Abstract

Introduction: Black women are more likely to be diagnosed at later stages of breast cancer compared with White women due to lower frequency of screening and lack of timely follow-up after abnormal screening results. Disparities in breast cancer screening, risk, and mortality are present within both Black women and sexual minority communities; however, there exists limited research concerning breast cancer care among Black sexual minority women.

Materials and Methods: This scoping review examines the literature from 1990 to 2017 of the breast cancer care continuum among Black sexual minority women, including behavioral risk factors, screening, treatment, and survivorship. A total of 91 articles were identified through PubMed, PsycINFO, and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) databases. Fifteen articles were selected for data extraction, which met the criteria for including Black/African American women, discussing breast cancer care among both racial and sexual minorities, and being a peer-reviewed article.

Results: The 15 articles were primarily within urban contexts, and defined sexual minorities as lesbian or bisexual women. Across all the studies, Black sexual minority women were highly under-represented, and key conclusions are not fully applicable to Black sexual minority women. Sexual minority women had a higher prevalence of breast cancer risk factors (i.e., nulliparity, fewer mammograms, higher alcohol intake, and lower oral contraceptive use). Furthermore, some studies noted homophobia from health providers as potential barriers to engagement in care for sexual minority women.

Conclusions: The lack of studies concerning Black sexual minority women in breast cancer care indicates the invisibility of a group that experiences multiple marginalized identities. More research is needed to capture the dynamics of the breast cancer care continuum for Black sexual minority women.

Keywords: breast cancer, sexual minority, African American, screening, cancer treatment

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in women.1 Disparities in breast cancer screening, risk, and mortality have been found in studies of both Black women and sexual minority women across races.2–5 In this article, the term sexual minority refers to those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, or same-gender loving.6 Black women are likely to be diagnosed at later stages of breast cancer than White women due to lower frequency of screening, longer time between screenings, and lack of timely follow-up after abnormal screening results7–10 even among those who are insured.11 Similarly, research suggests that sexual minority women have higher breast cancer risks than heterosexual women due to higher rates of nulliparity, alcohol consumption, smoking, and obesity.12 Despite this higher risk, sexual minority women have a lower lifetime prevalence of mammograms compared with heterosexual women13 and less timely screening13–17 due to lower perceived severity and perceptions of heterosexism and homophobia among providers.14–17

Black sexual minority women who face intersecting issues of racism and homophobia may be at even greater risk compared with women who belong to only one of these minority groups. The intersection of race and sexuality creates a unique context for breast cancer screening and timely follow-up after abnormal screening results;18,19 yet, there is little research to inform effective interventions for Black sexual minority women. The objective of this scoping study is to identify and summarize the literature on breast cancer screening and subsequent care among Black sexual minority women.

Materials and Methods

A five-step approach was used to complete the scoping review that consisted of (1) identifying a research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) selecting studies, (4) presenting the data, and (5) collating the results.20,21

Data sources

The following electronic databases were searched: PubMed, PsycINFO, and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature). Two reviewers used the following Boolean search phrases in these databases: “female homosexuality and breast cancer,” “sexual minority and breast cancer,” and “female bisexuality and breast cancer.” These searches resulted in 91 articles after removing duplicates. Two reviewers proceeded to screen articles based on eligibility criteria.

