Keywords: cytokines, distal stump, gene ontology, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway, peripheral nerve injury, protein microarray, protein-protein interaction network, Wallerian degeneration

Abstract

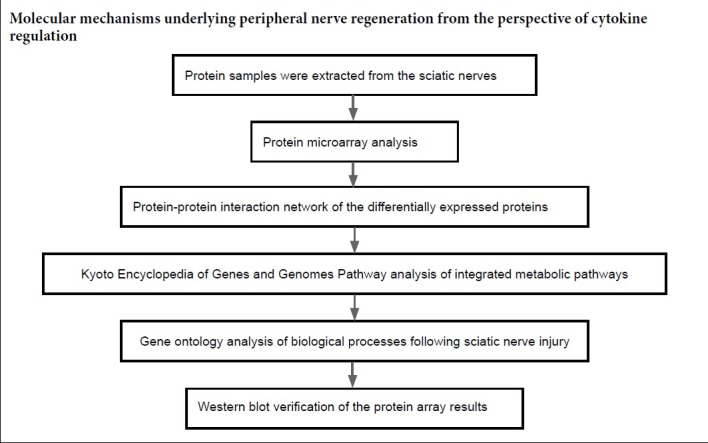

A large number of chemokines, cytokines, other trophic factors and the extracellular matrix molecules form a favorable microenvironment for peripheral nerve regeneration. This microenvironment is one of the major factors for regenerative success. Therefore, it is important to investigate the key molecules and regulators affecting nerve regeneration after peripheral nerve injury. However, the identities of specific cytokines at various time points after sciatic nerve injury have not been determined. The study was performed by transecting the sciatic nerve to establish a model of peripheral nerve injury and to analyze, by protein microarray, the expression of different cytokines in the distal nerve after injury. Results showed a large number of cytokines were up-regulated at different time points post injury and several cytokines, e.g., ciliary neurotrophic factor, were downregulated. The construction of a protein-protein interaction network was used to screen how the proteins interacted with differentially expressed cytokines. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway and Gene ontology analyses indicated that the differentially expressed cytokines were significantly associated with chemokine signaling pathways, Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription, phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B, and notch signaling pathway. The cytokines involved in inflammation, immune response and cell chemotaxis were up-regulated initially and the cytokines involved in neuronal apoptotic processes, cell-cell adhesion, and cell proliferation were up-regulated at 28 days after injury. Western blot analysis showed that the expression and changes of hepatocyte growth factor, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor and ciliary neurotrophic factor were consistent with the results of protein microarray analysis. The results provide a comprehensive understanding of changes in cytokine expression and changes in these cytokines and classical signaling pathways and biological functions during Wallerian degeneration, as well as a basis for potential treatments of peripheral nerve injury. The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Chinese PLA General Hospital, China (approval number: 2016-x9-07) in September 2016.

Chinese Library Classification No. R447; R363; R741

Introduction

Although the peripheral nerve has remarkable regenerative abilities after injury, it is difficult to recover completely from long-term nerve defects following peripheral nerve injury (PNI) (Raimondo et al., 2011). After PNI, Wallerian degeneration, a complicated process involving distal axonal degeneration and myelin breakdown, takes place immediately (Geuna et al., 2009). Subsequently, multiple macrophages and monocytes migrate to remove the axon and myelin debris. Schwann cells proliferate to form bands of Büngner as a bridge to the defective peripheral nerve system. They secrete a large number of chemokines, cytokines and other trophic factors and extracellular matrix molecules, which form a favorable microenvironment for peripheral nerve regeneration (Frostick et al., 1998; Chen et al., 2007). This microenvironment is one of the major factors of regenerative success (Webber and Zochodne, 2010). Therefore, it is important to investigate the key molecules and regulators affecting nerve regeneration after PNI.

In early studies, microarrays were widely used to characterize differentially expressed genes in the distal nerve stump following PNI (Pan et al., 2017). Temporal expression patterns of upregulated and downregulated genes during Wallerian degen-eration were validated (Yu et al., 2016; Yi et al., 2017). RNA-sequencing was also performed to evaluate comprehensive transcriptomic expression and identify numerous differentially expressed microRNAs at different time points during peripheral nerve regeneration (Yi et al., 2015). These studies have helped elucidate global gene expression changes involved in peripheral nerve repair. However, in many cases during peripheral nerve regeneration, multiple cellular events occur after a gene is translated into a protein. Several studies have suggested that some proteins have significant effects on many biological processes during peripheral nerve repair and Wallerian degeneration, including immune responses, macrophage recruitment and Schwann cell reprogramming (van der Laan et al., 1996; da Costa et al., 1997; Siebert et al., 2000; Takahashi et al., 2007; Clements et al., 2017). Nevertheless, the integrated relationships between proteins involved in PNI and recovery are not yet clear.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the dynamic differential expression of 67 cytokines using a protein micro-array to achieve greater insight into the relative pathways or networks during Wallerian degeneration of injured sciatic nerve. We used bioinformatic analyses (protein-protein interaction (PPI) network, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes Pathway (KEGG) pathway and gene ontology (GO) analysis).

Materials and Methods

Animals

In this study, eighty male Sprague-Dawley rats (specific pathogen free level) weighing 200–250 g, aged 7–8 weeks, were obtained from the Experimental Animal Research Center at the Chinese PLA General Hospital, China. The rats were housed in a temperature-controlled environment and fed water and food ad libitum. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Chinese PLA General Hospital, China approved the experimental procedures (approval No. 2016-x9-07) in September 2016.

Rats were randomly divided into five groups: control and 4 periods post injury. Briefly, rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (30 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The sciatic nerve was exposed via incision on the lateral aspect of the right hind limb and was excised through the middle site of the exposed sciatic nerve (Yu et al., 2012). At 1, 7, 14, and 28 days after nerve transection, the rats were sacrificed by decapitation. The distal nerve stumps were removed and stored at −80°C until further use. As a control, rats in the 0 day group underwent sham surgery of the right sciatic nerves.

Protein microarray analysis

Protein samples were extracted from the distal nerve stumps of sciatic nerves of the rats and lysed in radioimmuno-precipitation assay buffer lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Pulilai, Beijing, China). Subsequently, protein concentrations were determined using the Pierce Bicinchoninic acid assay Kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA).

Microarray analysis was performed using the Rat Cytokine Array 67 (RayBiotech, Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China), as described previously (Luck et al., 2017). Briefly, the microarray was incubated with 100 μL sample diluent at room temperature for 30 minutes to block the slides. After removing the diluent, the array was completely covered with 100 μL of the protein sample (2 mg/mL) and incubated at 4°C overnight. Biotinylated antibody cocktail (80 μL) was added to each well at room temperature for 2 hours. Cy3 equivalent dye-conjugated streptavidin (80 μL) was added to each well, and the wells were covered with aluminum foil and placed in a dark room to avoid light exposure at room temperature for 1 hour. The signals were visualized using the LuxScan 10K scanner (CapitaBio, Beijing, China) at 532 nm wavelength.

Bioinformatic analysis

The expression levels of proteins at 1, 7, 14, and 28 days after sciatic nerve transection were compared with those in the control group. Proteins with an expression fold change > 2 or < −2 and adjusted P-value < 0.05 were considered significantly differentially expressed. The differentially expressed proteins, Venn diagram and Principal Component analysis were performed by R packages (http://www.R-project.org) named gplots, VennDiagram and scatterplot3d, respectively. The GeneMANIA database (http://genemania.org) is a gene and protein analysis tool designed to predict PPIs. The various proteins were mapped using GeneMANIA to evaluate the interactive relationships among them. The PPI networks were then constructed using Cytoscape software (http://www.cytoscape.org).

Proteins selected from the PPI networks were systematically analyzed using the Database for Annotation, Visu-alization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID; http://www.david.niaid.nih.gov) program to identify significantly enriched KEGG pathways and GO categories (Dennis et al., 2003). The KEGG pathways and GO categories were performed by R packages named ggplot2.

Western blot analysis

Sciatic nerves were rinsed in cold PBS and lysed on ice in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing a pro-tease inhibitor cocktail (Pulilai), and the resulting tissue lysates were mixed with sample buffer and boiled at 95°C for 5 minutes. Equal amounts of protein from each sample were subjected to 10–15% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Pulilai). The membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk at 4°C for 1 hour and incubated with rabbit anti-hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) antibody (1:1000; ab83760, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), rabbit anti-glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) antibody (1:1000; ab18956, Abcam), rabbit anti-ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) antibody (1:1000; ab46172, Abcam) or rabbit anti-β-actin antibody (1:1000; Proteintech, Chicago, IL, USA) at 4°C overnight. These were followed by the appropriate secondary antibody, donkey-anti-rabbit-HRP (1:5000, Pulilai) at room temperature for 1 hour. The membranes were developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Thermo Fisher). Measurement of the protein band intensities was conducted using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Significant differences among data were determined by one-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and a P-value < 0.05 was designated as indicating statistical significance.

