Abstract

Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) has shown a number of biologically beneficial effects, including prevention of obesity. The purpose of this study was to test effects of dietary supplementation of 0.5% trans-10,cis-12 CLA in a high fat diet in neuronal basic helix-loop-helix 2 knock-out animals (N2KO), which is a unique animal model representing adult-on-set inactivity-related obesity. Eight wild-type (WT) and eight N2KO female mice were fed either 0.5% trans-10,cis-12 CLA-containing diet or control diet (with 20% soybean oil diet) for 12 weeks. Body weights, food intake, adipose tissue weights, body compositions, and blood parameters were analyzed. Overall, N2KO animals had greater body weights, food intake, adi-pose tissue weights, and body fat compared to WT animals. CLA supplementation decreased overall body weights and total fat, and the effect of dietary CLA on adipose tissue reduction was greater in N2KO than in WT mice. Serum leptin and triglyc-eride levels were reduced by CLA in both N2KO and WT animals compared to control animals, while there was no effect by CLA on serum cholesterol. The effect of CLA to lower fat mass, increase lean body mass, and lower serum leptin and triglyc-erides in sedentary mice supports the possibility of using CLA to prevent or alleviate ailments associated with obesity.

Keywords: adipose tissue, CLA (conjugated linoleic acid), leptin, Nhlh2 knockout mice

Introduction

Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) has received consid-erable attention due to potentially beneficial health ben-efits such as prevention of cancer and cardiovascular dis-eases, modulation of immune and inflammatory responses, growth promotion in young animals, and, most importantly, reduction of body fat while improving lean body mass.1,2 One explanation for the variety of biological activities of this relatively simple structured fatty acid is that CLA is a mixture of isomers. Two main isomers are the cis-9,trans-11 and trans-10,cis-12 isomers. The cis-9,trans-11 CLA iso-mer is the main isomer of CLA present in food, which orig-inates from biohydrogenation of linoleic acid to stearic acid by rumen bacteria or from Δ9 desaturation of trans-11 vaccenic acid.3,4 The trans-10,cis-12 isomer is also present in beef or dairy foods but to a minor extent.5,6 It has been proven that both isomers are equally effective with regard to anticancer activity in certain cancer models.7–9 Beyond anticancer effects, these two isomers have shown distinctive activities. The trans-10,cis-12 isomer of CLA is responsi-ble for body compositional changes, inhibition of stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase activity, protein, and/or mRNA, and reduction of apolipoprotein B secretion from cultured hu-man hepatoma cells.10–12 The cis-9,trans-11 isomer is re-sponsible for growth promotion in rodents and improving lipoprotein profiles and is more effective in inhibition of tu-mor necrosis factor- (TNF- ) than the trans-10,cis-12 iso-mer.13–15 There are also instances where the two isomers appear to act in opposition.16 Hence, the many physiologi-cal effects that are reported for CLA appear to be the result of multiple interactions of these two biologically active CLA isomers.1,17

Most reported effects of CLA on body fat reduction are tested using normal animal models with few excep-tions.1,18–23 Thus the purpose of this study is to test trans-10,cis-12 CLA on body fat modulation and lipid metabo-lism using neuronal basic helix-loop-helix 2 knockout (N2KO) mice. N2KO animals display normal weight until animals reach 10–12 weeks of age, although onset of inac-tivity causes weight gain and slight overeating.24,25 This is a unique animal model that can represent adult-onset obe-sity. We tested CLA in these animals to compare its effec-tiveness on reducing body weight and fat in a genetically obese animal compared to wild-type (WT) animals.

Materials and Methods

Animal and experimental diet

All CLA preparations were provided by Natural Lipids Ltd. AS (Hovdebygda, Norway). The CLA contained 94.4% trans-10,cis-12 CLA, 2.0% cis-9,trans-11 CLA, 2.9% other CLA isomers, 0.4% oleic acid, and 0.1% linoleic acid. Twenty-month-old female N2KO mice26 and WT mice (129Sv/J) were obtained from breeding colonies maintained at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Semipurified powdered diet (TD 05350, 95% basal mix) was purchased from Harlan Teklad (Madison, WI). Animals were housed in wire-bottomed individual cages in a windowless room on a 12-hour light/dark cycle, under a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Uni-versity of Massachusetts Amherst. The diet composition is shown in Table 1. Diet and water were provided ad libitum throughout the experiment. Fresh diet was provided three times a week. After 1 week for adaptation, eight N2KO and eight WT animals were randomly divided into two groups and fed either CLA diet (0.5% trans-10,cis-12 CLA) or con-trol diet for 12 weeks. Body weight and food intake were monitored weekly.

TABLE 1.