Data selection

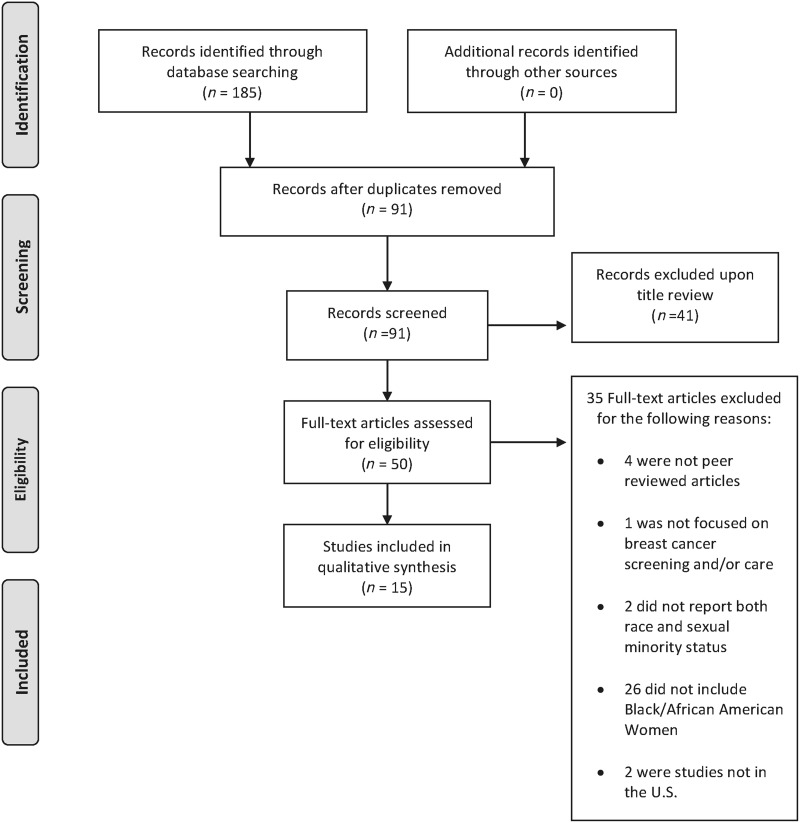

Articles were deemed eligible for review if they were published between January 1, 1990 and November 20, 2017, published in a peer-reviewed journal, focused on breast cancer screening and/or care as a primary research question, and had a study population that included Black/African American sexual minority women. Studies that did not report both race and sexual minority status were excluded. When screening these studies, articles were classified into the following categories: (1) review articles or commentaries, (2) primary observational data, (3) intervention evaluations, and (4) modeling studies. Study staff documented the quantity of articles at each stage of the screening process using a PRISMA flow diagram. This screening process yielded 15 articles for data extraction and collation.

Data extraction

For each eligible article, the two screening reviewers documented a summary of results and general contribution to the literature concerning breast cancer care and screening among Black sexual minority women. The reviewers also assigned more specific categorizations of the study design for each study. The reviewers compared results to assure consistency with extractions. The resulting review reports the characteristics, primary outcomes, and overall research gaps concerning breast cancer screening and care among sexual minority women that were found among the eligible articles. The review also presents the public health implications of what is known about breast cancer screening and care (or lack thereof) among Black sexual minority women, and presents suggestions for how this area of research can be expanded.

Results

Of the original 91 articles, abstract reviews confirmed that 41 articles were not related to the topic or population of interest. Of the remaining 50, full-text article review yielded 15 articles that matched our criteria. Not including Black/African American women was the primary reason articles were excluded (Fig. 1). The final 15 articles included 13 primary data observational studies and 2 modeling studies. No experimental study designs, review articles, or intervention evaluations were identified. Of the 15 articles, two were qualitative studies, one was a mixed-methods approach, while the rest were quantitative studies that were cross-sectional except for two cohort studies.

FIG. 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Terms used across the articles to describe sexual minority women included lesbian, bisexual, or sexual minority. The geographical contexts of the studies were explored primarily in urban or large city contexts, thus articles were limited in addressing the unique complexities experienced by rural populations. There were no more than two articles found for each investigator or research team in our review with the exception of Boehmer et al. who had three articles included in the review. All studies included Black/African American women and attempted to stratify by race, but studies with smaller sample sizes did not have the statistical power to detect significant differences. Finally, there has not been much research on these topics in recent years as only two studies included in the review were conducted as late as 2015.

Below, we first describe the under-representation of Black sexual minority women across the breast cancer care continuum among the studies included in the scoping review. Subsequently, we present articles that explore the experiences of Black sexual minority women along the breast cancer care continuum, including (1) behavioral risk factors and risk assessment, (2) screening, and (3) treatment and survivorship,22 comparing sexual minority and heterosexual women for each area. The overall descriptions and key findings of the articles included in the review can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Articles Included in Scoping Review

| Author | Year published | Recruitment method | Study details (study design; study name; and data collection year if applicable) | Populations and sample size | Cancer focus | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arena et al.23 | 2007 | Convenience sampling by nationwide distribution of fliers at women's networks and community resource centers. Matched with Miami-based hospitals. |

Case–control study | N = 78 Previously treated for breast cancer n = 39 Lesbian women n = 39 Heterosexual women | Breast cancer treatment | ● Lesbians more likely to report having stressful thoughts regarding cancer compared with heterosexuals ● Heterosexual women were more concerned about body image and sexual issues ● No difference in the overall amount of available social support, although lesbians used more emotional support from friends than heterosexuals. |

| Austin et al.26 | 2012 | Single mailing sent out to registered nurses between the ages of 25–42 to 14 most populous U.S. states. Those who responded to initial questionnaire were enrolled in the cohort | Quantitative prospective cohort study; Nurses' Health Study II; 1989–2005 | N = 116,430 Women aged 25–42 in 14 most populous U.S. states; data collected 1989–2005; 1.5% African American (n = 5,145), 94% White (n = 334,519) | Breast cancer screening | ● Receipt of mammogram in the last 2 years was slightly higher in heterosexuals ● Fewer than half of eligible participants received colorectal screening and did not differ based on sexual orientation ● No difference by race/ethnicity except for African American women and colorectal screening (30% more compared with White women) |

