Abstract Abstract

Knowledge of sequestrate Hysterangiaceae fungi in Mexico is very limited. In the present study, a new member of the family, Aroramyces guanajuatensissp. nov., is described. This speciesis closely related to A. balanosporus, but differs from the latter in possessing a tomentose peridium 165–240 µm thick, with occasional large terminal hyphae up to 170 µm, a variable mesocutis (isodiametric to angular), and distinct bright yellowish subcutis. In contrast, A. balanosporus possesses a fibrillose peridial surface with shorter hyphae, a peridium 200–450 µm thick, and a mainly hyaline isodiametric mesocutis with a slightly wider subcutis. The phylogenetic analysis of the LSU gene separated A. guanajuatensis from A. balanosporus with a Bayesian posterior probability (PP) = 1. This is the third Aroramyces species described for the American continent.

Keywords: Truffle, truffle-like, sequestrate fungi, hypogeous fungi

Introduction

Aroramyces Castellano and Verbeken was coined to settle Hymenogaster radiatus (Lloyd, 1925) and Hysterangium gelatinosporum (Cribb, 1957) from two different genera (Castellano et al. 2000). Phylogenetic analysis places Aroramyces near, but different to Hysterangium (Hosaka et al. 2006, 2008). Aroramyces is characterized by its unique combination of a brown gleba, spiny spores with distinctly inflated utricles, gelatinized gleba, and basidiome with a tomentose surface with numerous soil particles adhering to all sides. At present, there are four species in this group (Kirk 2018): Aroramyces radiatus (Lloyd) Castellano, Verbeken & Walleyn, A. gelatinosporus (J.W. Cribb) Castellano (Castellano et al. 2000), A. balanosporus G. Guevara & Castellano, and A. herrerae G. Guevara, Gomez-Reyes & Castellano (Guevara-Guerrero et al. 2016). Aroramyces guanajuatensis was discovered during a survey aiming to document the fugal diversity in Guanajuato, Mexico. It is therefore determined that the number of Aroramyces species described in the American continent is now three.

Materials and methods

Sampling and morphological characterization

The collections were discovered with a cultivator, digging around trees up to a depth of 15 cm. All encountered fruiting bodies were photographed fresh and then dried at 50 °C. The chosen material was cut by hand and rehydrated with 5% KOH for morphological studies. Thirty spores were measured. Peridial slices were made and observed under optical microscopy (Castellano et al. 1989). For scanning electron microscopy pictures (JSM5600LV, JOEL, Tokyo, Japan), the spores were coated with gold and palladium. Voucher collections are deposited at José Castillo Tovar (ITCV) Herbarium, Instituto Tecnólogico de Ciudad Victoria, Mexico.

DNA extraction, amplification, sequencing and phylogenetic analyses

Genomic DNA was obtained with CTAB (Martínez-González et al. 2017)) or using Fungal DNA extraction Kit (Bio Teke Corporation, China) from 2–3 mg of dry tissue. DNA quantification was performed with Nanodrop (Thermo, USA). Each sample was diluted to 20 ng/uL for PCR amplification. LR0R and LR5 primers were used to amplify the LSU gene (Vilgalys and Hester 1990). The PCR reaction contained the following: enzyme buffer 1×, Taq DNA polymerase, 0.8 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (0.2 mM each), 100 ng DNA, 20 pmol of each primer, and 2 units of GoTaq DNA (Promega, USA), with a final volume of 15 µL. The amplification program was run as follows: denaturalization at 96 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles of denaturalization at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 57 °C for 1 min, polymerization at 72 °C for 1 min, and final elongation at 72 °C for 5 min. All PCR reactions were carried out in a Peltier Thermal Cycler PTC-200 (BIORAD, Mexico). The PCR products were verified by agarose gel electrophoresis run for 1 h at 95 V cm-3 in 1.5% agarose and 1× TAE buffer (Tris Acetate-EDTA). The products were then dyed with GelRed (Biotium, USA) and viewed in a transilluminator (Infinity 3000 Vilber, Loumat, Germany). Finally, the products were purified using the ExoSap Kit (Affymetrix, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and were prepared for the sequencing reaction using the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit v. 3.1 (Applied BioSystems).

