Abstract

The gas-phase linearization of cyclotides via site-selective ring opening at dehydroalanine residues and its application to cyclotide sequencing is presented. This strategy relies on the ability to incorporate dehydroalanine into macrocyclic peptide ions, which is easily accomplished through an ion/ion reaction. Triply protonated cyclotide cations are transformed into radical cations via ion/ion reaction with the sulfate radical anion. Subsequent activation of the cyclotide radical cations generates dehydroalanine at a single cysteine residue, which is easily identified by the odd electron loss of •SCH2CONH2. The presence of dehydroalanine in cyclotides provides a site-selective ring opening pathway that, in turn, generates linear cyclotide analogs in the gas-phase. Unlike cyclic variants, product ions derived from the linear peptides provide rich sequence information. The sequencing capability of this strategy is demonstrated with four known cyclotides found in Viola inconspicua, where, in each case, greater than 93% sequence coverage was observed. Furthermore, the utility of this method is highlighted by the partial de novo sequencing of an unknown cyclotide with much greater sequence coverage than that obtained with a conventional Glu-C digestion approach. This method is particularly well suited for cyclotide species that are not abundant enough to characterize with traditional methods.

Graphical Abstract

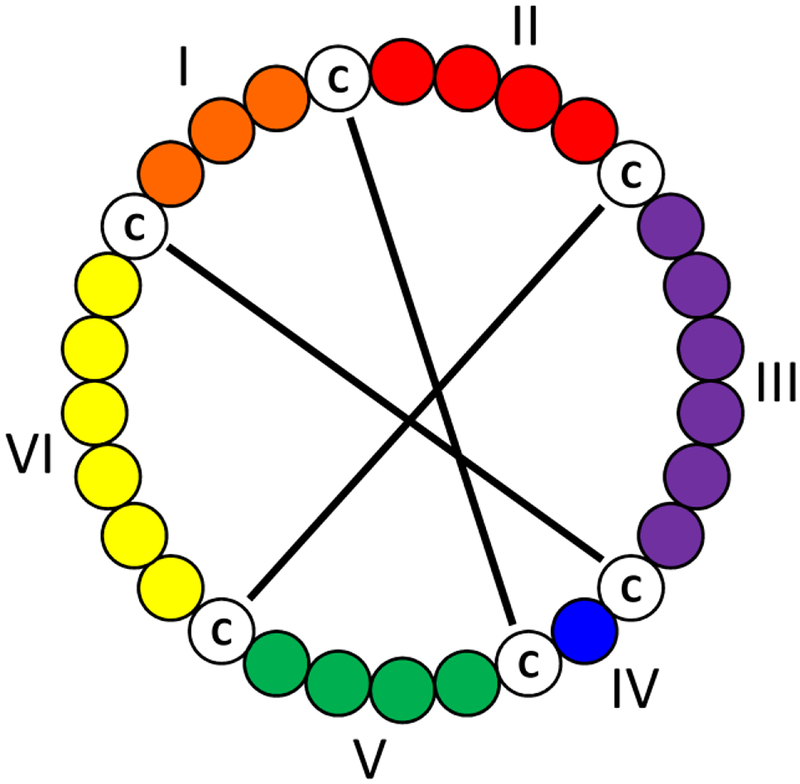

Cyclotides are plant-derived head-to-tail cyclized peptides containing, typically, 28 – 37 amino acids. In addition to the cyclic backbone, these macrocycles contain six cysteine resides, which all participate in disulfide bonding, forming a cyclic cysteine knot. This motif results in extraordinary thermal, chemical, and enzymatic stability.1,2 The regions between the cysteine residues are defined as loops. The general cyclotide motif is provided in Figure 1. As a result, this motif has garnered great interest in biotechnological applications (e.g. drug delivery).3–7 Naturally occurring cyclotides exhibit diverse biological properties including, but not limited to, uterotonic activity to accelerate childbirth,8,9 anti-HIV activity,10–13 cytotoxicity,14,15 trypsin inhibitory activity,16 and insecticidal activity.17–19

Figure 1.

General cyclotide structure showing the head-to-tail cyclic backbone and three disulfide bonds forming the cyclic cysteine knot.

In addition to the diversity of biological activity, there exists great sequence diversity amongst cyclotides. Recent reports estimate a range of 30,000 to 150,000 different sequences in a single plant family.20–22 While the number of unique cyclotides is unknown, these macrocycles have been found in hundreds of plant species from five major plant families, Rubiaceae, Violaceae, Curcurbitaceae, Solanacea, and Fabaceae.23,24 Typically, anywhere from tens to hundreds of cyclotides are found in a single plant.25 The sheer volume of sequenced and predicted cyclotides across plant families led to the development of CyBase (http://www.cybase.org.au), a database of cyclotides and cyclic peptides.26,27 However, to date, CyBase contains only 433 cyclotide sequences. Therefore, it is critical that additional efforts to identify cyclotide sequences must be undertaken to advance the fundamental knowledge of their function.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques have historically been the primary means of cyclotide structural characterization, revealing important three-dimensional characteristics such as disulfide connectivity and structure-activity relationships between the cyclotide and molecular targets.28,29–32 NMR, however, is not well-suited for peptide sequencing. Cyclotides present a number of unique analytical challenges in primary structure elucidation. For example, the innate cyclic motif and high sequence homology between cyclotides present in the same plant species are problematic for sequence characterization. Several analytical approaches have been used for the primary structural analysis of cyclotides that have been able to overcome such challenges.33

Mass spectrometry has played vital roles in cyclotide characterization. In the earliest studies, Edman degradation was used to determine sequence identity while mass spectrometry was used to confirm the peptide mass.10,34,35 Tandem mass spectrometry approaches have emerged as the primary analytical technique in cyclotide sequencing, yet not without associated challenges. Unlike their linear counterparts, MS/MS of cyclic peptides requires the cleavage of two amide bonds to observe any fragment ions. Thus, due to the presence of the cyclic cysteine knot, native cyclotides do not readily fragment.36 As such, tandem mass spectrometry-based techniques employ reduction and alkylation of cysteine residues and proteolytic digestion to induce ring opening prior to MS analysis.

Conventional tandem mass spectrometry techniques for primary structure elucidation of cyclotides heavily rely on certain characteristics unique to this family of peptides. First, putative cyclotides are identified via a mass shift of 348.17 Da between the wild-type and reduced/alkylated samples, corresponding to the addition of 58.02 Da for each of the six cysteine residues present in cyclotides. Additionally, cyclotides contain a highly conserved glutamic acid residue that is often exploited for proteolytic digestion.37–39 This residue is often the only glutamic acid residue present in cyclotides. Digestion with endoproteinase Glu-C cleaves the peptide C-terminal to glutamic acid and aspartic acid. While several cyclotides contain aspartic acid residues, the differences in digestion kinetics of glutamic acid and aspartic acid (approximately 10x slower for aspartic acid) results in predominantly a single acyclic peptide linearized at the single glutamic acid residue. This linear peptide can be fragmented and sequenced. Digestion based methods, however, are not amenable to low abundance cyclotides; sample loss related to reduction, alkylation, and Glu-C digestion of the less abundant species hinders MS/MS analysis, where the precursor is no longer abundant enough to sequence via LC MS/MS analysis.38,40 Additionally, complete sequence coverage is not always achieved with a single digestion. Oftentimes, further digestion with enzymes such as pepsin, trypsin, and chymotrypsin is required, leading to increased analysis times.

