Abstract

Extracellular matrix (ECM) determines the physiological function of all tissues, including musculoskeletal tissues. In tendon, ECM provides overall tissue architecture, which is tailored to match the biomechanical requirements of their physiological function, that is, force transmission from muscle to bone. Tendon ECM also constitutes the microenvironment that allows tendon- resident cells to maintain their phenotype and that transmits biomechanical forces from the macro-level to the micro-level. The structure and function of adult tendons is largely determined by the hierarchical organization of collagen type I fibrils. However, non-collagenous ECM proteins such as small leucine-rich proteoglycans (SLRPs), ADAMTS proteases, and cross-linking enzymes play critical roles in collagen fibrillogenesis and guide the hierarchical bundling of collagen fibrils into tendon fascicles. Other non-collagenous ECM proteins such as the less abundant collagens, fibrillins, or elastin, contribute to tendon formation or determine some of their biomechanical properties. The interfascicular matrix or endotenon and the outer layer of tendons, the epi- and paratenon, includes collagens and non-collagenous ECM proteins, but their function is less well understood. The ECM proteins in the epi- and paratenon may provide the appropriate microenvironment to maintain the identity of distinct tendon cell populations that are thought to play a role during repair processes after injury. The aim of this review is to provide an overview of the role of non-collagenous ECM proteins and less abundant collagens in tendon development and homeostasis.

Keywords: extracellular matrix, tenocyte, pericellular matrix, elastin, proteoglycans

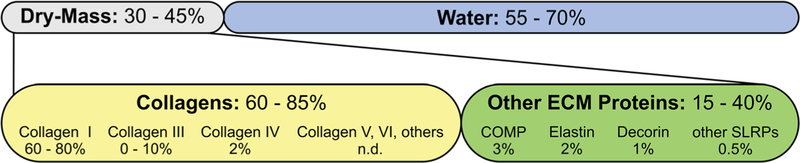

Tendon contains 55–70% water and 30–45% dry mass, which is mostly comprised of extracellular matrix (ECM) (Fig. 1).1 60-85% of the dry mass is attributed to collagens, predominantly collagen type Consequently, the “other” 15–40% of tendon dry mass is attributed to less abundant collagens and non-collagenous ECM proteins.1,2 These ECM proteins are involved in several physiological processes, such as collagen fibril formation and tenocyte homeostasis that contribute to overall tendon function and health. Most studies on the function of these “other” ECM proteins in tendon focused on a subset of small leucine-rich proteoglycans (SLRPS) and their role in collagen fibril formation.5 However, recent knockout studies in mice made it clear that ECM proteins not directly involved in collagen fibrillogenesis may play important roles in tendon physiology. For example, such ECM proteins can provide unique microenvironments to maintain the identity of the different types of tendon-resident cells.6,7 In addition, ECM molecules or their bioactive peptides, generated by proteases, can coordinate cellular responses to microdamage and macrodamage of tendon tissue. In this review, we will illustrate the complexity of tendon tissue by providing an overview of the function of the “other” 15–40% of tendon ECM proteins. Genetic disorders associated with these ECM proteins are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 1.

Tendon composition. Relative quantities of major tendon extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. Numbers are based on Kjaer, Elliott, Connizzo et al., and Thorpe et al. and references therein.1–4 n.d., not determined.

ECM PROTEINS INVOLVED IN COLLAGEN FIBRILLOGENESIS AND FIBRIL BUNDLING

The correct formation of collagen type I fibrils and their subsequent hierarchical bundling into larger functional units is paramount for the proper function of tendons.8 Collagen fibril formation requires the coordinated activity of multiple proteins in the tenocyte pericellular matrix (PCM) and the ECM. The size and arrangement of individual collagen fibrils within the collagen fiber is determined mainly by SLRPs and collagen fibrils are stabilized by enzymatic cross-linking.9

Collagen Propeptidases

The basic units of collagen fibrils are tropocollagen triple helices. The formation of these triple helices requires the proteolytic removal of the N- and the C-terminal propeptide from the procollagen molecule by secreted ECM proteases. The N-terminal collagen propeptide is removed by a disintegrin-like and metalloprotease with thrombospondin type I motives (ADAMTS)2, −3, or −14.10 ADAMTS2 is expressed at high levels in tendon and other tissues rich in collagen type I.11–13 Mutations in ADAMTS2 cause dermatosparaxis which presents with extreme skin fragility and joint laxity in humans and cattle (Supplementary Table S1).14 Adamts2 knockout mice develop a similar skin phenotype, but show less pronounced joint laxity.15 In ADAMTS2-deficient skin, collagen is deposited in abnormal ribbon-like sheets due to the continued presence of the N-terminal propetide.16 Tendon was not analyzed in these studies but the abnormal collagen type I deposition in skin and joint laxity in humans and mice suggest compromised tendon function in the absence of ADAMTS2. Interestingly, in arthrochalasia Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, where the N-terminal collagen propeptide processing site itself is mutated, patients present with joint laxity, but the skin is less affected.17,18 The C-terminal collagen propeptide is removed by BMP1/tolloid-like proteases and the Bmp1 knockout mice show abnormal collagen fibril formation.19,20 In contrast to ADAMTS proteases, where proteolytic activity is negatively regulated by endogenous inhibitors such as tissue-inhibitors of matrix metalloproteases (TIMPs), the activity of BMP1/tolloid-like proteases is positively regulated by procollagen C-proteinase enhancers (PCPE, PCOLCE), fibronectin, or periostin.21–24 Both, the N- and C-terminal procollagen processing proteases have additional substrates, such as decorin, biglycan, and lysyl oxidase (LOX) and thus may be involved in regulating additional steps during collagen type I fibril formation.20,25,26 Recently, a third group of proteases, meprin α and meprin β, have been implicated in procollagen processing.27

Minor Collagens

Besides collagen type I, several other types of fibrillar and non-fibrillar collagens, such as collagen type III, V, VI, XI, XII, and XIV, are present in tendon and are expressed predominantly during tendon development and in the postnatal growth phase.28,29 While collagen type III, V, and XIV expression decreases during later stages of development in chick and/or mouse tendon, collagen type VI and XI continue to be expressed during the postnatal growth phase of tendon and beyond. The knockout mouse models for collagen type V, VI, XI, and XIV collectively suggest a role for these collagens in the assembly and maturation of collagen fibrils. For example, disruption of collagen type V resulted in irregular and disorganized collagen fibrils.30 Knockout of collagen type VI resulted in an increased number of smaller diameter collagen fibrils, while knockout of collagen type XI and XIV resulted in an increase of larger diameter collagen fibrils.31,32 Collagen type XII and XIV are bridging collagen type I fibrils with each other or with neighboring ECM molecules and thus are important in maintaining integrity of collagen type I fibers.33–36 However, collagen type XII and XIV are differentially distributed in tendon and it was proposed that they might play independent roles in the formation of larger tendon compartments, such as tendon fascicles, by organizing or maintaining tissue architecture (collagen type XII) or by modulating collagen fibrillogenesis (collagen type XIV).37–39 Together these studies suggest that these minor collagens play major roles in the formation and organization of collagen fibrils in tendon and that they might be involved in higher-order tendon tissue organization by contributing to collagen fiber bundling or tendon fascicle formation. A comprehensive network-level understanding how all these different collagens work together and how they collaborate with other ECM proteins in collagen fibrillogenesis and in establishing larger tendon compartments remains to be established.

Collagen Cross-Linking

Intramolecular and intermolecular cross-linking of collagen fibrils is an enzyme-mediated process that is required to register collagen molecules during the formation of the tropocollagen triple helix and to stabilize collagen fibrils in tendons. One family of enzymes which mediates the formation of covalent collagen crosslinks are the LOXs comprising LOX itself, and LOX-like 1–4.40 LOX activation requires proteolytic processing by BMP1, which also processes the C-terminal collagen propeptide.22 In addition to BMP1, periostin appears to be required for LOX activity, since periostin-deficient tendon showed reduced LOX-mediated collagen cross-linking.22 LOX requires binding to the tropocollagen triple helix to initiate the cross-linking reaction.41,42 During embryonic chick tendon development, LOX upregulation correlated with the maturation of the biomechanical properties of tendons.43 When LOX activity was inhibited pharmacologically, tendons showed reduced tensile strength, despite maintaining their collagen organization and overall collagen content.43,44 Fibulin-4, an ECM glycol protein, was identified as yet another modulator of LOX-mediated collagen cross-linking.45 Mutations in the human fibulin-4 gene can cause severe vascular abnormalities, cutis laxa, arachnodactyly, and joint laxity (Supplementary Table S1).46 A mouse model for fibulin-4 deficiency showed more abundant collagen fibrils in tendon cross-sections and these alterations were attributed to impaired LOX-mediated collagen cross-linking.45 An independent fibulin-4 knockout mouse showed forelimb contractures and hypermobile joints.47,48 During development, fibulin-4 deficiency disrupted collagen fibril packing and the number of collagen fibril bundles was reduced. These data suggest that LOX may need several accessory ECM proteins to modulate its activity or to serve as a scaffold. Together, the role of LOX underscores that tendon tissue formation not only requires the right amount and composition of ECM, but also requires appropriate covalent posttranslational modifications, such as crosslinks to elaborate fully its biomechanical properties. The role of other cross-linking enzymes in tendon biology, such as transglutaminases, should also be considered.49

