Cellular organelles called mitochondria contain their own DNA. The discovery that variation in mitochondrial DNA alters physiology and lifespan in mice has implications for evolutionary biology and the origins of disease.

The maternally inherited DNA found in cytoplasmic organelles called mitochondria encodes the central proteins involved in energy production-the main function of this organelle. Yet, it has been assumed that the extraordinarily high sequence variability of the mitochondrial DNA is of little consequence. In a paper online in Nature, Latorre-Pellicer et al.1 dispel this erroneous notion.

The authors transferred mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) of a mouse strain called NZB to the nuclear DNA (nDNA) background of another strain, C57BL/6, and then compared C57BL/6 mice that harboured the NZB or C57BL/6 mtDNAs. The two mtDNAs differ in 12 amino-acid substitutions and 12 variants in RNA molecules involved in mitochondrial protein synthesis. Comparison of the mice throughout their lives revealed huge differences in mitochondrial function, insulin signaling, obesity and longevity. This and related studies2–4 clearly demonstrate that naturally occurring mtDNA variation is not neutral and that the interaction between mtDNA sequence variants and nDNA can have profound effects on mammalian biology.

Why should this be of general interest? It turns out that the amount of variation between NZB and C57BL/6 mtDNAs can be found between unrelated human mtDNAs5, so mtDNA variation and its effect on nDNA gene expression is also relevant to people.

Mouse and human mtDNA sequences can only evolve by sequentially accumulating mutations along radiating maternal lineages. For humans, functional mutations arose as women migrated out of Africa to colonize the rest of the world, modifying their cellular energy metabolism and allowing our ancestors to adapt to new regional environmental challenges6,7. The mtDNA types (haplotypes) that acquired these environmentally advantageous mutations expanded in their respective environments to give rise to regional groups of related haplotypes, called haplogroups. This regional selection explains why, of all the mtDNA lineages that evolved in Africa over the first 100,000 years of human history, only two mtDNAs (dubbed M & N) successfully left Africa 65,000 years ago to colonize the rest of the world. It also explains why only N mtDNAs colonized Europe, whereas both M and N colonized Asia, and why only five mtDNAs colonized the Americas5. Because human mtDNA diversity evolved from a single African mtDNA progenitor, functional mtDNA variation that allows regional population isolation may also contribute to speciation5. Hence, mtDNA haplogroups are fundamental to the biology of both mice and men.

Because mitochondria have a bioenergetics role, it makes sense that mtDNA variation affects our physiology and ability to adapt to environmental change5,8. Variation in mtDNA genes can permit accommodation to new diets, adjustment to thermal stress and activity demands, and even alter the regulation of cell death5. The correlation between human and mouse mtDNA variation and a broad range of traits, including longevity, physical capacity, and in humans, predisposition to a wide spectrum of metabolic and degenerative diseases and forms of cancer5,8–10, confirms the functional importance of mtDNA variation.

Nuclear gene expression is also affected by mtDNA variation, owing to the role of the mitochondrial energy-production system in modulating the levels of high-energy molecules generated through mitochondrial intermediate metabolism. High-energy mitochondrial metabolic products, such as the molecules ATP, acetylCoA and α-ketoglutarate, drive the modification of cytoplasmic signalling proteins and also add molecular modifications to nuclear proteins, which, together with nDNA modifications, constitute the epigenome11,12. Changes in cellular signaling and the epigenome then regulate nDNA gene expression. This coupling between the mitochondrion and the nucleus is crucial because no cellular function can proceed without sufficient energy. The nucleus must know that mitochondria can generate the required energy before proceeding with DNA replication and transcription, for example.

Studying cells that have the same nucleus but different levels of a pathogenic mtDNA mutation - a change in an RNA molecule where nucleotide 3243 is guanine (G) instead of the normal adenine (A) - has helped define the nature of the mtDNA–nDNA interactions. Each cell contains hundreds of mtDNA copies, so both mutant and normal mtDNAs can be present in the cell in different percentages, a state known as heteroplasmy13. When the 3243G mutation is present at a frequency of 10–30%, patients can manifest diabetes or, in rare cases, autism; at 50–90%, the mutant manifests as neurological, heart and muscle problems; and at 100%, it can result in childhood disease and death9. A study14 of nuclear gene expression in cell lines containing different percentages of the 3243G mutant revealed that each of these clinical classes of heteroplasmy level is associated with a distinct nuclear gene-expression profile14. In humans, then, as in Latorre-Pellicer and colleagues1 mice, subtle changes in mitochondrial function resulting from mtDNA variation can have profound effects on nuclear gene expression, cellular physiology, and individual health.

Uniparental inheritance of mtDNA is almost universal among animals, and mtDNA lineages are functionally different, so it might be predicted that artificially mixing two different mtDNA haplotypes in the same cell could be deleterious. Consistent with this prediction, mixing NZB mtDNAs with mtDNAs from a strain called 129 (whose mtDNA is similar to C57BL/6 mtDNA) in the C57BL/6J mouse results in mice that are hypo-active, hyper-excitable, and have severe long-term-memory defects15. Hence, bi-parental inheritance of different mtDNAs can be deleterious and the NZB and 129-C57BL/6 mtDNAs are functionally different.