An alternative approach to cyclic peptide analysis via solution-based linearization is site-selective ring opening in the gas-phase. In one example, the highly selective cleavage N-terminal to proline has been used to facilitate ring opening in the gas-phase.41,42 More recently, solution-phase conversion of arginine to ornithine was performed to selectively open cyclic peptides C-terminal to ornithine in the gas-phase.43,44 Finally, it has been shown that gold (I) cationization promotes ring opening N-terminal to oxidized lysine residues in the gas-phase. The location of ring opening can be pinpointed to the lysine residue upon MS4, offering a convenient means to cyclic peptide sequencing.45 Of note, competitive ring opening at dehydroalanine was observed in addition to ring opening at lysine.

Herein, we report the site selective linearization of cyclotides at dehydroalanine residues and its application to cyclotide sequencing. In this approach, alkylated cysteine residues are transformed into dehydroalanine residues via gas-phase ion/ion reactions. The selective cleavage of dehydroalanine in linear polypeptides has been described.46,47 Upon collisional activation, abundant c- and z-type fragment ions are formed N-terminal to dehydroalanine. Triply protonated cyclotide ions are transformed into radical cations via gas-phase ion/ion reaction with the sulfate radical anion. Activation of the radical containing cyclotides leads to predominantly the odd-electron side chain loss of carbamidomethyl cysteines and generation of dehydroalanine. Other odd-electron side chain losses from leucine, asparagine, lysine, and glutamic acid to produce dehydroalanine are observed. In the case of the four cyclotides examined, the abundance of these losses is considerably lower than that of the alkylated cysteine residues, and are, therefore, not the primary focus of this study. Subsequent collisional activation produces rich fragmentation corresponding to ring opening at dehydroalanine. This methodology is demonstrated with four known cyclotides of varying abundance, showing, in all cases, cumulative sequence coverage of greater than 93%. Finally, we demonstrate the utility of this method by partial sequencing of an unknown cyclotide found in Viola inconspicua.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials

Ammonium bicarbonate, dithiothreitol (DTT), iodoacetamide, urea, sodium persulfate, and endoproteinase Glu-C enzyme were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). HPLC-grade methanol and acetonitrile and Optima LC/MS-grade water were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ, USA). Acetic acid and formic acid were purchased from Mallinckrodt (Phillipsburg, NJ, USA).

Sample Preparation

Detailed preparation and extraction procedures have been described previously.48 Isolated cyI4 and the complex cyclotide-containing fractions were reconstituted in 1 mL of water. The cyI4 wild type sample was prepared by diluting 10 μL of the stock to 1000 μL with a final composition of 49.5/49.5/1 (by volume) water/methanol/acetic acid. For the early LC fraction, wild type sample was prepared by diluting 100 μL of the stock to 1000 μL with a final composition of 49.5/49.5/1 (by volume) water/methanol/acetic acid.

Reduction and Alkylation

10 μL of cyI4 stock and 100 μL of complex fraction stock were diluted 100x and 10x, respectively, in reduction buffer (100 mM ammonium bicarbonate, 7 M urea). To each vial, 10 μL of DTT stock (500 mM in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate) was added and the samples were incubated at 55 °C for 45 min. 14 μL of freshly prepared iodoacetamide stock (500 mM in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate) was added to the cooled solutions. The samples were incubated for 30 min in the dark. The reaction was quenched with the addition of another 10 μL of DTT stock and allowed to incubate for 15 minutes in the dark. Samples were immediately desalted using TopTip C-18 desalting columns (Glygen, Columbia, MD, USA) per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Ion/Ion Mass Spectrometry

All ion/ion reaction experiments were performed on a TripleTOF 5600 quadrupole/time-of-flight mass spectrometer (SCIEX, Concord, ON, Canada) with modifications for ion/ion reactions and dipolar direct current (DDC) collisional activation analogous to those previously described.49,50 Alternately pulsed nano-electrospray ionization (nESI) allows for the sequential injection of cations and radical anions.51 Triply protonated peptide cations, [M + 3H]3+, were isolated in Q1 and transferred to q2. The sulfate radical anion, [SO4]−•, was isolated in Q1 and transferred to q2 where the two ion populations were mutually stored for 10 ms resulting in the formation of the [M + 3H + SO4]2+• complex. Beam-type CID of the isolated complex from Q1 to q2 or DDC collisional activation in q2 both lead to the consecutive losses of H2SO4 and •SCH2CONH2 (90 Da), in either order, generating [M + H – 90]2+. The [M + H – 90]2+ ion was back transferred to Q1, isolated, and transferred to q2. Ion trap CID was performed in q2 at a q value of 0.2. Product ions were mass analyzed via time-of-flight.

LC-MS/MS Analysis

The reduction, alkylation, and Glu-C digestion of the complex fraction has been described.48 For collisional activation experiments, approximately 1 μg of acidified reduced/alkylated/glu-C digested V. inconspicua sample was injected onto a nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS platform consisting of a NanoAcquity (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) coupled to a TripleTOF5600 MS (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA). Front-end UPLC separation of peptides was achieved on an HSS T3C18 column (100 Å, 1.8 μm, 75 μm × 250 mm, Waters), after passing a Symmetry C18 trap column (100 Å, 5 μm, 180 μm × 20 mm, Waters), with a flow rate of 0.3 μL/min and a 30 minute linear ramp of 5%−50% B (mobile phase A, 1% formic acid in water; mobile phase B, 1% formic acid in acetonitrile). The TripleTOF5600 MS was operated in positive-ion, high-sensitivity mode with the MS survey spectrum using a mass range of 350−1600 Da in 250 ms. Targeted CID MS/MS data was acquired for 3319 Da using reduced/alkylated and Glu-C digested samples and a collision energy (CE) of 40.

