Abstract

We observed fluorescence emission from 2,5-diphenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazole (PPD) resulting from two-photon excitation with two different wavelengths near 380 and 760 nm. For this two-color two-photon (2C2P) excitation the emission spectra and intensity decays were the same as observed with single-photon excitation with an equivalent energy at 250 nm. The two-color two-photon-induced emission was observed when the PPD sample was illuminated with both wavelengths, but only when the picosecond laser pulses were spatially and temporally overlapped. The signal was about 70-fold and 1000-fold less for illumination at 380 or 760 nm alone, respectively. When illuminated with both wavelengths, the emission intensity of PPD depended quadratically on the total illumination power, when both beams were simultaneously attenuated to the same extent, indicating two-photon excitation. When the intensity at one wavelength was attenuated, the signal depended linearly on the power at each wavelength, indicating the participation of one-photon at each wavelength to the excitation process. For 2C2P excitation the time-zero anisotropy was larger than possible for single-photon excitation and was consistent with collinear electronic transitions for both wavelengths. The intensity depended on the polarization of each beam in a manner consistent with collinear transitions. These results demonstrate that two-color two-photon excitation can be readily observed with modern laser sources. This phenomenon can have numerous applications in the chemical and biomedical sciences, as a method for spatial localization of the measured volume.

Introduction

Two-photon spectroscopy has been widely used to study the symmetry of electronic states of organic and biochemical fluorophores.1–6 Since the selection rules for two-photon absorption are different than for one-photon transitions, one can potentially observe states which are not seen in one-photon spectroscopy. Because of the weak two-photon signals, two-photon absorption is most often observed by the induced fluorescence. In recent years the ability to perform two-photon excitation has been improved due to the availability of picosecond and femtosecond laser sources. Consequently, there has been a growing interest in the use of two-photon excitation in time-resolved fluorescence, particularly of biochemical fluorophores.7–10 Additionally, two-photon excitation is being productively used in fluorescence microscopy, where it provides localized excitation at the focal point of the objective.11–13

At present, most experiments with two-photon excitation are accomplished using a single laser beam at a single excitation wavelength. Such experiments are technically simple because the two photons are automatically in the same place at the same time. However, two-photon excitation can also be accomplished with two-photon with different energies, a phenomenon we call two-color two-photon (2C2P) excitation. Such experiments have been reported only infrequently. In pioneering reports McClain and co-workers measured the absorption of benzene and 1-chloronaphthalene at two different wavelengths,14,15 and Frolich and Mahr16 described two-color two-photon absorption of anthracene. Theory has been presented relating the polarized absorption to molecular symmetry.17,18 These pioneering 2C2P experimental studies14–16 were performed using ruby lasers and arc lamps and did not include measurement of fluorescence intensity, decay times, or anisotropy decays. Recent theoretical reports have suggested the possibility of additional information in the time-resolved anisotropy decays with two-color two-photon (2C2P) excitation.19,20 To the best our knowledge, with the exception of NO21 and our own preliminary report on this topic,22 2C2P excitation has not been observed using fluorescence. 2C2P excitation has not been reported with modern laser sources, and there are no reports of the time-resolved intensity and anisotropy decays with 2C2P excitation.

In the present report we describe our initial studies of 2C2P excitation of the fluorophore PPD. This fluorophore was chosen because the absorption spectrum of PPD suggested it could be excited with the fundamental and frequency-doubled output of our Pyridine 2 dye laser, near 380 and 760 nm, respectively, which together yield a 2C2P excitation energy equivalent to 253 nm. Direct one-photon excitation of PPD is not possible at 380 or 760 nm. While nonlinear excitation is preferably accomplished with femtosecond lasers, we expected fewer difficulties in temporal overlap of the 5–10 ps pulses from the dye lasers. PPD was also selected because we had previously examined such scintillators by two- and three-photon excitation and found them to display apparently collinear electronic transitions.23,24 Simple anisotropy behavior would be an advantage in interpreting initial data from the novel 2C2P experiments.

Materials and Methods

The optical arrangement for 2C2P excitation (Scheme 1) was similar to that described for light quenching.25,26 Unless stated otherwise, both beams were vertically polarized. Spatial and temporal overlap was accomplished by maximizing light quenching of Pyridine 2 in methanol, which can be accomplished with 380 and 760 nm, respectively.27,28 Final alignment of the laser beams is accomplished by maximizing the 2C2P signal from PPD. Emission from PPD was isolated using a 337 nm interference filter and magic angle conditions. The concentration of PPD in ethanol or propylene glycol was 0.4 mM, or less for studies of the concentration-dependent 2C2P signal.

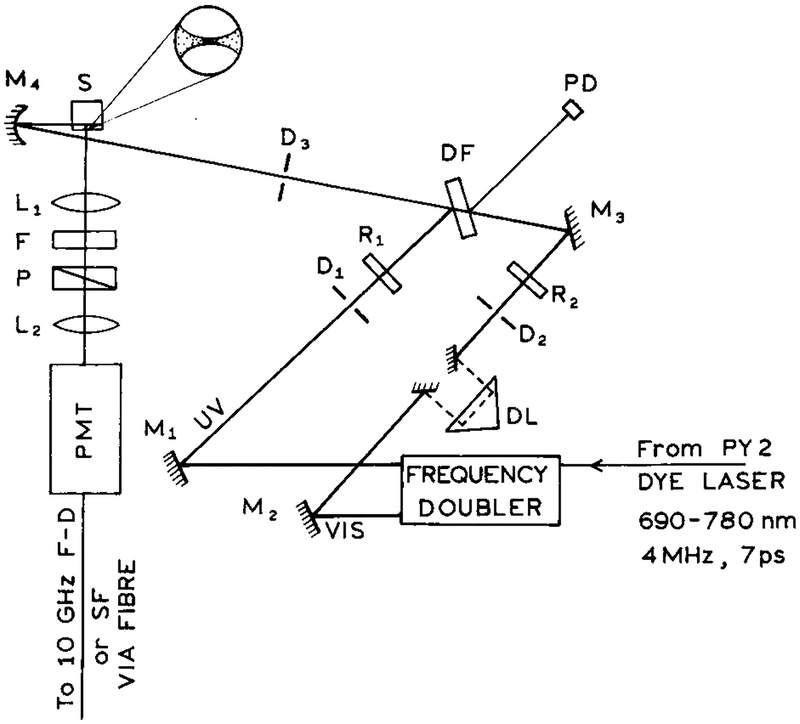

SCHEME 1: Experimental Arrangement for the Two-Color Two-Photon Experimentsa.

