Abstract

Objective. To develop a model system for involving patients and caregivers in curriculum development of mental health education in an undergraduate pharmacy program.

Methods. Purposive recruitment was used to convene a focus group of nine people with experience in using mental health services from either the patient or caregiver perspective. Group members were asked about their experience with using pharmacy services and their suggestions for enhancement of the undergraduate curriculum. Thematic analysis was conducted independently by two researchers.

Results. Patients and caregivers believed that pharmacists could contribute to the care of people who experience mental health conditions by supporting shared decision making, providing information, actively managing side effects of psychotropic medication, and conducting regular medication review. Subjects suggested that the pharmacy undergraduate curriculum should introduce mental health from the beginning, include self-care for students, integrate mental and physical health education, and enhance students’ communication skills. The curriculum should include broader issues relevant to mental health beyond the use of medication, such as stigma, the recovery approach, and interprofessional cooperation. These changes could support graduates in engaging proactively with people experiencing mental health difficulties.

Conclusion. Involving patients and caregivers in the design of an undergraduate pharmacy curriculum in mental health resulted in a more person-centered and student-centered approach to mental health education at our university. Ultimately, the changes made to the undergraduate curriculum will improve the ability of pharmacy graduates to better meet the needs of patients.

Keywords: Pharmacy, education, mental health, curriculum, patient and public involvement

INTRODUCTION

Patient and public involvement in the provision of health care can lead to better care-related outcomes.1-5 Involvement means actively working with members of the public (patients, their relatives, or members of the general public) as distinct from “engagement” (where information and knowledge are shared with the public) and “participation” (where people take part in education).6 The World Health Organization (WHO) has described Integrated People Centered Health Services (IPCHS) as “putting the needs of communities, not diseases, at the center of health systems and empowering people to take charge of their own health.”1 The IPCHS vision describes the creation of an enabling environment where people and communities can work together, being actively engaged at all levels within the health system. At an individual level, the concept of medicine optimization has shifted the focus from the systems and process of medication use to the outcomes that matter most to individuals by using a collaborative approach that includes shared decision-making.4 Therefore, academic, training and research institutions have an important role to play in developing new professional curricula for a health workforce that can deliver person-centered services, reflective of the needs and values of patients and caregivers. To do this effectively, people and communities must be enabled to contribute meaningfully to health professions education.1,2,7-9

Historically, mental illnesses such as schizophrenia were considered chronic and severely disabling with little hope of improvement or reintegration into society. These perceptions were challenged by those with “lived experience” with mental illness, leading to a new understanding of recovery as an individual journey to bring meaning and purpose to life even if symptoms remain.10,11 Components of recovery include finding and maintaining hope, reestablishment of a positive identity, building a meaningful life, and taking responsibility and control.12 The recovery approach now underpins mental health policy internationally.13-15 In recovery, the narratives, opinions, and experiences of patients are recognized as being valuable and complementary to an evidence-based approach.13 Patient and public involvement is therefore essential in mental health education for health care professionals, with recovery-focused teaching methods (such as contact-based learning and sharing personal stories of recovery) having a positive impact on professional attitudes toward those experiencing mental illness.16-19

Pharmacists have an important contribution to make to the delivery of mental health services.20 Medicines are frequently used as a care option in mental health, and many of these medicines are associated with side effects and poor adherence.21 Studies suggest that pharmacists are less confident in providing mental health care than physical health care.22-25 One reason for this is that undergraduate curricula are largely theoretical and offer few opportunities to engage with people experiencing mental health difficulties.22,26 A review by Rutter and colleagues of the mental health curriculum at 19 schools of pharmacy in the United Kingdom found that, while common mental health conditions were taught in detail, the broader social aspects of mental health, such as the impact of stigma, was taught by just five of the 19 schools.22 Experiential learning opportunities were offered by a third of the UK schools. In the United States, Cates and colleagues found that there was considerable variation between schools with regard to the way psychiatric topics were taught. While 46 of the 48 colleges surveyed offered an advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE) in mental health this was offered as an elective component in 44 of the schools with a mean enrolment of only 20.2% of all students (range of 3% to 60%).27