For electron transfer dissociation experiments, the material wasanalyzed using a Dionex UltiMate 3000 RSLC nano System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Odense, Denmark) coupled on-line to an ETD-enabled Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Reverse phase peptide separation was accomplished using a trap column (300 mm ID ´ 5 mm) packed with 5 mm 100 Å PepMap C18 medium coupled to a 50-cm long × 75 μm inner diameter analytical column packed with 2 μm 100 Å PepMap C18 silica (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The column temperature was maintained at 50°C. Mobile-phase solvent A consisted of purified water and 0.1% formic acid (FA) and mobile-phase solvent B consisted of 80% acetonitrile and 0.1% FA. Sample was loaded to the trap column in a loading buffer (3% acetonitrile, 0.1% FA) at a flow rate of 5 uL/min for 5 min and eluted from the analytical column at a flow rate of 300 nL/min using a 90-min LC gradient as follows: linear gradient of 6.5 to 27% of solvent B in 55 min, 27–40% of B in next 8 min, 40–100% of B in 7 min at which point the gradient was held at 100% of B for 5 min before reverting back to 2% of B. Mobile phase gradient was held at 2% of B for next 15 min for column equilibration. All data were acquired in the Orbitrap mass analyzer and data were collected using an EThcD fragmentation scheme. For MS scans, the scan range was from m/z 350 to 1600 at a resolution of 120,000, the automatic gain control (AGC) target was set at 4 × 105, maximum injection time 50 ms, dynamic exclusion 30s and intensity threshold 5.0 ×104. MS data were acquired in Data Dependent mode with cycle time of 5s/scan. For ddMS2, the EThCD method was used with parallelizable time activation checked, Orbitrap resolution set at 60,000, the AGC target set at 2 × 105, the ETD reaction time set at 50 ms and the HCD normalized collision energy at 15%. Targeted EThcD MS/MS spectra were also acquired for m/z 922.3968, 922.6982, 922.8982 and 922.1483.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Generation of Dehydroalanine via Ion/Ion Reaction

The odd-electron side chain losses of radical-containing polypeptides and polypeptide fragment ions, zn+•, have been extensively studied.52–56 For several amino acids, this odd-electron loss results in the generation of dehydroalanine.50 In this report, we first generate cyclotide radical cations via ion/ion reaction with the sulfate radical anion, [SO4]−•. Then, dehydroalanine was generated via odd-electron side chain losses upon collisional activation of the cyclotide radical cation, [M + H]2+•. The incorporation of dehydroalanine into cyclotides provides a facile gas-phase linearization pathway, the utility of which is demonstrated with extensive sequence coverage of cyclotides with both known and unknown sequences. This methodology is first demonstrated with the cyclotide cyI4 (Figure 2).

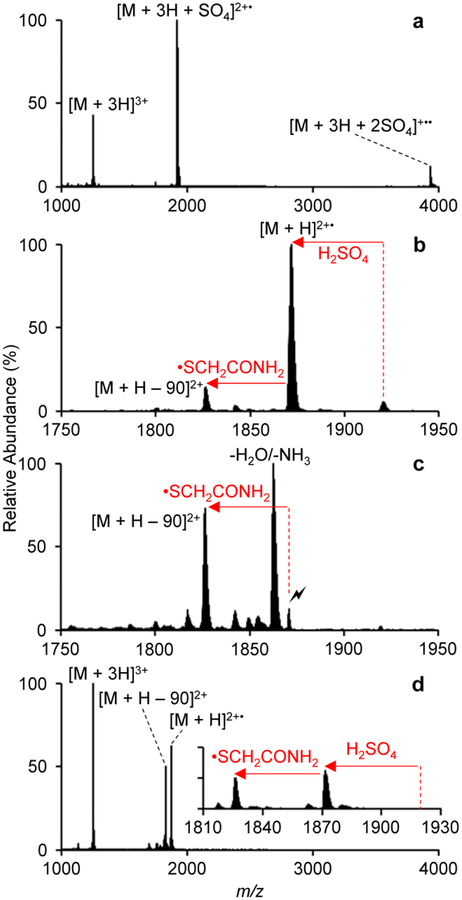

Figure 2.

Ion/ion reaction between triply protonated cyI4 and sulfate radical anion: (a) post ion/ion reaction spectrum, (b) beam-type CID of [M + 3H + SO4]2+•, (c) ion trap CID of [M + H]2+•, and (d) DDC-CID of the ion/ion reaction products of (a).

Ion/ion reaction between triply protonated reduced and alkylated cyI4 and [SO4]−• results in the formation of the [M + 3H + SO4]2+• complex ion, and, to a lesser extent, the [M + 3H + 2SO4]+•• product ion (Figure 2a). Ions were transferred back into Q1, where [M + 3H + SO4]2+• was isolated. Beam-type CID from Q1 to q2 generates a spectrum that shows the major fragmentation pathway to be the loss of sulfuric acid forming the [M + H]2+• radical cation (Figure 2b). Isolation and ion trap CID of [M + H]2+• shows abundant small molecule loss as well as the ejection of •SCH2CONH2 from a carbamidomethyl side chain,57,58 generating dehydroalanine at one of the six cysteine residues (Figure 2c). DDC-CID can be used to generate the product ion of interest, [M + H – 90]2+, ultimately eliminating the need for multiple back transfer and isolation steps (Figure 2d). Interestingly, we also observe that DDC-CID reduces the extent of water and ammonia loss.

It is worth noting that collisional activation also results in the odd-electron side chain losses from leucine, asparagine, lysine, and glutamic acid residues as minor products (< 10% relative abundance). Probing these lower level fragment ions could produce a simpler product ion spectrum (i.e. ring opening at one leucine residue, or three asparagine residues, or three lysine residues, or one glutamic acid residue versus the six cysteine residues). However, for this method to be applicable to sequencing low abundance cyclotides, the loss of •SCH2CONH2 to introduce dehydroalanine was solely explored as this fragmentation pathway was always observed to be the most abundant odd-electron side chain loss.

Opening cyI4 at Dehydroalanine

As cyclotides are head-to-tail cyclic peptides, two backbone cleavages are needed to observe a change in m/z in MSn workflows. An initial c/z cleavage N-terminal to the dehydroalanine generates a linear peptide with an alkyne at the N-terminus and a primary ketimine at the C-terminus. A second backbone cleavage would generate sequence informative fragment ions. The observed loss of 90 Da from [M + H]2+• signifies dehydroalanine formation at a single carbamidomethyl cysteine residue. That is to say, the loss of 90 Da generates six structural isomers of identical mass in which the side chain can be lost from any of the six cysteines. Activation of [M + H – 90]2+ represents a strategy to selectively open the cyclotide at dehydroalanine from any of the isomers.

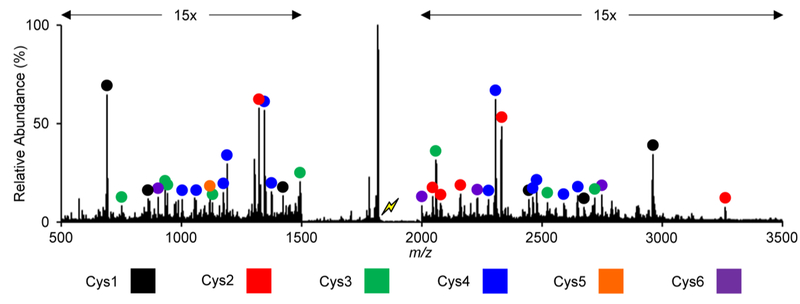

The product ion spectrum from collisional activation of [M + H – 90]2+ derived from ion/ion reaction and subsequent DDC collisional activation is shown to contain high abundance small molecule losses and numerous low abundance fragment ions (Figure 3). The preponderance of the latter corresponds to b- and y- type fragment ions from ring opening at dehydroalanine and are indicated with colored circles (Figure 3). Fragment ions originating from ring opening at dehydroalanine formed at the first, second, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth cysteine are highlighted in black, red, green, blue, orange, and purple, respectively (Figure 3, Supplementary Figure S1, Supplementary Table S1). Please note that a series of product ions originating from an initial b/y cleavage N-terminal to proline is also observed.

