Abstract

Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) requires patients and caregivers to infuse antimicrobials through venous catheters (VCs) in the home. The objective of this study was to perform a patient-centered goal-directed task analysis to identify what is required for successful completion of OPAT. The authors performed 40 semi-structured patient interviews and 20 observations of patients and caregivers performing OPAT-related tasks. Six overall goals were identified: (1) understanding and developing skills in OPAT, (2) receiving supplies, (3) medication administration and VC maintenance, (4) preventing VC harm while performing activities of daily living, (5) managing when hazards lead to failures, and (6) monitoring status. The authors suggest that patients and caregivers use teach-back, take formal OPAT classes, receive visual and verbal instructions, use cognitive aids, learn how to troubleshoot, and receive clear instructions to address areas of uncertainty. Addressing these goals is essential to ensuring the safety of and positive experiences for our patients.

Keywords: outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy, home care, home infusion therapy, task analysis, human factors engineering

To decrease length of hospital stays and reduce costs, complex medical therapies are increasingly provided in homes. One such therapy, outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT), is a particularly complex and high-risk treatment in which patients and their caregivers infuse parenteral antimicrobial therapy through venous catheters (VCs). Patients receiving OPAT are at risk for complications such as those from VCs, medications, and the infection being treated.1 However, little work has focused on patient perspectives on the performance of complex health care tasks such as those required for OPAT.2–4

To understand how to decrease OPAT complications, one needs to characterize the tasks patients and informal caregivers (“caregivers”) perform in OPAT. Task analysis is a human factors engineering method that has been used to describe the complex work of professional care providers5–8 and more recently patient self-management.5,9–12 Patient self-management task analysis has focused on tasks such as management of oral medications at the hospital-to-home transition,5 on performance of activities of daily living while managing a chronic condition,10,11 or on shared caregiver–nurse tasks.13 OPAT, on the other hand, requires patients and caregivers to accomplish tasks that highly-skilled health care workers (eg, nurses) perform in hospitals. Task analysis has not been used to understand patient-performed tasks that require as high a level of competency as those required for OPAT.

The research team elected to perform goal-directed task analysis (GDTA) because (1) it takes a patient-centered view by focusing on the goals (eg, taking a medication on time) and subgoals (eg, opening a pill bottle) of an individual working in a system (here, the patient working within the patient work system—their home14) and the tasks and subtasks required to achieve these goals and (2) it better describes the highly-complex, cognitively-intense processes required for OPAT completion than traditional task analysis, which typically focuses on one task constrained in space and time.15 The objectives of this study are to (1) perform a GDTA of patient and caregiver-performed OPAT and (2) through the identified goals, describe associated hazards to and strategies for the successful performance of OPAT.

Methods

This study was conducted in the context of a larger, previously-described qualitative project focused on patient and caregiver performance of home-based OPAT.16 The institutional review board at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine approved this study.

Approach

Two qualitative approaches were used to understand patient perceptions of and patient and caregiver performance of OPAT-related tasks. With one approach, the research team performed semi-structured telephone interviews with OPAT patients. These semi-structured interviews involved using an interview guide to lead a conversation, and patients and interviewers could address other topics that arose. With another approach, the team performed contextual inquiries of patients and caregivers performing OPAT-related tasks at home 3 to 14 days post hospital discharge (eg, medication infusion, VC care), with second visits just prior to completion of therapy for a subset of patients on ≥4 weeks of OPAT.16 Contextual inquiry involves observing workers (patients and caregivers) in their work system (the home) while they perform tasks (eg, VC maintenance, antimicrobial administration) and asking questions to understand motivations, approaches, and strategies.17,18 The timing of the contextual inquiry allowed for a focus on patient and caregiver task performance instead of home health nurseled training (as training typically occurs <1 day but occasionally 2 days post discharge).

Setting and Sample

The research team started with a convenience sample of patients discharged from 2 academic medical centers on OPAT. As the team was interested in the perspectives of adult rather than pediatric patients, eligible patients were ≥18 years of age, able to speak and read English, able to provide written consent, not in hospice care, and receiving OPAT after discharge from one of 2 academic medical centers. Patients could have used any home infusion or home nursing agency for medications and supplies, and training and support, respectively. Although the 2 academic medical centers had an affiliated home infusion and home nursing agency, the team wanted to describe a breadth of experiences, including those using different agencies. Therefore, the team performed purposive sampling within the convenience sample, including from unaffiliated home infusion agencies.16

Patients eligible for semi-structured telephone interviews had earlier consented for enrollment in a prospective cohort of OPAT patients, November 2015 to June 2018.16,19 If they expressed interest, they were mailed a consent form to sign and return. Once consent was received, semi-structured interviews were scheduled, frequently 4 weeks post discharge.

Patients eligible for contextual inquiries lived within a 45-minute drive of the 2 hospitals and were not already enrolled in the semi-structured interviews. These patients were recruited via telephone post discharge and provided written consent at the time of the contextual inquiry.

