Abstract

Background: Symptoms associated with midline lymphedema are not fully understood and it is unclear if symptoms associated with swelling in the head and neck are similar to those associated with swelling in the truncal region of the body.

Objectives: Describe symptoms experienced by those with head and neck and truncal lymphedema. Compare symptom presence, intensity, and distress among those two groups and participants with no lymphedema.

Methods: Cross-sectional descriptive study administered by online survey.

Results: Nonlymphedema participants were younger than the lymphedema groups. Those with truncal lymphedema took more diuretic medications than the other groups. Participants with truncal lymphedema experienced a greater number of symptoms than the other groups (p < 0.001). These symptoms were also more severe and intense (p < 0.001). Fourteen symptoms distinguished the truncal group from the other two groups (p < 0.001). Nine symptoms differentiated the head and neck group from the other groups (p < 0.001).

Conclusion: These preliminary findings support that symptom profiles differ among those with lymphedema and those without lymphedema. The number, type, severity, and intensity of symptoms vary based upon the location of lymphedema. The need to use two lymphedema anatomical classifications (head and neck and truncal) instead of one classification (midline) when assessing lymphedema-related symptoms is also supported.

Keywords: head and neck cancer, lymphedema, symptoms, midline, truncal

Introduction

Lymphedema, a chronic swelling condition,1 can be related to lymphatic abnormalities due to genetic mutations or triggered by injury to the lymphatic system. Regardless of the cause, lymphedema is a progressive, debilitating, and potentially painful condition that can be treated, but generally not cured.2 Lymphedema symptoms range from mild discomfort to debilitating, even life-threatening, obstruction.3–6

Lymphedema is commonly classified by stage or severity.1 There is also a general, but inconsistent, trend to classify lymphedema based on the affected body part. While classification by limb or genitalia is typical, whether and how to identify swelling in nonlimb structures such as the ipsilateral quadrant of the trunk, breast, head, or neck differ by source.1,2,6 Viehoff et al.6 classified all nonlimb lymphedema cases as midline (including head, neck, and thorax), but divided midline into head and neck and genital in their analysis. While formal anatomical classification of lymphedema remains inconsistent, it is generally acknowledged that treatment of lymphedema is unique based on the anatomical region.1,2

Upper and lower limb lymphedema cases are extensively addressed in existing literature and acknowledged as highly prevalent in certain patient populations.1,2,7 In contrast, multiple sources comment on the rarity of midline lymphedema.1,2,7 There is reason to think that midline lymphedema, as defined by Viehoff et al.,6 may be an under-reported condition, including recent work in the head and cancer population. A longitudinal single-site study of (N = 83) head and neck cancer patients before treatment and for 18 months after treatment revealed that 91.6% of these patients experienced late-effect (≥3 months post-treatment) external lymphedema and 95.1% experienced late-effect internal swelling.8 A descriptive survey study (N = 213) of participants with lower limb lymphedema, indicated by Rockson et al.2 to be the most common type of lymphedema, found that 41.5% of participants also experienced swelling in the abdomen, back, or groin.9 These studies only represent a portion of what would be considered midline lymphedema, but the higher than expected prevalence indicates that midline lymphedema may be less recognized, a likely contributing factor to the lack of information about the patient experience. Because of this lack of visibility, initial descriptive studies must extend to multiple clinical settings and/or to at-large general communities to obtain reasonable sample sizes.

Viehoff et al.'s6 findings suggest that the possible variations in symptom profiles based upon the affected area of the body warrant further examination. Thus, presentation of symptoms may or may not support defining midline lymphedema as occurring in both the head and neck and thorax.

To address current gaps in knowledge regarding the presence and burden of distinguishing symptoms in patients with midline lymphedema, a web-based descriptive study was undertaken to generate preliminary data from individuals who self-report swelling in the midline region of their body. The purpose of the study was to compare symptom presence, intensity, and distress among participants with head and neck lymphedema, truncal lymphedema, and no lymphedema.

Methods

Design and ethical considerations

A cross-sectional, comparative descriptive study was conducted through online survey. Groups included individuals with self-reported head and neck lymphedema, self-reported truncal lymphedema, and self-reported absence of lymphedema in any area of the body. Institutional review board approval was obtained from Vanderbilt University. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before data collection.

Participants

Multiple recruitment methods were engaged during the conduct of the study. Participants in an IRB-approved registry were contacted and ResearchMatch (www.researchmatch.org/about) notifications were sent. Social media, web site, and flyer postings were facilitated by community entities: Lymphedema Products and Lymphedema Community, Norton School of Lymphatic Therapy, Lymphatic Education & Research Network, Gilda's Club, The Komen Connection, Lymphedema Guru, and numerous health care professionals.

