Abstract

Glisson’s capsule is the connective tissue present in the portal triad as well as beneath the liver surface. Little is known about how Glisson’s capsule changes its structure in capsular fibrosis, which is characterized by fibrogenesis beneath the liver surface. In this study we found that the human liver surface exhibits multilayered capsular fibroblasts and that the bile duct is present beneath the mesothelium, whereas capsular fibroblasts are scarce and no bile ducts are present beneath the mouse liver surface. Patients with cirrhosis caused by alcohol abuse or HCV infection show development of massive capsular fibrosis. To examine the effect of alcohol on capsular fibrosis in mice, we first injected chlorhexidine gluconate (CG) intraperitoneally and then fed alcohol for 1 month. The CG injection induces capsular fibrosis consisting of myofibroblasts beneath the mesothelium. One month after CG injection, the fibrotic area returns to the normal structure. In contrast, additional alcohol feeding sustains the presence of myofibroblasts in capsular fibrosis. Cell lineage tracing revealed that mesothelial cells give rise to myofibroblasts in capsular fibrosis, but these myofibroblasts disappear 1 month after recovery with or without alcohol feeding. Capsular fibroblasts isolated from the mouse liver spontaneously differentiated into myofibroblasts and their differentiation was induced by TGF-β1 or acetaldehyde in culture. In alcohol fed mice, infiltrating CD11b+Ly-6CLow/- monocytes had reduced mRNA expression of Mmp13 and Mmp9 and increased expression of Timp1, Tgfb1, and Il10 during resolution of capsular fibrosis. In conclusion, the present study revealed that the structure of Glisson’s capsule is different between human and mouse livers and that alcohol impairs the resolution of capsular fibrosis by changing the phenotype of Ly-6CLow/- monocytes.

Keywords: alcohol, capsular fibroblasts, Glisson’s capsule, mesothelial cells, myofibroblasts

INTRODUCTION

Long-term alcohol consumption causes alcoholic steatosis and steatohepatitis, which are characterized by accumulation of lipids in hepatocytes and inflammation.(1,2) If liver injury persists, about 30% of alcohol abusers develop fibrosis and finally cirrhosis. Oxidative alcohol metabolism in hepatocytes generates harmful compounds, such as acetaldehyde and reactive oxygen species, and causes damage to hepatocytes.(3) Hepatic stellate cells reside in the space of Disse, express desmin (DES), and store vitamin A lipids.(4) Signals from injured hepatocytes induce the activation of hepatic stellate cells and result in their morphological change to myofibroblasts expressing α-smooth muscle actin (ACTA2). Myofibroblasts synthesize proinflammatory cytokines and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins and participate in the progression to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. Currently, no treatment cures patients with cirrhosis other than liver transplantation.(5)

Although hepatic stellate cells are recognized as a major source of myofibroblasts in liver fibrosis, portal fibroblasts in the portal triad are known to participate in biliary fibrosis.(6–8) Glisson’s capsule is the connective tissue that sheaths the portal vein, hepatic artery, and bile duct in the portal triad.(9) In addition to the portal area, the connective tissue that develops beneath the liver surface is also named Glisson’s capsule.(9) Liver surface Glisson’s capsule is composed of a single layer of mesothelial cells and a single stratum of capsular fibroblasts in rodent livers.(10–12) From an anatomical point of view, portal and capsular fibroblasts are associated with biliary epithelial cells and mesothelial cells, respectively, and are continuous as Glisson’s capsule from the liver hilus. However, little is known about the contribution of capsular fibroblasts to capsular fibrosis, which is characterized by fibrogenesis beneath the liver surface, due to the insufficient availability of markers and isolation methods.

Mesothelial cells form the mesothelium on the liver surface and exhibit an intermediate phenotype between epithelial cells and mesenchymal cells, and express type I collagen (COLI), vimentin (VIM), and cytokeratin.(13) Liver mesothelial cells uniquely express glycoprotein M6A (GPM6A), podoplanin (PDPN), and Wilms tumor 1 (WT1).(13) During liver development, mesothelial cells migrate inward from the liver surface and give rise to both hepatic stellate cells and portal fibroblasts.(14) Upon liver injury, mesothelial cells give rise to ACTA2+ myofibroblasts near the liver surface in CCl4-induced fibrosis.(13,15)

In the present study, we examined how the liver surface Glisson’s capsule changes its structure upon alcohol-induced injury and how alcohol impairs the resolution of capsular fibrosis.

Materials and Methods

Mouse models

Tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich) was injected intraperitoneally to the Wt1CreERT2;Rosa26mTmGflox (R26TGfl/fl) and R26TGfl/fl mice at 100 μg/g body weight twice in a 3-day interval.(13) To induce capsular fibrosis, we injected 0.1% chlorhexidine gluconate (CG) in 15% ethanol/PBS to mice at 1.5 ml/100 g body weight into the peritoneum every other day for a total of 10 times.(16) For recovery from CG-induced capsular fibrosis, mice were kept for 1 month without treatment. To test the effect of alcohol on CG-induced capsular fibrosis, we injected the CG solution 10 times to mice as above. Mice were acclimatized to a liquid diet containing high cholesterol fat diet (HCFD, Dyets #710142) for 5 days. Then, mice were fed with a liquid diet containing ethanol and HCFD (#710362) for 4 weeks. Ethanol content was gradually increased from 1% on day 1 to 4.35% on day 12.(17) To evaluate the resolution of capsular fibrosis, mice were subjected to the CG treatment and alcohol feeding as above. Then, mice were kept for 1 month without alcohol feeding.

Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS)

After digestion of the whole liver with pronase and collagenase, cells were centrifuged and incubated with CD16/32 antibodies (16–0161, eBioscience) to block Fc receptors. Then, cells were incubated with antibodies against CD45-APC-Cy7 (557659, BD Pharmingen), Ly-6G-PE (551461), CD11b-APC (553312), Ly-6C-FITC (553104), and/or F4/80-PerCP/Cy5.5 (123128, BioLegend) at 50-fold dilution for 30 min on ice. After washing, the cells were incubated with DAPI for detection of dead cells. We compensated each fluorescence signal using cells with or without staining in each fluorochrome with FACS Aria I (BD Bioscience) in the USC Flow Cytometry Core.

Other method details are provided in the Supporting Information.

