Staphylococcus aureus is a causative agent of chronic biofilm-associated infections that are recalcitrant to resolution by the immune system or antibiotics. To combat these infections, an antistaphylococcal, biofilm-specific quadrivalent vaccine against an osteomyelitis model in rabbits has previously been developed and shown to be effective at eliminating biofilm-embedded bacterial populations. However, the addition of antibiotics was required to eradicate remaining planktonic populations.

KEYWORDS: Staphylococcus aureus, biofilm, animal model, vaccine

ABSTRACT

Staphylococcus aureus is a causative agent of chronic biofilm-associated infections that are recalcitrant to resolution by the immune system or antibiotics. To combat these infections, an antistaphylococcal, biofilm-specific quadrivalent vaccine against an osteomyelitis model in rabbits has previously been developed and shown to be effective at eliminating biofilm-embedded bacterial populations. However, the addition of antibiotics was required to eradicate remaining planktonic populations. In this study, a planktonic upregulated antigen was combined with the quadrivalent vaccine to remove the need for antibiotic therapy. Immunization with this pentavalent vaccine followed by intraperitoneal challenge of BALB/c mice with S. aureus resulted in 16.7% and 91.7% mortality in pentavalent vaccine and control groups, respectively (P < 0.001). Complete bacterial elimination was found in 66.7% of the pentavalent cohort, while only 8.3% of the control animals cleared the infection (P < 0.05). Further protective efficacy was observed in immunized rabbits following intramedullary challenge with S. aureus, where 62.5% of the pentavalent cohort completely cleared the infection, versus none of the control animals (P < 0.05). Passive immunization of BALB/c mice with serum IgG against the vaccine antigens prior to intraperitoneal challenge with S. aureus prevented mortality in 100% of mice and eliminated bacteria in 33.3% of the challenged mice. These results demonstrate that targeting both the planktonic and biofilm stages with the pentavalent vaccine or the IgG elicited by immunization can effectively protect against S. aureus infection.

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus is associated with a wide range of acute and chronic diseases such as bacteremia, sepsis, skin and soft tissue infections, pneumonia, endocarditis, and osteomyelitis and has a high rate of mortality, estimated at 20 to 30% in bacteremia patients (1, 2). The vast diversity in S. aureus-mediated disease is a consequence of the differential expression of >70 virulence factors that initiate colonization and growth, mediate damage to the host, and promote immune avoidance in response to the host environment (2). One effective virulence strategy associated with chronic infection is the ability to grow in a biofilm, in which sessile bacteria encapsulate their expanding population in a protective, extracellular polymeric matrix (2, 3). This biofilm phenotype promotes persistence and complicates the resolution of chronic infections because microbes in the biofilm are tolerant to antimicrobial agents and the host immune response due to reduced metabolic activity and limited penetration (4, 5). Treatment of infection is further complicated by the increased incidence of antibiotic-resistant strains (6, 7). These S. aureus characteristics limit the therapeutic options available to eradicate the infection; therefore, new therapies or vaccines to prevent acute and chronic infections are needed.

Clinical trials have not identified an anti-S. aureus vaccine with the protective efficacy required to gain final approval for human application (8–13). Vaccine studies have primarily focused on preventing acute infections such as bacteremia, sepsis, or pneumonia (8–11). Due to the complex life cycle of an S. aureus infection, many attempts to develop a vaccine that prevents infection have failed (10, 11, 14, 15). Mechanisms contributing to this complexity include the functional redundancy among virulence factors, differential expression of virulence factors during different stages of growth (exponential versus stationary phase) or infection phenotype (planktonic versus biofilm mediated), heterogeneity in protein expression throughout the bacterial biofilm, and the lack of genetic conservation of some virulence factors among different strains (14, 16). These features inhibit the mounting of an effective, protective humoral response against S. aureus when only a single virulence factor is targeted. In addition, S. aureus can evade killing by phagocytic cells to some extent by neutralizing the antimicrobial components present in the phagosome (17). Previous antistaphylococcal vaccine approaches using single antigens have had limited success, so vaccine efforts have now shifted to multicomponent vaccines to target S. aureus (16, 18).

S. aureus biofilms exhibit different protein expression profiles compared to their planktonic counterparts (19–21). Although the bacterial biofilm is recalcitrant to clearance by the host immune response, proteins restricted to the biofilm growth phenotype are recognized by the immune system and elicit a humoral response (22). In an effort to target and eradicate S. aureus throughout all stages of biofilm maturation, Brady et al. created a vaccine that boosts and directs the humoral response against biofilm-specific antigens that have sustained expression throughout infection. Unlike other previous multivalent approaches that selected antigens based on putative surface exposure (16, 20), this vaccine included multiple immunogenic proteins that are upregulated during in vitro and in vivo biofilm growth. New Zealand White rabbits immunized with a quadrivalent vaccine of biofilm-specific antigens (listed in Table 1) had reduced clinical and radiographic signs of osteomyelitis following S. aureus challenge, but a bacterial burden was still observed (23). Those authors hypothesized that planktonic bacteria contributed to persistence since the vaccine specifically targeted the biofilm. In a subsequent study, 87.5% of the immunized rabbits that received antibiotics cleared the infection, which supports the hypothesis that the antibiotic-sensitive planktonic population mediated persistence.

TABLE 1.

Composition and characteristics of the pentavalent vaccine antigens used

| Protein identitya (size [bp]) | GI no. | GenBank accession no. | Identification source(s)b | Structure/function(s) (reference[s]) | Upregulation phenotype | Performed vaccine study(ies) (reference[s]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLUCO (functional subunit of autolysin) (SACOL1062) (1,443) | 57650246 | AAW36526.1 | T and P | Glucosaminidase/hydrolysis of peptidoglycan, cell attachment (45, 46) | Biofilm | In vitro (20, 22), rabbits (23), humoral response in patients with bacteremia (27) |

| SACOL0486 (683) | 57651327 | YP_185376.1 | T | Uncharacterized lipoprotein/unknown | Biofilm | In vitro (20, 22, 47), rabbits (23), humoral response in patients with bacteremia (27) |

| SACOL0037 (519) | 57652407 | YP_184948.1 | T | Conserved hypothetical protein/unknown | Biofilm | In vitro (20, 22), rabbits (23) |

| SACOL0688 lipoprotein (ABC) (860) | 57651472 | YP_185570.1 | T and P | ABC transporter binding protein/putative iron-regulated ABC transporter | Biofilm | In vitro (20, 22), rabbits (23), humoral response in patients with bacteremia (27) |

| SACOL0119 (726) | 57652482 | YP_185023.1 | T | Cell wall anchor domain protein/unknown (46) | Planktonic | In vitro (46) |

Protein identities are standardized to the S. aureus COL genome.

See references 20 and 22. In the proteomic study (P), the immunoreactive proteins were identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) analysis and the Profound search engine (Genomic Solution’s Knexus software). The proteins identified in the transcriptomic study (T) were identified with microarray methods using the S. aureus COL.

