Abstract

Objective:

We examined depression and anxiety symptom trajectories in Mexican-origin youth (N=674), and tested longitudinal associations with acculturation dimensions.

Method:

We used eight waves of data from the California Families Project, collected annually from 5th (Mage=10.86, SD=0.51) to 12th (Mage=16.79, SD=0.50) grade. Major Depression (MD) and Generalized Anxiety (GAD) symptoms were assessed by structured psychiatric interview. Cultural measures, selected based on theory and empirical evidence, included English/Spanish use, familism, traditional gender role (TGR) attitudes and ethnic pride. Symptom trajectories were modeled using latent growth analyses, and parallel process growth models examined covariation between internalizing and acculturation trajectories. Models adjusted for child sex, nativity, mother’s education, and family income.

Results:

MD symptoms decreased across adolescence on average, with steeper decreases among boys and children born in Mexico. GAD symptoms also decreased on average, with higher mean levels among girls. Age 10 Spanish use, familism, and ethnic pride was inversely related to age 10 MD symptoms. Steeper increases in Spanish use, familism, and ethnic pride predicted decreasing MD. Higher age 10 MD predicted increasing Spanish use and decreasing English use. Greater age 10 TGR attitudes predicted higher age 10 GAD, but steeper declines in GAD and MD. Increasing ethnic pride slopes predicted decreasing GAD.

Conclusions:

Greater childhood TGR attitudes, and the maintenance of Spanish use, familism and ethnic pride into adolescence, were associated with more optimal trajectories of MD and GAD symptoms. Interventions for Mexican-origin youth internalizing problems should encourage the retention of heritage culture strengths, including familism and ethnic pride.

Keywords: depression, anxiety, adolescent, Latino, longitudinal trajectories

Depression and anxiety, often referred to as internalizing problems, are among the most prevalent psychological disorders for children (Merikangas et al., 2010). Late childhood and adolescence comprise a high-risk period for the emergence and progression of internalizing problems, especially among girls (Hankin, 2009). The early onset of internalizing problems has a large societal cost and burden on youth well-being and later adjustment (Albano, Chorpita, & Barlow, 2003; Copeland, Shanahan, Costello, & Angold, 2009; Glied & Pine, 2002). Latino youth are a rapidly growing segment of the population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017), and Latino adolescents, particularly girls, experience disparately high rates of anxiety and depression symptoms, and elevated risk for mood disorders (Anderson & Mayes, 2010; Merikangas et al., 2010). Specifically, Latina girls report higher depression symptoms compared to White, Black and other racial/ethnic minority girls, and Latino children in general report higher levels of worry and somatic symptoms compared to White children (McLaughlin, Hilt & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2007; Piña & Silverman, 2004). National data have also shown that Latina girls experience significantly higher rates of depressed mood in the past year (46.8%) compared to White girls (38.2%; Kann et al., 2018), and that the odds of being diagnosed with a mood disorder are 1.4 times greater for Latino children compared to White children (Merikangas et al., 2010). Greater exposure to environmental stressors such as discrimination, neighborhood risks, and lower socioeconomic status may help to explain disparately high levels of internalizing psychopathology among Latino youth (Behnke, Plunkett, Sands, & Bámaca-Colbert, 2011; Umaña Taylor & Updegraff, 2007). Our primary attention is on the unique cultural factors that Latino youth experience, which also have ramifications for mental health (Gonzales, Jensen, Montaño, & Wynne, 2015). We focus on Mexican-origin youth who are 69% of the Latino youth population (Patten, 2016). Heightened risk for internalizing problems and the growing Mexican-origin youth population underscore the need to understand internalizing trajectories in this group.

Although adolescence is a period of higher risk for internalizing symptom development, most youths do not exhibit clinical levels of depression or anxiety. Understanding the variability in internalizing symptom development is of key importance to better understand normative and problematic trajectories (García Coll, Akerman, & Cicchetti, 2000). In this regard, we know considerably less about the variation in internalizing symptom development among Latino children relative to White youth. Moreover, there is little research evaluating whether internalizing trajectories are related to the dynamic changes in cultural identity experienced by Mexican-origin youth, even though these may be entwined developmental processes. Understanding the development of internalizing symptoms in cultural context is important to inform culturally-tailored interventions with this growing demographic subgroup. We focus on symptoms within a dimensional framework, rather than disorder status, to better understand the development of psychopathology (Hudziak, Achenbach, Altoff & Pine, 2007).

Developmental Trajectories of Internalizing Symptoms

A growing body of longitudinal research has investigated trajectories of children’s internalizing symptoms, though most of this literature has focused on White “majority” samples. One strategy for modeling internalizing symptom development is the use of latent growth or multilevel modeling, which models average levels and change over time (fixed effects), and variability around those averages (random effects). These studies appear to consistently indicate that anxiety tends to decrease on average across adolescence (e.g., Burstein, Ginsburg, Petras, & Ialongo, 2010; McLaughlin & King, 2015). Depression trajectories are more variable across studies, with some studies showing mean-level declines (Burstein et al., 2010), and others showing no change (McLaughlin & King, 2015), or increases across adolescence (Ge, Natsuaki, & Conger, 2006), particularly among girls (Hankin, 2009). Several prior studies have examined internalizing trajectories in Latino youth using latent growth curve or multilevel modeling. These studies have generally found that internalizing symptoms decrease on average across adolescence among Mexican-origin, Puerto Rican, and other Latino subgroups, typically assessed using parent- or self-report scales, such as the Achenbach System Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and Youth Self Report (Sirin et al., 2015; Smokowski, Rose, & Bacallo, 2010), and in one case using the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (DISC-IV; Shaffer, Prudence, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000)(Ramos-Olazagasti et al., 2013). Alternately, other research with Mexican-origin youth shows that depressive symptoms decline across adolescence for boys, but increase for girls (Zeiders, Roosa, Knight, & Gonzales, 2013). Although most prior studies show an average decline in symptoms over time, it is important to note that studies also indicate significant variability in initial symptom levels and change over time.

Other studies on child internalizing trajectories have used growth mixture modeling or latent class growth modeling to model heterogeneity in symptom development. These strategies model variability in symptom trajectories over time as discrete latent sub-populations or “classes”, which implies qualitative differences between classes. Most growth mixture model studies examining internalizing symptoms have typically found three to four latent trajectory groups for anxiety and depression symptoms. The majority of children tend to be clustered in a stable low or no symptom class, with much smaller subgroups showing increases or decreases during the observation period (e.g., Costello, Swendsen, Rose, & Dierker, 2008; Olino, Klein, Lewinsohn, Rhode & Seeley, 2010). Arizaga, Polo, and Martinez-Torteya (in press) used growth mixture modeling to characterize depression trajectory groups over two years among 133 Latino youth. Most children (77%) were in a stable low class, although 15% of youth had an initially high and declining (i.e., recovery) trajectory, and 8% of children had a moderate and escalating trajectory. Importantly, there are several critiques of trajectory class/mixture modeling (Bauer, 2007; Vachon et al., 2017). One concern is that the approach may be biased with non-normal data, which is typical of youth mental health symptoms. Specifically, the use of trajectory class modeling can “over-extract” classes, suggesting the presence of multiple latent change patterns when only a single distribution underlies the data (Vachon et al., 2017). Trajectory class solutions may also be inconsistently identified within and across studies (Vachon et al., 2017). In this study, we argue for the use of latent growth modeling, which presents fewer estimation challenges and can model the full range of trajectory variability without artificially creating discrete classes.

