Abstract

Background

High demand for health services is an issue of current importance in England, in part because of the rapidly increasing use of emergency departments (EDs) and GP practices for mental health conditions and the high cost of these services.

Aim

To examine the social determinants of health service use in people with mental health issues.

Design and setting

Twenty-eight neighbourhoods, each with a population of 5000–10 000 people, in the north west coast of England with differing levels of deprivation.

Method

A comprehensive public health survey was conducted, comprising questions on housing, physical health, mental health, lifestyle, social issues, environment, work, and finances. Poisson regression models assessed the effect of mental health comorbidity, mental and physical health comorbidity, and individual mental health symptoms on ED and general practice attendances, adjusting for relevant socioeconomic and lifestyle factors.

Results

Participants who had both a physical and mental health condition reported attending the ED (rate ratio [RR] = 4.63, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.86 to 7.51) and general practice (RR = 3.82, 95% CI = 3.16 to 4.62) more frequently than all other groups. Having a higher number of mental health condition symptoms was associated with higher general practice and ED service use. Depression was the only mental health condition symptom that was significantly associated with ED attendance (RR = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.05 to 1.90), and anxiety was the only symptom significantly associated with GP attendance (RR = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.03 to 1.38).

Conclusion

Mental health comorbidities increase the risk of attendances to both EDs and general practice. Further research into the social attributes that contribute to reduced ED and general practice attendance rates is needed.

Keywords: emergency departments, mental health, primary care, service use, social care

INTRODUCTION

The UK has the second-highest levels of economic inequality in the European Union.1 High demand for emergency admissions is an issue of pressing importance in England because of rapidly increasing use of the emergency department (ED) for mental health conditions and the high cost of these services.2 The current ED ‘crisis’ in England is linked to health inequality, as people living in more deprived areas use NHS services substantially more than people living in less deprived areas.3–6 Patients living in more deprived areas also appear to attend EDs for less serious conditions,4,6,7 and present at the ED nearly 2.5 times more than those in the least deprived areas for preventable emergency hospitalisations,4 while patients with mental health conditions, substance misuse, and/or long-term health conditions are most likely to attend EDs,5,6 and are at risk of repeated hospital admissions.7,8 In 2017, the number of people going to the ED for mental ill health had risen by nearly half since 2011–2012.9

In primary care, patients consult GPs on average three times a year.10 Frequent attenders have been shown to have higher rates of common mental health conditions11 including depression,12,13 anxiety,14 and somatic disorders.15–17 Consultation rates have been shown to be higher for those in the most deprived quintile compared with those in the least deprived quintile.10 Asaria et al 3 found that while increasing accessibility to GPs in deprived areas reduced socioeconomic inequalities in primary care access, it only resulted in modest reductions in ED use.

More knowledge is needed about the determinants of ED and primary care service use for people with mental health conditions and how this compares across areas of differing levels of deprivation. Moreover, it is important to consider lifestyle, socioeconomic, and accessibility factors when identifying determinants as these may underpin relationships between mental health and service use. Because of the disparities that exist in the way that people use health services, potential gains may be made by addressing health inequalities, particularly for people with mental health conditions. To coordinate care effectively in a given area, up-to-date information about local healthcare use for mental health conditions is required. This study used data collected by the National Institute of Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care North West Coast (NIHR CLAHRC NWC) Household Health Survey (HHS) to explore self-reported service use in regions of the north west coast of England, and to examine patient characteristics that predict attendance at EDs and general practice surgeries.

How this fits in

| The current emergency department (ED) ‘crisis’ in England has been linked to health inequality as a result of people living in more deprived areas using NHS services more frequently than those living in less deprived areas. Patients with mental health problems are at greater risk of repeated hospital admissions and increased number of attendances to general practices when adjusting for socioeconomic status. The National Institute of Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care North West Coast Household Health Survey provides information on the rate of use of services in regions of the north west coast of England. Mental health comorbidities increase the risk of attendances to both EDs and general practices. Depression predicts higher ED attendance and anxiety predicts higher general practice attendance when adjusting for physical health and socioeconomic status. |

The specific aims of the study were to assess the relationship between mental health, ED, and primary care attendance; quantify the extent to which comorbidities relate to service use; identify individual mental health condition symptoms that predict service use; and assess the relationship between Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score and GP and ED attendance.

METHOD

Participants and design

The NIHR CLAHRC NWC HHS is a comprehensive quantitative public health survey co-produced with public and patient advisers, local authorities, NHS clinicians, and university partners. Twenty-eight neighbourhoods were surveyed using random probability sampling across the north west coast of England, targeting 20 neighbourhoods of high deprivation, identified by local authority partners, and eight less deprived areas to serve as comparison neighbourhoods. Each neighbourhood had a population of 5000–10 000 people and most areas were defined by electoral ward boundaries. The survey assessed demographic, socioeconomic, physical health, mental health, and lifestyle factors. A subset of these variables was selected for the present analysis.