Sequencing was carried out in a genetic analyzer (Model 3130XL, Applied BioSystems, USA) at the Biology Institute of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). The sequences of both strains of each sample were analyzed, edited, and assembled using BioEdit v. 1.0.5 (Hall 1999) to create consensus sequences. The consensus sequences were compared with those in the GenBank database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) using the BLASTN 2.2.19 tool (Zhang et al. 2000). The LSU region was aligned using the online version of MAFFT v. 7 (Katoh et al. 2002, 2017; Katoh and Standley 2013). The alignment was revised in PhyDE (Müller et al. 2005), and small manual adjustments were then made to maximize the similarity between characters. The matrix was composed of 30 taxa (640 characters) (Table 1). Ramaria gelatinosa (access number AF213091) was used as the outgroup. The phylogeny was performed using Bayesian inference in MrBayes v. 3.2.6 64× (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist 2001). The information block matrix included two independent runs of the MC3 chains for ten million generations (standard deviation ≤ 0.01); the reversible-jump strategy was used (Huelsenbeck et al. 2004). An evolutionary model was used, so a proportion of invariable sites were designated, and the other proportion came from a gamma distribution (invgamma). The convergence of chains was visualized in Tracer v. 1 (Rambaut et al. 2014). The phylogram of maximum credibility for the clades was recovered in TreeAnotator v. 1.8 (Bouckaert et al. 2014) based on the burning of 2.5 million trees.

Table 1.

List of NCBI accession numbers for LSU and ITS sequences of Aroramyces guanajuatensis.

| Herbarium number | LSU NCBI number | ITS NCBI number |

|---|---|---|

| ITCV 1689 | MK761021 | MN392935 |

| ITCV 1691 | MK761022 | MN392936 |

| ITCV 1694 | MK761023 | MN392937 |

| ITCV 1711 | MK761024 | MN392938 |

| ITCV 1610 | MK761025 | MN392939 |

| ITCV 1610 | MK811035 | – |

| ITCV 1613 | MK761026 | MN392940 |

| ITCV 1613 | MK811036 | – |

| ITCV 1729 | MK761027 | MN392941 |

| ITCV 1731 | MK761028 | MN392942 |

| ITCV 1734 | MK761029 | MN392943 |

| ITCV 1738 | MK761030 | MN392944 |

| ITCV 1739 | MK761031 | MN392945 |

| ITCV 1741 | MK761032 | MN392946 |

Results

Molecular analyses

ITS and LSU sequences of 12 samples of A. guanajuatensis were obtained (Table 1). ITS and LSU sequences are respectively identical. Based on this, only four sequences were selected for phylogenetic analysis. Then after, alignment was performed with 6 sequences of Aroramyces and 22 sequences of Hysterangium (Table 2). Phylogenetic results were as follows: According to the Bayesian analysis, after 10 million generations, 25% trees were discarder as the burn-in. The standard deviation between the chains stabilized at 0.002, indicating that MC3 reached a stationary phase. To confirm that the sample size was enough, the “parameter” file was analyzed using Tracer v. 1.6 (Rambaut et al. 2014), verifying that all parameters had an estimated sample size above 1,500. The subsequent probabilities (SP) were estimated based on the strict consensus rule produced by MrBayes and indicated on the maximum credibility clade tree. The Bayesian inference analysis recovered A. guanajuatensis as a monophyletic group, with a posterior probability of 1. (Fig. 1). Ramaria gelatinosa was used to root the tree. Aroramyces balanosporus and A. guanajuatensis showed the closest relationship but were branched with a probability of 1 and a dissimilarity of 2.19, supporting the existence of a new taxon. The Hysterangium species segregated and formed two different branches.

Table 2.

List of Aroramyces and Hysterangium species, GenBank accession numbers, and references for LSU sequences used in the phylogenetic analysis. Sequences of new taxon are in bold.

