Highlights

-

•

Dunaliella salina opposed the fibrotic effect of thioacetamide in rat liver.

-

•

D. salina significantly reduced serum levels of ALT, AST, ALP and total bilirubin.

-

•

D. salina revealed an elevation in GSH and a reduction in MDA in sera.

-

•

D. salina caused fall in hepatic contents of α-SMA and collagen I to normal level.

-

•

Scoring of fibrosis indicated that D. salina is an efficient hepatoprotective agent.

Keywords: Dunaliella salina, Thioacetamide, Fibrosis, α-SMA, Collagen I, Rat

Abstract

Several hepatic pathological conditions are correlated with the stimulation of hepatic stellate cells. This induces a cascade of events producing accretion of extracellular matrix components triggering fibrosis. Dunaliella salina, rich in carotenoids, was investigated for its potential antagonizing activity; functionally and structurally against thioacetamide (TAA) - induced hepatic fibrosis in rats. Adult male albino Wistar rats were treated with three dose levels of D. salina powder or extract (daily, p.o.); for 6 weeks, concomitantly with TAA injection. Serum levels of aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), bilirubin and albumin were determined. Reduced glutathione (GSH), malondialdehyde (MDA), smooth muscle actin alpha (α-SMA) and collagen I hepatic contents were also estimated. Treatment with D. salina powder or extract caused a significant decline in serum levels of AST, ALT, ALP, bilirubin, MDA and hepatic contents of α-SMA and collagen I. Additionally, serum albumin and GSH hepatic content were highly elevated. Liver histopathological examination also indicated that D. salina reduced fibrosis, centrilobular necrosis, and inflammatory cell infiltration evoked by TAA. The results implied that D. salina exerts protective action against TAA-induced hepatic fibrosis in rats. The phytochemical investigation revealed high total carotenoid content prominently β-carotene (15.2 % of the algal extract) as well as unsaturated fatty acids as alpha-linolenic acid which accounts for the hepatoprotective activity.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, microalgae have gained great interest due to their several health benefits. They present a prosperous source of different pharmacologically effective molecules including carotenoids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, phenolic compounds, and polysaccharides [1] that satisfy the increased demand for novel pharmaceutical and nutraceutical ingredients. Various studies have proven the antioxidant, cytotoxic [2,3] and anti-inflammatory activities of different microalgal extracts [4].

Dunaliella salina (D. salina) is unicellular marine phytoplankton that belongs to the phylum Chlorophyta family Dunaliellaceae [5], Dunaliella was first described in a hundred years and was considered a key element for most of the primary biota in hypersaline environments worldwide. Dunaliella represents a convenient organism for algae study of salt adaptation. The accumulation of carotenoids, especially β-carotene by D. salina under suitable growth conditions has led to its potent antioxidant and effect. Moreover, previous work revealed the antidiabetic activity of D. salina in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats [6], the neuromodulating effect against the development of Alzheimer’s disease [7] as well as the protective activity against myocardial infarction [8].

Silymarin, an extract of milk thistle (Silybum marianum), is one of the famous herbal agents used for its hepatoprotective effect and possesses antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects [9].

Thioacetamide (TAA) model is reliable for induction of hepatic fibrosis model. Its long exposure exhibited histological and biochemical damage similar to liver fibrosis in human via stimulation of extensive oxidative stress [10] that is indicator of xenobiotics hazards [11] and moreover inducing advanced hepatocellular carcinoma [12]. Hepatoprotective activities of drugs are related to antioxidant properties that upregulate the endogenous antioxidant defense system [13].

Hepatic fibrosis; a wound healing process, is amongst the most prevailing liver ailments affecting the world population. It is generally related to unhealthy lifestyles, alcoholic abuse, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, and chronic hepatitis viral infections. Eventually, hepatic fibrosis leads to more severe stages as cirrhosis and ultimately hepatocellular carcinoma [14]. One of the focal causes of liver incompetence is oxidative stress which hinders the liver function in detoxification processes resulting in further accumulation of oxidant factors [15] and is the primary mechanism of liver damage and fibrosis which is a pathological response to hepatocyte [16].When the liver is attacked by ROS, Parenchyma cells are exposed to oxidative stress and produce ROS. Moreover, Kupffer cells, Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) and endothelial cells are sensitive to oxidative stress. The proliferation and collagen synthesis of HSCs are induced by lipid peroxidation, malondialdehyde (MDA) [17].

Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) are collagen-producing cells, which once activated display myofibroblast phenotype which is considered a pivotal incident in many chronic liver diseases progression. A cascade of molecular, cellular, and tissue events is produced bringing about the accretion of extracellular matrix (ECM) components, especially collagen, and the liver parenchyma is altered into scar tissues, progressing into fibrosis [18]. Activated HSCs play an essential role in the secretion of alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), the expression of collagen type I and III, and the assembly of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [19].

The present work is intended to assess the potential role of carotenoid-rich D. salina microalga powder and extract in opposing TAA-induced hepatic fibrosis in rats.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

Thioacetamide reagent, ≥99.0 % was bought from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. Silymarin was procured from MEPACO- Egypt; high analytical grade chemicals were used during the experimental procedures. Kits used for measurement of serum aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), total bilirubin levels, albumin, reduced glutathione (GSH) and malondialdehyde (MDA), were procuredfrom Biodiagnostic, Egypt. Alpha-smooth muscle actin (α -SMA) and collagen I were procured from SinoGeneClone Biotech Co., Ltd.

2.2. Preparation of D. salina extract

The dried powder of Dunaliella salina biomass was subjected to extensive grinding to assure disruption of the cell wall. The algal biomass was macerated in a solvent mixture of hexane, ethyl acetate (80:20), filtered and the solvent was then removed under reduced pressure in a rotary evaporator apparatus at a temperature not exceeding 40 °C till complete dryness. This step was repeated till complete exhaustion of the algal powder [20]. The dried extract was kept in a opaque bottle at a 4 °C for further analysis.

2.3. Determination of total carotenoid content

The total carotenoid content was estimated spectrophotometrically (Shimadzu UV 240 (PIN 204–5800), at 450 nm [21]. To determine the total carotenoid content, the algal extract was suspended in distilled water and conveyed to a 500 mL separating flask containing 40 mL petroleum ether (40−60 °C). The aqueous layer was discarded andthe procedure was repeated four times. Then, the collected petroleum ether extract was filtered over anhydrous sodium sulfate and transferred to a 50 mL volumetric flask andthe volume was adjusted up to 50 mL using petroleum ether.The absorbance of the extract wasmeasured at 450 nm andthe total carotenoid content was calculated according to the following equation:

where A = Absorbance of the extract; V = Total volume of the extract; P = initial sample weight and = 2592 (β-carotene Extinction Coefficient in petroleum ether).

3. HPLC estimation of β-carotene in algal extract

3.1. Sample preparation

D. salina extract was sonicated with 5 mL methanol/acetonein a ratio of 1:1 v/v till dissolution,then filtered through a membrane filter(0.45 μm) and stored in the dark for HPLC analysis.

3.2. Preparation of standard curve

Solutions of β-carotene in the range of 0.02-0.1 mg of standard β-carotene (purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) were prepared. The calibration curvewas drawn by plotting the concentrations of standard against the peakarea. The correlation coefficient (r2) and the regression equation were calculated [8].

