Abstract

Previous research has suggested that the short (S)-allele of the 5-HT transporter gene-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) may confer “differential susceptibility” to environmental impact with regard to the expression of personality traits, depressivity and impulsivity. However, little is known about the role of 5-HTTLPR concerning the association between childhood adversity and empathy. Here, we analyzed samples of 137 healthy participants and 142 individuals diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (BPD) focusing on the 5-HTTLPR genotype (S/L-carrier) and A/G SNP (rs25531), in relation to childhood maltreatment and empathy traits. Whereas no between-group difference in 5-HTTLPR genotype distribution emerged, the S-allele selectively moderated the impact of childhood maltreatment on empathic perspective taking, whereby low scores in childhood trauma were associated with superior perspective taking. In contrast, L-homozygotes seemed to be largely unresponsive to variation in environmental conditions in relation to empathy, suggesting that the S-allele confers “differential susceptibility”. Moreover, a moderation analysis and tests for differential susceptibility yielded similar results when transcriptional activity of the serotonin transporter gene was taken into account. In conclusion, our findings suggest that the S-allele of the 5-HTTLPR is responsive to early developmental contingencies for “better and worse”, i.e. conferring genetic plasticity, especially with regard to processes involving emotional resonance.

Introduction

Social interaction requires reciprocal understanding of verbal and nonverbal signals, which entails the ability to understand others’ emotional states. The mechanism involved in this process is commonly referred to as “empathy”, which can be conceptualized as a semi-automatic sharing of another’s feelings, combined with the ability to differentiate between own and others’ affect [1–3]. Empathic deficits have been described in several neuropsychiatric conditions including autism [4, 5], schizophrenia [6, 7], psychopathy [8] and personality disorders, with mixed results for borderline personality disorder [9–13]. Our own research revealed that patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) showed selectively increased empathy for psychological pain compared to somatic pain [14], which was associated with childhood trauma, alexithymia and emotional empathy.

A plethora of studies suggests that the activity of the serotonergic system is critically involved in social behavior [15, 16]. With regard to gene-environment interaction, for instance, research in nonhuman primates demonstrated that length variations located in the promoter of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR) affects, together with rearing experiences, the level of serotonin metabolites in the cerebrospinal fluid and primate social behavior [17, 18]. In humans, the short (S) allele of the 5-HTTLPR has been associated with reduced serotonin transporter expression and function; it has also been found to be related to trait-anxiety, depression and impulsivity [19–23]. With regard to the processing of social cues, previous studies reported increased emotional reactivity, especially towards negatively biased stimuli [24–28] as well as heightened physiological stress responses in carriers of the S-allele [27, 29]. However, this polymorphic variation does not generally occur more frequently in clinical samples compared to the general population [30–32]. The general population is heterozygous, whereas the LL-genotype is less common, and the SS-variant relatively rare, in part depending on ethnicity [33, 34]. In addition, controversy exists about the effect of rs25531, a SNP within the 5-HTTLPR repetitive element, with the A-variant of the L-allele being associated with greater transcriptional activity and thus more efficient serotonin turnover [35–37], whereby a linkage disequilibrium between 5-HTTLPR and rs25531 has been described, with the rarer G-variant of rs25531 occurring more frequently together with the L-allele than with the S-allele [36, 38]. In recent years, researchers have become interested in the question, raised from an evolutionary point of view, why genes conferring increased risk to psychological dysfunction may be conserved in the genepool of human populations or have even been positively selected in recent millennia (see, for instance, [39]). As an alternative account to the widely-known “diathesis-stress-model” [40], the groups of Ellis [41] as well as Belsky and colleagues have suggested that genetic variants may not one-sidedly convey risk to the development of psychological dysfunction if associated with adverse life events, but that the very same polymorphic variation may confer lower than average risks if met with superior environmental conditions, foremost empathic parental care and emotional availability of care-givers [42]. Therefore, the “differential susceptibility” or “genetic plasticity” model emphasizes the difference between plasticity and resilience (i.e. unresponsiveness to environmental conditions; [43]).

With regard to the 5-HTTLPR, several studies reported an association of stressful live events and depression in SS-homozygotes or S-carrying heterozygotes ([44]; for meta-analyses, see [45, 46]), while others did not confirm these findings (for meta-analyses, see [31, 47]). Conversely, and in line with the “differential susceptibility” model, Pluess and colleagues reported that SS-carriers had higher scores in neuroticism when exposed to negative life events (within the last six months), whereas more positive life events were related to less than average neuroticism. This association was absent in L-carriers [48]. Similar findings were reported by Kuepper et al. [49] who also found an association of negative life events (over the life span) and neuroticism in S-allele carriers.