Results

Structural difference of Glisson’s capsule in mouse and human livers

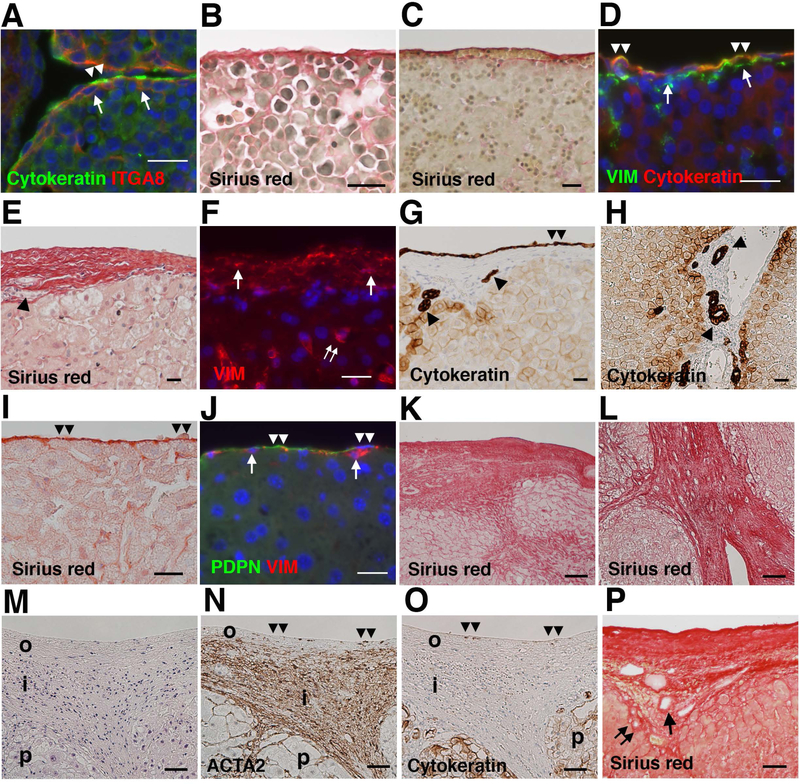

We previously reported that the surface of embryonic day (E) 12.5 mouse livers is covered by a single layer of cytokeratin+ mesothelial cells and that there are sub-mesothelial cells expressing ITGA8 (Fig. 1A).(14,18) We referred to these sub-mesothelial cells as capsular fibroblasts thereafter. Sirius red staining of E13.5 mouse livers revealed the presence of a thin collagen layer in Glisson’s capsule (Fig. 1B). In fetal human livers, Glisson’s capsule shows a thin collagen layer associated with erythrocytes at 15.2 weeks of gestation (Fig. 1C). Glisson’s capsule is covered by a single layer of cytokeratin+ mesothelial cells (Fig. 1D). Both mesothelial cells and underlying capsular fibroblasts express VIM (Fig. 1D).

FIG. 1.

Structural difference of Glisson’s capsule in human and mouse livers. (A) Immunofluorescence staining of the E12.5 mouse liver. Arrows and double arrowheads indicate ITGA8+ capsular fibroblasts and cytokeratin+ mesothelial cells, respectively. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. (B) Sirius red staining of the E13.5 mouse liver. (C) Sirius red staining of the human fetal liver. (D) Immunofluorescence staining of the human fetal liver. Arrows and double arrowheads indicate VIM+ capsular fibroblasts and cytokeratin+VIM+ mesothelial cells, respectively. (E) Sirius red staining of the normal human liver. An arrowhead indicates the bile duct in the capsule. (F) Immunofluorescence staining of the human liver. Arrows and double arrows indicate VIM+ capsular fibroblasts and hepatic stellate cells, respectively. (G,H) Immunohistochemistry of the normal human liver. Double arrowheads indicate cytokeratin+ mesothelial cells. Arrowheads indicate bile ducts in Glisson’s capsule beneath the liver surface in G or in the portal triad in H. (I) Sirius red staining of the adult mouse liver. Double arrowheads indicate the mesothelium. (J) Immunofluorescence staining of the normal mouse liver. Arrows indicate VIM+ capsular fibroblasts beneath PDPN+ mesothelial cells. (K-O) Human specimens with alcoholic cirrhosis were analyzed by Sirius red staining (K,L), H&E staining (M), and immunohistochemistry for ACTA2 (N) and cytokeratin (O). Double arrowheads indicate the liver surface. i; inner layer, o; outer layer, p; parenchyma. (P) Sirius red staining of cirrhotic liver caused by HCV infection. Arrow and double arrows indicate the portal vein and bile duct, respectively. Bars, 20 μm (A-J) and 50 μm (K-P).

In the normal adult human liver, Glisson’s capsule consists of multi-layered capsular fibroblasts in the collagen matrix (Fig. 1E). The thickness of the capsule is around 30–50 μm and capsular fibroblasts are positive for VIM (Fig. 1F). The capsule is covered by a single layer of cytokeratin+ mesothelial cells (Fig. 1G). Cytokeratin-positive bile ducts are also observed in the connective tissue of Glisson’s capsule beneath the liver surface as well as in the portal triad (Fig. 1G,H). In contrast to human livers, adult mouse livers exhibit a thin collagen layer in Glisson’s capsule (Fig. 1I). VIM+ capsular fibroblasts are scarce beneath PDPN+ mesothelial cells (Fig. 1J). Differing from human livers, no bile ducts are observed in Glisson’s capsule beneath the mouse liver surface. Our data disclosed the structural difference of the liver surface Glisson’s capsule between humans and mice.

Development of capsular fibrosis in patients with cirrhosis

Next, we examined pathological changes of Glisson’s capsule in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Sirius red staining showed a massive deposition of collagen beneath the liver surface and the thickness of the capsule exceeded 500 μm (Fig. 1K). The fibrotic septa that developed beneath the liver surface were continuous with those developed from the central vein (Fig. 1K,L). H&E staining and immunohistochemistry showed that ACTA2+ myofibroblasts are sparse in the outer layer of the capsule (Fig.1M,N). In the inner layer, between the outer layer and parenchyma, ACTA2+ myofibroblasts are rich in the fibrotic area. Expression of cytokeratin was not observed on the liver surface (Fig. 1O), suggesting disappearance of the mesothelium from the liver surface. Thickening of Glisson’s capsule is also observed in cirrhotic liver caused by HCV infection (Fig. 1P). Portal veins and bile ducts are observed in the capsular fibrotic area of Glisson’s capsule. These results indicate that capsular fibrosis develops in cirrhosis caused by different etiology.

No induction of capsular fibrosis by alcohol feeding in mice

Given that patients with alcoholic cirrhosis develop massive capsular fibrosis in Glisson’s capsule, we tested whether alcohol feeding induces capsular fibrosis in mice. To trace the fate of mesothelial cells in capsular fibrosis, we injected tamoxifen to Wt1CreERT2;R26TGfl/fl mice and labeled mesothelial cells as GFP+ cells on the liver surface (Fig. 2A).(13) Injection of tamoxifen induced GFP expression in GPM6A+ mesothelial cells on the liver surface in Wt1CreERT2;R26TGfl/fl mice, but not in control Wt1+/+;R26TGfl/fl mice (Fig. 2B). We fed mice HCFD for 2 weeks and then ethanol and high-fat liquid diet by intragastric catheter for 5 weeks (Fig. 2A).(17) Compared to the control group, ethanol-fed mice showed increased BAL, plasma ALT, and liver/body weight ratio (Fig. 2C). RT-QPCR showed increased expression of Col1a1 mRNA in the alcohol-fed liver compared with the control (Fig. 2D). Although expression of Acta2 and Timp1 mRNAs tended to increase by alcohol feeding, the differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 2D). Sirius red staining showed scarce deposition of collagen fibers under the liver surface in alcohol-fed mice (Fig. 2E). Immunofluorescence staining showed that GFP+ mesothelial cells migrate inward and differentiate into GFP+DES+ hepatic stellate cell-like cells near the liver surface in alcohol-fed mice (Fig. 2F). They were negative for ACTA2 (Fig 2F) and GFAP (data not shown). Myofibroblasts near the central vein were positive for ACTA2 (Fig 2F). Furthermore, extension of alcohol feeding to 8 weeks did not induce capsular fibrosis (data not shown), indicating that liver injury caused by alcohol feeding does not induce capsular fibrosis in mice.