Overall, making conclusive statements about typical change trajectories is complicated given that studies vary in terms of developmental timeframes, sample diversity, outcome measures, and the longitudinal analysis used. In general, research has often shown average within-person declines in anxiety and depression across adolescence that differ by child sex, but the literature also strongly indicates between-individual differences in symptom development. Consistent with prevalence rates provided by epidemiological data (Merikangas et al., 2010), prior studies with community samples show that most children typically exhibit relatively few internalizing symptoms on average over time, with a smaller proportion of youth showing more clinically significant symptoms (Merikangas, Nakamura, & Kessler, 2009).

The prior studies focused specifically on Latino youth have advanced our understanding of internalizing symptom trajectory variability, yet they also have several limitations. Studies have generally used self-report scales, whereas only one study has examined changes in symptoms based on a structured psychiatric interview (Ramos-Olazagasti et al., 2013), which can provide important information in terms of symptom presentation. Commonly used broadband measures, such as the CBCL, do not disentangle symptoms of anxiety and depression, and the study by Ramos-Olazagasti et al. (2013) appears to have combined symptom dimensions from the DISC-IV for an overall symptom count. Therefore, one key gap in the literature is that prior studies have not separately examined symptoms of anxiety or depression. This gap is important since there may be unique contextual correlates of anxiety and depression symptoms. Although there is robust evidence that children’s anxiety and depression trajectories are positively associated (Cummings, Caporino, & Kendall, 2014), this longitudinal association has not been examined among Mexican-origin youth. Furthermore, prior studies have used a limited number of time points (3–4) to characterize trajectories, and aside from the Zeiders et al. (2013) study across ages 12–22, the prior studies have examined only two- or three-year periods in adolescence. Using a large sample with more time points spanning a wider developmental window would provide a clearer picture of internalizing symptom trajectories. In addition, few studies have focused on an ethnically homogenous sample of Mexican-origin youth; a within-group perspective would provide more understanding of internalizing development within the largest segment of minority youth in the U.S (García Coll et al., 2000).

Cultural influences on internalizing problems among Latino youth

In studying within-group variability among Mexican-origin youth, it is important to consider how their unique cultural experiences may influence the development of internalizing symptoms. We draw on the integrative model of child development from García Coll et al. (1996), which emphasizes the important intersections of cultural and socioeconomic contexts in shaping youth adjustment. For youth in immigrant families, one relevant sociodemographic variable is country of birth (i.e., nativity). The limited research on differences in child internalizing problems by nativity shows inconsistent evidence (e.g., Alegría, Sribney, Woo, Torres, & Guarnaccia, 2007; Polo & López, 2009). Examining longitudinal trajectories of internalizing symptoms by nativity can clarify possible differences in risk across adolescence. Moreover, the prior mixed findings for this proxy variable also highlight the importance of explicitly studying specific cultural processes in relation to internalizing problems (García Coll & Magnuson, 2000).

For ethnic minority youth, retention of heritage cultural traditions may provide a mechanism for coping with stressors that arise from their disadvantaged social position (García Coll et al., 1996). In contrast, the uptake of mainstream cultural traditions, at the expense of heritage traditions, may be detrimental to youth well-being (Gonzales et al., 2015). This study focuses on acculturation, which refers to the process of adapting to aspects of mainstream American culture, and enculturation, which describes adaptation to one’s heritage culture (García Coll & Magnuson, 2000; Gonzales et al., 2015; Knight et al., 2010). Contemporary acculturation theory proposes a multidimensional longitudinal process that occurs across immigrant generations, reflected in terms of evolving orientation to mainstream and heritage cultural (a) practices, (b) values and attitudes, and (c) identifications (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010). Different aspects of mainstream and heritage culture may change at different rates, and change in one dimension (e.g., English language use) does not necessarily covary with change in other dimensions (e.g., ethnic identity). Longitudinal research has supported the notion of dynamic cultural change across adolescence (e.g., Cruz, King, Cauce, Conger & Robins, 2017; Knight et al., 2014; Updegraff et al., 2014). Using the organizing framework of cultural identity conceptualized by Schwartz et al. (2010), the cultural factors of interest in this study included (a) English and Spanish use (cultural practices), (b) familism and traditional gender role attitudes (cultural values/beliefs), and (c) ethnic pride (cultural identification). These variables were selected based on theoretical justification (García Coll et al., 1996; Schwartz et al., 2010; Zahn-Waxler, Shirtcliff, & Marceau, 2008), and prior attention in empirical studies as being relevant for youth adjustment, including internalizing problems (Anderson & Mayes, 2010; Gonzales et al., 2015; Rivas-Drake et al., 2014).

Language use as a cultural practice is a crucial component of the acculturation process, and English and Spanish in youth’s daily lives is more nuanced than what can be captured with a simple binary or proxy marker, such as preferred language. Youth may seamlessly “code-switch” between English and Spanish across different settings, or experience tension in the expectation to use English in some settings (e.g., school) and Spanish in others (e.g., home), which may be complicated by a typical decline in Spanish use for 2nd and 3rd generation youth (Cruz et al., 2017). These tensions may influence adolescent’s well-being and possibly increase anxiety, for example, in situations where the non-dominant language is expected. Language use may also reflect cultural differences in anxiety sensitivity and in the expression of psychopathology (Piña & Silverman, 2004), or socioeconomic differences. Prior studies have provided mixed evidence regarding an association between language use and internalizing problems (Gudiño, Nadeem, Katoka & Lau, 2011; Martinez, Polo, & Carter, 2012). Mixed findings are likely due in part to the reliance on cross-sectional analysis, a lack of attention to potential socioeconomic confounds, and inconsistency in measuring anxiety dimensions or the use of broad internalizing measures rather than assessing anxiety and depression. Language use has also been assessed inconsistently, such as using parent report of children’s language use (Polo & López, 2009), proxy measurement of language use (Piña & Silverman, 2004), English proficiency (Gudiño et al., 2011), or combining typical language use and proficiency (Martinez et al., 2012). Mixed findings can be clarified by longitudinal research on the co-development of internalizing and language use that carefully specifies language use and accounts for socioeconomic factors.

Familism is a key traditional cultural value that emphasizes the centrality of the family through close and supportive family bonds, prioritizing assistance to one’s family, and identifying oneself in terms of the family unit (Knight et al., 2010). Familism tends to decline among Mexican-origin youth over time (Knight et al., 2014), and studies have suggested that the erosion of familism over time is an important influence on youth adjustment (Cruz et al., 2017). There is fairly robust evidence for familism as a protective cultural factor for Latino youth internalizing problems from cross-sectional (Stein, Gonzalez, Cupito, Kiang, & Supple, 2015; Cupito, Stein, Gonzalez, & Supple, 2016) and daily diary (Telzer, Gonzales, Tsai, & Fuligni, 2015; Torres & Santiago, 2018) studies, with limited evidence demonstrating the opposite (Kuhlberg, Peña, & Zayas, 2010) or no effect (Updegraff, Umaña-Taylor, McHale, Wheeler & Perez-Brena, 2012). Longitudinal research indicates that higher familism is related to fewer internalizing symptoms among Latino youth, although these studies examined familism as a within-time point (Smokowski et al., 2010; Zeiders et al., 2013), or trajectory class covariate (Arizaga et al., in press), and no research has investigated parallel changes in familism and internalizing symptoms.