a L are lenses, P are polarizers, D are diaphragms, M are mirrors, R are polarization rotators, and F are optical filters. The delay line (DL) is placed in the long-wavelength beam. DF is a coated optical plate (dichroic filter), PD is a reference photodiode, and SF is spectrofluorometer used to measure the emission spectra.

The wavelengths for 2C2P excitation were obtained from the fundamental (760 nm) and frequency-doubled (380 nm) output of a Pyridine 2 dye laser. This dye laser was synchronously pumped by an argon ion laser and cavity dumped at 3.796 MHz. Except when indicated, the optical power at 380 and 760 nm was near 5 and 100 mW, respectively. The beams were focused to about 20 μm diameter spots. The approximate average intensities were 3 × 104 and 1.5 × 103 W/cm2 for the 760 and 380 nm beams, respectively. The approximate peak intensities were 2 × 109 and 1 × 108 W/cm2 for the 760 and 380 nm beams, respectively.

Time-resolved intensity and anisotropy decays were measured on the 10 GHz frequency-domain instrument described previously.29 Intensity and anisotropy decays were recovered from the FD data as described previously.30,31 Intensity decays of PPD were found to be a single exponential

| (1) |

where τ is the decay time. The anisotropy decays were also found to be single exponential

| (2) |

where θ is the correlation time and r0k is the time-zero anisotropy for various modes (k) of excitation. In general, one expects the time-zero anisotropies (r0k) to be different for one- or two-photon excitation. For the case of collinear transitions for absorption (one- or two-photon) and emission, the time-zero anisotropies are expected to be given by

| (3) |

Hence, for one- and two-photon excitation the maximum possible anisotropies are 0.40 and 0.57, respectively.24 Observation of anisotropies in excess of 0.40 demonstrates increased photoselection due to interaction with two or more photons.

Emission spectra were recorded on a steady state spectrofluorometer with the signal being brought to the instrument via an optical fiber. Magic angle polarizer conditions were used in recording the spectra. For measurements with attenuated laser beams we used an equivalent number of neutral density filters for all measurements or corrected for the intensity changes resulting from the additional optical surfaces and/or pulse broadening.

Results

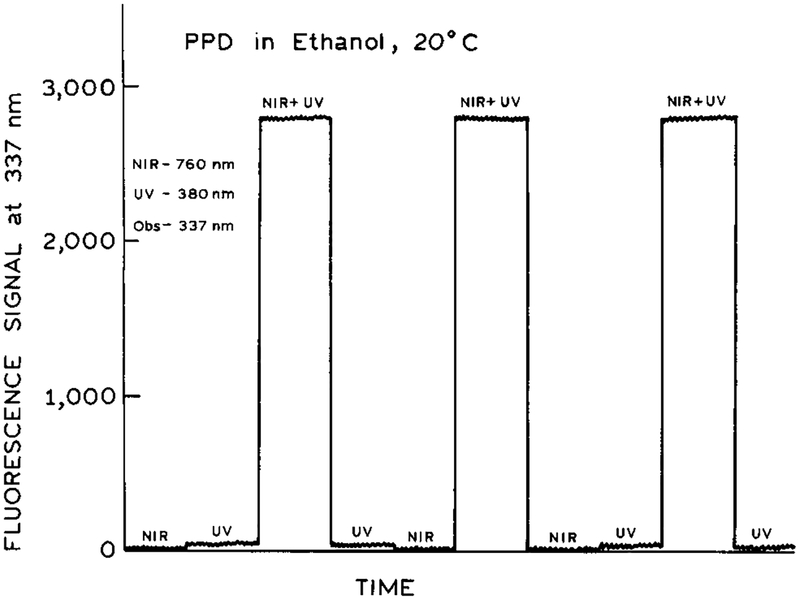

To detect 2C2P excitation, we examined the emission intensity of PPD for illumination at just one wavelength (380 or 760 nm) and for illumination at both wavelengths (Figure 1). By variation of the optical alignment we found conditions which yielded a significant signal observable at 337 nm. This emission signal for simultaneous illumination with both wavelengths greatly exceeded that observed for either wavelength alone (Figure 1). Compared to the 2C2P signal, the PPD signal observed for illumination at 380 or 760 nm was manyfold smaller (Figure 1). More specifically, the signal for illumination at only 380 nm was about 70-fold smaller than with both wavelengths. For illumination at only 760 mm the signal was about 1000-fold smaller than for both wavelengths. Upon simultaneous illumination with both wavelengths no signal could be observed at 253 nm, suggesting the absence of any unwanted generation of 253 nm excitation within the sample itself.

Figure 1.

Emission intensity of PPD in ethanol with near-IR (760 nm), UV (380 nm), and temporally overlapped 380 and 760 nm pulses..