Results

Differentially expressed proteins in the distal nerve stump following sciatic nerve transection

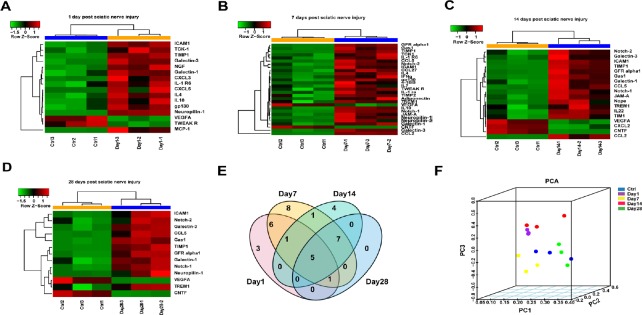

To gain a better understanding of the microenvironment of the distal nerve stump, we examined the expression patterns of 67 proteins in injured sciatic nerves at different time points using the Rat Cytokine Array 67 (Table 1). Proteins with a fold change in expression > 2 or < −2 and an adjusted P < 0.05 were defined as differentially expressed. A full list of the differentially expressed proteins at each time point evaluated is displayed in a heatmap (Figure 1A–D). Compared with the control group (0 day after PNI), the expression of nearly 20% of the total proteins increased at 1 day after PNI, including some chemokines and interleukins (ILs). The number of upregulated proteins increased to 33% of the total proteins at 7 days after PNI. In addition to chemokines and ILs, Notch 1/2 and Neuropilin 1/2, which are related to some classical pathways, increased in expression starting at 7 days after PNI. At 14 days after PNI, no ILs, except for IL-22, showed any remarkable expression changes. At 28 days after PNI, the number of upregulated proteins had decreased slightly. From day 1 to day 28 after PNI, only a few proteins, including CNTF, were downregulated. The numbers of overlapping differentially expressed proteins at 1, 7, 14, 28 days post injury are displayed in a Venn diagram (Figure 1E). Principal component analysis based on the expression values of the 67 proteins demonstrated five completely independent clusters: control and the other time points after injury (Figure 1F).

Table 1.

The 67 cytokine proteins included on the RayBiotech Rat Cytokine Array 67

| Proteins | Genes | Proteins | Genes | Proteins | Genes | Proteins | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD48 | Cd48 | IL-10 | Il10 | CNTF | Cntf | Adiponectin | Adipoq |

| B7-1 | Cd80 | IL-13 | Il13 | FGF-BP | Fgfbp1 | RAGE | Ager |

| B7-2 | Cd86 | IL-17F | Il17f | GFR alpha-1 | Gfra1 | GM-CSF | Csf2 |

| P-Cadherin | Cdh3 | IL-1a | Il1a | HGF | Hgf | Decorin | Dcn |

| Eotaxin | Ccl11 | IL-1b | Il1b | IFNg | Ifng | EphA5 | Epha5 |

| MCP-1 | Ccl2 | IL-1 R6 | Il1rl2 | b-NGF | Ngf | Erythropoietin | Epo |

| CTACK | Ccl27 | IL-1 ra | Il1rn | PDGF-AA | Pdgfa | JAM-A | F11r |

| MIP-1a | Ccl3 | IL-2 | Il2 | TNFa | Tnf | Gas 1 | Gas1 |

| RANTES | Ccl5 | IL-22 | Il22 | VEGFA | Vegfa | TIM-1 | Havcr1 |

| Fractalkine | Cx3cl1 | IL-2 Ra | Il2ra | 4-1BB | Tnfrsf9 | ICAM-1 | Icam1 |

| CINC-1 | Cxcl1 | IL-3 | Il3 | Flt-3L | Flt3lg | Nope | Igdcc4 |

| CINC-3 | Cxcl2 | IL-4 | Il4 | Galectin-1 | Lgals1 | Activin A | Inhba |

| CINC-2 | Cxcl3 | IL-6 | Il6 | Galectin-3 | Lgals3 | SCF | Kitlg |

| LIX | Cxcl5 | gp130 | Il6st | Notch-1 | Notch1 | TCK-1 | Ppbp |

| TIMP-1 | Timp1 | IL-7 | Il7 | Notch-2 | Notch2 | Prolactin | Prl |

| TIMP-2 | Timp2 | TWEAK R | Tnfrsf12a | Neuropilin-1 | Nrp1 | Prolactin R | Prlr |

| TREM-1 | Trem1 | Neuropilin-2 | Nrp2 | L-Selectin | Sell |

Figure 1.

Overview of differentially expressed cytokines at the distal stump following sciatic nerve transection.

(A–D) Heatmap and hierarchical clustering at 1 (A), 7 (B), 14 (C), 28 (D) days. Protein expression was increased (red) and decreased (green) compared with the control (0 day after sciatic nerve transection). (E) Venn diagram displaying the number of different proteins among the four groups of sciatic nerves at each time point after sciatic nerve transection. (F) Principal component analysis of the differentially expressed cytokines at different time points following sciatic nerve transection. PC: Principal component; PCA: principal component analysis.

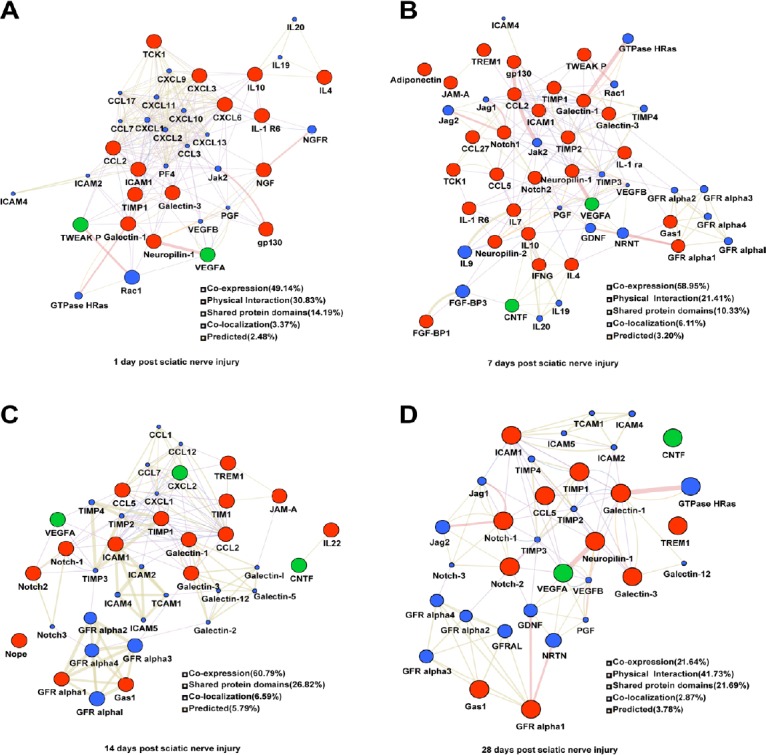

Protein-protein interaction network of the differentially expressed proteins

Many proteins were temporally differentially expressed in the injured sciatic nerve, suggesting that those cytokines have a dramatic effect on the nerve microenvironment after PNI. To explore this further, PPI networks were constructed by uploading the up- and downregulated proteins into GeneMANIA. In addition to the differentially expressed proteins, other chemotactic and inflammatory factors were selected within these networks, such as CC chemokine ligand (CCL17), chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL13), the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 (TIMP3) and others. At 1 day after PNI, the differentially expressed proteins were mainly related to chemotactic family proteins (CCL2, CCL3, CCL7, CCL17, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL6, CXCL9, CXCL11 and CXCL13) (Figure 2A). At 7 days after PNI, the proteins in the PPI included GFR alpha2, GFR alpha3, GFR alpha4, IL9, IL19, IL20, tyrosine-protein kinase 2 (JAK 2), Jag1, Jag2, TIMP3, TIMP4, VEGFB, GDNF, Neurturin (NRTN) (Figure 2B). At 14 days after PNI, CCL1, CCL2, CCL5, CCL7, CCL15, CXCL1, CXCL2, intercellular adhesion molecule 2 (ICAM2), ICAM4, ICAM5, GFR alpha1, GDNF family receptor (GFR) alpha2, GFR alpha4, Notch-3, Galectin-1, Galectin-2, Galectin-5, Galectin-12 were selected in the PPI network (Figure 2C). At 28 days after PNI, GFR alpha2, GFR alpha3, GFR alpha4, Notch-3, VEGFB, GDNF, NRTN, placenta growth factor, TIMP2, TIMP3, TIMP4, ICAM1, ICAM2, ICAM4, ICAM5, Galectin-12, GTPase Hras, Jag2 interacted with the differentially expressed proteins (Figure 2D). In addition, there were several connections between the differentially expressed proteins and the selected proteins. Co-expression characteristics and described physical interactions accounted for most of the aforementioned targets and their interacting proteins. Other results, including shared protein domains, co-localization and predictions are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Networks of protein-protein interactions of the differentially expressed proteins in the distal nerve stump following sciatic nerve transection.

(A–D) Differentially expressed proteins at 1 (A), 7 (B), 14 (C), 28 (D) days. The sizes of the spots in the network represent the weights of the interaction involving the protein. The red spots represent the upregulated proteins and green spots the downregulated proteins at each time point after sciatic nerve transection. The blue spots represent the selected proteins interact with the differentially expressed proteins. The colors of the the connecting lines represent the different interactions between protein and protein. The thickness of the connecting lines represents the score of each connection.

