Short abstract

Background

There is limited information about non-selective and contemporary data on quality of stroke care and its variation among hospitals at a national level.

Patients and methods

We analysed data of the patients admitted to 258 acute stroke care hospitals covering the entire country from the Acute Stroke Quality Assessment Program, which was performed by the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service from 2008 to 2014 in South Korea. The primary outcome measure was defect-free stroke care (all-or-none), based on six get with the guidelines-stroke performance measures (except venous thromboembolism prophylaxis).

Results

Among 43,793 acute stroke patients (mean age, 67 ± 14 years; male, 55%), 31,915 (72.9%) were hospitalised due to ischaemic stroke. At a patient level, defect-free stroke care steadily increased throughout the study period (2008, 80.2% vs. 2014, 92.1%), but there were large disparities among hospitals (mean = 50.7%, SD = 21.7%). Defect-free stroke care was given more frequently in patients being treated in hospitals with 25 or more stroke cases per month (odds ratio [OR] 2.83; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.69–4.72), delivery of intravenous thrombolysis one or more times per month (OR 2.37; 95% CI 1.44–3.92), or provision of stroke unit care (OR 1.75; 95% CI 1.22–2.52).

Discussion

This study shows that the quality of stroke care in Korea is improving over time and is higher in centres with a larger volume of stroke or intravenous thrombolysis cases and providing stroke unit care but hospital disparities exist.

Conclusion

Reducing large differences in defect-free stroke care among acute stroke care hospitals should be continuously pursued.

Keywords: Stroke, quality assessment, stroke care, quality of care

Introduction

The quality of stroke care is associated with better survival and quality of life after stroke.1,2 Several studies from the get with the guidelines (GWTG)-stroke database2,3 and other national stroke registries1,4–6 have shown that participation in these nationwide quality assurance programs may lead to high-quality stroke care and better clinical outcomes in association with adherence to clinical stroke guidelines.

However, previous studies are limited in the following ways: (1) because participation in such programs may be voluntary and limited by selection bias favouring participating hospitals having a greater interest in improving quality of stroke care,1,3,7–9 study subjects may not be representative of the population at large,1,7,9,10 and (2) comparisons of quality care across countries are difficult due to heterogeneity in study methodology and quality indicators.8 To the best of our knowledge, there has been no peer-reviewed article providing the summary measure for quality of stroke care based on a nationwide sample of non-selected stroke patients and reporting global quality measures at both the patient and hospital levels.

The acute stroke quality assessment program (ASQAP) is an external audit to assess the quality of acute stroke care in Korean hospitals carried out by the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA). Using data from the ASQAP in Korea, we aimed to describe (1) the contemporary quality of stroke care, (2) secular trends of performance measures based on current stroke guidelines,11,12 (3) disparities in stroke care among hospitals, and (4) differences in performance measures among Korea, the United States (US), and Taiwan.

Materials and methods

The acute stroke quality assessment program

The ASQAP is a nationwide survey of acute care hospitals is conducted by the HIRA under the supervision of the Ministry of Health and Welfare to assess quality of acute stroke care in Korea. Its goals are to (1) improve the quality of acute stroke care for hospitalised stroke patients, (2) recognise and evaluate disparities in stroke care services among acute care hospitals, and (3) reduce the national cost burden for stroke care.13 After the first assessment in 2005, the HIRA repeated stroke quality assessments in 2008, 2010, 2011, 2013, 2014, and 2017, with each assessment period lasting three months (Supplemental Figure). For the purpose of improving care quality of each hospital, the Value Incentive Program was introduced in 2011.13 To be qualified for an each assessment, hospitals had to treat 10 or more acute stroke patients during a period of three consecutive months. The definitions of the quality indicators for stroke care have been changed during the seven assessment epochs as stroke guidelines have been amended (Supplemental Figure). During this process, corresponding hospitals were obliged to submit the data to the HIRA, and some cases were sampled to confirm the accuracy and authenticity of the submitted data by an external audit.

All of the population in South Korea is eligible for coverage under the National Health Insurance (NHI) program, a social insurance benefit system, and thus, all reimbursement claims for health services issued by healthcare providers in Korea are collected and assessed by the HIRA. Since the National Health Insurance system is mandatory for all Korean citizens, the healthcare providers cannot deny NHI patients, and admission to hospital for acute disease care is rarely affected by systemic or economic reasons. Thus, we were able to collect data of almost all patients with acute stroke who were admitted to hospitals during the assessment periods.

