Abstract

Background

The increasing prevalence of chronic disease states, such as hypertension and dyslipidemia, in the United States has placed a growing economic burden on the nation's healthcare system, and incentives for cost reductions have been used by various private health insurers.

Objective

To analyze the clinical outcomes of pharmacy department–managed, employer-sponsored wellness programs for dyslipidemia and hypertension in a 2-hospital health system.

Methods

Using a retrospective chart review, we evaluated outcomes of employees and their spouses who were enrolled in our dyslipidemia and hypertension Wellpath programs between November 2015 and April 2017. Employees or their spouses were referred to these programs, which were coordinated by the pharmacy department. Enrollees completed in-person appointments and telephone interviews with a pharmacist or an advanced practice nurse, who provided evidence-based lifestyle and pharmacologic recommendations. The primary outcomes were lipid changes in the dyslipidemia program, and changes in systolic or diastolic blood pressure in the hypertension program. The secondary outcome was the total number of pharmacologic interventions. Paired sample t-tests were used to assess the results.

Results

A total of 138 enrollees met the study inclusion criteria. The mean difference in systolic and diastolic blood pressure between baseline and completion of the program was −8.33 mm Hg (P = .001; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.58–13.09) and −3.67 mm Hg (P = .015; 95% CI, 0.75–6.58), respectively. The mean differences in total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, and triglycerides from baseline were −27.67 mg/dL (P <.001; 95% CI, 19.36–35.99), −23.16 mg/dL (P <.001; 95% CI, 15.41–30.92), and −67.62 mg/dL (P <.001; 95% CI, 30.73–104.52), respectively. In all, 46 (46.9%) of the 98 enrollees in the dyslipidemia program required a pharmacologic intervention. In the hypertension program, 18 (31.6%) of 57 enrollees required a pharmacologic intervention.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate that the use of a pharmacy department–managed, employer-sponsored wellness program that is managed by pharmacists and an advanced practice nurse could lead to significant reductions in blood pressure and lipid levels for employees and for their spouses who are enrolled in the program.

Keywords: blood pressure, dyslipidemia, employer-sponsored wellness program, hypertension, lipid levels, pharmacy department

In 2015, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)'s National Center for Health Statistics released a report on the health of the US population, which showed that at that time, 30.8% of Americans aged >20 years had hypertension and 27.4% had dyslipidemia.1 The increased prevalence of chronic diseases over the past 2 decades has placed a substantial economic burden on the healthcare system.1 In 2000, the national healthcare expenditure totaled $1.2 trillion; by 2014, that number had more than doubled to $2.6 trillion.1 The strain of increasing healthcare costs is felt by government and private insurance companies alike.

Rising demand for and higher costs of healthcare have created a shift toward managing chronic disease states within the ambulatory care setting. The Veterans Affairs outpatient clinics led the way in revolutionizing the model for chronic disease state management with the use of pharmacists; their scope of practice evolved largely in the 1990s and 2000s as the Veterans Affairs system implemented more autonomous practices, such as direct patient care, collaborative medication management, and pharmacist-managed clinics.2,3 These responsibilities are now at the core of pharmacist-managed ambulatory care clinics around the United States.

Ambulatory care clinics offer a variety of services, including, but not limited to, transitional care, anticoagulation services, diabetes education, hypertension and lipid management, and tobacco cessation.4–7 Employer-sponsored wellness programs that focus on many of these ambulatory care services have become increasingly popular, because they can decrease morbidity among employees and reduce costs for employers.4–7 Recent publications have highlighted the impact that employer-sponsored wellness programs can have on diabetes management, specifically on hemoglobin (Hb)A1c reduction and weight management.4,5

Although some studies have addressed the management of hypertension in an ambulatory care setting, few studies have followed patients with dyslipidemia in an employer-sponsored wellness program.8,9 In addition, to our knowledge, there is no available literature that describes employer-sponsored wellness programs within a community health system that is managed by the pharmacy department; however, this may be a viable opportunity to expand pharmacy services.

Wellpath is an employee health and wellness program that is implemented by the pharmacy department for hypertension and dyslipidemia at St Joseph's/Candler Health System, a self-insured community health system in Savannah, GA. The Wellpath program links wellness initiatives to health insurance discounts. The hypertension and dyslipidemia programs are supported by all hospital administrators, including the Director of Wellness and the Director of Pharmacy.

