Abstract

Mammalian TCRβ loci contain 30 Vβ gene segments upstream and in the same transcriptional orientation as two DJCβ clusters, and a downstream Vβ (TRBV31) in the opposite orientation. The textbook view is upstream Vβs rearrange only by deletion, and TRBV31 rearranges only by inversion, to create VβDJCβ genes. Here, we show in mice that upstream Vβs recombine through inversion to the DJCβ2 cluster on alleles carrying a pre-assembled Trbv31-DJCβ1 gene. When this gene is in-frame, Trbv5 evades TCRβ-signaled feedback inhibition and recombines by inversion to the DJCβ2 cluster, creating αβ T cells that express assembled Trbv5-DJCβ2 genes. On alleles with an out-of-frame Trbv31-DJCβ1 gene, most upstream Vβs recombine at low levels and promote αβ T cell development, albeit with preferential expansion of Trbv1-DJβ2 rearrangements. Finally, we show wild-type Tcrb alleles produce mature αβ T cells that express upstream Vβ peptides in surface TCRs and carry Trbv31-DJβ2 rearrangements. Our study indicates two successive inversional Vβ-to-DJβ rearrangements on the same allele can contribute to the TCRβ repertoire.

Introduction

The generation of large numbers of diverse T cell receptor (TCR) and immunoglobulin (Ig) genes through V(D)J recombination is the basis for adaptive immunity in jawed vertebrates (1). Germline TCRα, β, γ, and δ and Ig heavy (H) and light (L) chain loci consist of variable (V), joining (J), and sometimes diversity (D), gene segments upstream of constant (C) region exons. In developing T and B cells, the lymphocyte-specific RAG1/RAG2 (RAG) endonuclease induces DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) between a pair of gene segments with compatible flanking recombination signal sequences (RSSs), yielding blunt signal ends and hairpin-sealed coding ends (2). RAG and DSB repair proteins fuse signal ends to produce signal joins and open, process, and fuse coding ends to create V(D)J coding joins (2). Resultant V(D)J joins encode the antigen binding surfaces of TCR or Ig proteins and are transcribed and spliced with C exons to produce V(D)JC mRNAs. The number of V(D)J joining events and inherent imprecision of coding join formation together generate enormous numbers of diverse TCR and Ig genes that provide vital immunity. However, errors in regulation of V(D)J recombination can cause immunodeficiency, autoimmunity, or translocations that promote lymphoid cancers (1).

V(D)J recombination and lymphocyte development are inter-dependently regulated processes (3–5). Common lymphoid progenitors differentiate into CD4−CD8− double-negative (DN) thymocytes or pro-B cells that assemble TCRβ, γ, and δ or IgH genes, respectively. The assembly of in-frame VJγ and VDJδ coding joins yields γδ TCRs that signal development of γδ T cells, while the assembly of in-frame VDJβ or VDJH coding joins produces TCRβ or IgH proteins that signal development to CD4+CD8+ double-positive (DP) thymocytes or pre-B cells (3–5). TCRβ and IgH gene assembly occurs via D-to-J recombination, followed by the joining of a V segment to a DJ complex on one allele at a time (6, 7). When the initial VDJ joins are out-of-frame, cells can perform V-to-DJ recombination on the other allele in another attempt to assemble in-frame genes (6, 7). Yet, when initial VDJ joins are in-frame, the resultant proteins signal feedback inhibition of further V-to-DJ rearrangements to enforce mono-allelic expression (allelic exclusion) of TCRβ and IgH (6, 7). This regulation of V(D)J recombination ensures most cells express one type of TCRβ or IgH protein and subsequently antigen receptors of a single unique specificity. DP thymocytes and pre-B cells assemble TCRα or Igκ and λ genes via VJ joining (3–5). In-frame VJ rearrangements generate proteins that can pair with TCRβ or IgH proteins. When successful, resultant αβ TCRs or B cell receptors signal positive selection of mature αβ T cells or B cells, or negative selection if receptors are too highly self-reactive (3–5).

Transcriptional enhancers and promoters and genome topology each control lymphocyte lineage- and development stage-specific assembly and expression of TCR and Ig genes (8, 9). TCRβ and TCRα/δ and IgH and Igκ loci are comprised of numerous V segments dispersed across ~0.5–2 Mb genomic distances and situated ~60–200 kb 5’ of smaller numbers of closely spaced D/J-C segments. These loci have one or two enhancers at their D/J-C ends and promoters associated with D/J and V segments. The enhancers activate D/J promoters to enable RAG access and create focal recombination centers (RCs) over D/J segments (10, 11). These enhancer/promoter-dependent RCs drive D-to-J recombination and/or capture accessible V segments to promote V-to-(D)J recombination (10). The V promoters stimulate transcription and recombination of germline V segments and transcription and expression of assembled V(D)J-C genes (12). The compaction of TCR and Ig loci by formation of chromosome loops between the V and D/J-C ends promotes efficient V-to-(D)J rearrangement and broad utilization of V segments (8). Within antigen receptor loci, the activities of transcription factors, enhancers, and CTCF and Cohesin chromosome structural proteins promote these large chromosome loops (8, 9).

Along with Igk and TCRα/δ loci, TCRβ can assemble genes through deletional or inversional V rearrangements. TCRβ loci contain ~30 Vβ (TRBV) gene segments upstream and in the same transcriptional orientation as two D-J-Cβclusters (Dβ1-Jβ1-Cβ1, Dβ2-Jβ2-Cβ2), and a single Vβ (TRBV31) downstream in the opposite transcriptional orientation (13). All Dβ-to-Jβ rearrangements occur by deletion of intervening sequences, generating chromosomal DJβ coding joins and extrachromosomal circles with signal joins (14, 15). Upstream Vβs recombine to DJβ complexes via deletion of intervening sequences, and TRBV31 rearranges to DJβ complexes by inversion and chromosomal retention of intervening sequences (14, 15). Although the TCRβ configuration permits upstream Vβs to rearrange via inversion to DJβ2 complexes following TRBV31 rearrangements by inversion to DJβ1 complexes, this scenario has never been reported. To determine whether such two successive inversional Vβ rearrangements occur, we analyzed mice containing Tcrb alleles with a pre-assembled Trbv31-DJCβ1 gene. When this gene is in-frame, Trbv5 evades TCRβ-signaled feedback inhibition and recombines by inversion to the DJCβ2 cluster, creating αβ T cells capable of expressing two distinct TCRβ chains from the same allele. When Trbv31-DJCβ1 is out-of-frame, most upstream Vβs recombine to create Vβ-DJCβ2 genes that promote development of αβ T cells, albeit with preferential selection for inversional Trbv1-DJβ2 rearrangements during TCRβ-signaled thymocyte expansion. Finally, we show normal Tcrb alleles yield αβ T cells that express upstream Vβs in surface αβ TCRs and carry assembled Trbv31-DJCβ1 genes. Our data demonstrate that two successive inversional Vβ-to-DJβ rearrangements on one allele can contribute to the TCRβ repertoire of mature αβ T cells. We discuss the implications of our findings for mechanisms that regulate assembly and selection of TCRβ genes during αβ T cell development.