A public screening survey link was disseminated by e-mail blast, online posting, and social media sharing, as well as paper flyers distributed to local lymphedema clinics with a brief study description. Potential participants were able to click the link or scan the associated QR code to complete the brief screening survey and provide a current e-mail address and phone number so that study staff could contact them for eligibility determination and answer any questions before enrollment. Participants were given an e-mail address and phone number of study staff and the Principal Investigator should they have questions or concerns. eConsent links were sent to eligible participants who provided a valid e-mail address. Participants who provided electronic consent were e-mailed a link to the study surveys. Screening, eConsent, and data collection utilized REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies.10

Data collection

Most of the data collection for this study occurred electronically using REDCap surveys, but paper surveys were available by request. Data collected electronically directly from participants were evaluated for missing, inconsistent, or invalid responses. Any data collected on paper were double entered into the REDCap database. Data comparison was conducted on all hard copy data entry forms and all discrepancies were adjudicated.

Instruments

Demographics

A 10-item self-report form, including questions about gender, race/ethnicity, marital and employment status, insurance, and income, was used.

Health and Lymphedema Form

A 7-item self-report form, including questions about medications, health conditions and surgeries, lymphedema diagnosis, type, cause, location, and treatment, was used.

Lymphedema Symptom Intensity and Distress Survey of symptoms

A self-report survey assessing the presence of a set of 48 symptoms was used. If a symptom was present, the participant was asked to complete a separate rating of symptom intensity and of distress, each on a 5-point scale. This initial set of 48 symptoms was derived from symptoms currently included in the Lymphedema Symptom Intensity and Distress Survey-Arm (LSIDS-A)11 and Lymphedema Symptom Intensity and Distress Survey-Lower Limb (LSIDS-L),12 as well as findings from work conducted by the team investigating symptoms in the head and neck cancer population.3,13

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24 (Armonk, NY). Frequency distributions were used to summarize the nominal and ordinal study data distributions, including Lymphedema Symptom Intensity and Distress Survey-Midline (LSIDS-M) symptom prevalence. Median and interquartile range (IQR) were used to summarize the continuous variables due to skewness of the distributions. Group comparisons were conducted using chi-square tests of independence for nominal and ordinal data. Mann–Whitney tests were used for continuous data.

Results

Sample characteristics

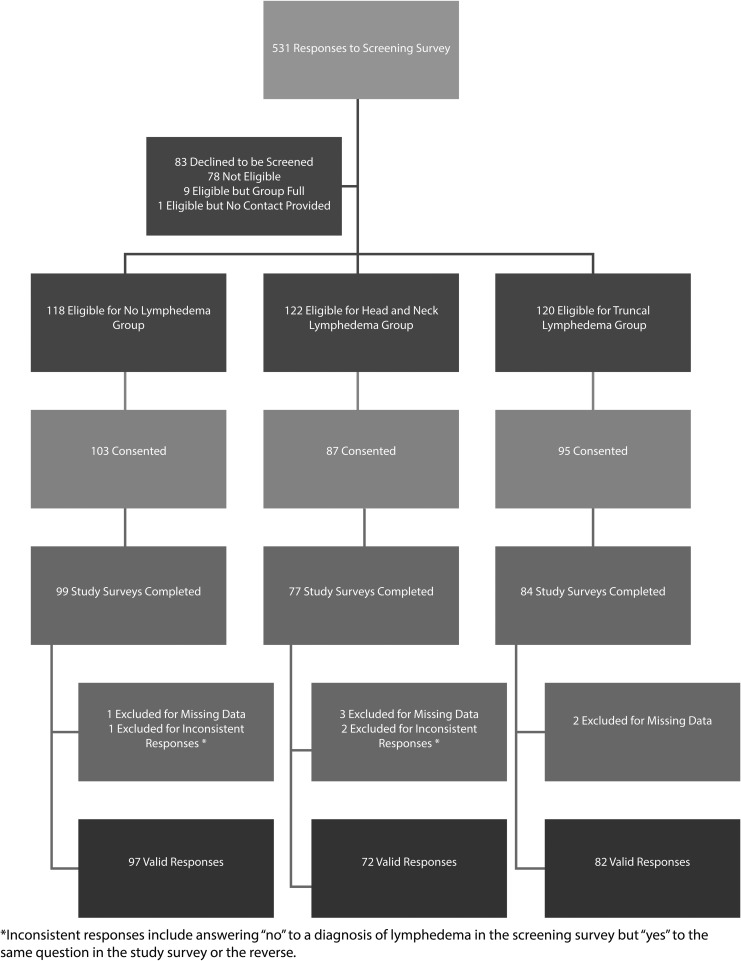

Five hundred thirty-one individuals responded to the screening survey (Fig. 1), of which 83 declined screening and 78 were ineligible. A total of 285 eligible participants provided informed consent, with 264 starting the study survey. Of those, 254 finished it with complete data, yielding a 96% completion rate. Three additional respondents were excluded due to inconsistent responses (i.e., claiming not to have lymphedema, then documenting a lymphedema diagnosis), resulting in a final N = 251. There were insufficient noncompleters to conduct an analysis of differences between those who did and did not complete the survey.