3.3. HPLC analysis

The analysis was performed using an analytical HPLC system equipped witha Zorbax-C18 column (5 μm; 250 mm × 4.6 mm) on an Agilent 1200 series instrument. Amobile phase consisting of methanol, water, dichloromethane and acetonitrile in the ratio of 70:4:13:13, v/v/v/v in an isocratic mode was used. All the solvents used were HPLC grade, filtered through 0.45 μm membrane and degassed before use. The flow rate was adjusted at 1.0 mL/min and the analysis was done at room temperature. Detection was recorded at wavelength 280, 450 and 480 nm using a photodiode-array detection system.

3.4. Identification and quantification of β-carotene

β-carotene was identified in algal extract by comparing the retention time with that of the reference standard in addition to spiking the algal extract with β-carotene standard solution. The amount of β-carotene was calculated from the calibration curve as mg%.

3.5. Determination of fatty acids

The algal powder was mixed with petroleum ether and placed in an ultrasonic extractor till complete extraction of the lipoidal matter then filtered to eliminate algal debris. After extraction of lipoidal matter, it was dissolved in 5% methanolic hydrochloric acid for methylation of fatty acids, heated under reflux for 2 h. After cooling,fatty acid methyl esters were extracted in diethyl ether. The ether phase was separated, evaporated and transferred to GC analysis.

3.6. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS)

The analysis wasdoneon a Thermo Scientific, Trace GC Ultra/IQS Single Quadruple MS apparatus, equipped with TG- 5MS fused silica capillary column 30 mm of length, 0.251 mm width, and 0.1 mm film thickness. Helium;the carrier gas,was set at a constant flow rate of 1 mL/minand an electron ionization system with ionization energy of 70 eV was used. The temperature was adjusted at 280 °C. The oven temperature was setinitially at 150 °C increasing at a rate of 5 °C/min till reaching 280 °C. The identification of the separated fatty acids as methyl esters was done according to their retention times and mass spectra as compared with the data supported by the libraries of the apparatus and that found in the literature.

3.7. Animals

Adult male albino Wister rats of 120–150 g average weight were supplied from the animal house at the National Research Centre (Giza, Egypt) and kept in a well aerated,12-h light/dark cycled room at 25 °C.The animals were let free to a standard laboratory diet ad libitum. All experimental procedures on animals were held in accordance with the guidelines for care and use of experimental animals permitted by the Ethical Committee of the National Research Centre. In addition, this study was approved by the Egypt Academy of Scientific Research and Technology with project identification code number: KTA-C2-2.10.

3.8. Acute toxicity studies

Male albino Wister rats were kept fasting providing only water, after which they were orally administered gradual doses (1−5 g/kg) of the algal powder and extract through a gastric tube. The rats were kept under observation for 72 h for any toxic symptoms or mortality.

3.9. Fibrosis experimental design

After an acclimatization period of one week, male albino Wister rats have haphazardly arranged into 9 groups 8 rats per group as follows:

Group 1: received water containing 1 % Tween 80 orally for 6 weeks and served as normal control.

Group 2: received TAA (200 mg/kg, suspended in1 % Tween 80; i.p.) twice per week for 6 weeks and served as TAA control [22].

Group 3: received silymarin (50 mg/kg, orally) daily for 6 weeks concurrent with TAA [23].

Group 4-6: received D. salina powder (12.5, 25& 50 mg/kg, orally) daily for 6 weeks concurrent with TAA.

Group 7-9: received D. salina extract (12.5, 25& 50 mg/kg, orally) daily for 6 weeks concurrent with TAA.

After the completion of the experiment; the animals were subjected to light anesthesia using ketamine (80 mg/kg) and blood was collected from the retro-orbital veins. Blood samples were permitted to coagulate and subsequently subjected to centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 15 min to separate the sera. Serum levels of AST and ALT activities [24]; ALP [25]; total bilirubin [26] and albumin [27] were estimated. Additionally, levels of GSH and MDA were recorded in serum in accordance with Beutler et al. and Ohkawa et al. [28,29]. Under anesthesia, the animals’ livers were excised, washed with saline solution, located in ice-cold phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and subjected to homogenization. The 20 % tissue homogenate was further used for the estimation of hepatic contents of α -SMA and collagen I using Eliza kits.

3.10. Histological examination

Liver sections were set in 10 % formalin solution and exposed to increasing percentages of alcohol for dehydration then immersed in paraffin. Four sections/group, at the 4 μm thickness, were taken and stained using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson Trichrome.

3.11. Fibrosis scoring

Blinded METAVIR fibrosis score from 0 to 4 was used to evaluate the degree of liver fibrosis. Score 0 indicates no liver fibrosis. Score 1 designates minimum liver scarring in the region of the portal tract with no septa formed. Score 2 indicates a few numbers of septa formed around the portal tract. Score 3 designates multiple septa formation without reaching cirrhosis. Score 4 indicates extensive cirrhosis [30].

3.12. Statistical analysis

All the values are recorded as means ± standard error of the means (SE). Data were statistically analyzed by one-way analysis of variance then by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test using Graph Pad Prism software, version 5 (Inc., San Diego, USA). The difference was considered significant when p < 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Acute toxicity

The oral acute toxicity assay resulted in no lethality or manifestations of toxicity for D. salina powder/extract up to a dose level of 5 g/kg, hence it was considered safe. Therefore 12.5, 25 & 50 mg/kg/day (0.0025, 0.005 & 0.01 of 5 g) of the extract or powder were the doses selected for further study.

4.2. Effects of D. salina on serum hepatic functions biomarkers

Injection of TAA (200 mg/kg; i.p.) resulted in considerable hepatic fibrosis as figured out in the significant elevations in serum levels of AST, ALT, ALP and total bilirubin in reference to normal control group records. Treatment with silymarin lessened serum level of ALT only, in reference to the TAA group.

Treatment with D. salina powder (25 & 50 mg/kg) resulted in a significant reduction in serum levels of AST, ALT, ALP and total bilirubin as compared to TAA group. However, treatment with D. salina powder at a minimal dose (12.5 mg/kg) caused significant reduction only in serum levels of ALT and AST, as compared to the TAA group. Similarly, treatment with D. salina extract (25 & 50 mg/kg) resulted in a significant reduction all fore mentioned parameters whereas the lower dose level (12.5 mg/kg) caused reduction only in serum levels of ALT and bilirubin, as compared to TAA group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of D. salina powder and extract on serum hepatic functions biomarkers.