| Boehmer et al.32 | 2005a | Community-based purposeful sampling and snowball sampling | Qualitative study; individual interviews | N = 30 SMW with breast cancer n = 23 of whom had support providers | Breast cancer coping | ● SMW's level of disclosure impacts the level of distress reported by support providers. |

| Boehmer et al.51 | 2005b | Community-based purposeful sampling and snowball sampling | Quantitative cross-sectional study | N = 64 SMW with breast cancer. | Breast cancer coping | ● Positive association between “fighting spirit” and social support as well as a negative association between “fighting spirit” and distress. ● Lesbians had lower distress than bisexual women or women who partnered with other women. |

| Boehmer et al.50 | 2007 | Community-based and snowball sampling | Qualitative study; individual semistructured interviews | N = 27 n = 15 SMW n = 12 of SMW support partners. | Breast cancer treatment defined as mastectomy and reconstructive surgery | ● Decision to do reconstructive surgery dealt with body image and value system shaped by sexual minority identity. ● Women who did reconstruction had regrets and difficulties while those who did not transitioned better into recovery. |

| Clavelle et al.28 | 2015 | Retrospective review of all mammography patients at community health center in | Modeling study; quantitative retrospective cohort study; 2013–2014 | N = 423 Women n = 162 SMW n = 13 SMW Black n = 38 Hetero Black | Breast cancer screening | ● SMW were more likely to be nulliparous (risk factor for breast cancer) and overall had higher lifetime Gail scores than hetero women ● SMW had lower prevalence of birth control pills |

| Northeast United States | ● No differences in mammogram screening between hetero and sexual minority | |||||

| Cochran et al.13 | 2001 | n/a | Quantitative cross-sectional meta-analysis from 1987 to 1996: Boston Lesbian Health Project, National Lesbian and Bisesual Women's Health Survey, Michigan Lesbian Health Survey, Massachusetts Lesbian Health Needs Assessment, Houston Lesbian Health Initiative, North Carolina Women's Health Access Survey, and Oregon Lesbian Health Survey | N = 11,876 SMW | Breast cancer screening | ● Greater prevalence of behavioral risk factors for breast and gynecological cancers among lesbian and bisexual women compared with the general female population. ● Lesbians and bisexual women are more likely to be obese than other women, less likely to give birth, less likely to use oral contraceptives, less likely to undergo routine screening procedures (mammograms and gynecological examinations) influenced by negative experiences with health care practitioners and mistrust of health care community. |

| DeHart34 | 2008 | Convenience sampling in Southern Cities (Columbia, SC; Louisville, KY; Wilmington, NC). | Modeling study; quantitative cross-sectional study | N = 173 Exclusively homosexual women n = 9 Black homosexual women | Breast cancer screening | ● Women perceived heterosexism and homophobia from providers to influence the amount of discussion they had with providers, such that it significantly contributed to women's use of self-examinations and limited health care provider visits. |

| Grindel et al.29 | 2006 | Community-based sampling and snowball sampling | Quantitative cross-sectional study; Boston Lesbian Health Project II | N = 1,139 Lesbians n = 46 Black women | Breast cancer screening | ● Majority of women did not smoke, had diets high in fruits and vegetables, low in fat and moderate in alcohol. ● Most women had mammograms and PAP smears as recommended; however, they did not adhere to self-breast examination guidelines. ● Older age, high income, nonsmoking status, and self-breast examination were positively associated with having mammogram. |

| Jabson and Bowen25 | 2014 | Convenience sampling of 211 breast cancer survivors via online through breast cancer groups | Quantitative cross-sectional study | N = 211 Breast cancer n = 68 SMW n = 143 Heterosexual women | Breast cancer treatment | ● The average perception of stress is 8.2 and standard deviation of 1.4 out of a total of 16 possible points. ● When stratified by sexual orientation, heterosexual breast cancer survivors reported less perceived stress (M = 8.10, s = 1.50) than sexual minority breast cancer survivors (M = 8.54, s = 1.30). ● Sexual orientation was significantly associated with perceived stress (B = −0.15, p = 0.03). |

| Matthews et al.2 | 2013 | Convenience sample of lesbians and heterosexual women with a diagnosis of breast cancer in the last 5 years | Qualitative study focus groups | n = 13 Lesbians n = 28 Heterosexual women n = 11 Black heterosexual n = 1 Black Lesbian | Satisfaction of breast cancer treatment from physicians | ● Lesbians had higher stress levels associated with diagnosis, lower satisfaction with care from physicians during treatment, and lower satisfaction with availability of emotional support. |