Study design and participants

This retrospective analysis was performed using the ASQAP database as part of the Joint Project on Quality Assessment Research by HIRA.13 We included all individuals who were admitted to the emergency department in a Korean hospital within seven days of onset for acute stroke care, were assessed under the ASQAP between 2008 and 2014 (data from the 2005 and 2017 assessments were not available), and met one of the following International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) discharge codes: I60 (subarachnoid haemorrhage), I61 (intracerebral haemorrhage), I62 (other non-traumatic intracranial haemorrhage), or I63 (cerebral infarction).

Ethics statement

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the HIRA. The need for obtaining written informed consent from the study subjects was waived as the study subjects were de-identified in the database.

Data collection

Patient level data were obtained including age, sex, discharge diagnosis according to the ICD-10 codes, use of an ambulance, last known time as being well, first time any neurological abnormality was noted, arrival time, stroke severity scale (the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] or the Glasgow Coma Scale) scores, type of first neuroimaging modality, intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (IV tPA) administration time (if administered), length of hospital stay, mortality (in-hospital, at three months, and at year year), dysphagia screening test results, and consideration for rehabilitation therapy. Hospital level data included hospital location, number of hospital beds, number of stroke cases per month, number of IV tPA administration per month, and presence or absence of a stroke unit certified by the Korean Stroke Society. The claims data were matched to the ASQAP database to obtain supplementary data for the study.

Performance measures for stroke care

The six GWTG-stroke performance measures14 were used as core measures to assess the quality of acute stroke care in this study. Five individual performance measures including IV tPA 2 h (3.5 h), early antithrombotics, discharge antithrombotics, anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation, and lipid-lowering drug at discharge were obtained from patients with ischaemic stroke, while smoking cessation was collected from all stroke patients.9,14 Definitions of individual performance measures were adapted for comparisons between the ASQAP and the GWTG, and detailed description of denominators and numerators for individual performance measures is presented in the Supplemental Table I. Regarding lipid management, the ASQAP only evaluated whether or not lipid testing was performed during hospitalisation or within 30 days prior to the index stroke. Because information on lipid levels was not available, the definition of lipid-lowering drug at discharge was modified from the original definition of the GWTG-Stroke to a proportion of patients to whom lipid-lowering medication was prescribed at discharge among all the patients whose discharge diagnosis was ischaemic stroke. Deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis was excluded because this measure was not assessed in the ASQAP mainly due to a low incidence of deep vein thrombosis in Asian populations.15 Detailed descriptions of the additional performance measures including door-to-needle time, dysphagia screening, and assessed for rehabilitation are presented in the Supplemental Methods.

We defined three different summary measures as outcome variables which were obtained to summarise overall stroke-care quality.14 A defect-free stroke care (all-or-none) measure was defined as a proportion of patients who were perfect for all the corresponding performance measures among all the eligible patients. A patient average measure was obtained by calculating a proportion of measures that were successfully met among all the applicable measures in each patient and averaging these proportions across all the eligible patients. Lastly, an overall percentage measure was obtained by collecting all the applicable measures from all the eligible patients and calculating a proportion of measures that were met over those measures overall. Since the information regarding the prescription of lipid-lowering agents at discharge based on the matched claims data was only available in the 2013 and 2014 assessments, the summary measures were obtained in two different ways: those excluding lipid-lowering drugs at discharge, and those including lipid-lowering drugs at discharge. The former, based on the 5 core performance measures, was used for secular trends and the latter, based on the 6 core measures, was used for examining hospital disparities and international comparisons.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of patients and hospitals enrolled in this study were presented as a frequency (percentage) for categorical variables and as a mean±SD or a median with an interquartile range for continuous variables. Cochran–Armitage trend tests, or beta-logistic models were used to assess secular trends of hospital characteristics and individual and summary performance measures, when appropriate. The relationships between hospital characteristics of the admitted patients and the level of stroke care quality of patients received were further examined with multilevel models. Variables used for adjustment included age, sex, history of atrial fibrillation, current smoking, NIHSS score, and time from onset to arrival. To account for the correlations between the outcomes of patients being treated within the same hospital, we applied a generalised linear mixed model with a binomial distribution using a logarithmic link function. For a comparison of the performance measures among countries,16,17 individual and summary measures were adapted and re-defined in patients who had the ICD-10 code I63 for their final diagnosis. To obtain overall rates of the US, we calculated the weighted average based on the reported rates of primary stroke centres and comprehensive stroke centres participating in the GWTG-Stroke program.17 Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 6.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Patient characteristics