SLRPs

The SLRPs are ubiquitously expressed and play key roles in cell signaling, ECM assembly, and ECM turnover.5,50 SLRPS consist of a core protein and covalently attached glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains. SLRPs can interact with many ECM proteins, such as collagen type I, II, III, V, VI, and XI, and fibronectin and they can bind directly to growth factors, such as trans-forming growth factor β (TGFβ) or epidermal growth factor (EGF), modulating their activity.51,52 In addition, SLRPs contribute to the overall stability of collagen fibrils by protecting them from proteolysis by collagenase.53 The two pairs of SLRPs that are relevant for tendon biology, decorin/biglycan, and fibromodulin/lumican, are discussed below.54–58

Decorin

Decorin was named for its ability to “decorate” the collagen fibril network in the ECM.59,60 High-affinity binding to collagen fibrils is mediated by the decorin core protein and is independent of the GAG side chains.61 The decorin-binding domains on collagen fibrils are identical to the biglycan binding sites and both SLRPs can compete for binding to collagen fibrils. Decorin has multiple binding sites for collagen fibrils, suggesting that decorin can non-covalently cross-link several collagen fibrils during growth and maturation and as such contribute to the proper arrangement of collagen fibrils.62 In decorin-deficient tendons, the diameter of collagen type I fibrils was increased and showed a higher variability.63,64 Despite the altered collagen type I fibril diameters, alterations of the bio-mechanical properties of decorin-deficient tendons seemed to depend on the specific tendon type under investigation and the age of the tissue. For example, knockout of decorin had no effect on the biomechanical properties of tendon fascicles from mouse tails, but decorin-deficient patellar tendon showed a higher modulus and increased stress relaxation when uniaxial tension was applied.65 Biglycan may compensate in tail tendon fascicles, but in mouse patellar tendon biglycan was absent, similar to human patellar tendon, and thus may not be able to compensate for the loss of decorin.66

Biglycan

Biglycan is highly expressed during postnatal growth in tendon, bone, and cartilage. Biglycan interacts with collagen type I, VI, and several other ECM proteins.67–69 The absence of biglycan in mice resulted in abnormal collagen fibril formation in tail tendon, where collagen fibril diameters were smaller and the diameter distribution was less regular.70 In biglycan-deficient patellar tendon however, no alteration in collagen fibril diameter was observed, despite alterations in the viscoelastic properties of the tendon.71 Biglycan expression was increased after tendon injury, in contrast to decorin, which was decreased.72,73 Moreover, biglycan contributes to the tendon stem/progenitor cell (TSPC) niche, where biglycan induced tenogenic differentiation of TSPCs while simultaneously inhibiting the chondrogenic and osteogenic differentiation program.6,74

Lumican

Lumican interacts with collagen type I and regulates collagen fibril assembly.75 Addition of purified lumican to cells limits collagen fibril growth in vitro, resulting in thinner fibrils.61,76 Lumican and fibromodulin share the same binding site on collagen fibrils, but the appearance of the collagen type I fibrils in the single knockout and double knockout mice are distinct, suggesting only partial compensation of lumican function by fibromodulin in collagen fibrillogenesis.77–79 Lumican knockout mice show collagen fibrils with a very smooth surface, but an irregular diameter profile with a shift towards smaller diameters.79 Biomechanically, the absence of lumican resulted in tendons with a significant reduction in tensile strength.75

Fibromodulin

Fibromodulin is highly expressed in connective tissues including tendons and ligaments.80 Fibromodulin affects the maturation steps of collagen fibrils through modulation of LOX activity to prevent premature cross-linking.79,81,82 Therefore, fibromodulin-deficient tendons showed a higher proportion of larger diameter collagen fibrils.79 The double knockout of fibromodulin and lumican resulted in joint laxity and gait abnormalities, suggesting a deficiency in tendon strength, specifically a decrease in tendon stiffness.78,79 When fibromodulin was deleted in biglycan-deficient mice, collagen fibrils were smaller and heterotopic tendon ossification was observed.83 The authors speculate that the decrease in tendon stiffness due to smaller collagen fibril diameter may be compensated by ossifying parts of the tendon in an effort to (re)establish the bio-mechanical properties of the tendon to match its functional requirements. More recently, the double knockout of the ADAMTS7 and ADAMTS12 proteases also resulted in heterotopic ossification in the Achilles and patellar tendon concomitant with a reduction in biglycan, fibromodulin, and decorin.84 In these mice, the profile of collagen fibril diameters was skewed towards larger and more irregular fibrils. If ADAMTS7 and ADAMTS12 modulate the turnover of biglycan and fibromodulin in tendon ECM or if they work as proteoglycans independent of their protease activity remains to be established. Finally, biglycan and fibromodulin were identified as part of the TSPC niche. TSPCs isolated from biglycan and fibromodulin double knockout mice proliferated faster and formed more colonies.6 However, gene expression of tendon markers such as scleraxis or collagen type I was reduced, suggesting that these TSPCs proliferated at the expense of their tenocytic differentiation potential or that they maintained their stemness.

Tenascin-C and Periostin

Tenascin-C is expressed in mechanically loaded tissues, such as tendon, but is virtually absent in non-loaded tissues.85,86 However, a tendon phenotype for the tenascin-C knockout mouse was not reported.87 Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in tenascin-C are associated with rotator cuff degeneration but a mechanistic role for tenascin-C in tendon development or homeostasis remains to be established.88,89 Periostin is expressed in collagen-rich tissues, including tendon, and was shown to bind directly to collagen type I.90 In skin from periostin knockout mice, collagen fibrils had a smaller diameter and the skin had decreased stiffness. Collagen cross-linking was reduced in the absence of periostin, suggesting that the major role of periostin is to promote LOX activity in collaboration with BMP1.22 Periostin interacts with tenascin-C and is required for the incorporation of tenascin-C in the ECM.91 The tendon phenotype was not analyzed in periostin knockout mice. In a cell culture study using tenogenic differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor cells, it was shown that periostin is upregulated and that overexpression of periostin in human mesenchymal stem cells resulted in ectopic tendon formation when these modified cells were injected into nude mice.92 This suggests that periostin might play a role in tenocyte differentiation and may be relevant to provide the tenocyte microenvironment together with tenascin-C rather than contributing directly to the bio-mechanical properties of tendon.

The Sliding Proteoglycan Filament Model

On the basis of electron microscopy imaging, computer modeling, and biophysical and biochemical studies, a role for SLRPs and other GAGs and proteoglycans was proposed as interfibrillar collagen bridges to convert compression into tensile strain and thus allow for the recovery of tendon shape after physiological stretching.93 It was further suggested that GAG bridges between collagen fibrils would facilitate sliding of collagen fibrils against each other and thus allow for elastic stretching of tendon tissue beyond strains of >10%, at which individual collagen fibrils are irreversibly damaged. GAG bridges between collagen fibrils were observed using electron microscopy.94 In addition, the X-ray diffraction patterns of tendon tissue under tension are sharper compared with non-stretched tendon, suggesting higher supramolecular order.95 Computational modeling identified GAG content and the area fraction of the collagen fibrils as strong predictors of mechanical behavior, but not collagen fibril diameter itself.96 However, enzymatic or genetic GAG depletion in tendon tissue resulted in surprisingly small changes in mechanical tensile behavior.97–100 Therefore, other biomechanical roles for the GAG-containing proteins in tendon have been proposed, such as the distribution of transverse loads, and contribution to ultimate failure strength or creep/fatigue recovery. In support of biomechanical roles for GAGs and proteoglycans in tendon other than stretch recovery, more recent studies showed, that tendon from decorin knockout mice had decreased tendon viscoelasticity without affecting the elastic properties of tendon.101,102 The exact role for each of the SLRPs and other GAGs and glycoproteins and their cooperative interactions in tendon development and tendon function needs to be further investigated.

THE PCM OF TENDON-RESIDENT CELLS

The PCM represents the cell surface-associated ECM in the immediate vicinity of the cell membrane. The PCM serves as the interface between tissue resident cells and the more distal territorial and interterritorial ECM networks.103 The functional importance of the PCM is well established in cartilage.104 The properties of the PCM can be modulated by the activity of cell-surface-associated proteases or by altering the gene expression of PCM components in response to physiological and pathological stimuli.105,106 Recently, proteomics studies identified more than 100 proteins at the cell surface and the PCM of tenocytes, illuminating the complexity of this ECM compartment.103,107 Some of these PCM components, for which functions have been established, are discussed below.