Research teams conducted face-to-face interviews and recorded responses on tablets. Interviews were conducted between August 2015 and January 2016. Interview teams worked at varying times of the day to ensure the sample was representative. This resulted in 55% (n = 2375) of interviews being conducted on weekends or after 4.00 pm on weekdays, and 45% (n = 1944) of interviews conducted before 4.00 pm on weekdays. Participants were reimbursed with a 10 GBP voucher in return for their participation. A detailed description of the sampling procedure is available elsewhere.18

Measures

The study outcome variable was defined as the number of times responders reported attending an ED or their GP over the previous 12 months. Measures of socioeconomic conditions included education, employment, financial hardship, change in financial circumstances, and housing quality. Physical health was assessed with the four physical health dimensions of the EuroQol five-dimension scale (EQ-5D-5L):19 mobility, self-care, engagement in usual activities, and pain. Mental and physical health comorbidity was assessed by asking participants to indicate whether they had any physical or mental health conditions (Yes/No), and, if they responded ‘Yes’, to indicate which condition(s) they had from a list of physical and mental health conditions.

Four mental health condition symptoms (depression, anxiety, paranoia, and hallucinations) were assessed using a series of validated instruments. Depression was measured using the 9-item patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9).20 Anxiety was measured using the 7-item generalised anxiety disorder scale (GAD-7).21 Paranoia was measured using the persecution subscale of the persecution and deservedness scale (PaDS-5) for symptoms of paranoia.22,23 Auditory verbal hallucinations (AVH) were assessed using a single item from the Launay–Slade hallucination scale: ‘I have been troubled by hearing voices in my head.’24 When comparing severe with non-severe symptoms, the published clinical cut-offs were used for severe symptoms of depression (>14 on the PHQ-9)20 and anxiety (>14 on GAD-7).21 There are no validated clinical cut-offs for the PaDS-5 paranoia scale,23 so participants were categorised as severe if they scored above the midpoint. Participants were categorised as experiencing severe AVH if they agreed or strongly agreed with the AVH item.24 Mental health comorbidity was calculated by summing the number of conditions where someone met the severe criterion.

Alcohol consumption was measured by participants indicating if they ever drank alcohol, and, if so, how many alcoholic drinks (which were converted to alcohol units dependent on type of alcohol) they had consumed over the past 7 days.25 Practical social support and social contact were assessed based on the level of agreement with the statements ‘If I needed help, there are people who would be there for me’ and ‘If I wanted company or to socialise, there are people I can call on’ (see Supplementary Table 1 for more details on each of the survey variables).

An IMD score was also entered for each participant based on their lower-level super output area (LSOA). The IMD score is calculated based on indices of deprivation across seven domains: income, employment, education, health and disability, crime, housing, and living environment. Access to GP and EDs was assessed with a distance measure (km) calculated using the Routino open source tool.26 The shortest road distance was calculated between the centre of each postcode in the sampled area and each health facility.27 The average distance to GP clinics and EDs for all LSOAs was then calculated and linked to the LSOA of each participant’s residence.

Preliminary analyses and data preparation

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were calculated between mental health condition symptoms and healthcare service use (Supplementary Table 2). Listwise deletion was employed to account for missing values in all analyses. The level of missing data was very low at <5% for all variables.

For the regression analyses predicting ED and GP attendance, Poisson regression models were constructed that controlled for potential demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle, health, and healthcare access confounders. Rate ratios (RR) were calculated for each variable, and standard errors were adjusted to account for the multistage nature of the sampling procedure. The model was also weight adjusted to account for demographic variation in non-response.

RESULTS

In total, 4319 participants were recruited via door knocking, with a response rate of 61% (n = 2635). The sample comprised 1854 (43%) males and 2465 (57%) females whose ages ranged from 18 to 95 years (mean = 49.12, standard deviation [SD] = 19.13).

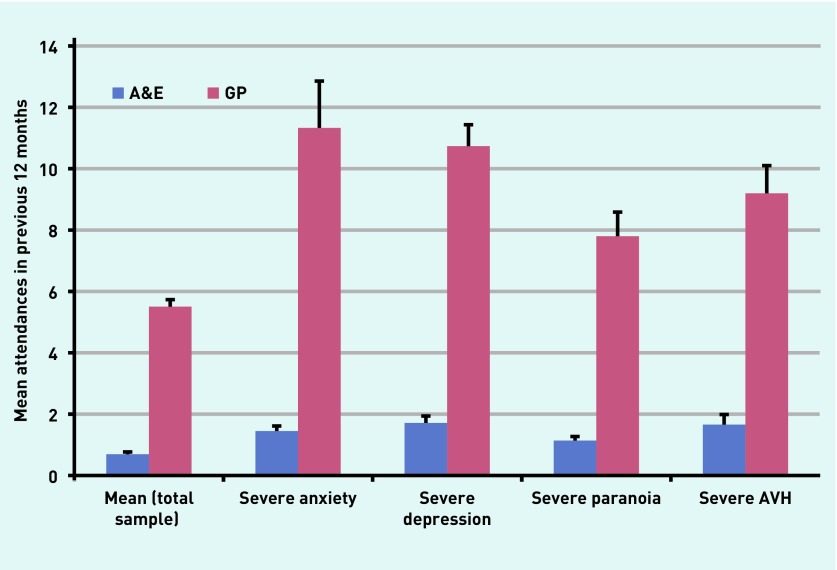

On average, participants had attended EDs 0.69 (SD = 2.74) times and a GP 5.5 (SD = 15.05) times in the previous 12 months. Figure 1 shows the mean levels of attendances for GP and ED services among participants classified as having severe mental health symptoms alongside the total sample mean.