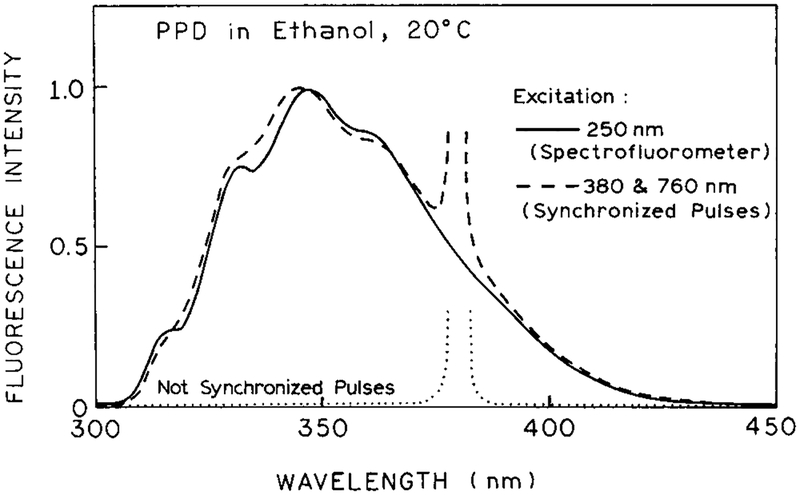

We questioned whether the observed signal was due to emission from PPD. Emission spectra are shown in Figure 2. The emission resulting from combined 380 and 760 nm excitation is seen to be essentially identical from that observed for one-photon excitation of PPD at 250 nm. When the pulses are not synchronized to overlap in the sample, the emission from PPD is not observed, and one observes only the scattered light at 380 nm. No signal (<0.1%) was observed from the solvents alone with one- or two-beam illumination.

Figure 2.

Emission spectra of PPD in ethanol with 250 nm excitation (one-photon) and with 2C2P excitation at 380 and 760 nm. The dotted line shows the signal with nonoverlapping pulses at 380 and 760 nm.

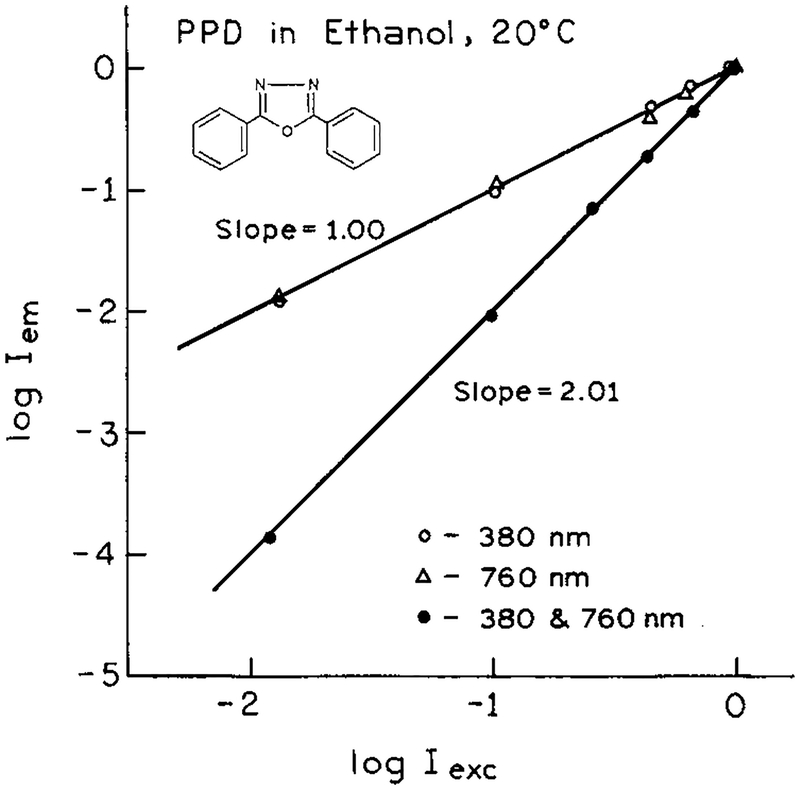

It was of interest to determine how the 2C2P signal depended on the intensity of each laser beam. If both the 380 and 760 nm beams were simultaneously attenuated with neutral density filters the 2C2P signal depended quadratically on intensity (Figure 3). This result indicates that two photons are involved in the excitation process. If each beam is separately attenuated, the 2C2P signal depends linearly on the intensity of each beam (Figure 3), indicating the involvement of one-photon from each beam in the excitation process. Hence, at least for the present fluorophore and wavelengths, the origin of the excitation energy seems clear. In the future one can expect more complex behavior if each beam alone is capable of multiphoton excitation of the fluorophore.

Figure 3.

Dependence of the normalized emission intensity on the excitation intensity for each wavelength at 380 or 760 nm (○, Δ), and for the total intensity at 380 and 760 nm (●).

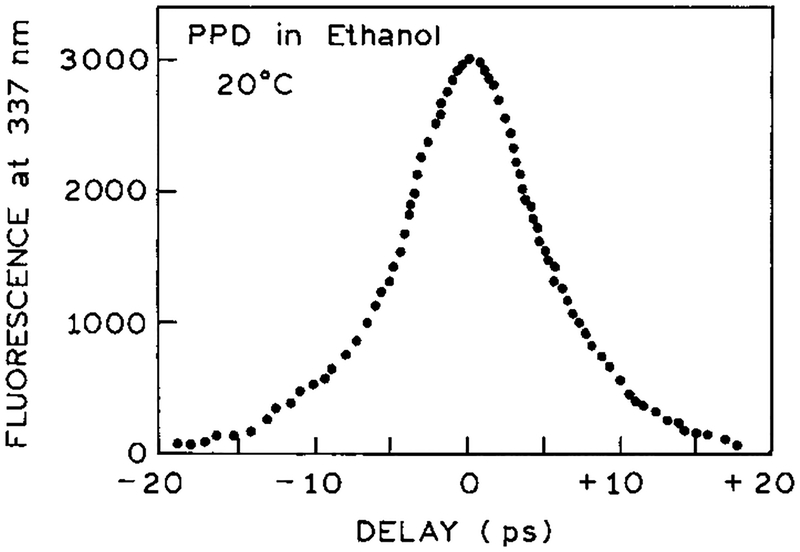

If the 2C2P signal is due to simultaneous interaction with one photon at each wavelength, then one expects the signal to be present only if the pulses are temporally overlapped in the sample. Hence we examined the 2C2P signal as one beam was delayed. The half-width near 10 ps (Figure 4) is consistent with the pulse width of the Pyridine 2 dye laser near 7 ps. This result demonstrates that the two photons must be simultaneously present and that either wavelength alone does not leave the molecule in a state suited for sequential interaction with the other wavelength.