However, whether or not traumatic events during childhood specifically influence the development of empathic abilities, moderated by the 5-HTTLPR, is still unclear. Accordingly, the present study aimed to investigate the impact of the 5-HTTLPR on trait empathy in a sample of healthy participants and patients with BPD. We deliberately chose the two samples, because one was characterized by relatively few adverse childhood experiences, while the clinical group was coined by relatively high degrees of early maltreatment. We specifically hypothesized that the S-allele of the 5-HTTLPR would differentially impact on the association of childhood trauma with empathic perspective taking, whereas the L-allele would be unresponsive to environmental variation, with some potential modification according to the transcriptional activity of the serotonin transporter gene conveyed by the rs25531 polymorphism.

Material and methods

Participants

For the current study we recruited female in-patients with BPD, diagnosed according to DSM-5 criteria [50] from the LWL-University Hospital Bochum and female healthy control participants via advertisement. In total, 142 patients with BPD and 137 control participants were included. The age of participants was between 18 and 50 years. All participants were fluent in German, free of somatic illnesses and not pregnant (see Table 1 for comorbid disorders and medication of BPD patients). The control participants were free of medication and psychiatric disorders. Regarding the ethnical background, 95.2% were Caucasians, 4.4% originated from the Middle East (mainly of Turkish origin) and 0.4% from the Far East (Vietnamese). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the Ruhr-University Bochum (project number 4639–13). The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All participants gave their full informed consent in writing.

Table 1. Comorbid disorders and medication of patients with BPD in absolute (n) and relative (in %) amounts.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Comorbid disorders of patients with BPD | ||

| Depressive episode | 74 | 52.1 |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 21 | 14.8 |

| Phobic/ anxiety Disorder | 7 | 4.9 |

| Substance misuse | 42 | 29.8 |

| Medication | ||

| without regular medication | 59 | 41.5 |

| antidepressant | 51 | 35.9 |

| antipsychotic | 22 | 15.5 |

| antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs | 22 | 15.5 |

| antiepileptic | 8 | 5.6 |

| Other psychoactive drugs | 6 | 4.2 |

Questionnaires

Premorbid or general intelligence was estimated using the Mehrfachwahl-Wortschatz-Intelligenz-Test (MWT-A; [51]). Empathic abilities were measures using the German version of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index [52], called “Saarbrücker Persönlichkeits-Fragebogen” [53]. This questionnaire comprises four subscales, namely “perspective taking” (PT), “fantasy” (FS), “‘empathic concern” (EC) and “personal distress” (PD), and has proven reliable with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78. The present analysis focused on the “perspective-taking” score of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI), because this score is suggested to reflect cognitive empathy traits. In contrast, emotional empathy is more context dependent [54] and therefore emotional empathy scores are not appropriate for trait analyses (the validity of the other cognitive empathy score of the IRI, “fantasy”, is debated and therefore not included into the present analyses; [55]).

The short German version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) was used to assess the experience of maltreatment during childhood. The CTQ contains 28 questions tapping into the history of emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect and physical neglect. Participants were asked to rate the occurrence of maltreatment on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = very often) pertaining to their childhood and youth. Cronbach’s alpha values for the German version were high for all subscales (0.80), except for physical neglect [56]. In addition, we used the Beck’s Depression Inventory to assess the self-rated level of depressivity [57].

Genotyping

The DNA samples of participants were collected using Oragene OG-500 collection kits (DNA Genotek, Inc., Ottawa, ON, Canada) and by mouthwash with a commercially available mouthwash solution (Listerine). The DNA extraction was conducted according to the manufacturer's instructions of the Oragene Kit and by an adapted version for the mouthwash samples, using a standard salting-out procedure proposed by Miller et al. [58]. The DNA samples were diluted to a concentration of (20 ng/μL). The 5-HTTLPR and the rs25531 genotypes were determined as described by Wendland et al. [36].

Statistical analyses

We conducted a power analysis for interaction effects, i.e. the differences between slopes for the moderation model with the genotypes SS+SL and LL, using G*Power, Version 3.1.9.2. [59]. Power calculation for the current sample of 205 participants was determined by the following model: t-test-linear bivariate regression, two groups, difference between slopes, with α set at 0.05. Standard deviation of the residuals, the sample size and the difference between the slopes were also considered. Accordingly, the statistical power coefficient was 0.75.

In accordance with previous studies, we divided the sample into S-carriers (SS+SL pooled) and LL-carriers (e.g. [60–62]). This approach was justified, because previous studies reported no differences between SS and SL-carriers with regard to personality traits, suggesting a dominant-recessive type of association of the S-allele with personality (21).

Similarly, following previous research (e.g., [37]), subjects were further divided into groups according to the”transcriptional activity”(TA) of the rs25531.