Figure 1.

Reported emergency department and GP use among people with severe mental health symptoms and for total sample. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. People could fall into multiple categories if they met the criteria for multiple symptoms. A&E = accident and emergency department. AVH = auditory verbal hallucinations.

Relationship between physical and mental health comorbidity and service use

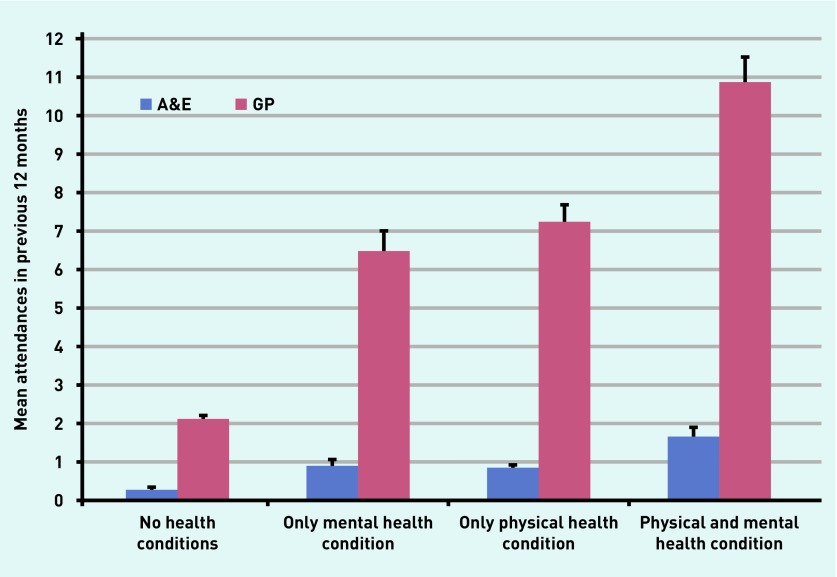

Figure 2 shows mean ED and GP attendances in people with physical and mental health comorbidity. Results of the Poisson regression analysis showed that comorbidity significantly predicted greater ED and GP attendance over the previous 12 months. Specifically, relative to having no health conditions, having only a mental health condition was associated with a 2.1 times higher rate of ED attendance (RR = 2.10, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.33 to 3.31) and 2.5 times higher rate of GP attendance (RR = 2.49, 95% CI = 2.03 to 3.04). Having only a physical health condition was associated with a 2.6 times higher rate of ED attendance (RR = 2.64, 95% CI = 1.78 to 3.95) and a 2.4 times higher rate of GP attendance (RR = 2.43, 95% CI = 2.10 to 2.81). Reporting at least one physical health condition and at least one mental health condition was associated with a 4.6 times higher rate of ED attendance (RR = 4.63, 95% CI = 2.86 to 7.51) and 3.8 times higher rate of GP attendance (RR = 3.82, 95% CI = 3.16 to 4.62). Deprivation did not predict service usage for EDs (RR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.99 to 1.01) or GPs (RR = 1.00, 95% CI = 1.00 to 1.01). Details of the coefficients for the full model are reported in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Reported relationship between physical and mental health comorbidity and service use for total sample. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. A&E = accident and emergency department.

Table 1.

Poisson regression model of physical and mental health comorbidity predicting emergency department and GP attendance, adjusted for demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle, healthcare access, and physical health factors

| Socioeconomic factors | A&E attendance, adjusted RR | 95% CI | GP attendance, adjusted RR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidity | ||||

| No conditions (Ref) | ||||

| Mental health condition(s) | 2.10a | 1.33 to 3.31 | 2.49b | 2.03 to 3.04 |

| Physical health condition(s) | 2.64b | 1.77 to 3.95 | 2.43b | 2.10 to 2.81 |

| Physical and mental health condition(s) | 4.63b | 2.86 to 7.51 | 3.82b | 3.16 to 4.62 |

|

| ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (≥65), years (Ref) | ||||

| 18–24 | 2.31c | 1.21 to 4.42 | 0.68a | 0.54 to 0.86 |

| 25–44 | 1.26 | 0.83 to 1.90 | 0.77c | 0.62 to 0.96 |

| 45–64 | 1.28 | 0.87 to 1.89 | 0.81c | 0.67 to 0.98 |

| Sex (female) | 0.99 | 0.74 to 1.31 | 1.14 | 0.99 to 1.31 |

| Ethnicity (BME) | 0.49a | 0.31 to 0.80 | 0.84c | 0.71 to 0.99 |

|

| ||||

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Education (no qualifications) (Ref) | ||||