Figure 3.

Product ion spectrum from the collisional activation of dehydroalanine containing cyI4, [M + H – 90]2+. The lightning bolt corresponds to the species CID.

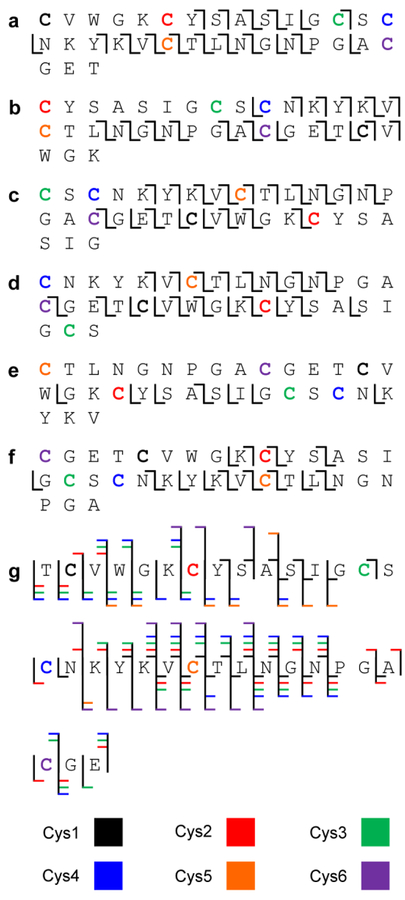

As mentioned above, the [M + H – 90]2+ precursor ion is comprised of six isomers differing only in the position of dehydroalanine. Product ions derived from the linearization of each isomer are observed (Figure 4a–f). Four of the six peptides show greater than 50% sequence coverage – ring opening at the first, second, third, and fourth cysteine results in 53.1%, 53.1%, 56.3%, and 59.4% sequence coverage, respectively. Individually, no single location of ring opening generated sufficient fragmentation to completely sequence cyI4. Cumulatively, however, cleavage at 31 of 33 amide linkages (93.9%) is observed, only lacking fragment ions from the Gly-Cys and Pro-Gly bonds (Figure 4g).

Figure 4.

Individual fragmentation maps of cyI4 opened at (a) Cys1, (b) Cys2, (c) Cys3, (d) Cys4, (e) Cys5, and (f) Cys6. (g) Cumulative fragmentation map from all ring openings.

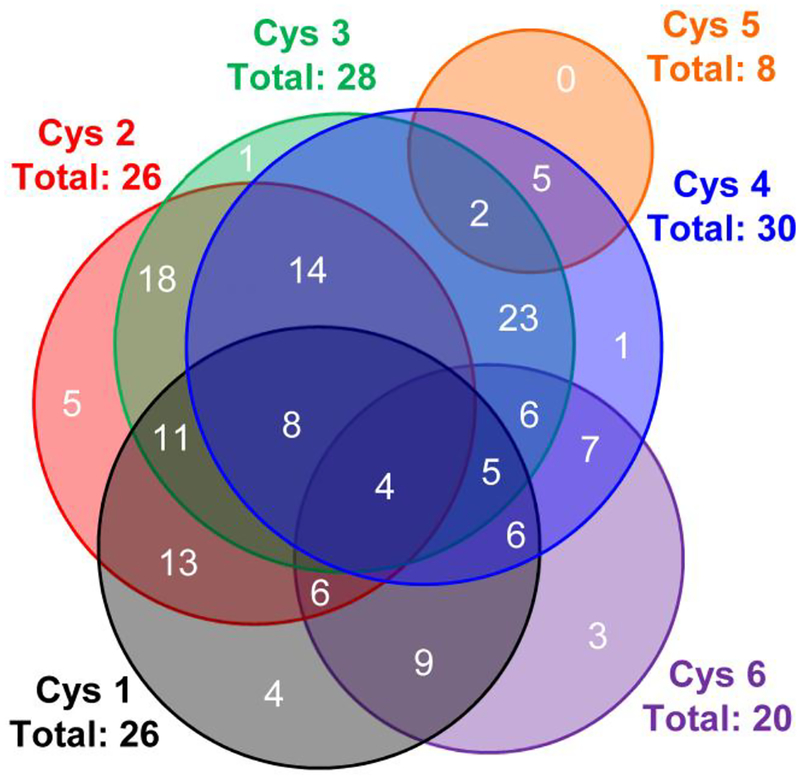

The cumulative sequence coverage is attributed to the complementary sequence information of individual locations of linearization. Examination of the fragmentation maps depicted in Figure 4 reveal that fragmentation is generally localized to the interior of the linearized peptide. As cysteine residues in cyclotides are spaced by as little as one amino acid and as many as ten amino acids, interior fragment ions of the linear peptides can sequence unique portions of the cyclotide (Figure 5). Cysteines in close proximity to one another display several common fragment ions while distant cysteines share few, if any, common fragments. Additionally, Cys1, Cys2, Cys3, Cys4, and Cys5 all show unique fragment ions, where cysteine residues are labeled in sequential order in the Glu-C linearized peptide, TCVWGKCYSASIGCSCNKYKVCTLNGNPGACGE. The combination of overlapped regions and unique regions are a characteristic of selectively opening cyclotides at cysteine residues and aids in the de novo sequencing of unknown cyclotides, which will be demonstrated below.

Figure 5.

Venn diagram showing the unique and overlapping fragment ions from activation of the cyI4 [M + H – 90]2+ ion.

Sequencing Known Cyclotides in a Complex Fraction

Positive nESI of the wild type complex fraction from Viola inconspicua shows triply charged peaks at m/z 1037.1236, 1076.1441, and 1087.4729 corresponding to the known cyclotides viba11, cyO8, and cyI2 (Supplemental Figure S2a). CyO8 is observed to be the base peak, cyI2 is observed at approximately 65% relative abundance, and viba11 is observed at approximately 15% relative abundance. Their identities as cyclotides are confirmed by the mass shift of 348.2 Da upon reduction with DTT and alkylation with iodoacetamide (Supplemental Figure S2b). The three peptides were selected for further interrogation through the gas-phase linearization as described with cyI4.

