Abstract

Elucidating the cellular architecture of the human cerebral cortex is central to understanding our cognitive abilities and susceptibility to disease. Here we applied single nucleus RNA-sequencing to perform a comprehensive analysis of cell types in the middle temporal gyrus of human cortex. We identified a highly diverse set of excitatory and inhibitory neuronal types that are mostly sparse, with excitatory types being less layer-restricted than expected. Comparison to similar mouse cortex single cell RNA-sequencing datasets revealed a surprisingly well-conserved cellular architecture that enables matching of homologous types and predictions of human cell type properties. Despite this general conservation, we also find extensive differences between homologous human and mouse cell types, including dramatic alterations in proportions, laminar distributions, gene expression, and morphology. These species-specific features emphasize the importance of directly studying human brain.

The cerebral cortex is responsible for many of our higher cognitive abilities and is the most complex structure known to biology: it is comprised of 16 billion neurons and 61 billion non-neuronal cells organized into more than 100 distinct anatomical or functional regions 1,2. Human cortex is expanded relative to mouse, the dominant model organism in research, with a >1000-fold increase in area and number of neurons 3. While the general principles of cortical development and basic architecture of cortex appear conserved across mammals 4 prior studies suggest differences in the cellular makeup of human cortex 5,6,7,8,9,10,11. For example, superficial cortical layers are expanded in mammalian evolution 12 and some cell types, such as interlaminar astrocytes 13 and rosehip neurons 14, have specialized features in human compared to mouse. Likewise, transcriptional regulation varies between mouse, non-human primate, and human, including genes associated with neuronal structure and function 15,16,17.

Single cell transcriptomics enables molecular classification of cell types, provides a metric for comparative analyses, and is fueling efforts to understand the complete cellular makeup of the mouse brain 18 and even the entire human body 19. Single cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) of mouse cortex demonstrated robust transcriptional signatures of cell types 20,21,22, and suggested ~100 types per cortical area. Dissociating live cells from human brain is difficult making scRNA-seq challenging to apply to this type of tissue, whereas single nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) enables transcriptional profiling of nuclei from frozen human brain specimens 23,24. Importantly, nuclei contain sufficient gene expression information to distinguish closely related cell types at similar resolution to scRNA-seq 25,26, but early applications of snRNA-seq to human cortex did not have sufficient depth of coverage to achieve similar resolution to mouse studies 27,28. Here, we established robust methods for cell type classification in human brain using snRNA-seq and compared cortical cell types to illuminate conserved and divergent features of human and mouse cerebral cortex.

Results

Transcriptomic taxonomy of cell types

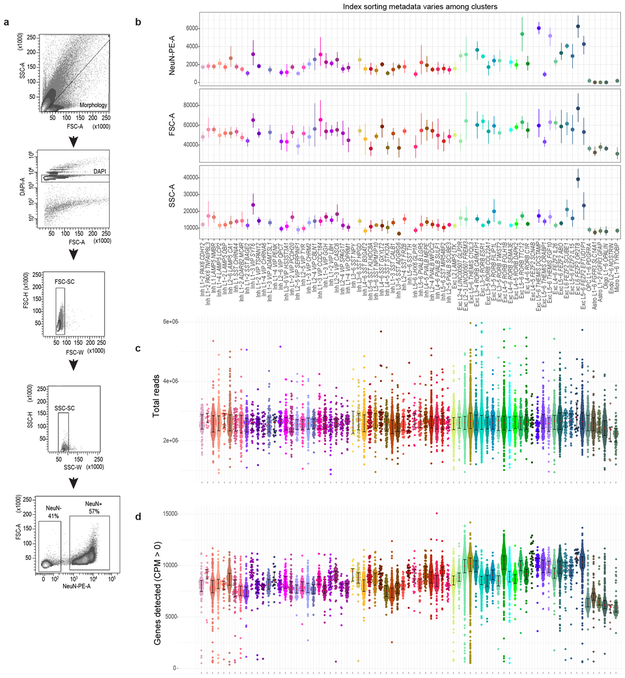

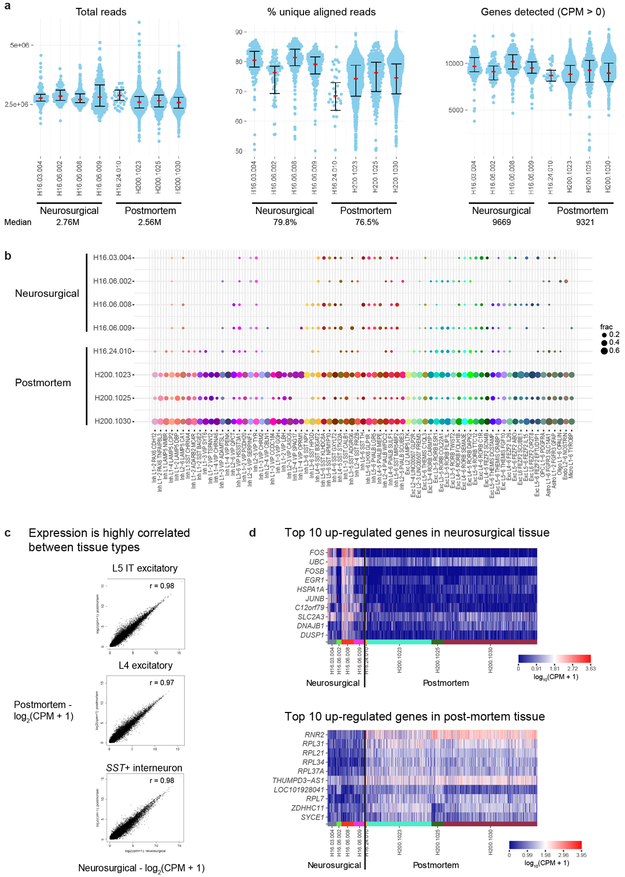

To transcriptomically define cell types in human cortex we used snRNA-seq and focused on middle temporal gyrus (MTG) largely from postmortem brain. MTG is often available through epilepsy resections, permitting comparison of postmortem versus acute neurosurgical tissues, and enabling future correlation with in vitro slice physiology. Tissues were processed as described 14 (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 1a). Nuclei were collected from 8 donor brains (Extended Data Table 1), with most from postmortem donors (n=15,206) and a minority (n=722) from layer (L)5 of MTG removed during neurosurgeries (Extended Data Fig. 2).

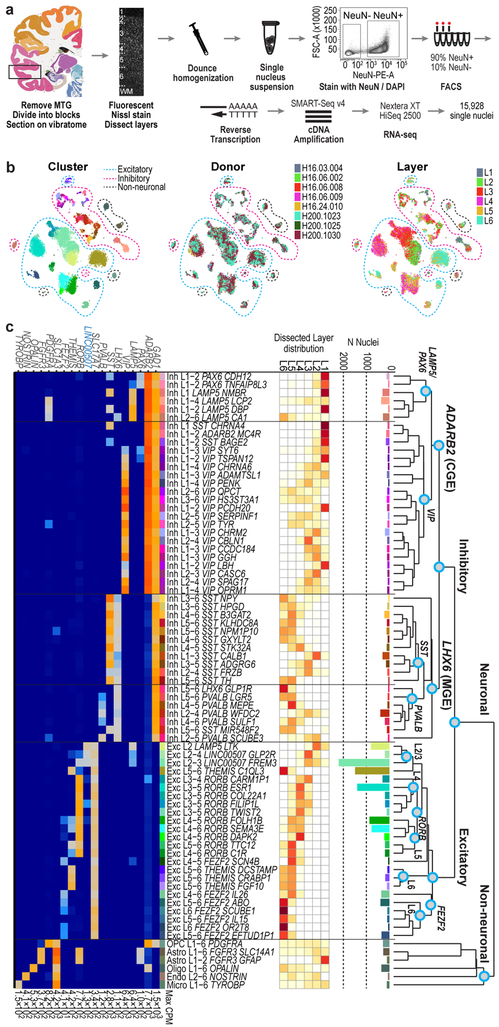

Figure 1. Cell type taxonomy in human middle temporal gyrus (MTG).

a, Schematic of RNA-sequencing of neuronal (NeuN+) and non-neuronal (NeuN-) nuclei isolated from human MTG. Human brain atlas image from http://human.brain-map.org/ b, t-SNE visualization of 15,928 nuclei grouped by expression similarity and colored by cluster, donor, and dissected layer. c, Taxonomy of 69 neuronal and 6 non-neuronal cell types based on median cluster expression. Branches are labeled with major cell classes. Cluster sizes and estimated laminar distributions (white, low; red, high) are shown below. d, Median log-transformed expression of marker genes (blue, non-coding) across clusters with maximum expression (CPM) on the right.

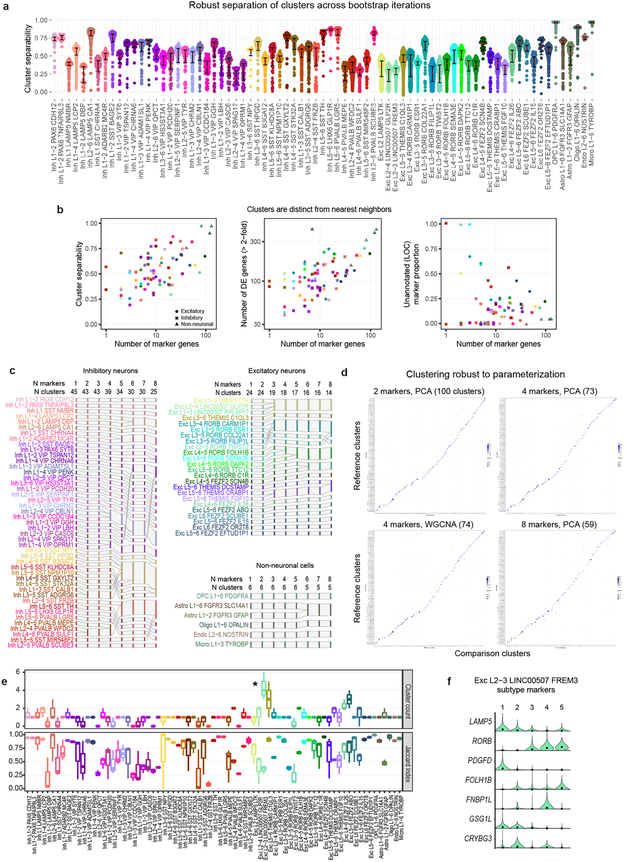

In total, 15,928 nuclei passed quality control, including 10,708 excitatory neurons, 4,297 inhibitory neurons, and 923 non-neuronal cells. Nuclei from each broad class were iteratively clustered as described 26 (Methods). Clusters were generally robust to different iterative clustering methods and were distinguished from nearest neighbors by ≥30 differentially expressed genes and at least 1, but often more binary markers. Requiring more binary markers led to merging of some clusters (Extended Data Fig. 3). Marker genes for stringent clusters defined by 4 binary markers are provided in Supplementary Table 2. On average, neuronal nuclei were larger than non-neuronal nuclei, and median gene detection was higher for neurons (9,046 genes) than for non-neuronal cells (6,432 genes), as reported for mouse 21,22 (Extended Data Fig. 1). Transcriptomic cell types were largely conserved across individuals and tissue types since all curated clusters contained nuclei from multiple donors, and nuclei from postmortem and neurosurgical tissues clustered together and had highly correlated expression within cell classes (Fig. 1b). Postmortem nuclei had slightly lower median gene detection than neurosurgical nuclei, and there was a small, consistent expression signature of tissue type. For example, neurosurgical nuclei had higher expression of some activity regulated genes (e.g. FOS), whereas postmortem nuclei had higher expression of ribosomal genes that correlate with postmortem interval 29 (Extended Data Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 1).

