Abstract

Context

Motorcycle crashes account for a disproportionate number of motor vehicle deaths and injuries in the U.S. Motorcycle helmet use can lead to an estimated 42% reduction in risk for fatal injuries and a 69% reduction in risk for head injuries. However, helmet use in the U.S. has been declining and was at 60% in 2013. The current review examines the effectiveness of motorcycle helmet laws in increasing helmet use and reducing motorcycle-related deaths and injuries.

Evidence acquisition

Databases relevant to health or transportation were searched from database inception to August 2012. Reference lists of reviews, reports, and gray literature were also searched. Analysis of the data was completed in 2014.

Evidence synthesis

A total of 60 U.S. studies qualified for inclusion in the review. Implementing universal helmet laws increased helmet use (median, 47 percentage points); reduced total deaths (median, −32%) and deaths per registered motorcycle (median, −29%); and reduced total injuries (median, −32%) and injuries per registered motorcycle (median, −24%). Repealing universal helmet laws decreased helmet use (median, −39 percentage points); increased total deaths (median, 42%) and deaths per registered motorcycle (median, 24%); and increased total injuries (median, 41%) and injuries per registered motorcycle (median, 8%).

Conclusions

Universal helmet laws are effective in increasing motorcycle helmet use and reducing deaths and injuries. These laws are effective for motorcyclists of all ages, including younger operators and passengers who would have already been covered by partial helmet laws. Repealing universal helmet laws decreased helmet use and increased deaths and injuries.

CONTEXT

Motorcycle crashes contribute considerably to preventable fatal and non-fatal injuries in the U.S. Although motorcycles only account for about 3% of registered vehicles and 0.7% of traveled vehicle miles, a disproportionate 15% of all motor vehicle crash fatalities were due to motorcycle crashes in 2013.1 The U.S. Government Accountability Office estimated that the total direct measurable costs from motorcycle-related crashes were approximately $16 billion in 2010.2 A Cochrane systematic review found that motorcycle helmet use can lead to an estimated 42% reduction in risk for fatal injuries and a 69% reduction in risk for head injuries.3 Helmet use in the U.S., however, remained around 60% in 2013.4

Motorcycle helmet laws require motorcycle riders to wear a helmet while riding on public roads. In the U.S., these laws are implemented at the state level with varying provisions and fall into two categories: universal helmet laws (UHLs), which apply to all motorcycle operators and passengers; and partial helmet laws (PHLs), which apply only to certain motorcycle operators such as those under a specified age (usually 18 years), novices (most often defined as having <1 year of experience), or those who do not meet the state’s requirement for medical insurance coverage. Further, motorcycle passengers are not consistently covered under PHLs.

According to the National Occupant Protection Use Survey conducted by the National Center for Statistics and Analysis of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, helmet use is seen to be “significantly higher in states that require all motorcyclists to be helmeted,” that is, states with UHLs.5 The number of states implementing UHLs peaked in 1975, with 47 states requiring all motorcyclists to wear helmets. Since then, many states have repealed UHLs.6 Currently, 19 states and the District of Columbia have UHLs.6 Among the other states, 28 states have PHLs and three states (Illinois, Iowa, and New Hampshire) have no motorcycle helmet laws.6

The current review aims to evaluate the effectiveness of UHLs in increasing helmet use and decreasing fatal and non-fatal injuries. This review was a collaborative effort between researchers from the U.S. (Community Guide Branch and National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, both at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]) and Australia (The George Institute for Global Health at the University of Sydney). Researchers from the George Institute will prepare a companion review with a global focus, including evidence from low- and middle-income countries. This paper is based solely on evidence from the U.S.

The research questions for this review are:

How effective are motorcycle helmet laws in achieving the following outcomes?

Increasing helmet use

Reducing fatal and non-fatal injuries

Does helmet law effectiveness vary by the following factors?

Universal helmet law versus partial helmet law

Setting characteristics, such as rural versus urban

Population characteristics, such as age, gender, race/ethnicity, or SES

EVIDENCE ACQUISITION

Detailed systematic review methods used for the Community Guide have been published previously.7,8 For this review, a coordination team was formed, composed of motor vehicle injury prevention subject matter experts from various agencies, organizations, and academic institutions, together with systematic review methodologists from the Community Guide Branch at CDC. The team worked under the oversight of the independent, unpaid, nonfederal Community Preventive Services Task Force whose members are appointed to 5-year terms by the director of CDC.

Conceptual Approach and Analytic Framework

The analytic framework (Appendix Figure 1, available online) shows the postulated mechanism through which motorcycle helmet laws affect incidence and severity of non-fatal and fatal injuries. UHLs can lead to increased helmet use, resulting both in reduced incidence and severity of non-fatal injuries and in reduced fatal injuries. If motorcycle helmet laws affect overall motorcycle use, as some have speculated,9 that could also contribute to observed decreases in fatal and non-fatal injuries. Other factors that may influence helmet use or injury include strength of the law (UHLs versus PHLs); intensity of enforcement efforts; type of helmet used (U.S. Department of Transportation approved or non-approved); and individual attitudes such as the desire not to wear a helmet.

Search for Evidence

Reviewers from the George Institute in Sydney, Australia, conducted the search for evidence, and the detailed search strategy can be found at: www.thecommunityguide.org/mvoi/motorcyclehelmets/supportingmaterials/SShelmetlaws.html. Briefly, databases relevant to health or transportation were searched from database inception to August 2012. Reference lists of reviews and reports relevant to the current review were also searched. Two reviewers from the George Institute performed the initial screening and eliminated publications not evaluating motorcycle helmet laws. Reviewers from CDC’s Community Guide Branch further screened the publications using the predetermined inclusion criteria listed below.

Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included in the current review if they evaluated motorcycle helmet laws and also met the following criteria:

published in English;

published journal article or government report; and

reported at least one outcome of interest.

Assessing and Summarizing the Body of Evidence on Effectiveness

Study abstraction

Each study meeting the inclusion criteria was independently abstracted by two reviewers. Reviewers from the George Institute developed abstraction forms by adapting guidelines from the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care group.10 Information on intervention components, population demographics, and outcomes was gathered using these forms. Uncertainties and disagreements were reconciled by consensus among review team members.

Risk of bias assessment

The team evaluated each study’s risk of bias using templates adapted from the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care group10: Were data analyzed properly? Was the intervention independent of other changes? Were sufficient data points used for reliable statistical inference? Was the intervention unlikely to affect data collection? Was primary outcome assessment blinded? Was the data set complete? Were primary outcome measures reliable?

