Abstract

The following fictional case is intended as a learning tool within the Pathology Competencies for Medical Education (PCME), a set of national standards for teaching pathology. These are divided into three basic competencies: Disease Mechanisms and Processes, Organ System Pathology, and Diagnostic Medicine and Therapeutic Pathology. For additional information, and a full list of learning objectives for all three competencies, see http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2374289517715040.1

Keywords: pathology competencies, organ system pathology, nervous system, central nervous system infection, neonatal meningitis, group B streptococcus, cerebrospinal fluid

Primary Objective

Objective NSC2.1: Infections of the CNS. Compare and contrast the clinical, gross, and microscopic manifestations of common bacterial, viral, and fungal infections of the central nervous system.

Competency 2: Organ System Pathology; Topic: Nervous System—Central nervous system (NSC); Learning Goal 2: Infection.

Secondary Objectives

Objective FECT2.6: Tissue Response to Bacterial Infection. Describe the histologic patterns of tissue response to bacterial infection as a function of differences in the organisms involved, the specific organ affected, and the manner by which the bacterium enters the organ.

Competency 1: Disease Mechanisms and Processes; Topic: Infectious Mechanisms (FECT); Learning Goal 2: Pathogenic Mechanisms of Infection.

Patient Presentation

A 3-week-old female infant was brought to the emergency department by her mother for nonbilious and nonbloody vomiting along with decreased appetite, decreased urine output, increased fussiness, and subjective fever. The infant had been born at 37 6/7 weeks’ gestational age by normal spontaneous vaginal delivery with no complications, to a mother with unknown group B streptococcus (GBS) status. The child had been doing well until 2 days prior when she began vomiting with every feed. This progressively worsened, prompting her mother to have her evaluated emergently at 3 weeks of life. Her mother reported nonbilious and nonbloody vomiting, decreased appetite, decreased urine output, increased fussiness, and subjective fever in the infant. On physical examination, she was febrile to 102°F, hypotensive, tachypneic, and tachycardic. She had a weak cry and appeared ill and in distress. Capillary refill was 3 to 5 seconds and skin turgor was decreased. The rest of the examination was unremarkable.

Diagnostic Findings, Part 1

Respiratory syncytial virus and influenza A/B antigen tests, urine dipstick, urine culture, and blood cultures were obtained and were all negative. Ultrasound of the head was normal with no evidence of hydrocephalus or mass effect.

Questions/Discussion Points, Part 1

What Is a Broad Differential Diagnosis for This Case?

When an infant less than 1 month of age presents with the symptoms described above, meningitis should always be considered. Infectious agents that can cause this neonatal presentation include GBS, Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, Streptococcus pneumoniae; viruses: herpes simplex virus (HSV), enterovirus, cytomegalovirus (CMV); fungi: Candida, Cryptococcus; and parasites: Toxoplasma. Noninfectious causes of this patient’s symptoms could include dehydration, neonatal abstinence syndrome, hypothyroidism, respiratory distress syndrome, drug reactions, postvaccination complications, and any central nervous system insult.2

What Work Up Should Be Performed to Elucidate the Etiology of This Patient’s Illness?

A thorough infant and maternal history should be taken. Maternal history should include inquiry about GBS infections in prior pregnancies, her current GBS status, travel/exposure history, recent antibiotic use, history of sexually transmitted infections (such as HIV, HSV, gonorrhea, and Chlamydia) during pregnancy, and birth history. A history of the infant should include questions regarding changes in behavior (lethargy, decreased urine output, increased fussiness, changes in sleep habits, poor feeding, etc), rhinorrhea, cough, vomiting, changes in breathing or wheezing, blood in stool or mucus, diarrhea, and new rashes.3

First-line laboratory tests should include cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, CSF culture, blood culture, HIV screen and enterovirus, CMV, and HSV blood polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Cerebrospinal fluid analysis should include cell count with differential, Gram stain, glucose level, and protein level, which can help differentiate bacterial, fungal, and viral causes.4 For bacterial infections, one would expect CSF analysis to show decreased glucose levels (less than 40% of the serum glucose), elevated levels of protein (100-500 mg/dL), and an elevated white blood cell count (200-100 000 per mL) with a predominance of neutrophils. Fungal infections demonstrate decreased glucose levels (less than 40% serum glucose), elevated levels of protein (100-500 mg/dL), and an elevated white blood cell count (200-100 000 per mL) with a predominance of lymphocytes. Viral causes tend to demonstrate decreased glucose levels (less than 40% of serum glucose), normal to slightly elevated protein (50-100 mg/dL), and a normal to slightly elevated white blood cell count (25-1000/mL) with a predominance of lymphocytes. Imaging studies of the head may be helpful if the causative agent manifests with brain calcifications.5

Diagnostic Findings, Part 2

A lumbar puncture was performed and results of the CSF analysis are shown in Table 1. Microscopic analysis of CSF is shown in Figure 1. Both HSV PCR of the blood and CSF were negative.

Table 1.

Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis of Our Patient and Analysis Seen in Bacterial, Fungal, and Viral Causes of Meningitis.

| Reference Range | Our Patient’s CSF Analysis | Bacterial Meningitis | Fungal Meningitis | Viral Meningitis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cell count | <5 cells/µL | 290 cells/µL (89% neutrophils) | Elevated; mostly neutrophils | Elevated; mostly lymphocytes | Normal to slightly elevated; mostly lymphocytes |

| Glucose | 40-70 mg/dL | <35 mg/dL | Very low | Very low | Low |

| Protein | 15-45 mg/dL | 273 mg/dL | Very elevated | Very elevated | Normal to slightly elevated |

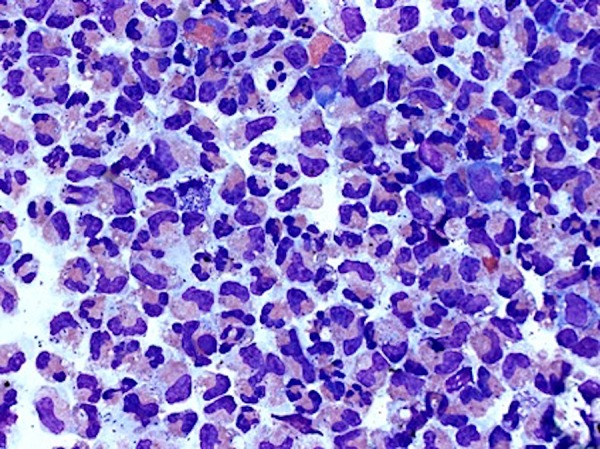

Figure 1.

Wright stain (×500) of cerebrospinal fluid specimen illustrating predominance of neutrophils with numerous cocci in pairs.

Questions/Discussion Points, Part 2

What Are the Pertinent Histologic Findings Seen in Bacterial, Fungal, and Viral Meningitis?

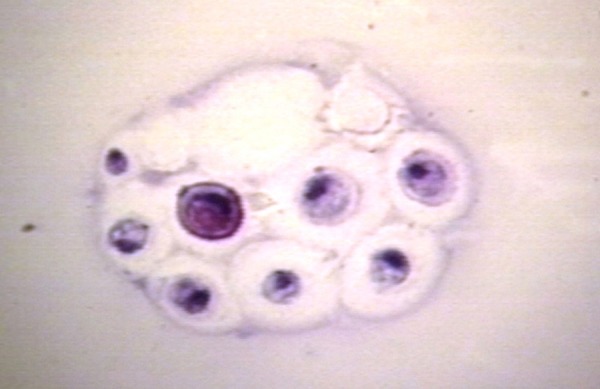

An acute inflammatory process was evidenced by the abundance of segmented neutrophils, bands, and monocytes. There are numerous bacteria (cocci in pairs) that are predominantly intracellular. Scattered eosinophils are also present. All of these findings are seen in Figure 1. As seen in Figure 2, viral meningitis will demonstrate marked lymphocytosis with the absence of any organisms. Fungal organisms will also demonstrate an abundance of lymphocytes but you will also see the organisms, for example, in Figure 3, a case of cryptococcus, you can see the thick-walled capsule yeast form.

Figure 2.

An example of cerebrospinal fluid histology in viral meningitis, where you would see lymphocytosis, which is an abundance of lymphocytes. Reproduced with permission from Dr Peter G. Anderson and the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Pathology Education Information Resource (PEIR) Digital Library.

Figure 3.

An example of cerebrospinal fluid histology in fungal meningitis. Seen here is a case of cryptococcus meningitis. Cryptococcus yeast form thick capsules, which is illustrated here, and in some cases, narrow-based budding can be seen. Reproduced with permission from Dr Peter G. Anderson and the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Pathology Education Information Resource (PEIR) Digital Library.

What Is Your Diagnosis?

Based on the clinical information, it is evident that the infant is acutely ill and there is increased concern for sepsis. Laboratory data are helpful in identifying a source for the sepsis. The abnormal CSF analysis with a very low glucose and increased white blood cell count with 89% neutrophils points toward a bacterial cause. Again, if this were due to a viral agent, then we would expect the glucose to be minimally decreased with 80% to 90% lymphocytes and moderately elevated protein levels. A Gram stain revealed numerous gram-positive cocci in pairs and CSF culture confirmed GBS infection. Given the clinical presentation of the infant, the mother’s unknown GBS status, and the CSF analysis exhibiting a bacterial pattern with gram-positive cocci in pairs that were identified as GBS by culture, the diagnosis is GBS meningitis.

What Are the Risk Factors for Neonatal Meningitis, Particularly in This Infant?

Risk factors for neonatal meningitis include age less than 28 days, temperature greater than 101.5°F, and low birth weight.6,7 Other fetal factors that can increase the risk of neonatal meningitis include prematurity, asphyxia, and multiple gestations, that is, triplets.7 Maternal factors such as premature rupture of membranes, asymptomatic bacteriuria, and vaginitis are also associated with neonatal meningitis. Of the above risk factors, the infant in this case had an age less than 28 days, was febrile above 101.5°F, and was premature. Other potential risk factors include an unimmunized mother, intrapartum maternal fever, congenital or chromosomal abnormalities, and recent antibiotic use, which may mask symptoms.8

What Characteristics of Group B Streptococcus Led to This Infant’s Presentation?