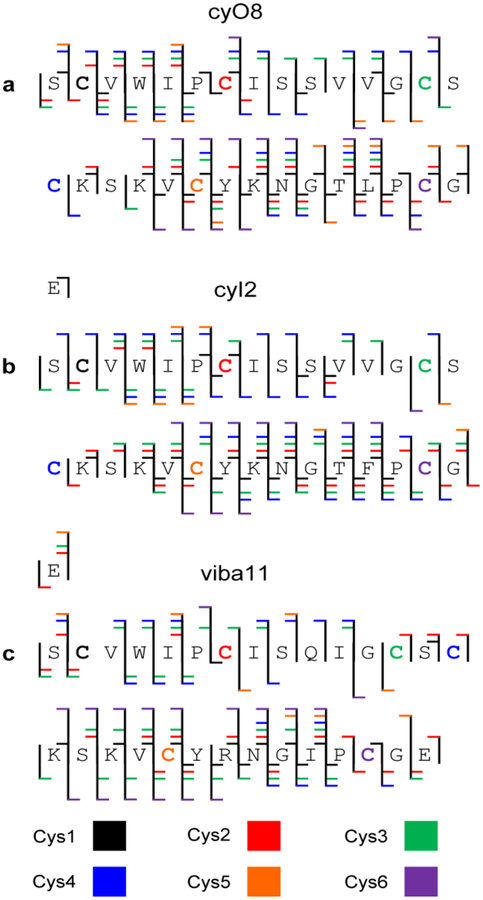

CyO8, cyI2, and viba11 were subjected to the same ion/ion reaction workflow described above. Briefly, ion/ion reaction of the triply protonated species with the sulfate radical anion produces the [M + 3H+SO4]2+• complex. DDC of the ion/ion reaction products results in successive losses of H2SO4 and •SCH2CONH2. Subsequent activation of [M + H – 90]2+ for each of the aforementioned cyclotides generates the product ion spectra with greater than 96% total sequence coverage (Figure 6, Supplemental Figures S3 – S8). Similar to cyI4, there are regions of fragment ion overlap as well as fragment ions unique to specific ring opening sites. In the case of viba11, the fewest number of fragment ions corresponding to ring opening induced by dehydroalanine was observed when compared to cyI4, cyO8, and cyI2. This is likely due, in part, to viba11 being the lowest abundance of the four cyclotides examined and the smallest cyclotide examined with 29 amino acids versus the 31 amino acids of cyO8 and cyI2 and the 33 amino acids of cyI4. Nonetheless, extensive sequence coverage was still observed.

Figure 6.

Cumulative fragmentation maps of (a) cyO8, (b) cyI2, and (c) viba11.

Partial De Novo Sequencing of an Unknown Cyclotide

Inspection of the MS1 spectrum of the complex mixture reveals a putative cyclotide (3319.3445 Da) indicated by the 348.2 Da mass shift (Supplemental Figure S2). To our knowledge, this cyclotide represents an unknown that has not been previously sequenced. Dehydroalanine was introduced at a single cysteine residue and the [M + H – 90]2+ was subjected to collisional activation (Supplemental Figure S9). Analogous to the known sequences above, activation of this species results in the selective ring opening at the dehydroalanine. The resulting product ion spectrum shows numerous fragment ions of ample signal-to-noise that can be used for de novo sequencing. Specifically, the region between m/z 400 and m/z 1700 shows well resolved fragment ions with little chemical noise.

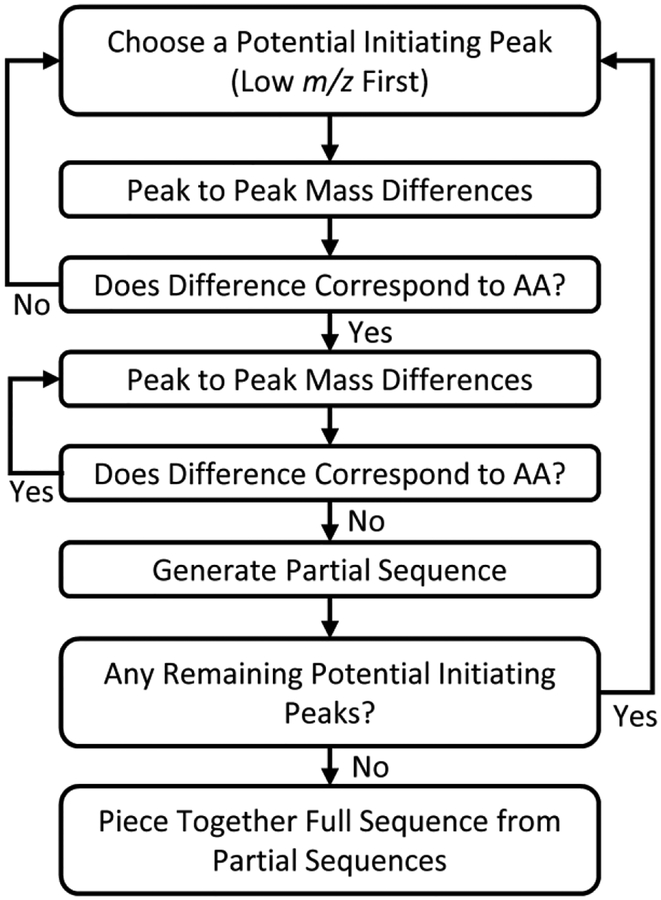

The de novo sequencing was performed according to the general procedure provided in Figure 7. To summarize, first, a product ion of low m/z is selected and then the peak to peak masses for each amino acid are calculated. That is to say, from the chosen product ion new masses are calculated by the addition of the twenty different amino acid residue masses. Next, product ions with an appropriate mass error (less than 100 ppm) and the appropriate isotopic distribution are identified. If there is a peak that corresponds to the addition of an amino acid, this process is repeated until no additional amino acid residues can be identified, generating a partial primary sequence. If no product ions corresponding to an amino acid residue are identified, a new initiating product ion of low m/z is identified, and the process is repeated. This partial sequence generation process is repeated with all potential initiating product ions of low m/z until no initiating ions remain. Here, this workflow was performed via manual data interpretation. Yet, one could imagine this process could be automated if a large number of product ion spectra were to be analyzed.

Figure 7.

General produce for de novo sequencing.

Manual interpretation of the product ion spectrum revealed ten distinct partial sequences, referred to, here, as ion series (Supplemental Figures S10–S20). The aligned partial sequences are displayed in Supplemental Figure S21. As mentioned previously, the sequence information from different locations of linearization is complementary. This characteristic is reinforced in Supplemental Figure S21 where each ion series overlaps with at least one other ion series. In many cases, the overlap serves as an ‘anchor’ point to which the sequence of one ion series can be extended with the sequence of another ion series. For example, the sixth ion series overlaps with the seventh ion series at the glycine and asparagine residues. In the sixth series, six additional residues are identified while in the seventh series, seven additional residues are identified. The combined information results in the partial cyclotide sequence of YKVCT(I/L)NGNPGACGE.

The process of extending the sequence of the unknown cyclotide can be repeated with all ten ion series, yielding a partial sequence of TC(I/L)WGKCYSA-----SKYKVCT(I/L)NGNPGACGE. The dashes indicate unknown amino acid residues of the cyclotide that could not be sequenced based on peak to peak mass differences. However, the identities of the unknown amino acids can be deduced. For the seventh ion series, using the overlap between the fourth ion series and the seventh ion series, the identity of the two amino acids N-terminal to the tyrosine are lysine and serine. Additionally, this workflow selectively opens the cyclotide from a c-/z- cleavage at dehydroalanine, forming a linear peptide with an alkyne as the new N-terminus.45–47 Subtraction of the alkyne moiety (51.9949 Da), lysine (128.0950 Da), serine (87.0320 Da), and an ionizing proton (1.007276 Da) from the initiating peak of the seventh series at m/z 515.1336 accounts for all but 247.0644 Da. The remaining mass suggests two or three amino acids are missing. An analysis of all possible two/three amino acid combinations reveal only two sequences ± 0.1 Da of 247.0644 Da, an alkylated cysteine and serine, in either order. This analysis suggests a sequence of CSC with a serine in Loop 4. This is consistent with the fact that 73% of the cyclotides in cybase contain a Ser in Loop 4. Additionally, the deduction of serine in this position suggests the seventh ion series originates from ring opening at Cys3. The theoretical b5 product ion mass is calculated to be m/z 515.1902 and the first product ion of the seventh series is observed experimentally at m/z 515.1936 (6.5 ppm).