Tenomodulin

Tenomodulin localizes predominantly to the tenocyte PCM around the more mature, elongated tenocytes, but was less prominent in the PCM of immature, more roundish tenocytes in developing chick tendon.108,109 Tenomodulin is furin-processed at the cell surface and the C-terminal domain, which mediates the physiological functions of tenomodulin, is released into the PCM.110,111 Tendons of tenomodulin knockout mice showed larger and more variable collagen fibril diameters.111 In addition, tenocyte proliferation was decreased in the absence of tenomodulin, resulting in a lower cell density in tendon. Tenomodulin-deficient TSPCs showed reduced self-renewal and cell proliferation capacity, which could be rescued by over-expressing the bioactive C-terminal domain of tenomodulin.112 No binding partners for tenomodulin are known and the molecular mechanisms by which tenomodulin contributes to tendon homeostasis remain to be discovered.

Versican and Aggrecan

Versican and aggrecan are large proteoglycans which are present in many tissues and which are anchored in the PCM via their interactions with hyaluronan and the cell surface receptor CD44.113 The versican and aggrecan PCM facilitates cell shape changes, cell proliferation, and cell differentiation processes.114 The dimension of the versican and aggrecan PCM can be modulated by versicanases or aggrecanases, such as ADAMTS1, −4, or −5.115 In tendon, versican localizes primarily to the tendon midsubstance whereas aggrecan is found closer to the fibrocartilage of the enthesis and in tendon regions that are adjacent to bone, suggesting a role in buffering biomechanical compression.116–120 Versican accumulation was associated with increased ECM volume in patellar tendinosis.121 By knocking out ADAMTS5, the amount of aggrecan, but not versican, was increased in the tenocyte PCM and tendons showed a more heterogeneous distribution of collagen fibril diameters.122

Thrombospondins

The thrombospondin (TSP) protein family of matricellular proteins comprises TSP1–4 and cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP, TSP5).123 As matricellular proteins, TSPs regulate diverse cellular processes such as inflammation, angiogenesis, cell migration, and cell proliferation through participation in cell–ECM and ECM–ECM interactions.124 The TSP2 knockout mouse has lax tail tendons and the tail can be tied into a knot.125 On an ultrastructural level, TSP2-deficient tendons showed a higher percentage of larger collagen fibrils.126 In addition, tendon fascicle formation was abnormal in the absence of TSP2. TSP4 was found in the PCM of tenocytes and to a lesser extend between collagen fibrils. In triceps tendon, TSP3 and TSP4 showed distinct localization and COMP co-localized with TSP4.127 In TSP4-deficient patellar tendons, the distribution of collagen fibril diameters was more irregular with larger diameter collagen fibrils being observed.127 COMP is about tenfold more abundant in weight bearing tendon compared with positional tendons suggesting a role in elaborating the biomechanical properties of these tendons.128,129 A role for load in regulating COMP expression is further supported by its upregulation after birth when load is applied to tendons. For example, COMP is almost absent in horse tendons at birth, but can constitute up to 3% of dry weight in the superficial digital flexor tendon by the age of 2 years.129 Mechanistically, COMP binds to the gap region of fibrillar collagens and thus reinforces collagen fibrils.130 In humans, mutations in COMP cause pseudoachondrodysplasia or multiple epiphyseal dysplasia, which present with dwarfism and lax joints, suggesting a weakening of tendon and ligaments.123 In a mouse model for pseudoachondrodysplasia, joint laxity was observed concomitant with a reduced size of the patellar tendon.131 In a knock-in of a human pseudoachondrodysplasia mutation, collagen fibrils with a larger diameter were more abundant in the presence of mutant COMP in the Achilles tendon in these mice.132 On a tissue level, the Achilles tendon were thinner without a reduction of the collagen fiber occupied area, the ECM between the collagen fibrils, or proteoglycan content. In biomechanical testing, COMP mutant tendon could sustain more stretch and stress.132 However, when undergoing cyclic mechanical testing, COMP mutant tendons became more lax over time when compared to wild type tendon.

Fibrillins and Elastin

Fibrillins form microfibrils in the ECM that serve as a scaffold for several ECM proteins, including tropoelastin, the precursor of elastin.133 Depending on the location, mutations in fibrillin-1 (FBN1) can cause Marfan syndrome or acromelic dysplasias, presenting with either joint laxity or joint contractures, respectively (Supplementary Table S1).134–136 Mutations in fibrillin-2 (FBN2) are associated with congenital contractural arachnodactyly, that is, joint contractures.137,138 Elastin plays a prominent role in sustaining the interaction between tenocytes and ECM in tendon.139 Elastin is found in the PCM of tenocytes and can account for up to 2% of the total dry weight of tendon (Fig. 1).140,141 Some of the stretch and recoil properties of tendon are attributed to elastin.142 Elastic fibers are also found in the interfascicular matrix (IFM), specifically in energy storing tendons and here, elastic fibers become disorganized during aging.143,144. Elastin haploinsufficiency in mice resulted in larger collagen fibrils in the Achilles tendon but not in the supraspinatus tendon.145,146 Surprisingly, elastin-deficient tendons showed no alterations in biomechanical properties, with the exception of a slight increase in linear stiffness.145 FBN1 and FBN2 were found in bovine flexor tendon and in canine flexor digitorum profundus tendon where FBN2 was localized in the PCM of the central tenocytes, while FBN1 localized to the PCM of the peripheral tenocyte layers.143,147 The PCM around the tenocytes is rich in FBN2, which co-localized with versican, where it forms a sturdy ECM that allows for the proteolytic and mechanical isolation of intact tenocyte arrays.139 The FBN2 microfibrils originated from tenocytes and traversed through the PCM finally emerging out from the tendon cell arrays.139 So far, the tendon phenotype of the Fbn1 knockout mice has not been described. Fbn2 knockout mice showed temporary forelimb contractures and decreased collagen fibril cross-linking in the digital flexor tendons.148,149 We recently described a role for ADAMTSL2 in modulating the composition of the PCM around tenocytes in the Achilles tendon.150 Specifically, we found increased FBN1 deposition in the absence of ADAMTSL2. Remarkably, tenocyte organization in linear arrays was distorted and Achilles tendons were shorter and wider. Mutations in ADAMTSL2 cause geleophysic dysplasia, which can also be caused by mutations in FBN1.151,152 Patients with geleophysic dysplasia present with joint contractures and tiptoe walking, and other clinical findings, suggesting dysfunctional tendons.

Perlecan

The heparan sulfate proteoglycan perlecan is yet another PCM component for which a tendon and collagen fibril phenotype was described.153 In a mouse model that lacks the perlecan heparan sulfate chains, smaller collagen fibrils were observed in tail tendon, similar to the phenotype observed in collagen type VI deficient tendon.153,154 The altered collagen fibril structure resulted in increased tensile strength. Perlecan can form a network together with fibrillin microfibrils, elastic fibers, and collagen type VI in the PCM/ECM.155,156 In addition, perlecan can interact with several ECM proteins and growth factors and can anchor fibrillin microfibrils into the basement membrane in skin.157 As such, perlecan may assist in organizing the PCM around tenocytes and connect the tenocyte PCM to the more distal ECM networks.