Formulation Of Experimental Diet

| Ingredient | g/kg |

|---|---|

| Casein, “vitamin-free” test | 229 |

| L-Cystine | 3 |

| Sucrose | 100 |

| Cornstarch | 228.96 |

| Maltodextrin | 132 |

| Cellulose | 50 |

| Soybean oil | 195 |

| trans-10, cis-12 CLA or soybean oil | 5 |

| Mineral Mix, AIN-93G-MX (TD 94046) | 42 |

| Vitamin Mix, AIN-93-VX (TD 94074) | 12 |

| Choline bitartrate | 3 |

| tert-Butylhydroquinone (antioxidant) | 0.04 |

| Total | 1,000 |

Body composition

At the end of study, the mice were sacrificed by CO2 as-phyxiation. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture. The liver and adipose tissues were weighed. Carcasses were freeze-dried to obtain water content and then ground and stored in air-tight containers at 20°C. Total protein con-tent was determined by the Kjeldahl method using the Kjel-tec system (Foss North America, Eden Prairie, MN).27 To-tal lipids were determined by the Soxhlet extraction method using diethyl ether with the Soxtec System (Foss North America). Ash was determined by the gravitational method after incineration of the dried sample at 550–600°C overnight.

Serum leptin, triglyceride, cholesterol, and glucose

Serum was obtained by centrifugation at 3,000 g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Serum leptin was measured by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (R&D Systems, Inc., Min-neapolis, MN) as specified by the manufacturer. Serum triglyceride, cholesterol, and glucose were measured by en-zymatic assay kits (Thermo Electron, Inc., Louisville, CO) as specified by the manufacturer.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± SE values (n = 3–4) and analyzed using SAS software version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) by the generalized linear model procedure and least square means options. Two-way analysis of variance (genotypes vs. CLA) was performed on data in tables and figures. Repeated-measure analysis was performed for data in Figure 1. Significance was defined at P < .05.

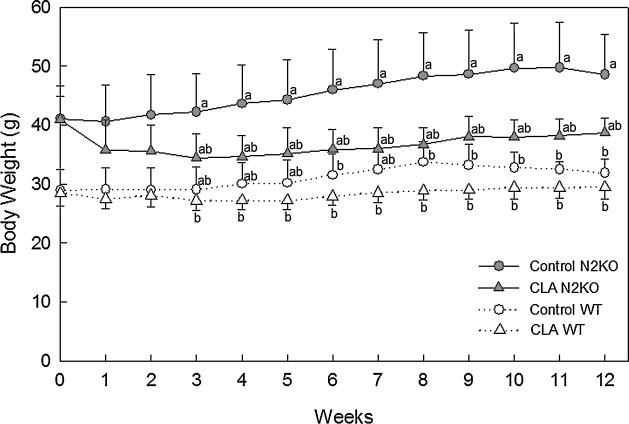

FIG. 1.

Effect of trans-10,cis-12 CLA on body weight in mice fed high fat diet. Female mice were fed either con-trol or 0.5% CLA-containing diet for 12 weeks. Data are mean SE values (n = 3–4). Means with different letters at the same time point are significantly different at P < .05.

Results

Body weight

Figure 1 shows body weight. The N2KO mice had greater body weights (41.1 ± 4.6 g) compared to the WT mice (28.9 3.6 g) at the beginning of the study and throughout the feeding period (overall effect of genotype, P .05 for weeks 0, 3, and 4–12 and P = .065 and .071 for weeks 1 and 2, respectively). Body weights of CLA-fed WT mice were not different from those of control WT animals at all time points. The CLA-supplemented N2KO mice showed lower body weights starting at week 1, and this trend was maintained throughout the study (P = .0431 with repeated-measure analysis). The effect of CLA on body weight was more pronounced in the N2KO mice compared to the WT animals, about 20% weight reduction over the 12-week pe-riod. There was no interaction between CLA and animal strains.

Food intake

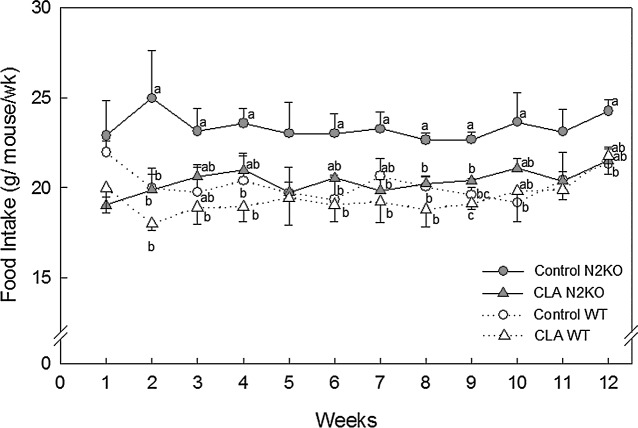

Figure 2 shows food intake. As previously reported,24 N2KO mice show a slight hyperplasia as compared to WT animals, with significance at weeks 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, and 10 (overall effect of genotype). The feed intakes be-tween the WT treatment groups (control vs. CLA) were not significantly different. However, CLA-supplemented N2KO animals consumed less food compared to control N2KO animals (significant at weeks 2, 7, 8, and 9, P < .05) (Fig. 2). No interaction was observed between CLA and animal strains at all time points except at week 9 (P = .0286).

