Abstract

Background:

As part of the ongoing Collaborative Study of the Genetics of Alcoholism, we performed a longitudinal study of a high risk cohort of adolescents/young adults from families with a proband with an alcohol use disorder, along with a comparison group of age-matched controls. The intent was to compare the development of alcohol problems in subjects at risk with and without comorbid externalizing and internalizing psychiatric disorders.

Methods:

Subjects (N = 3286) were assessed with a structured psychiatric interview at 2 year intervals over 10 years (2004–2017). The age range at baseline was 12–21.

Results:

Subjects with externalizing disorders (with or without accompanying internalizing disorders) were at increased risk for the onset of an alcohol use disorder during the observation period. Subjects with internalizing disorders were at greater risk than those without comorbid disorders for onset of a moderate or severe alcohol use disorder. The statistical effect of comorbid disorders was greater in subjects with more severe alcohol use disorders. The developmental trajectory of drinking milestones and alcohol use disorders was also accelerated in those with more severe disorders.

Conclusions:

These results may be useful for counseling of subjects at risk who present for clinical care, especially those subjects manifesting externalizing and internalizing disorders in the context of a positive family history of an alcohol use disorder. We confirm and extend findings that drinking problems in subjects at greatest risk will begin in early adolescence.

Keywords: alcohol use disorders, high risk studies, family studies, externalizing disorders, internalizing disorders

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol problems typically develop in late adolescence and early adulthood, though they can manifest at any time during adult life. Early age at first drink has been shown in many analyses to be a powerful predictor of an alcohol use disorder (AUD) (see review in [1] Deutsch et al., 2013). Family history of alcohol dependence is known to increase risk by at least two fold [2](Nurnberger et al., 2004). Males are more likely than females to develop alcohol use disorders ([3] Hasin et al., 2007; [4] Delker et al., 2016; [5] Vasilenko et al., 2017), and this is true within families of alcohol-dependent probands as well as the general population ([2] Nurnberger et al., 2004). Recent data have shown that, in the US, African- Americans (AA) are less likely to develop an AUD than European- Americans (EA) ([6] Kessler et al., 1994; [7] Smith et al., 2006; [8] Huang et al., 2006; [9] Grant et al., 2015) though analysis over different age groups suggests that a different developmental course may characterize AUDs in African-Americans, with relatively later onset of disorders in comparison to EA groups ([10] Grant et al., 2012; [5] Vasilenko et al., 2017; [11] Liu and Mulia, 2018). It must be borne in mind that these rates are a moving target and there is evidence for relative increases of AUD in women and AA subjects compared to EA males over recent years ([12] Grant et al., 2017).

There is also a known risk relationship between other psychiatric disorders and alcohol use disorders. Persons with a mood disorder (especially bipolar disorder) have an increased lifetime risk for an alcohol use disorder, as compared with persons without mood disorders ([13] Glantz et al., 2009). The increased risk for a substance use disorder (alcohol or drugs) following onset of a mood disorder is perhaps most precisely demonstrated by [14] Plana-Ripoll et al. 2019, using a study of the Danish population that showed a cumulative risk of 20% for men and 10% for women for an SUD during the fifteen years following the onset of a mood disorder. This represents a hazard ratio of ~5 for a disorder severe enough to come to clinical attention. Adolescents with a mood disorder are at increased risk for onset of alcohol problems ([15] Kessler et al., 2012; [16] Boschloo et al., 2013) and vice versa ([17] Kandel et al., 1999). Mood disorder may be associated with the course of alcohol problems as well as onset ([18] Crum et al., 2018). Scores on an internalizing scale were correlated with risk for alcohol and other drug use disorders in a prior analysis of the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA) subjects ([19] Acion et al., 2019).

There is an extensive literature supporting the relationship of externalizing disorders to subsequent development of AUDs and this has formed the basis of certain typologies of AUD, including Types 1 and 2 ([20] Cloninger, 1987) and Types A and B ([21] Babor et al., 1992). Type 2 subjects are characterized by high novelty seeking, low harm avoidance, and low reward dependence ([20] Cloninger, 1987). They are more likely to be diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder and less likely to be able to abstain from alcohol. Type B subjects are more likely to have a history of childhood aggression and conduct disorder and less likely to have a sustained response to treatment in comparison to Type A subjects ([21] Babor et al., 1992). More recent studies also emphasize the role of externalizing disorders, such as conduct disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in increasing the risk for alcohol problems ([22] Kuperman et al., 2001; [23] Bucholz et al., 2017; [24] Groenman et al., 2017). Cannabis and tobacco use are also associated with increased risk for concomitant alcohol problems ([23] Bucholz et al., 2017).

