Abstract

Purpose of review

Men and women differ in the prevalence, pathophysiology and control rate of hypertension in an age-dependent manner. The renal endothelin system plays a central role in sex differences in blood pressure regulation by control of sodium excretion and vascular function. Improving our understanding of the sex differences in the endothelin system, especially in regard to blood pressure regulation and sodium homeostasis, will fill a significant gap in our knowledge and may identify sex-specific therapeutic targets for management of hypertension.

Recent Findings

The current review will highlight evidence for the potential role for endothelin system in the pathophysiology of hypertension within three female populations; (i) postmenopausal women, (ii) women suffering from preeclampsia or (iii) pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Summary.

Clinical trials that specifically address cardiovascular and renal diseases in females under different hormonal status are limited. Studies of the modulatory role of gonadal hormones and sex-specific mechanisms on critically important systems involved, such as ET-1, are needed to establish new clinical practice guidelines based on systematic evidence.

Keywords: sex, endothelin, postmenopausal, preeclampsia, pulmonary hypertension

Introduction

Hypertension affects one in three Americans [1] and is more prevalent in men compared to age-matched premenopausal women [2]. Hypertension is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, which is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in men and women. Despite the availability of numerous antihypertensive medications; hypertension is still not fully managed.

Endothelin-1 (ET-1) is the most potent vasoconstrictor agent discovered to date. It has remarkable long lasting effects on vascular tone [3, 4]. This peptide is composed of a 21 amino acid chain, which is released primarily from endothelial cells. However, other cell types including the epithelial cells also produce the peptide [4]. ET-1 circulating levels reflect its biosynthesis and release from endothelial cells, as well as clearance rates [4, 5]. ET-1 binds to two cell surface G-protein coupled receptors; ET type A (ETA) receptor and ET type B (ETB) receptor. ETA receptors are located mainly on smooth muscle cells. Activation of ETA receptors results in vasoconstrictor, inflammatory and proliferative effects. On the other hand, ETB receptors are located mainly on endothelial and renal epithelial cells. ETB receptor activation to promote vasodilation and natriuresis, although there are limited numbers of ETB receptors on vascular smooth muscle that can contribute to vasoconstriction. ET-1 plays a central role in maintaining body fluid and electrolyte balance. Defects in the capacity of the kidneys to excrete Na+ are a fundamental mechanism involved in the initiation of hypertension [6, 7]. Therefore, it is vital that we broaden our understanding of the varied mechanisms of blood pressure regulation and renal Na+ handling in both sexes hoping to pinpoint sex-specific therapeutic targets for hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases.

Abnormalities of the ET-1 signaling system have been linked to development of hypertension and impaired sodium handling. Inhibition of the ETB receptor function, either pharmacologically or genetically, results in salt-sensitive hypertension [8, 9]. Further, ETB dysfunction is associated with elevated ET-1 levels and ETA receptor activation such that ETA receptor blockers are particularly effective in lowering blood pressure in patients with salt-dependent as well as resistant hypertension [10].

Evidence has emerged that there are sex differences at various levels in the ET-1 signaling pathway including circulating peptide levels and tissue concentrations, receptor expression, receptor function and downstream signaling. We recently reviewed the role of ET-1 in the sexual dimorphism in cardiovascular and renal diseases [11]. In the current review, we will focus on clinically relevant advances and potential future possibilities in targeting ET-1 signaling to regulate blood pressure particularly within the female population, hoping that future clinical studies will target at-risk populations. It is important to note that problems with drug dosing, toxicity, patient selection and study design have contributed to failure of many previous clinical trails for ETA receptor antagonists [12].

