Abstract

Background

Chronic pain is associated with decreased quality of life and is one of the most common reasons adults seek medical care, making treatment imperative for many aspects of patient well-being. Chronic pain management typically involves the use of Schedule II full μ-opioid receptor agonists for pain relief; however, the increasing prevalence of opioid addiction is a national crisis that is impacting public health and social and economic welfare. Buprenorphine is a Schedule III partial μ-opioid receptor agonist that is an equally effective but potentially safer treatment option for chronic pain than full μ-opioid receptor agonists. The purpose of this review is to provide an overview of the clinical efficacy and safety of the transdermal and buccal formulations of buprenorphine, which are approved by the Food and Drug Administration for chronic pain, compared with that of extended-release full μ-opioid receptor agonists.

Methods

Controlled or randomized controlled clinical trial information was retrieved from EMBASE, Medline, and PubMed using the search terms “buprenorphine” AND “chronic” AND “pain.”

Results

A total of 33 clinical studies were ultimately used in this review, including 29 (88%) on transdermal buprenorphine and 4 (12%) on buprenorphine buccal film. Although the measure of pain intensity varied among studies, each of these 33 trials demonstrated efficacy for buprenorphine in pain relief. A total of 28 studies also assessed safety, with each concluding that buprenorphine was generally well tolerated.

Conclusion

Comparison of current clinical data along with results of responder and safety analyses support the use of buprenorphine over full μ-opioid receptor agonists for effective preferential treatment of chronic pain; however, head-to-head clinical studies are warranted.

Keywords: opioids, Schedule III, partial μ-opioid receptor agonist

Introduction

Chronic pain is ongoing pain that persists for 6 months or more; it is one of the most common reasons adults seek medical care.1 It is estimated that 50 million adults in the United States experience chronic pain, and 19.6 million adults experience high-impact chronic pain, which frequently limits life or work activities.1 Chronic pain has been linked to various comorbidities including anxiety, depression, and suicide.1,2 Achieving adequate pain relief is therefore important for improving quality of life in patients with chronic pain.

Chronic pain treatment typically involves Schedule II full μ-opioid receptor analgesics; however, the high and increasing prevalence of opioid addiction is a serious national crisis for public health and social and economic welfare.3,4 Opioid addiction creates challenges for the patient and physician in effectively treating chronic pain while adhering to state-mandated regulations and preventing misuse and addiction.5–7 The management of chronic pain with potentially safer yet equally effective treatment options is needed.

Buprenorphine is a relatively modern atypical opioid that is derived from the opium alkaloid thebaine of the poppy Papaver somniferum.8,9 It has been used as an analgesic in the United States since 1981.10,11 Buprenorphine functions by targeting the opioid receptors μ, δ, and κ and opioid receptor-like 1 (ORL1).4 Multimechanistic effects are observed in vitro depending on the receptor subtype, as buprenorphine is a partial agonist at the μ-opioid receptor, an antagonist at the δ- and κ-opioid receptors, and an agonist at ORL1.9

Because the μ-opioid receptor is well-known for its role in analgesia, misconceived notions regarding the efficacy of buprenorphine as an analgesic have been based on its classification as a partial agonist;12–14 however, partial agonism at the µ-opioid receptor does not limit the full analgesic efficacy of buprenorphine and in fact may explain the decreased likelihood of respiratory depression and abuse potential.13,15–18 In addition, the antagonistic effects of buprenorphine at the δ- and κ-opioid receptors may contribute to its favorable safety and tolerability profile by decreasing the risks of respiratory depression, constipation, and suicidal tendencies, as well as potentiating anti-depressant and anti-anxiety effects.9,19–22 Agonistic activity at ORL1 may also contribute to buprenorphine’s analgesic efficacy, as it has been shown to promote analgesia in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord.23

Treatment options for chronic pain, such as buprenorphine, are especially important when the United States is facing increasing opioid misuse and related overdoses.24,25 Because buprenorphine has less potential for abuse than drugs or substances in Schedules I and II, it has been classified by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as a Schedule III controlled substance.21 Orally administered buprenorphine has only approximately 10% bioavailability, but recent advances in drug delivery circumvent this issue.26 The sublingual formulation provides approximately 28–51% bioavailability, the transdermal formulation provides approximately 15%, and the buccal film exhibits 46–65% bioavailability. Each of these formulations bypasses first-pass metabolism.24,27–30

Buprenorphine transdermal system (Butrans®, Purdue Pharma, LP, Stamford, CT) and buprenorphine buccal film (Belbuca®, BioDelivery Sciences International, Inc, Raleigh, NC) are the two formulations currently indicated for the management of pain that is severe enough to require daily, around-the-clock, long-term opioid treatment and for which alternative treatment options are inadequate.23,24 This standard labeling is required on all extended-release (ER) or long-acting opioids indicated for chronic pain. The purpose of this review is to provide an overview of the clinical efficacy and safety of these Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved buprenorphine formulations and to elaborate on the current data that support its effective and potentially safer use in chronic pain management compared with ER Schedule II opioids.

Materials And Methods

EMBASE, Medline, and PubMed searches were conducted on April 11, 2019, using the terms “buprenorphine” AND “chronic” AND “pain”. The search was restricted to controlled or randomized controlled clinical trials in humans that were published in English and for which full texts were available (ie, not a meeting abstract). Articles that did not include standard outcomes of pain intensity or quality of life measures were considered irrelevant and were not included. Other references were added at the authors’ discretion. A reduction in pain or improvement in quality of life that was considered by the authors of the study to provide utility for transdermal buprenorphine or buprenorphine buccal film in the management of chronic pain was regarded as a positive overall outcome.

Results

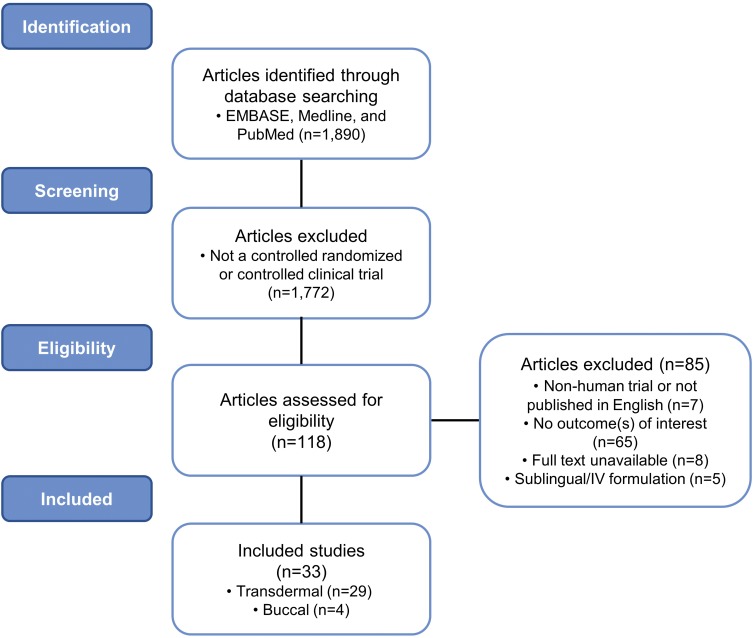

A total of 118 studies were assessed for eligibility. The abstracts were screened and analyzed, resulting in the exclusion of 85 studies. A total of 33 clinical studies obtained with the search criteria were ultimately included in this review, 29 (88%) of which examined transdermal buprenorphine and 4 (12%) of which examined buprenorphine buccal film (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram: clinical trial identification and inclusion. Schematic detailing the search criteria used in this review to identify relevant clinical trials of buprenorphine in chronic pain management.

Transdermal Formulation

The safety and efficacy of transdermal buprenorphine has been studied in multiple chronic pain populations (Table 1).31–59 On the basis of the search criteria used here, 12 (41%) studies examined general chronic pain, 10 (34%) examined chronic low back pain, 5 (17%) examined osteoarthritis pain, 1 (3%) examined chronic malignant pain, and 1 (3%) examined musculoskeletal pain. The duration of these studies ranged from 6 days to 5.7 years, with the doses of transdermal buprenorphine ranging from 5 to 140 µg/h (in the United States, 20 µg/h is the highest dosage strength available). A total of 11 (38%) studies were placebo controlled, 7 (24%) had no comparator, 7 (24%) compared against buprenorphine dose, duration, or formulation differences, 3 (10%) used an analgesic comparator, 2 (7%) used age comparators, and 1 (3%) compared against supplemental analgesics. Examination of multiple comparators by some studies was taken into account.