We studied a sample at risk for the development of alcohol use disorder on the basis of family history. Initial assessment was done on all subjects in the age range 12–21. These subjects have been followed over time with assessments every two years for up to 10 years. The present report evaluates the relationship of comorbid externalizing and internalizing disorders to age of onset of an AUD in a group of adolescents/young adults at high risk for AUDs. We also compare the onset of two alcohol milestones (age of first drink, age of first regular drinking) in groups divided by AUD severity. We hypothesized that persons developing AUDs following the onset of externalizing and internalizing disorders would show earlier onset than those without those baseline disorders. We also hypothesized that more severe AUDs would show an earlier onset of alcohol-related developmental milestones such as age of first drink and age of first regular drinking. The present report is one of the first we are aware of that tracks the development of AUDs in the context of multiple comorbid disorders in a high risk group, and it shows that some subjects are at great risk for alcohol problems in very early adolescence.

METHODS

Our subjects were participants in the adolescent to young adult Prospective sample of COGA (N = 3286). The COGA study started in 1989 and families were recruited between 1989 and 1995. Each family was recruited through a proband with an alcohol use disorder (at that time [25] DSMIII-R and [26] Feighner), targeting successive admissions to treatment facilities. There was a family size requirement (at least two living first-degree relatives) with the idea of prioritizing larger families. All first-degree relatives were interviewed and families were extended through affected subjects (i.e., the identification of an affected uncle of the proband would then lead to invitations for interview of that uncle’s family members). The subjects in the present study were offspring of the proband (or in some cases second-degree relatives). The response rate for recruitment was about 70% or more (with some inter-site variation). More information about the COGA study may be found in [23] Bucholz et al., 2017 and [27] Reich et al., 1998. All offspring in the age range (12–21) at the start of follow-up (2006–2007) were included. Offspring reaching the age of 12 during the course of the study (2006–2019) were also included. Subjects were interviewed at two-year intervals with the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA-IV) interview [28] Bucholz et al., 1994. The mean age at first interview was 16.1 (3.3 SD) and the mean age at last interview 23.1 (5.0). Subjects had an average of 4.0 interviews (1.7). 50.9% were female, 64.9% were EA and 30.9% AA. Ethnicity was assigned based on genotypic data, or by self-report if genotypes were not available. Subjects were members of a case family (proband with alcohol dependence −86.7% of subjects) or a comparison family (families recruited from medical or dental clinics or motor vehicle records with no selection for presence or absence of psychopathology). Non-drinkers were not excluded from the sample. The study was approved by The Indiana University Institutional Review Board (IRB) (project code: 1011004039R009, October 12, 2018). Written informed consent for the research was obtained from all participants in the study.

All subjects in the study were invited to participate in interviews at two-year intervals. Detailed information on participation is provided in [23] Bucholz et al., 2017. Information on all available interviews for each subject was combined in the present analysis with age of onset assigned according to the earliest description of psychopathology and a judgment of severity based on the time when the most symptoms were described. Every subject with at least one complete interview was included in the analysis.

DSM-IV [29] diagnoses for all disorders were made algorithmically from SSAGA information. However for these analyses we also generated a DSM-5 [30] diagnosis for AUD in the following way. Individual alcohol symptoms were queried, starting with symptoms of DSM-IV alcohol dependence and alcohol abuse, adding craving and subtracting legal problems related to alcohol. Onset and offset of each symptom was recorded, making it possible to cluster symptoms that occurred by age. Thus the analyses presented here use DSM-5 AUD as an outcome variable while all other disorders are diagnosed by DSM-IV.

Diagnoses of externalizing and internalizing disorders at the baseline interview were also made algorithmically from the SSAGA using DSM-IV. Externalizing disorders included any of the following: ADHD, conduct disorder/antisocial personality disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, drug use disorder (including marijuana but not alcohol or tobacco). Internalizing disorders included major depression, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, and agoraphobia. Age of onset was determined for all comorbid disorders based on the SSAGA-IV.

Subjects were divided into groups based on whether they had an externalizing disorder or an internalizing disorder at the time of the baseline interview. The groups were: Externalizing, Internalizing, Both, or Neither. Alcohol use disorder diagnosis was then assessed at each interview period, using the DSM 5 distinctions for Mild AUD (2–3 symptoms), Moderate AUD (4–5 symptoms), and Severe AUD (6 or more symptoms. The age of onset was defined as the first age when the required number of symptoms occurred during the same year. If two interviews performed on the same subject at different times provided divergent estimates of age of onset, the earliest age was taken as correct. Subjects were stratified into mutually exclusive categories based on the most severe AUD diagnosis they received during any part of the follow-up period (i.e., subjects with severe AUD were not counted in the Mild or Moderate AUD categories, though they may have aged through a time when they would have qualified for one or both of those diagnoses). Subjects with age of onset of AUD prior to age of onset of internalizing/externalizing disorders were excluded from analysis.

