaky tumor vasculature even leakier, a phenomenon known as the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect.12 By increasing the EPR effect, HT improves drug delivery to bladder tumors which, in turn, leads to better tumor cell destruction.

2). Cytotoxicity

Since tumors are characterized by a constant state of a relatively inadequate resource supply, their microenvironment develops a hypoxic, acidotic, and energy-deprived character.13 HT to >42°C further alters blood flow to the tumor microenvironment, further depriving the tumor of the oxygen and nutrients that it needs to survive.13 Morphological changes observed when this occurs include an outflow of cytoplasm into the interstitial space, endothelial swelling, changes of the viscosity of blood cell membranes, and micro-thrombosis.11,14 Tumor cells are more sensitive to HT than normal urothelial cells and therefore suffer a lot more during mild heating.

3). Improving sensitivity to therapeutic agents

Multiple antineoplastic agents have been shown to be more efficacious when administered to a heated tumor,11 and the thermal enhancement ratio (TER) quantifies the degree to which heat affects drug efficacy.15 The TER generally compares the ratio of cell kill at 43°C to that at 37°C, with drugs possessing a TER >1 working better with heat. Chemotherapeutic agents used to treat bladder cancer such as cisplatin, mitomycin C (MMC), gemcitabine, and doxorubicin all have a TER of >1.3.16 It is noteworthy that the timing of heating relative to chemotherapy exposure may be important. For example, gemcitabine appears to work better when administered 24 hours after HT.17

4). Anti-cancer immune responses

Temperature is a well-known regulator of immune function.18 Some relevant effects of HT on immunity include changes in number and phenotype of tumor-infiltrating leukocytes, improved tumor-infiltrating leukocyte function, and cytokine release.19 HT also causes heat-shock protein (HSP) release from tumor cells, particularly HSP70 and HSP90, resulting in cross priming of antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes.20 The consequence is that HT-treated tumors actively participate in their own demise by leading to a form of self-vaccination.

Methods of delivering bladder hyperthermia

While there are many ways to categorize devices for hyperthermia, the most obvious category to both the patient and the clinician is how the heat is delivered – external versus internal. External devices use energy emitters to apply heat to a field within the body. They incorporate treatment planning systems to optimize the dose delivered and minimize damage to adjacent tissue, similar to the dose planning used in radiation therapy.

1). External devices

One type of external heating is deep regional radiofrequency, which uses an array of radiofrequency emitters to focus heat into the body. These devices require a medical physics team and a radiofrequency shielded room, which increases cost and decreases generalizability to office-based locations where NMIBC is typically treated. Furthermore, due to the risk of heating implanted metal, external radiofrequency-based heating is generally contraindicated in patients with implanted medical devices (e.g. pacemakers) and hip replacements.21 The BSD 2000 system is an example of an external deep regional radiofrequency device. It uses electromagnetic phased array applicators to deliver deep tissue hyperthermia and allows control of the 3D pattern of therapy specific to the patient’s tumor.22-26 For bladder hyperthermia, the patient has temperature probes placed in the rectum, and bladder to monitor the internal temperature. A water filled applicator is then placed over the lower abdomen/pelvis and water is circulated to cool the skin during therapy. Another example is the AMC device, now sold as the Alba 4D system, which also uses radiofrequency arrayed systems to achieve deep tissue HT.22,27-29 As with the BSD system, it is coupled with a water bolus temperature control apparatus. Other electromagnetic systems include the Thermotron (only available in North Africa and the Middle East) and the Celsius 42 devices. A significant advantage of the Celsius 42 system is that it does not require a shielded room, though it has not been studied in NMIBC.

High intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) is another form of external heating. As the name suggests, HIFU uses the focused soundwaves in an accurate and specific manner to increase the temperature of the tumor without harming adjacent tissue. The commercially available HIFU systems are large devices that externally deliver HIFU. There is a laparoscopic probe that uses a single transducer to image and deliver HIFU to the tumor in a more precise, albeit invasive manner.30

2). Internal devices

Internal devices lack the depth of penetration of external devices but have the significant advantage of delivering heat almost exclusively to the bladder. There are 2 systems that use conductive hyperthermia the Combat Bladder Recirculating system (BRS) and Unithermia.31,32 Both devices externally heat fluid and the circulate it to the bladder via a 3-way irrigating Foley catheter. The recirculating fluid contains a chemotherapy agent chosen by the treating physician. Recirculating systems are the smallest, most portable, and least expensive bladder heaters. Synergo produces a third intravesical bladder heating system that also uses recirculating bladder irrigation but instead of a heat exchanger it employs a microwave radiofrequency emitting intravesical catheter to heat the bladder.33-35 The Synergo device is presently the most well studied device amongst those mentioned, though several large trials of the Combat BRS device have accrued and will report results soon.

There are two additional devices worth mentioning, electromotive drug administration (EMDA) and nanoparticles. Although in the strict sense, these are not hyperthermia devices, they do share a similar therapeutic mechanism. EMDA uses a urethral catheter to deliver ionized drugs intravesically. Dispersive pads (similar to electrocautery) are placed on the lower abdomen and an electric current is applied intravesically to drive the drug into the urothelium at a rate proportional to the amount of current being applied. EMDA allows for greater depth of penetration than would be achievable by passive diffusion alone.36 Nanoparticles can be administered intravenously or intravesically and they preferentially accumulate in tumors secondary to the enhanced permeability and retention effect.37 Externally delivered light or alternating magnetic fields generates heat in the tissue hosting the nanoparticles.

Clinical experience with bladder hyperthermia

The combination of heat and intravesical chemotherapy has been utilized both in the neoadjuvant (pre-TURBT) and adjuvant settings (post-TURBT). For this review we use HIVEC as the acronym for hyperthermic intravesical chemotherapy. The large majority of HIVEC treatments done thus far have utilized MMC as the chemotherapy agent.

