Abstract

Laminin-γ1 is required for early embryonic development; however, the need for laminin-γ1 synthesis in adulthood is unknown. A global and inducible mouse model of laminin-γ1 deficiency was generated to address this question. Genetic ablation of the Lamc1 gene in adult mice was rapidly lethal. Despite global Lamc1 gene deletion in tamoxifen-induced mutant mice, there was minimal change in total cardiac, pulmonary, hepatic or renal laminin protein. In contrast, laminin-γ1 was significantly depleted in the small intestines, which showed crypt hyperplasia and dissociation of villous epithelium from adjacent mesenchyme. We conclude that the physiologic requirement for laminin-γ1 synthesis in adult mice is dependent on a tissue-specific basal rate of laminin-γ1 turnover that results in rapid depletion of laminin-γ1 in the intestine.

Subject terms: Extracellular matrix, Stem-cell niche

Introduction

Basement membranes are extracellular matrix (ECM) structures consisting of well-organized glycoproteins and glycosaminoglycans. These structures provide cell-scaffolding, facilitate adjacent cell-cell interactions, and bind cell-surface receptors to transmit environmental signals1. The laminin glycoproteins are requisite components of all basement membranes. Laminins are secreted as heterotrimeric glycoproteins, comprised of an α, β, and γ subunit2–4. At the cell surface, these three subunits self-assemble into a heterotrimer, which then forms a network of “ternary nodes”5–12. This is the initiating step in basement membrane formation as well as a structural and biochemical link to cell surface receptors, which in turn transmit survival and proliferative cues to membrane-adjacent cells12,13.

Of the 60 possible laminin heterotrimers, only 16 have been isolated from biological organisms, a majority of which contain the γ1 subunit5,14. Mouse embryos that are globally deficient in laminin-γ1 do not develop past embryonic day 5.5 (E5.5) after fertilization, and there are no reported human cases of complete congenital laminin-γ1 deficiency3,4,15. Embryologic and early post-natal deletion of laminin-γ1 in cell-specific conditional knockout mice has provided information about its function in the developing central and peripheral nervous systems and vasculature16–20. However, SNPs in or adjacent to the human LAMC1 gene that codes for laminin-γ1 have been identified by multiple GWAS studies as genetic risk factors for developing colorectal cancer21–24. Antibodies that react with laminin-γ1 have been detected in subsets of patients with pemphigoid15,25–27 and graft-versus-host disease28, and subepithelial basement membrane laminin-γ1 or laminin-γ1 containing heterotrimers are modified in the colons of patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease25,29–34. However, these observations do not provide a mechanistic link between laminin-γ1 and the relevant clinical disorders, leaving open the question of whether laminin-γ1 expression in adulthood is a regulator of adult physiology. We generated a mouse model for temporal ablation of laminin-γ1 production in order to answer this question.

Results

Temporally controlled deletion of the LAMC1 gene In adult mice reveals organ-specific laminin-γ1 protein turnover

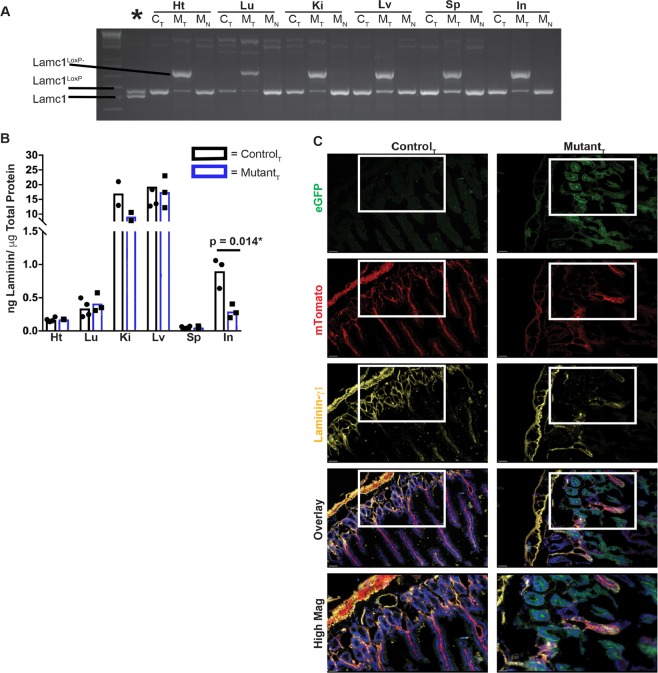

Adult control (LAMC1loxP/loxP) and mutant (UBC-Cre-ERT2; LAMC1loxP/loxP) mice were treated with tamoxifen as described in Methods. Three weeks after the final tamoxifen injection, mice were euthanized. PCR was used to determine the recombination status of the LAMC1loxP gene in heart, lung, liver, kidney, spleen and small intestine samples. The recombined LAMC1loxP PCR-product (LAMC1r) was detected in all tamoxifen-treated mutant samples (MT) and in none of the tamoxifen-treated control samples (CT) (Fig. 1A). PCR of untreated mutant mice (MN) are also included and show no evidence of Lamc1loxP gene recombination.

Figure 1.

Conditional deletion of the Lamc1 gene in adult mice rapidly leads to laminin protein depletion in the small intestine. For (A,B), tissues include heart (Ht), Lung (Lu), Kidney (Ki), Liver (Lv), Spleen (Sp) and Small Intestine (In). (A) Tissue from tamoxifen-treated control (CT), tamoxifen-treated mutant (MT), and untreated mutant (MN) were analyzed by PCR for the presence of wild type Lamc1, Lamc1LoxP, and recombined Lamc1LoxP−. The lane marked * contains tail DNA from a mouse with the genotype Lamc1LoxP/+. (B) Tissue lysates were analyzed by ELISA for total laminin protein concentration. Each data point is the average of two technical replicates from a single animal. (C) Immunofluorescent images of control and mutant small intestine that were probed with antibody against laminin-γ1 (yellow). Endogenous mTomato and eGFP are also shown. DAPI was used to label nuclei (blue). Magnification bars indicate 50 microns (lower magnification) and 10 microns (higher magnification). 10x and 40x with a 1.5 magnifier lenses were used to collect these images. Images are representative of the results obtained from immunofluorescent analysis of 3 tamoxifen-treated control and 4 tamoxifen-treated mutant mice.

A sandwich ELISA was used to quantify the abundance of laminin in equivalent amounts of total protein from heart, lung, kidney, liver, spleen and intestine homogenates (Fig. 1B). In a majority of the organs sampled, the quantity of laminin protein did not significantly differ between tamoxifen-treated control and mutant mice. However, there was a significant reduction in total-laminin protein in the tamoxifen-treated mutant small intestine as compared with control.

The subepithelial laminin in adult intestinal crypts is laminin-211 and in the villi are laminin-332 and laminin-51135,36. Thus, laminin-ɣ1 is the exclusive sub-epithelial gamma-chain in intestine crypts and is a significant contributor to villous laminin. We used frozen tissue sections from control and mutant mice that also expressed the mTomato/eGFP reporter transgene37 to correlate areas of Cre-responsive gene recombination to laminin expression (Fig. 1C). In the absence of Cre recombinase activity, tissues express mTomato, which is lost with recombinase activity and replaced by eGFP expression. Tamoxifen-treated control mice expressed mTomato throughout the muscularis, crypts and villi, and minimal to no eGFP expression. Laminin-γ1 was detected in thin basement membranes surrounding crypts and extending through the duodenal villi. In the tamoxifen-treated mutants, mTomato fluorescence was visible in few villi and portions of the muscularis, while eGFP expression was robust in duodenal crypts villi. Laminin-γ1 immunoreactivity was restricted to mTomato+ villi and mTomato+ muscularis. The basement membranes adjacent to eGFP+ crypts and eGFP+ villi did not retain laminin-γ1 immunoreactivity. This indicates that Lamc1 gene recombination, and thus transition from mTomato to eGFP expression, corresponds with reduced laminin-γ1 protein in the adjacent basement membrane.

