Abstract

There are a limited number of near-infrared (NIR) emitting (λem = 700–900 nm) molecular probes available for imaging applications. A NIR-emitting probe that exhibits emission at ~ 800 nm with large Stokes shift was synthesized and found to exhibit excellent selectivity towards mitochondria for live-cells imaging. The photophysical properties were achieved by generating an excited “cyanine structure” via intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) involving a phenol group.

Graphical Abstract

Visualization of specific organelles and organs by fluorescent agents has been the center of recent research because of their high sensitivity, low cost, and high specificity.1–3 The applications depend on the probe’s ability to target the specific organelles (or organs) without perturbation of their morphology and physiology. For example, mitochondria are double layer membrane-bound organelles which exist in eukaryotic cells and are responsible for the generation of entire cellular energy in an animal cell in the form of ATP.4–7 The function of mitochondria is dependent on the electrochemical gradient potential (Δψm) across mitochondrial membranes or electrochemical proton motive force (Δp), which is combination of mitochondrial membrane potential and mitochondrial pH gradient generated by respiratory electron transport chain (ETC).4, 7–9 Damage and dysfunction of mitochondria are associated with various diseases including aging, cancer, neurodegenerative, Alzheimer, Huntington, diabetes, and Parkinson’s disease.7, 10–12

Most of the fluorescent probes absorb and emit in the visible region, whose application is limited by high phototoxicity and interference from background fluorescence.13 NIR-emitting fluorescence probes14 are useful for bioimaging applications, as they suffer less auto-fluorescence from the biological samples and can achieve deeper tissue penetration.15 Current NIR-emitting probes include BODIPY, benzofuran, rhodamine, and cyanine as fluorophores.16, 17 However, these fluorophores have small Stokes shifts (Δλ ≈ 10 – 60 nm), which prevent optimum collection of fluorescence signal and hamper their broad applications in bioimaging.18–20 Therefore, developing fluorophores with large Stokes shifts are desirable, in order to realize the full potential of sensitive fluorescence imaging. In addition, NIR-emitting fluorescent probes with significant Stokes shifts are also useful for single excitation multicolor live-cell imaging, which plays important role in biological studies.21