Table 1.

Summary Of Transdermal Buprenorphine Clinical Studies

| First Author (Year) | Population | Transdermal Dose | Comparator | Duration | Primary Objective | Adverse Events ≥10% | Efficacy Results | Safety Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Böhme (2002)31 | General chronic pain | 35, 52.5, or 70 µg/h | Placebo | Run-in: 0–6 days; Double-blind: 6–15 days; OLE: mean duration of 4.8 months | To demonstrate the analgesic efficacy of transdermal buprenorphine | Application site erythema and pruritus and nausea | Transdermal buprenorphine relieved pain, had a high level of patient compliance, and improved QoL | The adverse events reported were of low incidence and mild intensity |

| Gianni (2011)33 | General chronic pain; elderly | 17.5, 35, 52.5, 70, 105, or 140 µg/h | – | Observation period: 3 months | To assess the safety of transdermal buprenorphine in geriatric patients with chronic noncancer pain, with particular focus on cognitive and behavioral outcomes | Nausea, constipation, sleepiness, and skin rash | Transdermal buprenorphine significantly reduced pain (p<0.01), improved sleep duration (p<0.01), improved mood (p<0.01), and allowed for partial resumption of activities (p<0.05) compared with baseline | Transdermal buprenorphine did not influence cognitive and behavioral abilities and was well tolerated |

| Hakl (2012)36 | General chronic pain | 35, 52.5, or 70 µg/h | – | Post-marketing observation: 3 months | To evaluate transdermal buprenorphine in routine clinical practice | None | In routine clinical practice, transdermal buprenorphine significantly reduced mean pain intensity (p<0.01) from baseline | Transdermal buprenorphine was well tolerated |

| Likar (2006)40 | General chronic pain | 35 µg/h | – | Open-label: up to 5.7 years | To obtain data on the efficacy and tolerability of long-term treatment with transdermal buprenorphine | Application site erythema and pruritus | Transdermal buprenorphine was effective for the long-term treatment of chronic pain | Transdermal buprenorphine was generally well tolerated |

| Likar (2007)41 | General chronic pain | Mean dose of 49.9 µg/h | 3- vs 4-day wear for patch | Open-label: 24 days | To evaluate the potential for extending the time that the buprenorphine patch was worn | Erythema and itching | A 4-day transdermal buprenorphine regimen was as efficacious as 3-day, as there were no significant differences between treatment groups (p=1.0) | Transdermal buprenorphine was well tolerated |

| Likar (2008)42 | General chronic pain; elderly | Mean doses of 35, 40, and 50 µg/h | Age comparator; ≤50, 51–64, or ≥65 years | Observation period: 28 days | To compare the efficacy and tolerability of transdermal buprenorphine in elderly patients and younger populations | Dizziness and giddiness, nausea, malaise and fatigue, pruritus, vomiting, constipation, edema, micturition problems, hyperhidrosis | Transdermal buprenorphine was an effective analgesic in the elderly; daily mean pain intensities were significantly lower in elderly patients (p<0.005) than in younger age groups | Transdermal buprenorphine was well tolerated |

| Serpell (2016)48 | General chronic pain | 5–70 µg/h | – | Observation period: 1–3 years | To establish the incidence and severity of AEs and reasons for discontinuing treatment with transdermal buprenorphine | Skin irritation, constipation, nausea, dizziness, erythema, papules, and sleep disorder | In everyday clinical practice, most patients reported that transdermal buprenorphine therapy was effective, and they were satisfied with their treatment | Transdermal buprenorphine was well tolerated in patients with a variety of chronic pain conditions and comorbidities |

| Silverman (2017)49 | General chronic pain | 5, 10, or 20 µg/h | Transdermal buprenorphine 5, 10, or 20 µg/h + supplemental IR opioids | OLE: 6 months | To describe the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of transdermal buprenorphine when used concomitantly with IR opioids for supplemental analgesia during chronic pain management | Headache | Pain intensity and interference scores improved and were maintained in the IR group; IR opioids are acceptable for supplemental analgesia | The safety profile was similar between groups; transdermal buprenorphine was well tolerated |

| Sittl (2003)50 | General chronic pain | 35, 52.5, or 70 µg/h | Placebo | Double-blind: 15 days | To determine the number of responders in each treatment group, defined as any patient who required no more than 1 sublingual tablet of buprenorphine as rescue medication per day from day 2 until the end of the study and who recorded at least satisfactory pain relief at each application of a new patch | Application site erythema, pruritus, and exanthema | Transdermal buprenorphine (35 and 52.5 µg/h) achieved significant response rates (p<0.05), and all doses improved pain relief and sleep duration | Transdermal buprenorphine was well tolerated |

| Skvarc (2012)51 | General chronic pain | 35, 52.5, or 70 µg/h | – | Observation period: 3 months | To evaluate routine clinical practice with transdermal buprenorphine | Constipation and nausea | Transdermal buprenorphine provided effective analgesia | Transdermal buprenorphine was well tolerated |

| Sorge (2004)52 | General chronic pain | 35 µg/h | Placebo | Run-in: 6 days; Double-blind: 9 days | To compare the amount of rescue medication required during the double-blind phase compared with the run-in and to evaluate patients’ assessment of pain intensity, pain relief, and sleep duration | Pruritus and erythema | In the double-blind phase, the need for rescue medication significantly decreased (p=0.03) compared with placebo; transdermal buprenorphine achieved adequate pain relief along with a reduction in pain intensity and showed a trend in improvements in the duration of sleep compared with placebo | Transdermal buprenorphine was well tolerated |

| Vondráčková (2012)55 | General chronic pain | 35, 52.5, or 70 µg/h | – | Observation period: 3 months | To evaluate the use of transdermal buprenorphine in routine clinical practice | None | Transdermal buprenorphine significantly reduced mean pain intensity (p<0.01) compared with baseline in daily clinical practice | Transdermal buprenorphine was well tolerated |

| Gordon (2010)34 | Chronic low back pain; opioid-experienced | 10–40 µg/h | Placebo | Double-blind crossover: 8 weeks; OLE: 6 months | To assess the efficacy and safety of transdermal buprenorphine | Nausea, dizziness, pruritus, vomiting, somnolence, rash, dry mouth, constipation, sweating, asthenia, headache | Transdermal buprenorphine significantly lowered mean pain intensity scores (p=0.02) and improved sleep (p=0.03) compared with placebo | Transdermal buprenorphine provided an acceptable tolerability profile with dose titration |

| Gordon (2010)35 | Chronic low back pain | 5–20 µg/h | Placebo | Double-blind crossover: 8 weeks; OLE: 6 months | To evaluate the safety and efficacy of transdermal buprenorphine | Nausea, somnolence, pruritus, asthenia, constipation, insomnia, dizziness, sweating, pain, anorexia, vomiting, yawn, nervousness, rash, headache, diarrhea | Transdermal buprenorphine resulted in significantly lower mean daily pain scores (p=0.036), while also improving QoL and functional disability measures compared with placebo | Transdermal buprenorphine was well tolerated |

| Miller (2013)43 | Chronic low back pain; opioid-experienced | 20 µg/h | 5 µg/h transdermal buprenorphine | Double-blind: 12 weeks; OLE: 52 weeks | To evaluate the impact and maintenance of effects of transdermal buprenorphine on health-related QoL | – | 20 µg/h transdermal buprenorphine produced larger improvements than 5 µg/h in role limitations due to physical health (p<0.01); QoL improvements associated with 20 µg/h persisted in the OLE | – |

| Miller (2014)44 | Chronic low back pain | 10 or 20 µg/h | Placebo | Double-blind: 12 weeks | To examine the impact of transdermal buprenorphine on the ability to perform activities of daily living that relate to functioning with lower back pain | – | Transdermal buprenorphine significantly improved the ability to carry out certain activities of daily living related to sleeping, lifting, bending, and working (p<0.05) compared with placebo | – |