| Normal control | TAA | Silymarin (50 mg/kg) | D. salina powder (12.5 mg/kg) | D. salina powder (25 mg/kg) | D. salina powder (50 mg/kg) | D. salina extract (12.5 mg/kg) | D. salina extract (25 mg/kg) | D. salina extract (50 mg/kg) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT (U/L) | 43.82±0.37 | 68.52 ± 0.61a | 57.98 ± 0.17ab | 42.93 ± 0.33b | 40.17 ± 0.73b | 42.76 ± 0.45b | 38.81 ± 0.24b | 38.61 ± 0.27b | 38.81 ± 0.19b |

| ALT (% of TAA control) | (100 %) | 85 % | 63 % | 59 % | 62 % | 57 % | 56 % | 57 % | |

| AST (U/L) | 66.55 ± 0.08 | 103.3 ± 0.74a | 92.35 ± 0.41a | 88.18 ± 0.4ab | 88.03 ± 0.67ab | 87.51 ± 0.62ab | 95.18 ± 1.27a | 88.51 ± 0.54ab | 88.18 ± 0.81ab |

| AST (% of TAA control) | (100 %) | 89 % | 85 % | 85 % | 85 % | 92 % | 86 % | 85 % | |

| ALP (IU/L) | 57.85 ± 0.15 | 124.59 ± 0.48a | 115.38 ± 1.57a | 98.24 ± 0.59a | 69.56 ± 1.85b | 60.81 ± 0.77b | 93.82 ± 1.26a | 74.12 ± 1.79b | 67.21 ± 2.67b |

| ALP (% of TAA control) | (100 %) | 93 % | 79 % | 56 % | 49 % | 75 % | 59 % | 54 % | |

| Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 1.45 ± 0.01 | 2.62 ± 0.02a | 2.25 ± 0.01a | 2.15 ± 0.01a | 1.65 ± 0.04b | 1.53 ± 0.03b | 1.46 ± 0.01b | 1.30 ± 0.02b | 1.29 ± 0.00b |

| Bilirubin (% of TAA control) | (100 %) | 86 % | 82 % | 63 % | 59 % | 56 % | 50 % | 49 % | |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 4.19 ± 0.00 | 3.39 ± 0.03a | 3.43±0.02a | 3.54±0.02a | 3.86±0.02ab | 4.10±0.03b | 3.54±0.02a | 3.79±0.01ab | 3.81±0.03ab |

| (% of TAA control) | (100 %) | 101 % | 104 % | 114 % | 121 % | 104 % | 112 % | 112 % |

Injection of TAA resulted in a decrease of serum levels of albumin by 19 % as compared to normal control values. Treatment with D. salina powder and extract (25 & 50 mg/kg) elevated serum level of albumin by 14 %, 21 %, 12 % and 12 %, respectively as compared to TAA group (Table 1).

Liver fibrosis was induced by TAA (200 mg/kg, i.p.) twice per week for 6 weeks. Silymarin (50 mg/kg, orally), D. salina powder and D. salina extract (12.5, 25& 50 mg/kg, orally) were administered daily for 6 weeks concurrent with TAA. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. of (n = 8) for each group and % of TAA group. The statistical analysis was held using one-way analysis of variance then by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. a Statistically significant from the control group. b Statistically significant from TAA group at P < 0.05.

4.3. Effects of D. salina on serum oxidative stress biomarkers

A reduction in serum level of GSH and an elevation in the serum level of MDA were observed in the TAA group by 57 % and 83 % respectively as compared to normal control values. Treatment with silymarin increased serum level of GSH by 92 % and decreased serum level of MDA by 29 % as compared to the TAA group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of D.salina powder and extract on serum oxidative stress biomarkers.

| Normal control | TAA | Silymarin (50 mg/kg) | D. salina powder (12.5 mg/kg) | D. salina powder (25 mg/kg) | D. salina powder (50 mg/kg) | D. salina extract (12.5 mg/kg) | D. salina extract (25 mg/kg) | D. salina extract (50 mg/kg) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSH (mg/dl) | 15.60 ± 0.17 | 6.77 ± 0.06a | 13.00 ± 0.03b | 7.91 ± 0.03a | 12.93 ± 0.08b | 14.67 ± 0.19b | 9.60 ± 0.17ab | 13.07 ± 0.04b | 15.33 ± 0.09b |

| GSH (%of TAA) | 100 % | 192 % | 116 % | 191 % | 217 % | 142 % | 193 % | 226 % | |

| MDA (nmol/ml) | 10.14 ± 0.04 | 18.57 ± 0.15a | 13.24 ± 0.18ab | 18.21 ± 0.17a | 15.03 ± 0.03ab | 12.17 ± 0.11b | 17.59 ± 0.23a | 13.31 ± 0.08ab | 11.24 ± 0.15b |

| MDA (% of TAA) | 100 % | 71 % | 98 % | 81 % | 65 % | 95 % | 71 % | 61 % |

Treatment with D. salina powder (25 & 50 mg/kg) revealed an elevation in serum level of GSH by 91 % and 117 % respectively and produced a reduction in serum level of MDA by 19 % and 35 % respectively as compared to TAA group. Treatment with extract (12.5, 25 & 50 mg/kg) exhibited an elevation in serum level of GSH by 42 %, 93 % and 126 % respectively as compared to TAA group. Treatment with D. salina extract (25 & 50 mg/kg) reduced serum level of MDA by 29 % and 39 % respectively, as compared to the TAA group (Table 2).

Liver fibrosis was induced by TAA (200 mg/kg, i.p.) twice per week for 6 weeks. Silymarin (50 mg/kg, orally), D. salina powder and D. salina extract (12.5, 25& 50 mg/kg, orally) were administered daily for 6 weeks concurrent with TAA. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. of (n = 8) for each group and % of TAA group. The statistical analysis was held by using one-way analysis of variance then by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. a Statistically significant from the control group. b Statistically significant from TAA group at P < 0.05.