FIG. 2.

Effect of trans-10,cis-12 CLA on food intake in mice fed high fat diet. Female mice were fed either con-trol or 0.5% CLA-containing diet for 12 weeks. Data are mean SE values (n = 3–4). Means with different let-ters at the same time point are significantly different at P < 05.

Body composition

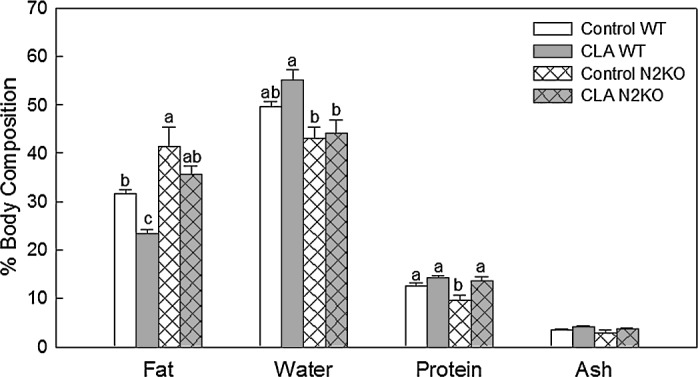

Figure 3 shows the body composition results for water, fat, protein, and ash contents as percentages of empty car-cass weights. The total fat content of the N2KO mice was greater than those of the WT animals regardless of treat-ment. Overall, CLA supplementation reduced body fat in both the N2KO and WT mice, although body fat reduction in CLA-treated WT animals reached statistical significance. The water and protein contents expressed as a percentage of the control were lower in N2KO mice (significant for pro-tein) than in control WT animals. There were no significant effects by CLA supplementation in total water content, while percentage protein content of the CLA-fed knockout mice was significantly higher compared to the N2KO control. There was no difference in total ash content in all treatments. There was no significant interaction between CLA and an-imal strains.

FIG. 3.

Effect of trans-10,cis-12 CLA on body composition in mice fed high fat diet. Female mice were fed either control or 0.5% CLA-containing diet for 12 weeks. Data are mean SE values (n = 3–4). Means with different letters within each variable are significantly dif-ferent at P < .05.

Tissue weight

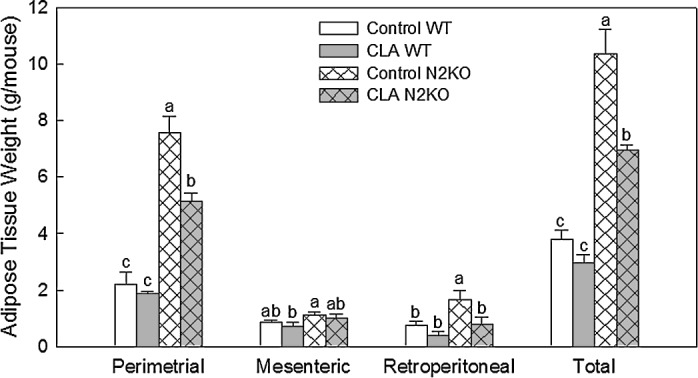

Figure 4 shows adipose tissue weight: perimetrial, retroperitoneal, and mesenteric adipose tissues and total as the sum of these adipose tissues. N2KO animals had sig-nificantly greater adipose tissue weights overall compared to WT mice in all adipose tissues tested. There were sig-nificant CLA treatment effects for perimetrial, retroperi-toneal, and total adipose tissue weights but not mesenteric adipose tissues. The reduction in total adipose tissue weight by CLA was greater in the N2KO mice (33% reduction) than in the WT animals (23% reduction). For the liver, CLA feed-ing significantly increased liver weight in both strains of an-imals compared to control (as a percentage of body weight: 2.82 ± 0.28 for control WT, 4.43 ± 0.25 for CLA WT, 2.65 ± 0.28 for control N2KO, and 4.43 ± 0.52 for CLA N2KO).

FIG. 4.

Effect of trans-10,cis-12 CLA on adipose tissue weight in mice fed high fat diet. Female mice were fed either control or 0.5% CLA-containing diet for 12 weeks. Data are mean SE values (n = 3–4). Means with different letters within each variable are signifi-cantly different at P < .05.