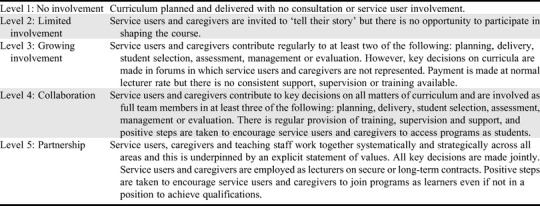

Frameworks have been devised to allow the characterization of the degree of patient involvement in health professions education through a spectrum from minimal passive involvement to an active, full partnership approach.7,28-31 Tew and colleagues, for example, described “the ladder of involvement” with five levels at which patients can contribute to education, ranging from “no involvement” to “full partnership” (Table 1). Although this framework was developed in the context of mental health education, it can be applied across all education programs for health professionals and may be used as a way to monitor patient and public involvement in education programs.8 Systematic reviews of the extent and type of patient and public involvement in education have found few examples of an engaged partnership approach at the level of curriculum design.8,19,32 Moreover, Spencer and colleagues’ systematic review of patient and public involvement in universities in the United Kingdom found that driving patient and public involvement in education was based on individual enthusiasm for projects rather than a management-led approach by the universities, and that there is a need to describe more clearly in the literature how patients are involved in education.8 Accreditation bodies are increasingly requiring evidence of patient and public input into education.33-36 However, there is a need for more research into how we involve patients in pharmacy education. Patient and public involvement at the level of undergraduate pharmacy curriculum design, for example, has not been extensively explored in the literature.8,37

Table 1.

Tew’s Ladder of Involvement in Mental Health Education7

In this study, we sought to involve patients and caregivers in the development of the mental health component of the Master of Pharmacy (MPharm) curriculum at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI). Prior to 2015, pharmacist education in Ireland involved completing a four-year honors bachelor degree program, with practice-based experience occurring in the fifth year and leading to an award at the masters level and registration with the professional body.38 Following the recommendations of the Pharmacy Education and Accreditation Reviews Project (PEARS),39 undergraduate education is now delivered as a five-year master’s program, with workplace placements integrated within the academic program. This transition offered us the opportunity to develop patient and public involvement by consulting patients and caregivers regarding the curriculum. Our hypothesis was that the views of the focus group would help improve the way in which mental health education was delivered to undergraduate pharmacy students by drawing on patients’ experiences of living with mental health conditions and their previous experience with pharmacy services. We hoped to identify at least two new ideas offered by the focus group that could be implemented in the curriculum. This exercise was part of a longitudinal mixed methods study evaluating the impact of changes to the MPharm curriculum on graduates’ confidence in caring for people with mental health conditions, and is considered a pilot initiative with the intention of developing patient and public involvement across other aspects of the pharmacy program.

METHODS

The RCSI developed a unique Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with a psychiatric teaching hospital, Saint John of God Hospital (SJOGH). The memorandum aligned the vision statements of both organizations and included a commitment to the core principles of recovery,20 patient activation,3 and medicines optimization.4 The common vision of the organizations was to improve the undergraduate pharmacists’ curriculum in mental health through the traditional means of clinical placements and practice-based educators, development of novel learning experiences, and facilitation of patient and caregiver involvement.

We chose qualitative methodology to explore the views of patients and caregivers regarding pharmacy services and to elicit their opinions on how the content and delivery of the MPharm curriculum could improve those services. The focus group method allows participants to interact with each other, sharing ideas and experiences and facilitating in-depth exploration of the topic.40 Focus groups are commonly used in health care education41 and have been used elsewhere to assess service needs and guide program development.40 Ethics approval was received from the Saint John of God Hospitaller Ministries Research Ethics Committee and the RCSI Research Ethics Committee.

A purposive recruitment approach was used that involved the selection of participants in a strategic manner to ensure they had experiences relevant to the study.42 Patients and caregivers were invited to participate through several voluntary, peer support, and advocacy organizations. The organizations were chosen by the researchers so that participants would have experience of a range of mental health conditions, be users of public and private mental health services, have advocacy experience and come from diverse geographic locations. Information about the aim and objectives of the study was circulated through the organizations’ networks, and volunteer study participants were sought to represent their organizations. All of the patients and caregivers provided written consent to participate in the study.

The focus group was facilitated by the lead investigator. A senior academic involved in curriculum development was also present. A semi-structured topic guide was used to ensure the focus group was conducted in a timely manner and that the research questions were addressed. Participants were first asked to describe their experience of pharmacy services and how they thought a pharmacist could contribute to mental health care. The outline of the proposed new MPharm curriculum was presented and explained. The participants were asked if they had views on how the curriculum could prepare pharmacists to deliver the desired services. Key concepts raised during the discussion were noted on a flip chart and the facilitator invited other members of the group to agree or disagree. The focus group proceedings were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

The analytic approach was deductive and based on our hypothesis that the views of the participants could enhance the delivery of mental health education for undergraduate pharmacists. The purpose of the analysis was to identify key concepts, including important experiences and ideas that were relevant to the research question. The data were analyzed for anticipated and emergent themes. Braun and Clarkes method of thematic content analysis was used.43 Following familiarization with the data, initial codes were generated and data that were relevant to each code were collated. Coded data were then grouped into themes which, following further review, were defined and named. Portions of the data were extracted to illustrate key themes. Two researchers, one of whom was not present during the focus group, independently analyzed the data. Differences in opinion regarding the data analysis were resolved through discussion.