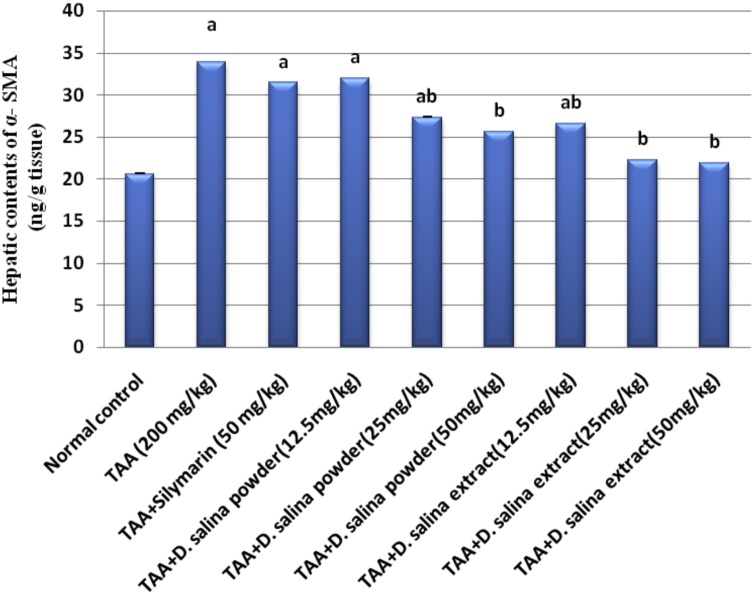

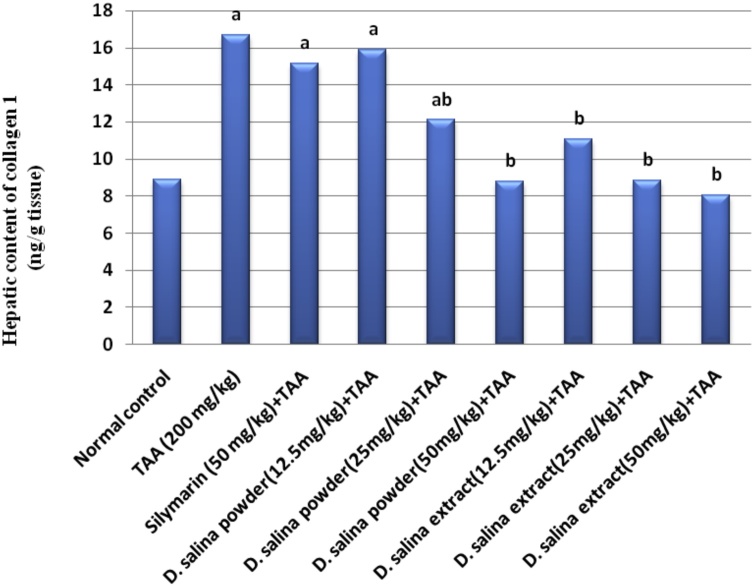

4.4. Effects of D. salina on fibrotic biomarkers

Injection of TAA showed considerable hepatic fibrosis as assessed by significant elevations in hepatic contents of α-SMA and collagen I by 64 % and 88 % respectively as compared to normal control values. Treatment with silymarin did not show any changesin hepatic contents of α-SMA and collagen I as compared to the TAA group.

Treatment with D. salina powder (25 mg/kg) resulted in a reduction in hepatic contents of α-SMA and collagen I by 19 % and 73 % respectively; treatment with powder (50 mg/kg) normalized hepatic contents of α-SMA and collagen I as compared to TAA group. Therefore the effective dose of D. salina powder is 50 mg. Treatment with D. salina extract (12.5 mg/kg) decreased hepatic content of α-SMA by 22 % while normalized collagen I. Treatment with extract (25 & 50 mg/kg) normalized hepatic contents of α-SMA and collagen I, as compared to TAA group. Therefore the effective doses of D. salina extract are 25 & 50 mg (Figs. 1 & 2).

Fig. 1.

Effects of D.salina powder and extract on hepatic content of α-SMA.

Fig. 2.

Effects of D.salina powder and extract on hepatic content of collagen I.

Liver fibrosis was induced by TAA (200 mg/kg, i.p.) twice per week for 6 weeks. Silymarin (50 mg/kg, orally), D. salina powder and D. salina extract (12.5, 25& 50 mg/kg, orally) were administered daily for 6 weeks concurrent with TAA. α-SMA was measured in liver tissue. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. of (n = 8) for each group. The statistical analysis was held by using one-way analysis of variance then by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. a Statistically significant from the control group. b Statistically significant from TAA group at P < 0.05.

Liver fibrosis was induced by TAA (200 mg/kg, i.p.) twice per week for 6 weeks. Silymarin (50 mg/kg, orally), D. salina powder and D. salina extract (12.5, 25& 50 mg/kg, orally) were administered daily for 6 weeks concurrent with TAA. Collagen I was measured in liver tissue. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. of (n = 8) for each group. The statistical analysis was held by using one-way analysis of variance then by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. a Statistically significant from the control group. b Statistically significant from TAA group at P < 0.05.

