Dendritic cells (DCs) and natural killer (NK) cells are critically involved in the early response against various bacterial microbes. Functional activation of infected DCs and NK cell-mediated gamma interferon (IFN-γ) secretion essentially contribute to the protective immunity against Chlamydia. How DCs and NK cells cooperate during the antichlamydial response is not fully understood.

KEYWORDS: Chlamydia, NK cells, dendritic cells, exosomes

ABSTRACT

Dendritic cells (DCs) and natural killer (NK) cells are critically involved in the early response against various bacterial microbes. Functional activation of infected DCs and NK cell-mediated gamma interferon (IFN-γ) secretion essentially contribute to the protective immunity against Chlamydia. How DCs and NK cells cooperate during the antichlamydial response is not fully understood. Therefore, in the present study, we investigated the functional interplay between Chlamydia-infected DCs and NK cells. Our biochemical and cell biological experiments show that Chlamydia psittaci-infected DCs display enhanced exosome release. We find that such extracellular vesicles (referred to as dexosomes) do not contain infectious bacterial material but strongly induce IFN-γ production by NK cells. This directly affects C. psittaci growth in infected target cells. Furthermore, NK cell-released IFN-γ in cooperation with tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and/or dexosomes augments apoptosis of both noninfected and infected epithelial cells. Thus, the combined effect of dexosomes and proinflammatory cytokines restricts C. psittaci growth and attenuates bacterial subversion of apoptotic host cell death. In conclusion, this provides new insights into the functional cooperation between DCs, dexosomes, and NK cells in the early steps of antichlamydial defense.

INTRODUCTION

Exosomes are membrane-enclosed vesicles of endosomal origin that are secreted by most cell types and play an important role in cell-cell communication (1). They are released via the fusion of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) with the plasma membrane. Their intracellular biogenesis, typical size (20 to 300 nm), and biophysical/biochemical properties distinguish them from other extracellular vesicles (2), such as microvesicles, apoptotic bodies, or necrotic vesicles (3). Exosomes are surrounded by a lipid bilayer and contain different types of biomolecules, including proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, and nucleic acids. They are heterogeneous and reflect the phenotypic properties of the cell type from which they are released (4). Due to inward membrane invagination of the MVB limiting membrane during biogenesis, exosomes share an outside-in topology with their producing cells, which allows physical receptor/ligand interaction with neighboring cells (3). Although reticulocytes (5), T cells (6), mast cells (7), and resting B cells (8) display induced release of exosomes, other cell types, such as macrophages (9) and dendritic cells (DCs) (10), release exosomes more continuously. Exosomes can induce immune-stimulating and/or immunosuppressive effects (11) based on their membrane-bound surface molecule composition. Immunosuppressive effects have been observed for exosomes from tumor cells, which can induce T cell apoptosis via Fas ligand (FasL/CD95L) or galectin 9 (12, 13). Moreover, through NKG2D ligands and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), exosomes are able to reduce the cytotoxic activity of NK cells and CD8+ T cells (14, 15). Further, activated T cells secrete exosomes that induce apoptosis in bystander T cells based on FasL/FasR interaction, thereby contributing to activation-induced cell death (16). Further, due to the large variety of proteins, mRNAs, and microRNAs (miRNAs) they contain, exosomes can also induce a number of immune stimulatory effects (11). For example, exosomes derived from B cells in combination with major histocompatibility complex II (MHC-II) stimulate CD4+ T cells (17). A number of chemo- and cytokines in macrophage-derived exosomes, such as CCL3, -4, and -5, as well as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), CXCL2, and interleukin-1RA (IL-1RA), induce immune stimulation in various target cells (18). In addition, pathogen-associated molecular patterns can also be packaged into exosomes of infected cells and thereby initiate the immune response more efficiently (18).

In recent years, DC-derived exosomes, also known as dexosomes, have attracted particular interest because they are functionally involved in the activation of innate and adaptive immune responses (19). Since dexosomes express functional MHC and costimulatory molecules, such as CD40, CD80, and CD86 (10), they are discussed as potent T cell activators driving the initiation and amplification of the immune response (11). Moreover, dexosomes contain various members of the TNF superfamily, such as TNF-α, FasL, and TRAIL. This allows them to kill tumor cells through FasL- and TRAIL-mediated apoptosis (20). In addition, they are able to induce NK cell-mediated gamma interferon (IFN-γ) secretion via direct binding of TNF-α to the TNF receptor of NK cells (21). Finally, NK cell activation via dexosomes has been demonstrated and can operate through various NK cell-activating ligands (22, 23).

In the present study, we sought to determine whether, and by which mechanism, dexosomes of Chlamydia-infected DCs are functionally involved in the communication/interaction between DCs and NK cells during the antichlamydial immune response. We observed that C. psittaci-infected DCs generate more MVBs and, as a consequence, release more dexosomes. These dexosomes do not contain infectious bacteria but strongly stimulate IFN-γ production and secretion by NK cells. Moreover, the combined dexosome/TNF-α/IFN-γ release by DCs and NK cells induces apoptosis in both noninfected and C. psittaci-infected epithelial cells.

RESULTS

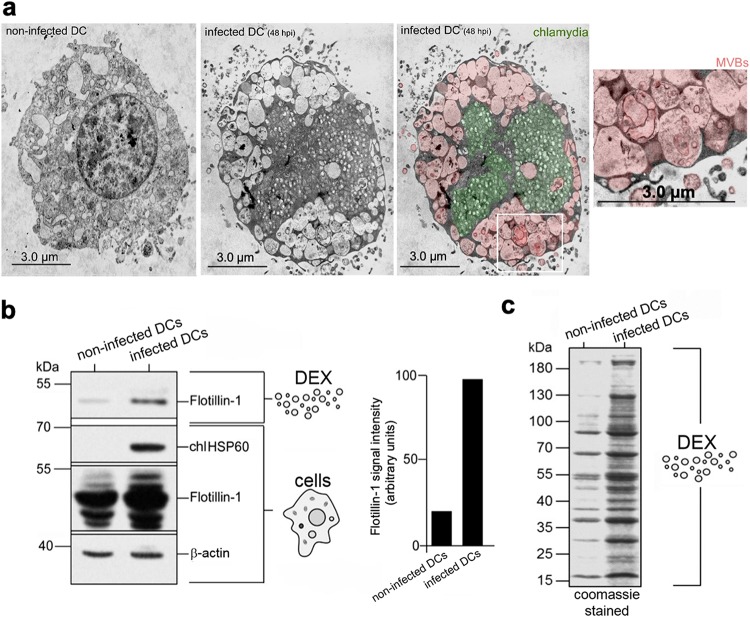

C. psittaci-infected DCs produce large numbers of dexosomes.

MVBs dramatically accumulate in C. psittaci-infected DCs (Fig. 1a). We therefore sought to determine whether this phenomenon is associated with an enhanced release of dexosomes. To address this, we used JAWSII cells (24) (an established BM-derived mouse DC line with homogeneous and consistent cell culture properties) and the nonavian C. psittaci strain DC15 (25) as a model system for infection. Dexosomes purified from supernatants of equal numbers of infected (48 h postinfection [hpi]) and noninfected DCs were analyzed for their exosomal protein content. As expected, the exosomal marker Flotillin-1 (26) was present in the supernatants of both noninfected and infected DCs (Fig. 1b). However, densitometric quantitation of the Flotillin-1 signals showed five to six times higher levels in the infected DC sample, suggesting that substantially more dexosomes were released from infected DCs than from noninfected control cells (Fig. 1b). This was further supported by the analysis of the total amount of exosomal proteins (Fig. 1c). Specifically, C. psittaci infection caused a vast release of exosomal proteins into the culture supernatant compared to noninfected DCs. Despite the observed quantitative differences, a characteristic pattern of 14 dominant exosomal proteins was virtually identical in the two samples (Fig. 1c). This suggests that C. psittaci infection leads to an augmented release of dexosomes, which apparently have a protein composition similar to those released from noninfected cells.

FIG 1.

MVB-mediated production of increased amounts of dexosomes (DEX) by infected DCs. (a) Electron photomicrographs of Chlamydia-infected DCs (MOI of 10) (middle and right panel) and noninfected DCs (left panel). Enlarged photographs show the formation of MVBs. Chlamydia is colored green; MVBs are colored red. (b) Immune blot analysis (Flotillin-1, HSP60, and β-actin) of purified dexosomes and corresponding cell lysates from noninfected and infected DCs (left). Flotillin-1 intensities of DEX were determined by densitometric blot scanning. The obtained band intensity of infected DCs was normalized to the β-actin signal and set to 100 (right). (c) Coomassie gel for the quantitative comparison of total DEX proteins released by 106 noninfected and infected DCs.

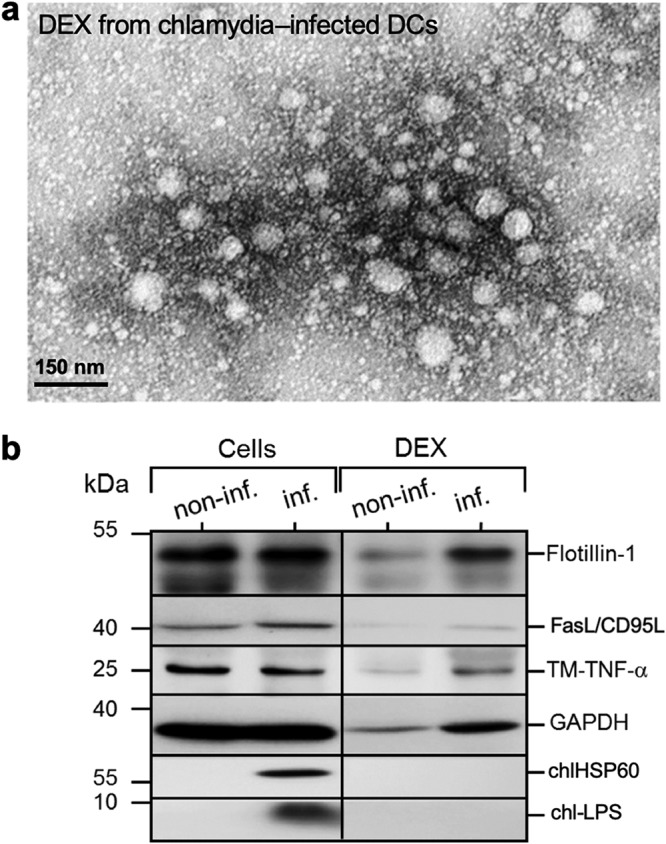

Dexosomes released by C. psittaci-infected DCs bear apoptotic triggers but no bacteria.