| Species | GenBank | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Aroramyces balanosporus G. Guevara & Castellano | MK811031 | This paper |

| A. guanajuatensis | MK761024 | This paper |

| MK811036 | This paper | |

| MK811035 | This paper | |

| MK761031 | This paper | |

| A. gelatinosporus (J.W. Cribb) Castellano | DQ218524 | Hosaka et al. 2008 |

| A. radiatus (Lloyd) Castellano, Verbeken & Walleyn | DQ218525 | Hosaka et al. 2008 |

| Aroramyces sp. | KY686203 | Nuske & Abell unpublished |

| DQ218527 | Hosaka et al. 2008 | |

| DQ218530 | Hosaka et al. 2008 | |

| Hysterangium affine Mase & Rodway | DQ218546 | Hosaka et al. 2008 |

| H. album Zeller & C.W. Dodge | DQ218490 | Hosaka et al. 2008 |

| H. aureum Zeller | DQ218491 | Hosaka et al. 2008 |

| H. calcareum R. Hesse | DQ218492 | Hosaka et al. 2008 |

| H. clathroides Vittad | AF213121 | Humpert et al. unpublished |

| H. coriaceum R. Hesse | AF213122 | Humpert et al. unpublished |

| AY574686 | Giachini et al. 2010 | |

| H. crassum (Tul & C. Tul) E, Fisch | AY574687 | Giachini et al. 2010 |

| H. epiroticum Pacioni | DQ218495 | Hosaka et al. 2008 |

| H. fragile Vittad | DQ218496 | Hosaka et al. 2008 |

| H. hallingi Castellano & J.J. Muchovej | DQ218497 | Hosaka et al. 2008 |

| H. inflatun Rodway | DQ218549 | Hosaka et al. 2008 |

| H. membranaceum Vittad | DQ218498 | Hosaka et al. 2008 |

| H. neotunicatun Castellano & Beever | DQ218550 | Hosaka et al. 2008 |

| H. pompholyx Tul. & C. Tul. | DQ218499 | Hosaka et al. 2008 |

| H. rugisporum Castellano & Beever | DQ218500 | Hosaka et al. 2008 |

| H. salmonaceum G.W. Beaton, Pegler & T.W.K. Young | DQ218501 | Hosaka et al. 2008 |

| H. separabile Zeller | DQ974810 | Smith et al. 2007 |

| DQ218502 | Hosaka et al. 2008 | |

| H. spegazzinii Castellano & J.J. Muchovej | DQ218503 | Hosaka et al. 2006 |

| H. stoloniferum Tul. & C. Tul. | AF336259 | Binder and Bresinsky 2002 |

| H. strobilus Zeller & C.W. Dodge | DQ218504 | Hosaka et al. 2006 |

Figure 1.

Maximum probability phylogram of clades obtained with Bayesian inference. The posterior probabilities for each clade are shown on the branches. The accession numbers in the sequence labels indicate the GenBank accession numbers.

Taxonomy

Aroramyces guanajuatensis

Peña-Ramírez, Guevara-Guerrero, Z. W. Ge & Martínez-González sp. nov.

3F46ADC5-EDF7-57F8-8EF8-CFB4304059F2

30329

Figure 2.

a–fAroramyces guanajuatensis (holotype ITCV 1613) a, b basidiome showing the peridial surface c basidiome in cross-section showing glebal surface d cross-section of peridium showing three-layered peridium (1 epicutis, 2 mesocutis, 3 subcutis) at 400× e–f basidiospore 1000× f irregular crest contained within an inflated utricle. Scale bars: 0.5 cm (a–c, f), 20 µm (d), 5 µm (e).

Figure 3.

Electronic photomicrograph of basidiospores aAroramyces balanosporus (ITCV 848) and bAroramyces guanajuatensis (ITCV 1739). Scale bars: 5 µm.

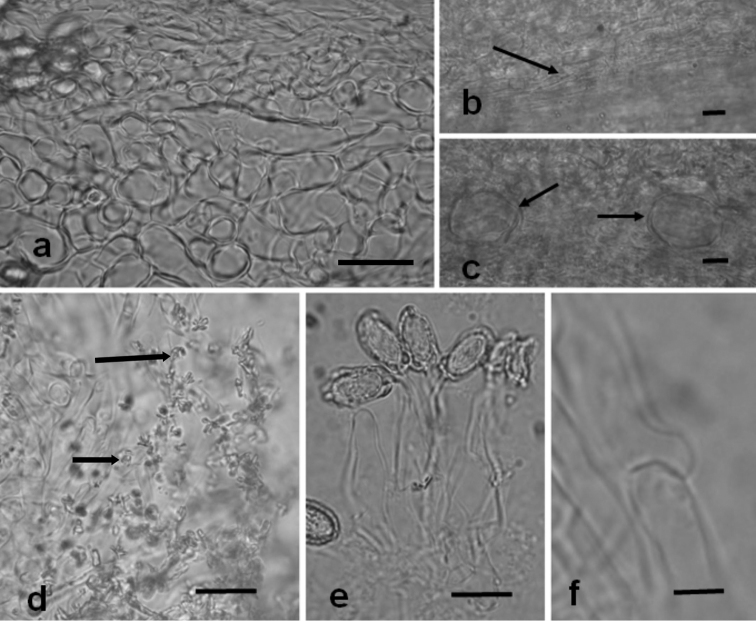

Figure 4.