Figure 4.

Effect of temporal overlap (autocorrelation trace) of the 380 and 760 nm pulses on the 2C2P signal.

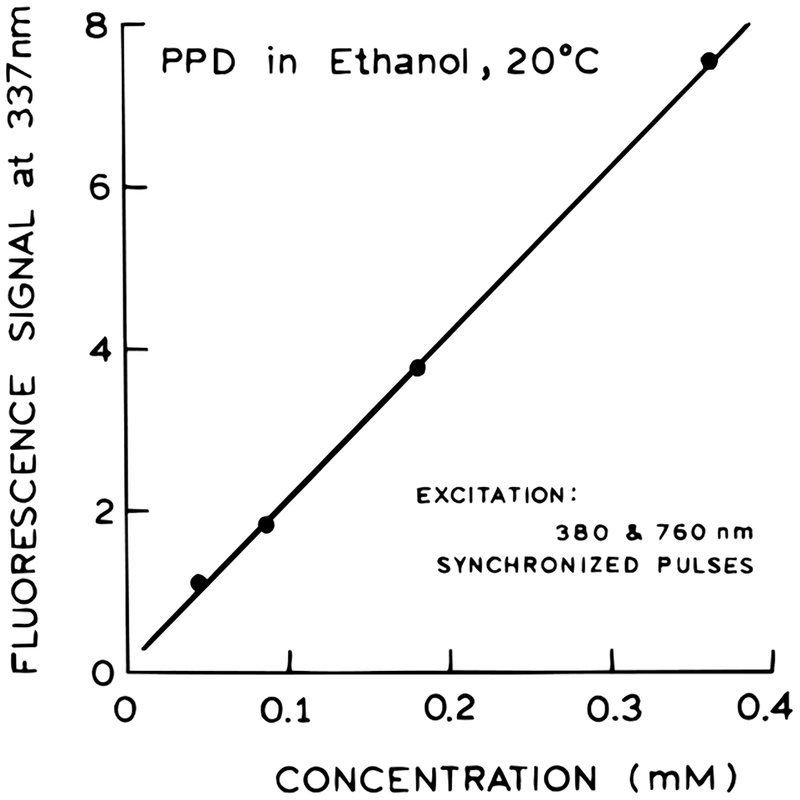

While we were unable to detect photons of combined energy at 253 nm, we thought it was important to consider the possibility that 253 nm light was being generated by the sample and then exciting PPD by a one-photon process. This possibility is excluded by the anisotropy measurements (below) but was also examined by the concentration-dependent signal. Generation of such harmonics is not expected to occur in our isotropic sample. However, if for unknown reasons 253 nm excitation was due to harmonic generation, then one expects the signal to be proportional to the square of the PPD concentration.32–34 We found that the signal was precisely linear with the concentration of PPD, indicating that PPD itself does not generate 253 nm for one-photon excitation (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Dependence of the 2C2P induced emission on PPD concentration.

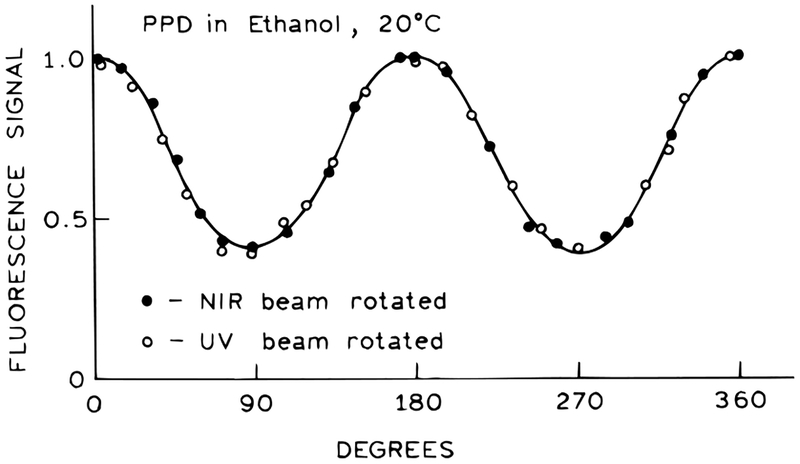

For all the experiments described above both beams were vertically polarized. Hence, it was of interest to examine the effects of rotating the electric vector of either beam (Figure 6). We found that the 2C2P signal varied approximately as a cosine function, with the maximal signal for parallel 380 and 760 nm beams, and the minimum signal when the beams are perpendicular. It did not matter which beam was rotated. However, unlike a cosine function the 2C2P signal did not go to zero for perpendicularly polarized beams (Figure 6), but the minimal value was about one-third of the maximum value. These results seem to be consistent with the virtual electronic transitions at 380 and 760 nm being collinear in the PPD molecule. The value of one-third for perpendicular beams can be understood as the projection of a cos2 θ distribution onto a perpendicular axis,35 where θ is the angle between the polarized excitation and the electronic transition moment in the fluorophore.

Figure 6.

Effect of polarization angle of the 380 and 760 nm beams on the 2C2P signal.