| Pota (2012)46 | Chronic low back pain | 35 µg/h + pregabalin 300 mg/d | 35 µg/h transdermal buprenorphine | Single-blind: 3 weeks transdermal only + 3 weeks transdermal + pregabalin or placebo | To evaluate the efficacy and safety of combined transdermal buprenorphine and pregabalin | Somnolence, dizziness, nausea, and constipation | Significant improvements in pain (p<0.05) were obtained in both treatment groups; transdermal buprenorphine improved sleep quality that was enhanced with pregabalin | Both treatments were well tolerated |

| Steiner (2011)53 | Chronic low back pain; opioid-experienced | 20 µg/h | 5 µg/h transdermal buprenorphine | Run-in: 21 days; Double-blind: 12 weeks | To determine average pain in the last 24 hrs upon treatment with transdermal buprenorphine | Run-in: nausea, any application site AE, and headache; Double-blind: any application site AE; application site pruritus, erythema, and rash; nausea; headache | Transdermal buprenorphine provided clinically meaningful pain management, with 20 µg/h providing significantly better pain relief than 5 µg/h (p<0.001) while also significantly improving sleep (p<0.001) and reducing the need for supplemental analgesia (p=0.006) | Transdermal buprenorphine was well tolerated |

| Steiner (2011)54 | Chronic low back pain | 10 or 20 µg/h | Placebo | Run-in: 27 days; Double-blind: 12 weeks | To evaluate the efficacy, tolerability, and safety of transdermal buprenorphine in opioid-naive patients | Run-in: nausea, dizziness, and headache Double-blind: nausea | Transdermal buprenorphine significantly reduced pain (p=0.01) and resulted in fewer sleep disturbances, less supplemental analgesia, and greater improvements in physical and mental health compared with placebo | Transdermal buprenorphine was well tolerated |

| Yarlas (2013)56 | Chronic low back pain | 10 or 20 µg/h | Placebo | Run-in: 27 days; Double-blind: 12 weeks | To evaluate the impact of treatment with transdermal buprenorphine on health-related QoL and the correspondence between QoL and pain | – | Transdermal buprenorphine produced significantly larger improvements in all QoL domains (p<0.05), including eliminating deficits in pain, social functioning, and role limitations and enhancing QoL, than placebo | – |

| Yarlas (2015)57 | Chronic low back pain | 10 or 20 µg/h | Placebo | Run-in: 27 days; Double-blind: 12 weeks | To examine the efficacy of transdermal buprenorphine for reducing the interference of pain in physical and emotional functioning | – | Transdermal buprenorphine significantly reduced pain and the interference of pain in physical and emotional functioning (p<0.05) compared with placebo | – |

| Yarlas (2016)59 | Chronic low back pain | Trial I: 10 or 20 µg/h; Trial II: 20 µg/h; opioid-experienced | Trial I: placebo Trial II: 5 µg/h transdermal buprenorphine | Trial I: run-in: 27 days; double-blind: 12 weeks Trial II: run-in: 21 days; double-blind: 12 weeks | To evaluate the impact of transdermal buprenorphine on sleep outcomes | – | Transdermal buprenorphine significantly improved sleep quality and disturbance (p<0.05) through pain reduction compared with the respective controls | – |

| Breivik (2010)32 | Osteoarthritis | 5–10 or 20 µg/h + NSAID or COX-2 inhibitor | Placebo | Double-blind: 6 months | To study the efficacy and tolerability of buprenorphine added to an NSAID or coxib regimen | Nausea, dizziness, constipation, vomiting, and application site dermatitis and pruritus | Daytime movement-related pain decreased significantly (p=0.029) compared with placebo; change in the WOMAC pain score was not statistically significant | Transdermal buprenorphine was well tolerated |

| James (2010)58 | Osteoarthritis | 5, 10, or 20 µg/h | 200 or 400 µg sublingual buprenorphine | Titration: 21 days; Double-blind: 28 days | To compare the efficacy and tolerability of 7-day low-dose transdermal buprenorphine with that of sublingual buprenorphine | Nausea, dizziness, vomiting, somnolence, headache, constipation, asthenia | Transdermal and sublingual buprenorphine were both effective analgesics that enhanced QoL | Transdermal buprenorphine was better tolerated than sublingual buprenorphine |

| Karlsson (2009)38 | Osteoarthritis | 5, 10, or 20 µg/h | 75, 100, 150, or 200 mg/2xd prolonged-release tramadol tablets | Open-label: 12 weeks | To compare the efficacy and safety of transdermal buprenorphine with that of prolonged-release tramadol tablets | Nausea, constipation, dizziness, pain, hyperhidrosis, fatigue, vertigo, and headache | Transdermal buprenorphine was non-inferior in providing efficacious analgesia and improving sleep quality compared with tramadol | Low-dose buprenorphine was well tolerated |

| Karlsson (2014)37 | Osteoarthritis; elderly | 5–40 µg/h | Age comparator; 50–60 vs ≥75 years | Open-label: 12 weeks | To verify the efficacy and safety of transdermal buprenorphine in a clinical setting | Constipation, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, nasopharyngitis, dizziness, headache, somnolence, and application site erythema and pruritus | Regardless of age, transdermal buprenorphine resulted in significant improvements in pain (p<0.0001), reduction in sleep disturbance (p<0.0001), and overall health (p<0.05) | Tolerability was demonstrated regardless of age |

| Ripa (2012)47 | Osteoarthritis; opioid-experienced (Vicodin) | 10 or 20 µg/h | – | Run-in: 7 days; Double-blind: 14 days | To evaluate continued pain control and tolerability when converting patients from hydrocodone/acetaminophen to transdermal buprenorphine | Nausea and application site pruritus | Analgesia, function, and sleep quality were all maintained in patients transitioning from Vicodin to transdermal buprenorphine, and patient satisfaction ratings were positive | Converting from Vicodin to transdermal buprenorphine resulted in acceptable tolerability |

| Pace (2007)45 | Chronic malignant pain | 35 µg/h | 60 mg/d sustained-release morphine | Open-label: 8 weeks | To evaluate the analgesic activity of transdermal buprenorphine vs that of sustained-release morphine | Vertigo, drowsiness, headache, and nausea | Transdermal buprenorphine significantly improved pain (p=0.01), mental health (p=0.03), and vitality (p=0.001) compared with morphine, with positive effects on QoL | Transdermal buprenorphine was better tolerated than morphine |

| Leng (2015)39 | Musculoskeletal pain | 5, 10, or 20 µg/h | 100–400 mg/d tramadol tablets | Double-blind: 8 weeks | To investigate the clinical effectiveness and safety of transdermal buprenorphine compared with that of sustained-release tramadol | Dizziness, nausea, application site erythema, and vomiting | Both transdermal buprenorphine and tramadol significantly reduced pain (p<0.001) compared with baseline, with no significant differences observed between the two groups | Transdermal buprenorphine was well tolerated |

Notes: If not specified, patients in each study were considered opioid naive.

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2 enzyme; IR, immediate-release; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OLE, open-label extension; QoL, quality of life; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

All 12 studies of general chronic pain demonstrated the efficacy of transdermal buprenorphine in pain relief, including 2 (17%) studies assessing an elderly population.31,33,36,40–42,48–52,55 Of these, 4 (33%) studies also observed various quality of life parameters, with all 4 showing improvements in general quality of life, sleep duration, and/or need for breakthrough analgesia.31,33,50,52 All 12 of these studies also found transdermal buprenorphine to be well tolerated in the treatment of general chronic pain.31,33,36,40–42,48–52,55

All of the 15 studies examining chronic low back pain (10 studies) or osteoarthritis pain (5 studies) demonstrated effective pain relief for transdermal buprenorphine, including 1 osteoarthritis study that examined solely elderly populations.14,34,35,37,38,43,44,46,47,53,54,56–59 These studies also examined parameters associated with quality of life, and all 15 demonstrated improvements in activities of daily living (lifting, bending, working), sleep, and/or physical and mental health in response to treatment with transdermal buprenorphine.14,34,35,37,38,43,44,46,47,53,54,56–59 Safety was also examined in 5 (50%) chronic low back pain studies and in each osteoarthritis study, and buprenorphine was generally well tolerated in patients with chronic low back and osteoarthritis pain.14,34,35,37,38,46,47,53,54,58

