Abstract

Post-translational modifications are the apex of cellular communication and eventually regulate every aspect of life. The identification of new post-translational modifiers is opening alternative avenues in the understanding of fundamental cell biology processes and ultimately novel therapeutic opportunities. The ubiquitin-fold modifier 1 (UFM1) is a post-translational modifier discovered a decade ago but its biological significance remained mostly unknown. The field recently witnessed an explosion of research uncovering the implications of the pathway cellular homeostasis in living organisms. Here, we overview recent advances in the function and regulation of the UFM1 pathway, and its implications to cell physiology and disease.

Keywords: UBL, UFM1, ER stress, UPR, proteostasis

The Ufm1 conjugation system

Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like molecules (UBLs) constitute the third most common post-translational modification after phosphorylation and glycosylation. This family of small proteins can be covalently attached to their targets following an E1-E2-E3 reaction (See Box 1), altering either their stability, structure or interactome [1]. While the ubiquitin ‘code’ has been extensively studied over the course of decades [1], the functions of many other UBLs are still poorly understood. One such modifier is the ubiquitin-fold modifier 1 (UFM1) [2]. UFM1 and its conjugating machinery are highly conserved among most eukaryotes except in yeasts or other fungi. Interestingly, UFM1 substrates appear to have been insulated from other UBLs, as they share a high percentage of exclusivity for ufmylation [3]. The UFM1 system is also tightly related to the function of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the expression of most components of the UFM1 pathway are modulated by ER stress. Considering that ER stress is a hallmark of many pathologies [4,5], recent studies pointed to the UFM1 system as a contributor to tissue homeostasis and a possible key player in the progression of different diseases such as cancer, heart failure, gut inflammation and neurodevelopmental diseases. In the next sections, we overview different regulatory aspects of the UFM1 system, followed by a discussion of the emerging physiological functions of the pathway and its possible implication to human diseases.

Box 1. Ubl conjugation enzymatic reaction.

The ubiquitin and many other Ubls (non-exhaustive : Sumo, Nedd8, Ufm1, ISG15) are conjugated to their target substrates following and E1-E2-E3 reaction (Figure I). The activating enzyme (E1) initiates the cascade in the following steps:

1a. Adenylation of the Ubl carboxy-terminal to create a covalent linkage acyl-phosphate by conversion of ATP to AMP.

1b. Attack of the E1 catalytic cysteine onto the acyl-phosphate to form a thioester with the Ubl carboxy-terminal, releasing AMP.

2. The conjugating enzyme (E2) receive this thioester bound Ubl onto their own catalytic cysteine through trans-thioesterification.

3. The ligase enzyme (E3) recruits both the target substrate and the charged E2 to bring them in proximity and catalyzes a covalent isopeptide bond between a receptor lysine of the substrate and the Ubl. E3s are classified into two major branches: RING (for “really interesting new gene”) family, acting purely as scaffold proteins and HECT (E6AP carboxyl terminus domain) family, bearing their own catalytic cysteine to assist an intermediary reaction. However, there are many exceptions to this dichotomy, some E3 being neither RING and HECT or both [1].

Figure I.

Text Box 1. Ubl conjugation enzymatic reaction.

Core components of the UFM1 system

The dynamic E1-E2-E3 cascade reaction is entirely conserved in the UFM1 conjugation system (see Figure 1). While the ubiquitination reaction encompasses around 50 different E2s and more than 600 E3s, only one of each enzyme have been identified for the ufmylation reaction so far. Interestingly, the late discovery of the UFM1 pathway might be explained by the low percentage of sequence homology with others UBLs and the atypical nature of its components [2]. The first step of ufmylation relies on the maturation of the UFM1 precursor (proUFM1) by UFM1-specific cysteine proteases (UFSP1 and UFSP2) [6–8], cleaving the C-terminal dipeptide Ser-Cys to expose a single glycine residue which differs from the usual diglycine C-terminus of others UBLs [2,6]. UFM1 itself consists of a small 85 amino acid globular protein with a low sequence identity to ubiquitin (around 15%) but a conserved tertiary structure including a β-grasp fold similar to ubiquitin [2]. Both UFSPs are highly specific for UFM1 but UFSP1 is not expressed in plants and nematodes [6], and predicted to be inactive in humans because of a blunted catalytic N-terminal domain [9,10]. The UFSPs also act as ‘deufmylation’ enzymes [6]. Notably, UFSP2 expression keeps ufmylation in check since its knock down strongly increases UFM1 conjugates [10].

Figure 1. The UFM1 conjugation pathway.

The zymogen pro-UFM1 is processed by the protease UFSP2 in the C-terminal, which exposes a glycine residue and yield the mature UFM1 group. UBA5 activates UFM1 through an adenylation reaction that consume ATP. UFC1, the E2 conjugating enzyme, retrieves UFM1 from UBA5 by forming a transthioester bond with UFM1. Next, UFL1 recruits an ufmylation substrate and the charged UFC1. This complex is anchored at the cytosolic side of the ER, UFL1 spanning the membrane and UFBP1 displaying a short transmembrane tail domain. CDK5RAP3 (CDK5R3 on the Figure) acts as a stabilizer for the complex at the ER. Both UFBP1 and CDK5RAP3 are qualified as possible adaptor proteins, allowing the ligase UFL1 to recruit a wider pool of substrates. Eventually, the substrates become mono- or poly-ufmylated and released from the complex. UFSP2 also operates as a major deufmylation enzyme of the pathway, removing UFM1 molecules from their targets.

After maturation, UFM1 is activated by the E1 of the pathway, namely the ubiquitin activating enzyme 5 (UBA5) [2]. Contrary to other E1, UBA5 displays both its adenylation activity and catalytic cysteine (Cys250) on a single domain rather than two separate flexible domains [11]. UFM1 activation by UBA5 also differs from other UBLs, with the formation of a pre-covalent complex followed by the adenylation and thioester bond formation of the UFM1 conjugate [12–15]. Then, UBA5 transfers the activated UFM1 onto the predicted catalytic cysteine of the E2 UFM1-conjugase 1 (UFC1) [16]. Besides a partially conserved catalytic core domain, UFC1 does not have a strong homology with other known E2s [2,17]. While most of the components if the UFM1 pathway are mainly located at the cytosolic side of the ER membrane, UBA5 and UFC1 display a cytosolic and also nuclear distribution [2,18].