| Professional, vocational, or work certificate | 1.30 | 0.97 to 1.76 | 1.01 | 0.89 to 1.16 |

| Degree or higher | 1.21 | 0.72 to 2.04 | 0.86 | 0.74 to 1.00 |

| Non-employment | 1.84b | 1.39 to 2.43 | 1.41b | 1.24 to 1.59 |

| Problems with housing | 1.48a | 1.13 to 1.96 | 1.10 | 0.92 to 1.31 |

| Index of Multiple Deprivation | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.01 |

|

| ||||

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| None (0 units) (Ref) | ||||

| Moderate (<14 units) | 0.94 | 0.69 to 1.28 | 0.81a | 0.70 to 0.94 |

| Heavy (14–28 units) | 0.71 | 0.49 to 1.05 | 0.78a | 0.65 to 0.92 |

| Very heavy (>28 units) | 0.79 | 0.42 to 1.48 | 1.09 | 0.80 to 1.48 |

|

| ||||

| Healthcare access | ||||

| Distance to GP | 1.31 | 0.99 to 1.74 | 1.08 | 0.87 to 1.35 |

| Distance to emergency department | 0.92b | 0.88 to 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.96 to 1.02 |

P<0.05.

P<0.01.

P<0.001. A&E = accident and emergency department. BME = black and minority ethnic. RR = rate ratio.

Relationship between mental health comorbidity and service use

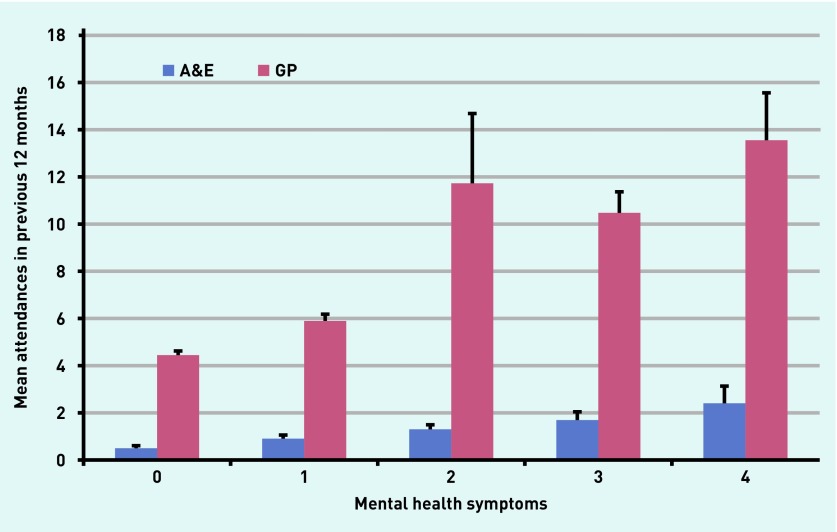

Mental health comorbidity was defined as the numbers of mental health condition symptoms for which the participant met the ‘severe’ criteria, as defined earlier. Separate models were constructed for each health service. Mean attendances for each level of comorbidity are shown in Figure 3. Models including coefficients for all variables are provided in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Health service use according to number of severe mental health symptoms. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. A&E = accident and emergency department.

Table 2.

Poisson regression model of mental health comorbidity predicting emergency department and GP attendance, adjusted for demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle, healthcare access, and physical health factors

| Predictors | A&E attendance, adjusted RR | 95% CI | GP attendance, adjusted RR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health comorbidity | ||||

| 0 severe symptoms (Ref) | ||||

| 1 severe symptom | 1.22 | 0.91 to 1.62 | 1.15a | 1.01 to 1.32 |

| 2 severe symptoms | 1.06 | 0.69 to 1.63 | 1.92b | 1.31 to 2.82 |

| 3 severe symptoms | 1.48 | 0.85 to 2.59 | 1.51c | 1.23 to 1.87 |

| ≥4 severe symptoms | 2.54b | 1.43 to 4.52 | 2.19c | 1.50 to 3.20 |

|

| ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (≥65), years (Ref) | ||||

| 18–24 | 2.66b | 1.38 to 5.15 | 0.65c | 0.52 to 0.82 |

| 25–44 | 1.35 | 0.92 to 1.99 | 0.77a | 0.61 to 0.97 |

| 45–64 | 1.29 | 0.88 to 1.89 | 0.78a | 0.62 to 0.97 |

| Sex (female) | 1.06 | 0.81 to 1.38 | 1.17a | 1.03 to 1.33 |

| Ethnicity (BME) | 0.59a | 0.37 to 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.74 to 1.06 |

|

| ||||

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Education (no qualifications) (Ref) | ||||

| Professional, vocational, or work certificate | 1.51b | 1.14 to 2.00 | 1.11 | 0.98 to 1.26 |

| Degree or higher | 1.55 | 0.92 to 2.61 | 0.99 | 0.86 to 1.15 |

| Non-employment | 1.52b | 1.13 to 2.03 | 1.25b | 1.08 to 1.44 |

| Problems with housing | 1.32a | 1.04 to 1.68 | 1.00 | 0.85 to 1.17 |

| Index of Multiple Deprivation | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.01 |