In this study, a planktonic S. aureus antigen was incorporated into the biofilm-specific quadrivalent vaccine, eliminating the necessity for antibiotics to eradicate planktonic bacteria. Lipoprotein SACOL0119, which was shown to be upregulated across different phases of planktonic growth (early and late exponential and stationary phases) as determined by the presence of active transcripts (20), was chosen. We evaluated the protective efficacy of our pentavalent vaccine (antigens detailed in Table 1) against S. aureus challenge in a murine peritoneal abscess model, which exhibits both planktonic and biofilm modes of growth, and the rabbit model of osteomyelitis (24, 25).

RESULTS

Active immunization reduces mortality and promotes clearance in an S. aureus intraperitoneal infection model.

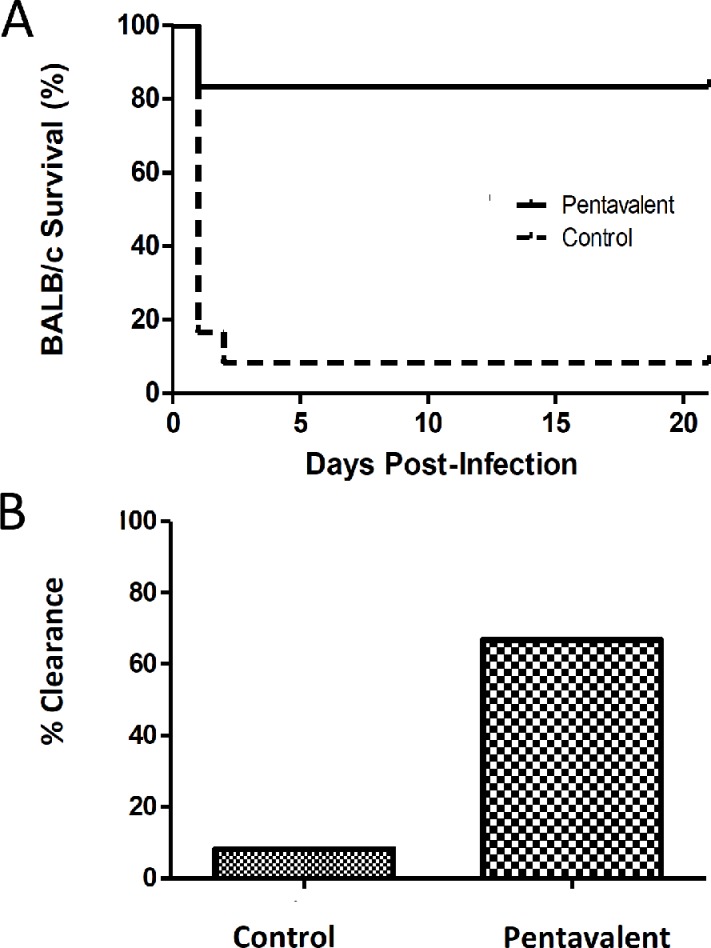

In an effort to target planktonic bacteria without antibiotic therapy, we incorporated the lipoprotein SACOL0119 into our multivalent vaccine. Control mice or BALB/c mice immunized with the pentavalent vaccine were challenged with 3.5 × 108 (±0.5 × 108) CFU of S. aureus via intraperitoneal injection. We observed a significant reduction in the mortality of mice immunized with the pentavalent vaccine versus control cohorts (16.7% versus 91.7%; P < 0.001) (Fig. 1A). Bacterial clearance was a second parameter used to evaluate the protective efficacy of the vaccine. Peritoneal abscesses were recovered from 5 of the 10 surviving immunized mice. We found that 60% of the abscesses were sterile based on the limit of detection for serial plating (Fig. 1B). Overall, we observed complete protection in 66.7% of the mice immunized with the pentavalent vaccine. This trial demonstrated a significant difference in bacterial clearance between mice immunized with the pentavalent vaccine and control cohorts (66.7% versus 8.3%; P < 0.01).

FIG 1.

Survival rates over 21 days (A) and percent bacterial clearance (B) for mice immunized with the pentavalent vaccine (n = 12) and nonimmunized mice (n = 12) after challenge by intraperitoneal injection with a 90% lethal dose (LD90) standard infectious dose (3 × 108 to 4 × 108 CFU) of S. aureus. Survival rates are illustrated with a Kaplan-Meier curve, and statistical significance is calculated by the log rank test between mice immunized with the pentavalent vaccine and nonimmunized mice (survival of 83.3% versus 8.3%; P < 0.001). Bacterial clearance is defined by the absence of S. aureus in the kidneys and peritoneal abscess(es). Animals are considered infected if death occurred prior to the experimental endpoint (day 21). Increased clearance of S. aureus is observed in the pentavalent vaccine cohort (66.7%) compared to the control group (8.3%) (P < 0.01), which is statistically significant by a two-tailed Fisher exact test. CFU in surviving mice could not be statistically compared between vaccinated and control animals since only a single mouse survived in the control infected group.

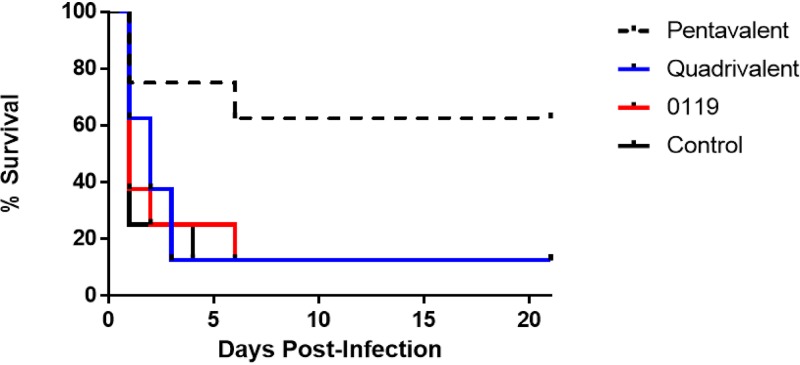

Protective efficacy was also evaluated after challenge with a higher infectious dose of 1.0 × 109 CFU in mice immunized with SACOL0119 alone, a quadrivalent vaccine comprised of biofilm-specific proteins, or a pentavalent vaccine comprised of SACOL0119 and the four biofilm-specific proteins (Fig. 2). Mice immunized with the pentavalent vaccine had a significant reduction in mortality compared to the other immunized cohorts and control mice (37.5% versus 87.5%; P < 0.05). On day 21, surviving animals in both cohorts did not display any signs of morbidity, e.g., ruffled fur or abnormal appearance, and weights had rebounded to preinfection status or above. The surviving animals of each cohort had no bacteria in their kidneys, but discrete bacterium-laden peritoneal abscesses were found in all mice after extensive necropsy and subsequent culture.

FIG 2.