Next, we analyzed dexosomes released from infected DCs (48 hpi) by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis. As seen in Fig. 2a, the isolated vesicular structures have diameters between 30 and 200 nm, which matches the dimensions described for isolated dexosomes (27). It had been speculated previously that dexosomes might transport chlamydial material from infected to noninfected cells (28). However, dexosomes purified from infected DCs do not contain electronic dense bacterial structures, suggesting that they are free of Chlamydia (Fig. 1a and 2a).

FIG 2.

Microscopic and molecular characterization of dexosomes (DEX) released by infected DCs. (a) A TEM image of purified DEX prepared with ExoQuick-TC kit (System Biosciences). (b) Analysis of the detection of distinct DEX proteins. DEX were isolated from the supernatant of Chlamydia-infected DCs (MOI of 10, 48 hpi) using an ExoQuick-TC kit, lysed, and then analyzed by Western blotting with staining for Flotillin-1, FasL/CD95L, TM-TNF-α, GAPDH, Chlamydia HSP60 (chlHSP60), and LPS (chl-LPS).

In line with this, we detected no C. psittaci HSP60 or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in this material (Fig. 2b). In contrast, both transmembrane-bound TNF-α (TM-TNF-α) and Fas ligand (FasL/CD95L) were found in dexosomes from infected and noninfected DCs, in addition to the exosomal markers Flotillin-1 and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) (Fig. 2b), indicating that dexosomes may play a role in the induction of apoptosis, as well as in the control of the anti-Chlamydia immune response. The protein composition of dexosomes purified from infected DCs was analyzed in detail by mass spectrometry (MS). To this end, a metabolic stable isotope labeling approach (29) was implemented. DCs were metabolically labeled by passage in a cell culture medium containing 13C isotopomers of arginine and lysine and then infected using a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. Infected DCs were cultured in exosome-free medium, and released dexosomes were purified at 48 hpi. In this way, the presence of the heavy isotope label could be used during nanoscale liquid chromatography (nLC) matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF)/TOF MS analysis to discriminate proteins synthesized by infected DCs and Chlamydia from unlabeled contaminations originating from the cell culture medium. Identified labeled proteins were subjected to GO-term enrichment analysis (30) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), which confirmed that proteins annotated as constituents of the extracellular exosome (GO:0070062) were highly enriched (262 of 365, false discovery rate [FDR] of <10−167). Selected exosomal markers (annexin A4, CD9 antigen, HSP90, Rab7a, etc.) (31) identified by MS are listed in Table 1 , and a comprehensive list of all identified proteins is shown in Table S1. Strikingly, no Chlamydia proteins could be detected by MS analysis, confirming that dexosomes synthesized and released during C. psittaci infection of DCs do not contain significant amounts of Chlamydia proteins. Accordingly, dexosomes released from infected DCs (MOI of 10) are noninfectious to epithelial cells (Fig. 3a and b).

TABLE 1.

Selected characteristic exosomal marker proteins of purified dexosomes obtained by the GO-Annotation and ExoCarta databasesa

| Accession no. | Gene | Annotated DEX proteins |

|---|---|---|

| P63260 | Actg1 | Actin, cytoplasmic 2 |

| P97429 | Anxa4 | Annexin A4 |

| Q8VDN2 | Atp1a1 | Na/K transporting ATPase SU α-1 |

| P50516 | Atp6v1a | V-type proton ATPase catalytic SU A |

| P40240 | Cd9 | CD9 antigen |

| Q68FD5 | Cltc | Clathrin H chain |

| P10605 | Ctsb | Cathepsin B |

| P58252 | Eef2 | Elongation factor 2 |

| S4R257 | Gapdh | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| P11499 | Hsp90ab1 | Heat shock protein HSP90-β |

| G3UZD3 | Rab11b | Rab 11B |

| P35278 | Rab5c | Rab 5C |

| P51150 | Rab7a | Rab 7a |

| P99024 | Tubb5 | Tubulin β-5 chain |

A list of all identified additional exosomal proteins is shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

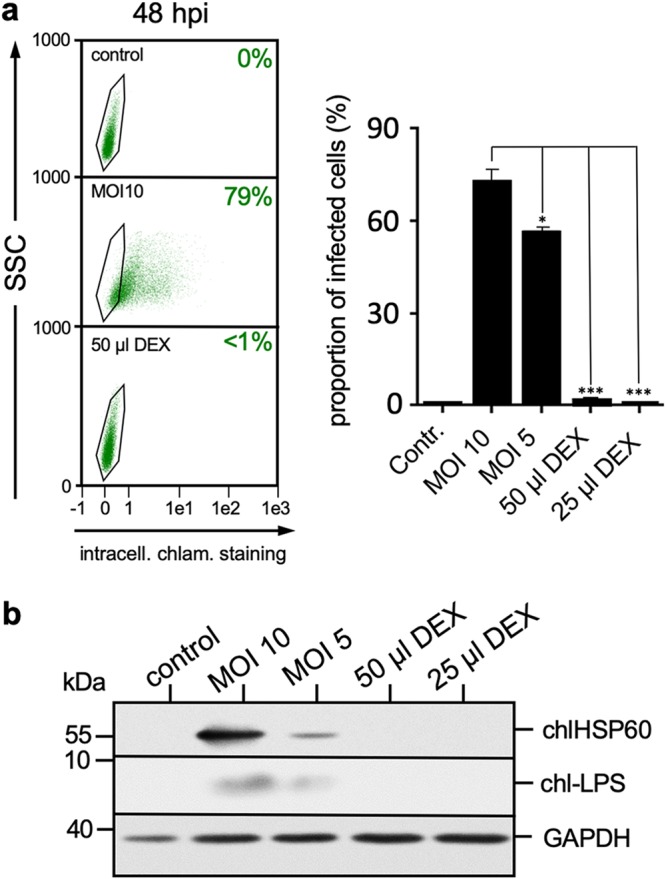

FIG 3.

Dexosomes (DEX) from infected DCs do not contain infectious Chlamydia. (a) Representative flow cytometric analysis of MN-R cell infection after DEX treatment compared to Chlamydia-infected cells (middle left panel) and noninfected cells (top left panel). The right panel shows the quantitative analysis of Chlamydia-positive MN-R cells after infection and incubation with different volumes of DEX (corresponding to 1 × 106 and 2 × 106 infected DCs, respectively). DEX were isolated from the culture supernatants of Chlamydia-infected DCs (MOI of 10, 48 hpi), resuspended in PBS, and then added to MN-R cells for 48 h. The data from three independent experiments (mean values ± the SD) are shown (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001 versus infected cells/MOI 10; n = 3). (b) Analysis of Chlamydia presence in DEX. Epithelial MN-R cells were infected with Chlamydia (MOI of 10) or incubated with DEX for 48 h. Noninfected cells were used as a negative control. The Western blot was stained for chlHSP60, chl-LPS, and GAPDH (loading control).

Taken together, these results argue against exosomal packaging and spreading of C. psittaci during DC infection (32).

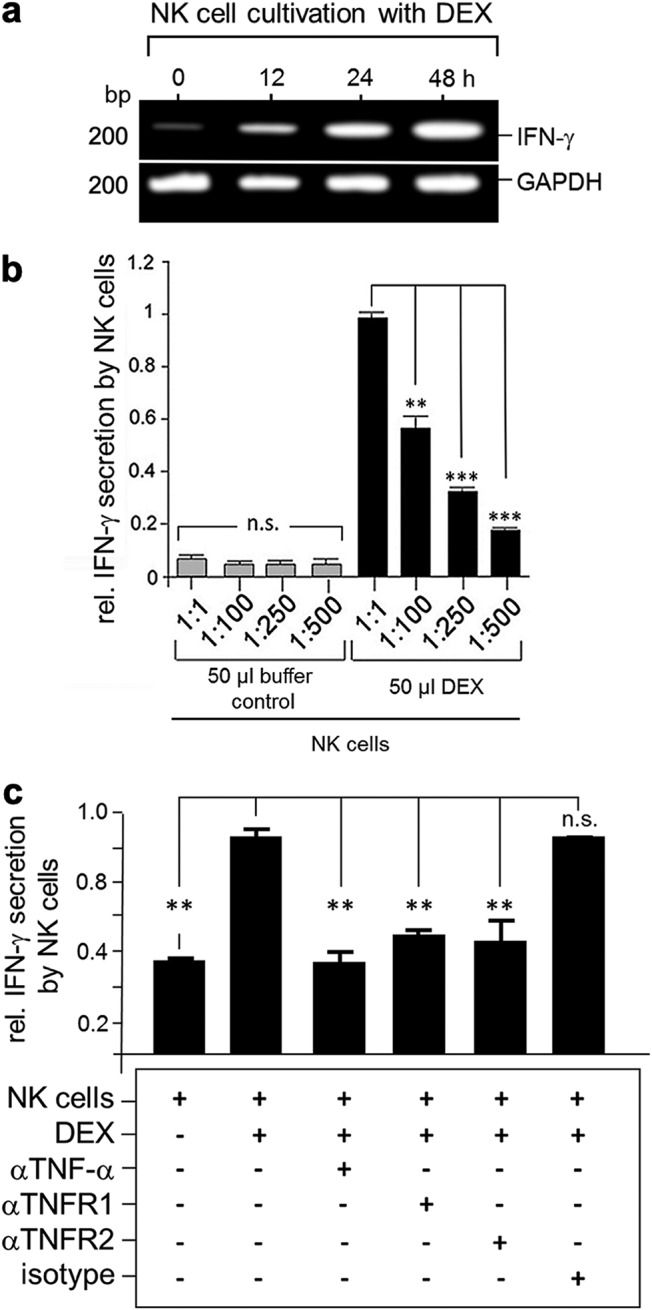

Dexosomes released from infected DCs induce IFN-γ production by NK cells.