Traditional gender role (TGR) attitudes relate to culturally-grounded gender expectations that frame socialization of children’s behavior. Latino TGR beliefs place greater emphasis on family obligations for girls and suggest that they should be protected, whereas boys are allowed to be more independent; this contrasts with typical American cultural norms giving greater latitude for girls to be autonomous (Anderson & Mayes, 2010). TGR attitudes decline on average over time, particularly for Latina girls (Updegraff et al., 2014). Scholars speculate that TGR attitudes may help to explain sex and ethnic differences in internalizing problem development, and that adhering to TGR may be culturally adaptive for Latina girls and protect against depression symptoms (Anderson & Mayes, 2010; Zahn-Waxler et al., 2008). Prior results with Latino youth have been inconsistent; in one study, higher TGR attitudes predicted lower internalizing symptoms (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2012), whereas another study showed no relation (Updegraff et al., 2012). Overall, prior studies highlight the potential role of TGR attitudes on internalizing symptoms, and suggest the need for careful longitudinal research.

Ethnic identity is another cultural attribute that has shown protective effects against maladjustment (Rivas-Drake et al, 2014). Ethnic pride (also known as ethnic affirmation) is one facet of positive ethnic affect (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014), indicated by having positive regard for one’s ethnic group (Phinney, 1992). This positive regard typically develops across adolescence as youth become more aware of their ethnic heritage (French, Seidman, Allen & Aber, 2006). Scholars suggest that ethnic pride may be one of the most relevant aspects of ethnic identity for mental health adjustment (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014), and may buffer youth well-being from systemic challenges such as discrimination (Gonzales et al., 2015). Cross-sectional evidence suggests that greater ethnic pride is related to fewer depressive symptoms among Latino adolescents (Berkel et al., 2010; Stein et al. 2015), and a daily diary study indicated that greater ethnic pride was related to lower average anxiety across 1–2 weeks (Kiang, Yip, Gonzales-Backen, Witkow, & Fuligni, 2006). Operationalizing positive ethnic affect and outcomes in different ways have suggested a potentially specific link between ethnic pride and internalizing symptoms. For example, longitudinal research has indicated no direct prospective association between ethnic identity commitment and depression trajectories (Stein et al., 2016), and no parallel changes in ethnic identity and self-esteem (Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen & Guimond, 2009). To our knowledge, no research has examined the co-development of ethnic pride and internalizing symptoms across adolescence, although the prior evidence generally suggests that ethnic pride would be protective against both depressive and anxiety symptoms.

In summary, there is limited research on developmental trajectories of internalizing symptoms among Mexican-origin youth. In particular, there are few studies that separately model depression and anxiety using assessment information from a structured psychiatric interview. Generalized anxiety symptoms are particularly relevant for Mexican-origin youth, yet no longitudinal research has examined this symptom dimension. In addition, there is some mixed evidence regarding how cultural features (e.g., language use, cultural values and attitudes, and ethnic identity) relate to internalizing symptoms for Latino youth. One potentially important contributor to these mixed findings is the reliance on cross-sectional studies. Given the typical variability in internalizing symptoms and cultural orientation over time, additional longitudinal research is critical. The few prior longitudinal studies investigated cultural factors as a within-timepoint or internalizing growth class covariate; these approaches do not address other possible longitudinal connections. One key addition to the literature would be to examine internalizing trajectories and cultural change as parallel developmental processes (Cheong, MacKinnon, & Khoo, 2003), which would clarify whether these features are related prospectively and over time.

Based on the existing developmental research reviewed above, we hypothesized that: (1a) there would be significant between-individual variability in trajectories of anxiety and depression symptoms; (1b) anxiety symptoms would decrease on average over time, whereas depression symptoms would decrease more steeply among boys relative to girls; and (2) there would be significant associations between the growth processes for anxiety and depression such that individuals increasing in anxiety will show corresponding increases in depression. Although prior research examining culture and internalizing symptoms has produced some inconsistent findings, our overall synthesis suggested that we could make more confident predictions about links between internalizing symptoms and familism, gender roles, and ethnic pride. We expected that (3a) results would show negative associations between anxiety and depression symptom trajectory parameters (concurrent, prospective, and longitudinal relations) and putative protective factors of familism, TGR attitudes, and ethnic pride. Alternately with language use, the findings have been inconsistent and little guidance is available to predict the longitudinal effect on internalizing symptoms. Therefore, our analysis of these longitudinal associations was exploratory. In all models, we adjusted for child sex, nativity, mother’s education in years, and family income to account for important socioeconomic factors (García Coll et al., 1996), and to provide a more stringent test of the specific role of cultural factors in relation to internalizing.

Method

Study Design

We used data from the California Families Project (CFP), an ongoing longitudinal study of 674 Mexican-origin youth development. Participants were recruited from school rosters in Northern California. The first assessment occurred when the youth were in 5th grade (Mage=10.86, SD=0.51), and annual assessments continued through to the 12th grade (8 waves total). Children, mothers, and fathers were interviewed in English or Spanish in their home for all waves. Family retention ranged from 85% to 92% across the study waves. Children were predominantly 2nd generation (62%; 1st generation= 28%; 3rd generation= 10%). Youth born in Mexico had lived in the U.S. for an average of 11.57 years (SD = 2.67, range = 3–17). Median family income at Wave 1 was approximately $37,500 (range = $5,000 to > $90,000). Information about the CFP sample has been published widely in other studies (e.g., Hernández, Robins, Widaman & Conger, 2016). The measures used in the current study were all collected through child self-report. Descriptive statistics for the main study variables and correlations among cultural variables are provided in the supplemental materials (see Supplemental Table 1, and Supplemental Figure 1).

Measures

Internalizing symptoms.

The National Institute of Mental Health DISC-IV is a structured interview developed to assess 30 psychiatric diagnoses for children and adolescents in both English and Spanish (Shaffer et al., 2000). This study used items from the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD; 12 items) module and the Major Depression (MD, 22 items) module, which were administered annually at Waves 1–8. The GAD module assesses features of anxiety and worry (e.g., “Have you worried a lot that you might have some sickness or illness?”). The MD section assessed features of childhood depression (e.g., “Was there a time when you felt grouchy/irritable, and little things made your mad?”). On most items, children reported whether they had experienced a symptom within the past year (0 = no, 1 = yes). Symptom count variables were calculated by computer algorithm. Seven percent of youth met diagnostic criteria for GAD (7.2%) or MD (7.1%) during the study period as assessed by the DISC-IV. Fewer children met diagnostic criteria for GAD (0.3% - 3.9%) or MD (0.5% - 1.8%) at each wave. These figures are similar to prior community-based studies (Merikangas et al., 2009) and are comparable with population estimates (Merikangas et al., 2010). As expected, the range of symptoms (see Supplemental Table 1) shows that many youths are exhibiting clinically relevant symptom levels.

Language use.

English and Spanish language use were measured annually at Waves 1–6 with the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II Scale (ARSMA-II; Cuellar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995). Ten total items (five per language) reliably measured English use (αwave1–6 = .71–.77) and Spanish use (αwave1–6 = .80–.83). Children were asked to report how often they spoke, wrote, thought, listened to music, and watched television in each language on a 4-point frequency scale ranging from 1 (almost never or never) to 4 (almost always or always).