Independent two-sample t-tests were used for comparisons of questionnaire data between groups. The distributions of genotypes were assessed by chi-square tests, whereas calculations were performed for SS, SL and LL genotypes, and for both groups, i.e. patients and controls. Since we did not find any effect of group for the genotype distribution, further analyses were performed without the factor group. Because of the difference between groups regarding age and IQ, we included these variables as covariates into further analyses. In order to investigate the effect of the genotype, we calculated a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) with the covariates IQ and age and the between-subject factor genotype (SS+SL vs. LL) and the independent variables were the IRI scores. The moderation analysis was conducted by means of the SPSS macro tool PROCESS developed by Hayes [63]. The moderation was calculated for the dependent variable “perspective taking” (Y; outcome) and the independent variable CTQ total score (X; predictor) and the moderator (M; susceptibility factor), i.e. the 5-HTTLPR genotype (SS+SL vs. LL), as well as controlled for IQ and age (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of moderation analyses conducted.

The predictor and outcome variables remained constant across calculations whereas the moderator and control variables were exchanged.

| Predictor | Outcome | Moderator | Covariates |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTQ total score |

Perspective taking |

SS+SL vs. LL | age, IQ |

| age, IQ, BDI | |||

| SS vs. SL vs. LL | age, IQ | ||

| age, IQ, BDI | |||

| TA groups: low/low, high/low, high/high | age, IQ | ||

| age, IQ, BDI | |||

| BPD vs. HC | age, IQ |

In order to explore whether the data were in accordance with the differential susceptibility model, we further investigated the association of the predictor (CTQ) and the susceptibility factor, the moderator, by correlation analyses (partial correlations corrected for age and IQ between CTQ total score and the genotype). In addition, we tested for an association of the susceptibility factor with the outcome variable by calculating the correlation of genotype with perspective taking (partial correlation). Finally, we calculated the difference between the slopes of the associations of the moderation analysis between the two genotype groups.

The same analyses for moderating effects and differential susceptibility were also carried out according to differences in transcriptional activity. Additional moderation analyses were performed for the SS, SL and LL Genotypes and for group (BPD vs. HC) as the moderator instead of Genotype. In order to examine the impact of depressivity, we calculated additional moderation analyses with the additional covariate “BDI score” for the moderators “SS+SL vs. LL”, “SS, SL and LL” and transcriptional activity (Table 2). The statistical analyses were performed using the software SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

Results

Questionnaires

Patients differed in age and IQ from control participants and reported more severe experiences of childhood maltreatment as well as more depressive symptoms. Patients reached higher scores in the personal distress score of the IRI, whereas healthy controls scored higher in perspective taking and fantasy scores (Table 3).

Table 3. Psychometric properties of patients with BPD and healthy participants.

Results are reported as mean (M) values and standard deviations (SD). t, p and df of T tests between groups are shown.

| HC | BPD | T Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t | p | df | |

| Age | 24.8 | 5.6 | 27.6 | 7.9 | 3.41 | 0.001 | 253.6 |

| IQ | 108.8 | 17.1 | 101.4 | 16.9 | -3.48 | 0.001 | 254 |

| BDI | 5.9 | 5.9 | 35.3 | 10.3 | 28.33 | <0.001 | 207.4 |

| Childhood Trauma Questionnaire | |||||||

| Total score | 33.6 | 10.7 | 63.7 | 19.5 | 14.11 | <0.001 | 166.3 |

| Emotional abuse | 7.5 | 3.7 | 17.1 | 5.8 | 14.50 | <0.001 | 182.9 |

| Physical abuse | 5.6 | 2.1 | 9.6 | 5.2 | 7.41 | <0.001 | 139.4 |

| Sexual abuse | 5.3 | 1.1 | 9.5 | 5.9 | 7.40 | <0.001 | 115.1 |

| Emotional neglect | 8.5 | 3.9 | 17.2 | 5.7 | 13.21 | <0.001 | 190.7 |

| Physical neglect | 6.2 | 2.1 | 10.3 | 4.3 | 8.85 | <0.001 | 158.2 |

| Interpersonal Reactivity Index | |||||||

| Perspective taking | 19.3 | 4.3 | 13.8 | 5.97 | -8.75 | <0.001 | 221.7 |

| Fantasy | 19.1 | 5.5 | 16.4 | 7.0 | -3.44 | 0.001 | 224.7 |

| Empathic concern | 20.4 | 4.1 | 19.8 | 5.4 | -0.90 | 0.375 | 221.1 |

| Personal distress | 12.8 | 5.1 | 21.6 | 4.2 | 15.03 | <0.001 | 249.4 |

Genotypes

The distributions of genotypes were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in the whole sample (X2 = 0.096; p = 0.757) and were distributed as follows: LL genotype n = 103 (34.2%), SL genotype n = 131 (43.5%); SS genotype n = 45 (15%). When groups were analyzed separately, the distributions were also in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (BPD: X2 = 0.23; p = 0.631; HC: X2 = 0.02; p = 0.887) and there was no difference between allelic frequencies between groups (X2 = 2.84; p = 0.241; df = 2; Table 4). The division into S or LL-carriers resulted in n = 103 LL-carriers and n = 176 S-carriers. Another group formation was based on the rs25531, which offered the opportunity to form groups based on “transcriptional activity”(TA) (Table 4).