Phase 1 & 2 trials

To date, there are 5 clinical trials of neoadjuvant chemo ablative HIVEC for NMIBC and all used MMC. In these trials, 60-100% of patients had previously undergone some form of intravesical therapy (Table 1). The complete response rate of patients who underwent HIVEC ranged from 53% - 75% with a partial response rate of 20% - 47%. The recurrence rate ranged from 13% - 39% at a median follow up of 15 - 39 months.34,38-41

Table 1:

Phase 1 & 2 trials and observational studies on neoadjuvant intravesical chemothermia therapy

| Author & year |

Study design |

Sample size |

Treatment | Heat Source |

Induction Schedule |

Maintenance schedule for CR group |

% of patients with previous intravesical treatment |

f/u | CR | PR | NR | Recurren ce Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colombo 199539 | Phase 1 | 44 | 30mg MMC in 60ml water for 40 minutes | Synergo (42.5-44.5°C) | Twice-weekly within 6 weeks (Total of 8 sessions) | - | 63.6% | 24 months (mean) | 70.4 | 20.4 | 9.1 | 15.9% |

| Gofrit 200434 | Phase 1 | 28 | (40mg MMC dissolved in 50ml of distilled water for 20 minutes) ×2 | Synergo (42 ± 2°C) | Once-weekly ×8 | Once-monthly ×4 | 60.1% | 15.2 months | 75% | - | - | 19% |

| Sousa 201438 | Phase 1 | 15 | 80mg MMC dissolved in 50ml of distilled water for 60 minutes | Combat BRS (42 ±1°C) | Once-weekly × 8 | Partial responder treated once-weekly ×4, then once-monthly ×11. CR did not received maintenance | 74% | 29 months | 53% | 47% | 0% | 13.3% |

| Colombo 199640 | Phase 2 | 29 | (40mg MMC in 50 ml distilled water for 30 minutes) ×2 | Synergo (42.5-46°C for 60 minutes) | Once/twice-weekly × 6-8 | - | 100% | 38 months | 66% | 34% | 0% | 27% |

| 23 | 40mg MMC in 50 ml sterile water for 60 minutes | - | Once/twice-weekly × 6-8 | - | 100% | 36 months | 22% | 26% | 52% | 39% | ||

| Colombo 200163 | Phase 2 | 36 | 40mg MMC in 50 ml of saline for 60 minutes | - | Once-weekly ×4 | - | - | - | 27.7% | - | - | - |

| 29 | 40mg MMC diluted in 50ml of distilled water for 60 minutes | Synergo (mean of 42.5°C) | Once-weekly ×4 | - | - | - | 66% | - | - | - | ||

| 15 | 40mg MMC dissolved in 150ml of distilled water & EMDA for 20 minutes | Physionizer 30 | Once-weekly ×4 | - | - | - | 40% | - | - | - | ||

| Rigatti 199135 | Observational | 12 | 30mg MMC dissolved in 60ml of distilled water for 60 minutes | SB-TS 100 (41.5-43.5°C) | Once/twice-weekly × 6-8 | - | - | 16 months | 41.7% | 33.3% | 25% | 8.3% |

| Moskovitz 200549 | Observational | 10 | (40mg MMC dissolved in 50ml of distilled water for 30 minutes) ×2 | Synergo (42 ± 2°C) | Once-weekly × 8 | Once-monthly ×4 | 80% | 5.6 months (mean) | 80% | - | - | - |

| Witjes 200963 | Observational | 26 (100% CIS) | (40mg MMC dissolved in 50ml of distilled water for 30 minutes) ×2 | Synergo (41-44 °C for 60 minutes) | Once-weekly ×6 | Once every 6 weeks ×6 (total of 6 sessions) | 66.7% | 22 months | 92% | - | - | 22% |

| Moskovitz 201251 | Observational | 26 | (40mg MMC dissolved in 50ml of distilled water for 30 minutes) ×2 | Synergo (approximately 42°C) | Once-weekly ×8 | Once every 6 weeks for 1st year (20mg MMC) | 76.9% | 9 months | 79% | 8% | 13% | 16% |

| Volpe 201252 | Observational | 14 | (40mg MMC dissolved in 50ml of distilled water for 30 minutes) ×2 | Synergo (42 ± 2°C) | Once-weekly ×8 | Once-monthly ×6 | 100% | 14 months (mean) | 42.9% | 9.9% | 47.2% | 46.3% |

| Sousa 201631 | Observational | 24 | 80mg MMC dissolved in 50ml of distilled water for 60 minutes | Combat (43 ± 0.5 °C) | Once-weekly ×8 | Once-monthly × 6 | 33% | 37 months | 62.5% | 33.3% | 4.2% | 31.3% |

Dose in the maintenance group is similar to treatment unless stated otherwise. HT: hyperthermia therapy; MMC: Mitomycin C; EMDA: Electromotive drug administration; CR: Complete response

The first trial of MMC HIVEC was conducted by Colombo et al. in 1995, where 44 patients underwent neoadjuvant administration of intravesical chemotherapy and simultaneous local bladder hyperthermia for eight 60-minute sessions done twice weekly, followed by TURBT 3 weeks later.39 The complete response rate was 70%, partial response was 20% and no response in 9% of patients. After a mean follow-up of 24 months, 16% recurred.39 In 2004, Gofrit et al. treated 52 patients with high-grade NMIBC with MMC HIVEC.34 Of these, 28 men were treated with neoadjuvant HIVEC (MMC 80 mg) and 24 men adjuvant HIVEC (MMC 40 mg). More than 50% of both groups have been previously treated with BCG. Recurrence-free survival was 71% at a median follow up of 15 months. Surprisingly, in the neoadjuvant cohort, 75% of patients achieved complete response to therapy.34 Subsequently, there were 2 randomized trials conducted by Colombo et al. where neoadjuvant HIVEC (MMC 40 mg) was compared to standard MMC, or to EMDA (MMC 40 mg) and standard MMC. 40,41 HIVEC achieved a complete response in 66% of patients in both studies, compared to 22% for standard MMC and 40% for EMDA.40,41

There are 3 phase 1 & 2 adjuvant trials reporting recurrence-free survival. In these 3 trials, the patient cohort consisted of intermediate and high-grade NMIBC. The 1 and 2-year recurrence-free survival ranges from 67% to 87% and 50% to 91%, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2:

Phase 1, 2 & 3 trials and observational studies on adjuvant intravesical chemothermia therapy.

| Author & Year published |

Trial | Sample size |

Treatment per session |

Heat Source |

Induction schedule |

Maintenance schedule for CR group |

Risk Group (% patients) |

Hx of intravesical therapy (% patients) |

Follow up, Median (IQR) |

1-year RFS |

2-year RFS |

5-year RFS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gofrit 200434 | Phase 1 | 24 | (20mg MMC in 50ml of distilled water for 20 minutes) ×2 | Synergo (42 ± 2°C) | Once-weekly × 8 | Once-monthly × 4 | High grade (100%) | 87.5% | 35.3 months (mean) | 66.5% | 60.6% | 52.1% |

| Soria 201642 | Phase 1 & 2 | 34 | (40mg MMC in 50ml saline for 22 minutes) ×2 | Unithermia (42.5 ± 1°C) | Once-weekly × 6 | Once-monthly × 4 | High grade (53%) Low grade (47%) |

100% | 41 (−) | 85.4% | 73.5% | 55.2% |

| vanderHeijden 200443 | Phase 2 | 90 | (20mg MMC in 50ml of distilled water for 30/60 minutes) ×2/1 | Synergo (41 – 44°C) | Once-weekly × 6-8 | Once-monthly × 4-6 | High risk (41%) Intermediate risk (59%) |

66.1% | 18 (4-24) | 86.7% | 75.4% | - |

| Colombo et al 200344 | Phase 3 | 42 | (20mg MMC in 50ml of distilled water for 30 minutes) ×2 | Synergo (42 ± 2°C) | Once-weekly × 8 | Once-monthly × 4 | High grade (90.5%) | - | 24 months (−) | 88.7% | 82.8% | 61.7% |

| 41 | 20mg MMC in 50ml of distilled water for 60 minutes | - | Once-weekly × 8 | Once-monthly × 4 | High grade (97.6%) | - | 50.3% | 38.4% | 21.3% | |||

| Arends 201645 | Phase 3 | 92 | (20mg MMC in 50ml of distilled water for 30 minutes) ×2 | Synergo (42 ± 2°C) | Once-weekly × 6 | Once every 6 weeks for the 1st year | High grade (81.6%) Low grade (18.4%) |

52% | 24 months (−) | 90.5% | 80.2% | - |

| 98 | BCG (Oncotice) full dose for 120 minutes | - | Once-weekly × 6 | Three weekly doses at 3, 6 & 12 months | Intermediate risk (67.4%) High risk (32.6%) |

75.8% | 66.5% | - | ||||

| Tan 201946 | Phase 3 | 48 | (20mg MMC in 50ml of distilled water for 30 minutes) × 2 | Synergo (42 ± 2°C) | Once-weekly ×6 | Once every 6 weeks for the 1st year, once every 8 weeks for the 2nd year | High grade (100%) | 100% | 36 months (23.1-44.5) | 49.8% | 35% | - |

| 56 | BCG or standard of care at institution | - | Once-weekly × 6 | Three weekly instillations at 3, 6, 12, 18 & 24 months | High grade (100%) | 100% | 56.7% | 42.1% | - | |||

| Moskovitz 200549 | Observational | 22 | (20mg MMC dissolved in 50ml of distilled water for 30 minutes) ×2 | Synergo (42 ± 2°C) | Once-weekly × 6-8 | Once-monthly × 4-6 | High grade (68.2%) Low grade (31.8%) |

63.5% | 9.6 months (mean) | 100% | 70% | - |

| Nativ 200953 | Observational | 111 | (20mg MMC in 50ml solution for 30 minutes) ×2 | Synergo (42 ± 2°C) | Once-weekly × 6 | Once every 4-6 weeks ×6 | High grade (61%) Low grade (39%) |

100% | 16 months (range 2-74) | 85% | 56% | - |

| Halachmi 201154 | Observational | 56 | (20mg MMC for 30 minutes) ×2 | Synergo (42 ± 2°C) | Once-weekly × 6 | Once every 4-6 weeks × 6 | High grade (100%) | 54% | 18 months (range 2-49) | 77% | 42.9% | - |

| Moskovitz 201251 | Observational | 66 | (20mg MMC in 50ml solution for 30 minutes) ×2 | Synergo (approximately 42°C) | Once-weekly × 6 | Once every 6 weeks for 1st year | High grade (45.5%) Low grade (51.5%) Not reported (1.5%) |

74.2% | 23 months (range 3-84) | 86.5% | 67.2% | - |

| Volpe 201252 | Observational | 16 | (20mg MMC dissolved in 50ml of distilled water for 30 minutes) ×2 | Synergo (42 ± 2°C) | Once-weekly × 6 | Once-monthly × 6 | High grade (100%) | 100% | 14 months (mean) | 87.5% | 58.6% | - |

| Maffezzini 201455 | Observational | 42 | 40mg MMC dissolved in 50ml of distilled water for 60 minutes | Synergo (42.5 ± 1.5°C) | Once-weekly × 4 | Once every 2 weeks ×6, then once-monthly ×4 | High grade (100%) | 64.3% | 38 months (range 4-73) | 88.1% | 80.2% | 63.5% |

| Ekin 2015 (APJCP)56 | Observational | 43 | 40mg MMC dissolved in 50ml of distilled water for 60 minutes | UniThermia (42.5-45°C) | Once-weekly ×6 | Three weekly instillations at month 3 & 6 | High grade (58.1%) Low grade (41.9%) |

- | 30 months (range 9-39) | 82% | 61% | - |

| Ekin 2015 (CJU)57 | Observational | 40 | 40mg MMC in 50 ml saline solution for 60 minutes | UniThermia (42.5-45°C) | Once-weekly ×6 | Three-weekly instillations at month 3 & 6 | High grade (60%) Low grade (40%) |