IFM AND PARATENON

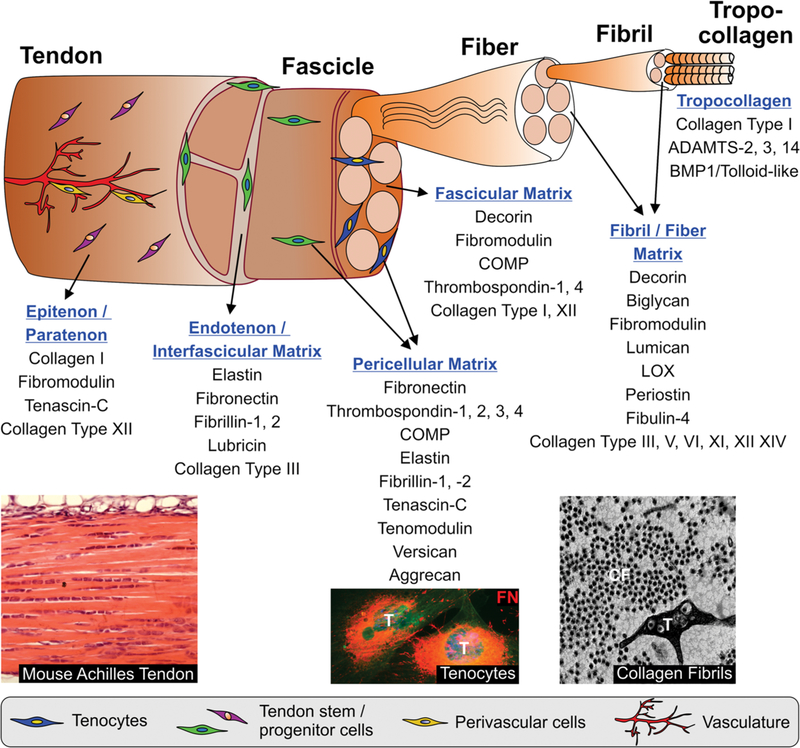

The hierarchical organization of collagen fibrils into fibers and tendon fascicles and the bundling of tendon fascicles into functional tendon gives rise to several distinct connective tissue compartments within the fibers and fascicles, in between tendon fascicles (endotenon or IFM), and surrounding bundles of tendon fascicle (epitenon/paratenon) (Fig. 2).158 In a proteomics study, 130 proteins were identified in the IFM and 92 in the fascicular matrix, several being unique to either one of these ECM compartments.3 Among the SLRPs, immunostaining for lumican, biglycan, and lubricin was more prominent in the IFM in different types of horse tendon, whereas fibromodulin was enriched in the fascicular matrix.159 Decorin was equally distributed between the IFM and the fascicular matrix. In addition, elastic fibers were prominent in the IFM in the superficial digital flexor tendon in horse, the equivalent of the Achilles tendon, suggesting a role for elastic fibers in mediating recoil of energy storing tendons.143 Lubricin is a glycoprotein that was identified in the IFM where it may facilitate the gliding between tendon fascicles due to its anti-adhesive properties.160–162 This role was supported in pullout tests of lubricin knockout mouse-tail tendon fascicles, which showed increased gliding resistance.163 In mouse and dog models of tendon injury, a thickening of the epitenon was observed due to cell proliferation and a similar response was seen in an injury model of horse tendon.164,165 The proliferating cells were characterized by stronger expression of fibronectin, which is an ECM master organizer and one of the earliest ECM proteins deposited during wound healing.166,167 In rat, the epitenon/paratenon contained tenascin-C, collagen type I, and fibromodulin.164 In a patellar injury model in rat, paratenon-derived cells bridged the initial gap space and initiated collagen fibril formation in a circumferential orientation.164 One of the better characterized of the less abundant collagens in the IFM is collagen type III. Collagen type III content is positively correlated with tissues requiring greater compliance and thus is higher in energy storing tendons, compared with positional tendons.3 Collagen type III is more abundant in the IFM compared with the fascicular matrix and is specifically upregulated in the IFM in injured equine tendon as part of the repair response.168 Collagen type III binds to several cell surface receptors, such as the discoidin domain receptors (DDR1, DDR2), PCOLCE, or platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF).169–171 Taken together, the IFM and the tissues surrounding the tendon proper are important compartments that contribute to the biomechanical properties of tendons and support cell-mediated tendon healing processes. Since overall much less is known about the formation and function of the IFM compared with the fascicular matrix and collagen fibers, elucidating the formation and function of the IFM and its adaption to load will be an important area for future research.

Figure 2.

Hierarchical organization of tendon and its extracellular matrix (ECM) compartments. Proteins that play a major role in each of the ECM/pericellular matrix (PCM) compartments in tendon are listed. However, most of the proteins are found in several ECM/PCM compartments and their expression and localization is dynamically regulated during development, growth, and homeostasis and in response to chronic or acute injury. Images on the bottom show (from left to right): Hematoxylin/eosin-stained longitudinal section through mouse Achilles tendon; PCM of murine tenocytes stained for fibronectin (FN, red); electron microscopy image of cross-section through mouse Achilles tendon showing a tenocyte (T) and collagen fibrils (CF).

NON-COLLAGENOUS ECM PROTEINS IN TENDON TISSUE ENGINEERING

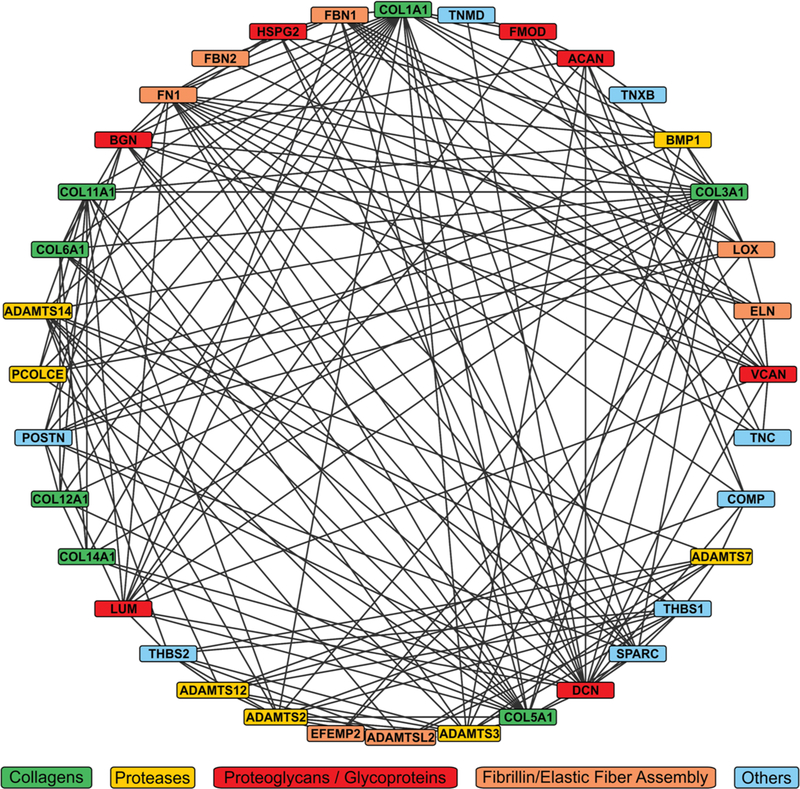

From the diverse functions of the non-collagenous ECM proteins and the minor collagens, it becomes clear that tendon represents a very complex and dynamic tissue, especially during tendon development, growth, und in repair processes upon injury (Fig. 3). To engineer tendon or augment tendon healing after injury, it is likely that some aspects of normal tendon development and growth need to be recapitulated to generate fully functional tendon tissue. Can some of the knowledge on the individual proteins or protein networks in the tendon ECM be harnessed for novel tendon tissue engineering approaches? One such approach utilizes ECM from decellularized tendon tissue as a scaffold for cells.174 The idea is that decellularized tendon ECM has already the ideal biomechanical properties and contains the appropriate biochemical cues to successfully home tenocytes or allow for the differentiation of TSPCs.175 The challenges with this approach are: (i) To identify a source for tendon tissue, taking into account availability, interspecies compatibility, and immunogenicity; (ii) To develop an efficient decellularization protocol that preserves the composition and structure of native tendon ECM as much as possible; (iii) To identify sources for TSPCs to be reseeded on the scaffold under the right culture conditions to allow for differentiation into mature tenocytes. Despite these challenges, decellularized tendon tissue allografts have been evaluated in small and large animal models and showed some promise in augmenting tendon repair after injury.176–179 In addition, overexpression or exogenous addition of individual ECM proteins in combination with a diverse set of growth factors have been shown to enhance tenogenic differentiation of stem cells and augment repair processes in injury models, respectively, and as such could represent an integral part of a comprehensive tendon tissue engineering and repair strategy.74,180–182 An understanding of the dynamic tendon ECM and tenocyte PCM will provide useful guidance to design future therapeutic approaches to augment tendon healing and to invigorate tendon tissue engineering.

Figure 3.

Complexity of the extracellular matrix (ECM)/pericellular matrix (PCM) protein network in tendon tissue. The network of biochemical or proposed functional interactions between ECM/PCM proteins was generated using the String database (https://string-db.org/) which is a curated database that draws information from multiple experimental databases and by text mining.172 The network was visualized using Cytoscape (https://cytoscape.org/).173

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

Tendons are known to withstand substantial mechanical loads, yet various daily activities can cause chronic microdamage or acute injury to tendons.183,184 The healing response, especially of adult tendon, is insufficient to regenerate the tissue in situ as seen by scar formation at the site of injury that can result in chronic functional tendon deficiency.7 Understanding the contribution of tendon-resident cells, their PCM, and the ECM that they construct during tendon development and homeostasis has important implications for tendon regeneration. While much knowledge has been gained from knockout studies of individual genes, providing a comprehensive understanding of the temporal and spatial organization of the PCM and ECM network(s) and of the identity and lineage of the various cell types in tendon is challenging. For example, individual knockout of many tendon ECM proteins resulted in the alteration of collagen fibril diameters either skewing the size distribution towards larger, smaller, or more irregular diameters with very little compensation between related ECM proteins. How do all these proteins work together? What are the (bio-mechanical) parameters that determine the correct size of collagen fibrils? Could the absence of some of these ECM components compromise the biomechanical properties of tendon independent of collagen fibril alterations and could the observed alteration in collagen fibril diameters represent a generic physiological response to (re)adjust the biomechanical properties of tendon? Temporally controlled conditional deletions of these ECM components would address at which stage these proteins are required for tendon homeostasis and such studies already revealed distinct postnatal functions for biglycan and decorin.101 Lineage tracing experiments over the past several years made it abundantly clear that tendon tissue is host to more than one cell type.7,164,185 The questions that arise here are: (i) What components of the tendon ECM do individual cell types synthesize? (ii) Does each of these cell types require its own specific microenvironment, that is, PCM/ECM, to maintain their phenotype; (iii) What is the structure of these microenvironments and how are they created; (iv) How do these microenvironments change during natural tendon aging and in chronic tendinopathies? On a macroscopic level, very little mechanistic information is available on postnatal tendon growth and the formation of larger tendon compartments such as tendon fascicles, or on how tendon fascicles are bundled to form the tendon proper.186 It is conceivable that the ECM plays a major role as a structural glue or in the initial registration of adjacent tendon fibers and fascicles. With these questions in mind, we are looking into a bright future in tendon research specifically trying to understand the complexity and diversity of tendon tissues on a molecular, cellular, and tendon-specific level, reaching far beyond collagen type I fibrils and “the” tenocyte.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