Table 4. Overview of 5-HTTLPR genotype distributions in the whole sample, and for patients with BPD and healthy controls (HC) separately.

The first column shows the distribution of the 5-HTTLPR genotypes regarding SS and LL homozygotes and SL heterozygotes. The second column shows the group formation according to the 5-HTTLPR and rs25531 genotypes, which results in high/high, high/low and low/low transcriptional activity groups.

| 5-HTTLPR genotypes | Transcriptional activity groups | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n total | BPD | HC | n total | BPD | HC | |||

| LL | 103 | 59 | 44 | high/ high | 75 | 44 | 31 | |

| LALA | 75 | 44 | 31 | |||||

| SL | 131 | 63 | 68 | |||||

| high/low | 140 | 68 | 72 | |||||

| SS | 45 | 20 | 25 | LALG | 27 | 15 | 12 | |

| LASA | 112 | 52 | 60 | |||||

| LASG | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| low/ low | 63 | 28 | 33 | |||||

| LGLG | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||||

| LGSA | 17 | 10 | 7 | |||||

| SASA | 45 | 20 | 25 | |||||

Questionnaires and genotypes

The MANCOVA for the empathy scores revealed main effects for age and IQ (age F(4, 246) = 3.48, p = 0.009; IQ F(4, 246) = 6.69, p < 0.001), but no main effect of genotype or interaction with genotype.

Moderation analyses

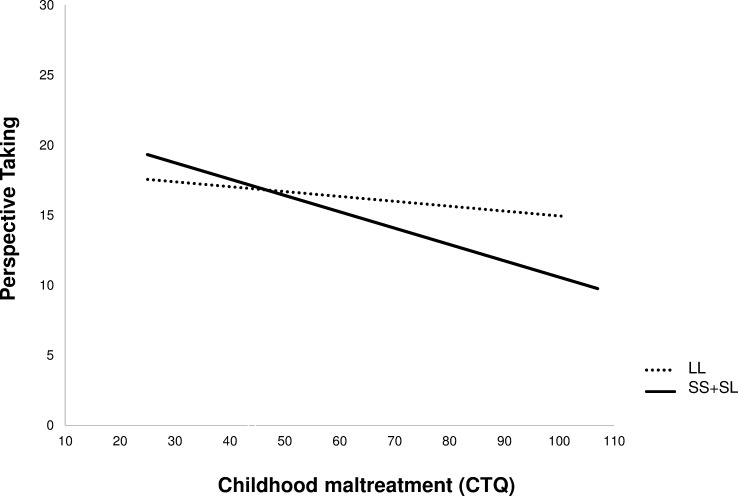

In order to examine the nature of formation of specific social behavior associated with the 5-HTTLPR-genotype, we performed moderation analyses: We calculated the moderation for the independent variable CTQ total score (X; predictor), the dependent variable perspective taking (Y; outcome) and the moderator (M; susceptibility factor) the 5-HTTLPR genotype (SS+SL and LL). The overall model was significant (F(5, 199) = 6.48, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.1401), as was the interaction of CTQ by genotype (Interaction b = -0.0810, t(199) = -2.16, p = 0.032). According to Belsky et al. [64] and our own previous work [65], we investigated whether the data were compatible with the idea of differential susceptibility. Accordingly, we first tested if the predictor was associated with the moderator. Here, no correlation emerged between CTQ score and genotype (r = -0.130, p = 0.062). Second, the susceptibility factor (genotype) did not correlate with the outcome parameter (perspective taking; r = 0.084, p = 0.183). Third, we checked whether the simple slopes of the associations of CTQ with perspective taking differed significantly from zero. The significant difference to zero was only present for the slope of the regression in S-carriers (SS+SL b = -0.109, SE = 0.023, p < 0.001, LL: b = -0.028, SE = 0.031, p = 0.378; Fig 1; Table 5). Forth, we compared the simple slopes and found a significant difference between the groups with t = 3.08, p = 0.002 (SS+SL vs LL). In sum, these analyses are compatible with the “differential susceptibly” model, suggesting that the S-genotype may confer genetic plasticity to environmental variation.

Fig 1.

Comparison of the regression lines of S-carriers (solid line) and LL-carriers (dashed line). The diagram supports the notion of differential susceptibly showing the crossing of the lines with the simple slopes differing between genotypes.

Table 5. Summary of moderation analyses performed for the predictor variable “CTQ” (total score) and the outcome variable “perspective taking”.