Studies could be of high, low, or unclear risk for each of these criteria. Quality of each included study was assessed by two reviewers independently, and uncertainties and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Outcomes of interest

Outcomes commonly used to evaluate the impact of helmet laws were identified and abstracted for this review, including helmet use, total fatal and non-fatal injuries, and fatal and non-fatal injury rates. The included studies used data sources such as the Fatality Analysis Reporting System from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, state highway safety departments’ databases, and hospitals that admitted motorcyclists injured in motorcycle-related crashes. Total fatal or non-fatal injuries (with or without hospital admission) are direct measures of helmet law impact on a population and were commonly reported by the included studies. Total injury counts, however, are affected by the amount of motorcycle use (“riding exposure”), which could change in response to the presence or absence of UHLs. To account for this potential change, injury rates were collected or calculated from the included studies, including fatal and non-fatal injuries per registered motorcycle, traveled vehicle miles, or crashes. Outcomes that were less commonly reported but useful for answering the research questions were also collected, including injury severity and neck injuries.

Analysis

Helmet use was reported using percentage point (pct pt) changes; for example, helmet use rate post-law change - helmet use rate pre-law change or helmet use rate in states with UHLs - helmet use rate in states without UHLs. All other outcomes were reported using relative percentage changes. Some studies (studies using panel design or the autoregressive integrated moving average model) provided calculated effect estimates as relative changes and no further calculation was needed. Effect estimates were calculated for all other studies. For studies examining impact of a law change, only the data points immediately before and after the law change were used to calculate effect estimates to minimize the effect of secular changes on the outcomes of interest.

For overall summary measures, the median of effect estimates from individual studies and the interquartile interval, which is the interval between the first and third quartiles, were calculated for each outcome. Strength of evidence on effectiveness was based on the number of studies, the quality of available evidence, consistency of results, and magnitude of effect estimates, per Community Guide standards.7,8 Analyses of the data were completed in 2014.

EVIDENCE SYNTHESIS

Search Yield

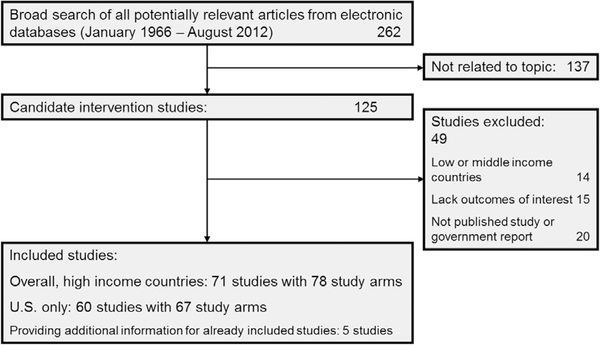

A total of 262 potentially relevant articles were identified in the search for evidence, and 125 were candidates for inclusion. Forty-nine articles were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria: Three papers11–13 were not published in English, 11 papers14–24 evaluated helmet laws in low- or middle-income countries, 20 papers25–44 were not primary evaluations, and 15 papers45–59 did not report on the outcomes of interest. Overall, 71 studies60–130 with 78 study arms were included in the current review (Figure 1), with five studies131–135 providing additional information on already included studies. Of the 71 included studies, 60 studies60–66,68–72,74,76–79,81–90,92–106,108–116,120–122,125–130 with 67 study arms evaluated helmet laws in the U.S. As mentioned above, this paper is solely focused on the U.S., and only U.S. data are reported in the following sections.

Figure 1.

Search results.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Detailed assessment results can be found on the Community Guide website (www.thecommunityguide.org/mvoi/motorcyclehelmets/supportingmaterials/ROB-hel metlaws.pdf). All included studies were observational studies and no study performed blinded assessment of primary outcomes. Included studies obtained data from routine government and hospital reports, which were unlikely to be affected by helmet laws or law changes. Most included studies examined helmet laws or law changes that were independent of other traffic safety interventions.60–66,68–71,74,76–79,81–90,92–97,99–106,108–116,120–122,125–130 Some studies did not provide sufficient data points for reliable statistical inference,92,113,114,130 had missing data,62,72,92 or did not describe statistical methods.72,87,88,92,94,95,98,111,120,122,125,126,130 Three studies99,122,126 reported observed helmet use without describing study methods; outcome reliability could not be assessed.

Study and Intervention Characteristics

Sixty studies60–66,68–72,74,76–79,81–90,92–106,108–116,120–122,125–130 with 67 study arms evaluated motorcycle helmet laws in the U.S. These studies either evaluated law changes such as helmet law implementations (from no or partial laws to UHLs)60,71,74,78,88,89,94,95,99,101,103,104,109,116 or repeals (from UHLs to partial or no laws),61,63,66,70–72,81–83,85,87,90,92,93,96,98,100,105,106,108,111,116,121,122,125–128 or compared the impact of UHLs to partial or no helmet laws.62,64,65,68,69,76,77,79,84–86,96,97,102,106,110,112–115,120,129,130 Study designs included in the review were panel,64,70,71,76,77,79,81,84–86,102,112,115,128 time series or before–after with concurrent comparison groups,62,65,66,96,97,110,114,120,126,129 interrupted time series,61,74,78,103,105,121 uncontrolled before–after,60,63,72,82,83,87–90,92–96,98–101,104,106,108,109,111,116,122,125,127 and cross-sectional.68,69,106,113,114,130 More detailed information can be found at: www.thecommunityguide.org/mvoi/motorcyclehelmets/supportingmaterials/SET-helmetlaws.pdf.

Demographic Characteristics From Included Studies

Twenty-two studies60,63,65,68,69,78,82,83,87,89,90,95,96,99,101,104,108,110,113,125,127,129 of the 60 from the U.S. reported population characteristics. The study population consisted of motorcycle riders and passengers observed for helmet use125 or who sustained fatal or non-fatal injuries during motorcycle crashes.60,63,65,68,69,78,82,83,87,89,90,95,96,99,101,104,108,110,113,127,129 Mean age of the study population was 36.5 years60,63,65,68,69,78,82,83,87,89,95,96,101,104,108,113,127 and a median of 91% were male.60,63,65,68,69,78,82,83,87,89,90,95,96,99,101,104,108,110,113,125,127,129

Outcomes

Impact of helmet laws was assessed through the following outcomes: helmet use, motorcycle crash-related fatal and non-fatal injuries, and injury rates. These outcomes were assessed and reported in three categories:

law implementing: study arms evaluating the change in outcomes when states with no or partial helmet laws implemented UHLs;

law repealing: study arms evaluating the change in outcomes when states repeal UHLs, changing to no or partial helmet laws; and

law comparison: study arms comparing outcomes from states with UHLs to states with partial or no helmet laws.

The included studies reported many outcomes, almost all indicating substantial benefits associated with UHLs when compared to partial or no helmet law (Table 1). In the presence of UHL, there was higher prevalence of helmet use (Appendix Figure 2, available online); fewer fatal (Figure 2) and non-fatal injuries (Appendix Figure 3, available online); and lower injury rates. In the absence of UHL, there was lower prevalence of helmet use (Appendix Figure 4, available online); greater fatal (Figure 3) and non-fatal injuries (Appendix Figure 5, available online); and higher injury rates. Head-related fatal (Figures 2 and 3) or non-fatal injuries (Appendix Figures 3 and 5, available online) were especially affected by presence or absence of UHLs.