From the ASQAP database, 43,793 acute stroke patients (mean age, 67 ± 14 years; male, 55%) treated in 258 hospitals were evaluated in five (2nd–6th) consecutive assessments and included in the study. Ischaemic stroke cases accounted for 73% (n = 31,915). Half of the patients arrived at hospitals via ambulance, and the median NIHSS score was 4. Sixteen per cent of the patients had atrial fibrillation or flutter, and 36% were ever smokers (Supplemental Table II).

Hospital characteristics

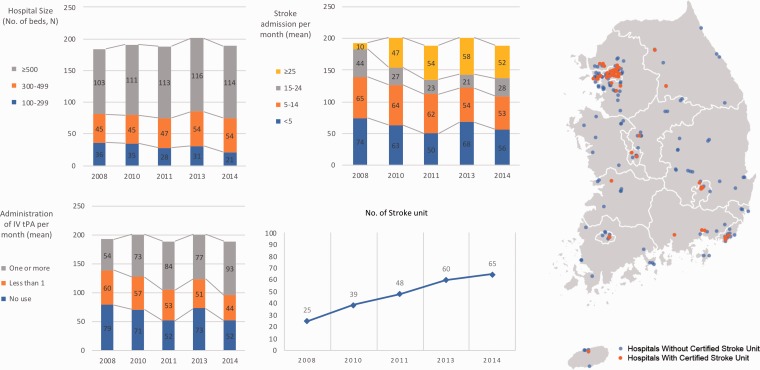

Of the 258 hospitals, 137 hospitals (53.1%) were evaluated in all the 5 assessments, 32 (12.4%) in 4 assessments, 24 (9.3%) in 3 and 65 (25.2%) in 1 or 2. The median number of beds in the 258 hospitals was 548, and more than half had 500 or more beds. One-third provided acute stroke care services to less than five cases per month, and about 60% of the hospitals had less than one IV tPA case per month. Mean stroke admissions and IV tPA cases per month for each hospital were 12.2 and 0.8, respectively. The distribution of acute care hospitals was even throughout country, but the distribution of hospitals with certified stroke units showed an urban-to-rural gradient (Figure 1). There was an increase of hospitals providing stroke unit care over time from 13% to 34%.

Figure 1.

Hospital characteristics and distribution of certified stroke units in Korea.

Contemporary status of stroke care quality in Korea

Overall, most of the summary and core performance measures were achieved in about 90% of the patients (Table 1). Among the patients arriving within 3 h from symptom onset, 68% underwent neuroimaging within 25 min of hospital arrival. Door-to-needle time within 60 and 45 minutes was achieved in 79% and 61%, respectively (Supplemental Table III).

Table 1.

Current status and secular trends of quality of stroke care in Korea.

| Overall | 2008 | 2010 | 2011 | 2013 | 2014 | P-for-trend* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary measuresa | |||||||

| Defect-free stroke care (all-or-none) | 88.8 | 80.2 | 85.0 | 88.9 | 92.4 | 92.1 | <0.01 |

| Patient average | 94.7 | 90.3 | 92.7 | 94.9 | 96.6 | 96.4 | <0.01 |

| Overall percentage | 94.8 | 89.8 | 92.6 | 95.0 | 96.7 | 96.6 | <0.01 |

| Core performance measures | |||||||

| Acute | |||||||

| IV tPA 2 h (3.5 h) | 84.6 | 64.0 | 75.9 | 85.5 | 91.9 | 96.5 | <0.01 |

| Early antithrombotics | 99.3 | 96.3 | 99.4 | 99.8 | 99.97 | 99.95 | <0.01 |

| Discharge | |||||||

| Discharge Antithrombotics | 90.0 | 86.5 | 87.0 | 89.3 | 92.5 | 92.1 | <0.01 |

| Anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation | 96.6 | 86.7 | 94.3 | 98.1 | 99.2 | 98.6 | <0.01 |

| Smoking cessation | 99.5 | NA | NA | 99.1 | 99.7 | 99.6 | 0.33 |

| Lipid-lowering drugs at discharge | NA | NA | NA | NA | 71.8 | 77.2 | <0.01 |

IV tPA: intravenous tissue-plasminogen activator; NA: not assessed.