FIG. 1.

CONSORT diagram.

Summaries of the demographic characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1. Participants were primarily white (90.7%), non-Hispanic (97.1%), and married or partnered (69.1%). While the median age for all participants was 53.7 years (IQR = 44–63), the participants without lymphedema were statistically significantly younger than both groups with lymphedema (median = 45.1 years vs. median 58.5, p < 0.001). The participants without lymphedema had a higher rate of employment (81.4%) and a larger percentage with private insurance (80.4%) compared with those in the two lymphedema groups (employment = 40.3%, private insurance = 55.2%, p = 0.003). The group with head and neck lymphedema had a higher percentage of male participants (66.7%) than the group with no lymphedema (16.5%) and the group with truncal lymphedema (9.8%) (p < 0.001, see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics by Lymphedema Group (N = 251)

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 251) |

No lymphedema (N = 97) |

Head and neck lymphedema (N = 72) |

Truncal lymphedema (N = 82) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median [IQR] (N) | |||||

| Age, years | 53.7 [44–63] (238) | 45.1 [32–56] (95)a | 60.3 [50–66] (66)b | 55.8 [50–63] (77)b | <0.001 |

| Years of education | 15.7 [14–18] (251) | 17.0 [16–18] (97)a | 14.0 [12–16] (72)b | 16.0 [14–17] (82)c | <0.001 |

| N (%) | |||||

| Gender | <0.001 | ||||

| Female | 178 (70.9) | 80 (82.5)a | 24 (33.3)b | 74 (90.2)a | |

| Male | 72 (28.7) | 16 (16.5)a | 48 (66.7)b | 8 (9.8)a | |

| Other | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Race | N = 248 | N = 96 | N = 71 | N = 81 | 0.667 |

| Black or African American | 13 (5.2) | 4 (4.2) | 5 (7.0) | 4 (4.9) | |

| White | 225 (90.7) | 90 (93.8) | 62 (87.3) | 73 (90.1) | |

| Other | 10 (4.0) | 2 (2.1) | 4 (5.6) | 4 (4.9) | |

| Ethnic category | N = 242 | N = 94 | N = 69 | N = 79 | 0.199 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 7 (2.9) | 5 (5.3) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 235 (97.1) | 89 (94.7) | 68 (98.6) | 78 (98.7) | |

| Relationship status | N = 249 | N = 71 | N = 81 | 0.195 | |

| Married/living with partner | 172 (69.1) | 69 (71.1) | 53 (74.6) | 50 (61.7) | |

| Single/widowed/other | 77 (30.9) | 28 (28.9) | 18 (25.4) | 31 (38.3) | |

| Employment status | <0.001 | ||||

| Employed full-/part-time | 152 (60.6) | 79 (81.4)a | 34 (47.2)b | 39 (47.6)b | |

| Not employed/other | 99 (39.4) | 18 (18.6)a | 38 (52.8)b | 43 (52.4)b | |

| Residence | 0.060 | ||||

| Urban | 92 (36.7) | 43 (44.3) | 24 (33.3) | 25 (30.5) | |

| Rural | 48 (19.1) | 15 (15.5) | 20 (27.8) | 13 (15.9) | |

| Suburban/Other | 111 (44.2) | 39 (40.2) | 28 (38.9) | 44 (53.7) | |

| Insurance | 0.003 | ||||

| None | 2 (0.8) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Government | 56 (22.3) | 12 (12.4)a | 18 (25.0)a,b | 26 (31.7)b | |

| Private | 163 (64.9) | 78 (80.4)a | 40 (55.6)b | 45 (54.9)b | |

| Multiple Types/Other | 30 (12.0) | 6 (6.2)a | 13 (18.1)b | 11 (13.4)a,b | |

| Annual household income | N = 234 | N = 92 | N = 63 | N = 79 | 0.121 |

| $30,000 or less | 45 (19.2) | 12 (13.0) | 13 (20.6) | 20 (25.3) | |

| Over $30,000 | 189 (80.8) | 80 (87.0) | 50 (79.4) | 59 (74.7) | |

For statistically significant comparisons, cells with superscripts indicate the specific differences using a Bonferroni-corrected p < 0.05. For example, ages of the patients without lymphedema (indicated by “a”) were statistically significantly younger than both of the other groups (indicated by “b”).

Bold values indicate statistically significant difference (p < 0.05).