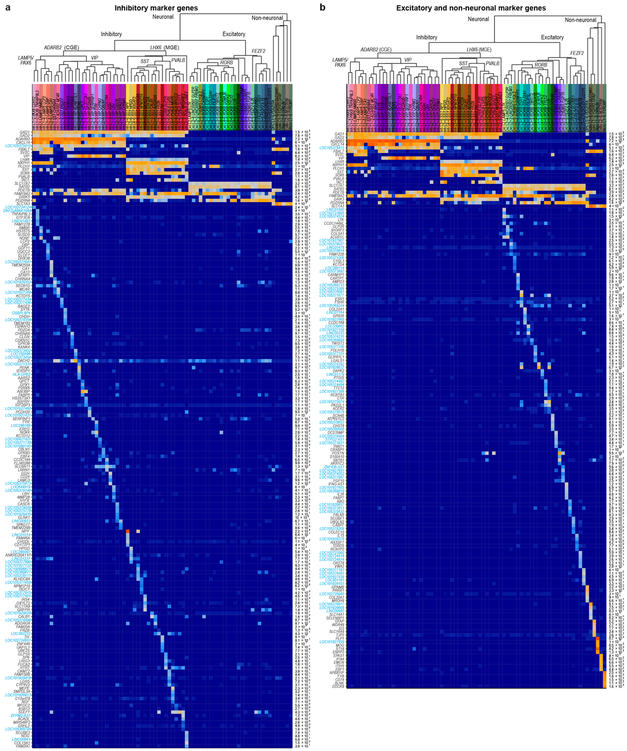

We defined 75 transcriptomically distinct cell types, including 45 inhibitory neuron types that express the GABAergic interneuron marker GAD1, 24 excitatory neuron types that express the vesicular glutamate transporter SLC17A7, and 6 non-neuronal types that express the glutamate transporter SLC1A3. As expected 22, hierarchical relationships among types roughly mirror their developmental origins. We refer to clusters as cell types, intermediate order nodes as subclasses, higher order nodes (e.g. interneurons from caudal ganglionic eminence [CGE]) as classes, and broad divisions (e.g. excitatory neurons) as major classes. Neurons split into two major classes: cortical plate-derived excitatory neurons and ganglionic eminence (GE)-derived inhibitory neurons. Non-neuronal types formed a separate branch based on differential expression of many genes (Fig. 1c). We developed a nomenclature for clusters based on: 1) major cell class, 2) layer enrichment, 3) subclass marker gene, and 4) cluster-specific marker gene (Figure. 1c, Extended Data Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 2). We generated a searchable semantic representation of these clusters to link them to existing ontologies 30 (MTG Ontology, Supplementary Table 3). We find broad correspondence to earlier human cortex snRNA-seq studies 24,27,28, but identify many additional neuron types (Extended Data Fig. 5). Most cell types were rare (<0.7% of MTG neurons), including almost all interneuron types and deep layer excitatory neuron types. However, upper layer excitatory neurons were dominated by a small number of abundant types (>3.5% of MTG neurons). Excitatory types and many interneuron types were spatially restricted, whereas non-neuronal nuclei were distributed across all layers, with the notable exception of one astrocyte type (Fig. 1c).

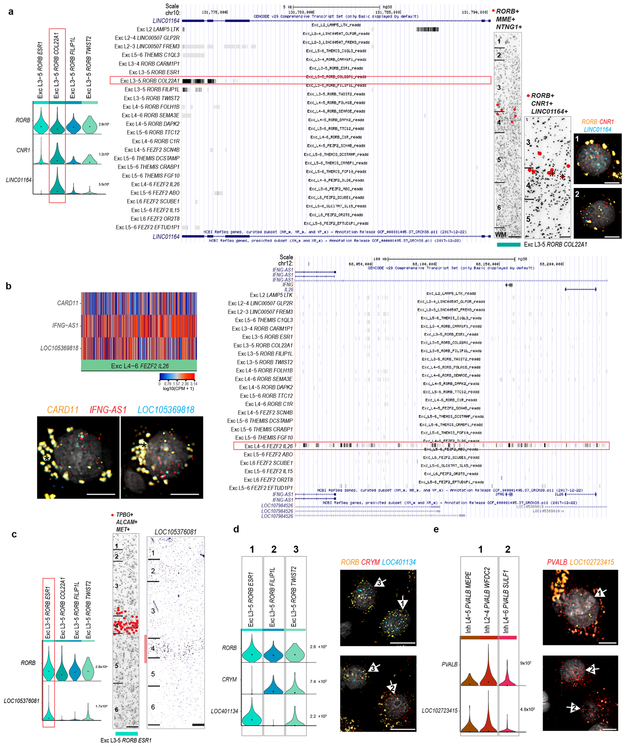

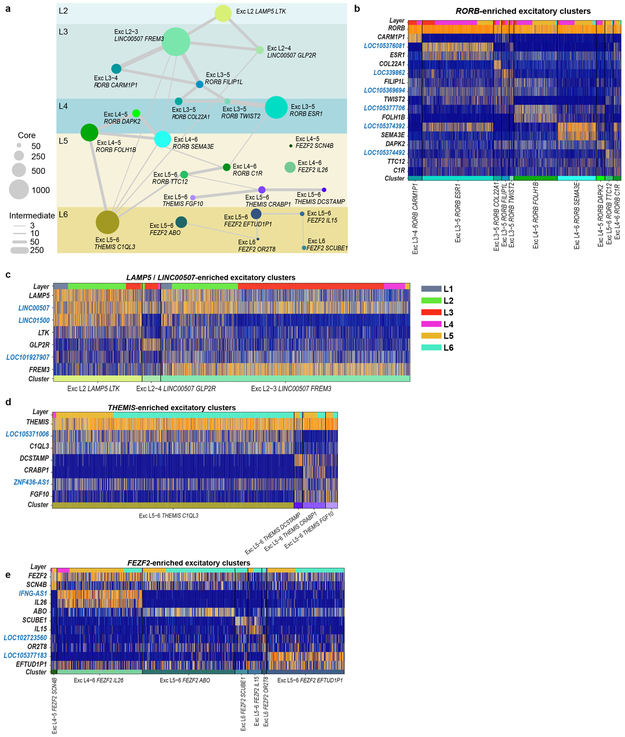

Excitatory types often span layers

Excitatory neuron types broadly segregated by layer, expressed known laminar markers, and were generally most similar to types in the same or adjacent layers (Fig. 2, Extended Data Fig. 6), perhaps reflecting a developmental imprint of the inside-out generation of cortical layers 16. Similarity by laminar proximity was also apparent in the hierarchical dendrogram structure except for Exc L5-6 THEMIS C1QL3, which was transcriptionally similar to several L2-3 and L5-6 types. Exc L4-5 FEZF2 SCN4B and Exc L4-6 FEZF2 IL26 were so distinct that they occupied separate branches on the dendrogram (Fig. 2a). Complex relationships between clusters are represented as constellation diagrams that capture both continuous and discrete gene expression variation among types, as described 22 (Extended Data Fig. 6a).

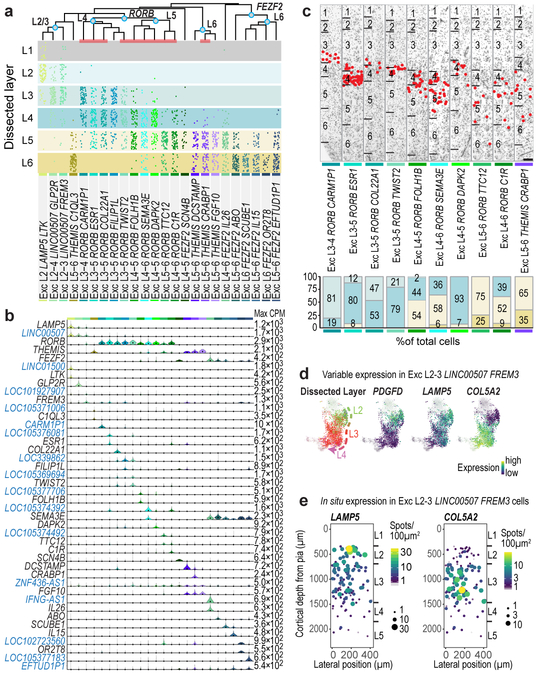

Figure 2. Excitatory neuron diversity and marker gene expression.

a, Estimated layer distributions of cell types based on dissected layer of nuclei (dots). Layer 1 dissections included some excitatory neurons from layer 2. b, Violin plots of marker gene (blue, non-coding) expression distributions across clusters (n=10,525 nuclei). Rows are genes, black dots are median expression, and maximum expression (CPM) is on the right. c, Representative inverted images of DAPI-stained cortical columns with cells (red dots) in each cluster (red bars in a) identified using listed marker genes. Experiments repeated on ≥2 donors per cell type. Scale bar, 250 μm. Bar plots summarize layer distributions for at least n=2 donors per cell type. d, t-SNE maps of superficial excitatory neurons with nuclei in the Exc L2-3 LINC00507 FREM3 cluster (n=2,284) colored by dissected layer and expression of PDGFD, LAMP5, and COL5A2. e, Single molecule fluorescent in situ hybridization (smFISH) quantification of LAMP5 and COL5A2 expression.

Each excitatory type selectively expressed marker genes (Fig. 2b), although a combinatorial profile was often necessary to distinguish each type from all other types (Extended Data Fig. 7). Many markers are novel and important for cell function, such as BHLH transcription factors (TWIST2), collagens (COL22A1), and semaphorins (SEMA3E). Surprisingly, 16 out of the 37 most specific marker genes were unannotated or non-coding (nc) RNAs. Cell type specific expression of ncRNAs is consistent with previous studies 31,32,33, could be validated in tissue sections, and may have been detected here due to preferential nuclear localization 32 or physical linkage of ncRNAs to chromatin 31 (Fig. 2b; Extended Data Figs. 6, 8).

Unexpectedly, most excitatory types were not restricted to dissections from single layers. Three types were enriched in L2-L3, 10 RORB-expressing types were enriched in L3-6, and 4 THEMIS-expressing and 7 FEZF2−expressing types in L5-L6 (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. 6a). Distribution across layers was not due to dissection error: gene expression was consistent within each cluster across nuclei dissected from different layers (Extended Data Fig. 6b-e) and in situ distributions largely matched multi-layer snRNA-seq predictions (Fig. 2a, c, Extended Data Fig. 7). Three types were localized to L3c and upper L4 (Fig. 2c). One (Exc L3-4 RORB CARM1P1) had large nuclei (Extended Data Figs. 1b, 7) consistent with the giant pyramidal L3c neurons in MTG 34. Two types were mostly in L4, but 5 others spanned multiple layers (Fig. 2c, Extended Data Fig. 7c). This heterogeneity implies that anatomical laminar location alone is insufficient to predict neuron type, although it remains to be seen if this is a feature of MTG or human cortex generally.

Although upper layers are greatly expanded in human cortex relative to mouse, we still only find three L2-L3 excitatory types just as in mouse cortex 22. However, examination of Exc L2-3 LINC00507 FREM3 (n=2,284 nuclei) revealed continuous gene expression variation within this type (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Video 1), consistent with demonstrated diverse cellular properties in human L2-3 excitatory neurons 34,35. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) confirmed enrichment of LAMP5 and COL5A2 in L2 and L3 neurons, respectively and Exc L2-3 LINC00507 FREM3 split into multiple subtypes with varying clustering parameters (Fig. 2e, Extended Data Figs. 3, 9). Thus, there is transcriptomic diversity within as well as between subtypes of L2-3 excitatory neurons that likely corresponds to the anatomical and functional heterogeneity of these cells.

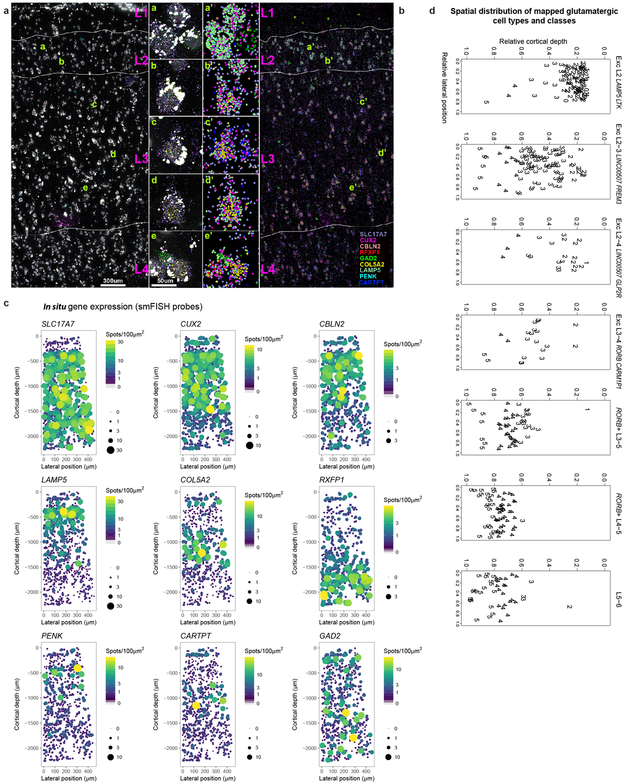

Inhibitory neuron diversity

Inhibitory neurons formed two major branches, distinguished by expression of ADARB2 and LHX6, like mouse cortex where these branches correlate with developmental origins in CGE and medial ganglionic eminence (MGE), respectively 22. The LHX6 branch 36,37 included PVALB and SST subclasses and the ADARB2 branch had LAMP5/PAX6 and VIP subclasses. Consistent with mouse, the ADARB2 branch showed more diversity in L1-3 versus L4-6, and the opposite was true for the LHX6 branch (Fig. 3, Extended Data Fig. 10). As with excitatory neurons, many interneuron markers were ncRNAs (Fig. 3, Extended Data Fig. 4a). Surprisingly, the mouse CGE interneuron marker HTR3A 38 was not expressed in human CGE types (Fig. 3c).