Following the analysis of feedback from service users and caregivers regarding the new MPharm curriculum, a number of modifications were made. A review of relevant literature was conducted to identify additional evidence to support the suggestions for change to the MPharm curriculum that were identified through the focus group discussions. Therefore, each final recommendation had been generated through the experience of patients and caregivers and also had an evidence base in the literature. Participants were subsequently contacted by e-mail to inform them of the recommendations that were identified from the study, facilitate further input, and thank them for their time and expertise. None of the participants added any further comments following the focus group.

RESULTS

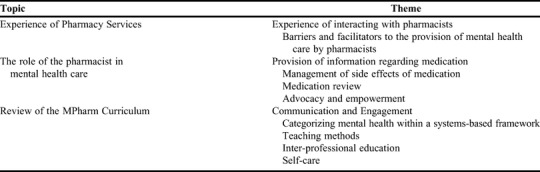

The focus group consisted of nine people: four men and five women. Two were users of the private health care system, while the other seven used public health services. Three members of the group were caregivers of an individual with severe and enduring mental health conditions and six had used mental health services themselves. The patient representatives had experience caring for a person with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, alcohol use disorder, and/or anorexia nervosa. The themes and subthemes derived from the data are listed in Table 2. Quotations chosen to illustrate themes are listed in Appendix 1.

Table 2.

Themes Derived From Input Provided by a Focus Group of Mental Health Patients and Caregivers Who Discussed Pharmacy Education and the Role of Pharmacists in Mental Health Care

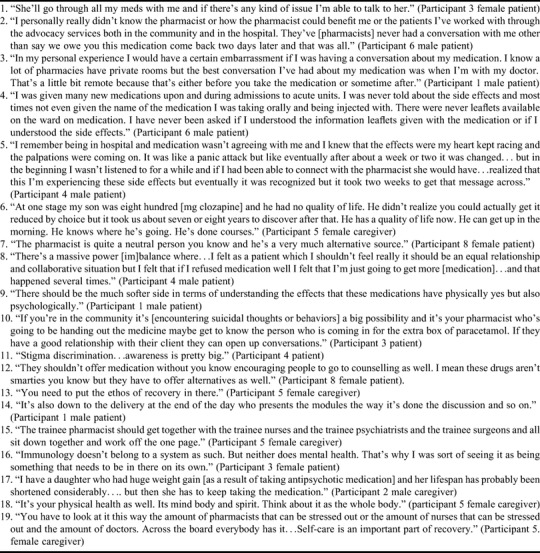

The participants in the focus group had varied experiences with pharmacy services. Of the nine participants, two (one patient and one caregiver) described having a good professional relationship with a local community pharmacist, and one other participant (a caregiver) was aware of a mental health pharmacist who worked in a clozapine clinic (Appendix 1, quotation 1). The remainder of the group described few interactions with pharmacists despite frequently using pharmacy services to obtain medications (Appendix 1, quotation 2).

Concerns about lack of confidentiality in the pharmacy setting was discussed by the participants as a potential barrier to accessing mental health care. All pharmacies in Ireland are required by law to have a consultation room. While some were aware of the presence of consultation rooms, only two participants (one patient and one caregiver) described having used this facility in the past. According to the focus group members, stigma was a significant issue for those using medicines to support recovery from mental health difficulties, and they felt that pharmacists should be mindful of this when supplying medicines to these patients (Appendix 1, quotation 3).

Based on their experiences with mental health care, focus group members suggested that the pharmacist could be an effective member of the multidisciplinary team. Pharmacists could proactively provide reliable, accessible information with regard to medication. Participants in the group felt that they were not given the information they required about the indications for the medications they were prescribed or about the potential adverse effects of the medication. They expressed a desire for information that was relevant to them and unbiased in nature (Appendix 1, quotation 4). Caregivers felt that they also required information about medication so that they could be more informed as to how to support their family member in recognizing and managing side effects.