Data Collection and Analysis

The semi-structured interview guide and contextual inquiry tools (online supplementary Appendixes 1–2) were based on the Systems Engineering in Patient Safety (2.0) work system model.14,16 This model parallels the structure (work system)–process–outcome model of health care quality,20 whereby the work system includes the interacting components of tasks, tools and technologies, organization, physical environment, and the worker, all within an external environment.14 Three researchers (SCK, MK, AK) conducted semi-structured telephone interviews from November 2015 to June 2018. Interviews took approximately 30 to 45 minutes each and were audio recorded and transcribed.

Contextual inquiry sessions were performed from May 2017 to June 2018 and occurred with one or 2 investigators (SCK, MK).16 Investigators asked clarifying questions and took handwritten notes describing what was seen and heard from initiation to completion of the OPAT-related task. Photographs were obtained with additional written consent.

The initial coding template was based on the SEIPS 2.0 model.14 A preliminary coding template was developed after 2 researchers (SCK, RHC) each reviewed the same 3 randomly-selected transcripts and contextual inquiry notes. The 2 researchers coded the transcripts and notes independently prior to comparing codes. As subsequent transcripts and notes were reviewed, the coding template was revised and changes applied retroactively.

Next, directed content analysis was performed.21 The directed content analysis focused on a GDTA, which involves identifying (1) users’ major goals, (2) tasks and subtasks required to support major goals, and (3) perceptions of the barriers and strategies required to complete tasks.22 Coding was reviewed after every 10 interview transcripts or contextual inquiry notes, until thematic saturation occurred. Thematic saturation was reached for the findings presented.23 Analysis was facilitated with NVIVO software, version 11 (QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia).

Results

Forty patients were enrolled in the semi-structured interviews and 20 in the contextual inquiries (Table 1). Of the 40 semi-structured interview patients, 32 (80.0%) received services from the affiliated home infusion agency. Of the 20 contextual inquiry patients, half received services from the affiliated home infusion agency, most had a caregiver present during the first visit, and half completed 2 visits (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients on Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy Who Participated in Semi-structured Interviews or Contextual Inquiries.

| Characteristic or Demographic Variable | Semi-structured Interviews: Number (Percentage of n = 40) | Home Visit Contextual Inquiries: Number (Percentage of n = 20) |

|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 19 (47.5%) | 8 (40.0%) |

| Age (mean, SD) | 55.4 (12.5) | 52 (14.1) |

| Race/Ethnicity: white | 33 (82.5%) | 10 (50.0%) |

| Black/African American | 6 (15.0%) | 9 (45.0%) |

| Hispanic | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.0%) |

| Other | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Home infusion agency: affiliated | 32 (80.0%) | 10 (50.0%) |

| Presence of caregiver at time of first visit | N/A | 16 (80.0%) |

| Two visits completed | N/A | 10 (50.0%) |

The subsequent sections first describe major goals for patients, and tasks and subtasks required to achieve goals (Table 2). Then, associated hazards to achievement of the goals (Table 3) and strategies patients and caregivers use to address barriers (Table 4) are described.

Table 2.

Goals and Subgoals, With Associated Tasks Required to be Performed by Patients and Informal Caregivers, Required for OPAT Performance as Perceived by Patients.

| Goal | Subgoal | Others Involved With Patient and Caregiver | Task |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learning about OPAT (at transition from hospital to home) | Become informed about OPAT | Inpatient nurse Inpatient clinician |

Receive preliminary information in hospital Obtain understanding of venous catheter Obtain understanding of antimicrobial therapy |

| Initiate start of care visit | Home health nurse | Schedule start of care visit Arrival of home health nurse |

|

| Instruct in OPAT task performance with verbal information | Home health nurse | Receive instruction from nurse Choose who receives instruction |

|

| Task performed with supervision | Home health nurse | Show nurse how to do task | |

| Receive written instruction about OPAT task performance | Home health nurse | Receive written instructions or protocols Receive additional instruction added to printed protocols |

|

| Receive guidance on managing the venous catheter during activities of daily living | Home health nurse | Learn how to perform activities of daily living Learn how to care for line Learn how to keep dressing dry when bathing |

|

| Receive instruction about troubleshooting | Home health nurse | Learn signs of problems Learn when to troubleshoot Learn when to ask for help Learn when to seek emergency attention |

|

| Become accustomed to performing OPAT | Learn skills over time Learn what additional questions to ask Become accustomed to OPAT over time |

||

| Delivery of supplies and medications (ongoing while on OPAT) | Receives delivery | Courier or delivery person | Time delivery for when patient is home Assist delivery person with locating home |

| Administration of medication and maintenance of venous catheter (daily while on OPAT) | Schedule infusions | Develop a routine Remember to administer medication Take the medication on time Arrange administration around work, doctor visits, sleep, and nursing visits Arrange work and sleep around OPAT Adapt to schedule changes |

|

| Manage the duration of infusion | Know when infusion starts Know when infusion stops Set infusion rate |

||

| Clean the surface | Identify a clean workspace Wash off countertop or workspace |

