Abstract

Background:

There is an increasing focus in the emergency department (ED) on addressing the needs of persons with cognitive impairment, most of whom have multiple chronic conditions. We investigated which common comorbidities among multimorbid persons with cognitive impairment conferred increased risk for ED treat and release utilization.

Methods:

We examined the association of 16 chronic conditions on use of ED treat and release visit utilization among 1006 adults with cognitive impairment and ≥2 comorbidities using the nationally-representative National Health and Aging Trends Study merged with Fee-For-Service Medicare claims data, 2011–2015.

Results:

At baseline, 28.5% had ≥6 conditions and 35.4% were ≥85 years old. After controlling for sex, age, race, education, urban-living, number of disabled activities of daily living, and sampling strata, we found significantly increased adjusted risk ratios (aRR) of ED treat and release visits for persons with depression (aRR 1.38 95% CI 1.15–1.65) representing 78/100 person-years, and osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis (aRR 1.32 95% CI 1.12–1.57) representing 71/100 person-years. At baseline 93.9% had ≥1 informal caregiver and 69.7% had a caregiver that helped with medications or attended physician visits.

Conclusion:

These results show that multimorbid cognitively impaired older adults with depression or osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis are at higher risk of ED treat and release visits. Future ED research with multimorbid cognitively impaired persons may explore behavioral aspects of depression and/or pain and flairs associated with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, as well as the role of informal caregivers in the care of these conditions.

Keywords: Dementia, Multiple chronic conditions, National Health and Aging Trends study, Longitudinal study, Public health, Emergency department and Utilization

1. Introduction

Dementia, a devastating, chronic condition known for its cognitive and memory loss leading to total reliance, has a prevalence of 8.8% among persons 65 years and older in the United States [1]. Estimated total societal costs for dementia in 2010 varied between $157 billion and $215 billion and 2040 projections dramatically increase [2]. In the emergency department (ED), there is an increasing emphasis on improving the value of emergency care for older adults, particularly those with dementia [3]. Research on dementia care management programs outside the hospital setting have been identified as a priority in the field [4].

Most persons with dementia have an average of 2.1 other chronic medical conditions [5] with 61% of Alzheimer’s patients having three or more comorbid medical illnesses [6]. Furthermore, dementia severity is correlated with comorbid condition severity, such as genitourinary disorders [7]. However, to date, little is known whether co-existing chronic conditions contribute to ED visits for persons with dementia [7, 8]. Previous work has shown that poor management of chronic conditions increases the risk of healthcare utilization [9, 10], dependence in functional activities, and death [11, 12]. We know that persons with multiple chronic conditions are vulnerable to exacerbations of, and complications from, their underlying disease, and are susceptible to other acute illnesses, some of which may be potentially averted (e.g. pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and congestive cardiac failure) [6, 13, 14]. And we know that among persons with a dementia diagnosis at or prior to the time of an ED visit, between 37%−54% visited the ED in a given year compared to 20%−31% without a dementia diagnosis [15]. Moreover, persons with dementia experienced poorer outcomes including mortality and worse physical function after hospitalization [15–17]. There is limited existing data examining ED utilization among older adults with and without dementia [15] but none of this research has looked specifically at patients with multimorbidity. We investigated which common comorbidities among multimorbid persons with cognitive impairment higher annualized rates and conferred increased risk for ED treat and release visits. We focused specifically on chronic conditions with increased likelihood to be stabilized in the ED prior to being determined safe for discharge rather than admitted for hospitalization as different conditions may be associated with hospitalization than ED treat and release.

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources

Five annual waves of National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) were merged with Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Claims Data from 2011–2015 [18]. The NHATS is an ongoing nationally-representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries designed to understand trends and trajectories of late-life disability [18]. It gathers information on participants’ cognitive and physical functioning, social support, and demographic information. Medicare claims that were linked to the NHATS included validated chronic conditions and emergency outpatient visits [ [19].

The study protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board and the Yale Institutional Review Board (HIC# 1510016585). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants or their proxy respondents.