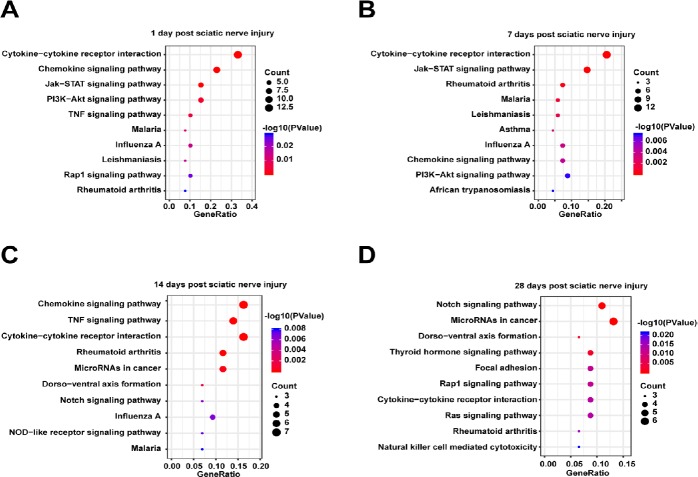

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes enriched analysis of integrated metabolic pathways following sciatic nerve injury

The proteins from the PPI networks were correlated with integrated metabolic pathways using KEGG analysis in DAVID. The top 10 canonical pathways associated with differentially expressed cytokines at each time point were displayed and analyzed using a P-value threshold of 0.05 (Figure 3). Cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions and rheumatiod arthritis were activated throughout the entire post-injury period. Notably, the chemokine signaling pathways, Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK/STAT) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt), and leishmainasis were drastically stimulated at 1–7 days after PNI, while the notch signaling pathway and dorso-ventral axis formation were enriched at 14–28 days after PNI. Besides, malaria and influenze A were activited at 1–14 days after PNI. A full list of the canonical pathways and their involved molecules identified at 1, 7, 14, and 28 days after PNI is provided in Additional Table 1.

Figure 3.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways enriched among the proteins in the protein-protein interaction network in the distal nerve stump following sciatic nerve transection.

(A–D) Differentially expressed proteins at 1 (A), 7 (B), 14 (C) and 28 (D) days. The top 10 KEGG pathways with P < 0.05 are listed. The x-axis represents the gene ratio, defined as the ratio of the numbers of differentially expressed proteins to all proteins annotated in the KEGG pathway using Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID; http://www.david.niaid.nih.gov).

Additional Table 1

| Category | Term | Count | % | P-value | Molecules | List total | Pop hits | Pop total | Fold enrichmen | Bonferroni | Benjamini | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | ||||||||||||

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc04060:Cytokine- cytokine receptor interaction | 13 | 0.33121019 | 3.40E-13 | VEGFB, IL4, CCL2, PPBP, IL6ST, TNFRSF12A, CXCL13, VEGFA, CXCL9, NGFR, CXCL11, IL10, | 23 | 221 | 7030 | 17.97953964 | 2.04E-11 | 2.04E-11 | 3.40E-10 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc04062:Chemokine signaling pathway | 9 | 0.22929936 | 2.73E-08 | CCL2,PPBP, CXCL13, CXCL2, CXCL9, JAK2, CXCL11, CCL17, CXCL10 | 23 | 173 | 7030 | 15.90098015 | 1.64E-06 | 8.18E-07 | 2.73E-05 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc04630:Jak-STAT signaling pathway | 6 | 0.15286624 | 5.85E-05 | IL4, IL6ST, IL19, JAK2, IL10, IL20 | 23 | 140 | 7030 | 13.09937888 | 0.003500988 | 0.00116836 | 0.05856165 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc04151:PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | 6 | 0.15286624 | 0.00285045 | IL4, VEGFB, PGF, VEGFA, JAK2, NGFR | 23 | 326 | 7030 | 5.625500133 | 0.157406886 | 0.04191404 | 2.820171 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc04668:TNF signaling pathway | 4 | 0.10191083 | 0.00439045 | ICAM1, CCL2, CXCL2, CXCL10 | 23 | 108 | 7030 | 11.32045089 | 0.232031866 | 0.05143163 | 4.31383707 |

| KEGG_PATHWA | ssc05144:Malaria | 3 | 0.07643312 | 0.01127811 | ICAM1, CCL2, IL10 | 23 | 52 | 7030 | 17.63377926 | 0.493652212 | 0.1072261 | 10.7445415 |

| KEGG_PATHWA | ssc05164:Influenza A | 4 | 0.10191083 | 0.0145511 | ICAM1, CCL2, JAK2, CXCL10 | 23 | 167 | 7030 | 7.321010154 | 0.585001467 | 0.11806775 | 13.6617584 |

| KEGG_PATHWA | ssc05140:Leishmanias | 3 | 0.07643312 | 0.01578332 | IL4, JAK2, IL10 | 23 | 62 | 7030 | 14.78962132 | 0.615015566 | 0.11247541 | 14.7376045 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc04015:Rap1 signaling pathway | 4 | 0.10191083 | 0.02533146 | VEGFB, PGF, VEGFA, NGFR | 23 | 206 | 7030 | 5.934993668 | 0.785505085 | 0.15722237 | 22.6735405 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc05323:Rheumatoid arthritis | 3 | 0.07643312 | 0.02916058 | ICAM1, CCL2, VEGFA | 23 | 86 | 7030 | 10.66228514 | 0.830627048 | 0.16269361 | 25.6646135 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc04014:Ras signaling pathway | 4 | 0.10191083 | 0.03002464 | VEGFB, PGF, VEGFA, NGFR | 23 | 220 | 7030 | 5.557312253 | 0.8394382 | 0.15319063 | 26.3249811 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc04620:Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | 3 | 0.07643312 | 0.03917298 | CXCL9, CXCL11, CXCL10 | 23 | 101 | 7030 | 9.078777443 | 0.909068921 | 0.18110913 | 32.9997956 |

| KEGG_PATHWA | ssc05310:Asthma | 2 | 0.05095541 | 0.06965828 | IL4, IL10 | 23 | 23 | 7030 | 26.57844991 | 0.986861379 | 0.28340618 | 51.4995559 |

| Day 7 | ||||||||||||

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc04060:Cytokine- cytokine receptor interaction | 14 | 0.20548951 | 2.8045E-13 | IL4, CCL2, IL7, TNFRSF12A, IL6ST, IL9, CCL5, CCL27, IL10, VEGFB, CNTF, PPBP, VEGFA, IFNG | 28 | 221 | 7030 | 15.90497738 | 2.04723E-11 | 2.0472E-11 | 2.9272E-10 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc04630:Jak-STAT signaling pathway | 10 | 0.14677822 | 1.3162E-09 | IL4, CNTF, IL6ST, IL7, IFNG, IL19, IL9, JAK2, IL10, IL20 | 28 | 140 | 7030 | 17.93367347 | 9.60815E-08 | 4.8041E-08 | 1.3738E-06 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc05323:Rheumatoid arthritis | 5 | 0.07338911 | 0.00029559 | ICAM1, CCL2, IFNG, VEGFA, CCL5 | 28 | 86 | 7030 | 14.59717608 | 0.021350158 | 0.00716798 | 0.30810644 |

| KEGG_PATHWA | ssc05144:Malaria | 4 | 0.05871129 | 0.00098511 | ICAM1, CCL2, IFNG, IL10 | 28 | 52 | 7030 | 19.31318681 | 0.06942148 | 0.0178264 | 1.02348937 |

| KEGG_PATHWA | ssc05140:Leishmanias | 4 | 0.05871129 | 0.00164329 | IL4, IFNG, JAK2, IL10 | 28 | 62 | 7030 | 16.19815668 | 0.113131722 | 0.02372577 | 1.70201483 |

| KEGG_PATHWA | ssc05310:Asthma | 3 | 0.04403347 | 0.00341977 | IL4, IL9, IL10 | 28 | 23 | 7030 | 32.7484472 | 0.221254387 | 0.04082187 | 3.51247659 |