Dexosomes released by DCs have the ability to activate NK cells via TNF/TNF receptor interaction (20, 33–35). Since both DCs and NK cells serve as an essential part of a crucial “first line of defense,” we sought to determine whether transmembrane-bound TNF-α-positive dexosomes released from C. psittaci-infected DCs (Fig. 2b) activate NK cells. To address this, immortalized mouse NK cells (KY-2, established NK cell line with homogeneous/consistent culture properties) (36) were incubated with purified dexosomes and analyzed for the induction of IFN-γ by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). Indeed, dexosome-treated NK cells profoundly upregulated the expression of IFN-γ in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 4a), suggesting a strong activation. To examine whether enhanced IFN-γ expression was associated with augmented IFN-γ secretion, NK cells were incubated with various concentrations of dexosomes purified from infected DCs. After 48 h, the NK cell-secreted cytokine was quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). As can be seen in Fig. 4b, treatment of NK cells with dexosomes indeed caused robust IFN-γ secretion and, strikingly, the extent of IFN-γ release correlated with the concentration of added dexosomes. This suggests that NK cell activation is fine-tuned depending on the amount of dexosomes to which the cells are exposed. Next, we examined whether TNF/TNF receptor interaction drives dexosome-mediated NK cell activation. To this end, an anti-TNF-α antibody that neutralizes both the soluble and the transmembrane-bound forms of TNF-α (20) was used. This antibody significantly inhibited dexosome-induced IFN-γ production by NK cells (Fig. 4c). Comparable results were also obtained with anti-TNF receptor 1 (anti-TNFR1) and anti-TNFR2 antibodies that block the interaction of TNFR1 and TNFR2 with TNF-α (Fig. 4c). Thus, in this system, NK cell activation appears to be achieved through the interaction of dexosome-bound TNF-α with NK cell-associated TNF receptor (20).

FIG 4.

Dexosomes (DEX) induce IFN-γ production and secretion by NK cells. (a) Semiquantitative PCR analysis of IFN-γ expression in NK cells. Shown are PCR amplicons of IFN-γ mRNA in DEX-treated KY-2 cells (0 to 72 h cultivation). The PCR amplification of murine GAPDH mRNA served as a loading control. (b) Relative IFN-γ secretion of DEX-treated NK cells compared to untreated cells. KY-2 cells were incubated with purified DEX from infected DCs for 48 h, whereby different dilutions of the original DEX stock were used for the NK cell stimulation. Cell-free supernatants were assessed for IFN-γ. The mean values of the optical density (OD) at 450 nm from three independent experiments ± the SD are shown. The OD for DEX-treated NK cells (dilution 1:1) was set to 1 (n.s., not significant; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 versus 1:1 ratio; n = 3). (c) DEX-bound TM-TNF mediates activation of NK cells. NK cells alone and NK cells mixed with 50 μl of DEX in the presence of a mixture of isotype control antibodies (isotype), anti-TNF antibody (αTNF-α), anti-TNFR1 (αTNFR1), or anti-TNFR2 (αTNFR2) antibodies (20 μg/ml) were incubated for 48 h. Cell-free supernatants were assessed for IFN-γ. The data from three independent experiments (mean values ± the SD) are shown (n.s., not significant; **, P < 0.01 versus NK cells/DEX; n = 3).

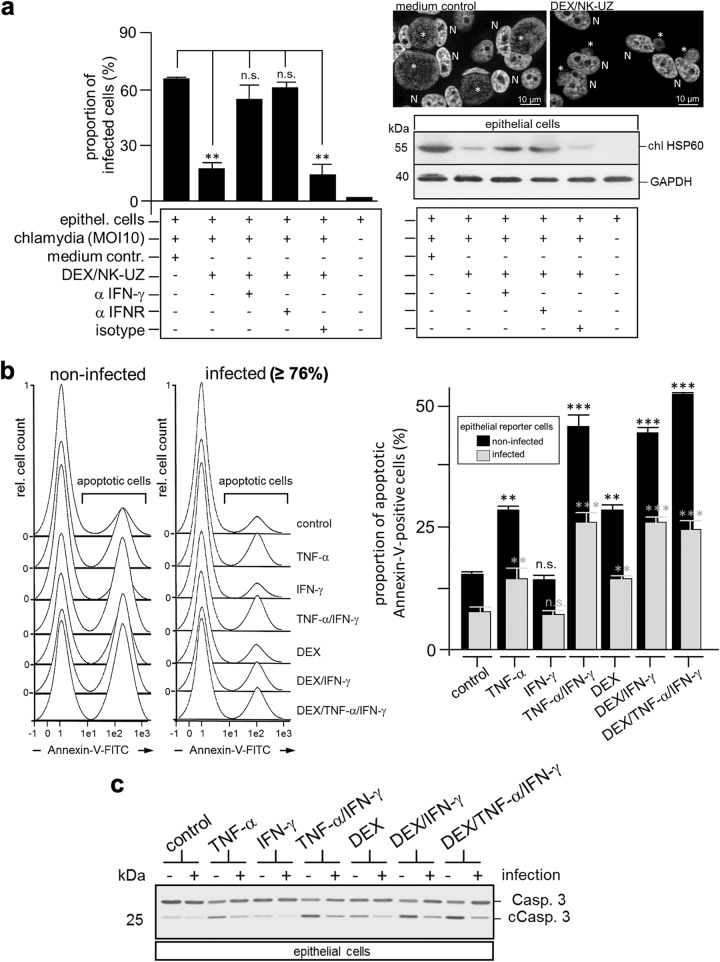

IFN-γ treatment arrests intracellular C. psittaci replication and inclusion development (25, 37, 38). Indeed, IFN-γ-containing supernatants of dexosome-activated NK cells strongly impacted C. psittaci growth in infected epithelial cells (Fig. 5). This was observed by flow cytometry (Fig. 5a, left panel), immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 5a, upper right panel), and Western blotting (Fig. 5a, lower right panel). Moreover, this effect was reversed by the addition of anti-IFN-γ and/or anti-IFN receptor (IFNR) antibodies (Fig. 5a, left and right panels).

FIG 5.

Cooperation of dexosomes (DEX), TNF-α, and IFN-γ reduces chlamydial growth and to some extent Chlamydia-mediated subversion of apoptosis. (a) IFN-γ released by DEX-activated NK cells reduces Chlamydia cell infection. NK cells were incubated with purified DEX from infected DCs for 48 h. The IFN-γ-containing culture supernatant was subjected to ultracentrifugation for the removal of DEX (DEX/NK-UZ). MN-R cells were taken up in this medium and infected with Chlamydia (MOI of 10). The infected cells were incubated for 48 h in the presence or absence of a mixture of isotype control antibodies (isotype), anti-IFN-γ antibody (αIFN-γ), or anti-IFNR (αIFNR) (20 μg/ml) and then assessed for Chlamydia infection using flow cytometry. The data from three independent experiments (mean values ± the SD) are shown (left panel) (n.s., not significant; **, P < 0.01 versus infected epithelial cells; n = 3). The cell infection following different treatments was also analyzed by immunofluorescence of DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole)-stained samples (medium control and DEX/NK-UZ; N, nucleus; asterisk, inclusion, upper right panel), as well as by Western blotting with staining for chlHSP60 and GAPDH (lower right panel). (b) Apoptosis induction in MN-R cells. Infected (MOI of 10, 12 hpi) and noninfected MN-R cells were treated with IFN-γ (100 U), TNF-α (100 U), DEX (50 μl), or different mixtures of both cytokines and DEX. After 24 h, apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry using annexin-V–FITC. The left panel shows representative flow cytometry experiments. Data from three independent experiments are summarized as bar graphs (relative amount of apoptotic cells ± the SD) (n.s., not significant; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 versus control; n = 3). (c) Caspase 3 cleavage in MN-R cells. Infected (MOI of 10, 12 hpi) and noninfected MN-R cells were treated with IFN-γ (100 U), TNF-α (100 U), DEX (50 μl), or different mixtures of both cytokines and DEX. After a further 24 h, apoptosis induction was analyzed by Western blotting staining for caspase 3 (Casp. 3) and cleaved caspase 3 (cCasp. 3) and GAPDH (loading control).

Thus, dexosomes act as a crucial trigger for NK cell-mediated IFN-γ production, which in turn suppresses chlamydial growth in infected epithelial cells.

Cooperation between DCs and NK cells via dexosomes, TNF-α, and IFN-γ attenuates bacterial subversion of apoptosis.

Chlamydia actively inhibits TNF-α-induced apoptosis at the level of TNFR1 internalization (39). Moreover, protection against apoptosis can also involve intracellular mechanisms, like the inhibition of mitochondrial cytochrome c release or the upregulation of antiapoptotic mediators (IAP and MCL-1) (40, 41). Resistance against apoptosis may be used by Chlamydia to maintain a chronic/persistent infection (42). Nevertheless, IFN-γ has a strong anti-Chlamydia effect at certain concentrations (43) and synergistically strengthens the proapoptotic activity of TNF-α (44, 45). Thus, we sought to determine whether NK cell-released IFN-γ supports the apoptosis of Chlamydia-infected epithelial cells induced via soluble and/or dexosome-associated TNF-α. Both TNF-α forms are produced by infected DCs (46, 47) (Fig. 2b). To address this question, noninfected and infected epithelial cells (murine MN-R cells) were treated with TNF-α, IFN-γ, or a 1:1 mixture of both cytokines (100 U) (Fig. 5b and c). Moreover, the effect of dexosomes alone or in combination with IFN-γ and TNF-α was analyzed (Fig. 5b and c). Annexin-V staining (Fig. 5b) and caspase-3 cleavage (Fig. 5c) served as an experimental readout for the induction of apoptosis. As shown in Fig. 5b, the treatment of epithelial cells with TNF-α and/or dexosomes alone already caused a detectable increase in the number of annexin-V-positive apoptotic cells, whereas IFN-γ treatment alone had no such effect. However, when simultaneously treated with both cytokines or with a combination of IFN-γ and dexosomes, a marked increase in the proportion of apoptotic cells was observed (Fig. 5b). As expected, based on previous studies (48), C. psittaci-infected epithelial cells displayed less apoptosis than noninfected epithelial cells (Fig. 5b). Nevertheless, the effect was observed in both situations, albeit to somewhat different extents. Intracellular costaining experiments of flow cytometry-analyzed MN-R cells with Chlamydia- and cleaved caspase 3 (cCasp. 3)-specific antibodies confirmed this observation and showed that Chlamydia exerts a well detectable antiapoptotic effect in the infected cell population (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Because triple combination treatment with dexosomes, IFN-γ, and TNF-α caused no further increase in apoptosis (Fig. 5b; see also Fig. S1), it is tempting to speculate that TNF-α and dexosomes compete for the same apoptotic pathway. In line with our findings, caspase-3 cleavage also revealed measurable apoptosis after treatment with TNF-α and/or dexosomes, which—in both cases—was increased by additional IFN-γ treatment (Fig. 5c).