ET-1 in postmenopausal hypertension

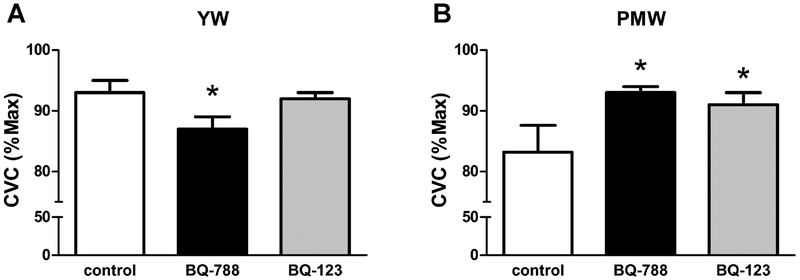

After menopause, the prevalence of hypertension among women increases sharply to levels that equal or surpass those of men implicating an important role for ovarian hormones in cardiovascular and renal protection [13–19]. It is also evident that hypertension is less well controlled in aging women compared to aging men [20]. The mechanisms responsible for elevated blood pressure after menopause is not well understood and it may require multiple drug therapy to treat postmenopausal hypertension. Previous studies suggest that imbalances in the ET-1 signaling pathway may contribute to the etiology of postmenopausal hypertension. Postmenopausal women exhibit elevated plasma ET-1 levels that may contribute to elevated blood pressure and cardiovascular risk in this population [21, 22]. Previous studies have demonstrated that enhanced ET-1 in the circulation may result in endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffness. Hormonal replacement therapy decreased plasma ET-1 in hypertensive postmenopausal women [21, 23]. In addition, exercise decreased blood pressure and plasma ET-1 in postmenopausal hypertensive women [24], suggesting that exercise might be employed as a means of reducing ET-1 and subsequent cardiovascular risks in postmenopausal women. Webb et al. found that short-term intracoronary administration of estradiol resulted in a significant decrease in coronary sinus concentrations of ET-1 in postmenopausal women with coronary artery disease [25]. A recent study has shown that ETB-mediated vasodilatory capacity is decreased in postmenopausal women, compared to young women (Figure 1)[26]. This interesting finding suggests that impaired ETB-mediated vasodilatory function may be responsible, at least in part, for endothelial dysfunction manifested after menopause [26].

Fig. 1.

Recent findings demonstrating differential vascular ETB receptor function in the cutaneous circulation in young women (YW) and post-menopausal women (PMW). Cutaneous vascular conductance (i.e., vasodilatory responses) to local heating were measured during cutaneous microdialysis perfusions of ETB (BQ-788) and ETA (BQ-123) receptor antagonists (*P < 0.05 vs. control.) These findings demonstrate a role for ETB receptors in control of microvascular function that is reversed following menopause. Used with permission from Wenner et al. [60].

Consistent with the data from humans, animal studies have demonstrated that ovariectomy and hormone replacement modulate expression of ETA and ETB receptors in renal tissues [27]. More specifically, ovariectomy significantly decreased renal cortical ETA and ETB receptor expression [27]. This effect was prevented by supplementation of OVX rats with estradiol [27]. On the other hand, ovariectomy increased the expression of ETA and ETB expression in the renal inner medulla and supplementation of OVX rats with estradiol prevented this increase [27]. These findings are particularly relevant because the inner medulla of the kidney produces the largest amounts of ET-1 peptide and has the highest expression of renal tubular ETB receptors [28]. In addition, renal medullary salt loading stimulated natriuresis in intact female and OVX rats. It was further shown that both ETA and ETB receptors contribute to this natriuretic response only in OVX rats, but not intact females [29]. Blockade of ETA and ETB receptors prevented the natriuretic response to renal medullary purinergic receptor activation only in OVX and not intact females [29], suggesting that the renal medullary ET-1 system in OVX rats, a crude model of post-menopause, may play a more important role in renal salt handling compared to intact female rats, which model pre-menopause. In related studies, the endothelial impairment manifested in ovariectomized rats can be prevented by chronic vagus nerve stimulation, through mechanisms that may include ET-1 reduction [30]. In an effort to model of postmenopausal hypertension, Lima et al. [31] used aged spontaneously hypertensive rats to demonstrate that ETA receptor blockade causes an additional reduction in blood pressure, compared to treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor and arachidonic acid metabolism inhibition. This observation supports the notion that postmenopausal hypertension is multifactorial and involves pathophysiological changes in different signaling systems including the ET-1 pathway.