| KEGG_PATHWA | ssc05164:Influenza A | 5 | 0.07338911 | 0.00351799 | ICAM1, CCL2, IFNG, JAK2, CCL5 | 28 | 167 | 7030 | 7.51710864 | 0.226837364 | 0.0360851 | 3.61169015 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc04062:Chemokine signaling pathway | 5 | 0.07338911 | 0.00399326 | CCL2, PPBP, JAK2, CCL5, CCL27 | 28 | 173 | 7030 | 7.25639967 | 0.253300018 | 0.03585297 | 4.0904725 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc04151:PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | 6 | 0.08806693 | 0.00722646 | IL4, VEGFB, PGF, IL7, VEGFA, JAK2 | 28 | 326 | 7030 | 4.620946538 | 0.411069421 | 0.05713054 | 7.29086559 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc05143:African trypanosomiasis | 3 | 0.04403347 | 0.00738845 | ICAM1, IFNG, IL10 | 28 | 34 | 7030 | 22.15336134 | 0.418043509 | 0.0526967 | 7.44864556 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc05142:Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis) | 4 | 0.05871129 | 0.00768878 | CCL2, IFNG, CCL5, ILIO | 28 | 107 | 7030 | 9.385847797 | 0.430758015 | 0.04993293 | 7.74051304 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | sscO5330:Allograft rejection | 3 | 0.04403347 | 0.00870947 | IL4, IFNG, IL10 | 28 | 37 | 7030 | 20.35714286 | 0.471956101 | 0.05182354 | 8.72625592 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | SSC04330:Notch signaling pathway | 3 | 0.04403347 | 0.0121687 | NOTCH2, JAG2, JAG1 | 28 | 44 | 7030 | 17.11850649 | 0.590887078 | 0.06644097 | 11.9966412 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc05321:Inflammator y bowel disease (IBD) | 3 | 0.04403347 | 0.02261767 | IL4, IFNG, IL10 | 28 | 61 | 7030 | 12.34777518 | 0.811761955 | 0.11244886 | 21.2421676 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc05168:Herpes simplex infection | 4 | 0.05871129 | 0.03164347 | CCL2, IFNG, JAK2, CCL5 | 28 | 182 | 7030 | 5.518053375 | 0.904374051 | 0.14485771 | 28.5113284 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc04066:HIF-1 signaling pathway | 3 | 0.04403347 | 0.05684533 | IFNG, VEGFA, TIMP1 | 28 | 101 | 7030 | 7.457567185 | 0.986050678 | 0.23434245 | 45.7127052 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc04660:T cell receptor signaling pathway | 3 | 0.04403347 | 0.06191833 | IL4, IFNG, IL10 | 28 | 106 | 7030 | 7.105795148 | 0.990590483 | 0.24002715 | 48.684362 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | ssc04668:TNF signaling pathway | 3 | 0.04403347 | 0.0639902 | ICAM1, CCL2, CCL5 | 28 | 108 | 7030 | 6.974206349 | 0.991993018 | 0.23523844 | 49.8551108 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | ssc05145:Toxoplasmo sis | 3 | 0.04403347 | 0.07034613 | IFNG, JAK2, IL10 | 28 | 114 | 7030 | 6.607142857 | 0.995130845 | 0.24440856 | 53.2975516 |

| KEGG_PATHWA | ssc05162:Measles | 3 | 0.04403347 | 0.09057419 | IL4, IFNG, JAK2 | 28 | 132 | 7030 | 5.706168831 | 0.999022737 | 0.29286788 | 62.8793488 |

| Day 14 | ||||||||||||

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | rno04062:Chemokine signaling pathway | 7 | 0.16252612 | 1.88E-06 | CXCL1, CCL1, CCL12, CCL2, CXCL2, CCL5, CCL7 | 19 | 177 | 7780 | 16.19387452 | 7.92E-05 | 7.92E-05 | 1.74E-03 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | rno04668:TNF signaling pathway | 6 | 0.1393081 | 3.65E-06 | CXCL1, ICAM1, CCL12, CCL2, CXCL2, CCL5 | 19 | 109 | 7780 | 22.53983583 | 1.53E-04 | 7.66E-05 | 3.38E-03 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | rno04060: Cytokine- cytokine receptor interaction | 7 | 0.16252612 | 6.00E-06 | CCL12, CCL2, CNTF, VEGFA, CCL5, IL22, CCL7 | 19 | 216 | 7780 | 13.26998051 | 2.52E-04 | 8.40E-05 | 5.55E-03 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | rno05323:Rheumatoid arthritis | 5 | 0.11609009 | 4.53E-05 | ICAM1, CCL12, CCL2, VEGFA, CCL5 | 19 | 90 | 7780 | 22.74853801 | 1.90E-03 | 4.75E-04 | 4.19E-02 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | rno05206:MicroRNAs | 5 | 0.11609009 | 2.74E-04 | NOTCH3, NOTCH2, NOTCH1, VEGFA, | 19 | 143 | 7780 | 14.31726169 | 1.14E-02 | 2.30E-03 | 2.53E-01 |

| in cancer | TIMP3 | |||||||||||

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | rno04320:Dorso- ventral axis formation | 3 | 0.06965405 | 1.47E-03 | NOTCH3, NOTCH2, NOTCH1 | 19 | 25 | 7780 | 49.13684211 | 5.99E-02 | 1.02E-02 | 1.35E+00 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | rno04330:Notch | 3 | 0.06965405 | 6.26E-03 | NOTCH3, NOTCH2, NOTCH1 | 19 | 52 | 7780 | 23.62348178 | 2.32E-01 | 3.70E-02 | 5.65E+00 |

| signaling pathway | ||||||||||||

| KEGG_PATHWA | rno05164:Influenza A | 4 | 0.09287207 | 6.68E-03 | ICAM1, CCL12, CCL2, CCL5 | 19 | 171 | 7780 | 9.578331794 | 2.45E-01 | 3.46E-02 | 6.01E+00 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | rno04621:NOD-like receptor signaling pathway | 3 | 0.06965405 | 7.23E-03 | CCL12, CCL2, CCL5 | 19 | 56 | 7780 | 21.93609023 | 2.63E-01 | 3.33E-02 | 6.50E+00 |

| KEGG_PATHWA | rno05144:Malaria | 3 | 0.06965405 | 8.00E-03 | ICAM1, CCL12, CCL2 | 19 | 59 | 7780 | 20.82069581 | 2.86E-01 | 3.32E-02 | 7.17E+00 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | rno05142:Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis) | 3 | 0.06965405 | 2.48E-02 | CCL12, CCL2, CCL5 | 19 | 107 | 7780 | 11.48057059 | 6.52E-01 | 9.16E-02 | 2.08E+01 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | rno04919:Thyroid hormone signaling pathway | 3 | 0.06965405 | 2.84E-02 | NOTCH3, NOTCH2, NOTCH1 | 19 | 115 | 7780 | 10.6819222 | 7.02E-01 | 9.59E-02 | 2.34E+01 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | rno04514:Cell adhesion molecules | 3 | 0.06965405 | 5.90E-02 | ICAM1, F11R, ICAM2 | 19 | 172 | 7780 | 7.141982864 | 9.22E-01 | 1.78E-01 | 4.30E+01 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | rno05168:Herpes simplex infection | 3 | 0.06965405 | 8.78E-02 | CCL12, CCL2, CCL5 | 19 | 216 | 7780 | 5.687134503 | 9.79E-01 | 2.41E-01 | 5.73E+01 |

| Day 28 | ||||||||||||

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | cfa04330:Notch signaling pathway | 5 | 0.10957703 | 3.4697E-06 | NOTCH3, NOTCH2, NOTCH1, JAG2, | 17 | 47 | 6781 | 42.43429287 | 2.64E-04 | 0.00026366 | 3.65E-03 |

| JAG1 | ||||||||||||

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | cfa05206:MicroRNAs in cancer | 6 | 0.13149244 | 1.2266E-05 | NOTCH3, NOTCH2, NOTCH1, HRAS, | 17 | 139 | 6781 | 17.21794329 | 9.32E-04 | 0.000466 | 1.29E-02 |

| VEGFA, TIMP3 | ||||||||||||

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | cfa04320:Dorso- ventral axis formation | 3 | 0.06574622 | 0.0017703 | NOTCH3, NOTCH2, NOTCH1 | 17 | 27 | 6781 | 44.32026144 | 1.26E-01 | 0.04389487 | 1.85E+00 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | cfa04919:Thyroid hormone signaling pathway | 4 | 0.08766163 | 0.00215415 | NOTCH3, NOTCH2, NOTCH1, HRAS | 17 | 113 | 6781 | 14.11972931 | 1.51E-01 | 0.04014488 | 2.24E+00 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | cfa04510:Focal adhesion | 4 | 0.08766163 | 0.01170373 | VEGFB, HRAS, PGF, VEGFA | 17 | 207 | 6781 | 7.707871554 | 5.91E-01 | 0.16384884 | 1.17E+01 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | cfa04015:Rap1 signaling pathway | 4 | 0.08766163 | 0.01170373 | VEGFB, HRAS, PGF, VEGFA | 17 | 207 | 6781 | 7.707871554 | 5.91E-01 | 0.16384884 | 1.17E+01 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | cfa04060: Cytokine- cytokine receptor interaction | 4 | 0.08766163 | 0.01313391 | VEGFB, CNTF, VEGFA, CCL5 | 17 | 216 | 6781 | 7.38671024 | 6.34E-01 | 0.15419378 | 1.30E+01 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | cfa04014:Ras signaling pathway | 4 | 0.08766163 | 0.01346491 | VEGFB, HRAS, PGF, VEGFA | 17 | 218 | 6781 | 7.318942256 | 6.43E-01 | 0.13686453 | 1.33E+01 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | cfa05323:Rheumatoid arthritis | 3 | 0.06574622 | 0.01553142 | ICAM1, VEGFA, CCL5 | 17 | 82 | 6781 | 14.59325681 | 6.96E-01 | 0.13817783 | 1.52E+01 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | cfa04650:Natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity | 3 | 0.06574622 | 0.02174666 | ICAM1, HRAS, ICAM2 | 17 | 98 | 6781 | 12.21068427 | 8.12E-01 | 0.16944791 | 2.07E+01 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | cfa04151:PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | 4 | 0.08766163 | 0.0420905 | VEGFB, HRAS, PGF, VEGFA | 17 | 337 | 6781 | 4.73450864 | 9.62E-01 | 0.27878282 | 3.64E+01 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | cfa05200:Pathways in cancer | 4 | 0.08766163 | 0.06126129 | VEGFB, HRAS, PGF, VEGFA | 17 | 392 | 6781 | 4.070228091 | 9.92E-01 | 0.35388619 | 4.86E+01 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | cfa05205:Proteoglyca ns in cancer | 3 | 0.06574622 | 0.07581922 | HRAS, VEGFA, TIMP3 | 17 | 195 | 6781 | 6.136651584 | 9.98E-01 | 0.39308589 | 5.64E+01 |

| KEGG_PATHWA Y | cfa05219:Bladder cancer | 2 | 0.04383081 | 0.09257318 | HRAS, VEGFA | 17 | 41 | 6781 | 19.45767575 | 9.99E-01 | 0.4332909 | 6.40E+01 |