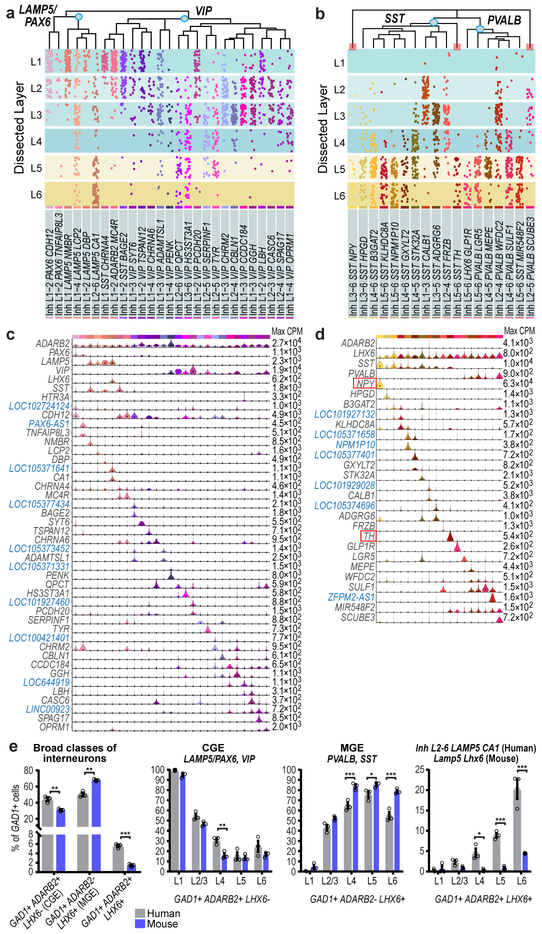

Figure 3. Inhibitory neuron diversity and layer distribution.

a, b Layer distributions of cell types estimated based on dissected layer of nuclei (n=4,164) (dots) and validated in situ for three clusters (red bars, Extended Data Fig. 10a, b). c, d Violin plots of marker gene (blue, non-coding) expression distributions across clusters (c, n=2,320 nuclei; d, n=1,844 nuclei). Rows are genes, black dots are median expression, and maximum expression (CPM) is on the right. e, Relative proportions and layer distributions of interneuron classes in human MTG and mouse temporal association area (TEa) quantified by in situ labeling of marker genes with mFISH. Bars show the mean, error bars the standard deviation, and circles represent n=3 specimens for human and mouse. Two-tailed t-test with Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons, df=20, *p<0.05 **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

The LAMP5/PAX6 subclass had 6 types mostly enriched in L1-2 (Fig. 3a). Inh L1-4 LAMP5 LCP2 matched rosehip cells (Extended Data Fig. 5d), discovered in L1 14 but present in all cortical layers. Among LAMP5/PAX6 types, only Inh L2-6 LAMP5 CA1 expressed LHX6, suggesting possible origins in MGE like Lamp5 Lhx6 cells described in mouse 22. VIP was the most diverse subclass (21 types), with many types enriched in upper layers (Fig. 3a). Several VIP types were closely related to the LAMP5/PAX6 type L1 LAMP5 NMBR and localized to L1-L2. Some CGE-derived cell types in L1 expressed SST (Fig. 3a, c), as described in human 14 but not in mouse L1 interneurons 22.

The SST subclass had 11 types that were spatially restricted, including the distinctive types Inh L5-6 SST TH and Inh L3-6 SST NPY in L5-6 (Fig. 3b, d, Extended Data Fig. 10c). ISH showed sparse TH expression in L5-6 of human MTG and the mouse homologous region (TEa), suggesting that this gene marks similar cell types in both species, whereas NPY was more sparsely expressed in human, indicating differential expression of this closely-studied marker between species 39,40. The PVALB subclass had 7 clusters; several SST and PVALB types were very similar (Fig. 3d, Extended Data Fig. 10b), pointing to close links between these subclasses. Inh L2-5 PVALB SCUBE3 is a distinctive type that expresses chandelier cell marker UNC5B 41 and likely corresponds to these specialized cells. Novel marker genes of this cluster label cells enriched in L2-4 in situ (Fig. 3, Extended Data Fig. 10d).

Human MTG had similar proportions of MGE (44% LHX6+ nuclei) and CGE (50% ADARB2+ nuclei) interneurons based on snRNA-seq data. In contrast, prior studies report ~70% MGE versus ~30% CGE interneurons in mouse cortex 38,42. To further examine these differences, we quantified proportions of ADARB2+ and LHX6+ interneurons in human MTG and mouse TEa (Fig. 3e, Extended Data Fig. 10e, f). Interneurons co-expressing ADARB2 and LHX6 (Figs. 1, 3) were considered separately. Again, we found similar proportions of MGE (50.2 ± 2.3%) and CGE (44.2 ± 2.4%) interneurons in human, and >2 times as many MGE (67.8 ± 0.9%) than CGE (30.8 ± 1.2%) interneurons in mouse. The increased proportion of CGE interneurons in human was greatest in L4 and the decreased proportion of MGE interneurons in human was greatest in L4-6 (Fig. 3e). snRNA-seq (6.1% of GAD1+ cells) and cell counts (5.6 ± 0.3% of GAD1+ cells) confirmed an increase in the proportion of ADARB2 and LHX6 co-expressing interneurons in human versus mouse (1.4 ± 0.2% of GAD1+ cells), particularly in L6 (Fig. 3e).

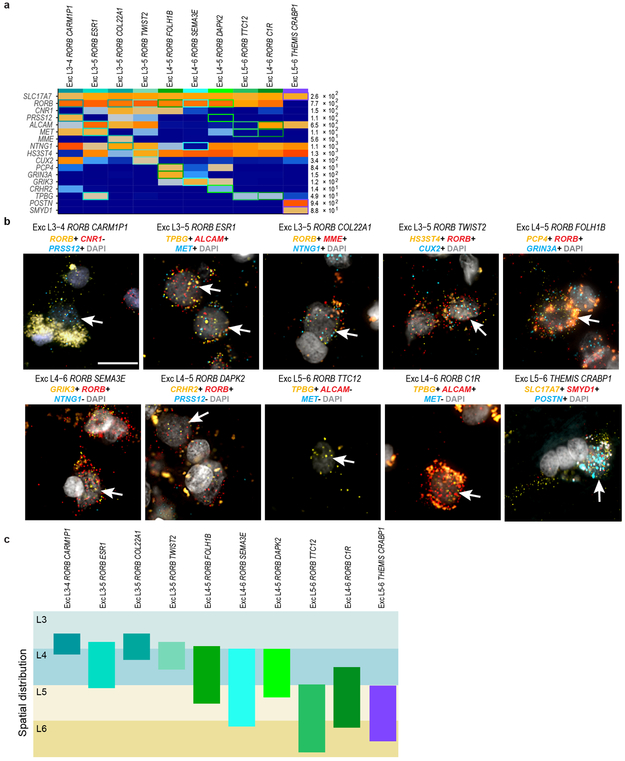

Diverse morphology of astrocyte types

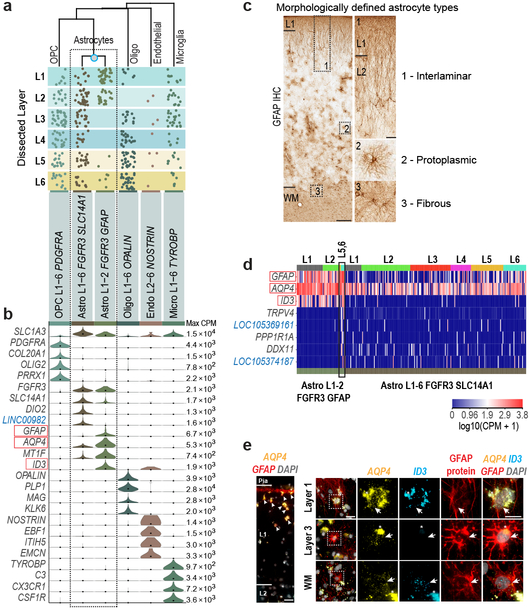

We identified major subclasses of non-neuronal cells, including 2 astrocyte types (Fig. 4). Astrocytes in human cortex are functionally 43 and morphologically 13 specialized in comparison to rodent (Fig. 4c). Primate-specific interlaminar astrocytes reside in L1 and extend long processes, whereas protoplasmic astrocytes are found in L2-6 13. We also find two astrocyte types with different laminar distributions: Astro L1-2 FGFR3 GFAP in L1-2 and Astro L1-6 FGFR3 SLC14A1 in all layers (Fig. 4a). SnRNA-seq showed that Astro L1-2 FGFR3 GFAP expressed ID3 and had higher GFAP and AQP4 expression than Astro L1-6 FGFR3 SLC14A1 (Fig. 4b, d). Multiplex (m)FISH for GFAP and AQP4 showed cells with high expression of these genes in L1, and combined mFISH and GFAP immunohistochemistry showed cells in L1 that coexpressed AQP4 and ID3 and had long GFAP+ processes, consistent with interlaminar astrocytes. GFAP+ cells with protoplasmic astrocyte morphology lacked ID3 expression, consistent with Astro L1-6 FGFR3 SLC14A1 (Fig. 4e). While most nuclei in Astro L1-2 FGFR3 GFAP came from L1-2, 7 were from layer 5-6 dissections and expressed ID3 and distinct markers, and mFISH showed that astrocytes coexpressing ID3 and AQP4 at the L6-white matter (WM) border had fibrous astrocyte morphology 13 (Fig. 4c-e). Therefore, we predict that sampling more non-neuronal nuclei will identify additional astrocyte diversity.

Figure 4. Non-neuronal cell type diversity and marker gene expression.

a, Layer distributions of cell types estimated based on dissected layer of nuclei (n=914) (dots). b, Violin plots of marker gene (blue, non-coding) expression distributions across clusters. Rows are genes, black dots are median expression, and maximum expression (CPM) is listed on the far right. c, Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for GFAP demonstrates morphologically-defined human astrocyte types. Boxed regions shown at higher magnification on the right. Scale bars: low magnification (250 μm), high magnification (50 μm). d, Heatmap of marker gene expression with nuclei (columns) ordered by dissected layer. Several nuclei in deep layers (black box) express distinct markers. e, mFISH and immunohistochemistry of astrocyte subtype markers highlighted (red boxes) in b, d. Experiments repeated on n=2 human donors. Left: Cells with high expression of AQP4 and GFAP in layer 1 (white arrowheads). Scale bar, 25 μm. Right: Top row: Cell in layer 1 co-expresses AQP4 and ID3 and has long, GFAP-labeled processes. Middle row: Protoplasmic astrocyte in layer 3 lacks expression of ID3. Bottom row: Fibrous astrocyte at the white matter (WM)-layer 6 boundary expresses AQP4, ID3, and GFAP protein. Asterisks mark lipofuscin. Boxed areas are magnified to the right. Scale bars: low magnification (25 μm), high magnification (15 μm).