To compare Lamc1 transcript abundance in both the epithelial and mesenchymal layers from control and mutant mice, duodenal epithelium was separated from mesenchyme, and RNA from each of the two fractions (epithelial and mesenchymal-enriched) were isolated and analyzed by qRT-PCR for Lamc1 transcript (Table 1). The mesenchyme-enriched fractions from controls had higher Lamc1 transcript levels than the epithelial fraction, and the more significant reduction of transcript was similarly in the mesenchyme of mutant mice. This finding is consistent with previously reported data38. Alternative laminin gamma subunit transcripts (i.e. -γ2 and γ3) were not upregulated in the mesenchyme of Lamc1 knockouts, although the laminin-γ2 transcript was upregulated in the epithelial fraction (Table 1, Fig. 1). Transcripts for α- and β laminin subunits were also compared (Table 1), as were laminin-α4 and laminin-α2 protein immunoreactivity (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Table 1.

RT-PCR analysis of laminin subunit transcripts. * Indicates p < 0.05.

| Control + Tx (±SEM, n) | Mutant + Tx (±SEM, n) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lamc1-Epi | 0.7239 ± 0.1507, n = 5 | 0.4477 ± 0.1047, n = 5 | 0.1708 |

| Lamc1-Mes | 13.12 ± 3.497, n = 9 | 2.984 ± 0.5256, n = 8 | 0.0165* |

| Lamc2-Epi | 0.3355 ± 0.08577, n = 5 | 1.329 ± 0.4057, n = 6 | 0.0570* |

| Lamc2-Mes | 2.237 ± 0.4147, n = 4 | 2.851 ± 1.042, n = 5 | 0.6348 |

| Lamc3-Epi | 0.002878 ± 0.001133, n = 2 | 0.003017 ± 0.001089, n = 2 | ND |

| Lamc3-Mes | 4.646 ± 2.199, n = 5 | 1.664 ± 1.528, n = 3 | ND |

| Lama1-Epi | ND | ND | ND |

| Lama1-Mes | 1.11 ± 0.3783, n = 4 | 1.364 ± 0.6026, n = 5 | 0.7479 |

| Lama2-Epi | 0.02868 ± 0.02555, n = 3 | 0.003025 ± 0.001197, n = 4 | ND |

| Lama2-Mes | 9.874 ± 3.751, n = 6 | 3.778 ± 1.679, n = 5 | 0.2007 |

| Lama3-Epi | 0.2167 ± 0.1197, n = 5 | 0.02989 ± 0.005951, n = 3 | ND |

| Lama3-Mes | 3.022 ± 0.667, n = 5 | 1.71 ± 0.6523, n = 5 | 0.1973 |

| Lama4-Epi | 0.05141 ± 0.01605, n = 4 | 0.4325 ± 0.4176, n = 5 | 0.4476 |

| Lama4-Mes | 25.53 ± 7.401, n = 6 | 5.337 ± 2.731, n = 5 | 0.0424* |

| Lama5-Epi | 0.6793 ± 0.1252, n = 4 | 3.544 ± 2.921, n = 5 | 0.4160 |

| Lama5-Mes | 25.81 ± 8.991, n = 6 | 20.08 ± 12.49, n = 5 | 0.7121 |

| Lamb1-Epi | 0.2012 ± 0.08824, n = 5 | 8.044 ± 7.901, n = 5 | 0.3500 |

| Lamb1-Mes | 43.77 ± 12.29, n = 6 | 28.59 ± 13.01, n = 6 | 0.4160 |

| Lamb2-Epi | 0.1696 ± 0.04572, n = 4 | 0.02179 ± 0.006419, n = 4 | 0.0186 |

| Lamb2-Mes | 21.72 ± 17.39, n = 6 | 3.335 ± 1.125, n = 5 | 0.3644 |

| Lamb3-Epi | 1.006 ± 0.1636, n = 5 | 1.952 ± 0.5264, n = 6 | 0.1494 |

| Lamb3-Mes | 1.805 ± 0.4069, n = 5 | 1.845 ± 0.233, n = 5 | 0.9332 |

Lamc1 gene deletion in adult mice is lethal

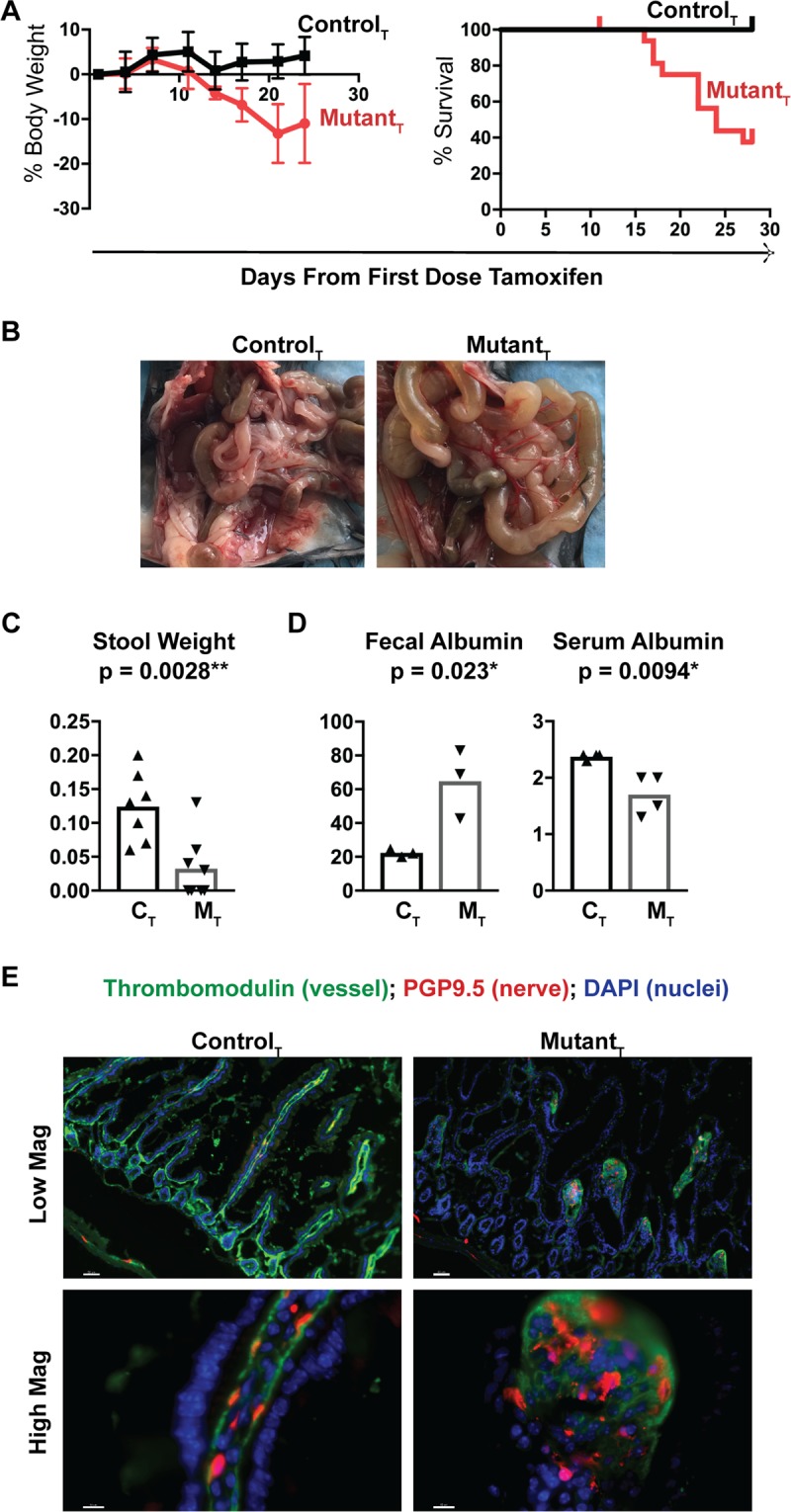

Following tamoxifen administration, mutant and control mice were monitored with serial weight measurements and clinical observation. The control group maintained their body weight, while mutant animals progressively lost weight (Fig. 2A). Tamoxifen-treated mutant mice developed signs of distress, including ruffled fur appearance, hunched posture, lack of grooming behavior, and stunted growth. There was no evidence of overt hindlimb paresis (Supplemental Videos 1 Control & 2 Mutant), such as has been previously described in neuronal and Schwann cell-specific conditional Lamc1 knockout mice16,17. Clinical deterioration and weight loss was quantified using an IACUC-approved health metric scale, and mice falling below institutional acceptable scores were euthanized. This metric of morbidity was used to estimate survival from the first dose of tamoxifen administration (median survival of tamoxifen-treated control mice was unreached, and for tamoxifen-treated mutants was 24 days, p = 0.003; Fig. 2A). Once the time frame for 50 percent lethality was established, remaining control and mutant mice were euthanized. The tamoxifen-treated mice that survived to this end point had lost minimal weight, and by PCR evaluation of Lamc1loxP recombination, had minimal gene recombination. There was no evidence of increased mortality in untreated mutant mice (data not shown). Based on this data, we concluded that the primary phenotype of adult laminin-ɣ1 deficient mice is rapid weight loss followed by mortality. Food and water intake were monitored in smaller cohorts of individually housed tamoxifen-treated control and mutant mice prior to and during a 21 day period inclusive of tamoxifen administration (starting n = 5 for each cohort; Supplemental Fig. 2). No difference in food or water consumption was observed between cohorts.

Figure 2.