||

| Set up supplies | Set up equipment | ||

| Clean hands | Wash hands with soap and water Use hand sanitizer |

||

| Keep the medication at an appropriate temperature | Keep the medication cool Keep the medication in the refrigerator Know when to remove the medication from the refrigerator |

||

| Access the venous catheter | Remove clothes | ||

| Administer the antimicrobial agent | Follow laid out steps Reach the venous catheter Set up new medication Put medication in case Flush out air Flush with saline Swab hub with alcohol Unclamp line Connect medication Inject medication Flush with saline and heparin |

||

| Stop the infusion | Procedure to stop infusion Clamp line Disconnect used antibiotic |

||

| Dispose of waste | Dispose of liquid waste and spills Identify where to dispose of used supplies |

||

| Administer medication in syringe or elastomeric device: specific task | Know when the infusion is complete | ||

| Prime the tubing when using mini-bags: specific task | Prime medication | ||

| Reconstitute antibiotic when using mini-bag: specific task | Mix antibiotic Shake antibiotic Identify needleless connector |

||

| Monitor infusion rate when using mini-bag: specific task | Set the medication drips to the appropriate rate Set the dial to the appropriate rate |

||

| Program pump for continuous or intermittent infusion medication: specific task | Program pump for continuous or continuous intermittent infusion | ||

| Monitor power level on pump for continuous or intermittent infusion: specific task | Verify battery is charged Know when battery needs to be charged Charge battery |

||

| Prevent harm while performing activities of daily living (daily while on OPAT) | Bathe | Keep dressing dry Cover dressing Acquire dressing cover Keep pump dry Keep line out of water |

|

| Dress | Need to get sleeve over antibiotics | ||

| Care for pets | Cover line Wash hands |

||

| Move around | Run errands or chores Arrange line while driving Arrange line while running errands Arrange medications while moving |

||

| Cook and clean | Keep line clean | ||

| Troubleshoot (daily while on OPAT) | Identify when things may be going wrong | Home health nurse | Look for signs of infection Look for signs of clot Identify problem Respond to beeping of pump |

| Contact health care team when complications arise | Home health nurse Home health staff Outpatient doctor Home infusion pharmacist |

Call nurse Call other home health staff Communicate with outpatient doctor Communicate with home health or home infusion team |

|

| Assess for complications remotely | Home health nurse Home health staff Outpatient doctor Home infusion pharmacist |

Describe complications over the telephone Describe complications over email or electronic health record messaging |

|

| Assess for complications in the home | Home health nurse Home health staff Outpatient doctor |

Arrange nurse visit Assist nurse while attempting troubleshooting Assist in decision to reassess complication |

|

| Assess for complications in clinic | Outpatient doctor | Attend clinic visit Assist doctor or nurse in understanding complication |

|

| Attempt own troubleshooting | Home health nurse | Attempt own troubleshooting Listen to nurse instructions for how to troubleshoot |

|

| Monitor status on treatment (ongoing and at end of treatment) | Change venous catheter dressing | Home health nurse | Determine who can change the dressing Determine where the dressing can be changed Troubleshoot problems with the dressing |

| Draw blood and send for laboratory testing | Home health nurse | Time blood draws with medication administration | |

| Monitor of overall condition | Staff in outpatient clinic Outpatient clinicians |

Travel to clinic appointment Time infusion around clinic appointment Attend clinic appointment |

|

| Remove venous catheter at end of therapy | Outpatient clinicians Home health staff Home health nurse Home infusion pharmacist |

Receive order to remove venous catheter Arrange for venous catheter removal |

Abbreviation: OPAT, outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy.

Table 3.

Hazards in Patient-Described OPAT Goals.

| Major Goal | Subgoal | Hazard |

|---|---|---|

| To be trained in catheter care and medication administration | Become informed about OPAT | Received misleading information in hospital |

| Initiate start of care visit | No nurse arrived | |

| Instruct in OPAT task performance with verbal information | Rushed instruction Different nurses give different instructions Errors in instruction Patient did not understand training |

|

| Task performed with supervision | Nurse did not watch patient perform OPAT task | |

| Receive written instruction about OPAT task performance | Instructions confusing Discharge information has differing information |

|

| Receive guidance on managing the venous catheter during activities of daily living | ||

| Receive instruction about troubleshooting | ||

| Become accustomed to performing OPAT | ||

| Delivery of supplies and medications | Receive delivery | Uncertainty: What to do if patient not at home Delivery person didn’t wait for person to answer door |

| Administration of medication and catheter maintenance | Schedule infusions | Uncertainty: how strict the scheduling must be Misinformed about scheduling Frequent dosing |

| Manage the duration of infusion | Rushes the infusion Takes longer than nurse says because of own decision making |

|

| Clean the surface | ||

| Set up supplies | ||

| Clean hands | Ambiguity: hand sanitizer versus soap Ambiguity: to wear gloves or not Bandaged hand can’t be clean Gloves hurt ability to feel to do task Only one glove worn Rubbed sanitizer on gloves, not hands |