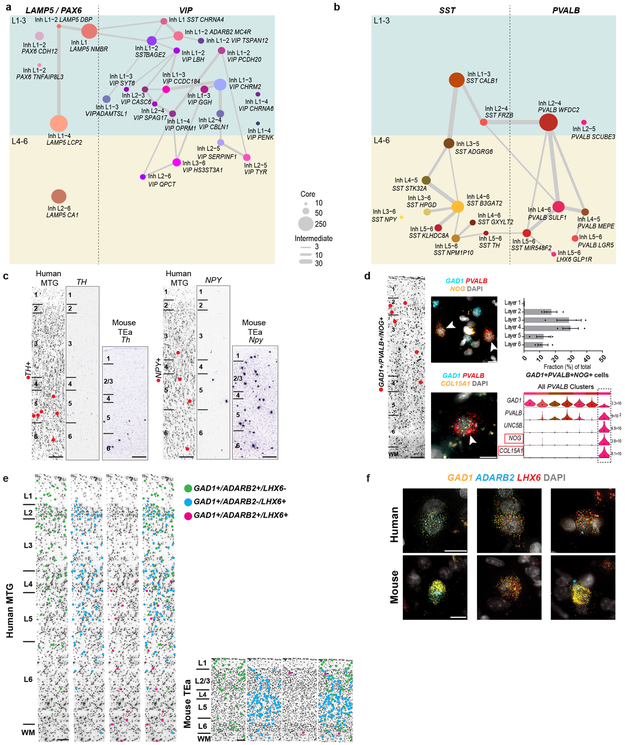

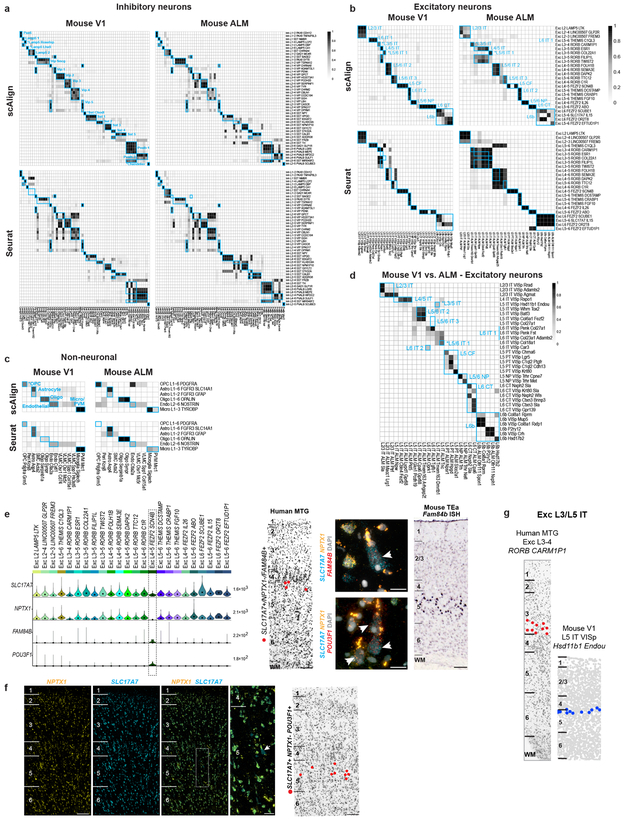

Human and mouse cell type homology

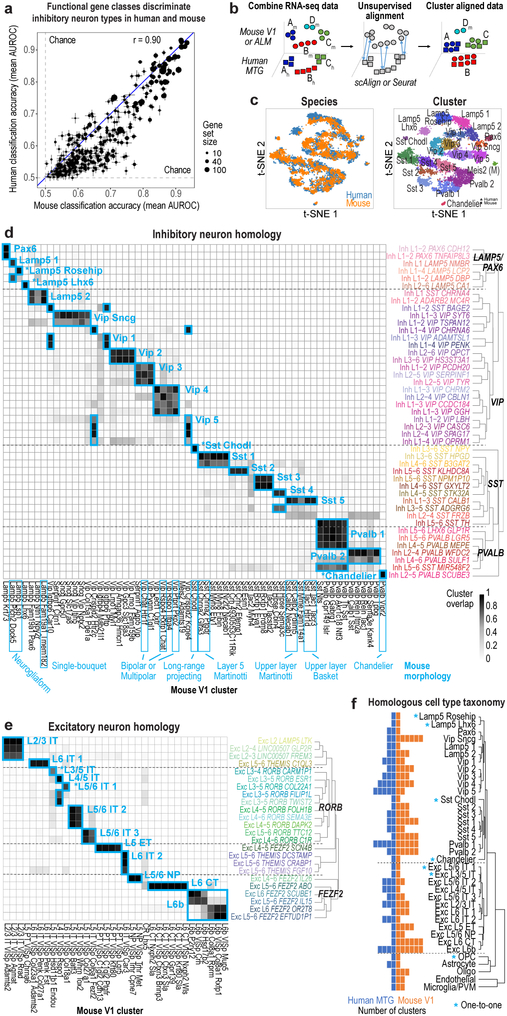

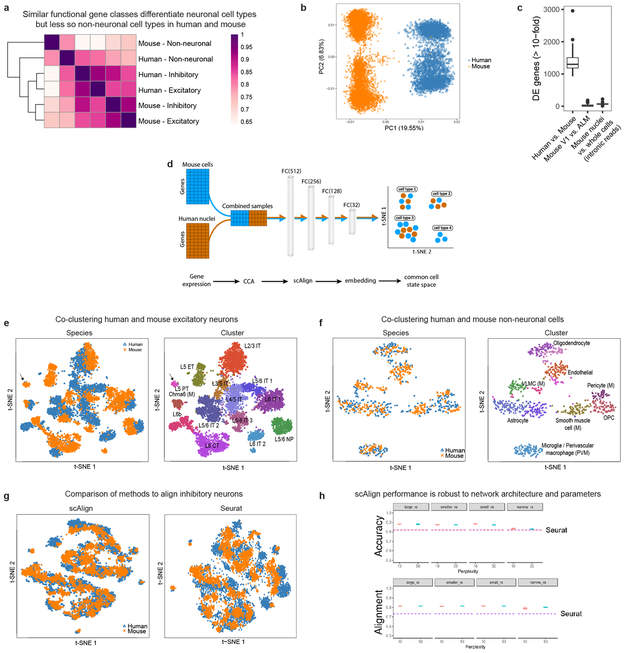

To examine conservation of cellular architecture, we aligned transcriptomic cell types in human MTG to two distinct mouse cortical areas: primary visual cortex (V1) and a premotor area (ALM) 22. Matching cell types requires shared expression patterns between species, and we find that gene families (mean = 21 genes/set) that best discriminate mouse interneurons 41 also discriminate human interneurons (Fig. 5a). Similar genes also discriminated human and mouse excitatory types, but less so non-neuronal types (Extended Data Fig. 11a).

Figure 5. Evolutionary conservation of cell types between human and mouse.

a, Similar functional gene families (n=384 gene sets) discriminate inhibitory neuron types in human and mouse. Error bars correspond to the SD of mean MetaNeighbor AUROC scores across 10 sub-samples of cells. b, Schematic of unsupervised alignment and clustering of combined human and mouse cortical samples using scAlign or Seurat. c, t-SNE visualization of human (n=3,594 nuclei) and mouse (n=6595 cells) inhibitory neuron clusters after alignment with scAlign. d-e, Human and mouse cell type homologies for inhibitory neurons (d) and excitatory neurons from mouse V1 (e) predicted based on shared cluster membership. Grey shade corresponds to the minimum proportion of human nuclei or mouse cells that co-cluster. Rows are human clusters and columns are mouse clusters. Homologous clusters were labeled based on human and mouse cluster membership and include excitatory neuron projection targets (IT, intratelencephalic; ET, extratelencephalic/pyramidal tract; NP, near-projecting; CT, corticothalamic). Known morphologies indicated for mouse inhibitory types. f, Taxonomy of 32 neuronal and 5 non-neuronal homologous cell types and cell classes. Asterisks mark one-to-one matches.

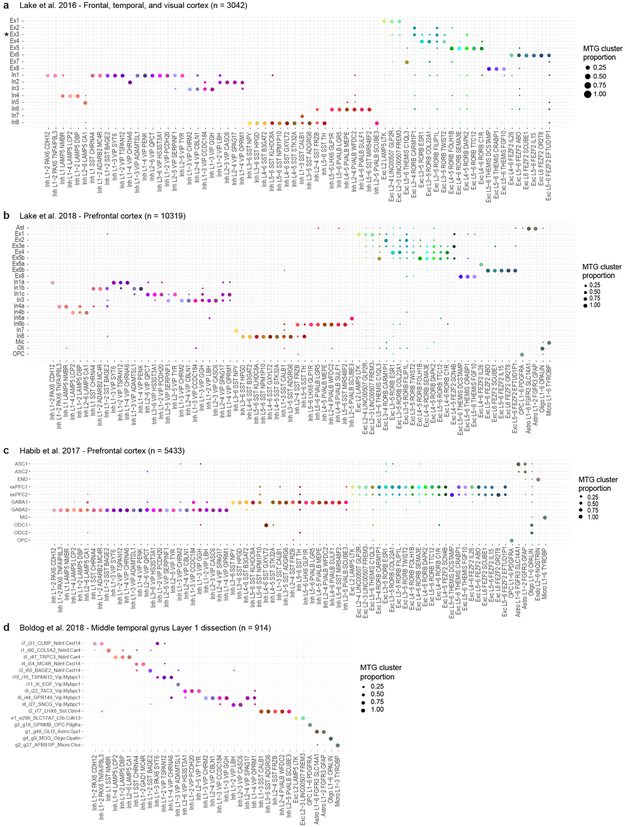

Applying principal components analysis (PCA) to combined expression data from inhibitory neurons from human MTG and mouse V1 separated samples first by species and then by cell type (Extended Data Fig. 11b). Applying canonical correlation analysis (CCA) based on shared co-expression patterns 44 and a neural network-based alignment algorithm (scAlign 45) aligned human and mouse cortical samples that were then clustered. Homologous types were identified based on shared cluster membership (Fig. 5b-e, Extended Data Fig. 11d-f). Consistent cell type homologies were obtained using a second alignment method based on dynamic time warping (Seurat) (Extended Data Fig. 11g, h) and by aligning human MTG to mouse V1 and ALM (Extended Data Fig. 12). These homologies were supported by shared marker genes between species (Extended Data Fig. 13, Supplementary Table 4). Clusters were combined into a hierarchical taxonomy of 32 neuronal and 5 non-neuronal cell types and subclasses (Fig. 5f). All major classes and subclasses were aligned and 7 types were matched 1-to-1 between species.

Alignment of homologous types allows prediction of cellular properties in human. For example, Inh L2-5 PVALB SCUBE3 matches mouse chandelier cells (Pvalb Vipr2) and is predicted to selectively innervate axon initial segments (Fig. 5d). Likewise, Inh L3-6 SST NPY matches mouse Sst Chodl and is predicted to have long-range projections and contribute to sleep regulation 46. Many other anatomically-defined interneuron types can be inferred (Fig. 5d), although future experiments are needed to test these predictions. Long-range projection targets of human excitatory neurons can also be predicted. For example, Exc L4-5 FEZF2 SCN4B cells match mouse extratelencephalic-projecting (ET) L5 excitatory neurons (Fig. 5e) and are predicted to project sub-cortically. Intriguingly, ET neurons are much less abundant in human than in mouse (1% vs. 20% of L5 excitatory neurons) 22 (Extended Data Fig. 12e-f). Some homologous types shift layers between species, such as Exc L3-4 RORB CARM1P1 in L3 of human MTG that matches L5-enriched types in mouse (Extended Data Fig. 12g).

Human non-neuronal cells matched a subset of mouse types (Extended Data Fig. 12c). Human oligodendrocytes matched two mouse mature oligodendrocyte types, while human oligodendrocyte precursors (OPCs) matched mouse 1-to-1. Only 9 endothelial cells were sampled in human and mapped to two endothelial subtypes in mouse. Both human astrocyte clusters mapped to one astrocyte cluster in mouse. Finally, human microglia clustered with mouse microglia and perivascular macrophages (Extended Data Fig. 11f).

Three rare mouse neuronal types lacked homologous human types. The mouse Meis2 inhibitory type primarily found in white matter 22, may have been missed due to limited sampling of layer 6b-WM in human. Cajal-Retzius cells are very rare in adult human cortex (<0.1% of L1 neurons) 47 and therefore unlikely to be sampled. Finally, mouse L5 PT VISp Chrna6, an ET type that projects to superior colliculus 48, aligns with only 2 human nuclei (Extended Data Fig. 11e), suggesting a matching type may be found with deeper sampling in human.

While many homologous subclasses had comparable diversity between species, some had expanded diversity in human and some in mouse. For example, there is an apparent increase in the diversity of L4 excitatory neurons in human MTG versus mouse V1. Mouse ET types are much more diverse than putative ET types in human, which may reflect either a species difference or likely undersampling, as they make up < 1% of L5 excitatory neurons in MTG. L6 CT types are also more diverse in mouse V1 than human MTG. However, there are only 2 L6 CT types in mouse ALM, so this may reflect differences between primary sensory and association areas (Fig. 5e-f).