The impact and experience of medication side effects was a significant concern to all those who participated in the focus group. Two participants described experiences where they felt they were not listened to when coping with side effects and that a pharmacist could potentially have recognized their experiences as side effects to medication at an earlier stage. Three participants felt that expressing their concerns about side effects would be seen as argumentative or a symptom of their mental health problem rather than a genuine adverse effect of the medication requiring attention. The pharmacist could also explain the need for monitoring parameters and the potential to avoid or manage side effects before they became problematic (Appendix 1, quotation 5).

Patients and caregivers want regular medication reviews, with consideration given to reducing doses or discontinuing medications. This would ensure ongoing attention to the balance between the benefits and risks of medication for the individual (Appendix 1, quotation 6). A pharmacist could facilitate regular medication review to help the patient optimize the use of medication with the goal of improving the person’s quality of life.

Participants in the group said they would like to be more involved in the decision-making process with regards to the choice of and need for medication. Pharmacists could facilitate this kind of engagement by providing the patient and/or caregiver with appropriate information to assist them in shared decision-making. In this context, the pharmacist was described as an advocate, independent of mental health services, with the potential to facilitate communication between the patient and members of the multidisciplinary team (Appendix 1, quotations 7 and 8). Therefore, despite previous lack of engagement with pharmacists, participants recognized the potential contribution that pharmacists could make to their care.

The focus group endorsed patient and caregiver input into teaching undergraduate pharmacy students as a means of encouraging engagement and breaking down barriers. Innovative experiential learning opportunities could be sought. One example was to invite students to attend a peer support group for caregivers of people who have been diagnosed with schizophrenia. Participants suggested that the content of the course could be expanded to include more information on diagnoses, for example, eating disorders, dual diagnosis, child and adolescent mental health, and the importance of early intervention. One patient suggested that students also need to gain an understanding of the psychological impact of using medications (Appendix 1, quotation 9).

The focus group members were made aware of the available training programs that supported engagement around mental health and, specifically, suicide prevention. Mental Health First Aid (MHFA),44 Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST)45 and safeTALK46 were suggested as means of training pharmacy students. Participating in brief educational interventions such as these could improve pharmacy students’ communication skills and encourage them to initiate conversations about mental health with patients (Appendix 1, quotation 10). One participant suggested that pharmacy students’ communication skills could be further enhanced through role play.

The focus group emphasized the need for health care professionals to understand broader aspects of mental health care such as the impact of stigma and alternatives to medication (Appendix 1, quotations 11 and 12). Efforts should be made not only to tackle any stigmatizing views that the pharmacy students may hold themselves but also to teach pharmacists to fulfil their role in educating the public about mental illness. This would inform the pharmacist’s approach to confidentiality in the community pharmacy setting. There was consensus from the group that the ethos of recovery should underpin teaching (Appendix 1, quotation 13). This theme emerged through the discussions, was initially suggested by a female caregiver, and was supported by other participants. In practice, this means introducing students to what is meant by recovery in mental health care and ensuring the “patient’s voice” informs clinical teaching. A participant in the study felt that the characteristics of the person who delivers the teaching to students was important as this would have an impact on learning and the impression of mental health care that the students developed (Appendix 1, quotation 14).

There was an acknowledgement that community pharmacists work in isolation from mental health services and general practitioners, which is a barrier to meaningful interactions regarding medication use. Thus, patients and caregivers having access to pharmacists in the hospital setting would be a positive development that would help initiate their relationship with the profession. One participant suggested that health care professionals of different disciplines should learn together in order to help them better practice together as qualified clinicians (Appendix 1, quotation 15).

In the MPharm curriculum, mental health was a component of the Central Nervous System module delivered in the second year of the program. The group had mixed opinions about placement of the module within the course and pointed out that mental health does not easily fit within any particular body system (Appendix 1, quotation 16). Participants were concerned at the lack of a cohesive approach to mental and physical health care in the health care system. All participants were acutely aware that people experiencing mental health problems have poorer outcomes with physical health problems, leading to a reduced life expectancy of up to 20 years (Appendix 1, quotation 17). When asked how pharmacists might contribute to improving this, a participant suggested that if a pharmacist were part of the multidisciplinary team, he or she could support the management of side effects and the physical health implications of using psychiatric medications. From the education perspective, the consensus was that mental health should be more integrated into the physical health aspects of the curriculum (Appendix 1, quotation 18).