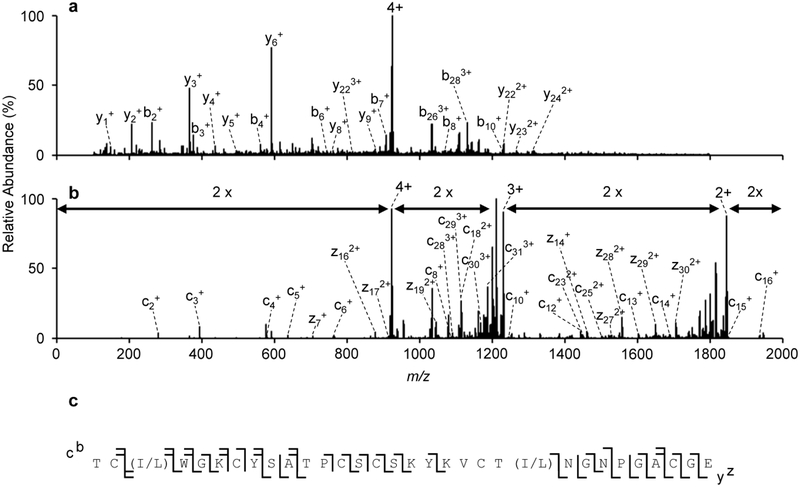

The provisional assignment of serine above now generates a partial cyclotide sequence of TC(I/L)WGKCYSA--CSCSKYKVCT(I/L)NGNPGACGE, where, again, the dashes indicate unknown amino acid residues. The mass of the partial sequence is 3121.2683 Da, accounting for all but 198.0762 Da from the intact unknown. Again, the remaining mass suggests two or three amino acids are missing. An analysis of all possible two/three amino acid combinations reveal only three sequences ± 0.1 Da of 198.0762 Da – PT, TP, and VV. Assignment of leucine/isoleucine based on homology, while not ideal, has been used within the cyclotide community in cases where chymotrypsin digestion cannot be performed due to an adjacent proline residue or in cases where the amount of isolated protein is insufficient for amino acid analysis.59–61 Based on sequence homology to other known cyclotides from the same plant species, the two amino acids would likely be VV.48 However, based on mass, the identity of the unknown residues are likely TP or PT rather than VV (compare 198.1004 Da to 198.1368 Da). The electron transfer dissociation (ETD) product ion spectrum, as shown in Figure 8b, of the Glu-C digested unknown suggests TP rather than PT as c10 and c12 ions are observed. Given that ETD does not result in an observable fragment ion N-terminal to proline, no c10 ion would be observed if the order of these amino acids were PT.

Figure 8.

LC-MS/MS analysis of reduced and alkylated Glu-C digested [unknown + 4H]4+ using (a) targeted CID or (b) targeted EThcD as an activation method. (c). The combined fragmentation maps of (a) and (b).

To summarize, the direct evidence from the de novo sequencing using the ring-opening approach described here results in TC(I/L)WGKCYSA-----SKYKVCT(I/L)NGNPGACGE, accounting for all but five residues. The identities of the remaining residues can be inferred on the basis of mass, as demonstrated above, resulting in a provisional assignment of TC(I/L)WGKCYSA(T/P)(P/T)CSCSKYKVCT(I/L)NGNPGACGE. It is noted here that we cannot distinguish between the isomeric leucine and isoleucine. Additionally, while the mass analysis suggests a threonine and proline at the end of Loop 3, there is insufficient evidence in the product ion spectrum to distinguish between TP or PT. The observed experimental mass of the unknown (3319.3445 Da) is in good agreement with the theoretical mass of the provisional sequence (3319.3687 Da) showing a mass accuracy of 7.3 ppm.

To validate the utility of the described approach to sequencing cyclotides, we compare the results of the gas-phase ring opening at dehydroalanine to the conventional condensed-phase approach. CID and ETD of the Glu-C digested [M + 4H]4+ generates the product ion spectra shown in Figures 8a and 8b, respectively. For CID, twenty-one fragment ions are assigned with high confidence, accounting for cleavages at 17 of 31 amide linkages (54.8%). For ETD, twenty-eight fragment ions are assigned with high confidence, accounting for cleavages at 19 of 31 amide linkages (61.3%). The fragmentation maps are overlaid in Figure 8c. Cumulatively, CID and ETD results in 77.4% sequence coverage. Particularly noteworthy is the stretch of five amino acids, KVCT(I/L) were no fragment ions are observed. Comparison of the two approaches (i.e. ring opening in the gas-phase versus ring opening in the condensed-phase) demonstrates a situation where both approaches can sequence all but five residues. With the conventional digestion approach, however, CID and ETD were needed to generate extensive coverage of the unknown. Additionally, while many cyclotides are abundant enough to be fully sequenced with digestion based methods, many low abundance cyclotides remain uncharacterized. Here, the ability to reduce sample loss with the gas-phase linearization is demonstrated by eliminating the need for proteolytic digestion.