Materials and Methods

Mice

The V31NT/NT (16), Lat−/− (17), Eβ−/− (18), and wild-type C57BL/6 (Jackson Labs) mice were bred to generate Lat−/−, V31NT/NT:Lat−/−, V31NT/NT, V31NT/Eβ−, and WT/Eβ− mice. To generate V31NTKO mice, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing was conducted in zygotes produced from in vitro fertilization of C57BL/6 eggs with V31NT/NT sperm. The V31NTKO-gRNA (GCCTGGAGTCTTCCGGGACA), which overlaps the V31NT DJβ1 coding join, was generated by MEGAshortscript T7 Transcription Kit (Ambion) and then purified by MEGAclear Transcription Clean-Up Kit (Ambion). The following mix was electoporated into zygotes: 4μM of purified V31NTKO-gRNA, 4μM of Cas9-NLS nuclease (qb3 MacroLab Berkeley), 10μM of ssDNA 5’-ACGGAGAAGCTGCTTCTCAGCCACTCTGGCTTCTACCTCTGTGCCTGGAGTCTTCCGGGAtgaCAGGGCAACCAGGCTCCGCTTTTTGGAGAGGGGACTCGACTCTCTGTTCTAGGTAAACTA-3’ (IDT) that contains a premature stop codon at the coding junction. Mice were screened for incorporation of the stop codon, introduction of other mutations, or deletion of sequences by PCR with primers 5’-AGAGTCGGTGGTGCAACTGAACC-3’ and 5’-TAAAACCTACCAGCGGTCCCAAAG-3’, followed by Sanger sequencing on the PCR products. Founders with mutations (#5 and #8) were mated with Eβ−/− mice and each other to generate the V31NTKO/Eβ− and V31NTKO/NTKO mice. Studies were conducted on mice between 4 and 6 weeks of age. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant institutional and national guidelines and regulations, and approved by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

Thymocytes and splenocytes were stained with antibodies against indicated surface antigens (BD Pharmingen, Biolegend). To analyze the Vβ repertoire and αβ T cell development, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-TCRβ chain and anti-Trbv-specific (Trbv1, Trbv2, Trbv4, Trbv12, Trbv13, Trbv19, or Trbv31) antibodies were used. To analyze DN development stages, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD25, anti-CD44, and anti-lineage/stage markers (TCRβ, B220, CD19, CD11b, CD11c, TCRδ, NK1.1, and Ter119) antibodies were used. Samples were acquired on LSRII Fortessa (BD Pharmingen) and analyzed using the FlowJo software v10 (Tree Star).

Cell Sorting

To isolate DN3 cells, thymocytes were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD25, anti-CD44, and anti-lineage/stage markers (TCRβ, B220, CD19, CD11b, CD11c, TCRδ, NK1.1, Ter119) antibodies. To isolate cells in different stages of αβ TCR selection (A-D)(19), thymocytes were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD69, anti-TCRβ antibodies. To isolate CβhighTrbv31low and CβhighTrbv31high cells, thymocytes were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-TCRβ, and anti-Trbv31 antibodies. To isolate Trbv1+Trbv31−Cβ+ ⍺β T cells, thymocytes were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-TCRβ chain, anti-Trbv31, and anti-Trbv1 antibodies. The cells of interest were isolated using a FACSAria Fusion sorter (BD Biosciences).

Analysis of V(D)J Rearrangements

Genomic DNA was extracted from cells using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen). A quantitative PCR assay to measure Vβ-to-DJβ1.1 and Vβ-to-DJβ2.1 rearrangement levels was designed with a panel of primers specific for each Vβ paired with a probe, FAM or HEX, specific for Jβ1.1 or Jβ2.1, respectively. Rearrangements were measured by TaqMan qPCR with conditions according to the manufacturer’s instructions (IDTDNA) on the ViiA 7 system (Applied Biosystems). PCR analysis of CD19 was used for normalization. Primer and probe sequences are as described previously (20).

Signal Join PCR

Chromosomal signal joins were assessed by PCR. Genomic DNA was extracted from sorted Trbv1+Trbv31-Cβ+ ⍺β T cells using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen). PCRs were conducted on 25ng DNA in a final volume of 25μl containing 10x PCR buffer (Qiagen), 0.2mM dNTPs (GenScript), 0.4μM each primer (IDTDNA), and 1.25 U Taq (Qiagen). PCR primer sequences are V1 3’ RSS-AS: 5’-AAGAAAGCTCAGAAGGGCTTGCA-3’ with Dβ2-S: 5’-GTAGGCACCTGTGGGGAAGAAACT-3’, V31 3’RSS-AS: 5’- AAGAGTAGCCTGGTTTAAGGACGGG-3’ with Dβ1-S: 5’- GAGGAGCAGCTTATCTGGTGGTTT-3’. PCR conditions were 95°C for 5 min; 40 cycles of 92°C for 1 min 30s, 60°C for 2 min 50s, 72°C for 1 min; and 72°C for 5 min.

Analysis of VDJCβ Transcripts

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and the RNEasy kit (Qiagen). cDNA was generated using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems), and used to measure transcript levels by qPCR with conditions according to the manufacturer’s instructions for SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems) on the ViiA 7 system (Applied Biosystems). Trbv5 transcripts were normalized to PCR amplification of Actinb. Primer sequences are V5-S: 5’-AAATGAGACGGTGCCCAGTCGTT-3’, Cβ-R: 5’-CATTCACCCACCAGCTCAG-3’, Actb-S: 5’- GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG-3’, Actb-R: 5’- CCAGTTGGTAACAATGCCATGT-3’

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed in Graphpad Prism 8 using statistical tests indicated in the figure legends. Error bars indicate the mean +/− SEM.

Results

Some upstream Vβ gene segments can rearrange to the DJCβ2 cluster through inversion in the absence of TCRβ-mediated feedback inhibition