Cultural Values.

The Mexican-American Cultural Values Scale (MACVS; Knight et al., 2010) was used to measure familism and traditional gender roles at Waves 1, 3, 5 and 7. Youth rated items on a 4-point scale (1= not at all, 4 = very much). The familism subscale (16 items) measured how much youth valued emotional support, opinions from the family, and family obligations (e.g., “A person should always think about their family when making important decisions”). The subscale had high reliability for waves 1–7 (αWave1–7 = .82-.88). The TGR attitudes subscale included 5 items (e.g., “It is important for the man to have more power in the family than the woman”). The subscale had lower but adequate reliability (αWave1–7= .64–.75).

Mexican-American Ethnic Pride.

The 8-item Mexican-American Ethnic Pride scale, adapted from Phinney (1992), was administered at Waves 1, 3, 5, and 7 (αwave1–7= .75–.78). The scale measured positive affirmation towards one’s ethnic background (e.g., “You have a lot of pride in your Mexican roots”) with items rated on a 4-point scale (1=not at all true, 4=very true).

Covariates.

Control variables included child sex (0 = male, 1 = female) and nativity (0 = Mexico, 1 = U.S,), mother’s education in years, and mother report of total family income.

Analysis Plan

Analyses were conducted using Mplus Version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2018). First, we used univariate latent basis growth curve analyses with robust maximum likelihood estimation to model MD and GAD symptom trajectories. Latent basis models were used to best capture non-linear changes in symptoms and culture, while also parsimoniously representing the growth parameters using only a linear slope term (versus needing to model a quadratic or cubic term). The age 10 slope factor loading was fixed to zero and the age 18 slope factor loading was set to seven, whereas the other time points were freely estimated. Covariance terms were estimated between the intercept and slope factors. Covariates (child sex, nativity, mother’s education, and family income) were next added to the model to adjust for socioeconomic factors, and provide the final univariate trajectory estimates for MD and GAD.

The GAD and MD outcome variables were non-normally distributed, and using typical models that assume normally distributed outcome variables could lead to incorrect or biased inferences (Atkins, Baldwin, Zheng, Gallop & Neighbors, 2013; Wang, Zhang, McArdle & Salthouse, 2009). The GAD outcome variable had highly skewed continuous distributions at each timepoint, therefore, we examined whether a continuous or censored specification would best represent the outcome distributions. We expected that a censored specification might be a better fit for GAD, since it would be better suited to model non-normality and a lower bound of zero (Wang et al., 2009). The MD outcome variable also had highly skewed distributions at each timepoint, but the distributions were count-like in that they only included non-negative integers (Atkins et al., 2013). Given this count-type distribution, we expected that a negative binomial specification, rather than a typical continuous specification, might be a better representation of the MD outcome variable. We tested different distribution specifications using the Aikake Information Criteria and adjusted Bayesian Information Criteria values to select the best fitting one (Kline, 2011), and these specifications were retained in subsequent models.

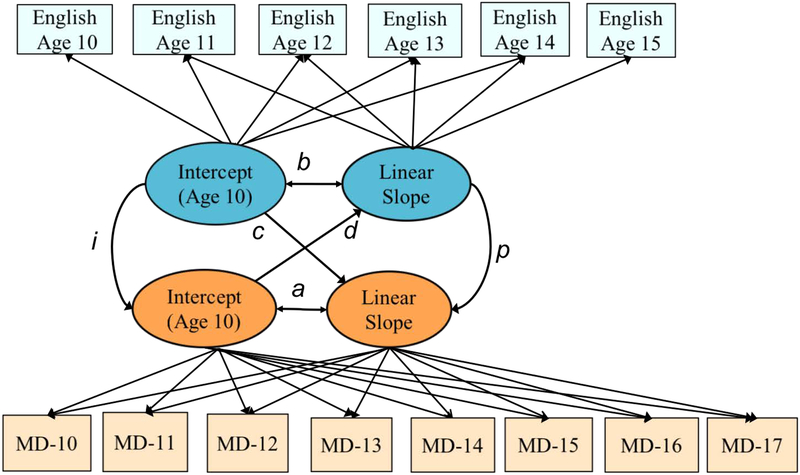

Next, we used parallel process growth models (PPGMs; Cheong et al., 2003) to examine covariation among MD and GAD symptom trajectories, and covariation between each internalizing outcome and cultural factor. PPGMs allow for the modeling of bivariate developmental trajectories, including the concurrent association between initial levels each variable (i), prospective associations between initial levels of one outcome, and slope of the other outcome (c and d), and also for modeling correlation in change over time between processes (p) (see Figure 1). PPGM intercept and slope parameters were adjusted for socioeconomic covariates as in the univariate models. In addition, English use PPGM models controlled for age 10 Spanish use, and Spanish PPGMs controlled for age 10 English use.

Figure 1.

Example parallel process model showing paths between English use and Depression symptom trajectories

For GAD, at least 558 youth (83% of sample) had data at each wave; most youth had data at 7 or all 8 waves (8 waves = 58%, 7 = 20%, 6 = 8%, 5 = 4%, 4 = 4%, 3 = 2%, 2 = 3%, 1 = 2%). At least 523 youth (78% of sample) reported on MD at each wave; most youth had data on at least 6 of 8 waves (8 waves = 37%, 7 = 28%, 6 = 16%, 5 = 5%, 4 = 5%, 3 = 2%, 2 = 4%, 1 = 2%, 0 = .2%). We addressed missing data using full information maximum likelihood with a robust sandwich estimator (MLR) using all available data to estimate trajectories, resulting in very few missing cases (≤ 1% across all analyses). Chi-square tests showed that missing values for GAD and MD were not associated with child sex or nativity. One-way analysis of variance tests showed that missingness was associated with lower income and education. All four covariates were estimated in the growth models to optimize model estimation (Graham, 2003).