CONCLUSIONS

In this work, we demonstrated the site-selective ring opening of cyclotides at dehydroalanine residues formed via gas-phase ion/ion reaction. Transformation of a single carbamidomethyl cysteine residue to a dehydroalanine residue occurs through the odd-electron loss of •SCH2CONH2. Dehydroalanine can be formed at any of the six alkylated cysteine residues, generating six isomers of identical mass. Collisional activation of [M + H - 90]2+ leads to an initial c/z cleavage N-terminal to dehydroalanine and a second backbone cleavage to produce fragment ions indicative the cyclotide sequence. Linearization from ring opening at all cysteine residues are observed, with sequence coverages of up to 58% observed for individual linearization sites. The fragmentation from each ring opening is highly complementary, which enables extensive sequence coverage to be obtained. For the four known cyclotide sequences examined, cumulative sequence coverages of no less than 93% was observed. This complementarity proved extremely important in the de novo sequencing of an unknown cyclotide from V. inconspicua. Using this novel approach, a partial sequence of TC(I/L)WGKCYSA-----SKYKVCT(I/L)NGNPGACGE is obtained. Interestingly, MS/MS of Glu-C digested cyI7 resulted in much lower sequence coverage, using solely CID or EThcD, demonstrating, further, the utility of the described gas-phase sequencing approach.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under grants GM R37-45372 (S.A.M.) and GM R01-125814 (L.M.H.). The authors acknowledge the use of the Purdue Proteomics Facility of the Bindley Bioscience Center, a core facility affiliated with the NIH-funded Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute. The authors also acknowledge the support of the Purdue Proteomics Facility from the Purdue Center for Cancer Research, NIH grant P30 CA023168.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Craik DJ, Daly NL, Bond T, Waine C: Plant cyclotides: A unique family of cyclic and knotted proteins that defines the cyclic cystine knot structural motif. J. Mol. Biol 294, 1327–1336 (1999) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colgrave ML, Craik DJ: Thermal, Chemical, and Enzymatic Stability of the Cyclotide Kalata B1: The Importance of the Cyclic Cystine Knot. Biochemistry. 43, 5965–5975 (2004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jagadish K, Camarero JA: Cyclotides, a promising molecular scaffold for peptide-based therapeutics. J. Pept. Sci 94, 611–616 (2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henriques ST, Craik DJ: Cyclotides as templates in drug design. Drug Discov. Today 15, 57–64 (2010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poth AG, Chan LY, Craik DJ: Cyclotides as grafting frameworks for protein engineering and drug design applications. J. Pept. Sci 100, 480–491 (2013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burman R, Gunasekera S, Strömstedt AA, Göransson U: Chemistry and Biology of Cyclotides: Circular Plant Peptides Outside the Box. J. Nat. Prod 77, 724–736 (2014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gould A, Camarero JA: Cyclotides: Overview and Biotechnological Applications. ChemBioChem. 18, 1350–1363 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gran L: Oxytocic principles of Oldenlandia affinis. Lloydia. 36, 174–178 (1973) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gran L: On the Effect of a Polypeptide Isolated from “Kalata‐Kalata” (Oldenlandia affinis DC) on the Oestrogen Dominated Uterus. Acta Pharmacol. Toxicol 33, 400–408 (1973) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gustafson KR, Sowder RC, Henderson LE, Parsons IC, Kashman Y, Cardellina JH, McMahon JB, Buckheit RW, Pannell LK, Boyd MR: Circulins A and B. Novel human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-inhibitory macrocyclic peptides from the tropical tree Chassalia parvifolia. J. Am. Chem. Soc 116, 9337–9338 (1994) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gustafson KR, Walton LK, Sowder RC, Johnson DG, Pannell LK, Cardellina JH, Boyd MR: New Circulin Macrocyclic Polypeptides from Chassalia parvifolia. J. Nat. Prod 63, 176–178 (2000) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen B, Colgrave ML, Daly NL, Rosengren KJ, Gustafson KR, Craik DJ: Isolation and Characterization of Novel Cyclotides from Viola hederaceae: Solution Structure and Anti-HIV Activity of vhl-1, A Leaf-Specific Expressed Cyclotide. J. Biol. Chem 280, 22395–22405 (2005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang CKL, Colgrave ML, Gustafson KR, Ireland DC, Goransson U, Craik DJ: Anti-HIV Cyclotides from the Chinese Medicinal Herb Viola yedoensis. J. Nat. Prod 71, 47–52 (2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindholm P, Göransson U, Johansson S, Claeson P, Gullbo J, Larsson R, Bohlin L, Backlund A: Cyclotides: A Novel Type of Cytotoxic Agents 1 P. L. and U. G. contributed equally to this manuscript. Mol. Cancer Ther 1, 365–369 (2002) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Svangård E, Göransson U, Hocaoglu Z, Gullbo J, Larsson R, Claeson P, Bohlin L: Cytotoxic Cyclotides from Viola tricolor. J. Nat. Prod 67, 144–147 (2004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernandez J-F, Gagnon J, Chiche L, Nguyen TM, Andrieu J-P, Heitz A, Trinh Hong T, Pham TTC, Le Nguyen D: Squash Trypsin Inhibitors from Momordica cochinchinensis Exhibit an Atypical Macrocyclic Structure. Biochemistry. 39, 5722–5730 (2000) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jennings C, West J, Waine C, Craik D, Anderson M: Biosynthesis and insecticidal properties of plant cyclotides: The cyclic knotted proteins from Oldenlandia affinis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 98, 10614 (2001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jennings CV, Rosengren KJ, Daly NL, Plan M, Stevens J, Scanlon MJ, Waine C, Norman DG, Anderson MA, Craik DJ: Isolation, Solution Structure, and Insecticidal Activity of Kalata B2, a Circular Protein with a Twist: Do Möbius Strips Exist in Nature? Biochemistry. 44, 851–860 (2005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barbeta BL, Marshall AT, Gillon AD, Craik DJ, Anderson MA: Plant cyclotides disrupt epithelial cells in the midgut of lepidopteran larvae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 105, 1221 (2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gruber CW, Elliott AG, Ireland DC, Delprete PG, Dessein S, Göransson U, Trabi M, Wang CK, Kinghorn AB, Robbrecht E, Craik DJ: Distribution and Evolution of Circular Miniproteins in Flowering Plants. Plant Cell. 20, 2471–2483 (2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Li J, Huang Z, Yang B, Zhang X, Li D, Craik DJ, Baker AJM, Shu W, Liao B: Transcriptomic screening for cyclotides and other cysteine-rich proteins in the metallophyte Viola baoshanensis. J. Plant Physiol 178, 17–26 (2015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hellinger R, Koehbach J, Soltis DE, Carpenter EJ, Wong GK-S, Gruber CW: Peptidomics of Circular Cysteine-Rich Plant Peptides: Analysis of the Diversity of Cyclotides from Viola tricolor by Transcriptome and Proteome Mining. J. Proteome Res 14, 4851–4862 (2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Veer SJ, Weidmann J, Craik DJ: Cyclotides as Tools in Chemical Biology. Acc. Chem. Res 50, 1557–1565 (2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burman R, Yeshak MY, Larsson S, Craik DJ, Rosengren KJ, Göransson U: Distribution of circular proteins in plants: large-scale mapping of cyclotides in the Violaceae. Front. Plant Sci 6, (2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trabi M, Svangård E, Herrmann A, Göransson U, Claeson P, Craik DJ, Bohlin L: Variations in Cyclotide Expression in Viola Species. J. Nat. Prod 67, 806–810 (2004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mulvenna JP, Wang C, Craik DJ: CyBase: a database of cyclic protein sequence and structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, D192–D194 (2006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang CKL, Kaas Q, Chiche L, Craik DJ: CyBase: a database of cyclic protein sequences and structures, with applications in protein discovery and engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D206–D210 (2007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Craik DJ, Daly NL: NMR as