Serum leptin, triglyceride, cholesterol, and glucose

Table 2 summarizes the effects of CLA on selected serum parameters in these animals. Serum leptin levels were sig-nificantly increased in N2KO mice compared to WT con-trol animals as previously reported.28 CLA feeding reduced serum leptin levels in both strains: P < .01 for N2KO strain and P = .063 for WT animalss, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Effect of Dietary Trans-10, Cis-12 CLA On Blood Parameters in Mice

| Blood parameter | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Leptin (ng/mL) | Triglyceride (mg/dL) | Cholesterol (mg/dL) | Glucose (mg/dL) |

| Cont-WT | 52.6 ± 2.9c | 126.3±7.1a | 151.6±7.8 | 61.8±2.5 |

| CLA-WT | 37.9 ± 2.3c | 72.9±6.4b | 150.8±30.0 | 60.0 ± 0.6 |

| Cont-N2KO | 115.9 ± 8.0a | 141.4±21.7a | 149.5±4.6 | 60.7±4.1 |

| CLA-N2KO | 81.5 ± 4.1b | 61.1±7.1b | 150.8±22.0 | 58.3 ± 3.5 |

Cont-WT, control WT mice; CLA-WT, 0.5% CLA-fed WT mice; Cont-N2KO, control Nhlh-2 KO mice; CLA-N2KO, 0.5% CLA-fed Nhlh-2 KO mice. Data are mean SE values (n = 3–4).

Means with different superscript in the same column are significantly different at P < .05.

Serum triglyceride levels were not different between the two strains of mice. However, CLA-fed animals had signif-icantly lowered serum triacylglyceride (TG) regardless of strain compared to controls. There were no differences in serum cholesterol and glucose by strain or with the trans-10,cis-12 CLA treatment.

Discussion

CLA has been shown to reduce body fat in a number of animal studies. Most studies published used normal healthy young animals with limited data using relatively old or ge-netically modified animals.1,18–23 This is the first report showing that CLA reduced body fat in an adult-onset obese mouse model with relatively aged animals (average, 20 months old). In addition, these data are the first to use a mouse model where obesity is mainly caused by reduced physical activity and not because of overt hyperplasia. The N2KO mice model represents the human condition of adult-onset obesity caused by mild overeating and a sedentary lifestyle. CLA supplementation was able to reduce weight gain as well as body fat in this animal model, which sup-ports previous observations that CLA can reduce body fat in relatively old as well as young animals.29 Moreover, by using old animals we were able to observe CLA's effect on improved total protein, which can have a significant health impact in the elderly population.

Reduced food intake by CLA feeding has been observed but not consistently (present study).11,30–33 We have previ-ously suggested that the feed intake reduction by CLA may be in part due to the decreased palatability of free fatty acid compared to the TG form, supported by the fact that this is only observed in the early CLA feeding period (authors' un-published data).1 However, CLA-fed N2KO animals had less food intake throughout the experimental period com-pared to N2KO control animals in this experiment. Total food consumption, reported as g of food intake per mouse for 12 weeks, for control N2KO mice was 280.1 12.5 g compared to 247.6 6.6 g in CLA-fed N2KO animals. Dur-ing this period, control N2KO mice gained 7.5 g, while CLA-fed N2KO mice lost 2.2 g. Meanwhile, total food in-take for control WT animals was 244.0 3.9 g, which is similar to total food intake by CLA-fed N2KO animals (247.6 6.6 g). However, control WT animals gained 2.9 g, while again CLA-fed N2KO animals lost 2.2 g. This clearly indicates that with the similar food consumption, CLA feeding was able to prevent weight gain in this animal model. This observation is consistent with a previous report that CLA-fed animals lost more body fat than pair-fed ani-mals, which suggested that reduced food intake may not be the major mechanism of action for CLA on body fat con-trol.29

Beyond food intake modulation by CLA, the reduced body fat or weight gain by CLA, either by reduced fat ac-cumulation or by reduced existing fat, may involve mul-tiple mechanisms: increasing energy expenditure, modu-lating adipocyte metabolism, and/or increasing fatty acid -oxidation in skeletal muscle.1,34,35 While N2KO mice have known reduction in total energy expenditure via physical activity levels, levels of oxygen consumption during rest or activity have not yet been measured in this model. With the effective body fat reduction in this mouse model, it is potentially possible that CLA may increase energy expenditure by modulating activity levels. Alter-natively, trends of increased protein imply that CLA may affect activity levels to prevent muscle loss associated with inactivity, particularly in the elderly. In addition, when percentage fat and adipose weights were compared, CLA showed greater reduction of white adipose tissue weight, while total percentage fat was less prominent. This suggests that CLA may have a greater effect on adipose tissues in the abdominal area (peritoneal cavity) and be less effective on other adipose tissues, such as subcuta-neous fat. Thus, the exact mechanisms of CLA in N2KO mice, including energy expenditure, activity, and lipid me-tabolism, warrant further investigation.