Conditional deletion of the Lamc1 gene in adult mice rapidly induces weight loss and morbidity/mortality that is due to gastrointestinal dysfunction. (A) Tamoxifen-treated control (black line) and tamoxifen-treated mutant (red line) mice were weighted the day of first tamoxifen injection, and throughout a three week period. Change in weight and survival are shown. Starting n = 10 for each cohort in weight graph, and mutant n = 17 and control = 10 for survival estimate. (B) Representative pictures of the intestines from tamoxifen treated control (n = 4) and mutant (n = 8) mice just after euthanasia. For (C,D), tamoxifen-treated (CT), tamoxifen-treated mutant (MT). (C) Weight of stool collected over a 10-minute observation period and compared between genotypes. Each data point represents the results from a single mouse. (D) Fecal and serum albumin concentrations compared between genotypes. For panels C&D, each point represents the data from an individual animal. (E) Small intestine sections from CT and MT mice were immunostained with antibodies that recognize thrombomodulin (green) and PGP9.5 (red). Nuclei are stained blue with DAPI. Magnification bars are 50 microns in low magnification images, and 10 microns in high magnification images. 20x and 40x lenses with 1.5x magnifier were used to collect these images. Images are representative of the results obtained from immunofluorescent analysis of 3 tamoxifen-treated control and 4 tamoxifen-treated mutant mice.

Lamc1 gene deletion in adult mice impairs gastrointestinal function and induces loss of serum proteins through the gut-vascular-barrier

Gross examination of small intestines just after euthanasia differentiated between tamoxifen-treated control and mutant tissues, the latter were pale and fluid-distended in comparison with controls (Fig. 2B). To estimate gastrointestinal function, we measured the weight of fecal pellets produced by a single mouse over 10 minutes (Fig. 2C). Laminin-deficient mice had less stool output by mass than did controls (control: 0.16 ± 0.016 grams, n = 4; mutant: 0.033 ± 0.036 grams, n = 4, p = 0.013). Stool pellets from both control and mutant mice were well-formed. No evidence of diarrhea or watery stool was noted.

Gut-vascular-barrier permeability defects cause serum proteins such as albumin to leak into the intestinal tract resulting in elevated fecal albumin and decreased serum albumin. To evaluate barrier function in the laminin-ɣ1-deficient mice, we measured stool and serum albumin content from both cohorts (Fig. 2D). The stool from laminin-deficient mice had a three-fold increase in fecal albumin and a small but statistically significant decrease in serum albumin in comparison with tamoxifen-treated control mice, consistent with a permeability defect.

We evaluated the lamina propria vasculature by immunofluorescent analysis of endothelium and adjacent nerve fibers. In healthy small intestine, the lamina propria microvasculature runs parallel to crypt and villous epithelium. Nerve fibers run adjacent to the microvessels through the center of the villi. We immunostained CT and MT small intestine for thrombomodulin (green) and PGP9.5 (red) to identify endothelial cells and nerve fibers, respectively (Fig. 2E). CT microvasculature and nerve fibers followed the expected histologic organization. However, in MT samples, thrombomodulin-positive endothelium and PGP9.5-positive nerve fibers were primarily detected in chaotic bundles at the interface between crypts and villi- without extension through the length of the villus lamina propria.

Organ-system dysfunction in Lamc1 deleted adult mice is primarily restricted to the gastrointestinal track

Gross examination of other organs failed to identify other overt changes with the notable exceptions of reduced spleen and thymus size in the tamoxifen-treated mutant animals (data not shown). Serum electrolyte (Table 2) analysis was performed to screen for other organ-system specific patterns of illness in the laminin-depleted mice. Neither renal nor hepatic dysfunction were noted—specifically, renal indices of creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) were not elevated, and potassium, sodium, calcium, and phosphorous levels were unchanged between tamoxifen-treated control and mutant mice. Surrogates for hepatic function such as total bilirubin, ALT, AST and alkaline phosphatase also failed to differentiate between genotypes. Total serum protein and globulin differed between the two cohorts, with tamoxifen-treated mutant animals having lower serum concentrations of both. While other causes of mortality cannot be completely excluded, these findings identify a primary defect in gastrointestinal structure and function as the most likely cause of mutant mouse mortality and is consistent with the gastrointestinal tract as the primary site of rapid laminin-ɣ1 protein depletion.

Table 2.