The final step of ufmylation depends on the E3 UFM1-ligase 1 (UFL1 also termed Maxer, NLBP or RCAD) [19]. This unconventional transmembranenous E3 lacks a catalytic cysteine [19]. For this reason, UFL1 is classified as a scaffold-like E3, similar to a RING type of E3, bringing its substrate and E2 in close proximity. We propose that, similar to other scaffold-type of E3, UFL1 is able to interact with adaptor proteins to increase or change the amount of available substrates of the pathway [19,20].

Satellite components of the UFM1 system

The UFM1-binding protein 1 (UFBP1, also known as C20orf116, Dashurin or DDRGK1) was first identified as a substrate for ufmylation but quickly emerged as a component of the pathway operating as a key interactor and possible adaptor of UFL1 [19,21]. UFBP1 is a highly-conserved protein containing both a transmembrane signal peptide and a nuclear localization signal (NLS) [19,22,23], in addition to a proteasome-COP9-initiation domain (PCI) necessary for the formation of multimeric complexes [22,24]. The loss of UFBP1 abolishes the ufmylation of known substrates and prevents the docking of the UFM1 multi-complex at the ER [19,21,25]. The ufmylation of UFBP1 itself is not necessary for the complex assembly but appears to alter the ufmylation of other substrates [9]. Many functions have been described for UFBP1, ranging from maintaining ER homeostasis to regulating membrane expansion, cell cycle control and cell differentiation [21,23,26,27]. However, it is still unclear whether any of these functions involve ufmylation.

The second known putative adaptor protein for UFL1 is the CDK5 regulatory subunit-associated protein 3 (CDK5RAP3 also known as C53 or LZAP). CDK5RAP3 was initially described as a regulator of cell cycle, DNA damage response and classified as a tumor suppressor [28,29]. CDK5RAP3 interacts with UFL1, increasing its own protein stability and can relocate to the ER with the ufmylation complex [20,25]. CDK5RAP3 function as an adaptor for the ufmylation pathway is reflected by changes for UFM1 immunoreactivity in hepatocytes and HEK293T cell type null for CDK5RAP3 ([30] and unpublished observations from C. Hetz laboratory). In addition, recent evidence suggests that CDK5RAP3 could be a necessary component for poly-ufmylation [25].

Importantly, while the core components of the UFM1 pathway have been well characterized, only a small pool of its possible substrates have been identified. In addition, some components of the pathway (such as UFBP1 [30]) may have functions that are independent of the ufmylation activity, making more difficult to dissect the physiological role of the UFM1 pathway in the cell. In this review, we will discuss the major functions of the UFM1 pathway, drawing the reader’s attention to any specific ufmylated substrates which have been identified as the basis for said functions.

Ufmylation role in tissue homeostasis and cellular differentiation

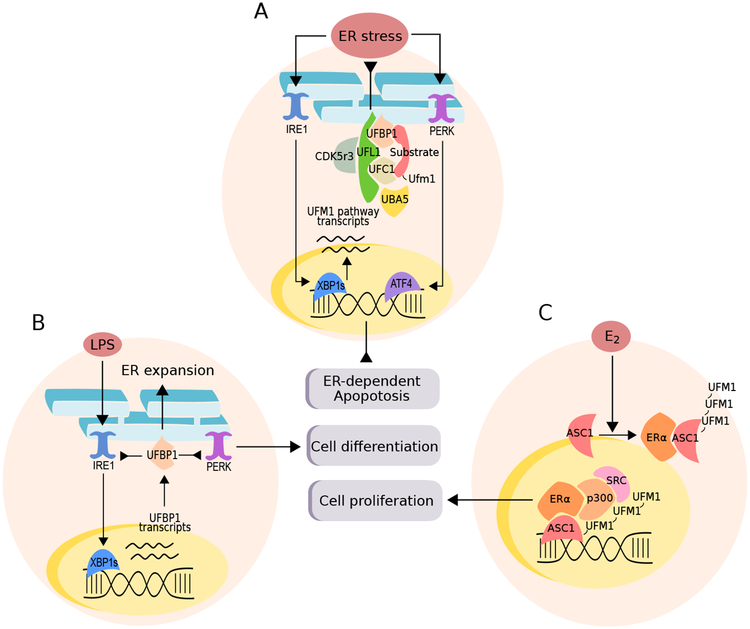

The ufmylation pathway is crucial for the life of multi-cellular organisms and is key to sustain cell development and tissue homeostasis. In fact, the genetic deletion of UBA5, UFL1, UFBP1 and CDK5RAP3 in mice and zebrafish results in embryonic lethality [21,31–34]. Conditional genetic ablation of these major ufmylation components led to apoptosis in many cell types, including hematopoietic stem cells (HSC), liver cells, and cells with high secretory activity (i.e Paneth cells or pancreatic acini) and was consistently associated with the upregulation of ER stress markers [21,23,31,33,35,36]. The homeostasis of the ER is surveyed by a set of stress sensors that coordinates the establishment of an adaptive response (the unfolded protein response or UPR, see Box 2), which may switch its signaling toward an apoptosis program under chronic or irreversible stress. The increased activity of the UPR (a measure of ER stress) observed in mice impaired for ufmylation included the activation of the UPR sensor Inositol requiring enzyme-1 (IRE1) and PKR-like ER protein kinase-1 (PERK), concomitantly to the activation of their downstream effectors X-box binding protein-1 (XBP1) and phosphorylated eIF2α [37]. In addition, many pro-apoptotic transcripts related to chronic ER-stress such as Chop, Bax, Puma, Noxa and DR5 are increased in cells deficient for UFL1 or UFBP1 [21,33]. Finally, the UPR directly controls ufmylation pathway under ER stress at the transcriptional level, through a mechanism depending on the IRE1-XBP1 axis [26,35] (Figure 2A). While the pro-apoptotic activation of the UPR components can explain most of the cell death observed in mice with genetic deletion of ufmylation components, the UFM1 pathway also regulates programs for cell differentiation, independently of apoptosis. Below, we describe several of these programs regulated by the ufmylation pathway.