Similarly, the single study that examined chronic malignant pain found transdermal buprenorphine was well tolerated, improved pain relief, and enhanced mental health and vitality, with overall positive effects on quality of life.45 The study of transdermal buprenorphine on musculoskeletal pain observed pain reduction and also concluded that transdermal buprenorphine was well tolerated.39

Regarding the 3 studies that utilized analgesic comparators, 1 compared the safety and efficacy of buprenorphine with that of morphine and 2 with tramadol. In patients with chronic malignant pain, transdermal buprenorphine significantly improved pain (p=0.01), mental health (p=0.03), and vitality (p=0.001) compared with morphine and was better tolerated for chronic pain management.45 In patients with chronic musculoskeletal or osteoarthritis pain, buprenorphine was statistically noninferior to sustained-release tramadol, with the incidence of adverse events being comparable between the two groups.38,39

Although the measure of pain intensity varied among these studies depending on the type of chronic pain being assessed, in each case, the authors proposed utility for transdermal buprenorphine in maintaining, reducing, or providing relief from pain and/or enhancing the quality of life of patients with chronic pain.31–57 In each of the 24 studies that also assessed safety, transdermal buprenorphine was considered well tolerated.31–42,45–55,58 The most commonly reported adverse events in transdermal buprenorphine clinical trials were nausea, headache, application site pruritus, dizziness, constipation, somnolence, vomiting, application site erythema, dry mouth, and application site rash.23

Buccal Formulation

The safety and efficacy of buprenorphine buccal film has been studied in opioid-experienced and opioid-naive patients with chronic low back pain and in patients with general chronic pain (Table 2).26,60–62 Four clinical studies were identified with the search criteria used here; 1 was a 7-day crossover study, 2 were 12-week double-blind studies, and 1 was a 48-week long-term safety study. The doses of buprenorphine buccal film ranged from 75 to 900 µg/12h.60–62

Table 2.

Summary Of Buprenorphine Buccal Film Clinical Studies

| First Author (Year) | Population | Dose | Comparator | Duration | Primary Objective | Adverse Events ≥10% | Efficacy Results | Safety Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gimbel (2016)26 | Chronic low back pain; opioid-experienced (30 to 160 mg/d MSE) | 150–900 µg/12h | Placebo | Titration phase: up to 8 weeks Double-blind: 12 weeks | To evaluate the safety and efficacy of buprenorphine buccal film | Titration phase: nausea Double-blind: none reported | Buprenorphine buccal film significantly reduced mean pain scores (p<0.001) compared with placebo | Buprenorphine buccal film was generally well tolerated |

| Hale (2017)60 | Chronic low back pain; de novo or rollover (opioid-experienced) | 150–900 µg/12h | – | Titration phase: up to 6 weeks Long-term phase: up to 48 weeks | To evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of buprenorphine buccal film | Titration phase: nausea Long-term: none reported | Buprenorphine buccal film demonstrated efficacy in the long-term management of chronic pain | Buprenorphine buccal film was well tolerated in the long-term management of chronic pain |

| Rauck (2016)61 | Chronic low back pain | 75–450 µg/12h | Placebo | Titration phase: up to 8 weeks Double-blind: 12 weeks | To evaluate buprenorphine buccal film in the management of chronic low back pain | Titration phase: nausea and constipation Double-blind: nausea | Buprenorphine buccal film significantly reduced mean pain scores (p=0.0012) compared with placebo | Buprenorphine buccal film was generally well tolerated |

| Webster (2016)62 | General chronic pain; opioid-experienced and dependent (≥80 but ≤220 mg/d MSE) | 300 or 450 µg/12h | Morphine sulfate or oxycodone HCl (≥80 but ≤220 mg/d MSE) | Double-blind crossover: 7–16 days | To assess the transition from a full µ-OR agonist to buprenorphine buccal film without inducing withdrawal or impacting analgesic efficacy | Headache, drug withdrawal syndrome, and vomiting | Switching to buprenorphine buccal film from a full µ-opioid receptor agonist at ~50% the dose did not increase opioid withdrawal or result in significant differences in pain control | Switching to a 50% MSE dose of buprenorphine buccal film was comparable in safety and tolerability to reducing the MSE dose to 50% of the patient’s current therapy |

Notes: If not specified, patients in each study were considered opioid-naive.

Abbreviations: HCl, hydrochloride; MSE, morphine sulfate equivalent; OR, opioid receptor.

All four studies found that buprenorphine buccal film relieved pain or maintained pain relief.26,60–62 Nausea, constipation, headache, vomiting, fatigue, dizziness, somnolence, diarrhea, dry mouth, and upper respiratory tract infection were the most common adverse reactions reported in clinical trials, and buprenorphine buccal film was deemed generally well tolerated in each study.26,60–62 In addition, patient compliance in these studies was high, as indicated by the high number of completers and subsequent continuation in the long-term safety study.26,60–62

Discussion

The Clinical Efficacy Of Buprenorphine In Chronic Pain

Of the buprenorphine formulations currently approved by the FDA for the management of chronic pain, the transdermal formulation has been the most extensively studied, likely because of its indication and length of time on the market.23 The ability of transdermal buprenorphine to provide effective pain relief has been demonstrated in a variety of clinical studies assessing an array of chronic pain types, and patient compliance tends to be high because of ease of use.31–57,63 Three of the transdermal buprenorphine trials assessed here utilized opioid comparators, and the results of these studies indicated superiority to morphine in relieving chronic malignant pain or noninferiority to tramadol for osteoarthritis or musculoskeletal pain.38,39,45 In addition, a phase IV real-world clinical trial demonstrated that the analgesic efficacy of transdermal buprenorphine in patients with chronic malignant pain was comparable to that of the Schedule II opioids morphine, oxycodone, and fentanyl.64 In a meta-analysis of clinical trials, transdermal buprenorphine was also found to provide pain relief similar to that of transdermal fentanyl.65 Transdermal buprenorphine has thus been clinically shown to be effective in managing chronic pain in a manner similar to that of the Schedule II opioids morphine, oxycodone, and fentanyl.

Buprenorphine buccal film is a relatively new formulation, and as a result, few clinical studies have been published.24 This formulation showed analgesic efficacy in all of the currently available studies, and the efficacy data in opioid-naive patients are comparable with those observed in studies of the Schedule II opioid oxymorphone;61,66 however, a head-to-head study is needed for direct comparison. A high level of patient compliance has been observed with buprenorphine buccal film, as indicated by the high percentages of completers and those who continued in a long-term safety study.26,60,61 Current clinical data also support buprenorphine buccal film as an effective analgesic in patients with chronic pain.

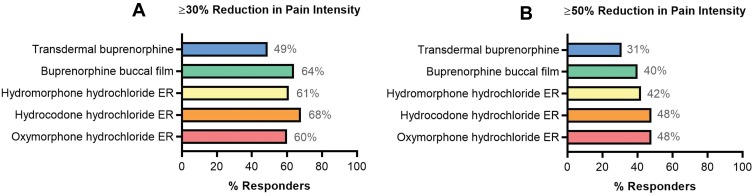

A total of 14% of chronic pain patients discontinued transdermal buprenorphine because of lack of efficacy compared with 5% who discontinued buprenorphine buccal film for the same reason.23,26,60,61 In a responder analysis of ≥30% or ≥50% reduction in pain intensity in opioid-experienced patients, compared with transdermal buprenorphine efficacy, the efficacy of buprenorphine buccal film was more similar to that of full μ-opioid receptor agonists, including hydromorphone hydrochloride ER, hydrocodone hydrochloride ER, and oxymorphone hydrochloride ER (Figure 2).26,53,67–70 However, head-to-head trials are needed to substantiate any differences in efficacy given variations in trial methodology (ie, study design, patient characteristics, use of rescue medications, and methodology used for the imputation of missing data). Nonetheless, current clinical data support the use of buprenorphine for effective chronic pain management with efficacy potentially similar to that of full μ-opioid receptor agonists.

Figure 2.