The focus group participants were particularly concerned with the effects of stress and strain on students themselves. Participants felt that mental health should be introduced from the beginning of the curriculum and not necessarily with just a focus on patient illness but also on student wellness. They felt that students should be taught about looking after their own mental health. There was general agreement with one participant’s suggestion that self-care should be part of the curriculum in addition to any student support services that were available (Appendix 1, quotation 19). Wellness and Recovery Action Planning (WRAP)47 was suggested by a female service user and trained WRAP facilitator as one way of achieving this.

DISCUSSION

This paper describes a pilot project to involve patients and caregivers in curriculum design for undergraduate pharmacy students. The initiative supports the School of Pharmacy’s goal to advance along Tew’s ladder of service user involvement from level 2 to level 3 (Table 1). The ideas for change generated by the focus group demonstrate the value of their input and are supported by research (Table 3). This study was part of a joint initiative by the RCSI and a psychiatric teaching hospital, which includes the delivery of mental health lectures in therapeutics by practicing pharmacists, experiential learning opportunities, multidisciplinary input into education, and co-facilitated teaching with pharmacists and patients. The MoU between the two organizations outlines a commitment to involve and consult with patients and caregivers on an ongoing basis, thus supporting sustainability. A longitudinal study is underway to assess the effects of the mental health program on the confidence of new graduates to deliver mental health care.

Table 3.

Changes Made to the Curriculum for the Master of Pharmacy Program as a Result of Patient and Caregiver Input During a Focus Group

The views of our focus group were reflective of international research demonstrating a need for more effective engagement regarding medication use in mental health care.18,21,48 While pharmacists are an accessible resource for patients and caregivers, there is a lack of awareness among users of the mental health services regarding the professional services that can be offered. For example, in a survey of Irish patients, only 7% of the 1519 respondents identified the pharmacist as a source of information about medication, echoing the findings of this study.49

The suggestions for the MPharm curriculum made by the focus group target aspects of the patient experience that could be improved, particularly in relation to engagement, reducing stigma, and promoting hopeful, person-centered interactions in line with the recovery ethos. A study by Wheeler and colleagues concluded that positive relationships with knowledgeable staff are fundamental to reducing stigma and promoting engagement in the pharmacy setting.50 Further, pharmacists need to have a real understanding of the lived experiences of patients and caregivers. Attitudes towards the provision of mental health care can be improved by engaging positively at an undergraduate level.18,51,52 This study adds to the body of evidence by taking this involvement beyond the classroom to the level of curriculum development.

Participants in the focus group were concerned for the wellbeing of students and practicing pharmacists. They strongly endorsed the inclusion of self-care in the curriculum, emphasizing that no one is immune to the effects of mental illness. This recommendation is particularly powerful coming from those with personal experience with mental health difficulties. Stress and burnout is common among health care professionals, who are often reluctant to seek help when in distress.53,54 The development of self-care skills as part of the curriculum for undergraduate pharmacists requires further exploration.

The extent to which universities engage in PPI varies widely.8,19 When involved, the role that patients play in education is traditionally to provide a passive illustration of a specific condition in a health care setting.8 Advancing this role means that patients can not only contribute to education by giving presentations, facilitating seminars, or serving as a tutor, but also make a valuable contribution to activities such as student selection, assessment, curriculum development, and governance.8,19,28,32,33,55 A report published by the Mental Health Commission of Ireland showed that of the 137 health care courses relevant to mental health services, only 37% (n=50) involved students interacting with patients.9 Of the 50, only 34% (n=17) and 24% (n=12) had patient involvement in course design and collaborative research, respectively. However, the pharmacy profession was not specifically considered in this study. A comprehensive review of patient involvement in health care education by the Healthcare Foundation found few examples of patient input into curriculum design.8

There is little published evidence in relation to patient and public involvement in curriculum development for pharmacists, particularly at the undergraduate level. Examples include Rutter and colleagues who found that only four of the 19 schools of pharmacy in the United Kingdom engaged directly with individuals who had experience with mental health problems, and that this was by inviting patients to tell their story in a classroom or workshop setting.22 The Comensus project at the University of Lancaster aims to involve patients in all aspects of teaching, research, and strategy.56 Pharmacy students benefit from this through participation in patient-led workshops. At the University of Manchester, a Patient and Public Committee offers strategic advice on undergraduate and postgraduate pharmacy education.37

Wheeler and colleagues used the results of a needs assessment to incorporate the views of patients and caregivers into the design of a postgraduate course in mental health pharmacy.50 This involved in-depth individual semi-structured interviews, focus groups, and brief structured exit interviews conducted within 72 hours of a pharmacy visit. Data were gathered regarding specific medication needs, expectations of community pharmacy, and perceptions of medication taking. Seventy-four patients and caregivers participated in in-depth consultation and 211 in exit interviews. The results of this needs assessment combined with a needs assessment for pharmacists, consultation with key stakeholders, and a literature review, provided the evidence base for the development of the continuing education program. The conclusion from this process was that the goals of the program should be to address stigmatizing attitudes, enhance knowledge of high prevalence illnesses (eg, anxiety) and improve the confidence and communication skills of pharmacy staff members so they could effectively engage with people who have a mental health condition.