Serum chemistry analysis. * Indicates p < 0.05.

| Control + Tx (±SEM, n) | Mutant + Tx (±SEM, n) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alk Phos: U/L | 89.25 ± 8.240, n = 4 | 91.00 ± 16.68, n = 4 | 0.9281 |

| ALT (SGPT): U/L | 23.75 ± 1.377, n = 4 | 61.75 ± 32.44, n = 4 | 0.2862 |

| AST (SGOT): U/L | 77.25 ± 20.56, n = 4 | 132.0 ± 66.99, n = 4 | 0.4643 |

| Total Bilirubin: mg/dL | 0.1250 ± 0.0250, n = 4 | 0.1000 ± 0.0, n = 4 | 0.3559 |

| Total Protein: g/dL | 4.400 ± 0.04082, n = 4 | 3.225 ± 0.3146, n = 4 | 0.0100* |

| Globulin: g/dL | 2.025 ± 0.04787, n = 4 | 1.525 ± 0.1377, n = 4 | 0.0140* |

| BUN: mg/dL | 29.25 ± 2.136, n = 4 | 30.50 ± 3.122, n = 4 | 0.7523 |

| Creatinine: mg/dL | 0.1750 ± 0.0250, n = 4 | 0.1000 ± 0.0, n = 4 | 0.0240* |

| Cholesterol: mg/dL | 53.50 ± 4.592, n = 4 | 55.50 ± 4.113, n = 4 | 0.7566 |

| Calcium: mg/dL | 8.550 ± 0.08660, n = 4 | 8.333 ± 0.1202, n = 3 | ND |

| Phosphorus: mg/dL | 9.925 ± 0.3224, n = 4 | 8.925 ± 0.5154, n = 4 | 0.1511 |

| TCO2: mmol/L | 19.00 ± 3.028, n = 4 | 21.67 ± 3.844, n = 3 | ND |

| Chloride: mmol/L | 116.5 ± 0.9574, n = 4 | 120.3 ± 2.016, n = 4 | 0.1438 |

| Potassium: mmol/L | 4.200 ± 0.3416, n = 4 | 5.125 ± 0.4366, n = 4 | 0.1462 |

| Sodium: mmol/L | 149.5 ± 1.190, n = 4 | 153.0 ± 2.041, n = 4 | 0.1891 |

Lamc1 deletion in adult mice induces duodenal crypt hyperplasia, villus elongation, and dissociation of epithelium from adjacent mesenchyme

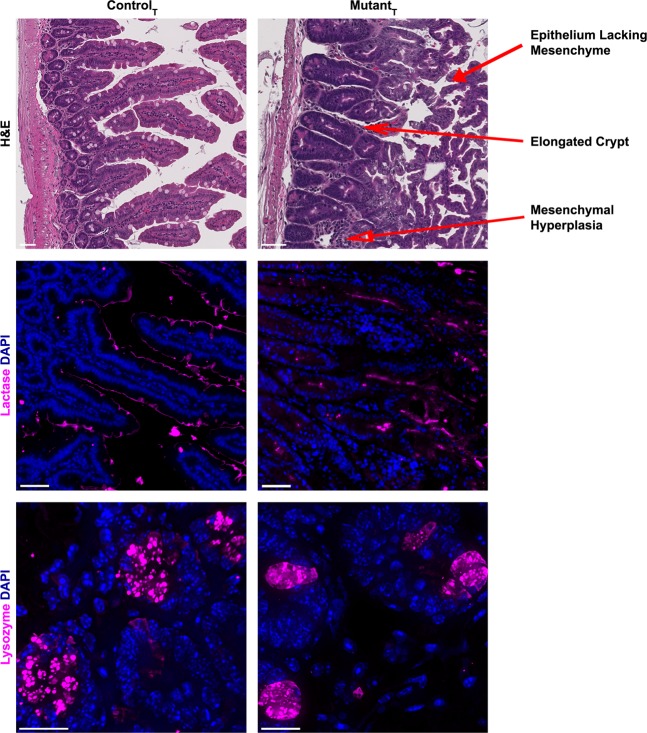

Histologic examination of duodenum from the laminin-deficient mice using hematoxylin and eosin stain revealed epithelial hyperplasia, with development of complex villous architecture and crypt hyperplasia (Fig. 3). In the laminin-deficient mice, the distal-most villi lacked associated mesenchyme, although mesenchyme remained and was hyperplastic adjacent to the point of transition between crypt and villous epithelium. To determine whether both absorptive and secretory epithelia were affected by laminin-ɣ1 deficiency, duodenum sections were stained with antibodies against lactase and lysozyme, and epithelial-specific RNA transcript levels were compared. Mutant intestines had reduced lactase immunoreactivity, and abnormally diffuse lysozyme positivity rather than the concentrated granular staining noted in control samples (Fig. 3). Comparison of duodenal epithelial transcript levels between control and mutant mice did not show a consistent pattern of dysregulation, although lactase transcript was reduced in the mutants, consistent with the observed reduction in immunoreactive lactase protein (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Laminin-ɣ1 deficiency causes intestinal epithelial hyperplasia. Hematoxylin and eosin stained paraffin-embedded tissue sections from tamoxifen-treated control and mutant duodenum. Magnification bars indicate 50 microns. Tamoxifen treated control and mutant paraffin-embedded duodenum sections were stained with antibodies against lactase or lysozyme (magenta). DAPI (blue) was used to label nuclei. Magnification bars indicate 50 microns for panels denoting lactase staining, and 20 microns for those showing lysozyme immunoreactivity. Lysozyme images are a maximum intensity projection image derived from a z-stacked image obtained with a 100x oil lens. Images are representative of the results obtained from immunofluorescent analysis of 3 tamoxifen-treated control and 4 tamoxifen-treated mutant mice.

Table 3.

RT-PCR Analysis of Epithelial and Mesenchymal Transcripts.

| Control + Tx (±SEM, n) | Mutant + Tx (±SEM, n) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lgr5-Epi | 0.2864 ± 0.07627, n = 9 | 0.0508 ± 0.01402, n = 10 | 0.0053** |