a–fAroramyces guanajuatensis (holotype ITCV 1613) a–c Cross-section of peridium a epicutis of hyphae postrate cells and angular pseudoparenchyma like mesocutis b arrow head showing postrate cell subcutis c arrow head showing large cell scattered in subcutis d arrow head showing epicutis hyphae with attached crystals e basidia and basidioles f epicutis clamp connection. Scale bar: 10 µm (a–c, e), 25 µm (d), 5 µm (f).

Type.

MEXICO. State of Guanajuato, municipality of Guanajuato, Cuenca de la Esperanza Protected Natural Area, 7 November. 2016Peña-Ramírez 108 (Holotype: ITCV 1613).

Diagnosis.

Aroramyces guanajuatensis is characterized by a peridium 167–240 µm thick, of cotton-like hyphae, up to 170 µm, long, variably structured mesocutis, yellowish subcutis, spores with irregular and inflated utricle.

Etymology.

"guanajuatensis" in reference to the site (Guanajuato state) where the new taxon was discovered.

Description.

Basidiome 4.4–17×3.9–13.5×3.2–11.2 mm, globose or subglobose to irregular, sometimes compressed when growing together. Peridial surface white, pale brown, fibrillose or tomentose, often with cotton-like patches of white hyphae encompassing some debris soil, stones, leaves, and roots. Peridium Separable and fragile, exposing portions of the gleba. < 0.5 mm thick, mostly hyaline, outer portion pale brown, with a dark ring next to the gleba. Gleba brown, trama gelatinized, locules irregularly shaped, columella dendroid, translucent gray. Odor fungoid; taste not recorded. Basidiomata hard wen dried.

Peridium three layered, 165–240 µm thick. Epicutis 7.5–22.5 µm thick of hyaline to reddish brown, thin-walled, interwoven to repent or erect hyphae, 2–9 µm wide, forming scattered caespitose groups of erect, branched, setal hyphae up to 170 µm long, with abundant crystalline structures adherent on hyphal walls, clamp connections present. Mesocutis 55–105 µm thick, abundant hyaline, isodiametric, globose to subglobose, angular pseudoparenchyma like cells. 4–35×3–24 µm, also with some irregularly shaped, interwoven hyphae, 3–11 µm wide. walls 1–2 µm µm wide, clamp connection absent. Subcutis 22.5–95 µm thick, of interwoven prostrate hyphae, 3–4 µm broad, with scattered large pseudoparenchyma like cells up to 37.5×30 µm, clamp connection absent.

Trama of hyaline, interwoven hyphae 4 µm wide, embedded in a gelatinized matrix, clamp connections present.

Basidia fusoid to clavate, hyaline, 14–48 × 9–12 µm, mean = 32.5 × 10.3 µm, wall 1 µm thick. Basidiospores ellipsoid to broadly ellipsoid, symmetrical, hyaline to pale brown, slightly reddish in KOH, pale brown in mass, excluding utricle 9–13 × 6–7 µm long, mean = 11 × 6.1 µm, Q range = 1.5–2.17, Q mean = 1.8; with utricle 12–17 × 7–10 µm long, mean = 14.47 × 8.27 µm, Q = 1.5–2.13, mean = 1.76. Ornamentation of irregular crest contained within an inflated utricle, hilar appendage in cross-section appears rectangular, 1–3 × 4–6 µm, mean = 1.97 × 5.2 µm. Apex obtuse. Utricle inflated up to 3 µm from spore wall, mean = 1.43 µm, occasionally the utricle is asymmetrically inflated.

Distribution, habit and ecology.

MEXICO, state of Guanajuato. Cuenca de la Esperanza Protected Natural Area. Hypogeous, under Quercus spp. at 2530 m. 21°03.87'N, 101°13.193'W. October to December. The March collection was dried in situ.