FIG. 2.

No induction of capsular fibrosis by alcohol intake in mice. (A) Experimental design. After labeling mesothelial cells as GFP+ cells by tamoxifen injection in Wt1CreERT2/+;R26TGfl/fl mice, we fed mice HCFD for 2 weeks, and then additionally fed ethanol and high-fat liquid diet (Alc+HFD) by intragastric (IG) catheter for 5 weeks (n=4). Control mice were fed an isocaloric dextrose solution instead of ethanol (n=3). (B) Immunofluorescence staining shows that tamoxifen treatment induces GFP in GPM6A+ mesothelial cells (double arrowheads) in Wt1CreERT2/+;R26TGfl/fl, but not in Wt1+/+;R26TGfl/fl mice. (C) BAL, plasma ALT, and liver/body weight of the control (Ctr) and alcohol-treated (Alc) mice. *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01. (D) RT-QPCR of the livers from the Ctr and Alc mice. (E) Sirius red staining of the Ctr and Alc livers. (F) Immunofluorescence staining of the livers with GFP (green) and DES or ACTA2 (red). Arrows indicate mesothelial cell-derived hepatic stellate cell-like cells expressing DES, but not ACTA2. Mesothelial cells are indicated by double arrowheads. Double arrows indicate ACTA2+ myofibroblasts inside the injured liver. Bars; 10 μm (B,F) and 50 μm (E).

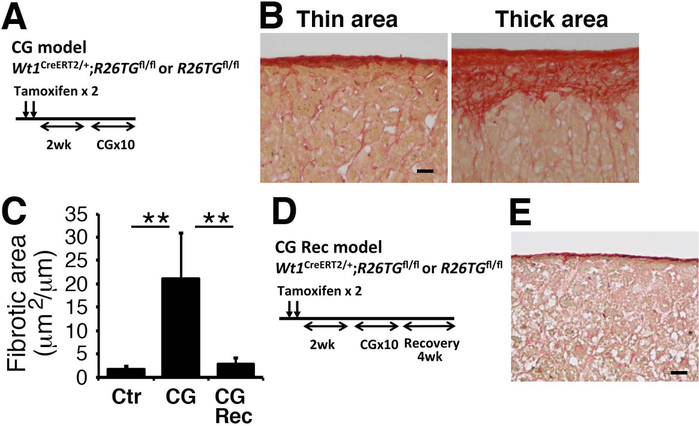

Induction of capsular fibrosis by CG in mice

Repeated injections of CG into the peritoneal cavity induce capsular fibrosis on the mouse liver surface.(16) After labeling mesothelial cells as GFP+ cells, we injected CG into the peritoneal cavity 10 times (Fig. 3A). Sirius red staining revealed that capsular fibrosis does not develop uniformly on the liver surface in the CG model (Fig. 3B). Compared to the normal mouse liver, the ratio of capsular fibrosis area per the liver surface length was significantly increased from 1.7 to 21.2 μm2/μm (Fig. 3C). The CG treatment did not induce fibrosis around the portal vein or central vein inside the liver, indicating specific induction of capsular fibrosis by CG. After CG injections, we kept the mice without further CG treatment for 1 month (Fig. 3D, CG-Rec). Sirius red staining revealed that the capsular fibrotic area was significantly decreased to 2.8 μm2/μm compared to the CG model (Fig. 3C,E), indicating that capsular fibrosis is resolved upon termination of the CG-induced injury within 1 month.

FIG. 3.

Capsular fibrosis induced by CG injections and its resolution. (A) Experimental design. After injection of tamoxifen to Wt1CreERT2/+;R26TGfl/fl (n=3) and R26TGfl/fl (n=3) mice, CG was intraperitoneally injected 10 times to mice (CG model). (B) Sirius red staining of the mouse livers. The CG model induces capsular fibrosis in mice. Note that development of capsular fibrosis is not uniformly observed on the liver surface. (C) Quantification of the fibrotic areas stained with Sirius red on the liver surface. ** P< 0.01. (D) Experimental design. After injection of tamoxifen to Wt1CreERT2/+;R26TGfl/fl (n=4) and R26TGfl/fl (n=2) mice, CG was injected to mice. To induce resolution of capsular fibrosis, mice were kept 1 month without CG treatment (CG-Rec). (E) Sirius red staining of the liver surface 1 month after CG injection. Bar, 20 μm.

Accumulation of myofibroblasts and inflammatory cells in capsular fibrosis

Given that capsular fibrosis induced by CG does not develop uniformly, we analyzed how different cell types appear in the thin and thick fibrotic areas with immunofluorescence staining. In the normal mouse liver, Glisson’s capsule is negative for ACTA2 and DES and expression of ECM proteins is weak (Fig. 4A). In the thin fibrotic area in the CG model, myofibroblasts expressing ACTA2 and DES emerge beneath PDPN+ mesothelial cells and express COLI and COLIV (Fig. 4B). Infiltration of CD45+ cells is observed in the fibrotic area (Fig. 4B). In the thick fibrotic area, capsular fibrosis consists of the outer and inner layers above the parenchyma (Fig. 4C). The outer layer shows a strong deposition of COLI and COLIV, where ACTA2+ myofibroblasts express PDPN and align along the liver surface. In the inner layer, DES+ fibroblasts are largely negative for ACTA2 and PDPN and the expression of COLI and COLIV is weak (Fig. 4C). Strong DCN expression and infiltration of CD45+ cells are observed in both layers. Myofibroblasts are not observed in the parenchyma. In the CG-Rec model, the regenerated liver surface shows faint expression of ACTA2, DES, COLI, and DCN (Fig. 4D), suggesting the resolution of capsular fibrosis 1 month after CG injections.

FIG. 4.

Development of capsular fibrosis and accumulation of myofibroblasts in capsular fibrosis. Liver tissues were examined by immunofluorescence staining. (A) The control normal liver (Ctr) shows no expression of ACTA2 and DES and weak expression of COLI, COLIV, and DCN on the liver surface. Mesothelial cells express PDPN. (B,C) CG injection induces capsular fibrosis. The thin fibrotic areas in B show the presence of ACTA2+DES+ myofibroblasts surrounding COLI and COLIV. Infiltration of CD45+ cells is observed in the fibrotic area. The thick fibrotic area in C is composed of 2 layers. The outer layer (o) contains myofibroblasts surrounded by COLI, COLIV, and DCN. DES+ fibroblastic cells in the inner layer (i) are largely negative for ACTA2, COLI, and COLIV. p, parenchyma. (D) One month after CG injections (CG-Rec), the liver surface shows a similar phenotype as the normal liver (Ctr). Bar, 20 μm.

