Abstract

In recent years, the emphasis of scientific inquiry has shifted from whole-genome analyses to an understanding of cellular responses specific to tissue, developmental stage or environmental conditions. One of the central mechanisms underlying the diversity and adaptability of the contextual responses is alternative splicing (AS). It enables a single gene to encode multiple isoforms with distinct biological functions. However, to date, the functions of the vast majority of differentially spliced protein isoforms are not known. Integration of genomic, proteomic, functional, phenotypic and contextual information is essential for supporting isoform-based modeling and analysis. Such integrative proteogenomics approaches promise to provide insights into the functions of the alternatively spliced protein isoforms and provide high-confidence hypotheses to be validated experimentally. This manuscript provides a survey of the public databases supporting isoform-based biology. It also presents an overview of the potential global impact of AS on the human canonical gene functions, molecular interactions and cellular pathways.

Keywords: alternative splicing, isoform, protein function, pathway, interaction, context-specific

Introduction

The concept of alternative splicing (AS) was first proposed by Sambrook [1] and Gilbert [2] in 1978. Since then, AS has emerged as one of the central mechanisms underlying the diversity, adaptability and robustness of metazoan cells [3–5]. It is estimated [6] that over 95% of human multi-exon genes are subjected to AS catalyzed by the spliceosome (reviewed by Papasaikas and Valcárcel [7]). The use of different combinations of alternatively spliced exons enables a single gene to encode multiple proteins with specific, and sometimes different, biological functions. The broad repertoire of isoforms produced by AS allows organisms to optimize functional, structural and spatial profiles of their proteomes enabling them to respond and thrive in ever-changing environments.

Regulatory elements of eukaryotic gene expression coordinate selective inclusion of exons into a contiguous transcript that can be translated into a functional protein. Several excellent reviews offer insights into the mechanistic details of the AS process [8, 10, 11]. A general definition and nomenclature for AS events are described in Sammeth et al. [8, 12–14]. Figure 1 outlines major patterns involved in AS.

Figure 1.

(A) Five major patterns of AS; (B) the core splicing signals required for the recognition of the intron–exon boundaries and the accurate removal of introns by the splicing machinery [8]: 5′ splice donor, 3′ splice acceptor, branchpoint and polypyrimidine tract; (C) The splicing regulatory elements (SREs) represented by cis-acting sequence motifs in exons or introns recognized by trans-acting splice factor proteins [9]. SREs are classified as exonic splice enhancers, exonic splice silencers, intronic splice enhancers and intronic splice silencers. The trans-acting splicing factors include (a) splice enhancing SR-proteins that bind splice enhancers to promote exon inclusion and (b) splice silencing proteins such as heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) that bind splicing silencers and inhibit exon recognition.

Estimates for the number of protein-coding genes in the Human genome range between 19 000 and 22 500 [15, 16]. These protein-coding genes are responsible for the encoding of over 79 000 proteins [17–19]. This mismatch between the number of genes and proteins may in part be explained by the proteomic diversity resulting from AS. Hu et al. [20] detected 31 566 novel transcripts with protein-coding potential by filtering ab initio predictions with 50 RNA-Seq data sets from diverse tissues/cell lines. The authors estimated the total number of human transcripts with a protein-coding potential to be at least 204 950. A recent study by Yang et al. [21] concludes that in the context of the global interactome, isoforms exhibit exclusively unique patterns that could classify them as individual proteins rather than as alternative forms of a canonical transcript. Interactions specific to alternative isoforms may be associated with particular functional modules and expressed in a highly tissue-specific manner. A number of databases (e.g. IntAct [22], BindingDB [23]) contain the data describing protein–protein interactions (PPIs) for context-specific isoforms. These context-specific isoforms differ in transcript stability, translational activity and biological functions of their products [8, 24]. Moreover, context-specific splicing of alternative binding motifs or interaction domains could affect PPI and protein–ligand interactions leading to significant changes in the architecture of signaling and regulatory networks (Figure 2). It is important to remember that a number of transcriptome-wide processes besides AS, such as alternative transcription initiation, alternative polyadenylation and alternative translation initiation, may also affect protein expression. These regulatory layers are highly coordinated and interdependent (reviewed by De Klerk and t’ Hoen [25]). See Supplementary File SF-1 for a more detailed description of splicing factors and the AS mechanisms and regulation.

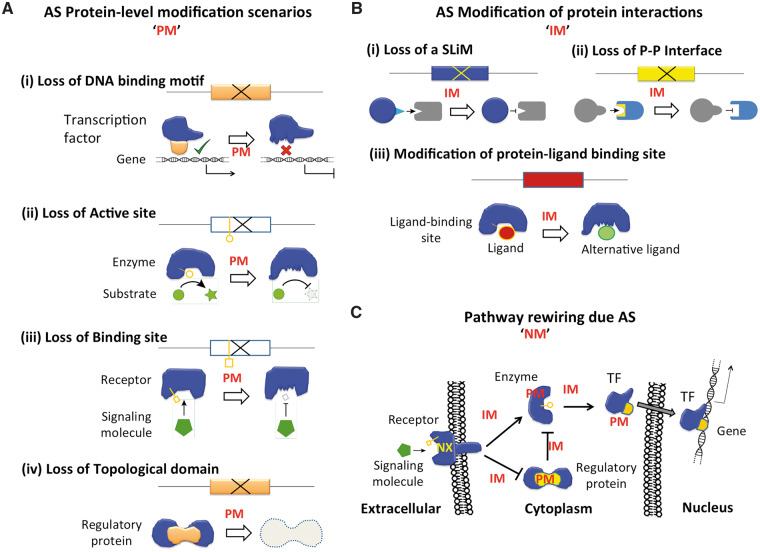

Figure 2.

Functional impact of AS of protein isoforms. (A) Splicing events lead to the loss or modification of functional domains and sites (e.g. DNA-binding sites, active sites of enzymes, etc.) and consequently to the modification of function in comparison with the canonical isoform. (B) AS affects protein interactions with substrates and other proteins because of the use of alternative SLIMs and binding interfaces. (C) Changes in the protein functions (A) and protein interactions (B) lead to the rewiring of the molecular networks.

The comparison of the AS of orthologs across multiple organisms holds the promise of exposing evolutionary patterns and phylogenetic relationships. A discussion of this important topic is beyond the scope of this publication, and we refer the reader to the excellent articles that address this directly [26–30].

Aberrant AS has been implicated in a broad spectrum of human genetic disorders, including diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases, cystic fibrosis, myotonic dystrophy, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and others (see Taneri et al. [31] for a comprehensive review). Defects in AS, as well as the mutations that result in disruptions of constitutive splicing programs, comprise >9% of published mutations [32]. Using a probabilistic approach, Lim et al. [33] predicted that approximately one-third of all disease-causing mutations alter pre-mRNA splicing. Disease-associated mutations usually induce exon skipping, the formation of new exon/intron boundaries or cause the activation of new cryptic exons as a result of alterations at donor/acceptor sites [32]. Anomalous splicing was also demonstrated for a significant number of genes correlated with cancer progression and metastasis. Each of the ‘hallmarks of cancer’ (e.g. enhanced proliferation, acquisition of angiogenic, invasive, antiapoptotic, survival and immune escape mechanisms) was shown to be associated with a switch in AS (reviewed by Oltean and Bates [34]).

However, the understanding of the functional impact of AS on a variety of context-specific biological processes faces some significant challenges. These include inter alia substantial difficulties in the detection of the low-abundance context-specific isoforms, proteomic validation of protein isoforms and characterization of their biological functions. Arguably, some of these challenges may be alleviated by efficient computational analysis that can provide high-confidence hypotheses regarding the potential functions of the AS isoforms to be tested experimentally. A detailed discussion of a number of computational technologies and software tools for the analysis of AS isoforms, which have been developed in recent years, is presented in Supplementary File SF-2.