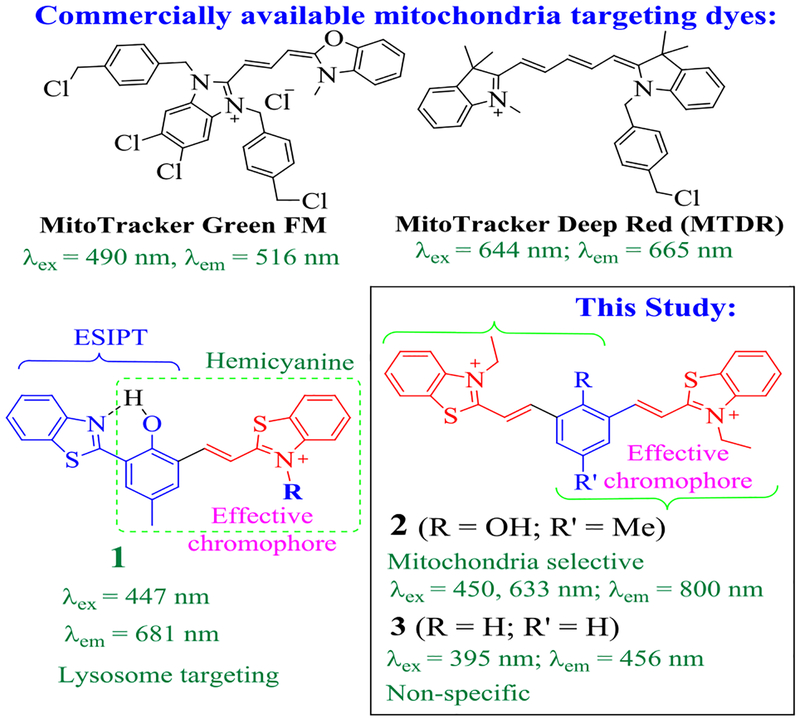

Recently, our group synthesized NIR emitting probe 1 (Figure 1), which gives NIR emission with very large Stokes’ shifts (Δλ ≈ 234 nm).22, 23 The molecular structure of 1 integrates an “excited state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT)” group with a hemicyanine unit via sharing a meta-phenylene bridge. Interestingly, probe 1 exhibits excellent selectivity toward intracellular lysosomes, due to its low pKa (=5.72) of phenolic proton and ability to give a large fluorescence turn on in an acidic environment (ArO− + H+ → ArOH).22 It should be noted that the effective chromophores in 1 can be approximated by hemicyanine and ESIPT fragments, due to π-conjugation interruption by a meta-phenylene bridge.24 In an effort to further examine the structural impact on the fluorescence property, herein, we illustrate the synthesis of 2, in which the effective chromophore is nearly the same as that in 1. In probe 2, the phenolic proton can dissociate but does not undergo any intramolecular proton transfer reaction. Interestingly, probe 2 exhibits NIR emission (λem ≈ 800 nm) with a very large Stokes shift (e.g. Δλ ≈ 161 nm), in sharp contrast to conventional cyanine dyes (Δλ ≈ 10 – 60 nm). Although the phenolic proton of 2 is acidic (pKa ≈ 4), probe 2 exhibits remarkable selectivity toward mitochondria when used to stain biological cells.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of probes 1-3 and some commercial mitochondria staining dyes.

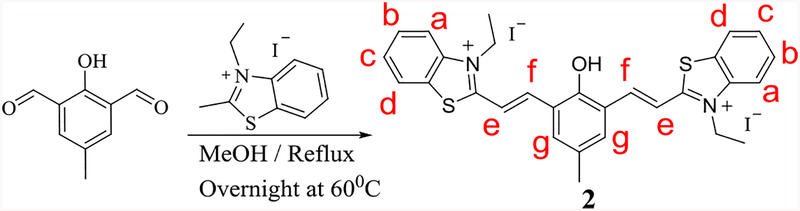

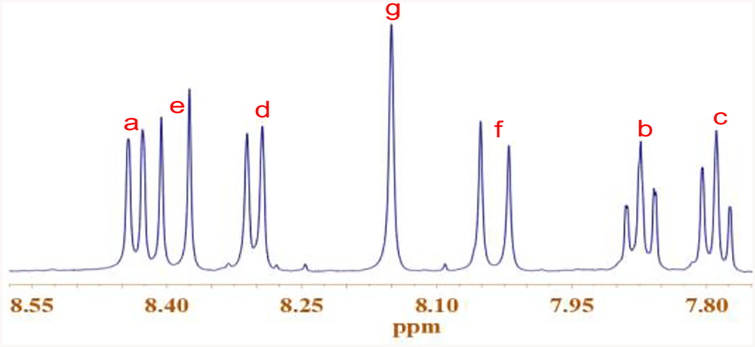

The desired compound 2 was synthesized by the reaction of 2-hydroxy-5-methylisophthalaldehyde (dialdehyde) with 1-ethyl-2-methylbenzothiazolium salt in 75% yield (Scheme 1) and was characterized by NMR and mass spectrometry. 1H NMR of 2 gave sharp doublet signals at 8.0 and 8.4 ppm, which were attributed to newly formed vinyl bond (Figure 2). The high-resolution mass spectrum revealed m/e 483.1119 that was the deprotonated state of 2 without counter ions (ESI Figure S4); Calcd. for 483.1553. Compound 3 (m/z 454.1500, ESI Figure S7; Calcd for 454.1526) was also synthesized to aid the spectral study.

Scheme 1:

Synthesis of compound 2.

Figure 2.

1H NMR of 2 in DMSO-d6, showing the resonance signals of aromatic protons (the alkyl region is omitted for clarity).