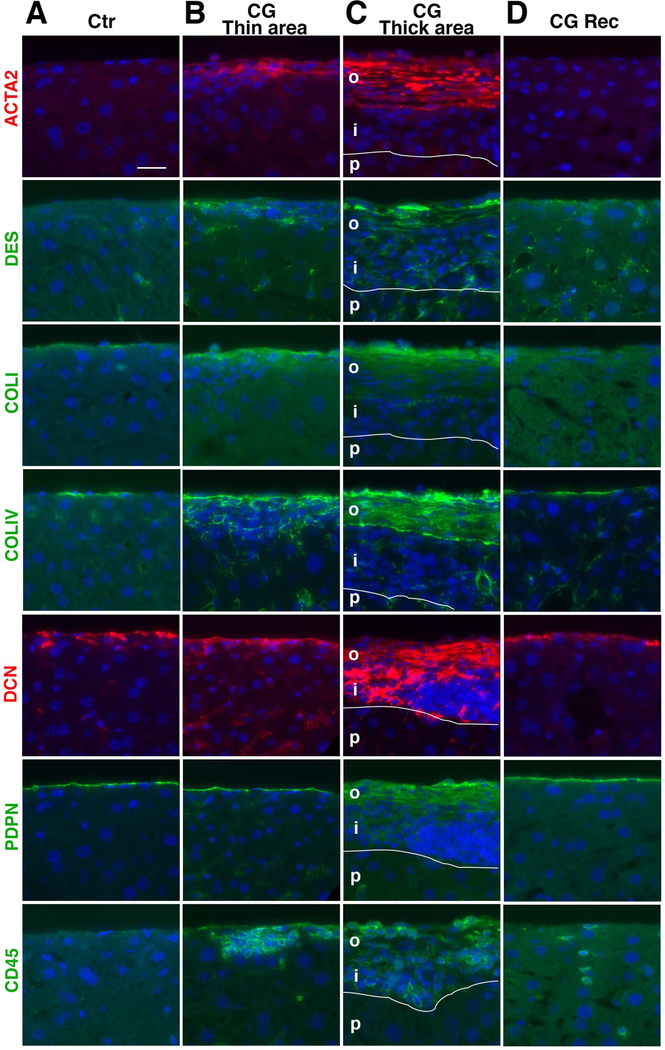

Alcohol intake impairs resolution of CG-induced capsular fibrosis

Next, combining preconditioning with CG treatment as a first hit and alcohol feeding as a second hit, we attempted to induce alcohol-induced capsular fibrosis in mice as a humanized model. After CG injections, we fed mice a liquid diet containing alcohol and HCFD for 4 weeks (Fig. 5A, CG-Alc). Sirius red staining showed that in addition to thin fibrotic areas, thick capsular fibrosis areas occasionally remain on the liver surface (Fig. 5B). Compared with the CG model (Fig 5C), the ratio of the capsular fibrosis area was reduced from 21.2 to 8.1 μm2/μm in the CG-Alc model (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, the fibrotic area in the CG-Alc model was significantly higher than that of the CG-Rec model (Fig. 3C and 5C), suggesting that the alcohol feeding impairs the resolution of capsular fibrosis induced by CG.

FIG. 5.

Alcohol feeding impairs resolution of CG-induced capsular fibrosis in mice. (A) After injection of tamoxifen and CG to Wt1CreERT2/+;R26TGfl/fl (n=6) and R26TGfl/fl (n=1) mice, mice were fed alcohol and HCFD for 1 month (CG-Alc). (B) Sirius red staining. In the CG-Alc model, thick capsular areas occasionally remain on the liver surface. (C) Quantification of the fibrotic areas stained with Sirius red on the liver surface. A red line represents the fibrotic area in the liver 1 month after CG injections shown in Fig. 3C. Compared to the CG-Rec model (red line), the CG-Alc model significantly impairs resolution of capsular fibrosis. Feeding of normal chow for 1 month (CG-Alc-Rec) does not reduce the capsular fibrosis areas induced by CG injections followed by alcohol feeding. * P< 0.05 against the CG-Alc model (red line). (D) After injection of tamoxifen and CG to Wt1CreERT2/+;R26TGfl/fl (n=6) and R26TGfl/fl (n=2) mice, mice were fed alcohol and HCFD for 1 month followed by regular chow feeding for 1 month (CG-Alc-Rec). (E) Oil red O staining of the livers. Alcoholic steatosis is ameliorated 1 month after withdrawal of alcohol. (F) Sirius red staining of the liver in the CG-Alc-Rec model. Bar, 20 μm.

We further examined whether capsular fibrosis induced by CG-Alc reverts to a normal liver surface by feeding normal chow for 1 month (Fig. 5D, CG-Alc-Rec). Oil red O staining confirmed development of alcoholic steatosis by alcohol feeding and disappearance of lipids in the liver 1 month after recovery (Fig. 5E). Yet, capsular fibrosis areas largely remained on the liver surface 1 month after alcohol feeding (Fig. 5C,F).

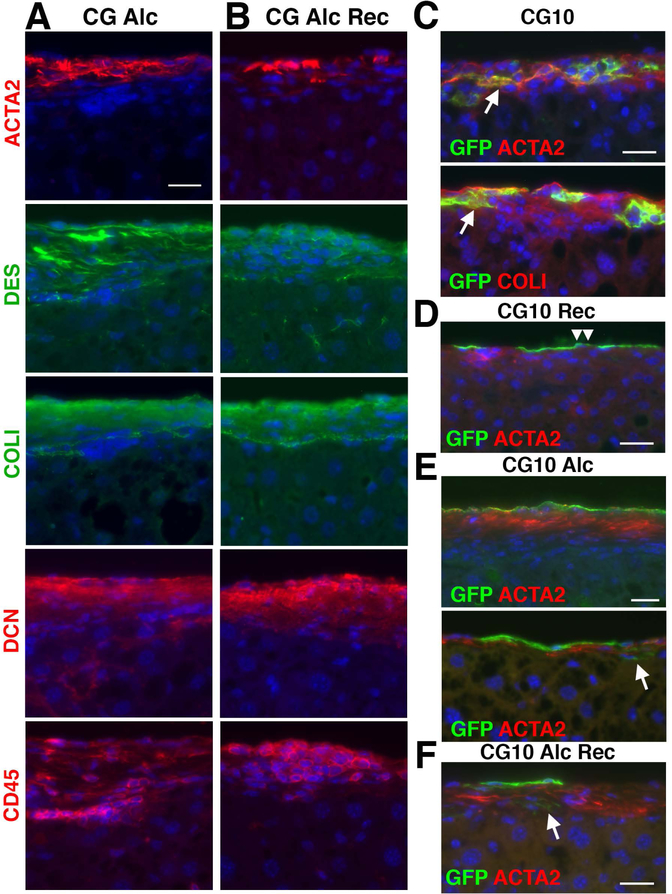

Alcohol intake sustains the presence of myofibroblasts in capsular fibrosis

Immunofluorescence staining showed the presence of ACTA2+DES+ myofibroblasts in the CG-Alc model (Fig. 6A). The capsular areas remain positive for COLI and DCN. Infiltration of CD45+ cells is observed in the fibrotic area. One month after withdrawal of alcohol, the fibrotic areas still contain ACTA2+DES+ myofibroblasts surrounded by COLI and DCN positive areas (Fig. 6B). CD45+ cells remains in the fibrotic area. These results indicate that alcohol intake sustains the presence of myofibroblasts in CG-induced capsular fibrosis.