- | 33 months (24-39) | 92.2% | 73.6% | - |

| Sooriakumaran 201659 | Observational | 97 | 40mg MMC dissolved in 50ml of normal saline for 60 minutes | Synergo (41 - 44°C) | Once-weekly × 6-8 | Once every 6 weeks for the 1st year, one every 8 weeks for the 2nd year (20mg MMC) | High grade (100%) | 90.7% | 27 months (16-47) | 82.7% | 66.0% | 48.6% |

| Sousa 201642 | Observational | 16 | 40mg MMC dissolved in 50ml of distilled water for 60 minutes | Combat (43 ± 0.5°C) | Once-weekly × 4 | No | High risk (71%) Intermediate risk (29%) |

81.3% | 24 months | 100% | 88.1% | - |

Dose in the maintenance group is similar to treatment unless stated otherwise. HT: hyperthermia therapy; MMC: Mitomycin C; BCG: Bacillus Calmette-Guerin; RFS: Recurrence Free Survival; Hx: History; CR: Complete Response

Soria et al. utilized the Unithermia device which delivers heat via conducting heating. In this study, 34 patients with recurrent, intermediate risk NMIBC underwent a 6-week course of HIVEC (MMC 40 mg) for 45 min. The 1, 2 and 5-year RFS were 85%, 74% and 55% respectively.42 The other 2 trials utilized the Synergo system in high and intermediate risk NMIBC. Patients in both studies received two 30-minute sessions of HIVEC (MMC 20 mg) for 6-8 cycles. The 1 and 2-year RFS ranged from 67-87% and 61%-75%.34,43

Phase 3

To date, there are no phase 3 trials utilizing neoadjuvant HIVEC for NMIBC but there are 3 adjuvant HIVEC trials. In 2003, Colombo et al. randomized 83 patients (>50% with high risk NMIBC) to HIVEC versus standard MMC. In both arms, patients received 20 mg/50 mL of MMC foe two 30-minutes sessions for 6 weeks. The 2-year RFS and 5-year RFS were 83% vs 38% and 62% vs 21% for HIVEC and standard MMC, respectively. The hazard ratio for HIVEC was 0.21.44

Arends et al. subsequently reported a phase 3 randomized controlled trial where 190 patients with intermediate and high risk NMIBC were randomized HIVEC or BCG. Patients in the BCG arm received induction OncoTICE BCG (induction + maintenance at 3, 6 and 12 months). HIVEC patients received MMC (20mg/50mL) for two 30-minute sessions for 6 weeks, and maintenance course (3 cycles) at 3, 6 and 12 months. The 2-year RFS was better for HIVEC (82%) than BCG (65%).45

More recently, in the HYMN trial 104 patients with BCG unresponsive NMIBC were randomized to HIVEC (MMC 20 mg/50mL) vs standard MMC. Patients received induction followed by three once-weekly maintenance instillations at 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24months. There was no statistical difference in RFS between the arms at 2 years (HR 1.33; 95% CI 0.84-2.10, p=0.23).46 At a median follow up of 35 months, the rate of disease progression was 8%.

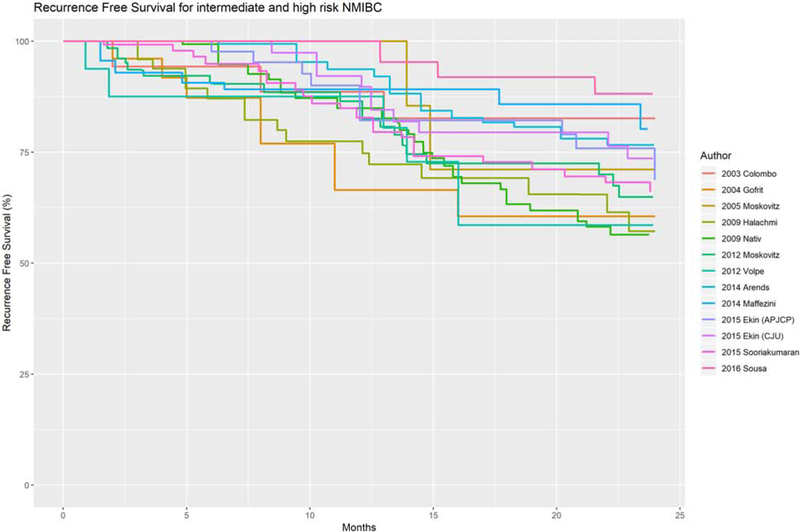

In addition to the trials noted above, there are 6 observational studies of neoadjuvant HIVEC and 10 of adjuvant HIVEC and these are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.31,35,47-59 Recurrence-free survival curves from the various studies utilizing the Synergo, Combat BRS and Unithermia devices are pooled and shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Combined Kaplan Meier Graph of recurrence free survival for all studies on chemothermia therapy.

Clinical experience with EMDA

The combination of MMC and EMDA has been utilized both in the neoadjuvant (pre-TURBT) and adjuvant settings (post-TURBT). Intravesical EMDA MMC is administered using a controlled electric current of up to 30 mA using a battery-powered generator. A specialized 16 Fr catheter is inserted and urine drained. MMC is then instilled with an operating current of 15-20 mA pulsed electrical current for 20 to 30 minutes per session. To date, 2 small clinical trials have utilized EMDA in the neoadjuvant setting (Table 3) and 4 studies have used EMDA in the adjuvant setting (Table 4). EMDA was found to have a complete response rate of 40% in the neoadjuvant setting. 41,60 In the adjuvant setting, EMDA was found to have a 1-year RFS, 2-year RFS and 5-year RFS rate of 86-100%, 49-80%, 38-40% respectively.61-64 One study evaluated TURBT, TURBT with immediate postoperative MMC and neoadjuvant MMC with EMDA followed by TURBT. Patients with intermediate-risk and high-risk disease in all three groups were then placed on maintenance MMC and BCG, respectively. The group that received neoadjuvant MMC with EMDA followed by TURBT had the highest 5-year RFS of 62% compared to 37% in the TURBT only arm.65

Table 3:

Adverse events from phase 1, 2 & 3 trials and observational studies on intravesical chemothermia.