Although a large number of publications address the functional consequences of AS for specific contexts and conditions of interest, the global functional impact of alternatively spliced protein isoforms is not yet clear. This article presents an analysis of the potential effect of AS on the functionality of human proteome and a survey of public databases supporting isoform-based biology. It also addresses some of the challenges associated with isoform-level analyses and emphasizes the importance of systems-level integrated studies of isoforms on the genomic, proteomic and network level. An overview of the biological impact of other AS-related cellular machinery (e.g. the role of the noncoding RNA transcripts resulting from AS) and experimental and computational approaches for the prediction of the isoforms functions is reviewed in other publications [35–40] and is beyond the scope of this manuscript.

Types of information supporting isoforms analysis

A growing number of publications [36, 39, 41] have emphasized the need for the integration of various classes of biological information (e.g. genomic, proteomic, functional, phenotypic, contextual) to support isoform-based modeling and analysis. The systematic integration of these complementary classes of data would lead to a substantial improvement in the accuracy of predictive models. These models would be further refined by incorporating experimental information specific for various spatial and temporal contexts (e.g. tissues or developmental stages). Such integrative proteogenomics methods promise to provide insights into the functions of the alternatively spliced protein isoforms and their involvement in cellular networks. However, the information required for the development of such integrative isoform-based contextual models specific to various tissues, developmental stages and disease states is disseminated in multiple databases. This information should undergo integration across different data types and resources to provide a structured information field accessible by modeling algorithms. On a basic level, the genomic DNA provides the foundation for gene, transcript and isoform prediction and acts as a reference for the comparison of experimentally determined sequence data. Transcriptomics data contains information about intron and exon boundaries and associated expression levels. This information may also be used for the prediction of the isoforms involvement in functional modules and networks characteristic for the context under investigation.

The protein sequences of the known protein-coding isoforms available in the databases are extensively annotated with multiple data types, such as proteomics, contextual and structural data, functional annotations, relevant protein families and domains, interactions and pathways. Vertical integration of various classes of information from DNA to molecular pathways as well as a horizontal integration of similar types of information originating from different sources will provide a rich knowledge base for the efficient mining of isoform-based data and the development of predictive contextual models.

Sources of isoforms sequence data

Table 1 lists the sources of isoform annotations. It includes the major authoritative sources providing main classes of information describing proteins functionality and functional and structural features.

Table 1.

Some of the major classes of protein and isoform-relevant data with sources representative of each class

| Classes of data | Source |

|---|---|

| Genomic | Ensembl [18], RefSeq [42] |

| Transcripts | Ensembl, RefSeq |

| Protein sequence | Ensembl, RefSeq, UniProtKB/SwissProt[43] |

| Proteomic | ProteomicsDB [44], Human Protein Atlas [45], PeptideAtlas [46], MaxQB [47] |

| Canonical isoforms | APPRIS [48], Ensembl, UniProt, UCSC Browser |

| Contextual | GTEx [49], Human Protein Atlas, TIGER [50], BioGPS [51], HPM [52] |

| Functional classification and hierarchies | IUPHAR [53], Enzyme [54], GO [55], UniProt keywords, cytokine, growth factors and chemokine ligand database [56], InterPro parent–child tree [57], TFClass [58] |

| Pathway-related | KEGG [59], Reactome [60], NCI [61], BioCarta [62], IPAD [63], STRING [64], TRANSPATH [65], Pathway Commons [66], WikiPathways [67] |

| Structure | ASPicDB [68], AS-ALPS [69], I-TASSER [70], MAISTAS [71], ProSAS [72], RaptorX [73, 74] |

| Interactions | IBIS [75], STRING, HPRD [76], MINT[77], Biogrid [78], IIIDB [79], IntAct [22], BindingDB [23] |

The study of AS protein isoforms from a given genome requires a reliable set of predicted genes with accurately annotated exon and intron boundaries. The Genome Reference Consortium (GRC) curates and distributes the standard highest quality reference human genome assembly available to date. It provides the foundation for the interpretation of AS events. The last two major released assemblies (GRCh37 in 2009 and GRCh38 in 2013) are both widely used for isoform-based analyses and the transcript assembly methods that rely on a high-quality reference genome. Errors in the annotations at this level may propagate through the downstream analysis, reducing the reliability of predicted effects of AS. Serving as primary sources of annotated genomic data, RefSeq and Ensembl provide annotated sequence data on the genomic, RNA and protein levels.

RefSeq provides a high-quality, curated nonredundant set of records for each DNA, RNA and protein sequence. Every record includes explicitly linked genome, transcript and protein sequence records cross-referenced to other databases and annotated with information describing sequence features and variations. The NCBI annotation pipeline [80] uses the genomic assembly, transcript, protein and RNA-Seq data to predict genes using the NCBI eukaryotic gene prediction tool Gnomon [80] followed by feature annotation. All protein-coding isoforms from the same gene are available in the NCBI Gene database under a single GeneID.

Ensembl is another authoritative source of isoforms information. It performs isoform prediction and automated annotation for selected eukaryotic (predominantly vertebrate) genomes and then merges this predicted gene set with the manually curated results from HAVANA [81] (Human and Vertebrate Analysis and Annotation). The merged gene set is available on the Ensembl website and from GENCODE [19], which provides further annotation based on manual curation and computational and experimental results. The Ensembl database offers a transparent cross-referencing from DNA to a transcript to protein sequences. It contains some degree of redundancy because of the inclusion of identical protein sequences resulting from differing transcripts. The APPRIS [48] database annotates the gene set from GENCODE with additional data, which is used to select a canonical isoform (see ‘Sources of isoforms annotations’ section for more details).

Protein-centric resources

A number of authoritative resources, such as UniProt, Ensembl and RefSeq, provide protein-centric sequence and annotation data. However, these databases use different methods for the identification of genes and isoforms leading to significant discrepancies in the number and content even in the initial set of protein isoforms (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the complete human proteomes from UniProt, Ensembl and RefSeq that include isoform information. Internal redundancy was removed before the comparison between the databases was performed, and only identical sequences were reported for the overlaps between the databases. This Venn diagram was drawn using InteractiVenn [82].

The UniProt Knowledgebase (UniProtKB)/SwissProt section from UniProt contains high-quality manually annotated protein sequence data. Unlike RefSeq, it does not provide individual records for isoforms with detailed annotations and features. All protein isoform sequences for a given gene are listed in a single entry under a single accession with details on how the isoform sequence differs in comparison with the canonical sequence. The annotations for each entry apply only to the canonical isoform. For example, the accession number for the FGFR1 gene products is P11362, and the isoform sequences are assigned labels from P11362-1 through P11362-21. Usually, the canonical isoform is assigned the ‘−1’ suffix, though this is not a strict rule as exceptions do exist.

As mentioned above, there are major differences in representation of the information relevant to the protein isoforms between the sequence databases. While some level of inconsistency is to be expected, as it reflects the nature of the field where the final ‘truth’ about the isoforms structure and function is yet to be determined, this discrepancy poses significant hurdles for researchers attempting to perform global isoform analyses. In some cases, the databases may contain a different number of transcripts and/or protein isoforms associated with the same gene. In other cases, the transcript sequences for the same gene may be different in different databases. These variations can be attributed to the differences in analytical, validation and selection procedures used by the databases. With many clinical labs using specific transcripts for the analysis, it is critical that these are reviewed and consolidated into the standard data structures and ontologies.

Figure 3 shows the results of a comparison of a number of human protein and isoform sequences between RefSeq, UniProtKB/SwissProt + TrEMBL and Ensembl. To compute the numbers presented in Figure 3, the sets of human protein sequences from each database were first processed to remove internal redundancy. The comparison between the databases was then performed on these nonredundant sets of isoforms sequences. For example, the number of unique isoforms sequences (79 150), is smaller than the number of protein entries (109 052) in RefSeq, apparently because of the internal sequence redundancy of the RefSeq database. As follows from Figure 3, there are significant differences between all of the above primary sources of isoform protein sequences.

The structural information describing AS protein isoforms is not yet sufficient to describe the variety of structural conformations in proteins introduced by the AS. The current release of Protein Data Bank (PDB) [83] contains information describing 1602 structures related to Human protein isoforms, obtained by performing a text Search for: ‘isoform and TAXONOMY is just Homo sapiens (human)’.