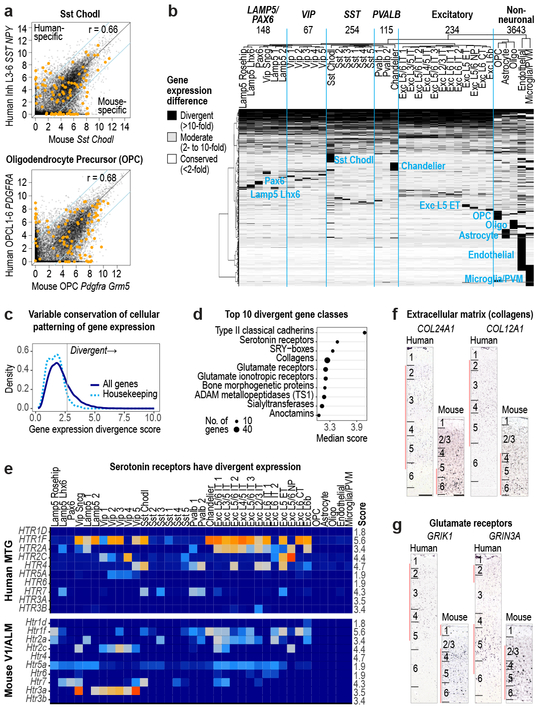

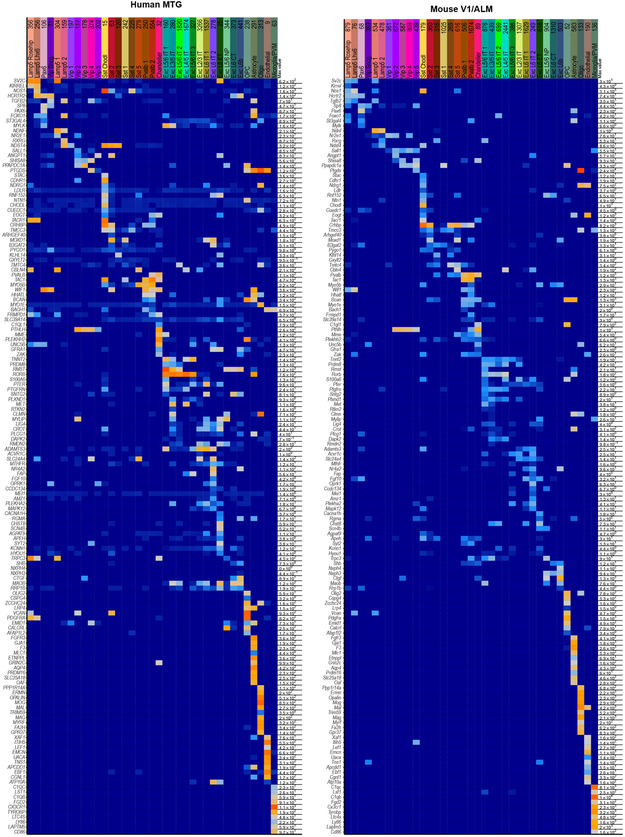

Divergent expression between types

Identification of homologous types or classes allows analysis of conservation and divergence of gene expression patterns across types. For each pair of homologous types, we compared expression of 14,553 orthologous genes between human and mouse (Fig. 6). Nuclear expression levels were estimated from intronic reads to better compare human snRNA-seq and mouse scRNA-seq data, as we previously found few differences in intronic expression between matched sets of mouse nuclei and whole cells 26 (Extended Data Fig. 11c). Comparison of homologous types showed a mix of conserved and divergent expression. The Sst Chodl type (Inh L3-6 SST NPY in human) had conserved expression overall but 18% of genes had highly divergent expression (>10-fold difference), including many marker genes. OPCs also had conserved expression and 14% highly divergent genes. Two thirds of all genes analyzed (9,748) had divergent expression in at least 1 of 37 homologous types, and many had expression changes restricted to one type or class. Non-neuronal types had the most divergent expression (3,643 genes with >10-fold difference) supporting increased evolutionary divergence of non-neuronal expression patterns between human and mouse 17 (Fig. 6a, b).

Figure 6. Divergent cell type expression between human and mouse.

a, Comparison of expression levels of 14,553 orthologous genes between human and mouse for Sst Chodl and OPCs. Genes outside the blue lines have highly divergent expression (>10-fold change) and include cluster specific markers (orange dots). Benjamini & Hochberg Pearson correlation (r). b, Patterns of expression change between human and mouse for 9748 divergent genes (67% of orthologous genes). Groups of genes with similar patterns are labeled by the affected cell class. Top row: number of genes with expression divergence restricted to each broad class of cell types. c, Distribution of scores (Methods) that measures the magnitude of expression change across homologous cell types for all genes (dark blue) and housekeeping genes (light blue). d, Gene families (n > 10 genes) with the most divergent expression patterns (highest score) include neurotransmitter receptors, ion channels, and cell adhesion molecules. e, Expression (trimmed average CPM) of most serotonin receptors has changed in homologous cell types. Scores listed on far right. f, g, ISH of divergent genes show shifts in laminar expression consistent with different cell type expression in human and mouse. Red bars show layers with enriched expression. Scale bars: human (250 μm), mouse (100 μm).

Most genes had divergent expression only in a subset of types, resulting in a shift in the cell type specificity of genes (quantified as the beta score, Methods, Supplementary Table 5). Genes with higher scores had high expression in ≥1 cell type and low expression in the remaining types, and were expressed in different subsets of types between species. 23% of genes (3,382) were more highly divergent than 95% of 252 housekeeping genes (Fig. 6c) recently shown to be stably expressed in multiple cell types in mouse and human 49. Cell type markers were less conserved than commonly expressed genes, and many markers were not shared between human and mouse. For example, chandelier cells express Vipr2 in mouse but COL15A1 and NOG in human (Extended Data Fig. 10d.). Interestingly, the same gene families that show cell type specificity in both species have changed patterning across cell types (Figs. 5a, 6d, Supplementary Table 6).

Serotonin receptors have highly divergent expression between species: 4 of 7 GPCRs and both ionotropic receptor subunits (HTR3A, HTR3B) were in the top 10% most divergent genes (Fig. 6e). The most divergent gene families include neurotransmitter receptors, ion channels, extracellular matrix elements, and cell adhesion molecules. Among the top 3% most divergent genes (Supplementary Table 5), the collagens COL24A1 and COL12A1 and glutamate receptor subunits GRIK1 and GRIN3A were expressed in different cell types between species and were validated to have different laminar distributions in human and mouse (Fig. 6f, g). The cumulative effect of so many differences in the cellular patterning of genes with well characterized roles in neuronal signaling and connectivity is certain to cause many differences in human cortical circuit function.

Discussion

Single cell transcriptomics enables systematic characterization of cellular diversity in the brain, allowing a paradigm shift in neuroscience from historical emphasis on cellular anatomy to molecular classification of cell types. Echoing early anatomical studies 11, dense sampling of mouse cortex using scRNA-seq demonstrated great cellular diversity 21,22. Here, similar sampling defines 75 cell types representing non-neuronal (6), excitatory (24) and inhibitory (45) cells in human MTG. Notably, robust cell typing was achieved despite increased biological and technical variability between individual human brains. Importantly, using these methods to study the cellular architecture of the human brain and identify homologous cell types enables predictions about properties not possible to directly measure in human and generates hypotheses about conserved and divergent cell features.

Despite differences across data sets, alignment based on expression co-variation reveals a cellular architecture largely conserved between cortical areas and species, as anatomical studies have shown for the last century. Here, mouse scRNA-seq was compared to human snRNA-seq, but to mitigate this, expression levels were estimated using nuclear intronic sequence 26. Additionally, young adult transgenic mice were compared to genetically diverse older humans, but prior studies show stable gene expression in adulthood 50. Finally, human MTG was compared to non-homologous mouse cortical areas. Although a matched analysis is preferable, primary visual cortex is specialized in human and likely highly divergent from mouse. Matching the human MTG taxonomy to mouse V1 and ALM taxonomies may seem at odds with the finding that excitatory neurons in mouse V1 and ALM cluster separately 22, but the magnitude of differential gene expression between cortical areas in mouse is small compared to that between species. Beyond similarities in overall diversity and hierarchical organization, most cell types mapped at the subclass level, 7 cell types mapped 1-to-1, and no major classes had missing homologous types despite the last common ancestor between humans and mice living at least 65 million years ago 51 and despite the thousand-fold difference in brain size and number of cells. Therefore, the transcriptomic organization of cell classes and subclasses appears conserved, with species and regional variation found at the finest level of cell type distinction.

Our results demonstrate species divergence of gene expression between homologous cell types, as shown at the single gene 15 and gross structural level 16. These differences are likely functionally relevant, as divergent genes are associated with connectivity and signaling, and many cell type markers have divergent expression. Notably, serotonin receptors are the second most divergent gene family, challenging the use of mouse models for many neuropsychiatric disorders involving serotonin signaling 52. Homologous cell types can have highly divergent features in concert with divergent gene expression. For example, interlaminar astrocytes correspond to 1 of 2 human transcriptomic astrocyte types. Similarly, 2 astrocyte types were described in mouse cortex 21, including a L1 type that lacks the long processes of interlaminar astrocytes. Thus, a 10-fold size increase and formation of long processes 13 are evolutionary variations on a conserved cell type. We observed several other evolutionary changes including differences in proportions of inhibitory neuron classes consistent with increased CGE generation of interneurons in human 36. Additionally, putative human L5 ET neurons are reduced in frequency (<1% in human versus ~20% in mouse), likely reflecting the 1200-fold expansion of human cortex relative to mouse compared to only 60-fold expansion of sub-cortical regions that these neurons target 2,3.

These observations quantitatively frame the debate of whether human cortex is different from other mammals 10,11, revealing basic transcriptomic similarity of cell types punctuated by differences in proportions and gene expression between species that likely influence microcircuit function. Furthermore, these results help resolve the paradox of conserved structure across mammals but failures in use of mouse for pre-clinical studies 52,53, and highlight the need to analyze human brain in addition to model organisms. The magnitude of differences between human and mouse suggests similar profiling of closely related non-human primates is necessary to study many aspects of human brain structure and function. The enhanced resolution afforded by these molecular technologies also has great promise for accelerating mechanistic understanding of brain evolution and disease.

Methods

Ethical compliance

De-identified postmortem human brain tissue was collected after obtaining permission from decedent next-of-kin. The Western Institutional Review Board (WIRB) reviewed the use of de-identified postmortem brain tissue for research purposes and determined that, in accordance with federal regulation 45 CFR 46 and associated guidance, the use of and generation of data from de-identified specimens from deceased individuals did not constitute human subjects research requiring insititutional review board (IRB) review. Postmortem tissue collection was performed in accordance with the provisions of the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act described in Health and Safety Code §§ 7150, et seq., and other applicable state and federal laws and regulations.

Tissue procurement from neurosurgical donors was performed outside of the supervision of the Allen Institute at local hospitals, and tissue was provided to the Allen Institute under the authority of the IRB of each participating hospital. A hospital-appointed case coordinator obtained informed consent from donors prior to surgery. Tissue specimens were de-identified prior to receipt by Allen Institute personnel. The specimens collected for this study were apparently non-pathological tissues removed during the normal course of surgery to access underlying pathological tissues. Tissue specimens collected were determined to be non-essential for diagnostic purposes by medical staff and would have otherwise been discarded.

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Allen Institute for Brain Science (Protocol No. 1511). Mice were provided food and water ad libitum, maintained on a regular 12-h day/night cycle, and housed in cages with various enrichment materials added, including nesting materials, gnawing materials, and plastic shelters.

Post-mortem tissue donors

Males and females 18 – 68 years of age with no known history of neuropsychiatric or neurological conditions (‘control’ cases) were considered for inclusion in this study (Extended Data Table 1). Routine serological screening for infectious disease (HIV, Hepatitis B, and Hepatitis C) was conducted using donor blood samples and only donors negative for all three tests were considered for inclusion in the study. Tissue RNA quality was assessed using an Agilent Bioanalyzer-generated RNA Integrity Number (RIN) and Agilent Bioanalyzer electropherograms for 18S/28S ratios. Specimens with RIN values ≥7.0 were considered for inclusion in the study (Extended Data Table 1).

Processing of whole brain postmortem specimens

Whole postmortem brain specimens were transported to the Allen Institute on ice. Standard processing of whole brain specimens involved bisecting the brain through the midline and embedding of individual hemispheres in Cavex Impressional Alginate for slabbing. Coronal brain slabs were cut at 1cm intervals through each hemisphere and individual slabs were frozen in a slurry of dry ice and isopentane. Slabs were then vacuum sealed and stored at −80°C until the time of further use.