*P-values for secular trends of performance measures using Cochran–Armitage trend tests, or beta-logistic models as appropriate.

aSummary measures for evaluating secular trends in this table were based on five core performance measures without lipid-lowering drugs at discharge.

Secular trends in quality of stroke care

Over seven years (2008–2014), the achievement of summary measures based on five core measures increased by 12% for defect-free stroke care (all-or-none), 6% for patient average, and 7% for overall percentage (Table 1). All individual performance measures including additional measures demonstrated a steady increment from 2008 to 2014 (P-for-trend for all core performance measures except intervention for smoking cessation <0.01). Intervention for smoking cessation during hospitalisation was performed in most of the eligible patients in all assessment periods (99.1% in 2011, 99.7% in 2013, and 99.6% in 2014, P-for-trend = 0.33). Lipid-lowering drug at discharge showed a 5.4% increment from 2013 to 2014 (p < 0.01).

Hospital disparities in quality of stroke care

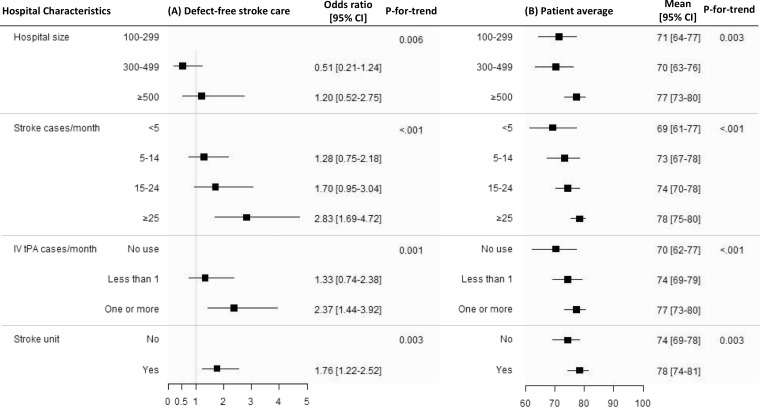

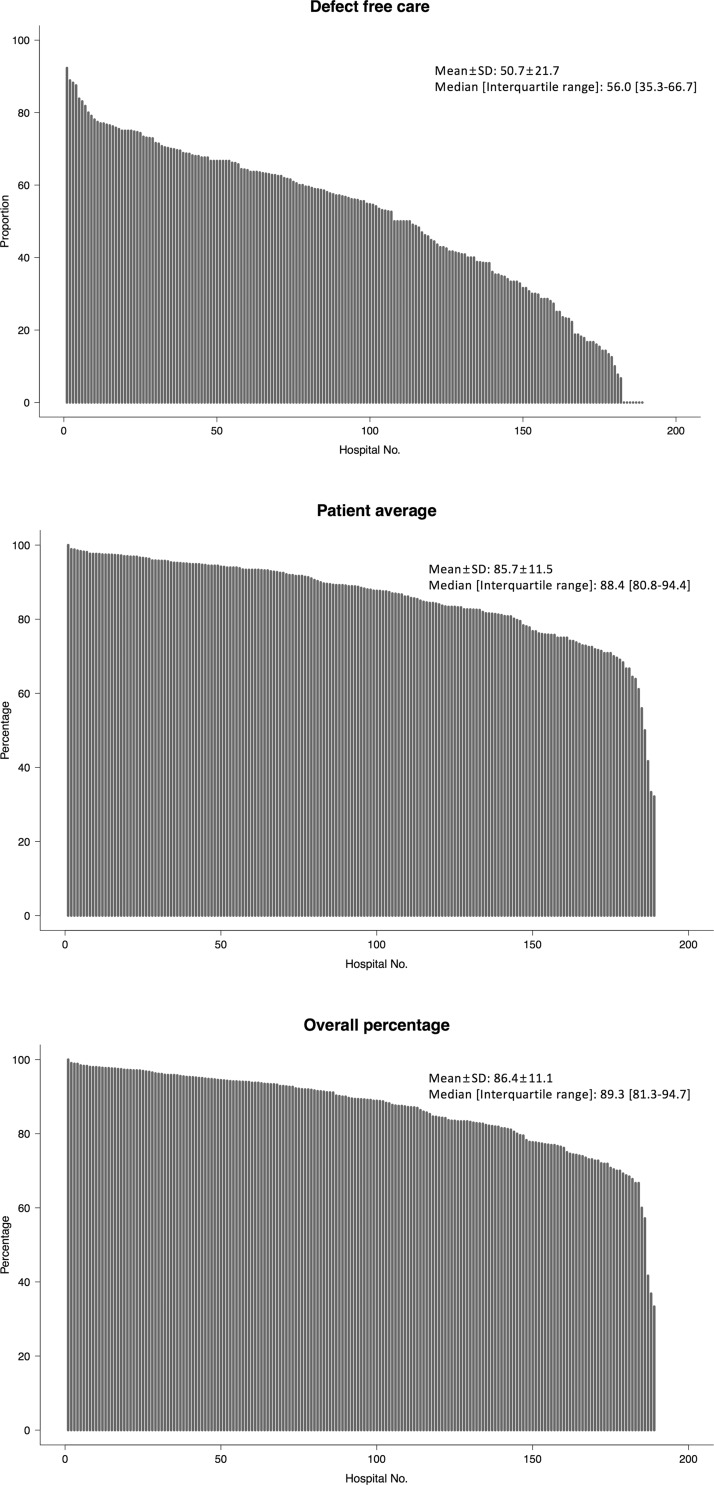

Hospital disparities were examined using the data from the 6th assessment performed in 2014. Being treated in hospitals with 500 or more beds, more stroke admissions per month, more IV tPA cases per month and providing stroke unit care increased the likelihood of receiving higher quality of stroke care (Figure 2). This tendency is most evident for defect-free stroke care (all-or-none). Large hospital disparities in the summary measures, especially in defect-free stroke care (all-or-none) were reported (hospital mean = 50.7%; SD = 21.7%) (Figure 3). Hospitals having more stroke cases, having more IV tPA cases and providing stroke unit care were more likely to provide more timely treatments (Supplemental Table IV).

Figure 2.

Associations between hospital characteristics and quality of stroke care. (a) Defect-free stroke care (all-or-none) measure and (b) patient average measure. CI: confidence interval.