We also performed a sensitivity analysis (for model dependence) in which all subjects with externalizing (with or without internalizing) were compared with all subjects without externalizing; likewise subjects with internalizing (with or without externalizing) were compared with all subjects without internalizing (see Supplementary materials). An externalizing-internalizing interaction term was included in this analysis.

Statistical Methods

A Cox proportional hazards model was used to test the relationship of baseline externalizing or internalizing diagnoses to later onset of an AUD. All Cox model analyses were adjusted for sex, ethnicity, family membership, and case/comparison status. Survival curves were estimated by Kaplan-Meier plots. Ages of onset for alcohol milestones were compared using ANOVA and t-test.

RESULTS

Overall, 43.0% of the sample met criteria for a diagnosis of either Mild, Moderate, or Severe AUD by the end of the observation period (1416/3286; Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (N = 3286).

| Subject Variable | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age at first interview | 16.13 (3.29) |

| Age at last interview | 23.13 (4.97) |

| Number of interviews | 4.02 (1.73) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 1673 (50.91%) |

| Male | 1613 (49.09%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| EA | 2133 (64.91%) |

| AA | 1016 (30.92%) |

| Other | 155 (4.21%) |

| Family type | |

| Case | 2848 (86.67%) |

| Control | 438 (13.33%) |

| Any type of AUD | |

| Yes | 1416 (43.09%) |

| No | 1870 (56.91%) |

| Comorbidity | |

| Externalizing only | 982 (29.88%) |

| Internalizing only | 140 (4.26%) |

| Both | 286 (8.70%) |

| Neither | 1878 (57.15%) |

At the time of the baseline interview, 982/3286 subjects had an externalizing diagnosis (29.9%); 140/3286 subjects had an internalizing diagnosis (4.3%), 286 had both (8.7%) and 1878 had neither (57.2%) (Table 1). All covariates (sex, ethnicity, family type) had significant relationships to age of onset in subjects with either mild, moderate, or severe AUD (Table 2). The association of any comorbid disorder and presence of Alcohol Use Disorder was significant overall (chi-square p-value < 0.0001), and there was a significant effect of comorbidity on age of onset as well (p < 0.001 for each type of AUD, Figure 1a–c). Among subjects with an externalizing disorder only at baseline, 515/982 (52.4%) had some type of AUD during the follow-up period. Among subjects with an internalizing disorder only at baseline 66/140 (47.1%) had an AUD. Among subjects with both externalizing and internalizing, 182/286(63.6%) had an AUD. In comparison, subjects with neither type of disorder had an AUD rate of 34.7% (653/1878).

Table 2.

Hazard ratio and 95% CI-Cox model.

| Comorbidity | Outcome | Description | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidity at baseline | Onset age of mild AUD | Gender: Female vs Male | 0.71 (0.61, 0.83) |

| Ethnicity: African American vs European American | 0.65 (0.55, 0.77) | ||

| Ethnicity: African American vs Other | 1.11 (0.68, 1.79) | ||

| Ethnicity: European American vs Other | 1.69 (1.06, 2.71) | ||

| Family type: Control vs Case | 0.74 (0.59, 0.93) | ||

| Comorbidity at baseline: Both vs External | 0.89 (0.65, 1.21) | ||

| Comorbidity at baseline: Both vs Internal | 1.35 (0.86, 2.10) | ||

| Comorbidity at baseline: Both vs Neither | 1.39 (1.04, 1.87) | ||

| Comorbidity at baseline: External vs Internal | 1.51 (1.04, 2.20) | ||

| Comorbidity at baseline: External vs Neither | 1.57 (1.33, 1.85) | ||

| Comorbidity at baseline: Internal vs Neither | 1.04 (0.72, 1.49) | ||

| Onset age of moderate AUD | Gender: Female vs Male | 0.61 (0.50, 0.75) | |

| Ethnicity: African American vs European American | 0.45 (0.35, 0.57) | ||

| Ethnicity: African American vs Other | 0.43 (0.27, 0.70) | ||

| Ethnicity: European American vs Other | 0.97 (0.62, 1.51) | ||

| Family type: Control vs Case | 0.38 (0.25, 0.56) | ||

| Comorbidity at baseline: Both vs External | 1.32 (0.97, 1.79) | ||

| Comorbidity at baseline: Both vs Internal | 1.84 (1.15, 2.95) | ||

| Comorbidity at baseline: Both vs Neither | 2.80 (2.07, 3.77) | ||

| Comorbidity at baseline: External vs Internal | 1.39 (0.91, 2.14) | ||

| Comorbidity at baseline: External vs Neither | 2.12 (1.70, 2.64) | ||

| Comorbidity at baseline: Internal vs Neither | 1.52 (1.00, 2.31) | ||

| Comorbidity at baseline | Onset age of severe AUD | Gender: Female vs Male | 0.70 (0.56, 0.88) |

