Abstract

We aimed to investigate the effects of aging and different exercise modalities on aversive memory and epigenetic landscapes at brain-derived neurotrophic factor, cFos, and DNA methyltransferase 3 alpha (Bdnf, cFos, and Dnmt3a, respectively) gene promoters in hippocampus of rats. Specifically, active epigenetic histone markers (H3K9ac, H3K4me3, and H4K8ac) and a repressive mark (H3K9me2) were evaluated. Adult and aged male Wistar rats (2 and 22 months old) were subjected to aerobic, acrobatic, resistance, or combined exercise modalities for 20 min, 3 times a week, during 12 weeks. Aging per se altered histone modifications at the promoters of Bdnf, cFos, and Dnmt3a. All exercise modalities improved both survival rate and aversive memory performance in aged animals (n = 7–10). Exercise altered hippocampal epigenetic marks in an age- and modality-dependent manner (n = 4–5). Aerobic and resistance modalities attenuated age-induced effects on hippocampal Bdnf promoter H3K4me3. Besides, exercise modalities which improved memory performance in aged rats were able to modify H3K9ac or H3K4me3 at the cFos promoter, which could increase gene transcription. Our results highlight biological mechanisms which support the efficacy of all tested exercise modalities attenuating memory deficits induced by aging.

Keywords: Exercise, Rats, Inhibitory avoidance, Aging, Histone methylation, Histone acetylation, Bdnf, cFos, Dnmt3a

Introduction

Preclinical and clinical studies have shown that physiological aging affects cognitive skills, such as short- and long-term memory [1–5]. Epigenetic mechanisms and the consequent loss of transcriptional activity have been associated to age-related impairments [6] and age-related illnesses, such as Alzheimer’s disease and various cancers [7–9]. Increased histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity and decreases in global H4 acetylation in hippocampus related to memory declines were demonstrated in aged rats [4, 10]. Age-related histone methylation changes have also been observed in animal models, such as decrease in global H3K9 methylation in the hippocampus [11]. Along with known age-related changes in histone modifications, changes in gene expression have been reported through the brain for several genes of interest [4]. Notably, genes related to learning and memory, including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), cFOS, and DNA methyltransferase 3a (DNMT3A), undergo substantial expression changes within the brain during the aging process [12–14], all of which were related to aging-induced cognitive impairments. However, histone modifications on promoters of these genes are rarely evaluated as a potential molecular mechanism.

Several lines of evidence indicate that regular exercise is beneficial during aging [15, 16], reducing mortality rates and improving brain functions as motor performance and cognition both in humans and animal models [17–21]. However, little is known regarding the benefits of beginning an exercise routine in an aged model and if different exercise modalities provide greater benefits than others in an age-specific manner. It has been presumed that some of exercise modality, such as aerobic, balance, and resistance, have greater influence on some parameters than on others, such as aerobic training is related to improvement of aerobic capacity and resistance training is associated with improved muscle mass [22]. Interestingly, the American Heart Association and American College of Sports Medicine recommend a combination of aerobic, resistance, and balance exercise for elderly patients in order to contribute to a healthy independent lifestyle, improving functional capacity, and cognitive performance [18, 23].

Different exercise modalities were able to improve memory in rodents during adulthood [24–26]. For example, 8 weeks of progressive resistance exercise improved aversive memory and increased peripheral and hippocampal IGF-1 levels [24]. To our knowledge, only aerobic modalities have been studied in normal aging models; 2 weeks of a moderate aerobic protocol reversed age-induced aversive memory impairment [4]. There are few studies investigating resistance, acrobatic, or combined exercise effects in memory tasks using animal models during aging process.

Epigenetic mechanisms have been proposed as modulators of the protective effects of exercise on memory. Previous data have shown an age-dependent effect of aerobic exercise on hippocampal epigenetic parameters using animal models; global histone acetylation, its enzymatic system, site-specific histone acetylation, and epigenetic landscapes at Bdnf gene promoter were studied. Daily aerobic exercise protocol during 2 weeks (20 min/day) improved aversive memory performance and hippocampal H4 acetylation in aged rats [4]. Additionally, this protocol increased acetylation of specific lysine residues (H4K12 and H3K9) in hippocampus of 20–21-month-old Wistar rats [27]. Aerobic exercise also induced hippocampal H3 acetylation at Bdnf gene promoter of 3-month-old rats, a crucial gene for learning, memory, and synaptic plasticity [28]. Besides, a single aerobic exercise session decreased both DNMT3b and DNMT1 levels in hippocampus of young adult rats, without any effect in the aged group [29]. Although the epigenetic mechanisms have not been investigated, resistance and acrobatic modalities increased Bdnf expression in the hippocampus [30, 31]. However, there is a dearth of information regarding the epigenetic modulation exerted by exercise modalities in the aging hippocampus.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the potential protective effects of different exercise modalities, aerobic, resistance, acrobatic, and their combination, on age-related declines in aversive memory and identify exercise-induced epigenetic mechanisms, specifically histone modifications, associated with aging and the protective effects of exercise within the hippocampus. We have focused on the promoter regions of three genes important for synaptic plasticity, neuronal activity, and neuronal development: Bdnf, cFos, and Dnmt3a [13, 32].

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Wistar (n = 76) rats aged 2 and 22 months were maintained under standard conditions (12-h light/dark, 22 C ± 2 °C), with food and water ad libitum. Animals were provided by the Centro de Reprodução e Experimentação de Animais de Laboratório (CREAL) at the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) and housed three per cage (Plexiglass cages, dimensions 40 × 33.3 × 17 cm). The NIH “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (NIH publication no. 80–23, revised 1996) was followed in all experiments. The Local Ethics Committee approved all handling and experimental conditions (no. 29818).

Exercise Protocols

Rats were randomly divided into five groups (n = 6–9): sedentary, aerobic, acrobatic, resistance, and combined. Experimental groups, except sedentary, were subjected to 20-min exercise sessions, three times a week in alternate days, for 12 weeks (experimental design in Fig. 1). Animals were habituated to each exercise modality by exposure to the different exercise apparatuses for 1 week prior to exercise protocol commenced. Sedentary animals were exposed to “sham” exercise protocols in that they were placed on a non-functional treadmill, acrobatic or resistance apparatus. Neither electric shock nor physical prodding was used in this study. All the procedures took place between 14:00 and 17:00.

Fig. 1.