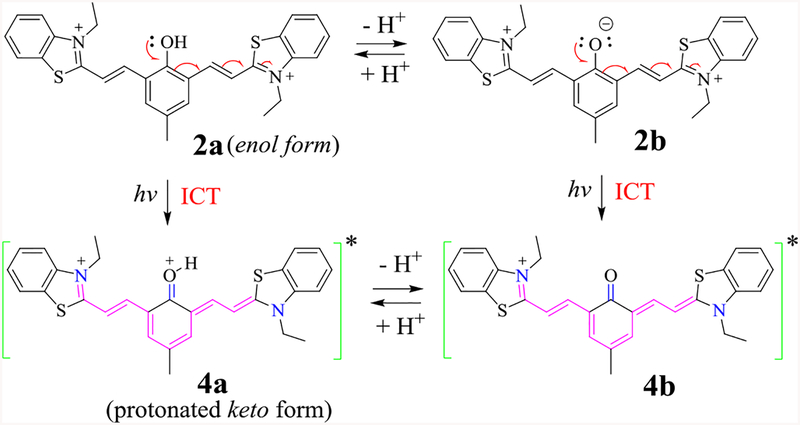

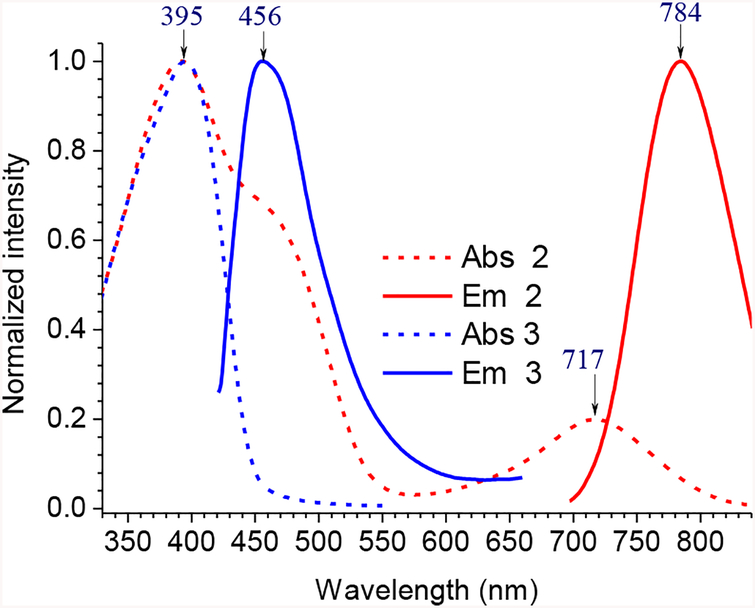

UV-vis absorption spectra 2 revealed the absorption peaks at λabs ≈ 395 and a broad shoulder at 456 nm, similar to that observed from 1 due to the presence of identical effective chromophore in 1 and 2.22 However, a new absorption peak λmax≈ 717 nm was observed from 2. The absorption bands at λabs≈395 and 456 nm were attributed to the enol form (or acid form) 2a, while the band at 717 nm to its base form 2b (Scheme 2). Since only one set of resonance signals (e.g. for Hb and Hc) was observed in the 1H NMR, compound 2 was assumed to be present predominantly in its enol form 2a in a polar aprotic solvent.

Scheme 2.

The proposed transformation of excited 2 to its keto form 4, and their equilibrium via proton dissociation.

Interestingly, the emission of 2 showed λem≈ 784 nm (Figure 3 and Table 1). The results indicated a strong synergistic interaction between the two hemicyanine substituents in 2, since the λem value of 2 were significantly red-shifted from that of 1 (λem≈ 681 nm).22 The observed spectral red-shift was apparently dependent on the presence of the –OH group between the substituents, as the NIR emission band was not observed from the model compound 3 (λabs =395 nm and λem = 456 nm; ESI Figures S12 and S13).

Figure 3.

UV-vis absorption (broken line) and emission spectra (solid line) of 2 and 3 in CH2Cl2. The excitation wavelengths were 687 nm for 2 and 395 nm for 3.

Table 1.