The table shows the moderator variables and covariates used and the respective model statistics and interactions between the predictor and moderator variables. The last two columns show tests for differential susceptibility, i.e. differences between slopes and differences from zero.

| Moderator | Covariates | Model | Interaction moderator*CTQ | Differences of slopes from zero | Differences between slopes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS+SL vs. LL | age, IQ | F(5, 199) = 6.48, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.1401 | b = -0.0810, t(199) = -2.16, p = 0.032 | SS+SL b = -0.109, SE = 0.023, p < 0.001 | t = 3.08, p = 0.002 |

| LL: b = -0.028, SE = 0.031, p = 0.378 |

|||||

| age, IQ, BDI | (F(6, 196) = 9.20, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.2198 | b = -0.0857, t(196) = -2.38, p = 0.018 | |||

| SS vs. SL vs. LL | age, IQ | F(5, 199) = 6.77, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.1374 | b = -0.0497, t(199) = -1.84, p = 0.067 | ||

| age, IQ, BDI | b = -0.0479, t(196) = -1.84, p = 0.067 | ||||

| TA groups: low/low, high/low, high/high | age, IQ | F(5, 199) = 6.77, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.1453 | b = -0.0624, t(199) = -2.44, p = 0.015 | high/high: b = -0.0378, SE = 0.0254, p = 0.1389 | high/high vs. low/low: t = 3.30, p = 0.001 |

| high/low: b = -0.0808, SE = 0.0189, p < 0.001; | high/low vs. low/low: t = 2.00, p = 0.047 | ||||

| low/low: b = -0.1237, SE = 0.0262, p < 0.001 | high/high vs. high/low group t = 2.01, p = 0.046 | ||||

| age, IQ, BDI | F(6, 196) = 9.43, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.2239 | b = -0.0649, t(196) = -2.63, p = 0.009 | |||

| BPD vs. HC | age, IQ | F(5, 199) = 11.71, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.2272 | b = 0.0437, t(199) = 0.81, p = 0.419 | ||

We also calculated a moderation analysis for the three genotypes, SS, SL and LL. Here, the model was highly significant (F(5, 199) = 6.77, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.1374). However, the interaction of CTQ by genotype showed only a tendency toward statistical significance (Interaction b = -0.0497, t(199) = -1.84, p = 0.067), which could be related to the relatively small sample in the SS group (for comparison see Table 4).

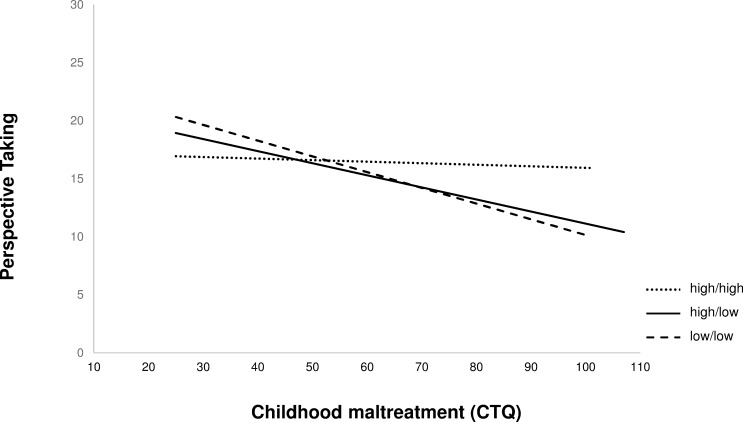

In order to investigate the impact of the rs25531 within the 5-HTTLPR we built “transcriptional activity” (TA) groups (Table 4). We re-calculated the moderation analysis for the independent variable CTQ total score (X; predictor), the dependent variable perspective taking (Y; outcome) and the TA group as the moderator (M; low/low, high/low and high/high) The overall model was significant with (F(5, 199) = 6.77, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.1453), as was the interaction of CTQ by genotype (Interaction b = -0.0624, t(199) = -2.44, p = 0.015). Moreover, no correlations were found between CTQ score and TA group (r = -0.108, p = 0.123) or between perspective taking and TA group (r = 0.094, p = 0.138). Next, the analysis of slopes showed that only the slopes of TA groups high/low and low/low differed significantly from 0 (high/high: b = -0.0378, SE = 0.0254, p = 0.1389, high/low: b = -0.0808, SE = 0.0189, p < 0.001; low/low: b = -0.1237, SE = 0.0262, p < 0.001). The comparisons of slopes revealed that the slopes of the regression lines of high/high and high/low groups were significantly different from the slope of the low/low group (high/high vs. low/low: t = 3.30, p = 0.001; high/low vs. low/low: t = 2.00, p = 0.047). The slope of high/high also differed from the slope of high/low group (t = 2.01, p = 0.046; see Fig 2). These results confirm the differential susceptibility model and extend our results to the level of transcriptional activity.