A number of resources for the prediction of the 2D and 3D structure of the AS protein isoforms were developed. ProSAS [68] supports the analysis of AS in the context of protein structures. AS-ALPS (alternative splicing-induced alteration of protein structure) [65] is designed for analyzing the effects of AS on protein structure, protein interactions and biological networks. MAISTAS [67] provides tools for automated structural evaluation of AS products. All these resources predict isoform 3D structures based on homology modeling based on high-sequence identity. However, they are not supporting a template-free modeling and thus cannot predict the 3D structures for the isoforms for which templates are not available.

Canonical isoforms

The notion of a major or principal ‘canonical’ isoform for each gene is defined differently by various sources (reviewed in Li et al. [41]). APPRIS [48, 84] (Annotating Principal Splice Isoforms database) selects a principal isoform for each gene in six vertebrate genomes (including human) and two invertebrate genomes. The ‘principal’ isoform is chosen based on the annotations such as structure, function and conservation for each transcript. However, as APPRIS is limited to the GENCODE/Ensembl data set, using other data sets presents problems in selection of the canonical isoform. UniProt [43, 85] defines the canonical isoforms as the most conserved, most prevalent or the most annotated isoform. In the absence of this information, the longest isoform is selected. UCSC Genome Browser [86, 87] and Ensembl [18, 88] designate the longest splice variant of a gene as the canonical isoform. NCBI RefSeq database does not produce an official set of ‘canonical’ transcripts but lists all transcripts associated with the particular gene. A number of studies have chosen some transcripts as ‘major’ because of their relatively high expression levels. Such definition was based on the observation that in human and mouse most genes express one primary transcript [84, 89, 90].

Sources of isoforms annotations

Multiple databases contain a variety of different classes of annotation data (Table 1) with UniProt, RefSeq and Ensembl providing the bulk of sequence-level annotations. The rich sets of protein sequence features offer evidence to support functional annotations.

The UniProtKB, RefSeq and Ensembl each provide a large compendium of various classes of integrated and cross-referenced information from multiple databases. This information describes protein isoforms, their known biological functions, PPI and protein–ligand interactions and associated biological pathways. These resources also provide the coordinates for a large number of sequence features such as domains, active and binding sites and transmembrane regions. Integration of a comprehensive set of annotations relevant to isoforms compiled from multiple databases is essential for the prediction of the isoforms functions and contextual modeling. However, such integration is complicated by the disparities between the databases. These include differences in sequences and annotations associated with each gene and its isoforms. Owing to these discrepancies, isoforms sequence features cannot be easily mapped onto the isoforms sequences unique to a particular database. The isoform-specific resource Splice-mediated Variants of Proteins [91] (SpliVaP) reports the differences in protein signatures in human splice-mediated protein isoform sequences and provides value-added annotations (e.g. domain composition and association with diseases).

Sources of pathways

Only a limited number of resources are addressing the need for integration of information relevant to isoform-based molecular interactions and cellular networks. To date, the isoform-based representation of PPIs and molecular pathways in the primary pathways databases (e.g. KEGG, NCI and Reactome) are absent or scarce. The PPI databases offer only the low-resolution PPIs, estimated on the gene level without consideration of the AS events that could have a profound effect on the PPIs. Here, we describe some of the resources supporting the isoform-based analyses.

The IIIDB [79] database of isoform–isoform interactions (IIIs) and isoform network modules includes the genome-wide predictions of the IIIs based on the analysis of RNA-Seq data sets, domain–domain interactions and known PPIs. The IIIDB also contains 1025 functional isoform-based network modules annotated with the Gene Ontology (GO)/pathway enrichment analysis for each isoform module.

MiasDB [92] is a database of molecular interactions associated with AS of human pre-mRNAs. It contains 938 interactions between human splicing factors, RNA elements, transcription factors, kinases and modified histones for 173 human AS events. Every database entry is annotated with the information describing the interaction partners, interaction type, AS type, tissue specificity, disease-relevant information, literature references and others.

A number of databases containing information on describing RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and RNA motifs relevant to contextual modeling have been developed in recent years. These include RBPDB [93], a repository of experimentally validated RBPs extracted from literature; SpliceAid-F [94], a curated database and a comprehensive knowledge base of human splicing factors, their RNA-binding sites and their interaction network; and ATtRACT [95], a curated database that contains information describing RBPs and associated motifs, as well a suite of tools for the motifs analysis.

PPIXpress [96] is a network reconstruction method that uses expression data at the transcript-level and identifies changes in protein connectivity because of AS. This approach establishes a direct correlation between individual protein interactions and underlying domain interactions in the global condition-independent protein interaction network. This correlation is further used to infer the condition-specific presence of interactions from the dominant protein isoforms.

The development of isoform-based pathways databases is inherently challenging and will require massive experimental, ontological and data mining efforts on behalf of the scientific community that hopefully will materialize in the not-so-distant future.

Sources of contextual data

Advances in functional genomics now allow shifting the emphasis of the scientific inquiry from the whole-genome analytical approaches to the understanding of cellular responses specific to cell or tissue type, gender, developmental stage or environmental conditions [97–100]. The traditional ‘one size fits all’ representations of metabolic and regulatory pathways need to undergo substantial modifications to reflect the contextual variations of biological processes.

The contextual processes are regulated by the complex splicing programs that orchestrate the alternative exon recognition and the generation of multiple mRNA isoforms. AS events are controlled by the various layers of co-transcriptional regulation in a context-specific manner. DNA methylation, chromatin structure, histone marks and nucleosome positioning play a crucial role in assembling a dynamic framework for interactions between the splicing and transcription machinery depending on cell or tissue type and developmental stage [101–103]. RBPs and context-specific splicing factors constitute splicing regulatory networks of transcripts and proteins that function in a coordinated manner specific for a particular phenotype or cell type. Such coordinated expression patterns were observed in multiple models and organisms [104–108]. The disruption of these splicing programs can lead to a variety of human disorders [13, 109].

A number of the major scientific efforts, such as Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx [49]) consortium, TiGER [50], TISSUES [110], BioGPS [51], TissueDistributionDB [111], VeryGene [112] and the EBI Gene Expression Atlas [113], HPM [52], ProteomicsDB [44] and the Human Protein Atlas [45], provide various types of tissue-specific data and annotations containing some information regarding tissue-specific isoforms. Santos et al. [110] have performed a thorough evaluation of tissue expression data obtained by a variety of experimental techniques. The authors have found a surprisingly good agreement between the data sets analyzed using different approaches. The authors advocate the possibility of the improvement of both quality and coverage of the tissue-specific information by combining the data sets. The TISSUES resource developed by the authors offers public access to the scored and integrated tissue-specific data available through a Web interface. GTEx project develops a database and associated tissue bank to support studies of the relationship between genetic variation and gene expression in a variety of human tissues. The GTEx pilot project includes an analysis of RNA sequencing data from 11 688 samples across 53 tissues from 714 individuals. It includes the description of the landscape of gene expression across tissues, a catalog of thousands of tissue-specific, shared regulatory expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) variants and the identification of signals from genome-wide association studies explained by eQTLs.

Potential effects of AS

In recent years, a number of AS isoforms have been characterized experimentally. Supplementary Table ST-7 provides a representative list of publications describing the functional repertoire of isoforms resulting from AS. Both experimental and computational analyses of the AS protein isoforms are significantly complicated by the fact that the functions of most of the isoforms may only be understood in the broader context of cellular response. Moreover, protein isoforms originating from the same gene may acquire novel functions that are different from their canonical counterparts.

Until recently, most biomedical reasoning was based on functions of canonical isoforms that were traditionally synonymous with a function of a gene or a gene product. AS, however, may result in a dramatic alteration of function of a canonical isoform, such as loss of the enzymatic activity, changes of biological role from activation to inhibition of a particular process or acquisition of a novel, not yet characterized function. It may also lead to the changes in protein subcellular location, tissue specificity or kinetic properties, compared with the canonical isoform.

Alterations of interaction partners because of AS may result in the rewiring of biological pathways and the involvement in a variety of biological processes not characteristic of the known function of the canonical isoform. The overview of these effects across the isoforms information available in major sequence databases presented below illustrates the effects of AS on various classes of proteins.