Table 1.

Impact of UHLs on Helmet Use and Fatal and Non-fatal Injuries

| Law implementinga |

Law repealingb |

Law comparisonc |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | No. of study arms | Median (IQI/range)d | No. of study arms | Median (IQI/range)d | No. of study arms | Median (IQI/range)d |

| Helmet use, absolute change | 9e,60,78,88,89,94,99,101,103,104 | 49 pct pts (42 to 58 pct pts) | 21e,61,63,72,83,87,90,92,93,96,100,106,108,111,116,122,125,126 | −41 pct pts (−48 to −31 pct pts) | 696,106,110,113,114,130 | 53 pct pts (51 to 60 pct pts) |

| Fatalities, relative change (total, head-related, rates) | ||||||

| Total | 10f,60,71,74,78,89,98,99,104,109,111 | −32% (−52% to −26%) | 20f,63,66,72,81,82,87,93,98,100,105,108,111,122,125,126,128 | 42% (26% to 67%) | 776,77,79,86,112,115,120 | −24% (−29% to −22%) |

| Head-related | 5f,60,74,89,99,109 | −51% (−55% to −43%) | 2f,72,100 | 6% and 65% | 1120 | −47% |

| Fatalities per registered motorcycle | 9f,60,89,98,103,104,109,111,114,116 | −29% (−45% to −20%) | 18f,63,72,82,85,92,93,96,98,100,105,108,111,116,121,125,126 | 24% (9% to 42%) | 764,79,85,86,97,102,120 | −12% (−15% to −4%) |

| Fatalities per vehicle mile travelled | – | – | 361,105,125 | 23% (14% to 38%) | 286,97 | −27% and −22% |

| Fatalities per crash | 478,98,109,116 | −15% (−29% to −4%) | 1263,70,72,82,87,90,93,98,100,116,122,125 | 23% (1% to 36%) | 1120 | −14% |

| Fatality rate, head, per registered motorcycle | 1109 | −41% | 272,100 | −5% and 25% | 1120 | −17% |

| Fatality rate, head, per crash | 1109 | −22% | 572,100,106 | 60% (12% to 362%) | 1120 | −27% |

| Injuries, relative change (total, head-related, rates) | ||||||

| Total | 7g,74,88,89,95,101,104,109 | −32% (−39% to −15%) | 10g,63,82,83,93,100,111,122,125,126 | 41% (19% to 61%) | 176 | −20% |

| Head-related | 4g,74,88,89,95 | −54% (−49% to −59%) | 4g,72,100,111,127 | 74% (53% to 83%) | 362,68,129 | −27% (−12% to −44%) |

| Injuries per registered motorcycle | 4g,95,103,104,109 | −24% (−28% to −9%) | 9g,63,92,93,100,111,121,125,126 | 8% (0% to 38%) | – | – |

| Injuries per vehicle mile travelled | – | – | 1125 | −8% | – | – |

| Injuries per crash | 1109 | −1% | 763,83,93,100,122,125,127 | −1% (−8% to 35%) | – | – |

| Head-related injuries per registered motorcycle | 195 | −44% | 3100,111,127 | 31% (29% to 39%) | – | – |

| Head-related injuries per crash | – | – | 4100,111,127 | 50% (33% to 105%) | – | – |

| Youth | ||||||

| Helmet use, absolute change | 199 | 31 pct pts | 582,90,111,125,127 | −17 pct pts (−19 to −3 pct pts) | 296,106 (4 effect estimates) | 42 pct pts (31 to 59 pct pts) |

| Fatalities, relative change | ||||||

| Total | 195 | −48% | 390,125,127 | 125% (116% to 189%) | 184 | −31% |

| Fatalities per vehicle mile travelled | – | – | 190 | 97% | – | – |

| Injuries, relative change | ||||||

| Total | – | – | – | – | 168 | 8% |

| Head-related | – | – | – | – | 1129 | −12% |

UHLs replaced partial or no helmet laws.

Partial or no helmet laws replaced UHLs.

UHLs versus partial or no helmet laws.

IQIs calculated with ≥5 studies; otherwise ranges reported.

Appendix Figures 2 and 4 (available online).

Appendix Figures 3 and 5 (available online).

IQI, interquartile interval; pct pts, percentage points; UHL, universal helmet law.

Figure 2.

Impact of implementing UHLs on fatality outcomes.

UHL, universal helmet law.

Figure 3.

Impact of repealing UHLs on fatality outcomes.

UHL, universal helmet law.

As of 2016, a total of 47 states in the U.S. had either UHLs or PHLs. The team performed additional analyses specifically to compare the laws’ effectiveness; results are summarized in Appendix Table 1 (available online). Results are similar to the overall findings that compared UHL to partial or no helmet laws (Table 1); states with UHLs, when compared with states with PHLs, have much higher helmet use and fewer fatal and non-fatal injuries.

The PHLs apply only to certain motorcycle operators. As of 2015, all 28 PHL states covered motorcyclists under a certain age (usually ≤21 years).6 The team summarized youth-specific data (Table 1) to determine if PHLs protect this population; the results are described below.

Impact of Universal Helmet Laws on Young Motorcyclists

Helmet use

Implementing UHLs99 increased helmet use among young motorcyclists (aged <21 years) by an estimated 31 pct pts in one study, and repealing UHLs82,90,111,125,127 decreased helmet use by a median of 17 pct pts (interquartile interval, −19 to −3 pct pts). Two96,106 law comparison study arms with four effect estimates found that youth helmet use was a median of 42 pct pts (range, 31–59 pct pts) higher in states with UHLs when compared with states with partial or no laws.

Fatal injuries

Implementing UHLs95 decreased fatalities among youth involved in motorcycle crashes by an estimated 48% in one study, and three others found that repealing UHLs90,125,127 increased fatalities by a median of 125% (range, 116%−189%). One84 law comparison study arm found that total fatal injuries were 31% lower in states with UHLs versus states with no laws.

Fatality rates

One study found that repealing UHLs90 led to an increase of 97% in fatalities per traveled vehicle mile. One65 study arm compared the impact of PHLs to no helmet law, and found no difference in fatalities per registered motorcycle between states with PHLs and states with no helmet law.

Non-fatal injuries

Compared with states with partial or no laws, young motorcyclists (aged <21 years) in states with UHLs experienced 8% higher motorcycle crash-related hospitalization68 but 12% lower motorcycle crash-related hospitalization due to non-fatal head injuries.129

DISCUSSION

In 2013, an estimated 1,630 lives were saved by motorcycle helmets in the U.S., and an additional 715 lives could have been saved if all motorcyclists were wearing helmets.136 Over the past few decades, however, the trend in the U.S. has been to repeal UHLs. The arguments made by opponents of UHLs include that helmet use should be a personal choice instead of state policy, helmet effectiveness is not certain, and data on helmet law effectiveness are inconclusive. Individual rights are an important consideration for policymakers, but are beyond the scope of the current review. Evidence from the present review complements the Cochrane systematic review and demonstrates the effectiveness of UHLs.

