Abstract

Background.

Regular physical activity is associated with improved physical and psychosocial well-being. Increasing access to physical activity in underresourced communities requires collaborative, community-engaged methods. One such method is community workgroups.

Purpose.

The purpose of this article is to describe implementation, strengths, challenges, and results of the workgroup approach as applied to increasing access to physical activity, using our recent study as an illustrative example.

Method.

A 1-day conference was held in April 2017 for community leaders. The first half of the conference focused on disseminating results of a multifaceted community assessment. The second half entailed community workgroups. Workgroups focused on applying community assessment results to develop strategies for increasing access to physical activity, with plans for ongoing workgroup involvement for strategy refinement and implementation. A professional artist documented the workgroup process and recommendations via graphic recording.

Results.

Sixty-three community leaders attended the conference and participated in the workgroups. Workgroup participants reported that greater macrosystem collaboration was critical for sustainability of physical activity programming and that, particularly in underresourced urban communities, re-imagining existing spaces (rather than building new spaces) may be a promising strategy for increasing access to physical activity.

Discussion.

Considered collectively, the community workgroup approach provided unique insight and rich data around increasing access to physical activity. It also facilitated stakeholder engagement with and ownership of community health goals. With careful implementation that includes attention to strengths, challenges, and planning for long-term follow-up, the community workgroup approach can be used to develop health promotion strategies in underresourced communities.

Keywords: physical activity/exercise, social determinants of health, health promotion

BACKGROUND

Increasing access to physical activity can improve well-being and reduce health disparities. Efforts to increase access to physical activity can benefit from community-engaged methods (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998; Minkler, 2000). However, one challenge of community-engaged methods is that they often result in large amounts of nontraditional data such as insight from Community Advisory Boards and community partners. Guidance on how to synthesize this nontraditional data can support use of community-engaged methods. In this article, we describe implementation and results of one community-engaged method—community workgroups—as applied to increasing access to physical activity.

DESCRIPTION OF WORKGROUP APPROACH

Workgroup Setting

This study was part of a 3-year parent study guided by the Socio-Ecological Model (McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, 1988). The parent study included a multifaceted community assessment about barriers to and facilitators of physical activity in West Philadelphia, an underresourced urban community that experiences many health disparities (Lipman et al., 2011; Pew Charitable Trusts, 2015; Philadelphia Department of Public Health, 2016; U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). Community assessment results demonstrated that community members experienced a key barrier to physical activity—lack of access to safe spaces to be active.

To gain community leaders’ insight on community assessment findings, we conducted workgroups during a 1-day conference on “Taking Action to Increase Physical Activity in Youth and their Families: Community/Academic Partnerships.” The conference was held in April 2017 at a university in West Philadelphia. The first half of the conference included dissemination of community assessment results and presentations from leaders of community organizations. The second half entailed workgroups. Conference attendees included community leaders from education (e.g., school health administrators), government (e.g., representatives from the city health department), and nonprofit sectors (e.g., leadership of school-based physical activity programs). The community leaders were invited due to their meaningful roles and/or influence in organizations focused on physical activity or health of West Philadelphians. Some were new partners, though many had been involved as members of the parent study’s Community Advisory Board. The conference was focused on community leaders because they could provide insight that was complementary to, though different than, that of the community members who participated in the community assessment.

Workgroup Structure

Workgroups were focused on addressing the barrier identified in our community assessment: lack of access to safe spaces for physical activity. Given the focus on spaces, we organized the workgroups into Community/Indoor Spaces Workgroup, an Outdoor/Green Spaces Workgroup, and a Before, During, and After School Spaces Workgroup. Conference attendees signed up for one of the workgroups during registration.

Workgroup Facilitation

Each workgroup met in a separate room. Workgroups were guided by Healthy Places by Design (see https://healthyplacesbydesign.org/), a consulting organization focused on turning visions of health into equitable and lasting impact. Each workgroup had two leaders: one from the consulting organization as a neutral facilitator and one from the research team. Two and a half hours were devoted to workgroups. The workgroups opened with introductions and a summary of the community assessment. Participants then independently brainstormed strategies for increasing access to physical activity in that workgroup’s setting. Participants worked in small groups to categorize strategies and then shared their strategies with the larger workgroup. The focus was on idea generation, with the perspective that “there are no bad ideas.” The participants were then given a break during which workgroup leaders condensed the strategies into categories and wrote them on large white boards. On reconvening, a modified Delphi group technique was employed to aid workgroup members in voting on three to five most salient strategies (Hasson, Keeney, & McKenna, 2000; Hsu & Sandford, 2007) based on impact, feasibility, and sustainability. Once three to five strategies were chosen collectively, the workgroups developed action steps for each strategy. After action steps were identified, a summary was provided by the workgroup leaders. The workgroup process then concluded, and the workgroups reconvened for the main conference. Conference closing included a presentation of each workgroup’s strategies and plans for advancing action steps. Coupled with the presentation was a graphic recording by a professional artist. The graphic recording served as an engaging way of documenting workgroups’ efforts and provided a novel resource for dissemination. The graphic recording was used to document the workgroups’ recommendations in a visually engaging way that depicted conversation character. The artist observed the workgroups’ presentations of their strategies and concurrently sketched themes, ideas, and conclusions. Following the conference, the artist used notes from the workgroup presentations to refine the final graphic recording.