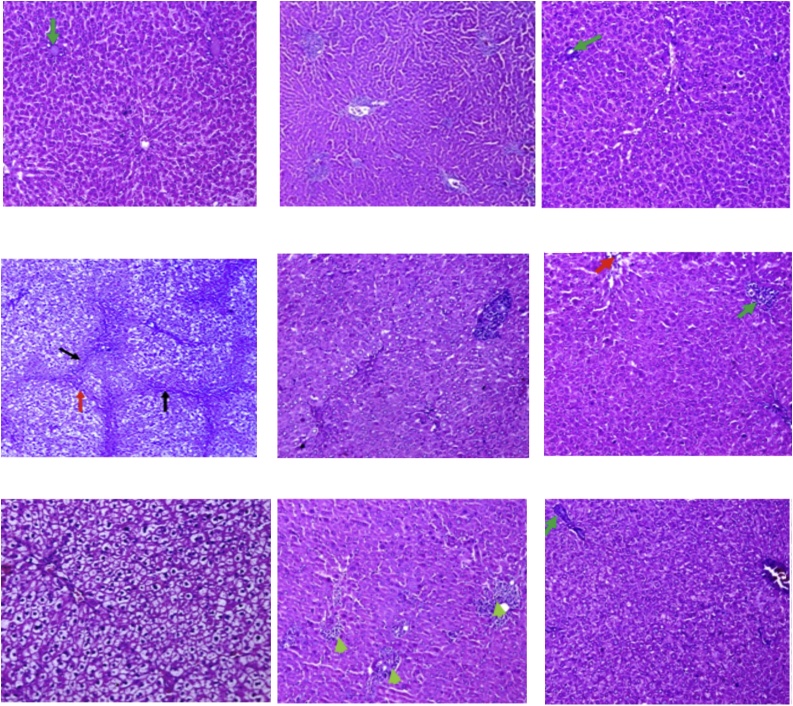

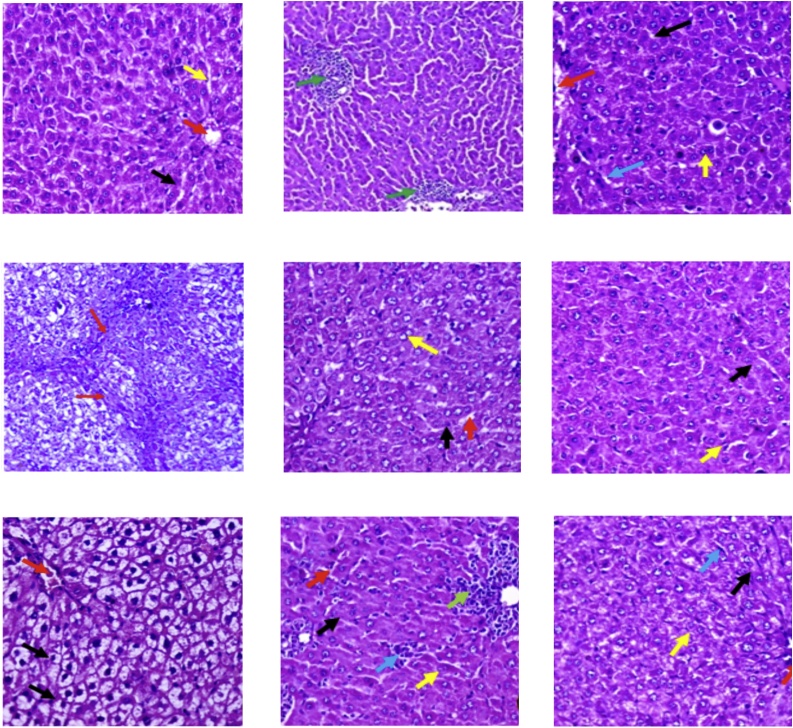

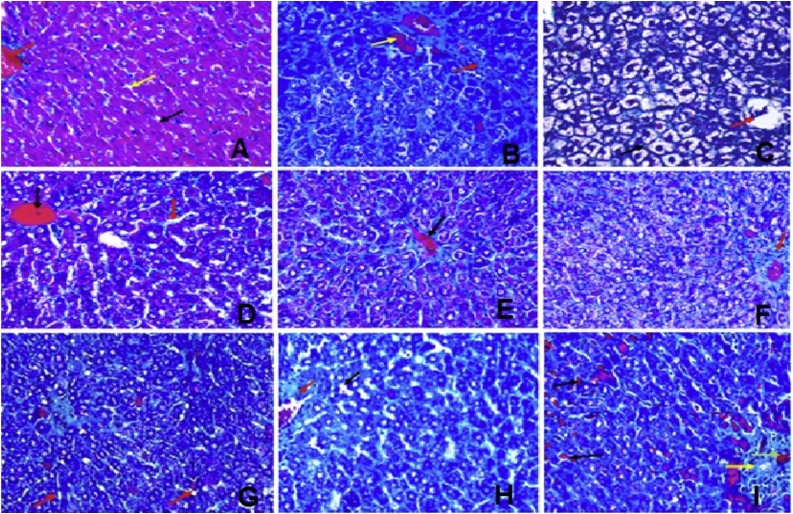

5. Histopathological study

Stained liver sections are illustrated at two magnifications (x100 and x200) in Figs. 3 & 4 . Liver sections from the normal control group(group 1) showed hepatic tissue with normal structure and architecture, hepatocytes arranged in thin plates (black arrow) and sinusoids (yellow arrow), central vein (red arrow), Portal tract (green arrow) (Fig. A). TAA treated group (group 2)liver sectionsshowed distorted lobular hepatic architecture (black arrow) with attempts to form micro and macro regenerating nodules as complete and incomplete thick interlobular fibrous septa between portal-portal and portal-central septa (red arrow), with moderate ballooning of hepatocyte with (yellow arrow), and binucleated nuclei (blue arrow), (Fig. B). Whereas liver sections from silymarin treated group showed hepatic tissue with almost normal structure and architecture, hepatocytes arranged in thin plates with ballooning (black arrow), central vein (red arrow), (Fig. C). Fig. D shows group 4 (low dose group; 12.5 mg/kg) and itshows preserved hepatic lobular architecture, with almost normal hepatocyte (black arrow) and binucleated hepatocytes (yellow arrow), sinusoids (red arrow), mildly thickened portal tract with lymphocytes (green arrow) (H&E; x200, x400), Fig. E shows group 5(medium dose group; 25 mg/kg)and itrevealed preserved hepatic lobular architecture, with almost normal hepatocyte (black arrow) and binucleated hepatocytes (yellow arrow), dilated sinusoids (red arrow), portal tract mildly extended with lymphocytes (green arrow), intercellular lymphocytes collection (blue arrow) (H&E, x200,x400) and Fig. F shows group 6 (high dose group; 50 mg/kg) and it showed preserved hepatic lobular architecture, with almost normal hepatocyte (black arrow) and binucleated hepatocytes (yellow arrow), dilated sinusoids (red arrow), portal tract mildly extended with lymphocytes (green arrow), bile duct (blue arrow), blood vessel (white arrow) (H&E; x200, x400). Fig. G showsliver sections from animals treated with algal extract low dose (12.5 mg/kg, group 7) revealing preserved hepatic lobular architecture, with almost normal hepatocyte (black arrow) and binucleated hepatocytes (yellow arrow), congested central vein (red arrow), sinusoids (blue arrow), portal tract (green arrow) (H&E; x200, x400),while Fig. H shows liver sections from animal group 8 receiving algal extract medium dose group (25 mg/kg) where preserved hepatic lobular architecture, with almost normal hepatocyte (black arrow) central vein(red arrow), sinusoids (yellow arrow) and lymphocytes in portal tract (green arrow) appeared (H&E; x200, x400). Finally, Fig. I shows liver sections from animal group 9 receiving algal extract high dose (50 mg/kg) showing preserved hepatic lobular architecture, with almost normal hepatocyte (black arrow) and binucleated hepatocytes (yellow arrow), congested central vein(red arrow), sinusoids (blue arrow), portal tract (green arrow) (H&E; x200, x400).

Fig. 3.

liver section from A.normal control group; B. TAA group; C. Silymarin group; D. D. salina Powder (12.5 mg/kg) group; E. D. salina Powder (25 mg/kg) group; F. D. salina Powder (50 mg/kg) group; G. D. salina Extract (12.5 mg/kg) group; H. D. salina Extract (25 mg/kg) dose; I. D. salina Extract (50 mg/kg) group (H&E;x 200).

Fig. 4.

liver section from A. normal control group; B. TAA group; C. Silymarin group; D. D. salina Powder (12.5 mg/kg) group; E. D. salina Powder (25 mg/kg) group; F. D. salina Powder (50 mg/kg) group; G. D. salinaExtract (12.5 mg/kg) group; H. D. salina Extract (25 mg/kg) dose; I. D. salina Extract (50 mg/kg) group (H&E;x 400).

Fig. 5A. liver section from a normal control group showed hepatic tissue with normal structure and architecture, hepatocytes arranged in thin plates (black arrow) and sinusoids (yellow arrow), central vein (red arrow). Fig. B. Liver section from TAA group showed distorted lobular hepatic architecture (black arrow) with attempts to form micro and macro regenerating nodules as complete and incomplete thick interlobular septa between portal-portal and portal-central septa (red arrow), congested blood vessels (yellow arrow). Fig. C. liver section from Silymarin group showed hepatic tissue with almost normal structure and architecture, hepatocytes arranged in thin plates with ballooning (black arrow), central vein (red arrow), and normal portal tract (yellow arrow). Fig. D. Liver section from D. salina Extract (12.5 mg/kg) showed preserved hepatic lobular architecture, with almost normal hepatocyte, congested central vein (black arrow), sinusoids (red arrow), portal tract (yellow arrow). Fig. E. Liver section from D. salina Extract (25 mg/kg) showed preserved hepatic lobular architecture, with almost normal hepatocyte, lymphocytes in portal tract and congested blood vessels (black arrow). Fig. F. Liver section from D. salina Extract (50 mg/kg) showed preserved hepatic lobular architecture, with almost normal hepatocyte, congested central vein (black arrow), normal portal tract (red arrow). Fig. G. Liver section from D. salina powder (12.5 mg/kg) showed preserved hepatic lobular architecture, with almost normal hepatocyte, sinusoids (red arrow), normal portal tract (black arrow). Fig. H. Liver section from D. salina powder (25 mg/kg) showed preserved a hepatic lobular architecture with almost normal hepatocyte, mildly congested dilated sinusoids (black arrow), portal tract mildly extended with lymphocytes (red arrow). Fig. I. Liver section from D. salina powder (50 mg/kg) showed preserved hepatic lobular architecture with almost normal hepatocyte, mildly congested dilated sinusoids (black arrow), portal tract mildly extended with lymphocytes (red arrow), bile duct (yellow arrow), blood vessel (green arrow) (Masson Trichrome x400).

Fig. 5.

liver section from A. normal control group; B. TAA group; C. Silymarin group; D. D. salina Powder (12.5 mg/kg) group; E. D. salina Powder (25 mg/kg) group; F. D. salina Powder (50 mg/kg) group; G. D. salina Extract (12.5 mg/kg) group; H. D. salina Extract (25 mg/kg) dose; I. D. salina Extract (50 mg/kg) group (Masson Trichrome x400).