| Ethnicity: African American vs European American | 0.37 (0.28, 0.49) | ||

| Ethnicity: African American vs Other | 0.23 (0.14, 0.36) | ||

| Ethnicity: European American vs Other | 0.62 (0.41, 0.94) | ||

| Family type: Control vs Case | 0.32 (0.19, 0.52) | ||

| Comorbidity at baseline: Both vs External | 1.88 (1.41, 2.51) | ||

| Comorbidity at baseline: Both vs Internal | 6.01 (3.00, 12.04) | ||

| Comorbidity at baseline: Both vs Neither | 6.08 (4.51, 8.21) | ||

| Comorbidity at baseline: External vs Internal | 3.20 (1.62, 6.32) | ||

| Comorbidity at baseline: External vs Neither | 3.24 (2.49, 4.21) | ||

| Comorbidity at baseline: Internal vs Neither | 1.01 (0.51, 2.00) |

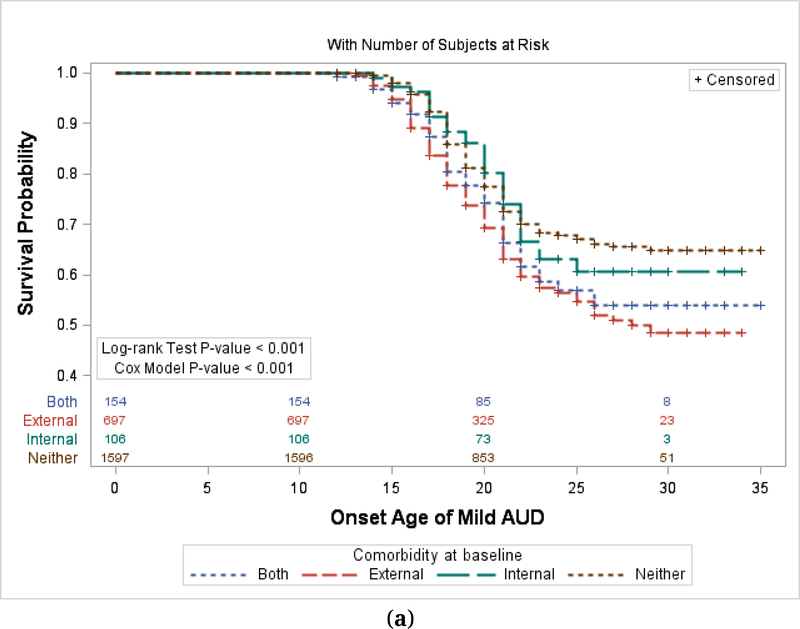

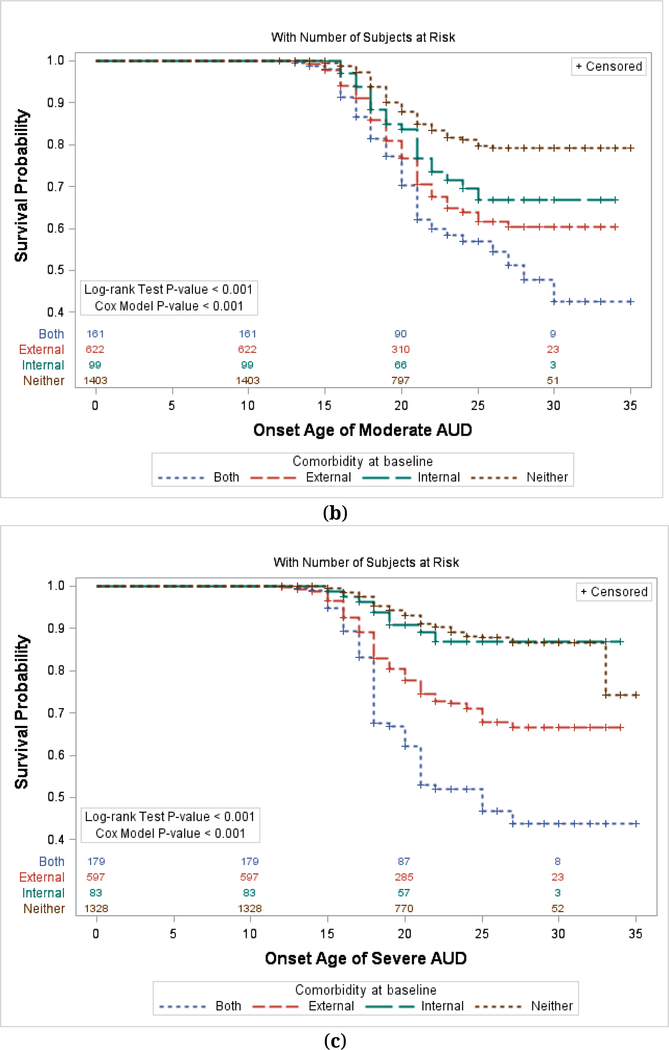

Figure 1.