Endothelin receptor A as a therapeutic target for preeclampsia

Preeclampsia is a pregnancy specific syndrome that is associated with elevated blood pressure, increased renal vascular resistance and endothelial dysfunction. Despite being one of the major causes of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality, no specific therapeutic interventions have been developed yet due to incomplete understanding of the mechanisms involved in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia [32, 33]. Preeclampsia is a multisystem disorder involving abnormalities in multiple signaling pathways including the ET-1 system. A recent meta-analysis study of 16 published cohort studies, including 1739 hypertensive cases and 409 controls, revealed that ET-1 plasma concentrations are elevated in hypertensive pregnant women as compared to normotensive controls [34]. Further, umbilical vein concentrations of ET-1 in preeclampsia are higher than in normal pregnancy [35]. In different experimental models of preeclampsia, tissue ET-1 levels were increased in the placenta and kidneys [36].

Growing evidence supports the concept that placental ischemia triggers enhanced ET-1 biosynthesis, which contributes to preeclampsia [37]. Recent data suggest that pharmacological induction of hemeoxygenase-1 or bilirubin decreases ET-1 release in response to placental ischemia [38], thus providing a potential strategy to block this pro-hypertensive pathway in preeclampsia. ET-1 also appears to induce oxidative stress in preeclampsia [39, 40]. Importantly, ETA receptor blockade provides protection against preeclampsia [36, 41–43]. ETA receptor antagonism prevents/reduces the hypertension in many experimental models of preeclampsia, highlighting that ET-1 signaling is a common contributor to elevated blood pressure in pregnancy [44]. However, ETA receptors are essential for fetal growth during the first trimester. Therefore, considering ETA receptor antagonists for preeclampsia would have to be limited until after the first trimester, if at all. Alternatively, development of an ETA receptor antagonist that does not cross the placental barrier would greatly advance the potential utility of ETA receptor blockade in preeclampsia. Thaete et al., reported that the ETA receptor antagonist, ABT-546, has limited access across the placenta from the maternal to the fetal compartment [45]. In this study, the plasma concentration of ABT-546 in the fetal circulation was 2% of those in the maternal circulation [45]. Whether this would be considered an acceptable risk is unclear. Thus, while the results of ETA antagonism in preeclampsia are promising, additional studies are needed to evaluate the benefit risk ratio.