Modification of functions of canonical protein isoforms

We have performed a comparison of the composition of the sequence features in alternatively spliced protein isoforms with their functionally annotated canonical versions (as defined by the UniProt complete Human proteome [114]). See Supplementary File SF-3 for a detailed description of the data and analytical methods used in this study. The presence or absence of features such as active and binding sites, conserved functional domains and regions, signal peptides and motifs were identified and used for the reasoning regarding a potential loss or modification of the known functions of the canonical isoforms. Figures 4 and 5 show the numbers of protein functional features and the domains spliced out or modified in different categories of proteins as a result of AS. In addition, Supplementary Table ST-1 provides detailed information and a representative list of UniProt keywords associated with genes subjected to AS. As it follows from the Supplementary Table ST-1, a number of the UniProt keywords categories have higher than average number of the associated noncanonical isoforms per gene than in the complete proteome: 2.08 per gene in complete proteome versus 7.00 for the genes involved in Carnitine biosynthesis or 4.5 in Prostaglandin biosynthesis. Moreover, our preliminary results using the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test applied to the UniProt data showed statistically different distributions of average noncanonical isoform counts for the disease-related and non-disease-related genes (P-value = 1.5E-04). The disease-related genes appear to have a higher mean value (2.71) and variance (1.75), while the non-disease-related genes have lower mean value (2.08) and variance (0.84). The detailed analysis of this phenomenon is beyond the scope of this manuscript.

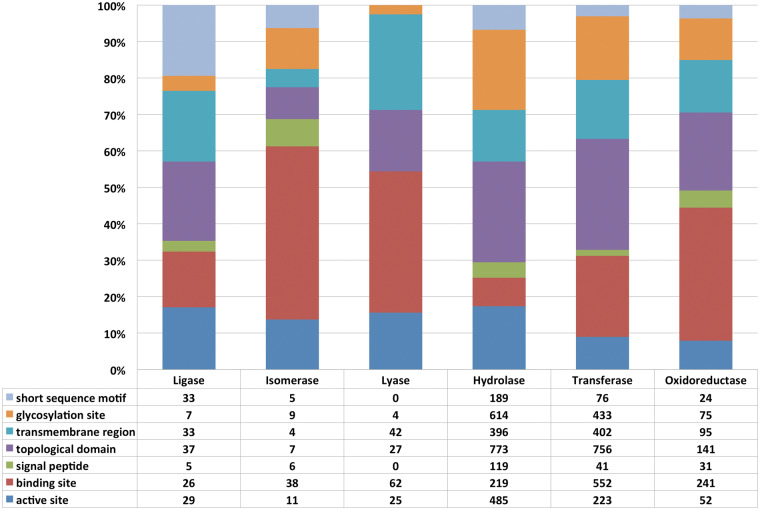

Figure 4.

Loss or modifications of the sequence features in the human alternatively spliced isoforms in comparison with the canonical isoforms involved in different biological processes. Total 100% represents all features under consideration that were lost because of AS in a particular functional category. The table contains the absolute numbers of the lost features for each functional category.

Figure 5.

Modification of sequence features in canonical enzymatic sequences because of AS. Total 100% represents the total number of features under consideration lost because of AS in a particular class of the enzymes. The table contains the absolute numbers of the lost features for each enzyme class.

As follows from Figure 4, DNA-binding regions constitute over 37% of the features spliced out of DNA-binding proteins; over 42% of the features spliced out of transporters are transmembrane domains, and over 41% of the features spliced out of the cell cycle proteins are short sequence motifs. In a significant number of cases, sequence modifications of AS protein isoforms were because of the inclusion of alternative exons. Supplementary Table ST-2 presents a detailed analysis of the number of sequence features, which have been lost or replaced from the canonical isoforms in the human (UniProt) proteome as a result of AS. Although, like UniProt, NCBI RefSeq provides a rich set of annotations for individual isoforms, we do not present the similar analysis based on RefSeq data for the following reasons: RefSeq does not systematically designate a single canonical isoform for each gene, which creates difficulties in performing comparative analysis. Moreover, the set of sequence feature annotations is highly variable between the various data sets provided by RefSeq (current data, the latest release and the latest patched release). Both of these reasons make the comparison of RefSeq protein isoforms and their functional characterization to be a significant effort beyond the scope of this publication.

These large-scale sequence modifications introduced by AS will undoubtedly have a significant effect on the functions of the resulting proteins and consequently on the molecular physiology of the biological system in general.

AS and enzymes

AS may have a profound effect on enzymatic genes resulting in the loss or modification of their canonical function [8, 115, 116]. These changes manifest in the alterations of enzyme kinetics, activity, topological location or regulatory mechanisms.

We have analyzed the human proteome from UniProt [85] to explore the distribution of alternatively spliced isoforms, as well as loss or modification of the functional sequence features in different enzymatic classes. As follows from Figure 5, a large number of enzymatic isoforms undergo substantial sequence modifications with loss or replacement of active sites, topological domains, binding sites and other sequence features in all six major classes of enzymes.

These changes may result in modifications of enzyme 3D structure, topology (because of the loss of the transmembrane domains and signal peptides), enzymatic properties (e.g. loss of the active sites) and binding repertoire in comparison with the functions of the known protein isoforms. Please refer to Supplementary Table ST-3 for detailed information on the loss of functional features by enzymatic sequences.

The effect of AS on protein structure

The effect of AS on protein structure was studied by Wang et al. [117]. The authors have demonstrated that alternative exons are predominantly located in coiled regions of secondary structures. The exposed residues, as well as the majority of the sequences involved in splicing, are located on the surface of proteins. This property prevents alternative exons from having a dramatic effect on the general protein architecture, and AS mostly appears to affect surface structures of proteins. Modifications of surface structures of proteins suggest substantial functional alterations resulting from AS. It also underscores the importance of sequence and structural analysis for predicting the functions of the AS isoforms.

The effect of AS on protein interactions

AS emerges as one of the essential mechanisms of regulation of interactions between proteins and their binding partners. Yang et al. [21] studied the global impact of protein isoforms on the functional complexity of the human proteome by cloning full-length open reading frames of alternatively spliced transcripts for a large number of human genes. PPI profiling was used for the functional comparison of hundreds of protein isoform pairs. The study demonstrated a widespread expansion of protein interaction capabilities with the majority of isoform pairs sharing only <50% of their interactions. The authors have arrived at the surprising conclusion that AS protein isoforms behave like distinct functionally divergent proteins rather than minor variants of each other. Interaction partners specific to alternative isoforms were associated with different functional modules and likely to be expressed in a highly tissue-specific manner. Studies by Ellis et al. [97] have provided evidence that regulated alternative exons frequently remodel interactions to establish tissue-dependent networks. The authors observed that the genes whose protein products are involved in a large number of PPIs are significantly enriched with tissue-specific exons. These exons predominantly encode flexible regions of proteins that are likely to form conserved interaction surfaces. The authors also determined that approximately one-third of the analyzed neural-regulated exons affect PPIs. The differential inclusion of these exons stimulated or repressed the interactions with the different partners [97].

Another frequent subject of AS affecting protein interactions is the intrinsically disordered proteins that provide an additional level of flexibility and complexity to the regulatory networks [118]. Disordered regions allow the same polypeptide to carry out various interactions via the use of alternative short linear motifs (SLIMs) with different regulatory consequences. The association of alternatively spliced genes with disordered regions may also provide a mechanism, which preserves protein function by enabling the modification of protein interactions and regulation without the adverse effects of disrupting structural domains [119, 120]. Buljan et al. [121] suggested that differential insertion of the disordered segments can mediate new protein interactions, and consequently the emergence of new cellular functions performed by the protein. The production of these alternative isoforms will lead to the rewiring of the associated interaction networks in different tissues through the recruitment of distinct interaction partners via the alternatively spliced disordered segments. The authors hypothesize that AS of the disordered regions provides a mechanism for tissue-specific signaling and contributes to the emergence of new traits during evolution, development and disease [121, 122].