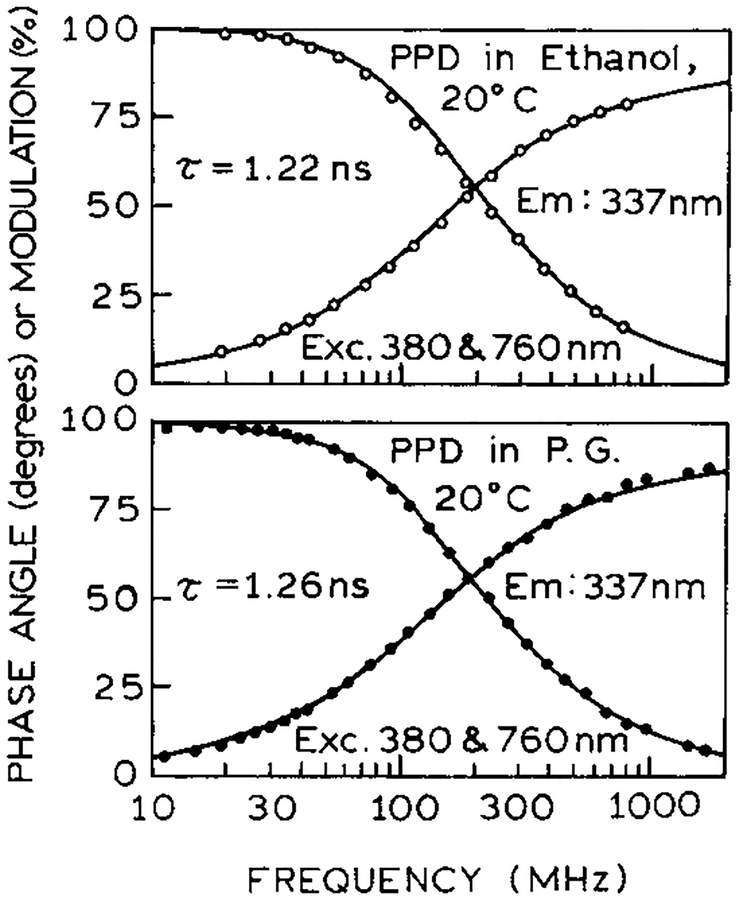

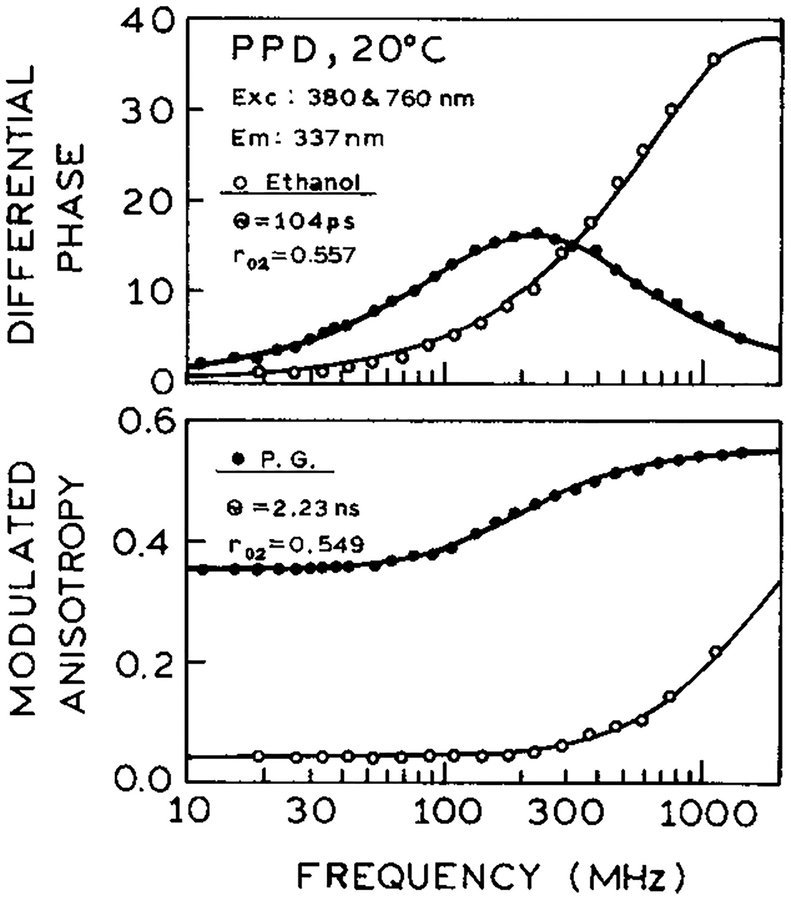

To confirm that the observed signal was in fact due to the usual S1 emission of PPD, we examined the intensity and anisotropy decay. In both ethanol and propylene glycol the decay times were single exponential with τ = 1.24 ns (Figure 7) and equivalent to those observed with one-photon excitation (not shown). The correlation times with 2C2P excitation (Figure 8) were 104 ps and 2.23 ns in ethanol and propylene glycol, respectively, again identical to the one-photon excitation values. However, the time-zero anisotropies (r0) were significantly larger (0.557 and 0.549) than possible with one-photon excitation, which can result in a maximum anisotropy of 0.4 for collinear absorption and emission transitions. Similar high r0 values were observed previously for one-color two-photon or three-photon excitation23,24 and were interpreted in terms of cos4 θ or cos6 θ photoselection for two- and three-photon excitation, respectively. This type of photoselection assumes interaction of each photon with its transition dipole depends on the squared cosine of the angle between the excitation polarization and the transition moment. Hence, it appears that in PPD the virtual transitions behave like collinear one-photon transitions.

Figure 7.

Frequency-domain intensity decays of PPD in ethanol and propylene glycol with 2C2P excitation.

Figure 8.

Frequency-domain anisotropy decays of PPD in ethanol and propylene glycol with 2C2P excitation.