IQR, interquartile range; N, number of responses.

Some differences were noted among the three groups in current use of medications and comorbid medical conditions (Table 2). Participants with truncal lymphedema were more likely to report taking diuretic medications compared with those with no lymphedema (17.1% vs. 5.2%, p = 0.007). Compared with the group with no lymphedema, a higher percentage of those with truncal lymphedema reported a history of cardiovascular, excretory, skeletal, endocrine, and immune conditions (p < 0.05). Furthermore, a higher percentage of those with truncal lymphedema reported a history of having some type of surgery compared with those in the other groups (95.1% vs. 81.9% head and neck, 67.0% none, p < 0.001). As would be expected, those with head and neck lymphedema reported more surgical procedures in that area than the other two groups; those with truncal lymphedema reported the highest percentage of truncal surgeries (both p < 0.001, see Table 2).

Table 2.

Self-Reported Clinical Characteristics by Lymphedema Group (N = 251)

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 251) |

No lymphedema (N = 97) |

Head and neck lymphedema (N = 72) |

Truncal lymphedema (N = 82) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | |||||

| Current medications | |||||

| Beta blockers | 22 (8.8) | 7 (7.2) | 8 (11.1) | 7 (8.5) | 0.075 |

| Diuretics | 23 (9.2) | 5 (5.2)a | 4 (5.6)a,b | 14 (17.1)b | 0.007 |

| Oral steroids | 10 (4.0) | 3 (3.1) | 5 (6.9) | 2 (2.4) | 0.295 |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories | 100 (39.8) | 32 (33.0) | 27 (37.5) | 41 (50.0) | 0.099 |

| History of conditions | |||||

| Cardiovascular | 86 (34.3) | 17 (17.5)a | 40 (55.6)b | 29 (35.4)c | <0.001 |

| Excretory | 21 (8.4) | 4 (4.1)a | 4 (5.6)a,b | 13 (15.9)b | 0.011 |

| Digestive | 86 (34.3) | 28 (28.9) | 28 (38.9) | 30 (36.6) | 0.344 |

| Respiratory | 44 (17.5) | 16 (16.5) | 12 (16.7) | 16 (19.5) | 0.847 |

| Integumentary | 63 (25.1) | 20 (20.6) | 16 (22.2) | 27 (32.9) | 0.134 |

| Nervous | 30 (12.0) | 9 (9.3) | 7 (9.7) | 14 (17.1) | 0.218 |

| Skeletal | 79 (31.5) | 23 (23.7)a | 17 (23.6)a | 39 (47.6)b | 0.001 |

| Muscular | 5 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.8) | 3 (3.7) | 0.186 |

| Endocrine | 78 (31.1) | 17 (17.5)a | 29 (40.3)b | 32 (39.0)b | 0.001 |

| Immune | 56 (22.3) | 16 (16.5)a | 10 (13.9)a | 30 (36.6)b | 0.001 |

| History of any surgery | 202 (80.5) | 65 (67.0)a | 59 (81.9)a | 78 (95.1)b | <0.001 |

| History of surgery involving | |||||

| Head and/or neck | 67 (33.2) | 16 (24.6)a | 44 (74.6)b | 7 (9.0)c | <0.001 |

| Shoulder(s) | 26 (12.9) | 9 (13.8) | 10 (16.9) | 7 (9.0) | 0.370 |

| Trunk | 122 (60.4) | 29 (44.6)a | 27 (45.8)a | 66 (84.6)b | <0.001 |

| Limb(s) | 57 (22.7) | 14 (14.4) | 20 (27.8) | 23 (28.0) | 0.046 |

| Type of lymphedema | N = 154 | — | 0.002 | ||

| Unknown | 43 (27.9) | — | 30 (41.7)a | 13 (15.9)b | |

| Primary | 15 (9.7) | — | 6 (8.3) | 9 (11.0) | |

| Secondary | 96 (62.3) | — | 36 (50.0)a | 60 (73.2)b | |

| Cancer | 80 (83.3) | — | 33 (91.7) | 47 (78.3) | 0.090 |

| Other/unknown | 16 (16.7) | — | 3 (8.3) | 13 (21.7) | |

| Swelling locations | N = 142 | — | N = 60 | N = 82 | |

| Head/face | 28 (19.7) | — | 26 (43.3) | 2 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| Along jaw/chin | 31 (21.8) | — | 29 (48.3) | 2 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| Under jaw/chin | 46 (32.4) | — | 43 (71.7) | 3 (3.7) | <0.001 |