Data Sources

Sources of data included notes taken during each workgroup by their identified recorder, photographs of white boards/Post-It notes used for brainstorming during the workgroup sessions, and the graphic recording. Following the conference, the team met to debrief, review the data, and write a summary report.

WORKGROUP RECOMMENDATIONS

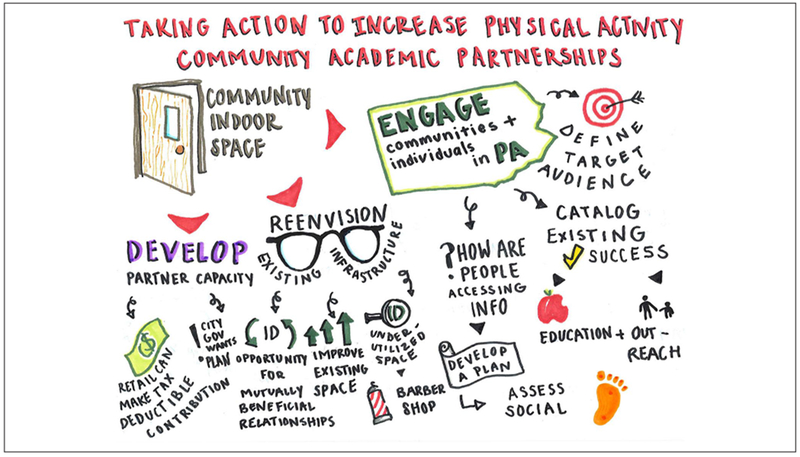

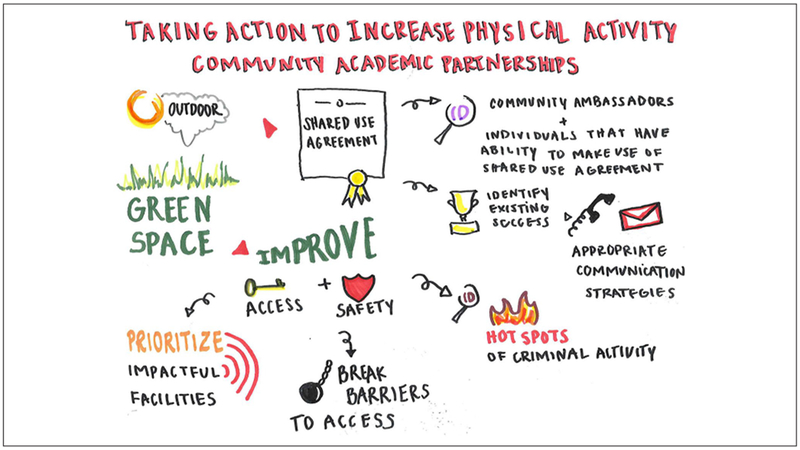

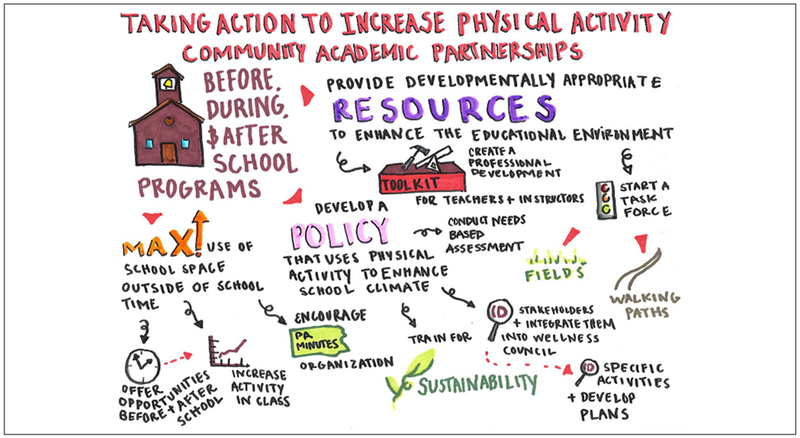

Sixty-three conference attendees participated in the workgroups with 13 participants in the Community/Indoor Space workgroup, 13 participants in the Green/Outdoor Space Workgroup, and 37 in the Before, During, and After School Workgroup. Each workgroup described strategies for increasing access to physical activity within their specific spaces. Workgroup strategies are summarized below and via graphic recording in Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3.