Survival rates over 21 days for mice immunized with the pentavalent vaccine (n = 8), quadrivalent vaccine (n = 8), or SACOL0119 (n = 8) versus nonimmunized mice (n = 8) after challenge by intraperitoneal injection with a high infectious dose (1 × 109 CFU) of S. aureus. Survival rates are illustrated with a Kaplan-Meier curve, and statistical significance is calculated by the log rank test between mice immunized with the pentavalent vaccine and nonimmunized mice (survival of 62.5% versus 12.5%; P < 0.05).

Bacterial persistence following active immunization in mice correlates with reduced antibody titers against SACOL0119.

We tested titers of IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b antibodies generated against the five recombinant antigens in the vaccine. Overall, the mean values for the anti-SACOL0688 IgG subtype titers were significantly higher than those for the anti-SACOL0037 and anti-SACOL0119 IgG subtype titers (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Despite having a small number of mice for statistical evaluation, higher IgG titers against SACOL0119 were observed in the mice that completely cleared the infection than in the two immunized mice that survived but continued to have bacterial burdens (IgG1 with a 1:5,000 dilution; P = 0.003). Antibody titers elicited against the other four antigens (SACOL0037, glucosaminidase, SACOL0486, and SACOL0688) were not significantly different between immunized mice with and those without bacterial burdens (data not shown).

Active immunization promotes clearance in an S. aureus osteomyelitis model.

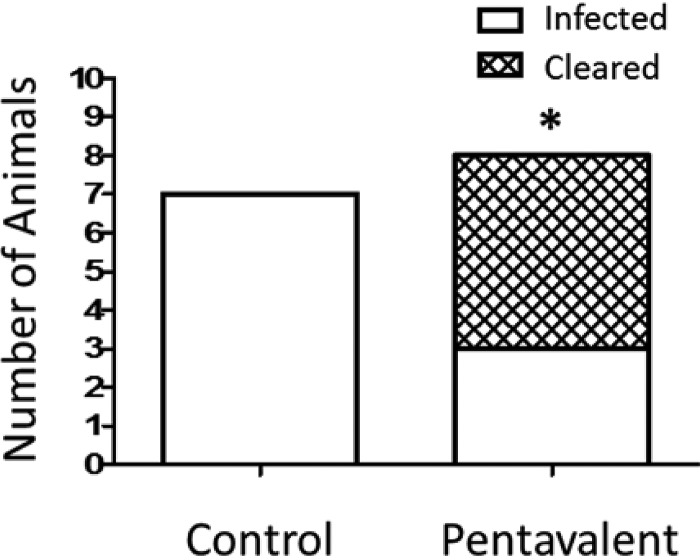

After establishing the protective efficacy of the pentavalent vaccine in mice, we evaluated efficacy in the rabbit model of osteomyelitis. New Zealand White rabbits immunized with the pentavalent vaccine and control rabbits were challenged with 1.3 × 106 CFU of S. aureus. Radiological changes in the infected tibia and bacterial counts were evaluated at 24 days postinfection. We observed bacterial clearance in 62.5% of the immunized rabbits compared to 0% of the control animals (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3). Radiographic scores (ranging from 0 to 4) were assigned to the infected tibias based upon lytic alterations at the injection site and overall disruption of the normal bone architecture. The immunized group had a mean radiographic score of 1.4, versus a score of 3.6 for the control cohort. The majority of immunized rabbits that cleared the infection had lower radiographic scores (range of 0.3 to 1.8) than the three remaining animals with bacterial burdens (range of 1.5 to 3.0) (Table 2).

FIG 3.

Bacterial clearance of rabbits immunized with the pentavalent antigens (n = 8) versus the control (n = 7) after challenge by intramedullary infection with 1.3 × 106 CFU of S. aureus. Bacterial clearance is defined by the absence of S. aureus in the total bone homogenate. Increased clearance of S. aureus is observed in the pentavalent vaccine cohort (62.5%) compared to the control group (0%), which is statistically significant by a two-tailed Fisher exact test (P < 0.05).

TABLE 2.

Radiological and clearance data for pentavalent vaccine

| Treatment group and rabbit | Scorea | CFU/g bone |

|---|---|---|

| Pentavalent | ||

| 1 | 0.3 | 0 |

| 2 | 0.3 | 0 |

| 3 | 0.8 | 0 |

| 4 | 1.3 | 0 |

| 5 | 1.5 | 1.1 × 105 |

| 6 | 1.8 | 0 |

| 7 | 2.5 | 1.1 × 105 |

| 8 | 3.0 | 2.5 × 105 |

| Mock | ||

| 1 | 3.1 | 1.4 × 104 |

| 2 | 3.4 | 2.0 × 104 |

| 3 | 3.5 | 2.5 × 104 |

| 4 | 3.6 | 5.8 × 105 |

| 5 | 3.9 | 1.1 × 105 |

| 6 | 4.0 | 2.0 × 105 |

| 7 | 4.0 | 1.1 × 106 |

Radiological scores (needle site and bone architecture) are as follows: 0 for no lytic changes at the site and normal architecture, 1+ for lytic disruption at the site and <5% architectural disruption, 2+ for 5 to 15% architectural disruption, 3+ for 15 to 40% architectural disruption, and 4+ for >40% architectural disruption. The mean score for the pentavalent group was 1.4, and bacterial clearance was achieved in 5/8 mice. The mean score for the mock group was 3.6, and bacterial clearance was achieved in 0/7 mice.

Passive immunization reduces mortality and promotes clearance in an S. aureus intraperitoneal infection model.