To be eligible for a discounted insurance premium, employees and their spouses participate in an annual screening, which includes a health risk assessment, biometrics, fasting lipid panel, HbA1c levels, and age- and sex-recommended screenings. Age- and sex-recommended screenings may include primary care physician annual physical examination appointments, mammograms, and colonoscopies. The initial screenings identify enrollees who are eligible for tobacco cessation, weight management, or chronic disease state management programs.

The objective of our study was to analyze the outcomes associated with this pharmacy department–managed employee health and wellness program, which is provided by trained pharmacists and an advanced practice nurse for chronic disease states, including hypertension and dyslipidemia.

KEY POINTS

-

▸

The increase in the prevalence and cost of chronic diseases has shifted the management of chronic disease states to the ambulatory care setting.

-

▸

This retrospective chart review analyzed the clinical outcomes of pharmacy department–managed, employer-sponsored wellness programs for dyslipidemia and for hypertension.

-

▸

A total of 138 employees and/or family members were enrolled in the dyslipidemia program, the hypertension program, or were dually enrolled in both programs.

-

▸

The mean differences in systolic and diastolic blood pressure from baseline to the end of the program were −8.33 mm Hg and −3.67 mm Hg, respectively.

-

▸

The mean differences in total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, and triglycerides from baseline were −27.67 mg/dL, −23.16 mg/dL, and −67.62 mg/dL.

-

▸

Approximately 47% of enrollees in the dyslipidemia cohort and 32% in the hypertension cohort required a pharmacologic intervention.

-

▸

Employer-sponsored wellness programs managed by the pharmacists can lead to significant reductions in blood pressure and lipid levels and reduced healthcare costs.

-

▸

Long-term studies are needed to evaluate the financial benefits such programs provide to self-insured hospital systems.

Methods

In this retrospective chart review, we evaluated employees and their spouses at St Joseph's/Candler Hospitals in Savannah, GA, who were enrolled in the dyslipidemia and the hypertension Wellpath programs between November 2015 and April 2017. All employees of the health system and their spouses who had a systolic blood pressure of >140 mm Hg and a diastolic blood pressure of >90 mm Hg or whose low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol level was >130 mg/dL at their annual biometric screening were referred by the wellness nurse practitioner, who is employed by the Director of Wellness, to the pharmacy department–managed ambulatory care clinic for an evaluation of lifestyle and pharmacologic interventions. Although the clinic is managed by the health system's pharmacy department, an advanced practice nurse is employed by and contributed to managing enrollees in the Wellpath program.

The pharmacists and the advanced practice nurse were trained on program procedures, disease state education, and disease-specific medication guidelines for hypertension and for dyslipidemia. On referral, the enrollees met with a clinical pharmacist or an advanced practice nurse between 2 times and 16 times, depending on risk stratification, to monitor and reduce their cardiovascular risk through evidence-based recommendations for education, lifestyle modifications, and pharmacotherapy. The advanced practice nurse consulted with a clinic pharmacist if pharmacologic interventions were required. Enrollees who did not complete an initial visit and at least 1 follow-up encounter were marked as noncompliant and were excluded from the study.

The hypertension and the dyslipidemia management programs consisted of 3 risk levels that were divided based on risk assessment. For hypertension, level 1 enrollees had a systolic blood pressure of 140 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg and a diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg and were not taking antihypertensive medications; enrollees in level 2 had a systolic blood pressure of 150 mm Hg to 160 mm Hg and a diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg to 100 mm Hg and/or were currently prescribed antihypertensive medications; and level 3 candidates were taking 2 or more medications for hypertension and had a systolic blood pressure of >60 mm Hg and a diastolic blood pressure of >100 mm Hg.

For dyslipidemia, the level 1 risk group had LDL cholesterol levels of 130 mg/dL to 159 mg/dL, level 2 had LDL levels of 160 mg/dL to 190 mg/dL, and level 3 had LDL levels of >190 mg/dL. All the enrollees were expected to complete the program within 16 encounters, regardless of the program or the risk group.