FIGURE 1. The Community/Indoor Spaces Workgroup.

This workgroup identified three strategies for increasing physical activity in community/indoor spaces: increasing community’s engagement in the space and activities, re-envisioning use of existing indoor spaces for physical activity, and developing partner capacity and sustained leadership with community organizations focused on physical activity.

FIGURE 2. The Green/Outdoor Spaces Workgroup.

This workgroup identified three strategies for increasing physical activity in outdoor/green spaces: increasing safety including both improving physical infrastructure and decreasing crime/violence, creating shared use agreements with organizations hosting green/outdoor space related to access, and cultivating champions for physical activity who hold positions of both formal and informal power.

FIGURE 3. The Before, During, and After School Workgroup.

This workgroup identified three strategies for increasing physical activity in the school setting: providing physical activity resources that align with quality education, developing a policy that uses physical activity to enhance school climate and wellness, and maximizing the use of school space and out-of-school time to create a culture of physical activity.

Collectively, the workgroup strategies fell under two themes. Strengths and challenges of the workgroup approach were noted, though challenges were manageable with careful planning.

Workgroup Strategies for Increasing Access to Physical Activity

The Community/Indoor Space Workgroup identified three strategies: increase engagement, reenvision use of existing spaces, and develop partner capacity and sustained leadership within community organizations. The Green/Outdoor Space Workgroup recommended three strategies: improve safety including infrastructure and crime/violence, create shared use agreements related to access, and cultivate champions in positions of formal and informal power. The Before, During, and After School Workgroup suggested three strategies: provide physical activity resources that could enhance a quality educational environment, develop a policy that uses physical activity to enhance school climate and improve school wellness, and maximize the use of school space and out-of-school time to create a culture of physical activity.

Themes

The output of the three workgroups was synthesized into two themes.

Develop Macrosystem Collaboration and Coordination to Sustain Physical Activity Improvements.

All workgroups identified the need for macrosystem collaboration for development of sustainable policies, systems, and programs. Relationship building and leadership was described as vital to success and sustainability. The importance of formal and informal community leaders and organizations (e.g., universities, health care systems) was highlighted. Leaders of community organizations described feeling as if they sometimes worked as an island but believed that with deeper integration, they could increase physical activity in a way that was safe and welcoming. Workgroup participants also suggested identifying stakeholders that were not currently involved but could advance physical activity goals. Empowerment and leadership training of community members was seen as essential for engagement and promoting community members’ potential to determine, advocate for, and shape solutions.

Leverage and Reimagine Existing Spaces for Inclusive Physical Activity Opportunities.

Participants noted that, similar to many urban areas, West Philadelphia does not have a much available land for development of new physical activity spaces. However, it has parks, schools, and community spaces that could be reimagined as safe, accessible spaces for physical activity. Barriers to transforming existing spaces were identified, including private ownership or being closed to the community during key hours. Participants highlighted the potential for change by partnering with gatekeepers (e.g., principals, property owners) who have the authority to modify policies related to access. Participants felt that there was great potential to rediscover, reclaim, or reimagine existing spaces to make them more welcoming (e.g., more lighting, add public art).

REFLECTIONS ON THE WORKGROUP APPROACH

This study used a community workgroup approach to provide insight into strategies for increasing physical activity in an underresourced urban community. Our findings demonstrate that community leaders see macrosystem collaboration as key to expanding access to physical activity. Community leaders felt as if programs could benefit from collaboration, increased access to resources through partnerships, and leadership training. Lack of coordination was seen as a barrier that could be overcome. Building new spaces wasn’t seen as necessary; the community leaders identified existing spaces that were underutilized or could be used for physical activity.