Michigan was the latest state to repeal its UHL in April 2012, and evaluations of this law change were published recently. Two reports found that the repeal resulted in decreased helmet use,137 increased fatalities and fatalities per crash,137 and increased medical care costs to the state,138 consistent with the findings from the current review.

In addition to being more effective than PHLs, UHLs are easier to enforce. The characteristics specified in PHLs (e.g., age, experience, level of medical insurance) are not easily evaluated by law enforcement officers monitoring traffic. By contrast, UHLs apply to all motorcycle operators and passengers, making anyone riding without a helmet easily identifiable.

Currently, all PHLs in the U.S. cover young motorcyclists, usually aged <18 years.6 Evidence from the present review shows that any protection provided by PHLs is small in comparison to that provided by UHLs.

In 2013, approximately 9% of U.S. motorcyclists wore unapproved helmets.4 The U.S. Department of Transportation requires that all motorcycle helmets sold in the U.S. meet Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard 218. This standard defines minimum performance levels that helmets must meet to protect the head and brain in the event of a crash, including factors such as inner liner thickness, weight of helmet, and chin strap sturdiness. A recent study139 in California reported that motorcycle riders wearing novelty helmets (defined as half-helmet not meeting the Department of Transportation standard) were almost three times more likely to suffer from head injuries when compared with riders wearing full-face helmets. As of 2015, a total of 12 states with UHLs and 16 states with PHLs require the use of Department of Transportation-approved helmets.6 Training traffic law enforcement officers in these states to recognize unapproved helmets, and thereby enforce existing laws, may improve helmet law effectiveness.

Although UHLs increase helmet use and reduce fatal and non-fatal injuries, they do not prevent motorcycle-related crashes. Policies that are effective in reducing overall motor vehicle crashes could be relevant to motorcycle safety, such as reducing alcohol-impaired driving and reducing speeding.140

Limitations

This body of evidence included a wide range of study designs. Even though each design comes with unique risks of bias, effect estimates across multiple study types, population groups, and outcome measures were remarkably consistent within the context of this review, and with independent estimates of efficacy of helmet use,3 demonstrating robustness of findings.

Total motorcycle-related fatal or non-fatal injuries are widely used measures of helmet law effectiveness. These total injury counts, however, are affected by the amount of motorcycle use (“riding exposure”), which could change in response to the presence or absence of UHLs. Many included studies attempted to account for driving exposure by dividing total counts of fatal and non-fatal injuries by the number of registered motorcycles, traveled vehicle miles, or crashes. Regardless of the specific measure used, UHLs were shown to be more effective than PHLs or no law in reducing fatal and non-fatal injuries.

Applicability

The current review focused on motorcycle helmet laws in the U.S. Some of the included studies performed stratified analyses based on certain demographic characteristics. Evidence showed that UHLs were effective for male and female motorcyclists in increasing helmet use,90,96,99 decreasing fatal and non-fatal injuries,81,90,127 and decreasing fatalities per crash.90 Compared with motorcycle operators, passengers usually had a lower prevalence of helmet use irrespective of the helmet law,90,94,99,106 though implementing UHLs increased helmet use94,99 and reduced fatal injuries88,89,99 for both operators and passengers. When UHLs were repealed, passengers experienced greater decreases in helmet use90 and greater increases in total fatal injuries and fatal injuries per crash.90 Two studies compared helmet law effectiveness in rural versus urban areas and found that implementing UHLs reduced fatal injuries in both settings60 and repealing UHLs increased fatal and non-fatal injuries in urban settings.122

The UHLs were effective across age groups in increasing helmet use90,96,99,106,125 and decreasing overall fatal injuries81,90,95,125 and fatal injuries per crash.90 Young motorcyclists, when compared with their older counterparts, experienced larger decreases in fatal injuries when UHLs were implemented95 and larger increases in total fatal injuries and fatal injuries per crash when UHLs were repealed.90,125

Other Benefits or Harms

No additional benefits of motorcycle helmet laws were identified in the included studies or in the broader literature.

Although one of the postulated harms associated with helmet use is increased risk of neck injuries, the ten included study arms62,68,69,82,89,99,103,104,109,127 that assessed this outcome found that fatal and non-fatal neck injuries accounted for a very small proportion of motorcycle-related injuries (median, 1.8%; interquartile interval, 0.2%−3.2%) and the type of helmet law had no noticeable effect on neck injury prevalence. One study arm found that implementing a UHL resulted in a reduction of 0.5 pct pts in neck injury-related fatalities.99 Studies reporting non-fatal injuries found little difference in the prevalence of neck injuries between states with UHLs and states with PHLs or no law (median, −0.6 pct pts; range, −0.6 to 0.1 pct pts),62,68,69 and minimal changes in prevalence of neck injuries when UHLs were repealed (0.1–0.2 pct pts)82,127 or implemented (median, 0.0 pct pts; range, −0.3 to 0.6 pct pts).89,103,104,109

Other postulated harms of helmet use include hearing or vision impairment, though evidence from laboratory and field research does not show much support for these claims.141 Finally, some researchers have raised concerns about risk compensation, postulating that riders wearing helmets feel safer and increase their risk-taking behaviors (reviewed by Hedlund142 in 2000). Evidence on this issue is limited, though authors of one study analyzed data from on-scene, in-depth investigations of motorcycle- related crashes in Los Angeles and concluded that helmet use was not associated with riskier behaviors.143

Evidence Gaps

Although substantial evidence shows UHLs are effective across population groups and settings, research gaps remain. Future studies could examine the role of enforcement on helmet law effectiveness, particularly in regard to the use of unapproved helmets.

More research is needed to better understand the impact of helmet laws on riders of low-powered motorized cycles (e.g., scooters, mopeds) that have been gaining popularity, especially in urban settings. In 2016, all types of low-powered cycles were covered in 12 of 19 states with UHLs and 11 of 28 states with PHLs; the remaining states with helmet laws covered motorized cycles above certain thresholds, such as engine displacement greater than 50 cc or those designed to go faster than 30 mph.6

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, UHLs are much more effective than partial or no helmet laws in increasing helmet use and reducing fatal and non-fatal motorcycle crash injuries. U.S. states that repealed UHLs and replaced them with PHLs or no law consistently experienced substantial decreases in helmet use and increases in fatal and non-fatal injuries. States that implemented UHLs in place of PHLs or no law consistently experienced substantial increases in helmet use and decreases in fatal and non-fatal injuries. PHLs exist in 29 states in the U.S., and a separate analysis was conducted to compare only UHLs and PHLs (Appendix Table 1, available online), with results nearly identical to the overall analysis that compared UHLs to partial or no helmet laws (Table 1). These findings are generally applicable to all motorcyclists, irrespective of age and gender, in both rural and urban settings.