Cochran–Armitage trend tests, or beta-logistic models were used to assess P-for-trends.

Figure 3.

Center disparities in summary measures of acute stroke care.

Comparisons of quality of stroke care among Korea, the US, and Taiwan

Quality of stroke care in Korea was compared with that in other countries in terms of various quality measures based on data from the 5th (2013) and 6th (2014) assessments and the summary measures for these comparisons were based on the six core measures including lipid-lowering drugs at discharge. Defect-free stroke care (all-or-none) was lower in Korea (71%) than the US (94%) and patient average was higher in Korea (90%) than Taiwan (73%) (Table 2). Early administration of IV tPA, measured by the IV tPA 2 h (3.5 h) variable, was higher in Korea than other two countries. Prescription rates of antithrombotics and lipid-lowering drugs at discharge were lower in Korea than the US, while other core measures were comparable between Korea and the US. Generally, the achievement of the individual performance measures was higher in Korea than Taiwan.

Table 2.

International comparisons of performance measures.

| % | Korea (2013–2014) | GWTG-Stroke (2013–2015) | GWTG-Taiwan (2006–2008) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Summary measuresa | |||

| Defect-free stroke care (all-or-none) | 71.2 | 94.1 | NA |

| Patient average | 89.6 | NA | 73.1 |

| Overall percentage | 90.3 | NA | NA |

| Core measures | |||

| Acute | |||

| IV tPA 2 h (3.5 h) | 94.6 | 90.3 | 8.8 |

| Early antithrombotics | 99.96 | 97.5 | 94.1 |

| DVT prophylaxis | NA | 98.8 | NA |

| Discharge | |||

| Discharge antithrombotics | 92.3 | 99.1 | 85.5 |

| Anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation | 98.9 | 96.5 | 28.3 |

| Smoking cessation | 99.7 | 97.7 | NA |

| Lipid-lowering drugs at discharge | 74.6 | 97.9 | 38.7 |

| In-hospital mortality | 3.9 | 4.5 | 4.0 |

GWTG: get with the guideline; NA: not available; IV tPA: intravenous tissue-plasminogen activator; DVT: deep vein thrombosis.

aSummary measures used in this table were obtained using all the six core performance measures.