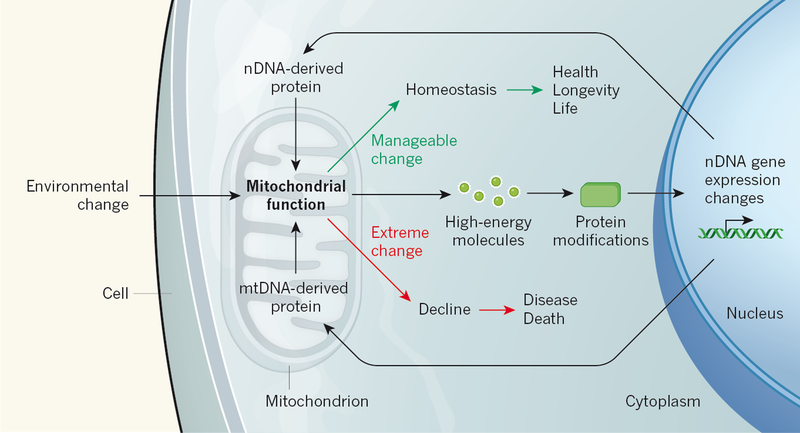

Because mtDNA haplogroup variation has been shaped by environmental selection, it follows that the mitochondria might be key sensors of environmental changes. From our emerging understanding of the many regulatory roles of mitochondria, a holistic picture of cell biology has started to emerge (Fig. 1). In this scenario, changes in the environment would affect mitochondrial bioenergetics and alter the production of high-energy mitochondrial molecules. Altered concentrations of these mitochondrial molecules drive the chemical modification of cytoplasmic-signalling and epigenomic proteins; reprogramming nDNA gene expression. The altered nDNA gene-expression status then feeds back to modify mitochondrial gene expression and re-establish energetic homeostasis and health. However, if the local environmental changes are too severe to be managed by an individual’s mtDNA haplogroup-defined physiological state, or if recent deleterious mtDNA mutations are too pathogenic, this feedback homeostasis system may fail, resulting in progressive energetic decline, disease and ultimately death (Figure 1).

Figure 1 |. Mitochondria as the central environmental sensor.

Latorre-Pellicer et al.1 report that the transfer of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from one mouse strain to another has pronounced effects on biology, demonstrating that mitochondrial genetic variation is not neutral and that mitochondrial–nuclear interactions are of central importance to mammalian physiology. Mitochondrial function is directly influenced by environmental changes such as diet, activity and inflammation caused by infection, so the mitochondrion must have a central role in mediating between environmental perturbations and genomic responses. High-energy molecules produced by the mitochondria modify the cytoplasmic signaling proteins and proteins that regulate nuclear DNA (nDNA) expression. These changes reprogram gene expression, including the expression of nDNA and mtDNA protein genes that act in and on the mitochondrion, which feeds back on mitochondrial function. If energetic homeostasis can be re-established health and longevity are preserved. However, if genetic or environmental changes are too extreme, then energetics production declines leading to disease and even death.

Latorre-Pellicer and colleagues’ paper1 provides direct evidence that naturally occurring mtDNA variation is fundamental to an individual’s characteristics and health. This information supports a model whereby mitochondrial physiological states determined by mtDNA variation sense environmental perturbations and send the appropriate signals to the nucleus to produce the optimal gene-expression response.

Biography

Douglas C. Wallace directs the Center for Mitochondrial and Epigenomic Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and is in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA.

References

- 1.Latorre-Pellicer A. et al. mtDNA and nuclear DNA matching shapes metabolism and healthy ageing. Nature (2016, in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu X. et al. Dissecting the effects of mtDNA variations on complex traits using mouse conplastic strains. Genome Res. 19, 159–165, doi: 10.1101/gr.078865.108 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Betancourt AM et al. Mitochondrial-nuclear genome interactions in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Biochemistry Journal 461, 223–232, doi: 10.1042/BJ20131433 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feeley KP et al. Mitochondrial genetics regulate breast cancer tumorigenicity and metastatic potential. Cancer Res. 75, 4429–4436, doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0074 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallace DC Mitochondrial DNA variation in human radiation and disease. Cell 163, 33–38, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.067 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruiz-Pesini E, Mishmar D, Brandon M, Procaccio V & Wallace DC Effects of purifying and adaptive selection on regional variation in human mtDNA. Science 303, 223–226 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ji F. et al. Mitochondrial DNA variant associated with Leber hereditary optic neuropathy and high-altitude Tibetans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 7391–7396, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202484109 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallace DC Mitochondrial bioenergetic etiology of disease. J. Clin. Invest 123, 1405–1412, doi: 10.1172/JCI61398 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallace DC, Lott MT & Procaccio V in Emery and Rimoin’s Principles and Practice of Medical Genetics Vol. 1 (eds Rimoin DL, Pyeritz RE, & Korf BR) Ch. 13, (Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Picard M. et al. Mitochondrial functions modulate neuroendocrine, metabolic, inflammatory, and transcriptional responses to acute psychological stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, E6614–E6623, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515733112 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace DC & Fan W Energetics, epigenetics, mitochondrial genetics. Mitochondrion 10, 12–31, doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2009.09.006 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace DC, Fan W & Procaccio V Mitochondrial energetics and therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Path 5, 297–348, doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092314 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallace DC & Chalkia D Mitochondrial DNA genetics and the heteroplasmy conundrum in evolution and disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 5, a021220, doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021220 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Picard M. et al. Progressive increase in mtDNA 3243A>G heteroplasmy causes abrupt transcriptional reprogramming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, E4033-E4042, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414028111 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharpley MS et al. Heteroplasmy of mouse mtDNA Is genetically unstable and results in altered behavior and cognition. Cell 151, 333–343, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.004 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]