Experimental design. I.A. inhibitory avoidance

Aerobic Protocol

Aerobic training was performed on a motorized rodent treadmill (AVS Projetos, São Paulo, Brazil) with individual Plexiglas lanes. The peak oxygen uptake (VO2) was indirectly measured in all animals prior to training. Each rat ran on a treadmill at a low initial speed, and the speed was increased at a rate of 5 m/min every 3 min until the point of exhaustion (i.e., failure of the rat to continue running). The time to fatigue (in min) and workload (in m/min) were obtained as indices of exercise capacity, which, in turn, were taken as VO2max [33, 34]. The aerobic training consisted of running sessions at 60% of VO2max [4]. The animals initially refusing to run were encouraged by gently tapping on their backs. VO2max was assessed every 3 weeks in order to increase treadmill speed according to the animal’s adaptation to exercise, maintaining training at 60% of VO2max.

Acrobatic Protocol

Acrobatic exercises were employed according to Jones et al. [35]. Animals were required to complete five activities six times each: [1] transverse a horizontal ladder (100 cm of diameter, 3 cm spaced rungs), [2] walk through an obstacle course (barriers 5 to 21 cm high), [3] cross a seesaw, [4] transverse a narrow bar (90 cm of diameter and 10 cm of width), and [5] transverse a rope (100 cm of diameter and 5 cm of width). The obstacles were changed, bars and rope were narrowed, and the space between the rungs of the ladder was increased every 3 weeks in order to increase the training difficulty [36].

Resistance Protocol

Resistance exercise training was performed as adapted from Gil and Kim [29], using a climbing ladder (height 1 m, inclination of 85°), which was designed to make the rats ascend towards a dark chamber (20 × 20 × 20 cm) with weight attached to their tails. Animals scaled the ladder in series of 8 repetitions with weight attached to their tails, with 2 min of rest. The weight for training was determined using 1 RM (repetition maximum) test performed prior to training, and animals climbed the ladder twice with 50% of their body weight attached to their tails. After successful completion of the task, 30 g were added for another trial (climbed ladder 2× plus 2 min of rest). This was repeated until animals were unable to climb the ladder and the weight was recorded as the maximum overload. Animals started the experiment climbing with 50% of the maximum overload attached to their tails; every 3 weeks, 10% of the maximum overload was added, until they reached the maximum of 80% of the overload in the last 3 weeks [29].

Survival Rate

Survival was tracked from the beginning of the study (22 months of age) until 25 months of age at which point animals were submitted to behavioral test and euthanized.

Memory Paradigm: Inhibitory Avoidance

We used single-trial step-down inhibitory avoidance conditioning as a model of fear-motivated memory in which the animals learned to associate a location in the training apparatus (a depressed area indicated by a grid floor) with an aversive stimulus (footshock). In the training trial, rats were placed on a platform and immediately after stepping down on the grid received a 0.6 mA, 3.0 s footshock prior to removal from the apparatus. The test trial took place 24 h after the training trial, in which the rats were placed in the platform and no footshock was delivered; latencies to step down were recorded and used as a measure of memory retention. Retention test latency measurements were cut off at 180 s. All animals were subjected to inhibitory avoidance test session 30 min after the last exercise session. The general procedures for inhibitory avoidance behavioral training and the retention test were described in a previous report [4, 37].

Preparation of the Samples

All rats were euthanized by decapitation 1 h after the last exercise session. The whole hippocampi were quickly dissected, immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then stored at −80 °C until the ChiP analysis.

qChIP

ChIP analysis of the frozen hippocampus (n = 4–5) was performed as previously described by Peña et al. [38] with minor modifications. Samples were cross-linked in 1% formaldehyde for 12 min at room temperature. The crosslinking reaction was stopped by adding glycine (2 M). Samples were homogenized in cold PBS with protease inhibitors (PIs), incubated in cold cell lysis buffer (5 mM PIPES pH 8, 85 mM KCl, 0.5% NP40) with PIs, and sonicated in cold nuclear lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS) with PIs at 4 °C for 30–40 cycles in a Bioruptor (Diagenode®) until average fragment size was 100–150 bp as assessed by BioAnalyzer (Agilent). Samples were frozen in aliquots at −80 °C until immunoprecipitation. Histone modifications (acetylation and methylation) were assessed using the following antibodies from Abcam: anti-acetyl(ac) H3K9ac (15823), H4K8ac (15823), anti-methyl(me) H3K9me2 (1220), and H3K4me3 (8580). Mouse and rabbit isotype control antibodies (37355 and 172730, respectively) were included as negative controls.

Magnetic beads (Dynabeads M-280 Sheep anti-Mouse/ Rabbit IgG) were blocked (4% BSA in PBS) and incubated with antibody at 4 °C for 6 h. One thousand nanograms of chromatin from each sample was incubated with antibody-bead mix overnight (16 h) for immunoprecipitation. Prior to antibody incubation, 10% aliquots were removed from each sample as input. Chromatin samples were then washed 1× each with low salt buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8), high salt buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA pH 8, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8), LiCl buffer (150 mM LiCl, 1% NP40, 1% NaDOC, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8), and TE buffer + NaCl (50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 1 mM EDTA). Samples were then eluted in buffer (1% SDS, 100 mM NaHCO3) and reverse cross-linked overnight at 65 °C. After RNAse and proteinase K incubations, DNA was purified using the PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen® 28106) and stored at 4 °C until qPCR analysis (Applied Biosystems QuantStudio®).

Primers for quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation (qChIP) (Integrated DNA Technologies®) were designed using Primer Blast (NCBI) to amplify promoter regions (Table 1). qChIP results, including IgG controls, were calculated as percent of input. All antibodies showed significant enrichment over their comparable IgG control (Supplemental Data 1).

Table 1.