Photophysical properties of compounds 2 and 3 in different solvents

| Solvents | Compound 2 | Compound 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λabs | λem | (Φfl) | λabs | λem | (Φfl) | |

| DCM | 392, 456, 717 | 784 | 0.11 | 395 | 456 | 0.004 |

| DMF | 388, 489, 728 | 803 | 0.04 | 383 | 470 | 0.002 |

| DMSO | 388, 728 | 803 | 0.04 | 387 | 467 | 0.002 |

| EtOH | 385, 654 | 798 | 0.03 | 384 | 460 | 0.002 |

| MeCN | 382, 702 | 795 | 0.04 | 382 | 460 | 0.002 |

| MeOH | 382, 633 | 794 | 0.02 | 383 | 460 | 0.002 |

| Water | 382, 589 | 770 | 0.01 | 380 | 460 | 0.002 |

Examination of 2 in different solvents revealed that its NIR absorption peak was affected by solvent polarity (λabs=728 nm in DMSO, but 589 nm in aqueous) (Table 1, and ESI Figure S8). However, the emission wavelength of 2 was less affected (λem=770–804 nm) (ESI Figure S9). DFT calculation with TD-SCF method revealed that the keto tautomer of 2 in CH2Cl2 had absorption (λabs = 714 nm) and emission (λem= 780 nm) (ESI Figure S10), which closely matched the experimental values (λabs = 717 nm, λem= 784 nm).

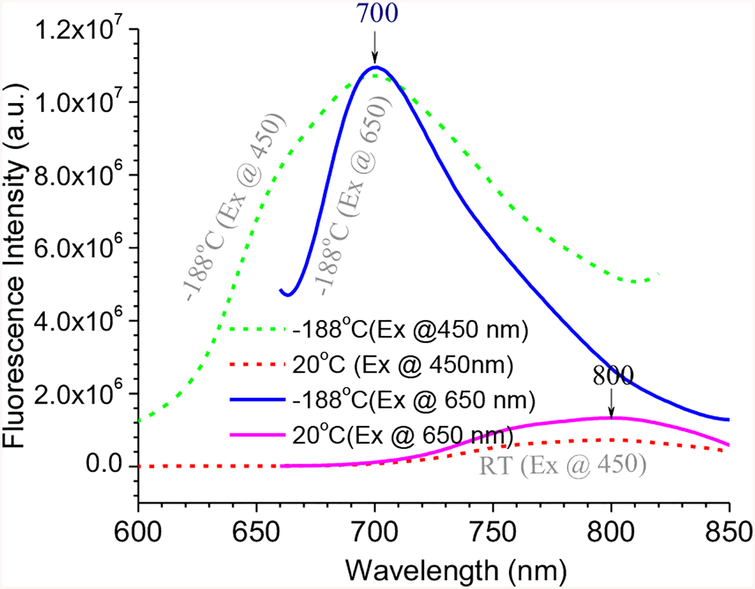

The observed NIR emission from 2 could be attributed to the formation of its keto form 4 (Scheme 2). Traditionally, one would assume that 4b is the species responsible for the NIR emission. An interesting question is where the protonated keto form 4a would give emission. In order to shed some light on their emissive property, we decided to freeze the dilute solution of 2 by liquid nitrogen, which would eliminate the dynamic impact of chemical equilibrium between 2a and 2b. Thus, a solution of 2 (in EtOH) in a quartz tube was cooled by immersing into liquid nitrogen in a quartz Dewar, and the fluorescence emission spectra were acquired by exciting the sample at 450 nm (ESI Figure S14) and 650 nm (ESI Figure S15) at different temperatures. At low temperature (at −189°C), emission of 2 became more intense and blue-shifted to λem ≈ 700 nm (Figure 4), as the probe molecules were frozen in a rigid solvent matrix (EtOH m.p. = −112°C). However, when the enol form 2a was excited selectively at 450 nm, the emission spectra revealed only one peak that had similar λem when the sample was excited at 650 nm (λex for keto form 2b). The result indicated that the enol form 2a was also capable of giving NIR emission.

Figure 4.

Fluorescence spectra of 2 at room temperature and low temperature, with λex at 450 nm (dotted lines) and 650 nm (solid lines).