Studies included in the current review assessed impact of motorcycle helmet laws using a diverse set of outcomes. Many studies attempted to account for potential changes in motorcycle use by providing fatal and non-fatal injuries per registered motorcycle, traveled vehicle mile, or crash. Compared with total count results, these rate results were smaller in magnitude but still demonstrate that UHLs were more effective in reducing fatal and non-fatal injuries than PHLs or no law. Because helmets protect the cranial region, helmet laws can be expected to have a greater impact on head-related fatal and non-fatal injuries than overall fatal and non-fatal injuries; results from the current review confirm this hypothesized relationship.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the late David Preusser (Preusser Research Group) for his invaluable contribution to this review. Kate W. Harris, from the Community Guide Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, provided input at various stages of the review and the development of the manuscript.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The work of Cristian Dumitru, Ramona Finnie, Gibril Njie, Yinan Peng, Jeffrey Reynolds, and Namita Vaidya was supported with funds from the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Names and affiliations of the Community Preventive Services Task Force members can be found at: www.thecommunityguide.org/about/task-force-members.html.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental materials associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/mvoi-ajpm-app-universalhelmets.pdf.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Center for Statistics and Analysis. Motorcycles: 2013 data. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2015. Report No.: DOT HS 812 148 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Government Accountability Office. Motorcycle Safety: Increasing Federal Funding Flexibility and Identifying Research Priorities Would Help Support States’ Safety Efforts. Washington, DC: U.S. GAO, 2012: 13–42. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu B, Ivers R, Norton R, Boufous S, Blows S, Lo S. Helmets for preventing injury in motorcycle riders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008(1):CD004333 10.1002/14651858.cd004333.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pickrell TM, Liu C. Motorcycle helmet use in 2013—overall results. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2014. Report No.: DOT HS 812 010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pickrell TM, Ye TJ. Motorcycle helmet use in 2012—overall results. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2013. Report No.: DOT HS 811 759. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. Motorcycle helmet use. www.iihs.org/iihs/topics/laws/helmetuse?topicName=motorcycles. Published 2016. Accessed March 25, 2016.

- 7.Briss PA, Zaza S, Pappaioanou M, et al. Developing an evidence- based Guide to Community Preventive Services—methods. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1) (suppl):35–43. 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zaza S, Wright-De Aguero LK, Briss PA, et al. Data collection instrument and procedure for systematic reviews in the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1) (suppl):44–74. 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzwater A, Perry H. The truth about helmet laws. www.ncrider.com/Truth_About_Helmet_Laws_v1_10-22-04.htm. Accessed February 16, 2016.