| Olfm4-Epi | 15.15 ± 4.903, n = 9 | 3.761 ± 1.336, n = 10 | 0.0311* |

| Tert-Epi | 0.2001 ± 0.03286, n = 8 | 0.07712 ± 0.01662, n = 7 | 0.0071** |

| HopX-Epi | 11.66 ± 2.426, n = 5 | 9.494 ± 2.167, n = 5 | 0.5245 |

| Lactase-Epi | 4.366 ± 1.627, n = 5 | 0.1924 ± 0.1606, n = 4 | 0.0587 |

| Muc2-Epi | 14.78 ± 4.279, n = 6 | 28.44 ± 18.41, n = 6 | 0.4866 |

| Lysozyme-Epi | 94.24 ± 46.41, n = 6 | 67.62 ± 39.26, n = 6 | 0.6709 |

| CgA-Epi | 2.54 ± 0.768, n = 9 | 0.6836 ± 0.0898, n = 10 | 0.0214* |

| NGN3-Epi | 1.852 ± 0.8388, n = 6 | 0.9663 ± 0.7061, n = 5 | 0.4514 |

| Gata4-Epi | 149.5 ± 1.190, n = 4 | 153.0 ± 2.041, n = 4 | 0.1891 |

| Gata6-Epi | 8.550 ± 0.08660, n = 4 | 8.333 ± 0.1202, n = 3 | ND |

| Ihh-Epi | 0.2412 ± 0.05371, n = 7 | 0.08471 ± 0.01031, n = 10 | 0.0039** |

| Patched1-Mes | 5.71 ± 1.578, n = 9 | 1.863 ± 1.002, n = 7 | 0.0755 |

| Abcg5-Epi | 4.400 ± 0.04082, n = 4 | 3.225 ± 0.3146, n = 4 | 0.0100* |

| Abcg8-Epi | 29.25 ± 2.136, n = 4 | 30.50 ± 3.122, n = 4 | 0.7523 |

| Ada-Epi | 35.88 ± 10.76, n = 6 | 36.81 ± 15.29, n = 6 | 0.9614 |

| Akr1b8-Epi | 23.75 ± 1.377, n = 4 | 61.75 ± 32.44, n = 4 | 0.2862 |

| Apoa4-Epi | 4.200 ± 0.3416, n = 4 | 5.125 ± 0.4366, n = 4 | 0.1462 |

| ApoB-Epi | 89.25 ± 8.240, n = 4 | 91.00 ± 16.68, n = 4 | 0.9281 |

| ApoC2-Epi | 50.03 ± 17.52, n = 6 | 83.5 ± 27.38, n = 6 | 0.3275 |

| ApoC3-Epi | 21.29 ± 7.974, n = 6 | 19.8 ± 8.618, n = 5 | 0.9019 |

| Asah2-Epi | 3.839 ± 1.392, n = 5 | 1.091 ± 0.4592, n = 4 | 0.1355 |

| Cck-Epi | 0.1250 ± 0.0250, n = 4 | 0.1000 ± 0.0, n = 4 | 0.3559 |

| CD36-Epi | 0.3076 ± 0.1051, n = 4 | 0.1526 ± 0.04739, n = 4 | 0.2274 |

| Cftr-Epi | 10.03 ± 1.854, n = 4 | 4.231 ± 0.4631, n = 5 | 0.0116* |

| Dnase1-Epi | 4.018 ± 1.422, n = 6 | 0.04963 ± 0.02351, n = 5 | 0.0325* |

| Enpp7-Epi | 0.1001 ± 0.02252, n = 4 | 0.009414 ± 0.007271, n = 3 | ND |

| Fabp2-Epi | 116.5 ± 0.9574, n = 4 | 120.3 ± 2.016, n = 4 | 0.1438 |

| Hsd17b6-Epi | 7.889 ± 2.534, n = 5 | 3.785 ± 2.251, n = 4 | 0.2778 |

| Pdx1-Epi | 2.025 ± 0.04787, n = 4 | 1.525 ± 0.1377, n = 4 | 0.0140* |

| Slc2a1-Epi | 2.236 ± 0.7246, n = 5 | 4.314 ± 0.5867, n = 5 | 0.0564 |

| Slc2a2-Epi | 53.50 ± 4.592, n = 4 | 55.50 ± 4.113, n = 4 | 0.7566 |

| Slc2a5-Epi | 9.925 ± 0.3224, n = 4 | 8.925 ± 0.5154, n = 4 | 0.1511 |

| Slc2a8-Epi | 0.3324 ± 0.08289, n = 4 | 0.5209 ± 0.3911, n = 5 | 0.6875 |

| Slc5a1-Epi | 15.69 ± 4.248, n = 5 | 6.339 ± 2.323, n = 4 | 0.1170 |

| Slc5a11-Epi | 1.191 ± 0.2438, n = 4 | 0.1546 ± 0.1244, n = 4 | 0.0091** |

| Sst-Epi | 0.1750 ± 0.0250, n = 4 | 0.1000 ± 0.0, n = 4 | 0.0240* |

| Ugt2a3-Epi | 6.886 ± 1.61, n = 5 | 3.701 ± 1.32, n = 5 | 0.1646 |

* Indicates p < 0.05 and ** Indicates p < 0.01.

Intestinal epithelial cell proliferation is augmented in laminin-γ1 deficient intestines

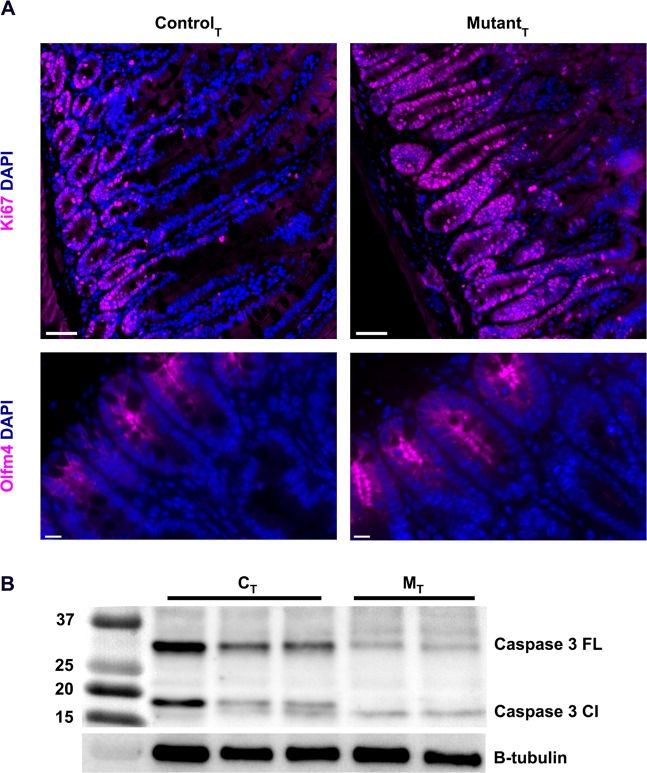

Laminin-ɣ1-deficient intestines had elongated crypts and expanded tubular villi, suggestive of altered epithelial proliferation. To determine whether this was the case, we examined tissue sections using an antibody against nuclear Ki67, which identifies cells in active cell cycle (Fig. 4A). Control samples had a small number of Ki67+ cells, the localization of which was limited to the transit amplification zone and crypt base. However, in the mutant samples, the entire length of the elongated crypts was positive for nuclear Ki67, and ectopic foci of Ki67+ nuclei were also noted in the villi. We then asked whether apoptotic cell death was increased in the laminin-ɣ1 deficient intestines by immunoblot of epithelial cell lysates for caspase 3 (Fig. 4B, Supplemental Fig. 3). In the laminin-ɣ1 deficient samples, neither total nor cleaved caspase 3 were increased above control levels, and thus did not show evidence of increased apoptosis.

Figure 4.

ISPC homeostasis is dysregulated in laminin-ɣ1 deficient intestines. (A) Tamoxifen treated control and mutant paraffin-embedded duodenum sections were stained with antibodies against ki67 or Olfm4 (magenta). DAPI (blue) was used to label nuclei. Magnification bars indicate 50 microns for Ki67 and 10 microns for Olfm4. Images are representative of the results obtained from immunofluorescent analysis of 3 tamoxifen-treated control and 4 tamoxifen-treated mutant mice. (B) Western blot of small intestine from tamoxifen-treated control and mutant mice for caspase 3 expression. Each lane derived from an individual animal. Full western blots for Caspase 3 and B-tubulin are shown in Supplemental Fig. 3.

To determine whether the stem cell pool was impacted by expansion of the Ki67+ transit amplification zone, we compared stem cell transcript levels between control and mutant mice. In epithelium isolated from laminin-γ1 deficient mice, Lgr539–41, Olfm442,43 and Tert44 transcripts were significantly reduced, while HopX transcripts45 was relatively preserved (Table 3). Interestingly, Olfm4 protein expression did not differ between the two cohorts (Fig. 4A). These data are consistent with a significant reduction in the Crypt Base Columnar stem cell pool (Lgr5 and Olfm4). The +4 label retaining quiescent stem cell pool (Tert and HopX) is only somewhat reduced. Neither stem cell population is expanded, leading us to conclude that the Ki67+ cells observed in Fig. 4A are not intestinal stem cells.

Epithelial Indian hedgehog transcript is reduced in laminin-ɣ1 deficient intestines

The hedgehog pathway is an important regulator of epithelial-mesenchymal homeostasis in the gut. Developmental epithelial Ihh deficiency (Villin-Cre; IhhloxP/loxP) leads to early mortality, crypt hyperplasia, transit amplification zone elongation, and mesenchymal expansion at villus bases46. These morphologic changes are similar to what we observed in the laminin-ɣ1 deficient mutants. To further define the degree to which gut homeostasis is dysregulated in the laminin-γ1 deficient mice, we asked whether hedgehog pathway transcripts were altered in the laminin-γ1 depleted small intestines.

Mutant epithelium had a 2.8-fold reduction in Ihh transcript compared with controls (control = 0.2412 ± 0.05371, n = 7; mutant = 0.08471 ± 0.01031, n = 10; p = 0.0039**; Table 3). Ihh not only binds to its receptor Patched1 on mesenchymal cells, it regulates its transcription. Reduced Ihh transcript corresponded with a trend towards reduced Patched1 transcript levels in mesenchyme from the same animals (control = 5.71 ± 1.578, n = 9; mutant = 1.863 ± 1.002, n = 7, p = 0.0755; Table 3).