5.1. Scoring of liver fibrosis

After 6 weeks of the experiment, liver fibrosis was scored where TAA group showed high fibrotic score as related to the healthy control group revealing the establishment of fibrosis. Whereas, D. salina powder or extract groups fibrotic scores indicated that D. salina intervention was effective to protect against fibrosis as compared to TAA group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of D. salina powder and extract on histopathological changes in the livers of TAA-induced rats.

| Normal control | TAA | Silymarin (50 mg/kg) | D. salina powder (12.5 mg/kg) | D. salina powder (25 mg/kg) | D. salina powder (50 mg/kg) | D. salina extract (12.5 mg/kg) | D. salina extract (25 mg/kg) | D. salina extract (50 mg/kg) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fibrosis score | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Histopathological changes; Score 0 indicates no liver fibrosis. Score 1 designates minimum liver scarring in the region of the portal tract with no septa formed. Score 2 indicates a few numbers of septa formed around the portal tract. Score 3 designatesmultiple septa formation without reaching cirrhosis. Score 4 indicates extensive.

5.2. Phytochemical analysis

The spectrophotometric analysis of the total carotenoid content in D. salina was estimated by 3381.7 μg/g D. salina powder. On the other hand, the HPLC analysis of β-carotene showed that it constituted 15.2 % of the algal extract (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Chemical structure of β-carotene of Dunaliella salina.

The GC/MS analysis of the fatty acid methyl esters showed the presence of ten fatty acids as shown in Table 4. Lauric acid was the most abundant fatty acid (33.78 %) followed by palmitic (21.12%) and palmitoleic acids (11.14%).

Table 4.

GC/MS analysis of the fatty acid methyl esters of Dunaliella salina.

| Fatty Acid | Peak no. | Retention time | Common name | Molecular formula | Peak area % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C12(0) | 1 | 11.607 | Lauric acid | CH3(CH2)10COOH | 33.78 % |

| C14(0) | 2 | 16.794 | Myristic acid | CH3(CH2)12COOH | 1.72 % |

| C15(0) | 3 | 18.271 | Pentadecylic acid | CH3(CH2)13COOH | 4.15 % |

| C16(0) | 4 | 20.490 | Palmitic acid | CH3(CH2)14COOH | 21.12 % |

| C16(1) | 5 | 21.565 | Palmitoleic acid | CH3(CH2)5CH = CH(CH2)7COOH | 11.14 % |

| C18(0) | 6 | 25.127 | Stearic acid | CH3(CH2)16COOH | 7.62 % |

| C18(1) | 7 | 25.871 | Oleic acid | CH3(CH2)7CH = CH(CH2)7COOH | 2.80 % |

| C18(2) | 8 | 26.871 | Linoleic acid | CH3(CH2)4(CH = CHCH2)2(CH2)6COOH | 5.95 % |

| C18(3) | 9 | 27.959 | Linolenic acid | CH3CH2(CH = CHCH2)3(CH2)6COOH | 8.74 % |

| C20(0) | 10 | 28.601 | Arachidic acid | CH3(CH2)18COOH | 1.64 % |

6. Discussion

Microalgae have become a source of various vital pharmaceutical products that are used for cardiac diseases, osteoarthritis, and asthma [31]. Microalgal products of high therapeutic value, as carotenoids viz., β-carotene and astaxanthin, and omega fatty acids viz., eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), act as potent antioxidants in nutraceuticals and foods [32]. In the present study, the effect of D. salina on TAA-induced hepatic fibrosis in rats was investigated for the first time.

Fibrosis is considered aworld wide major health hazard causing individual disability due to sustained cellular injury. It is the implementation of liver damage as manifested in scar formation accompanied by an alterationin liver function [33]. Hence, the discovery of novel source that can protect or halt liver fibrosisis an urgent need. TAA-induced liver fibrosis is a widely used model for liver fibrosis in animals due to the transformation of TAA into TAA sulfoxide by cytochrome P450 provoking oxidative damage to the liver [34]. It damages both zones 1 and 3 hepatocytes with a periportal injury. Additionally, it requires the least animal management and is non invasive [35]. Furthermore, mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis were proven to be involved in the TAA model of fibrosis [36]. In order to validate the protective effect of D. salina against the fibrotic effect of TAA, this study included the evaluation of liver function, oxidative stress markers, and fibrotic markers.

In the current work, the liver injury of TAA was revealed by measuring serum liver enzyme levels. Six weeks of TAA treatment induced significant elevations of AST, ALT, ALP, and bilirubin serum levels as well as a reduction of albumin serum level as compared to the normal control group. These results are confirmed by a previous study [37]. AST and ALT, liver enzymes, are released into the blood after hepatic cell damage. ALT is more specific to the liver injury and AST generally correlates to liver damage and cases of cardiac infarction and traumatic muscle injury, moreover, serum ALP and bilirubin levels are linked to hepatic cell function [38]. Albumin levels are likely to be decreased due to the impaired ability of liver cells to synthesize proteins in a chronic liver injury [39].

Treatment with D. salina powder or extract showed to be hepatoprotective, as indicated by the reduction of all liver enzymes, especially, treatment with the high dose which resulted in the normalization of the above-mentioned enzyme levels in rats which were comparable with that observed for silymarin. This indicates that D. salina powder or extract might be able to provoke the regeneration of liver cells and reducing liver enzyme leakage into the blood. These results are in line with a previous study that showed that pretreatment with D. salina microalga (1000 mg/kg) normalized liver enzyme levels in rats intoxicated with paracetamol [40]. D. salina has also been shown to be safe [41] and exert a hepatoprotective action in carbon tetrachloride-induced liver toxicity via the presence of many forms of carotene and xanthophylls [42].

In the present study, D. Salina exhibited antioxidant effects against TAA, mediated by the increase of GSH level and the inhibition of MDA level. GSH has antioxidant and anticarcinogenic tripeptide, thus improving protection against oxidant-induced cell damage [43]. Another study showed that D. salina ameliorated corneal oxidative damage provoked by UVB radiation in mice, through the stimulation of antioxidant enzyme activity and the suppression of lipid peroxidation [44]. Our results are in accordance with Sukalingam et al. [45].

Activation of HSCs was associated with elevations of hepatic contents of α-SMA and collagen I. In current work, fibrosis induced by TAA was not only reflected by a marked elevation of hepatic contents of α-SMA and collagen I but also was notable through histopathological alterations. These results were confirmed by another study, which showed that the injection of TAA increased hepatic expression of fibrosis-related genes including α-SMA, TGF-β1, and collagen I [10,46] upregulating ECM deposition [47]. The extent of hepatic fibrosis that was induced by TAA was determined by Masson's trichrome stained area in liver sections as shown in the histopathological examination and confirmed by Koppula et al. [48]. The effect of D. salina on TAA-induced liver fibrosis was determined by assessing hepatic contents of α-SMA, collagen I and histopathologic examinations. α-SMA and collagen I hepatic contents were declined in rats treated with D. salina powder or extract ameliorating ECM accumulation induced by TAA. Additionally, the histopathological examination asserted the antifibrotic effect of D. salina as evidenced by the preservation of hepatic lobular architecture and the absence of interlobular fibrous septa as compared to the TAA-treated group. Treatment with silymarin didn’t change α-SMA and collagen I hepatic contents and didn’t attenuate ECM accumulation due to its poor bioavailability, where only 20–50 % of its oral administration is absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract [49].