2.2. Study population

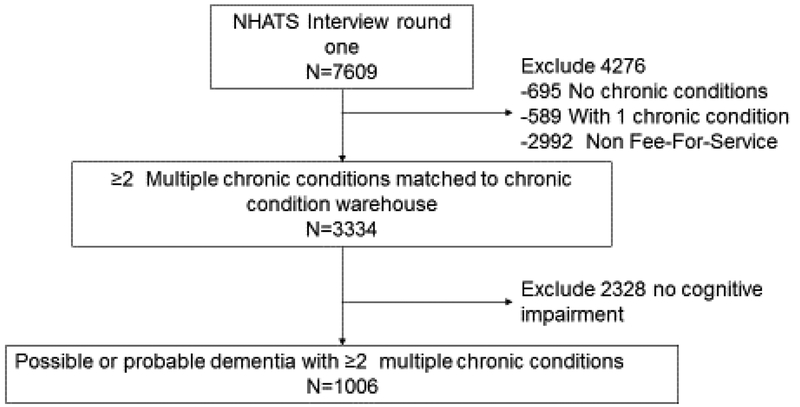

Our study sample included NHATS respondents who were 65 and older who were Medicare Fee-For-Service beneficiaries and whose NHATS’ data were linked to CMS Claims Data. Medicare managed care enrollees were excluded because no claims data were available. NHATS assessed cognitive status based on reports of clinical diagnosis, proxy responses to the Alzheimer’s disease 8 Dementia Screening interview and cognitive testing [20, 21], which classified each as having no dementia, possible dementia or probable dementia [20]. For the current study, we included 1,006 participants with possible or probable dementia [22] that had two or more other chronic conditions (defined below) based on Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse algorithms [19] from the five annual waves of NHATS for the period 2011–2015 (Figure 1). We define the study population as persons with cognitive impairment.

Figure 1:

Consort Diagram of Multimorbid Persons with Dementia Among Fee-For Service Medicare Beneficiaries in the National Health and Aging Trends Study in 2011 (n=1006).

2.3. Measures

Baseline fixed demographic characteristics for all models included the following: age bands (65–74, 75–84 and ≥85 years), sex, race (non-Hispanic white versus other), number of disabled activities of daily living (eating, dressing, bathing, toileting, transferring from bed, and getting around inside one’s home), education (less than high school versus high school or greater), municipality (urban versus rural) and sampling strata. Time-varying chronic conditions from Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse were acute myocardial infarction, asthma, atrial fibrillation, benign prostatic hyperplasia, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, diabetes, heart failure, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, hypothyroidism, ischemic heart disease, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis, and stroke or transient ischemic attack. None of these covariates were correlated greater than 0.4 to limit collinearity.

2.4. Outcome: Emergency Department Visits

The primary outcome was annual count of emergency department treat and release visits.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics of baseline demographics of the cohort used NHATS analytic weights that provide nationally-representative estimates and take into account differential probabilities of selection and nonresponse [23]. Furthermore, to address death and drop-out over the five-year follow-up, we fit a propensity model predicting response in the 2015 wave using baseline 2011 characteristics associated with a p-value of < .20 [24] including the 2011 survey weights. The 2011 survey weights were then multiplied by the inverses of the mean estimated response probabilities within deciles of the response probabilities. Visits of deceased persons were set to zero [24]. For the longitudinal analysis, we multiplied the NHATS analytical weights by the inverse probability of response in 2015 to adjust for non-response and included the sampling stratum as a covariate [24]. Total number of annual ED treat and release visits were modeled using a weighted Generalized Estimating Equations Poisson regression to account for the repeated measures with unstructured covariance; this resulted in adjusted risk ratios (aRR). Stata v15 was used with two-sided significance tests with a Bonferroni corrected Type I error of 0.003 to adjust for 16 inference tests on the chronic conditions [25].

3. Study Results

A total of 1006 NHATs participants met eligibility criteria and were included in analyses (Figure 1); of these 214 (21.3%) discontinued follow-up and 499 (49.6%) died prior to the end of the study period (2015). The median follow-up was 28 months (interquartile range [IQR], 13–48 months). The baseline characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1 and generalizes to approximately 3.6 million Medicare Fee-For-Service adults beneficiaries having probable or possible dementia with at least two of the 16 chronic conditions. The majority (85.6%) were community-dwelling at baseline, while 14.4% were in residential settings, such as assisted-living communities. Nearly all (93.9%) had at least 1 informal caregiver and 69.7% had a caregiver which helped them with medications or attended physician visits.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics Of Medicare Fee-For-Service Beneficiaries With Dementia From The National Health And Aging Trends Study With 2 Or More Chronic Conditions In 2011.