Middle temporal gyrus (MTG) was identified on and removed from frozen slabs of interest, and subdivided into smaller blocks for further sectioning. Individual tissue blocks were processed by thawing in PBS supplemented with 10mM DL-Dithiothreitol (DTT, Sigma Aldrich), mounting on a vibratome (Leica), and sectioning at 500μm in the coronal plane. Sections were placed in fluorescent Nissl staining solution (Neurotrace 500/525, ThermoFisher Scientific) prepared in PBS with 10mM DTT and 0.5% RNasin Plus RNase inhibitor (Promega) and stained for 5 min on ice. After staining, sections were visualized on a fluorescence dissecting microscope (Leica) and cortical layers were individually microdissected using a needle blade micro-knife (Fine Science Tools).

Processing of neurosurgical tissue samples

Neurosurgical tissue was transported to the Allen Institute in chilled, oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) consisting of the following: 0.5 mM calcium chloride (dehydrate), 25 mM D-glucose, 20 mM HEPES, 10 mM magnesium sulfate, 1.2 mM sodium phosphate monobasic monohydrate, 92 mM N-methyl-d-glucamine chloride (NMDG-Cl), 2.5 mM potassium chloride, 30 mM sodium bicarbonate, 5 mM sodium L-ascorbate, 3 mM sodium pyruvate, and 2 mM thiourea. The osmolality of the solution was 295-305 mOsm/kg and the pH was 7.3. Slices were prepared using a Compresstome VF-200 or VF-300 vibratome (Precisionary Instruments). After sectioning, slices were recovered in ACSF containing 2 mM calcium chloride (dehydrate), 25 mM D-glucose, 20 mM HEPES, 2 mM magnesium sulfate, 1.2 mM sodium phosphate monobasic monohydrate, 2.5 mM potassium chloride, 30 mM sodium bicarbonate, 92 mM sodium chloride, 5 mM sodium L-ascorbate, 3 mM sodium pyruvate, and 2 mM thiourea at room temperature for at least 1 hour. After the recovery period, slices were transferred to RNase-free microcentrifuge tubes, snap frozen, and stored at −80°C until the time of use. Microdissection of cortical layers was carried out on tissue slices that were thawed and stained as described above for postmortem tissue.

Nucleus sampling plan

Nuclei were sampled from 8 total human donors (4 male, 4 female; 4 postmortem, 4 neurosurgical; 24-66 years of age). To evenly survey cell type diversity across cortical layers, nuclei were sampled based on relative proportions of neurons in each cortical layer 54. We estimated that 16 cells were required to reliably discriminate two closely related Sst+ interneuron types reported by Tasic et al. 20. Monte Carlo simulations were used to estimate the sampling depth N needed to be 95% confident that at least 16 nuclei of frequency f have been selected from the population. Calculating N for a range of f revealed a simple linear approximation: N = 28 / f. Subtypes of mouse cortical layer 5 projection neurons can be rarer than 1% of the population 48, so we targeted neuron types as rare as 0.2% of all cortical neurons. Based on Monte Carlo simulations, we estimated that 14,000 neuronal nuclei were needed to target types as rare as 0.2% of the total neuron population. Using an initial subset of RNA-seq data, we observed more transcriptomic diversity in layers 1, 5, and 6 than in other layers so additional neuronal nuclei (~1000) were sampled from those layers. We also targeted 1500 (10%) non-neuronal (NeuN-) nuclei and obtained approximately 1000 nuclei that passed quality control (QC, see below), and we expected to capture types as rare as 3% of the non-neuronal population. Therefore, the final dataset contained <10% non-neuronal nuclei because nearly 50% of NeuN-negative nuclei failed QC, potentially due to the lower RNA content of glia compared to neurons 22.

Nucleus isolation and sorting

Microdissected tissue pieces were placed in into nuclei isolation medium containing 10mM Tris pH 8.0 (Ambion), 250mM sucrose, 25mM KCl (Ambion), 5mM MgCl2 (Ambion) 0.1% Triton-X 100 (Sigma Aldrich), 1% RNasin Plus, 1X protease inhibitor (Promega), and 0.1mM DTT in 1ml Dounce homogenizer (Wheaton). Tissue was homogenized using 10 strokes of the loose Dounce pestle followed by 10 strokes of the tight pestle and the resulting homogenate was passed through 30μm cell strainer (Miltenyi Biotech) and centrifuged at 900xg for 10 min to pellet nuclei. Nuclei were resuspended in buffer containing 1X PBS (Ambion), 0.8% nuclease-free BSA (Omni-Pur, EMD Millipore), and 0.5% RNasin Plus. Mouse anti-NeuN conjugated to PE (EMD Millipore) was added to preparations at a dilution of 1:500 and samples were incubated for 30 min at 4°C. Control samples were incubated with mouse IgG1k-PE Isotype control (BD Pharmingen). Samples were then centrifuged for 5 min at 400xg to pellet nuclei and pellets were resuspended in 1X PBS, 0.8% BSA, and 0.5% RNasin Plus. DAPI (4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, ThermoFisher Scientific) was applied to nuclei samples at a concentration of 0.1μg/ml.

Single nucleus sorting was carried out on either a BD FACSAria II SORP or BD FACSAria Fusion instrument (BD Biosciences) using a 130μm nozzle. A standard gating strategy was applied to all samples. First, nuclei were gated on their size and scatter properties and then on DAPI signal. Doublet discrimination gates were used to exclude nuclei aggregates. Lastly, nuclei were gated on NeuN signal (PE). Ten percent of nuclei were intentionally sorted as NeuN-negative and the remaining 90% of nuclei were NeuN-positive. Single nuclei were sorted into 8-well strip tubes containing 11.5μl of SMART-seq v4 collection buffer (Takara) supplemented with ERCC MIX1 spike-in synthetic RNAs at a final dilution of 1×10-8 (Ambion). Strip tubes containing sorted nuclei were briefly centrifuged and stored at −80°C until the time of further processing. Index sorting was carried out for most samples to allow properties of nuclei detected during sorting to be connected with the cell type identity revealed by subsequent snRNA-seq.

RNA-sequencing

We used the SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input RNA Kit for Sequencing (Takara #634894) per the manufacturer’s instructions for reverse transcription of RNA and subsequent cDNA amplification. Standard controls were processed alongside each batch of experimental samples. Control strips included: 2 wells without cells, 2 wells without cells or ERCCs (i.e. no template controls), and either 4 wells of 10 pg of Human Universal Reference Total RNA (Takara 636538) or 2 wells of 10 pg of Human Universal Reference and 2 wells of 10 pg Control RNA provided in the Clontech kit. cDNA was amplified with 21 PCR cycles after the reverse transcription step. AMPure XP Bead (Beckman Coulter A63881) purification was done using an Agilent Bravo NGS Option A instrument with a bead ratio of 1x, and purified cDNA was eluted in 17 μl elution buffer provided by Takara. All samples were quantitated using PicoGreen® (ThermoFisher Scientific) on a Molecular Dynamics M2 SpectraMax instrument. cDNA libraries were examined on either an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 using High Sensitivity DNA chips or an Advanced Analytics Fragment Analyzer (96) using the High Sensitivity NGS Fragment Analysis Kit (1bp-6000bp). Purified cDNA was stored in 96-well plates at −20°C until library preparation.

The NexteraXT DNA Library Preparation (Illumina FC-131-1096) kit with NexteraXT Index Kit V2 Sets A-D (FC-131-2001, 2002, 2003, or 2004) was used for sequencing library preparation. NexteraXT DNA Library prep was done at either 0.5x volume manually or 0.4x volume on the Mantis instrument (Formulatrix). Three different cDNA input amounts were used in generating the libraries: 75pg, 100pg, and 125pg. AMPure XP bead purification was done using the Agilent Bravo NGS Option A instrument with a bead ratio of 0.9x and all samples were eluted in 22 μl of Resuspension Buffer (Illumina). Samples were quantitated using PicoGreen on a Molecular Bynamics M2 SpectraMax instrument. Sequencing libraries were assessed using either an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 with High Sensitivity DNA chips or an Advanced Analytics Fragment Analyzer with the High Sensitivity NGS Fragment Analysis Kit for sizing. Molarity was calculated for each sample using average size as reported by Bioanalyzer or Fragment Analyzer and pg/μl concentration as determined by PicoGreen. Samples were normalized to 2-10 nM with Nuclease-free Water (Ambion). Libraries were multiplexed at 96 samples per lane and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 instrument using Illumina High Output V4 chemistry. Libraries were sequenced at a median depth of 2.6 ± 0.5M reads/nucleus.

RNA-seq gene expression quantification

Raw read (fastq) files were aligned to the GRCh38 human genome sequence (Genome Reference Consortium, 2011) with the RefSeq transcriptome version GRCh38.p2 (current as of 4/13/2015) and updated by removing duplicate Entrez gene entries from the gtf reference file for STAR processing. For alignment, Illumina sequencing adapters were clipped from the reads using the fastqMCF program 55. After clipping, the paired-end reads were mapped using Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR) 56 using default settings. STAR uses and builds it own suffix array index which considerably accelerates the alignment step while improving on sensitivity and specificity, due to its identification of alternative splice junctions. Reads that did not map to the genome were then aligned to synthetic constructs (i.e. ERCC) sequences and the E.coli genome (version ASM584v2). The final results files included quantification of the mapped reads (raw exon and intron counts for the transcriptome-mapped reads). This quantification only includes uniquely mappable sequences, which makes up the vast majority of reads. A median of 88.4% of reads are uniquely mappable (range: 45.4-93.7%) compared with only 3.2% that are multi-mapping (range 1.6-10.1%), suggesting that any bias related to exclusion of multi-mappers would be relative minor. Also, part of the final results files are the percentages of reads mapped to the RefSeq transcriptome, to ERCC spike-in controls, and to E. coli, and summaries of these percentages are saved for quality control assessments. Quantification was performed using summerizeOverlaps from the R package GenomicAlignments 57. Read alignments to the genome (exonic, intronic, and intergenic counts) were visualized as beeswarm plots using the R package beeswarm.

Expression levels were calculated as counts per million (CPM) of exonic plus intronic reads, and log2(CPM + 1) transformed values were used for a subset of analyses as described below. Gene detection was calculated as the number of genes expressed in each sample with CPM > 0. CPM values reflected absolute transcript number and gene length, i.e. short and abundant transcripts may have the same apparent expression level as long but rarer transcripts. Intron retention varied across genes so no reliable estimates of effective gene lengths were available for expression normalization. Instead, absolute expression levels were estimated as fragments per kilobase per million (FPKM) using only exonic reads so that annotated transcript lengths could be used.

Quality control of RNA-seq data

Nuclei were included for clustering analysis if they passed all of the following QC thresholds:

>30% cDNA longer than 400 base pairs

>500,000 reads aligned to exonic or intronic sequence

>40% of total reads aligned

>50% unique reads

TA nucleotide ratio > 0.7

After clustering (see below), clusters were identified as outliers if more than half of nuclei co-expressed markers of inhibitory (GAD1, GAD2) and excitatory (SLC17A7) neurons or were NeuN+ but did not express the pan-neuronal marker SNAP25. Median values of QC metrics listed above were calculated for each cluster and used to compute the median and inter-quartile range (IQR) of all cluster medians. Clusters were also identified as outliers if the cluster median QC metrics deviated by more than three times the IQRs from the median of all clusters. In total, 15,928 nuclei passed QC criteria and were split into three broad classes of cells (10,708 excitatory neurons, 4,297 inhibitory neurons, and 923 non-neuronal cells) based on NeuN staining and cell class marker gene expression

Clusters were identified as donor-specific if they included fewer nuclei sampled from donors than expected by chance. For each cluster, the expected proportion of nuclei from each donor was calculated based on the laminar composition of the cluster and laminar sampling of the donor. For example, if 30% of layer 3 nuclei were sampled from a donor, then a layer 3-enriched cluster should contain approximately 30% of nuclei from this donor. In contrast, if only layer 5 were sampled from a donor, then the expected sampling from this donor for a layer 1-enriched cluster was zero. If the difference between the observed and expected sampling was greater than 50% of the number of nuclei in the cluster, then the cluster was flagged as donor-specific and excluded. In total, 325 nuclei were assigned to donor-specific or outlier clusters that contained marginal quality nuclei and were excluded from further analysis. Three donor-specific clusters came from neurosurgical donors (n=95 nuclei) and were similar to other layer 5 types reported in our analysis, but had higher expression of activity-dependent genes.

To confirm exclusion, clusters automatically flagged as outliers or donor-specific were manually inspected for expression of broad cell class marker genes, mitochondrial genes related to quality, and known activity-dependent genes.