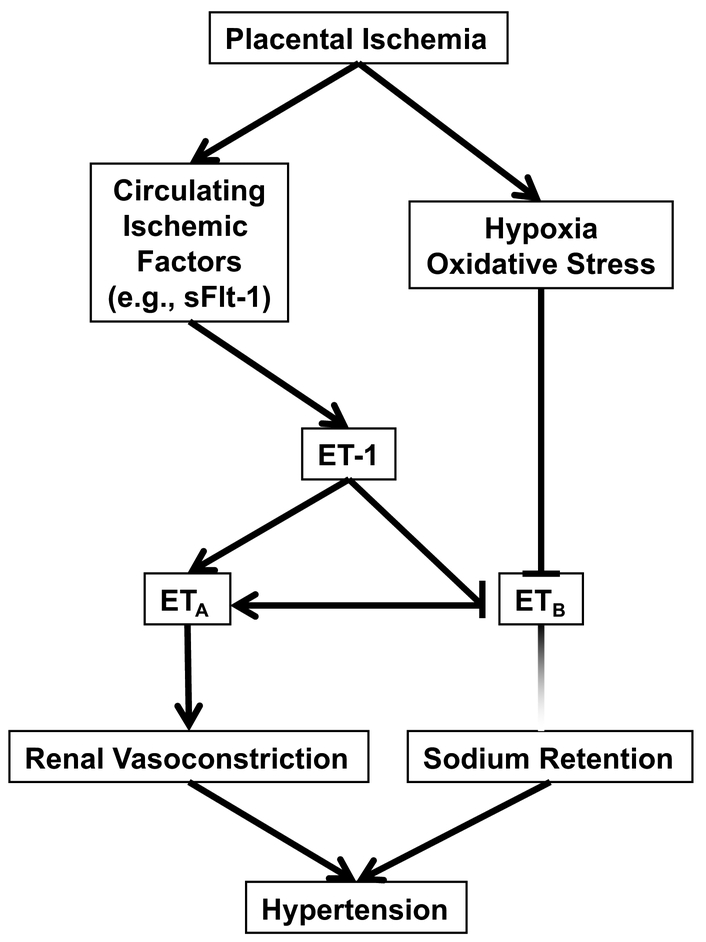

As already discussed, ET-1 may provide a link between placental ischemia and elevated blood pressure in preeclampsia (Figure 2)[36]. The reason for this may be through a link between ET-1 and anti-angiogenic factors. The hypoxic placenta releases anti-angiogenic molecules such as soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt-1) into the circulation [46]. sFlt-1 is a splice variant of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor Flt1 lacking the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains and acts as a potent antagonist of VEGF and placental growth factor [47, 48]. Similar to ET-1, sFlt-1 appears to contribute to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia and may be a predictor for the severity of preeclampsia [32, 49, 50]. Importantly, plasma ET-1 correlates positively with sFlt-1 in preeclampsia-in maternal circulation [51, 52]. This observation strengthens the possibility that ET-1 mediates the pathogenesis of preeclampsia secondary to the anti-angiogenic factors released in response to the hypoxic environment within the placenta [52]. This is further supported by data showing that ETA receptor blockade completely abolished the hypertensive response to sFlt-1 in pregnant rats [41]. These findings suggest that ET-1 contributes to production of sFlt-1.

Fig. 2.

Theoretical scheme for endothelin involvement in pregnancy induced hypertension.

Besides the well-established contribution for ETA to the pathophysiology of preeclampsia, dysfunction of ETB receptors has recently been linked to preeclampsia [38, 53]. Cutaneous vascular responses to ET-1 are normally attenuated by ETB dependent vasodilation that was significantly reduced in previously preeclamptic women postpartum [53]. ET-1 via ETB receptors also appears to impair trophoblast functions such as migration and invasion in human first trimester trophoblasts [54]. The mechanisms behind changes in receptor function need to be resolved in future studies.

Sex differences in the efficacy of ETA receptor antagonists for pulmonary arterial hypertension

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a condition characterized by pulmonary vascular remodeling and increased pulmonary artery pressure leading to right ventricular failure [55]. PAH is a female-predominant disease. However, prognosis is worse in male patients [56]. It is well documented that ET-1 plays a major role in the pathogenesis of PAH through its vasoconstrictor and mitogenic effects. Previous studies showed that plasma and lung ET-1 levels are increased in PAH. ETA receptor antagonists are commonly used as first line therapy for treatment of PAH since 2001 [57]. Currently, three ETA receptor blockers, bosentan, macitentan and ambrisentan, are FDA approved for management of PAH.