The initial visits took place at the clinic to allow a clinical pharmacist or an advanced practice nurse to evaluate the enrollee's blood pressure or LDL cholesterol level. The initial visits in each program included a collection of the patient's medical history, family history, social history, and current medication review. In addition, evaluations of vital signs, HbA1c (for patients with a history of diabetes), and medication adherence were performed. The initial visit in the dyslipidemia program included a lipid panel. Enrollees were asked to keep a diet and exercise log for 1 week, and a registered dietitian was consulted if indicated. Education was a key component of all initial visits.

After recording the enrollees' blood pressure at the initial visit, the providers utilized educational tools available from the CDC to provide disease state education, as well as lifestyle modifications, including weight reduction, stress management, alcohol limitation, and tobacco cessation. All enrollees, including those in the hypertension and the lipid management programs, were counseled on the importance of implementing the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet and regular exercise in reaching their blood pressure goal.

Enrollees in the hypertension risk levels 2 and 3 groups received detailed information about the common drug classes that are prescribed for hypertension. Primary care physicians were contacted to implement or adjust any antihypertensive and/or over-the-counter pharmacotherapy according to 2017 evidence-based guidelines.10

For lipid management, the 10-year and lifetime atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD) risks were calculated to guide counseling and medication management, and the enrollees were provided disease state education, including patient handouts. If warranted according to the 2013 American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guideline recommendations, primary care physicians were contacted to implement lipid-lowering and/or over-the-counter therapy.11

If inappropriate therapies were identified in the patient's medical history, recommendations were provided to the enrollee's primary care physician. Throughout the educational visit, clinicians made lifestyle intervention recommendations to enrollees regarding exercise and diet changes. Progress notes were recorded electronically, and the primary care physician was contacted after the first visit and then quarterly or as indicated throughout the program.

Follow-up appointments were conducted by phone or in clinic. The phone follow-ups focused on barriers to improvements in, and progress toward, lifestyle modification goals, as well as medication adherence, if applicable. Vital signs and medication adherence were assessed during each clinic visit; diet and exercise logs were requested quarterly. For the hypertension-related visits, enrollees were asked to keep a self-monitoring blood pressure log for 1 week before each in-office visit to assess regular blood pressure control. For the dyslipidemia-related visits, enrollees had a lipid panel review at a follow-up visit for levels 1 and 2 and, if indicated for changes in medication therapy, on each visit for level 3. All follow-up visits reassessed the enrollees' goals for lifestyle modifications and medication adherence if applicable.

The outcomes provided in this article are descriptive in nature and provide pilot data from the implementation of the Wellpath hypertension and dyslipidemia programs. The primary end point for enrollees in the hypertension management program was the change in systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Only blood pressure recorded during office visits was used for data analysis. The primary end point for the dyslipidemia program was a change in total cholesterol, LDL, triglycerides, or high-density lipoprotein (HDL).

All enrollees' data were collected from electronic medical records. The baseline blood pressure or lipid values and the enrollees' final blood pressure or lipid values were used to perform a 2-sided paired sample t-test with an alpha of 0.05. A secondary outcome for both programs was the number and types of pharmacologic interventions made by the team of pharmacists and an advanced practice nurse.

Results

Of approximately 4000 people employed by St Joseph's/Candler Health System, 201 were referred to either the hypertension or the dyslipidemia program. This analysis includes 138 enrollees who completed at least 1 of these programs, including 98 patients in the dyslipidemia program, 57 in the hypertension program, and 17 patients who were dually enrolled in both programs. The median age of the patients in the dyslipidemia and hypertension programs was 55 years and 53 years, respectively. The dyslipidemia program included 59.2% female patients and 40.8% male patients; the hypertension program included 78.9% female patients and 21.1% male patients.

The mean difference in systolic and diastolic blood pressure from baseline to the completion of the program was −8.33 mm Hg (P = .001; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.58–13.09) and −3.67 mm Hg (P = .015; 95% CI, 0.75–6.58), respectively (Table).

Table.