FIG. 6.

Alcohol impairs resolution of capsular fibrosis induced by CG injections. Liver tissues were examined by immunofluorescence staining. (A) In the CG-Alc model, ACTA2+DES+ myofibroblasts remain in fibrotic areas positive for COLI and DCN on the liver surface. (B) In the CG-Alc-Rec model, myofibroblasts and CD45+ cells remain in the capsular fibrosis areas similar to A. (C-F) Lineage tracing of mesothelial cells in capsular fibrosis and in its resolution. (C) Arrows indicate mesothelial cell-derived myofibroblasts in CG-induced capsular fibrosis. (D) In the CG-Rec model, GFP expression is only observed in mesothelial cells (double arrowheads). (E) In the CG-Alc model, ACTA2+ myofibroblasts are largely negative for GFP. An arrow indicates rare GFP+ACTA2− fibroblasts at the interface between the fibrotic area and parenchyma. (F) In the CG-Alc-Rec model, ACTA2+ myofibroblasts are largely negative for GFP. An arrow indicates rare GFP+ACTA2− fibroblasts. Bars, 20 μm.

The origin of myofibroblasts in capsular fibrosis

We traced the fate of mesothelial cells in CG-induced capsular fibrosis and its resolution in Wt1CreERT2;R26TGfl/fl mice. In the CG model, we observed GFP+ACTA2+ myofibroblasts in the capsular fibrosis area that is positive for COLI (Fig. 6C), as we previously reported.(16) One month after recovery from CG-induced capsular fibrosis, mesothelial cells remained positive for GFP, but no GFP+ cells were observed beneath mesothelial cells (Fig. 6D). In the CG-Alc model, ACTA2+ myofibroblasts are largely negative for GFP (Fig. 6E). Few GFP+ACTA2− fibroblasts are present between the fibrotic area and parenchyma. One month after recovery from the CG-Alc model, the remaining ACTA2+ myofibroblasts are largely negative for GFP (Fig. 6F), suggesting that mesothelial cell-derived myofibroblasts disappear in alcohol-induced liver injury and alcohol intake maintains the phenotype of myofibroblasts derived from other cellular sources in capsular fibrosis.

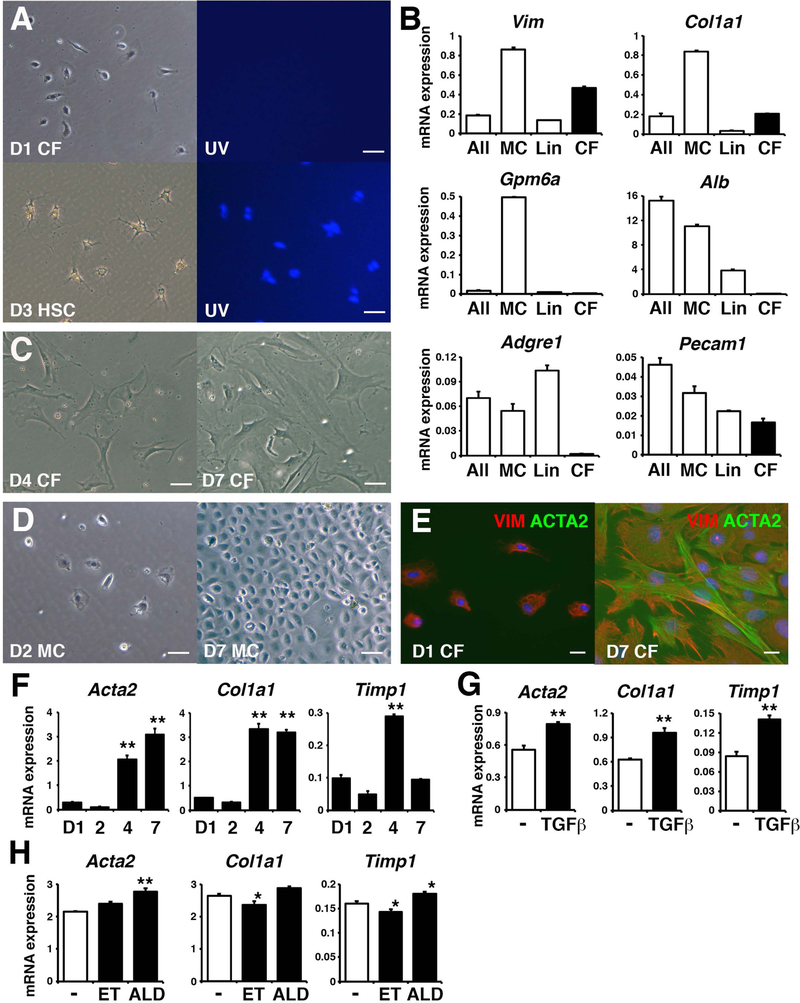

Differentiation of capsular fibroblasts to myofibroblasts in vitro

To examine whether capsular fibroblasts have the potential to differentiate into myofibroblasts, we attempted to isolate them from the mouse liver. From cells collected from the liver surface by enzymatic digestion, we depleted GPM6A+ mesothelial cells and blood lineage cells (Lin) by MACS. In culture, the resulting GPM6A−Lin− population showed fibroblastic morphology without autofluorescence of vitamin A like hepatic stellate cells (Fig. 7A). RT-QPCR showed that the GPM6A−Lin− population highly expresses mRNAs for Vim and Col1a1, but not for Gpm6a, Alb, Adgre1 (F4/80), and Pecam1 (Fig. 7B). In culture, the GPM6A−Lin− population spontaneously acquired myofibroblastic morphology from day 4 (Fig. 7C). GPM6A+ mesothelial cells formed epithelial cell colonies in culture and expressed Gpm6a mRNA (Fig. 7B,D). These data suggest that capsular fibroblasts are enriched in the GPM6A−Lin− population. Capsular fibroblasts cultured on day 1 were negative for ACTA2 and positive for VIM (94±2%), and became ACTA2+ myofibroblasts on day 7 (83±3%) (Fig. 7E). RT-QPCR revealed that capsular fibroblasts up-regulate the expression of Acta2 and Col1a1 mRNAs in culture (Fig. 7F). The expression of Timp1 mRNA was transiently increased in capsular fibroblasts on day 4. TGF-β1 treatment increased the expression of Acta2, Col1a1, and Timp1 mRNAs in capsular fibroblasts (Fig. 7G). Treatment with acetaldehyde, but not ethanol, weakly increased the expression of Acta2 and Timp1 mRNA in capsular fibroblasts (Fig. 7H). These data suggest that capsular fibroblasts have the potential to differentiate into myofibroblasts.

FIG. 7.