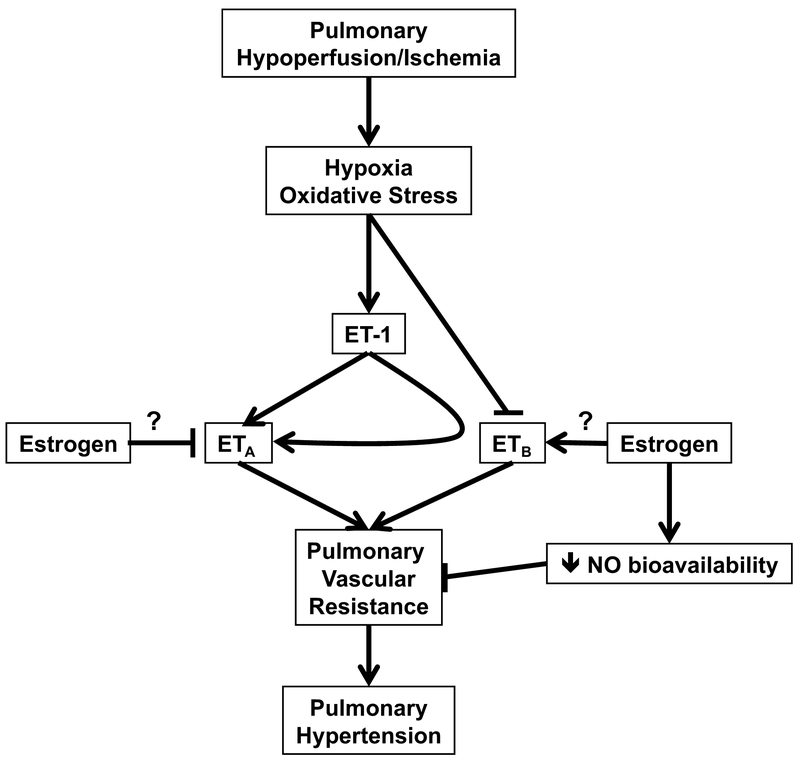

A recent study indicates that women have better improvements of right ventricular functions and hemodynamics following optimal medical therapy [58]. Retrospective studies have pointed to a sex-related discrepancy in the therapeutic response ERA receptor blockers. Gabler at al. analyzed patient data from 1,130 participants enrolled in six randomized placebo-controlled trials of ETA receptor blockers for management of PAH [59]. The authors found that women have greater therapeutic responses to ETA receptor antagonists. These clinical findings suggest that female PAH patients may benefit more from ETA receptor antagonists [60]. On the other hand, men with PAH showed greater improvement in response to phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors compared to women [61]. This sex-related difference in the efficacy of antihypertensive regimens suggests that the molecular mechanisms involved in the pathophysiology of PAH are sexual dimorphic. The robust effect of the female sex predicting better response to ETA receptor blockers and the male sex predicting better response to phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibition can inform personalized treatment decisions. We hypothesize that differential effects on the ETA and ETB receptor systems could explain why females have more frequent risk for pulmonary hypertension, yet not as severe as in males (Figure 3). Future studies addressing sex differences in the therapeutic response to different treatment regimens can provide a foundation to revisit the guidelines for management of PAH to include the sex as a variable.

Fig. 3.

Hypothetical scheme demonstrating the paradoxical effects of estrogen in facilitating less severe pulmonary hypertension and yet being more responsive to ET receptor blockade.