| McElroy et al.3 | 2015 | Random sampling by landline or cell phone for Missouri Counties. | Quantitative cross-sectional study; Missouri County-Level Study; January through December 2011 | N = 29,847 Heterosexual women n = 114 Lesbian women | Breast cancer screening | ● No significant differences in cancer screenings between sexual minority and heterosexual women or time since recommended cancer screenings. ● Lesbians had higher educational attainment; lesbian (but no bisexual) women were more likely to report smoking and to be obese. |

| Rankow et al.33 | 1998 | Convenience sampling via outreaching at pride events, lesbian bars, bookstores, churches, etc. | Mixed-methods cross-sectional study | N = 591 SMW n = 112 Black n = 409 White | Breast cancer screening | ● Mammography is associated with majority sociodemographic characteristics such as older age, being White, having insurance, and higher incomes. ● Women with higher education (p = <0.0001) and incomes (p = 0.02) were more likely to report breast self-examination. ● The most frequently reported barriers to mammography were costs (24%), lack of feeling at risk (21%), no health insurance (18%), and radiation concerns (18%). |

| Roberts et al.35 | 2004 | Quota sampling | Quantitative cross-sectional study; 1987 | N = 1139 Lesbian women n = 46 Black women | Breast cancer screening and treatment | ● Lesbians in this sample were more likely to be “out” to their provider compared with lesbians in the past (10 years before) ● Older women were more likely to be “out” to provider than younger women. ● Screening for pap smears and breast cancer is still lower than expected. ● High rates of drinking (for whole sample) and smoking (among younger women) still persist in this sample. |

n/a, not applicable; PAP, Papanicolaou; SMW, sexual minority women.

Under-representation of Black/African American women

There were very few Black/African American-identified participants included in any of the study samples among the reviewed articles. For instance, in Arena et al.'s exploration of psychosocial responses to breast cancer treatment comparing 39 heterosexual women and 39 lesbian women, the sample only included 7 Black-identified women, with 1 Black lesbian.23 In the Boston Lesbian Health Project, which provided data for several studies, there were 46 Black participants out of the 1,139-person sample, making up 4.1% of the sample.24 In a more recent (2014) study of 211 breast cancer survivors in which sexual minority women had higher perceived stress levels than heterosexual women, there was only 1 Black heterosexual and 1 Black sexual minority woman.25 The largest study contributing data on Black/African American women is the Nurses' Health Study II examination in breast cancer screening by sexual orientation, which included 5,145 observations.26 While the number of observations from this population is quite large, observations contributed by Black/African American women represent only 1.5% of the total observations (5,145 of the 360,171) in this prospective cohort. This is compared with 13.7% of women who are Black/African American in the United States.27 Moreover, the authors did not disaggregate the sexual minority women by race in the study results; thus, it is unclear how many women in the study identified as both Black/African American and sexual minority. The scarcity of Black/African American sexual minority women among these studies and throughout the literature presents a concern for addressing gaps in breast cancer screening and care in this population.

Higher prevalence of behavioral risk factors among sexual minority women

One-third of the articles (5 of the 15) explicitly investigated sexual minority women and breast cancer behavioral risk factors, such as nulliparity, lower oral contraceptive use, higher alcohol use, and higher prevalence of smoking. The sample sizes of Black women were low, and the studies did not have enough statistical power to detect notable differences stratified by race.

A Boston retrospective cohort study analyzing breast cancer risk factors highlighted that sexual minority women were more likely to be nulliparous, which is a known risk factor for breast cancer.28 The study had a total sample of 423 women and included 162 sexual minority women, among whom 13 were Black identified. The study noted that sexual minority women had a lower prevalence of birth control pill usage and used them for shorter durations compared with heterosexual women.

In addition, Cochran et al. compiled seven survey samples comprised primarily of lesbian and/or bisexually identified women (N = 11,867): (refer to Table 1), and compared prevalence of behavioral risk factors for breast and gynecological cancers between sexual minority women and the general female population.13 The study found that compared with the general, female U.S. population, sexual minority women had higher rates of obesity, alcohol use, and tobacco use as well as lower rates of parity and oral contraceptive use. These women were also less likely to have a recent mammogram and gynecological examination.

Some studies found conflicting evidence for higher prevalence of risk factors among sexual minority women. For instance, a study based in Missouri found no significant differences in cancer screenings between sexual minority and heterosexual women.3 However, this study did find that specifically lesbian women were more likely to report smoking and obesity compared with bisexual and heterosexual women.

The Boston Lesbian Health Project noted that there was a higher prevalence of healthy behaviors in lesbian women compared with the general population, such as higher utilization of mammographic screening for women >50.24 However, the article notes that lesbian women had a high rate of heavy drinking, which was defined as having more than two drinks a day either regularly or sometimes.24 In addition, the second installment of the project—the Boston Lesbian Health Project II—noted that a majority of women did not smoke, had diets high in fruits and vegetables, and consumed moderate alcohol.29

The risk factors that have been identified among sexual minority women (e.g., higher rates of obesity, higher alcohol consumption, nulliparity, etc.) put them at greater risk of breast cancer; however, whether the behavioral risk factors assessed are different among Black sexual minority women has yet to be explored. Yet, it is important to note that Black women in general are more likely to be obese and have lower alcohol consumption30,31; thus, they may experience competing or compounding risk factors compared with non-Black sexual minority women.