| Author | Year | Study Type | N | Energy | Complete treatment (%) |

Grade ≥ 3 adverse events (%) |

Hematuria (%) |

UTI or sepsis (%) |

Stricture (%) |

Allergic reaction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colombo | 1995 | Phase 1 | 44 | RITE | - | - | - | - | 2 | 2 |

| Gofrit | 2004 | Phase 1 | 52 | RITE | 96 | - | 2 | 10 | 2 | 10 |

| Sousa | 2014 | Phase 1 | 15 | Conduction | - | 0 | 20 | 13 | 0 | 7 |

| Soria | 2016 | Phase 1/2 | 34 | Conduction | 88 | 12 | - | 4 | - | - |

| Colombo | 1996 | Phase 2 | 29 | RITE | 93 | - | - | - | 0 | - |

| Colombo | 2001 | Phase 2 | 29 | RITE | 100 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| vanderHeijden | 2004 | Phase 2 | 90 | RITE | 100 | - | 9 | 0 | 4 | 9 |

| Colombo | 2003 | Phase 3 | 42 | RITE | 69 | - | 7 | 0 | 7 | 12 |

| Arends | 2016 | Phase 3 | 184 | RITE | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Tan | 2018 | Phase 3 | 48 | RITE | 90 | 10 | 48 | 23 | 6 | 15 |

| Moskovitz | 2005 | Observational | 47 | RITE | - | 4 | 17 | 0 | 6 | 4 |

| Nativ | 2009 | Observational | 111 | RITE | 95 | 8 | 19 | 2 | 5 | 8 |

| Witjes | 2009 | Observational | 26 | RITE | 92 | - | 3% | - | - | - |

| Halachmi | 2009 | Observational | 56 | RITE | 91 | - | 4 | 0 | 2 | 12.5 |

| Moskovitz | 2012 | Observational | 92 | RITE | 96 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Volpe | 2012 | Observational | 30 | RITE | 100 | - | 27 | 7 | 0 | 13 |

| Maffezzini | 2014 | Observational | 42 | RITE | 88 | 0 | 62 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ekin (APJCP) | 2015 | Observational | 43 | Conductive | 93 | 12 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Ekin (CJU) | 2015 | Observational | 40 | Conductive | 95 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sooriakumaran | 2015 | Observational | 97 | RITE | 93 | 7 | 14 | 23 | 0 | 0 |

| Kiss | 2015 | Observational | 21 | RITE | 62 | 52 | 24 | 0 | 10 | 10 |

| Sousa | 2016 | Observational | 40 | Conductive | 98 | 8 | 23 | 23 | 3 | 3 |

RITE: Radiofrequency-Induced Thermo-chemotherapeutic Effect; UTI: Urinary Tract Infection

Table 4:

Clinical trials and observational studies on adjuvant intravesical MMC and EMDA.

| Author & Year published |

Trial | Sample size |

Treatment per session |

EMDA device/curr ent |

Induction schedule |

Maintenance schedule for CR group |

Risk Group (% patients) |

Hx of intravesical therapy (% patients) |

Follow up, Median (IQR) |

1-year RFS |

2-year RFS |

5-year RFS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DiStasi 200361 | Phase 3 | 36 | 40mg MMC in 100ml of distilled water for 60 minutes & EMDA | 20mA for 30 minutes | Once-weekly ×6 | Non-responders: 2nd induction course Responders: Once-monthly ×10 |

High grade (100%) | - | 43 months | 100% | 66% | 38% |

| 36 | 40mg MMC in 100ml of distilled water for 60 minutes | - | Once-weekly ×6 | Non-responders: 2nd induction course Responders: Once-monthly ×10 |

High grade (100%) | - | 100% | 62% | 34% | |||

| 36 | 81mg BCG in 50ml saline for 120 minutes | - | Once-weekly ×6 | Non-responders: 2nd induction course Responders: Once-monthly ×10 |

High grade (100%) | - | 100% | 39% | 21% | |||

| DiStasi 200662 | Phase 3 | 105 | 81mg BCG for 120 minutes | - | Once-weekly ×6 | Once-monthly × 10 | High grade (100%) | 41% | 88 months (63-110) | 73% | 77% | 56% |

| 107 | (Week 1 & 2: 81mg BCG for 120 minutes Week 3: 40mg MMC in 100ml of distilled water & EMDA) ×3 | 20mA for 30 minutes | 3 cycles (9 weeks total) | Month 1, 2, 4, 5, 7 & 8: MMC + EMDA Month 3, 6 & 9: BCG | High grade (100%) | 42% | 100% | 49% | 40% | |||

| DiStasi 201165 | Phase 3 | 124 | TURBT | - | Once | Low-risk: none Intermediate risk: 40mg MMC dissolved in 50ml of sterile water for 60 minutes weekly ×6 High risk: 81mg BCG dissolved in 50ml of saline for 120 minutes weekly ×6 |

High grade (82%) | No previous intravesical treatment | 92 months (61-126) | 62% | 42% | 37% |

| 126 | TURBT + immediate postoperative 40mg MMC in 50ml water for 60 minutes | Once | High grade (81%) | 82 months (50-125) | 65% | 47% | 43% | |||||

| 124 | Neoadjuvant 40mg MMC in 100ml water for 30 minutes & EMDA +TURBT | 20mA for 30 minutes | Once | High grade (82%) | 85 months (57-126) | 87% | 70% | 62% | ||||

| Riedl 199863 | Observational | 22 | 40mg MMC in 100ml saline | 15mA for 20 minutes | Once-weekly × 4 | - | High grade (95%) | - | 7.3 months (mean) | - | - | - |

| Gan 201664 | Observational | 22 | (Week 1 & 2: BCG Week 3: 40mg MMC & EMDA) ×3 | Physionizer ® 30: 20mA for 30 minutes | 3 cycles (9 weeks total) | (Once-weekly BCG) ×3 on month 3 and every 6 months for 3 years | High grade (100%) | - | 24 months | 86% | 80% | - |