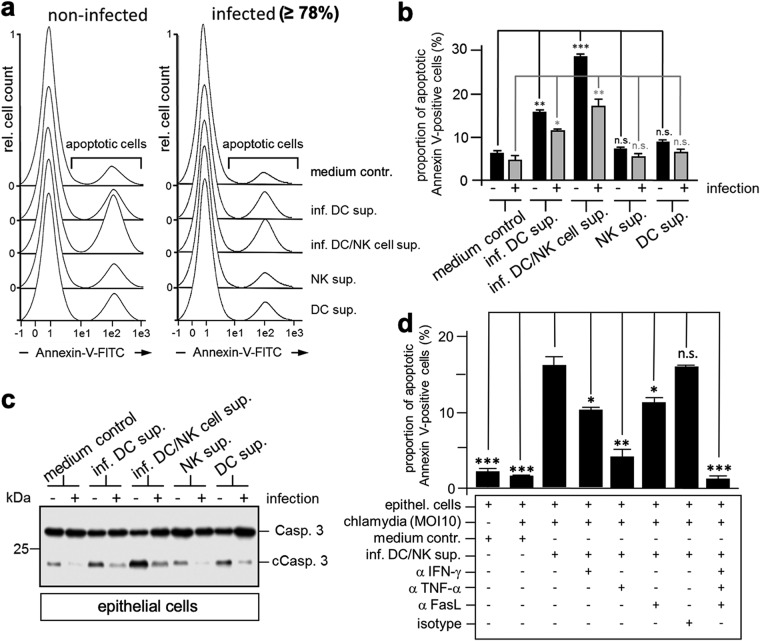

Subsequently, we investigated whether cleared (cell- and bacterium-free) supernatants derived from cocultivated infected DCs and NK cells (containing dexosomes, TNF-α, and IFN-γ) induce apoptosis in noninfected and infected epithelial cells (Fig. 6a and b). To this end, epithelial cells were incubated for 24 h with supernatants from infected DCs or infected DC/NK cocultures (Fig. 6a and b). Samples were subsequently analyzed by annexin-V surface staining (Fig. 6a and b), as well as caspase-3 cleavage assay (Fig. 6c). As shown in Fig. 6a and b, treatment of noninfected epithelial cells with culture supernatants from infected DCs triggered the induction of apoptosis. This induction was significantly enhanced when, instead, supernatants derived from infected DC/NK cocultures were used (Fig. 6a and b). As expected, for infected epithelial cells, basal apoptosis was reduced (Fig. 6a and b). Nevertheless, incubation of infected epithelial cells with culture supernatants derived from infected DCs for 24 h caused the induction of apoptotic cell death, which—again—was markedly increased when supernatants from infected DC/NK cocultures were used. Here, we could also show by flow cytometry costainings with Chlamydia- and cCasp. 3-specific antibodies that apoptosis induction appears to be detectably reduced in cells containing Chlamydia (Fig. S1). Corresponding results were obtained with caspase-3 cleavage assays (Fig. 6c). Although infected epithelial cells showed reduced caspase-3 cleavage, apoptosis was sharply enhanced in the presence of supernatants from infected DC/NK cocultures (Fig. 6c). Moreover, flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis induction in infected cells treated with DC/NK supernatants demonstrated that neutralizing anti-IFN-γ, anti-TNF-α, anti-FasL, and a mixture of these antibodies inhibited annexin-V-FITC staining by 35, 60, 30, and 85%, respectively (Fig. 6d). Thus, C. psittaci-mediated subversion of apoptosis in infected epithelial cells appears to be attenuated to a significant extent through the functional cooperation of DCs and NK cells via coordinated action of FasL-containing dexosomes, TNF-α, and IFN-γ.

FIG 6.

DCs and NK cells cooperate in the anti-Chlamydia response. (a) Effect of culture supernatants from NK cells and DCs on apoptosis of infected and noninfected epithelial cells. Infected (MOI of 10, 12 hpi) and noninfected cells were cultured in cell-free medium obtained from infected DCs (inf. DC sup.), cocultured infected DCs/noninfected NK cells (inf. DC/NK cell sup.), or noninfected DCs (DC sup.) and noninfected NK cells (NK sup.). (b) After 24 h, apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry using annexin-V–FITC. Data from three independent experiments are summarized as bar graphs (proportion of annexin-V-positive cells ± the SD) (n.s., not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 versus epithelial cells in medium control; n = 3). (c) Caspase 3 cleavage in MN-R cells. Infected (MOI of 10, 12 hpi) and noninfected MN-R cells were cultured in cell-free medium obtained from infected DCs (inf. DC sup.), cocultured infected DCs/noninfected NK cells (inf. DC/NK cell sup.), or noninfected DCs (DC sup.) and noninfected NK cells (NK sup.). After 24 h, apoptosis induction was analyzed by Western blotting with staining for caspase 3 cleavage (Casp. 3 and cCasp. 3) and GAPDH (loading control). (d) Apoptosis induction in antibody-treated MN-R cells. Infected cells (MOI of 10, 12 hpi) were incubated in the presence or absence of different neutralizing antibodies (anti-TNF-α, anti-IFN-γ, anti-FasL, or a mixture of isotype control antibodies; 20 μg/ml) with control cell culture medium or centrifuged culture medium from cocultured infected DCs/NK cells (inf. DC/NK sup.). Noninfected MN-R cells were used as control. After 24 h, apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry using annexin-V-FITC. Data from three independent experiments are summarized as bar graphs (relative amount of apoptotic cells ± the SD) (n.s., not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 versus inf. DC/NK sup.; n = 3).

DISCUSSION

Exosomes are membrane vesicles of late endosomal origin and can serve as a means of intercellular communication (1). DC-derived dexosomes have received much attention, because they harbor various immune-stimulating components (49). Our data show that C. psittaci-infected DCs release significantly more dexosomes than noninfected DCs (Fig. 1). Like other types of exosomes, dexosomes are formed through the inward invagination of the MVB limiting membrane and are released from the cell when the MVB fuses with the plasma membrane. MVBs play an essential role in autophagy, since they are required for the formation of amphisomes from autophagosomes (50, 51). Thus, exosomes are functionally and structurally linked to the auto-/xenophagic pathway (52). Enhanced exosome release by DCs may therefore be a consequence of the infection-induced upregulation of xenophagic degradation (47). In contrast to infected DCs, Chlamydia-infected epithelial cells do not show infection-induced xenophagy (47) and release fewer exosomes than noninfected controls (28). This suggests that Chlamydia as an energy/nutrient parasite affects exosome formation and/or release of infected host cells.

ESCRT (endosomal sorting complex required for transport) plays an important role in exosome biogenesis and MVB sorting (53). Bacterial recruitment of the ESCRT machinery is critical for maintaining the productive life cycle of Chlamydia (54). However, chlamydial growth is severely impaired in DCs (46). Thus, the increased formation of dexosomes by infected DCs may reflect restricted access of Chlamydia to ESCRT in this cell type and, as a consequence, full availability of ESCRT for exosome biogenesis. Russell et al. suggest that the redirection of host ATP for Chlamydia intracellular survival and metabolic activity depletes energy available for exosome generation and release (28). Hence, it is possible that the augmented release of dexosomes is also due to metabolic reprogramming of infected DCs (47, 55). This could allow host cell survival and promote killing as well as xenophagic elimination of Chlamydia. In this view, it is interesting to note that aerobic glycolysis generates ATP more rapidly than oxidative phosphorylation (56), which could facilitate exosome generation/release. Indeed, recent studies showed that enhanced exosome release is driven by increased aerobic glycolysis rates in the course of the Warburg effect (57). The main regulator in this situation seems to be the low pH in the microenvironment of the cells (caused by increased lactate release) (58), which has also been described for Chlamydia-infected DCs (47).

Exosomes may also contribute to the spread of infection and promote pathogenesis, since packaging of virulence factors in these vesicles has been observed for several bacterial pathogens (59). For instance, exosomes derived from Staphylococcus aureus-infected cells deliver alpha-toxin (also known as alpha-hemolysin) to distal sites of infection (60). Exosomes of Bacillus anthracis-infected cells transfer the virulence factor LF (lethal factor) from cell to cell, thereby protecting it from neutralization by the host’s immune system (61). In the context of Helicobacter pylori infections, it was shown that exosomes transport the virulence factor CagA to distant organs and tissues (62). For exosomes released by Chlamydia-infected epithelial cells, a role in the spread of bacterial proteins has also been postulated (28). Interestingly, in our experiments no C. psittaci proteins or intact bacteria were found in purified dexosomes of infected DCs (Fig. 2 and 3; see also Table S1). This renders it unlikely that they contribute to Chlamydia pathogenesis and/or bacterial spread. Nevertheless, dexosomes from DCs harbor substantial immunomodulatory properties and mediate essential innate immune functions, including the activation of NK cells (20). In addition to FasL and TRAIL, dexosomes also present membrane-linked TNF-α on their surface (18, 63–65). The interaction of this dexosome-associated TNF-α with the corresponding TNFR on NK cells induces the secretion of IFN-γ (20). Our study shows that dexosomes from infected DCs also contain membrane-linked TNF-α (Fig. 2b) and that they induce IFN-γ secretion by NK cells via the TNF/TNFR signaling pathway (Fig. 4). This pathway appears to operate through both TNFR1 and TNFR2 (Fig. 4), which both play a crucial role in the activation of IFN-γ production by NK cells (20, 66). The activation of NK cells can also be mediated via soluble TNF-α released by monocytes, macrophages, and/or DCs (66). However, the advantage of exosome-mediated activation could be the combined effects of various membrane-bound factors/ligands (23), potentially leading to a more effective NK cell response. We are currently interested to determine the minimum number of dexosomes per target cell that is required to induce the observed effects on NK cells.