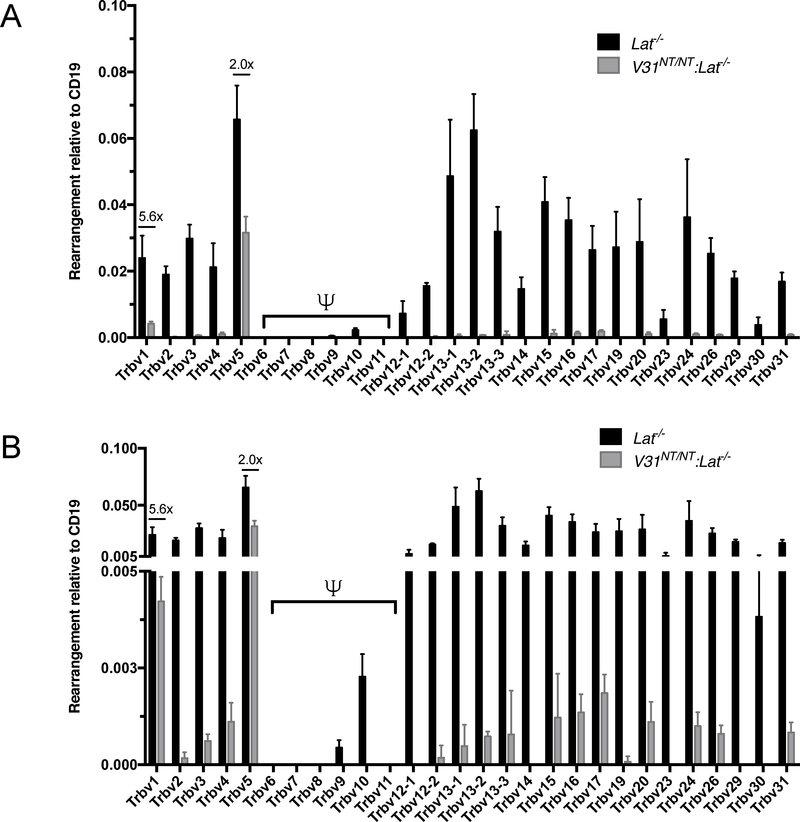

To determine whether upstream Vβs can recombine by inversion to the DJCβ2 cluster, we first used mice carrying a pre-assembled functional Trbv31-DJCβ1 gene (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Mice with this allele were made by somatic cell cloning through nuclear transfer from an αβ T cell (21). We previously showed mice containing the Trbv31-DJCβ1 gene opposite a normal Tcrb allele (V31NT/+ mice) develop αβ T cells that all express Trbv31 in their TCRs (16). Yet, ~1% of these cells expresses an additional Vβ in their TCRs due to recombination of Vβs on the normal allele that precede or escape TCRβ-signaled feedback inhibition from the Trbv31-DJCβ1 gene (16). In mice with the Trbv31-DJCβ1 gene on both alleles (V31NT/NT mice), we did not observe rearrangement and expression of the upstream Vβs assayed (Trbv4, Trbv12, Trbv13, Trbv19)(16). It is possible other upstream Vβs can escape feedback inhibition and recombine with DJβ2 complexes by inversion on V31NT alleles. To test this possibility, we quantified Vβ-to-DJβ2 rearrangements on V31NT and wild-type Tcrb alleles in Lat-deficient thymocytes. The Lat adaptor protein is critical for TCRβ-signaled inhibition of Vβ recombination and development of immature αβ T cells beyond the stage in which TCRβ genes assemble (17). Analyses of Lat-deficient thymocytes allows quantification of Vβ rearrangements in the absence of TCRβ-mediated feedback inhibition and selection of VDJβ rearrangements. TaqMan qPCR assays using Vβ-specific primers with a Jβ2.1 primer/probe combination provides an accurate approach to quantify relative usage of individual Vβs in rearrangements to the DJβ2 cluster (20). We find each upstream Vβ recombines to DJβ2.1 complexes at a distinct level in Lat−/− thymocytes, with Trbv5 and Trbv13.2 rearrangements at the highest levels (Fig. 1A). In contrast, we detect appreciable recombination of only Trbv5 and Trbv1 to DJβ2.1 complexes in V31NT/NT:Lat−/− cells (Fig. 1A). These Trbv5 and Trbv1 rearrangements are ~2-fold and ~6-fold lower, respectively, than in Lat−/− cells (Fig. 1A). Other upstream Vβs recombine to DJβ2.1 complexes in V31NT/NT:Lat−/− cells, but at levels >10-fold lower and barely above background relative to Lat−/− cells (Fig. 1B). The more restricted Vβ usage and lower overall level of Vβ recombination in V31NT/NT:Lat−/− cells indicate that aspects of the V31NT allele, in addition to its TCRβ signaling capacity, inhibit upstream Vβ rearrangements. We detect equivalent levels of Dβ2-to-Jβ2.1 rearrangements in V31NT/NT:Lat−/− and Lat−/− cells (Supplemental Fig. 1B), indicating low levels of Vβ rearrangements on V31NT alleles are not from impaired Dβ-Jβ joining. Our results indicate rearrangements of upstream Vβs to the DJCβ2 cluster by inversion are possible, albeit limited, on alleles with a pre-assembled in-frame Trbv31-DJCβ1 gene.

FIGURE 1.

Quantification of upstream Vβ rearrangements by inversion on V31NT alleles. (A) Graph showing TaqMan qPCR quantification of rearrangements of each Vβ segment to DJβ2.1 complexes performed on DNA from DN thymocytes of Lat−/− or V31NT/NT:Lat−/− mice. Signals from each assay were normalized to values from an assay for the invariant CD19 gene. Shown are the average levels from three independent DN cell preparations (n = 3, ±SEM). Pseudogenes are denoted by the ψ symbol. (B) The same data from A depicted on a graph with an expanded y-axis to reveal low levels of recombination for some Vβ segments.

Inversional rearrangements of upstream Vβ segments on alleles with a pre-assembled in-frame Trbv31-DJCβ1 gene have potential to create αβ T cells expressing two distinct TCRβ chains within surface TCRs