Engagement in breast cancer screening: sexual minority women

Breast cancer screenings: mammography and self-examination

Over half of the articles (8 of 15) examined prevalence of breast cancer screening through mammography and/or self-examination. Of these articles, four reported that sexual minority women had a lower prevalence of mammogram screening or a recent mammogram screening (within the last 2 years of the study). Two of the articles reported no statistically significant difference between heterosexual and sexual minority women in mammogram screening, and two articles reported the prevalence of breast cancer screening among sexual minority women but did not have a comparison group of heterosexual women to determine if screening practices were higher or lower than expected.

Cochran et al. found that lesbian and bisexual women were less likely to undergo mammogram and gynecological examinations, and that this was influenced by negative health care experiences as well as mistrust in the medical community.13 Furthermore, there were two other articles concerning the Boston Lesbian Health Project with results from 2004 to 2007.28,32 The 2004 results reported that women in this sample had mammogram rates that were lower than recommended, while the 2007 results showed an increase in mammogram usage that was on par with recommendations; however, there were still low levels of adhering to self-breast examination guidelines.

Social factors as risk factors for missing screening

Four of the 15 articles analyzed the role of social factors as risk factors for sexual minority women and breast cancer screenings. A study in North Carolina noted that mammography and breast self-evaluation are associated with sociodemographic characteristics, including older age, White race, access to health insurance, and higher income.33 Investigators noted that women with higher education and incomes were more likely to report breast self-examination. In addition, 86% of women age ≥40 reported having mammograms. Barriers to mammography costs included lack of awareness of one's risk, no health insurance, and concerns about radiation.

Disengagement in treatment driven by homophobia among health care providers

Over a third (6 of 15) of the articles discussed negative interactions among sexual minority women with their health care providers in relation to breast cancer treatment. For instance, Matthews et al.'s qualitative study among 13 lesbians and 28 heterosexual women who had been treated for breast cancer within the previous 5 years reported that lesbian participants discussed lower satisfaction with physicians as well as higher stress levels and lower emotional support during treatment.

In DeHart et al., researchers found that perceived heterosexism and homophobia among health care providers significantly contributed to participants' increased usage of self-breast examination, avoidance in visiting health care providers, or increased usage of complementary/alternative care (i.e., self-care, vitamins, meditation, etc. rather than traditional medical care). This was done by using the Health Belief Model (a model used to predict the health behaviors of individuals based on their attitudes and beliefs) on a sample of 130 homosexual women.34

There were two articles by Boehmer et al. that discussed the role of social support and coping when navigating breast cancer. In a qualitative cross-sectional study of 30 women with breast cancer, results suggest that women who have individuals providing social or physical support throughout diagnosis and treatment (support provider) were more likely to be open with their health care providers concerning their sexuality. However, there were no significant differences in coping styles, illness, or demographics between women with a support provider and women without one.32 Another analysis used two cross-sectional studies to measure the role of social support and distress in fostering a “fighting spirit” to conquer breast cancer among sexual minority women.32 The authors defined “fighting spirit” as possessing positive coping abilities, and this was measured by subscales of helplessness-hopelessness, anxious preoccupation, fatalism, and cognitive avoidance. Social support was positively associated with “fighting spirit,” while distress was negatively associated with “fighting spirit.”32 This implies that social support can positively impact one's ability to cope with seeking breast cancer care.

Some studies in our sample also explored the topic of patient comfort with disclosing their sexual orientation with health care providers. Among sexual minority women breast cancer patients, those with significant others were more likely to disclose to their provider.32 In addition, Roberts et al. reported that lesbians in later iterations of the Boston Lesbian Health Project were more likely to have disclosed their sexuality to their health care provider compared with previous samples.35 Also, older participants were more likely to have disclosed their sexuality to health care providers compared with younger participants.35

Survivorship and stress among sexual minority women

Jabson and Bowen explored whether social factors, such as sexual orientation and age, were associated with perceived stress in survivorship experiences among a sample of breast cancer survivors. Heterosexual breast cancer survivors reported less perceived stress than sexual minority breast cancer survivors.25

Discussion

Our findings indicate that Black/African American women are under-represented in the literature pertaining to breast cancer care and screening among sexual minority women. Although all of the studies included in our sample included Black/African American participants, the findings from these studies were not generalizable to these participants since Black/African American women comprised of such a small fraction of the sample sizes. For instance, it is unclear whether the behavioral risk factors found in the studies are risk factors for Black-identified sexual minority women. The lack of representation of Black sexual minority women across all studies reaffirms the inattention to intersectionality in research on breast cancer screening and care in marginalized populations.