Responder analysis: similar trials of opioids in opioid-experienced chronic pain populations. Compared with the efficacy data for transdermal buprenorphine (20 µg/h),53 buprenorphine buccal film (150–900 µg/12h)26 had more similar efficacy results to studies of the Schedule II opioids hydromorphone hydrochloride ER (12–64 mg),67 hydrocodone hydrochloride ER (20–100 mg/12h),69 and oxymorphone hydrochloride ER (20–260 mg)70 assessed by ≥30% (A) and ≥50% (B) reduction in pain intensity.

Abbreviation: ER, extended-release.

To our knowledge, there are no clinical trials of buccal buprenorphine film for acute pain, but transdermal buprenorphine has proven efficacy in the treatment of postsurgical acute pain.71–76 Future studies may provide more information regarding additional uses for buprenorphine in pain management; however, these formulations are not currently FDA approved for acute pain treatment.

The Safety Of Buprenorphine In Chronic Pain

The associated risks of abuse and addiction potential, along with the prominent adverse effects of constipation and respiratory depression, limit the use of full μ-opioid receptor agonists for the management of chronic pain.26 The frequency of constipation with ER full μ-opioid receptor agonists has reportedly ranged from 8% to 31%, compared with 4% for buprenorphine buccal film and 13% for transdermal buprenorphine.28,29,70,77–82 In a post-marketing surveillance study, 128 (1%) of 13,179 patients receiving transdermal buprenorphine experienced constipation.63 When constipation is a concern, buprenorphine may be a more suitable treatment than other opioids.

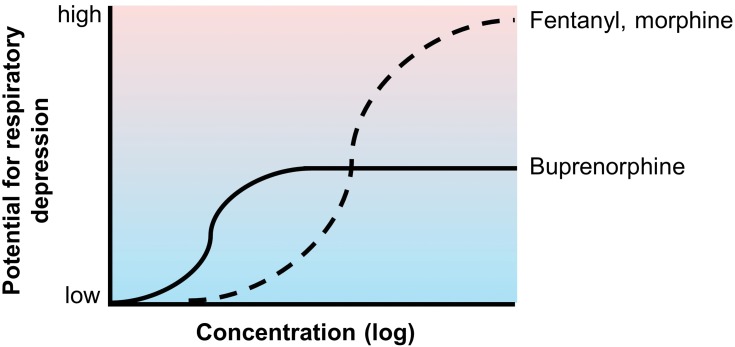

In clinical studies, the incidence of respiratory depression with systemic or spinal opioids ranged from 1% to 11%.23 A post-marketing survey of 1005 patients receiving transdermal fentanyl reported respiratory depression in 8 (0.8%) patients.83 Intravenous buprenorphine was shown to exhibit a ceiling effect on respiratory depression at higher doses, unlike morphine and fentanyl, which have a dose-proportional impact on respiratory depression (Figure 3).84,85 This finding is consistent with a post-marketing survey of 13,179 patients receiving treatment with transdermal buprenorphine, in which respiratory depression was reported in 1 (0.01%) patient, approximately 80 times less than the incidence with transdermal fentanyl. No cases of respiratory depression have been reported in currently available buprenorphine buccal film studies.26,60,61 In addition, a panel of experts reviewing opioid pharmacology concluded that buprenorphine was the only opioid to exhibit a ceiling effect on respiratory depression.86 Buprenorphine also has a lower risk for abuse potential than Schedule II opioids, hence its Schedule III classification by the DEA.11,87 The risks of drug dependence and analgesic tolerance were also lower for buprenorphine than for Schedule II full μ-opioid receptor agonists.87–89

Figure 3.

Conceptual representation of buprenorphine’s ceiling effect on respiratory depression. Unlike the full μ-opioid receptor agonists fentanyl and morphine, buprenorphine exhibits a ceiling effect on respiratory depression.84,85 The low incidence of buprenorphine-associated respiratory depression has been observed clinically.26,60,61,63

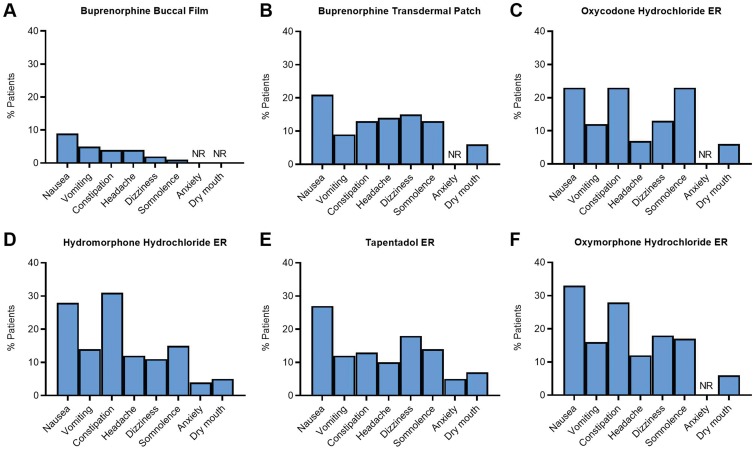

Although both transdermal buprenorphine and buprenorphine buccal film have been well tolerated in clinical studies and have additional safety benefits compared with full μ-opioid receptor agonists, the buccal formulation has the additional advantage of reducing delivery site irritation compared with the transdermal patch. Application site reactions occurred in 1534 (23%) of the 6566 patients treated with transdermal buprenorphine,90 whereas these events have not been reported with the buccal formulation. In addition, 23% of patients discontinued open-label titration with transdermal buprenorphine because of adverse events, compared with 12.5% of patients taking buprenorphine buccal film.26,29,61 When the adverse events reported in clinical trials of transdermal buprenorphine and buprenorphine buccal film were compared with those associated with ER Schedule II opioids, patients treated with buprenorphine buccal film were less likely to experience an adverse reaction in response to treatment (Figure 4).54,61,66 Buprenorphine was well tolerated in patients with chronic pain, while also exhibiting a favorable safety profile compared with full μ-opioid receptor agonists, and the buccal film may confer additional safety advantages compared with the transdermal patch. However, some patients may experience adhesion issues with buprenorphine buccal film.

Figure 4.

Safety analysis: adverse reactions reported in clinical trials of buprenorphine formulations and common Schedule II opioids for chronic pain. The percentage of patients who reported adverse reactions in clinical trials for buprenorphine buccal film (A)28 is lower than those reported for the buprenorphine transdermal patch (B),29 oxycodone hydrochloride ER (C),79 hydromorphone hydrochloride ER (D),77 tapentadol ER (E),81 and oxymorphone hydrochloride ER (F).70

Abbreviations: ER, extended-release; NR, not reported.

Regarding post-marketing experiences, the FDA Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS) Public Dashboard received 314 adverse events reports for buprenorphine buccal film and 26,531 for transdermal buprenorphine from 2016 to March 31, 2019. A total of 73 (23.2%) people reported drug ineffectiveness for buprenorphine buccal film vs 603 (2.3%) people for transdermal buprenorphine; 22 (7.0%) people reported product adhesion issues for buprenorphine buccal film vs 626 (2.4%) people for transdermal buprenorphine. However, this discrepancy may be due to the large variation in numbers of reports, potentially because duplicate reports are being filed in the FAERS system. In addition, data on drug exposure, concomitant medication use, titration to effect, proper use, and suspected causality are not provided in the database, nor is the total number of patients treated with a particular drug. As such, these data alone cannot be used to estimate the incidence of reactions reported or to produce an accurate comparison across drugs.