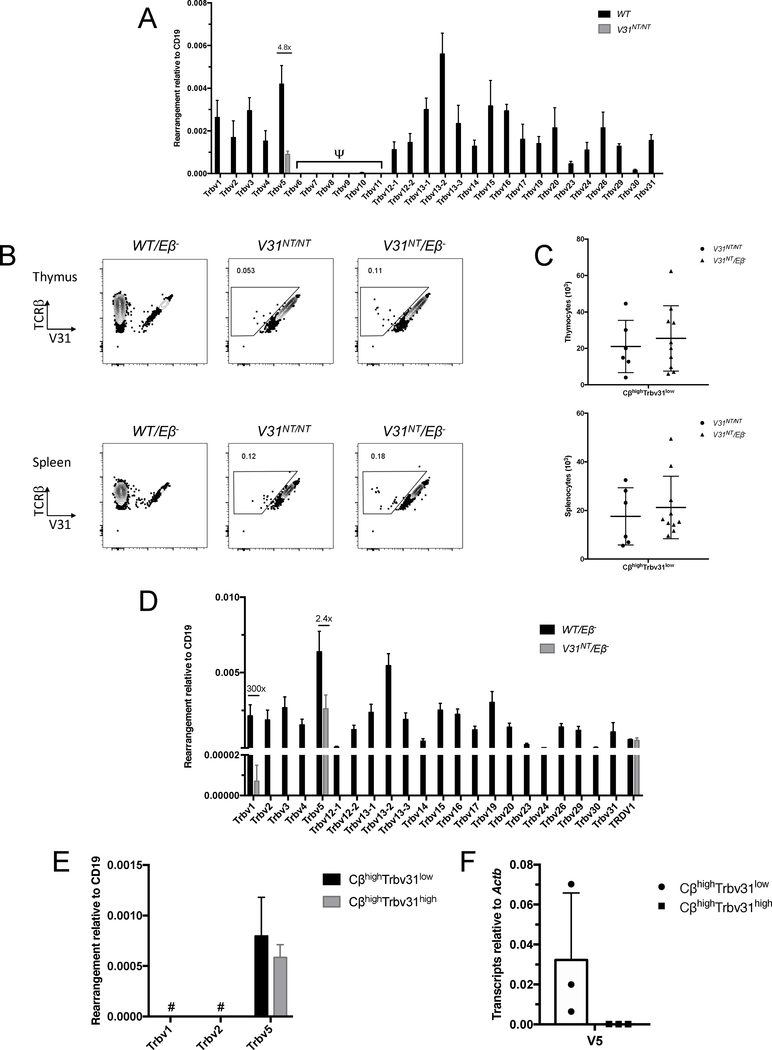

Our findings open the possibility for development of αβ T cells that express Trbv31+ and Trbv5+ or Trvb1+ TCRβ proteins from the same Tcrb allele. To test this, we first used TaqMan qPCR to quantify upstream Vβ rearrangements to DJβ2.1 complexes in thymocytes and splenic αβ T cells of V31NT/NT and wild-type mice. In V31NT/NT cells, we detected recombination of only Trbv5, with levels ~5-fold lower than in wild-type cells (Fig. 2A; unpublished observations). TCRβ loci contain a single enhancer (Eβ) between Cβ2 and TRBV31 that is essential for all steps of TCRβ recombination and presumably expression of assembled TCRβ genes (18, 22). TheTrbv5 inversional rearrangements on V31NT alleles result in Trbv5-DJCβ2 genes 7 kb upstream of Eβ and the Trbv31-DJCβ1 gene 500 kb downstream of Eβ (Supplemental Fig. 2). It is possible these alleles produce T cells that express Trbv5+, Trbv31+, or both types of TCRβ chains within αβ TCRs. We cannot detect Trbv5+ TCRβ proteins by flow cytometry due to the lack of an anti-Trbv5 antibody. Nevertheless, flow cytometry with anti-Cβ and anti-Trbv31 antibodies reveals small numbers of CβhighTrbv31low cells in V31NT/NT mice (Fig. 2B, C). We reasoned the CβhighTrbv31low cells may be cells expressing both Trbv31+ and Trbv5+ TCRβ chains at lower than normal levels within surface αβ TCRs. If so, the cells could express Trbv5+ and Trbv31+ TCRβ chains from Trbv5-rearranged alleles or Trbv5+ TCRβ chains from these alleles and Trbv31+ TCRβ chains from Trbv5-unrearranged alleles. To determine if both Trbv5+ and Trbv31+ TCRβ chains can be expressed from a Trbv5-rearranged allele, we generated mice carrying the V31NT allele opposite a Tcrb allele inactivated by Eβ deletion. These V31NT/Eβ− mice have small numbers of CβhighTrbv31low thymocytes and splenic αβ T cells (Fig. 2B, C). We quantified Vβ-to-DJβ2.1 rearrangements in V31NT/Eβ− thymocytes and splenic αβ T cells, observing them for only Trbv5 or Trbv1 (Fig. 2D; unpublished observations). As compared to WT/Eβ− cells, Trbv5 rearrangements are 2.4-fold lower in V31NT/Eβ− cells, while Trbv1 rearrangements are 300-fold lower and barely above negative controls (Fig. 2D; unpublished observations). This low level of Trbv1 recombination does not produce Trbv1+ αβ T cells that are detectable by flow cytometry above the high background staining of the anti-Trbv1 antibody (unpublished observations). To determine whether Trbv5 rearrangements are expressed, we conducted TaqMan qPCR and qRT-PCR to assay Trbv5-DJβ2.1 recombination and Trbv5-DJCβ2 mRNA in CβhighTrbv31low or CβhighTrbv31high αβ T cells sorted from V31NT/Eβ− mice. We found rearrangements in both cell populations, but transcripts only in CβhighTrbv31low cells (Fig. 2E, F), indicating two distinct Tcrb genes can be transcribed from alleles with two inversional Vβ rearrangements. From these data, we conclude that inversional Trbv5-to-DJβ2 rearrangements on V31NT alleles have the potential to produce αβ T cells expressing both Trbv5+ and Trbv31+ αβ TCRs.

FIGURE 2.

Inversional Vβ rearrangements on V31NT alleles are expressed in αβ T cells. (A) Graph showing TaqMan qPCR quantification of rearrangements of each Vβ segment to DJβ2.1 complexes performed on DNA from total thymocytes of wild-type (WT) or V31NT/NT mice. Signals from each assay were normalized to values from an assay for the CD19 gene. Shown are the average levels from three independent DN cell preparations (n = 3, ±SEM). Pseudogenes are denoted by the ψ symbol. (B) Representative flow cytometry of thymocytes and splenocytes of WT/Eβ−, V31NT/NT, or V31NT/Eβ− mice using anti-Cβ and anti-Trbv31 antibodies. The gates depict CβhighTrbv31low cells with their percentage of Cβhigh cells indicated. (C) Graphs showing numbers of CβhighTrbv31low thymocytes and splenocytes in each of six V31NT/NT and ten V31NT/Eβ− mice. (D) Graph showing TaqMan qPCR quantification of rearrangements of each Vβ segment to DJβ2.1 complexes performed on DNA from total thymocytes of WT/Eβ− or V31NT/Eβ− mice. Signals from each assay were normalized to values from an assay for the invariant CD19 gene. Shown are the average levels from three independent DN cell preparations (n = 3, ±SEM). (E-F) Graphs showing TaqMan qPCR quantification of rearrangements of Trbv1, Trbv2, or Trbv5 to DJβ2.1 complexes performed on DNA (E) or Trbv5-DJCβ2 transcripts (F) from CβhighTrbv31low or CβhighTrbv31high thymocytes of V31NT/Eβ− mice. Signals were normalized to values from an assay for the invariant CD19 gene (E) or Actin b transcripts (F). Shown are the average levels from three independent preparations (n = 3, ±SEM). #, indicates no amplification.

Inversional rearrangements of upstream Vβs on alleles with a pre-assembled out-of-frame Trbv31-DJCβ1 gene drive development of αβ T cells

Our observations raise the additional possibility that Trbv5 inversional rearrangements occur on alleles that assemble out-of-frame Trbv31-DJCβ1 genes and then drive αβ T cell development. To explore this, we used CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in V31NT/+ zygotes to create two lines of mice with inactivation of the pre-assembled Trbv31-DJCβ1 gene. One line (#5) has deletion of Dβ1Jβ1.5 nucleotides, while the other (#8) has a single nucleotide insertion that places the gene out-of-frame (Supplemental Fig. 3A). We first studied mice with each of these alleles opposite an inactivated Tcrb allele (V31NTKO/Eβ− mice), comparing them to WT/Eβ− mice. For subsequent experiments, we included wild-type and V31NTKO/NTKO mice. We observed identical phenotypes for mice carrying the V31NTKO #5 or #8 allele (unpublished observations).