| Characteristic | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Estimated sample population | 3,634,491 |

| Sociodemographic | |

| Age | |

| 65–74 | 24.4 |

| 75–84 | 40.2 |

| 85+ | 35.4 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 43.5 |

| Female | 56.6 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 74.3 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 10.1 |

| Hispanic | 4.9 |

| Other | 10.7 |

| Education | |

| ≥ High School | 39.2 |

| < High School | 60.2 |

| Activities of daily living score (0–6)a | |

| 0 | 58.6 |

| 1 | 13.1 |

| 2 | 8.2 |

| 3 | 5.2 |

| 4 | 3.5 |

| 5 | 4.1 |

| 6 | 7.0 |

| Chronic Conditionsb | |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 1.8 |

| Asthma | 7.5 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 13.5 |

| Benign prostatic hyperplasia | 11.4 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 20.4 |

| Cognitive statusc | |

| Possible dementia | 45.7 |

| Probable dementia | 54.3 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 28.0 |

| Depression | 21.3 |

| Diabetes | 41.0 |

| Heart failure | 32.7 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 65.2 |

| Hypertension | 82.7 |

| Hypothyroidism | 16.3 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 51.0 |

| Osteoporosis | 12.6 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis | 46.6 |

| Stroke or transient ischemic attack | 8.6 |

| # of Chronic conditionsd | |

| 2–3 conditions | 35.0 |

| 4–5 conditions | 36.5 |

| 6+ conditions | 28.5 |

The definition of disability is a deficit in eating, dressing, bathing, toileting, transferring from bed, getting around inside one’s home. Higher scores indicate greater disability.

Chronic conditions were based on CMS chronic condition data warehouse.

Dementia classification is based on NHATS data interviews.

Chronic condition was the sum score of listed 16 conditions.

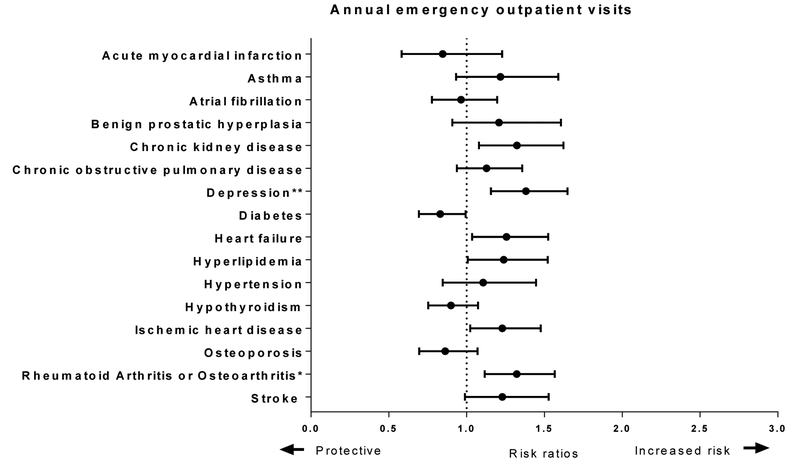

Figure 2 shows adjusted risk ratio (aRR) and adjusted rates per 100 person-years for the annual number of ED visits for persons with cognitive impairment and at least two other chronic conditions. After adjusting for covariates, death and losses to follow-up, as well as survey design, we found increased adjusted risk ratios (aRR) of ED visits for those with depression (aRR 1.38 95% CI 1.15 – 1.65) and rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis (aRR 1.32 95% CI 1.12 – 1.57).

Figure 2.

Risk Ratios and Rates of Emergency Department Discharged Home for Multimorbid Persons with Dementia Among Fee-For Service Medicare Beneficiaries in the National Health and Aging Trends Study Data Linked with Medicare Claims, 2011–2015

The figure shows adjusted risk ratios from a weighted generalized estimating equations Poisson regression and rates. The regression model included all 16 chronic conditions, sex, age band, education, race, urban environment, count of disabled activities of daily living, sampling stratum variable and were weighted for drop out. * indicates that the marginal weighted estimate was significant at a Bonferroni corrected Type I error of p<0.003 and ** is a p<0.0001.

Although Figure 2 shows that chronic kidney disease, heart failure and ischemic heart disease aRR do not cross 1.0 (null values), by using Bonferroni corrected p-values, these did not meet significance. However, future research may consider these often interrelated chronic conditions potentially higher risk of ED treat and release visits.

4. Discussion

In this nationally-representative, longitudinal, prospective study of non-institutionalized older adults with cognitive impairment, depression, osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis were significantly associated with ED treat and release visits. Our research with a nationally-representative cohort focuses specifically on ED treat and release visit for multimorbid persons with cognitive impairment, which, to our knowledge, has not previously been pursued. By estimating the aRR and annual rates of ED treat and release visits for individual chronic conditions, we quantified what has been suspected clinically. Although we found the annual rates to be substantial, it is the ratio of those with a given conditions relative to those without that condition that drives the estimates of aRR of ED treat and release visits. This is of importance for optimizing ED care of older adults with cognitive impairment.