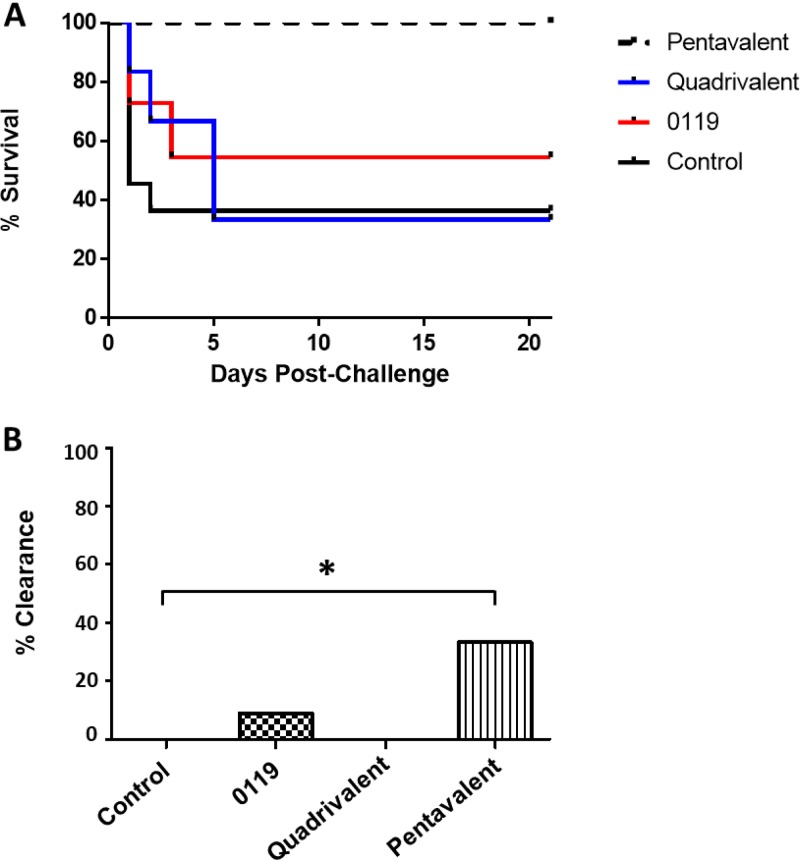

To evaluate whether protective efficacy was mediated by the antibody response elicited against the five antigens and serum IgG would promote bacterial clearance in the absence of T-cell effector activity, we performed a passive immunization study in the murine model of intraperitoneal challenge. BALB/c mice were passively immunized with IgG for SACOL0119, the quadrivalent antigens, or the pentavalent antigens. After 24 h for IgG dispersal, the immunized and control mice were challenged with 5 × 108 to 8 × 108 CFU of S. aureus by intraperitoneal injection, and survival was monitored for 21 days (Fig. 4A). Passive immunization with pooled IgGs targeting the pentavalent antigens significantly reduced mouse mortality compared to the control cohort or mice immunized with IgGs targeting the biofilm antigens alone (0% versus 63.6% or 66.7%, respectively; both P = 0.001). The mortality rate in the mice that received IgG to SACOL0119 alone was 45.5%. Bacterial persistence at day 21 postchallenge was observed in abscesses from 4 control mice (100% of surviving mice), 5 mice immunized with SACOL0119 IgG (83.3% of surviving mice), 2 mice immunized with biofilm-specific IgGs (100% of surviving mice), and 8 mice immunized with both SACOL0119 and biofilm-specific IgGs (66.7% of surviving mice) (Fig. 4B). Bacteria were absent in the kidneys of all surviving immunized animals, while 50% of the surviving control mice had bacteria in the kidneys (data not shown). Overall, we observed complete protection in 33.3% of the mice immunized with IgGs against the pentavalent vaccine antigens.

FIG 4.

Survival rates over 21 days (A) and percent bacterial clearance (B) for mice passively immunized with IgG against the pentavalent antigens (n = 12), quadrivalent antigens (n = 6), or SACOL0119 (n = 11) versus control mice (n = 11) after challenge by intraperitoneal injection with 5 × 108 to 8 × 108 CFU of S. aureus. Survival rates are illustrated with a Kaplan-Meier curve, and statistical significance is calculated by the log rank test between mice immunized with IgG against the pentavalent vaccine and control mice (survival of 100% versus 36.4%; P = 0.001). Bacterial clearance is defined by the absence of S. aureus in the kidneys and peritoneal abscess(es). Animals are considered infected if death occurred prior to the experimental endpoint (day 21). Increased clearance of S. aureus is observed in the pentavalent vaccine cohort (33.3%) compared to the control group (0%), which is statistically significant by a one-tailed Fisher exact test (P < 0.05).

Passive immunization promotes clearance in an S. aureus implant infection model.

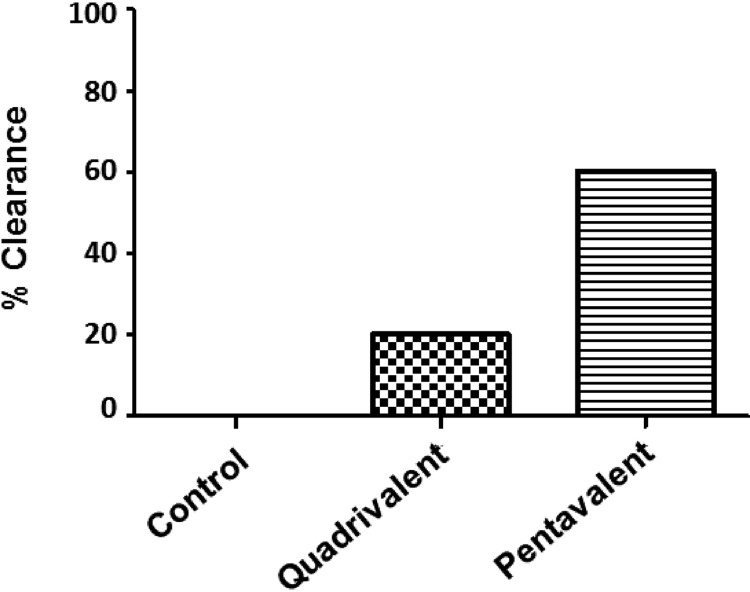

We subsequently tested the protective efficacy of serum IgG in a murine model of implant infection when mice were challenged with 1,000 CFU of S. aureus to increase relevance to clinical human infection. Bacterial persistence was observed at day 21 postchallenge in bone homogenates from 100% of control mice and 80% of mice immunized with sera elicited against the quadrivalent biofilm vaccine. In contrast, bacteria were found in only 40% of mice that received sera elicited against the pentavalent vaccine (Fig. 5). Overall, we observed that serum IgG elicited against the pentavalent vaccine antigen can eradicate bacteria from implants in 60% of immunized animals in the absence of activated T cells.

FIG 5.

Bacterial clearance of mice passively immunized with IgG against the pentavalent antigens (n = 5) or quadrivalent antigens (n = 5) versus control mice (n = 5) after challenge by implant infection with 1,000 CFU of S. aureus. Bacterial clearance is defined by the absence of S. aureus in the total bone homogenate. Increased clearance of S. aureus is observed in the pentavalent vaccine cohort (60%) compared to the control group (0%), which is not statistically significant by the Fisher exact test.

DISCUSSION

S. aureus is a primary etiological agent of nosocomial infections (2), with high rates of associated morbidity and mortality (1). Due to the increased incidence of antibiotic-resistant strains and the limited therapeutics for treating biofilm-associated infections, an effective vaccine against S. aureus will have a large impact on the global human health burden of this pathogen. This study proposes that a multicomponent vaccine developed for acute and chronic biofilm-associated infections will be effective if it takes into account the planktonic and biofilm phenotypes, sustained in vivo expression, and genomic conservation. We incorporated a lipoprotein, SACOL0119, that is upregulated during planktonic growth into a previously formulated and tested quadrivalent antibiofilm vaccine (20, 23). We found that the new pentavalent vaccine reduces mortality in mice and prevents chronic osteomyelitis in rabbits. The multicomponent vaccine eliminated S. aureus in 66.7% of mice after intraperitoneal challenge and in 62.5% of rabbits after intramedullary challenge. Furthermore, we observed that vaccine-elicited IgGs reduce mortality and promote bacterial clearance in abscesses. Antigen-directed IgG also eliminated S. aureus from 60% of tibial implants in mice. Overall, the humoral response elicited by this immunization strategy targets and eradicates S. aureus before a chronic biofilm that is recalcitrant to immune effectors is established.