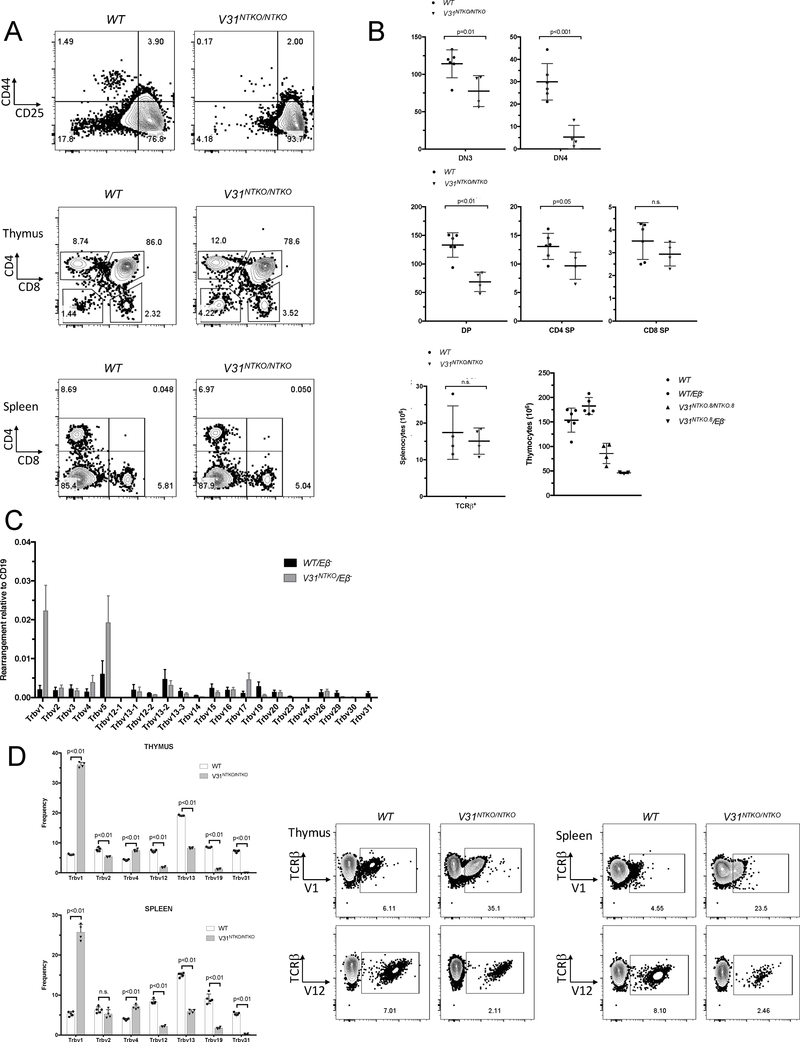

Flow cytometry analyses confirmed lack of TCRβ protein from non-functional Trbv31-DJCβ1 genes in V31NTKO/Eβ− mice (Supplemental Fig. 3B). The assembly and expression of in-frame Tcrb genes in CD44−CD25+ stage 3 DN thymocytes is required for differentiation of CD44−CD25− stage 4 DN thymocytes, which develop into DP thymocytes while proliferating and expanding (5). As compared to wild-type mice, V31NTKO/NTKO mice contain ~6-fold and ~2-fold fewer DN4 and DP thymocytes, respectively (Fig. 3A, B; unpublished observations). TaqMan qPCR and flow cytometry revealed that most upstream Vβ rearrange to DJβ2 complexes by inversion and are expressed in TCRs on thymocytes and αβ T cells of V31NTKO/Eβ− and V31NTKO/NTKO mice (Fig. 3C, D; unpublished observations). However, Trvb1 and Trbv5 are over-represented compared to the repertoire of WT/Eβ− and wild-type mice (Fig. 3C, D; unpublished observations). These data indicate that most Vβs recombine to DJβ2 complexes by inversion on alleles carrying an out-of-frame Trbv31-DJCβ1 gene, and resultant Vβ-DJCβ2 genes drive αβ T cell development.

FIGURE 3.

Most upstream Vβs rearrange by inversion and drive αβ T cell development after out-of-frame Trbv31 rearrangement. (A) Representative flow cytometry of thymocytes or splenocytes of WT or V31NTKO/NTKO (#8) mice using anti-CD44 and anti-CD25 or anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies. The gates show DN1, DN2, DN3, or DN4 thymocytes (top panel), DN, DP, CD4+ SP, or CD8+ SP thymocytes (middle panel), or CD4+ or CD8+ splenic αβ T cells with percentages of cells in gate from total cells indicated. (B) Graphs showing numbers of each of these cells in the six wildtype and four V31NTKO/NTKO (#8) mice analyzed. (C) Graph showing TaqMan qPCR quantification of rearrangements of each Vβ segment to DJβ2.1 complexes performed on DNA from total thymocytes of WT/Eβ− or V31NTKO/Eβ− (#5) mice. Signals from each assay were normalized to values from an assay for the invariant CD19 gene. Shown are the average levels from three independent DN cell preparations (n = 3, ±SEM). (D) Representative flow cytometry of thymocytes or splenocytes of WT or V31NTKO/NTKO (#8) mice using anti-Cβ with anti-Trbv1 or anti-Trv12 antibodies. The gates depict Cβ+Trbv1+ or Cβ+Trbv12+ cells with percentages of cells in gate from total cells indicated. Graphs showing percentages of thymocytes or splenic αβ T cells expressing the indicated Vβs in five WT and four V31NTKO/NTKO (#8) mice. (A-D) Except for the TaqMan qPCR analysis of the Vβ repertoire (C), these experiments were performed on both lines of V31NTKO mice and revealed equivalent phenotypes between each line.