Discussion

The laminin-γ1 subunit is the most prevalent gamma subunit in laminin heterotrimers isolated from living tissue. Because of the early lethality of laminin-γ1 deficiency in embryologic development, its function in adult physiology is unknown. While laminin-ɣ1 is present in most adult tissues, protein turnover and thus need for active and constitutive synthesis was primarily noted in the gastrointestinal tract. In the small intestine, Lamc1 gene recombination leads to reduced abundance of mesenchymal Lamc1 gene transcript, and a significant reduction in laminin-ɣ1 protein expression. In heart, lung, kidney, liver and spleen, minimal protein reduction was evident three weeks post-induction, suggesting tissue-specific equilibrium of laminin-ɣ1 protein synthesis and degradation.

These results indicate that laminin-γ1 protein is actively turned over and replaced in the adult gastrointestinal tract. In the absence of nascent protein synthesis, the laminin-γ1 content of the small intestine is reduced within three weeks of gene recombination. This has a significant effect on intestinal histology and function. Although both epithelial and mesenchymal compartments are hyperplastic, it is neither coordinated nor functional. Mesenchymal structures, including disorganized neurovascular bundles expand but fail to extend past the villous bases, while numerous villous epithelium stream away from their mesenchymal support and blood supply. These structural changes underlie the gut-vascular barrier dysfunction and increased morbidity induced by Lamc1 gene deletion in the adult mice. The primary source of laminin-γ1 appears to be the mesenchyme, with relatively minimal Lamc1 transcript derived from the epithelium. This is consistent with Li et al.38 whose gene expression analysis comparing epithelial and mesenchymal expression patterns showed similar results.

Reduced epithelial transcription of Ihh is further supportive of our conclusion that epithelial and mesenchymal homeostasis is disrupted in the laminin-γ1 depleted intestines. It is tempting to speculate that this may be more than a marker of disequilibrium, and may in fact be a significant contributor to the mechanism by which laminin-γ1 alters epithelial proliferation. The laminin-ɣ1 deficient small intestines described here, and Ihh46,47 deficient small intestines have several morphologic and biochemical similarities. Epithelial Ihh deficiency (Villin-Cre; IhhLoxp/Loxp) is lethal during early postnatal development because of gastrointestinal dysfunction and malnutrition. These mice also have crypt hyperplasia and reduced transcript levels for extracellular matrix proteins, including the lamc1 transcript46.

Importantly, our results indicate that laminin-γ1 synthesis and degradation in the adult intestinal stem cell niche are actively regulated. Within the limited time frame dictated by the onset of gastrointestinal morbidity following tamoxifen induction of Lamc1 gene deletion in these mice, there were minimal changes in the laminin content or function of the other organ systems we examined. This leads us to conclude that the synthesis and turnover of laminin-γ1 is a context-dependent regulator of gastrointestinal homeostasis. While renal and hepatic function did not change with Lamc1 gene deletion in adult animals, it will be informative to determine whether other adult stem cell niches that actively and constitutively produce lineage-defined cells, such as the bone marrow, are similarly dependent on laminin homeostasis.

The correlation between laminin-γ1 homeostasis and human diseases of adulthood is also unknown. It is certainly noteworthy that LAMC1 SNPs and mutations have been identified as predisposing factors in the development of colorectal malignancy21–24. The rapid development of epithelial hyperplasia in our laminin-γ1-deficient mice provides some functional information relevant to these GWAS studies and leads us to ask whether perturbation of laminin-γ1 homeostasis is a specific contributor to the evolution of gastrointestinal malignancy.

Materials and Methods

Inducible and conditional mutant mouse generation

Mouse husbandry and research protocols were carried out in accordance with protocol AUA00003140, which was approved by The Medical College of Wisconsin’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACAUC). C57BL/6 mice homozygous for the LoxP-flanked Lamc1 gene (Lamc1LoxP) which encodes for laminin-γ1 protein16–18,48 (Strain: B6.129P2-Lamc1tm1Strl/J; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were bred with C57BL/6 mice that express the UBC-Cre-ERT249,50 transgene (Strain: B6.Cg-Tg(UBC-cre-ERT2)1Ejb/J; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME). Genotypes were verified by isolation of genomic DNA and PCR for Cre and Lamc1LoxP as previously described16,17,37. All founder animals had been backcrossed at least nine generations onto the C57Bl/6J background. Mice with the genotype UBC-Cre-ERT2+/−; Lamc1LoxP/LoxP are hereafter referred to as mutant, and Lamc1LoxP/LoxP are referred to as control. In specified experiments, mutant and control mice also expressed the reporter ACTB-tdTomato,-EGFP transgene37 (Strain: B6.129(Cg)-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm4(ACTB-tdTomato,-EGFP)Luo/J; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor).

Tamoxifen-induction of Lamc1fl recombination

Tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was solubilized in corn oil via overnight incubation at 37 °C with agitation. 1 mg was administered via intraperitoneal injection once-daily for four days (4 mg total per mouse). Lamc1LoxP recombination was verified by PCR for the post-recombination gene product (Lamc1r) using the following primer sets (1: GCCTTCTATCGCCTTCTTGAC; 2: AAAGAAGCAGAGTGTGGGGG, and 3: TGGCCTTTTCAACCCTGGAA).

Tissue lysate preparation for Laminin ELISA

Tissues were homogenized using a IKA ULTRA-TURRAX T8 homogenizer in an extraction buffer containing 100 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM Sodium Orthovanadate (Sigma, St Louis MO) or Halt Phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher, Walthm, MA), and protease inhibitors (EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail, Sigma, St Louis MO). Samples were agitated at 4 °C for 2 hours and then centrifuged for 20 minutes at 13,000 rpm. The total protein content of the resultant supernatant was quantified via BCA protein assay (#23227, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

ELISA

The laminin concentration of tissue lysates was quantified relative to total protein using a total Laminin sandwich ELISA kit (#ab119572; Abcam, Cambridge, MA).

Epithelium and mesenchyme tissue fractionation

Intestinal epithelium and mesenchyme were separated by incubation of tissue fragments in ice cold BSS buffer (1 mM KCl, 96 mM NaCl, 27 mM Sodium Citrate, 8 mM KH2PO4, 5.6 mM Na2HPO3, 15 mM EDTA) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors at 4 °C with vigorous shaking for 30 minutes. Sheets of mesenchyme are then removed with forceps.

Western blot

Equivalent amounts of protein from each sample type were heated for 10 minutes to 90 °C in reducing buffer and then analyzed by Tris-Glycine SDS-PAGE (BioRad; Hercules, CA) followed by semi-dry protein transfer onto PVDF membrane (BioRad; Hercules, CA). Blots were blocked with Tris Buffered Saline with 0.1% tween (TBST) and 5% non-fat dry milk overnight at 4 °C, followed by another overnight incubation at 4 °C with one of the following primary antibodies diluted into TBST: anti-Caspase-3 (ab13847, Abcam; Cambridge, MA), anti-β-Tubulin (#PA1-41331, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA; 1:1000). Secondary antibody was anti-rabbit IgG HRP (#sc-2357, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), and SuperSignal Western Blotting Substrates (Dura and Femto; Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA) were used for protein detection. Chemiluminescence was detected using a GE ImageQuant LAS 4000, and ImageJ was used to quantify band intensity from the digital images. Full images of cropped western blots is included in Supplemental Fig. 3.