Researchers should devote future studies on investigating breast cancer risk factors and behavioral or psychosocial factors specific to Black-identified sexual minority women that influence breast cancer treatment. Furthermore, the lack of inclusion of Black sexual minority participants in breast cancer research may be linked to the mistrust of the medical community from Black sexual minority women that stems from the intersection of potential homophobia and racism among health care providers. Higher levels of health care system mistrust and experiences of racial discrimination from health care providers among the Black community have already been documented, particularly concerning cancer treatment and care.36–38 This mistrust in addition to reports of homophobia and discrimination experienced by sexual minority women in the health care setting suggest overlapping concerns of discrimination for women who are both racial and sexual minorities. In addition, national breast cancer organizations may not be welcoming to Black and sexual minority women as well as women at the intersection of these identities, and Black organizations may still be less welcoming to sexual minority women.39 This, in turn, perpetuates unsupportive spaces for Black sexual minority women in the breast cancer care continuum.

Behavioral risk factors

In this scoping review, the current literature supports the notion that sexual minority women possess higher risk factors for breast cancer compared with heterosexual women, including more alcohol use, smoking, lower oral contraceptive use, higher nulliparity as well as potentially higher risk of breast cancer mortality with less frequent breast cancer screenings. However, the findings of behavioral risk factors among the articles in our review were inconsistent with regard to alcohol consumption and diets as the Boston Lesbian Health Project II reports sexual minority women having moderate alcohol consumption and higher intake of fruits and vegetables.

Breast cancer screening

Breast cancer screening via mammography was an overwhelming focus of the breast cancer care continuum. Understanding the experiences of racial and sexual minority women by other forms of screening such as magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasound, or screening biopsies can be helpful to identify what factors influence lack of follow-up or lack of screening utilization among this group. Of note, the latest screening recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) to delay initial screenings until the age of ≥50 and increase the time interval between screenings are not always reflected in the articles found in this scoping review.

The USPSTF recommendations are based on results from two systematic reviews of breast cancer screening trials showing a diminished benefit in survivorship for mammogram screenings among younger women.40 However, the studies informing these reviews included predominantly White samples that were not targeted toward sexual minority women.40 This is concerning as USPSTF guidelines to start screening at age 50 are for women at average risk. If there is evidence that Black and sexual minority women are at higher risk, then there may be a need for alternative screening schedules for these marginalized groups.41,42

A better understanding of screening practices among racial and sexual minority women is needed as existing studies may not generalize to this under-represented population. Only one study included in the review34 used a theory to inform research. This may be due to the fact that many of the studies were aimed at surveillance of risk factors among sexual minority groups rather than intervention or collecting survey data. This signals a need for researchers to use theory that can better guide research questions and study designs that may help address racial and sexuality disparities in breast cancer care among women. Studies in this review also captured what was lacking among sexual minority women in relation to the breast cancer care continuum (i.e., lower prevalence of screening) rather than investigating potential factors that may work well among this population to improve the breast cancer prevention and care continuum.

Breast cancer treatment and survivorship

Based on the findings of this scoping review, there is also a need for further exploration of psychosocial factors associated with breast cancer screening and treatment among sexual minority women. Four of the 15 articles included a psychosocial factor as a primary focus in their research question concerning breast cancer risks, treatment, or survivorship, including coping with breast cancer, social support during breast cancer treatment, and perceived stress among survivors. However, there was no in-depth investigation into stigma and discrimination throughout the breast cancer care continuum that may be specific to racial and sexual minority women.

Although there were several studies that mentioned perceived heterosexism and homophobia in the interactions participants had with health care providers, these studies did not provide detailed information regarding how these interactions influence the decision making of sexual minority women concerning breast cancer care. Furthermore, levels of comfort among sexual minority women with disclosing their sexuality to health care providers when engaging in breast cancer screening and care—or whether this disclosure would improve health outcomes—are still not well documented in the literature.34

In a recent systematic review, the authors examine the facilitators and barriers of sexual orientation disclosure and the adverse effects of nondisclosure.43 However, the review is limited in offering critical insight regarding sexual orientation disclosure to health care professionals for Black sexual minority women.43 In addition, an intersectional examination of how psychosocial stressors relevant to Black/African American sexual minority women, including the combined experience of racism and homophobia in and outside the health care setting, may increase adverse outcomes in breast cancer screening and care.

There is emerging literature exploring how to incorporate intersectional theory into research concerning populations facing multiple minority statuses.44 Such tools should be applied in the research of breast cancer care among Black sexual minority women.