Clustering RNA-seq data

Nuclei and cells were grouped into transcriptomic cell types using an iterative clustering procedure based on community detection in a nearest neighbor graph as described in Bakken et al. 26. Briefly, intronic and exonic read counts were summed, and log2-transformed expression (CPM + 1) was centered and scaled across nuclei. X- and Y-chromosome were excluded to avoid nuclei clustering based on sex. Many mitochondrial genes had expression that was correlated with RNA-seq data quality, so nuclear and mitochondrial genes downloaded from Human MitoCarta2.0 58 were excluded. Differentially expressed genes were selected while accounting for gene dropouts, and principal components analysis (PCA) was used to reduce dimensionality. Nearest-neighbor distances between nuclei were calculated using up to 20 principal components, Jaccard similarity coefficients were computed, and Louvain community detection was used to cluster this graph with 15 nearest neighbors. Marker genes were defined for all cluster pairs using two criteria: 1) significant differential expression (>2-fold; Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate < 0.01) using the R package limma and 2) binary expression (CPM > 1 in more the half of nuclei in one cluster and <30% of this proportion in the second cluster). Pairs of clusters were merged if either cluster lacked at least one marker gene. Clustering was then applied iteratively to each sub-cluster until the occurrence of one of four stop criteria: 1) fewer than six nuclei (due to a minimum cluster size of three), 2) no significantly variable genes, 3) no significantly variable PCs, 4) no significant clusters.

To assess the robustness of clusters, the iterative clustering procedure described above was repeated 100 times for random subsets of 80% of nuclei. A co-clustering matrix was generated that represented the proportion of clustering iterations that each pair of nuclei were assigned to the same cluster. We defined consensus clusters by iteratively splitting the co-clustering matrix as described in Tasic et al. 2018 22. We used the co-clustering matrix as the similarity matrix and clustered using either Louvain (>= 4000 nuclei) or Ward’s algorithm (< 4000 nuclei). We defined Nk,l as the average probabilities of nuclei within cluster k to co-cluster with nuclei within cluster l. We merged clusters k and l if Nk,l > max(Nk,k, Nl,l) - 0.25 or if the sum of −log10(adjusted P-value) of differentially expressed genes between clusters k and l was less than 150. Finally, we refined cluster membership by reassigning each nucleus to the cluster to which it had maximal average co-clustering. We repeated this process until cluster membership converged.

Next, we assessed the robustness of clusters using a similar clustering pipeline that was recently used to identify cortical cell types in mouse V1 and ALM 22. This pipeline closely resembled the analysis described above except for three differences. First, this pipeline required that differentially expressed genes between all cluster pairs had more highly significant p-values, and this penalized small clusters from splitting into sub-clusters. Second, the pipeline used Ward’s agglomerative hierarchical clustering instead of Louvain community detection for iterations with fewer than 3000 nuclei. Ward’s method was computationally less efficient but improved detection of cluster heterogeneity when large and small clusters were present due to the well-known resolution of community detection algorithms that optimize global modularity 59. Third, dimensionality reduction could be performed using WGCNA 60 rather than PCA, and this method was empirically more sensitive to subtle expression variation but also technical noise. This pipeline was run with four parameter settings, and the clustering results were compared to the reference clusters defined by the initial clustering pipeline. Confusion matrices were computed for each comparison and the Jaccard index was computed for all cluster pairs, and these results were summarized using boxplots (Extended Data Fig. 3e).

The final set of clusters were compared to nearest neighboring clusters and the number of differentially expressed genes (>2-fold change, Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate < 0.01) and binary marker genes (CPM > 1 in more the half of nuclei in one cluster and <30% of this proportion in the second cluster) were quantified and compared (Extended Data Fig. 3b) to the proportion of binary markers that were unannotated (i.e. “LOC” genes). If more markers were required to separate each cluster from its nearest neighbor, then clusters were merged and visualized as a river plot (Extended Data Fig. 3c). Clusters recently defined in mouse V1 and ALM required at least 4 binary markers (8 total markers with higher or lower expression than the nearest neighboring cluster) 22. 63 clusters in human MTG have at least 4 markers and are reported in Supplementary Table 2 along with markers selected as described below.

Cluster names were defined using an automated strategy which combined molecular information (marker genes) and anatomical information (layer of dissection). Clusters were assigned a broad class of interneuron, excitatory neuron, microglia, astrocyte, oligodendrocyte precursor, oligodendrocyte, or endothelial cell based on maximal median cluster CPM of GAD1, SLC17A7, TYROBP, AQP4, PDGFRA, OPALIN, or NOSTRIN, respectively. Enriched layers were defined as the range of layers which contained at least 10% of the total cells from that cluster. Clusters were then assigned a broad marker, defined by maximal median CPM of PAX6, LAMP5, VIP, SST, PVALB, LINC00507, RORB, THEMIS, FEZF2, TYROBP, FGFR3, PDGFRA, OPALIN, or NOSTRIN. Finally, clusters in all broad classes with more than one cluster (e.g., interneuron, excitatory neuron, and astrocyte) were assigned a gene showing the most specific expression in that cluster (see details below). We developed a principled nomenclature for clusters based on: 1) major cell class, 2) layer enrichment (including layers containing at least 10% of nuclei in that cluster), 3) a subclass marker gene (maximal expression of 14 manually-curated genes), and 4) a cluster-specific marker gene (maximal detection difference compared to all other clusters). For example, the left-most inhibitory neuron type in Figure 1c, found in samples dissected from layers 1 and 2, and expressing the subclass marker PAX6 and the specific marker CDH12, is named Inh L1-2 PAX CDH12. A few cluster names were manually adjusted for clarity.

Marker gene selection

Scoring cluster marker genes

Many genes were expressed in the majority of nuclei in a subset of clusters. A marker score (beta) was defined for all genes to measure how binary expression was among clusters, independent of the number of clusters labeled (Supplementary Table 5). First, the proportion (xi) of nuclei in each cluster that expressed a gene above background level (CPM > 1) was calculated. Then, scores were defined as the squared differences in proportions normalized by the sum of absolute differences plus a small constant (ε) to avoid division by zero. Scores ranged from 0 to 1, and a perfectly binary marker had a score equal to 1.

Specific cell type marker genes

Specific marker genes were selected for cell type naming and generation of violin plots and heat maps, and are included as part of Supplementary Table 2. For each cell type, the top marker genes were selected by filtering and sorting: first, only genes with highest proportion (CPM>1) in the target cluster compared with every other cluster and with median expression at least two-fold higher than in every other cluster were considered; and second, genes were filtered based on the difference in median expression in the top cluster compared with cluster with the next-highest median expression. The highest-ranked annotated gene (e.g., not a “LOC” or related gene) was selected as the specific gene to include in each cluster name. In clusters with no specific markers fold-change requirement was relaxed, and if still no marker was found then the most specific gene compared with similar cell types (category level 3) was used (see Supplementary Table 2).

Combinatorial cell type marker genes

Combinatorial marker genes were identified using NS-Forest v261 (https://github.com/JCVenterInstitute/NSForest), an algorithm designed to select the minimum number of genes whose combined expression pattern is sufficient to uniquely classify cells of a particular type based on gene expression clustering results. Briefly, for each gene expression cluster, NS-Forest produces a Random Forest (RF) model for a target cluster vs all other clusters binary classification. The top ranking genes (features) from each RF are then filtered by expression level (positive intermediate-high expression) and reranked by Binary Score. The Binary Score is calculated by first finding median cluster expression values for a given gene in each cluster. These values are then scaled by dividing by the median expression value in the target cluster. Next, we take one minus this scaled value such that the value will be 0 for the target cluster and 1 for clusters that have no expression (negative scaled values are set to 0). These values are then summed and normalized by dividing by the total number of clusters. In the ideal case, where all off-target clusters have no expression, the resulting Binary Score is 1. Finally, for the top 6 genes ranked by this Binary Score, optimal expression level cutoffs are determined using single decision trees, and all permutations of these genes are evaluated for classification accuracy using the f-beta score, where the beta is weighted to favor precision. This f-score indicates the power of discrimination for a cluster and a given set of genes. Top combinatorial markers are included as part of Supplementary Table 2.

Donor tissue-specific marker genes

Gene expression was compared between nuclei isolated from four neurosurgical and four post-mortem donors. Differential expression analysis was performed with the limma R package using all NeuN+-positive nuclei isolated from layer 5 of MTG. Donor sex and MTG cluster were included as covariates in a linear model, and all genes with at least a 2-fold difference in expression and Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p-value < 0.05 are reported in Supplementary Table 1.

Cross-species marker genes

For each homologous cell type, cross-species markers were defined as having cluster-enriched expression (expressed in >50% of cells or nuclei in the cluster of interest and five or fewer additional clusters) in both species. Marker genes were rank ordered based on their cell type-specificity in human and mouse using a tau score defined in Yanai et al. 62. Up to 10 markers were plotted in Extended Data Figure 11 and listed in Supplementary Table 4.

Assigning core and intermediate nuclei

We defined core and intermediate nuclei as described in 22. Specifically, we used a nearest-centroid classifier, which assigns a nucleus to the cluster whose centroid has the highest Pearson’s correlation with the nucleus. Here, the cluster centroid is defined as the median expression of the 1200 marker genes with the highest beta score. To define core vs. intermediate nuclei, we performed 5-fold cross-validation 100 times. In each round, the nuclei were randomly partitioned into 5 groups, and nuclei in each group of 20% of the nuclei were classified by a nearest centroid classifier trained using the other 80% of the nuclei. A nucleus classified to the same cluster as its original cluster assignment more than 90 times was defined as a core nucleus, the others were designated intermediate nuclei. We define 14,204 core nuclei and 1,399 intermediate nuclei, which in most cases classify to only 2 clusters (1,345 out of 1,399, 96.1%). Most nuclei are defined as intermediate because they are confidently assigned to a different cluster from the one originally assigned (1,220 out of 1,399, 87.2%) rather than because they are not confidently assigned to any cluster.

Cluster dendrograms

Clusters were arranged by transcriptomic similarity based on hierarchical clustering. First, the average expression level of the top 1200 marker genes (highest beta scores, as above) was calculated for each cluster. A correlation-based distance matrix () was calculated, and complete-linkage hierarchical clustering was performed using the “hclust” R function with default parameters. The resulting dendrogram branches were reordered to show inhibitory clusters followed by excitatory clusters, with larger clusters first, while retaining the tree structure. Note that this measure of cluster similarity is complementary to the co-clustering separation described above. For example, two clusters with similar gene expression patterns but a few binary marker genes may be close on the tree but highly distinct based on co-clustering.

Organizing clusters into a provisional cell ontology

Annotations for gene expression cluster characteristics were used to produce a provisional cell ontology representation as proposed 37, accessible through the BioPortal resource (https://bioportal.bioontology.org/ontologies/PCL) and an RDF representation available through a GitHub Repo (https://github.com/mkeshk2018/Provisional_Cell_Ontology). This ontology is presented in table form in Supplementary Table 3, along with more details about the components of this ontology.

Mapping cell types to reported clusters

69 neuronal clusters in MTG were matched to 16 neuronal clusters reported by Lake et al. 24 using nearest-centroid classifier of expression signatures. Specifically, single nucleus expression data was downloaded for 3,042 cells and 25,051 genes. 1,359 marker genes (beta score > 0.4) of MTG clusters that had a matching gene in the Lake et al. dataset were selected, and the median expression for these genes was calculated for all MTG clusters. Next, Pearson’s correlations were calculated between each nucleus in the Lake et al. dataset and all 69 MTG clusters based on these 1,359 genes. Nuclei were assigned to the cluster with the maximum correlation. A confusion matrix was generated to compare the cluster membership of nuclei reported by Lake et al. and assigned MTG cluster. The proportion of nuclei in each MTG cluster that were members of each of the 16 Lake et al. clusters were visualized as a dot plot with circle sizes proportional to frequency and colored by MTG cluster color. The same comparative approach was performed for clusters defined using single nuclei isolated from prefrontal cortex, including 10,319 nuclei from Lake et al. 27 and 5,433 nuclei from Habib et al. 28.

Colorimetric in situ hybridization

In situ hybridization (ISH) data for human and mouse cortex was from the Allen Human Brain Atlas and Allen Mouse Brain Atlas. All ISH data is publicly accessible at www.brain-map.org. Data was generated using a semi-automated technology platform as described 63, with modifications for postmortem human tissues as previously described 15. Digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes were generated for each human gene such that they would have >50% overlap with the orthologous mouse gene in the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas 63. ISH experiments shown in Figure 6 were repeated 4 (COL24A1), 3 (COL12A1, GRIK1), and 6 (GRIN3A) times for human, and 2 (Col24a1, Col12a1, Grin3a) and 6 (Grik1) times for mouse.