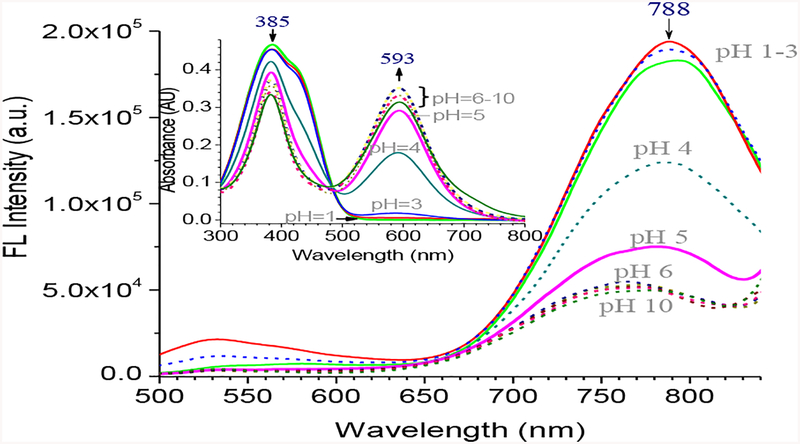

The pH response of 2 was examined by acquiring the optical spectra in different pH buffer solutions in water. In strong acidic buffer pH=1–3, 2 exhibited only one absorption band at 385 nm (Figure 5, ESI Figure S17), indicating that the equilibrium was completely shifted to 2a (Scheme 2). As pH increased, an additional absorption peak was observed at ~593 nm, which could be attributed to deprotonation of the phenolic proton. The pKa of 2 was determined to be 4.0 by Boltzmann’s fitting (ESI Figure S18), showing that the phenolic proton was quite acidic as a consequence of two electron-withdrawing benzothiazolium groups. Interestingly, the fluorescence of 2 revealed only one major emission peak λem≈788 nm in the entire pH range examined. When pH=1–3, probe 2 was expected to be in the enol form 2a, as revealed from its UV-vis spectra. Upon excitation, 2a could undergo the intramolecular charge transfer (ICT), which led to its keto tautomer 4a (Scheme 2). A notable feature was that the keto form 4a was only formed in the excited state, thereby giving the fluorescence signals at λem≈788 nm with very large Stokes shift.

Figure 5.

Fluorescence spectra of 2 (10 μM) in different pH buffer in water (excitation at 448 nm). Inset is the UV-absorption of the corresponding solution.

It should be notable that there was a significant difference between the optical properties of 1 and 2. Under the alkaline condition (e.g., pH=9–11), the resulting phenoxide from 1 was non-fluorescent as ESIPT was no longer operative.22 However, the phenoxide anion of 2 was still fluorescent, although the fluorescence intensity was higher under acidic pH (Figure 5). Since the phenolic proton of 2 was quite acidic, the formation of the phenoxide anion under physiological pH allowed the excitation of 2 at a longer wavelength, thereby raising the prospect for bioimaging applications. Evaluation of 2 also revealed that the probe was insensitive to different anions such as acetate (ACO−), adenosine monophosphate (AMP), adenosine diphosphate (ADP), adenosine triphosphate (ATP), pyrophosphate (PPi), biphosphate (HPO42-), thiosulfate (S2O32-), perchlorate (ClO4−), bisulfite (HSO3−) fluoride (F−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and some biothiols like cysteine (Cys), glutathione (GSH), and bovine serum albumin (BSA) (ESI Figures S19a and S20a). Considering the high abundance of glutathione in cells, compound 2 was treated with very high concentration of GSH (up to 10 mM), the optical properties of compound 2 was not affected by use of 1 mM (50 equivalents) of GSH. However, Absorbance was Blue shifted (ESI Figure S19b) and emission intensity was dropped (ESI Figure S20b) with the addition of 5mM (250 equivalents) concentration of GSH.