Group B streptococcus is the only bacterium in the Lancefield group B; it has a carbohydrate-associated cell wall that sets it apart from other streptococcal species. Its capsule, made up by complex polysaccharides, helps inhibit host complement components access. Residues of this capsule will also bind to neutrophils, which impairs neutrophil function and response.9 Group B streptococcus also produces invasion-associated gene A, which aids in crossing the blood–brain barrier and thereby contributes to its virulence.7 Certain strains of GBS that produce a particular surface protein, hypervirulent GBS adhesion, have been strongly associated with neonatal meningitis and subsequent sepsis.10,11

What Is the Management of GBS Meningitis in Infants?

Treatment of infants with suspected meningitis includes empirical therapy with ampicillin, cefotaxime, and an aminoglycoside; which is done before cultures are obtained. Once the source of the infection has been identified, targeted antibiotic therapy is utilized. For GBS, high-dose intravenous (IV) penicillin and an aminoglycoside are used and lumbar puncture with culture is repeated at the 24- to 48-hour mark, if positive a cerebral ultrasound or computed tomography is obtained, if negative no additional imaging is needed and the aminoglycoside can be discontinued once the patient is hemodynamically stable. High-dose IV penicillin is continued for 2 weeks after the CSF is negative for bacteria. Supportive care is also a mainstay of treatment, which includes IV fluids, electrolyte replacement, and ventilation, if necessary.

Teaching Points

A complete obstetric and birth history can guide the differential diagnoses and help direct testing.

Evaluation of febrile neonates should include workup for meningitis (parasites, bacteria, and viruses) and noninfectious causes that could present with similar symptoms.

Analysis of CSF should include chemistry, microbiology, and microscopy, which provide a complete laboratory workup for possible infectious causes of neonatal sepsis. This aids to distinguish between bacterial fungal and viral causes of meningitis.

Risk factors for neonatal meningitis include premature rupture of membranes, low birth weight, multiple gestation, asphyxia, maternal asymptomatic bacteriuria, maternal vaginitis, prolonged rupture of membranes, intrapartum maternal fever, prior pregnancies complicated by GBS infection, prematurity, age younger than 28 days, temperature greater than 101.5°F, and other comorbid congenital or chromosomal abnormalities.

Group B streptococcus has a variety of cell wall and capsular factors that contribute to its virulence and its ability to cross the blood–brain barrier.

Management of a neonate with GBS meningitis includes supportive care with fluids, electrolyte replacement, and ventilation when needed along with an antibiotic regimen that includes high-dose IV penicillin along with an aminoglycoside until the CSF is sterile. Once sterile, IV penicillin is continued for 2 weeks.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The article processing fee for this article was funded by an Open Access Award given by the Society of ‘67, which supports the mission of the Association of Pathology Chairs to produce the next generation of outstanding investigators and educational scholars in the field of pathology. This award helps to promote the publication of high-quality original scholarship in Academic Pathology by authors at an early stage of academic development.

ORCID iD: Stacy G. Beal  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0862-4240

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0862-4240

References

- 1. Knollmann-Ritschel BEC, Regula DP, Borowitz MJ, Conran R, Prystowsky MB. Pathology competencies for medical education and educational cases. Acad Pathol. 2017;4 doi:10.1177/2374289517715040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nizet V, Jerome KO. Bacterial sepsis and meningitis In: Remington JS, Klein JO, Wilson CB, Nizet V, Maldonado YA, eds. Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant. 7th ed Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders; 2011:222–275. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Avner JR, Baker MD, Bell LM. Failure of infant observation scales in detecting serious illness in febrile, 4- to 8-week-old infants. Pediatrics. 1990;85:1040–1043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Danis PG, Gardner TD, Norris CM. Aseptic meningitis in the newborn and young infant. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:2761–2770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feigin RD, Klein JO, McCracken GH. Report of the Task Force on Diagnosis and Management of Meningitis. Pediatrics. 1986;78:959–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mahajan PV, Powell EC, Roosevelt G, et al. Epidemiology of bacteremia in febrile infants aged 60 days and younger. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71:211–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Afsharkhas L, Khalessi N. Neonatal meningitis: risk factors, causes, and neurologic complications. Iran J Child Neurol. 2014;8:46–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hui C, Neto G, Tsertsvadze A, et al. Diagnosis and management of febrile infants (0-3 months). Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2012;(205):1–297. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carlin AF, Chang YC, Nizet V, Uchiyama S, Lewis AL, Varki A. Molecular mimicry of host sialylated glycans allows a bacterial pathogen to engage neutrophil Siglec-9 and dampen the innate immune response. Blood. 2009;113:3333–3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Doran KS, Engelson EJ, Khosravi A, et al. Blood-brain barrier invasion by group B Streptococcus depends upon proper cell-surface anchoring of lipoteichoic acid. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2499–2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bellais S, Disson O, Tazi A, et al. The surface protein HvgA mediates group B streptococcus hypervirulence and meningeal tropism in neonates. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2313–2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]