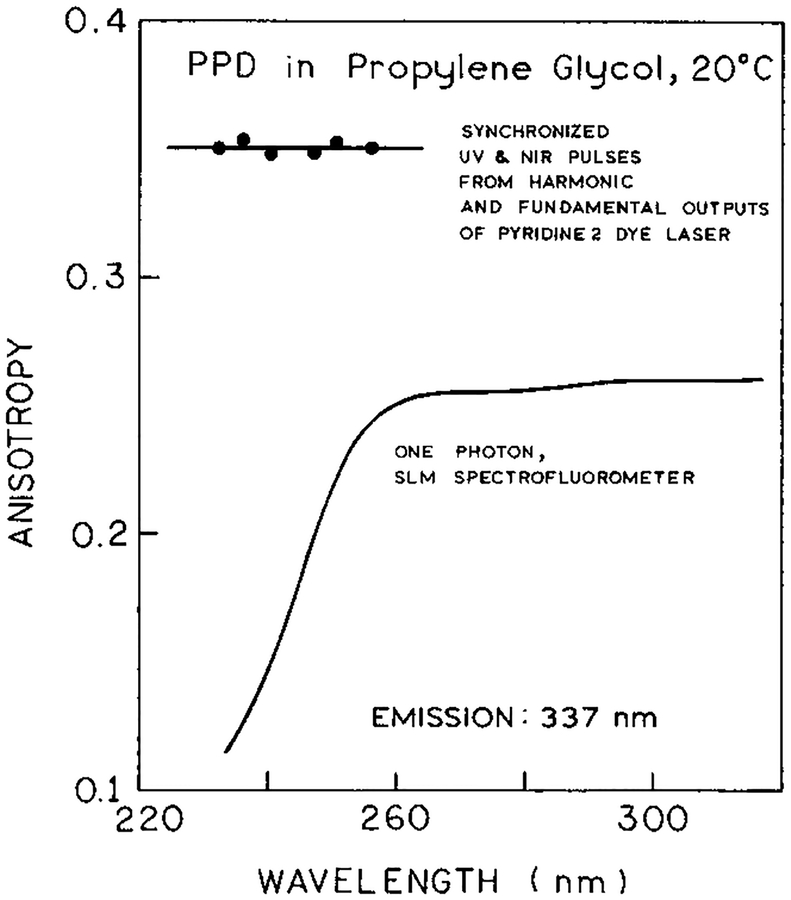

We examined the anisotropy further by comparing the 2C2P anisotropy with that observed for one-photon excitation at equivalent energies. Steady state anisotropies were measured in the usual manner by rotation of the emission polarizers with correction for the G factor. For one-photon excitation the anisotropy is constant above 260 nm, suggesting a collinear electronic transitions for absorption and emission (Figure 9). At shorter wavelengths below 260 nm the anisotropy drops, indicating excitation into a higher electronic state whose transition is not collinear with the emission. In contrast, for 2C2P excitation, the anisotropy remains high for excitation with energies equivalent to 231–255 nm (Figure 9). Similar high anisotropies were observed for other fluorophores with one-color two-photon excitation where the anisotropy remained higher than expected from the one-photon anisotropy spectrum.8,36 In general, it appears that multiphoton excitation is more likely to display collinear transitions than one-photon excitation, but we do not understand the origin of this phenomenon.

Figure 9.

Steady state anisotropy spectra of PPD in propylene glycol at 20 °C measured with one-photon excitation (SLM, –) and 2C2P excitation (●). The wavelengths for 2C2P excitation correspond to the sum of near-IR and UV photons energies. The wavelengths were changed from 700 to 770 nm (near-IR) and from 350 to 385 nm (UV).

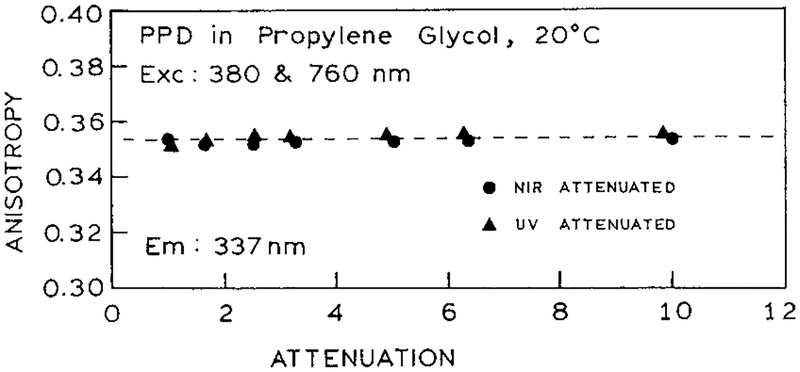

The anisotropy of PPD was further examined with attenuation of just one of the excitation beams. We reasoned that the presence of simultaneous multiphoton interaction with one of the beams, or the presence of noncollinear transitions, would be more evident if the dominant signal results from one of the beams. The anisotropy remained constant for all levels of each beam (Figure 10). Hence, it seems that PPD only interacts with one photon at each wavelength, and we were unable to induce more complex behavior by adjusting the relative power of each beam.

Figure 10.

Independence of measured anisotropy on the excitation power.

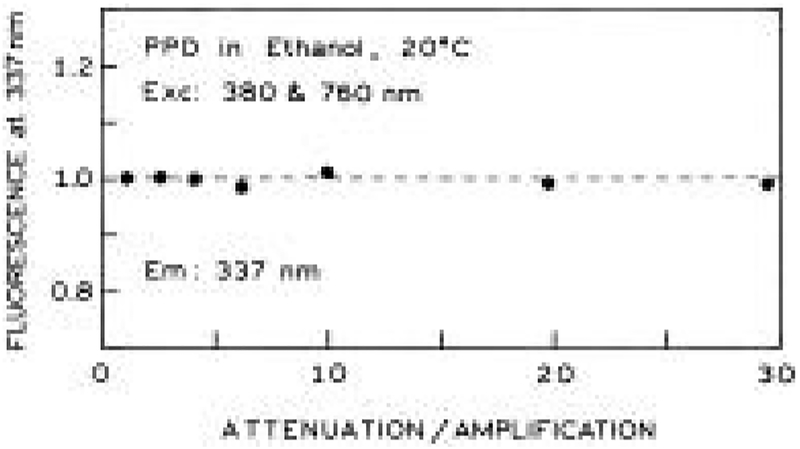

The proceeding experiment caused us to realize that the power of each beam could be independently adjusted provided the intensity of the other beam was adjusted in the opposite manner. For instance, suppose we had observed two-photon or multiphoton excitation upon illumination with just one of the laser beams. This signal could be regarded as an undesirable background on the desired 2C2P signal. In such cases one could attenuate the troublesome beam and maximize the intensity of the beam which does not result in a background signal. This possibility is demonstrated experimentally in Figure 11 in which we attenuated one of the beams, with a compensating increase in intensity of the other beam. The 2C2P signal was found to be dependent only on the total intensity and not on the individual intensities of each beam (Figure 11). This feature of 2C2P excitation may be particularly valuable in fluorescence microscopy or chemical sensing, where there is a background from one of the beams. The undesired background can be minimized by using a lower intensity for this beam and increased intensity for the second beam.