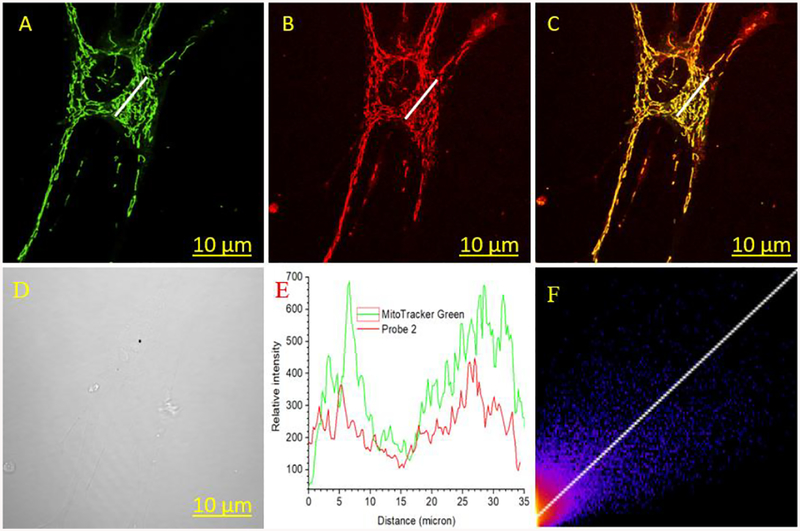

The fluorescence properties of 2 encouraged us to seek their potential applications for bioimaging. Cell viability studies by performing MTT assay showed that the half-maximal cell inhibitory concentration (IC50) 24.72 μM for 2 (ESI Figure S21), indicating its low toxicity. While using 2 to stain normal human lung fibroblast (NHLF) cells, confocal microscopic imaging (Figure 6B and ESI Figure S22) displayed fluorescence signal in a non-uniform pattern, indicating that the dye might bind to intracellular organelles selectively. Co-staining of 2 with MitoTracker Green FM showed good colocalization, (Figure 6C). The results confirmed that 2 exhibited excellent selectivity to the mitochondria, with a Pearson’s correlation coefficient 0.79 (Figure 6C & 6F). The results indicated that 2 was selective toward mitochondrial organelles, despite that the probe would give higher fluorescence in an acidic environment (pKa=4.01, and Figure 5).

Figure 6.

Normal human lungs fibroblast (NHLF) cells co-stained with 2 (1 μM) and MitoTracker green (200 nM), viewed in green (A) and NIR channel (B). (E) The plot of relative intensity vs. distance for probe 2 and MitoTracker Green for the region in white line in A and B, and (F) correlation plot between MitoTracker Green and 2. Excitation/emission λex/λem=488/525 nm for MitoTracker Green, and 640/(680 −735) nm for 2.

Probe 2 could be considered as a “functional mitochondrial probe” which is accumulated into mitochondria due to the potential gradient (Δψm) of the mitochondrial matrix,as suggested by using 2 in fixed cells (Fig. S24, ESI†). Compound 2 was also treated in different cell lines of human oligodendrocytes (ESI figure S23), the colocalization of 2 with MitoTracker Green demonstrated that there was proper overlapping between MitoTracker Green and compound 2 with a Pearson’s correlation coefficient of 0.67 which indicated that probe 2 was selective to Mitochondrial organelles in the live oligodendrocyte cells. It should be noted that the fluorescence imaging was acquired with 680 – 735 nm emission filter (due to the availability), and brighter imaging could be observed if the emission filter was near the peak fluorescence at ~788 nm. The results pointed to that 2 could be a useful molecular probe for bioimaging.

In summary, NIR (λem ≈ 800 nm) emitting probe 2 was synthesized, which showed large Stokes’ shifts via ICT mechanism. Probe 2 possessed an acidic phenol group with pKa = 4.01, which allowed formation of the keto-form to facilitate ICT interaction in the excited state. This extended the conjugation, thereby shifting the absorption and emission to the NIR region with large Stokes’ shifts. The acidic phenol group in the meta-phenylene bridge plays a vital role in enhancing the optical properties of 2, as the compound 3 without the phenol group gave weak emission at a much shorter wavelength (λem ≈ 470). Probe 2 with double positive charges was assumed to play a decisive role in the observed mitochondrial selectivity, due to Coulombic attraction toward the negative potential gradient of the mitochondrial matrix. Low cytotoxicity of 2 and its attractive NIR emission suggests that the probe could have promising application in live-cell imaging.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from NIH (Grant no. 1R15GM126438–01A1) and partial support from Coleman Endowment from The University of Akron. We thank Savannah Snyder for acquiring Mass spectrometric data

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

“There are no conflicts to declare”.