Gene name, accession number, forward primer sequence, and reverse primer sequence of primer pairs used in quantitative PCR amplification

| Rat qChIP primers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Accession no. | Forward sequence | Reverse sequence |

| Bdnf (Exon 1) | NC_005102.4 | GGCAGTTGGACAGTCATTGG | GGGCGATCCACTGAGCAAAG |

| cFos | NC_005105.4 | CCGACTCCTTCTCCAGCATG | GCGGCAGGTTTACTCTGAGT |

| Dnmt3A | NC_005105.4 | TGGTGCCCAGGAAAGGAAAG | TGAGGCACCAATCTGAACCC |

Statistical Analysis

All data were evaluated for normal distribution and homogeneity of variance using Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Levene tests. The influence of age on inhibitory avoidance paradigm and epigenetic markers was evaluated by Student’s t test comparing only sedentary adult and sedentary aged animals. The exercise modalities effects on inhibitory avoidance paradigm and epigenetic markers were evaluated by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests. Survival rate was evaluated by Fisher’s exact test. In all tests, p ≤ 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Aging and Exercise Modalities Affects Aversive Memory Performance

First, baseline differences in YA vs aged sedentary controls were analyzed (Fig. 2). Student’s t test revealed that aged rats underperformed in the inhibitory avoidance paradigm (p = 0.03) compared to YA animals (Fig. 2a). Given the age-related changes observed between control groups, we analyzed the effects of exercise modalities within YA and aged animals separately. One-way ANOVA showed a main effect of exercise modalities on step-down latency in YA (F(4;41) = 17.3; p < 0.0001) and aged (F(4;37) = 3.63; p = 0.015) rats (Fig. 2b, c). Tukey’s post hoc analysis revealed that acrobatic (p = 0.005 and p = 0.022), aerobic (p = 0.002 and p = 0.031), and combined (p < 0.001 and p = 0.016) exercise enhanced memory performance in YA rats, and beyond these modalities, resistance exercise (p = 0.049) also ameliorated the age-related deficiencies observed in aged rats compared to sedentary animals. The p values refer to YA and aged rats, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Effect of aging and exercise modalities on step-down latency in inhibitory avoidance paradigm. Columns represent mean ± SD (n = 7–10). a Effect of aging on step-down latency. Student’s t test *values significantly different from the 5-month-old groups. b, c Effect of exercise on step-down latency in young adult and aged rats respectively. One-Way ANOVA; #values significantly different from the respective sedentary group

Exercise Improved Survival Rate in Aged Animals

Survival rate of aged animals was tracked from the beginning of the study (22 months of age) until the last exercise session (25 months of age). Late-life exercise increased rate of survival (96.7%) compared with the control group (45%) as evidenced by Fisher’s exact test (p = 0.002).

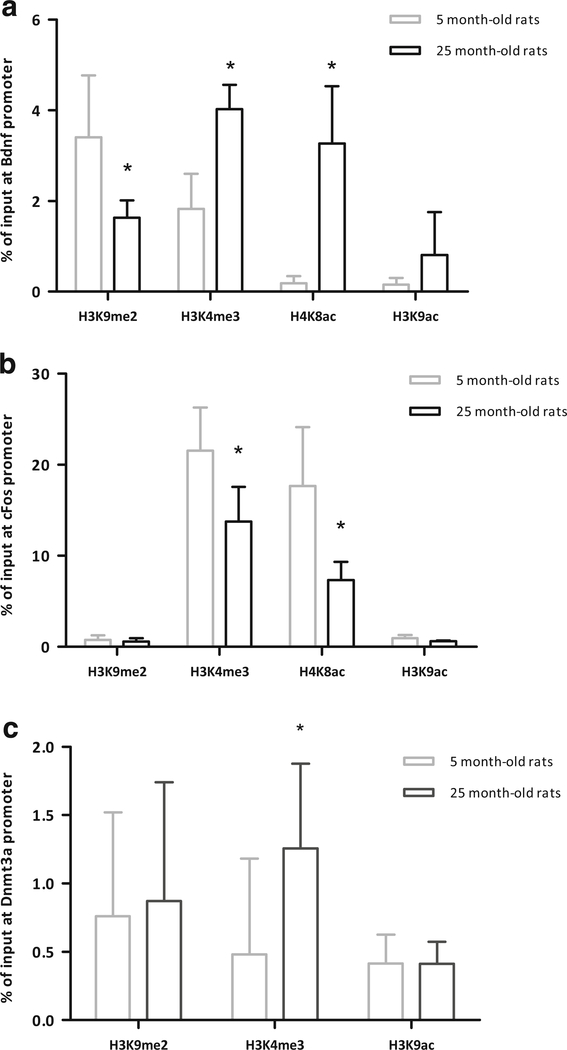

Aging Modulates Epigenetic Marks at the Bdnf, cFos, and Dnmt3a Gene Promoters in Hippocampus

We next evaluated the age-related alterations in histone modifications associated with 3 genes (Bdnf, cFos, and Dnmt3a) important for brain development, synaptic plasticity, and cognition [13, 28, 32] in the sedentary controls. Age-related changes were observed in histone methylation at Bdnf (Fig. 3a), cFos (Fig. 3b), and Dnmt3a (Fig. 3c). Specifically, H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) was decreased at the cFos promoter but increased (p = 0.007) at the Dnmt3a and Bdnf promoters (p = 0.04 and p = 0.001) in aged vs YA animals. Age-related effects were observed for H3K9 dimethylation (H3K9me2) at the Bdnf promoter (p = 0.05). Fewer age-related effects were observed with regard to histone acetylation. While no effects were observed in H3K9 acetylation (H3K9ac), H4K8 acetylation (H4K8ac) was increased at the Bdnf promoter (p = 0.002) and decreased at the cFos promoter (p = 0.01) in aged animals.

Fig. 3.

Effect of aging at the Bdnf, cFos, and Dnmt3a promoters in hippocampus of Wistar rats. a Effect of aging on acetylated (H4K8 and H3K9) and methylated (H3K9me2 and H3K4me3) chromatin. b Effect of aging on acetylated (H4K8 and H3K9) and methylated (H3K4me3 and H3K9me2) chromatin. c Effect of aging on acetylated (H3K9) and methylated (H3K4me3 and H3K9me2) chromatin. Columns represent mean ± SD (n = 4–5), and data are presented as percent input. Student’s t test *values significantly different from the 5-month-old groups

Exercise Modalities Influenced H4K8ac and H3K4me3 at the Bdnf Promoter in Hippocampus in an Age-Dependent Way

We hypothesized that the protective effects of exercise in the aged animals would be associated with changes in histone modifications at the Bdnf, cFos, and Dnmt3a promoters. Therefore, we analyzed changes in histone modifications in hippocampus after exercise in the YA and aged animals separately. The tested exercise modalities altered epigenetic parameters at the Bdnf promoter in an age-specific manner (Fig. 4a, b). One-way ANOVA showed the effect of exercise (F(4;20) = 4.43; p = 0.013); resistance (p = 0.029), acrobatic (p = 0.039), and aerobic (p = 0.027) modalities increased H4K8ac in YA rats. Meanwhile, in aged animals, exercise modalities decreased H3K4m e3 ( F(4;20) = 12.014; p < 0.0001) in aerobic (p = 0.012) and resistance (p = 0.012) groups.