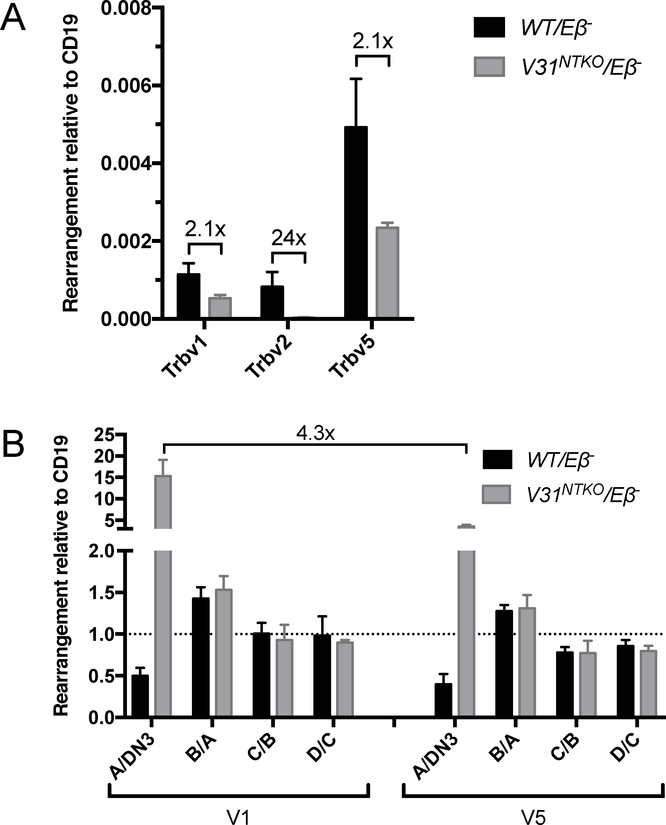

The lower than normal numbers of DN4 and DP thymocytes and abnormal Vβ utilization in total thymocytes and splenic αβ T cells of V31NTKO/Eβ− and V31NTKO/NTKO mice could arise from altered assembly and/or selection of Tcrb genes. To quantify levels and relative utilization of Vβs within the un-selected Tcrb repertoire, we conducted TaqMan qPCR on sorted DN3 thymocytes of V31NTKO/Eβ− and WT/Eβ− mice. We detected lower levels of rearrangements for each Vβ tested (Trbv1, Trbv2, and Trbv5) in V31NTKO/Eβ− cells relative to WT/Eβ− cells (Fig. 4A). This indicates decreased Vβ recombination contributes to reduced thymocyte cellularity in V31NTKO/Eβ− mice. Notably, rearrangements of Trbv1 versus Trbv5 are higher in total thymocytes compared to DN3 thymocytes of V31NTKO/Eβ− but not WT/Eβ− mice (compare Fig. 3C and 4A), indicating biased selection for inversional Trbv1-DJβ2.1 rearrangements. The relative representation of individual Vβs in Tcrb rearrangements and TCRβ proteins is constant between DN and DP thymocytes, but can change during selection of αβ TCRs expressed on DP cells depending on DJβ complex sequence (23, 24). To identify when increased selection of inversional Trbv1 rearrangements occurs, we quantified Trbv1 or Trbv5 recombination to DJβ2.1 complexes in; A, pre-selection TCRβ−CD69− DP thymocytes; B, actively-selecting TCRβ−CD69+ DP thymocytes; C, post-selection TCRβ+CD69+ DP thymocytes; and D, TCRβ+CD69− SP thymocytes sorted from V31NTKO/Eβ− or WT/Eβ− mice. We calculated ratios of levels between DN3 and DP cells and between subsequent stages of thymocyte development. This analysis shows similar selection of Trvb1 and Trbv5 rearrangements on wild-type alleles throughout development (Fig. 4B). In marked contrast, Trvb1-to-DJβ2.1 rearrangements on V31NTKO alleles are preferentially selected for ~3-fold more during DN-to-DP development (Fig. 4B). The most likely basis for this difference is more substantial expression of Trbv1-DJCβ genes assembled from inversional versus deletional rearrangements due to reasons discussed below.

FIGURE 4.

Quantification of recombination and selection of inversional Vβ rearrangements. (A) Graph showing TaqMan qPCR quantification of rearrangements of Trbv1, Trbv2, or Trbv5 to DJβ2.1 complexes performed on DNA from DN3 thymocytes of WT/Eβ− or V31NTKO/Eβ− mice. Signals were normalized to values from an assay for the invariant CD19 gene. (B) Graph showing ratios of TaqMan qPCR quantification of rearrangements of Trbv1 or Trbv5 to DJβ2.1 complexes in WT/Eβ− or V31NTKO/Eβ− mice between thymocytes of the indicated developmental stages: DN3; A, pre-selection DP; B, actively-selecting DP; C, post-selection DP; and D, SP thymocytes. The dashed lined depicts a value of 1 indicative of no selection for or against Trbv1+ or Trbv5+ cells. (A-B) These data are from the V31NTKO #8 line.

Rearrangements of upstream Vβ segments to the DJCβ2 cluster through inversion can occur on normal Tcrb alleles and contribute to the αβ TCR repertoire

Finally, we sought to determine if upstream Vβ rearrangements by inversion to DJβ2 complexes can occur on normal Tcrb alleles. We used TaqMan qPCR to quantify Trbv31 rearrangements in Trbv1+Trbv31−Cβ+ αβ T cells sort-purified from WT/Eβ− mice (Fig. 5A). We reasoned a fraction of these cells would arise from in-frame Trbv1 rearrangements to DJβ2 complexes by inversion after out-of-frame Trbv31-to-DJβ1 rearrangements. Consistent with this premise, we found low, but above background, levels of Trbv31-DJβ1.1 rearrangements in Trbv1+Trbv31−Cβ+ cells (Fig. 5B). Because inversional rearrangements leave signal joins within loci, we also used PCR to assay for such joins between the Trbv1 and 5’Dβ2 RSSs or Trbv31 and 5’Dβ1 RSSs. We detected Trbv1/5’Dβ2 and Trbv31/5’Dβ1 signal joins in Cβ+Trbv1+ cells, but only Trbv31/5’Dβ1 signal joins in sorted Cβ+Trbv1− cells (Fig. 5C). Thus, we conclude two successive inversional Vβ-to-DJβ rearrangements on a single normal Tcrb allele can contribute to create the TCRβ repertoire expressed within surface αβ TCRs.

FIGURE 5.

Identification of two successive inversional Vβ rearrangements on a single allele in normal αβ T cells. (A) Flow cytometry sorting of CβhighTrbv1high WT/Eβ− thymocytes using anti-Cβ and anti-Trbv1 antibodies. Shown are cells before or after sorting for CβhighTrbv1high cells using the depicted gate. (B) Graph showing TaqMan qPCR quantification of Trbv1-to-DJβ2.1 or Trbv31-to-DJβ1.1 rearrangements performed on DNA from three independent populations of sort-purified CβhighTrbv1high cells. Signals were normalized to values from an assay for the invariant CD19 gene. (C) Images from ethidium bromide stained agarose gels showing PCR amplification of signal joins between the Trbv31 and 5’Dβ1 RSSs or between the Trbv1 and 5’Dβ2 RSSa performed on DNA from three independent sorted populations of Cβ+Trbv1+ or Cβ+Trbv1− cells. The PCR amplification of Cβ2 exons as a control for DNA content is also shown.