Tissue preparation for histological characterization

Following euthanasia according to IACUC approved animal use protocol, tissues were either immediately flash-frozen in OCT (used for imaging laminin-γ1), or post-fixed in 10% formalin followed by paraffin embedding or sucrose cryoprotection and/or OCT embedding. Frozen sections were prepared using a Leica cryostat, equipped with a CryoJane tape mechanism. Hematoxylin and Eosin staining was performed by the Blood Research Institute histology core according to standard protocols. H&E stained duodenum sections were analyzed by a clinical gastrointestinal pathologist who was blinded to genotype at the time of slide analysis.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Paraffin embedded sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated, followed by heat-mediated antigen retrieval in Epitope Unmasking Solution (BioWorld; Dublin, OH). Non-specific antibody binding was blocked using No Protein Block (VWR, Radnor, PA), FC Block (Innovex, Richmond, CA) and Horse Serum (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) in Tris-Buffered Saline. The same protocol was used for frozen sections beginning with the blocking step. Experiments using isotype-specific or species specific non-immune IgG in lieu of primary antibody were used as negative controls for all immunofluorescence experiments. Representative images are shown in each figure, with the number of biological replicates for each group detailed in the figure legends. Primary antibodies: Anti-laminin-γ1 (MAB1914B [A5 clone]; EMD Millipore, Burlignton, MA), Anti-laminin-α4 (AF3837; R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN); Anti-laminin-α2 (L0663 [4H8-2 clone]; Sigma, St Louis, MO), Anti-Olfm4 (NBP2-24535SS; Novus, Centennial, CO), Anit-Ki-67 (#ab15580; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), Anti-lysozyme (rabbit-derived, provided by Dr. Tomas Ganz, UCLA to MAB), thrombomodulin (AF3894; R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN), PGP9.5 (ab108986, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and lactase (SC-240614, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX). Secondary antibodies: Alexa-488 conjugated anti-Rabbit IgG, rat IgG and anti-Goat IgG, and Alexa-594 conjugated anti-Rabbit IgG, rat IgG and Goat IgG were from (Invitrogen/Life Technologies; Waltham, MA). Alexa -647 conjugated anti-Goat IgG, anti-Rabbit IgG, and anti-Rat IgG were from Jackson Immuno Research, West Grove, PA. Immunofluorescent staining was imaged using an inverted Nikon Ti-2 E high-speed motorized microscope equipped with the following objectives: CFI Plan APO Lambda 20× (MRD00205), CFI Plan APO Lambda 40× (MRD00405), and CFI Plan APO Lambda 100x oil (MRD01905) objectives. Post-acquisition image processing was performed with Nikon Elements for lysozyme images, Nikon Deconvolution packages. All images were formatted using Imaris software. Image processing parameters were applied equivalently to paired mutant and control images.

Fecal albumin quantification

The stool albumin content was determined by solubilizing 20 mg of stool in 300 µl of cold dilution buffer (included in Mouse Albumin ELISA Kit, E99-134, Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX) for 15 minutes on ice, followed by vortex and centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 5 minutes. Supernatant was used and analyzed by ELISA according to manufacturers protocol (Mouse Albumin ELISA Kit, E99-134, Bethyl Laboratories; Montgomery, TX).

Plasma chemistry measurement

Peripheral blood was collected via inferior vena cava draw at the time of euthanasia. Plasma was prepared and then flash frozen. Analysis was performed by IDEXX (West Sacramento, CA).

RT-PCR analysis

RNA was extracted via Trizol and Trizol LS reagents (Life technologies; Grand Island, NY). Following cDNA preparation with SuperScript IV Vilo (Thermofisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). Individual RT-PCR reactions were completed using a Bio-Rad CFX384 Touch Real-Time PCR thermal cycler, and TaqMan assays format. TaqMan primer sets were all from Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham MA: Lama1 (Mm01226102_m1), Lama2 (Mm00550083_m1), Lama3 (Mm01254735_m1), Lama4 (Mm01193660_m1), Lama5 (Mm01222029_m1), Lamb1 (Mm00801853_m1), Lamb2 (Mm00493080_m1), Lamb3 (Mm00493108_m1), Lamc1 (Mm00711820_m1), Lamc2 (Mm00500494_m1), Lamc3 (Mm01324510_m1), Lactase (Mm01276696_m1), Muc2 (Mm01276696_,1), Lysozyme (Mm00657323_m1), ChgA (Mm00514341_m1), Lgr5 (Mm00438890_m1), Olfm4 (Mm01320260_m1), mTert (Mm01352136_s1), HopX (Mm00558630_m1), NGN3 (Mm00437606_s1), Gata4 (Mm00437606_s1), Gata6 (Mm00802632_m1), Ihh (Mm00439613_m1), Ptchd1 (Mm00436026_m1), Abcg5 (Mm00433937_m1), Abcg8 (Mm00433937_m1), Ada (Mm00545720_m1), Akr1b8 (Mm00484314_m1), Apoa4 (Mm00431814_m1), ApoB (Mm00431814_m1), ApoC2 (Mm00433937_m1), ApoC3 (Mm00433937_m1), Asah2 (Mm00479659_m1), Cck (Mm00446170_m1), CD36 (Mm01135198_m1), Cftr (Mm00445197_m1), Dnase1 (Mm00445197_m1), Enpp7 (Mm01252812_m1), Fabp2 (Mm00433188_m1), Hsd17b6 (Mm00457343_m1), Pdx1 (Mm00435565_m1), Slc2a1 (Mm00441473_m1), Slc2a2 (Mm00441473_m1), Slc2a5 (Mm00433937_m1), Slc2a8 (Mm00433937_m1), Slc5a1 (Mm00433937_m1), Slc5a11 (Mm00433937_m1), Sst (Mm01436671_m1), and Ugt2a3 (Mm01436671_m1). Ct values were normalized against GAPDH (cat #4351309), also from Thermofisher Scientific, Walthan, MA. All samples were run as technical duplicates, with the number of biological replicates (n) indicated within the table.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7.0 software (La Jolla, CA) using the two-tailed students t-test. All data is represented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value of less than 0.05 in a cohort with no less than three biological replicates.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Barbara Fleming from the Blood Research Center histology core for preparation histologic staining of paraffin-embedded tissue samples, Tarrant Csida from the Medical College of Wisconsin for assistance with blood collection and processing for serum chemistry measurements, Marko Ivancich for assistance with figure assembly in Adobe Illustrator, and Yaminin Ogoti for assistance with RNA isolation. This work was funded by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health (5K08HL127187) to KSC, start-up funding from the Medical College of Wisconsin to KSC, the National Institute of Diabetes Digestive and Kidney Diseases at the National Institutes of Health (DK111822) to MAB, and the Medical College of Wisconsin Cancer Center to MAB.

Author contributions

B.F., A.D., M.A.B., M.Z., J.M., A.L., K.K. and K.S.C. performed all experiments which were planned by K.S.C., H.W. and M.A.B. J.W. prepared images in Imaris. M.Z. developed the Lamc1-targetted PCR protocol and mouse breeding strategy. K.S.C. wrote the manuscript. C.H. performed pathologic review of tissue specimens. Manuscript was reviewed and edited by all authors.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: British Fields and Ann DeLaForest.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Michele A. Battle and Karen-Sue Carlson.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-55844-x.