Box 2. Three axes of the unfolded protein response (UPR).

The UPR is mediated by a set of three sensors located at the ER membrane. Alterations in ER proteostasis translates into the accumulation of misfolded proteins. ER stress is transmitted through discrete but interconnected UPR signaling cascades initiated by the sensors PERK, IRE1 and ATF6, resulting in the activation of transcriptional programs and control of protein translation. ER stress can arise from many sources such as calcium imbalance, protein misfolding and aggregation, oxidative damage, defects in protein glycosylation or mitochondrial failure. The intensity and duration of the stress will determine if cells undergo an adaptive response or engage apoptosis. UPR stress sensors are activated by the release of an inhibitory interaction with the ER chaperone BiP or through the direct binding of misfolded proteins in the case of PERK and IRE1 (see Figure I). IRE1 is a type-1 ER protein containing kinase and RNase domains at the cytosolic region. Upon activation, IRE1 homodimerizes and autophosphorylates, catalyzes the unconventional splicing of the XBP1 mRNA by removing a short intron carrying a stop codon. The spliced form of XBP1 (XBP1s) is a highly active transcription factor controlling the transcription of chaperones, quality control gene, amongst other targets. Under ER stress, ATF6 relocates to the Golgi compartment after dissociation from BiP. The sequential cleavage of ATF6 by the proteases S1P and S2P allows the release of a cytosolic transcription factor that regulates the expression of UPR target genes. ATF6 and XBP1s might heterodimerize to increase their transcriptional activity. PERK can act as a blocker of protein translation by phosphorylating the α subunit of the eIF2α complex. The mRNA of the transcription factor ATF4 bears alternative open reading frames increasing its translation under eIF2α blockade. ATF4 regulates the expression of genes involved in folding, redox control, amino acid metabolism, autophagy and apoptosis. ATF4 controls the expression of CHOP and BCL-2 family members, mediators of apoptosis under ER stress.

Figure I.

Text Box 2. The unfolded protein response.

Figure 2, Key Figure. The interplay between the UFM1 pathway, ER stress and cell fate.

The ufmylation pathway can control different physiological processes depending on the stimuli and cellular background. A. The UFM1 pathway is canonically associated with the ER stress response (UPR, See Box 2 for details) and its expression is controlled by the major transcription factor XBP1s. The genetic deletion of the pathway engages ER-dependent apoptosis in many different background and its expression helps to cope with pharmacologically induced ER stress. B. Plasma B-Cell differentiation is activated by exposure to LPS, which induces a transcriptional increase in UFM1 pathway interactor UFBP1 through XBP1s expression. UFBP1 represses the activation of the sensors IRE1 and PERK as a feedback response and promotes ER expansion, allowing immunoglobulin production. C. In breast cancer cell lines, exposure to estradiol (E2) promotes the interaction of the nuclear receptor ERα to ASC1 and subsequent poly-ufmylation. ASC1 ufmylation forms a scaffold to recruit p300 and SRC and activate cell proliferation. ASC1 is also a critical regulator of hematopoietic stem cells differentiation, and genetic deletion of ufmylation components is correlated with pancytopenia in a genetic mouse model. Overall, the ufmylation pathway appears to regulate cell fate either by reducing or preventing ER stress, or through transcriptional programs.

Hematopoietic system

One of the main causative factors for embryonic lethality in UBA5, UFL1, and UFBP1 knockout mice is the impairment of both primitive and definitive erythropoiesis in fetal livers, resulting in severe anemia [21,31,33]. Knockout embryos display liver hypoplasia and exhibit reduced numbers of erythrocytes with increased amounts of multi-nucleated erythrocytes that underwent apoptosis [21,32,33]. Inducible deletion of UFL1 and UFBP1 in adult mice also led to severe anemia, confirming the role of ufmylation in adult hematopoiesis [21,33]. Interestingly, the deficiency of ufmylation components affected both hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) and erythroid lineage-specific progenitor cells, indicating a broad involvement of the ufmylation pathway in the hematopoietic system [21,32,33]. The occurrence of ER stress and cell death in HSC observed in mice with genetically defective ufmylation has been correlated to pancytopenia, but other factors may also come into play. Notably, in addition to elevated ER stress levels, the ablation of UFBP1 expression was shown to impact HSC differentiation programs through the activating signal co-integrator 1 (ASC1) [21], a known target for poly-ufmylation after stimulation with estradiol in breast cancer cell lines [9]. ASC1 is a crucial transcriptional coactivator of the ERα nuclear receptor, and regulates genes involved in erythrocytes development [21]. The suppression of ASC1 produced a similar impairment of HSC differentiation but without signs of ER stress, suggesting two separate levels of regulation (Figure 2).

Plasma cell development

Another example of how the ufmylation pathway regulates the development of certain cell types lies in plasma cell activation. The deletion of the gene encoding for UFBP1 gene in B lymphocytes decreased the total amount of plasma cells and reduced the serum levels of immunoglobulins isotypes [26]. In vitro, UFBP1 deficiency impairs lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced development of plasmablasts and mature plasma cells. Mechanistically, UFBP1 represses the activation of the UPR sensor PERK through an IRE1-dependent regulation, preventing plasma cells activation [26] (Figure 2). Indeed, the PERK branch of the UPR is known to be specifically repressed by LPS, and its inactivation may constitute a critical step in B-cell differentiation [38,39]. In addition, IRE1 protein levels and the activation of its main downstream target XBP1 were increased after ablating UFBP1 expression [26]. These effects might be mediated by a direct interaction between UFBP1 and IRE1 [40], yet there are discrepancies between in vivo and in vitro studies regarding IRE1 levels in cells with a UFBP1 deficient background [26,36,37]. The deletion of UFBP1 in plasma cells did not engage a pro-apoptotic activation of the UPR, since comparable levels of survival rate were observed between UFBP1 wild-type and deficient cells [26]. This observation supports the idea that components of the ufmylation pathway can control cell differentiation independent of apoptotic mechanisms.