Signaling via TNFR1 drives the main functions of TNF-α, leading to apoptosis via complex II or to cell survival via complex I (67). In contrast, TNFR2 mainly mediates signals for cell survival (68). IFN-γ enhances the apoptotic effect mediated by TNF-α by inhibiting the TNFR2/NF-κB pathway, which shifts the balance toward TNF-α-mediated proapoptotic signaling (45). Moreover, IFN-γ upregulates TNFR1, thus amplifying the apoptosis-inducing function of TNF-α (44). Even at low concentrations, IFN-γ upregulates several proapoptotic caspases and factors (69). In addition, IFN-γ may downmodulate the expression of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 (70). In line with these data, our studies demonstrate that dexosomes and/or TNF-α, in combination with IFN-γ, elevates the induction of apoptosis in both noninfected and infected epithelial cells (Fig. 5 and 6; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Chlamydia blocks TNF-α-mediated apoptosis via upregulation of Mcl-1 and cIAP-2. These factors prevent the permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane (71) and suppress caspase-3 activation (71), respectively. Moreover, it seems that TNFR1 surface expression is downregulated in epithelial cells during Chlamydia infection (72). Here, we show that the combined effect of TNF-α and IFN-γ reduces C. psittaci-mediated subversion of apoptosis (Fig. 5 and 6).

Low-dose IFN-γ treatment induces Chlamydia persistence (73). In human epithelial cells, this is mainly due to tryptophan depletion mediated by the induction of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) (74). The lack of the essential amino acid severely impairs the growth of Chlamydia strains that lack the tryptophan operon (75, 76). A similar effect has been described for TNF-α (77). The effects of TNF-α or IFN-γ on Chlamydia seem to depend on concentration and duration of exposure of the two cytokines (73, 77, 78). Thus, one could hypothesize that induced tryptophan deficiency might result either in the elimination of the pathogen or in the activation of Chlamydia persistence with host cells resisting intracellular proapoptotic stimuli (42). However, in view of the fact that mouse epithelial cells primed with IFN-γ do not induce significant IDO expression (79), restriction of C. psittaci in IFN-γ-treated MN-R cells might be predominantly driven by other IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs). Indeed, it was previously reported that one family of ISG proteins, the immunity-related GTPases, restrict C. psittaci growth in mouse and murine cells (80).

Synergistic cooperation of TNF-α and IFN-γ may have the advantage of rapidly eliminating intracellular Chlamydia (via xenophagy) and infected cells (via TNF-α-mediated apoptosis) before the bacteria can enter the persistent state. In fact, recent studies show that the premature induction of apoptosis blocks bacterial development and growth in infected cells (81).

Chlamydia as an obligate intracellular bacterium is essentially dependent on the survival of infected host cells (82). Thus, based on previous studies (83), it was not surprising that noninfected cells were more sensitive to apoptosis induction by TNF-α, IFN-γ, and dexosomes than were infected cells (Fig. 5 and 6). How could this be relevant for the anti-Chlamydia defense? One possible scenario is that the TNF-α/IFN-γ-mediated elimination of uninfected cells immediately adjacent to the site of Chlamydia infection counteracts bacterial cell-to-cell spread. Such a defense mechanism, known as the “hypersensitive response,” is commonly found in plants and acts to limit the spread of an infection (84). It is characterized by a programmed cell death response in noninfected cells surrounding the locus of infection. This depletes the pathogen of viable host cells in the vicinity and, in turn, reduces microbial dissemination (84). Most interestingly, cell-to-cell contact increases Chlamydia spread during infection (85), suggesting that chlamydiae indeed use physical cell contacts for direct pathogen transmission. This is in line with our own observations that in epithelial cell cultures a significant amount of Chlamydia infection/spread (up to 25%) is mediated via physical cell-to-cell contact (data not shown). In this context, it is interesting to note that TNF-α triggers apoptosis of noninfected cells in Chlamydia-infected tissues (86, 87). When this is reversed by cytokine blockade (88), an increase in Chlamydia infection is observed (89).

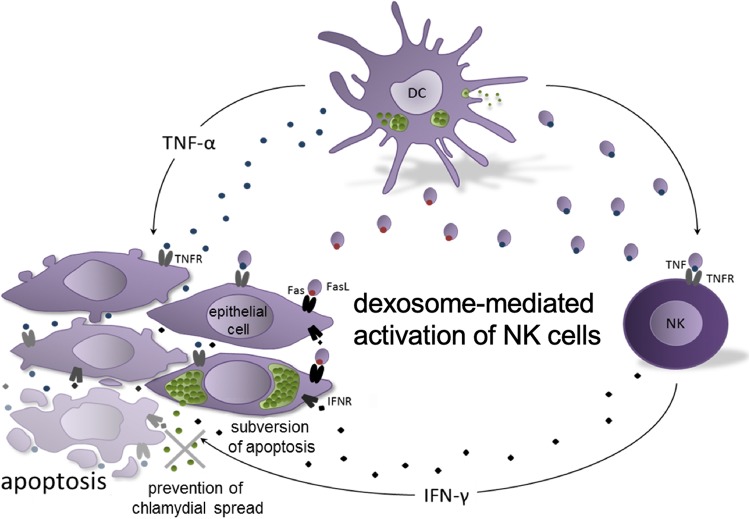

Based on our findings we postulate the following working model (Fig. 7). DCs and NK cells are among the first immune cells involved in counteracting a Chlamydia infection and spreading. Both cell types are known to be less permissive to the developmental cycle of Chlamydia than other cell types, resulting in impaired bacterial growth and reduced production of infectious elementary bodies (EBs) (90, 91). During the course of DC infection, increased biogenesis of MVBs is directly coupled to increased formation and release of exosomal vesicles (dexosomes). These dexosomes contain FasL/CD95L and transmembrane-bound TNF-α on their membrane surfaces and are able to kill epithelial cells by induction of apoptosis. This is observed for noninfected target cells and, to a lesser extent, for infected target cells. Interaction of membrane-linked TNF-α with corresponding TNFRs on neighboring NK cells leads to massive IFN-γ production and secretion. This reduces chlamydial growth in infected cells and synergistically increases the weak apoptotic effect of TNF-α and dexosomes (secreted by infected DCs) on both infected cells and surrounding noninfected epithelial cells. Thus, the combined effect of dexosomes, TNF-α, and IFN-γ produced by the early arbiters of innate immunity may control the cell-to-cell spread of Chlamydia at early steps of local infection when the number of pathogens and infected cells is low. The joint forces of the early defense may thus reduce intracellular chlamydial growth and the numbers of available living host cells at the immediate site of infection, as well as the subversive Chlamydia resistance to apoptosis.

FIG 7.

Postulated working model for the role of dexosomes during chlamydial cell infection. The combinatorial effects of dexosomes, IFN-γ, and TNF-α released by infected DCs and neighboring NK cells restrict chlamydial growth/spreading and attenuate bacterial subversion of programmed cell death. The different steps of the working model are described in detail in the Discussion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

The murine NK cell clone KY-2 (36) (kindly provided by W. Yokoyama, Washington University School of Medicine) was cultivated at 37°C and 7.5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), β-mercaptoethanol (10 μM), and 200 U/ml IL-2. Depending on growth rate and cell density, the cells were passaged every 3 to 5 days. Immortalized epithelial cells from newborn mice (MN-R cells) were obtained from the Collection of Cell Lines in Veterinary Medicine (CCLV) of the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut (CCLV-RIE 282). Cells were grown at 37°C and 7.5% CO2 in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM) cell culture medium with 5% FCS. JAWSII cells (24) were cultured as described before (46).

Antibodies.

Antibodies against Flotillin-1, β-actin, FasL/CD95L, TNF-α/TM-TNF-α, GAPDH, caspase 3/cleaved caspase 3, IFN-γ, IFNR, TNFR1, and TNFR2 were obtained from Abcam, R&D, and Cell Signaling. Anti-Chlamydia HSP60 and LPS antibodies were purchased from Acris and Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Secondary and isotype control antibodies were purchased from Abcam, Dianova, Thermo Fisher, and BioLegend.

Western blotting.

Cells were lysed on ice in RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 1% NP-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, complete protease inhibitor [Roche], 50 mM NaF) with 4 M urea. After centrifugation (14,000 rpm, 30 min, 4°C), postnuclear supernatants were analyzed by Western blotting as previously described (91). The SDS-PAGE protein markers used were from Serva and Thermo Fisher Scientific. Fluorographs were scanned and quantified with GelEval 1.32 (FrogDance Software).

Chlamydia.

The nonavian C. psittaci strain DC15 (92) was grown in MN-R cells with chlamydial EBs and reticular bodies (RBs) purified by discontinuous density gradient ultracentrifugation using Visipaque (Nycomed). Briefly, MN-R cells were cultivated in antibiotic-free confluent cultures and infected at an MOI of 10. After 48 h cultivation at 37°C and 7.5% CO2, Chlamydia-containing cells were harvested, and the bacterial suspension was sonicated three times for 10 s at 100 W in an ultrasonic bath. After centrifugation (4,000 × g, 3 min, 4°C), the supernatant was carefully transferred to ultracentrifuge tubes. Then, the suspension was underlaid with Visipaque solutions of different concentrations (2 ml of 8% solution and 3 ml of 15% solution, followed by 5 ml of 30% solution). Afterwards, the tubes were centrifuged at 40,000 × g for 50 min at 4°C. The pellet fraction was resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and used in a second ultracentrifugation whereby the obtained fraction was again carefully underlaid with different Visipaque solutions (1 ml 8%, 1 ml 15%, 1 ml 30%, 12 ml 36%, 8 ml 40%, and 5 ml 47%). After the second ultracentrifugation (50,000 × g, 50 min, 4°C), EBs were found between the 40 and 47% layer, while RBs were located in the 36% layer. Fractions containing EBs and RBs were diluted in PBS and centrifuged again (30,000 × g, 50 min, 4°C). Finally, pellets of enriched EBs and RBs were resuspended in sucrose-phosphate-glutamic acid buffer and stored at –70°C. The purification/enrichment of EBs and RBs in the two fractions was visualized and checked by TEM. Infection-forming units (IFU) were determined by immunostaining (IMAGEN kit; Oxoid). Unless indicated otherwise, cells were infected with EBs at an MOI of 10. The percentages of infected cells in culture were determined by flow cytometry.