Fig. 4.

Effect of exercise at the Bdnf promoter in hippocampus of Wistar rats. a Effect of exercise on H4K8ac chromatin. b Effect of exercise on H3K4me3 chromatin. Columns represent mean ± SD (n = 4–5), and data are presented as percent input. One-way ANOVA #values significantly different from the respective sedentary group

Exercise Modalities Altered H3K9ac or H3K4me3 at the cFos Promoter in Hippocampus in an Age-Dependent Way

One-way ANOVA demonstrated the effect of exercise on H3K9ac (Fig. 5a; F(4;21) = 5.17; p = 0.008) and H4K4me3 (Fig. 5b; F(4;21) = 3.92; p = 0.018) at the cFos promoter in a modality-dependent way only in aged rats. H3K9ac was induced in hippocampus by acrobatic (p = 0.04) and by aerobic (p = 0.05) protocols. Concurrently, acrobatic (p = 0.05) and combined (p = 0.03) increased H3K4me3 in this gene region.

Fig. 5.

Effect of exercise at the cFos promoter in hippocampus of Wistar rats. a Effect of exercise on H3k9ac chromatin. b Effect of exercise on H3K4me3 chromatin. Columns represent mean ± SD (n = 4–5) and data are presented as percent input. One-way ANOVA #values significantly different from the respective sedentary group

Resistance and Combined Protocols Decreased H4K8ac at the Dnmt3a Promoter in Hippocampus in an Age-Dependent Way

We observed an effect of exercise (F(4;20) = 4.517; p = 0.014) on H4K8ac at the Dnmt3a promoter in adult animals in a modality-dependent way (Fig. 6). Resistance (p = 0.048) and combined (p = 0.012) groups exhibited lower H4K8ac levels in hippocampus compared to the sedentary group in YA animals. In contrast, there was no effect of exercise on aged animals.

Fig. 6.

Effect of exercise on H4K8ac chromatin at the Dnmt3apromoter in hippocampus of Wistar rats. Columns represent mean ± SD (n = 4–5) and data are presented as percent input. One-way ANOVA #values significantly different from the respective sedentary group

Discussion

The central purpose of this study was to compare the efficacy of different exercise modalities starting later in life on functional parameters, such as survival rate and aversive memory performance, as well as on hippocampal epigenetic marks at three important genes for memory formation, Bdnf, cFos, and Dnmt3a [13, 28, 32]. In addition, our experimental design allows us to study the age-induced epigenetic modifications on these genes. This work supports the hypothesis that aging process induces epigenetic modifications of histones at promoters of genes related to learning and memory, which can be attenuated, at least partially, by exercise.

Aging Impacts Aversive Memory Performance and Epigenetic Marks

The present work showed age-related deficits in memory performance, in agreement with previous reports [4, 39, 40]. It is important to describe that the impact of aging on BDNF, cFOS, and DNMT3A expression have been determined in brain areas previously [13, 28, 41]. In order to identify potential molecular mechanisms underlying this impairment, we first examined histone modifications associated with promoters of genes related to learning and memory in the hippocampus: Bdnf, cFos, and Dnmt3a [13, 28, 32].

We observed lower H3K9me2 and increased H4K8ac and H3K4me3 at the Bdnf promoter in hippocampus of aged rats. Taken that H3K9me2 is a repressive mark related to gene silencing [42], while H4K8ac and H3K4me3 are associated to transcriptional activation [43], our results suggest a chromatin landscape aiding Bdnf transcription in healthy aged animals. Previous literature suggests that expression of a Bdnf precursor, proBDNF, was augmented in the hippocampus of 24-month-old Wistar rats [12] and 22–24 months old C57BL/6 mice [44], which is in agreement our findings. Considering that proBDNF processing into mature BDNF occurs at different rates over the lifespan [12, 45], it is possible to suggest that aged hippocampus has higher proBDNF levels. Considering that this immature protein has been proposed to play a role in neuronal apoptosis [46], inhibiting neuronal migration [47], leading to memory impairment [44], and inducing hippocampal long-term depression (LTD), proBDNF may oppose the known effects of its mature counterpart on memory [48].

Regarding the cFos promoter, our results demonstrate reductions in H3K4me3 and H4K8ac, both associated with transcriptional activation, in aged animals [43]. These data corroborate previous research demonstrating regulation of cFos expression by aging [13, 49]. In this context, age-related reduction in Cfos protein levels was found in brain regions such as hippocampus, hypothalamus, striatum, cerebral cortex, and cerebellum of rats, probably owing to reduced neuronal activity during senescence. In addition, decreased cFos expression was observed in hippocampus of middle-aged mice with visuospatial memory impairment [50]. This report may be related to ours and reinforce the evidence that cFos expression has an important role in memory impairment during aging. Since Ono et al. did not show alterations in cFos gene DNA methylation in the whole brain [51], our results support histone modifications as possible epigenetic mechanisms mediating age-related alterations in cFos expression.

Age-related effects in hippocampal Dnmt3a promoter regulation were also observed. DNMT3A is an important enzyme for de novo DNA methylation, which is strongly associated with gene repression [17, 52]. Also, the Dnmt3a gene is necessary for normal memory formation [53–55]. A previous report by Morris et al. demonstrated that Dnmt3a knockout mice have synaptic alterations as well as learning deficits in several associative and episodic memory tasks [55]. Here, we observed an increase in hippocampal H3K4me3 at the Dnmt3a promoter associated to age that can be related to increased Dnmt3a expression and consequently increased DNA methylation. Our finding is in agreement with recent literature questioning the paradigm of global DNA hypomethylation in aging [56], since it has been observed that levels of 5-methylcytosine (5-mC), 5-hydroxymehtylcytosine (5-hmC), and DNMT3A are augmented in brain tissue, especially in hippocampus [41, 57, 58]. Our data may be related to findings obtained by Chouliaras et al., who observed enhancement of Dnmt3a expression in 24-month-old mice [57]. Furthermore, Daniele et al. demonstrated that DNA methylation in peripheral blood was significantly higher in elderly individuals [59]. This work contributed to the understanding of how aging process regulate hippocampal epigenetic histone marks at three important genes for memory formation, Bdnf, cFos, and Dnmt3a.