Previous research by LaMantia et al. has shown that ED utilization and ED-associated costs are higher for older adults with dementia as compared to older adults without dementia [15]. Our research takes the next step by looking at the influence of multimorbidity on persons’ use of the ED. However, they used ICD-10 codes in medical records to identify dementia, whereas we used the NHATS validated dementia screening tool, which includes clinical diagnosis, proxy responses to the Alzheimer’s disease 8 Dementia Screening interview and cognitive testing [20, 21].

We postulate that these findings of conditions associated with ED treat and release may be inter-related through pain. Osteoarthritis and/or rheumatoid arthritis are associated with pain. The progression of cognitive impairment substantially affects the motivational and cognitive structures of the pain network, usually responsible for properly assigning the meaning to pain [26]. Moreover, cognitive impairment is commonly accompanied by neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as depression and its manifestations. The causes of these symptoms are based on chemical, anatomical, and transmitter changes in the brain and/or related to unmet needs. One trigger for neuropsychiatric symptoms may be undiagnosed and untreated pain [27]. Among cognitively impaired persons, difficulty in communicating may lead to inadequate pain assessment and poor pain management particularly among hospitalized patients [28]. Tying pain and behavior together, Husebø et al. [29] found patients with dementia are unable to articulate the specific nature and severity of pain and Sampson et al.[30] found that instead of verbal cues they may exhibit aggression, agitation, anxiety or disrupted sleep and even delirium. Most of the instruments to assess pain in older adults with cognitive impairment are based on the American Geriatrics Society Panel that pain can be expressed by changes in facial expression (e.g., frowning), vocalization and verbalization (e.g., groaning, mumbling), and body movements [31]. These behavioral changes in the context of pain may be unrecognized in the ED setting and by informal caregivers. Unfortunately, symptoms, such as pain, that may be the cause of the ED treat and release visit were not recorded in the CMS Claims Data; thus, only the conditions that may give rise to pain (e.g. osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis) and its presentation (e.g. depression) were found to be associated. There are many conditions which elicit pain, but these may result in hospital admission to treat the underlying causes.

This study has some limitations. The CMS data linked to NHATS were specific to Medicare Fee-For-Service beneficiaries, as data were unavailable from Medicare Advantage plans. However, by using the survey weights, the results reflect national estimates for Medicare Fee-For-Service beneficiaries. Secondly, in this aged and chronically ill cohort, 49.6% died over the five-year follow-up. To address this, we undertook a rigorous analysis to account for death and losses to follow-up. Thirdly, residence type was multiply collinear with chronic conditions and not included in the models; at baseline 85.6% were community-dwelling and NHATS discontinues follow-up after moving to a long-term nursing home. Fourthly, we used a very conservative Bonferroni corrected p-value then defining significance; thus, chronic kidney disease, heart failure and ischemic heart disease all had increased aRR of ED treat and release but did not meet this conservative p-value. However, we present the 95% confidence intervals and annual rates for all 16 conditions. Fifthly, we limited this analysis to ED visits that did not result in hospital admission. Some of the 16 chronic conditions studies may have a greater likelihood of hospital admission, but that is beyond the scope of this paper. Sixthly, we do not have symptoms, such as pain. Lastly, we present associations with ED treat and release visits and these do not imply causation.

This paper underscores the significant effect of comorbidities on ED utilization of patients with cognitive impairment, highlighting the importance of future ED research on dementia patients considering multimorbidity. Future research should evaluate causes for ED visits and whether these lead to hospitalization.

5. Conclusion

Results from this study show that co-occurring chronic conditions are associated with ED treat and release among multimorbid persons with cognitive impairment. Future ED research with multimorbid cognitively impaired persons may explore behavioral aspects of depression and/or pain associated with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, as well as the role of informal caregivers in the care of these conditions.

6. Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Institute on Aging grant [R01 AG047891–01A1, P50AG047270 and a P30AG021342–16S1 (H.G.A and J.L.M.V.)], and the Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center P30AG021342). This work was additionally supported by a James Hudson Brown- Alexander Brown Coxe fellowship (J.L.M.V.). The National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG032947) through a cooperative agreement with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Funding sources were not involved in the creation of this work.