Cdk5rap3 in embryogenesis and liver development

CDK5RAP3 is an adaptor protein for the ufmylation pathway, possibly mediated by a direct interaction with UFL1 [20,29,41]. Morpholino-mediated knockdown of CDK5RAP3 in zebrafish led to embryonic lethality at an extremely early stage as zebrafish failed to initiate epiboly [34], the first coordinated cell movement process during development. Targeting CDK5RAP3 in zebrafish also resulted in increased apoptosis and cell arrest at the G2/M phase of the cell cycle [34]. Additionally, loss of CDK5RAP3 in zebrafish embryos inhibited the activity of glycogen synthase 3 (GSK3) that is necessary for β-catenin degradation [42]. This event resulted in the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin and subsequent activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling, which disrupted the normal dorsal-ventral development [42]. In mice, the ablation of CDK5RAP3 expression also led to embryonic lethality, yet discrepancies on the stage of embryonic death have been reported [31,34]. One study observed that CDK5RAP3 knockout embryos die around E16.5, while another study reported that death occurred at a much earlier time (before E6.5) [34] (also unpublished observation from the Li Lab). However, the mechanisms explaining these survival differences are still not defined. Conditional deficiency of CDK5RAP3 expression in hepatocytes led to post-weaning lethality caused by severe hypoglycemia and impaired lipid metabolism [31].

The ufmylation pathway in diseases

The use of conditional knockout mice in pre-clinical models have demonstrated the potential protective role of the UFM1 conjugation system in the context of multiple pathological conditions. In the intestine, Paneth cells secrete antimicrobial peptides to maintain intestinal homeostasis and disruption of Paneth cell function contributes to the advancement of inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Ufmylation genes are highly expressed in these exocrine cells, and specific deletion of UFL1 or UFBP1 in intestinal epithelial cells led to significant loss of both Paneth and goblet cells in the gut [36,43]. At the cellular and molecular levels, UFBP1 deficiency causes ER stress and the induction of cell death programs in intestinal epithelial cells [36]. Administration of the chemical chaperone tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA, inhibitor of ER stress) partially prevented the loss of Paneth cells caused by acute UFBP1 deletion, suggesting a causative role of ER proteostasis impairment in the reported phenotype [36]. Finally, UFBP1 deficient animals are highly susceptible to experimentally-induced colitis, suggesting that aberrant ufmylation may contribute to inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis [36].

The UFM1 cascade also plays a protective role in cardiac muscle cells by preventing cardiomyopathy [44]. Cardiac-specific UFL1 knockout mice develop age-dependent cardiomyopathy and heart failure as indicated by elevated expression of cardiac fetal genes, increased fibrosis, and impaired cardiac contractility [44]. When challenged with pressure overload, UFL1-deficient hearts exhibited greater hypertrophy, exacerbated fibrosis, and a worse cardiac contractility compared with control counterparts [44]. Again, UFL1 deficiency led to elevated ER stress, and administration of TUDCA alleviated ER stress and attenuated pressure overload-induced cardiac dysfunction in UFL1 deficient mice [44].

In the pancreas, the UFM1 conjugation system appears to be crucial for both exocrine and endocrine cells. The overexpression of different components of the ufmylation pathway protects pancreatic beta cells from ER stress-induced cell death [23]. UFL1 and UFBP1 were considerably upregulated in the pancreas of alcohol preferring mice compared to non-alcohol preferring mice, and the combination of alcohol consumption and UFL1 depletion resulted in increased caspase 3 and trypsin activation in acinar cells [43]. A potential involvement of the UFM1 system was also reported in other disease models, including type 2 diabetes [45], ischemic heart injury [46], atherosclerosis [47], and steatohepatitis [48,49] (summarized in Table 1).

Table 1.

Role of ufmylation in pre-clinical models of disease.

| Disease | Gene Analyzed | Pre-clinical Model | Phenotype | Possible Mechanism | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) | Ufbp1 | DSS-induced colitis mouse model | Deletion of Ufbp1 in intestine enhanced and accelerated development of colitis. | When ufmylation is downregulated, ER stress is activated which increases inflammatory cytokines. | 36 |

| Cardiomyopathy and Heart failure | Ufl1 | TAC mice (pressure overload-induced hypertrophy) | Deletion of Ufl1 in cardiomyocytes caused age dependent cardiomyopathy and enhanced disease development in TAC mice. | Ufmylation protects against ER stress which leads to impaired heart function. | 44 |

| Ischemic heart Injury | Ufm1 | MPC-1 mice (Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 cardiac specific knock-in mice) | Ufm1 was upregulated in hearts of MPC-1 mice. | Activation of ER stress leads to upregulated ufmylation in attempt to return to ER homeostasis | 46 |

| Atherosclerosis | Ufm1 | ApoE −/− mice (apolipoprotein E knockout mice) | Ufm1 was upregulated in the hearts of ApoE −/− mice. | Ufm1 help to regulate lipid metabolism in macrophages | 47 |

| Alcoholism/Pancreatitis | Ufl1 | Alcohol preferring rats/ alcohol induced pancreatitis | Ufl1 was upregulated in the pancreases of alcohol preferring rats. | Activation of UPR leads to upregulated ufmylation in attempt to restore ER homeostasis | 48,49 |

| Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) | Ufm1 | MKR transgenic mice | Ufm1 was upregulated in pancreatic islets of MKR mice. | Activation of ERAD and UPR, upregulation of ufmylation, which may lead to defective insulin secretion | 45 |

In addition to these pre-clinical studies, genetic screenings in different human populations identified gene variants of the UFM1 pathway in neurodevelopmental diseases, including infantile encephalopathy, microencephaly and ataxia [50–52], hip dysplasia [53,54] and carcinomas [55]. UBA5 and UFM1 variants from patients with early-onset encephalopathy were cloned and characterized as hypomorphic, resulting in severe loss of ufmylation activity [50,51]. A second study found similar loss-of-function phenotypes for UFC1 and UFM1 in different human population [56]. A polymorphism of the UFM1 promoter also abolished its activation specifically in neuronal cell lines and was associated with similar encephalopathy [57].

Familial dominant mutations in the genes encoding UFSP2 or UFBP1 were also characterized in hip dysplasia of Beukes and Sohat type, respectively [53,54]. In the case of UFBP1, the mutation generated a premature stop codon and loss of protein expression. UFBP1 associates with the transcription factor SOX9 to prevent its ubiquitination and degradation [54]. The interaction between UFBP1 and SOX9 regulates the expression of type II collagen [54], whose familial mutations are responsible for Sohat-type hip dysplasia.