This study had some limitations. We conducted a single focus group for the purpose of identifying some specific enhancements that could be made to the MPharm curriculum. It is possible that data saturation was not reached and that further focus groups could have generated more ideas for improvement. The people who participated in this initiative were self-selected and may not have had views that were representative of patients and caregivers in general. Participants did not receive any training. However, all participants were experienced advocates who had contributed at strategic and policy levels on behalf of their organizations in the past. Furthermore, the purpose of their involvement in the focus group was made clear during the recruitment process. Williamson and colleagues note that if you consult the “right” patients, the results can be valuable. Furthermore, as active members of patient organizations, our participants were aware of the experiences of other people like themselves.57 Engaging with existing networks is a pragmatic way of recruiting individuals for the purposes of curriculum review.58 The experiences of the participants in this focus group in relation to the use of medication for mental health conditions echo the results of international studies,18,48 supporting the validity of the data and the generalizability of the results.

Several reviews of PPI in education have called for the publication of research and the sharing of initiatives.8,30,31 This was a pilot involvement project applicable to one aspect of the pharmacy curriculum. Although more work is required before we a see fuller partnership in curriculum design across the undergraduate program, this was a replicable first step with meaningful outcomes. A framework and strategy for future involvement is required, including the necessary infrastructure to ensure sustainability.33,58 The MoU with the psychiatric teaching hospital is one such support. Initiatives such as ours have been shown to make students more aware of the needs of vulnerable patients.33 The suggestions made by the focus group should be considered for undergraduate education of other health care professions.

CONCLUSION

This study describes a qualitative methodology for involving patients and caregivers in curriculum review. We hypothesize that the outcomes of this project will support graduates in providing mental health services that are person-centered and relevant to the needs of patients and caregivers. Ultimately, the objective of PPI is to improve the patient experience of mental health care in the pharmacy setting. While this is difficult to evaluate, the current focus of our longitudinal evaluation is in relation to the confidence and attitudes of the students towards providing mental health care, given that improving students’ attitudes has been shown to increase willingness to engage with people who have mental health conditions.23

Appendix 1.

Quotations Chosen to Illustrate Themes Derived from a Focus Group of Patients and Caregivers on the Role of Pharmacy Students and Pharmacists in Mental Health Care

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organisation. WHO Framework on Integrated People Centred Health Services. 2016. www.who.int/servicedeliverysafety/areas/people-centred-care/en/. Accessed November 1, 2019.

- 2.Realising the Value. Ten Key Actions to put People and Communities at the Heart of Health and Wellbeing. 2016. www.health.org.uk/collection/realising-value. Accessed November 1, 2019.