Mean Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure Reduction, and Dyslipidemia Outcomes, Except High-Density Lipoprotein

| Hypertension (N = 57) | Mean baseline, mm Hg | Mean completion, mm Hg | Change in mean, mm Hg (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic blood pressure | 142.7 | 134.4 | −8.33 (3.58–13.09) | .001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 81.2 | 77.5 | −3.67 (0.75–6.58) | .015 |

| Dyslipidemia (N = 98) | Mean baseline, mg/dL | Mean completion, mg/dL | Change in mean, mg/dL (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol | 238.6 | 210.9 | −27.67 (19.36–35.99) | <.001 |

| Low-density lipoprotein | 147.1 | 123.9 | −23.16 (15.41–30.92) | <.001 |

| High-density lipoprotein | 54.0 | 55.9 | +1.88 (−3.91–0.155) | .07 |

| Triglycerides | 248.1 | 180.4 | −67.62 (30.73–104.52) | <.001 |

CI indicates confidence interval.

The mean difference from baseline in total cholesterol, LDL, and triglycerides was −27.67 mg/dL (P <.001; 95% CI, 19.36–35.99), −23.16 mg/dL (P <.001; 95% CI, 15.41–30.92), and −67.62 mg/dL (P <.001; 95% CI, 30.73–104.52), respectively, which were all statistically significant. The HDL levels increased 1.88 mg/dL from baseline (P = .07; 95% CI, −3.91–0.155), which was not statistically significant.

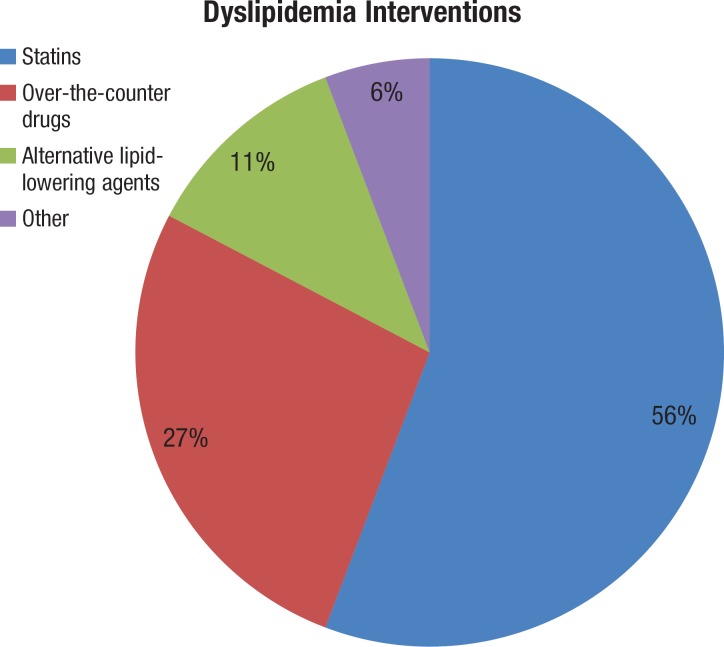

All enrollees required education regarding lifestyle modification, including diet and exercise. Of the 98 enrollees in the dyslipidemia program, 46 (46.9%) were not receiving appropriate therapy before enrolling in the program and required a pharmacologic intervention based on guideline recommendations.11 The majority (N = 26; 56%) of pharmacologic interventions in the dyslipidemia program were recommendations for the initiation or modification of statin therapy (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Pharmacologic Interventions for Patients with Dyslipidemiaa.

aDyslipidemia pharmacologic interventions were made in 46.9% of enrollees. The majority of interventions involved the addition or change of a statin. Other interventions included initiating over-the-counter drugs and nonstatin, prescription, and lipid-lowering agents.

A total of 12 (27%) interventions in the dyslipidemia program were for the initiation or discontinuation of over-the-counter therapies, including fish oil, niacin, and red yeast rice. In addition, 5 (11%) interventions were for the initiation of nonstatin prescription lipid-lowering agents. The remaining 3 (6%) interventions in the dyslipidemia program targeted the discontinuation of estrogen-containing drugs because of the possible increased risk for CVD.