Dose in the maintenance group is similar to treatment unless stated otherwise. MMC: Mitomycin C; BCG: Bacillus Calmette-Guerin; RFS: Recurrence Free Survival; Hx: History; CR: Complete Response

Safety

The first bladder hyperthermia treatment was attempted in 1972 where Thio-Tepa was used in conjunction with HT up to 44°C for low stage bladde r tumors.66 Since then, multiple adverse events that include hematuria, UTI, sepsis, stricture, allergic reaction to chemotherapy agent, dysuria, frequency, urgency and incontinence have been reported (Table 3). There was insufficient data to pool for grade 3 or higher adverse events, UTI, sepsis and allergic reaction. The rate of grade 3 or higher adverse event rate ranges from 10-12% across all sources of energy in patients receiving HT in clinical trials published.31,67 UTI and sepsis occurred in 0-23% of patients, and strictures in 0-10%.67 Allergic reaction occurred in 0-15% of patients.67 Pooling data for randomized controlled trials showed that the relative risk of hematuria in the HT arm is 1.28 (95% CI 0.89-1.83, I2=0).

Future perspective & other novel agents

For intermediate risk NMIBC, HIVEC-I (EudraCT 2013-002628-18) and HIVEC-II (ISRCTN 23639415) are multi-institutional randomized controlled trials comparing HIVEC with standard MMC in patients with intermediate-risk NMIBC. Both trials have completed accrual (N = 598 subjects combined). HIVEC-HR (EudraCT 2016-001186-85) is assessing HIVEC in high-risk NMIBC and HIVEC-R (EudraCT 2014-005001-20) is assessing HIVEC as neoadjuvant chemoablation. All of these trials are using the Combat BRS device. Lastly, the RITE-USA trial () is assessing HT with the Synergo device for BCG-unresponsive NMIBC.

A novel temperature-sensitive liposome drug delivery system is worth highlighting here. The first drug, called ThermoDox and developed at Duke, is loaded with doxorubicin and is administered systemically to releases free drug when it arrives in tissues heated to ≥41°C. When combined with bladder HT, this technology allows for organ-specific targeting of systemic agents. In a swine model, Thermodox is able to achieve doxorubicin levels far exceeding free doxorubicin while minimizing toxicity in other organs.68

CONCLUSIONS

Intravesical chemotherapy and hyperthermia therapy is safe and able to augment the efficacy of intravesical chemotherapy for the treatment of BCG refractory NMIBC, especially in a time of BCG shortage. Further prospective randomized controlled trials combining other forms of chemotherapy with hyperthermia therapy is warranted to determine if improved efficacy is obtained in those drugs. Other combinations of therapy such as combining hyperthermia and intravesical chemotherapy therapies such as PD-1/PD-L1 blockade is warranted.

Key points.

Heat can improve drug delivery, increase cancer cell sensitivity to therapeutic agents, and trigger anti-cancer immune responses.

Three methods of bladder heating are available clinically: external deep regional radiofrequency heating, intravesical catheter radiofrequency heating, and recirculating conductive heating.

Administering intravesical chemotherapy with heat is safe and appears to improve treatment efficacy.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures:

Dr Tan is supported by the Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA Institutional Research Training Grant (T32-CA009111).

Dr. Inman has received clinical trial or research support from the following entities within the past 12 months: Abbott Laboratories, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Urogen, Anchiano Therapeutics, Nucleix, Taris Biomedical, Combat Medical, FKD Therapies, Dendreon, and Genentech. He has consulted for ColdGenesys.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians; 2018;68(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soloway MS. It is time to abandon the "superficial" in bladder cancer. European urology. 2007;52(6):1564–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Bladder Cancer (Version 1.2019). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/bladder.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2019.