(a) Kaplan-Meier Plot by Prior Comorbidity—Mild AUD. (b) Kaplan-Meier Plot by Prior Comorbidity—Moderate AUD. (c) Kaplan-Meier Plot by Prior Comorbidity—Severe AUD. Numbers in the Figure represent the N of subjects at risk at various ages.

Figure 1 shows onset of alcohol use disorders (AUDs) in subjects stratified by initial diagnoses of Externalizing disorder, Internalizing disorder, Both, or Neither. Figures 1a–c show onset of mild, moderate, and severe AUDs respectively. For each type of AUD, the relationship with comorbid disorders is significant by Log-rank test (p < 0.001) and Cox Proportional Hazards (p < 0.001).

Age of onset comparisons are shown in Kaplan-Meier Plots (Figure 1a–c). Each of these shows significant effects of comorbidity by Log-rank Test (p < 0.001 for each). The plots do not include a covariate effect but we have also achieved similar results by the Cox model adjusting for covariate effects (p < 0.001 for each; Table 2). The statistical effect of comorbidity is generally greatest in the development of Severe AUD and least in Mild AUD based on the hazard ratios in the different comorbidity types (Table 2). The three groups are significantly different from each other in the strength of the comorbidity effect (Severe vs Moderate, p < 0.001; Severe vs Mild, p < 0.001; Moderate vs Mild, p < 0.001).

The sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Table S1) showed a clear effect of externalizing on age of onset in mild AUD, moderate AUD, and severe AUD (p < 0.001 for each). For internalizing, there was an effect in moderate AUD (p < 0.011) and severe AUD (p < 0.001). No statistical interaction was seen between the effect of externalizing and the effect of internalizing.

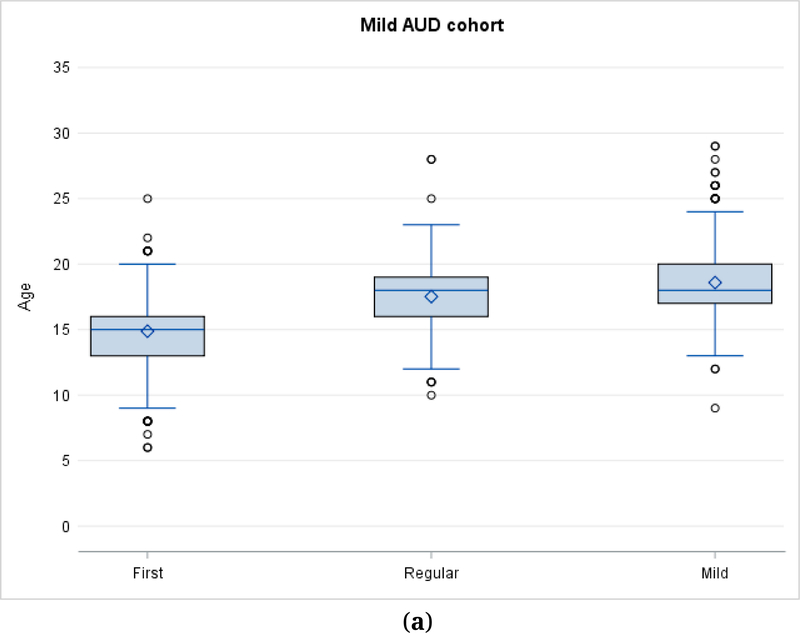

Age of onset distributions are presented for Mild AUD (Figure 2a), Moderate AUD (Figure 2b), and Severe AUD (Figure 2c). The distributions include drinking milestones (first drink, first regular drinking) as well as onset ages for the diagnoses of Mild AUD (Figure 2a–c), Moderate AUD (Figure 2b,c) and Severe AUD (Figure 2c only). As noted above, the study samples are independent of each other for analytic purposes, and are classified according to the most severe disorder that the subject met criteria for during the observation period.

Figure 2.

(a)Age of onset for drinking milestones in Mild AUD. (b) Age of onset for drinking milestones in Moderate AUD. (c) Age of onset of drinking milestones in Severe AUD.

Figure 2 shows drinking milestones in subjects who developed an alcohol use disorder.