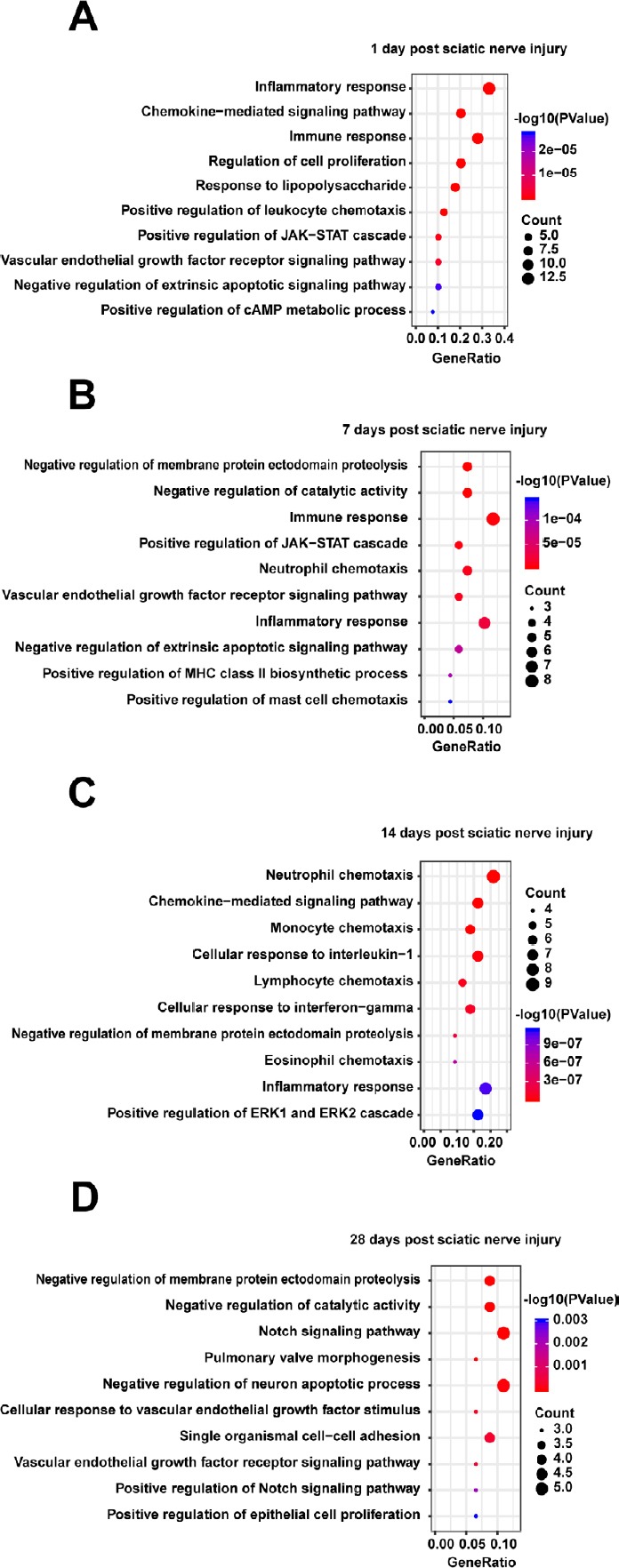

Gene ontology analysis of biological processes following sciatic nerve injury

To further explore the effects of cytokines following sciatic nerve injury, GO analysis was performed in DAVID to analyze biological processes. The top 10 biological processes (P < 0.05) associated with these proteins are displayed in Figure 4. At 1–7 days after PNI, biological processes related to inflammation, the immune response, and cell chemotaxis were activated. At 14 days after PNI, even more cell chemotaxis processes, as well as cell response to IL-1, interferon-gamma were activated, including neutrophil, monocyte, lymphocyte, and eosinophil chemotaxis. At 28 days after PNI, neuronal apoptotic processes, cell-cell adhesion, and cell proliferation were enriched. However, some biological processes were negatively regulated at different time after PNI. For example, the negative regulation of apoptosis first increased at 1–7 days after PNI, and then progressively declined at 14 days after PNI, before increasing again at 28 days after PNI. Membrane protein ectodomain proteolysis was inhibited from 7–28 days after PNI. Catalytic activity reduced at 7 and 28 days after PNI. A full list of the biological processes and involved molecules at 1, 7, 14, and 28 days after PNI is provided in Additional Table 2 (147KB, pdf) . More information on the highly enriched cellular components associated with PNI associated with the external side of the plasma membrane, extracellular matrix, immunological synapse, and receptor complex are shown in Additional Table 3.

Figure 4.

Gene ontology (GO) biological processes of those proteins enriched in the protein-protein interaction network in the distal nerve stump following sciatic nerve transection relative to all proteins.

(A–D) Differentially expressed proteins at 1 (A), 7 (B), 14 (C), 28 (D) days. The top 10 GO biological processes with P < 0.05 are listed. The x-axis represents the gene ratio, defined as the ratio of the numbers of differentially expressed proteins to all proteins annotated in the GO biological processes using Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID; http://www.david.niaid.nih.gov).

Additional Table 3

| Category | Term | Count | % | P-value | Molecules | List | total Pop hits | Pop total | Fold enrichmei | Bonferroni | Benjamini | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | ||||||||||||

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005615~extracellula r space | 20 | 0.50955414 | 5.00E-19 | IL4, ICAM1, NRP1, CCL2, LGALS3, PGF, LGALS1, CXCL2, IL19, CXCL9, CXCL11, IL10, IL20, CCL17, TIMP1, CXCL10, VEGFB, PPBP, CXCL13, VEGFA | 26 | 762 | 12833 | 12.95477488 | 1.85E-17 | 1.85E-17 | 4.49E-16 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0009897~external side of plasma membrane | 5 | 0.12738854 | 7.90E-05 | IL4, ICAM1, IL6ST, CXCL9, CXCL10 | 26 | 120 | 12833 | 20.56570513 | 0.00291951 | 0.00146082 | 0.07092918 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0001772~immunologi cal synapse | 2 | 0.05095541 | 0.04576193 | ICAM1, LGALS3 | 26 | 24 | 12833 | 41.13141026 | 0.82327447 | 0.43882313 | 34.3348902 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0016020~membrane | 5 | 0.12738854 | 0.04595763 | VEGFB, PGF, ICAM2, VEGFA, | 26 | 707 | 12833 | 3.49064302 | 0.8246105 | 0.35285604 | 34.4557081 |

| Day 7 | ||||||||||||

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005615~extracellula r space | 23 | 0.3375899 | 1.4551E-17 | IL4, ICAM1, CCL2, NRP1, LGALS3, PGF, IL7, LGALS1, IL9, IL1RN, IL19, TIMP4, TIMP2, CCL5, TIMP3, IL10, IL20, TIMP1, VEGFB, CNTF, PPBP, IFNG, VEGFA | 40 | 762 | 12833 | 9.683694226 | 6.1114E-16 | 6.1114E-16 | 1.3467E-14 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0009897~external side of plasma membrane | 5 | 0.07338911 | 0.00046445 | IL4, ICAM1, IL6ST, IFNG, GFRA3 | 40 | 120 | 12833 | 13.36770833 | 0.01932219 | 0.00970822 | 0.42902184 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005578~proteinaceo us extracellular matrix | 5 | 0.07338911 | 0.00087497 | LGALS1, TIMP4, TIMP2, TIMP3, TIMP1 | 40 | 142 | 12833 | 11.29665493 | 0.03609734 | 0.0121802 | 0.80686791 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005576~extracellula r region | 7 | 0.10274475 | 0.00131741 | NRTN, IL7, ADIPOQ, GDNF, FGFBP1, CCL27, TIMP1 | 40 | 407 | 12833 | 5.517874693 | 0.053863 | 0.01374662 | 1.21265635 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005622~intracellular | 6 | 0.08806693 | 0.03118422 | VEGFB, CCL2, GFRAL, LGALS1, IFNG, GFRA2 | 40 | 586 | 12833 | 3.284897611 | 0.73567964 | 0.23365183 | 25.4130934 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0001772~immunologi cal synapse | 2 | 0.02935564 | 0.07050482 | ICAM1, LGALS3 | 40 | 24 | 12833 | 26.73541667 | 0.95361474 | 0.40058169 | 49.1690919 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005604~basement membrane | 2 | 0.02935564 | 0.08457142 | TIMP3, TIMP1 | 40 | 29 | 12833 | 22.12586207 | 0.97555289 | 0.41149956 | 55.8597181 |