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [Synthesis and characterization of 2 and 3; 1H NMR and mass spectral data; and additional UV-vis absorption and fluorescence data. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

References

- 1.Nagaya T, Nakamura YA, Choyke PL and Kobayashi H, Frontiers in Oncology, 2017, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grossi M, Morgunova M, Cheung S, Scholz D, Conroy E, Terrile M, Panarella A, Simpson JC, Gallagher WM and O’Shea DF, Nature communications, 2016, 7, 10855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sedgwick AC, Wu L, Han H-H, Bull SD, He X-P, James TD, Sessler JL, Tang BZ, Tian H and Yoon J, Chemical Society Reviews, 2018, 47, 8842–8880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao N, Chen S, Hong Y and Tang BZ, Chemical Communications, 2015, 51, 13599–13602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gandre-Babbe S and M. A Bliek v. d., Molecular Biology of the Cell, 2008, 19, 2402–2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman JR and Nunnari J, Nature, 2014, 505, 335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu Z and Xu L, Chemical Communications, 2016, 52, 1094–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gottlieb E, Armour SM, Harris MH and Thompson CB, Cell Death And Differentiation, 2003, 10, 709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perry SW, Norman JP, Barbieri J, Brown EB and Gelbard HA, BioTechniques, 2011, 50, 98–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y, Zhou J, Wang L, Hu X, Liu X, Liu M, Cao Z, Shangguan D and Tan W, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2016, 138, 12368–12374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu B, Shah M, Zhang G, Liu Q and Pang Y, ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2014, 6, 21638–21644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long L, Huang M, Wang N, Wu Y, Wang K, Gong A, Zhang Z and Sessler JL, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2018, 140, 1870–1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh K, Rotaru AM and Beharry AA, ACS Chemical Biology, 2018, 13, 1785–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang S, Fan Y, Li D, Sun C, Lei Z, Lu L, Wang T and Zhang F, Nature communications, 2019, 10, 1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altınoǧlu EI, Russin TJ, Kaiser JM, Barth BM, Eklund PC, Kester M and Adair JH, ACS Nano, 2008, 2, 2075–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang S, Wu T, Fan J, Li Z, Jiang N, Wang J, Dou B, Sun S, Song F and Peng X, Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry, 2013, 11, 555–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X, Sun Q, Huang Z, Huang L and Xiao Y, Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 2019, 7, 2749–2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu W, Ma H, Hou B, Zhao H, Ji Y, Jiang R, Hu X, Lu X, Zhang L, Tang Y, Fan Q and Huang W, ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, 2016, 8, 12039–12047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang B, Cui X, Zhang Z, Chai X, Ding H, Wu Q, Guo Z and Wang T, Org. Biomol. Chem, 2016, 14, 6720–6728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun W, Guo S, Hu C, Fan J and Peng X, Chemical Reviews, 2016, 116, 7768–7817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piatkevich KD, English BP, Malashkevich VN, Xiao H, Almo SC, Singer RH and Verkhusha VV, Chemistry & biology, 2014, 21, 1402–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dahal D, McDonald L, Bi X, Abeywickrama C, Gombedza F, Konopka M, Paruchuri S and Pang Y, Chemical Communications, 2017, 53, 3697–3700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo Y, Dahal D, Kuang Z, Wang X, Song H, Guo Q, Pang Y and Xia A, AIP Advances, 2019, 9, 015229. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chu Q, Pang Y, Ding L and Karasz FE, Macromolecules, 2003, 36, 3848–3853. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.