Figure 2a–c show mean, median, interquartile range, and outliers for subjects with mild (N = 684), moderate (N = 415) and severe (N = 317) alcohol use disorder. Subjects are classified in a cohort according to the most severe form of disorder they manifested during the observation period. In Figure 2b milestones for the moderate group include the age when they would have been first classified as showing a mild AUD. In Figure 2c milestones for the severe group include the ages when they would have been first classified as showing a mild or moderate AUD.

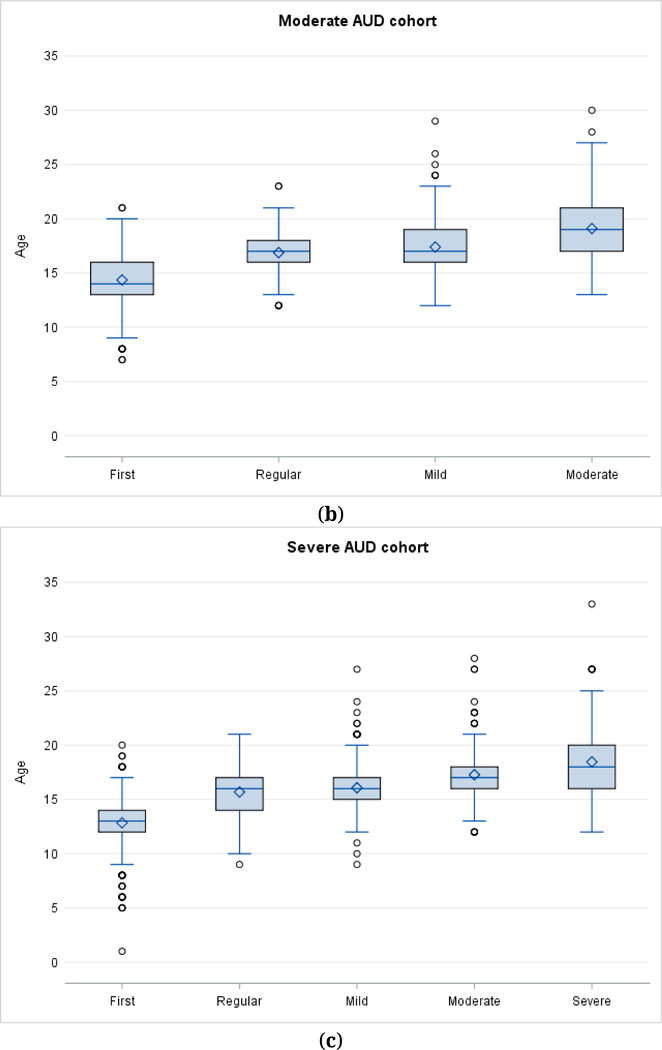

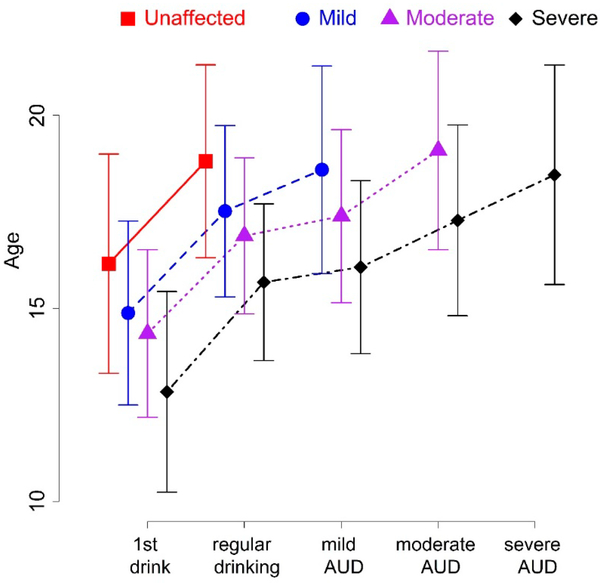

We used ANOVA and i-test to detect the correlation between the onset of drinking milestones in the four diagnostic groups. The mean age of first drink progresses from 16.2 in Unaffected to 14.9 in Mild to 14.4 in Moderate to 12.8 in Severe (p < 0.001). The mean age of first regular drinking progresses from 18.8 in Unaffected to 17.5 in Mild to 16.9 in Moderate to 15.7 in Severe (p < 0.001). The mean age for meeting criteria for Mild AUD progresses from 18.6 in Mild to 17.4 in Moderate to 16.1 in Severe (p < 0.001). The mean age for meeting criteria for Moderate AUD progresses from 19.1 in Moderate to 17.3 in Severe (p < 0.001). The age of onset for Severe AUD is 18.5. This age relationship is detailed in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Comparison of drinking milestones in four groups divided by severity of alcohol problems.