|

| Access the catheter | ||

| Keep the medication at an appropriate temperature | Instructions as to when to remove from refrigerator are confusing Unclear if medication needs to be refrigerated or not |

|

| Administer the antimicrobial agent | Ambiguity: need for blood return | |

| Ambiguity: need to place on cap Can’t flush in steady stream because of poor strength or physical ailment Flushing hard to remember Different syringes and supplies delivered than what patient expected Physically difficult to attach medication Forgetting to unclamp line Wrong steps followed Forgets to flush out or creates more air bubbles Tubing too long Doesn’t swab hub long enough |

||

| Stop the infusion | Unclear: if heparin needed in continuous infusion medications Forgetting to clamp line |

|

| Dispose of waste | ||

| Administer medication in syringe or elastomeric device: specific task | Unclear if infusion complete Infusion stopped early |

|

| Prime the tubing when using mini-bags: specific task | Tubing touches floor | |

| Reconstitute antibiotic when using mini-bag: specific task | Complicated process Many steps required Needing more than 1 antimicrobial agent Reconstituted medication with wrong amount of sterile water |

|

| Monitor infusion rate when using mini-bag: specific task | Difficult to time flow rate Pole difficult to set up Unclear if empty |

|

| Program pump for continuous or intermittent infusion medication: specific task | Uncertainty: unclear when to start and stop pump Hard to do Nurse unable to help Not realizing pump is on Pump continues to beep |

|

| Monitor power level on pump for continuous or intermittent infusion: specific task | Power cord stopped working Running out of power |

|

| Prevent harm to the venous catheter while performing activities of daily living | Bathe | Dressing cover does not fit appropriately |

| Dress | ||

| Care for pets | Pets jump on patient Pet waste |

|

| Move around | Mobility device and line getting tangled or tugged | |

| Cook and clean | ||

| Troubleshoot | Identify when things may be going wrong | |

| Contact health care team when complications arise | Person on phone doesn’t understand the problem Difficulty understanding health care worker on phone Poor communication |

|

| Assess for complications remotely | Understanding issues with clamps Understanding issues with medications being screwed on too tightly |

|

| Assess for complications in the home | ||

| Assess for complications in clinic | Unclear who can troubleshoot in clinic Lack appropriate tools to address complication in clinic Complication not addressed |

|

| Attempt own troubleshooting | Patient panics | |

| Monitor status on treatment | Change venous catheter dressing | Patient uncomfortable with troubleshooting dressing changes Each nurse does it differently Unclear who can change dressing |

| Draw blood and send for laboratory testing | ||

| Monitor of overall condition | Primary care doctor unaware of situation Can’t get to appointment because of mobility Infectious diseases doctor unsure of situation |

|

| Remove catheter at end of therapy | Don’t know how to remove catheter Unsure who can order catheter removal |

Abbreviation: OPAT, outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy.

Table 4.

Strategies to Mitigate Hazards in Patient-Described OPAT-related Goals.

| Major Goal | Goal | Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| To be trained in catheter care and medication administration | Become informed about OPAT | Watched nurses in hospital Suggestion of formal class in OPAT |

| Initiate start of care visit | Taught at home care agency site | |

| Instruct in OPAT task performance with verbal information | Choose which instructions to follow | |

| Task performed with supervision | Teach-back | |

| Receive written instruction about OPAT task performance | Add own instructions to instruction manual Visual instructions more helpful than written instructions |

|

| Receive guidance on managing the catheter during activities of daily living | ||

| Receive instruction about troubleshooting | ||

| Become accustomed to performing OPAT | ||

| Delivery of supplies and medications | Receive delivery | |

| Administration of medication and maintenance of venous catheter | Schedule infusions | Developing a habit Use alarm on phone Schedule written out for patient |

| Manage the duration of infusion | Warm medicine to room temperature so that it infuses faster Crank up rate to fastest rate Walks to speed up infusion rate Have a faster family member do the infusions |

|

| Clean the surface | ||

| Set up supplies | Set up all equipment in advance Had supplies in a bag when traveling |

|

| Clean hands | Places emphasis on washing hands Wash hands frequently, thoroughly or twice Change gloves Turn off faucet with arm Uses both hand sanitizer and soap Use hand sanitizer as this was easier than walking back and forth to the sink Gloves instead of washing hands |

|

| Keep the medication at an appropriate temperature | Refrigerator Ice packs throughout the day Take out of refrigerator prior to starting Goes faster if take out night before Easier if doesn’t need refrigeration |

|

| Access the catheter | ||

| Administer the antimicrobial agent | Remember instructions for lines based on color Use SASH mnemonic or preparation mat as cognitive aid24 Add extra steps Swab until hear a squeak Push in bit by bit Know it’s unclamped if it clicks |

|

| Stop the infusion | ||

| Dispose of waste | Pad to collect drips | |

| Administer medication in syringe or elastomeric device: specific task | Marker on bag Check time Ball flat when done Squeeze at end |