| Neck | 46 (32.4) | — | 40 (66.7) | 6 (7.3) | <0.001 |

| Shoulder(s) | 27 (19.0) | — | 9 (15.0) | 18 (22.0) | 0.297 |

| Chest/breast(s) | 53 (34.4) | — | 4 (5.6) | 49 (59.8) | <0.001 |

| Back | 35 (24.6) | — | 2 (3.3) | 33 (40.2) | <0.001 |

| Abdomen | 48 (33.8) | — | 0 (0.0) | 48 (58.5) | <0.001 |

| Groin/genitals | 31 (21.8) | — | 0 (0.0) | 31 (37.8) | <0.001 |

| Arm(s) | 44 (31.0) | — | 4 (6.7) | 40 (48.8) | <0.001 |

| Leg(s) | 41 (28.9) | — | 2 (3.3) | 39 (47.6) | <0.001 |

| Other* | 13 (9.2) | — | 2 (3.3) | 11 (13.4) | 0.040 |

| Initial treatment | 115 (81.0) | — | 48 (80.0) | 67 (81.7) | 0.798 |

| Complex decongestive therapy | 85 (73.9) | — | 30 (62.5) | 55 (82.1) | 0.018 |

| Compression garment | 74 (64.3) | — | 24 (50.0) | 50 (74.6) | 0.007 |

| Elevation | 32 (27.8) | — | 8 (16.7) | 24 (35.8) | 0.024 |

| Other** | 50 (43.5) | — | 18 (37.5) | 32 (47.8) | 0.274 |

| Median [IQR] (N) | |||||

| Months since initial treatment | 21.9 [7–51] (113) | — | 11.7 [2–24] (47) | 35.1 [14–63] (66) | <0.001 |

| N (%) | |||||

| Current treatment | 73 (51.4) | — | 20 (33.3) | 53 (64.6) | <0.001 |

| Compression garment | 56 (76.7) | — | 10 (50.0) | 46 (86.8) | 0.001 |

| Self-massage | 50 (68.5) | — | 13 (65.0) | 37 (69.8) | 0.693 |

| Complex decongestive therapy | 27 (37.0) | — | 9 (45.0) | 18 (34.0) | 0.384 |

| Elevation | 25 (34.2) | 4 (20.0) | 21 (39.6) | 0.115 | |

| Pump | 22 (30.1) | — | 2 (10.0) | 20 (37.7) | 0.021 |

| Other*** | 65 (89.0) | — | 15 (75.0) | 50 (94.3) | 0.018 |

For statistically significant comparisons of >2 groups, cells with superscripts indicate specific differences using a Bonferroni-corrected p < 0.05. For example, the group without lymphedema had lower reports of a history of cardiovascular conditions (indicated by “a”) than did the group with truncal lymphedema (indicated by “c”), which in turn had lower reports than the group with head/neck lymphedema (indicated by “b”).

Other locations included the tongue, under the ear, hip(s), arm pit/underarm area, hand(s), feet, intestines, buttock(s), and toes.

Other initial treatments included pump, medication, myofascial release, massage therapy, physical therapy, surgery, kinesiotaping, binding/bandaging/wrapping, and herbal supplements.

Other current treatments included surgery, medication, night bandaging, exercise, skin care, bandaging, massage, Juzo garments, physical therapy, ice, vibration, diet, skin brushing, Tribute garment, Reid sleeve, and pool therapy.

Bold values indicate statistically significant difference (p < 0.05).

Types and locations of lymphedema and swelling, as well as summaries of initial and current treatments for the two groups with lymphedema, are also summarized in Table 2. Of those with head and neck lymphedema, 41.7% reported unknown type, while an overwhelming majority (73.2%) of those with truncal lymphedema reported secondary type (p = 0.002). As expected, self-reported specific locations of swelling differed between the groups with locations reported being consistent with the more global lymphedema designations (head/neck or truncal).

Approximately 80% of all participants with lymphedema had received some type of lymphedema treatment. Those with truncal lymphedema reported a longer period of time since initial treatment than those with head/neck (median 35 months vs. 12 months, respectively, p < 0.001). Furthermore, a higher percentage of those with truncal lymphedema reported complex decongestive therapy (82.1%), compression garment (74.6%), and elevation (35.8%) for that initial treatment than those with head/neck lymphedema (62.5%, 50.0%, and 16.7%, respectively, p < 0.05, see Table 2). In terms of current treatment, again a higher percentage of those with truncal lymphedema reported currently undergoing treatment (64.6%), using a compression garment (86.8%), and using a pump (37.7%) than those with head/neck lymphedema (33.3%, 50.0%, and 10.0%, respectively, p < 0.05, see Table 2).