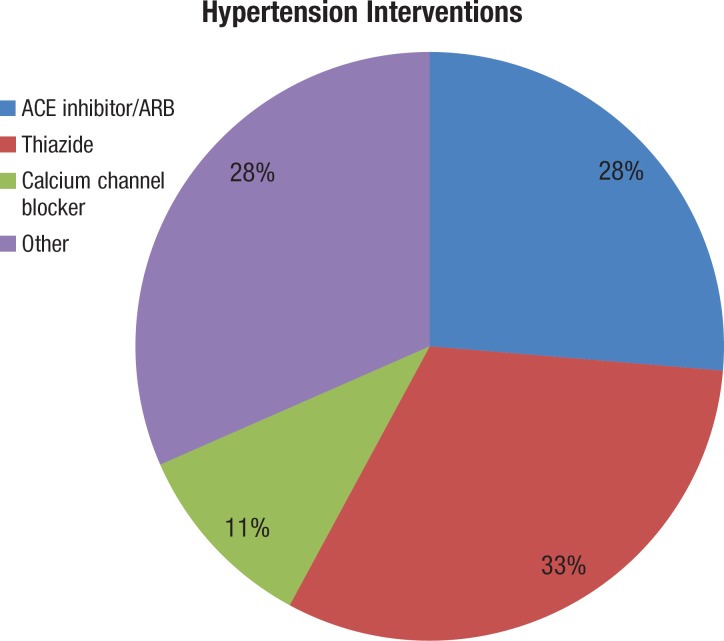

All enrollees in the hypertension program received lifestyle education, including diet and exercise. Many enrollees were receiving pharmacologic therapy before enrollment in the program; however, pharmacologic interventions were made in 18 (31.6%) of the 57 enrollees in the hypertension group based on evidence-based guidelines.10 The pharmacologic interventions were split among 2 of the guideline-recommended first-line agents.10

The initiation of a thiazide diuretic accounted for 6 (33%) of the hypertension interventions, whereas angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker initiation accounted for 5 (28%) of the interventions (Figure 2). Calcium channel blocker modifications constituted 2 (11%) of the pharmacologic interventions.

Figure 2. Pharmacologic Interventions for Patients with Hypertensiona.

aHypertension pharmacologic interventions were made in 31.6% of enrollees. In all, 72% of interventions involved the addition of a guideline-recommended first-line agent, including ACE inhibitors/ARB, thiazide diuretics, and calcium channel blockers. The remaining 28% of interventions included pill burden reductions and supplement changes.

ACE indicates angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

The remaining 5 (28%) pharmacologic interventions in the hypertension program included discontinuations of nonessential medications (eg, estrogen) and supplements (eg, stimulants) that increase blood pressure, or reductions in pill burden by initiating a combination drug therapy (eg, calcium channel blockers plus angiotensin receptor blocker and thiazide, or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor plus thiazide combination tablets).

All the recommendations for interventions were submitted to the enrollees' primary care physician and were accepted. All the enrollees were counseled on implementing lifestyle modifications, including diet and exercise.

Discussion

These results demonstrate that a health-system pharmacy department–managed, employer-sponsored wellness program may lead to significant reductions in blood pressure and lipid levels and may be an option to expand services. According to the CDC, in 2015 and 2016, more than 12% of adults aged ≥20 years had a total cholesterol of >240 mg/dL,12 and based on CDC data from 2005 to 2012, only approximately 56% of US adults who could benefit from cholesterol-lowering medicines were taking these drugs.13

Furthermore, the CDC estimated that in 2015 and 2016, the prevalence of hypertension was 29% among the US adult population, and only 48.3% of adults with hypertension had their disease under control.14 Based on the CDC's data, our results largely align with the national average and demonstrate a mechanism to narrow the gap of patients with uncontrolled hypertension by providing pharmacologic interventions. In our study, reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure were achieved with the implementation of a wellness program, and, apart from a nonsignificant increase in HDL, all lipid values decreased significantly. Pharmacists and an advanced practice nurse performed a vital role in the healthcare team by counseling patients on lifestyle modifications and by implementing pharmacologic as well as nonpharmacologic interventions.

Such a wellness program would benefit from the implementation of a collaborative practice agreement that allows pharmacists and advanced practice nurses to change medications under an agreed protocol. The current process for implementing pharmacologic interventions is laborious in our institution, and limits practitioners' scope of practice.

Future long-term studies should focus on the benefits of re-enrollment in the wellness program and the monetary benefit this program provides to the self-insured hospital system.

Recently, pharmacists' services that are provided in unique settings, such as in barber shops, have been shown to improve patient outcomes.15

Limitations

In our study, the average baseline blood pressure (143/81 mm Hg) limited the potential for reduction in blood pressure values and did not accurately represent the 3 risk levels of the program. A requirement of 2 consecutive blood pressure readings above target would be beneficial to improve the program specificity of higher-risk enrollees. According to the 2017 AHA hypertension guidelines, an average of 2 or more readings should be used on 2 or more separate occasions to diagnose a patient with hypertension.10 However, the purpose of the employee wellness program was to prevent comorbidities and manage preexisting chronic disease states.