|

| Prime the tubing when using mini-bags: specific task | ||

| Reconstitute antibiotic when using mini-bag: specific task | Like milking a cow | |

| Monitor infusion rate when using mini-bag: specific task | Use clamp to time drip Trial and error to time drip |

|

| Program pump for continuous or intermittent infusion medication: specific task | ||

| Monitor power level on pump for continuous or intermittent infusion: specific task | Charge overnight | |

| Prevent harm to the catheter while performing activities of daily living | Bathe | Rigged solutions |

| Dress | Thread line under clothes Use clothes to cover lines Use clothing to hold antibiotics |

|

| Care for pets | Cleaning and washing hands after handling pets | |

| Move around | Position self so no tug from line Stay in a particular position Eclipse ball in pocket |

|

| Cook and clean | Wear gloves | |

| Troubleshoot | Identify when things may be going wrong | |

| Contact health care team when complications arise | Take picture of central line to show nurse Text nurse |

|

| Assess for complications remotely | ||

| Assess for complications in the home | Explaining to patient it’s not their fault Make it easier for the patient Nurse looks up answer on internet search engine |

|

| Assess for complications in clinic | ||

| Attempt own troubleshooting | Nurse told patient to tape down dressing Patient and nurse troubleshoot Learn over time to troubleshoot Just wait for nurse Stop and think |

|

| Monitor status on treatment | Change catheter dressing | Patient checks dressing |

| Draw blood and send for laboratory testing | Timing lab draws Timing medications for lab draws |

|

| Monitor of overall condition | Told of importance of clinic visit | |

| Remove catheter at end of therapy |

Abbreviations: OPAT, outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy; SASH, saline-administer-saline-heparin.

Goal: Learning About OPAT

Patients had the goal of learning about OPAT, which encompassed the tasks of understanding its purpose and risks and how to physically perform OPAT. Associated tasks occurred in the hospital just prior to discharge, in the hospital-to-home transition, and in the first few days post discharge. Patients and caregivers had to receive training in VC care and medication administration tasks. One patient noted that she had not felt prepared to go home:

“That briefing of the [catheter] would have been nice to have done like a class. Show me a picture of how that thing’s installed in my arm, show me what happens if I were to pull it, why shouldn’t I pull [it], … what happens if I do? … You know, if I’d had that education before, it would have saved a lot of anxiety.” (47-year-old white female)

Hazards to learning about OPAT included receiving misleading information in the hospital, rushed instruction, different nurses giving different instructions, and confusing or inaccurate instruction manuals. For example, one patient and her husband took copious notes to understand an infusion pump instruction manual (Figure 1A):

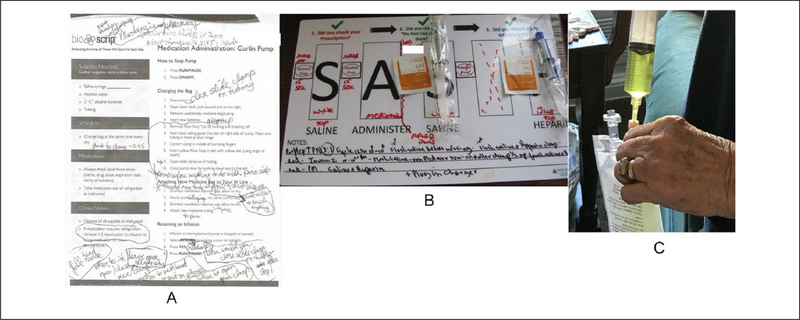

Figure 1.

Examples of patient and informal caregiver performance of tasks. (A) A patient and her informal caregiver took notes on an instruction sheet about how to set up their infusion pump, writing additional subtasks they were told also were necessary but were not written on the instruction sheet. (B) Patient receiving both total parenteral nutrition (TPN) and ertapenem uses the saline-administer-saline-heparin (SASH) system to start infusing his ertapenem. This laminated placemat allowed the patient and his home health nurse to take additional notes to tailor the task to his particular situation as well as reminders to scrub the venous catheter tip for 15 s with alcohol preparation pads prior to each subtask. (C) A patient’s informal caregiver injects a reconstituted antibiotic (ceftaroline) into a mini-bag of saline prior to initiation of infusion using a needle. The week prior, the patient informed the study team that this subtask had resulted in the caregiver sustaining a needlestick injury.

“[The instruction manual] … uses the term ‘needleless injection cap’ several times and [the patient and her husband] didn’t know what this was…. In addition … it says under ‘how to start an infusion’ that the ‘RESUME’ button should be pressed. The patient notes … [a] need to press ‘RESTART’ instead….” (66-year-old white female)

A strategy for the goal of learning about OPAT was “teach-back”—that is, having the patient “teach” the nurse what to do.

Goal: Receiving Supplies and Medications

An additional goal throughout the OPAT course included receiving supplies and medications on time. Hazards included uncertainty about where supply deliveries should be left if no one was home.

Goal: Administering the Medication and Maintaining the Catheter

The goal of administering the medication and maintaining the VC required many tasks, including timing administration, preparing medication, preparing infusion, initiating infusion, and stopping infusion, and device-specific tasks as well.