a tool for elucidating the structures of circular and knotted proteins. Mol. BioSyst 3, 257–265 (2007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosengren KJ, Daly NL, Plan MR, Waine C, Craik DJ: Twists, Knots, and Rings in Proteins: Structural Definition of the Cyclotide Framework. J. Biol. Chem 278, 8606–8616 (2003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Göransson U, Craik DJ: Disulfide Mapping of the Cyclotide Kalata B1: Chemical Proof of the Cyclic Cysteine Knot Motif. J. Biol. Chem 278, 48188–48196 (2003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y, Gould A, Aboye T, Bi T, Breindel L, Shekhtman A, Camarero JA: In Vivo Activation of the p53 Tumor Suppressor Pathway by an Engineered Cyclotide. J. Am. Chem. Soc 135, 11623–11633 (2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y, Gould A, Aboye T, Bi T, Breindel L, Shekhtman A, Camarero JA: Full Sequence Amino Acid Scanning of θ-Defensin RTD-1 Yields a Potent Anthrax Lethal Factor Protease Inhibitor. J. Med. Chem 60, 1916–1927 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colgrave ML: Chapter Five - Primary Structural Analysis of Cyclotides. In: Craik DJ (ed.). Academic Press, (2015) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Witherup KM, Bogusky MJ, Anderson PS, Ramjit H, Ransom RW, Wood T, Sardana M: Cyclopsychotride A, a Biologically Active, 31-Residue Cyclic Peptide Isolated from Psychotria longipes. J. Nat. Prod 57, 1619–1625 (1994) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saether O, Craik DJ, Campbell ID, Sletten K, Juul J, Norman DG: Elucidation of the Primary and Three-Dimensional Structure of the Uterotonic Polypeptide Kalata B1. Biochemistry. 34, 4147–4158 (1995) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poth AG, Colgrave ML, Philip R, Kerenga B, Daly NL, Anderson MA, Craik DJ: Discovery of cyclotides in the Fabaceae plant family provides new insights into the cyclization, evolution, and distribution of circular proteins. ACS Chem. Biol 6, 345–355 (2011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinto MEF, Najas JZG, Magalhães LG, Bobey AF, Mendonça JN, Lopes NP, Leme FM, Teixeira SP, Trovó M, Andricopulo AD, Koehbach J, Gruber CW, Cilli EM, Bolzani VS: Inhibition of Breast Cancer Cell Migration by Cyclotides Isolated from Pombalia calceolaria. J. Nat. Prod 81, 1203–1208 (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parsley NC, Kirkpatrick CL, Crittenden CM, Rad JG, Hoskin DW, Brodbelt JS, Hicks LM: PepSAVI-MS reveals anticancer and antifungal cycloviolacins in Viola odorata. Phytochemistry. 152, 61–70 (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Narayani M, Sai Varsha MKN, Potunuru UR, Sofi Beaula W, Rayala SK, Dixit M, Chadha A, Srivastava S: Production of bioactive cyclotides in somatic embryos of Viola odorata. Phytochemistry. 156, 135–141 (2018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niyomploy P, Chan LY, Harvey PJ, Poth AG, Colgrave ML, Craik DJ: Discovery and Characterization of Cyclotides from Rinorea Species. J. Nat. Prod 81, 2512–2520 (2018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tomer KB, Crow FW, Gross ML, Kopple KD: Fast-atom bombardment combined with tandem mass spectrometry for the determination of cyclic peptides. Anal. Chem 56, 880–886 (1984) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hitzeroth G, Vater J, Franke P, Gebhardt K, Fiedler H-P: Whole cell matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry and in situ structure analysis of streptocidins, a family of tyrocidine-like cyclic peptides. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 19, 2935–2942 (2005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crittenden CM, Parker WR, Jenner ZB, Bruns KA, Akin LD, McGee WM, Ciccimaro E, Brodbelt JS: Exploitation of the Ornithine Effect Enhances Characterization of Stapled and Cyclic Peptides. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom 27, 856–863 (2016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McGee WM, McLuckey SA: The ornithine effect in peptide cation dissociation. J. Mass Spectrom 48, 856–861 (2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Foreman DJ, Lawler JT, Niedrauer ML, Hostetler MA, McLuckey SA: Gold(I) Cationization Promotes Ring Opening in Lysine-Containing Cyclic Peptides. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom 30, 1914–1922 (2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pilo AL, Peng Z, McLuckey SA: The dehydroalanine effect in the fragmentation of ions derived from polypeptides. J. Mass Spectrom 51, 857–866 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peng Z, Bu J, McLuckey SA: The Generation of Dehydroalanine Residues in Protonated Polypeptides: Ion/Ion Reactions for Introducing Selective Cleavages. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom 28, 1765–1774 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parsley NC, Sadecki PW, Hartmann CJ, Hicks LM: Viola “inconspicua” No More: An Analysis of Antibacterial Cyclotides. J. Nat. Prod 82, 2537–2543 (2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xia Y, Chrisman PA, Erickson DE, Liu J, Liang X, Londry FA, Yang MJ, McLuckey SA: Implementation of Ion/Ion Reactions in a Quadrupole/Time-of-Flight Tandem Mass Spectrometer. Anal. Chem 78, 4146–4154 (2006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Webb IK, Londry FA, McLuckey SA: Implementation of dipolar direct current (DDC) collision-induced dissociation in storage and transmission modes on a quadrupole/time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometer. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 25, 2500–2510 (2011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liang X, Xia Y, McLuckey SA: Alternately Pulsed Nanoelectrospray Ionization/Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization for Ion/Ion Reactions in an Electrodynamic Ion Trap. Anal. Chem 78, 3208–3212 (2006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tureček F, Julian RR: Peptide Radicals and Cation Radicals in the Gas Phase. Chem. Rev 113, 6691–6733 (2013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wee S, O’Hair RAJ, McFadyen WD: Comparing the gas-phase fragmentation reactions of protonated and radical cations of the tripeptides GXR. Int. J. Mass spectrom 234, 101–122 (2004) [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chung TW, Tureček F: Backbone and Side-Chain Specific Dissociations of z Ions from Non-Tryptic Peptides. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom 21, 1279–1295 (2010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eva Fung YM, Chan T-WD: Experimental and theoretical investigations of the loss of amino acid side chains in electron capture dissociation of model peptides. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom 16, 1523–1535 (2005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Han H, Xia Y, McLuckey SA: Ion Trap Collisional Activation of c and z• Ions Formed via Gas-Phase Ion/Ion Electron-Transfer Dissociation. J. Proteome Res 6, 3062–3069 (2007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chalkley RJ, Brinkworth CS, Burlingame AL: Side-Chain Fragmentation of Alkylated Cysteine Residues in Electron Capture Dissociation Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom 17, 1271–1274 (2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sun R-X, Dong M-Q, Song C-Q, Chi H, Yang B, Xiu L-Y, Tao L, Jing Z-Y, Liu C, Wang L-H, Fu Y, He S-M: Improved Peptide Identification for Proteomic Analysis Based on Comprehensive Characterization of Electron Transfer Dissociation Spectra. J. Proteome Res 9, 6354–6367 (2010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ireland D, Colgrave ML, Craik DJ: A Novel Suite of Cyclotides from Viola odorata: Sequence Variation and the Implications for Structure, Function and Stability. Biochem. J 400, 1–12 (2006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Herrmann A, Burman R, Mylne JS, Karlsson G, Gullbo J, Craik DJ, Clark RJ, Göransson U: The Alpine Violet, Viola biflora, is a Rich Source of Cyclotides with Potent Cytotoxicity. Phytochemistry. 69, 939–952 (2008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.He W, Chan LY, Zeng G, Daly NL, Craik DJ, Tan N: Isolation and Characterization of Cytotoxic Cyclotides from Viola philippica. Peptides. 32, 1719–1723 (2011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.