Results

Developmental Trajectories of Internalizing Symptoms

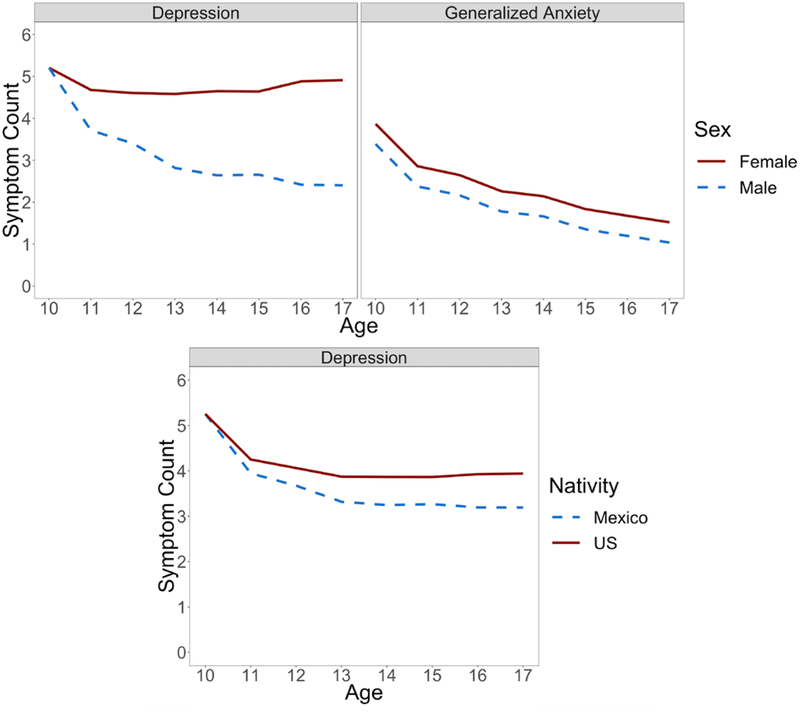

For symptoms of GAD, the censored-normal specification (AIC = 21962.72, aBIC = 22012.23) fit the data better than the continuous-normal distribution (AIC = 22598.35, aBIC = 22647.86). For MD, the negative binomial model (AIC = 25173.99, aBIC = 25222.16) provided a better fit to the data compared to the continuous model (AIC = 28206.45, aBIC = 28254.63). Adjusting for covariates, these models showed declining trajectories on average for both GAD (Mlevel = 3.58, σ2level = 1.86, Mslope = −0.43, σ2slope = .09, all ps < .001) and MD symptoms (Mlevel = 5.24, σ2level = 1.69, Mslope = −.09, σ2slope =.02, all ps < .001), and significant between-individual variability indicated by the σ2 parameter values. Girls had higher mean levels of GAD compared to boys (β = .15, p = .008) starting at age 10, and increasing mother education was associated with steeper increases in GAD symptoms over time (β = .17, p = .003). For MD, girls had a more positive slope compared to boys (β = .39, p < .001)(see Figure 1).

Co-Development of Anxiety and Depression Trajectories

Because of the computational complexity of modeling negative binomial and censored-normal parallel processes for GAD and MD trajectories, GAD was specified as a continuous variable in this model. Age 10 levels of GAD and MD were positively associated, with higher initial levels of GAD related to higher initial levels of MD (β = .96, p < .001)(see Table 1). Higher age 10 levels of GAD were prospectively related to less steep declines in MD (β = −.35, p < .001), and higher age 10 MD was prospectively related to less steep declines in GAD (β = −.67, p < .001). The slopes of GAD and MD were positively associated (β = .74, p < .001), indicating that steeper reductions in one internalizing dimension were associated with steeper reductions in the other dimension (see Supplemental Figure 2).

Table 1.

Parallel process growth model results showing co-development of internalizing problems with language use, cultural values, traditional gender role attitudes, and ethnic pride

| (Level1, Level2) β (95% CI) | (Slope1, Slope2) β (95% CI) | (Level1, Slope2) β (95% CI) | (Level2, Slope1) β (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression Symptoms2 | ||||

| Generalized Anxiety1 | .96 [.91, 1.00]*** | .74 [.63, .86]*** | −.35 [−.46, −.24]*** | −.67 [−.77, −.57]*** |

| Cultural Domain1 | ||||

| English | .21 [−.02, .44]^ | .30 [−.05, .65] | −.02 [−.21, .17] | −.37 [−.72, −.02]* |

| Spanish | −.21 [−.38, −.03]* | −.27 [−.46, −.08]** | −.04 [−.19, .10] | .18 [.03, .33]** |

| Familism Values | −.18 [−.36, −.002]* | −.34 [−.56, −.12]** | .09 [−.10, .28] | .15 [−.09, .38] |

| TGR Attitudes | .09 [−.12, .30] | .03 [−.32, .37] | −.19 [−.41, .02]^ | −.08 [−.34, .18] |

| Ethnic Pride | −.22 [−.41, −.03]* | −.27 [−.48, −.05]* | .10 [−.10, .30] | .07 [−.12, .25] |

| Cultural Domain1 | Generalized Anxiety Symptoms2 | |||

| English | −.39 [−.95, .17] | −.04 [−.53, .44] | .32 [−.16, .80] | .20 [−.44, .84] |

| Spanish | .18 [−.22, .59] | .04 [−.28, .37] | −.18 [−.49, .14] | −.15 [−.64, .35] |

| Familism Values | .11 [−.20, .43] | .01 [−.38, .23] | −.08 [−.38, .23] | −.09 [−.37, .19] |

| TGR Attitudes | .34 [.10, .59]* | .17 [−.48, .10] | −.19 [−.57, −.06]* | −.31 [−.16, .49] |

| Ethnic Pride | −.14 [−.48, .20] | −.26 [−.49, −.02]* | .14 [−.20, .48] | .09 [−.15, .33] |

Note: β = fully standardized coefficients from Mplus model output (STDYX Standardization); TGR = Traditional gender role.

p <.001,

p < .01,

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .08

Internalizing Symptoms and Cultural Development as Parallel Processes

Depression.

Higher age 10 Spanish use was associated with lower age 10 MD (β = −.21, p = .03). Higher age 10 MD was related to steeper decreases in English use over time (β = −.37, p = .04) and steeper increases in Spanish use over time (β = .18, p = .001)(see Supplemental Figure 3). There was also a negative parallel association between Spanish use and MD (β = −.27, p = .009), such that steeper increases in Spanish use were associated with steeper declines in MD. Higher age 10 TGR attitudes were associated with more negative slopes of MD (β = −.19, p = .07), although this finding did not reach the conventional threshold for statistical significance. Familism and MD showed a negative cross-sectional association at age 10 (β = −.18, p = .05), and their slopes were inversely related over time (β = −.34, p = .01) (see Figure 2). Similarly, lower age 10 ethnic pride was associated with higher age 10 MD (β = −.22, p = .04) and more positive slopes for ethnic pride were associated with steeper declines in MD (β = −.27, p = .05).

Figure 2.

Multigroup models showing average depression and generalized anxiety symptom trajectories by child sex and nativity

Generalized anxiety.

There was a positive association between age 10 TGR attitudes and GAD (β = .34, p = .005), and a negative prospective association between age 10 TGR attitudes and GAD over time (β = −.19, p = .02). This indicates that greater endorsement of age 10 TGR attitudes was related to higher age 10 GAD, but also related to more negative slopes of GAD. For ethnic pride, there was a significant negative longitudinal association with more positive slopes of ethnic pride related to steeper declines in GAD over time (β = −.26, p = .01).

Discussion

Mexican-origin youth have elevated rates of internalizing problems, and it is important to better understand the development of anxiety and depression symptoms within this group. As expected, we found evidence for significant between-individual variability in anxiety and depression trajectories. In terms of typical trajectories, we found evidence for average declines in anxiety symptoms, with girls reporting higher symptoms relative to boys from age 10 to 17, and average declines in depression symptoms, with similar initial levels but steeper declines among boys compared to girls. These results support the average declines in internalizing symptoms seen in other studies with Latino youth (Sirin et al., 2015; Smokowski et al., 2010; Zeiders et al., 2013), and are generally consistent with sex differences found in other studies (e.g., Hankin, 2009). Although their average symptoms did decline temporarily during the study period, our results complement other work showing that Latina girls are at elevated risk for internalizing problems (Anderson & Mayes, 2010; Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2012). Youth born in Mexico (28% of the sample) had similar initial levels and significantly steeper declines in depression compared to U.S.-born youth. Although cross-sectional studies have found mixed evidence for the influence of nativity on internalizing symptoms (Alegría et al., 2007; Polo & López, 2009), our analysis across eight years indicated an immigrant advantage for depression trajectories from late childhood into adolescence.