Conclusion

Studies published in recent years generally reinforce the importance of sex and sex hormones in determining quality of life and prognosis of cardiovascular diseases including hypertension. Increasing evidence demonstrates that pathophysiology, manifestations and complications of hypertension differ in men, premenopausal, hormonally supplemented and non-supplemented postmenopausal patients, indicating that female sex hormones play a central role in the maintenance of cardiovascular health in the female population. Thus, the management strategies evaluated in the general population may differ significantly between men, premenopausal female and postmenopausal female patients with and without hormonal replacement therapy. The number of trials that specifically address cardiovascular and renal diseases in females under different hormonal status remains small. When results of needed studies of the modulatory role of gonadal hormones on critically important systems involved in cardiovascular and renal control, such as ET-1 system, and other relevant topics become available, new clinical practice guidelines based on a systematic evidence will need to be developed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (P01 HL0699499 and P01 HL136267), an American Heart Association Strategically Focused Research Network Grant on Hypertension, and a UAB School of Medicine AMC21 Multi-Investigator Planning Grant.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. Dr. Gohar is also affiliated with Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Alexandria University, Egypt.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Go AS, et al. , Heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 2014. 129(3): p. e28–e292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendelsohn ME and Karas RH, The protective effects of estrogen on the cardiovascular system. N Engl J Med, 1999. 340(23): p. 1801–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Granger JP, et al. , Endothelin, the kidney, and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep, 2006. 8(4): p. 298–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davenport AP, et al. , Endothelin. Pharmacol Rev, 2016. 68(2): p. 357–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levin ER, Endothelins. N Engl J Med, 1995. 333(6): p. 356–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall JE, et al. , Hypertension: physiology and pathophysiology. Compr Physiol, 2012. 2(4): p. 2393–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elijovich F, et al. , Salt Sensitivity of Blood Pressure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Hypertension, 2016. 68(3): p. e7–e46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pollock DM and Pollock JS, Evidence for endothelin involvement in the response to high salt. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 2001. 281(1): p. F144–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Speed JS, et al. , High salt diet increases the pressor response to stress in female, but not male ETB-receptor-deficient rats. Physiol Rep, 2015. 3(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber MA, et al. , A selective endothelin-receptor antagonist to reduce blood pressure in patients with treatment-resistant hypertension: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet, 2009. 374(9699): p. 1423–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gohar EY, et al. , Role of the endothelin system in sexual dimorphism in cardiovascular and renal diseases. Life Sci, 2016. 159: p. 20–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohan DE, et al. , Clinical trials with endothelin receptor antagonists: what went wrong and where can we improve? Life Sci, 2012. 91(13–14): p. 528–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulman IH, et al. , Surgical menopause increases salt sensitivity of blood pressure. Hypertension, 2006. 47(6): p. 1168–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wassertheil-Smoller S, et al. , Hypertension and its treatment in postmenopausal women: baseline data from the Women’s Health Initiative. Hypertension, 2000. 36(5): p. 780–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burt VL, et al. , Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population. Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1991. Hypertension, 1995. 25(3): p. 305–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khalil RA, Sex hormones as potential modulators of vascular function in hypertension. Hypertension, 2005. 46(2): p. 249–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reckelhoff JF, Sex steroids, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension: unanswered questions and some speculations. Hypertension, 2005. 45(2): p. 170–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tremollieres FA, et al. , Coronary heart disease risk factors and menopause: a study in 1684 French women. Atherosclerosis, 1999. 142(2): p. 415–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hajjar I and Kotchen TA, Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. JAMA, 2003. 290(2): p. 199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JK, et al. , Recent changes in cardiovascular risk factors among women and men. J Womens Health (Larchmt), 2006. 15(6): p. 734–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilcox JG, et al. , Endothelin levels decrease after oral and nonoral estrogen in postmenopausal women with increased cardiovascular risk factors. Fertil Steril, 1997. 67(2): p. 273–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komatsumoto S and Nara M, [Changes in the level of endothelin-1 with aging]. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi, 1995. 32(10): p. 664–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saltevo J, Puolakka J, and Ylikorkala O, Plasma endothelin in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome: a comparison of oral combined and transdermal oestrogen-only replacement therapy. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2000. 2(5): p. 293–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Son WM, et al. , Combined exercise reduces arterial stiffness, blood pressure, and blood markers for cardiovascular risk in postmenopausal women with hypertension. Menopause, 2017. 24(3): p. 262–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Webb CM, et al. , 17beta-estradiol decreases endothelin-1 levels in the coronary circulation of postmenopausal women with coronary artery disease. Circulation, 2000. 102(14): p. 1617–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wenner MM, et al. , ETB receptor contribution to vascular dysfunction in postmenopausal women. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol, 2017. 313(1): p. R51–R57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gohar EY, Yusuf C, and Pollock DM, Ovarian hormones modulate endothelin A and B receptor expression. Life Sci, 2016. 159: p. 148–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitamura K, et al. , Regional distribution of immunoreactive endothelin in porcine tissue: abundance in inner medulla of kidney. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1989. 