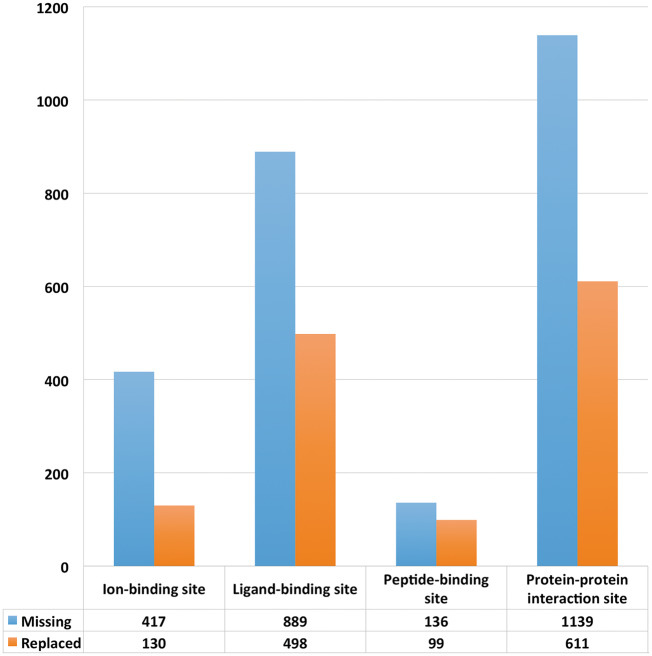

We have performed an analysis of the effect of AS on protein interactions based on the information regarding protein–protein, protein–peptide, protein–ligand and protein–ion interactions information from IBIS [75] and UniProt (Figure 6). Supplementary Table ST-4 provides a detailed account of apparent changes in protein interactions resulting from AS because of the loss of binding sites in comparison with the canonical protein isoforms.

Figure 6.

The effect of AS on protein–protein, protein–peptide, protein–ligand and protein–ion interactions.

As follows from Figure 6, a substantial number of AS isoforms undergo the loss or modification of the binding sites responsible for the interactions with ions, small molecular ligands, peptides and other proteins. Such protein modifications may lead to a significant restructuring of the molecular networks and the emergence of pathways responsible for context-specific variations of cellular behavior, as illustrated with the following example.

AS and molecular networks

The influx of information describing context-specific AS calls for a revision of the known approaches to reconstruction and modeling of biological networks. Thousands of newly described alternatively spliced protein isoforms introduce new contextual patterns of PPI and protein–ligand interaction, networks topology and flux through metabolic pathways [97]. Further characterization of the complete functional repertoire of the human proteome promises to substantially increase the granularity and precision of the networks models describing various environments and physiological conditions.

However, accurate prediction and experimental validation of isoform functions and regulatory mechanisms governing their performance are far from being complete because of the substantial experimental and computational difficulties. Such contextual modeling is contingent on the discovery of global, coordinated ‘splicing programs’ underlying the flexibility of cellular responses in various physiological and pathophysiological conditions. Coordinated changes in expression of alternatively spliced isoforms were observed in multiple models and organisms [104, 105, 107, 123–125]. Along with other posttranscriptional effects, these orchestrated networks ensure the robustness of the system and its responsiveness to environmental stimuli in a context-specific manner [126, 127]. However, the mechanisms that coordinate splicing and the functional integration of the resulting protein isoforms remain enigmatic.

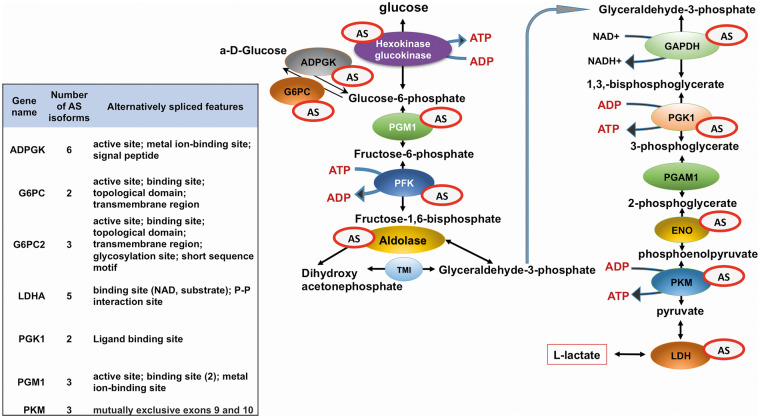

We have analyzed the loss of functional sequence features by the AS protein isoforms involved in known molecular pathways in the KEGG database (see Supplementary File SF-3 for more details). As follows from Figure 7 and Supplementary Table ST-5, canonical isoforms involved in important molecular pathways may undergo significant modifications because of AS. These modifications involve the loss or alteration of functionally important features, such as active and binding sites, topological domains, DNA-binding sites and short sequence motifs (SLIMs). SLIMs are usually involved in PPIs in important biological functions such as pathways involved in cytokine interactions, MAPK cascade and a variety of the metabolic pathways. These changes are likely to result in the rewiring of molecular networks, the expansion of proteomic and regulatory complexity and the emergence of not-yet-discovered molecular pathways.

Figure 7.

Loss of sequence features by AS isoforms involved in cellular pathways. (100% represents all features lost because of AS in all genes associated with the pathway).

The importance of AS for cellular pathways may be illustrated through the example of the glycolytic pathway (Figure 8, Supplementary File SF-4 and Supplementary Table ST-6). Supplementary File SF-4 provides a comprehensive description of the impact of the AS on the glycolytic pathway and describes the experimental studies characterizing the modified functions of the alternatively spliced isoforms of glycolytic enzymes.

Figure 8.

Glycolytic pathway. The enzymes subjected to AS are labeled with ‘AS’. The table on the left represents the numbers of AS isoforms for every glycolytic gene (according to the UniProt data). A number of alternatively spliced glycolytic isoforms were confirmed by proteomics studies. These include glycolytic genes involved in the formation of the 6-phosphofructokinase complex (PFKM, PFKL and PFKP), liver and muscle glucokinase (PKLR, PKM), hexokinases 1 and 4 (GCK, HK1), glycogen synthase (GYS1) and liver and muscle glycogen phosphorylases PYGM and PYGL [128].

The presented examples demonstrate that AS may have a profound effect on the rewiring of molecular networks [97] and in the expansion of proteomic and regulatory complexity. A number of studies [97, 129] have reported that regulated alternative exons often remodel interactions, establishing alternative tissue-dependent networks. See Supplementary Table ST-7 for a representative listing of publications describing the biological effects of AS. In addition, the loss or modification of the enzymatic activity may result in the emergence of multiple context-specific variations of the molecular pathways crucial for the optimization of cellular behavior under ever-changing environmental conditions.

Conclusions and discussion

High-throughput technologies (e.g. RNA-Seq, proteomics) now produce large volumes of data reflecting the isoform content for individual cell types, tissues, developmental stages and physiological conditions. These data present unique opportunities for contextual modeling and calls for a significant revision of all aspects of biological knowledge. The fundamental concepts of a gene, biological function and molecular networks are acquiring additional levels of complexity that reflect the contextual and conditional content of the cellular proteome. The reconstruction of predictive isoform-based models of biological processes will need to accommodate hundreds of thousands of novel molecular functions and regulatory mechanisms operating in a multitude of temporal and spatial contexts. The shift to this new paradigm, however, faces numerous experimental and computational challenges outlined throughout this manuscript. We will summarize some of them below.

Although there was a dramatic increase in a number of publications outlining the role of AS in context-specific processes, a number of articles [130–132] express reservations regarding the major role of AS in cellular protein diversity. Even though the large numbers of alternatively spliced transcripts are identified by the RNA-Seq studies, only a small fraction of annotated alternative isoforms was validated by the proteomics analyses. The authors of these publications argue that according to the proteomics experiments most human genes express a single major protein isoform that tends to be the most evolutionary conserved and the most biologically plausible. Furthermore, the authors suggest that the majority of predicted alternative transcripts may not even be translated into proteins. Undoubtedly, the further development of efficient experimental and computational methods is needed to resolve this fundamental issue.