- 3.Hibbard J, Giburt H. Supporting People to Manage their Health. An Introduction to Patient Activation. The Kings Fund. www.thekingsfund.org.uk. Published 2014. Accessed November 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Medicines optimisation: Helping patients to make the most of medicines. London: 2013. https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Policy/helping-patients-make-the-most-of-their-medicines.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Edwards A, et al. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS: lessons from the MAGIC Programme. BMJ. 2017;357:1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behan C, Masterson S, Clarke M. Systematic review of the evidence for service models delivering early intervention in psychosis outside the stand‐alone centre. Early Intervention Psych. 2017;11(1):3-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tew J, Gell C, Foster S. Learning from experience: involving service users and carers in mental health education and training. NIMHE/Trent Workforce Development Corporation. Trent; 2004. http://www.swapbox.ac.uk/692/1/learning-from-experience-whole-guide.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spencer J, Goldphin W, Karpenko N, Towle A. Can patients be teachers? Involving patients and service users in healthcare professionals education. Healthcare Foundation. United Kingdom; 2011. http://www.health.org.uk/publication/can-patients-be-teachers. Accessed November 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mental Health Commission. Current education and training available for professionals working in mental health services in the Republic of Ireland. Dublin; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slade M. Personal Recovery and Mental Illness: A Guide for Mental Health Professionals. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anthony WA. Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehab J. 1993;16(4):11. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shepherd G, Boardman J, Slade M. Making Recovery a Reality . Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health; Sainsbury; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mental Health Division. A National Framework for Recovery in Mental Health. Health Services Executive; Dublin; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Boutillier C, Leamy M, Bird VJ, Davidson L, Williams J, Slade M. What does recovery mean in practice? a qualitative analysis of international recovery-oriented practice guidance. Psych Serv. 2011;62(12):1470-1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frost BG, Tirupati S, Johnston S, et al. An Integrated Recovery-oriented Model (IRM) for mental health services: evolution and challenges. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Repper J, Breeze J. User and carer involvement in the training and education of health professionals: a review of the literature. Inter J Nurs Studies. 2007;44(3):511-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patten SB, Remillard A, Phillips L, et al. Effectiveness of contact-based education for reducing mental illness-related stigma in pharmacy students. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12(1):120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feeney L, Jordan I, McCarron P. Teaching recovery to medical students. Psych Rehab J. 2013;36(1):35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins A, Creaner M, Maguire G, et al. Current Education/Training Available for Professionals Working in Mental Health Services in the Republic of Ireland. Mental Health Commission. Dublin: 2010. http://www.mhcirl.ie/File/CET.pdfAccessed November 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker E, Fee J, Bovingdon L, et al. From taking to using medication: recovery-focused prescribing and medicines management. Advances Psych Treat. 2013;19(1):2-10. [Google Scholar]

- 21.García S, Martínez-Cengotitabengoa M, López-Zurbano S, et al. Adherence to antipsychotic medication in bipolar disorder and schizophrenic patients: a systematic review. J Clin Psychopharmacology. 2016;36(4):355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rutter P, Taylor D, Branford D. Mental health curricula at schools of pharmacy in the United Kingdom and recent graduates’ readiness to practice. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(7):Article 147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Reilly CL, Bell JS, Kelly PJ, Chen TF. Exploring the relationship between mental health stigma, knowledge and provision of pharmacy services for consumers with schizophrenia. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2013;11(3): e101-e109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liekens S, Smits T, Laekeman G, Foulon V. Pharmaceutical care for people with depression: Belgian pharmacists’ attitudes and perceived barriers. Inter J Clin Pharm. 2012;34(3):452-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodman CS, Smith TJ, LaMotte JM. A survey of pharmacists' perceptions of the adequacy of their training for addressing mental health–related medication issues. Mental Health Clinician. 2017;7(2):69-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bell JS, Johns R, Rose G, Chen TF. A comparative study of consumer participation in mental health pharmacy education. Ann Pharmacotherapy. 2006;40(10):1759-1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cates ME, Monk-Tutor MR, Drummond SO. Mental health and psychiatric pharmacy instruction in US colleges and schools of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(1):Article 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Towle A, Bainbridge L, Godolphin W, et al. Active patient involvement in the education of health professionals. Med Educ. 2010;44(1):64-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spencer J, Blackmore D, Heard S, et al. Patient‐oriented learning: a review of the role of the patient in the education of medical students. Med Educ. 2000;34(10):851-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Regan de Bere S, Nunn S. Towards a pedagogy for patient and public involvement in medical education. Med Educ. 2016;50(1):79-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirst B, Padfield P, Corner L, et al. Pathways to Embed Patient and Public Involvement in Healthcare Scientist Training Programmes. National Health Service: Health Education England; Manchester: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan A, Jones D. Perceptions of service user and carer involvement in healthcare education and impact on students’ knowledge and practice: a literature review. Med Teach. 2009;31(2):82-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.General Medical Council. Patient and Public Involvement in Undergraduate Medical Education. United Kingdom; 2011. http://www.gmc-uk.org/Patient_and_public_involvement_in_undergraduate_medical_education___guidance_0815.pdf_56438926.pdfAccessed November 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cates ME, Burton AR, Woolley TW. Attitudes of pharmacists toward mental illness and providing pharmaceutical care to the mentally ill. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39(9):1450-1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fadden G, Shooter M, Holsgrove G. Involving carers and service users in the training of psychiatrists. The Psychiatrist. 2005;29(7):270-274. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDaid D, Park A-L, Iemmi V, Adelaja B, Knapp M. Growth in the use of early intervention for psychosis services: An opportunity to promote recovery amid concerns on health care sustainability. London: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grimes L, Shaw M, Cutts C. Patient and public involvement in the design of education for pharmacists: is this an untapped resource? Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2013;5(6):632-636. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strawbridge J, Barlow J, O’Leary A, et al. Design and evaluation of a new national pharmacy internship programme in Ireland. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;83(4):Article 6678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson K, Langley C. Pharmacy Education and Accreditation Reviews (PEARs) Project. Report commissioned by the Pharmaceutical Society of Ireland. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research . Sage publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stalmeijer RE, McNaughton N, Van Mook WN. Using focus groups in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 91. Med Teach. 2014;36(11):923-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braun V, Clarke V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners . Sage; London: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77-101. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mental Health First Aid Ireland. Standard Mental Health First Aid Programme. www.mhfaireland.ie. Accessed November 1, 2019.