D.H. is supported by the National Institutes of Health (AR070748), the Rare Disease Foundation/BC Children’s Hospital Foundation (Microgrant #2437), and the Leni & Peter W. May Department of Orthopedics at Mt. Sinai.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kjaer M. 2004. Role of extracellular matrix in adaptation of tendon and skeletal muscle to mechanical loading. Physiol Rev 84:649–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elliott DH. 1965. Structure and function of mammalian tendon. Biol Rev 40:392–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thorpe CT, Peffers MJ, Simpson D, et al. 2016. Anatomical heterogeneity of tendon: fascicular and interfascicular tendon compartments have distinct proteomic composition. Sci Rep 6:20455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connizzo BK, Yannascoli SM, Soslowsky LJ. 2013. Structure-function relationships of postnatal tendon development: a parallel to healing. Matrix Biol 32:106–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen S, Birk DE. 2013. The regulatory roles of small leucine-rich proteoglycans in extracellular matrix assembly. FEBS J 280:2120–2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bi Y, Ehirchiou D, Kilts TM, et al. 2007. Identification of tendon stem/progenitor cells and the role of the extracellular matrix in their niche. Nat Med 13:1219–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nichols AEC, Best KT, Loiselle AE. 2019. The cellular basis of fibrotic tendon healing: challenges and opportunities. Transl Res 209:156–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thorpe CT, Birch HL, Clegg PD, et al. 2013. The role of the non-collagenous matrix in tendon function. Int J Exp Pathol 94:248–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kadler KE. 2017. Fell Muir lecture: collagen fibril formation in vitro and in vivo. Int J Exp Pathol 98:4–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bekhouche M, Colige A. 2015. The procollagen N-proteinases ADAMTS2, 3 and 14 in pathophysiology. Matrix Biol 44-46:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuderman L, Prockop DJ. 1982. Procollagen N-proteinase. Eur J Biochem 125:545–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hojima Y, Mörgelin MM, Engel J, et al. 1994. Characterization of type I procollagen N-proteinase from fetal bovine tendon and skin. Purification of the 500-kilodalton form of the enzyme from bovine tendon. J Biol Chem 269: 11381–11390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hojima Y, McKenzie J, Kadler KE, et al. 1992. A new 500-kDa form of type I procollagen N-proteinase from chick embryo tendons. Matrix Suppl 1:97–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colige A, Sieron AL, Li SW, et al. 1999. Human Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type VII C and bovine dermatosparaxis are caused by mutations in the procollagen I N-proteinase gene. Am J Hum Genet 65:308–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li SW, Arita M, Fertala A, et al. 2001. Transgenic mice with inactive alleles for procollagen N-proteinase (ADAMTS-2) develop fragile skin and male sterility. Biochem J 355:271–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith LT, Wertelecki W, Milstone LM, et al. 1992. Human dermatosparaxis: a form of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome that results from failure to remove the amino-terminal propeptide of type I procollagen. Am J Hum Genet 51:235–244. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cole WG, Evans R, Sillence DO. 1987. The clinical features of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type VII due to a deletion of 24 amino acids from the pro alpha 1(I) chain of type I procollagen. J Med Genet 24:698–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giunta C, Superti-Furga A, Spranger S, et al. 1999. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type VII: clinical features and molecular defects. J Bone Joint Surg 81:225–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vadon-Le Goff S, Hulmes DJ, Moali C. 2015. BMP-1/tolloid-like proteinases synchronize matrix assembly with growth factor activation to promote morphogenesis and tissue re-modeling. Matrix Biol 44–46:14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pappano WN, Steiglitz BM, Scott IC, et al. 2003. Use of Bmp1/Tll1 doubly homozygous null mice and proteomics to identify and validate in vivo substrates of bone morphogenetic protein 1/tolloid-like metalloproteinases. Mol Cell Biol 23:4428–4438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessler E, Mould AP, Hulmes DJ. 1990. Procollagen type I C-proteinase enhancer is a naturally occurring connective tissue glycoprotein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 173:81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maruhashi T, Kii I, Saito M, et al. 2010. Interaction between periostin and BMP-1 promotes proteolytic activation of lysyl oxidase. J Biol Chem 285:13294–13303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang G, Zhang Y, Kim B, et al. 2009. Fibronectin binds and enhances the activity of bone morphogenetic protein 1. J Biol Chem 284:25879–25888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy G. 2011. Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases. Genome Biol 12:233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bekhouche M, Leduc C, Dupont L, et al. 2016. Determination of the substrate repertoire of ADAMTS2, 3, and 14 significantly broadens their functions and identifies extracellular matrix organization and TGF-β signaling as primary targets. FASEB J 30:1741–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muir AM, Massoudi D, Nguyen N, et al. 2016. BMP1-like proteinases are essential to the structure and wound healing of skin. Matrix Biol 56:114–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prox J, Arnold P, Becker-Pauly C. 2015. Meprin α and meprin β: procollagen proteinases in health and disease. Matrix Biol 44–46:7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banos CC, Thomas AH, Kuo CK. 2008. Collagen fibrillogenesis in tendon development: current models and regulation of fibril assembly. Birth Defects Res Part C Embryo Today 84:228–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen PK, Pan XS, Li J, et al. 2018. Roadmap of molecular, compositional, and functional markers during embryonic tendon development. Connect Tissue Res 59:495–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun M, Connizzo BK, Adams SM, et al. 2015. Targeted deletion of collagen V in tendons and ligaments results in a classic Ehlers-Danlos syndrome joint phenotype. Am J Pathol 185:1436–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Izu Y, Ansorge HL, Zhang G, et al. 2011. Dysfunctional tendon collagen fibrillogenesis in collagen VI null mice. Matrix Biol 30:53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wenstrup RJ, Smith SM, Florer JB, et al. 2011. Regulation of collagen fibril nucleation and initial fibril assembly involves coordinate interactions with collagens V and XI in developing tendon. J Biol Chem 286:20455–20465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiquet M, Birk DE, Bönnemann CG, et al. 2014. Collagen XII: protecting bone and muscle integrity by organizing collagen fibrils. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 53:51–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giry-Lozinguez C, Aubert-Foucher E, Penin F, et al. 1998. Identification and characterization of a heparin binding site within the NC1 domain of chicken collagen XIV. Matrix Biol 17:145–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Font B, Aubert-Foucher E, Goldschmidt D, et al. 1993. Binding of collagen XIV with the dermatan sulfate side chain of decorin. J Biol Chem 268:25015–25018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Font B, Eichenberger D, Rosenberg LM, et al. 1996. Characterization of the interactions of type XII collagen with two small proteoglycans from fetal bovine tendon, decorin and fibromodulin. Matrix Biol 15:341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Young BB, Zhang G, Koch M, et al. 2002. The roles of types XII and XIV collagen in fibrillogenesis and matrix assembly in the developing cornea. J Cell Biochem 87:208–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang G, Young BB, Birk DE. 2003. Differential expression of type XII collagen in developing chicken metatarsal tendons. J Anat 202:411–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wälchli C, Koch M, Chiquet M, et al. 1994. Tissue-specific expression of the fibril-associated collagens XII and XIV. J Cell Sci 107:669–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mäki JM. 2009. Lysyl oxidases in mammalian development and certain pathological conditions. Histol Histopathol 24:651–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cronlund AL, Smith BD, Kagan HM. 1985. Binding of lysyl oxidase to fibrils of type I collagen. Connect Tissue Res 14: 109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siegel RC. 1974. Biosynthesis of collagen crosslinks: increased activity of purified lysyl oxidase with reconstituted collagen fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 71:4826–4830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marturano JE, Arena JD, Schiller ZA, et al. 2013. Characterization of mechanical and biochemical properties of developing embryonic tendon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 6370–6375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marturano JE, Xylas JF, Sridharan GV, et al. 2014. Lysyl oxidase-mediated collagen crosslinks may be assessed as markers of functional properties of tendon tissue formation. Acta Biomater 10:1370–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sasaki T, Stoop R, Sakai T, et al. 2016. Loss of fibulin-4 results in abnormal collagen fibril assembly in bone, caused by impaired lysyl oxidase processing and collagen cross-linking. Matrix Biol 50:53–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hucthagowder V, Sausgruber N, Kim KH, et al. 2006. Fibulin-4: a novel gene for an autosomal recessive cutis laxa syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 78:1075–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Markova DZ, Pan TC, Zhang RZ, et al. 2016. Forelimb contractures and abnormal