The phytochemical analysis of the bioactive extract of D. salina revealed a high content of carotenoids especially β-carotene that has a lot of benefits as in liver disesease and cancer [50]. It also revealed the presence of unsaturated fatty acids which may contribute to the antioxidant activity of the extract and in other studies has therapeutic effects in reproductive dysfunction [51] and in cancer [52]. Previous work of our team isolated zeaxanthin from the bioactive extract of D. salina [53]. Zeaxanthin; a xanthophyll that accumulates in the retina of the human eye and protects the retinal structures from light-induced damage, is also known for its potent antioxidant activity [54].

7. Conclusion

D. salina powder and extract showed pronounced protective activity against TAA-induced liver fibrosis via ameliorating ECM accumulation and decreasing α-SMA and collagen I. The effect was dose-dependent since 50 mg of powder and 25 mg of extract exerted the utmost protective effect. These results suggest that D. salina may be used as an effective hepatoprotective agent for the hepatic fibrosis. Further experimental and clinical trials examining the therapeutic effects of D. salina as anti-fibrotic animals and patients with liver fibrosis are proceeding.

Transparency document

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the alliance entitled "Integrated Pharmaceutical Alliance (IPA)".This alliance is funded by the Academy of Scientific Research and Technologyunder the title " Integrated Pharmaceutical Alliance (IPA) -KTA- C2-2.10".