We replicated previous findings of elevated leptin levels in N2KO compared to WT animals28 and showed that CLA decreased levels of leptin in both N2KO and WT animals. Since CLA reduces total body fat, reduced serum leptin lev-els would be expected.1,36 The reduction of serum leptin lev-els by CLA, however, did not cause any significant increase in food intake. On the contrary, CLA supplementation showed trends of reduced food intake in this study, while others have reported inconsistent effects, either no effect or reduced food intake by CLA supplementation.11,30–33 The reason for the lack of physiological response to reduced serum leptin level by CLA is not clear at this time. It is un-likely that the leptin response is modified by CLA since Tsuboyama-Kasaoka et al.36 injected leptin into CLA-fed animals and observed leptin responses from those animals. Thus, it is unlikely that CLA modulates leptin responses to affect food intake. An alternative mechanism is that CLA may involve an additional mechanism(s) involved in food intake control. Cao et al.37 recently reported that CLA de-creases expression of neuropeptides and agouti-related pro-tein in the hypothalamus, which could have downstream ef-fects on reduced food intake.

Serum TG levels were not different between N2KO and WT animals, but both strains of mice responded to CLA treatment with a significant lowering of TG levels. Even though previous reports indicated beneficial effects of CLA on serum cholesterol levels, we did not observe any effects of CLA on cholesterol in this study. Inconsistent observa-tions may be due to the difference in animal species used (mice vs. rabbits or hamsters; normal vs. hypercholes-terolemic animals) or low cholesterol-containing diets used in this study compared to high-cholesterol diets used in pre-vious publications.38–42 However, the reduced TG levels by CLA alone may suggest a potentially beneficial effect of CLA on prevention of cardiovascular diseases, particularly those linked with inactivity-induced obesity.

In this study we did not observe any difference in glu-cose levels between strains and CLA supplementation. This is important since impaired glucose tolerance is one of the main concerns regarding CLA consumption.2,43 Although the trans-10,cis-12 CLA isomer is linked with insulin re-sistance, it is interesting that the mixed isomer trans-10,cis-12 and cis-9,trans-11 CLA preparation did not cause insulin resistance.44–47 It is also noteworthy that this study used the trans-10,cis-12 CLA isomer, which is the CLA isomer re-sponsible for the glucose intolerance, and we did not ob-serve any changes in glucose levels. While it is generally accepted that reduced body fat is linked to improved glu-cose tolerance, CLA supplementation led to impaired glu-cose tolerance in mice and human studies, although not con-sistently. This may be due to increased fatty acid -oxidation by skeletal muscle, which causes glucose intolerance.48 However, with relatively long-term studies, as here with 12-week feeding compared to 4–6-week treatments used in pre-vious publications, it is possible that this impaired glucose tolerance may be a transient effect associated with increased fatty acid -oxidation by skeletal muscle and that eventu-ally the glucose tolerance may return to its normal level.49–51 In fact, several long-term clinical studies (6 months to 2 years) indicated that CLA had no effect on glucose or in-sulin levels.52–56

Enlarged liver by CLA has been reported previously, sug-gested to be mainly associated with lipid accumulation (steatosis) due to increased hepatic fatty acid synthesis along with reduced lipid deposit in extrahepatic tissues.23,36,57 However, others reported no effects by CLA on the liver or reduced hepatic steatosis in a rat model.58 O'Hagan and Menzel51 suggested this may be a temporary response of bi-ological systems to CLA, and potentially reversible. Al-though there are no pathological symptoms associated with CLA on enlarged liver, further evaluation is warranted to ensure the safety of CLA consumption.1

The results from this study suggest that CLA is able to bypass the genetic defect resulting in lower body weight and body fat in the treated knockout animals. The Nhlh2 gene is expressed in hypothalamic neurons, where it can be specif-ically induced by leptin treatment,59 and previously CLA treatment of ob/ob mice, which have an inactivated leptin gene, has also been found to lead to weight and body fat loss.23 Taken together, these data suggest that genetic de-fects in the leptin signaling pathway may be amenable to CLA treatment for body weight and body fat reduction. In humans, where up to 6% of the known single gene obesity syndromes affect the leptin–melanocortin pathway,60 these data suggest a possible treatment for genetic obesity. Fur-ther studies using other genetically obese animal models could help to characterize the mechanism of action and tar-geted cell types for CLA.