Symptoms

Not only did participants with no lymphedema report very few symptoms compared with those with lymphedema, but also participants with truncal lymphedema reported higher numbers of symptoms and generally higher levels of intensity and distress from symptoms. Of respondents without lymphedema, only two symptoms were endorsed by more than half: fatigue (55.7%) and appearance concerns (51.5%). Only seven symptoms were reported by more than 50% of head and neck respondents, with none being reported by more than 75% of that group: fatigue (65.3%), swelling (63.9%), difficulty swallowing solids (63.9%), tightness (62.5%), difficulty moving the head or neck (52.8%), hardness (51.4%), and taste changes (51.4%).

In contrast,19 symptoms were reported by more than 50% of truncal lymphedema respondents, with five of those reported by more than 75% of that group: heaviness (91.5%), swelling (90.2%), fatigue (86.6%), appearance concerns (76.8%), feeling less sexually attractive (75.6%), loss of body confidence (73.2%), difficulty sleeping (72.0%), impaired hobbies (68.3%), decreased social and physical activities (56.1% and 69.5%), tightness (68.3%), pain (59.8%), lack of interest in sex (57.3%), feeling irritated (57.3%), decreased sexual activity (53.7%), sadness (53.7%), anxiety (53.7%), achiness (52.4%), and lack of self-confidence (51.2%).

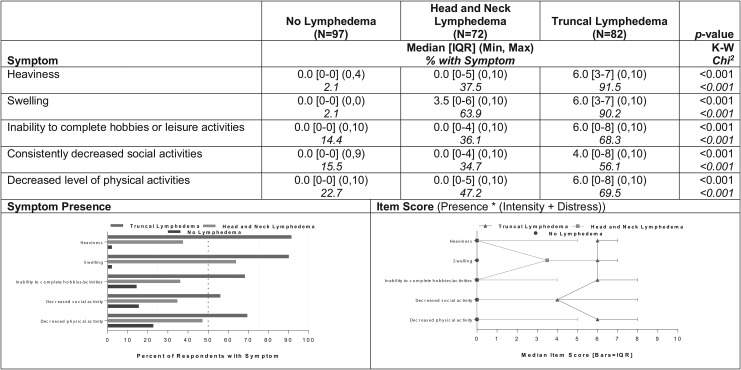

Five symptoms distinguished all three groups in terms of both prevalence and severity: heaviness, swelling, inability to complete hobbies or leisure activities, decreased social activities, and decreased physical activities (Fig. 2). A higher percentage of participants with truncal lymphedema reported each of these symptoms (56%–92%) than those with head and neck lymphedema (35%–64%). A maximum of 23% of participants without lymphedema reported any of these symptoms (p < 0.001). A corresponding pattern of differences was observed for the severity scores for those five symptoms among the three groups (p < 0.001, Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Summaries of prevalence and severity scores for symptoms with statistically significant differences among all three groups (N = 251).

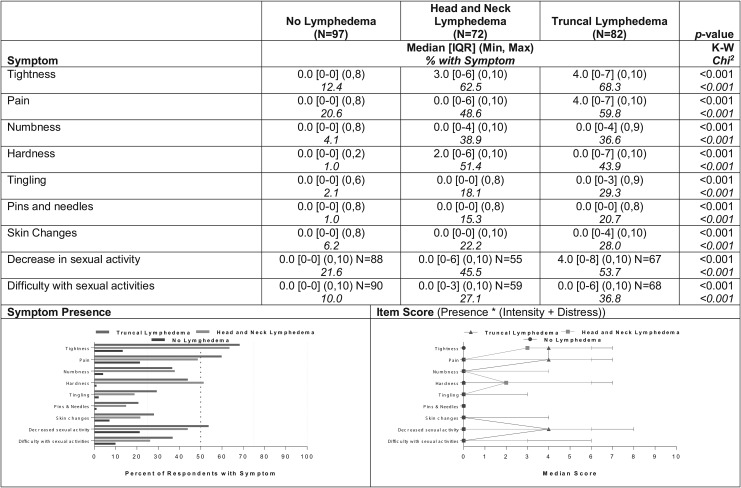

Nine symptoms distinguished the two groups with lymphedema from the group without, but demonstrated no statistically significant differences between them in terms of either prevalence or severity: tightness, pain, numbness, hardness, tingling, pins/needles, skin changes, and decrease/difficulty in sexual activity (Fig. 3). Prevalence reports within the two groups with lymphedema ranged from 15%–21% (pins/needles) to 62%–68% (tightness); within the group with no lymphedema, reports of those respective symptoms ranged from 1% (hardness, pins/needles) to 22% (decreased sexual activity). Again, a corresponding pattern of higher severity for both groups with lymphedema than for the group without was observed for severity of those nine symptoms (p < 0.001, Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Symptoms differentiating both the truncal and head and neck groups from the no lymphedema group (N = 251).