tendon collagen fibrillogenesis in fibulin-4 null mice. Cell Tissue Res 364:637–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Papke CL, Tsunezumi J, Ringuette LJ, et al. 2015. Loss of fibulin-4 disrupts collagen synthesis and maturation: implications for pathology resulting from EFEMP2 mutations. Hum Mol Genet 24:5867–5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oliva F, Zocchi L, Codispoti A, et al. 2009. Transglutaminases expression in human supraspinatus tendon ruptures and in mouse tendons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 379:887–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iozzo RV, Schaefer L. 2015. Proteoglycan form and function: a comprehensive nomenclature of proteoglycans. Matrix Biol 42:11–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iozzo RV, Moscatello DK, McQuillan DJ, et al. 1999. Decorin is a biological ligand for the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem 274:4489–4492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ruoslahti E, Yamaguchi Y. 1991. Proteoglycans as modulators of growth factor activities. Cell 64:867–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Geng Y, McQuillan D, Roughley PJ. 2006. SLRP interaction can protect collagen fibrils from cleavage by collagenases. Matrix Biol 25:484–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fisher LW, Termine JD, Young MF. 1989. Deduced protein sequence of bone small proteoglycan I (biglycan) shows homology with proteoglycan II (decorin) and several non-connective tissue proteins in a variety of species. J Biol Chem 264:4571–4576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Santra M, Danielson KG, Iozzo RV. 1994. Structural and functional characterization of the human decorin gene promoter. A homopurine-homopyrimidine S1 nuclease-sensitive region is involved in transcriptional control. J Biol Chem 269:579–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Antonsson P, Heinegård D, Oldberg Å. 1993. Structure and deduced amino acid sequence of the human fibromodulin gene. Biochim Biophys Acta 1174:204–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blochberger TC, Cornuet PK, Hassell JR. 1992. Isolation and partial characterization of lumican and decorin from adult chicken corneas. A keratan sulfate-containing isoform of decorin is developmentally regulated. J Biol Chem 267: 20613–20619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blochberger TC, Vergnes JP, Hempel J, et al. 1992. cDNA to chick lumican (corneal keratan sulfate proteoglycan) reveals homology to the small interstitial proteoglycan gene family and expression in muscle and intestine. J Biol Chem 267:347–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scott JE, Orford CR. 1981. Dermatan sulphate-rich proteoglycan associates with rat tail-tendon collagen at the d band in the gap region. Biochem J 197:213–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keene DR, San Antonio JD, Mayne R, et al. 2000. Decorin binds near the C terminus of type I collagen. J Biol Chem 275:21801–21804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rada JA, Cornuet PK, Hassell JR. 1993. Regulation of corneal collagen fibrillogenesis in vitro by corneal proteoglycan (lumican and decorin) core proteins. Exp Eye Res 56: 635–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Orgel JP, Eid A, Antipova O, et al. 2009. Decorin core protein (decoron) shape complements collagen fibril surface structure and mediates its binding. PLoS ONE 4:e7028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang G, Chen S, Goldoni S, et al. 2009. Genetic evidence for the coordinated regulation of collagen fibrillogenesis in the cornea by decorin and biglycan. J Biol Chem 284:8888–8897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang G, Ezura Y, Chervoneva I, et al. 2006. Decorin regulates assembly of collagen fibrils and acquisition of bio-mechanical properties during tendon development. J Cell Biochem 98:1436–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Robinson PS, Huang TF, Kazam E, et al. 2005. Influence of decorin and biglycan on mechanical properties of multiple tendons in knockout mice. J Biomech Eng 127:181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vogel KG, Ördög A, Pogány G, et al. 1993. Proteoglycans in the compressed region of human tibialis posterior tendon and in ligaments. J Orthop Res 11:68–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schönherr E, Witsch-Prehm P, Harrach B, et al. 1995. Interaction of biglycan with type I collagen. J Biol Chem 270: 2776–2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wiberg C, Heinegård D, Wenglén C, et al. 2002. Biglycan organizes collagen VI into hexagonal-like networks resembling tissue structures. J Biol Chem 277:49120–49126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wiberg C, Hedbom E, Khairullina A, et al. 2001. Biglycan and decorin bind close to the n-terminal region of the collagen VI triple helix. J Biol Chem 276:18947–18952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Corsi A, Xu T, Chen XD, et al. 2002. Phenotypic effects of biglycan deficiency are linked to collagen fibril abnormalities, are synergized by decorin deficiency, and mimic Ehlers-Danlos-like changes in bone and other connective tissues. J Bone Miner Res 17:1180–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dourte LM, Pathmanathan L, Mienaltowski MJ, et al. 2013. Mechanical, compositional, and structural properties of the mouse patellar tendon with changes in biglycan gene expression. J Orthop Res 31:1430–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lui PP, Cheuk YC, Lee YW, et al. 2012. Ectopic chondro-ossification and erroneous extracellular matrix deposition in a tendon window injury model. J Orthop Res 30:37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Berglund M, Reno C, Hart DA, et al. 2006. Patterns of mRNA expression for matrix molecules and growth factors in flexor tendon injury: differences in the regulation between tendon and tendon sheath. J Hand Surg [Am] 31:1279–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang YJ, Qing Q, Zhang YJ, et al. 2019. Enhancement of tenogenic differentiation of rat tendon-derived stem cells by biglycan. J Cell Physiol 234:15898–15910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chakravarti S, Magnuson T, Lass JH, et al. 1998. Lumican regulates collagen fibril assembly: skin fragility and corneal opacity in the absence of lumican. J Cell Biol 141:1277–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vogel KG, Trotter JA. 1987. The effect of proteoglycans on the morphology of collagen fibrils formed in vitro. Coll Relat Res 7:105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Svensson L, Närlid I, Oldberg Å. 2000. Fibromodulin and lumican bind to the same region on collagen type I fibrils. FEBS Lett 470:178–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jepsen KJ, Wu F, Peragallo JH, et al. 2002. A syndrome of joint laxity and impaired tendon integrity in lumican- and fibromodulin-deficient mice. J Biol Chem 277:35532–35540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ezura Y, Chakravarti S, Oldberg Å, et al. 2000. Differential expression of lumican and fibromodulin regulate collagen fibrillogenesis in developing mouse tendons. J Cell Biol 151: 779–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Oldberg A, Antonsson P, Lindblom K, et al. 1989. A collagen- binding 59-kd protein (fibromodulin) is structurally related to the small interstitial proteoglycans PG-S1 and PG-S2 (decorin). EMBO J 8:2601–2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kalamajski S, Bihan D, Bonna A, et al. 2016. Fibromodulin interacts with collagen cross-linking sites and activates lysyl oxidase. J Biol Chem 291:7951–7960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kalamajski S, Liu C, Tillgren V, et al. 2014. Increased C-telopeptide cross-linking of tendon type I collagen in fibromodulin-deficient mice. J Biol Chem 289:18873–18879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ameye L, Aria D, Jepsen K, et al. 2002. Abnormal collagen fibrils in tendons of biglycan/fibromodulin-deficient mice lead to gait impairment, ectopic ossification, and osteo-arthritis. FASEB J 16:673–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mead TJ, McCulloch DR, Ho JC, et al. 2018. The metal-loproteinase-proteoglycans ADAMTS7 and ADAMTS12 provide an innate, tendon-specific protective mechanism against heterotopic ossification. JCI Insight 3:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jarvinen TA, Jozsa L, Kannus P, et al. 2003. Mechanical loading regulates the expression of tenascin-C in the my-otendinous junction and tendon but does not induce de novo synthesis in the skeletal muscle. J Cell Sci 116:857–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Järvinen TA, Jozsa L, Kannus P, et al. 1999. Mechanical loading regulates tenascin-C expression in the osteotendinous junction. J Cell Sci 112:3157–3166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mackie EJ, Tucker RP. 1999. The tenascin-C knockout revisited. J Cell Sci 112:3847–3853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kluger R, Burgstaller J, Vogl C, et al. 2017. Candidate gene approach identifies six SNPs in tenascin-C (TNC) associated with degenerative rotator cuff tears: genetic risk for tendon tears. J Orthop Res 35:894–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kluger R, Huber KR, Seely PG, et al. 2017. Novel tenascin-C haplotype modifies the risk for a failure to heal after rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med 45:2955–2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Norris RA, Damon B, Mironov V, et al. 2007. Periostin regulates collagen fibrillogenesis and the biomechanical properties of connective tissues. J Cell Biochem 101:695–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kii I, Nishiyama T, Li M, et al. 2010. Incorporation of tenascin-C into the extracellular matrix by periostin underlies an extracellular meshwork architecture. J Biol Chem 285: 2028–2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Noack S, Seiffart V, Willbold E, et al. 2014. Periostin secreted by mesenchymal stem cells supports tendon formation in an ectopic mouse model. Stem Cells Dev 23: 1844–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Scott JE. 2003. Elasticity