Exercise Modalities Improved Survival Rate and Aversive Memory Performance

All exercise modalities improved both survival rate and aversive memory performance in aged animals. Understanding how exercise modalities produce cognitive health benefits in an aging population is vital to our ability to producing individualized exercise prescription that respect the needs and characteristics of the older individuals and help to increase adherence to exercise programs.

Previous studies demonstrated that exercise (specifically aerobic protocols) is able to increase lifespan in disease model [20, 60, 61] and healthy rodents [62], even when started late in life. Here, our results add evidences to those findings, since all exercise modalities impacted similarly on survival rate in aged rats. This interesting data indicates that exercise results in a healthier global status, probably owing improvements on—including gene expression involved with—immune responses, metabolism, angiogenesis, and other physiological processes as observed in previous clinical studies [63–67].

A growing body of evidence suggests that aerobic exercise is able to prevent and/or improve aging-induced memory declines [27, 68–70]. Here, all tested modalities, aerobic, resistance, acrobatic, and combination, reversed partially age-related memory declines. Besides, exercise modalities, except resistance exercise, improved aversive memory performance in YA rats. Previously, we showed that daily aerobic exercise, 20 min/day for 2 weeks, improved aversive memory performance in both YA and aged rats [4, 27]. Now, our findings demonstrate a similar effect on memory performance can be obtained with a long-term duration protocol of aerobic exercise, with different frequency of training, e.g., 12 weeks, three times a week, during 20 min.

Interestingly, our resistance protocol was unable to improve aversive memory performance in YA rodents. In contrast, this modality (5 times a week) improved passive avoidance task and spatial memory performance in 3-month-old rats [24, 71], suggesting that YA animals require greater training frequencies to achieve memory improvements. Our findings are in accordance with previous studies evaluating resistance exercise effects in humans and animal models [72, 73].

The American College of Sports and Medicine recommends a combination of exercise modalities for elderly populations to improve general health [15]. However, our combined modality did not show better outcomes than other modalities. Previously, cognitive effects of combined modalities have been evaluated in YA rodents. Zarrinkalam et al. compared endurance, resistance, and combined exercise (resistance and endurance) and showed selective effects of these modalities on spatial and aversive memory in YA rats submitted to a morphine addiction model, which leads to memory impairment [74]. The results here reported showed the combined exercise benefits on aversive memory performance in both tested ages, providing rational basis for the clinical recommendation during life span.

Taken together, our results indicate that all studied exercise modalities are able to impact in general health, decreasing mortality, and also are beneficial to memory during aging process. This data may support individualized prescription of these modalities, according individual needs, goals, and health conditions, which could increase the adherence to exercise in elderly.

Exercise Modalities Affect Histone Marks at the Bdnf, cFos, and Dnmt3a Promoters

In addition to the functional findings, we also investigated how exercise impacted on the hippocampal epigenetic histone marks. An age-dependent effect on the Bdnf promoter was observed, since aerobic and resistance aged groups had decreased hippocampal Bdnf promoter H3K4me3 and also ameliorated memory age-induced impairment, suggesting that these protocols can attenuate aging effects, and could lead to a reduction in gene transcription and consequently reduced levels of proBDNF. Conversely, YA rats submitted to resistance, acrobatic, and aerobic modalities had increased hippocampal Bdnf promoter H4K8ac, an active epigenetic histone mark, which may indicate an increase in Bdnf transcription. Previous reports have described the impact of several exercise modalities on Bdnf expression. Aerobic exercise increased Bdnf expression in YA [28] and adolescent rodents [75]. Klintsova and colleagues [30] also observed increased levels in BDNF expression in motor cortex and cerebellum in YA rats after acrobatic training [30]; however, for the first time, the effects of acrobatic exercise on hippocampal Bdnf epigenetic regulation have been described. In addition, it is possible to suggest that longer training periods are necessary for resistance training to modulate Bdnf expression, since our protocol of 12 weeks increased hippocampal Bdnf promoter H4K8ac, while other during 4 or 8 weeks did not alter hippocampal Bdnf expression in YA rats [24, 31]. Surprisingly, our combined modality did not regulate epigenetically the Bdnf promoter, which can be related to previous reports demonstrating that multicomponent exercise was unable to impact peripheral blood BDNF levels in humans [76]. Taken that resistance modality did not affect cognitive outcomes in YA animals even with increased Bdnf H4K8ac, while combined exercise improved memory performance without any effect on this histone modification, it is possible to infer that cognitive effects of exercise cannot be attributed exclusively to Bdnf H4K8ac modulation.

Regarding cFos promoter, it is important to note that acrobatic, aerobic, and combined exercise improved memory performance and concomitantly affected hippocampal active epigenetic histone marks, specifically H3K9ac and/or H3K4me3, at cFos promoter in aged rats. Aerobic exercise has been pointed out as capable of attenuating cognitive decline and epigenetic repression promoted by age [27]. In this study, this modality induced an age-dependent effect, since we observed increased hippocampal H3K9ac at the cFos promoter only in aged groups, which could be related to augmented gene expression. This result suggests that aerobic exercise alters this mark in adverse situations, such as during aging. In accordance, swimming increased hippocampal H3K9ac and cFos expression in animals submitted to an isoflurane-induced memory impairment paradigm without any effect in animals not exposed to isoflurane [77].

Acrobatic modality induced two epigenetic modifications, H3K9ac and H3K4me3, at the cFos promoter in aged animals, which would suggest transcriptional activation. In accordance, previous studies reported increased cFos expression in motor cortex after acrobatic training in rodents [78]. In addition to the management of the postural instability and improve balance [79] in elderly people, this work brings a new perspective about acrobatic exercise effects on aversive memory in aging and highlights the involvement of hippocampal epigenetic regulation.

Our study is the first report of the impact of combined exercise, including aerobic, resistance, and acrobatic training, in animal models. Our combined protocol had similar effects as acrobatic and aerobic protocols on memory performance, and concomitantly was able to induce epigenetic changes, specifically H3K4me3, in hippocampal at the cFos promoter. The relevance to clinical practice is based on the fact that the spent time with each component is reduced in combined modality, allowing individuals with some limitations to achieve full beneficial response as well.