The Clinical Utility Of Buprenorphine In Chronic Pain Management

Buprenorphine is suitable for use in multiple patient populations. Buprenorphine can be used in patients with a dual diagnosis of chronic pain and opioid use disorder, those requiring concomitant medications (as fewer interactions may occur with other drugs), those with renal or hepatic impairment, and in the elderly.86 The use of buprenorphine in patients with cardiac conditions or concomitant use with antiarrhythmic agents was initially a concern, as therapeutic doses were thought to prolong the QT interval.23 Studies have since concluded that no clinically significant prolongation in the QT interval is observed within therapeutic dose ranges for various buprenorphine formulations.34,91–96 Buprenorphine also has additional benefits in that it is not immunosuppressive,23,97 does not negatively impact the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal pathway,98–100 and reduces anxiety and depression.101–103

Before an opioid therapy for chronic pain management is started or switched, risks and benefits should be weighed on the basis of the patient’s needs. There appears to be a general improvement in the risk-benefit ratio with buprenorphine compared with full μ-opioid receptor agonists,60 which may make it a favorable first-line therapy for chronic pain management when nonopioid analgesics are ineffective.104 In the United States, transdermal buprenorphine patches are available in 5-, 7.5-, 10-, 15-, and 20-µg/h dosages,23 and buprenorphine buccal film is available in higher strengths, including 75, 150, 300, 450, 600, 750, and 900 µg.24 In opioid-experienced patients, initiation depends on prior morphine sulfate equivalent doses. Although buprenorphine is no longer listed in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s morphine milligram equivalent chart because it was deemed unlikely to be associated with overdose in the same dose-dependent manner as Schedule I or Schedule II opioids, the prescribing information for transdermal buprenorphine and buprenorphine buccal film contains conversion strategies for opioid-experienced patients.23,24,105,106

Conclusion

Buprenorphine is an atypical opioid that demonstrates efficacy similar to that of Schedule II full μ-opioid receptor agonists in managing chronic pain while exhibiting a favorable tolerability profile, including the reduced likelihood of abuse potential and respiratory depression. Buprenorphine has additional clinical advantages, including use in multiple patient populations, such as the elderly and those with renal or hepatic impairment, and reduced likelihood of constipation and withdrawal. Regarding the formulations indicated for chronic pain, buprenorphine buccal film has higher bioavailability, has more dose ranges, and appears to be more efficacious and tolerable than the transdermal formulation on the basis of responder and safety analyses of currently available, although limited, clinical studies. However, some patients may experience adhesion issues with the buccal film, although this was not commonly reported in clinical trials. To gain further insight into the most advantageous treatment option for chronic pain, well-controlled head-to-head trials are warranted for comparisons of buprenorphine with Schedule II opioids and of transdermal buprenorphine with buprenorphine buccal film. Nonetheless, current clinical and long-term safety data support the use of buprenorphine over full μ-opioid receptor agonists for the effective and preferential treatment of chronic pain at a critical time when safer and less addictive treatments are needed.

Acknowledgments

Editorial support was provided by MedLogix Communications, LLC, in cooperation with the authors, and was sponsored by BioDelivery Sciences International, Inc. This review was sponsored by BioDelivery Sciences International, Inc.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed to the conception and design of the manuscript and the analysis and interpretation of data, critically revised the manuscript for scientific accuracy and intellectual content, approved the final manuscript for publication, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

JVP has served as a consultant/speaker and researcher for Daiichi Sankyo, US WorldMeds, BioDelivery Sciences International, Inc, Salix, Enalare, and Neumentum. He also reports non-financial supports from BioDelivery Sciences International, Inc., during the conduct of the study and outside the submitted work. RBR was a previous employee of Johnson & Johnson, currently has academic affiliations (Temple University, University of Arizona), consults for multiple pharmaceutical companies regarding the discovery and development of opioid and nonopioid analgesics, and is a principal investigator for two (nonopioid) analgesic drug discovery/development companies, CaRafe Drug Innovation and Neumentum. RBR also reports personal fees from BioDelivery Sciences International, Inc., NEMA Research, and partnership or stock options from CaRafe Drug Innovation, Neumentum, and Enalare outside the submitted work. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1001–1007. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6736a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleiber B, Jain S, Trivedi MH. Depression and pain: implications for symptomatic presentation and pharmacological treatments. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005;2(5):12–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute on Drug Abuse. Opioid overdose crisis; 2019. Available from: https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-overdose-crisis Accessed April4, 2019.

- 4.Davis MP, Pasternak G, Behm B. Treating chronic pain: an overview of clinical studies centered on the buprenorphine option. Drugs. 2018;78(12):1211–1228. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0953-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drug Enforcement Administration. Mid-level practitioners authorization by state. Available from: https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drugreg/practioners/mlp_by_state.pdf Accessed April4, 2019.

- 6.Whitemore and Whisenant. Opioid prescribing limits across the states; 2019. Available from: https://www.pharmacytimes.com/contributor/marilyn-bulloch-pharmd-bcps/2019/02/opioid-prescribing-limits-across-the-states Accessed April4, 2019.

- 7.Dowell D, Haegerich T, Chou R. No shortcuts to safer opioid prescribing. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2285–2287. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1904190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis JW. Ring C-bridged derivatives of thebaine and oripavine. Adv Biochem Psychopharmacol. 1974;8:123–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khanna IK, Pillarisetti S. Buprenorphine: an attractive opioid with underutilized potential in treatment of chronic pain. J Pain Res. 2015;8:859–870. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S85951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell ND, Lovell AM. The history of the development of buprenorphine as an addiction therapeutic. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1248:124–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06352.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drug Enforcement Administration Diversion Control Division. Rescheduling of buprenorphine from Schedule V to Schedule III; 2002. Available from: https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/fed_regs/rules/2002/fr1007.htm Accessed March20, 2019.

- 12.Butler S. Buprenorphine: clinically useful but often misunderstood. Scand J Pain. 2013;4(3):148–152. doi: 10.1016/j.sjpain.2013.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raffa RB, Haidery M, Huang HM, et al. The clinical analgesic efficacy of buprenorphine. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2014;39(6):577–583. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breivik H. Buprenorphine—the ideal drug for more clinical indications for an opioid? Scand J Pain. 2013;4(3):146–147. doi: 10.1016/j.sjpain.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zubieta J, Greenwald MK, Lombardi U, et al. Buprenorphine-induced changes in mu-opioid receptor availability in male heroin-dependent volunteers: a preliminary study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23(3):326–334. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00110-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jasinski DR, Pevnick JS, Griffith JD. Human pharmacology and abuse potential of the analgesic buprenorphine: a potential agent for treating narcotic addiction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35(4):501–516. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770280111012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yassen A, Olofsen E, Romberg R, Sarton E, Danhof M, Dahan A. Mechanism-based pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of the antinociceptive effect of buprenorphine in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(6):1232–1242. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200606000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pergolizzi J, Aloisi AM, Dahan A, et al. Current knowledge of buprenorphine and its unique pharmacological profile. Pain Pract. 2010;10(5):428–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00378.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothman RB, Gorelick DA, Heishman SJ, et al. An open-label study of a functional opioid kappa antagonist in the treatment of opioid dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2000;18(3):277–281. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(99)00074-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmadi J, Jahromi MS, Ehsaei Z. The effectiveness of different singly administered high doses of buprenorphine in reducing suicidal ideation in acutely depressed people with co-morbid opiate dependence: a randomized, double-blind, clinical trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):462. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-2843-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stein C, Machelska H. Modulation of peripheral sensory neurons by the immune system: implications for pain therapy. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63(4):860–881. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Likar R. Transdermal buprenorphine in the management of persistent pain: safety aspects. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2006;2(1):115–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis MP. Twelve reasons for considering buprenorphine as a frontline analgesic in the management of pain. J Support Oncol. 2012;10(6):209–219. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2012.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.United States Health and Human Services. HHS acting secretary declares public health emergency to address national opioid crisis. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2017/10/26/hhs-acting-secretary-declares-public-health-emergency-address-national-opioid-crisis.html Accessed January24, 2019.

- 25.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Pain management best practices inter-agency task force report: updates, gaps, inconsistencies, and recommendations; 2019. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/ash/advisory-committees/pain/reports/index.html Accessed September17, 2019.