|

| ||||

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| None (0 units) (Ref) | ||||

| Moderate (<14 units) | 1.05 | 0.79 to 1.38 | 0.87 | 0.75 to 1.01 |

| Heavy (14–28 units) | 0.83 | 0.57 to 1.21 | 0.86 | 0.73 to 1.00 |

| Very heavy (>28 units) | 0.97 | 0.53 to 1.76 | 1.21 | 0.92 to 1.58 |

|

| ||||

| Healthcare access | ||||

| Distance to GP | 1.31a | 1.01 to 1.70 | 1.06 | 0.87 to 1.29 |

| Distance to emergency department | 0.93c | 0.90 to 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.96 to 1.02 |

|

| ||||

| Problems with physical health (EQ-5D) | ||||

| Mobility | 1.25 | 0.88 to 1.76 | 1.15 | 0.87 to 1.50 |

| Self-care | 2.53c | 1.77 to 3.62 | 1.52c | 1.20 to 1.92 |

| Usual activities | 1.57b | 1.13 to 2.20 | 1.37b | 1.09 to 1.73 |

| Pain | 1.39a | 1.03 to 1.87 | 1.55c | 1.31 to 1.83 |

P<0.05.

P<0.01.

P<0.001. A&E = accident and emergency department. BME = black and minority ethnic. EQ-5D = EuroQol five-dimension scale. RR = rate ratio.

Mental health comorbidity was associated with higher ED attendance for participants with four or more severe symptoms. Specifically, participants with four severe symptoms were 2.5 times more likely to attend the ED (RR = 2.54, 95% CI = 1.43 to 4.52) compared with participants with no severe symptoms. For GP use, having one (RR = 1.15, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.32), two (RR = 1.92, 95% CI = 1.31 to 2.82), three (RR = 1.51, 95% CI = 1.23 to 1.87), or four (RR = 2.19, 95% CI = 1.50 to 3.20) severe symptoms was associated with elevated rates of GP attendance relevant to having no severe symptoms. Deprivation did not predict service usage for EDs (RR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.99 to 1.00) or GPs (RR = 1.00, 95% CI = 1.00 to 1.01).

Mental health condition symptoms as predictors of ED and GP attendance

Depression was the only mental health condition symptom that was significantly associated with ED attendance (RR = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.05 to 1.90) and anxiety was the only symptom significantly associated with GP attendance (RR = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.03 to 1.38) while controlling for health, socioeconomic status, alcohol consumption, and healthcare access variables (Table 3).

Table 3.

Poisson regression model of individual mental health symptoms predicting emergency department and GP attendance, adjusted for demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle, healthcare access, and physical health factors.

| Predictors | A&E attendance, adjusted RR | 95% CI | GP attendance adjusted RR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health symptoms | ||||

| Depression | 1.41a | 1.05 to 1.90 | 1.15 | 0.91 to 1.46 |

| Anxiety | 0.9 | 0.69 to 1.17 | 1.19a | 1.03 to 1.38 |

| Paranoia | 1.02 | 0.86 to 1.21 | 1.04 | 0.88 to 1.23 |

| AVH | 1.05 | 0.88 to 1.25 | 0.97 | 0.87 to 1.08 |

|

| ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (≥65), years (Ref) | ||||

| 18–24 | 2.58b | 1.29 to 5.16 | 0.65c | 0.53 to 0.81 |

| 25–44 | 1.33 | 0.89 to 2.00 | 0.75b | 0.60 to 0.93 |

| 45–64 | 1.26 | 0.83 to 1.89 | 0.78a | 0.63 to 0.97 |

| Sex (female) | 1.04 | 0.79 to 1.36 | 1.15a | 1.01 to 1.31 |

| Ethnicity (BME) | 0.59a | 0.36 to 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.79 to 1.11 |

|

| ||||

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Education (no qualifications) (Ref) | ||||

| Professional, vocational, or work certificate | 1.49b | 1.13 to 1.95 | 1.05 | 0.94 to 1.17 |

| Degree or higher | 1.54 | 0.91 to 2.62 | 0.93 | 0.81 to 1.08 |

| Non-employment | 1.55b | 1.14 to 2.10 | 1.22a | 1.05 to 1.41 |

| Problems with housing | 1.30a | 1.01 to 1.69 | 0.95 | 0.81 to 1.13 |

| Index of Multiple Deprivation | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.01 |

|

| ||||

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| None (0 units) (Ref) | ||||

| Moderate (<14 units) | 1.03 | 0.77 to 1.37 | 0.88 | 0.77 to 1.02 |

| Heavy (14–28 units) | 0.83 | 0.57 to 1.21 | 0.88 | 0.75 to 1.02 |

| Very heavy (>28 units) | 0.98 | 0.54 to 1.78 | 1.24 | 1.00 to 1.64 |

|

| ||||

| Healthcare access | ||||

| Distance to GP | 1.31a | 1.01 to 1.69 | 1.09 | 0.88 to 1.34 |

| Distance to emergency department | 0.93c | 0.89 to 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.96 to 1.02 |

|

| ||||

| Problems with physical health (EQ-5D) | ||||

| Mobility | 1.26 | 0.89 to 1.79 | 1.14 | 0.87 to 1.50 |

| Self-care | 2.49c | 1.72 to 3.61 | 1.42b | 1.10 to 1.82 |

| Usual activities | 1.47a | 1.04 to 2.08 | 1.33a | 1.05 to 1.70 |

| Pain | 1.37a | 1.00 to 1.87 | 1.52c | 1.29 to 1.78 |

P<0.05.