Fig 2.

Graphical representation of the association of childhood maltreatment (CTQ) and perspective taking ability in high/high (small dashed line), high/low (solid line) and low/low (longer dashed line) transcriptional activity groups based on 5-HTTLPR and rs25531.

We further aimed to examine whether the association of childhood trauma with perspective talking was related to diagnosis. Therefore, we performed the same moderation analysis, but tested the factor “group” (BPD vs. HC) as the moderator. The model was also significant (F(5, 199) = 11.71, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.2272), but the interaction of CTQ by group was not (Interaction b = 0.0437, t(199) = 0.81, p = 0.419), suggesting that a diagnosis of BPD was not the sole factor impacting on the association of childhood trauma with empathic perspective taking. Since depressivity is highly prevalent among individuals suffering from BPD, we repeated the moderation analyses and included also the BDI score as a covariate into the calculation. Here, the same results were obtained as in the previous analyses without the covariate BDI (see Table 5).

Discussion

In the present study we aimed to investigate the role of the 5-HTLLPR concerning the association between childhood trauma and trait empathy. The moderation analysis and tests for differential susceptibility showed that the influence of childhood maltreatment on empathic perspective-taking seemed to be specific for S-carriers, suggesting that this allele confers genetic plasticity to environmental variation. Put differently, in people with at least one S-allele childhood maltreatment seems to be related to reduced perspective taking, whereas the absence of childhood maltreatment is associated with well-preserved perspective taking capacities. As noted by Belsky et al. [66], the mere absence of maltreatment is not equivalent to high-quality parenting. When applying this idea to the present findings, it can tentatively be hypothesized that emotional warmth and availability during early development may lead to even better-than-average perspective-taking abilities (in this case, the slopes of the regression lines shown in Fig 1 may diverge to a greater extent if extrapolated to the left). In contrast, LL-carriers seemed to be unresponsive to childhood adversity in terms of consequences for trait empathy. The relation of trauma and reduced perspective-taking was already shown in previous studies and shown to be related to alexithymia and stress [14]. A possible explanation for reduced perspective taking in S-allele carriers exposed to childhood trauma may be the negative effect of stress, induced by the traumatic history and the following consequences (e.g. unsuccessful coping strategies), on the development of cognitive empathic perspective taking. Our findings are consistent with previous studies reporting that S-carriers showed increased attention towards emotional stimuli and especially negative stimuli when compared to L-carriers [24, 28, 67]. Owens and colleagues further reported that S-homozygotes (adolescents) were impaired in emotion recognition of negative and neutral stimuli and had more difficulties in responding to ambiguous negative feedback [67].

When looking at prosocial behavior, Stoltenberg and colleagues reported that S-allele carriers scored higher in social anxiety and lower in prosocial behavior [62]. Moreover, lower levels of sensitive responsiveness to their own toddlers were found in parents with the SS-allele [42]. Unfortunately, these studies did not include measures of the participants’ own experiences during childhood. Moreover, Gyurak et al. [27] found that SS-homozygotes showed greater levels of emotional reactivity accompanied by an increased psychosocial stress response. Similarly, another group reported that SS-carrier showed the greatest increase in cortisol levels following the Trier Social Stress Test. In addition, the association between genotype and cortisol reactivity was strongest when receiving negative feedback. The authors concluded that carrying the SS-allele may make the individuals more vulnerable to stressful life events, which leads to a greater risk for the severe psychological and physical health consequences associated with heightened cortisol exposure [29]. In support of this assumption Gotlib and colleagues examined the association between stress, 5-HTTLPR and depression in children. They demonstrated that girls, who were homozygous for the S-allele showed higher and prolonged cortisol levels in response to a stressor (mental arithmetic and Ewart Social Competence Interview) compared to L-allele carrying girls [68]. Additionally, it was shown that acute stress exposure led to a significant impairment in the inhibition of negative affective information only in SS-carriers. The authors concluded that a cognitive-attentional bias for negative emotional information may make an individual more vulnerable for stress-induced depressive symptoms [69]. With regard to our study, increased stress-reactivity and altered emotion processing in S-allele carriers may cause, together with the experiences of childhood adversity, impairment in taking the perspective of another individual. With regard to depression, the exact role of the 5-HTTLPR in the development of depression is unclear. This was shown by recent meta-analyses, which reported an association of stressful life events and depression in SS-homozygotes or S-carrying heterozygotes [45, 46], whereas other studies failed to determine such an association [31, 47]. For example, Culverhouse and colleagues found a significant main effect of sex and life stressor (high risk factor for depression), but they did not found an effect of genotype on the association of stress and depression, even if they included only studies with large sample sizes [47]. The authors concluded that, if any interaction would exist, it would not be a generalizable effect, only detectable in limited situations and of modest effect size. In our study, the inclusion of depressivity as a covariate did not affect the interaction, which suggests that the effect on perspective taking was not due to depressive symptoms. This further implies that our study does also not support the link between 5-HTTLPR, stress and depression. Eventually, the 5-HTTLPR, together with stress, may induce stress and emotion processing impairments (as described above), which lead only in a subset of individuals to the development of depression. This subset may bear additional risks, which are currently not in the focus of interaction studies. One potential factor could be the transcriptional activity of the serotonin transporter gene, which could be altered by epigenetic processes or other SNPs, as for example the rs25531 [35, 36, 70].