GFAP immunohistochemistry

Tissue slices (350 μm) from neurosurgical specimens were fixed for 2-4 days in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4°C, washed in PBS, and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose. Cryoprotected slices were frozen and re-sectioned at 30 μm using a sliding microtome (Leica SM2000R). Free floating sections were mounted onto gelatin coated slides and dried overnight at 37 °C. Slides were washed in 1X tris buffered saline (TBS), followed by incubation in 3% hydrogen peroxide in 1X TBS. Slides were then heated in sodium citrate (pH 6.0) for 20 minutes at 98 °C. After cooling, slides were rinsed in MilliQ water followed by 1X TBS. Primary antibody (mouse anti-GFAP, EMD Millipore, #MAB360, clone GA5, 1:1500) was diluted in Renaissance Background Reducing Diluent (Biocare #PD905L). Slides were processed using a Biocare intelliPATH FLX Automated Slide Stainer. After primary antibody incubation, slides were incubated in Mouse Secondary Reagent (Biocare #IPSC5001G20), rinsed with 1X TBS, incubated in Universal HRP Tertiary Reagent (Biocare #IPT5002G20), rinsed in 1X TBS, and incubated in IP FLXDAB (Biocare Buffer #IPBF5009G20), and DAB chromogen (Biocare Chromogen #IPC5008G3). Slides were then rinsed in 1X TBS, incubated in DAB sparkle (Biocare #DSB830M), washed in MilliQ water, dehydrated through a series of graded alcohols, cleared with Formula 83, and coverslipped with DPX. Slides were imaged using an Aperio ScanScope XT slide scanner (Leica).

Multiplex fluorescence in situ hybridization (mFISH)

Genes were selected for mFISH experiments that discriminated cell types and broader classes by visual inspection of differentially expressed genes that had relatively binary expression in the targeted types.

Single molecule FISH (smFISH)

Fresh-frozen human brain tissue from the MTG was sectioned at 10um onto Poly-L-lysine coated coverslips as described previously 64, let dry for 10 min at room temperature, then fixed for 15 min at 4 C in 4% PFA. Sections were washed 3 × 10 min in PBS, then permeabilized and dehydrated with 100% isopropanol at room temperature for 3 min and allowed to dry. Sections were stored at −80 C until use. Frozen sections were rehydrated in 2XSSC (Sigma Aldrich 20XSSC, 15557036) for 5 min, then treated 2 X 5 min with 4%SDS (Sigma Aldrich, 724255) and 200mM boric acid (Sigma Aldrich, cat# B6768) pH 8.5 at room temperature. Sections were washed 3 times in 2X SSC, then once in TE pH 8 (Sigma Aldrich, 93283). Sections were heatshocked at 70 C for 10 min in TE pH 8, followed by 2XSSC wash at room temperature. Sections were then incubated in hybridization buffer (10% Formamide (v/v, Sigma Aldrich 4650), 10% Dextran Sulfate (w/v, Sigma Aldrich D8906), 200μg/mL BSA (Ambion AM2616), 2 mM Ribonucleoside vanadyl complex (New England Biolabs, S1402S), 1mg/ml tRNA (Sigma 10109541001) in 2XSSC) for 5 min at 38.5 C. Probes were diluted in hybridization buffer at a concentration of 250 nM and hybridized at 38.5 C for 2 h. Following hybridization, sections were washed 2 X 15 min at 38.5 C in wash buffer (2XSSC, 20% Formamide), and 1 X 15 min in wash buffer with 5 μg/ml DAPI (Sigma Aldrich, 32670). Sections are then imaged in Imaging buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 50 mM NaCl, 0.8% Glucose (Sigma Aldrich, G8270), 3 U/ml Glucose Oxidase (Sigma Aldrich, G2133), 90 U/ml Catalase (Sigma Aldrich, C3515). Following imaging, sections were incubated 3 X 10 min in stripping buffer (65% Formamide, 2X SSC) at 30 C to remove hybridization probes from the first round. Sections were then washed in 2X SSC for 3 X 5 min at room temperature prior to repeating the hybridization procedure.

RNAscope mFISH

Human tissue specimens used for RNAscope mFISH came from a cohort of both neurosurgical or postmortem tissue donors that were independent from the donors used for snRNA-seq. Mouse tissue for RNAscope experiments was from adult (P56 +/− 3 days) wildtype C57Bl/6J mice. Mice were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane and intracardially perfused with either 25 or 50 ml of ice cold, oxygenated artificial cerebral spinal fluid (0.5mM CaCl2, 25mM D-Glucose, 98mM HCl, 20mM HEPES, 10mM MgSO4, 1.25mM NaH2PO4, 3mM Myo-inositol, 12mM N-acetylcysteine, 96mM N-methyl-D-glucamine, 2.5mM KCl, 25mM NaHCO3, 5mM sodium L-Ascorbate, 3mM sodium pyruvate, 0.01mM Taurine, and 2mM Thiourea). The brain was then rapidly dissected, embedded in optimal cutting temperature (O.C.T.) medium, and frozen in a slurry of dry ice and ethanol. Tissues were stored at −80C until for later cryosectioning.

Fresh-frozen mouse or human tissues were sectioned at 14-16 μm onto Superfrost Plus glass slides (Fisher Scientific). Sections were dried for 20 minutes at −20C and then vacuum sealed and stored at −80C until use. The RNAscope multiplex fluorescent v1 kit was used per the manufacturer’s instructions for fresh-frozen tissue sections (ACD Bio), with the following minor modifications: (1) fixation was performed for 60 minutes in 4% paraformaldehyde in 1X PBS at 4°C, and (2) the protease treatment step was shortened to 10 minutes. Positive controls used to assess RNA quality in tissue sections were either from a set from ACD Bio (POLR2A, PPIB, UBC, #320861) or a brain-specific probe combination (SLC17A7, VIP, GFAP). Sections were imaged using either a 40X or 60X oil immersion lens on a Nikon TiE fluorescent microscope equipped with NIS-Elements Advanced Research imaging software (version 4.20). For all RNAscope mFISH experiments, positive cells were called by manually counting RNA spots for each gene. Cells were called as positive for a gene if they contained ≥ 5 RNA spots for that gene. Lipofuscin autofluorescence was distinguished from RNA spot signal based on the larger size of lipofuscin granules and the broad fluorescence spectrum of lipofuscin.

RNAscope mFISH with GFAP immunohistochemistry

Tissue sections were processed for RNAscope mFISH detection of ID3 (ACD Bio, #492181-C3, NM_002167.4) and AQP4 (ACD Bio, #482441, NM_001650.5 ) exactly as described above. At the end of the RNAscope protocol, sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature and then washed twice in 1X PBS for 5 minutes. Sections were incubated in blocking solution (10% normal donkey serum, 0.1% triton-x 100 in 1X PBS) for 30 minutes at room temperature and then incubated in primary antibody diluted 1:100 in blocking solution (mouse anti-GFAP, Sigma-Aldrich, #G3893, clone G-A-5) for 18 hours at 4C. Sections were then washed 3 times for 5 minutes each in 1X PBS, incubated with secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse IgG(H+L) Alexa Fluor 568 conjugate, ThermoFisher Scientific, #A-11004) for 30 minutes at room temperature, rinsed in 1X PBS 3 times for 5 minutes each, counterstained with DAPI (1 μg/ml), and mounted with ProLong Gold mounting medium (ThermoFisher Scientific). Sections were imaged using either a 40X or 60X oil immersion lens on a Nikon TiE fluorescent microscope equipped with NIS-Elements Advanced Research imaging software (version 4.20).

In situ validation of excitatory cell types and non-coding transcripts

To validate excitatory neuron types, clusters were labeled with cell type specific combinatorial gene panels using RNAscope mFISH. For each gene panel, positive cells were manually called by visual assessment of RNA spots for each gene, as described above. The total number of positive cells was quantified for each section. Positive cells were counted on at least three sections derived from at least two donors for each probe combination. DAPI staining was used to determine the boundaries of cortical layers within each tissue section and the laminar position of each positive cell was recorded. The percentage of labeled cells per layer, expressed as a fraction of the total number of labeled cells summed across all layers, was calculated for each type. Probes used were as follows (all from ACD Bio): SLC17A7 (#415611, NM_020309.3 ), RORB (#446061, #446061-C2, NM_006914.3), CNR1 (#591521-C2, NM_001160226.1), PRSS12 (#493931-C3, NM_003619.3 ), ALCAM (#415731-C2, NM_001243283.1), MET (#431021, NM_001127500.1), MME (#410891-C2, NM_007289.2 ), NTNG1 (#446101-C3, NM_001113226.1), HS3ST4 (#506181, NM_006040.2), CUX2 (#425581-C3, NM_015267.3), PCP4 (#446111, NM_006198.2), GRIN3A (#534841-C3, NM_133445.2), GRIK3 (#493981, NM_000831.3), CRHR2 (#469621, NM_001883.4), TPBG (#405481, NM_006670.4), POSTN (#409181-C3, NM_006475.2), SMYD1 (#493951-C2, NM_001330364.1). Probes for non-coding transcripts were as follows (all from ACD Bio): LINC01164 (# 559051-C3, NR_038365.1), LOC102723415 (#559031, XR_001741660.1), LOC401134 (LINC02232, #559061-C3, NR_033976.1), LOC105369818 (#508351-C3, XR_945055.2), IFNG-AS1 (#508348-C2, NR_104124.1). LOC105376081 (XR_929926.1) was assayed using colorimetric ISH as described above.

Imaging and quantification of smFISH expression

smFISH images were collected using an inverted microscope in an epifluorescence configuration (Zeiss Axio Observer.Z1) with a 63x oil immersion objective with numerical aperture 1.4. The sample was positioned in x, y and z with a motorized x, y stage with linear encoders and z piezo top-plate (Applied Scientific Instruments MS 2000-500) and z stacks with 300 nm plane spacing were collected in each color at each stage position through the entire z depth of the sample. Fluorescence emission was filtered using a high-speed filterwheel (Zeiss) directly below the dichroic turret and imaged onto a sCMOS camera (Hamamatsu ORCA Flash4.0) with a final pixel size of 100 nm. Images were collected after each round of hybridization using the same configuration of x,y tile locations, aligned manually before each acquisition based on DAPI fluorescence. smFISH signal was observed as diffraction-limited spots which were localized in 3D image stacks by finding local maxima after spatial bandpass filtering. These maxima were filtered for total intensity and radius to eliminate dim background and large, bright lipofuscin granules. Outlines of cells and cortical layers were manually annotated on images of GAD, SLC17A7 and DAPI as 2D polygons using FIJI. The number of mRNA molecules in each cell for each gene was then calculated and converted to densities (spots per 100 μm2).

Background expression of the excitatory neuron marker SLC17A7 was defined as the 95th quantile of SLC17A7 spot density among cells in cortical layer 1, since no excitatory cells should be present in layer 1. Excitatory neurons were defined as any cell with SLC17A7 spot density greater than this threshold. To map excitatory cells to MTG reference clusters, spot counts were log-transformed and scaled so that the 90th quantile of expression for each gene in smFISH matched the maximum median cluster expression of that gene among the reference clusters. Reference clusters that could not be discriminated based on the smFISH panel of nine genes were merged and all comparisons between smFISH and RNA-seq cluster classes were performed using these cluster groups. Scaled spot densities for each cell were then compared to median expression levels of each reference cluster using Pearson correlation, and each cell was assigned to the cluster with the highest correlation. For cells that mapped to the Exc L2-3 LINC00507 FREM3 cluster, LAMP5 and COL5A2 expression was plotted as a dot plot where the size and color of dots corresponded to probe spot density and the location corresponded to the in situ location.

In situ validation of putative chandelier cells

Tissue sections were labeled with the gene panel GAD1, PVALB, and NOG, or COL15A1, specific markers of the Inh L2-5 PVALB SCUBE3 putative chandelier cell cluster. Probes were as follows (all from ACD Bio): GAD1 (#404031-C3, NM_000817.2), PVALB (#422181-C2, NM_002854.2), NOG (#416521, NM_005450.4), COL15A1 (#484001, NM_001855.4). Counts were conducted on sections from 3 human tissue donors. For each donor, the total number of GAD1+, PVALB+ and NOG+ cells was summed across multiple sections. The laminar position of each cell, based on boundaries defined by assessing DAPI staining patterns in each tissue section, was recorded. The proportion of chandelier cells in each layer was calculated as a fraction of the total number of GAD1+/PVALB+/NOG+ cells summed across all layers for each specimen.

Cell counts of broad interneuron classes