P<0.01.

P<0.001. A&E = accident and emergency department. AVH = auditory verbal hallucinations. BME = black and minority ethnic. EQ-5D = EuroQol five-dimension scale. RR = rate ratio.

DISCUSSION

Summary

When controlling for a range of potential confounders, physical and mental health comorbidity was an important risk factor for ED and primary care attendance, as was mental health comorbidity alone. Specifically, having both a physical and mental health condition was associated with a more than threefold increase in GP attendance and a more than fourfold increase in ED attendance (Figure 2). Rates of ED attendance more than doubled when participants had four severe mental health condition symptoms; however, GP attendance rates were significantly elevated with any number of severe mental health condition symptoms compared with having no severe symptoms (Figure 3). When examining individual symptoms, depression was found to be associated with more ED attendances, while anxiety was associated with greater GP attendance (Table 3). Along with health status, being aged 18–24 years, from a white ethnic background, and living closer to an ED predicted greater ED attendance in all analyses (Table 3).

Strengths and limitations

This study contributes to the knowledge that patients with comorbid health conditions visit both EDs and GPs more than patients with a single condition. The finding that distance to services predicted service use even when controlling for other potential confounders also supports this assertion. Previous research suggests that a large proportion of attendances at EDs are avoidable,28 and patients with mental health conditions were identified as one of the main groups contributing to increasing demand in EDs.29

A strength of using self-reported survey data is the reliability and accuracy of the information provided.30 A review conducted by Leggett et al 31 about self-reported questionnaires on resource use showed good agreement with administrative data, such as electronic records, although visits to GPs, outpatient days, and nurse visits had poorer agreement. Overall, self-reported questionnaires were concluded to be a valid method of collecting data on healthcare resource use; however, there is an issue of recall bias, particularly after a significant length of time.30

Although the survey collected data from a wide geographical area from relatively disadvantaged and advantaged areas thereby increasing its representativeness, some limitations need to be considered. Considering the focus on people living in disadvantaged neighbourhoods, data are limited to those with a fixed address. Thus, the survey was not able to capture the most disadvantaged groups in the population, such as people who are homeless and unregistered migrants.

This study used data from the north west coast of England, which limits generalisability to other regions and populations. Although the causal directions proposed here seem the most plausible, because of the cross-sectional design, it is not possible to rule out the possibility that contact with services may in some instances worsen people’s mental or physical health.

Comparison with existing literature

Contrary to previous research,3–6,10 there was no association with deprivation and service usage for both EDs and GPs. Being younger and not in employment were the main significant socioeconomic or demographic risk factors for ED attendance in this sample, as has been found in previous studies.5,27 Having problems with self-care, usual daily activities, and pain were all significant physical health predictors (Tables 2 and 3). As previously reported,32 living closer to an ED was associated with more ED attendances but distance to the GP was not associated with ED attendance in non-depressed people.

Contrary to previous research,10 the present study reported higher consultation rates (5.5 versus 3.8) per year. The present study confirms that people with anxiety visit GPs more frequently. The association between anxiety and use of GP services may be due to acute exacerbations of anxiety becoming intolerable so that patients turn to GPs as their first point of support. This is in contrast with severe depression, which is associated with becoming withdrawn from society, particularly for males.33 Alternatively, severe depression may be viewed as a more urgent concern by carers and relatives because of concerns about the imminent risk of self-harm, which in turn may lead to ED visits.34 Another reason for people with anxiety visiting the GP could be mistaking the feeling of acute anxiety for other physical health symptoms35 prompting increased GP visits where patients are likely to be seen quicker and by doctors they know, therefore reducing further anxiety brought on by the uncertainty of the length of wait and social interaction.