- 26.Gimbel J, Spierings EL, Katz N, Xiang Q, Tzanis E, Finn A. Efficacy and tolerability of buccal buprenorphine in opioid-experienced patients with moderate to severe chronic low back pain: results of a phase 3, enriched enrollment, randomized withdrawal study. Pain. 2016;157(11):2517–2526. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuhlman JJ Jr., Lalani S, Magluilo J Jr., Levine B, Darwin WD. Human pharmacokinetics of intravenous, sublingual, and buccal buprenorphine. J Anal Toxicol. 1996;20(6):369–378. doi: 10.1093/jat/20.6.369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Belbuca® (buprenorphine buccal film) [prescribing information]. Raleigh, NC: BioDelivery Sciences International, Inc.; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Butrans® (buprenorphine transdermal system) [prescribing information]. Stamford, CT: Purdue Pharma L.P.; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mendelson J, Upton RA, Everhart ET, Jacob P 3rd, Jones RT. Bioavailability of sublingual buprenorphine. J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;37(1):31–37. doi: 10.1177/009127009703700106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Böhme K. Buprenorphine in a transdermal therapeutic system: a new option. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21(1 Suppl):S13–S16. doi: 10.1007/s100670200031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breivik H, Ljosaa TM, Stengaard-Pedersen K, et al. A 6-months, randomised, placebo-controlled evaluation of efficacy and tolerability of a low-dose 7-day buprenorphine transdermal patch in osteoarthritis patients naïve to potent opioids. Scand J Pain. 2010;1(3):122–141. doi: 10.1016/j.sjpain.2010.05.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gianni W, Madaio AR, Ceci M, et al. Transdermal buprenorphine for the treatment of chronic noncancer pain in the oldest old. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(4):707–714. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gordon A, Callaghan D, Spink D, et al. Buprenorphine transdermal system in adults with chronic low back pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study, followed by an open-label extension phase. Clin Ther. 2010;32(5):844–860. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gordon A, Rashiq S, Moulin DE, et al. Buprenorphine transdermal system for opioid therapy in patients with chronic low back pain. Pain Res Manage. 2010;15(3):169–178. doi: 10.1155/2010/216725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hakl M. Transdermal buprenorphine in clinical practice: a multicenter, postmarketing study in the Czech Republic, with a focus on neuropathic pain components. Pain Manage. 2012;2(2):169–175. doi: 10.2217/pmt.11.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karlsson J, Söderström A, Augustini BG, Berggren AC. Is buprenorphine transdermal patch equally safe and effective in younger and elderly patients with osteoarthritis-related pain? Results of an age-group controlled study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(4):575–587. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2013.873714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karlsson M, Berggren AC. Efficacy and safety of low-dose transdermal buprenorphine patches (5, 10, and 20 μg/h) versus prolonged-release tramadol tablets (75, 100, 150, and 200 mg) in patients with chronic osteoarthritis pain: a 12-week, randomized, open-label, controlled, parallel-group noninferiority study. Clin Ther. 2009;31(3):503–513. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leng X, Li Z, Lv H, et al. Effectiveness and safety of transdermal buprenorphine versus sustained-release tramadol in patients with moderate to severe musculoskeletal pain: an 8-week, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, multicenter, active-controlled, noninferiority study. Clin J Pain. 2015;31(7):612–620. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Likar R, Kayser H, Sittl R. Long-term management of chronic pain with transdermal buprenorphine: a multicenter, open-label, follow-up study in patients from three short-term clinical trials. Clin Ther. 2006;28(6):943–952. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Likar R, Lorenz V, Korak-Leiter M, Kager I, Sittl R. Transdermal buprenorphine patches applied in a 4-day regimen versus a 3-day regimen: a single-site, phase III, randomized, open-label, crossover comparison. Clin Ther. 2007;29(8):1591–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Likar R, Vadlau EM, Breschan C, Kager I, Korak-Leiter M, Ziervogel G. Comparable analgesic efficacy of transdermal buprenorphine in patients over and under 65 years of age. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(6):536–543. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181673b65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller K, Yarlas A, Wen W, et al. Buprenorphine transdermal system and quality of life in opioid-experienced patients with chronic low back pain. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14(3):269–277. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2013.767331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller K, Yarlas A, Wen W, et al. The impact of buprenorphine transdermal delivery system on activities of daily living among patients with chronic low back pain: an application of the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(12):1015–1022. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pace MC, Passavanti MB, Grella E, et al. Buprenorphine in long-term control of chronic pain in cancer patients. Front Biosci. 2007;12(4):1291–1299. doi: 10.2741/2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pota V, Barbarisi M, Sansone P, et al. Combination therapy with transdermal buprenorphine and pregabalin for chronic low back pain. Pain Manage. 2012;2(1):23–31. doi: 10.2217/pmt.11.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ripa SR, McCarberg BH, Munera C, Wen W, Landau CJ. A randomized, 14-day, double-blind study evaluating conversion from hydrocodone/acetaminophen (Vicodin) to buprenorphine transdermal system 10 μg/h or 20 μg/h in patients with osteoarthritis pain. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13(9):1229–1241. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2012.667073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Serpell M, Tripathi S, Scherzinger S, Rojas-Farreras S, Oksche A, Wilson M. Assessment of transdermal buprenorphine patches for the treatment of chronic pain in a UK observational study. Patient. 2016;9(1):35–46. doi: 10.1007/s40271-015-0151-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silverman S, Raffa RB, Cataldo MJ, Kwarcinski M, Ripa SR. Use of immediate-release opioids as supplemental analgesia during management of moderate-to-severe chronic pain with buprenorphine transdermal system. J Pain Res. 2017;10:1255–1263. doi: 10.2147/JPR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sittl R, Griessinger N, Likar R. Analgesic efficacy and tolerability of transdermal buprenorphine in patients with inadequately controlled chronic pain related to cancer and other disorders: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Ther. 2003;25(1):150–168. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(03)90019-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Skvarc NK. Transdermal buprenorphine in clinical practice: results from a multicenter, noninterventional postmarketing study in Slovenia. Pain Manag. 2012;2(2):177–183. doi: 10.2217/pmt.11.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sorge J, Sittl R. Transdermal buprenorphine in the treatment of chronic pain: results of a phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Ther. 2004;26(11):1808–1820. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2004.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steiner D, Munera C, Hale M, Ripa S, Landau C. Efficacy and safety of buprenorphine transdermal system (BTDS) for chronic moderate to severe low back pain: a randomized, double-blind study. J Pain. 2011;12(11):1163–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steiner DJ, Sitar S, Wen W, et al. Efficacy and safety of the seven-day buprenorphine transdermal system in opioid-naïve patients with moderate to severe chronic low back pain: a enriched, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(6):903–917. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vondráčková D. Transdermal buprenorphine in clinical practice: a multicenter, noninterventional postmarketing study in the Czech Republic. Pain Manage. 2012;2(2):163–168. doi: 10.2217/pmt.11.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yarlas A, Miller K, Wen W, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of the impact of the 7-day buprenorphine transdermal system on health-related quality of life in opioid-naïve patients with moderate-to-severe chronic low back pain. J Pain. 2013;14(1):14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yarlas A, Miller K, Wen W, et al. Buprenorphine transdermal system compared with placebo reduces interference in functioning for chronic low back pain. Postgrad Med. 2015;127(1):38–45. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2014.992715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.James IG, O’Brien CM, McDonald CJ. A randomized, double-blind, double-dummy comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of low-dose transdermal buprenorphine (BuTrans seven-day patches) with buprenorphine sublingual tablets (Temgesic) in patients with osteoarthritis pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(2):266–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yarlas A, Miller K, Wen W, et al. Buprenorphine transdermal system improves sleep quality and reduces sleep disturbance in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic low back pain: results from two randomized controlled trials. Pain Pract. 2016;16(3):345–358. doi: 10.1111/papr.2016.16.issue-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hale M, Urdaneta V, Kirby MT, Xiang Q, Rauck R. Long-term safety and analgesic efficacy of buprenorphine buccal film in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic pain requiring around-the-clock opioids. J Pain Res. 2017;10:233–240. doi: 10.2147/JPR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rauck RL, Potts J, Xiang Q, Tzanis E, Finn A. Efficacy and tolerability of buccal buprenorphine in opioid-naive patients with moderate to severe chronic low back pain. Postgrad Med. 2016;128(1):1–11. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2016.1128307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Webster L, Gruener D, Kirby T, Xiang Q, Tzanis E, Finn A. Evaluation of the tolerability of switching patients on chronic full μ-opioid agonist therapy to buccal buprenorphine. Pain Med. 2016;17(5):899–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Griessinger N, Sittl R, Likar R. Transdermal buprenorphine in clinical practice: a post-marketing surveillance study in 13,179 patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(8):1147–1156. doi: 10.1185/030079905X53315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Corli O, Floriani I, Roberto A, et al. Are strong opioids equally effective and safe in the treatment of chronic cancer pain? A multicenter randomized phase IV ‘real life’ trial on the variability of response to opioids. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(6):1107–1115. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wolff RF, Aune D, Truyers C, et al. Systematic review of efficacy and safety of buprenorphine versus fentanyl or morphine in patients with chronic moderate to severe pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(5):833–845. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.678938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Katz N, Rauck R, Ahdieh H, et al. A 12-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial assessing the safety and efficacy of oxymorphone extended release for opioid-naive patients with chronic low back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(1):117–128. doi: 10.1185/030079906X162692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hale M, Khan A, Kutch M, Li S. Once-daily OROS hydromorphone ER compared with placebo in opioid-tolerant patients with chronic low back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(6):1505–1518. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.484723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hale ME, Ahdieh H, Ma T, Rauck R; Oxymorphone ER Study Group. Efficacy and safety of OPANA ER (oxymorphone extended release) for relief of moderate to severe chronic low back pain in opioid-experienced patients: a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Pain. 2007;8(2):175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rauck RL, Nalamachu S, Wild JE, et al. Single-entity hydrocodone extended-release capsules in opioid-tolerant subjects with moderate-to-severe chronic low back pain: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Pain Med. 2014;15(6):975–985. doi: 10.1111/pme.12377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Opana® ER (oxymorphone HCl extended-release tablets) [prescribing information]. Malvern, PA: Endo Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arshad Z, Prakash R, Gautam S, Kumar S. Comparison between transdermal buprenorphine and transdermal fentanyl for postoperative pain relief after major abdominal surgeries. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(12):UC01–04. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/16327.6917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Desai SN, Badiger SV, Tokur SB, Naik PA. Safety and efficacy of transdermal buprenorphine versus oral tramadol for the treatment of post-operative pain following surgery for fracture neck of femur: a prospective, randomised clinical study. Indian J Anaesth. 2017;61(3):225–229. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_208_16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim HJ, Ahn HS, Nam Y, Chang BS, Lee CK, Yeom JS. Comparative study of the efficacy of transdermal buprenorphine patches and prolonged-release tramadol tablets for postoperative pain control after spinal fusion surgery: a prospective, randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. Eur Spine J. 2017;26(11):2961–2968. doi: 10.1007/s00586-017-5213-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kumar S, Chaudhary AK, Singh PK, et al. Transdermal buprenorphine patches for postoperative pain control in abdominal surgery. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(6):UC05–08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee JH, Kim JH, Kim JH, et al. Efficacy and safety of transdermal buprenorphine versus oral tramadol/acetaminophen in patients with persistent postoperative pain after spinal surgery. Pain Res Manag. 2017;2017:2071494. doi: 10.1155/2017/2071494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xu C, Li M, Wang C, Li H, Liu H. Perioperative analgesia with a buprenorphine transdermal patch for hallux valgus surgery: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. J Pain Res. 2018;11:867–873. doi: 10.2147/JPR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Exalgo® (hydromorphone HCl extended-release tablets) [prescribing information]. Hazelwood, MO: Mallinckrodt; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Duragesic® (fentanyl transdermal system) [prescribing information]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oxycontin® (oxycodone HCl extended-release tablets) [prescribing information]. Stamford, CT: Purdue Pharma L.P.; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zohydro® ER (hydrocodone bitartrate extended-release capsules) [prescribing information]. Morristown, NJ: Pernix Therapeutics, LLC.; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nucynta® ER (tapentadol extended-release tablets) [prescribing information]. Newark, CA: Depomed, Inc; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kadian® (morphine sulfate extended-release capsules) [prescribing information]. Madison, NJ: Allergan USA, Inc.; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Radbruch L, Sabatowski R, Petzke F, Brunsch-Radbruch A, Grond S, Lehmann KA. Transdermal fentanyl for the management of cancer pain: a survey of 1005 patients. Palliat Med. 2001;15(4):309–321. doi: 10.1191/026921601678320296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dahan A, Yassen A, Bijl H, et al. Comparison of the respiratory effects of intravenous buprenorphine and fentanyl in humans and rats. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94(6):825–834. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dahan A, Yassen A, Romberg R, et al. Buprenorphine induces ceiling in respiratory depression but not in analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96(5):627–632. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pergolizzi J, Boger RH, Budd K, et al. Opioids and the management of chronic severe pain in the elderly: consensus statement of an international expert panel with focus on the six clinically most often used World Health Organization Step III opioids (buprenorphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, methadone, morphine, oxycodone). Pain Pract. 2008;8(4):287–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2008.00204.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Walsh SL, Eissenberg T. The clinical pharmacology of buprenorphine: extrapolating from the laboratory to the clinic. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70(2 Suppl):S13–S27. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(03)00056-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Robinson SE. Buprenorphine: an analgesic with an expanding role in the treatment of opioid addiction. CNS Drug Rev. 2002;8(4):377–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2002.tb00235.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Walsh SL, Preston KL, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. Acute administration of buprenorphine in humans: partial agonist and blockade effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;274(1):361–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wen W, Lynch SY, Munera C, Swanton R, Ripa SR, Maibach H. Application site adverse events associated with the buprenorphine transdermal system: a pooled analysis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2013;12(3):309–319. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2013.780025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schmith VD, Curd L, Lohmer LRL, Laffont CM, Andorn A, Young MA. Evaluation of the effects of a monthly buprenorphine depot subcutaneous injection on QT interval during treatment for opioid use disorder. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;106(3):576–584. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.de Jong IM, de Ruiter GS. Buprenorphine as a safe alternative to methadone in a patient with acquired long QT syndrome: a case report. Neth Heart J. 2013;21(5):249–252. doi: 10.1007/s12471-011-0073-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kao DP, Haigney MC, Mehler PS, Krantz MJ. Arrhythmia associated with buprenorphine and methadone reported to the food and drug administration. Addiction. 2015;110(9):1468–1475. doi: 10.1111/add.13013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Poole SA, Pecoraro A, Subramaniam G, Woody G, Vetter VL. Presence or absence of QTc prolongation in buprenorphine-naloxone among youth with opioid dependence. J Addict Med. 2016;10(1):26–33. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Stallvik M, Nordstrand B, Kristensen O, Bathen J, Skogvoll E, Spigset O. Corrected QT interval during treatment with methadone and buprenorphine: relation to doses and serum concentrations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;129(1–2):88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Darpo B, Zhou M, Bai SA, Ferber G, Xiang Q, Finn A. Differentiating the effect of an opioid agonist on cardiac repolarization from micro-receptor-mediated, indirect effects on the QT interval: a randomized, 3-way crossover study in healthy subjects. Clin Ther. 2016;38(2):315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Budd K. Pain management: is opioid immunosuppression a clinical problem? Biomed Pharmacother. 2006;60(7):310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2006.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hallinan R, Byrne A, Agho K, McMahon CG, Tynan P, Attia J. Hypogonadism in men receiving methadone and buprenorphine maintenance treatment. Int J Androl. 2009;32(2):131–139. doi: 10.1111/ija.2009.32.issue-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hallinan R, Byrne A, Agho K, McMahon C, Tynan P, Attia J. Erectile dysfunction in men receiving methadone and buprenorphine maintenance treatment. J Sex Med. 2008;5(3):684–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00702.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Aurilio C, Ceccarelli I, Pota V, et al. Endocrine and behavioural effects of transdermal buprenorphine in pain-suffering women of different reproductive ages. Endocr J. 2011;58(12):1071–1078. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ11-0095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Karp JF, Butters MA, Begley AE, et al. Safety, tolerability, and clinical effect of low-dose buprenorphine for treatment-resistant depression in midlife and older adults. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):e785–e793. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bodkin JA, Zornberg GL, Lukas SE, Cole JO. Buprenorphine treatment of refractory depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;15(1):49–57. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199502000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ahmadi J, Jahromi MS. Anxiety treatment of opioid dependent patients with buprenorphine: a randomized, double-blind, clinical trial. Indian J Psychol Med. 2017;39(4):445–449. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.211765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ballantyne JC. Opioid therapy in chronic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2015;26(2):201–218. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. [Updated April 17, 2019]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html Accessed June10, 2019.

- 106.American Academy of Family Physicians. CDC clarifies opioid guideline dosage thresholds. January 12, 2018. Available from: https://www.aafp.org/news/health-of-the-public/20180112cdcopioidclarify.html Accessed June10, 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Opioid overdose crisis; 2019. Available from: https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-overdose-crisis Accessed April4, 2019.