- 45.Living Works Education. Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST). https://www.livingworks.net/asist. Accessed November 1, 2019.

- 46.Living Works Education. safeTALK Training. https://www.livingworks.net/safetalk. Accessed November 1, 2019.

- 47.Copeland M. Wellness and Recovery Action Planning (WRAP). http://mentalhealthrecovery.com/. Accessed November 1, 2019.

- 48.Healthcare Commission. The pathway to recovery. A review of acute inpatient mental health services. Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection; London: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Reilly CL, Bell JS, Chen TF. Mental health consumers and caregivers as instructors for health professional students: a qualitative study. Soc Psych Psych Epid. 2012;47(4):607-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wheeler A, Fowler J, Hattingh L. Using an intervention mapping framework to develop an online mental health continuing education program for pharmacy staff. J Contin Educ Health. 2013;33(4):258-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O'Reilly CL, Bell JS, Kelly PJ, Chen TF. Impact of mental health first aid training on pharmacy students’ knowledge, attitudes and self-reported behaviour: a controlled trial. Aus NZ J Psych. 2011;45(7):549-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Einat H, George A. Positive attitude change toward psychiatry in pharmacy students following an active learning psychopharmacology course. Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32(6):515-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dyrbye LN, Eacker A, Durning SJ, et al. The impact of stigma and personal experiences on the help-seeking behaviors of medical students with burnout. Acad Med. 2015;90(7):961-969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Burnout among health care professionals: A call to explore and address this underrecognized threat to safe, high-quality care. NAM Perspectives; Washington: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923-1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Becket G, Wilson S, Greenwood K, Urmston A, Malihi-Shoja L. Involving patients and the public in the delivery of pharmacy education. Pharm J. 2014;292(7813):585 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Williamson C. ‘How do we find the right patients to consult?'. Quality in Primary Care. 2007;15(4). [Google Scholar]

- 58.O'Keefe M, Jones A. Promoting lay participation in medical school curriculum development: lay and faculty perceptions. Med Educ. 2007;41:130-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karwig G, Chambers D, Murphy F. Reaching Out in College: Help-Seeking at Third Level in Ireland, ReachOut Ireland; Dublin: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mayberry KM, Miller LN. Incidence of self-reported depression among pharmacy residents in Tennessee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(8):Article 5960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burns S, Crawford G, Hallett J, Hunt K, Chih HJ, Tilley PM. What’s wrong with John? a randomised controlled trial of Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) training with nursing students. BMC Psych. 2017;17(1):111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Davies B, Beever E, Glazebrook C. The mental health first aid eLearning course for medical students: a pilot evaluation study. Euro Health Psych. 2016;18(S):861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.El-Den S, Chen TF, Moles RJ, O’Reilly C. Assessing mental health first aid skills using simulated patients: Exploring observed behaviors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2018;82(2):Article 6222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kitchener BA, Jorm AF. Mental health first aid training for the public: evaluation of effects on knowledge, attitudes and helping behavior. BMC Psych. 2002;2(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hadlaczky G, Hökby S, Mkrtchian A, Carli V, Wasserman D. Mental Health First Aid is an effective public health intervention for improving knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour: A meta-analysis. Intern Rev Psych. 2014;26(4):467-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.World Health Organization. Information sheet: premature death among people with severe mental disorders. World Health Organization; http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/info_sheet.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed November 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Naylor C, Das P, Ross S, Honeyman M, Thompson J, Gilburt H. Bringing together physical and mental health. A new frontier for integrated care. The Kings Fund. London; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Appleton A, Singh S, Eady N, Buszewicz M. Why did you choose psychiatry? a qualitative study of psychiatry trainees investigating the impact of psychiatry teaching at medical school on career choice. BMC Psych. 2017;17(1):276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Balen R, Rhodes C, Ward L. The power of stories: using narrative for interdisciplinary learning in health and social care. Soc Work Educ. 2010;29(4):416-426. [Google Scholar]