Future directions

A greater variety of study designs addressing the experiences of sexual minority women in the breast cancer care continuum would be of benefit. For instance, most of the studies included in the review were cross-sectional. Prospective cohort studies comparing experiences of White heterosexuals, White sexual minorities, Black heterosexuals, and Black sexual minorities would complement the existing literature by capturing potential effects of joint marginality among Black sexual minority women over time. Furthermore, studies concerning intervention implementation, such as clinical trials, with a sufficient number of Black and sexual minority participants could examine potential interactions between racial and/or sexual minority status on breast cancer treatment intervention outcomes.6,45–49

A limitation with this scoping review is that it is possible that the types and intensity of stigma and discrimination toward sexual minority women have changed over time in ways that may not be reflected in this review where the majority of the articles were published in the early to mid 2000s. Thus, this scoping review is unable to determine whether health providers' attitudes toward sexual minority women may be changing, and if so, how such changes may affect sexual minority women's experiences within the breast cancer continuum. Research to determine whether such stigma and discrimination have changed over time for Black and sexual minority women in the health care setting should be continued.

Conclusions

Overall, further investigation is warranted to capture the dynamics of the breast cancer care continuum among racial and sexual minority women. The current scoping review provides a brief analysis of the breadth of the literature pertaining to breast cancer screening and care among sexual minority women, and identifies areas for further research. Researchers in the field of breast cancer screening and care should strive to conduct racially and sexually inclusive research that can inform tailored interventions that address racial and sexual breast cancer disparities.

Acknowledgments

Jowanna Malone's effort on this work was supported by the HIV Epidemiology and Prevention Sciences Training Program grant 2T32AI102623-06. Lorraine T. Dean's effort on this work was supported by the National Cancer Institute grant K01CA184288; the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center grant P30CA006973; the National Institute of Mental Health grant R25MH083620; and the Johns Hopkins University Center for AIDS Research grant P30AI094189.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Cancer facts & figures 2017. Updated 2017. Available at: https://search.proquest.com/docview/1861301998 Accessed April10, 2018

- 2. Matthews AK. Breast and cervical cancer screening behaviors of African American sexual minority women. J Gen Pract 2013;1:1–8 [Google Scholar]

- 3. McElroy JA, Wintemberg JJ, Williams A. Comparison of lesbian and bisexual women to heterosexual women's screening prevalence for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer in missouri. LGBT Health 2015;2:188–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meads C, Moore D. Breast cancer in lesbians and bisexual women: Systematic review of incidence, prevalence and risk studies. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Newman LA. Breast cancer disparities: High-risk breast cancer and African ancestry. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2014;23:579–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mayer KH, Bradford JB, Makadon HJ, Stall R, Goldhammer H, Landers S. Sexual and gender minority health: What we know and what needs to be done. Am J Public Health 2008;98:989–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McCarthy AM, Kim JJ, Beaber EF, et al. Follow-up of abnormal breast and colorectal cancer screening by race/ethnicity. Am J Prev Med 2016;51:507–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gorin SS, Heck JE, Cheng B, Smith SJ. Delays in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment by racial/ethnic group. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:2244–2252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Warner E, Tamimi R, Hughes M, et al. Time to diagnosis and breast cancer stage by race/ethnicity. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;136:813–821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cancer facts & figures for African Americans 2016–2018. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Selove R, Kilbourne B, Fadden MK, et al. Time from screening mammography to biopsy and from biopsy to breast cancer treatment among black and white, women Medicare beneficiaries not participating in an health maintenance organization. Womens Health Issues 2016;26:642–647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities, Board on the Health of Select Populations, Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington: National Academies Press, 2011. Available at: http://lib.myilibrary.com?ID=321342 Accessed April10, 2018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cochran SD, Mays VM, Bowen D, et al. Cancer-related risk indicators and preventive screening behaviors among lesbians and bisexual women. Am J Public Health 2001;91:591–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lacombe-Duncan A, Logie CH. Correlates of clinical breast examination among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer women. Can J Public Health 2016;107:E467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Clark MA, Bonacore L, Wright SJ, Armstrong G, Rakowski W. The cancer screening project for women: Experiences of women who partner with women and women who partner with men. Women Health 2003;38:19–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brown JP, Tracy JK. Lesbians and cancer: An overlooked health disparity. Cancer Causes Control 2008;19:1009–1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hart SL, Bowen DJ. Sexual orientation and intentions to obtain breast cancer screening. J Womens Health 2009;18:177–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Damaskos P, Amaya B, Gordan R, Walters CB. Intersectionality and the LGBT cancer patient. Semin Oncol Nurs 2018;34:30–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Washington TA, Murray JP. Practice notes: Breast cancer prevention strategies for aged black lesbian women. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv 2006;18:89–96 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khalil H, Peters M, Godfrey CM, McInerney P, Soares CB, Parker D. An evidence-based approach to scoping reviews. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2016;13:118–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Klemp JR. Breast cancer prevention across the cancer care continuum. Semin Oncol Nurs 2015;31:89–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arena PL, Carver CS, Antoni MH, Weiss S, Ironson G, Durán RE. Psychosocial responses to treatment for breast cancer among lesbian and heterosexual women. Women Health 2007;44:81–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roberts SJ, Sorensen L. Health related behaviors and cancer screening of lesbians: Results from the Boston lesbian health project. Women Health 1999;28:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jabson JM, Bowen DJ. Perceived stress and sexual orientation among breast cancer survivors. J Homosex 2014;61:889–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Austin SB, Pazaris MJ, Nichols LP, Bowen D, Wei EK, Spiegelman D. An examination of sexual orientation group patterns in mammographic and colorectal screening in a cohort of U.S. women. Cancer Causes Control 2013;24:539–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. U.S. Census Bureau. “Table 4. Projected Race and Hispanic Origin” 2017 National Population Projections Tables. 2018. Available at: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/demo/popproj/2017-summary-tables.html Accessed April10, 2018