References

- 1.de Jesus Raposo M.F., de Morais R.M., de Morais A.M. Health applications of bioactive compounds from marine microalgae. Life Sci. 2013;93:479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chidambara Murthy K.N., Vanitha A., Rajesha J., Mahadeva Swamy M., Sowmya P.R., Ravishankar G.A. In vivo antioxidant activity of carotenoids from Dunaliella salina–a green microalga. Life Sci. 2005;76:1381–1390. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Baz F.K., Hussein R.A., Mahmoud K., Abdo S.M. Cytotoxic activity of carotenoid rich fractions from Haematococcus pluvialis and Dunaliella salina microalgae and the identification of the phytoconstituents using LC-DAD/ESI-MS. Phytother. Res. 2018;32:298–304. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guzman S., Gato A., Calleja J.M. Antiinflammatory, analgesic and free radical scavenging activities of the marine microalgae Chlorella stigmatophora and Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Phytother. Res. 2001;15:224–230. doi: 10.1002/ptr.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phadwal K., Singh P.K. Isolation and characterization of an indigenous isolate of Dunaliella sp. for beta-carotene and glycerol production from a hypersaline lake in India. J. Basic Microbiol. 2003;43:423–429. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200310271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.EL-Baz F.K., Aly H.F., Ali G.H., Mahmoud R., Saad S.A. Antidiabetic efficacy of Dunaliella salina extract in STZ-induced diabetic rats. Int. J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. Arch. 2016;7:465–473. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olasehinde T.A., Olaniran A.O., Okoh A.I. Therapeutic potentials of microalgae in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Molecules. 2017;22 doi: 10.3390/molecules22030480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Baz F.K., Abdel Jaleel G.A., Saleh D.O., Hussein R.A. Protective and therapeutic potentials of Dunaliella salina on aging-associated cardiac dysfunction in rats. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2018;8:403–410. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherif I.O., Al-Gayyar M.M. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective effects of silymarin on hepatic dysfunction induced by sodium nitrite. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 2013;24:114–121. doi: 10.1684/ecn.2013.0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mansour H.M., Salama A.A.A., Abdel-Salam R.M., Ahmed N.A., Yassen N.N., Zaki H.F. The anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects of tadalafil in thioacetamide-induced liver fibrosis in rats. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2018;96:1308–1317. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2018-0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pikula K.S., Zakharenko A.M., Aruoja V., Golokhvast K.S., Tsatsakis A.M. Oxidative stress and its biomarkers in microalgal ecotoxicology. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2019;13:8–15. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreira A.J., Rodrigues G., Bona S., Cerski C.T., Marroni C.A., Mauriz J.L., Gonzalez-Gallego J., Marroni N.P. Oxidative stress and cell damage in a model of precancerous lesions and advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in rats. Toxicol. Rep. 2015;2:333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elmotasem H., Farag H.K., Salama A.A.A. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of an oral sustained release hepatoprotective caffeine loaded w/o pickering emulsion formula - containing wheat germ oil and stabilized by magnesium oxide nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2018;547:83–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blachier M., Leleu H., Peck-Radosavljevic M., Valla D.C., Roudot-Thoraval F. The burden of liver disease in Europe: a review of available epidemiological data. J. Hepatol. 2013;58:593–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez-Valle V., Chavez-Tapia N.C., Uribe M., Mendez-Sanchez N. Role of oxidative stress and molecular changes in liver fibrosis: a review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012;19:4850–4860. doi: 10.2174/092986712803341520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bansal R., Nagorniewicz B., Prakash J. Clinical advancements in the targeted therapies against liver fibrosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/7629724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li S., Tan H.Y., Wang N., Zhang Z.J., Lao L., Wong C.W., Feng Y. The role of oxidative stress and antioxidants in liver diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:26087–26124. doi: 10.3390/ijms161125942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez A.K., Maroni L., Marzioni M., Ahmed S.T., Milad M., Ray D., Alpini G., Glaser S.S. Mouse models of liver fibrosis mimic human liver fibrosis of different etiologies. Curr. Pathobiol. Rep. 2014;2:143–153. doi: 10.1007/s40139-014-0050-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yanguas S.C., Cogliati B., Willebrords J., Maes M., Colle I., van den Bossche B., Souza de Oliveira C.P.M., Andraus W., Ferreira Alves V.A., Isabelle LeclercqVinken M. Experimental models of liver fibrosis. Arch. Toxicol. 2016;90:1025–1048. doi: 10.1007/s00204-015-1543-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernández‐Sevilla J.M., Acién‐Fer nández F.G., Molina‐Grima E. Biotechnological production of lutein and its applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;86:27–40. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2420-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Carvalho L.M.J., Gomes P.B., Godoy R.L., Pacheco S., do Monte P.H.F., de Carvalho J.L.V., Nutti M.R., Neves A.C.L., Vieira A.C.R.A., Ramos S.R.R. Total carotenoid content, α-carotene and β-carotene, of landrace pumpkins (Cucurbita moschata Duch): a preliminary study. Food Res. Int. 2012;47:337–340. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bai T., Yang Y., Wu Y.L., Jiang S., Lee J.J., Lian L.H., Nan J.X. Thymoquinone alleviates thioacetamide-induced hepatic fibrosis and inflammation by activating LKB1-AMPK signaling pathway in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2014;19:351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim J.S., Koppula S., Yum M.J., Shin G.M., Chae Y.J., Hong S.M., Lee J.D., Song M. Anti-fibrotic effects of Cuscuta chinensis with in vitro hepatic stellate cells and a thioacetamide-induced experimental rat model. Pharm. Biol. 2017;55:1909–1919. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2017.1340965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reitman S., Frankel S. 1957. A Colorimetric Method for the Determination of Serum Glutamic Oxalacetic and Glutamic Pyruvic Transminases. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belfield A., Goldberg D. Colorimetric determination of alkaline phosphatase activity. Enzyme. 1971;12:561–568. doi: 10.1159/000459586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walters M.I., Gerarde H. An ultramicromethod for the determination of conjugated and total bilirubin in serum or plasma. Microchem. J. 1970;15:231–243. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doumas B.T., Watson W.A., Biggs H.G. Albumin standards and the measurement of serum albumin with bromcresol green. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1971;31:87–96. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(71)90365-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beutler E., Duron O., Kelly B.M. Improved method for the determination of blood glutathione. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1963;61:882–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohkawa H., Ohishi N., Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal. Biochem. 1979;95:351–358. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brunt E.M. Grading and staging the histopathological lesions of chronic hepatitis: the Knodell histology activity index and beyond. Hepatology. 2000;31:241–246. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adarme-Vega T.C., Lim D.K., Timmins M., Vernen F., Li Y., Schenk P.M. Microalgal biofactories: a promising approach towards sustainable omega-3 fatty acid production. Microb. Cell Fact. 2012;11:96. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khan M.I., Shin J.H., Kim J.D. The promising future of microalgae: current status, challenges, and optimization of a sustainable and renewable industry for biofuels, feed, and other products. Microb. Cell Fact. 2018;17:36. doi: 10.1186/s12934-018-0879-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Attar A.M. Attenuating effect of Ginkgo biloba leaves extract on liver fibrosis induced by thioacetamide in mice. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/761450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wasser S., Ho J.M., Ang H.K., Tan C.E. Salvia miltiorrhiza reduces experimentally-induced hepatic fibrosis in rats. J. Hepatol. 1998;29:760–771. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80257-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Starkel P., Leclercq I.A. Animal models for the study of hepatic fibrosis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2011;25:319–333. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mostafa R.E., Salama A.A.A., Abdel-Rahman R.F., Ogaly H.A. Hepato- and neuro-protective influences of biopropolis on thioacetamide-induced acute hepatic encephalopathy in rats. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2017;95:539–547. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2016-0433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Afifi N.A., Ramadan A., El-Eraky W., Salama A.A.A., El-Fadaly A.A., Hassan A. Quercetin protects against thioacetamide induced hepatotoxicity in rats through decreased oxidative stress biomarkers, the inflammatory cytokines; (TNF-α), (NF-κ B) and DNA fragmentation. Der Pharma Chemica. 2016;8:48–55. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muriel P., Garciapina T., Perez-Alvarez V., Mourelle M. Silymarin protects against paracetamol-induced lipid peroxidation and liver damage. J. Appl. Toxicol. 1992;12:439–442. doi: 10.1002/jat.2550120613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao Y., Ma X., Wang J., He X., Hu Y., Zhang P., Wang R., Li R., Gong M., Luo S., Xiao X. Curcumin protects against CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in rats by inhibiting HIF-1alpha through an ERK-dependent pathway. Molecules. 2014;19:18767–18780. doi: 10.3390/molecules191118767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madkour F.F., Abdel-Daim M.M. Hepatoprotective and antioxidant activity of Dunaliella salina in paracetamol-induced acute toxicity in rats. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2013;75:642–648. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El-Baz F.K., Aly H.F., Salama A.A.A. Toxicity assessment of the green Dunaliella salina microalgae. Toxicol. Rep. 2019;6:850–861. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2019.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chidambara Murthy K.N., Rajesha J., Vanitha A., Swamy M.M., Ravishankar G.A. Protective effect of Dunaliella salina-A marine micro alga, against carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Hepatol. Res. 2005;33:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mansour D.F., Salama A.A.A., Hegazy R.R., Omara E.A., Nada S.A. Whey protein isolate protects against cyclophosphamide-induced acute liver and kidney damage in rats. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2017;7:111–120. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsai C.F., Lu F.J., Hsu Y.W. Protective effects of Dunaliella salina - a carotenoids-rich alga - against ultraviolet B-induced corneal oxidative damage in mice. Mol. Vis. 2012;18:1540–1547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sukalingam K., Ganesan K., Xu B. Protective effect of aqueous extract from the leaves of Justicia tranquebariesis against thioacetamide-induced oxidative stress and hepatic fibrosis in rats. Antioxidants (Basel) 2018;7 doi: 10.3390/antiox7070078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paik Y.H., Yoon Y.J., Lee H.C., Jung M.K., Kang S.H., Chung S.I., Kim J.K., Cho J.Y., Lee K.S., Han K.H. Antifibrotic effects of magnesium lithospermate B on hepatic stellate cells and thioacetamide-induced cirrhotic rats. Exp. Mol. Med. 2011;43:341–349. doi: 10.3858/emm.2011.43.6.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Romualdo G.R., Grassi T.F., Goto R.L., Tablas M.B., Bidinotto L.T., Fernandes A.A.H., Cogliati B., Barbisan L.F. An integrative analysis of chemically-induced cirrhosis-associated hepatocarcinogenesis: histological, biochemical and molecular features. Toxicol. Lett. 2017;281:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2017.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koppula S., Yum M.J., Kim J.S., Shin G.M., Chae Y.J., Yoon T., Chun C.S., Lee J.D., Song M. Anti-fibrotic effects of Orostachys japonicus A. Berger (Crassulaceae) on hepatic stellate cells and thioacetamide-induced fibrosis in rats. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2017;11:470–478. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2017.11.6.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohsen A.M., Asfour M.H., Salama A.A.A. Improved hepatoprotective activity of silymarin via encapsulation in the novel vesicular nanosystem bilosomes. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2017;43:2043–2054. doi: 10.1080/03639045.2017.1361968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Y., Zhu X., Huang T., Chen L., Liu Y., Li Q., Song J., Ma S., Zhang K., Yang B., Guan F. Beta-carotene synergistically enhances the anti-tumor effect of 5-fluorouracil on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in vivo and in vitro. Toxicol. Lett. 2016;261:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li Y., Liu L., Wang B., Xiong J., Li Q., Wang J., Chen D. Impairment of reproductive function in a male rat model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and beneficial effect of N-3 fatty acid supplementation. Toxicol. Lett. 2013;222:224–232. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.05.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nikolakopoulou Z., Shaikh M.H., Dehlawi H., Michael-Titus A.T., Parkinson E.K. The induction of apoptosis in pre-malignant keratinocytes by omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) is inhibited by albumin. Toxicol. Lett. 2013;218:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.El-Baz F.K., Hussein R.A., Saleh D.O., Abdel Jaleel G.A.R. Zeaxanthin isolated from Dunaliella salina microalgae ameliorates age associated cardiac dysfunction in rats through stimulation of retinoid receptors. Mar. Drugs. 2019;17 doi: 10.3390/md17050290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Madhavan J., Chandrasekharan S., Priya M.K., Godavarthi A. Modulatory effect of carotenoid supplement constituting lutein and zeaxanthin (10:1) on anti-oxidant enzymes and macular pigments level in rats. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2018;14:268–274. doi: 10.4103/pm.pm_340_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.