Figure 3 represents the onset of alcohol use and alcohol problems in 3286 adolescents observed over a ten year period. It includes 1870 who remained unaffected, 684 who developed mild alcohol use disorder, 415 who developed moderate alcohol use disorder, and 317 who developed severe alcohol use disorder.

The ANOVA for onset of first drink among the unaffected, mild, moderate, and severe cohorts shows p < 0.001. The ANOVA for onset of regular drinking among the unaffected, mild, moderate, and severe cohorts shows p < 0.001. The ANOVA for onset age of mild AUD among the mild, moderate, and severe cohorts shows p < 0.001. The t-test for onset age of moderate AUD between the moderate and severe cohorts shows p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

These data suggest a strong effect of externalizing and internalizing disorders on prevalence and age of onset of Alcohol Use Disorder among adolescents/young adults at risk for the development of AUD on the basis of family history. Externalizing disorders were clearly associated with an increased risk for AUD and for earlier development of AUD. Internalizing disorders by themselves did not show a significant effect, but in combination with externalizing disorders they were associated with an earlier onset for severe AUD (in comparison to externalizing disorders alone). When we considered all internalizing disorders together (with or without externalizing disorders) a clear effect on onset of moderate AUD was seen as well. By the end of the follow-up period, more than 60% of young people with both externalizing and internalizing disorders at baseline had developed alcohol dependence in comparison with about 30% of young people with neither type of comorbid disorder. The effect of comorbidity was stronger in more severe forms of AUD, with a 6-fold increase in risk for Severe AUD among subjects with both externalizing and internalizing disorders compared to subjects with neither form of comorbid disorder.

There was also evidence for an earlier developmental course in more severe forms of AUD compared to less severe. Persons with Severe AUD were likely to have their first full drink prior to the age of 13 and be drinking regularly prior to age 16 and experiencing 1–2 alcohol problems by that same age. In contrast young people who did not demonstrate any AUD were likely to have their first drink at 16 and start regular drinking just prior to age 19. Median and mean ages of onset for each type of AUD were 18–19, though the range extended through the follow-up period.

Those at greatest risk for an AUD were males of European descent from an alcohol-dependent proband family with one or more childhood onset psychiatric diagnoses. Those at least risk were females of African-American ancestry from a non-case family with no childhood onset diagnosis.

Limitations of the study include the fact that all analyses are based on self-report and there is no independent corroboration of diagnoses or symptoms. Subjects interviewed in their late 20s may have had more difficulty with accurate reporting of events in early teenage years in comparison to subjects in their mid-teens. Retention rate from baseline interview to two-year interview was 85%, the majority of subjects completed at least four interviews ([23] Bucholz et al., 2017). Families in the COGA study tend to be densely affected and results may not be generalizable to persons with alcohol use disorder in the general population. The subjects were ascertained at 7 University-based clinical sites (State University of New York, Brooklyn, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Washington University in St. Louis, University of California San Diego, University of Connecticut, Hartford, and Howard University, Washington DC) and the populations studied reflect those sites.

The magnitude of these effects was substantial, and this information may be helpful in targeting efforts at education and prevention. In this sample most of the AUD-affected subjects had a comorbid psychiatric disorder at baseline. Many such subjects may come to clinical attention for their childhood-onset disorders and it may be worth educational efforts targeting AUD, especially for those at increased familial risk. It has been argued, though, that more intensive interventions are not likely to be cost- effective at this time ([13] Glantz et al., 2009). It seems to be of value to continue to try to quantify risk in various clinically and biologically identifiable groups. Polygenic risk scores, especially as they increase in power with data from expanding clinical samples, will likely be of use ([31] Fullerton and Nurnberger, 2019). It would also be of value to attempt to separate AUD effects from other forms of SUD, since we know that they are highly comorbid in many samples, including the sample studied here.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We continue to be inspired by our memories of Henri Begleiter and Theodore Reich, founding PI and Co-PI of COGA, and also owe a debt of gratitude to other past organizers of COGA, including Ting-Kai Li, P. Michael Conneally, Raymond Crowe, and Wendy Reich, for their critical contributions.

FUNDING

This national collaborative study is supported by NIH Grant U10AA008401 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