Another limitation of this study is the use of dyslipidemia risk levels. The most recent ACC/AHA guidelines recommend that providers not treat LDL levels and instead manage patients based on atherosclerotic CVD risk score.11 Although atherosclerotic CVD risk score was used in the program when making pharmacologic recommendations for lipid-lowering interventions, enrolling patients based on atherosclerotic CVD risk stratification could add specificity to target higher-risk patients.

Finally, the analysis of the program presents another limitation because of the descriptive nature of the analysis, and the study's small sample size. Future studies are planned to be comparative in nature and to include a larger sample size to evaluate the efficacy of our programs.

Conclusion

With the rising trends of hypertension and dyslipidemia in the United States, pharmacists can provide effective preventive care and disease state management services through pharmacologic and lifestyle modifications to lessen the burden on the healthcare system and on patients. Innovative, pharmacist-managed programs are expanding in the country.

Our study demonstrates an opportunity in which a community health-system pharmacy department can use pharmacists and advanced practice nurses to provide services to employees and their spouses who have hypertension or dyslipidemia.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Michael Fulford for his assistance with the data analysis of this study.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr Misher, Dr Brown, and Dr Maguire have no conflicts of interest to report; Dr Schnibben has provided consulting to Pfizer.

Contributor Information

Anne Misher, Clinical Assistant Professor, Clinical and Administrative Pharmacy, University of Georgia College of Pharmacy and St Joseph's/Candler Health System, Savannah, GA.

Jessica Brown, Pharmacy Practice Resident, Baptist Memorial Health Care, Memphis, TN.

Christina Maguire, Pharmacy Practice Resident, Dell Seton Medical Center at the University of Texas, Austin.

Alix P. Schnibben, Clinical Pharmacy Specialist in Ambulatory Care, St Joseph's/Candler Health System, and Adjunct Clinical Assistant Professor, University of Georgia College of Pharmacy.

References

- 1. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2015: With Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. DHHS Publication No 2016–1232. May 2016. Updated June 22, 2017. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus15.pdf. Accessed October 20, 2017. [PubMed]

- 2. Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Handbook 1108.1 Clinical Pharmacy Services. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carmichael JM, Hall DL. Evolution of ambulatory care pharmacy practice in the past 50 years. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72:2087–2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yoder VG, Dixon DL, Barnette DJ, Beardsley JR. Short-term outcomes of an employer-sponsored diabetes management program at an ambulatory care pharmacy clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69:69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pinto SL, Kumar J, Partha G, Bechtol RA. Improving the economic and humanistic outcomes for diabetic patients: making a case for employer-sponsored medication therapy management. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:153–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Theising KM, Fritschle TL, Scholfield AM, et al. Implementation and clinical outcomes of an employer-sponsored, pharmacist-provided medication therapy management program. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35:e159–e163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fanous AM, Kier KL, Rush MJ, Terrell S. Impact of a 12-week, pharmacist-directed walking program in an established employee preventive care clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71:1219–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Berdine HJ, O'Neil CK. Development and implementation of a pharmacist-managed university-based wellness center. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2007;47:390–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lenz TL. Pharmacists improving health at the worksite. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2013;7:382–384. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:1269–1324. Errata in: Hypertension. 2018;71: e136–e139; Hypertension. 2018;72:e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(suppl 2):S1–S45. Errata in: Circulation. 2014;129(suppl 2): S46,–S48; Circulation. 2015; 132: e396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. High cholesterol facts. February 6, 2019. www.cdc.gov/cholesterol/facts.htm. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- 13. Mercado C, DeSimone AK, Odom E, et al. Prevalence of cholesterol treatment eligibility and medication use among adults—United States, 2005–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1305–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fryar CD, Ostchega Y, Hales CM, et al. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2015–2016. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief No 289. October 2017. www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db289.htm. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- 15. Victor RG, Blyler CA, Li N, et al. Sustainability of blood pressure reduction in black barbershops. Circulation. 2019;139:10–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]