Additional material examined.

Mexico, state of Guanajuato, Cuenca de la Esperanza Protected Natural Area: 21°04.075'N, 101°13.193'W 2500 m, 26 October 2016, Peña-Ramírez 102, paratype (ITCV 1610). 21°03891'N, 101°13.531'W 2457 m, 5 October 2016, Peña-Ramírez 70 (ITCV 1689). 21°03.891'N, 101°13.533'W, 2464 m, 5 October 2016, Peña-Ramírez 72 (ITCV 1691). 21°03.88'N, 101°13.561'W, 2471 m, 5 October 2016, Peña-Ramírez 75 (ITCV 1694). 21°03.85'N, 101°13.278'W. 2533 m, 19 October 2016 Peña-Ramírez 92 (ITCV 1711). 21°03.741'N, 101°13.461'W. 2500 m, 14 November 2016, Peña-Ramírez 110 (ITCV 1729). 21°03.901'N, 101°13.551'W. 22 December 2016, Peña-Ramírez 119 (ITCV 1738). 21°03.905'N, 101°13.018'W. 2458 m. 22 December 2016, Peña-Ramírez 120 (ITCV 1739). 21°04.045'N, 101°13.018'W. 2508 m, 6 March 2017, Peña-Ramírez 122 (ITCV 1741).

Discussion

In the Bayesian inference analysis, Various Aroramyces nest together along with undescribed species mentioned in Nuske & Abell (unpublished) and Hosaka et al. (2008). The clade of the genus Aroramyces segregated between two clades that group species of Hysterangium. The close relationship of Aroramyces to Hysterangium in our study agrees with Hosaka et al. (2006, 2008). Aroramyces balanosporus and A. guanajuatensis are closely related but are morphologically and molecularly distinct (Figure 1). Although, the objective of the current assignment is not inferring the phylogenetic relationships in Hysterangiaceae, the result clearly supports Aroramyces guanajuatensis to be an independent species within the genus Aroramyces with a posterior probability of 1.

The hilar appendage is larger in Aroramyces guanajuatensis compared to A. balanosporus. The isodiametric mesocutis cells of A. guanajuatensis differ from the variously shaped cells in the mesocutis of A. balanosporus. The asymmetric utricle of Aroramyces herrerae up to 6 µm wide whereas the asymmetric utricle of A. guanajuatensis rarely reaches 3 µm wide. Mexican Aroramyces are associated with Quercus spp. Interestingly A. radiatus from Africa has smaller spores, 10–12(–13.5) × 6–7(–8) μm, and is associated with Brachystegia spiciformis (Caesalpinioideae) and Upaca sp. (Euphorbiaceae). Aroramyces gelatinosporus from Australia has similar sized spores but a single-layered peridium and is associated with Eucalyptus spp. (Myrtaceae) (Castellano et al. 2000; Lloyd 1925).

The collections were discovered in the Cuenca de la Esperanza Protected Natural Area in Guanajuato, Mexico, located north of Michoacán and east of Jalisco. The presence of unidentified species in this region highlights the importance of this protected natural area and as an area to search for additional new fungal taxa.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Peña-Ramírez acknowledges TecNM (Tecnológico Nacional de México) for fellowship PRODEP 1264-2015-2017. Guevara-Guerrero thanks CONACyT and TecNM for research support. Martínez-González acknowledges Laura Márquez y Nelly López, LaNaBio, of Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and to María Eugenia Muñiz Díaz de León, for giving us access to the Laboratory of Molecular Biology. Zai-Wei was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31670024 and 31872619).

Citation

Peña-Ramírez R, Ge Z-W, Gaitán-Hernández R, Martínez-González CR, Guevara-Guerrero G (2019) A novel sequestrate species from Mexico: Aroramyces guanajuatensis sp. nov. (Hysterangiaceae, Hysterangiales). MycoKeys 61: 27–37. https://doi.org/10.3897/mycokeys.61.36444