The supplementary materials are available online at https://doi.org/10.20900/jpbs.20190016.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. Nurnberger is an investigator for Janssen on a separate study. Other investigators declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Deutsch AR, Slutske WS, Richmond-Rakerd LS, Chernyavskiy P, Heath AC, Martin NG. Causal influence of age at first drink on alcohol involvement in adulthood and its moderation by familial context. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74(5):703–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rurnberger JI Jr, Wiegand R, Bucholz K, O’Connor S, Meyer ET, Reich T, et al. A family study of alcohol dependence: coaggregation of multiple disorders in relatives of alcohol-dependent probands. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2004;61:1246–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007:64(7):830–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delker E, Brown Q, Hasin DS. Alcohol Consumption in Demographic Subpopulations: An Epidemiologic Overview. Alcohol Res. 2016:38(1):7–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasilenko SA, Evans-Polce RJ, Lanza ST. Age trends in rates of substance use disorders across ages 18–90: Differences by gender and race/ethnicity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;180:260–4. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.08.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(1):8–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith SM, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Goldstein R, Huang B, Grant BF. Race/ethnic differences in the prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2006;36(7):987–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang B, Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Race- ethnicity and the prevalence and co-occurrence of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, alcohol and drug use disorders and Axis I and II disorders: United States, 2001 to 2002. Compr Psychiatry. 2006;47(4):252–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757–66. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant JD, Vergés A, Jackson KM, Trull TJ, Sher KJ, Bucholz KK. Age and ethnic differences in the onset, persistence and recurrence of alcohol use disorder. Addiction. 2012;107(4):756–65. doi: 10.1111/i.1360-0443.2011.03721.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lui CK, Mulia N. A Life Course Approach to Understanding Racial/Ethnic Differences in Transitions Into and Out of Alcohol Problems. Alcohol Alcohol. 2018;53(4):487–96. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agy015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Kerridge BT, Ruan WJ, et al. Prevalence of 12-Month Alcohol Use, High-Risk Drinking, and DSM-IV Alcohol Use Disorder in the United States, 2001–2002 to 2012–2013: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(9):911–23. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glantz MD, Anthony JC, Berglund PA, Degenhardt L, Dierker L, Kalaydjian A, et al. Mental disorders as risk factors for later substance dependence: estimates of optimal prevention and treatment benefits. Psychol Med. 2009;39(8):1365–77. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plana-Ripoll O, Pedersen CB, Holtz Y, Benros ME, Dalsgaard S, de Jonge P, et al. Exploring Comorbidity Within Mental Disorders Among a Danish National Population. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Lakoma MD, Petukhova M, et al. Lifetime co-morbidity of DSM-IV disorders in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Psychol Med. 2012;42(9):1997–2010. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boschloo L, Vogelzangs N, van den Brink W, Smit JH, Veltman DJ, Beekman AT, et al. Depressive and anxiety disorders predicting first incidence of alcohol use disorders: results of the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(12):1233–40. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kandel DB, Johnson JG, Bird HR, Weissman MM, Goodman SH, Lahey BB, et al. , Schwab-Stone ME.Psychiatric comorbidity among adolescents with substance use disorders: findings from the MECA Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(6):693–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crum RM, Green KM, Stuart EA, La Flair LN, Kealhofer M, Young AS, et al. Transitions through stages of alcohol involvement: The potential role of mood disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;189:116–24. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.02.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acion L, Kramer J, Liu X, Chan G, Langbehn D, Bucholz K, et al. Reliability and Validity of an Internalizing Symptom Scale Based on the Adolescent and Adult Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA). Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45(2):151–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cloninger CR. Neurogenetic adaptive mechanisms in alcoholism. Science. 1987;236(4800):410–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Babor TF, Hofmann M, DelBoca FK, Hesselbrock V, Meyer RE, Dolinsky ZS, Rounsaville B. Types of alcoholics, I. Evidence for an empirically derived typology based on indicators of vulnerability and severity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992; 49(8):599–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuperman S, Schlosser SS, Kramer JR, Bucholz K, Hesselbrock V, Reich T, et al. Developmental sequence from disruptive behavior diagnosis to adolescent alcohol dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:2022–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bucholz KK, McCutcheon VV, Agrawal A, Dick DM, Hesselbrock VM, Kramer JR, et al. Comparison of Parent, Peer, Psychiatric, and Cannabis Use Influences Across Stages of Offspring Alcohol Involvement: Evidence from the COGA Prospective Study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017;41(2):359–68. doi: 10.1111/acer.13293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Groenman AP, Janssen TWP, Oosterlaan J. Childhood Psychiatric Disorders as Risk Factor for Subsequent Substance Abuse: A Meta-Analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(7):556–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, D.C: (US): American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feighner JP, Robins E, Guze SB, Woodruff RA Jr, Winokur G, Munoz R. Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1972;26(1):57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reich T, Edenberg HJ, Goate A, Williams JT, Rice JP, Van Eerdewegh P, et al. Genome-wide search for genes affecting the risk for alcohol dependence. Am J Med Genet. 1998;81(3):207–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI Jr, et al. A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: a report on the reliability of the SSAGA. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;55(2):149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, D.C: (US): American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, D.C: (US): American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fullerton JM, Nurnberger JI. Polygenic risk scores: Will they be useful for clinicians? F1000 Res. 2019;8. doi: 10.12688/F1000research.18491.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.