Evidence shows that DNA methylation is an important mechanism by which exercise affects gene expression. In this study, age- and modality-associated effects were observed in epigenetic marks at the Dnmt3a promoter, given that resistance and combined protocols decreased hippocampal H4K8ac in YA rats, which might decrease its expression. Moreover, exercise modalities did not induce any effect in aged animals. Together, we could exclude the involvement of epigenetic modulation of exercise at the Dnmt3a promoter in hippocampus on functional improvement observed during aging. Although the aerobic protocol used here (12 weeks, 3 times a week) did not modify any studied epigenetic marks (H3K9ac, H3K4me3, H3K9me2, and H4K8ac) at the Dnmt3a promoter, previously our research group and others showed exercise modulation of hippocampal DNMT levels in YA rodents [11, 75, 80]. In this context, Elsner and colleagues (2013) observed modulation of DNMT3B levels after a single session of aerobic exercise in 3 month-old rats, without any effect in aged animals [11]. Moreover, Abel and colleagues (2013) observed decreased Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b, and Dnmt1 expression in adolescent mice exercised with voluntary wheel running [75]. Comparing these data with our results, it is possible to suggest an age-dependent component in this response.

Conclusions

Results of the current study support the hypothesis that exercise training starting in late adulthood impacts age-related cognitive declines, since resistance, acrobatic, aerobic, and combined modalities were able to improve aversive memory performance in aged rats and that epigenetic mechanisms at hippocampal Bdnf, cFos, and Dnmt3a promoters may be involved with both aging process and exercise effects. These insights provide a substantial basis for rational prescription of exercise modalities in the elderly population, not only for metabolic and cardiovascular improvements, but also for cognitive benefits, what can be exploited as a potential therapeutic strategy to reduce memory disorders during aging.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Information This work was supported, in part, by grant PDSE -88881.135752/2016-01 from Comissão de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal (CAPES) from Brazil and P50MH096890 from the US National Institute of Mental Health (E.J. Nestler). CNPq fellowships (Dr. I.R. Siqueira; L.C.F. Meireles, K. Bertoldi and L. R. Cechinel) CAPES fellowship Galvão).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The NIH “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (NIH publication no. 80–23, revised 1996) was followed in all experiments. The Local Ethics Committee approved all handling and experimental conditions (no. 29818).