| Day 14 | ||||||||||||

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005615~extracellula r space | 21 | 0.48757836 | 2.2092E-15 | CXCL1, CCL1, ICAM1, HAVCR1, CCL2, ICAM4, LGALS3, LGALS1, CXCL2, TIMP4, CCL5, TIMP2, TIMP3, IL22, CCL7, TIMP1, CCL12, CNTF, VEGFA, GFRA1, GFRA4 | 34 | 1316 | 18520 | 8.692115144 | 1.5099E-13 | 1.5099E-13 | 2.2871E-12 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005578~proteinaceo us extracellular matrix | 6 | 0.1393081 | 7.9388E-05 | LGALS3, LGALS1, TIMP4, TIMP2, TIMP3, TIMP1 | 34 | 253 | 18520 | 12.91792606 | 0.00538405 | 0.00269566 | 0.08164213 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0009986~cell surface | 8 | 0.18574414 | 8.3982E-05 | ICAM1, NOTCH2, NOTCH1, HAVCR1, LGALS3, LGALS1, VEGFA, TIMP2 | 34 | 612 | 18520 | 7.120338331 | 0.00569472 | 0.00190185 | 0.0863644 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005604~basement membrane | 4 | 0.09287207 | 0.00059964 | VEGFA, TIMP2, TIMP3, TIMP1 | 34 | 93 | 18520 | 23.42820999 | 0.03996739 | 0.01014519 | 0.6151823 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0043235~receptor complex | 4 | 0.09287207 | 0.00165145 | NOTCH3, NOTCH2, NOTCH1, GFRA1 | 34 | 132 | 18520 | 16.50623886 | 0.10630582 | 0.02222757 | 1.68599929 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | G0:0031012~extracellula r matrix | 4 | 0.09287207 | 0.01026878 | LGALS3, LGALS1, TIMP3, TIMP1 | 34 | 254 | 18520 | 8.578045391 | 0.50435096 | 0.11039808 | 10.0744937 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0009897~external side of plasma membrane | 4 | 0.09287207 | 0.01174935 | ICAM1, LGALS3, GFRA1, GFRA3 | 34 | 267 | 18520 | 8.160387751 | 0.55232434 | 0.10846655 | 11.4488433 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005886~plasma membrane | 14 | 0.32505224 | 0.01438302 | F11R, ICAM1, LGALS3, ICAM4, GFRAL, ICAM5, ICAM2, GAS1, NOTCH3, NOTCH2, NOTCH1, GFRA1, GFRA4, GFRA3 | 34 | 3963 | 18520 | 1.924270087 | 0.62661575 | 0.11586313 | 13.8467933 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005623~cell | 3 | 0.06965405 | 0.01898445 | CXCL1, CCL12, CXCL2 | 34 | 119 | 18520 | 13.73208107 | 0.72838062 | 0.13481944 | 17.8960826 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005887~integral component of plasma membrane | 6 | 0.1393081 | 0.02446583 | ICAM1, NOTCH2, ICAM4, ICAM5, ICAM2, TCAM1 | 34 | 942 | 18520 | 3.469464219 | 0.81443802 | 0.1550152 | 22.495014 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0070062~extracellula r exosome | 10 | 0.23218017 | 0.03763242 | ICAM1, F11R, LGALS3, ICAM2, LGALS1, GFRA1, GFRA4, TIMP2, TIMP3, TIMP1 | 34 | 2646 | 18520 | 2.058601218 | 0.92634761 | 0.21110903 | 32.6067177 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0001772~immunologi cal synapse | 2 | 0.04643603 | 0.05888631 | ICAM1, LGALS3 | 34 | 34 | 18520 | 32.04152249 | 0.98386897 | 0.29101261 | 46.440432 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0043025~neuronal cell body | 4 | 0.09287207 | 0.07056971 | CCL2, CNTF, GFRA1, TIMP2 | 34 | 540 | 18520 | 4.034858388 | 0.99310167 | 0.31805473 | 52.8997324 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0031225~anchored component of membrane | 2 | 0.04643603 | 0.09356231 | GFRA1, GFRA4 | 34 | 55 | 18520 | 19.80748663 | 0.99874403 | 0.37943918 | 63.5997306 |

| Day 28 | ||||||||||||

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005615~extracellula r space | 12 | 0.26298488 | 2.1928E-07 | VEGFB, ICAM1, NRP1, CNTF, ICAM4, LGALS3, VEGFA, TIMP4, TIMP2, CCL5, TIMP3, TIMP1 | 29 | 814 | 13919 | 7.075658731 | 8.5518E-06 | 8.5518E-06 | 0.00019941 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005578~proteinaceo us extracellular matrix | 4 | 0.08766163 | 0.00409476 | TIMP4, TIMP2, TIMP3, TIMP1 | 29 | 162 | 13919 | 11.85100043 | 0.14787636 | 0.07689457 | 3.6626419 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0043235~receptor complex | 3 | 0.06574622 | 0.01401283 | NOTCH3, NOTCH2, NOTCH1 | 29 | 90 | 13919 | 15.99885057 | 0.42326116 | 0.16761087 | 12.0439761 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005887~integral component of plasma membrane | 6 | 0.13149244 | 0.01431117 | ICAM1, NOTCH2, ICAM4, ICAM5, ICAM2, JAG2 | 29 | 733 | 13919 | 3.928776403 | 0.43002802 | 0.13111284 | 12.2857025 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005912~adherens junction | 2 | 0.04383081 | 0.04336572 | NOTCH1, JAG1 | 29 | 22 | 13919 | 43.63322884 | 0.82254361 | 0.2923503 | 33.1802839 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0001772~immunologi cal synapse | 2 | 0.04383081 | 0.05677946 | ICAM1, LGALS3 | 29 | 29 | 13919 | 33.10107015 | 0.89769033 | 0.31611022 | 41.2328984 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005604~basement membrane | 2 | 0.04383081 | 0.08676185 | TIMP3, TIMP1 | 29 | 45 | 13919 | 21.33180077 | 0.97097463 | 0.3968896 | 56.1919967 |

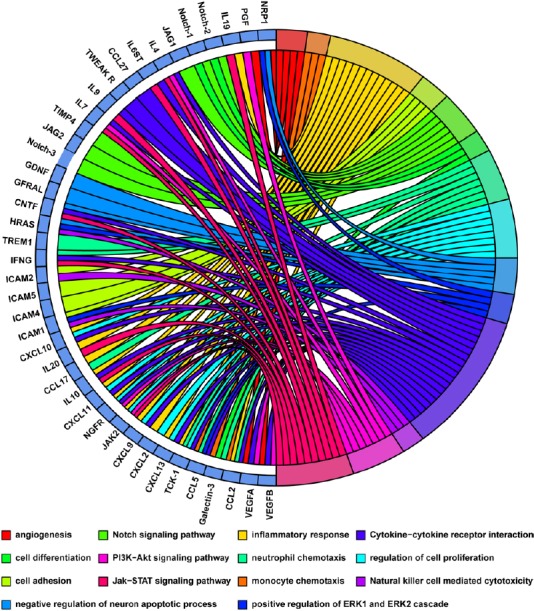

The relationships between proteins and functional terms in the distal nerve stump following sciatic nerve transection

The identified cytokines seem to affect many functional pathways and PPI networks via direct and indirect interactions. Therefore, to visualize smaller high-dimensional data subsets, the relationships between functional terms and differentially expressed proteins were assessed using the GOplot package in R (Walter et al., 2015) to integrate the expression data with the results of these analyses. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2) regulated upon activation of normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES)/CCL5 and Galectin-3 that are related to monocyte and neutrophil chemotaxis, whereas CNTF and GDNF are specific to neuronal apoptotic processes. Notch1, Notch2, and Galectin-3 may participate in cell differentiation during nerve regeneration (Figure 5). Additionally, inflammatory responses involve many cytokines, including CCL2, CCL17, CXCL2, CXCL9, CXCL11, CXCL13, NGFR, GDNF, IL10, IL20, and IL19 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The relationship between the differentially expressed proteins and functional terms (biological processes and canonical pathways) in the distal nerve stump following sciatic nerve transection.

Multiple biological processes and canonical pathways are labeled by different colors in circles on the right. The proteins linked to each term are listed in circles on the left.