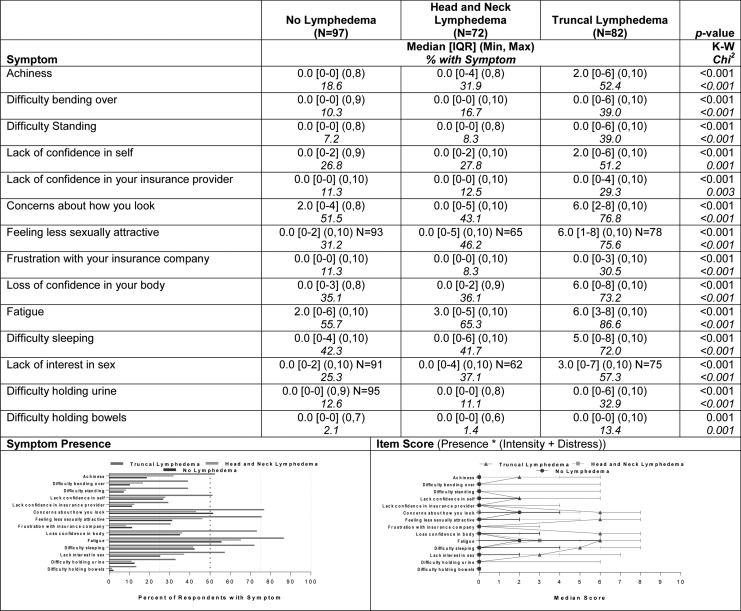

A large group of symptoms (14) differentiated the group of participants with truncal lymphedema from both of the other groups. As shown in Figure 4, prevalence reports within the group with truncal lymphedema were ∼20% higher for each of those symptoms compared with reports in the other groups, with the exception of difficulty holding bowels (13% vs. 1%–2%). The most prevalent of the set of distinguishing symptoms were fatigue (87%), concerns about appearance (77%), feeling less sexually attractive (76%), loss of confidence in your body (73%), and difficulty sleeping (72%). Those most frequently reported symptoms also had severity scores in the moderate range (median = 5–6 of possible 10) compared with median scores of 0–3 for the other groups (p < 0.001, Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Symptoms differentiating the truncal group from both the head/neck and no lymphedema groups (N = 251).

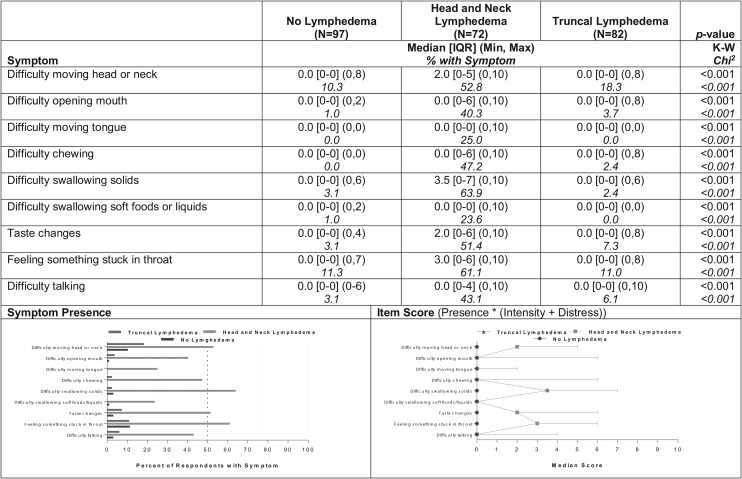

Another group of symptoms (9) differentiated the group of participants with head and neck lymphedema from both of the other groups. Prevalence reports within the group with head and neck lymphedema were 20%–50% higher for each of those symptoms compared with reports in the other groups (Fig. 5). The most prevalent of this set of distinguishing symptoms within the head/neck group were difficulty swallowing solids (64%), feeling like something is stuck in the throat (61%), difficulty moving the head/neck (53%), and taste changes (51%). The severity scores of those more frequently occurring symptoms tended to be in the mild range (median = 2–4 of possible 10) for the head/neck participants compared with median scores of 0 for the other groups (p < 0.001, Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Symptoms differentiating the head/neck group from both the truncal and no lymphedema groups (N = 251).

Prevalence and severity of the remaining 11 symptoms were not markedly different among the three groups of participants. Of those symptoms, psycho-emotional and social symptoms were the most prevalent regardless of whether the participant had any type of lymphedema or not (anxiety: 48%, feeling irritated: 47%, sadness: 45%, anger: 27%, feeling misunderstood by spouse/significant other: 24%, and partner lacking interest in sex: 24%). The two pain-related symptoms (stabbing and cramping) were each reported by 20% of the total sample of 251 participants. Finally, 16% of participants reported difficulty moving bowels, 10% difficulty breathing, and 8% difficulty urinating.