References

- 1.Halfter W, et al. New concepts in basement membrane biology. FEBS J. 2015;282:4466–4479. doi: 10.1111/febs.13495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tunggal P, Smyth N, Paulsson M, Ott MC. Laminins: structure and genetic regulation. Microsc Res Tech. 2000;51:214–227. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20001101)51:3<214::AID-JEMT2>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smyth N, et al. The targeted deletion of the LAMC1 gene. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;857:283–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smyth N, et al. Absence of basement membranes after targeting the LAMC1 gene results in embryonic lethality due to failure of endoderm differentiation. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:151–160. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.1.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hohenester E, Yurchenco PD. Laminins in basement membrane assembly. Cell Adh Migr. 2013;7:56–63. doi: 10.4161/cam.21831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schittny JC, Yurchenco PD. Terminal short arm domains of basement membrane laminin are critical for its self-assembly. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:825–832. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.3.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yurchenco PD, Cheng YS. Laminin self-assembly: a three-arm interaction hypothesis for the formation of a network in basement membranes. Contrib Nephrol. 1994;107:47–56. doi: 10.1159/000422960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yurchenco PD, Cheng YS. Self-assembly and calcium-binding sites in laminin. A three-arm interaction model. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:17286–17299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ettner N, Gohring W, Sasaki T, Mann K, Timpl R. The N-terminal globular domain of the laminin alpha1 chain binds to alpha1beta1 and alpha2beta1 integrins and to the heparan sulfate-containing domains of perlecan. FEBS Lett. 1998;430:217–221. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00601-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hussain SA, Carafoli F, Hohenester E. Determinants of laminin polymerization revealed by the structure of the alpha5 chain amino-terminal region. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:276–282. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKee KK, Harrison D, Capizzi S, Yurchenco PD. Role of laminin terminal globular domains in basement membrane assembly. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21437–21447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702963200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colognato H, Winkelmann DA, Yurchenco PD. Laminin polymerization induces a receptor-cytoskeleton network. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:619–631. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.3.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colognato H, MacCarrick M, O’Rear JJ, Yurchenco PD. The laminin alpha2-chain short arm mediates cell adhesion through both the alpha1beta1 and alpha2beta1 integrins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29330–29336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.29330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siler U, et al. Characterization and functional analysis of laminin isoforms in human bone marrow. Blood. 2000;96:4194–4203. doi: 10.1182/blood.V96.13.4194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGowan KA, Marinkovich MP. Laminins and human disease. Microsc Res Tech. 2000;51:262–279. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20001101)51:3<262::AID-JEMT6>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen ZL, Strickland S. Laminin gamma1 is critical for Schwann cell differentiation, axon myelination, and regeneration in the peripheral nerve. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:889–899. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu WM, Feltri ML, Wrabetz L, Strickland S, Chen ZL. Schwann cell-specific ablation of laminin gamma1 causes apoptosis and prevents proliferation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4463–4472. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5032-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlson KB, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells facilitate axon sorting, myelination, and functional recovery in paralyzed mice deficient in Schwann cell-derived laminin. Glia. 2011;59:267–277. doi: 10.1002/glia.21099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yao Y, Chen ZL, Norris EH, Strickland S. Astrocytic laminin regulates pericyte differentiation and maintains blood brain barrier integrity. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3413. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yao Y. Laminin: loss-of-function studies. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74:1095–1115. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2381-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Tassan NA, et al. A new GWAS and meta-analysis with 1000Genomes imputation identifies novel risk variants for colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10442. doi: 10.1038/srep10442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lou J, et al. A functional polymorphism located at transcription factor binding sites, rs6695837 near LAMC1 gene, confers risk of colorectal cancer in Chinese populations. Carcinogenesis. 2017;38:177–183. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgw204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schumacher FR, et al. Genome-wide association study of colorectal cancer identifies six new susceptibility loci. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7138. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters U, et al. Identification of Genetic Susceptibility Loci for Colorectal Tumors in a Genome-Wide Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:799–807 e724. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akasaka E, et al. Anti-laminin gamma1 pemphigoid associated with ulcerative colitis and psoriasis vulgaris showing autoantibodies to laminin gamma1, type XVII collagen and laminin-332. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:198–199. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2014.2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imanishi A, et al. Pemphigoid with antibodies to laminin gamma1, BP180 and BP230, associated with psoriasis vulgaris: successful disease control with cyclosporin. J Dermatol. 2015;42:394–397. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li X, et al. N-linked glycosylation on laminin gamma1 influences recognition of anti-laminin gamma1 pemphigoid autoantibodies. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;77:125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hofmann SC, Kopp G, Gall C, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Bertz H. Basement membrane antibodies in sera of haematopoietic cell recipients are associated with graft-versus-host disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:587–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmehl K, Florian S, Jacobasch G, Salomon A, Korber J. Deficiency of epithelial basement membrane laminin in ulcerative colitis affected human colonic mucosa. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2000;15:39–48. doi: 10.1007/s003840050006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spenle C, et al. Dysregulation of laminins in intestinal inflammation. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2012;60:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Consortium UIG, et al. Genome-wide association study of ulcerative colitis identifies three new susceptibility loci, including the HNF4A region. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1330–1334. doi: 10.1038/ng.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prager M, Buettner J, Buening C. Genes involved in the regulation of intestinal permeability and their role in ulcerative colitis. J Dig Dis. 2015;16:713–722. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Connelly TM, et al. Genetic determinants associated with early age of diagnosis of IBD. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:321–327. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouatrouss Y, Herring-Gillam FE, Gosselin J, Poisson J, Beaulieu JF. Altered expression of laminins in Crohn’s disease small intestinal mucosa. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:45–50. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64704-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Virtanen I, et al. Differential expression of laminins and their integrin receptors in developing and adult human lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;15:184–196. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.2.8703474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teller IC, et al. Laminins in the developing and adult human small intestine: relation with the functional absorptive unit. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:1980–1990. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, Li L, Luo L. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis. 2007;45:593–605. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li X, et al. Deconvoluting the intestine: molecular evidence for a major role of the mesenchyme in the modulation of signaling cross talk. Physiol Genomics. 2007;29:290–301. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00269.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barker N, et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beumer J, Clevers H. Regulation and plasticity of intestinal stem cells during homeostasis and regeneration. Development. 2016;143:3639–3649. doi: 10.1242/dev.133132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barker N, van Oudenaarden A, Clevers H. Identifying the stem cell of the intestinal crypt: strategies and pitfalls. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:452–460. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schuijers J, van der Flier LG, van Es J, Clevers H. Robust cre-mediated recombination in small intestinal stem cells utilizing the olfm4 locus. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;3:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Flier LG, Haegebarth A, Stange DE, van de Wetering M, Clevers H. OLFM4 is a robust marker for stem cells in human intestine and marks a subset of colorectal cancer cells. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:15–17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montgomery RK, et al. Mouse telomerase reverse transcriptase (mTert) expression marks slowly cycling intestinal stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:179–184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013004108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takeda N, et al. Interconversion between intestinal stem cell populations in distinct niches. Science. 2011;334:1420–1424. doi: 10.1126/science.1213214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kosinski C, et al. Indian hedgehog regulates intestinal stem cell fate through epithelial-mesenchymal interactions during development. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:893–903. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Dop WA, et al. Loss of Indian Hedgehog activates multiple aspects of a wound healing response in the mouse intestine. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(1665–1676):1676 e1661–1610. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Occhi S, et al. Both laminin and Schwann cell dystroglycan are necessary for proper clustering of sodium channels at nodes of Ranvier. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9418–9427. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2068-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruzankina Yaroslava, Pinzon-Guzman Carolina, Asare Amma, Ong Tony, Pontano Laura, Cotsarelis George, Zediak Valerie P., Velez Marielena, Bhandoola Avinash, Brown Eric J. Deletion of the Developmentally Essential Gene ATR in Adult Mice Leads to Age-Related Phenotypes and Stem Cell Loss. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(1):113–126. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Metzger D, Clifford J, Chiba H, Chambon P. Conditional site-specific recombination in mammalian cells using a ligand-dependent chimeric Cre recombinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6991–6995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.