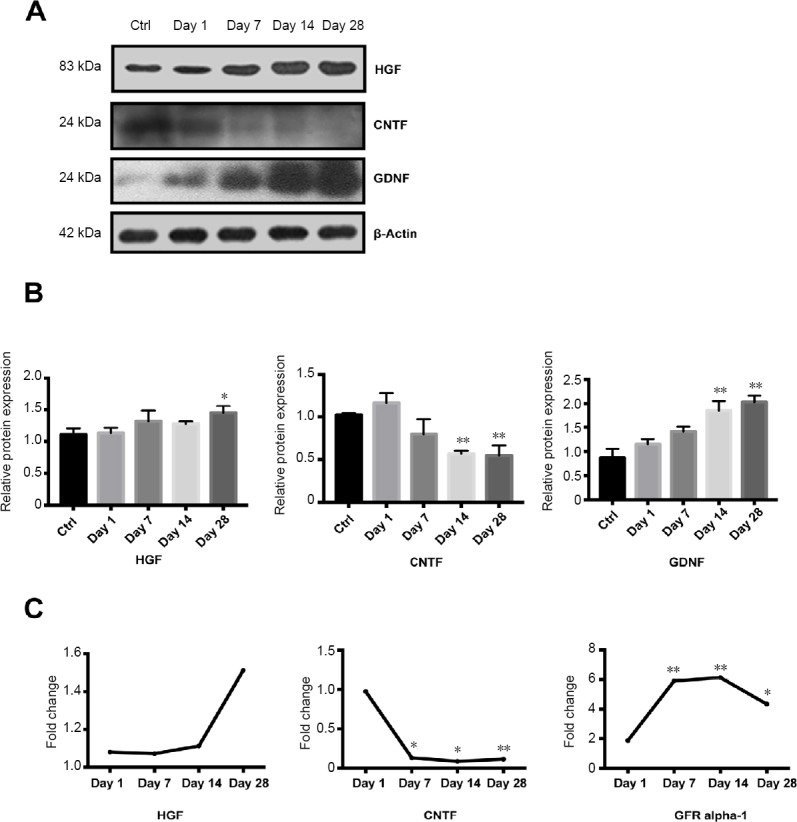

Western blot verification of the protein array results in the distal nerve stump following sciatic nerve transection

Western blot analysis was performed to validate the temporal expression patterns of the differentially expressed growth factors in the nerves identified in the microarray analyses. Western blot analysis confirmed that CNTF expression levels decreased markedly, whereas GDNF and HGF were increased after PNI (Figure 6A & B), similar to the results of microarray analyses (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Western blot analyses of the differentially expressed growth factors in the distal nerve stump following sciatic nerve transection.

(A) Protein bands of HGF, CNTF and GDNF were measured by Western blot analysis. β-Actin was used as the reference protein. (B) Quantitative result of HGF, CNTF and GDNF expression. (C) The fold changes of HGF, CNTF and GFR alpha-1 were measured by protein microarray. Data represent the mean ± SEM (n = 4) from three independent experiments, statistically analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, vs. control group (ctrl; 0 day after nerve injury). CNTF: Ciliary neurotrophic factor; GDNF: glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor; HGF: hepatocyte growth factor.

Discussion

Wallerian demyelination is the most typical cause of PNI, resulting in a series of complicated cellular responses and molecular mechanisms. Numerous studies have demonstrated that PNI induces cytokine production in immune and non-immune cells at sites distal to the nerve lesion (Karanth et al., 2006; Kiguchi et al., 2017). Such cytokines are closely related to Wallerian demyelination and participate in peripheral nerve regeneration (Rotshenker, 2011; He et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2019). In the current study protein microarray and bioinformatic analyses were performed to examine the detailed kinetic changes in cytokine production in distal nerve stumps following sciatic nerve injury.

In this study, the 67 cytokines on the protein microarray comprise growth factors, chemotaxis factors, and other proteins. By screening differentially expressed cytokines after PNI, we discovered that some growth factors may be critical for sciatic nerve injury and regeneration. For instance, previous studies reported that GFR alpha-1 is expressed in myelinated peripheral nerves and the neuromuscular junction, exerting its effects on motor neurons by interacting with GDNF (Hase et al., 1999; Rosich et al., 2017). In line with previous findings, we detected upregulation of GFR alpha-1 protein at 7, 14, and 28 days after PNI. Additionally, HGF also increased 1.5-fold at 28 days post injury. HGF has been shown to promote the migration and proliferation of Schwann cells and increase the expression of neurotrophic factors and inflammatory cytokines such as GDNF and tumor necrosis factor-α (Ko et al., 2018). In contrast, we found that CNTF was downregulated over most of the post-injury period studied. The PPI network suggested that CNTF regulates neuronal apoptosis via the JAK/STAT signaling pathway. All of these results highlight the central roles of growth factors in nerve regeneration.

Chemokine factors have been identified as important modulators of peripheral nerve regeneration (Taskinen and Röyttä, 2000). MCP-1/CCL2, a CCL family member, is expressed at low levels under basal conditions and is upregulated rapidly and markedly in Schwann cells and neurons (Schreiber et al., 2001; Tanaka et al., 2004; Niemi et al., 2013). In this study, we found that MCP-1 expression increased 10-fold from 1 to 28 days after sciatic nerve injury. Consequently, the injury-induced increase in MCP-1 may lead to recruitment of inflammatory monocytes and macrophages to nerves via the Toll-like receptor-4 or STAT3-dependent signaling pathways (Niemi et al., 2013). Moreover, other CCL family members, including RANTES/CCL5, cutaneous T-cell-attracting chemokine (CTACK)/CCL27 were also upregulated at different time points after PNI. RANTES/CCL5 is another important chemokine that exhibits strong chemoattractant activity towards monocytes and leukocytes, inducing immune cell migration and protection of neurons, either directly or indirectly (Raport et al., 1996; Tillie-Leblond et al., 2000; Tokami et al., 2013; Solga et al., 2015). CTACK was reported to accelerate skin regeneration via specific chemokine-receptor interactions (Inokuma et al., 2006), suggesting an important role of CTACK in nerve regeneration.

Notch proteins (Notch-1–4) are transmembrane receptors that regulate cellular processes, including cell proliferation, apoptosis, and angiogenesis (Bolós et al., 2007; Fortini, 2009; Kopan and Ilagan, 2009). During nerve regeneration, notch signaling mediates the differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells into Schwann-like cells and of monocytes into macrophages (Ohishi et al., 2001; Kingham et al., 2009). In our study, both Notch-1 and -2 were upregulated and may play important roles in the differentiation of the nervous system. It is also worth noting that Neuropilin-1 was upregulated from 1 to 28 days and Neuropilin-2 within 7 days after PNI. These proteins are closely related to axonal guidance, angiogenesis, and motor neuron migration. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1 (TREM1) is another protein involved in immune response signaling pathways (Collins et al., 2009; Kingham et al., 2009) and activation of TREM1 may increase the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Walter, 2016). TREM1 continually increased over the time period we examined and was related to neutrophil chemotaxis. These results suggest that a cytokine network is involved in the kinetics of macrophage recruitment and nerve removal of damaged nerves.

Bioinformatic analyses are efficient methods for interpreting proteomic or genomic information. PPI network bioinformatic data are used to predict protein functionality within sequence homology clusters (Athanasios et al., 2017). Chemotactic factors, immune factors, and other cytokines were identified in our PPI network. Thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC)/CCL17 accelerates fibroblast migration and wound healing (Kato et al., 2011). Rac GTPase, together with mammalian T-cell lymphoma invasion, metastasis factor 1 (TIAM-1) and CDC42, has been shown to mediate axon guidance (Demarco et al., 2012). These proteins may participate in nerve regeneration directly or indirectly. Additionally, the KEGG pathways resulted in the cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions keeping active during Wallerian degeneration. Other enriched pathways included the JAK/STAT, PI3K/Akt, and chemokine signaling pathways. Furthermore, our study demonstrated a diverse array of biological processes, including chemotaxis, inflammatory and immune responses, cell migration, cell proliferation, apoptosis, and angiogenesis, that were significantly activated in the distal nerve stump following sciatic nerve transection. Based on the relationships between cytokines and our bioinformatic data, further in-depth studies are needed to determine the detailed mechanism of peripheral nerve regeneration.

In summary, we analyzed global changes in cytokine expression patterns at the distal nerve stump following PNI using protein microarray analysis. Although our results did not elucidate the mechanism of PNI, bioinformatic analysis enabled us to gain a comprehensive view of cytokine expression changes with time. They also show the relationships of these cytokines with canonical pathways, biological functions, and networks during Wallerian degeneration. Overall, our study may help identify the potential clinic treatments for PNI.

Additional files:

Additional Table 1: All canonical pathways and involved molecules at 1, 7, 14, and 28 days after sciatic nerve injury.

Additional Table 2 (147KB, pdf) : All biological function categories and involved molecules at 1, 7, 14, and 28 days after sciatic nerve injury.

Additional Table 3: All cellular component categories and involved molecules at 1, 7, 14, and 28 days after sciatic nerve injury.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Financial support: This study was supported by the National Key Research & Development Program of China, No. 2017YFA0104702 (to AJS), and the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program), No. 2014CB542201 (to JP). The funders had no involvement in the study design; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; paper writing; or decision to submit the paper for publication.

Institutional review board statement: This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Chinese PLA General Hospital (approval No. 2016-x9-07) in September 2016.

Copyright license agreement: The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Data sharing statement: Datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Plagiarism check: Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review: Externally peer reviewed.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Key Research & Development Program of China, No. 2017YFA0104702 (to AJS), and the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program), No. 2014CB542201 (to JP).