In summary, this is the first study investigating CLA us-ing an adult-onset inactivity-induced animal model of obe-sity. CLA reduced weight gain, body fat, serum leptin, and serum TG without affecting serum cholesterol and glucose. This suggests that CLA may effectively reduce weight gain and body fat in inactivity-induced obesity without signifi-cant adverse effects. Further investigations on how CLA af-fects leptin signaling and activity levels are needed to un-derstand mechanisms of action for CLA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Jayne M. Storkson for assistance with man-uscript preparation. This work was supported in part by the Department of Food Science at University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Author Disclosure Statement

Yeonhwa Park is one of the inventors of the CLA use patents that are assigned to the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation. No other competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Park Y, Pariza MW: Mechanisms of body fat modulation by conjugated linoleic acid (CLA). Food Res Int 2007;40:311–323 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pariza MW: Perspective on the safety and effectiveness of conjugated linoleic acid. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;79(Suppl): 1132S–1136S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kepler CR, Hirons KP, McNeill JJ, Tove SB: Intermediates and products of the biohydrogenation of linoleic acid by Butyrinvibrio fibrisolvens. J Biol Chem 1966;241:1350–1354 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Griinari JM, Corl BA, Lacy SH, Chouinard PY, Nurmela KV, Bauman DE: Conjugated linoleic acid is synthesized endogenously in lactating dairy cows by delta(9)-desaturase. J Nutr 2000;130:2285–2291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Park Y, Pariza MW: Evidence that commercial calf and horse sera can contain substantial amounts of trans-10,cis-12 conjugated linoleic acid. Lipids 1998;33:817–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dhiman TR, Zaman S, Olson KC, Bingham HR, Ure AL, Pariza MW: Influence of feeding soybean oil on conjugated linoleic acid content in beef. J Agric Food Chem 2005;53:684–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ip C, Dong Y, Ip MM, Banni S, Carta G, Angioni E, Murru E, Spada S, Melis MP, Saebo A: Conjugated linoleic acid isomers and mammary cancer prevention. Nutr Cancer 2002;43:52–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Masso-Welch PA, Zangani D, Ip C, Vaughan MM, Shoemaker SF, McGee SO, Ip MM: Isomers of conjugated linoleic acid differ in their effects on angiogenesis and survival of mouse mammary adipose vasculature. J Nutr 2004;134:299–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Masso-Welch PA, Zangani D, Ip C, Vaughan MM, Shoemaker S, Ramirez RA, Ip MM: Inhibition of angiogenesis by the cancer chemopreventive agent conjugated linoleic acid. Cancer Res 2002;62:4383–4389 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Park Y, Storkson JM, Ntambi JM, Cook ME, Sih CJ, Pariza MW: Inhibition of hepatic stearoyl-CoA desaturase activity by trans-10, cis-12 conjugated linoleic acid and its derivatives. Biochim Biophys Acta 2000;1486:285–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Park Y, Storkson JM, Albright KJ, Liu W, Pariza MW: Evidence that the trans-10,cis-12 isomer of conjugated linoleic acid induces body composition changes in mice. Lipids 1999;34:235–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Storkson JM, Park Y, Cook ME, Pariza MW: Effects of trans-10,cis-12 conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) and cognates on apolipoprotein B secretion in HepG2 cells. Nutr Res 2005;25:387–399 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cook ME, Miller CC, Park Y, Pariza M: Immune modulation by altered nutrient metabolism—nutritional control of immune-induced growth depression. Poult Sci 1993;72:1301–1305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Valeille K, Gripois D, Blouquit MF, Souidi M, Riottot M, Bouthegourd JC, Serougne C, Martin JC: Lipid atherogenic risk markers can be more favourably influenced by the cis-9,trans-11-octadecadienoate isomer than a conjugated linoleic acid mixture or fish oil in hamsters. Br J Nutr 2004;91:191–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yang M, Cook ME: Dietary conjugated linoleic acid decreased cachexia, macrophage tumor necrosis factor-alpha production, and modifies splenocyte cytokines production. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2003;228:51–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Song HJ, Sneddon AA, Barker PA, Bestwick C, Choe SN, Mc-Clinton S, Grant I, Rotondo D, Heys SD, Wahle KW: Conjugated linoleic acid inhibits proliferation and modulates protein kinase C isoforms in human prostate cancer cells. Nutr Cancer 2004; 49:100–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pariza MW, Park Y, Xu X, Ntambi J, Kang K: Speculation on the mechanisms of action of conjugated linoleic acid. In: Advances in Conjugated Linoleic Acid Research, Vol. 2 (Sebedio J-L, Christie WW, Adlof R, eds.). AOCS Press, Champaign, IL, 2003, pp. 251–258 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weber TE, Richert BT, Belury MA, Gu Y, Enright K, Schinckel AP: Evaluation of the effects of dietary fat, conjugated linoleic acid, and ractopamine on growth performance, pork