Timing Medication Administration

Patients and caregivers needed to administer the medication and maintain the VC. Hazards included uncertainty around the timing of the medication and needing to schedule infusions that dosed more than daily. For example, one patient struggled with whether to prioritize medication administration or attend clinic visits. Strategies included using a written schedule, a phone alarm, or developing a habit:

My husband wrote out a schedule for me because … in the best of times I have a hard time remembering what I’m supposed to do…. So he’d write ‘you take these this time and this this time’ … (63-year-old white female)

Preparing the Medication

To prepare the medication, patients or caregivers ensured it was at an appropriate temperature by removing it from the refrigerator. The longer the medication was at room temperature, the less effective it was, but if the medication was too cold, it would both take longer to infuse and cause discomfort. A hazard was not knowing when to remove the medication from the refrigerator.

Preparing for the Infusion

Patients needed to prepare for their infusions. First, they identified and cleaned their workspace and set up their supplies. Then, they needed to wash their hands. Hazards included uncertainty about how to clean their hands and whether to use gloves. Some used gloves after washing their hands, some used gloves instead of washing their hands, and some did not use gloves at all. A strategy was thoroughly washing hands, which some did with soap and water, some did with hand sanitizer, and some did with both:

The instruction sheet … puts more emphasis on using the antibacterial gel. I’m [wondering] why wouldn’t you just wash your hands? So I always wash my hands, and then I use the gel also … (58-year-old white female)

Initiating the Infusion

Patients next needed to start the infusion. They needed to follow specific steps, including holding the VC, removing air bubbles, flushing with saline and heparin, swabbing the hub with alcohol, setting up the new medication, unclamping the VC and medication, and injecting the medication or connecting the delivery device. Hazards included the tasks being physically difficult to do because of poor strength or dexterity, and forgetting steps such as unclamping the VC or medication (preventing the medication from infusing), flushing the VC (increasing the risk of a VC occlusion), or removing air bubbles (increasing the risk of air embolism). Strategies included visual reminders (separating VC lumen instructions based on color) and auditory feedback (ie, hearing a click to know the VC is unclamped). The saline-administer-saline-heparin (SASH) cognitive aid mat24 was considered a helpful strategy by many (Figure 1B).

Stopping the Infusion

Patients then needed to stop the infusion. Hazards included stopping the infusion too early. Strategies to make the infusion go faster included warming the antimicrobial agent, maximizing the rate on a manual dial, walking to increase the heart rate, or have the most efficient caregiver perform the infusions.

Device-Specific Tasks

Certain tasks were related to specific medication delivery devices, required for delivery of particular medications. A hazard for patients with syringes or elastomeric devices was knowing when the infusion was complete. Strategies to ensure complete medication infusion included checking the time, ensuring the elastomeric device was “flat” (ie, empty), and squeezing the device.

Mini-bags required many subtasks. Patients needed to prime the tubing daily, which was time consuming. They needed to reconstitute the antimicrobial agent (Figure 1C), a complicated process requiring many steps. Hazards included missing steps, incompletely adding the medication, or needle injuries. At times, this even led to injuries (Figure 1C):

The first time the mother (informal caregiver) [reconstituted the medication] they used a needle because they didn’t know about the needleless connector and the mother stuck herself … (44-year-old white female)

Strategies to know when the medication has been completely added to the mini-bag is to squeeze the mini-bag “like milking a cow” (45-year-old African American female, 58-year-old African American male). Strategies to monitor infusion rates included using a clamp, counting drips, setting a dial, or trial and error.

Some patients also used pumps. Hazards included running out of power and finding the pumps difficult to program (Figure 1C):

“If whoever manufactures these [pumps] were to get a design team to take a fresh look at it from the standpoint of ease of use, they might very well conclude that there are a number of ways in which the device could be simplified and made more user-friendly.” (65-year-old white male)

Strategies included monitoring the battery and calling for assistance with the pump.

Goal: Perform Activities of Daily Living

Patients also had the goal of preventing harm to the VC while performing activities of daily living, including bathing, dressing, performing chores, and ambulating. Hazards included getting the line tangled. Patients found some delivery devices were easier than others:

The [elastomeric device] ball is much easier than the [mini-] bag, because I can do that almost anywhere…. I could be in a movie theater. I could be in a restaurant…. The [mini-]bag is much more difficult because I have to have a stand and hook this up. (59-year-old white male)

Goal: Managing When Hazards Lead to Failures (Troubleshooting)

Patients also had the goal of managing when hazards led to failures, or “troubleshooting.”25 First, they had to recognize complications. Patients and caregivers then needed to contact home health staff about complications. The home health nurse or pharmacist had to remotely assess and determine which complications merited an in-person visit. As one patient experienced, nurses sometimes had to attempt several methods of troubleshooting:

[The nurse] drew back, she tried to flush, drew back, tried to flush. Then finally she said, huh, she went to her car and got a new end piece, put it on…. (65-year-old white male)

Finally, patients and caregivers sometimes had to perform their own troubleshooting. Hazards included becoming anxious and forgetting steps: “But I just kind of calmed down … and then that’s when I remembered, oh, I have to clamp it.” (47-year-old white female)

Goal: On-Therapy Monitoring

In addition, patients had the goal of on-therapy monitoring throughout OPAT. Tasks required included VC dressing changes, timing phlebotomy, monitoring their overall condition, and identifying how clinicians could remove the VC at the end of therapy.