C-Editor: Zhao M; S-Editors: Yu J, Li CH; L-Editors: Yu J, Song LP; T-Editor: Jia Y

References

- 1.Athanasios A, Charalampos V, Vasileios T, Ashraf GM. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network: recent advances in drug discovery. Curr Drug Metab. 2017;18:5–10. doi: 10.2174/138920021801170119204832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolós V, Grego-Bessa J, de la Pompa JL. Notch signaling in development and cancer. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:339–363. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen ZL, Yu WM, Strickland S. Peripheral regeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:209–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clements MP, Byrne E, Camarillo Guerrero LF, Cattin AL, Zakka L, Ashraf A, Burden JJ, Khadayate S, Lloyd AC, Marguerat S, Parrinello S. The wound microenvironment reprograms Schwann cells to invasive mesenchymal-like cells to drive peripheral nerve regeneration. Neuron. 2017;96:98–114.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins CE, La DT, Yang HT, Massin F, Gibot S, Faure G, Stohl W. Elevated synovial expression of triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1 in patients with septic arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1768–1774. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.089557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.da Costa CC, van der Laan LJ, Dijkstra CD, Bruck W. The role of the mouse macrophage scavenger receptor in myelin phagocytosis. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9:2650–2657. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demarco RS, Struckhoff EC, Lundquist EA. The Rac GTP exchange factor TIAM-1 acts with CDC-42 and the guidance receptor UNC-40/DCC in neuronal protrusion and axon guidance. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. DAVID: Database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fortini ME. Notch signaling: the core pathway and its posttranslational regulation. Dev Cell. 2009;16:633–647. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frostick SP, Yin Q, Kemp GJ. Schwann cells, neurotrophic factors, and peripheral nerve regeneration. Microsurgery. 1998;18:397–405. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2752(1998)18:7<397::aid-micr2>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geuna S, Raimondo S, Ronchi G, Di Scipio F, Tos P, Czaja K, Fornaro M. Chapter 3: Histology of the peripheral nerve and changes occurring during nerve regeneration. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2009;87:27–46. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(09)87003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hase A, Suzuki H, Arahata K, Akazawa C. Expression of human GFR alpha-1 (GDNF receptor) at the neuromuscular junction and myelinated nerves. Neurosci Lett. 1999;269:55–57. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00419-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He XZ, Wang W, Hu TM, Ma JJ, Yu CY, Gao YF, Cheng XL, Wang P. Peripheral nerve repair: theory and technology application. Zhongguo Zuzhi Gongcheng Yanjiu. 2016;20:1044–1050. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inokuma D, Abe R, Fujita Y, Sasaki M, Shibaki A, Nakamura H, McMillan JR, Shimizu T, Shimizu H. CTACK/CCL27 accelerates skin regeneration via accumulation of bone marrow-derived keratinocytes. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2810–2816. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karanth S, Yang G, Yeh J, Richardson PM. Nature of signals that initiate the immune response during Wallerian degeneration of peripheral nerves. Exp Neurol. 2006;202:161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kato T, Saeki H, Tsunemi Y, Shibata S, Tamaki K, Sato S. Thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC)/CC chemokine ligand (CCL) 17 accelerates wound healing by enhancing fibroblast migration. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20:669–674. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiguchi N, Kobayashi D, Saika F, Matsuzaki S, Kishioka S. Pharmacological regulation of neuropathic pain driven by inflammatory macrophages. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:E2296. doi: 10.3390/ijms18112296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kingham PJ, Mantovani C, Terenghi G. Notch independent signalling mediates Schwann cell-like differentiation of adipose derived stem cells. Neurosci Lett. 2009;467:164–168. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ko KR, Lee J, Lee D, Nho B, Kim S. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) promotes peripheral nerve regeneration by activating repair schwann cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8:8316. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26704-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kopan R, Ilagan MX. The canonical Notch signaling pathway: unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell. 2009;137:216–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin YF, Xie Z, Zhou J, Yin G, Lin HD. Differential gene and protein expression between rat tibial nerve and common peroneal nerve during Wallerian degeneration. Neural Regen Res. 2019;14:2183–2191. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.262602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luck C, DeMarco VG, Mahmood A, Gavini MP, Pulakat L. Differential regulation of cardiac function and intracardiac cytokines by rapamycin in healthy and diabetic rats. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:5724046. doi: 10.1155/2017/5724046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niemi JP, DeFrancesco-Lisowitz A, Roldan-Hernandez L, Lindborg JA, Mandell D, Zigmond RE. A critical role for macrophages near axotomized neuronal cell bodies in stimulating nerve regeneration. J Neurosci. 2013;33:16236–16248. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3319-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohishi K, Varnum-Finney B, Serda RE, Anasetti C, Bernstein ID. The Notch ligand, Delta-1, inhibits the differentiation of monocytes into macrophages but permits their differentiation into dendritic cells. Blood. 2001;98:1402–1407. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.5.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan B, Shi ZJ, Yan JY, Li JH, Feng SQ. Long non-coding RNA NONMMUG014387 promotes Schwann cell proliferation after peripheral nerve injury. Neural Regen Res. 2017;12:2084–2091. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.221168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raimondo S, Fornaro M, Tos P, Battiston B, Giacobini-Robecchi MG, Geuna S. Perspectives in regeneration and tissue engineering of peripheral nerves. Ann Anat. 2011;193:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raport CJ, Gosling J, Schweickart VL, Gray PW, Charo IF. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of a novel human CC chemokine receptor (CCR5) for RANTES, MIP-1beta, and MIP-1alpha. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17161–17166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosich K, Hanna BF, Ibrahim RK, Hellenbrand DJ, Hanna A. The effects of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34:3311–3325. doi: 10.1089/neu.2017.5175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rotshenker S. Wallerian degeneration: the innate-immune response to traumatic nerve injury. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:109. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schreiber RC, Krivacic K, Kirby B, Vaccariello SA, Wei T, Ransohoff RM, Zigmond RE. Monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 is rapidly expressed by sympathetic ganglion neurons following axonal injury. Neuroreport. 2001;12:601–606. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200103050-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siebert H, Sachse A, Kuziel WA, Maeda N, Bruck W. The chemokine receptor CCR2 is involved in macrophage recruitment to the injured peripheral nervous system. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;110:177–185. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00343-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solga AC, Pong WW, Kim KY, Cimino PJ, Toonen JA, Walker J, Wylie T, Magrini V, Griffith M, Griffith OL, Ly A, Ellisman MH, Mardis ER, Gutmann DH. RNA sequencing of tumor-associated microglia reveals Ccl5 as a stromal chemokine critical for neurofibromatosis-1 glioma growth. Neoplasia. 2015;17:776–788. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahashi K, Prinz M, Stagi M, Chechneva O, Neumann H. TREM2-transduced myeloid precursors mediate nervous tissue debris clearance and facilitate recovery in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanaka T, Minami M, Nakagawa T, Satoh M. Enhanced production of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in the dorsal root ganglia in a rat model of neuropathic pain: possible involvement in the development of neuropathic pain. Neurosci Res. 2004;48:463–469. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taskinen HS, Röyttä M. Increased expression of chemokines (MCP-1, MIP-1alpha, RANTES) after peripheral nerve transection. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2000;5:75–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8027.2000.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tillie-Leblond I, Hammad H, Desurmont S, Pugin J, Wallaert B, Tonnel AB, Gosset P. CC chemokines and interleukin-5 in bronchial lavage fluid from patients with status asthmaticus. Potential implication in eosinophil recruitment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:586–592. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.2.9907014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tokami H, Ago T, Sugimori H, Kuroda J, Awano H, Suzuki K, Kiyohara Y, Kamouchi M, Kitazono T REBIOS Investigators. RANTES has a potential to play a neuroprotective role in an autocrine/paracrine manner after ischemic stroke. Brain Res. 2013;1517:122–132. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Laan LJ, Ruuls SR, Weber KS, Lodder IJ, Dopp EA, Dijkstra CD. Macrophage phagocytosis of myelin in vitro determined by flow cytometry: phagocytosis is mediated by CR3 and induces production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and nitric oxide. J Neuroimmunol. 1996;70:145–152. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(96)00110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walter J. The triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2: a molecular link of neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:4334–4341. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.704981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walter W, Sánchez-Cabo F, Ricote M. GOplot: an R package for visually combining expression data with functional analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:2912–2914. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Webber C, Zochodne D. The nerve regenerative microenvironment: early behavior and partnership of axons and Schwann cells. Exp Neurol. 2010;223:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yi S, Tang X, Yu J, Liu J, Ding F, Gu X. Microarray and qPCR analyses of wallerian degeneration in rat sciatic nerves. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017;11:22. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yi S, Zhang H, Gong L, Wu J, Zha G, Zhou S, Gu X, Yu B. Deep sequencing and bioinformatic analysis of lesioned sciatic nerves after crush injury. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143491. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu B, Zhou S, Wang Y, Qian T, Ding G, Ding F, Gu X. miR-221 and miR-222 promote Schwann cell proliferation and migration by targeting LASS2 after sciatic nerve injury. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:2675–2683. doi: 10.1242/jcs.098996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu J, Gu X, Yi S. Ingenuity pathway analysis of gene expression profiles in distal nerve stump following nerve injury: insights into wallerian degeneration. Front Cell Neurosci. 2016;10:274. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2016.00274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.