Another major intellectual shortcoming hampering the development of contextual models of biological processes is the legacy of bioinformatics resources treating a gene as a single entity encoding a particular biological function. Such a view does not factor in the functional diversity of alternatively spliced isoforms and the multitude of functions encoded by a single gene. Models produced under a one-gene-one-function paradigm fail to accurately describe biological processes taking place in various contexts in all their complexity and disregard the majority of the functional potential of the eukaryotic proteome. Experimental determination of isoform function is challenging, and there were only limited efforts to predict isoform function using functional genomics approaches. The development of high-confidence hypotheses regarding potential functions of AS isoforms and subsequent systems-level models using bioinformatics approaches is necessary to drive the experimental contextual biology and substantially reduce the time and resources needed for the determination of isoforms functions.

Proteomic validation

Currently, several public resources have accumulated large volumes of proteomic data relevant to the isoforms. Please refer to the excellent recent surveys of the existing proteomics resources for more information [133, 134]. However, the assessments of isoform existence vary significantly from resource to resource. Reconciling conflicting results between these data sources still awaits consolidation and streamlining [134].

Data structures and ontologies

High-throughput mining of transcriptome data and the support of an isoform-based analysis require the development of data structures and specialized ontologies. These should provide an integrated view of the sequence-based and contextual information describing the source of the biological sample used in the study, the experimental conditions and analytical procedures. Such integrated data structures are not yet supported by the primary sources of isoforms data, in part because of the absence of a standard structured vocabulary. The development of the data framework supporting the isoform-based biology calls for a concerted effort on behalf of the scientific community and major data providers.

Data integration

The need for the integration of various classes of biological information to support the AS isoforms functional predictions was emphasized by a growing number of publications [36, 38]. As it was stated in a recent review by Li et al. [37], current methods for the prediction of isoform functions are often limited by their use of only one data type. The complementarity of different types of genomic, proteomic and functional data (e.g. DNA sequence, RNA-Seq, proteomics and molecular interactions data) would allow increase the accuracy of the predicted models. These models may be significantly improved by factoring in experimental information specific for various temporal and spatial contexts (e.g. tissues or developmental stage). Such integrative proteogenomics approaches will allow gaining a more precise understanding of isoform-level functions and interactions. Availability of these annotations will support reasoning about the potential functional impact of sequence modifications introduced by AS, such as loss, alteration or acquisition of new functions in comparison with the known function of the corresponding canonical isoforms. Such integration will allow to trace and use sequence features and functional annotations provided by multiple data sources and originating from all levels of sequence annotations (from genomic to proteomic).

Prediction of isoform functions

The biggest challenges in the computational prediction of isoform functions lie in the enormous amount of information describing hundreds of thousands of AS protein isoforms that need to be analyzed and accommodated by integrative systems-level models. In a recent review by Li et al. [36], the authors provide a comprehensive overview of a variety of approaches for the prediction of functions of alternatively spliced isoforms based on the utilization of various data types, including DNA sequence, RNA-Seq expression, proteomic data and others.

The assessment of the quality of the predictions of isoforms functions requires a reliable set of functionally annotated isoforms [8]. However, the experimental data available for the validation of such predictions are still insufficient and are often inadequately represented. Moreover, the functions of AS isoforms need to be understood in the framework of coordinated splicing programs recruiting different combinations of exons depending on cellular context and physiological state. Rewiring of the molecular interactions resulting from AS will lead to the context-dependent restructuring of protein complexes and molecular networks. These changes should be understood, experimentally validated and made accessible to the scientific community in a structured annotated form. These efforts will require the development of novel high-throughput experimental and computational approaches enabling isoform-based contextual studies in health and disease. Such contextual studies will deepen our understanding of molecular physiology and offer exciting new opportunities for the development of context-sensitive treatment and diagnostic strategies.

Key Points

Understanding of cellular responses specific to tissue, developmental stage or environmental conditions is essential for the progress of translational biomedicine. One of the central mechanisms underlying the diversity and adaptability of these contextual responses is AS.

This manuscript presents an overview of the global potential impact of AS on the human canonical gene functions, molecular interactions and cellular pathways.

It also provides a survey of the existing approaches and public resources supporting isoform-based biology and challenges facing the isoform-based studies.

Funding

Mr and Mrs Lawrence Hilibrand, the Boler Family Foundation and National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grant number NS050375, in part); the Genetic Basis of Mid-Hindbrain Malformations; National Institute of Mental Health (grant number 1U24MH081810, to C.M.L. (PI), in part). The analysis by P.A. was performed on hardware purchased with Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham internal seed funds.

Supplementary Material

Biographies

Dinanath Sulakhe is an Engagement Manager/Solutions Architect at the Computation Institute, and the Human Genetics Department at the University of Chicago. His interests are in the development of the computational infrastructure and analytical pipelines for high-throughput analysis of translational data.

Mark D’Souza is a Software Developer in the Gilliam’s Lab in the Human Genetics Department at the University of Chicago. He has worked in a variety of fields in bioinformatics and computational biology, including genome analysis, metagenomics and NGS analysis.

Sheng Wang is a Research Scientist at the Bioinformatics group at the Gilliam’s Lab (Human Genetics Department, University of Chicago) with expertise in machine learning, high-throughput genomics and structural biology. Currently, Sheng is on the leave at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, Saudi Arabia.

Sandhya Balasubramanian is a former member of the Gilliam’s Lab (Human Genetics Department, University of Chicago) and currently a Senior Statistical Programmer Analyst at Genentech. Her expertise is in high-throughput translational bioinformatics and systems biology.

Prashanth Athri is an Associate Professor at the Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Amrita School of Engineering, Bengaluru, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, India with a strong interest in translational medicine, proteomics and data mining.

Bingqing Xie is a postdoctoral fellow at the Department of Human Genetics (the University of Chicago) with an expertise in machine learning and translational medicine.

Stefan Canzar is a Group leader at the Gene Center, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, 81377 Munich, Germany. He has an interest and a substantial experience in the fields of data mining, algorithmic computational biology and high-throughput genomics. He has developed a number of machine learning approaches for the analysis of translational data that are widely used by the scientific community.

Gady Agam is an Associate Professor of Computer Science at the Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, Illinois. He has a strong expertise in pattern recognition, machine learning, geometric modeling and advanced data mining.

T. Conrad Gilliam is a Dean for Research and Graduate Education, Biological Sciences Division and Marjorie I. and Bernard A. Mitchell Professor, Department of Human Genetics, the University of Chicago. He is a world renowned expert in the fields of integrative translational medicine with the emphasis on the heritable neuropsychiatric disorders. He leads an effort for the development of the high-throughput computational resources to support systems computational biology.

Natalia Maltsev is a Research Professor at C. Gilliam’s lab at the Department of Human Genetics, University of Chicago. She has a substantial expertise and interest in computational systems biology. She has led the development of a number of computational resources to support high-throughput genomics.