Differentiation of capsular fibroblasts to myofibroblasts in vitro. (A) Morphology of day 1 capsular fibroblasts and day 3 hepatic stellate cells isolated from the normal adult liver. Right panel shows autofluorescence of vitamin A in hepatic stellate cells. (B) mRNA expression. After digestion of the normal adult liver (All), we separated mesothelial cells (MC), blood lineage cells (Lin), and GPM6A−Lin− capsular fibroblasts (CF). Representative data from 4 independent preparations was shown. (C) Morphology of capsular fibroblasts cultured on day 4 and 7. (D) Morphology of mesothelial cells cultured on day 2 and 7. (E) Immunofluorescence staining of VIM (red) and ACTA2 (green) in capsular fibroblasts cultured on day 1 and 7. Bars, 50 μm (A,C,D) and 20 μm (E). (F-H) RT-QPCR of cultured capsular fibroblasts from day 1 to 7 (F), treated with TGF-β1 (G), and treated with ethanol (ET) or acetaldehyde (ALD) (H). *P< 0.05 and **P< 0.01 (against day 1 in F or control in H).

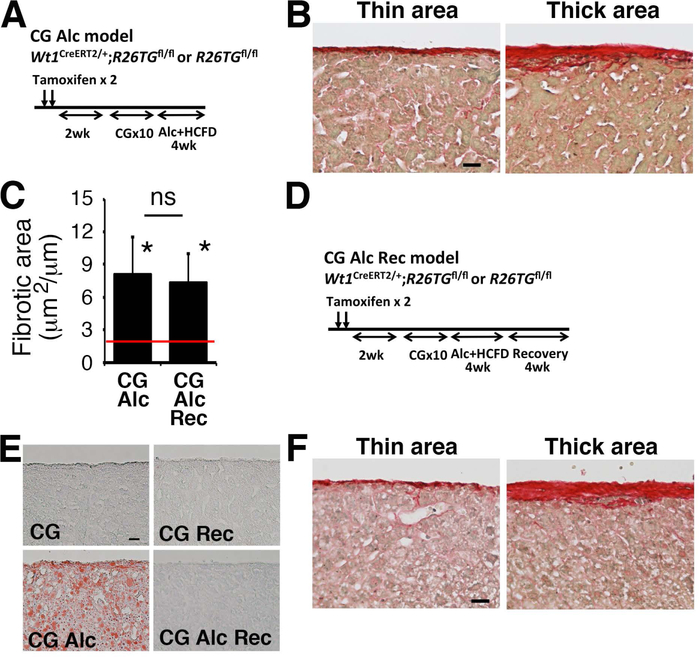

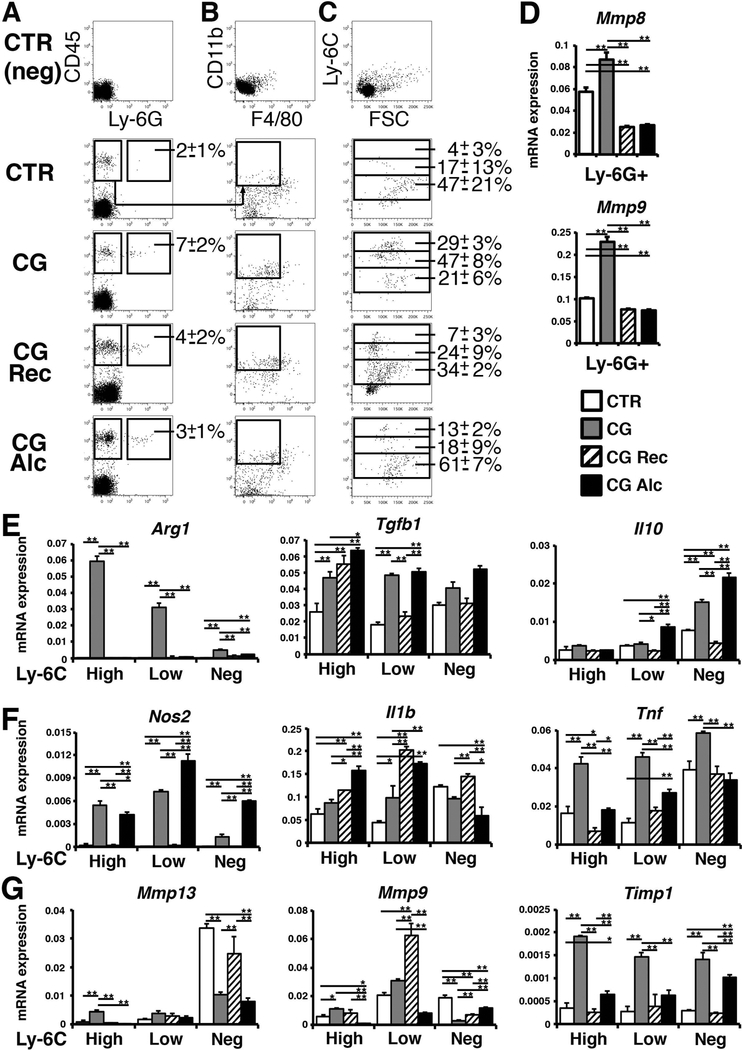

Alcohol intake reduces expression of Mmp13 and Mmp9 mRNAs in monocytes

Myeloid lineage cells contribute to tissue repair by secreting matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) enzymes.(19) To understand how alcohol intake impairs the resolution of capsular fibrosis, we examined myeloid lineage cells in the liver. After digestion of the liver surface, we separated CD45+Ly-6G+ neutrophils by FACS (Fig. 8A). The ratio of neutrophils in CD45+ cells was slightly increased in the CG model compared to the control liver (Fig. 8A). RT-QPCR showed that neutrophils increase expression of Mmp8 and Mmp9 mRNAs in the CG model, but their expression decreased in both the CG-Rec and CG-Alc models (Fig. 8D).

FIG. 8.

Separation of myeloid lineage cells from mouse livers. (A-C) Cells from the liver surface were prepared from the control (n=4), CG (n=4), CG-Rec (n=3), and CG-Alc models (n=4) and were analyzed by FACS. The average ratios of Ly-6G+ neutrophils in CD45+ cells were shown in A. From the CD45+Ly-6G− population, we separated CD11b+F4/80− monocytes in B. The average ratios of Ly-6CHigh, Ly-6CLow, and Ly-6C− monocytes in CD11b+ cells were shown in C. (D) RT-QPCR of CD45+Ly-6G+ neutrophils sorted in A. (E-G) RT-QPCR of M2 markers (E), M1 markers (F), and Mmp13, Mmp9, and Timp1 mRNAs (G) in Ly-6CHigh, Ly-6CLow, and Ly-6C− monocytes separated in C. *P< 0.05 and **P< 0.01.

To separate monocytes/macrophages, we first analyzed the staining of CD11b and F4/80 in the CD45+Ly-6G− population and detected only few F4/80+ macrophages in our preparation (Fig. 8B). Thus, we gated CD11b+F4/80− monocytes and further separated them based on the staining of Ly-6C (Fig. 8C). Compared to the control, the ratios of the Ly-6CHigh/CD11b+ and Ly-6CLow/CD11b+ populations were increased in the CG model but decreased in the CG-Rec and CG-Alc models (Fig. 8C). CG strongly induced Arg1 mRNA, a marker for M2 macrophages, in Ly-6CHigh/Low monocytes (Fig. 8E). The Ly-6CLow monocytes expressed Tgfb1 mRNA more highly in the CG-Alc model compared to the CG-Rec model (Fig. 8E). Similar to the CG model, the CG-Alc model showed high expression of Il10 in Ly-6C− monocytes, indicating that alcohol intake induces expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines in Ly-6CLow/- monocytes. Monocytes also increased the expression of Nos2, a marker for M1 macrophages, in both CG and CG-Alc models (Fig. 8F), suggesting that these monocytes are not simply classified into M1 or M2 phenotypes. Expression of Il1b mRNA remained high in Ly-6CLow monocytes in the CG-Rec and CG-Alc models and its expression was low in the Ly-6C− population in the CG-Alc model (Fig. 8F). Expression of Tnf mRNA was high in the CG model and decreased in both CG-Rec and CG-Alc models.