Discussion

Our finding that upstream Vβ segments can rearrange by inversion to DJβ2 complexes on alleles with an assembled Trbv31-DJCβ1 gene provide new insights into mechanisms that direct Tcrb recombination and expression. The genomic organization of Tcrb allows two possible V-to-DJ rearrangements on each allele. Our data herein indicate that, when the first Vβ rearrangement is an inversion between Trbv31 and a DJβ1 complex, upstream Vβs then can recombine by inversion to a DJβ2 complex. As evident from our analysis of V31NTKO/Eβ− cells, if the initial Trbv31-DJβ1 coding join is out-of-frame, an upstream Vβ segment can recombine with the DJCβ2 cluster to provide another opportunity to assemble a functional Tcrb gene. However, if the Trbv31-DJβ1 coding join is assembled in-frame, resultant Trbv31+ TCRβ proteins likely would signal feedback inhibition of upstream Vβ rearrangements to DJβ2 complexes on the same allele. In contradiction to this supposition, our analysis of V31NT/Eβ− cells shows that Trbv5 can recombine by inversion to the DJβ2 cluster in a small fraction of cells, despite the presence of an in-frame Trbv31-DJβ1 join on the same allele. These Trbv5 rearrangements likely occur before the pre-assembled Trbv31-DJCβ1 gene enforces TCRβ-signaled feedback inhibition. In the normal setting of mice inheriting each Tcrb allele in the un-rearranged configuration, signals from RAG DSBs during Trbv31-to-DJβ1 recombination likely would block inversional Trbv5 rearrangements on the same allele before feedback signals resulting from an in-frame Trbv31-DJCβ1 gene halt further Vβ rearrangements. The development and application of an anti-Trbv5 antibody would determine if this is the case or if some normal αβ T cells expresses Trbv5+ and Trbv31+ TCRβ chains from successive inversional Vβ rearrangements on one allele. Finally, our detection of Trbv5-DJCβ2 transcripts in CβhighTrbv31low αβ T cells of V31NT/Eβ− mice is notable considering that Trbv5-to-DJβ2 inversional rearrangements re-position Eβ ~500 kb from the assembled Trbv31-DJCβ1 gene. This indicates the Trbv31 promoter can either drive Trbv31-DJCβ1 transcription independent of Eβ or functionally interact with Eβ through long-range chromosome looping. The former scenario raises the possibility that Eβ is essential for Vβ rearrangements, but not for expression of assembled TCRβ genes. The generation and analysis of mice with Eβ deleted on the V31NT allele would reveal the role for Eβ in driving expression of an assembled Trbv31-DJCβ1 gene.

The decreased levels and altered usage and selection of upstream Vβ-to-DJβ2 rearrangements by inversion versus deletion have implications for mechanisms that promote assembly and expression of diverse Tcrb genes. The efficient and broad utilization of V segments in rearrangements over large genomic distances is fueled by chromosome looping, which is dependent on CTCF/Cohesin and in some loci enhancers (8). On each chromosome, CTCF and Cohesin establish loops by extrusion of DNA between CTCF-binding elements (CBEs), with preference for convergently-oriented CBEs (25). These loops can regulate gene expression by increasing enhancer and promoter contacts in the same loop and reducing contacts between enhancers and promoters in different loops (25). TCRβ, TCRα/δ, IgH, and Igκ loci all have many CBEs among V segments that are in convergent orientation with CBEs flanking downstream (D)J segments and enhancers (26). The deletion or inversion of CBEs has shown their position- and orientation-dependent functions in forming loops and increasing interactions and rearrangements between V and (D)J segments (27–36). Another line of work has demonstrated that loop extrusion between CBEs directs deletional V(D)J recombination by empowering RAG bound at D-J RSSs to scan along the DNA and thereby capture convergent RSSs for synapsis, cleavage, and joining (27, 37–39). This mechanism does not preclude diffusion-based synapsis of RSSs placed in proximity by looping. Other than Trbv31-DJβ1 mutations, the only differences between germline V31NTKO and wild-type alleles are inversion of a 24 kb sequence that alters the locations and orientations of Dβ2-Jβ2 segments, Cβ2, Eβ, and a 3’CBE (Fig S2). On wild-type alleles, deletion of Eβ has no effect on interactions between Vβ and Dβ-Jβ segments, while deletion of two CBEs just upstream of Dβ1 decreases interactions and rearrangements of 5’Vβs with Dβ-Jβ segments (30). One explanation for restricted usage and low levels of upstream Vβ rearrangements on V31NTKO alleles is re-positioning and inverting the 3’CBE alters and decreases looping, which reduces diffusion-based synapsis between Vβ and 5’Dβ2 RSSs. Another reason could be inversion of the 5’Dβ2 RSS halts RAG scanning toward upstream Vβs to preclude scanning-based synapsis between the RC and Vβ RSSs. The most likely explanation for preferential selection of Trbv1-DJβ2 genes on V31NTKO but not wild-type alleles is their higher expression during DN-to-DP thymocyte development. Although inversional and deletional Trbv1 rearrangements place Trbv1-DJβ2 genes at an identical distance from Eβ and its 3’CBE, inversions retain 650 kb normally lost by deletions and place three additional CBEs near Eβ (Fig. S2). It is possible these CBEs loop with CBEs upstream of Trbv1 to drive robust transcription of Trbv1-DJCβ2 genes assembled from inversional rearrangements. Regardless of underlying mechanisms, our findings illuminate a role for targeting Vβ rearrangements and anchoring assembled Tcrb genes near the RC-end of the locus in shaping the primary Vβ repertoire. The need to uniformly control selection of specific V(D)J rearrangements might explain evolution of antigen receptor locus organizations that maintain C region exons at one end during V(D)J recombination.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Two successive inversional V-to-DJ rearrangements can occur on one Tcrb allele.