Additionally, age, ethnicity, unemployment, and vocational or professional qualifications were associated with ED attendance. Previously, ethnicity was shown to be a significant factor for higher ED attendance in black minority groups compared with white majority groups;5 but, in the present study, there were significantly more participants from white backgrounds attending the ED. Although a previous study has shown that people from white backgrounds used EDs more than those from non-white backgrounds,36 the study was based on relatively small geographical areas with high proportions of particular non-white ethnic groups and therefore with limited generalisability to other areas of the UK. Most participants (89%, n = 3844) indicated that they were of white European ethnic background. Compared with census data for the north west of England, the sample was biased towards female (study sample: 57% versus census: 51%) and black and minority ethnic (study sample: 11% versus census: 8%) participants.37

Participants with only a physical health condition attended EDs more frequently in the previous 12 months than participants with only a mental health condition (2.6 versus 2.1 times higher rate) (Table 1). Participants who had both a physical and mental health condition attended EDs and primary care more frequently than all other groups (4.6 times higher rate). Comorbid mental health condition symptoms were also associated with greater use of both healthcare services (Table 2); however, participants with ≥4 severe mental health condition symptoms, and therefore the most complex needs, attended EDs more frequently than participants with ≤3 severe mental health condition symptoms. Conversely, having any number of mental health condition symptoms increased participant’s rate of GP attendance relative to having no severe symptoms. These results are consistent with previous studies that have reported high levels of ED and GP attendance for mental health condition patients with depression and anxiety in the year before suicide;34,38 however, further research is needed to examine reasons for service use to understand why comorbidity might differentially influence ED and GP attendance rates.

Implications for research and practice

Further work is needed to discover whether other available services for severe depression will reduce the number of patients attending EDs through a proactive approach to managing patients, particularly in disadvantaged groups and areas with a high prevalence of comorbid health conditions. Raising public awareness of the alternatives to EDs for patients with severe depression, particularly in more deprived areas, may reduce the number of attendances; however, alternatives need to be accessible.

The findings of the current study suggest that more expertise is needed in EDs and GP practices for severe depression. Providing access to relevant and effective care, such as delivering brief psychological therapies following an ED attendance, may reduce readmissions to hospital; however, the important social issues such as debt, housing conditions, and unemployment cannot be resolved by medical practitioners. The presence of senior doctors (experts) within EDs could help to better recognise other issues that are affecting a person’s mental health. A National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on coexisting severe mental illness and substance misuse39 suggests that in-house solutions could include moving some GP services to within accident and emergency departments, having senior doctors at the front door of the ED, bringing specialist staff closer to the front door, and improved mental health liaison teams. However, to date, there is no evidence to suggest that any of these interventions would improve referral pathways and therefore reduce the number of ED attendances. Larger and specifically designed studies are needed to address some of these questions. Future interventions to improve access to primary care may be most effectively targeted towards younger adults, given the increase in attendances among 18–24-year-olds. In 2015–2016, those aged 20–24 years were most likely to attend at an ED than all other age brackets in England.40

These findings validate the recommended 2016 NICE guidance, which includes a focus on comorbidity and aims to provide a range of coordinated services that address people’s wider health and social care needs, such as poor housing.39 While not the focus of the present study, the findings highlight that further research is needed into the social determinants of service use. The association between higher attendance rates and poorer housing, for example, could be attributed to the condition of social housing and how this impacts on mental health or exacerbates long-term physical health conditions.27

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to dedicate this paper to their co-author Liz Fuller, something she was immensely proud of. Tragically she passed away suddenly after this paper was accepted for publication, and did not live to see it in print. The authors thank the NIHR CLAHRC NWC public advisers Christopher Whittle and Farheen Yameen, and Mersey Care NHS Trust clinicians Dr Niall Campbell and Dr Cecil Kullu who contributed at the meetings for this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership and Health Research and Care North West Coast (NIHR CLAHRC NWC). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Ethical approval

The research was approved by the University of Liverpool Committee on Research Ethics (Ref: RETH00836 and IPHS-1516-SMC-192). Participants provided informed consent before completing the study.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Income inequality. 2019. https://data.oecd.org/inequality/income-inequality.htm (accessed 27 Nov 2019)

- 2.NHS Digital Accident and emergency attendances in England — 2011–12, experimental statistics. 2013. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/hospital-accident--emergency-activity/2011-12 (accessed 27 Nov 2019)

- 3.Asaria M, Ali S, Doran T, et al. How a universal health system reduces inequalities: lessons from England. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70(7):637–643. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-206742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cookson R, Asaria M, Ali S, et al. Health equity indicators for the English NHS: a longitudinal whole-population study at the small-area level. Health Services and Delivery Research. 2016;4(26):1–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scantlebury R, Rowlands G, Durbaba S, et al. Socioeconomic deprivation and accident and emergency attendances: cross-sectional analysis of general practices in England. Br J Gen Pract. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.McCormick B, Hill PS, Poteliakoff E. Are hospital services used differently in deprived areas? Evidence to identify commissioning challenges. 2012 https://www.chseo.org.uk/downloads/wp2-hospitalservices-deprivedareas.pdf (accessed 27 Nov 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryce A. Inequalities, health and the accident & emergency response. 2010. http://www.equalitiesinhealth.org/public_html/documents/AEFinalReportwrefs23march2011.pdf (accessed 27 Nov 2019)

- 8.Purdy S. Avoiding hospital admissions: what does the research evidence say? 2010. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/avoiding_hospital.html (accessed 27 Nov 2019)

- 9.Mental Health Today Number of people going to A&E for mental health problems climbs by 50%. 2017. https://www.mentalhealthtoday.co.uk/number-of-people-going-to-ae-for-mental-health-problems-climbs-by-50 (accessed 27 Nov 2019)