in extracellular matrix ‘shape modules’ of tendon, cartilage, etc. A sliding proteoglycan-filament model. J Physiol 553:335–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Scott JE. 1990. Proteoglycan: collagen interactions and subfibrillar structure in collagen fibrils. J Anat 169:23–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Castellani PP, Morocutti M, Franchi M, et al. 1983. Arrangement of microfibrils in collagen fibrils of tendons in the rat tail: ultrastructural and X-ray diffraction investigation. Cell Tissue Res 234:735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Robinson PS, Lin TW, Jawad AF, et al. 2004. Investigating tendon fascicle structure-function relationships in a transgenic-age mouse model using multiple regression models. Ann Biomed Eng 32:924–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fessel G, Snedeker JG. 2011. Equivalent stiffness after glycosaminoglycan depletion in tendon—an ultrastructural finite element model and corresponding experiments. J Theor Biol 268:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fessel G, Snedeker JG. 2009. Evidence against proteoglycan mediated collagen fibril load transmission and dynamic viscoelasticity in tendon. Matrix Biol 28:503–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Robinson PS, Lin TW, Reynolds PR, et al. 2004. Strain-rate sensitive mechanical properties of tendon fascicles from mice with genetically engineered alterations in collagen and decorin. J Biomech Eng 126:252–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lujan TJ, Underwood CJ, Jacobs NT, et al. 2009. Contribution of glycosaminoglycans to viscoelastic tensile behavior of human ligament. J Appl Physiol 106: 423–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Robinson KA, Sun M, Barnum CE, et al. 2017. Decorin and biglycan are necessary for maintaining collagen fibril structure, fiber realignment, and mechanical properties of mature tendons. Matrix Biol 64:81–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dourte LM, Pathmanathan L, Jawad AF, et al. 2012. Influence of decorin on the mechanical, compositional, and structural properties of the mouse patellar tendon. J Biomech Eng 134:031005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Smith SM, Thomas CE, Birk DE. 2012. Pericellular proteins of the developing mouse tendon: a proteomic analysis. Connect Tissue Res 53:2–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Guilak F, Nims RJ, Dicks A, et al. 2018. Osteoarthritis as a disease of the cartilage pericellular matrix. Matrix Biol 71–72:40–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nandadasa S, Foulcer S, Apte SS. 2014. The multiple, complex roles of versican and its proteolytic turnover by ADAMTS proteases during embryogenesis. Matrix Biol 35:34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mead TJ, Du Y, Nelson CM, et al. 2018. ADAMTS9-regulated pericellular matrix dynamics governs focal adhesion- dependent smooth muscle differentiation. Cell Rep 23: 485–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hakimi O, Ternette N, Murphy R, et al. 2017. A quantitative label-free analysis of the extracellular proteome of human supraspinatus tendon reveals damage to the pericellular and elastic fibre niches in torn and aged tissue. PLoS ONE 12:e0177656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kohler J, Popov C, Klotz B, et al. 2013. Uncovering the cellular and molecular changes in tendon stem/progenitor cells attributed to tendon aging and degeneration. Aging Cell 12: 988–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Shukunami C, Takimoto A, Oro M, et al. 2006. Scleraxis positively regulates the expression of tenomodulin, a differentiation marker of tenocytes. Dev Biol 298:234–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Azizan A, Holaday N, Neame PJ. 2001. Post-translational processing of bovine chondromodulin-I. J Biol Chem 276: 23632–23638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Docheva D, Hunziker EB, Fassler R, et al. 2005. Tenomodulin is necessary for tenocyte proliferation and tendon maturation. Mol Cell Biol 25:699–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Alberton P, Dex S, Popov C, et al. 2015. Loss of tenomodulin results in reduced self-renewal and augmented senescence of tendon stem/progenitor cells. Stem Cells Dev 24:597–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wight TN. 2017. Provisional matrix: a role for versican and hyaluronan. Matrix Biol 60–61:38–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Evanko SP, Angello JC, Wight TN. 1999. Formation of hyaluronan-and versican-rich pericellular matrix is required for proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 19:1004–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hattori N, Carrino DA, Lauer ME, et al. 2011. Pericellular versican regulates the fibroblast-myofibroblast transition: a role for ADAMTS5 protease-mediated proteolysis. J Biol Chem 286:34298–34310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Robbins JR, Vogel KG. 1994. Regional expression of mRNA for proteoglycans and collagen in tendon. Eur J Cell Biol 64: 264–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Waggett AD, Ralphs JR, Kwan APL, et al. 1998. Characterization of collagens and proteoglycans at the insertion of the human Achilles tendon. Matrix Biol 16:457–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gillard GC, Reilly HC, Bell-Booth PG, et al. 1979. The influence of mechanical forces on the glycosaminoglycan content of the rabbit flexor digitorum profundus tendon. Connect Tissue Res 7:37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Koob TJ. 1989. Effects of chondroitinase-ABC on proteoglycans and swelling properties of fibrocartilage in bovine flexor tendon. J Orthop Res 7:219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Berenson MC, Blevins FT, Plaas AHK, et al. 1996. Proteoglycans of human rotator cuff tendons. J Orthop Res 14: 518–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Scott A, Lian Ø, Roberts CR, et al. 2008. Increased versican content is associated with tendinosis pathology in the patellar tendon of athletes with jumper’s knee. Scand J Med Sci Sports 18:427–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wang VM, Bell RM, Thakore R, et al. 2012. Murine tendon function is adversely affected by aggrecan accumulation due to the knockout of ADAMTS5. J Orthop Res 30:620–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Posey KL, Coustry F, Hecht JT. 2018. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein: COMPopathies and beyond. Matrix Biol 71–72:161–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Mosher DF, Adams JC. 2012. Adhesion-modulating/matricellular ECM protein families: a structural, functional and evolutionary appraisal. Matrix Biol 31:155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kyriakides TR, Zhu YH, Smith LT, et al. 1998. Mice that lack thrombospondin 2 display connective tissue abnormalities that are associated with disordered collagen fibrillogenesis, an increased vascular density, and a bleeding diathesis. J Cell Biol 140:419–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bornstein P, Kyriakides TR, Yang Z, et al. 2000. Thrombo-spondin 2 modulates collagen fibrillogenesis and angio-genesis. J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc 5:61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Frolova EG, Drazba J, Krukovets I, et al. 2014. Control of organization and function of muscle and tendon by throm-bospondin-4. Matrix Biol 37:35–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.DiCesare P, Hauser N, Lehman D, et al. 1994. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) is an abundant component of tendon. FEBS Lett 354:237–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Smith RK, Zunino L, Webbon PM, et al. 1997. The distribution of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) in tendon and its variation with tendon site, age and load. Matrix Biol 16:255–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sodersten F, Ekman S, Eloranta M, et al. 2005. Ultrastructural immunolocalization of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) in relation to collagen fibrils in the equine tendon. Matrix Biol 24:376–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Coustry F, Posey KL, Maerz T, et al. 2018. Mutant cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) compromises bone integrity, joint function and the balance between adipogenesis and osteogenesis. Matrix Biol 67:75–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Piróg KA, Jaka O, Katakura Y, et al. 2010. A mouse model offers novel insights into the myopathy and tendinopathy often associated with pseudoachondroplasia and multiple epiphyseal dysplasia. Hum Mol Genet 19:52–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hubmacher D, Apte SS. 2011. Genetic and functional linkage between ADAMTS superfamily proteins and fibrillin-1: a novel mechanism influencing microfibril assembly and function. Cell Mol Life Sci 68:3137–3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Sakai LY, Keene DR. 2018. Fibrillin protein pleiotropy: acromelic dysplasias. Matrix Biol 80:6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Hubmacher D, Apte SS. 2015. ADAMTS proteins as modulators of microfibril formation and function. Matrix Biol 47:34–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Dietz HC, Cutting CR, Pyeritz RE, et al. 1991. Marfan syndrome caused by a recurrent de novo missense mutation in the fibrillin gene. Nature 352:337–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Belleh S, Zhou G, Wang M, et al. 2000. Two novel fibrillin-2 mutations in congenital contractural arachnodactyly. Am J Med Genet 92:7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Putnam EA, Zhang H, Ramirez F, et al. 1995. Fibrillin-2 (FBN2) mutations result in the Marfan-like disorder, congenital contractural arachnodactyly. Nat Genet 11: 456–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Ritty TM, Roth R, Heuser JE. 2003. Tendon cell array isolation reveals a previously unknown fibrillin-2-containing macromolecular assembly. Structure 11:1179–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kannus P. 2000. Structure of the tendon connective tissue. Scand J Med Sci Sports 10:312–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Pang X, Wu JP, Allison GT, et al. 2017. Three dimensional microstructural network of elastin, collagen, and cells in Achilles tendons. J Orthop Res 35:1203–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Green EM, Mansfield JC, Bell JS, et al. 2014. The structure and micromechanics of elastic tissue. Interface Focus 4: 20130058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Grant TM, Thompson MS, Urban J, et al. 2013. Elastic fibres are broadly distributed in tendon and highly localized around tenocytes. J Anat 222:573–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Godinho MSC, Thorpe CT, Greenwald SE, et al. 2017. Elastin is localised to the interfascicular matrix of energy storing tendons and becomes increasingly disorganised with ageing. Sci Rep 7:9713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Eekhoff JD, Fang F, Kahan LG, et al. 2017. Functionally distinct tendons from elastin haploinsufficient mice exhibit mild stiffening and tendon-specific structural alteration. J Biomech Eng 139:111003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Fang F, Lake SP. 2016. Multiscale mechanical integrity of human supraspinatus tendon in shear after elastin depletion. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 63:443–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Ritty TM, Ditsios K, Starcher BC. 2002. Distribution of the elastic fiber and associated proteins in flexor tendon reflects function. Anat Rec 268:430–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Boregowda R, Paul E, White J, et al. 2008. Bone and soft connective tissue alterations result from loss of fibrillin-2 expression. Matrix Biol 27:661–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Sengle G, Carlberg V, Tufa SF, et al. 2015. Abnormal activation of BMP signaling causes myopathy in Fbn2 null mice. PLoS Genet 11:e1005340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Hubmacher D, Taye N, Balic Z, et al. 2019. Limb-and tendon-specific Adamtsl2 deletion identifies a role for ADAMTSL2 in tendon growth in a mouse model for geleophysic dysplasia. Matrix Biol 82:38–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Le Goff C, Mahaut C, Wang LW, et al. 2011. Mutations in the TGFβ binding-protein-like domain 5 of FBN1 are responsible for acromicric and geleophysic dysplasias. Am J Hum Genet 89:7–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Le Goff C, Morice-Picard F, Dagoneau N, et al. 2008. ADAMTSL2 mutations in geleophysic dysplasia demonstrate a role for ADAMTS-like proteins in TGF-β bioavailability regulation. Nat Genet 40:1119–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Shu CC, Smith MM, Appleyard RC, et al. 2018. Achilles and tail tendons of perlecan exon 3 null heparan sulphate deficient mice display surprising improvement in tendon tensile properties and altered collagen fibril organisation compared to C57BL/6 wild type mice. PeerJ 6:e5120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Alexopoulos LG, Youn I, Bonaldo P, et al. 2009. Developmental and osteoarthritic changes in Col6a1-knockout mice: biomechanics of type VI collagen in the cartilage pericellular matrix. Arthritis Rheum 60:771–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Tiedemann K, Sasaki T, Gustafsson E, et al. 2005. Micro-fibrils at basement membrane zones interact with perlecan via fibrillin-1. J Biol Chem 280:11404–11412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Hayes AJ, Lord MS, Smith SM, et al. 2011. Colocalization in vivo and association in vitro of perlecan and elastin. Histo-chem Cell Biol 136:437–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Gubbiotti MA, Neill T, Iozzo RV. 2017. A current view of perlecan in physiology and pathology: a mosaic of functions. Matrix Biol 57-58:285–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Thorpe CT, Screen HRC. 2016. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. Adv Exp Med Biol 920:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Thorpe CT, Karunaseelan KJ, Ng Chieng Hin J, et al. 2016. Distribution of proteins within different compartments of tendon varies according to tendon type. J Anat 229:450–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Sun Y, Berger EJ, Zhao C, et al. 2006. Expression and mapping of lubricin in canine flexor tendon. J Orthop Res 24:1861–1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Taguchi M, Sun YL, Zhao C, et al. 2008. Lubricin surface modification improves extrasynovial tendon gliding in a canine model in vitro. J Bone Joint Surg Am 90:129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Sun YL, Wei Z, Zhao C, et al. 2015. Lubricin in human achilles tendon: the evidence of intratendinous sliding motion and shear force in achilles tendon. J Orthop Res 33: 932–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Kohrs RT, Zhao C, Sun YL, et al. 2011. Tendon fascicle gliding in wild type, heterozygous, and lubricin knockout mice. J Orthop Res 29:384–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Dyment NA, Liu CF, Kazemi N, et al. 2013. The paratenon contributes to scleraxis-expressing cells during patellar tendon healing. PLoS ONE 8:e59944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Dahlgren LA, Mohammed HO, Nixon AJ. 2005. Temporal expression of growth factors and matrix molecules in healing tendon lesions. J Orthop Res 23:84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Gelberman RH, Steinberg D, Amiel D, et al. 1991. Fibroblast chemotaxis after tendon repair. J Hand Surg [Am] 16: 686–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Singh P, Carraher C, Schwarzbauer JE. 2010. Assembly of fibronectin extracellular matrix. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 26: 397–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Södersten F, Hultenby K, Heinegård D, et al. 2013. Immunolocalization of collagens (I and III) and cartilage oligomeric matrix protein in the normal and injured equine superficial digital flexor tendon. Connect Tissue Res 54:62–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Vadon-Le Goff S, Kronenberg D, Bourhis JM, et al. 2011. Procollagen C-proteinase enhancer stimulates procollagen processing by binding to the C-propeptide region only. J Biol Chem 286:38932–38938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Xu H, Raynal N, Stathopoulos S, et al. 2011. Collagen binding specificity of the discoidin domain receptors: binding sites on collagens II and III and molecular determinants for collagen IV recognition by DDR1. Matrix Biol 30:16–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Somasundaram R, Schuppan D. 1996. Type I, II, III, IV, V, and VI collagens serve as extracellular ligands for the iso-forms of platelet-derived growth factor (AA, BB, and AB). J Biol Chem 271:26884–26891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, et al. 2015. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res 43:D447–D452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Smoot ME, Ono K, Ruscheinski J, et al. 2011. Cytoscape 2.8: new features for data integration and network visualization. Bioinformatics 27:431–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Wang S, Wang Y, Song L, et al. 2017. Decellularized tendon as a prospective scaffold for tendon repair. Mater Sci Eng 77: 1290–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Ning LJ, Zhang YJ, Zhang Y, et al. 2015. The utilization of decellularized tendon slices to provide an inductive microenvironment for the proliferation and tenogenic differentiation of stem cells. Biomaterials 52:539–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Ramesh R, Kumar N, Sharma AK, et al. 2003. Acellular and glutaraldehyde-preserved tendon allografts for reconstruction of superficial digital flexor tendon in bovines: Part II--Gross, microscopic and scanning electron microscopic observations. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med 50:520–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Ramesh R, Kumar N, Sharma AK, et al. 2003. Acellular and glutaraldehyde-preserved tendon allografts for reconstruction of superficial digital flexor tendon in bovines: Part I—clinical, radiological and angiographical observations. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med 50:511–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Dong S, Huangfu X, Xie G, et al. 2015. Decellularized versus fresh-frozen allografts in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: an in vitro study in a Rabbit Model. Am J Sports Med 43:1924–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Pan J, Liu GM, Ning LJ, et al. 2015. Rotator cuff repair using a decellularized tendon slices graft: an in vivo study in a rabbit model. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23: 1524–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Abbah SA, Thomas D, Browne S, et al. 2016. Co-transfection of decorin and interleukin-10 modulates pro-fibrotic extracellular matrix gene expression in human tenocyte culture. Sci Rep 6:20922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Galatz L, Rothermich S, VanderPloeg K, et al. 2007. Development of the supraspinatus tendon-to-bone insertion: localized expression of extracellular matrix and growth factor genes. J Orthop Res 25:1621–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Patel S, Gualtieri AP, Lu HH, et al. 2016. Advances in biologic augmentation for rotator cuff repair. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1383:97–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Thorpe CT, Chaudhry S, Lei II, et al. 2015. Tendon overload results in alterations in cell shape and increased markers of inflammation and matrix degradation. Scand J Med Sci Sports 25:e381–e391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Snedeker JG, Foolen J. 2017. Tendon injury and repair—a perspective on the basic mechanisms of tendon disease and future clinical therapy. Acta Biomater 63:18–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Dyment NA, Hagiwara Y, Matthews BG, et al. 2014. Lineage tracing of resident tendon progenitor cells during growth and natural healing. PLoS ONE 9:e96113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Kastelic J, Galeski A, Baer E. 1978. The multicomposite structure of tendon. Connect Tissue Res 6:11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.