quality, and fatty acid profiles in genetically lean gilts. J Anim Sci 2006;84: 720–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sisk MB, Hausman DB, Martin RJ, Azain MJ: Dietary conjugated linoleic acid reduces adiposity in lean but not obese Zucker rats. J Nutr 2001;131:1668–1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Arbones-Mainar JM, Navarro MA, Acin S, Guzman MA, Arnal C, Surra JC, Carnicer R, Roche HM, Osada J: Trans-10, cis-12-and cis-9, trans-11-conjugated linoleic acid isomers selectively modify HDL-apolipoprotein composition in apolipoprotein Eknockout mice. J Nutr 2006;136:353–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ohashi A, Matsushita Y, Kimura K, Miyashita K, Saito M: Conjugated linoleic acid deteriorates insulin resistance in obese/diabetic mice in association with decreased production of adiponectin and leptin. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2004;50:416–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Houseknecht KL, Vanden Heuvel JP, Moya-Camarena SY, Portocarrero CP, Peck LW, Nickel KP, Belury MA: Dietary conjugated linoleic acid normalizes impaired glucose tolerance in the Zucker diabetic fatty fa/fa rat. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998;244:678–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wendel AA, Purushotham A, Liu LF, Belury MA: Conjugated linoleic acid fails to worsen insulin resistance but induces hepatic steatosis in the presence of leptin in ob/ob mice. J Lipid Res 2008;49:98–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Coyle CA, Jing E, Hosmer T, Powers JB, Wade G, Good DJ: Reduced voluntary activity precedes adult-onset obesity in Nhlh2 knockout mice. Physiol Behav 2002;77:387–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jing E, Nillni EA, Sanchez VC, Stuart RC, Good DJ: Deletion of the Nhlh2 transcription factor decreases the levels of the anorexigenic peptides alpha melanocyte-stimulating hormone and thyrotropin-releasing hormone and implicates prohormone convertases I and II in obesity. Endocrinology 2004;145:1503–1513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Good DJ, Porter FD, Mahon KA, Parlow AF, Westphal H, Kirsch IR: Hypogonadism and obesity in mice with a targeted deletion of the Nhlh2 gene. Nat Genet 1997;15:397–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McNeal JE: Meat and meat products. In: Official Methods of Analysis, 15th ed. (Helrich K, ed.). Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Arlington, VA, 1990, pp. 935–937 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Good DJ: How tight are your genes? Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of the leptin receptor, NPY, and POMC genes. Horm Behav 2000;37:284–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Park Y, Albright KJ, Storkson JM, Liu W, Pariza MW: Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) prevents body fat accumulation and weight gain in an animal model. J Food Sci 2007;72: S612–S617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Park Y, Albright KJ, Liu W, Storkson JM, Cook ME, Pariza MW: Effect of conjugated linoleic acid on body composition in mice. Lipids 1997;32:853–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. West DB, Delany JP, Camet PM, Blohm F, Truett AA, Scimeca J: Effects of conjugated linoleic acid on body fat and energy metabolism in the mouse. Am J Physiol 1998;275:R667–R672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rahman MM, Bhattacharya A, Banu J, Fernandes G: Conjugated linoleic acid protects against age-associated bone loss in C57BL/6 female mice. J Nutr Biochem 2007;18:467–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Belury MA, Kempa-Steczko A: Conjugated linoleic acid modulates hepatic lipid composition in mice. Lipids 1997;32:199–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wahle KW, Heys SD, Rotondo D: Conjugated linoleic acids: are they beneficial or detrimental to health? Prog Lipid Res 2004; 43:553–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pariza MW, Park Y, Cook ME: The biologically active isomers of conjugated linoleic acid. Prog Lipid Res 2001;40:283–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N, Takahashi M, Tanemura K, Kim HJ, Tange T, Okuyama H, Kasai M, Ikemoto S, Ezaki O: Conjugated linoleic acid supplementation reduces adipose tissue by apoptosis and develops lipodystrophy in mice. Diabetes 2000;49: 1534–1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cao ZP, Wang F, Xiang XS, Cao R, Zhang WB, Gao SB: Intracerebroventricular administration of conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) inhibits food intake by decreasing gene expression of NPY and AgRP. Neurosci Lett 2007;418:217–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kritchevsky D, Tepper SA, Wright S, Tso P, Czarnecki SK: Influence of conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) on establishment and progression of atherosclerosis in rabbits. J Am Coll Nutr 2000;19(Suppl):472S–477S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Navarro V, Miranda J, Churruca I, Fernandez-Quintela A, Rodriguez VM, Portillo MP: Effects of trans-10,cis-12 conjugated linoleic acid on body fat and serum lipids in young and adult hamsters. J Physiol Biochem 2006;62:81–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bissonauth V, Chouinard Y, Marin J, Leblanc N, Richard D, Jacques H: The