161(1): p. 348–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gohar EY, et al. , Ovariectomy uncovers purinergic receptor activation of endothelin-dependent natriuresis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 2017. 313(2): p. F361–F369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li P, et al. , Chronic vagus nerve stimulation attenuates vascular endothelial impairments and reduces the inflammatory profile via inhibition of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway in ovariectomized rats. Exp Gerontol, 2016. 74: p. 43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lima R, et al. , Roles played by 20-HETE, angiotensin II and endothelin in mediating the hypertension in aging female spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol, 2013. 304(3): p. R248–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sava RI, March KL, and Pepine CJ, Hypertension in pregnancy: Taking cues from pathophysiology for clinical practice. Clin Cardiol, 2018. 41(2): p. 220–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palei AC, et al. , Pathophysiology of hypertension in pre-eclampsia: a lesson in integrative physiology. Acta Physiol (Oxf), 2013. 208(3): p. 224–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu YP, et al. , Plasma ET-1 Concentrations Are Elevated in Pregnant Women with Hypertension -Meta-Analysis of Clinical Studies. Kidney Blood Press Res, 2017. 42(4): p. 654–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mastrogiannis DS, et al. , Potential role of endothelin-1 in normal and hypertensive pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1991. 165(6 Pt 1): p. 1711–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LaMarca B, et al. , Hypertension in response to autoantibodies to the angiotensin II type I receptor (AT1-AA) in pregnant rats: role of endothelin-1. Hypertension, 2009. 54(4): p. 905–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.LaMarca B, et al. , Placental Ischemia and Resultant Phenotype in Animal Models of Preeclampsia. Curr Hypertens Rep, 2016. 18(5): p. 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bakrania BA, et al. , Heme oxygenase-1 is a potent inhibitor of placental ischemia-mediated endothelin-1 production in cultured human glomerular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol, 2018. 314(3): p. R427–R432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saleh L, et al. , The emerging role of endothelin-1 in the pathogenesis of pre-eclampsia. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis, 2016. 10(5): p. 282–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jain A, Endothelin-1: a key pathological factor in pre-eclampsia? Reprod Biomed Online, 2012. 25(5): p. 443–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murphy SR, et al. , Role of endothelin in mediating soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1-induced hypertension in pregnant rats. Hypertension, 2010. 55(2): p. 394–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.George EM and Granger JP, Endothelin: key mediator of hypertension in preeclampsia. Am J Hypertens, 2011. 24(9): p. 964–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saleh L, Danser JA, and van den Meiracker AH, Role of endothelin in preeclampsia and hypertension following antiangiogenesis treatment. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens, 2016. 25(2): p. 94–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bakrania B, et al. , The Endothelin Type A Receptor as a Potential Therapeutic Target in Preeclampsia. Int J Mol Sci, 2017. 18(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thaete LG, et al. , Endothelin receptor antagonist has limited access to the fetal compartment during chronic maternal administration late in pregnancy. Life Sci, 2012. 91(13–14): p. 583–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maynard SE, et al. , Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest, 2003. 111(5): p. 649–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kendall RL, Wang G, and Thomas KA, Identification of a natural soluble form of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, FLT-1, and its heterodimerization with KDR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1996. 226(2): p. 324–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shibuya M, Structure and function of VEGF/VEGF-receptor system involved in angiogenesis. Cell Struct Funct, 2001. 26(1): p. 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karumanchi SA, Angiogenic factors in preeclampsia: implications for clinical practice. BJOG, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karumanchi SA, Angiogenic Factors in Preeclampsia: From Diagnosis to Therapy. Hypertension, 2016. 67(6): p. 1072–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Verdonk K, et al. , Association studies suggest a key role for endothelin-1 in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia and the accompanying renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system suppression. Hypertension, 2015. 65(6): p. 1316–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aggarwal PK, et al. , The relationship between circulating endothelin-1, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 and soluble endoglin in preeclampsia. J Hum Hypertens, 2012. 26(4): p. 236–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stanhewicz AE, et al. , Alterations in endothelin type B receptor contribute to microvascular dysfunction in women who have had preeclampsia. Clin Sci (Lond), 2017. 131(23): p. 2777–2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Majali-Martinez A, et al. , Endothelin-1 down-regulates matrix metalloproteinase 14 and 15 expression in human first trimester trophoblasts via endothelin receptor type B. Hum Reprod, 2017. 32(1): p. 46–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taichman DB and Mandel J, Epidemiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Clin Chest Med, 2007. 28(1): p. 1–22, vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Safdar Z, Pulmonary hypertension: a woman’s disease. Tex Heart Inst J, 2013. 40(3): p. 302–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rubin LJ, et al. , Bosentan therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med, 2002. 346(12): p. 896–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kozu K, et al. , Sex differences in hemodynamic responses and long-term survival to optimal medical therapy in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Heart Vessels, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gabler NB, et al. , Race and sex differences in response to endothelin receptor antagonists for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest, 2012. 141(1): p. 20–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marra AM, et al. , Gender-related differences in pulmonary arterial hypertension targeted drugs administration. Pharmacol Res, 2016. 114: p. 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mathai SC, et al. , Sex differences in response to tadalafil in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest, 2015. 147(1): p. 188–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]