- 4.Lamm DL, Blumenstein BA, Crissman JD, et al. Maintenance bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy for recurrent TA, T1 and carcinoma in situ transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a randomized Southwest Oncology Group Study. The Journal of urology. 2000;163(4): 1124–1129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cambier S, Sylvester RJ, Collette L, et al. EORTC Nomograms and Risk Groups for Predicting Recurrence, Progression, and Disease-specific and Overall Survival in Non-Muscle-invasive Stage Ta-T1 Urothelial Bladder Cancer Patients Treated with 1-3 Years of Maintenance Bacillus Calmette-Guerin. European urology. 2016;69(1):60–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamat AM, Sylvester RJ, Bohle A, et al. Definitions, End Points, and Clinical Trial Designs for Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: Recommendations From the International Bladder Cancer Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(16):1935–1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falk MH, Issels RD. Hyperthermia in oncology. International journal of hyperthermia : the official journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology, North American Hyperthermia Group. 2001;17(1): 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frey B, Weiss EM, Rubner Y, et al. Old and new facts about hyperthermia-induced modulations of the immune system. International journal of hyperthermia : the official journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology, North American Hyperthermia Group. 2012;28(6):528–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hildebrandt B, Wust P, Ahlers O, et al. The cellular and molecular basis of hyperthermia. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2002;43(1):33–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wust P, Hildebrandt B, Sreenivasa G, et al. Hyperthermia in combined treatment of cancer. The Lancet Oncology. 2002;3(8):487–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Issels RD. Hyperthermia adds to chemotherapy. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2008;44(17):2546–2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maeda H, Tsukigawa K, Fang J. A Retrospective 30 Years After Discovery of the Enhanced Permeability and Retention Effect of Solid Tumors: Next-Generation Chemotherapeutics and Photodynamic Therapy--Problems, Solutions, and Prospects. Microcirculation (New York, NY : 1994). 2016;23(3):173–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaupel P, Kallinowski F, Okunieff P. Blood flow, oxygen and nutrient supply, and metabolic microenvironment of human tumors: a review. Cancer research. 1989;49(23):6449–6465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song CW. Effect of local hyperthermia on blood flow and microenvironment: a review. Cancer research. 1984;44(10 Supplement):4721s–4730s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson JE, Wizenberg MJ, McCready WA. Radiation and hyperthermal response of normal tissue in situ. Radiology. 1974;113(1):195–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takemoto M, Kuroda M, Urano M, et al. The effect of various chemotherapeutic agents given with mild hyperthermia on different types of tumours. International journal of hyperthermia : the official journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology, North American Hyperthermia Group. 2003;19(2):193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vertrees RA, Das GC, Popov VL, et al. Synergistic interaction of hyperthermia and Gemcitabine in lung cancer. Cancer biology & therapy. 2005;4(10):1144–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang HG, Mehta K, Cohen P, Guha C. Hyperthermia on immune regulation: a temperature's story. Cancer letters. 2008;271(2):191–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans SS, Repasky EA, Fisher DT. Fever and the thermal regulation of immunity: the immune system feels the heat. Nature reviews Immunology. 2015;15(6):335–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milani V, Noessner E, Ghose S, et al. Heat shock protein 70: role in antigen presentation and immune stimulation. International journal of hyperthermia : the official journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology, North American Hyperthermia Group. 2002;18(6):563–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Longo TA, Gopalakrishna A, Tsivian M, et al. A systematic review of regional hyperthermia therapy in bladder cancer. International journal of hyperthermia : the official journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology, North American Hyperthermia Group. 2016;32(4):381–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Zee J, Gonzalez Gonzalez D, van Rhoon GC, van Dijk JD, van Putten WL, Hart AA. Comparison of radiotherapy alone with radiotherapy plus hyperthermia in locally advanced pelvic tumours: a prospective, randomised, multicentre trial. Dutch Deep Hyperthermia Group. Lancet (London, England). 2000;355(9210):1119–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wittlinger M, Rodel CM, Weiss C, et al. Quadrimodal treatment of high-risk T1 and T2 bladder cancer: transurethral tumor resection followed by concurrent radiochemotherapy and regional deep hyperthermia. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2009;93(2):358–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inman BA, Stauffer PR, Craciunescu OA, Maccarini PF, Dewhirst MW, Vujaskovic Z. A pilot clinical trial of intravesical mitomycin-C and external deep pelvic hyperthermia for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. International journal of hyperthermia : the official journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology, North American Hyperthermia Group. 2014;30(3):171–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrovich Z, Emami B, Kapp D, et al. Regional hyperthermia in patients with recurrent genitourinary cancer. American journal of clinical oncology. 1991;14(6):472–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sapozink MD, Gibbs FA Jr., Egger MJ, Stewart JR. Regional hyperthermia for clinically advanced deep-seated pelvic malignancy. American journal of clinical oncology. 1986;9(2):162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crezee J, Van Haaren PM, Westendorp H, et al. Improving locoregional hyperthermia delivery using the 3-D controlled AMC-8 phased array hyperthermia system: a preclinical study. International journal of hyperthermia : the official journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology, North American Hyperthermia Group. 2009;25(7):581–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geijsen ED, de Reijke TM, Koning CC, et al. Combining Mitomycin C and Regional 70 MHz Hyperthermia in Patients with Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: A Pilot Study. The Journal of urology. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rietbroek RC, Bakker PJ, Schilthuis MS, et al. Feasibility, toxicity, and preliminary results of weekly loco-regional hyperthermia and cisplatin in patients with previously irradiated recurrent cervical carcinoma or locally advanced bladder cancer. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 1996;34(4):887–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Castro Abreu AL, Ukimura O, Shoji S, et al. Robotic transmural ablation of bladder tumors using high-intensity focused ultrasound: Experimental study. International journal of urology : official journal of the Japanese Urological Association. 2016;23(6):501–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sousa A, Pineiro I, Rodriguez S, et al. Recirculant hyperthermic IntraVEsical chemotherapy (HIVEC) in intermediate-high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. International journal of hyperthermia : the official journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology, North American Hyperthermia Group. 2016;32(4):374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soria F, Milla P, Fiorito C, et al. Efficacy and safety of a new device for intravesical thermochemotherapy in non-grade 3 BCG recurrent NMIBC: a phase I-II study. World journal of urology. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colombo R, Salonia A, Leib Z, Pavone-Macaluso M, Engelstein D. Long-term outcomes of a randomized controlled trial comparing thermochemotherapy with mitomycin-C alone as adjuvant treatment for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). BJU international. 2011;107(6):912–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gofrit ON, Shapiro A, Pode D, et al. Combined local bladder hyperthermia and intravesical chemotherapy for the treatment of high-grade superficial bladder cancer. Urology. 2004;63(3):466–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rigatti P, Lev A, Colombo R. Combined intravesical chemotherapy with mitomycin C and local bladder microwave-induced hyperthermia as a preoperative therapy for superficial bladder tumors. A preliminary clinical study. European urology. 1991;20(3):204–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jung JH, Gudeloglu A, Kiziloz H, et al. Intravesical electromotive drug administration for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017;9:Cd011864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oliveira TR, Stauffer PR, Lee CT, et al. Magnetic fluid hyperthermia for bladder cancer: a preclinical dosimetry study. International journal of hyperthermia : the official journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology, North American Hyperthermia Group. 