Macrosystem solutions, such as those identified by the community leaders, necessitate focusing on more than individual health behavior change. Macrosystem changes may require engagement of powerful organizations (e.g., anchor institutions) and local government to improve coordination and communication. The collaboration could be mutually beneficial by providing smaller groups with the resources of powerful partners while giving anchor institutions insight from on-the-ground leaders. Another way to facilitate macrosystem change would be to work with organizations to create grants that require collaboration among organizations. Such grants could incentivize resource pooling, communication, and imagining solutions beyond what one organization can provide.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Using the workgroup approach created an opportunity for community leaders with a breadth of experiences to strategize around a shared goal. While the workgroup approach required a great deal of coordination, planning, and consulting with outside experts, it resulted in a wealth of data and strengthening of partnerships that made the investment worthwhile.

Strengths of Workgroup Approach

The community workgroup approach has multiple strengths. Perhaps most important, it brought community leaders together in a way that promoted mutual engagement in solutions. Connecting community leaders with diverse perspectives led to a synergy that may not have been possible in smaller, more prescribed groups. The approach also created a space devoid of power structures and that acknowledged the value of all perspectives. Furthermore, the workgroups facilitated enthusiastic discussions—such interaction may not have been possible without being physically together. Importantly, the workgroup approach allowed for a wide breadth of community leaders to engage, incorporating perspectives of individuals not previously involved. Last, the workgroup approach supported the structured synthesis of extensive amounts of data.

Challenges With Workgroup Approach

In addition to its strengths, the workgroup approach presented challenges that must be considered prior to employing this method. The primary challenge related to resource-intensiveness. Substantial time for planning, of both the research team and parent study’s Community Advisory Board, was required. Knowledge of, and existing relationships with, the community was a less tangible but important resource; it likely positively influenced participants’ attendance and engagement. The community assessment that informed the workgroup’s efforts entailed 2 years of research, with associated costs, time, and expertise. Funds were needed to support conference costs, and a consulting organization was involved to support workgroup execution. Although outside expertise from the consulting organization was extremely helpful in implementing our workgroup approach, communities should assess their own local capacity to determine their need and budget for outside expertise. Collaborative planning and sharing to maximize local expertise and resources can reduce the need for outside consultants and increase collaboration within and across sectors. Of note, we describe the resource-intensiveness not to deter from the workgroup approach but to highlight the need for thoughtful resource planning. The conference during which these workgroups took place was part of a National Institutes of Health–funded study; however, it would be possible to implement workgroups with fewer resources. For example, protected time for planning could be provided for individuals working in government or nonprofits. While the approach reported in this study entailed a baseline assessment by a research team, others could capitalize on existing assessments by local government, nonprofits, health systems, or academic institutions. Many organizations already possess the required community connections and knowledge. A second challenge was keeping members engaged after the conference because the workgroup approach is a process—not a one-time event. Careful planning for follow-up and opportunities to participate in next steps was important to fostering trust, deepening relationships, and facilitating ongoing engagement.

MOVING TOWARD HEALTH EQUITY

More equitable participation in physical activity can decrease health disparities. While the workgroup approach presents some challenges and requires careful planning, it can provide unique insight into improving health from the perspective of community leaders. The approach counters the traditional model of doing “for” the community by setting the stage for community members to lead change. With a focus on innovative and collaborative approaches to increasing access to physical activity, strategies can be developed to promote health and reduce health disparities in underresourced communities.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the project managers, Amani Abdallah and Ansley Bolick, who played a critical role in organizing the conference and coordinating the associated study. In addition, we would like to acknowledge Tim Schwantes from Healthy Living by Design for his key contributions in planning and executing the conference and workgroups and synthesizing the workgroup data. Last, we want to thank the members of the workgroups for sharing their important insight into increasing access to physical activity in West Philadelphia. This publication was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research (T32NR007100) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R13HD085960). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- Hasson F, Keeney S, & McKenna H (2000). Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32, 1008–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C-C, & Sandford BA (2007). The Delphi technique: Making sense of consensus. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 22(10), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, & Becker AB (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipman TH, Schucker MM, Ratcliffe SJ, Holmberg T, Baier S, & Deatrick JA (2011). Diabetes risk factors in children: A partnership between nurse practitioner and high school students. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 36, 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, & Glanz K (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education & Behavior, 15, 351–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M (2000). Using participatory action research to build healthy communities. Public Health Reports, 115, 191–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Charitable Trusts. (2015). Philadelphia 2015: The state of the city. Retrieved from https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2015/11/2015-state-of-the-city-report_web_v2.pdf

- Philadelphia Department of Public Health. (2016). Community health assessment. Retrieved from https://www.phila.gov/media/20181105154518/2016-CHA-Slides_updatedPHC4.pdf

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2017). American fact finder. Retrieved from https://factfinder.census.gov/