References

- 1. Sambrook J. Adenovirus amazes at Cold Spring Harbor. Nature 1977;268(5616):101–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gilbert W. Why genes in pieces? Nature 1978;271(5645):501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Black DL. Protein diversity from alternative splicing: a challenge for bioinformatics and post-genome biology. Cell 2000;103(3):367–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Irimia M, Blencowe BJ.. Alternative splicing: decoding an expansive regulatory layer. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2012;24(3):323–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Graveley BR. Alternative splicing: increasing diversity in the proteomic world. Trends Genet 2001;17(2):100–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zaghlool A, Ameur A, Cavelier L.. Splicing in the human brain. Int Rev Neurobiol 2014;116:95–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Papasaikas P, Valcárcel J.. The Spliceosome: the ultimate RNA Chaperone and Sculptor. Trends Biochem Sci 2016;41(1):33–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kelemen O, Convertini P, Zhang Z, et al. Function of alternative splicing. Gene 2013;514(1):1–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang Y, Xiao X, Zhang J, et al. A complex network of factors with overlapping affinities represses splicing through intronic elements. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2013;20(1):36–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wahl MC, Will CL, Lührmann R.. The spliceosome: design principles of a dynamic RNP machine. Cell 2009;136(4):701–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kornblihtt AR, Schor IE, Alló M, et al. Alternative splicing: a pivotal step between eukaryotic transcription and translation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2013;14(3):153–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang Y, Liu J, Huang BO, et al. Mechanism of alternative splicing and its regulation. Biomed Rep 2015;3(2):152–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fu XD, Ares M.. Context-dependent control of alternative splicing by RNA-binding proteins. Nat Rev Genet 2014;15(10):689–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sammeth M, Foissac S, Guigó R.. A general definition and nomenclature for alternative splicing events. PLoS Comput Biol 2008;4(8):e1000147.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ezkurdia I, Juan D, Rodriguez JM, et al. Multiple evidence strands suggest that there may be as few as 19, 000 human protein-coding genes. Hum Mol Genet 2014;23(22):5866–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pertea M, Salzberg SL.. Between a chicken and a grape: estimating the number of human genes. Genome Biol 2010;11(5):206.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Frankish A, Uszczynska B, Ritchie GR, et al. Comparison of GENCODE and RefSeq gene annotation and the impact of reference geneset on variant effect prediction. BMC Genomics 2015;16(Suppl 8):S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yates A, Akanni W, Amode MR, et al. Ensembl 2016. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44(D1):D710–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harrow J, Frankish A, Gonzalez JM, et al. GENCODE: the reference human genome annotation for The ENCODE Project. Genome Res 2012;22(9):1760–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hu Z, Scott HS, Qin G, et al. Revealing missing human protein isoforms based on Ab initio prediction, RNA-seq and proteomics. Sci Rep 2015;5(1):10940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang X, Coulombe-Huntington J, Kang S, et al. Widespread expansion of protein interaction capabilities by alternative splicing. Cell 2016;164:805–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Orchard S, Ammari M, Aranda B, et al. The MIntAct project–IntAct as a common curation platform for 11 molecular interaction databases. Nucleic Acids Res 2014;42(D1):D358–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gilson MK, Liu T, Baitaluk M, et al. BindingDB in 2015: a public database for medicinal chemistry, computational chemistry and systems pharmacology. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44(D1):D1045–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hamid FM, Makeyev EV.. Emerging functions of alternative splicing coupled with nonsense-mediated decay. Biochem Soc Trans 2014;42(4):1168–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. de Klerk E, ‘t Hoen PAC.. Alternative mRNA transcription, processing, and translation: insights from RNA sequencing. Trends Genet 2015;31(3):128–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pesole G. What is a gene? An updated operational definition. Gene 2008;417(1–2):1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zambelli F, Pavesi G, Gissi C, et al. Assessment of orthologous splicing isoforms in human and mouse orthologous genes. BMC Genomics 2010;11:534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koonin EV, Csuros M, Rogozin IB.. Whence genes in pieces: reconstruction of the exon-intron gene structures of the last eukaryotic common ancestor and other ancestral eukaryotes. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2013;4(1):93–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kim E, Magen A, Ast G.. Different levels of alternative splicing among eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res 2007;35(1):125–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kondrashov FA, Koonin EV.. Evolution of alternative splicing: deletions, insertions and origin of functional parts of proteins from intron sequences. Trends Genet 2003;19(3):115–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Taneri B, Asilmaz E, Gaasterland T.. Biomedical impact of splicing mutations revealed through exome sequencing. Mol Med 2012;18:314–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lewandowska MA. The missing puzzle piece: splicing mutations. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2013;6(12):2675–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lim KH, Ferraris L, Filloux ME, et al. Using positional distribution to identify splicing elements and predict pre-mRNA processing defects in human genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011;108(27):11093–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Oltean S, Bates DO.. Hallmarks of alternative splicing in cancer. Oncogene 2014;33(46):5311–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li W, Kang S, Liu CC, et al. High-resolution functional annotation of human transcriptome: predicting isoform functions by a novel multiple instance-based label propagation method. Nucleic Acids Res 2014;42(6):e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li HD, Omenn GS, Guan Y.. A proteogenomic approach to understand splice isoform functions through sequence and expression-based computational modeling. Brief Bioinform 2016;17(6):1024–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li W, Liu CC, Kang S, et al. Pushing the annotation of cellular activities to a higher resolution: predicting functions at the isoform level. Methods 2016;93:110–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li HD, Menon R, Omenn GS, et al. The emerging era of genomic data integration for analyzing splice isoform function. Trends Genet 2014;30(8):340–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Eksi R, Li HD, Menon R, et al. Systematically differentiating functions for alternatively spliced isoforms through integrating RNA-seq data. PLoS Comput Biol 2013;9(11):e1003314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hao Y, Colak R, Teyra J, et al. Semi-supervised learning predicts approximately one third of the alternative splicing isoforms as functional proteins. Cell Rep 2015;12(2):183–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li HD, Menon R, Omenn GS, et al. Revisiting the identification of canonical splice isoforms through integration of functional genomics and proteomics evidence. Proteomics 2014;14(23–24):2709–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. O'Leary NA, Wright MW, Brister JR, et al. Reference sequence (RefSeq) database at NCBI: current status, taxonomic expansion, and functional annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44:D733–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Consortium U. UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43(D1):D204–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wilhelm M, Schlegl J, Hahne H, et al. Mass-spectrometry-based draft of the human proteome. Nature 2014;509(7502):582–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015;347(6220):1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Farrah T, Deutsch EW, Hoopmann MR, et al. The state of the human proteome in 2012 as viewed through PeptideAtlas. J Proteome Res 2013;12(1):162–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schaab C, Geiger T, Stoehr G, et al. Analysis of high accuracy, quantitative proteomics data in the MaxQB database. Mol Cell Proteomics 2012;11(3):M111.014068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rodriguez JM, Carro A, Valencia A, et al. APPRIS WebServer and WebServices. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43(W1):W455–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Consortium G. Human genomics. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science 2015;348:648–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Liu X, Yu X, Zack DJ, et al. TiGER: a database for tissue-specific gene expression and regulation. BMC Bioinformatics 2008;9:271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wu C, Jin X, Tsueng G, et al. BioGPS: building your own mash-up of gene annotations and expression profiles. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44(D1):D313–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kim MS, Pinto SM, Getnet D, et al. A draft map of the human proteome. Nature 2014;509(7502):575–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Southan C, Sharman JL, Benson HE, et al. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44(D1):D1054–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bairoch A. The ENZYME database in 2000. Nucleic Acids Res 2000;28(1):304–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Consortium GO. The gene ontology in 2010: extensions and refinements. Nucleic Acids Res 2010;38(Suppl 1):D331–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Taub DD. Cytokine, growth factor, and chemokine ligand database. Curr Protoc Immunol 2004;Chapter 6:Unit 6.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mitchell A, Chang HY, Daugherty L, et al. The InterPro protein families database: the classification resource after 15 years. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43(D1):D213–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wingender E, Schoeps T, Dönitz J.. TFClass: an expandable hierarchical classification of human transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res 2013;41(D1):D165–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Kawashima M, et al. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44(D1):D457–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Croft D, Mundo AF, Haw R, et al. The reactome pathway knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res 2014;42:D472–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Schaefer CF, Anthony K, Krupa S, et al. PID: the pathway interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res 2009;37:D674–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nishimura D. BioCarta. Biotech Software and Internet Report 2001;2(3):117–20. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhang F, Drabier R.. IPAD: the integrated pathway analysis database for systematic enrichment analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2012;13(Suppl 15):S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, et al. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43(D1):D447–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Choi C, Krull M, Kel A, et al. TRANSPATH–a high quality database focused on signal transduction. Comp Funct Genomics 2004;5(2):163–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cerami EG, Gross BE, Demir E, et al. Pathway commons, a web resource for biological pathway data. Nucleic Acids Res 2011;39:D685–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kutmon M, Riutta A, Nunes N, et al. WikiPathways: capturing the full diversity of pathway knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44(D1):D488–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Martelli PL, D'Antonio M, Bonizzoni P, et al. ASPicDB: a database of annotated transcript and protein variants generated by alternative splicing. Nucleic Acids Res 2011;39:D80–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Shionyu M, Yamaguchi A, Shinoda K, et al. AS-ALPS: a database for analyzing the effects of alternative splicing on protein structure, interaction and network in human and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res 2009;37:D305–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wu S, Skolnick J, Zhang Y.. Ab initio modeling of small proteins by iterative TASSER simulations. BMC Biol 2007;5:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Floris M, Raimondo D, Leoni G, et al. MAISTAS: a tool for automatic structural evaluation of alternative splicing products. Bioinformatics 2011;27(12):1625–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Birzele F, Küffner R, Meier F, et al. ProSAS: a database for analyzing alternative splicing in the context of protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res 2007;36:D63–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Källberg M, Wang H, Wang S, et al. Template-based protein structure modeling using the RaptorX web server. Nat Protoc 2012;7(8):1511–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wang S, Li W, Liu S, et al. RaptorX-property: a web server for protein structure property prediction. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44(W1):W430–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Shoemaker BA, Zhang D, Tyagi M, et al. IBIS (Inferred Biomolecular Interaction Server) reports, predicts and integrates multiple types of conserved interactions for proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40(D1):D834–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Keshava Prasad TS, Goel R, Kandasamy K, et al. Human protein reference database–2009 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2009;37:D767–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Licata L, Briganti L, Peluso D, et al. MINT, the molecular interaction database: 2012 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40:D857–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Chatr-Aryamontri A, Breitkreutz BJ, Oughtred R, et al. The BioGRID interaction database: 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43:D470–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Tseng YT, Li W, Chen CH, et al. IIIDB: a database for isoform-isoform interactions and isoform network modules. BMC Genomics 2015;16(Suppl 2):S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Pruitt KD, Brown GR, Hiatt SM, et al. RefSeq: an update on mammalian reference sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 2014;42:D756–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Harrow JL, Steward CA, Frankish A, et al. The vertebrate genome annotation browser 10 years on. Nucleic Acids Res 2014;42:D771–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Heberle H, Meirelles GV, da Silva FR, et al. InteractiVenn: a web-based tool for the analysis of sets through Venn diagrams. BMC Bioinformatics 2015; 16:169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res 2000;28(1):235–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Rodriguez JM, Maietta P, Ezkurdia I, et al. APPRIS: annotation of principal and alternative splice isoforms. Nucleic Acids Res 2013;41:D110–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. UniProt. What is the canonical sequence? Are all isoforms described in one entry? http://www.uniprot.org/help/canonical_and_isoforms (12 December 2016, date last accessed).