We found that the highest murine IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b titers, in response to the pentavalent vaccine, were elicited against the ABC transporter SACOL0688. Elevated humoral responses to this antigen have been observed in clinical infections. Dryla et al. observed high levels of anti-SACOL0688 IgG in infected patients (wound infections, bacteremia and sepsis, pneumonia, arthritis, urinary tract infections, catheter-related bloodstream infections, and peritonitis) compared to healthy controls (26). Likewise, den Reijer et al. evaluated the humoral responses against 56 staphylococcal proteins in bacteremia patients and found that SACOL0688 elicited the highest IgG titer (27). Despite the highly immunogenic nature of SACOL0688, we observed modest reductions in S. aureus burdens in rabbits and mice immunized with the quadrivalent antibiofilm vaccine. The disparity between the elevated IgG levels and the limited clearance potential of the anti-SACOL0688 antibodies may be the direct consequence of heterogeneity within the biofilm. Indeed, confocal microscopy of in vitro S. aureus biofilms using anti-SACOL0688 antibodies found that SACOL0688 expression was restricted to distinct pockets of microcolonies within the biofilm (22). These data support the importance of the multivalent vaccine approach to enhance coverage of the biofilm.

In contrast to the elevated anti-SACOL0688 IgG titers, we observed low anti-SACOL0119 IgG titers in mice immunized with the pentavalent vaccine. We propose that SACOL0119 elicits a necessary immune response required for the bacterial clearance observed in 66.7% of mice immunized with the pentavalent vaccine. Despite low titers elicited in response to SACOL0119, the affinity of these antibodies may compensate for reduced titers and sufficiently target the bacteria for destruction by the immune system. Rapid uptake and lagging antibody production may also contribute to the low levels of anti-SACOL0119 IgG observed in the mice since SACOL0119 was the primary target within the planktonic-phase S. aureus inoculum, and the biofilm-specific antigens would be present at low levels. The necessity of targeting the planktonic phenotype was best demonstrated by an immunization study in the rabbit model of osteomyelitis. The humoral response to SACOL0119 targeted planktonic antibiotic-susceptible S. aureus, negating the need for vancomycin therapy (23), and produced sterilizing immunity in a subset of rabbits immunized with the pentavalent vaccine. Despite the recovery of S. aureus from 37.5% of the rabbits immunized with the pentavalent vaccine, we noted reduced radiological signs of disease in these animals. The radiological scores for these rabbits were similar to those for animals that had eliminated the infection. This observation suggests that the vaccine elicits an immune response that inhibits biofilm formation and reduces the severity of osteomyelitis. While the addition of another antigen may be required to enhance coverage and generate complete sterilizing immunity, it is possible that the humoral response elicited by the vaccine was merely overwhelmed by the high bacterial inoculum.

The importance of individual antigens and the protective role of the adaptive immune response following immunization must be analyzed by further immunological studies. Previous research indicates that cell-mediated immunity (Th17 cells) has a more crucial role than previously assumed for protection against S. aureus infections (10, 11, 28–30). Some studies showed that Th17 cells promote protection against infection and mortality, while others found that Th1 cells and Th17 cells mediate inflammatory responses that damage host tissue and create an environment promoting chronic biofilm-associated infections, whereas a Th2-biased humoral response mediates clearance (31–33). The role of Th17 cells and interleukin-17 (IL-17) in infection outcomes may depend on the environment and be infection site specific. The exact role of Th17 cells and IL-17 in the response against S. aureus in mice immunized with the pentavalent vaccine needs to be evaluated.

Our data demonstrate that the consideration of both the biofilm and planktonic phenotypes during antigen selection is an important criterion for vaccine design. While we have demonstrated complete clearance in 66.7% of vaccinated mice and 62.5% of immunized rabbits in this study, we recognize that this interpretation is based on trials in only two animal models. Further studies should evaluate our multicomponent vaccine in other animal models of infection to confirm the efficacy of the five antigens and/or the multicomponent vaccine approach. In other models of disease, alternate antigens may be necessary to elicit protection in different disease states or virulence factors.

An effective passive immunization strategy against S. aureus infection has enormous therapeutic utility in patients undergoing surgery, especially orthopedic and cardiovascular procedures with an implant, and/or after traumatic injury. Surgical site infections (SSIs) represent 20% of hospital-acquired infections, and S. aureus is the major etiological agent (34, 35). In this study, we observed complete protection against mortality due to S. aureus sepsis in mice immunized with IgGs against all five antigens, whereas mice immunized with IgGs against either the four biofilm antigens or SACOL0119 exhibited mortality after intraperitoneal challenge. Death of immunized mice was not observed after day 5 postchallenge. This observation suggests that the immune system elicits an adequate response after day 5 to prevent lethal sepsis, which includes bacterial sequestration in peritoneal abscesses. We found that this passive strategy not only protects mice against lethal sepsis but also eradicates S. aureus in 33.3% of immunized animals in the absence of a memory response. Furthermore, we observed that serum IgG against the five antigens promoted bacterial clearance in 60% of the immunized animals following implant infection. This work strongly suggests that antibody-based therapies are a viable option for the treatment of S. aureus infections, although the incomplete sterilizing immunity suggests that additional or alternate IgGs against S. aureus proteins may be necessary and/or that the concentration of IgGs should be increased.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

CD1/ICR mice (6 to 8 weeks old) were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN). BALB/c and C57BL/6J mice (6 to 8 weeks old) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). New Zealand White rabbits (2 to 2.5 kg) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Mice and rabbits were housed within the animal biosafety level 2 (ABSL2) facility at the University of Maryland—Baltimore. In conducting animal research, the investigators adhered to the laws of the United States and regulations of the Department of Agriculture. Experimental animal studies were performed as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and under the supervision of the Veterinarians and Veterinary Resource Staff at the University of Maryland—Baltimore.

Bacterial strain and growth.

Studies were performed with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) clinical isolate, MRSA-M2, that was obtained from the University of Texas Medical Branch (Galveston, TX). The MRSA-M2 isolate has been used for immunoproteomic and transcriptomic analyses (20, 22, 23, 25, 31, 32, 36–43), and the draft genome was deposited in GenBank under accession number AMTC00000000 (36). The strain was maintained on Trypticase soy agar (TSA) with 5% blood (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and 0.03 mg/ml oxacillin and grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to generate the bacterial inocula.

Purification of recombinant proteins.

Vaccine antigens except SACOL0119 were expressed and purified as described previously by Brady et al. (23). To generate a SACOL0119 expression vector, the MRSA-M2 gene sequence homologous to SACOL0119 was amplified using specific primers, forward primer 5′-CATGCCATGGACACGACTTCAATGAATG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-AGCTTTGTTTAAACTCAATGATGATGATGATGATGAACTTTTTTGTTACTTTGGTTC-3′, and cloned into pBAD-Thio/TOPO. SACOL0119 was expressed from the pBAD-Thio/TOPO vector (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and purified using HisPur Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) resin (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Recombinant SACOL0119 was purified under native conditions using the batch method as instructed by the manufacturer.