TEM analysis of cells.

For electron microscopy, cell culture supernatants of JAWSII cells were replaced by 2.5% glutaraldehyde in cacodylate buffer (0.1 M [pH 7.2]) at 48 hpi. After 2 h of fixation at 4°C, the cells were gently scraped from the cell culture dish and centrifuged for 5 min at 1,500 × g. The pellet was embedded in 2% agarose and sectioned into 1-mm3 cubes. Cubes were postfixed in 2% osmium tetroxide and embedded in Araldite Cy212. Ultrathin sections (85 nm) were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined by TEM (Tecnai 12; FEI) (46).

Isolation of dexosomes.

For the isolation and purification of dexosomes from the culture supernatant of infected and noninfected DCs (JAWSII cells), a culture medium containing 106 cells was centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 15 min at room temperature. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and then supplemented with 2 ml of ExoQuick solution (System Biosciences). The mixture was mildly homogenized by inversion and then incubated overnight at 4°C. Then, centrifugation was initially performed at 1,500 × g for 30 min at room temperature. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet fraction was resuspended and centrifuged for 5 min at 1,500 × g at room temperature. Finally, the exosome pellet was taken up in 200 μl of PBS and stored at –20°C for further use and analysis.

TEM analysis of dexosomes.

Prior to further cell biological and immunological analysis, isolated dexosomes were evaluated for morphology by TEM. For the TEM analysis of dexosomes, the negative contrasting method was used. Therefore, the sample was placed on a 400-mesh nickel net and incubated for 7 min. The sample was then aspirated, and phosphotungstic acid (pH 6.0) was applied to the mesh as a contrast medium. This was followed by another incubation for 7 min and subsequent aspiration of the contrast medium. After the net had dried, the dexosomes were analyzed using Tecnai-Spirit TEM (FEI) at an acceleration voltage of 80 kV.

Mass spectrometric analysis of dexosomes.

For MS analysis of dexosomes, DCs (JAWSII cells) were metabolically labeled. To achieve this, cells were grown in arginine/lysine-free IMDM (IMDM for SILAC; Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 5% exosome-depleted FCS and the 13C-labeled isotopomers of arginine (0.398 mM) and lysine (0.798 mM) (Silantes). After complete isotope exchange, 5 × 106 cells were infected with C. psittaci (MOI of 10) and, at 48 hpi, the dexosomes were isolated from the culture supernatant as described above. After centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 90 min at 4°C, the final exosome pellet was resuspended in SDS buffer (0.1 M Tris/HCl [pH 8.0], 0.1 M dithiothreitol, 2% SDS) and incubated at 99°C for 5 min (93). Exosomal lysates were digested with trypsin (Promega) according to the FASP protocol (94) and purified using Vivacon 500 filter units (30-kDa cutoff; Sartorius). The generated peptides were desalted via Empore HP extraction disk cartridges (C18-SD; 3M) and analyzed using an nLC-MALDI-TOF-MS/MS platform (EASY-nLC II, FcII sample spotting robot, and an UltrafleXtreme MALDI-TOF/TOF instrument; Bruker) (95). Here, 4 μg of the digested protein samples was diluted in 10 μl 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and injected into an NS-MP-10 BioSphere loading/desalting column (C18 column from NanoSeparations). After a washing step with 0.05% TFA, elution was performed by using an analytical column (Acclaim Pepmap; Thermo Fisher) at a constant flow rate of 300 nl/min with a binary linear gradient of buffers A (0.05% TFA) and B (90% acetonitrile, 0.05% TFA). During the 64-min run, the gradient composition was changed from 2% B to 45% B. Fractions (50 nl) were collected on a 384 spot anchor chip target plate (Bruker). Eluates were finally mixed with 416 nl of α-cyano-4-hydroxy cinnamic acid/fraction. The maximum number of fragment spectra per spot to be examined was set to 40, and the signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio for the MS spectra was 7. The fragment spectra were analyzed with MASCOT server (v2.4.1; Matrixscience) with the following parameters: peptide mass tolerance, 25 ppm (MS); fragment mass tolerance, 0.7 Da (MS/MS); one missing trypsin site was tolerated; oxidation of methionine was set as variable modification; carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues was set as fixed modification; and a sequence database comprising the mouse and the C. psittaci (DC15) proteome was downloaded from UniProt (96). To exclude peptides arising from the digest of contaminating proteins from the medium, 13C modifications of arginine and lysine were set as fixed modifications. The minimal MASCOT peptide score for the evaluation of the results by ProteinExtractor software (ProteinScape platform; Bruker) was set to 15, and the significance level was set to 0.05. The results of the database query were exported to the ProteinScape software (Bruker) for further analysis. Only proteins identified by a minimum of two peptides are reported.

GO-term enrichment analysis.

UniProt protein identifiers were converted into gene names for GO-term enrichment analysis (http://www.geneontology.org, released 2 February 2019, complete GO cellular component) using the PANTHER overrepresentation test (all human genes, release 17 May 2019) (30, 97). A Fisher exact test was used, together with FDR calculation.

RT-PCR.

Total RNA from NK cells (KY-2) treated with dexosomes (0 to 48 h) was isolated and analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR. The respective PCR primer pairs were 5′-AAGACAATCAGGCCATCAGCA-3′/5′-CGAATCAGCAGCGACTCCTT-3′ (mouse IFN-γ and NK cell activation) and 5′-CACCTTCGATGCCGGGGCTG-3′/5′-TGTTGGGGGCCGAGTTGGGA-3′ (mouse GAPDH and loading control). The MassRuler DNA ladder from Thermo Fisher Scientific was used as a molecular weight marker in 1% agarose gels. For semiquantification of the PCR amplificates, digital images of agarose gels were densitometrically analyzed by using the software ImageStudioLite 4.0.2.1 (LI-COR Biosciences).

Flow cytometry and colorimetry.

Flow cytometry was performed as described previously (91). Cells were analyzed on a MACSQuant analyzer (Miltenyi Biotec). Viability was assessed with trypan blue. For Chlamydia staining and titer determination, the cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in PBS–0.5% saponin–0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at room temperature for 30 min and immunostained with an IMAGEN kit (Oxoid).

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

For fluorescence microscopy, cells were grown on coverslips and fixed for 20 min in 2% paraformaldehyde, quenched with 3% BSA, permeabilized with 0.1% saponin (Sigma-Aldrich), and incubated serially with the indicated primary and corresponding secondary antibodies. Images were taken with an Axiovert 200 M/ApoTome microscope and a confocal Exciter laser scanning microscope (Zeiss) (91).

IFN-γ ELISA.

To detect IFN-γ quantitatively in the cell culture supernatant of Chlamydia-infected or noninfected NK cells, the IFN-γ Platinum ELISA from eBioscience was used. For the analysis, 105 primary and immortalized NK cells were cultured in 12-well plates and infected with Chlamydia for 24 to 72 h. Cell culture supernatants (50 μl of undiluted supernatant, as well as 1:100 and 1:500 dilutions in PBS) were analyzed by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The colorimetric reactions were measured at a wavelength of 450 nm on a Sunrise remote ELISA reader (Tecan).

Statistical analysis.

Analysis results for the obtained data are presented as means ± the standard deviations (SD) of three individual experiments and were estimated using Prism 6 (GraphPad Software). Data were analyzed using t test and one-way analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett’s and/or Tukey’s post hoc test (n.s., not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ralf M. Leonhardt and Allison Groseth for helpful comments and critically reading the manuscript. Petra Meyer and Mandy Jörn are acknowledged for their technical assistance.