Finally, gene amplifications or deletions of components of the UFM1 pathway have been reported in different human carcinomas [55]. Remarkably, UFL1 physically interacts with and stabilizes CDK5RAP3, which was reported as a tumor suppressor by controlling β-catenin and the NF-κB pathway [20,58,59]. While UFL1 was identified as a tumor suppressor in hepatocarcinoma through NF-κB inhibition [29], it could also act as an oncogene in lung adenocarcinoma through a direct stabilization of p120 catenin [60]. Whether both functions require CDK5RAP3 is unclear. These conflicting results suggest that ufmylation might have opposite consequences depending on the substrate availability in the different cancer types or disease stages. As an example, one selective pharmacological inhibitor of UBA5 was able to reduce the proliferation of some specific lung cancer cell lines, highlighting a differential expression of the enzyme and its possible implications to cancer therapy [61]. Recently, a chemoproteomic screening also identified UBA5 as a putative target to treat pancreatic cancer [62].

Novel physiological outputs

UFM1 pathway in autophagy

Two unbiased screenings revealed the UFM1 cascade as a possible modulator of autophagy [63,64]. First, all core members of the Ufm1 pathway scored high on a functional CRISPR screening for modifiers of p62 expression [63]. P62 is a key adaptor protein in the autophagy process that connects autophagosomes to their cargo delivery via the recognition of LC3 [65]. Knocking down components of the ufmylation conjugation system led to accumulation of p62 [63]. In addition, p62 turnover is slower in cells stimulated to undergo macro-autophagy when UFM1 expression is inhibited [63]. An impairment of macro-autophagy was also observed in HSC and bone marrow cells with genetic deletion of UFL1, concomitantly to UPR activation [33], suggesting a global alteration of the proteostasis network. Another screening used genome wide CRISPR interference to identify activators or inhibitors of ER-phagy [64]. Contrary to macro-autophagy regulation, ER-phagy is independent of the energy sensor AMPK and this process removes the bulk of the ER compartment to promote its degradation by the lysosom [66]. UFL1 and UFBP1 were identified as activators of ER-phagy under prolonged nutrient starvation [64]. The loss of the PCI domain of UFBP1 abolished this regulation, but the mutation of all its putative ufmylation lysine residues did not. This suggests an involvement of other unknown downstream substrates of ufmylation in the regulation of autophagy. Although a link is emerging between the activity of the UFM1 pathway and macroautophagy, it is still necessary to understand whether this crosstalk is direct or secondary to other defects in the proteostasis network.

Ribosomal proteins as main ufmylation targets

Recent evidence highlights ribosomal proteins as substrates for ufmylation [25,67]. A first screening for ribosomal associated proteins (RAP) identified UFL1 as an interactor of 80s assembled ribosomes [67]. In addition, three ribosomal subunits, uS3, uS10 and uL16 have been shown to be ufmylated in endogenous conditions [67]. These three ribosomal subunits are located close to the mRNA entry channel, indicating that ufmylation might coordinate mRNA interactions. A second study identified RPL26 as one of the primary ufmylation substrates using the HEK293 cell line [25]. RPL26 is a highly conserved, but mostly uncharacterized, ribosomal protein. Two lysines, K132 and K134, were ufmylated on RPL26 by the fully assembled UFL1-UFBP1-CDK5RAP3 complex at the ER [25]. The genetic deletion of UFL1 or UFBP1 expression abolished RPL26 ufmylation but CDK5RAP3 deletion favored mono-ufmylation over di-ufmylation of RPL26, suggesting a new possible role of CDK5RAP3 in poly-ufmylation [25]. RPL26 ufmylation was also detected on fully assembled ribosomes [25]. In cells deficient in UFM1 or UFSP2 expression (unable to deconjugate UFM1), the alteration of RPL26 ufmylation did not change the footprint distribution of its associated mRNA transcripts, showing little translational disruption [25]. Another recent study identified that RPL26 ufmylation occurs following the accumulation of defective nascent translational products at the ER [68]. The proposed mechanism was different from the canonical effects of ERAD or other cytosolic ribosome quality control systems and promoted a faster turnover of stalled ribosomes in a lysosmal-dependent fashion [68]. In cells lacking functional ufmylation, the accumulation of blocked translocons and partially translated products resulted in abnormal levels of ER stress under high secretory pressure [68].

Ufmylation in the DNA damage response

A recent study provided the first indication of ufmylation activity at the nucleus [69]. The assembly of a protein complex containing MRE11, RAD50 and NBS1 (known as the MRN complex) initiates the DNA damage response (DDR) to double-strand breaks [70]. The MRN complex then recruits the ATM kinase (a key sensor of the DDR) at sites of DNA damage to activate downstream targets needed for repair. UFL1 is also recruited by the MRN platform quickly after double strand breaks and accumulates in nuclear foci containing the lesions [69]. UFL1 activates ATM by monoufmylating H4 histone at K31, an effect reversed by UFSP2 overexpression or an inactive UFL1 mutant [69]. ATM also phosphorylates UFL1 at Ser462 and creates a positive feedback loop by enhancing UFL1 activity [69], suggesting a tight interplay between the DDR and the UFM1 pathway. This new function of the UFM1 pathway is also supported by a second study showing ufmylation of the subunit MRE11 of the MRN complex increasing ATM activity [71]. A pathogenic mutation of MRE11 (G285C) in human uterine carcinoma produced a similar phenotype as the MRE11 ufmylation defective mutant (K282R). Thus, novel functions of the UFM1 pathway are emerging beyond proteostasis control in compartments other than the ER.

Concluding remarks

The chase for UFM1 substrates

The UFM1 pathway was discovered a decade ago but the mapping of its substrates and the universe of its interactomes remain mostly terra incognita. The chase for UFM1 substrates started with the identification of UFBP1 and then ASC1 using in vitro assays, but later pull-down screenings for UFM1 have not confirmed these results [25]. In addition, multiple studies characterized interactions between UFM1 pathway components and other proteins (such as SOX9, IRE1, Nf-κB) preventing their subsequent ubiquitination rather than demonstrating the formation of a UFM1 covalent adduct [20,41,57]. The difficulty in the identification of substrates for UFM1 likely arises from the conditions used for UFM1 conjugation screenings, which are in general performed under basal cellular conditions, limiting the exploration of the ‘ufmylome’. Based on the possible biomedical applications of the pathway, there is a current urgency in assessing UFM1 conjugation profiles during cellular stress, pathologic conditions or complex processes such as cell division and differentiation (see Outstanding questions).