Concentration and quantification of recombinant proteins.

Recombinant SACOL0486, glucosaminidase, and SACOL0688 were concentrated and buffer exchanged into phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) using Amicon Ultra 10,000-molecular-weight-cutoff (MWCO) centrifugal units (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) as instructed by the manufacturer. Recombinant SACOL0119 and SACOL0037 were concentrated using trichloroacetic acid precipitation and reconstituted in PBS. Protein quantification was performed using the Advanced protein assay reagent (Cytoskeleton, Inc., Denver, CO) as instructed by the manufacturer. SDS-PAGE was used to verify the purity and concentration of each protein preparation.

Murine active immunization.

BALB/c (intraperitoneal model) and C57BL/6J (transtibial implant infection model) mice were immunized with recombinant antigens. Antigens were combined using 12.5 μg of glucosaminidase, SACOL0486, SACOL0688, and SACOL00037 with or without 25 μg of SACOL0119 per mouse. The mixture was emulsified at a 1:1 ratio with Imject alum (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) for 30 min at room temperature (RT). On day 0, mice were immunized with the pentavalent vaccine or adjuvant alone by intraperitoneal injection. On day 14, mice received the vaccine or PBS without adjuvant. On day 35, BALB/c mice were challenged or C57BL/6J mice were euthanized, and serum was isolated for a study in the implant model.

CD1/ICR mice were also immunized to generate donor serum for passive immunization. Monovalent vaccines of 25 μg SACOL0486, glucosaminidase, SACOL0688, or SACOL0037 were emulsified in Imject alum as described above. Unlike the biofilm monovalent vaccines, the 25 μg SACOL0119 vaccine was emulsified at a 1:1 ratio with TiterMax gold adjuvant (TiterMax USA, Norcross, GA) by brief sonication bursts. On day 0, mice were immunized with the monovalent vaccine or adjuvant alone by intraperitoneal injection. On day 14, mice received the vaccines or PBS without adjuvant. On day 35, mice were euthanized by exsanguination, and serum was isolated.

Rabbit active immunization.

Recombinant proteins were combined at 75 μg of SACOL0688, SACOL0486, glucosaminidase, and SACOL0119 per rabbit. Conforming to previous work, SACOL0037 was resolved by SDS-PAGE, and gel fragments with 75 μg protein were homogenized and then combined with the other proteins. Mixtures were emulsified at a 1:1 ratio with TiterMax gold via sonication. Rabbits were immunized with the pentavalent vaccine or adjuvant alone on day 0 and day 10 via intramuscular injection.

Purification of serum antibodies.

Equivalent volumes of antigen-specific donor sera were combined, and serum IgG was purified using Melon IgG purification resin (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) as instructed by the manufacturer. IgG antibodies were concentrated and buffer exchanged into PBS using Amicon Ultra 10,000-MWCO units. The purified IgG samples represent a 1/4 volume of the initial sample.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were performed to quantify the titers of IgG subclasses elicited against the vaccine components. ELISA plates (MaxiSorp; Thermo Fisher) were coated with 0.5 μg antigen/well and incubated overnight at 4°C. Wells were washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST) and then blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at 37°C. Blocked plates were washed with PBST, and immune or control serum was added, serially diluted, and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Plates were washed with PBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG1 (Invitrogen), IgG2a (Santa Cruz Technology, Dallas, TX), or IgG2b (Invitrogen) diluted 1:1,000 in 1% BSA for 1 h at 37°C. After PBST washes, HRP activity was analyzed by the addition of BD OptEIA TMB substrate (KPL, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) and incubation for 10 min at RT. The colorimetric reaction was halted with 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) stop solution (KPL), and the optical density at 450 nm (OD450) was read on a VersaMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Data were plotted as the OD (y axis) versus the logarithm of the reciprocal serum dilution (x axis).

ELISAs were also performed as described above to quantify the titers of IgG subclasses within purified, concentrated IgG samples (prepared for passive immunization). In the primary binding step, the IgG samples were serially diluted 10-fold from an initial 1:500 dilution. In the secondary step, 0.5 μg/ml of goat HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG1, IgG2a, or IgG2b was used to extrapolate the isotype titers. Titers were approximated based on identifying the dilution value that is >2 standard deviations of the mean value for the control naive serum readings.

Passive immunization for the intraperitoneal abscess model.

This study evaluated the protective efficacy of three experimental immunizations: (i) a pentavalent vaccine composed of anti-SACOL0486, anti-SACOL0688, anti-glucosaminidase, anti-SACOL0037, and anti-SACOL0019 purified IgG samples at a 1:1:2:2:2 ratio; (ii) a quadrivalent vaccine composed of anti-SACOL0486, anti-SACOL0688, antiglucosaminidase, and anti-SACOL0037 purified IgG samples at a 1:1:2:2 ratio; and (iii) a planktonic immunization composed of anti-SACOL0119 purified IgG in a volume equivalent to those of other immunizations. Ratio values were based upon titer values obtained from the ELISAs. Immunizations were prepared using either 40 μl or 80 μl of each purified, concentrated IgG sample. BALB/c mice were anesthetized by inhalation of 3 to 4% isoflurane. Passive immunization was performed by retro-orbital injection.

Passive immunization for the murine transtibial implant model.

This study evaluated the protective efficacy of total serum from donor C57BL/6J mice immunized with either the pentavalent vaccine or the quadrivalent antibiofilm vaccine. C57BL/6J mice were anesthetized by inhalation of 3 to 4% isoflurane. Passive immunization was performed by intravenous tail vein injection with 150 μl of donor serum.

Intraperitoneal challenge for the murine abscess model.

For the active immunization studies, BALB/c mice were challenged via intraperitoneal injection with 3.5 × 108 (±0.5 × 108) CFU (low infectious dose) or 1 × 109 CFU (high infectious dose) of MRSA-M2 3 weeks after the booster. In contrast, mice were challenged via intraperitoneal injection with 5 × 108 to 8 × 108 CFU of MRSA-M2 24 h after passive immunization. The S. aureus inoculum was prepared 3.25 ± 0.25 h after inoculating TSB from a culture grown overnight. The subculture concentration was predicted by an optical density measurement (OD600) that correlated with a known concentration from preliminary growth studies. Concentrations were confirmed by enumeration following serial dilution agar plating. After challenge, mice were monitored for signs of morbidity for 21 days. Mice with a weight loss of >15% of their prechallenge body weight were considered in advanced stages of morbidity and humanely euthanized, as death was an unequivocal outcome. At 3 weeks postchallenge, surviving animals were euthanized by exsanguination to collect blood. Kidneys and spleen were harvested, and abscesses in the peritoneal cavity were removed. The kidneys, spleens, and abscesses were homogenized, and serial dilution agar plating was performed on TSA and an S. aureus-selective medium, CHROMagar (CHROMagar, Paris, France). Bacterial counts were enumerated from the CHROMagar plates and are reported as CFU per organ or abscess, with a limit of detection of 100 CFU. CFU enumerated from TSA were compared to the CFU on CHROMagar and used to identify secondary infections in the mice.