We also found robust evidence for the link between anxiety and depression, evidenced by significant concurrent (intercept to intercept), prospective (intercept to slope), and longitudinal (slope to slope) associations. These findings reinforce the literature on the comorbidity of adolescent trajectories of depression and anxiety (Cummings et al., 2014; McLaughlin & King, 2015), providing the first empirical evidence of their co-development in Mexican-origin youth. The high comorbidity between these internalizing dimensions may result from similar risk factor constellations and a variety of potential developmental pathways in which depression and anxiety emerge sequentially or in parallel (Cummings et al., 2014).

In addition, this study evaluated whether the development of anxiety and depression were associated with cultural adaptation trajectories from childhood to adolescence. English and Spanish language use are cultural practices highly relevant in the development of Mexican-origin youth, although the literature examining their relation with internalizing problems among Latino youth is quite mixed (Gudiño et al., 2011; Polo & López, 2009; Martinez et al., 2012). Language use was specifically associated with MD symptoms rather than GAD symptoms. Specifically, greater age 10 Spanish was related to lower age 10 MD, and steeper increases in Spanish use were associated with steeper declines in MD symptoms, accounting for the influence of childhood English use levels. Children’s maintenance of Spanish may help to improve communication with their parent(s)/caregiver(s) and extended family, and also reflect other protective parenting or health attributes within the child’s social network (Allen et al., 2008). Early MD symptoms were also related to Spanish and English language use development, with higher age 10 MD symptoms predicting steeper increases in Spanish and declines in English use. This finding points to the utility of a parallel process approach, as cross-sectional and other longitudinal analyses would have missed this effect. There has been little theory and research examining the prospective effects of youth psychopathology on cultural adaptation (Updegraff et al., 2012). It may be that youth with greater early mood symptoms increasingly turn to their heritage language as a coping strategy to reinforce within-group connections with family and peers. More research is needed to understand the reciprocal associations between early psychopathology and language use patterns during adolescence.

The evolution of cultural values is another key aspect of Mexican-origin youth development. Familism, in particular, has received substantial attention in the literature, with fairly robust evidence that higher endorsement of familism is a protective factor for externalizing problems (Cruz, King, Mechammil, Bámaca-Colbert, & Robins, 2018), but relatively less attention to its influence on internalizing problems (e.g., Smokowski et al., 2010; Updegraff et al., 2012). Our results showed that familism and MD symptoms were inversely associated in childhood, and changed in parallel across adolescence, with more positive familism slopes associated with greater declines in MD symptoms across ages 10–17. This adds to a growing body of longitudinal research indicating that the maintenance of familism over time is associated with a protective effect for Mexican-origin youth internalizing (Smokowski et al., 2010; Zeiders et al., 2013). Although familism is likely associated with improved family relationships that are beneficial for mood and well-being, the parallel process model does not indicate the direction of effects and it may be that declining MD symptoms provide youth with a more positive outlook on their relationships and responsibilities within the family. It is relevant to understand the mechanisms that may link increasing familism with decreasing MD symptoms, such as reduced family conflict (Kuhlberg et al., 2010). Other research suggests that different aspects of familism, such as family obligation attitudes versus family assistance behaviors, may exert differential protective versus risk influences (Telzer et al., 2015). The benefits of emotional connection to one’s family may at times be outweighed by the stress of assisting family members; this nuance in the family system is especially relevant in working with Latino adolescents. There were no significant relations with GAD, suggesting that familism is specifically related to mood symptoms.

Traditional gender role (TGR) attitudes are another domain of cultural beliefs and values, which become increasingly relevant across adolescence as youth navigate their changing social and familial roles. The limited existing literature has shown mixed results for the links between TGR and internalizing symptoms among Latino youth (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2012; Updegraff et al., 2012). Our results showed a positive concurrent association between age 10 TGR attitudes and age 10 GAD, and prospective effects on GAD and MD such that higher age 10 TGR attitudes were related to steeper declines in internalizing symptoms. These findings point to a protective effect of TGR, which may operate through family mediators such as family cohesion (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2012). Latino youth who have high early endorsement of TGR may find that their attitudes are a more optimal fit with the expectations from family members, peers, and other community members, and may face fewer adjustment difficulties over time. Alongside other findings suggesting a possible risk effect of traditional masculinity attitudes on internalizing symptoms (Rogers, DeLay, & Martin, 2017), our results suggest that it is important to better understand TGR attitude changes among Mexican-origin youth, including for whom and why those attitudes may predict the development of internalizing problems.

Ethnic identity is a key feature in minority youth development, and is generally associated with more optimal adjustment (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014). We found a significant negative concurrent association for age 10 ethnic pride and MD, indicating that the early emergence of ethnic pride is a protective factor for early MD symptoms. We also found a significant negative association between the parallel slopes for ethnic pride and GAD, and ethnic pride and MD, with increasingly positive slopes of ethnic pride related to steeper declines in GAD and MD. This builds on other work showing a protective effect of stronger ethnic pride on internalizing symptoms (Berkel et al., 2010), and daily mood/anxiety ratings (Kiang et al., 2006; Torres & Santiago, 2018). Although other work indicated no prospective association between ethnic identity commitment and depression trajectories (Stein et al., 2016), our findings suggest that changes in MD and ethnic pride covary together. There is limited research with Latino youth regarding the influence of ethnic identity on anxiety (Kiang et al., 2006) and to our knowledge, our results are among the first to show that ethnic pride development is longitudinally related to GAD symptoms. The development of ethnic pride may help Mexican-origin youth to cope with general worry and stress in adolescence, especially with the extra challenges they may experience from discrimination and prejudice (Berkel et al., 2010).

This study had a number of strengths. We utilized a rich longitudinal dataset with eight yearly assessment points, and a large sample of Mexican-origin youth, which allowed us to characterize average and individual trajectories of GAD and MD symptoms, and their co-development, in an ethnically homogeneous minority group. Examining cultural adaptation in relation to youth psychopathology is an important endeavor (García Coll et al., 2000). Although others have studied cultural adaptation and internalizing symptoms, to our knowledge this was the first study that examined internalizing symptoms and cultural adaptation processes using parallel process growth modeling. This strategy allowed us to test whether cultural adaptation was related to changes in GAD and MD symptoms, which addresses important theoretical questions and provides information that can be useful for clinicians working with Mexican-origin youth. We found that cultural trajectory parameters were more robustly associated with MD symptom trajectories relative to GAD trajectories, illustrating the benefits of clearly specifying and testing separate internalizing symptom domains.

There were several limitations to the current study. Our approach of using the DISC-IV symptom counts did not provide information about functional impairment or disorder status; thus, we are unable to give a full perspective on the various possible trajectories of progressing between disordered and non-disordered status. Since we studied a community sample with low anxiety and depression disorder prevalence (0.3% - 1.8 % at each wave), the symptom count approach was more appropriate. This study was further limited by using only child self-report, which may introduce mono-method and reporter bias, and possibly inflate estimates due to shared method variance. Although some studies show there are associations between child and parent cultural attitudes (Updegraff et al., 2014), studies also indicate that parent-child cultural discrepancy, including differences in the attitudes regarding TGR or affiliative obedience, may be associated with risk for internalizing problems (Stein & Polo, 2014). Including multiple reporters is necessary to understand intra-family cultural dynamics and internalizing symptom development. Our analysis examined cultural factors separately, and did not address the dynamic constellation of cultural practices, values and identity, which may be uniquely associated with outcomes. Missingness on MD and GAD variables was associated with socioeconomic status (family income and mother’s education), and while this could possibly bias the findings, the likelihood is reduced since we included those covariates of missingness in the analysis models (Graham, 2003). In addition, this study focused on Mexican-origin youth in California, and the results may not generalize to other Latino youth subgroups or geographic regions.