- 86. Speir ML, Zweig AS, Rosenbloom KR, et al. The UCSC genome browser database: 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44(D1):D717–25. 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. UCSC Genome Browser. UCSC genes track settings. http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgTrackUi? db=hg19&g=knownGene (12 December, 2016, date last accessed).

- 88. Ensembl. Help—Glossary—Homo sapiens—Ensembl genome browser 87. http://www.ensembl.org/Help/Glossary? id=346 (12 December, 2016, date last accessed).

- 89. Djebali S, Davis CA, Merkel A, et al. Landscape of transcription in human cells. Nature 2012;489(7414):101–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Gonzàlez-Porta M, Frankish A, Rung J, et al. Transcriptome analysis of human tissues and cell lines reveals one dominant transcript per gene. Genome Biol 2013;14(7):R70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Floris M, Orsini M, Thanaraj TA.. Splice-mediated Variants of Proteins (SpliVaP)—data and characterization of changes in signatures among protein isoforms due to alternative splicing. BMC Genomics 2008;9(1):453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Xing Y, Zhao X, Yu T, et al. MiasDB: a database of molecular interactions associated with alternative splicing of human Pre-mRNAs. PLoS One 2016;11(5):e0155443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Cook KB, Kazan H, Zuberi K, et al. RBPDB: a database of RNA-binding specificities. Nucleic Acids Res 2011;39:D301–8. 30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Giulietti M, Piva F, D'Antonio M, et al. SpliceAid-F: a database of human splicing factors and their RNA-binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res 2013;41:D125–31. 1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Giudice G, Sánchez-Cabo F, Torroja C, et al. ATtRACT-a database of RNA-binding proteins and associated motifs. Database 2016;2016:baw035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Will T, Helms V.. PPIXpress: construction of condition-specific protein interaction networks based on transcript expression. Bioinformatics 2016;32(4):571–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Ellis JD, Barrios-Rodiles M, Colak R, et al. Tissue-specific alternative splicing remodels protein-protein interaction networks. Mol Cell 2012;46(6):884–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Black DL, Grabowski PJ.. Alternative pre-mRNA splicing and neuronal function. Prog Mol Subcell Biol 2003;31:187–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Yap K, Makeyev EV.. Regulation of gene expression in mammalian nervous system through alternative pre-mRNA splicing coupled with RNA quality control mechanisms. Mol Cell Neurosci 2013;56:420–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Marijuán PC, del Moral R, Navarro J.. On eukaryotic intelligence: signaling system's guidance in the evolution of multicellular organization. Biosystems 2013;114(1):8–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Naftelberg S, Schor IE, Ast G, et al. Regulation of alternative splicing through coupling with transcription and chromatin structure. Annu Rev Biochem 2015;84:165–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Zhou HL, Luo G, Wise JA, et al. Regulation of alternative splicing by local histone modifications: potential roles for RNA-guided mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res 2014;42(2):701–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Carrillo Oesterreich F, Bieberstein N, Neugebauer KM.. Pause locally, splice globally. Trends Cell Biol 2011;21(6):328–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Singh RK, Xia Z, Bland CS, et al. Rbfox2-coordinated alternative splicing of Mef2d and Rock2 controls myoblast fusion during myogenesis. Mol Cell 2014;55(4):592–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Gao Z, Godbout R.. Reelin-Disabled-1 signaling in neuronal migration: splicing takes the stage. Cell Mol Life Sci 2013;70(13):2319–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Johnson MB, Kawasawa YI, Mason CE, et al. Functional and evolutionary insights into human brain development through global transcriptome analysis. Neuron 2009;62(4):494–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Bland CS, Wang ET, Vu A, et al. Global regulation of alternative splicing during myogenic differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res 2010;38(21):7651–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Yamamoto ML, Clark TA, Gee SL, et al. Alternative pre-mRNA splicing switches modulate gene expression in late erythropoiesis. Blood 2009;113(14):3363–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Cieply B, Carstens RP.. Functional roles of alternative splicing factors in human disease. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2015;6(3):311–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Santos A, Tsafou K, Stolte C, et al. Comprehensive comparison of large-scale tissue expression datasets. PeerJ 2015;3:e1054.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Kogenaru S, del Val C, Hotz-Wagenblatt A, et al. TissueDistributionDBs: a repository of organism-specific tissue-distribution profiles. Theor Chem Acc 2010;125(3–6):651–8. [Google Scholar]

- 112. Yang X, Ye Y, Wang G, et al. VeryGene: linking tissue-specific genes to diseases, drugs, and beyond for knowledge discovery. Physiol Genomics 2011;43(8):457–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Kapushesky M, Emam I, Holloway E, et al. Gene expression atlas at the European bioinformatics institute. Nucleic Acids Res 2010;38:D690–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Breuza L, Poux S, Estreicher A, et al. The UniProtKB guide to the human proteome. Database 2016;2016:bav120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Dolzhanskaya N, Merz G, Denman RB.. Alternative splicing modulates protein arginine methyltransferase-dependent methylation of fragile X syndrome mental retardation protein. Biochemistry 2006;45(34):10385–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Ghosh M, Loper R, Gelb MH, et al. Identification of the expressed form of human cytosolic phospholipase A2beta (cPLA2beta): cPLA2beta3 is a novel variant localized to mitochondria and early endosomes. J Biol Chem 2006;281(24):16615–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Wang P, Yan B, Guo JT, et al. Structural genomics analysis of alternative splicing and application to isoform structure modeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102(52):18920–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Uversky VN. Dancing protein clouds: the strange biology and chaotic physics of intrinsically disordered proteins. J Biol Chem 2016;291(13):6681–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Romero PR, Zaidi S, Fang YY, et al. Alternative splicing in concert with protein intrinsic disorder enables increased functional diversity in multicellular organisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103(22):8390–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Light S, Elofsson A.. The impact of splicing on protein domain architecture. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2013;23(3):451–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]