The Ly-6C− population highly expressed Mmp13 mRNA and its expression was low in the CG and CG-Alc models compared to that in the control and CG-Rec models (Fig. 8G). The Ly-6CLow population expressed Mmp9 mRNA in the CG-Rec model and its expression was strongly suppressed in the CG-Alc model (Fig. 8G). Monocytes increased the expression of Timp1 mRNA in the CG model, and alcohol intake maintained its expression in the Ly-6C− population in the CG-Alc model compared to the CG-Rec model (Fig. 8G). These data indicate that alcohol intake suppresses the degradation pathway of ECMs controlled by Ly-6CLow/- monocytes during the resolution of capsular fibrosis.

Discussion

In alcohol-induced liver fibrosis, the deposition of collagen fibers is mainly observed along the sinusoid and around the central vein.(1) The present study revealed that the deposition of collagen fiber also develops beneath the liver surface in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. The development of capsular fibrosis is also observed in cirrhotic livers caused by HCV infection, implying that capsular fibrosis is a common consequence in liver fibrosis caused by different etiology. Capsular fibrosis is characterized by the massive thickening of Glisson’s capsule, containing ACTA2+ myofibroblasts and disappearance of mesothelial cells from the liver surface. In patients with cirrhosis, the outer layer of capsular fibrosis is stained with Sirius red, but ACTA2+ myofibroblasts are relatively scarce, suggesting scar formation on the liver surface. The thickness of the liver surface Glisson’s capsule was known to correlate with the degree of liver fibrosis in CCl4-induced rat fibrosis.(20) Measurement of capsular fibrosis might help assess the progression of liver fibrosis.(21) Although the consequence of capsular fibrosis on liver function remains elusive, we assume that capsular fibrosis may contribute to an increase of the stiffness of the liver by forming fibrous scars on the liver surface.

In normal mouse livers, the connective tissue of Glisson’s capsule is underdeveloped beneath mesothelial cells and there are no bile ducts and veins just beneath the liver surface. On the other hand, in normal human livers, capsular fibroblasts are multilayered beneath the mesothelium and the bile duct develops in the connective tissue. The difference in the abundance of capsular fibroblasts might account for the massive development of capsular fibrosis in patients with alcoholic liver fibrosis compared to alcohol-fed mouse models. Similar to mice, Glisson’s capsule in adult rat or pike liver has a single stratum of capsular fibroblasts beneath the mesothelium.(11) Monkey liver shows double strata of capsular fibrosis and the sizes of porcine and bovine Glisson’s capsules were estimated to be 10–20 μm and 90 μm, respectively.(22,23) Although more comparative anatomical studies are necessary, Glisson’s capsule tends to be thicker in large animals. Compared to rodent livers, human livers have only two major lobes and a thickening of Glisson’s capsule may be necessary to protect the soft liver tissue and maintain the integrity of the structure.

In capsular fibrosis induced by CG injections, mesothelial cells differentiated into ACTA2+ myofibroblasts in areas with capsular fibrosis as we previously reported.(16) One month after CG injection, ACTA2+ myofibroblasts disappeared from the liver surface. In contrast, additional alcohol feeding during the recovery period sustained the presence of myofibroblasts beneath the liver surface. Interestingly, few mesothelial cell-derived myofibroblasts were observed in capsular fibrosis in the CG-Alc model, indicating that the contribution of mesothelial cells to myofibroblasts is transient in CG-induced capsular fibrosis. Capsular fibroblasts are present beneath mesothelial cells on the liver surface and they may be another source of myofibroblasts in capsular fibrosis. However, there are no markers or Cre mouse lines for identifying and tracing capsular fibroblasts beneath the liver surface. As an initial approach to characterize capsular fibroblasts, we enriched GPM6A−Lin− capsular fibroblasts from the adult liver surface. Cultured capsular fibroblasts spontaneously differentiated into ACTA2+ myofibroblasts and their differentiation was further induced by TGF-β1 or acetaldehyde, implying that capsular fibroblasts are likely to be another source of myofibroblasts in capsular fibrosis. Identification of specific markers for capsular fibroblasts is necessary to examine their contribution to capsular fibrosis.

Myeloid lineage cells play important roles in tissue repair by controlling ECM degradation and inflammation.(24) Accumulating evidence indicates functional heterogeneity of infiltrating monocytes, including classical inflammatory Ly-6CHigh monocytes and tissue repair Ly-6CLow monocytes, in liver disease.(25) It is known that CCR2+Ly-6CHigh monocytes are recruited to the injured liver and suppression of CCR2 signaling accelerates regression of liver fibrosis.(26) In sterile liver injury, infiltrating Ly-6CHigh monocytes were shown to differentiate into Ly-6CLow monocytes at the injury site.(27) In the present study, we found that Ly-6CLow/- monocytes, but not Ly-6CHigh monocytes, highly express Mmp13 (collagenase) and Mmp9 (gelatinase) genes during resolution of capsular fibrosis. MMP13 secreted from macrophages is known to facilitate the resolution of liver fibrosis.(28) In addition, Ly-6CLow monocytes are known to secrete MMP9 and accelerate fibrosis regression.(19) These data suggest that tissue repair Ly-6CLow/- monocytes contribute to the resolution of capsular fibrosis. A recent study identified F4/80+ capsular macrophages beneath the liver surface,(29) but the F4/80− monocytes we analyzed appear to be different cell types.

Different mouse models have been developed to reproduce alcoholic liver fibrosis.(1,17) Although the intragastric alcohol infusion model is known to cause severe alcoholic steatosis, fibrosis is generally mild. In fact, we did not observe development of capsular fibrosis in this model. Interestingly, we found that alcohol impaired the resolution of capsular fibrosis. Alcohol feeding significantly suppressed expression of Mmp13 and Mmp9 mRNAs, while increasing expression of Il10 mRNA in Ly-6CLow/- monocytes during resolution of capsular fibrosis. Our data suggest that dysregulation of Ly-6CLow/- monocytes is one of the mechanisms for impaired resolution of capsular fibrosis by alcohol. Alcohol is known to induce recruitment of monocytes to the liver and change the expression of cytokines in infiltrating monocytes.(30) It is also known that alcohol induces miR-27a in monocytes and increases IL-10 secretion.(31) By phagocytosis of dead hepatocytes, Ly-6CHigh monocytes change their phenotype toward a Ly-6CLow monocyte phenotype.(30) The effects of alcohol on infiltrating Ly-6CLow/- monocytes appear to be dependent on different injury conditions. Further studies are necessary to understand how alcohol regulates the phenotype and differentiation of monocytes in capsular fibrosis and its resolution.