effects of t10,c12 CLA isomer compared with c9,t11 CLA isomer on lipid metabolism and body composition in hamsters. J Nutr Biochem 2006;17:597–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wilson TA, Nicolosi RJ, Saati A, Kotyla T, Kritchevsky D: Conjugated linoleic acid isomers reduce blood cholesterol levels but not aortic cholesterol accumulation in hypercholesterolemic hamsters. Lipids 2006;41:41–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gavino VC, Gavino G, Leblanc MJ, Tuchweber B: An isomeric mixture of conjugated linoleic acids but not pure cis-9, trans-11-octadecadienoic acid affects body weight gain and plasma lipids in hamsters. J Nutr 2000;130:27–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tricon S,Yaqoob P: Conjugated linoleic acid and human health: a critical evaluation of the evidence. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2006;9:105–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Riserus U, Vessby B, Arner P, Zethelius B: Supplementation with trans10cis12-conjugated linoleic acid induces hyperproinsulinaemia in obese men: close association with impaired insulin sensitivity. Diabetologia 2004;47:1016–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Riserus U, Arner P, Brismar K, Vessby B: Treatment with dietary trans10cis12 conjugated linoleic acid causes isomer-specific insulin resistance in obese men with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1516–1521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Riserus U, Vessby B, Arnlov J, Basu S: Effects of cis-9,trans-11 conjugated linoleic acid supplementation on insulin sensitivity, lipid peroxidation, and proinflammatory markers in obese men .Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80:279–283 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47. Moloney F, Yeow TP, Mullen A, Nolan JJ, Roche HM: Conjugated linoleic acid supplementation, insulin sensitivity, and lipoprotein metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80:887–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dumke CL, Gazdag AC, Fechner K, Park Y, Pariza MW, Cartee GD: Skeletal muscle glucose transport in conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) fed mice. Med Sci Sports Exercise 2000;32(Suppl): S226 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hamura M, Yamatoya H, Kudo S: Glycerides rich in conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) improve blood glucose control in diabetic C57BLKS-leprdb/leprdb mice. J Oleo Sci 2001;50: 889–894 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wargent E, Sennitt MV, Stocker C, Mayes AE, Brown L, O’-Dowd J, Wang S, Einerhand AW, Mohede I, Arch JR, Cawthorne MA: Prolonged treatment of genetically obese mice with conjugated linoleic acid improves glucose tolerance and lowers plasma insulin concentration: possible involvement of PPAR activation. Lipids Health Dis 2005;4:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. O'Hagan S, Menzel A: A subchronic 90-day oral rat toxicity study and in vitro genotoxicity studies with a conjugated linoleic acid product. Food Chem Toxicol 2003;41:1749–1760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gaullier JM, Halse J, Hoye K, Kristiansen K, Fagertun H, Vik H, Gudmundsen O: Supplementation with conjugated linoleic acid for 24 months is well tolerated by and reduces body fat mass in healthy, overweight humans. J Nutr 2005;135:778–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gaullier JM, Halse J, Hoye K, Kristiansen K, Fagertun H, Vik H, Gudmundsen O: Conjugated linoleic acid supplementation for 1 y reduces body fat mass in healthy overweight humans. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;79:1118–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Larsen TM, Toubro S, Gudmundsen O, Astrup A: Conjugated linoleic acid supplementation for 1 y does not prevent weight or body fat regain. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:606–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Whigham LD, O'Shea M, Mohede IC, Walaski HP, Atkinson RL: Safety profile of conjugated linoleic acid in a 12-month trial in obese humans. Food Chem Toxicol 2004;42:1701–1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Syvertsen C, Halse J, Hoivik HO, Gaullier JM, Nurminiemi M, Kristiansen K, Einerhand A, O'Shea M, Gudmundsen O: The effect of 6 months supplementation with conjugated linoleic acid on insulin resistance in overweight and obese. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1148–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yanagita T, Wang YM, Nagao K, Ujino Y, Inoue N: Conjugated linoleic acid-induced fatty liver can be attenuated by combination with docosahexaenoic acid in C57BL/6N mice. J Agric Food Chem 2005;53:9629–9633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Purushotham A, Shrode GE, Wendel AA, Liu LF, Belury MA: Conjugated linoleic acid does not reduce body fat but decreases hepatic steatosis in adult Wistar rats. J Nutr Biochem 2007;18: 676–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Vella KR, Burnside AS, Brennan KM, Good DJ: Expression of the hypothalamic transcription factor Nhlh2 is dependent on energy availability. J Neuroendocrinol 2007;19:499–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Farooqi IS, O'Rahilly S: Monogenic obesity in humans. Annu Rev Med 2005;56:443–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]