- 28. Clavelle K, King D, Bazzi AR, Fein-Zachary V, Potter J. Breast cancer risk in sexual minority women during routine screening at an urban LGBT health center. Womens Health Issues 2015;25:341–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Grindel CG, McGehee LA, Patsdaughter CA, Roberts SJ. Cancer prevention and screening behaviors in lesbians. Women Health 2006;44:15–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Obesity and African Americans. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Office of Minority Health. 2017

- 31. Chartier K, Caetano R. Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Res Health 2010;33:152. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Boehmer U, Freund KM, Linde R. Support providers of sexual minority women with breast cancer. J Psychosom Res 2005a;59:307–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rankow EJ, Tessaro I. Mammography and risk factors for breast cancer in lesbian and bisexual women. Am J Health Behav 1998;22:403–410 [Google Scholar]

- 34. DeHart DD. Breast health behavior among lesbians: The role of health beliefs, heterosexism, and homophobia. Women Health 2008;48:409–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Roberts SJ, Patsdaughter CA, Grindel CG, Tarmina MS. Health related behaviors and cancer screening of lesbians: Results of the Boston lesbian health project II. Women Health 2004;39:41–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Armstrong K, McMurphy S, Dean L, et al. Differences in the patterns of health care system distrust between blacks and whites. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:827–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Armstrong K, Putt M, Halbert C, et al. Prior experiences of racial discrimination and racial differences in health care system distrust. Med Care 2013;51:144–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dean Lorraine T, Moss Shadiya L, McCarthy AM, Armstrong K. Healthcare system distrust, physician trust, and patient discordance with adjuvant breast cancer treatment recommendations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2017;26:1745–1752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Johnson LSP, McElroy J. Rainbows or Ribbons? Queer Black Women Searching for a Place in the Cancer Sisterhood. In: Follins LD, Lassiter J, eds. Black LGBT Health in the United States: The intersection of race, gender, and sexual orientation. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2017;pp.103–120 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Siu AL. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dean LT, Gehlert S, Neuhouser ML, et al. Social factors matter in cancer risk and survivorship. Cancer Causes Control 2018;29:611–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stapleton SM, Oseni TO, Bababekov YJ, Hung Y-C, Chang DC. Race/ethnicity and age distribution of breast cancer diagnosis in the United States. JAMA Surg 2018;153:594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brooks H, Llewellyn CD, Nadarzynski T, et al. Sexual orientation disclosure in health care: A systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2018;68:e187–e196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bauer GR. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Soc Sci Med 2014;110:10–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials. JAMA 2004;291:2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Oh SS, Galanter J, Thakur N, et al. Diversity in clinical and biomedical research: A promise yet to be fulfilled. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vickers SM, Fouad MN. An overview of EMPaCT and fundamental issues affecting minority participation in cancer clinical trials: Enhancing minority participation in clinical trials (EMPaCT): Laying the groundwork for improving minority clinical trial accrual. Cancer 2014;120:1087–1090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mitchell KW, Carey LA, Peppercorn J. Reporting of race and ethnicity in breast cancer research: Room for improvement. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;118:511–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fisher CB, Mustanski B. Reducing health disparities and enhancing the responsible conduct of research involving LGBT youth. Hastings Cent Rep 2014;44 Suppl 4:S28–S31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Boehmer U, Linde R, Freund KM. Breast reconstruction following mastectomy for breast cancer: The decisions of sexual minority women. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;119:464–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Boehmer U, Linde R, Freund KM. Sexual minority women's coping and psychological adjustment after a diagnosis of breast cancer. J Womens Health 2005b;14:214–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]