Outstanding questions.

When is the ufmylation needed during various cellular events?

Can a ufmylation event act as a signal between the ER and the nucleus?

Can small molecules be developed to interfere with the UFM1 pathway for disease intervention?

How are UFM1 substrates tuned on a cell type and stimuli-dependent manner?

Ufmylation as a regulator of proteostasis

Historically, ufmylation has been connected to ER proteostasis but it is not always clear how this function is supported by the UFM1 pathway. Considering the localization of certain components of the UFM1 machinery at the ER membrane, multiple studies focused on the local effects of ufmylation on ER-stress response or ribosomes biology. Overall, recent evidences suggest a role of the ufmylation pathway in sustaining protein secretion, resulting in improved ER proteostasis (Figure 3). First, ufmylation of RPL26 may allow cells to keep the ER translocon function under high secretory conditions (physiological ER stress) by tuning ribosome turnover [68]. Second, the genetic disruption of UFM1 expression under basal secretory activity results in marked changes in the abundance of transcripts coding for extra-cellular matrix components [25], in addition to the upregulation of genes related to the ER translocation pathway [68]. These observations suggest the occurrence of a compensatory response in UFM1 deleted cells to maintain a normal secretory capacity. Finally, some components of the UFM1 pathway appear to regulate ER structure and organization in specific cell types such as plasma cells [26]. In particular, UFBP1 expression has been shown to trigger ER expansion [20,26], also occasionally forming organized smooth ER substructures (OSERs) [20] (and also C.Hetz laboratory, unpublished observations). The loss of a well-developed ER network in cells with high secretory activity is predicted to result in chronic stress and the engagement of a terminal UPR reaction. Overall, the connection between the UFM1 pathway and ER stress, ribosome function, secretion and autophagy suggest a central role of the pathway in proteostasis control. Another emerging and complementary possibility lies in the occurrence of ufmylation of transcription factors or in ufmylation activity at the nucleus itself. Therefore, it will be interesting to test the idea whether ER proteostasis disruptions can specifically alter ufmylation activity at the nucleus, directly regulating transcriptional programs related to the ER proteostasis or other stress responses.

Figure 3. Control of proteostasis by the ufmylation pathway.

RPL26 is one of the main ufmylation substrates. This ufmylation event tunes ER ribosome turnover and controls biogenesis of secreted proteins. In addition, deficiency in ufmylation feeds back to alter the expression of transcripts of extracellular matrix components. The mechanisms behind this regulation are unknown but could result in further imbalance in ER protein load because collagen proteins are the most abundant ER cargo. Another way for ufmylation to control ER stress would be through the targeting of transcription factors involved in ER proteostasis. Indeed ufmylation events at the nucleus are possible following the relocalization of UFL1. The remodeling of chromatin by ufmylation to alter transcriptional programs also appears as an exciting possibility. Histone ufmylation has been connected to the DNA damage response but it is likely that other functions are related to this type of regulation. Lastly, ufmylation components such as UFBP1 promote ER expansion and reorganization, which could be involved in the collapse and cell death observed in cells with high secretory activity and deficient for ufmylation components.

Ufmylation as a therapeutic target

Human genetic studies have connected ufmylation to developmental diseases and cancer, but a recent genome wide screening found genetic variants of the UFM1 pathway as risk factors for Parkinson’s disease [72]. Considering that ER stress is a transversal feature of neurodegenerative diseases [73,74] the role of ufmylation in brain pathology needs further investigation. In addition, memory formation and learning behaviors have been shown to involve components of the UPR [75,76]. Recently, therapies targeting ER stress modulators have risen as relevant therapeutic options for neurodegenerative diseases [77]. Since the UFM1 pathway appears to be a downstream effector of the UPR, interventions aimed at precise outputs of the UPR might be possible through selective control of ufmylation events. In addition, ufmylation appears to have a protective function in many other pre-clinical models of disease, including liver, heart and gut injuries. All these studies reinforce the notion of ufmylation as a valid target for future therapeutic interventions.

Highlights.

The known functions of the UFM1 pathway mostly encompass the control of the proteostasis network, highlighting the involvement of the ER stress response known as the unfolded protein response (UPR).

Recent discoveries have revealed unexpected roles for the UFM1 pathway in the DNA damage response, ribosome biology, autophagy, and gene expression control and cell differentiation.

A recent discovery characterized the UFM1 conjugation to ribosome subunit RPL26 as a unique way for cells with high secretory activity to tune ribosome turnover.

The study of pre-clinical models of multiple diseases (liver, brain, intestine and heart injuries) identified UFM1 conjugation as an important protective pathway.

Genetic alterations to the UFM1 pathway are linked to human diseases affecting the nervous system.

Acknowledgements.

This work was directly funded by FONDECYT 3080702 (Gerakis Y.); FONDAP program 15150012, Millennium Institute P09-015-F, CONICYT-Brazil 441921/2016-7, FONDEF ID16I10223, FONDEF D11E1007 and FONDECYT 1180186 (Hetz C.). In addition, we thank the support from the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research FA9550-16-1-0384, and Muscular Dystrophy Association, US Office of Naval Research-Global (ONR-G) N62909-16-1-2003 (Hetz C.); and NIH/NIDDK (1R01DK113409) (Honglin Li)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest statement. We declare no conflict of interest in this article.