Discussion

Based on the ASQAP database of 43,793 acute stroke patients who were admitted to 258 acute care hospitals in South Korea and were benchmarked against GWTG-Stroke performance measures, we have demonstrated the following: (1) overall, the performance of the Korean hospitals was comparable to that of other countries; (2) there was a marked improvement in quality of stroke care over time; and (3) about 30% of stroke patients still did not receive defect-free stroke care (all-or-none), and there were large hospital disparities nationwide.

The achievement of defect-free stroke care (all-or-none) based on the six core measures including lipid-lowering drugs at discharge in our study was 71.2% in 2013–2014, which was comparable to that of 73% in 2003–2009 in the US GWTG-Stroke,9 but much lower than the contemporary rate (2013–2015) of 94% in the US GWTG-Stroke.17 Despite proven evidence of statin therapy for stroke prevention,18 the statin prescription rate at discharge was 74.6% in this study, which is similar to the value of 78.6% reported in a previous Korean study.19 The difference in defect-free stroke care (all-or-none) between Korea and the US appears to be driven mainly by the difference in the statin prescription rate, which was 97.9% in 2013–2015 in the US GWTG-Stroke (Table 2).17 Comparisons with European countries were not possible due to substantial heterogeneity in the definitions of performance measures.8,20

Of the patients eligible for IV tPA, 94.6% were treated with IV tPA within the time window in 2013–2014; this figure is higher than the 42% for Portugal (2010), the 60% for Germany (2012), the 81% for the UK (2014),21 and the highest rate of 85.2% in 2010–2013 in the US (Target: Stroke Initiative),2 and comparable to 94.1% in 2013–2015 in the US GWTG-Stroke.17 Furthermore, 79% of the patients receiving IV tPA were treated within 60 min of arrival in our study, compared to 27% in Australia,22 68% in America17 and 64% in the UK.23 The marked improvement reported in the door-to-needle time door-to metric in the ASQAP was similar to that in the Target: Stroke Initiative of the US.2

The achievement of stroke care quality in Korea is encouraging in this study. However, hospital disparities in defect-free stroke care (all-or-none) were quite large (Figure 2), and the achievement of defect-free stroke care (all-or-none) was associated with lower in-hospital mortality and higher rates of discharge to home. Implementation of a nationwide collaborative learning and feedback program7 and more rigorous adherence to guidelines might reduce the variation of stroke care among hospitals, enhance the achievement of defect-free stroke care (all-or-none), and consequently improve clinical outcomes.

In Korea, standards for stroke unit care were proposed in 2008, and the certification of stroke units was started in 2012 by the Korean Stroke Society. Although the number of hospitals providing stroke unit care increased from 25 in 2008 to 65 in 2014 (Figure 1), only 47% of acute stroke patients were treated in hospitals equipped with stroke units in Korea (Supplemental Table II), which is higher than the 30% average in Europe, but much lower than that of Australia (67%), the UK (83%), Czech Republic (85%), and Sweden (88%).21,22 By emphasising on stroke unit care, one may reduce stroke dependence and mortality and overcome certain perceived disadvantages regarding stroke care in smaller hospitals.22,24 Reimbursement for stroke unit care by the Korean government was initiated in 2017. In addition to this expanded coverage of stroke unit care, establishing certified stroke units in rural areas might lead to further spread of integrated stroke care,25 reducing hospital disparities in quality of stroke care and promoting adherence to current stroke guidelines.11,12,26 Through these efforts, we expect that the rates of acute care hospitals providing stroke unit care in Korea might attain the rates reported for Australia and European countries.

This study shows that the contribution of hospitals having little experience in acute stroke care but playing a role as acute care hospitals is not to be ignored. About 30% of all acute stroke patients were treated in hospitals with an average IV tPA case of less than one per month (Supplemental Table II), and these hospitals were less likely to provide IV tPA within 60 min of arrival (Supplemental Table IV). A previous study based on the GWTG-Stroke database also demonstrated an association between the volume of tPA treatment and timely administration of IV tPA.27 One must keep in mind that the concept of primary and comprehensive stroke centres is in its infancy in Korea. Furthermore, the Korean emergency medical services (EMS) do not consider the hospital capability of acute stroke care when delivering stroke patients to acute care hospitals. Thus, establishment of a nationwide stroke network with prehospital notification and timely EMS transport to stroke care-capable hospitals is urgently required for improving acute stroke care in Korea.