Discussion

The research team performed a GDTA to describe patients’ perspectives on goals and associated tasks and subtasks required to successfully accomplish OPAT. The team showed that the processes required for OPAT performance are highly complex and have many hazards. Patients and their informal caregivers developed strategies to mitigate hazards. Although a few task analyses have shown how patients self-manage their medical conditions,5,9–12,26 task analysis has not been used to understand patient-performed tasks as complex and requiring as high a level of competency as in OPAT.

This study described how patients learn OPAT. Instructions sometimes contained errors, patients frequently struggled to understand instructions, and different nurses sometimes gave different instructions. The research team suggests that teaching be standardized, and visual cognitive aids and teach-back be standard parts of OPAT training. In addition, the team suggests that training be risk-informed, focusing on specific barriers individual patients face (eg, arthritis that might make tasks difficult to perform) and on mitigating the impact of safety hazards in the patient work system. Training methods could include contingency planning, simulations, or other methods.

Performing medication administration and VC care required many daily tasks. Instruction manuals were considered difficult to use. Others have suggested that designing medication instructions based on human factors engineering principles would increase the likelihood of medication adherence,27,28 and the same is likely true in OPAT. Meanwhile, many patients appreciated cognitive aids that used SASH24 to remember subtasks. Using cognitive aids and simplifying processes could improve OPAT performance.

Many hazards around medication administration and VC maintenance were related to ambiguity.29 Patients did not know how strictly they had to follow medication administration schedules, how to wash their hands, whether to wear gloves, at what temperature to administer medication, or how to ensure infusion completion. Clear standardized instructions could mitigate these hazards. Also, patients and caregivers frequently forgot certain subtasks, such as flushing both lumens of a double-lumen VC, swabbing sufficiently with alcohol, removing air bubbles, and clamping or unclamping VCs. Adding these steps to a visual cognitive aid such as SASH24 could help.

This study also described the goal of troubleshooting. This is in keeping with a recent study of United Kingdom health care workers’ home infusion pump-related incident reports, which found major concerns, including patients and caregivers not responding to alerts and struggling to detect and diagnose incidents.25 Assisting patients with performing troubleshooting is essential.

This is one of the first studies to take a patient-centered approach to understanding patient and caregiver performance of a complicated medical task at home. This also is one of the first studies to use a GDTA to understand patient tasks. This approach allowed a fuller understanding of a highly complex series of tasks. The qualitative data set allowed the research team to gather a deep understanding of the complexity of the tasks required for successful OPAT. In addition, the approach was novel as it performed a GDTA over time and so assessed goals longitudinally instead of over one limited period.

This study had some limitations. Patients were discharged from 2 academic medical centers in one American city, and specific tasks required for OPAT may differ in different settings. However, patients from multiple home care agencies were enrolled. Because the goal was to learn about the patient perspective, health care workers were not interviewed. This was a qualitative study meant to be hypothesis-generating; the research team did not know a priori which hazards may have been associated with poorer outcomes. In addition, it is possible that some patients may have received OPAT in the past prior to the study’s start or at a hospital not involved in the study, or received other home-based therapies in the past. Therefore, some patients or caregivers may have had prior experiences that allowed them to better perform tasks, potentially biasing the results. However, this also led to a broader breadth of experiences in the study. In addition, there was variation between the timing of the contextual inquiry (with the first visits occurring 3–14 days post discharge) and semi-structured interviews (typically 4 weeks post discharge and near the end of treatment). It is possible that patient and caregiver task performance could have changed during these time periods, introducing bias. However, the research team was able to learn about the experiences patients had had in OPAT to date with these methods.