Discussion

While the nonlymphedema group was not evenly matched with the two lymphedema groups in terms of socioeconomic and comorbid factors, the differences in symptom profiles were dramatic. Truncal and head and neck lymphedema groups did show differences in lymphedema treatment, but some of these differences could be explained by the much higher symptom burden experienced by participants with truncal lymphedema.

Sensation and sexual activity symptoms appear to similarly impact both lymphedema groups (Fig. 3). However, some lymphedema-related symptoms differed based upon the area of swelling. Fourteen symptoms distinguished the truncal group from the other two groups, while nine symptoms differentiated the head and neck group from the other groups. While symptoms experienced largely by those with head and neck lymphedema may be more clinically severe because they can impair nourishment (difficulty opening mouth, chewing, and swallowing) (Fig. 5), those impacting mainly the truncal lymphedema group affect sleep and sexual health, as well as general function (bending, standing, holding urine, and bowels), and were not just more prevalent but more intense and distressful as well (Fig. 4).

The findings related to truncal swelling are believed to constitute the first report of such symptoms in this patient population. Participants with truncal lymphedema appeared to have a significant level of symptom burden compared with participants in the other two groups. Not only did they experience a greater number of symptoms overall but their symptoms were also more severe and intense.

Findings from this study should be considered in light of both its strengths and limitations. Limitations of this descriptive work include (1) the self-report nature, which limits the ability to ascertain nonresponse bias; (2) demographic and clinical differences between the nonlymphedema and lymphedema groups; and (3) lack of access to medical records to confirm medical concerns. Strengths of this report include (1) the use of lymphedema support communities to recruit a sample of participants highly likely to have the condition; (2) being the first known description and comparison of self-reported symptom differences among individuals with head and neck lymphedema, truncal lymphedema, and no lymphedema; and (3) identification of a potential need to use two anatomical sites (i.e., head and neck and truncal area) instead of one anatomical site (midline) when assessing and documenting lymphedema. Further research into symptoms associated with truncal lymphedema is clearly indicated.

Conclusion

The number, type, severity, and intensity of symptoms initially appear to vary based upon the location of the swelling. These preliminary findings support the need to use two lymphedema anatomical classifications (head and neck and truncal) instead of one classification (midline) when assessing swelling-related symptoms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) award Nos. UL1 TR002243 and UL1 TR000445 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the Martha Rivers Ingram Chair in Nursing, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.

Author Disclosure Statement

No conflicts or competing interests to disclose.

References

- 1. Földi M, Földi E, Strößenreuther C, Kubik S. Földi's Textbook of Lymphology: For Physicians and Lymphedema Therapists. 3rd ed. München: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rockson SG, Bergan JJ, Lee B-B. Lymphedema: A Concise Compendium of Theory and Practice. London: Springer Science & Business Media; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Deng J, Ridner SH, Murphy BA, Dietrich MS. Preliminary development of a lymphedema symptom assessment scale for patients with head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer 2012; 20:1911–1918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Klernas P, Johnsson A, Horstmann V, Kristjanson LJ, Johansson K. Lymphedema Quality of Life Inventory (LyQLI)-Development and investigation of validity and reliability. Qual Life Res 2015; 24:427–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ridner SH, McMahon E, Dietrich MS, Hoy S. Home-based lymphedema treatment in patients with cancer-related lymphedema or noncancer-related lymphedema. Oncol Nurs Forum 2008; 35:671–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Viehoff PB, Gielink PDC, Damstra RJ, Heerkens YF, van Ravensberg DC, Neumann MHA. Functioning in lymphedema from the patients' perspective using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as a reference. Acta Oncol 2015; 54:411–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Viehoff P, Hidding J, Heerkens Y, van Ravensberg C, Neumann H. Coding of meaningful concepts in lymphedema-specific questionnaires with the ICF. Disabil Rehabil 2013; 35:2105–2112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ridner SH, Dietrich MS, Niermann K, Cmelak A, Mannion K, Murphy B. A prospective study of the lymphedema and fibrosis continuum in patients with head and neck cancer. Lymphat Res Biol 2016; 14:198–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stolldorf DP, Dietrich MS, Ridner SH. Symptom frequency, intensity, and distress in patients with lower limb lymphedema. Lymphat Res Biol 2016; 14:78–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42:377–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ridner SH, Dietrich MS. Development and validation of the Lymphedema Symptom and Intensity Survey-Arm. Support Care Cancer 2015; 23:3103–3112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ridner SH, Doersam JK, Stolldorf DP, Dietrich MS. Development and validation of the Lymphedema Symptom Intensity and Distress Survey-lower limb. Lymphat Res Biol 2018; 16:538–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deng J, Murphy BA, Dietrich MS, Sinard RJ, Mannion K, Ridner SH. Differences of symptoms in head and neck cancer patients with and without lymphedema. Support Care Cancer 2016; 24:1305–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]