This study has several limitations. First, retrospective observational studies are subject to confounding and have limitation in generalisability of study findings. However, because all Koreans are obliged to participate in the National Health Insurance program and each hospital requests reimbursements for almost all the medical services that they have provided, we believe that we were able to analyse the vast majority of acute stroke patients admitted to hospitals in Korea during each assessment period. Second, the ASQAP is an external audit program based on self-report by enrolled hospitals. HIRA initiated a financial incentive plan based on reporting indicators in October 2011. Thus, selection bias or overreporting related to applying eligibility criteria more strictly or widely during the assessment periods might occur. Extremely high rates of IV tPA 2 h (3.5 h) and high achievements in most performance measures might be partly explained by this bias. Third, international comparisons of stroke care quality might be inappropriate because of heterogeneity in study periods, enrolment criteria, and definitions of performance measures. Data from Taiwan that we used were collected in earlier time epochs than those used for this study, which might explain why Taiwan had a worse quality metric. We modified the definitions of performance measures to minimise differences between the ASQAP and the GWTG-Stroke measures.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of this study, the quality of acute stroke care in Korea has improved over time and is comparable to that in other countries. Stroke care quality, however, was variable among hospitals, and the distribution of specialised stroke care facilities was unbalanced between urban and rural areas. Implementation of optimal preventive strategies and development of a nationwide stroke network would improve the quality of acute stroke care.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Quality of acute stroke care in Korea (2008–2014): Retrospective analysis of the nationwide and nonselective data for quality of acute stroke care by Hong-Kyun Park, Seong-Eun Kim, Yong-Jin Cho, Jun Yup Kim, Hyunji Oh, Beom Joon Kim, Jihoon Kang, Keon-Joo Lee, Min Uk Jang, Jong-Moo Park, Kwang-Yeol Park, Kyung Bok Lee, Soo Joo Lee, Ji Sung Lee, Juneyoung Lee, Ki Hwa Yang, Ah Rum Choi, Mi Yeon Kang, Eric E Smith, Philip B Gorelick and Hee-Joon Bae in European Stroke Journal

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was performed by the Joint Project on Quality Assessment Research of the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service, Republic of Korea, and supported by a fund (2017ER620101#) by Research of Korea Centres for Disease Control and Prevention.

Informed consent

Stipulation of written informed consent from the study subjects was waived as the study subjects were de-identified in the database.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service in Korea.

Guarantor

Hee-Joon Bae.

Contributorship

Hong-Kyun Park contributed to the study design, data interpretation, manuscript drafting, and final approval of the manuscript.

Seong-Eun Kim contributed to the data analysis, data interpretation, review of draft, critical revision, and final approval of the manuscript.

Yong-Jin Cho, Jun Yup Kim, Hyunji Oh, Beom Joon Kim, Keon-Joo Lee, Jihoon Kang, Min Uk Jang, Jong-Moo Park, Kwang-Yeol Park, Kyung Bok Lee, Soo Joo Lee, Eric E. Smith, and Philip B. Gorelick, and PhDs Ji Sung Lee, and Juneyoung Lee contributed the review of the study design, data interpretation, critical revision, and final approval of the manuscript.

Ki Hwa Yang, Ah Rum Choi, and Mi Yeon Kang contributed to the data interpretation, review of draft, and final approval of the manuscript.