References

- Binder M, Bresinsky A. (2002) Derivation of a polymorphic lineage of Gasteromycetes from boletoid ancestors. Mycologia 94(1): 85–9. 10.1080/15572536.2003.11833251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouckaert R, Heled J, Kühnert D, Vaughan T, Wu C-H, Xie D, Suchard MA, Rambaut A, Drummond AJ. (2014) BEAST 2: A software platform for Bayesian Evolutionary analysis. PLOS Computational Biology 10: e1003537. https://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Castellano MA, Trappe JM, Maser Z, Maser C. (1989) Key to spores of the genera of Hypogeous fungi of north temperate forest with special reference to animal mycophagy. Mad River press, Eureka, 186 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano MA, Verbeken A, Walleyn R, Thoen D. (2000) Some new or interesting sequestrate Basidiomycota from African woodlands. Karstenia 40: 11–21. 10.29203/ka.2000.346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cribb JW. (1957) The Gasteromyces of Queensland – IV Gautieria, Hysterangium and Gymnoglossum. Papers of the Department of Botany University of Queensland 3[1958]: 153–159. The University of Queensland Press.

- Giachini AJ, Hosaka K, Nouhra E, Spatafora J, Trappe JM. (2010) Phylogenetic relationships of the Gomphales based on nuc-25S-rDNA, mit-12S-rDNA, and mit-atp6-DNA combined sequence. Fungal Biology 114(2–3): 224–234. 10.1016/j.funbio.2010.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guevara-Guerrero G, Castellano MA, Gómez-Reyes V. (2016) Two new Aroramyces species (Hysterangiaceae, Hysterangiales) from México. IMA Fungus 7(2): 235–238. https://imafungus.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.5598/imafungus.2016.07.02.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. (1999) BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series 41: 95–98. http://brownlab.mbio.ncsu.edu/JWB/papers/1999hall1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hosaka K, Bates ST, Beever RE, Castellano MA, Colgan W III, Dominguez LS, Nouhra ER, Geml J, Giachini AJ, Kenney SR, Simpson NB, Spatafora JW, Trappe JM. (2006) Molecular phylogenetics of the gomphoid-phalloid fungi with an establishment of the new subclass Phallomycetidae and two new orders. Mycologia 98(6): 949–959. 10.1080/15572536.2006.11832624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosaka K, Castellano MA, Spatafora JW. (2008) biogeography of Hysterangiales (Phallomycetidae, Basidiomycota). Mycological Research 112: 448–462. 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck J, Ronquist F. (2001) MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 17(8): 754–755. 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck JP, Larget B, Alfaro ME. (2004) Bayesian phylogenetic model selection using reversible jump Markov Chain Montecarlo. Molecular Biology and Evolution 21: 1123–1133. 10.1093/molbev/msh123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, Miyata T. (2002) MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Research 30(14): 3059–3066. 10.1093/nar/gkf436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Standley DM. (2013) MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30(4): 772–780. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Rozewicki J, Yamada KD. (2017) MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Briefings in Bioinformatics 20(4): 1160–1166. 10.1093/bib/bbx108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk P. (2018) Index fungorum. http://www.indexfungorum.org

- Lloyd CG. (1925) Mycological Writings, Mycological Notes 7: 1304. https://ia600501.us.archive.org/6/items/indexofmycologic07lloy/indexofmycologic07lloy.pdf

- Martínez-Gonzalez CR, Ramírez-Mendoza R, Jiménez-Ramírez J, Gallegos-Vázquez C, Luna-Vega I. (2017) Improved method for Genomic DNA Extraction for Opuntia Mill. (Cactaceae). Plant Methods 13: 1–82. 10.1186/s13007-017-0234-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller K, Quandt D, Müller J, Neinhuis C. (2005) PhyDE-Phylogenetic data editor. Program distributed by the authors, version 10.0. https://www.phyde.de

- Rambaut A, Suchard MA, Xie D, Drummond AJ. (2014) Tracer v1.6. http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/Tracer

- Smith ME, Douhan GW, Rizzo DM. (2007) Ectomycorrhizal community structure in a xeric Quercus Woodland based on rDNA sequence analysis of sporocarps and pooled roots. New Phytologist 174(4): 847–863. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02040.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilgalys R, Hester M. (1990) Rapid Genetic Identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. Journal of Bacteriology 172(8): 4238–4246. 10.1128/jb.172.8.4238-4246.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Schwartz S, Wagner L, Miller W. (2000) A greedy algorithm for aligning DNA sequences. Journal of Computational Biology 7: 203–214. 10.1089/10665270050081478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.