- 10.Hobbs FDR, Bankhead C, Mukhtar T, et al. Clinical workload in UK primary care: a retrospective analysis of 100 million consultations in England, 2007–14. Lancet. 2016;387(10035):2323–2330. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00620-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norton J, Engberink AO, Gandubert C, et al. Health service utilisation, detection rates by family practitioners, and management of patients with common mental disorders in French family practice. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(8):521–530. doi: 10.1177/0706743716686918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dowrick CF, Bellón JA, Gómez MJ. GP frequent attendance in Liverpool and Granada: the impact of depressive symptoms. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50(454):361–365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gili M, Luciano JV, Serrano MJ, et al. Mental disorders among frequent attenders in primary care: a comparison with routine attenders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199(10):744–749. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31822fcd4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smits FT, Brouwer HJ, Zwinderman AH, et al. Why do they keep coming back? Psychosocial etiology of persistence of frequent attendance in primary care: a prospective cohort study. J Psychosom Res. 2014;77(6):492–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norton J, David M, de Roquefeuil G, et al. Frequent attendance in family practice and common mental disorders in an open access health care system. J Psychosom Res. 2012;72(6):413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrari S, Galeazzi GM, MacKinnon A, Rigatelli M. Frequent attenders in primary care: impact of medical, psychiatric and psychosomatic diagnoses. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(5):306–314. doi: 10.1159/000142523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reid S, Wessely S, Crayford T, Hotopf M. Frequent attenders with medically unexplained symptoms: service use and costs in secondary care. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:248–253. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.3.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McIntyre JC, Wickham S, Barr B, Bentall RP. Social identity and psychosis: associations and psychological mechanisms. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(3):681–690. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Hout B, Janssen MF, Feng YS, et al. Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value Health. 2012;15(5):708–715. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32(9):509–515. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melo S, Corcoran R, Shryane N, Bentall RP. The persecution and deservedness scale. Psychol Psychother. 2009;82(Pt 3):247–260. doi: 10.1348/147608308X398337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elahi A, Perez Algorta G, Varese F, et al. Do paranoid delusions exist on a continuum with subclinical paranoia? A multi-method taxometric study. Schizophr Res. 2017;190:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Launay G, Slade P. The measurement of hallucinatory predisposition in male and female prisoners. Pers Individ Dif. 1981;2(3):221–234. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Department of Health UK Chief Medical Officers’ low risk drinking guidelines. 2016. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/545937/UK_CMOs__report.pdf (accessed 27 Nov 2019)

- 26.NHS Digital Hospital accident and emergency activity, 2015–16. 2017 https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/hospital-accident--emergency-activity/2015-16 (accessed 27 Nov 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 27.NHS Digital The five year forward view for mental health. 2016. www.england.nhs.uk/mentalhealth/taskforce/ (accessed 27 Nov 2019)

- 28.Steventon A, Deeny S, Friebel R, et al. Briefing: emergency hospital admissions in England: which may be avoidable and how? 2018. https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/Briefing_Emergency%2520admissions_web_final.pdf (accessed 27 Nov 2019)

- 29.Mason S, O’Keeffe C, Jacques R, et al. Perspectives on the reasons for emergency department attendances across Yorkshire and the Humber: final report. 2017. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.730630!/file/CLAHRC_BMA_Final_Report.pdf (accessed 27 Nov 2019)

- 30.Stone AA, Bachrach CA, Jobe JB, et al. The science of self-report: implications for research and practice. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leggett LE, Khadaroo RG, Holroyd-Leduc J, et al. Measuring resource utilization: a systematic review of validated self-reported questionnaires. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(10):e2759. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts A, Blunt I, Bardsley M. Focus on: distance from home to emergency care. 2014. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2018-10/1540325897_qualitywatch-distance-emergency-care.pdf (accessed 27 Nov 2019)

- 33.Oliver MI, Pearson N, Coe N, Gunnell D. Help-seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:297–301. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Da Cruz D, Pearson A, Saini P, et al. Emergency department contacts prior to suicide in mental health patients. Emerg Med J. 2011;28(6):467–471. doi: 10.1136/emj.2009.081869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacob KS. The diagnosis and management of depression and anxiety in primary care: the need for a different framework. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(974):836–839. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.051185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baker R, Bankart MJ, Rashid A, et al. Characteristics of general practices associated with emergency-department attendance rates: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(11):953–958. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.050864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giebel C, McIntyre JC, Daras K, et al. What are the social predictors of accident and emergency attendance in disadvantaged neighbourhoods? Results from a cross-sectional household health survey in the north west of England. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e022820. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pearson A, Saini P, Da Cruz D, et al. Primary care contact prior to suicide in individuals with mental illness. Br J Gen Pract. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Coexisting severe mental illness and substance misuse: community health and social care services. NG58. 2016. nice.org.uk/guidance/ng582016 (accessed 27 Nov 2019) [PubMed]

- 40.Baker C. Accident and emergency statistics: demand, performance and pressure. 2017. https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/SN06964 (accessed 27 Nov 2019)