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-019-01675-w) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hansen RT, Zhang H-T (2013) Senescent-induced dysregulation of cAMP/CREB signaling and correlations with cognitive decline. Brain Res 1516:93–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Podtelezhnikov AA, Tanis KQ, Nebozhyn M, Ray WJ, Stone DJ, Loboda AP (2011) Molecular insights into the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease and its relationship to normal aging. PLoS One 6(12):e29610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barreto G, Huang T-T, Giffard RG (2010) Age-related defects in sensorimotor activity, spatial learning and memory in C57BL/6 mice. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 22(3):214–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lovatel GA, Elsner VR, Bertoldi K, Vanzella C, Moysés Fdos S, Vizuete A, et al. Treadmill exercise induces age-related changes in aversive memory, neuroinflammatory and epigenetic processes in the rat hippocampus. Neurobiol Learn Mem 2013;101(0):94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McQuail JA, Beas BS, Kelly KB, Simpson KL, Frazier CJ, Setlow B et al. (2016) NR2A-containing NMDARs in the prefrontal cortex are required for working memory and associated with age-related cognitive decline. J Neurosci 36(50):12537–12548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peleg S, Feller C, Ladurner AG, Imhof A (2016) The metabolic impact on histone acetylation and transcription in ageing. Trends Biochem Sci 41(8):700–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blasi T, Feller C, Feigelman J, Hasenauer J, Imhof A, Theis FJ, Becker PB, Marr C (2016) Combinatorial histone acetylation patterns are generated by motif-specific reactions. Cell Syst 2(1):49–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benayoun BA, Pollina EA, Brunet A (2015) Epigenetic regulation of ageing: linking environmental inputs to genomic stability. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 16:593–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawson MA, Kouzarides T (2012) Cancer epigenetics: from mechanism to therapy. Cell. 150(1):12–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.dos Santos Sant’ AG, Rostirola Elsner V, Moysés F, Reck Cechinel L, Agustini Lovatel G, Rodrigues Siqueira I Histone deacetylase activity is altered in brain areas from aged rats. Neurosci Lett [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elsner VR, Lovatel GA, Moysés F, Bertoldi K, Spindler C, Cechinel LR, Muotri AR, Siqueira IR (2013) Exercise induces age-dependent changes on epigenetic parameters in rat hippocampus: a preliminary study. Exp Gerontol 48(2):136–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perovic M, Tesic V, Djordjevic AM, Smiljanic K, Loncarevic-Vasiljkovic N, Ruzdijic S et al. (2013) BDNF transcripts, proBDNF and proNGF, in the cortex and hippocampus throughout the life span of the rat. AGE. 35(6):2057–2070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitraki E, Bozas E, Philippdis H, Stylianopoulou F. Aging-related changes in IGF-II and c-fos gene expression in the rat brain. Int J Dev Neurosci 1993;11(1):1–9, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desjardins S, Mayo W, Vallée M, Hancock D, Le Moal M, Simon H et al. Effect of aging on the basal expression of c-fos, c-jun, and egr-1 proteins in the hippocampus. Neurobiol Aging 18(1):37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chodzko-Zajko WJ, Proctor DN, Fiatarone Singh MA, Minson CT, Nigg CR, Salem GJ et al. (2009) Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 41(7):1510–1530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang S, Hwang S, Klein AB, Kim SH (2015) Multicomponent exercise for physical fitness of community-dwelling elderly women. J Phys Ther Sci 27(3):911–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akbarian S, Beeri M, Haroutunian V (2013) Epigenetic determinants of healthy and diseased brain aging and cognition. JAMA Neurol 70(6):711–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson ME, Rejeski J, Blair SN, Duncan PW, Judge JO, King AC et al. (2007) Physical activity and public health in older adults: recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation 116:1094–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venturelli M, Schena F, Richardson RS (2012) The role of exercise capacity in the health and longevity of centenarians. Maturitas. 73(2):115–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright KJ, Thomas MM, Betik AC, Belke D, Hepple RT (2014) Exercise training initiated in late middle age attenuates cardiac fibrosis and advanced glycation end-product accumulation in senescent rats. Exp Gerontol 50:9–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wen CP, Wai JPM, Tsai MK, Yang YC, Cheng TYD, Lee M-C, Chan HT, Tsao CK et al. (2011) Minimum amount of physical activity for reduced mortality and extended life expectancy: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Lond Engl 378(9798):1244–1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coffey VG, Hawley JA (2007) The molecular bases of training adaptation. Sports Med Auckl NZ 37(9):737–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM et al. (2011) American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 43(7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cassilhas RC, Lee KS, Fernandes J, Oliveira MGM, Tufik S, Meeusen R, de Mello MT (2012) Spatial memory is improved by aerobic and resistance exercise through divergent molecular mechanisms. Neuroscience. 202(0):309–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berchtold NC, Castello N, Cotman CW (2010) Exercise and time-dependent benefits to learning and memory. Neuroscience. 167(3): 588–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cotman CW, Berchtold NC (2002) Exercise: a behavioral intervention to enhance brain health and plasticity. Trends Neurosci 25(6): 295–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Meireles LCF, Bertoldi K, Cechinel LR, Schallenberger BL, da Silva VK, Schröder N, Siqueira IR (2016) Treadmill exercise induces selective changes in hippocampal histone acetylation during the aging process in rats. Neurosci Lett 634:19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez-Pinilla F, Zhuang Y, Feng J, Ying Z, Fan G (2011) Exercise impacts brain-derived neurotrophic factor plasticity by engaging mechanisms of epigenetic regulation. Eur J Neurosci 33(3):383–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gil JH, Kim CK (2015) Effects of different doses of leucine ingestion following eight weeks of resistance exercise on protein synthesis and hypertrophy of skeletal muscle in rats. J Exerc Nutr Biochem 19(1):31–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klintsova AY, Dickson E, Yoshida R, Greenough WT (2004) Altered expression of BDNF and its high-affinity receptor TrkB in response to complex motor learning and moderate exercise. Brain Res 1028(1):92–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Novaes Gomes FG, Fernandes J, Vannucci Campos D, Cassilhas RC, Viana GM, D’Almeida V, de Moraes Rêgo MK, Buainain PI et al. (2014) The beneficial effects of strength exercise on hippocampal cell proliferation and apoptotic signaling is impaired by anabolic androgenic steroids. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 50:106–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bayraktar G, Kreutz MR (2017) Neuronal DNA methyltransferases: epigenetic mediators between synaptic activity and gene expression? Neuroscientist 24(2):1073858417707457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arida RM, Scorza FA, dos Santos NF, Peres CA, Cavalheiro EA (1999) Effect of physical exercise on seizure occurrence in a model of temporal lobe epilepsy in rats. Epilepsy Res 37(1):45–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brooks GA, White TP (1978) Determination of metabolic and heart rate responses of rats to treadmill exercise. J Appl Physiol 45(6): 1009–1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones TA, Chu CJ, Grande LA, Gregory AD (1999) Motor skills training enhances lesion-induced structural plasticity in the motor cortex of adult rats. J Neurosci 19(22):10153–10163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Black JE, Isaacs KR, Anderson BJ, Alcantara AA, Greenough WT (1990) Learning causes synaptogenesis, whereas motor activity causes angiogenesis, in cerebellar cortex of adult rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87(14):5568–5572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lovatel GA, Bertoldi K, Elsner VR, Vanzella C, Moysés Fdos S, Spindler C et al. (2012) Time-dependent effects of treadmill exercise on aversive memory and cyclooxygenase pathway function. Neurobiol Learn Mem 98(2):182–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peña CJ, Kronman HG, Walker DM, Cates HM, Bagot RC, Purushothaman I, Issler O, Loh YHE et al. (2017) Early life stress confers lifelong stress susceptibility in mice via ventral tegmental area OTX2. Science. 356(6343):1185–1188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yankner BA, Lu T, Loerch P (2008) The aging brain. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis 3:41–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erickson CA, Barnes CA (2003) The neurobiology of memory changes in normal aging. Exp Gerontol 38(1–2):61–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ianov L, Riva A, Kumar A, Foster TC (2017) DNA methylation of synaptic genes in the prefrontal cortex is associated with aging and age-related cognitive impairment. Front Aging Neurosci 9:249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta S, Kim SY, Artis S, Molfese DL, Schumacher A, Sweatt JD, Paylor RE, Lubin FD (2010) Histone methylation regulates memory formation. J Neurosci 30(10):3589–3599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Z, Zang C, Rosenfeld JA, Schones DE, Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY et al. (2008) Combinatorial patterns of histone acetylations and methylations in the human genome. Nat Genet 40(7):897–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buhusi M, Etheredge C, Granholm A-C, Buhusi CV (2017) Increased hippocampal proBDNF contributes to memory impairments in aged mice. Front Aging Neurosci 9:284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silhol M, Arancibia S, Maurice T, Tapia-Arancibia L (2007) Spatial memory training modifies the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor tyrosine kinase receptors in young and aged rats. Neuroscience. 146(3):962–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teng HK, Teng KK, Lee R, Wright S, Tevar S, Almeida RD et al. (2005) ProBDNF induces neuronal apoptosis via activation of a receptor complex of p75NTR and Sortilin. J Neurosci 25(22): 5455–5463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu Z-Q, Sun Y, Li H-Y, Lim Y, Zhong J-H, Zhou X-F (2011) Endogenous proBDNF is a negative regulator of migration of cerebellar granule cells in neonatal mice. Eur J Neurosci 33(8):1376–1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woo NH, Teng HK, Siao C-J, Chiaruttini C, Pang PT, Milner TA et al. (2005) Activation of p75NTR by proBDNF facilitates hippocampal long-term depression. Nat Neurosci 8(8):1069–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li H, Liang A, Guan F, Fan R, Chi L, Yang B (2013) Regular treadmill running improves spatial learning and memory performance in young mice through increased hippocampal neurogenesis and decreased stress. Brain Res 1531(0):1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Y, Abdourahman A, Tamm JA, Pehrson AL, Sánchez C, Gulinello M (2015) Reversal of age-associated cognitive deficits is accompanied by increased plasticity-related gene expression after chronic antidepressant administration in middle-aged mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 135(Supplement C):70–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ono T, Uehara Y, Kurishita A, Tawa R, Sakurai H (1993) Biological significance of DNA methylation in the ageing process. Age Ageing 22(suppl_1):S34–S43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Graff J, Mansuy IM (2009) Epigenetic dysregulation in cognitive disorders. Eur J Neurosci 30:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bird A (2002) DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev 16(1):6–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feng J, Zhou Y, Campbell SL, Le T, Li E, Sweatt JD et al. (2010) Dnmt1 and Dnmt3a maintain DNA methylation and regulate synaptic function in adult forebrain neurons. Nat Neurosci 13:423–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morris MJ, Adachi M, Na ES, Monteggia LM (2014) Selective role for DNMT3a in learning and memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem 115: 30–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jung M, Pfeifer GP (2015) Aging and DNA methylation. BMC Biol 13:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chouliaras L, van den Hove DLA, Kenis G, Dela Cruz J, Lemmens MAM, van Os J et al. (2011) Caloric restriction attenuates age-related changes of DNA methyltransferase 3a in mouse hippocampus. Brain Behav Immun 25(4):616–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chouliaras L, van den Hove DLA, Kenis G, Keitel S, Hof PR, van Os J et al. (2012) Age-related increase in levels of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mouse hippocampus is prevented by caloric restriction. Curr Alzheimer Res 9(5):536–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Daniele S, Costa B, Pietrobono D, Giacomelli C, Iofrida C, Trincavelli ML, Fusi J, Franzoni F et al. (2018) Epigenetic modifications of the α-synuclein gene and relative protein content are affected by ageing and physical exercise in blood from healthy subjects. Oxidative Med Cell Longev 2018:1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cannon JG, Kluger MJ (1984) Exercise enhances survival rate in mice infected with Salmonella typhimurium. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 175(4):518–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Betik AC, Thomas MM, Wright KJ, Riel CD, Hepple RT (2009) Exercise training from late middle age until senescence does not attenuate the declines in skeletal muscle aerobic function. Am J Phys Regul Integr Comp Phys 297(3):R744–R755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holloszy JO, Smith EK, Vining M, Adams S (1985) Effect of voluntary exercise on longevity of rats. J Appl Physiol 59(3):826–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Simpson RJ, Lowder TW, Spielmann G, Bigley AB, LaVoy EC, Kunz H (2012) Exercise and the aging immune system. Ageing Res Rev 11(3):404–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koopman R, van Loon LJC (2009) Aging, exercise, and muscle protein metabolism. J Appl Physiol 106(6):2040–2048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Elsner VR, José Cunha J, Ineu Figueiredo A, Pires Dorneles G, Peres A, Pochmann D, Padilha de Souza M (2017) The running practice modulates inflammatory markers and not alters global DNA methylation in elderly men. J Exerc Sports Orthop 4(3):1–6 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Figueiredo AI, Jose Cunha J, Reichert Vital da Silva I, Luna Martins L, Bard A, Reinaldo G, et al. Running-induced functional mobility improvement in the elderly males is driven by enhanced plasma BDNF levels and the modulation of global histone H4 acetylation status. Middle East J Rehabil Health [Internet]. 2017. July 11 [cited 2019 May 26];In Press (In Press). Available from: http://jrehabilhealth.neoscriber.org/en/articles/57486.html [Google Scholar]