We acknowledge with much gratitude the following people for their invaluable help: Brent Vander Wyk and Linda Leo-Summers for their data management expertise; and Steven Heeringa and Mary Thompson for their advice on the survey weights. Publicly available data were obtained from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) and Center for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

NOTES

- [1].Langa KM, Larson EB, Crimmins EM, Faul JD, Levine DA, Kabeto MU, et al. A Comparison of the Prevalence of Dementia in the United States in 2000 and 2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:51–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hurd MD, Martorell P, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:489–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hwang U, Shah MN, Han JH, Carpenter CR, Siu AL, Adams JG. Transforming emergency care for older adults. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2013;32:2116–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mitchell SL, Black BS, Ersek M, Hanson LC, Miller SC, Sachs GA, et al. Advanced Dementia: State of the Art and Priorities for the Next Decade. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012;156:45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gerritsen AA, Bakker C, Verhey FR, de Vugt ME, Melis RJ, Koopmans RT, et al. Prevalence of Comorbidity in Patients With Young-Onset Alzheimer Disease Compared With Late-Onset: A Comparative Cohort Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Doraiswamy PM, Leon J, Cummings JL, Marin D, Neumann PJ. Prevalence and impact of medical comorbidity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:M173–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Tolppanen AM, Taipale H, Purmonen T, Koponen M, Soininen H, Hartikainen S. Hospital admissions, outpatient visits and healthcare costs of community-dwellers with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:955–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Chronic Conditions among Medicare Beneficiaries. 2012 ed. Baltimore, MD: 2012. p. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Donze J, Lipsitz S, Bates DW, Schnipper JL. Causes and patterns of readmissions in patients with common comorbidities: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2013;347:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Alonso-Moran E, Nuno-Solinis R, Onder G, Tonnara G. Multimorbidity in risk stratification tools to predict negative outcomes in adult population. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26:182–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gill TM, Allore HG, Gahbauer EA, Murphy TE. Change in disability after hospitalization or restricted activity in older persons. JAMA. 2010;304:1919–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, Guo Z. Hospitalization, restricted activity, and the development of disability among older persons. JAMA. 2004;292:2115–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Levine S, Steinman BA, Attaway K, Jung T, Enguidanos S. Home care program for patients at high risk of hospitalization. American Journal of Managed Care. 2012;18:e269–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Brown RS, Peikes D, Peterson G, Schore J, Razafindrakoto CM. Six features of Medicare coordinated care demonstration programs that cut hospital admissions of high-risk patients. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2012;31:1156–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].LaMantia MA, Stump TE, Messina FC, Miller DK, Callahan CM. Emergency Department Use Among Older Adults With Dementia. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2016;30:35–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hoogerduijn JG, Schuurmans MJ, Duijnstee MS, de Rooij SE, Grypdonck MF. A systematic review of predictors and screening instruments to identify older hospitalized patients at risk for functional decline. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:46–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Phelan EA, Borson S, Grothaus L, Balch S, Larson EB. Association of incident dementia with hospitalizations. JAMA. 2012;307:165–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kasper JD, Freedman VA. Findings from the 1st round of the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS): introduction to a special issue. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69 Suppl 1:S1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pope GC, Ellis RP, Ash AS, Ayanian JZ, Bates DW, Burstin H, et al. Diagnostic Cost Group Hierarchical Condition Category Models for Medicare Risk Adjustment. Health Economics Research, Inc; 2000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kasper JD, Freedman VA, Spillman BC. Classification of Persons by Dementia Status in the National Health and Aging Trends Study. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Galvin JE, Roe CM, Powlishta KK, Coats MA, Muich SJ, Grant E, et al. The AD8: a brief informant interview to detect dementia. Neurology. 2005;65:559–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Spillman BC, SAS MES programming statements for construction of dementia classification in the National Health and Aging Trends Study Addendum to NHATS Technical Paper #5. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Montaquila J, Freedman VA, Spillman B, Kasper JD. National Health and Aging Trends Study Development of Round 1 Survey Weights NHATS Technical Paper #2. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Heeringa S, BT W, BA B. Applied Survey Analysis, Second edition Boca Raton: CRC Press; Taylor and Francis Group; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [25].StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX StataCorp LP; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Corbett A, Husebo B, Malcangio M, Staniland A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Aarsland D, et al. Assessment and treatment of pain in people with dementia. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:264–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Husebo BS, Ballard C, Aarsland D. Pain treatment of agitation in patients with dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:1012–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].van Dalen-Kok AH, Pieper MJ, de Waal MW, Lukas A, Husebo BS, Achterberg WP. Association between pain, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and physical function in dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Husebo BS. Mobilization-Observation-Behaviour-Intensity-Dementia-2 Pain Scale (MOBID-2). J Physiother. 2017;63:261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sampson EL, White N, Lord K, Leurent B, Vickerstaff V, Scott S, et al. Pain, agitation, and behavioural problems in people with dementia admitted to general hospital wards: a longitudinal cohort study. Pain. 2015;156:675–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. Pain Med. 2009;10:1062–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]