OPAT requires patients and informal caregivers to conquer many tasks and subtasks to meet 6 overarching goals (ie, learning about OPAT, receiving supplies and medications in a timely manner, administering the medication and maintaining the VC, performing activities of daily living, troubleshooting, on-therapy monitoring). Health care workers who care for OPAT patients should support patients and caregivers in achieving these goals through minimizing hazards, standardized teaching with teach-back, use of cognitive aids, standardizing expectations, and improving instruction manuals. Although further research is needed to understand what specific strategies are required to improve OPAT, organizations should use these results to inform their education methods and content. Addressing patient OPAT goals is essential to ensuring that patients have positive, safe OPAT experiences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of Mayo Levering, BS, for her assistance in enrolling patients in the study and the patients, caregivers, and home health staff who have graciously given us their time and insights. We acknowledge the support and advice of Michael Kohut, PhD, for his assistance in performing semi-structured interviews and contextual inquiries.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1K08HS025782-01 to SCK), the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational research (KL2TR001077 to SCK), the Sherrilyn and Ken Fisher Center for Environmental Infectious Diseases Discovery Award (SCK), and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America Epi-Program (SCK).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Norris AH, Shrestha NK, Allison GM, et al. 2018 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guideline for the management of outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:e1–e35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keller SC, Gurses AP, Leff B, Hughes A, Hohl D, Arbaje AI. Older adults and management of medical devices in the home: five requirements for successful use. Popul Health Manag. 2017;20:278–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abts N, Hernandez A, Caplan S, Hettinger AZ, Larsen E, Lewis VR. When human factors and design unite: using visual language and usability testing to improve instructions for a home-use medication infusion pump. Proc Int Symp Hum Factors Ergon Healthc. 2014;3(1):254–260. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henriksen K, Joseph A, Zayas-Caban T. The human factors of home health care: a conceptual model for examining safety and quality concerns. J Patient Saf. 2009;5:229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werner NE, Malkana S, Gurses AP, Leff B, Arbaje AI. Toward a process-level view of distributed healthcare tasks: medication management as a case study. Appl Ergon. 2017;65:255–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wooldridge A, Carayon P, Hoonakker P, et al. Complexity of the pediatric trauma care process: implications for multilevel awareness [published online, August 31, 2018]. Cogn Technol Work. 10.1007/s10111-10018-10520-10110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurses AP, Xiao Y, Hu P. User-designed information tools to support communication and care coordination in a trauma hospital. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:667–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pennathur PR, Thompson D, Abernathy JH III, et al. Technologies in the wild (TiW): human factors implications for patient safety in the cardiovascular operating room. Ergonomics. 2013;56:205–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lippa KD, Klein HA, Shalin VL. Everyday expertise: cognitive demands in diabetes self-management. Hum Factors. 2008;50:112–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holden RJ, Schubert CC, Mickelson RS. The patient work system: an analysis of self-care performance barriers among elderly heart failure patients and their informal caregivers. Appl Ergon. 2015;47:133–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mickelson RS, Willis M, Holden RJ. Medication-related cognitive artifacts used by older adults with heart failure. Health Policy Technol. 2015;4:387–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arbaje AI, Hughes A, Werner N, et al. Information management goals and process failures during home visits for middle-aged and older adults receiving skilled home healthcare services after hospital discharge: a multisite, qualitative study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28:111–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Omondi GB, Serem G, Abuya N, et al. Neonatal nasogastric tube feeding in a low-resource African setting—using ergonomics methods to explore quality and safety issues in task sharing. BMC Nurs. 2018;17:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holden RJ, Carayon P, Gurses AP, et al. SEIPS 2.0: a human factors framework for studying and improving the work of healthcare professionals and patients. Ergonomics. 2013;56:1669–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Endsley M, Hoffman RR. The Sacagawea principle. IEEE Intell Syst. 2002;17:80–85. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keller SC, Cosgrove SE, Kohut M, et al. Hazards from physical attributes of the home environment among patients on outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT). Am J Infect Control. 2019;47:425–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurses AP, Kim G, Martinez EA, et al. Identifying and categorising patient safety hazards in cardiovascular operating rooms using an interdisciplinary approach: a multisite study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21:810–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurses AP, Martinez EA, Bauer L, et al. Using human factors engineering to improve patient safety in the cardiovascular operating room. Work. 2012;41(suppl 1):1801–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keller SC, Williams D, Gavgani M, et al. Environmental exposures and the risk of central venous catheter complications and readmissions in home infusion therapy patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38:68–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donabedian A The quality of care: how can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260:1743–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaber DB, Segall N, Green RS, Entzian K, Junginger S. Using multiple cognitive task analysis methods for supervisory control interface design in high-throughput biological screening processes. Cogn Technol Work. 2006;8:237–252. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ando H, Cousins R, Young C. Achieving saturation in thematic analysis: development and refinement of a codebook. Compr Psychol. 2014;3(4):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johns Hopkins Home Care Group. Saline Administer Saline Heparin (SASH) Placemat. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/homecare/services/infusion/patient_resources.html. Accessed May 22, 2019.

- 25.Lyons I, Blandford A. Safer healthcare at home: detecting, correcting and learning from incidents involving infusion devices. Appl Ergon. 2018;67:104–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein HA, Lippa KD. Type 2 diabetes self-management: controlling a dynamic system. J Cogn Eng Decis Mak. 2008;2:48–62. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein HA, Isaacson JJ. Making medication instructions usable. Ergon Des. 2003;11(2):7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isaacson JJ, Klein HA, Muldoon RV. Prescription medication information: improving usability through human factors design. Proc Hum Factors Ergon Soc Annu Meet. 1999;43:873–877. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gurses AP, Seidl KL, Vaidya V, et al. Systems ambiguity and guideline compliance: a qualitative study of how intensive care units follow evidence-based guidelines to reduce healthcare-associated infections. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:351–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.