The Priority Program SPP1580 of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft is gratefully acknowledged for financial support.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bang C, Thum T. 2012. Exosomes: new players in cell-cell communication. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 44:2060–2064. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Niel G, D’Angelo G, Raposo G. 2018. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19:213–228. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. 2013. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol 200:373–383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kowal J, Arras G, Colombo M, Jouve M, Morath JP, Primdal-Bengtson B, Dingli F, Loew D, Tkach M, Théry C. 2016. Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:E968–E977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521230113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan BT, Teng K, Wu C, Adam M, Johnstone RM. 1985. Electron microscopic evidence for externalization of the transferrin receptor in vesicular form in sheep reticulocytes. J Cell Biol 101:942–948. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.3.942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanchard N, Lankar D, Faure F, Regnault A, Dumont C, Raposo G, Hivroz C. 2002. TCR activation of human T cells induces the production of exosomes bearing the TCR/CD3/zeta complex. J Immunol 168:3235–3241. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raposo G, Tenza D, Mecheri S, Peronet R, Bonnerot C, Desaymard C. 1997. Accumulation of major histocompatibility complex class II molecules in mast cell secretory granules and their release upon degranulation. Mol Biol Cell 8:2631–2645. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.12.2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saunderson SC, Schuberth PC, Dunn AC, Miller L, Hock BD, MacKay PA, Koch N, Jack RW, McLellan AD. 2008. Induction of exosome release in primary B cells stimulated via CD40 and the IL-4 receptor. J Immunol 180:8146–8152. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.8146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatnagar S, Shinagawa K, Castellino FJ, Schorey JS. 2007. Exosomes released from macrophages infected with intracellular pathogens stimulate a proinflammatory response in vitro and in vivo. Blood 110:3234–3244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-079152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zitvogel L, Regnault A, Lozier A, Wolfers J, Flament C, Tenza D, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Raposo G, Amigorena S. 1998. Eradication of established murine tumors using a novel cell-free vaccine: dendritic cell-derived exosomes. Nat Med 4:594–600. doi: 10.1038/nm0598-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thery C, Ostrowski M, Segura E. 2009. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 9:581–593. doi: 10.1038/nri2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andreola G, Rivoltini L, Castelli C, Huber V, Perego P, Deho P, Squarcina P, Accornero P, Lozupone F, Lugini L, Stringaro A, Molinari A, Arancia G, Gentile M, Parmiani G, Fais S. 2002. Induction of lymphocyte apoptosis by tumor cell secretion of FasL-bearing microvesicles. J Exp Med 195:1303–1316. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klibi J, Niki T, Riedel A, Pioche-Durieu C, Souquere S, Rubinstein E, Le Moulec S, Moulec SLE, Guigay J, Hirashima M, Guemira F, Adhikary D, Mautner J, Busson P. 2009. Blood diffusion and Th1-suppressive effects of galectin-9-containing exosomes released by Epstein-Barr virus-infected nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Blood 113:1957–1966. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-142596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu C, Yu S, Zinn K, Wang J, Zhang L, Jia Y, Kappes JC, Barnes S, Kimberly RP, Grizzle WE, Zhang HG. 2006. Murine mammary carcinoma exosomes promote tumor growth by suppression of NK cell function. J Immunol 176:1375–1385. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clayton A, Mitchell JP, Court J, Linnane S, Mason MD, Tabi Z. 2008. Human tumor-derived exosomes downmodulate NKG2D expression. J Immunol 180:7249–7258. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monleon I, Martinez-Lorenzo MJ, Monteagudo L, Lasierra P, Taules M, Iturralde M, Pineiro A, Larrad L, Alava MA, Naval J, Anel A. 2001. Differential secretion of Fas ligand- or APO2 ligand/TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-carrying microvesicles during activation-induced death of human T cells. J Immunol 167:6736–6744. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.6736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muntasell A, Berger AC, Roche PA. 2007. T cell-induced secretion of MHC class II–peptide complexes on B cell exosomes. EMBO J 26:4263–4272. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDonald MK, Tian Y, Qureshi RA, Gormley M, Ertel A, Gao R, Aradillas Lopez E, Alexander GM, Sacan A, Fortina P, Ajit SK. 2014. Functional significance of macrophage-derived exosomes in inflammation and pain. Pain 155:1527–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robbins PD, Morelli AE. 2014. Regulation of immune responses by extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Immunol 14:195–208. doi: 10.1038/nri3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munich S, Sobo-Vujanovic A, Buchser WJ, Beer-Stolz D, Vujanovic NL. 2012. Dendritic cell exosomes directly kill tumor cells and activate natural killer cells via TNF superfamily ligands. Oncoimmunology 1:1074–1083. doi: 10.4161/onci.20897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reiners KS, Dassler J, Coch C, Pogge von Strandmann E. 2014. Role of exosomes released by dendritic cells and/or by tumor targets: regulation of NK cell plasticity. Front Immunol 5:91. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simhadri VR, Reiners KS, Hansen HP, Topolar D, Simhadri VL, Nohroudi K, Kufer TA, Engert A, Pogge von Strandmann E. 2008. Dendritic cells release HLA-B-associated transcript-3 positive exosomes to regulate natural killer function. PLoS One 3:e3377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Viaud S, Terme M, Flament C, Taieb J, Andre F, Novault S, Escudier B, Robert C, Caillat-Zucman S, Tursz T, Zitvogel L, Chaput N. 2009. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes promote natural killer cell activation and proliferation: a role for NKG2D ligands and IL-15Rα. PLoS One 4:e4942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang X, Shen C, Rey-Ladino J, Yu H, Brunham RC. 2008. Characterization of murine dendritic cell line JAWS II and primary bone marrow-derived dendritic cells in Chlamydia muridarum antigen presentation and induction of protective immunity. Infect Immun 76:2392–2401. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01584-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goellner S, Schubert E, Liebler-Tenorio E, Hotzel H, Saluz HP, Sachse K. 2006. Transcriptional response patterns of Chlamydophila psittaci in different in vitro models of persistent infection. Infect Immun 74:4801–4808. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01487-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trajkovic K, Hsu C, Chiantia S, Rajendran L, Wenzel D, Wieland F, Schwille P, Brugger B, Simons M. 2008. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science 319:1244–1247. doi: 10.1126/science.1153124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hannafon BN, Ding WQ. 2013. Intercellular communication by exosome-derived microRNAs in cancer. Int J Mol Sci 14:14240–14269. doi: 10.3390/ijms140714240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russell S, Ryans K, Huang MB, Omosun Y, Khan M, Powell MD, Igietseme JU, Eko FO. 2018. Chlamydia infection-derived exosomes possess immunomodulatory properties capable of stimulating dendritic cell maturation. JAMMR 25:1–15. doi: 10.9734/JAMMR/2018/38821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ong SE, Blagoev B, Kratchmarova I, Kristensen DB, Steen H, Pandey A, Mann M. 2002. Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture, SILAC, as a simple and accurate approach to expression proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics 1:376–386. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200025-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The Gene Ontology C. 2019. The gene ontology resource: 20 years and still GOing strong. Nucleic Acids Res 47:D330–D338. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keerthikumar S, Chisanga D, Ariyaratne D, Al Saffar H, Anand S, Zhao K, Samuel M, Pathan M, Jois M, Chilamkurti N, Gangoda L, Mathivanan S. 2016. ExoCarta: a Web-based compendium of exosomal cargo. J Mol Biol 428:688–692. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frohlich K, Hua Z, Wang J, Shen L. 2012. Isolation of Chlamydia trachomatis and membrane vesicles derived from host and bacteria. J Microbiol Methods 91:222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borg C, Jalil A, Laderach D, Maruyama K, Wakasugi H, Charrier S, Ryffel B, Cambi A, Figdor C, Vainchenker W, Galy A, Caignard A, Zitvogel L. 2004. NK cell activation by dendritic cells (DCs) requires the formation of a synapse leading to IL-12 polarization in DCs. Blood 104:3267–3275. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vujanovic L, Szymkowski DE, Alber S, Watkins SC, Vujanovic NL, Butterfield LH. 2010. Virally infected and matured human dendritic cells activate natural killer cells via cooperative activity of plasma membrane-bound TNF and IL-15. Blood 116:575–583. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-240325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas R, Yang X. 2016. NK-DC crosstalk in immunity to microbial infection. J Immunol Res 2016:6374379. doi: 10.1155/2016/6374379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karlhofer FM, Orihuela MM, Yokoyama WM. 1995. Ly-49-independent natural killer (NK) cell specificity revealed by NK cell clones derived from p53-deficient mice. J Exp Med 181:1785–1795. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.5.1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCafferty MC, Maley SW, Entrican G, Buxton D. 1994. The Importance of interferon-gamma in an early infection of Chlamydia psittaci in mice. Immunology 81:631–636. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graham SP, Jones GE, Maclean M, Livingstone M, Entrican G. 1995. Recombinant ovine interferon-gamma inhibits the multiplication of Chlamydia psittaci in ovine cells. J Comp Pathol 112:185–195. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9975(05)80060-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waguia Kontchou C, Tzivelekidis T, Gentle IE, Häcker G. 2016. Infection of epithelial cells with Chlamydia trachomatis inhibits TNF-induced apoptosis at the level of receptor internalization while leaving non-apoptotic TNF-signaling intact. Cell Microbiol 18:1583–1595. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rajalingam K, Sharma M, Paland N, Hurwitz R, Thieck O, Oswald M, Machuy N, Rudel T. 2006. IAP-IAP complexes required for apoptosis resistance of Chlamydia trachomatis-infected cells. PLoS Pathog 2:e114. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rajalingam K, Sharma M, Lohmann C, Oswald M, Thieck O, Froelich CJ, Rudel T. 2008. Mcl-1 is a key regulator of apoptosis resistance in Chlamydia trachomatis-infected cells. PLoS One 3:e3102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rödel J, Grosse C, Yu HX, Wolf K, Otto GP, Liebler-Tenorio E, Forsbach-Birk V, Straube E. 2012. Persistent Chlamydia trachomatis infection of HeLa cells mediates apoptosis resistance through a Chlamydia protease-like activity factor-independent mechanism and induces high mobility group box 1 release. Infect Immun 80:195–205. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05619-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Finethy R, Coers J. 2016. Sensing the enemy, containing the threat: cell-autonomous immunity to Chlamydia trachomatis. FEMS Microbiol Rev 40:875–893. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuw027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bode L, Murch S, Freeze HH. 2006. Heparan sulfate plays a central role in a dynamic in vitro model of protein-losing enteropathy. J Biol Chem 281:7809–7815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510722200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y, Wang L, Kikuiri T, Akiyama K, Chen C, Xu X, Yang R, Chen W, Wang S, Shi S. 2011. Mesenchymal stem cell-based tissue regeneration is governed by recipient T lymphocytes via IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha. Nat Med 17:1594–1601. doi: 10.1038/nm.2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fiegl D, Kägebein D, Liebler-Tenorio EM, Weisser T, Sens M, Gutjahr M, Knittler MR. 2013. Amphisomal route of MHC class I cross-presentation in bacterium-infected dendritic cells. J Immunol 190:2791–2806. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Radomski N, Rebbig A, Leonhardt RM, Knittler MR. 2018. Xenophagic pathways and their bacterial subversion in cellular self-defense—παντα ρει—everything is in flux. Int J Med Microbiol 308:185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Byrne GI, Ojcius DM. 2004. Chlamydia and apoptosis: life and death decisions of an intracellular pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol 2:802–808. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pitt JM, Charrier M, Viaud S, Andre F, Besse B, Chaput N, Zitvogel L. 2014. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes as immunotherapies in the fight against cancer. J Immunol 193:1006–1011. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hessvik NP, Llorente A. 2018. Current knowledge on exosome biogenesis and release. Cell Mol Life Sci 75:193–208. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2595-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fader CM, Colombo MI. 2009. Autophagy and multivesicular bodies: two closely related partners. Cell Death Differ 16:70–78. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.You L, Mao L, Wei J, Jin S, Yang C, Liu H, Zhu L, Qian W. 2017. The crosstalk between autophagic and endo-/exosomal pathways in antigen processing for MHC presentation in anticancer T cell immune responses. J Hematol Oncol 10:165. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0534-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Juan T, Furthauer M. 2018. Biogenesis and function of ESCRT-dependent extracellular vesicles. Semin Cell Dev Biol 74:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vromman F, Perrinet S, Gehre L, Subtil A. 2016. The DUF582 proteins of Chlamydia trachomatis bind to components of the ESCRT machinery, which is dispensable for bacterial growth in vitro. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 6:123. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McKeithen DN, Omosun YO, Ryans K, Mu J, Xie Z, Simoneaux T, Blas-Machado U, Eko FO, Black CM, Igietseme JU, He Q. 2017. The emerging role of ASC in dendritic cell metabolism during Chlamydia infection. PLoS One 12:e0188643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zheng J. 2012. Energy metabolism of cancer: glycolysis versus oxidative phosphorylation (review). Oncol Lett 4:1151–1157. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wei Y, Wang D, Jin F, Bian Z, Li L, Liang H, Li M, Shi L, Pan C, Zhu D, Chen X, Hu G, Liu Y, Zhang CY, Zen K. 2017. Pyruvate kinase type M2 promotes tumour cell exosome release via phosphorylating synaptosome-associated protein 23. Nat Commun 8:14041. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.San-Millán I, Brooks GA. 2017. Reexamining cancer metabolism: lactate production for carcinogenesis could be the purpose and explanation of the Warburg Effect. Carcinogenesis 38:119–133. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgw127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schorey JS, Cheng Y, Singh PP, Smith VL. 2015. Exosomes and other extracellular vesicles in host-pathogen interactions. EMBO Rep 16:24–43. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Husmann M, Beckmann E, Boller K, Kloft N, Tenzer S, Bobkiewicz W, Neukirch C, Bayley H, Bhakdi S. 2009. Elimination of a bacterial pore-forming toxin by sequential endocytosis and exocytosis. FEBS Lett 583:337–344. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abrami L, Brandi L, Moayeri M, Brown MJ, Krantz BA, Leppla SH, van der Goot FG. 2013. Hijacking multivesicular bodies enables long-term and exosome-mediated long-distance action of anthrax toxin. Cell Rep 5:986–996. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shimoda A, Ueda K, Nishiumi S, Murata-Kamiya N, Mukai SA, Sawada S, Azuma T, Hatakeyama M, Akiyoshi K. 2016. Exosomes as nanocarriers for systemic delivery of the Helicobacter pylori virulence factor CagA. Sci Rep 6:18346. doi: 10.1038/srep18346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang C, Robbins PD. 2012. Immunosuppressive exosomes: a new approach for treating arthritis. Int J Rheumatol 2012:573528. doi: 10.1155/2012/573528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gutiérrez-Vázquez C, Villarroya-Beltri C, Mittelbrunn M, Sánchez-Madrid F. 2013. Transfer of extracellular vesicles during immune cell-cell interactions. Immunol Rev 251:125–142. doi: 10.1111/imr.12013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schwab A, Meyering SS, Lepene B, Iordanskiy S, van Hoek ML, Hakami RM, Kashanchi F. 2015. Extracellular vesicles from infected cells: potential for direct pathogenesis. Front Microbiol 6:1132. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Almishri W, Santodomingo-Garzon T, Le T, Stack D, Mody CH, Swain MG. 2016. TNFα augments cytokine-induced NK cell IFN-γ production through TNFR2. J Innate Immun 8:617–629. doi: 10.1159/000448077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Micheau O, Tschopp J. 2003. Induction of TNF receptor I-mediated apoptosis via two sequential signaling complexes. Cell 114:181–190. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00521-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tartaglia LA, Goeddel DV. 1992. Two TNF receptors. Immunol Today 13:151–153. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90116-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tekautz TM, Zhu K, Grenet J, Kaushal D, Kidd VJ, Lahti JM. 2006. Evaluation of IFN-γ effects on apoptosis and gene expression in neuroblastoma-preclinical studies. Biochim Biophys Acta 1763:1000–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cao ZH, Zheng QY, Li GQ, Hu XB, Feng SL, Xu GL, Zhang KQ. 2015. STAT1-mediated down-regulation of Bcl-2 expression is involved in IFN-γ/TNF-α-induced apoptosis in NIT-1 cells. PLoS One 10:e0120921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rajalingam K, Oswald M, Gottschalk K, Rudel T. 2007. Smac/DIABLO is required for effector caspase activation during apoptosis in human cells. Apoptosis 12:1503–1510. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Paland N, Bohme L, Gurumurthy RK, Maurer A, Szczepek AJ, Rudel T. 2008. Reduced display of tumor necrosis factor receptor I at the host cell surface supports infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. J Biol Chem 283:6438–6448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708422200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Beatty WL, Belanger TA, Desai AA, Morrison RP, Byrne GI. 1994. Tryptophan depletion as a mechanism of gamma interferon-mediated chlamydial persistence. Infect Immun 62:3705–3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Byrne GI, Lehmann LK, Landry GJ. 1986. Induction of tryptophan catabolism is the mechanism for gamma-interferon-mediated inhibition of intracellular Chlamydia psittaci replication in T24 cells. Infect Immun 53:347–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shemer Y, Sarov I. 1985. Inhibition of growth of Chlamydia trachomatis by human gamma interferon. Infect Immun 48:592–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leonhardt RM, Lee SJ, Kavathas PB, Cresswell P. 2007. Severe tryptophan starvation blocks onset of conventional persistence and reduces reactivation of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun 75:5105–5117. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00668-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shemer-Avni Y, Wallach D, Sarov I. 1989. Reversion of the antichlamydial effect of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) by tryptophan and antibodies to interferon beta. Infect Immun 57:3484–3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mpiga P, Ravaoarinoro M. 2006. Chlamydia trachomatis persistence: an update. Microbiol Res 161:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nelson DE, Virok DP, Wood H, Roshick C, Johnson RM, Whitmire WM, Crane DD, Steele-Mortimer O, Kari L, McClarty G, Caldwell HD. 2005. Chlamydial IFN-gamma immune evasion is linked to host infection tropism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:10658–10663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504198102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Miyairi I, Tatireddigari VR, Mahdi OS, Rose LA, Belland RJ, Lu L, Williams RW, Byrne GI. 2007. The p47 GTPases Iigp2 and Irgb10 regulate innate immunity and inflammation to murine Chlamydia psittaci infection. J Immunol 179:1814–1824. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ying S, Pettengill M, Latham ER, Walch A, Ojcius DM, Hacker G. 2008. Premature apoptosis of Chlamydia-infected cells disrupts chlamydial development. J Infect Dis 198:1536–1544. doi: 10.1086/592755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fields KA, Heinzen RA, Carabeo R. 2011. The obligate intracellular lifestyle. Front Microbiol 2:99. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fan T, Lu H, Hu H, Shi L, McClarty GA, Nance DM, Greenberg AH, Zhong G. 1998. Inhibition of apoptosis in Chlamydia-infected cells: blockade of mitochondrial cytochrome c release and caspase activation. J Exp Med 187:487–496. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Morel JB, Dangl JL. 1997. The hypersensitive response and the induction of cell death in plants. Cell Death Differ 4:671–683. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Puolakkainen M, Campbell LA, Lin TM, Richards T, Patton DL, Kuo CC. 2003. Cell-to-cell contact of human monocytes with infected arterial smooth-muscle cells enhances growth of Chlamydia pneumoniae. J Infect Dis 187:435–440. doi: 10.1086/368267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Perfettini JL, Darville T, Gachelin G, Souque P, Huerre M, Dautry-Varsat A, Ojcius DM. 2000. Effect of Chlamydia trachomatis infection and subsequent tumor necrosis factor alpha secretion on apoptosis in the murine genital tract. Infect Immun 68:2237–2244. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.2237-2244.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Perfettini JL, Hospital V, Stahl L, Jungas T, Verbeke P, Ojcius DM. 2003. Cell death and inflammation during infection with the obligate intracellular pathogen, Chlamydia. Biochimie 85:763–769. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Darville T, Andrews CW Jr, Rank RG. 2000. Does inhibition of tumor necrosis factor alpha affect chlamydial genital tract infection in mice and guinea pigs? Infect Immun 68:5299–5305. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.9.5299-5305.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Williams DM, Magee DM, Bonewald LF, Smith JG, Bleicker CA, Byrne GI, Schachter J. 1990. A role in vivo for tumor necrosis factor alpha in host defense against Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun 58:1572–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Radomski N, Kägebein D, Liebler-Tenorio E, Karger A, Rufer E, Tews BA, Nagel S, Einenkel R, Muller A, Rebbig A, Knittler MR. 2017. Mito-xenophagic killing of bacteria is coordinated by a metabolic switch in dendritic cells. Sci Rep 7:3923. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04142-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Radomski N, Franzke K, Matthiesen S, Karger A, Knittler MR. 2019. NK cell-mediated processing of Chlamydia psittaci drives potent anti-bacterial Th1 immunity. Sci Rep 9:4799. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41264-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Reinhold P, Ostermann C, Liebler-Tenorio E, Berndt A, Vogel A, Lambertz J, Rothe M, Ruttger A, Schubert E, Sachse K. 2012. A bovine model of respiratory Chlamydia psittaci infection: challenge dose titration. PLoS One 7:e30125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nagaraj N, Wisniewski JR, Geiger T, Cox J, Kircher M, Kelso J, Paabo S, Mann M. 2011. Deep proteome and transcriptome mapping of a human cancer cell line. Mol Syst Biol 7:548. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wiśniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N, Mann M. 2009. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat Methods 6:359–362. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Henning AK, Groschup MH, Mettenleiter TC, Karger A. 2014. Analysis of the bovine plasma proteome by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry. Vet J 199:175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.The_UniProt_Consortium. 2017. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res 45:D158–D169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mi H, Muruganujan A, Ebert D, Huang X, Thomas PD. 2019. PANTHER version 14: more genomes, a new PANTHER GO-slim and improvements in enrichment analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 47:D419–D426. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.