In our study, additional analyses according to the transcriptional activity of the serotonin transporter gene revealed similar results, i.e. differential susceptibility in the low/low and high/low groups akin to what emerged in S-allele carriers of the 5-HTTLPR. This finding is in accordance with previous studies, which also did not report modulation of the associations between 5-HTTLPR and phenotypes by the rs25531 [37, 71]. Interestingly, however, we found a graded effect of the transcriptional activity, indicating that the lower the activity of the serotonin transporter gene, the greater the genetic plasticity with regard to the effect of childhood adversity on empathic perspective-taking. When calculating the additional moderation analysis with the three 5-HTTLPR groups, SS, SL and LL, the interaction failed to reach significance. This could be due to a lack of statistical power due to the small sample size in the SS-group, or be related to the fact that the exact genotype may not be as relevant as the existence of at least one “risk allele”. In any event, even though the statistical power for detecting significant interaction effects was sufficiently large with α = 0.75, it is warranted to replicate the study in an independent, and preferably larger, sample.

Our study has several other limitations. For one, since we included only female participants, our conclusions cannot be generalized for males. Second, the clinical and the non-clinical group differed significantly with regard to the experience of childhood trauma. However, since our main interest pertained to the influence of childhood adversity on trait empathy and its moderation by genotype, we were much less concerned with the presence or absence of specific effects of a diagnosis of BPD. In support of this idea, the moderation analysis with the moderator group (BPD/HC) did not show a specific effect of BPD on the association of childhood trauma with perspective taking. Third, as already pointed out, for a more substantial corroboration of the differential susceptibility hypotheses, it would have been desirable to expand measures of adversity in the direction of parental warmth and caregiver availability to better reflect the whole spectrum ranging from superior to poor environmental conditions [66]. Forth, since we assessed only adversity during childhood, we were unable to exclude confounding effects of recent negative life events, which may also have impact on present social behavior. Thus, future studies may investigate childhood, as well as recent adversity, in order to define the concrete contribution of these factors on social behavior and the development of psychopathology.

Together, the present study is the first to show that the association of empathic perspective-taking with childhood adversity is moderated by the 5-HTTLPR, and the transcriptional activity of the serotonin transporter gene. It therefore corroborates previous findings suggesting that the S-allele of the 5-HTTLPR conveys differential susceptibility to environmental cues, as does low transcriptional activity.