Figure 11.

Effect of compensating changes in the intensity of the UV and near-IR beams. The fluorescence signal does not depend on the location of the neutral density filters (UV or near-IR beams).

Discussion

Two-color two-photon excitation has considerable potential in chemical and biochemical spectroscopy. At the most basic level the use of two excitation beams provides independent control of the wavelength, polarization, intensity, and pulse width of the two excitation beams. Previous reports have already indicated that additional information is available about the symmetry of excited states from experiments with different polarization17,18 and that the anisotropy decays may be distinct with two-color and one-color two-photon excitation.19–20 Additionally, control of these intensity or wavelength of each beam may provide an ability to decrease unwanted background signals. Control of each wavelength provides an opportunity to measure new types of excitation and excitation anisotropy spectra in which one of the wavelength is held constant while the other is varied. It is possible that some transitions or anisotropy values will be observed with 2C2P excitation which are not accessible with the one-color measurements.6,17 For instance, in 2C2P excitation one can independently control the polarization of each photon, which can be expected to result in an excited state population which is not symmetric about the z axis. At present we do not know what to expect from such experiments which represent a new class of fluorescence spectral data.

Another opportunity of 2C2P excitation is the ability to localize the excited volume at the desired point by overlap of the excitation beam. This feature of 2C2P excitation can be advantageous in analytical chemistry and fluorescence microscopy. For instance, in capillary electrophoresis the excitation can be localized at the desired position and thereby minimize the background signal from optical elements or the sample volume. In favorable circumstances it may be possible to vary the wavelengths or intensities of the excitation beams to result in minimal background from interfering substances. These potential advantages of 2C2P excitation seem equally valuable in fluorescence microscopy, where the overlapped beams can provide localized excitation in a manner comparable to confocal methods.37 In fact, Hell38 has already suggested that one-color two-photon excitation, with offset beams, could be used to obtain increased lateral resolution in far-field fluorescence microscopy.

In previous reports we described the use of light pulses, with wavelengths overlapping the emission spectra, to modify the excited state population, orientation, and emission spectra of fluorophores.26,39–41 This phenomenon, which we call light quenching, has already been applied to fluorescence microscopy.28,42 In ref 42 the authors describe the use of a modulated signal when the light quenching pulses are at a repetition frequency offset from the excitation pulse rate. One can readily imagine the use of 2C2P excitation in an analogous manner, in which the signal arises from the region of beam overlap. An advantage of 2C2P excitation in microscopy, as compared to “a synchronous pump–probe microscopy”,42 is the appearance of a signal against a dark background. In pump–probe microscopy42 the modulated signal appears against the bright background of the excited fluorophore.

In conclusion, the study of 2C2P excitation is just beginning. One can expect rapid development of the understanding and applications of this phenomenon.

Acknowledgment.

This work was supported by the NIH National Center for Research Resources (Grants RR-08119 and RR-10416).

References and Notes

- (1).Friedrich DM; McClain WM Two-Photon Molecular Electronic Spectroscopy. Annu. ReV. Phys. Chem 1980, 31, 559–577. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Wirth MJ; Koskelo A; Sanders MJ Molecular Symmetry and Two-Photon Spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc 1981, 35, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Wirth MJ; Koskelo AC; Mohler CE; Lentz BL Identification of Methyl Derivatives of Naphthalene by Two-Photon Symmetry Parameters. Anal. Chem 1981, 53, 2045–2048. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Masthay MB; Findsen LA; Pierce BM; Bocian DF; Lindsey JS; Birge RR A Theoretical Investigation of the One- and Two-Photon Properties of Porphyrins. J. Chem. Phys 1986, 84, 3901–3915. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Birge RR Two-Photon Spectroscopy of Protein-Bound Chromophores. Acc. Chem. Res 1986, 19, 138–146. [Google Scholar]

- (6).McClain WM Two-Photon Molecular Spectroscopy. Acc. Chem. Res 1974, 7, 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Lakowicz JR; Gryczynski I; Kusba J; Danielsen E Two-Photon Induced Fluorescence Intensity and Anisotropy Decays of Diphenylhexatriene in Solvents and Lipid Bilayers. J. Fluoresc 1992, 2, 247–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Lakowicz JR; Gryczynski I Fluorescence Intensity and Anisotropy Decay of the 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole–DNA Complex Resulting from One-Photon and Two-Photon Excitation. J. Fluoresc 1992, 2, 117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lakowicz JR; Gryczynski I Tryptophan Fluorescence Intensity and Anisotropy Decays of Human Serum Albumin Resulting from One-Photon and Two-Photon Excitation. Biophys. Chem 1993, 45, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Anderson BE; Jones RD; Rehms AA; Ilich P; Callis PR Polarized Two-Photon Fluorescence Excitation Spectra of Indole and Benzimidazole. Chem. Phys. Lett 1986, 125, 106–112. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Denk W; Strickler JH; Webb WW Two-Photon Laser Scanning Fluorescence Microscopy. Science 1990, 248, 73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Denk W; Delaney KR; Gelperin A; Kleinfeld D; Strowbridge BW; Tank DW; Yuste R Anatomical and Functional Imaging of Neurons Using 2-Photon Laser Scanning Microscopy. J. Neurosci. Methods 1994, 54, 151–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Denk W; Piston DW; Webb WW Two-Photon Molecular Excitation in Laser-Scanning Microscopy in Handbook of Biological Confocal Microscopy; Pawley JB, Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, 1995; pp 445–458. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Monson PR; McClain WM Polarization Dependence of the Two-Photon Absorption of Tumbling Molecules with Application to Liquid 1-Chloronaphthalene and Benzene. J. Chem. Phys 1970, 53, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Monson PR; McClain WM Complete Polarization Study of the Two-Photon Absorption of Liquid 1-Chloronaphthalene. J. Chem. Phys 1972, 56, 4817–4825. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Frolich D; Mahr H Two-Photon Spectroscopy of Anthracene. Phys. ReV. Lett 1966, 16, 895–898. [Google Scholar]