- 10.Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC). EPOC resources for review authors. Oslo: Norwegian Knowledge Center for the Health Services; http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors. Published 2015. Accessed February 16, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.La Torre G Epidemiology of scooter accidents in Italy: the effectiveness of mandatory use of helmets in preventing incidence and severity of head trauma [in Italian]. Recenti Prog Med. 2003;94(1): 1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marchi AG, Messi G, Porebski E, Loschi L. Evaluation of the usefulness of the motorcycle helmet in adolescents in Trieste [in Italian]. Minerva Pediatr. 1989;41(6):329–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tributsch W, Rabl W, Ambach E. Fatal accidents of motorcycle riders. Comparison of the craniocervical injury picture before and following introduction of the legally sanctioned protective helmet rule [in German]. Beit Gerichtl Med. 1989;47:625–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asogwa SE. The crash helmet legislation in Nigeria: a before-and-after study. Accid Anal Prev. 1980;12(3):213–216. 10.1016/0001-4575(80)90021-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Andrade SM, Soares DA, Matsuo T, Lopes C, Liberatti B, Iwakura MLH. Road injury-related mortality in a medium-sized Brazilian city after some preventive interventions. Traffic Inj Prev. 2008;9(5):450–455. 10.1080/15389580802272831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elia SM, Humphreys RM. A Question of Safety: A Preliminary Study: A Critique and Proposal for Study of Motor Cycle Helmet Use in Khon Kaen, Thailand. Brisbane, Australia: University of Queensland; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Espitia-Hardeman V, Velez L, Gutierrez-Martinez MI, Espinosa- Vallin R, Concha-Eastman A. Impact of interventions directed toward motorcyclist death prevention in Cali, Colombia: 1993–2001 [in Spanish]. Salud Publica Mex. 2008;50(suppl 1):S69–S77. 10.1590/S0036-36342008000700011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falope IA. Motorcycle accidents in Nigeria. A new group at risk. West Afr J Med. 1991;10(2):187–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ichikawa M, Chadbunchachai W, Marui E. Effect of the helmet act for motorcyclists in Thailand. Accid Anal Prev. 2003;35:183–189. 10.1016/S0001-4575(01)00102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Law TH, Noland RB, Evans AW. Factors associated with the relationship between motorcycle deaths and economic growth. Accid Anal Prev. 2009;41(2):234–240. 10.1016/j.aap.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liberatti CLB, Andrade SM, Soares DA. The new Brazilian traffic code and some characteristics of victims in southern Brazil. Inj Prev. 2001;7(3):190–193. 10.1136/ip.7.3.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Panichaphongse V, Watanakajorn T, Kasantikul V. Effects of helmet- use law on death from motorcycle accidents. J Med Assoc Thai. 1995;78(10):521–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Passmore J, Tu NTH, Luong M, Chinh N, Nam N. Impact of mandatory motorcycle helmet wearing legislation on head injuries in Viet Nam: results of a preliminary analysis. Traffic Inj Prev. 2010;11 (2):202–206. 10.1080/15389580903497121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Supramaniam V, van Belle G, Sung JFC. Fatal motorcycle accidents and helmet laws in Peninsular Malaysia. Accid Anal Prev. 1984;16 (3):157–162. 10.1016/0001-4575(84)90009-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams J Public safety legislation and the risk compensation hypothesis: the example of motorcycle helmet legislation. Environ Plann C Gov Policy. 1983;1(2):193–230. 10.1068/c010193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balmer H Analysis of the Mandatory Motorcycle Helmet Issue. Harrisburg, PA: Governor’s Traffic Safety Council; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berkowitz A The Effect of the Motorcycle Helmet Usage on Head Injuries and the Effect of Usage Laws on Helmet Wearing Rates. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bledsoe G Arkansas and the motorcycle helmet law. J Ark Med Soc. 2004;100(12):430–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Espitia V, Concha-Eastman A, Espinosa R, Gutierrez M. Characteristics of motorcycle drivers deaths after the implementation of a compulsory law for helmet use. Paper presented at: 6th World Conference on Injury Prevention and Control; 2002; Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Government Accountability Office. Highway Safety: Motorcycle Helmet Laws Save Lives and Reduce Costs to Society. Washington, DC: U.S. GAO; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knudson MM, Schermer C, Speetzen L. Motorcycle helmet laws: every surgeon’s responsibility. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199(2):261–264. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kruse T, Nordentoft EL, Weeth R. The effect of mandatory crash helmet use for moped riders in Denmark. Paper presented at: 22nd Annual Conference of the American Association for Automotive Medicine; 1978; Morton Grove, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin DY, Lin PC. Study on motorcycle traffic safety in Taiwan area. Paper presented at: Third Conference of Road Engineering Association of Asia and Australasia 1981; Taipei, Taiwan. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin M-R, Kraus J. A review of risk factors and patterns of motorcycle injuries. Accid Anal Prev. 2009;41(4):710–722. 10.1016/j.aap.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lowenstein SR, Koziol McLain J, Glazner J. The Colorado motorcycle safety survey: public attitudes and beliefs. J Trauma. 1997;42(6): 1124–1128. 10.1097/00005373-199706000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McSwain NE, Belles A. Motorcycle helmets—medical costs and the law. J Trauma. 1990;30(10):1189–1197. 10.1097/00005373-199010000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McSwain NE, Petrucelli E. Medical consequences of motorcycle helmet nonusage. J Trauma. 1984;24(3):233–236. 10.1097/00005373-198403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mersky A, Eberhardt M, Overfield P, Melanson S, Stoltzfus J, Prestosh J. The effect of the repeal of the Pennsylvania helmet law on the severity of head and neck injuries sustained in motorcycle accidents. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(3):S94 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.06.332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muller A Weakening of Florida’ s motorcycle helmet law: the first thirty months. Paper presented at: 132nd American Public Health Association Annual Meeting; 2004. Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Neill B, Kyrychenko S. Use and misuse of motor-vehicle crash death rates in assessing highway-safety performance. Traffic Inj Prev. 2006;7(4):307–318. 10.1080/15389580600832661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rollberg CA. The mandatory motorcycle helmet law issue in Arkansas: the cost of repeal. J Ark Med Soc. 1990;86(8):312–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russo PK. Easy rider—hard facts: motorcycle helmet laws. N Engl J Med. 1978;299(19):1074–1076. 10.1056/NEJM197811092991915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thoma T National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) Notes: An analysis of motorcycle helmet use in fatal crashes. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53(4):501 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.01.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vaca F Commentary: motorcycle helmet law repeal: when will we learn … or truly care to learn? Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47(2):204–206. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.12.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chiu W The motorcycle helmet law in Taiwan. JAMA. 1995;274 (12):941–942. 10.1001/jama.1995.03530120033027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chiu W, Chu S, Chang C, Lui T, Chiang Y. Implementation of a motorcycle helmet law in Taiwan and traffic deaths over 18 years. JAMA. 2011;306(3):267–268. 10.1001/jama.2011.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chiu W, Huang S, Tsai S, et al. The impact of time, legislation, and geography on the epidemiology of traumatic brain injury. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14(10):930–935. http://dx.doi.Org/10.1016/j.jocn.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dalkie H, Mulligan GWN. The Impact of Bill 60: A Study to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Mandatory Seat Belt and Motorcycle Helmet Use Legislation in Manitoba. Manitoba, Canada: University of Manitoba; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heilman DR, Weisbuch JB, Blair RW, Graf LL. Motorcycle-related trauma and helmet usage in North Dakota. Ann Emerg Med. 1982;11 (12):659–664. 10.1016/S0196-0644(82)80258-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iowa Department of Transportation. Iowa Motorcycle Accidents 1974–1976. Iowa: Office of Safety Programs, Iowa Department of Transportation; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jamieson KG, Kelly D. Crash helmets reduce head injuries. Med J Aust. 1973;2(17):806–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muller A Evaluation of the costs and benefits of motorcycle helmet laws. Am J Public Health. 1980;70(6):586–592. 10.2105/AJPH.70.6.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Offner PJ, Rivara FP, Maier RV. The impact of motorcycle helmet use. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 1992;32(5):636–642. 10.1097/00005373-199205000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peek-Asa C, McArthur DL, Kraus JF. The prevalence of nonstandard helmet use and head injuries among motorcycle riders. Accid Anal Prev. 1999;31(3):229–233. 10.1016/S0001-4575(98)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pileggi C, Bianco A, Nobile CGA, Angelillo IF. Risky behaviors among motorcycling adolescents in Italy. J Pediatr. 2006;148(4):527–532. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Richardson H A motorcycle safety helmet study. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic and Safety Administration, 1974: 137. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schuchmann JA. Motorcycle helmet laws—legislative frivolity or common sense. Tex Med. 1988;84(2):34–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsauo J-Y, Hwang J-S, Chiu W-T, Hung C-C, Wang J-D. Estimation of expected utility gained from the helmet law in Taiwan by quality-adjusted survival time. Accid Anal Prev. 1999;31(3):253–263. 10.1016/S0001-4575(98)00078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weisbuch JB. The prevention of injury from motorcycle use: epidemiologic success, legislative failure. Accid Anal Prev. 1987;19 (1):21–28. 10.1016/0001-4575(87)90014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Auman KM, Kufera JA, Ballesteros MF, Smialek JE, Dischinger PC. Autopsy study of motorcyclist fatalities: the effect of the 1992 Maryland Motorcycle Helmet Use Law. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(8):1352–1355. 10.2105/AJPH.92.8.1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bavon A, Standerfer C. The effect of the 1997 Texas motorcycle helmet law on motorcycle crash fatalities. South Med J. 2010;103 (1):11—17. 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181c35653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Berkowitz A Evaluation of state motorcycle helmet laws using the national electronic injury surveillance system. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 1981: 062. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bledsoe G, Li G. Trends in Arkansas motorcycle trauma after helmet law repeal. South Med J. 2005;98(4):436–440. 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000154309.83339.C0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Branas CC, Knudson MM. Helmet laws and motorcycle rider death rates. Accid Anal Prev. 2001;33(5):641–648. 10.1016/S0001-4575(00)00078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brooks E, Naud S, Shapiro S. Are youth-only motorcycle helmet laws better than none at all? Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2010;31(2):5 10.1097/PAF.0b013e3181c6beab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chenier TC, Evans L. Motorcyclist fatalities and the repeal of mandatory helmet wearing laws. Accid Anal Prev. 1987;19(2):133–139. 10.1016/0001-4575(87)90032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chiu W-T, Kuo C-Y, Hung C-C, Chen M. The effect of the Taiwan motorcycle helmet use law on head injuries. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(5):793–796. 10.2105/AJPH.90.5.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Coben JH, Steiner CA, Miller TR. Characteristics of motorcycle- related hospitalizations: comparing states with different helmet laws. Accid Anal Prev. 2007;39(1):190–196. 10.1016/j.aap.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dao H, Lee J, Kermani R, et al. Cervical spine injuries and helmet laws: a population-based study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72 (3):638–641. 10.1097/TA.0b013e318243d9ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.de Wolf V The effect of helmet law repeal on motorcycle fatalities. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 1986: 065. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dee TS. Motorcycle helmets and traffic safety. J Health Econ. 2009;28 (2):398–412. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wisconsin Department of Transportation. Wisconsin Motorcycle Helmet Law: A Before and After Study of Helmet Law Repeal. Wisconsin: Wisconsin Department of Transportation, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ferrando J, Plaséncia A, Orós M, Borrell C, Kraus JF. Impact of a helmet law on two wheel motor vehicle crash mortality in a southern European urban area. Inj Prev. 2000;6(3):184–188. 10.1136/ip.6.3.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fleming NS, Becker ER. The impact of the Texas 1989 motorcycle helmet law on total and head-related fatalities, severe injuries, and overall injuries. Med Care. 1992;30(9):832–845. 10.1097/00005650-199209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Foldvary L, Lane J. The effect of compulsory safety helmets on motorcycle accident fatalities. Aust Road Res. 1964:18. [Google Scholar]