Rabbit osteomyelitis infection model.

Rabbits were challenged on day 30 (20 days after the booster) by intratibial injection of 1.3 × 106 CFU of MRSA-M2 as detailed previously by Mader and Shirtliff (25). At 24 days postinfection, rabbits were anesthetized, and radiographs of the infected and uninfected tibias were obtained. The severity of osteomyelitis was based upon lytic changes at the injection site and the extent of bone architecture disruption. Radiographs were scored as follows: 0 indicated no lytic changes at the injection site and normal architecture, 1+ was reported for lytic changes around the injection site and a <5% disruption of normal bone architecture, 2+ was reported for a 5 to 15% disruption of normal bone architecture, 3+ was reported for a 15 to 40% disruption of normal bone architecture, and 4+ was reported for a >40% disruption of normal bone architecture. Scoring was independently performed by four individuals, who were blind to infection status, and reported as a mean value. An individual could assign values between the “scores.” After imaging, animals were euthanized, and infected tibias were removed and processed as described previously (23). Tenfold serial dilutions of tibial samples were prepared and plated on CHROMagar with a limit of detection of 100 CFU. Tibial samples of 100-μl aliquots were also plated on CHROMagar and TSA, with a limit of detection of 10 CFU. Bacterial counts were calculated and are reported as CFU per gram of bone.

Murine transtibial implant infection model.

Twenty-four hours after passive immunization, C57BL/6J mice were challenged with 1 × 103 CFU of MRSA-M2 deposited onto an implanted pin. Preparation and confirmation of the S. aureus inoculum were performed in a manner to that for the peritoneal challenge. C57BL/6J mice received general anesthesia, and a sterile stainless steel insect pin (Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA) was surgically implanted through the tibia as detailed previously by Prabhakara et al. and Li et al. (32, 44). In this study, 1 μl of the inoculum was pipetted onto the exposed ends of the pin. Mice were monitored for signs of morbidity for 21 days after implant infection. At 3 weeks postchallenge, the mice were euthanized by exsanguination to collect blood, and the tibiae were harvested. The tibiae were homogenized, and serial dilution agar plating was performed as described above for the murine abscess model.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Categorical data were tested for differences using Fisher’s exact test or the chi-square test, as appropriate, whereas continuous variables were tested using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Two-tailed P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, grant (R01 AI69568) and by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs through the Peer Reviewed Orthopaedic Research Program (award number W81XWH-15-1-0629). The U.S. Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity, Fort Detrick, MD, is the awarding and administering acquisition office. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense. Fellowship grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation for Grants in Biology and Medicine (PBZHP3_141483 and P3MP3_148362/1) supported Y.A.