- (17).McClain WM Excited State Symmetry Assignment through Polarized Two-Photon Absorption Studies of Fluids. J. Chem. Phys 1971, 55, 2789–2796. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Dowley MW; Eisenthal KB; Peticolas WL Two-Photon Laser Excitation of Polycyclic Aromatic Molecules. J. Chem. Phys 1967, 47, 1609–1619. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Wan C; Johnson CK Time-Resolved Anisotropic Two-Photon Spectroscopy. Chem. Phys 1994, 179, 513–531. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Wan C; Johnson CK Time-Resolved Two-Photon Induced Anisotropy Decay: the Rotational Diffusion Regime. J. Chem. Phys 1994, 101, 10283–10291. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Lahmani F; Lardeux C; Solgadi D; Zehmacker Z; Dimicoli I; Boivineau M; Mons M; Piuzzi F Two-Color Two-Photon Excitation of the NO(A2Σ+) State. J. Phys. Chem 1985, 89, 5646–5649. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Lakowicz JR; Gryczynski I; Malak H; Gryczynski Z Two-Color Two-Photon Excitation of Fluorescence. Photochem. Photobiol 1996, 64, 632–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Lakowicz JR; Gryczynski I; Gryczynski Z; Danielsen E; Wirth MJ Time Resolved Fluorescence Intensity and Anisotropy Decays of 2,5-Diphenyloxazole by Two-Photon Excitation and Frequency-Domain Fluorometry. J. Phys. Chem 1992, 96, 3000–3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Gryczynski I; Malak H; Lakowicz JR Three-Photon Induced Fluorescence of 2,5-Diphenyloxazole with a Femtosecond Ti:Sapphire Laser. Chem. Phys. Lett 1995, 245, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Gryczynski I; Kuśba J; Lakowicz JR Light Quenching of Fluorescence Using Time-Delayed Laser Pulses as Observed by Frequency-Domain Fluorometry. J. Phys. Chem 1994, 98, 8886–8895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Gryczynski I; Kuśba J; Gryczynski Z; Malak H; Lakowicz JR Effect of Fluorescent Quenching by Stimulated Emission on the Spectral Properties of a Solvent Sensitive Fluorophore. J. Phys. Chem 1996, 100, 10135–10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Gryczynski I; Lakowicz JR Steady State and Time-Resolved Light Quenching of Pyridine 2. Manuscript in preparation [Google Scholar]

- (28).Hell SW; Schrader M; Bahlmann K; Meinecke F; Lakowicz JR; Gryczynski I Stimulated Emission on Microscopic Scale: Light Quenching of Pyridine 2 Using a Ti:Sapphire Laser. J. Microsc 1995, 180, RP1–RP2. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Laczko G; Lakowicz JR; Gryczynski I; Gryczynski Z; Malak HA 10 GHz Frequency-Domain Fluorometer. ReV. Sci. Instrum 1990, 61, 2311–2337. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Lakowicz JR; Gratton E; Laczko G; Cherek H; Limkeman M Analysis of Fluorescence Decay Kinetics from Variable-Frequency Phase Shift and Modulation Data. Biophys. J 1984, 46, 463–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Lakowicz JR; Cherek H; Kuśba J; Gryczynski I; Johnson ML Review of Fluorescence Anisotropy Decay Analysis by Frequency-Domain Fluorescence Spectroscopy. J. Fluoresc 1993, 3, 103–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Peticolas WL Multiphoton Spectroscopy. Annu. ReV. Phys. Chem 1967, 18, 233–260. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Petricolas WL; Rieckhoff KE Double-Photon Excitation of Organic Molecules in Dilute Solution. J. Chem. Phys 1963, 39, 1347–1348. [Google Scholar]

- (34).McMahon DH; Soref RA; Franklin AR Quantitative Measurements of Double-Photon Absorption in the Polycyclic Benzene Ring Compounds. Phys. ReV. Lett 1965, 14, 1060–1062. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Lakowicz JR, Ed. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy; Plenum Press: New York, 1983; 496 pp (see p 157). [Google Scholar]

- (36).Gryczynski I; Lakowicz JR Fluorescence Intensity and Anisotropy Decays of the DNA Strain HOECHST 33342 Resulting from One-photon and Two-photon Excitation. J. Fluoresc 1994, 4, 331–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Pawley JB, Ed. Handbook of Biological Confocal Microscopy; Plenum Press: New York, 1990; revised edition, 232 pp. 1995; 2nd ed., 632 pp. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Hell S Improvement of Lateral Resolution in Far-Field Light Microscopy Using Two-Photon Excitation with Offset Beams. Opt. Commun 1994, 106, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Lakowicz JR; Gryczynski I; Kuśba J; Bogdanov V Light Quenching of Fluorescence: A New Method To Control the Excited State Lifetime and Orientation of Fluorophores. Photochem. Photobiol 1994, 60, 546–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Gryczynski I; Kuśba J; Lakowicz JR Effects of Light Quenching on the Emission Spectra and Intensity Decays of Fluorophore Mixtures. J. Fluoresc, submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Gryczynski I; Kuśba J; Lakowicz JR Wavelength-Selective Light Quenching of Biochemical Fluorophores. J. Biomed. Opt, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Dong CY; So PTC; French T; Gratton E Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging by a Synchronous Pump-Probe Microscopy. Biophys. J 1995, 69, 2234–2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]