Future research should focus on the mechanisms linking cultural adaptation to the development of anxiety and depression symptoms. Family disruption and cultural stress are two commonly hypothesized mechanisms linking cultural change with negative outcomes, and evidence suggests these factors are relevant in the development of depression (Cano et al. 2015; Gonzales et al., 2015). Given the many permutations of longitudinal modeling that are possible, theory should guide tests of longitudinal mediation to evaluate how family and cultural stress mechanisms might exert their influences. Future research in this area should also account for the important effects of parental depression and anxiety psychopathology.

This study has implications for the cultural adaptation of evidence-based interventions with Mexican-origin youth. Clinicians working with youth should promote the retention of adaptive heritage culture features, including familism and ethnic pride. Clinicians can help youth to navigate their developing gender role attitudes, including possible differences between their home environment and the broader community. Since ethnic identity and TGR attitudes both emerge in the context of familial ethnic socialization (Sanchez, Whittaker, Hamilton, & Arango, 2017), it would also be relevant for interventions to help parents tailor their ethnic socialization messages to optimize trajectories of cultural adaptation and support positive mental health for their children.

Supplementary Material

Authors’ Acknowldegements:

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA017902) to Richard W. Robins and Rand D. Conger. We thank the participating families, staff, and research assistants who took part in this study. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

We also tested multigroup PPGMs to evaluate whether growth trajectory covariance parameters differed by child sex and nativity. We found no differences; thus, the more straightforward covariate method was retained.