Both Vβ usage and Vβ selection are abnormal for inversional rearrangements.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 AI 130231 (C.H. Bassing).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Bassing CH, Swat W, Alt FW, The mechanism and regulation of chromosomal V(D)J recombination. Cell 109 Suppl, S45–55 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schatz DG, Swanson PC, V(D)J recombination: mechanisms of initiation. Annu Rev Genet 45, 167–202 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhandoola A, von Boehmer H, Petrie HT, Zuniga-Pflucker JC, Commitment and developmental potential of extrathymic and intrathymic T cell precursors: plenty to choose from. Immunity 26, 678–689 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajewsky K, Clonal selection and learning in the antibody system. Nature 381, 751–758 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Boehmer H, Melchers F, Checkpoints in lymphocyte development and autoimmune disease. Nat Immunol 11, 14–20 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brady BL, Steinel NC, Bassing CH, Antigen receptor allelic exclusion: an update and reappraisal. J Immunol 185, 3801–3808 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mostoslavsky R, Alt FW, Rajewsky K, The lingering enigma of the allelic exclusion mechanism. Cell 118, 539–544 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenter AL, Feeney AJ, New insights emerge as antibody repertoire diversification meets chromosome conformation. F1000Res 8, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shih HY, Krangel MS, Chromatin architecture, CCCTC-binding factor, and V(D)J recombination: managing long-distance relationships at antigen receptor loci. J Immunol 190, 4915–4921 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ji Y, Little AJ, Banerjee JK, Hao B, Oltz EM, Krangel MS, Schatz DG, Promoters, enhancers, and transcription target RAG1 binding during V(D)J recombination. J Exp Med 207, 2809–2816 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji Y, Resch W, Corbett E, Yamane A, Casellas R, Schatz DG, The in vivo pattern of binding of RAG1 and RAG2 to antigen receptor loci. Cell 141, 419–431 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryu CJ, Haines BB, Lee HR, Kang YH, Draganov DD, Lee M, Whitehurst CE, Hong HJ, Chen J, The T-cell receptor beta variable gene promoter is required for efficient V beta rearrangement but not allelic exclusion. Mol Cell Biol 24, 7015–7023 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glusman G, Rowen L, Lee I, Boysen C, Roach JC, Smit AF, Wang K, Koop BF, Hood L, Comparative genomics of the human and mouse T cell receptor loci. Immunity 15, 337–349 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Majumder K, Bassing CH, Oltz EM, Regulation of Tcrb Gene Assembly by Genetic, Epigenetic, and Topological Mechanisms. Adv Immunol 128, 273–306 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson AM, Krangel MS, Turning T-cell receptor beta recombination on and off: more questions than answers. Immunol Rev 209, 129–141 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinel NC, Brady BL, Carpenter AC, Yang-Iott KS, Bassing CH, Posttranscriptional silencing of VbetaDJbetaCbeta genes contributes to TCRbeta allelic exclusion in mammalian lymphocytes. J Immunol 185, 1055–1062 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang W, Sommers CL, Burshtyn DN, Stebbins CC, DeJarnette JB, Trible RP, Grinberg A, Tsay HC, Jacobs HM, Kessler CM, Long EO, Love PE, Samelson LE, Essential role of LAT in T cell development. Immunity 10, 323–332 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bouvier G, Watrin F, Naspetti M, Verthuy C, Naquet P, Ferrier P, Deletion of the mouse T-cell receptor beta gene enhancer blocks alphabeta T-cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93, 7877–7881 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamashita I, Nagata T, Tada T, Nakayama T, CD69 cell surface expression identifies developing thymocytes which audition for T cell antigen receptor-mediated positive selection. Int Immunol 5, 1139–1150 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gopalakrishnan S, Majumder K, Predeus A, Huang Y, Koues OI, Verma-Gaur J, Loguercio S, Su AI, Feeney AJ, Artyomov MN, Oltz EM, Unifying model for molecular determinants of the preselection Vbeta repertoire. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, E3206–3215 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hochedlinger K, Jaenisch R, Monoclonal mice generated by nuclear transfer from mature B and T donor cells. Nature 415, 1035–1038 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bories JC, Demengeot J, Davidson L, Alt FW, Gene-targeted deletion and replacement mutations of the T-cell receptor beta-chain enhancer: the role of enhancer elements in controlling V(D)J recombination accessibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93, 7871–7876 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson A, Marechal C, MacDonald HR, Biased V beta usage in immature thymocytes is independent of DJ beta proximity and pT alpha pairing. J Immunol 166, 51–57 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carpenter AC, Yang-Iott KS, Chao LH, Nuskey B, Whitlow S, Alt FW, Bassing CH, Assembled DJ beta complexes influence TCR beta chain selection and peripheral V beta repertoire. J Immunol 182, 5586–5595 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rowley MJ, Corces VG, Organizational principles of 3D genome architecture. Nat Rev Genet 19, 789–800 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loguercio S, Barajas-Mora EM, Shih HY, Krangel MS, Feeney AJ, Variable Extent of Lineage-Specificity and Developmental Stage-Specificity of Cohesin and CCCTC-Binding Factor Binding Within the Immunoglobulin and T Cell Receptor Loci. Front Immunol 9, 425 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jain S, Ba Z, Zhang Y, Dai HQ, Alt FW, CTCF-Binding Elements Mediate Accessibility of RAG Substrates During Chromatin Scanning. Cell 174, 102–116 e114 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin SG, Guo C, Su A, Zhang Y, Alt FW, CTCF-binding elements 1 and 2 in the Igh intergenic control region cooperatively regulate V(D)J recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 1815–1820 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo C, Yoon HS, Franklin A, Jain S, Ebert A, Cheng HL, Hansen E, Despo O, Bossen C, Vettermann C, Bates JG, Richards N, Myers D, Patel H, Gallagher M, Schlissel MS, Murre C, Busslinger M, Giallourakis CC, Alt FW, CTCF-binding elements mediate control of V(D)J recombination. Nature 477, 424–430 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Majumder K, Koues OI, Chan EA, Kyle KE, Horowitz JE, Yang-Iott K, Bassing CH, Taniuchi I, Krangel MS, Oltz EM, Lineage-specific compaction of Tcrb requires a chromatin barrier to protect the function of a long-range tethering element. J Exp Med 212, 107–120 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen L, Carico Z, Shih HY, Krangel MS, A discrete chromatin loop in the mouse Tcra-Tcrd locus shapes the TCRdelta and TCRalpha repertoires. Nat Immunol 16, 1085–1093 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleiman E, Xu J, Feeney AJ, Cutting Edge: Proper Orientation of CTCF Sites in Cer Is Required for Normal Jkappa-Distal and Jkappa-Proximal Vkappa Gene Usage. J Immunol 201, 1633–1638 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Volpi SA, Verma-Gaur J, Hassan R, Ju Z, Roa S, Chatterjee S, Werling U, Hou H Jr., Will B, Steidl U, Scharff M, Edelman W, Feeney AJ, Birshtein BK, Germline deletion of Igh 3’ regulatory region elements hs 5, 6, 7 (hs5–7) affects B cell-specific regulation, rearrangement, and insulation of the Igh locus. J Immunol 188, 2556–2566 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiang Y, Zhou X, Hewitt SL, Skok JA, Garrard WT, A multifunctional element in the mouse Igkappa locus that specifies repertoire and Ig loci subnuclear location. J Immunol 186, 5356–5366 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiang Y, Park SK, Garrard WT, A major deletion in the Vkappa-Jkappa intervening region results in hyperelevated transcription of proximal Vkappa genes and a severely restricted repertoire. J Immunol 193, 3746–3754 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiang Y, Park SK, Garrard WT, Vkappa gene repertoire and locus contraction are specified by critical DNase I hypersensitive sites within the Vkappa-Jkappa intervening region. J Immunol 190, 1819–1826 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Zhang X, Ba Z, Liang Z, Dring EW, Hu H, Lou J, Kyritsis N, Zurita J, Shamim MS, Presser Aiden A, Lieberman Aiden E, Alt FW, The fundamental role of chromatin loop extrusion in physiological V(D)J recombination. Nature 573, 600–604 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao L, Frock RL, Du Z, Hu J, Chen L, Krangel MS, Alt FW, Orientation-specific RAG activity in chromosomal loop domains contributes to Tcrd V(D)J recombination during T cell development. J Exp Med 213, 1921–1936 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu J, Zhang Y, Zhao L, Frock RL, Du Z, Meyers RM, Meng FL, Schatz DG, Alt FW, Chromosomal Loop Domains Direct the Recombination of Antigen Receptor Genes. Cell 163, 947–959 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.