During preparation of the manuscript, Mark E. Shirtliff passed away in a tragic accident and did not read the final version. We thank him for his ideas and support in this project.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Laupland KB, Ross T, Gregson DB. 2008. Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections: risk factors, outcomes, and the influence of methicillin resistance in Calgary, Canada, 2000–2006. J Infect Dis 198:336–343. doi: 10.1086/589717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowy FD. 1998. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med 339:520–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Archer NK, Mazaitis MJ, Costerton JW, Leid JG, Powers ME, Shirtliff ME. 2011. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms: properties, regulation, and roles in human. Virulence 2:445–459. doi: 10.4161/viru.2.5.17724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoiby N, Ciofu O, Johansen HK, Song ZJ, Moser C, Jensen PO, Molin S, Givskov M, Tolker-Nielsen T, Bjarnsholt T. 2011. The clinical impact of bacterial biofilms. Int J Oral Sci 3:55–65. doi: 10.4248/IJOS11026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ceri H, Olson ME, Stremick C, Read RR, Morck D, Buret A. 1999. The Calgary biofilm device: new technology for rapid determination of antibiotic susceptibilities of bacterial biofilms. J Clin Microbiol 37:1771–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kronvall G. 2010. Antimicrobial resistance 1979-2009 at Karolinska hospital, Sweden: normalized resistance interpretation during a 30-year follow-up on Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli resistance development. APMIS 118:621–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2010.02660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seal JB, Moreira B, Bethel CD, Daum RS. 2003. Antimicrobial resistance in Staphylococcus aureus at the University of Chicago Hospitals: a 15-year longitudinal assessment in a large university-based hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 24:403–408. doi: 10.1086/502222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jansen KU, Girgenti DQ, Scully IL, Anderson AS. 2013. Vaccine review: “Staphylococcus aureus vaccines: problems and prospects.” Vaccine 31:2723–2730. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harro JM, Peters BM, O’May GA, Archer N, Kerns P, Prabhakara R, Shirtliff ME. 2010. Vaccine development in Staphylococcus aureus: taking the biofilm phenotype into consideration. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 59:306–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spellberg B, Daum R. 2012. Development of a vaccine against Staphylococcus aureus. Semin Immunopathol 34:335–348. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0293-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Proctor RA. 2012. Challenges for a universal Staphylococcus aureus vaccine. Clin Infect Dis 54:1179–1186. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frenck RW Jr, Creech CB, Sheldon EA, Seiden DJ, Kankam MK, Baber J, Zito E, Hubler R, Eiden J, Severs JM, Sebastian S, Nanra J, Jansen KU, Gruber WC, Anderson AS, Girgenti D. 2017. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of a 4-antigen Staphylococcus aureus vaccine (SA4Ag): results from a first-in-human randomised, placebo-controlled phase 1/2 study. Vaccine 35:375–384. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue M, Yonemura T, Baber J, Shoji Y, Aizawa M, Cooper D, Eiden J, Gruber WC, Jansen KU, Anderson AS, Gurtman A. 2018. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of a novel 4-antigen Staphylococcus aureus vaccine (SA4Ag) in healthy Japanese adults. Hum Vaccin Immunother 14:2682–2691. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1496764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otto M. 2010. Novel targeted immunotherapy approaches for staphylococcal infection. Expert Opin Biol Ther 10:1049–1059. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2010.495115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daum RS, Spellberg B. 2012. Progress toward a Staphylococcus aureus vaccine. Clin Infect Dis 54:560–567. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stranger-Jones YK, Bae T, Schneewind O. 2006. Vaccine assembly from surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:16942–16947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606863103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeLeo FR, Diep BA, Otto M. 2009. Host defense and pathogenesis in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am 23:17–34. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fowler VG Jr, Proctor RA. 2014. Where does a Staphylococcus aureus vaccine stand? Clin Microbiol Infect 20(Suppl 5):66–75. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beenken KE, Dunman PM, McAleese F, Macapagal D, Murphy E, Projan SJ, Blevins JS, Smeltzer MS. 2004. Global gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. J Bacteriol 186:4665–4684. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.14.4665-4684.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brady RA, Leid JG, Camper AK, Costerton JW, Shirtliff ME. 2006. Identification of Staphylococcus aureus proteins recognized by the antibody-mediated immune response to a biofilm infection. Infect Immun 74:3415–3426. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00392-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Resch A, Leicht S, Saric M, Pasztor L, Jakob A, Gotz F, Nordheim A. 2006. Comparative proteome analysis of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm and planktonic cells and correlation with transcriptome profiling. Proteomics 6:1867–1877. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brady RA, Leid JG, Kofonow J, Costerton JW, Shirtliff ME. 2007. Immunoglobulins to surface-associated biofilm immunogens provide a novel means of visualization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:6612–6619. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00855-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brady RA, O’May GA, Leid JG, Prior ML, Costerton JW, Shirtliff ME. 2011. Resolution of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm infection using vaccination and antibiotic treatment. Infect Immun 79:1797–1803. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00451-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frimodt-Moller N, Knudsen JD, Espersen F. 1999. The mouse peritonitis/sepsis model, p 127–136. In Zak O, Sande MA (ed), Handbook of animal models of infection. Academic Press Ltd, London, England. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mader JT, Shirtliff ME. 1999. The rabbit model of bacterial osteomyelitis of the tibia, p 581–591. In Zak O, Sande MA (ed), Handbook of animal models of infection. Academic Press Ltd, London, England. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dryla A, Prustomersky S, Gelbmann D, Hanner M, Bettinger E, Kocsis B, Kustos T, Henics T, Meinke A, Nagy E. 2005. Comparison of antibody repertoires against Staphylococcus aureus in healthy individuals and in acutely infected patients. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 12:387–398. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.3.387-398.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.den Reijer PM, Lemmens-den Toom N, Kant S, Snijders SV, Boelens H, Tavakol M, Verkaik NJ, van Belkum A, Verbrugh HA, van Wamel WJ. 2013. Characterization of the humoral immune response during Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and global gene expression by Staphylococcus aureus in human blood. PLoS One 8:e53391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin L, Ibrahim AS, Xu X, Farber JM, Avanesian V, Baquir B, Fu Y, French SW, Edwards JE Jr, Spellberg B. 2009. Th1-Th17 cells mediate protective adaptive immunity against Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans infection in mice. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000703. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Archer NK, Adappa ND, Palmer JN, Cohen NA, Harro JM, Lee SK, Miller LS, Shirtliff ME. 2016. Interleukin-17A (IL-17A) and IL-17F are critical for antimicrobial peptide production and clearance of Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization. Infect Immun 84:3575–3583. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00596-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Archer NK, Harro JM, Shirtliff ME. 2013. Clearance of Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage is T cell dependent and mediated through interleukin-17A expression and neutrophil influx. Infect Immun 81:2070–2075. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00084-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prabhakara R, Harro JM, Leid JG, Keegan AD, Prior ML, Shirtliff ME. 2011. Suppression of the inflammatory immune response prevents the development of chronic biofilm infection due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun 79:5010–5018. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05571-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prabhakara R, Harro JM, Leid JG, Harris M, Shirtliff ME. 2011. Murine immune response to a chronic Staphylococcus aureus biofilm infection. Infect Immun 79:1789–1796. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01386-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heim CE, Vidlak D, Scherr TD, Hartman CW, Garvin KL, Kielian T. 2015. IL-12 promotes myeloid-derived suppressor cell recruitment and bacterial persistence during Staphylococcus aureus orthopedic implant infection. J Immunol 194:3861–3872. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Richards CL Jr, Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Pollock DA, Cardo DM. 2007. Estimating health care-associated infections and deaths in U.S. hospitals, 2002. Public Health Rep 122:160–166. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. 1999. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 20:250–278. doi: 10.1086/501620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harro JM, Daugherty S, Bruno VM, Jabra-Rizk MA, Rasko DA, Shirtliff ME. 2013. Draft genome sequence of the methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolate MRSA-M2. Genome Announc 1:e00037-12. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00037-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jabra-Rizk MA, Meiller TF, James CE, Shirtliff ME. 2006. Effect of farnesol on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation and antimicrobial susceptibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:1463–1469. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1463-1469.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leid JG, Shirtliff ME, Costerton JW, Stoodley P. 2002. Human leukocytes adhere to, penetrate, and respond to Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Infect Immun 70:6339–6345. doi: 10.1128/iai.70.11.6339-6345.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peters BM, Jabra-Rizk MA, Scheper MA, Leid JG, Costerton JW, Shirtliff ME. 2010. Microbial interactions and differential protein expression in Staphylococcus aureus-Candida albicans dual-species biofilms. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 59:493–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00710.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peters BM, Ovchinnikova ES, Krom BP, Schlecht LM, Zhou H, Hoyer LL, Busscher HJ, van der Mei HC, Jabra-Rizk MA, Shirtliff ME. 2012. Staphylococcus aureus adherence to Candida albicans hyphae is mediated by the hyphal adhesin Als3p. Microbiology 158:2975–2986. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.062109-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schlecht LM, Peters BM, Krom BP, Freiberg JA, Hansch GM, Filler SG, Jabra-Rizk MA, Shirtliff ME. 2015. Systemic Staphylococcus aureus infection mediated by Candida albicans hyphal invasion of mucosal tissue. Microbiology 161:168–181. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.083485-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shirtliff M, Harro J, Leid J. February 2016. Multivalent vaccine protection from Staphylococcus aureus infection. US patent 9,265,820.

- 43.Shirtliff ME, Calhoun JH, Mader JT. 2002. Experimental osteomyelitis treatment with antibiotic-impregnated hydroxyapatite. Clin Orthop Relat Res 401:239–247. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200208000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li D, Gromov K, Søballe K, Puzas JE, O’Keefe RJ, Awad H, Drissi H, Schwarz EM. 2008. Quantitative mouse model of implant-associated osteomyelitis and the kinetics of microbial growth, osteolysis, and humoral immunity. J Orthop Res 26:96–105. doi: 10.1002/jor.20452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Houston P, Rowe SE, Pozzi C, Waters EM, O’Gara JP. 2011. Essential role for the major autolysin in the fibronectin-binding protein-mediated Staphylococcus aureus biofilm phenotype. Infect Immun 79:1153–1165. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00364-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gill SR, Fouts DE, Archer GL, Mongodin EF, Deboy RT, Ravel J, Paulsen IT, Kolonay JF, Brinkac L, Beanan M, Dodson RJ, Daugherty SC, Madupu R, Angiuoli SV, Durkin AS, Haft DH, Vamathevan J, Khouri H, Utterback T, Lee C, Dimitrov G, Jiang L, Qin H, Weidman J, Tran K, Kang K, Hance IR, Nelson KE, Fraser CM. 2005. Insights on evolution of virulence and resistance from the complete genome analysis of an early methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain and a biofilm-producing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis strain. J Bacteriol 187:2426–2438. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.7.2426-2438.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vytvytska O, Nagy E, Bluggel M, Meyer HE, Kurzbauer R, Huber LA, Klade CS. 2002. Identification of vaccine candidate antigens of Staphylococcus aureus by serological proteome analysis. Proteomics 2:580–590. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.