The present study defines the formation of capsular fibrosis on the liver surface Glisson’s capsule, which has not been clearly described nor characterized before. Capsular fibrosis might be involved in an increase of liver stiffness and development of ascites in patients with cirrhosis and may be a potential therapeutic target for alleviation of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement:

We thank Drs. Shefali Chopra, Gary Kanel, and Hidekazu Tsukamoto for their comments on human liver pathology and Raul Lazaro, Janet Romo, and Qihong Yang for creating the alcohol-fed mouse models.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA020753 and R21AA024840 to K.A. and R21AA022751 to T.S.), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R21AI139954 to T.S.), and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK101773 to T.S.).

List of Abbreviations

- ACTA2

α-smooth muscle actin

- ALT

alanine transaminase

- BAL

blood alcohol level

- CG

chlorhexidine gluconate

- COLI

type I collagen

- COLIV

type IV collagen

- DES

desmin

- DCN

decorin

- E

embryonic day

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- FACS

fluorescence activated cell sorting

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GPM6A

glycoprotein M6A

- HCFD

high cholesterol fat diet

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- MACS

magnetic-activated cell sorting

- PDPN

podoplanin

- R26TGfl

Rosa26mTmGflox

- RT-QPCR

reverse transcription followed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- VIM

vimentin

- WT1

Wilms tumor 1

REFERENCES

- 1).Bataller R, Gao B. Liver fibrosis in alcoholic liver disease. Semin Liver Dis 2015;35:146–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Louvet A, Mathurin P. Alcoholic liver disease: mechanisms of injury and targeted treatment. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;12:231–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Nagy LE, Ding WX, Cresci G, Saikia P, Shah VH. Linking pathogenic mechanisms of alcoholic liver disease with clinical phenotypes. Gastroenterology 2016;150:1756–1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Tsuchida T, Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic stellate cell activation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;14:397–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Weiskirchen R, Weiskirchen S, Tacke F. Recent advances in understanding liver fibrosis: bridging basic science and individualized treatment concepts. F1000Res 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Iwaisako K, Jiang C, Zhang M, Cong M, Moore-Morris TJ, Park TJ, et al. Origin of myofibroblasts in the fibrotic liver in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:E3297–3305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Wells RG, Schwabe RF. Origin and function of myofibroblasts in the liver. Semin Liver Dis 2015;35:97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Lua I, Li Y, Zagory JA, Wang KS, French SW, Sevigny J, et al. Characterization of hepatic stellate cells, portal fibroblasts, and mesothelial cells in normal and fibrotic livers. J Hepatol 2016;64:1137–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Ovalle WK, Nahirney PC. Liver, gallbladder, and exocrine pancreas In: Ovalle WK, Nahirney PC, Netter’s Essential Histology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2013:311–334. [Google Scholar]

- 10).Bhunchet E, Wake K. Role of mesenchymal cell populations in porcine serum-induced rat liver fibrosis. Hepatology 1992;16:1452–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Chapman GB, Eagles DA. Ultrastructural features of Glisson’s capsule and the overlying mesothelium in rat, monkey and pike liver. Tissue Cell 2007;39:343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Niki T, De Bleser PJ, Xu G, Van Den Berg K, Wisse E, Geerts A. Comparison of glial fibrillary acidic protein and desmin staining in normal and CCl4-induced fibrotic rat livers. Hepatology 1996;23:1538–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Li Y, Wang J, Asahina K. Mesothelial cells give rise to hepatic stellate cells and myofibroblasts via mesothelial-mesenchymal transition in liver injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:2324–2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Asahina K, Zhou B, Pu WT, Tsukamoto H. Septum transversum-derived mesothelium gives rise to hepatic stellate cells and perivascular mesenchymal cells in developing mouse liver. Hepatology 2011;53:983–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Li Y, Lua I, French SW, Asahina K. Role of TGF-β signaling in differentiation of mesothelial cells to vitamin A-poor hepatic stellate cells in liver fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2016;310:G262–G272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Lua I, Li Y, Pappoe LS, Asahina K. Myofibroblastic conversion and regeneration of mesothelial cells in peritoneal and liver fibrosis. Am J Pathol 2015;185:3258–3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Lazaro R, Wu R, Lee S, Zhu NL, Chen CL, French SW, et al. Osteopontin deficiency does not prevent but promotes alcoholic neutrophilic hepatitis in mice. Hepatology 2015;61:129–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Ogawa T, Li Y, Lua I, Hartner A, Asahina K. Isolation of a unique hepatic stellate cell population expressing integrin alpha8 from embryonic mouse livers. Dev Dyn 2018;247:867–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Ramachandran P, Pellicoro A, Vernon MA, Boulter L, Aucott RL, Ali A, et al. Differential Ly-6C expression identifies the recruited macrophage phenotype, which orchestrates the regression of murine liver fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:E3186–3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Buschmann RJ, Ryoo JW. Hepatic structural correlates of liver fibrosis: a morphometric analysis. Exp Mol Pathol 1989;50:114–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Xu S, Kang CH, Gou X, Peng Q, Yan J, Zhuo S, et al. Quantification of liver fibrosis via second harmonic imaging of the Glisson’s capsule from liver surface. J Biophotonics 2016;9:351–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Umale S, Deck C, Bourdet N, Dhumane P, Soler L, Marescaux J, et al. Experimental mechanical characterization of abdominal organs: liver, kidney & spleen. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2013;17:22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Hollenstein MNA, Valtorta D, Snedeker JG, Mazza E. Mechanical characterization of the liver capsule and parenchyma. New York: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24).Krenkel O, Tacke F. Liver macrophages in tissue homeostasis and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2017;17:306–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Brempelis KJ, Crispe IN. Infiltrating monocytes in liver injury and repair. Clin Transl Immunology 2016;5:e113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Baeck C, Wei X, Bartneck M, Fech V, Heymann F, Gassler N, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of the chemokine C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (monocyte chemoattractant protein 1) accelerates liver fibrosis regression by suppressing Ly-6C(+) macrophage infiltration in mice. Hepatology 2014;59:1060–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Liew PX, Lee WY, Kubes P. iNKT cells orchestrate a switch from inflammation to resolution of sterile liver injury. Immunity 2017;47:752–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Fallowfield JA, Mizuno M, Kendall TJ, Constandinou CM, Benyon RC, Duffield JS, et al. Scar-associated macrophages are a major source of hepatic matrix metalloproteinase-13 and facilitate the resolution of murine hepatic fibrosis. J Immunol 2007;178:5288–5295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Sierro F, Evrard M, Rizzetto S, Melino M, Mitchell AJ, Florido M, et al. A liver capsular network of monocyte-derived macrophages restricts hepatic dissemination of intraperitoneal bacteria by neutrophil recruitment. Immunity 2017;47:374–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Wang M, You Q, Lor K, Chen F, Gao B, Ju C. Chronic alcohol ingestion modulates hepatic macrophage populations and functions in mice. J Leukoc Biol 2014;96:657–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Saha B, Bruneau JC, Kodys K, Szabo G. Alcohol-induced miR-27a regulates differentiation and M2 macrophage polarization of normal human monocytes. J Immunol 2015;194:3079–3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.