2013;29(8):835–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sousa A, Inman BA, Pineiro I, et al. A clinical trial of neoadjuvant hyperthermic intravesical chemotherapy (HIVEC) for treating intermediate and high-risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. International journal of hyperthermia : the official journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology, North American Hyperthermia Group. 2014;30(3):166–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colombo R, Lev A, Da Pozzo LF, Freschi M, Gallus G, Rigatti P. A new approach using local combined microwave hyperthermia and chemotherapy in superficial transitional bladder carcinoma treatment. The Journal of urology. 1995;153(3 Pt 2):959–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Colombo R, Da Pozzo LF, Lev A, Freschi M, Gallus G, Rigatti P. Neoadjuvant combined microwave induced local hyperthermia and topical chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for superficial bladder cancer. The Journal of urology. 1996;155(4):1227–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colombo R, Colombo R, Brausi M, et al. Thermo–Chemotherapy and Electromotive Drug Administration of Mitomycin C in Superficial Bladder Cancer Eradication. European urology. 2001;39(1):95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soria F, Milla P, Fiorito C, et al. Efficacy and safety of a new device for intravesical thermochemotherapy in non-grade 3 BCG recurrent NMIBC: a phase I-II study. World journal of urology. 2016;34(2):189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Heijden AG, Kiemeney LA, Gofrit ON, et al. Preliminary European results of local microwave hyperthermia and chemotherapy treatment in intermediate or high risk superficial transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. European urology. 2004;46(1):65–71; discussion 71-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colombo R, Da Pozzo LF, Salonia A, et al. Multicentric study comparing intravesical chemotherapy alone and with local microwave hyperthermia for prophylaxis of recurrence of superficial transitional cell carcinoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(23):4270–4276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.TJ Arends, Nativ O, Maffezzini M, et al. Results of a Randomised Controlled Trial Comparing Intravesical Chemohyperthermia with Mitomycin C Versus Bacillus Calmette-Guerin for Adjuvant Treatment of Patients with Intermediate- and High-risk Non-Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer. European urology. 2016;69(6):1046–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan WS, Panchal A, Buckley L, et al. Radiofrequency-induced Thermochemotherapy Effect Versus a Second Course of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin or Institutional Standard in Patients with Recurrence of Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer Following Induction or Maintenance Bacillus Calmette-Guerin Therapy (HYMN): A Phase III, Open-label, Randomised Controlled Trial. European urology. 2019;75(1):63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arends TJ, van der Heijden AG, Witjes JA. Combined chemohyperthermia: 10-year single center experience in 160 patients with nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. The Journal of urology. 2014;192(3):708–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kiss B, Schneider S, Thalmann GN, Roth B. Is thermochemotherapy with the Synergo system a viable treatment option in patients with recurrent non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer? International journal of urology : official journal of the Japanese Urological Association. 2015;22(2):158–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moskovitz B, Meyer G, Kravtzov A, et al. Thermo-chemotherapy for intermediate or high-risk recurrent superficial bladder cancer patients. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2005;16(4):585–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alfred Witjes J, Hendricksen K, Gofrit O, Risi O, Nativ O. Intravesical hyperthermia and mitomycin-C for carcinoma in situ of the urinary bladder: experience of the European Synergo working party. World journal of urology. 2009;27(3):319–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moskovitz B, Halachmi S, Moskovitz M, Nativ O, Nativ O. 10-year single-center experience of combined intravesical chemohyperthermia for nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. Future oncology (London, England). 2012;8(8):1041–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Volpe A, Racioppi M, Bongiovanni L, et al. Thermochemotherapy for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: is there a chance to avoid early cystectomy? Urologia internationalis. 2012;89(3):311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nativ O, Witjes JA, Hendricksen K, et al. Combined thermo-chemotherapy for recurrent bladder cancer after bacillus Calmette-Guerin. The Journal of urology. 2009;182(4):1313–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Halachmi S, Moskovitz B, Maffezzini M, et al. Intravesical mitomycin C combined with hyperthermia for patients with T1G3 transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Urologic oncology. 2011;29(3):259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maffezzini M, Campodonico F, Canepa G, Manuputty EE, Tamagno S, Puntoni M. Intravesical mitomycin C combined with local microwave hyperthermia in nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer with increased European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) score risk of recurrence and progression. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2014;73(5):925–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ekin RG, Akarken I, Cakmak O, et al. Results of Intravesical ChemoHyperthermia in High-risk Non-muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention : APJCP. 2015;16(8):3241–3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ekin RG, Akarken I, Zorlu F, et al. Intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin versus chemohyperthermia for high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Canadian Urological Association journal = Journal de l'Association des urologues du Canada. 2015;9(5-6):E278–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Geijsen ED, de Reijke TM, Koning CC, et al. Combining Mitomycin C and Regional 70 MHz Hyperthermia in Patients with Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: A Pilot Study. The Journal of urology. 2015;194(5):1202–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sooriakumaran P, Chiocchia V, Dutton S, et al. Predictive Factors for Time to Progression after Hyperthermic Mitomycin C Treatment for High-Risk Non-Muscle Invasive Urothelial Carcinoma of the Bladder: An Observational Cohort Study of 97 Patients. Urologia internationalis. 2016;96(1):83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brausi M, Campo B, Pizzocaro G, et al. Intravesical electromotive administration of drugs for treatment of superficial bladder cancer: a comparative Phase II study. Urology. 1998;51(3):506–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Di Stasi SM, Giannantoni A, Stephen RL, et al. Intravesical electromotive mitomycin C versus passive transport mitomycin C for high risk superficial bladder cancer: a prospective randomized study. The Journal of urology. 2003;170(3):777–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Di Stasi SM, Giannantoni A, Giurioli A, et al. Sequential BCG and electromotive mitomycin versus BCG alone for high-risk superficial bladder cancer: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2006;7(1):43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Riedl CR, Knoll M, Plas E, Pfluger H. Intravesical electromotive drug administration technique: preliminary results and side effects. The Journal of urology. 1998;159(6):1851–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gan C, Amery S, Chatterton K, Khan MS, Thomas K, O'Brien T. Sequential bacillus Calmette-Guerin/Electromotive Drug Administration of Mitomycin C as the Standard Intravesical Regimen in High Risk Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: 2-Year Outcomes. The Journal of urology. 2016;195(6):1697–1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Di Stasi SM, Valenti M, Verri C, et al. Electromotive instillation of mitomycin immediately before transurethral resection for patients with primary urothelial non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2011;12(9):871–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lunglmayr G, Czech K, Zekert F, Kellner G. Bladder hyperthermia in the treatment of vesical papillomatosis. International urology and nephrology. 1973;5(1):75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tan WS, Kelly JD. Intravesical device-assisted therapies for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Nature reviews Urology. 2018;15(11):667–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brousell SC, Longo TA, Fantony JJ, et al. MP65-08 HEAT-TARGETED DRUG DELIVERY USING THE COMBAT BRS DEVICE FOR TREATING BLADDER CANCER. The Journal of urology. 2017;197(4, Supplement):e855. [Google Scholar]