Hee-Joon Bae contributed to the study design, data interpretation, manuscript drafting, critical revision, and final approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Cadilhac DA, Andrew NE, Lannin NA, et al. Quality of acute care and long-term quality of life and survival: the Australian Stroke Clinical Registry. Stroke 2017; 48: 1026–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fonarow GC, Zhao X, Smith EE, et al. Door-to-needle times for tissue plasminogen activator administration and clinical outcomes in acute ischemic stroke before and after a quality improvement initiative. JAMA 2014; 311: 1632–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reeves MJ, Fonarow GC, Smith EE, et al. Representativeness of the get with the guidelines-stroke registry: comparison of patient and hospital characteristics among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with ischemic stroke. Stroke 2012; 43: 44–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meretoja A, Roine RO, Kaste M, et al. Stroke monitoring on a national level: perfect stroke, a comprehensive, registry-linkage stroke database in Finland. Stroke 2010; 41: 2239–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner M, Barber M, Dodds H, et al. Implementing a simple care bundle is associated with improved outcomes in a national cohort of patients with ischemic stroke. Stroke 2015; 46: 1065–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appelros P, Jonsson F, Asberg S, et al. Trends in stroke treatment and outcome between 1995 and 2010: observations from Riks-Stroke, the Swedish stroke register. Cerebrovasc Dis 2014; 37: 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsieh FI, Jeng JS, Chern CM, et al. Quality improvement in acute ischemic stroke care in Taiwan: the breakthrough collaborative in stroke. PLoS One. 2016; 11: e0160426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cadilhac DA, Kim J, Lannin NA, et al. National stroke registries for monitoring and improving the quality of hospital care: a systematic review. Int J Stroke 2016; 11: 28–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonarow GC, Reeves MJ, Smith EE, et al. Characteristics, performance measures, and in-hospital outcomes of the first one million stroke and transient ischemic attack admissions in get with the guidelines-stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2010; 3: 291–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim BJ, Park JM, Kang K, et al. Case characteristics, hyperacute treatment, and outcome information from the clinical research center for stroke-fifth division registry in South Korea. J Stroke 2015; 17: 38–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014; 45: 2160–2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith EE, Saver JL, Alexander DN, et al. Clinical performance measures for adults hospitalized with acute ischemic stroke: performance measures for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014; 45: 3472–3498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Comprehensive quality report of national health insurance. Korea: Author, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwamm LH, Fonarow GC, Reeves MJ, et al. Get with the guidelines-stroke is associated with sustained improvement in care for patients hospitalized with acute stroke or transient ischemic attack. Circulation 2009; 119: 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keenan CR, White RH. The effects of race/ethnicity and sex on the risk of venous thromboembolism. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2007; 13: 377–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsieh FI, Lien LM, Chen ST, et al. Get With the guidelines-stroke performance indicators: surveillance of stroke care in the Taiwan Stroke Registry: get with the guidelines-stroke in Taiwan. Circulation 2010; 122: 1116–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Man S, Zhao X, Uchino K, et al. Comparison of acute ischemic stroke care and outcomes between comprehensive stroke centers and primary stroke centers in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2018; 11: e004512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amarenco P, Labreuche J. Lipid management in the prevention of stroke: review and updated meta-analysis of statins for stroke prevention. Lancet Neurol. 2009; 8: 453–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong KS, Oh MS, Choi HY, et al. Statin prescription adhered to guidelines for patients hospitalized due to acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack. J Clin Neurol 2013; 9: 214–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiedmann S, Norrving B, Nowe T, et al. Variations in quality indicators of acute stroke care in 6 European countries: the European Implementation Score (EIS) Collaboration. Stroke 2012; 43: 458–463. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevens EE, Wang E, McKevitt Y, et al. The burden of stroke in Europe: the challenge for policy makers. 2017. www.stroke.org.uk/sites/default/files/the_burden_of_stroke_in_europe_-_challenges_for_policy_makers.pdf (accessed 9 May 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Stroke Foundation. National stroke audit – acute services report. Melbourne, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Physicians RCo. Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme (SSNAP). National results clinical, April-July 2017, www.strokeaudit.org/results/Clinical-audit/National-Results.aspx (2017, accessed 2 May 2019).

- 24.Man S, Schold JD, Uchino K. Impact of stroke center certification on mortality after ischemic stroke: the medicare cohort from 2009 to 2013. Stroke 2017; 48: 2527–2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cadilhac DA, Ibrahim J, Pearce DC, et al. Multicenter comparison of processes of care between stroke units and conventional care wards in Australia. Stroke 2004; 35: 1035–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clinical Research Center for Stroke. Clinical practice guidelines for stroke: English version. 2nd ed UK: Author, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Saver JL, et al. Timeliness of tissue-type plasminogen activator therapy in acute ischemic stroke: patient characteristics, hospital factors, and outcomes associated with door-to-needle times within 60 minutes. Circulation 2011; 123: 750–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Quality of acute stroke care in Korea (2008–2014): Retrospective analysis of the nationwide and nonselective data for quality of acute stroke care by Hong-Kyun Park, Seong-Eun Kim, Yong-Jin Cho, Jun Yup Kim, Hyunji Oh, Beom Joon Kim, Jihoon Kang, Keon-Joo Lee, Min Uk Jang, Jong-Moo Park, Kwang-Yeol Park, Kyung Bok Lee, Soo Joo Lee, Ji Sung Lee, Juneyoung Lee, Ki Hwa Yang, Ah Rum Choi, Mi Yeon Kang, Eric E Smith, Philip B Gorelick and Hee-Joon Bae in European Stroke Journal