- 76.French M, Gumus G, Homer J. Public policies and motorcycle safety. J Health Econ. 2009;28(4):831–838. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.French M, Gumus G, Homer J. Motorcycle fatalities among out-of-state riders and the role of universal helmet laws. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:9 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gilbert H, Chaudhary N, Solomon M, Preusser D, Cosgove L. Evaluation of the Reinstatement of the Helmet Law in Louisiana. May. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Graham JD, Lee Y. Behavioral response to safety regulation. Policy Sci. 1986;19(3):253–273. 10.1007/BF00141650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grima FG, Ontoso IA, Ontoso EA. Helmet use by drivers and passengers of motorcycles in Pamplona (Spain), 1992. Eur J Epidemiol. 1995;11(1):87–89. 10.1007/BF01719951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hartunian NS, Smart CN, Willemain TR, Zador PL. The economics of safety deregulation: lives and dollars lost due to repeal of motorcycle helmet laws. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1983;8(1):76–98. 10.1215/03616878-8-1-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ho E, Haydel M. Louisiana motorcycle fatalities linked to statewide helmet law repeal. J La State Med Soc. 2004;156(3):151–152 154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hotz G, Cohn S, Popkin C, et al. The impact of a repealed motorcycle helmet law in Miami-Dade County. J Trauma. 2002;52(3):469–474. 10.1097/00005373-200203000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Houston DJ. Are helmet laws protecting young motorcyclists? J Safety Res. 2007;38(3):329–336. 10.1016/j.jsr.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Houston DJ, Richardson LE. Motorcycle safety and the repeal of universal helmet laws. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(11):2063–2069. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.094615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Houston DJ, Richardson LE. Motorcyclist fatality rates and mandatory helmet-use laws. Accid Anal Prev. 2008;40(1):200–208. 10.1016/j.aap.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Koehler M Evaluation of Motorcycle Safety Helmet Usage Laws: Final Report. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University, 1978. Texas Traffic Safety Program Contract IAC 78-08-36-A-1-AA. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kraus J, Peek C. The impact of two related prevention strategies on head injury reduction among nonfatally injured motorcycle riders, California, 1991–1993. J Neurotrauma. 1995;12(5):873–881. 10.1089/neu.1995.12.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kraus J, Peek C, McArthur D, Williams A. The effect of the 1992 California motorcycle helmet use law on motorcycle crash fatalities and injuries. JAMA. 1994;272(19):1506–1511. 10.1001/jama.1994.03520190052034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kyrychenko SY, McCartt AT. Florida’s weakened motorcycle helmet law: effects on death rates in motorcycle crashes. Traffic Inj Prev. 2006;7(1):55–60. 10.1080/15389580500377833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.La Torre G, Van Beeck E, Bertazzoni G, Ricciardi W. Head injury resulting from scooter accidents in Rome: differences before and after implementing a universal helmet law. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17 (6):607–611. 10.1093/eurpub/ckm028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lloyd LE, Lauderdale M, Betz TG. Motorcycle deaths and injuries in Texas: helmets make a difference. Tex Med. 1987;83(4):30–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lummis ML, Dugger C. Impact of the repeal of the Kansas Mandatory Motorcycle Helmet Law, 1975 to 1978: an executive summary. EMT J. 1981;5(4):254–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lund AK, Williams AF, Womack KN. Motorcycle helmet use in Texas. Public Health Rep. 1991;106(5):576–578. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Max W, Stark B, Root S. Putting a lid on injury costs: the economic impact of the California motorcycle helmet law. J Trauma. 1998;45 (3):550–556. 10.1097/00005373-199809000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mayrose J The effects of a mandatory motorcycle helmet law on helmet use and injury patterns among motorcyclist fatalities. J Safety Res. 2008;39(4):429–432. 10.1016/j.jsr.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.McGwin G, Whatley J, Metzger J, Valent F, Barbone F, Rue L. The effect of state motorcycle licensing laws on motorcycle driver mortality rates. J Trauma. 2004;56(2):415–419. 10.1097/01.TA.0000044625.16783.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.McHugh TP, Raymond JI. Safety helmet repeal and motorcycle fatalities in South Carolina. J S C Med Assoc. 1985;81(11):588–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.McSwain N, Willey A, Janke T. Impact of re-enactment of the motorcycle helmet law in Louisiana. Proceedings: American Association for Automotive Medicine Annual Conference 1985;29:425–446. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mertz KJ, Weiss HB. Changes in motorcycle-related head injury deaths, hospitalizations, and hospital charges following repeal of Pennsylvania’s mandatory motorcycle helmet law. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1464–1467. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.123299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mock CN, Maier RV, Boyle E, Pilcher S, Rivara FP. Injury prevention strategies to promote helmet use decrease severe head injuries at a level I trauma center. J Trauma. 1995;39(1):29–33. 10.1097/00005373-199507000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Morris CC. Generalized linear regression analysis of association of universal helmet laws with motorcyclist fatality rates. Accid Anal Prev. 2006;38(1):142–147. 10.1016/j.aap.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mounce N, Brackett Q, Hinshaw W, Lund A, Wells J. The Reinstated Comprehensive Motorcycle Helmet Law in Texas. Arlington, VA: Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Muelleman RL, Mlinek EJ, Collicott PE. Motorcycle crash injuries and costs: effect of a reenacted comprehensive helmet use law. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21(3):266–272. 10.1016/S0196-0644(05)80886-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Muller A Florida’s motorcycle helmet law repeal and fatality rates. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(4):556–558. 10.2105/AJPH.94.4.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. A Report to Congress on the Effect of Motorcycle Helmet Use Law Repeal—A Case for Helmet Use. Washington, DC: NHTSA; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nurchi GC, Golino P, Floris F, Meleddu V, Coraddu M. Effect of the law on compulsory helmets in the incidence of head injuries among motorcyclists. J Neurosurg Sci. 1987;31(3):141–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.O’Keeffe T, Dearwater S, Gentilello L, Cohen T, Wilkinson J, McKenney M. Increased fatalities after motorcycle helmet law repeal: is it all because of lack of helmets? J Trauma. 2007;63(5):1006–1009. 10.1097/TA.0b013e31815644cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Paulsrude S, Kahl S, Klingberg G. An Evaluation of Washington State’s Motorcycle Safety Law’s Effectiveness. Washington State: Washington Department of Motor Vehicles, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pickrell TM, Starnes M. An analysis of motorcycle helmet use in fatal crashes. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, 2008. Report No.: DOT HS 811 011. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Preusser DF, Hedlund JH, Ulmer RG. Evaluation of motorcycle helmet law repeal in Arkansas and Texas. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2000. Report No.: DOT HS 809 131. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Prinzinger J The effect of the repeal of helmet use laws on motorcycle fatalities. Atl Econ J. 1982;10(2):36–39. 10.1007/BF02300066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Proscia N, Sullivan T, Cuff S, et al. The effects of motorcycle helmet use between hospitals in states with and without a mandatory helmet law. Conn Med. 2002;66(4):195–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Robertson L An instance of effective legal regulation: motorcyclist helmet and daytime headlamp laws. Law Soc Rev. 1976;10(3):467–477. 10.2307/3053144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sass T, Zimmerman P. Motorcycle helmet laws and motorcyclist fatalities. J Regul Econ. 2000;18(3):195–215. 10.1023/A:1008124703161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Scholten DJ, Glover JL. Increased mortality following repeal of mandatory motorcycle helmet law. Indiana Med. 1984;77(4): 252–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Servadei F, Begliomini C, Gardini E, Giustini M, Taggi F, Kraus J. Effect of Italy’s motorcycle helmet law on traumatic brain injuries. Inj Prev. 2003;9(3):257–260. 10.1136/ip.9.3.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Singh C, Robson SH, Toomath JB. Traffic Research Report: Compulsory Safety Helmet Legislation and Motor Cyclist Accidents. Wellington, New Zealand: Traffic Research Section, Road Transport Division, Ministry of Transport; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Singh C, Robson SH, Toomath JB. Report No. 9: Motorcycle Helmet and Headlamp Checks 1973. Wellington, New Zealand: Road Transport Division, Ministry of Transport, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sosin DM, Sacks JJ. Motorcycle helmet-use laws and head injury prevention. JAMA. 1992;267(12):1649–1651. 10.1001/jama.1992.03480120087038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Stolzenberg L, D’Alessio SJ. “Born to Be Wild”: the effect of the repeal of Florida’s mandatory motorcycle helmet-use law on serious injury and fatality rates. Eval Rev. 2003;27(2):131–150. 10.1177/0193841X02250524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Struckman-Johnson C, Ellingstad V. Impact of motorcycle helmet law repeal in South Dakota 1976–79: final report. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 1980. Report No.: DOT HS 9 02130. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Taggi F Safety helmet law in Italy. Lancet. 1988;331(8578):182 10.1016/S0140-6736(88)92754-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Tsai M-C, Hemenway D. Effect of the mandatory helmet law in Taiwan. Inj Prev. 1999;5(4):290–291. 10.1136/ip.5.4.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Turner P, Hagelin C. Florida motorcycle helmet use observational survey and trend analysis. Tampa, FL: Center for Urban Transportation Research, University of South Florida, 2004. Report No.: BC 353 RPWO 36. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ulmer R, Preusser D. Evaluation of the repeal of motorcycle helmet laws in Kentucky and Louisiana; Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2003. Report No.: DOT HS 809 530. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ulmer R, Shabanova-Northrup V. Evaluation of the repeal of the all-rider motorcycle helmet law in Florida. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2005. Report No.: DOT HS 809 849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Watson GS, Zador PL, Wilks A. The repeal of helmet use laws and increased motorcyclist mortality in the United States, 1975–1978. Am J Public Health. 1980;70(6):579–585. 10.2105/AJPH.70.6.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Weiss H, Agimi Y, Steiner C. Youth motorcycle-related brain injury by state helmet law type: United States, 2005–2007. Pediatrics. 2010;126(6):1149–1155. 10.1542/peds.2010-0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Williams A, Ginsburg M, Burchman P. Motorcycle helmet use in relation to legal requirements. Accid Anal Prev. 1979;11(4):271–273. 10.1016/0001-4575(79)90053-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Bledsoe G, Schexnayder S, Carey M, et al. The negative impact of the repeal of the Arkansas motorcycle helmet law. J Trauma. 2002; 53(6):1078–1086. 10.1097/00005373-200212000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Branas CC, Knudson MM. State helmet laws and motorcycle rider death rates. LDI Issue Brief. 2001;7(1):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Dare CE, Owens JC, Krane S. Impact of motorcycle helmet usage in Colorado. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 1978. Report No.: DOT HS 803680. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kraus J, Peek C, Williams A. Compliance with the 1992 California motorcycle helmet use law. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(1):96–99. 10.2105/AJPH.85.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Peek-Asa C, Kraus JF. Estimates of injury impairment after acute traumatic injury in motorcycle crashes before and after passage of a mandatory helmet use law. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;29(5):630–636. 10.1016/S0196-0644(97)70252-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Estimating lives and costs saved by motorcycle helmets with updated economic cost information. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffice Safety Administration; 2015. Report No.: DOT HS 812 206. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Flannagan CAC, Bowman PJ. Analysis of motorcycle crashes in Michigan 2009–2013. Lansing, MI: Michigan State Police, Office of Highway Safety Planning, 2014 Report No.: UMTRI-2014–35. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Highway Loss Data Institute. The Effects of Michigan’s Weakened Motorcycle Helmet Use Law on Insurance Losses. Arlington, VA: Highway Loss Data Institute, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Erhardt T, Rice T, Troszak L, Zhu M. Motorcycle helmet type and the risk of head injury and neck injury during motorcycle collisions in California. Accid Anal Prev. 2016;86:23–28. 10.1016/j.aap.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Goodwin A, Thomas L, Kirley B, Hall W, O’Brian N, Hill K. Countermeasures That Work: A Highway Safety Countermeasure Guide for State Highway Safety Offices, Eighth Edition, Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 141.McKnight AJ, McKnight AS. The effects of motorcycle helmets upon seeing and hearing. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 1994. Report No.: DOT HS 808 399. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Hedlund J Risky business: safety regulations, risk compensation, and individual behavior. Inj Prev. 2000;6(2):82–89. 10.1136/ip.6.2.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Ouellet J Helmet use and risk compensation in motorcycle accidents. Traffic Inj Prev. 2011;12(1):71–81. 10.1080/15389588.2010.529974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.