- 67.da Silva IRV, de Araujo CLP, Dorneles GP, Peres A, Bard AL, Reinaldo G, Teixeira PJZ, Lago PD et al. (2017. August) Exercise-modulated epigenetic markers and inflammatory response in COPD individuals: A pilot study. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 242: 89–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Segal SK, Cotman CW, Cahill LF (2012) Exercise-induced noradrenergic activation enhances memory consolidation in both normal aging and patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 32(4):1011–1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Speisman RB, Kumar A, Rani A, Foster TC, Ormerod BK (2013) Daily exercise improves memory, stimulates hippocampal neurogenesis and modulates immune and neuroimmune cytokines in aging rats. Brain Behav Immun 28(0):25–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aguiar AS Jr, Castro AA, Moreira EL, Glaser V, Santos ARS, Tasca CI et al. (2011) Short bouts of mild-intensity physical exercise improve spatial learning and memory in aging rats: involvement of hippocampal plasticity via AKT, CREB and BDNF signaling. Mech Ageing Dev 132:560–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cassilhas RC, Lee KS, Venâncio DP, Oliveira MGM, Tufik S, de Mello MT (2012) Resistance exercise improves hippocampus-dependent memory. Braz J Med Biol Res 45(12):1215–1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li Z, Peng X, Xiang W, Han J, Li K The effect of resistance training on cognitive function in the older adults: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Aging Clin Exp Res 30:1259–1273. 10.1007/s40520-018-0998-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vilela TC, Muller AP, Damiani AP, Macan TP, da Silva S, Canteiro PB, de Sena Casagrande A, Pedroso GS et al. (2017) Strength and aerobic exercises improve spatial memory in aging rats through stimulating distinct neuroplasticity mechanisms. Mol Neurobiol 54(10):7928–7937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zarrinkalam E, Heidarianpour A, Salehi I, Ranjbar K, Komaki A (2016) Effects of endurance, resistance, and concurrent exercise on learning and memory after morphine withdrawal in rats. Life Sci 157:19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Abel JL, Rissman EF (2013) Running-induced epigenetic and gene expression changes in the adolescent brain. Int J Dev Neurosci 31(6):382–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ives SJ, Norton C, Miller V, Minicucci O, Robinson J, O’Brien G et al. Multi-modal exercise training and protein-pacing enhances physical performance adaptations independent of growth hormone and BDNF but may be dependent on IGF-1 in exercise-trained men. Growth Hormon IGF Res 32:60–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhong T, Ren F, Huang CS, Zou WY, Yang Y, Pan YD, Sun B, Wang E et al. (2016) Swimming exercise ameliorates neurocognitive impairment induced by neonatal exposure to isoflurane and enhances hippocampal histone acetylation in mice. Neuroscience. 316:378–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kleim JA, Lussnig E, Schwarz ER, Comery TA, Greenough WT (1996) Synaptogenesis and FOS expression in the motor cortex of the adult rat after motor skill learning. J Neurosci 16(14):4529–4535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Garcia PC, Real CC, Ferreira AFB, Alouche SR, Britto LRG, Pires RS (2012) Different protocols of physical exercise produce different effects on synaptic and structural proteins in motor areas of the rat brain. Brain Res 1456:36–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cechinel LR, Basso CG, Bertoldi K, Schallenberger B, de Meireles LCF, Siqueira IR (2016) Treadmill exercise induces age and protocol-dependent epigenetic changes in prefrontal cortex of Wistar rats. Behav Brain Res 313:82–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.