References

- [1].Komander D and Rape M (2012) The Ubiquitin Code. Annu. Rev. Biochem, 81, 203–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Komatsu M et al. (2004) A novel protein-conjugating system for Ufm1, a ubiquitin-fold modifier. EMBO J, 23, 1977–1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Merbl Y et al. (2013) Profiling of ubiquitin-like modifications reveals features of mitotic control. Cell, 152, 1160–1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wang M and Kaufman RJ (2016) Protein misfolding in the endoplasmic reticulum as a conduit to human disease. Nature, 529, 326–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hetz C et al. (2013) Targeting the unfolded protein response in disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov, 12, 703–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kang SH et al. (2007) Two Novel Ubiquitin-fold Modifier 1 (Ufm1)-specific Proteases UfSP1 and UfSP2. J. Biol. Chem, 282, 5256–5262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ha BH et al. (2008) Structural basis for Ufm1 processing by UfSP1. J. Biol. Chem, 283, 14893–14900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ha BH et al. (2011) Structure of ubiquitin-fold modifier 1-specific protease UfSP2. J. Biol. Chem, 286, 10248–10257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yoo HM et al. (2014) Modification of ASC1 by UFM1 Is Crucial for ERα Transactivation and Breast Cancer Development. Mol. Cell, 56, 261–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ishimura RM et al. (2017) A novel approach to assess the ubiquitin-fold modifier 1-system in cells. FEBS Lett, 591, 196–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bacik J-P et al. (2010) Crystal structure of the human ubiquitin-activating enzyme 5 (UBA5) bound to ATP: mechanistic insights into a minimalistic E1 enzyme. J. Biol. Chem, 285, 20273–20280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Xie S (2014) Characterization, crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic analysis of the Uba5 fragment necessary for high-efficiency activation of Ufm1. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Commun, 70, 765–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Padala P et al. (2017) Novel insights into the interaction of UBA5 with UFM1 via a UFM1-interacting sequence. Sci. Rep, 7, 508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mashahreh B et al. (2018) Trans-binding of UFM1 to UBA5 stimulates UBA5 homodimerization and ATP binding. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol, 32, 2794–2802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Habisov S et al. (2016) Structural and Functional Analysis of a Novel Interaction Motif within UFM1-activating Enzyme 5 (UBA5) Required for Binding to Ubiquitin-like Proteins and Ufmylation. J. Biol. Chem, 291, 9025–9041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Liu G et al. (2009) NMR and X-RAY structures of human E2-like ubiquitin-fold modifier conjugating enzyme 1 (UFC1) reveal structural and functional conservation in the metazoan UFM1-UBA5-UFC1 ubiquination pathway. J. Struct. Funct. Genomics, 10, 127–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mizushima T et al. (2007) Crystal structure of Ufc1, the Ufm1-conjugating enzyme. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun, 362, 1079–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zheng M et al. (2008) UBE1DC1, an ubiquitin-activating enzyme, activates two different ubiquitin-like proteins. J. Cell. Biochem, 104, 2324–2334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Tatsumi K et al. (2010) A novel type of E3 ligase for the Ufm1 conjugation system. J. Biol. Chem, 285, 5417–5427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wu J et al. (2010) A novel C53/LZAP-interacting protein regulates stability of C53/LZAP and DDRGK domain-containing Protein 1 (DDRGK1) and modulates NF-kappaB signaling. J. Biol. Chem, 285, 15126–15136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Cai Y et al. (2015) UFBP1, a Key Component of the Ufm1 Conjugation System, Is Essential for Ufmylation-Mediated Regulation of Erythroid Development. PLOS Genet, 11, e1005643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Neziri D et al. (2010) Cloning and molecular characterization of Dashurin encoded by C20orf116, a PCI-domain containing protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Gen. Subj, 1800, 430–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lemaire K et al. (2011) Ubiquitin Fold Modifier 1 (UFM1) and Its Target UFBP1 Protect Pancreatic Beta Cells from ER Stress-Induced Apoptosis. PLoS ONE, 6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Pick E et al. (2009) PCI Complexes: Beyond the Proteasome, CSN, and eIF3 Troika. Mol. Cell, 35, 260–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Walczak CP et al. (2019) Ribosomal protein RPL26 is the principal target of UFMylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci, 116, 1299–1308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhu H et al. (2019) Ufbp1 promotes plasma cell development and ER expansion by modulating distinct branches of UPR. Nat. Commun, 10, 1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Xi P et al. (2013) DDRGK1 Regulates NF-κB Activity by Modulating IκBα Stability. PLOS ONE, 8, e64231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Jiang H et al. (2009) Tumor suppressor protein C53 antagonizes checkpoint kinases to promote cyclin-dependent kinase 1 activation. Cell Res, 19, 458–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kwon J et al. (2010) A Novel LZAP-binding Protein, NLBP, Inhibits Cell Invasion. J. Biol. Chem, 285, 12232–12240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zhu Y et al. (2018) Proteomic and biochemical analysis reveal a novel mechanism for promoting ubiquitination and degradation by UFBP1, a key component of Ufmylation. J. Proteome Res, 17, 1509–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Yang R et al. (2019) CDK5RAP3, a UFL1 substrate adaptor, is critical for liver development. Development, doi: 10.1242/dev.169235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tatsumi K et al. (2011) The Ufm1-activating enzyme Uba5 is indispensable for erythroid differentiation in mice. Nat. Commun, 2, 181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zhang M et al. (2015) RCAD/Ufl1, a Ufm1 E3 ligase, is essential for hematopoietic stem cell function and murine hematopoiesis. Cell Death Differ, 22, 1922–1934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Liu D et al. (2011) Tumor suppressor Lzap regulates cell cycle progression, doming and zebrafish epiboly. Dev. Dyn, 240, 1613–1625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhang Y et al. (2012) Transcriptional Regulation of the Ufm1 Conjugation System in Response to Disturbance of the Endoplasmic Reticulum Homeostasis and Inhibition of Vesicle Trafficking. PLoS ONE, 7, doi:10.1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Cai Y et al. (2019) Indispensable role of the Ubiquitin-fold modifier 1-specific E3 ligase in maintaining intestinal homeostasis and controlling gut inflammation. Cell Discov, 5, doi: 10.1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hetz C and Papa FR (2018) The unfolded protein response and cell fate control. Mol Cell, 69, 169–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Gass J et al. (2008) The unfolded protein response of B-lymphocytes: PERK-independent development of antibody-secreting cells. Mol Immuno, 45, 1035–1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ma Y et al. (2010) Plasma cell differentiation initiates a limited ER stress response by specifically supressing the PERK-dependent branch of the unfolded protein response. Cell Stress Chap, doi: 10.1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Liu J et al. (2017) A critical role of DDRGK1 in endoplasmic reticulum homoeostasis via regulation of IRE1α stability. Nat. Commun, 8, doi:10.1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Shiwaku H et al. (2010) Suppression of the novel ER protein Maxer by mutant ataxin-1 in Bergman glia contributes to non-cell-autonomous toxicity. EMBO J, 29, 2446–2460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Lin KY et al. (2015) Tumor Suppressor Lzap Suppresses Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling to Promote Zebrafish Embryonic Ventral Cell Fates via the Suppression of Inhibitory Phosphorylation of Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3. J. Biol. Chem, 290, 29808–29819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Miller C et al. (2017) RCAD/BiP pathway is necessary for the proper synthesis of digestive enzymes and secretory function of the exocrine pancreas. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol., 312, G314–G326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Li J et al. (2018) Ufm1-Specific Ligase Ufl1 Regulates Endoplasmic Reticulum Homeostasis and Protects Against Heart Failure. Circ. Heart Fail, 11, e004917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lu H et al. (2008) The Identification of Potential Factors Associated with the Development of Type 2 Diabetes. Mol. Cell. Proteomics MCP, 7, 1434–1451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Azfer A et al. (2006) Activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress response during the development of ischemic heart disease. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol, 291, H1411–H1420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Pang Q et al. (2015) UFM1 Protects Macrophages from oxLDL-Induced Foam Cell Formation Through a Liver X Receptor α Dependent Pathway. J. Atheroscler. Thromb, 22124–22128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Liu H et al. (2014) Mallory-Denk Body (MDB) Formation Modulates Ufmylation Expression Epigenetically in Alcoholic Hepatitis (AH) and Non Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH). Exp. Mol. Pathol, 97, 477–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Liu H et al. (2014) Ufmylation and FATylation Pathways are Down Regulated in Human Alcoholic and Non Alcoholic Steatohepatitis, and Mice Fed DDC, where Mallory-Denk Bodies (MDBs) Form. Exp. Mol. Pathol, 97, 81–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Muona M et al. (2016) Biallelic Variants in UBA5 Link Dysfunctional UFM1 Ubiquitin-like Modifier Pathway to Severe Infantile-Onset Encephalopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet, 99, 683–694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Colin E et al. (2016) Biallelic Variants in UBA5 Reveal that Disruption of the UFM1 Cascade Can Result in Early-Onset Encephalopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet, 99, 695–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Duan R et al. (2016) UBA5 Mutations Cause a New Form of Autosomal Recessive Cerebellar Ataxia. PLOS ONE, 11, e0149039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Rocco MD et al. (2018) Novel spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia due to UFSP2 gene mutation. Clin. Genet, 93, 671–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Egunsola AT et al. (2017) Loss of DDRGK1 modulates SOX9 ubiquitination in spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia. J. Clin. Invest, 127, 1475–1484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Wei Y and Xu X (2016) UFMylation: A Unique & Fashionable Modification for Life Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics, 14, 140–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Nahorski MS et al. (2018) Biallelic UFM1 and UFC1 mutations expand the essential role of ufmylation in brain development. Brain, 141, 1934–1945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Hamilton EMC et al. (2017) UFM1 founder mutation in the Roma population causes recessive variant of H-ABC. Neurology, 89, 1821–1828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Wang H et al. (2007) LZAP, a Putative Tumor Suppressor, Selectively Inhibits NF-κB. Cancer Cell, 12, 239–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Zheng CH et al. (2018) CDK5RAP3 suppresses Wnt/β-catenin signaling by inhibiting AKT phosphorylation in gastric cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. CR, 37, doi:10.1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Kim CH et al. (2013) Overexpression of a novel regulator of p120 catenin, NLBP, promotes lung adenocarcinoma proliferation. Cell Cycle, 12, 2443–2453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].da Silva SR et al. (2016) A selective inhibitor of the UFM1-activating enzyme, UBA5. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett, 26, 4542–4547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Roberts AM et al. (2017) Chemoproteomic screening of covalent ligands reveals UBA5 as a novel pancreatic cancer target. ACS Chem Biol, 12, 899–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].DeJesus R et al. (2016) Functional CRISPR screening identifies the ufmylation pathway as a regulator of SQSTM1/p62. ELife, 5, e17290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Liang JR et al. (2019) A genome-wide screen for ER autophagy highlights key roles of mitochondrial metabolism and ER-resident UFMylation’, bioRxiv, 561001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Kroemer G et al. (2010) Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol Cell, 280, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.023) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Song S et al. (2018) Crosstalk of ER stress-mediated autophagy and ER-phagy: Involvement of UPR and the core autophagy machinery. J. Cell. Physiol, 233, 3867–3874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Simsek D et al. (2017) The mammalian ribo-interactome reveals ribosome functional diversity and heterogeneity. Cell, 169, 1051–1065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Ye Y et al. (2019) UFMylation of RPL26 links translocation-associated quality control to endoplasmic reticulum protein homeostasis Cell Res, under press; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Qin B et al. (2019) UFL1 promotes histone H4 ufmylation and ATM activation. Nat. Commun, 10, 1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Jackson SP and Bartek J (2009) The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature, 461, 1071–1078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Wang Z et al. (2019) MRE11 UFMylation promotes ATM activation, Nucleic Acids Res, 47, 4124–4135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Nalls MA et al. (2014) Large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies six new risk loci for Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Genet, 46, 989–993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Hetz C and Saxena S (2017) ER stress and the unfolded protein response in neurodegeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurol, 13, 477–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Mallucci G and Smith H (2016) The unfolded protein response : mechanisms and therapy of neurodegeneration. Brain, 139, 2113–2121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Martínez G et al. (2016) Regulation of Memory Formation by the Transcription Factor XBP1. Cell Rep, 14, 1382–1394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Costa-Mattioli M et al. (2007) eIF2alpha phosphorylation bidirectionally regulates the switch from short-to long-term synaptic plasticity and memory. Cell, 129, 195–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Valenzuela V et al. (2016) Gene therapy to target ER stress in brain diseases. Brain Res, 1648, 561–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]