References

- Albano AM, Chorpita BF, & Barlow DH (2003). Childhood anxiety disorders. Child Psychopathology, 2nd Ed. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Sribney W, Woo M, Torres M, & Guarnaccia P (2007). Looking beyond nativity: The relation of age of immigration, length of residence, and birth cohorts to the risk of onset of psychiatric disorders for Latinos. Research in Human Development, 4, 19–47. 10.1080/15427600701480980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen ML, Elliott MN, Fuligni AJ, Morales LS, Hambarsoomian K, & Schuster MA (2008). The relationship between Spanish language use and substance use behaviors among Latino youth: A social network approach. Journal of Adolescent Health, 43, 372–379. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson ER, & Mayes LC (2010). Race/ethnicity and internalizing disorders in youth: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 338–348. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arizaga JA, Polo AJ, & Martinez-Torteya C (in press). Heterogeneous trajectories of depression symptoms in Latino youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1443457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DC, Baldwin SA, Zheng C, Gallop RJ, & Neighbors C (2012). A tutorial on count regression and zero-altered count models for longitudinal substance use data. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(1), 166–77. 10.1080/15374416.2018.1443457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ (2007). Observations on the use of growth mixture models in psychological research. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42, 757–786. 10.1080/00273170701710338 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke AO, Plunkett SW, Sands T, & Bámaca-Colbert MY (2011). The relationship between Latino adolescents’ perceptions of discrimination, neighborhood risk, and parenting on self-esteem and depressive symptoms. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42, 1179–97. 10.1177/0022022110383424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Knight GP, Zeiders KH, Tein JY, Roosa MW, Gonzales NA, & Saenz D (2010). Discrimination and adjustment for Mexican American adolescents: A prospective examination of the benefits of culturally related values. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20, 893–915. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00668.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstein M, Ginsburg GS, Petras H, & Ialongo N (2010). Parent psychopathology and youth internalizing symptoms in an urban community: A latent growth model analysis. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 41, 61–87. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0152-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MÁ, Schwartz SJ, Castillo LG, Romero AJ, Huang S, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, … Szapocznik J (2015). Depressive symptoms and externalizing behaviors among Hispanic immigrant adolescents: Examining longitudinal effects of cultural stress. Journal of Adolescence, 42, 31–39. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong J, MacKinnon DP, & Khoo ST (2003). Investigation of mediational processes using parallel process latent growth curve modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 10, 238–262. 10.1207/s15328007sem1002_5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Costello EJ, & Angold A (2009). Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 764–772. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello DM, Swendsen J, Rose JS, & Dierker LC (2008). Risk and protective factors associated with trajectories of depressed mood from adolescence to early adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 173–183. 10.1037/0022-006x.76.2.173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz RA, King KM, Mechammil M, Bámaca-Colbert M, Robins RW (2018). Mexican-origin youth substance use trajectories: Examining associations with cultural and family factors. Developmental Psychology, 54, 111–126. 10.1037/dev0000387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz RA, King KM, Cauce AM, Conger RD, & Robins R (2017). Cultural orientation trajectories and substance use: Findings from a longitudinal study of Mexican-origin youth. Child Development, 88, 555–572. 10.1111/cdev.12586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar I, Arnold B, & Maldonado R (1995). Acculturation rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II: A revision of the original ARSMA Scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 17, 275–304. 10.1177/07399863950173001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings CM, Caporino NE, & Kendall PC (2014). Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: 20 years after. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 816–845. 10.1037/a0034733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupito AM, Stein GL, Gonzalez LM, & Supple AJ (2016). Familism and Latino adolescent depressive symptoms: The role of maternal warmth and support and school support. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22, 517–523. 10.1037/cdp0000097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French SE, Seidman E, Allen L, & Aber JL (2006). The development of ethnic identity during adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 42, 1–10. 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Coll C, Akerman A, & Cicchetti D (2000). Cultural influences on developmental processes and outcomes: Implications for the study of development and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 12(3), 333–356. 10.1017/s0954579400003059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Coll C, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH, Jenkins R, Garcia HV, & McAdoo HP (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67, 1891–1914. 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Coll CT, & Magnuson K (2000). Cultural differences as sources of developmental vulnerabilities and resources: A view from developmental research. In Meisels SJ & Shonkoff JP (Eds.), Handbook of early childhood intervention (pp. 94–111). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/cbo9780511529320.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Natsuaki MN, & Conger RD (2006). Trajectories of depressive symptoms and stressful life events among male and female adolescents in divorced and nondivorced families. Development and Psychopathology, 18, 253–273. 10.1017/s0954579406060147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glied S, & Pine DS (2002). Consequences and correlates of adolescent depression. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 156, 1009–1014. 10.1001/archpedi.156.10.1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales N, Jensen M, Montaño Z, & Wynne H (2015). The cultural adaptation and mental health of Mexican American adolescents (pp. 182–196). In Caldera Y & Lindsey E (Eds.), Handbook of Mexican American children and families: Multidisciplinary perspectives. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW (2003). Adding missing-data-relevant variables to FIML based structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling, 10, 80–100. 10.1207/s15328007sem1001_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gudiño OG, Nadeem E, Kataoka SH, & Lau AS (2011). Relative impact of violence exposure and immigrant stressors on Latino youth psychopathology. Journal of Community Psychology, 39, 316–335. 10.1002/jcop.20435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL (2009). Development of sex differences in depressive and co-occurring anxious symptoms during adolescence: Descriptive trajectories and potential explanations in a multiwave prospective study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38, 460–472. 10.1080/15374410902976288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández MM, Robins RW, Widaman KF, & Conger RD (2016). School belonging, generational status, and socioeconomic effects on Mexican-origin children’s later academic competence and expectations. Journal Of Research On Adolescence, 26, 241–256. 10.1111/jora.12188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudziak JJ, Achenbach TM, Althoff RR, & Pine DS (2007). A dimensional approach to developmental psychopathology. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 16, S16–S23. 10.1002/mpr.217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, Lowry R, … Ethier KA (2018). Youth risk behavior surveillance— United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ, 67(No. SS-8), 1–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, Yip T, Gonzales-Backen M, Witkow M, & Fuligni AJ (2006). Ethnic identity and the daily psychological well-being of adolescents from Mexican and Chinese backgrounds. Child Development, 77, 1338–1350. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00938.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Basilio CD, Cham H, Gonzales NA, Liu Y, & Umaña-Taylor AJ (2014). Trajectories of Mexican American and mainstream cultural calues among Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 2012–2027. 10.1007/s10964-013-9983-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Bonds DD, Germán M, Deardorff J, … Updegraff KA (2010). The Mexican American Cultural Values Scale for adolescents and adults. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 30, 444–481. doi: 10.1177/0272431609338178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlberg JA, Peña JB, & Zayas LH (2010). Familism, parent-adolescent conflict, self-esteem, internalizing behaviors and suicide attempts among adolescent Latinas. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 41, 425–440. doi: 10.1007/s10578-010-0179-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Ritt-Olson A, & Soto D (2012). Acculturation, enculturation, and symptoms of depression in Hispanic youth: The roles of gender, Hispanic cultural values, and family functioning. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 1350–1365. 10.1007/s10964-012-9774-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez W, Polo AJ, & Carter JS (2012). Family orientation, language, and anxiety among low-income Latino youth. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 517–525. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hilt LM, & Nolen-Hoeksema S (2007). Racial/ethnic differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 801–816. 10.1007/s10802-007-9128-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, & King K (2015). Developmental trajectories of anxiety and depression in early adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43, 311–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, … Swendsen J (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication–adolescent supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49, 980–989. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Nakamura EF, & Kessler RC (2009). Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 11, 7–20. 10.1002/0471234311.ch24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, & Muthén B (2018). Mplus user’s guide (8th Ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, Klein DN, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, & Seeley JR (2010). Latent trajectory classes of depressive and anxiety disorders from adolescence to adulthood: descriptions of classes and associations with risk factors. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 51, 224–235. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten E (2016, April). The nation’s Latino population is defined by its youth. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center. Retrieved on July 1, 2016 from http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/2016/04/PH_2016-04-20_LatinoYouth-Final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS (1992). The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7, 156–176. doi: 10.1177/074355489272003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piña AA, & Silverman WK (2004). Clinical phenomenology, somatic symptoms, and distress in Hispanic/Latino and European American youths with anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 227–236. 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polo AJ, & López SR (2009). Culture, context, and the internalizing distress of Mexican American youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38, 273–285. 10.1080/15374410802698370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Olazagasti MA, Shrout PE, Yoshikawa H, Canino GJ, & Bird HR (2013). Contexual risk and promotive processes in Puerto Rican youths’ internalizing trajectories in Puerto Rico and New York. Development and Psychopathology, 25, 755–771. 10.1017/s0954579413000151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Seaton EK, Markstrom C, Quintana S, Syed M, Lee RM, … Yip T (2014). Ethnic and racial identity in adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child Development, 85, 40–57. 10.1111/cdev.12200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers AA, DeLay D, & Martin CL (2017). Traditional masculinity during the middle school transition: Associations with depressive symptoms and academic engagement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46, 709–724. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0545-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez D, Whittaker TA, Hamilton E, & Arango S (2017). Familial ethnic socialization, gender role attitudes, and ethnic identity development in Mexican-origin early adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 23, 335–347. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, & Szapocznik J (2010). Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist, 65, 237–251. 10.1037/a0019330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Prudence F, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, & Schwab-Stone ME (2000). NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 28–38. 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirin SR, Rogers-Sirin L, Cressen J, Gupta T, Ahmed SF, & Novoa AD (2015). Discrimination-related stress effects on the development of internalizing symptoms among Latino adolescents. Child Development, 86, 709–725. 10.1111/cdev.12343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, Rose RA, & Bacallao M (2010). Influence of risk factors and cultural assets on Latino adolescents’ trajectories of self-esteem and internalizing symptoms. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 41, 133–155. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0157-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein GL, Gonzalez LM, Cupito AM, Kiang L, & Supple AJ (2015). The protective role of familism in the lives of Latino adolescents. Journal of Family Issues, 36, 1255–1273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein GL, & Polo AJ (2014). Parent–child cultural value gaps and depressive symptoms among Mexican American youth, Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23, 189–199. 10.1007/s10826-013-9724-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein GL, Supple AJ, Huq N, Dunbar AS, & Prinstein MJ (2016). A longitudinal examination of perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms in ethnic minority youth: The roles of attributional style, positive ethnic/racial affect, and emotional reactivity, Developmental Psychology, 52, 259–271. 10.1037/a0039902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH, Gonzales N, Tsai KM, & Fuligni AJ (2015). Mexican American adolescents’ family obligation values and behaviors: Links to internalizing symptoms across time and context. Developmental Psychology, 51, 75–86. 10.1037/a0038434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres SA, & Santiago CDC (2018). Stress and cultural resilience among low-income Latino adolescents: Impact on daily mood. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 24, 209–220. 10.1037/cdp0000179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gonzales-Backen MA, & Guimond AB (2009). Latino adolescents’ ethnic identity: Is there a developmental progression and does growth in ethnic identity predict growth in self-esteem? Child Development, 80, 391–405. 10.1111/j.14678624.2009.01267.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, & Updegraff KA (2007). Latino adolescents’ mental health: Exploring the interrelations among discrimination, ethnic identity, cultural orientation, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms. Journal of adolescence, 30, 549–567. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, McHale SM, Zeiders KH, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Perez-Brena NJ, Wheeler LA, & Rodríguez De Jesús SA (2014). Mexican-American adolescents’ gender role attitude development: the role of adolescents’ gender and nativity and parents’ gender role attitudes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 2041–53. 10.1007/s109640140128-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, Umaña-Taylor AJ, McHale SM, Wheeler LA, & Perez-Brena NJ (2012). Mexican-origin youth’s cultural orientations and adjustment: Changes from early to late adolescence. Child Development, 83, 1655–1671. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01800.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Census Bureau (June, 2017). Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex, Age, Race, and Hispanic Origin for the United States and States: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Vachon DD, Krueger RF, Irons DE, Iacono WG, & McGue M (2017). Are alcohol trajectories a useful way of identifying at-risk youth? A multiwave longitudinal-epidemiologic study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 56, 498–505. 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Zhang Z, McArdle JJ, & Salthouse TA (2009). Investigating ceiling effects in longitudinal data analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 43, 476–496. 10.1080/00273170802285941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Shirtcliff EA, & Marceau K (2008). Disorders of childhood and adolescence: Gender and psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 275–303. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiders KH, Updegraff KA, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Wheeler LA, Perez-Brena NJ, & Rodríguez SA (2013). Mexican-origin youths’ trajectories of depressive symptoms: The role of familism values. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, 648–654. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.