Supporting information

(PDF)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Gonzalez-Liencres C, Shamay-Tsoory SG, Brüne M. Towards a neuroscience of empathy: ontogeny, phylogeny, brain mechanisms, context and psychopathology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2013; 37(8):1537–48. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singer T. The neuronal basis and ontogeny of empathy and mind reading: review of literature and implications for future research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2006; 30(6):855–63. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singer T, Lamm C. The social neuroscience of empathy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2009; 1156:81–96. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04418.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dziobek I, Rogers K, Fleck S, Bahnemann M, Heekeren HR, Wolf OT et al. Dissociation of cognitive and emotional empathy in adults with Asperger syndrome using the Multifaceted Empathy Test (MET). J Autism Dev Disord 2008; 38(3):464–73. 10.1007/s10803-007-0486-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith A. The empathy imbalance hypothesis of autism: a theoretical approach to cognitive and emotional empathy in autistic development. the Psychological record 2009; 59(3):489–510. Available from: URL: 10.1007/BF03395675. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bora E, Gokcen S, Veznedaroglu B. Empathic abilities in people with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 2008; 160(1):23–9. 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haker H, Rössler W. Empathy in schizophrenia: impaired resonance. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2009; 259(6):352–61. 10.1007/s00406-009-0007-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blair RJR. Responding to the emotions of others: dissociating forms of empathy through the study of typical and psychiatric populations. Conscious Cogn 2005; 14(4):698–718. 10.1016/j.concog.2005.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dinsdale N, Crespi BJ. The borderline empathy paradox: evidence and conceptual models for empathic enhancements in borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord 2013; 27(2):172–95. 10.1521/pedi.2013.27.2.172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harari H, Shamay-Tsoory SG, Ravid M, Levkovitz Y. Double dissociation between cognitive and affective empathy in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 2010; 175(3):277–9. 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niedtfeld I. Experimental investigation of cognitive and affective empathy in borderline personality disorder: Effects of ambiguity in multimodal social information processing. Psychiatry Res 2017; 253:58–63. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Preissler S, Dziobek I, Ritter K, Heekeren HR, Roepke S. Social Cognition in Borderline Personality Disorder: Evidence for Disturbed Recognition of the Emotions, Thoughts, and Intentions of others. Front Behav Neurosci 2010; 4:182 10.3389/fnbeh.2010.00182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wingenfeld K, Duesenberg M, Fleischer J, Roepke S, Dziobek I, Otte C et al. Psychosocial stress differentially affects emotional empathy in women with borderline personality disorder and healthy controls. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2018; 137(3):206–15. 10.1111/acps.12856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flasbeck V, Enzi B, Brüne M. Altered Empathy for Psychological and Physical Pain in Borderline Personality Disorder. J Pers Disord 2017; 31(5):689–708. 10.1521/pedi_2017_31_276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carver CS, Johnson SL, Joormann J. Two-Mode Models of Self-Regulation as a Tool for Conceptualizing Effects of the Serotonin System in Normal Behavior and Diverse Disorders. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2009; 18(4):195–9. 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01635.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spoont MR. Modulatory role of serotonin in neural information processing: implications for human psychopathology. Psychol Bull 1992; 112(2):330–50. 10.1037/0033-2909.112.2.330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett AJ, Lesch KP, Heils A, Long JC, Lorenz JG, Shoaf SE et al. Early experience and serotonin transporter gene variation interact to influence primate CNS function. Mol Psychiatry 2002; 7(1):118–22. 10.1038/sj.mp.4000949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Champoux M, Bennett A, Shannon C, Higley JD, Lesch KP, Suomi SJ. Serotonin transporter gene polymorphism, differential early rearing, and behavior in rhesus monkey neonates. Mol Psychiatry 2002; 7(10):1058–63. 10.1038/sj.mp.4001157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Tessitore A, Kolachana B, Fera F, Goldman D et al. Serotonin transporter genetic variation and the response of the human amygdala. Science 2002; 297(5580):400–3. 10.1126/science.1071829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kenna GA, Roder-Hanna N, Leggio L, Zywiak WH, Clifford J, Edwards S et al. Association of the 5-HTT gene-linked promoter region (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism with psychiatric disorders: review of psychopathology and pharmacotherapy. Pharmgenomics Pers Med 2012; 5:19–35. 10.2147/PGPM.S23462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S et al. Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science 1996; 274(5292):1527–31. 10.1126/science.274.5292.1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lesch KP, Mössner R. Genetically driven variation in serotonin uptake: is there a link to affective spectrum, neurodevelopmental, and neurodegenerative disorders? Biol Psychiatry 1998; 44(3):179–92. 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00121-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner S, Baskaya O, Lieb K, Dahmen N, Tadic A. The 5-HTTLPR polymorphism modulates the association of serious life events (SLE) and impulsivity in patients with Borderline Personality Disorder. J Psychiatr Res 2009; 43(13):1067–72. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beevers CG, Wells TT, Ellis AJ, McGeary JE. Association of the serotonin transporter gene promoter region (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism with biased attention for emotional stimuli. J Abnorm Psychol 2009; 118(3):670–81. 10.1037/a0016198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beevers CG, Marti CN, Lee H-J, Stote DL, Ferrell RE, Hariri AR et al. Associations between serotonin transporter gene promoter region (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism and gaze bias for emotional information. J Abnorm Psychol 2011; 120(1):187–97. 10.1037/a0022125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fox E, Ridgewell A, Ashwin C. Looking on the bright side: biased attention and the human serotonin transporter gene. Proc Biol Sci 2009; 276(1663):1747–51. 10.1098/rspb.2008.1788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gyurak A, Haase CM, Sze J, Goodkind MS, Coppola G, Lane J et al. The effect of the serotonin transporter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) on empathic and self-conscious emotional reactivity. Emotion 2013; 13(1):25–35. 10.1037/a0029616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osinsky R, Reuter M, Kupper Y, Schmitz A, Kozyra E, Alexander N et al. Variation in the serotonin transporter gene modulates selective attention to threat. Emotion 2008; 8(4):584–8. 10.1037/a0012826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Way BM, Taylor SE. The serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism is associated with cortisol response to psychosocial stress. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 67(5):487–92. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amad A, Ramoz N, Thomas P, Jardri R, Gorwood P. Genetics of borderline personality disorder: systematic review and proposal of an integrative model. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Risch N, Herrell R, Lehner T, Liang K-Y, Eaves L, Hoh J et al. Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events, and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2009; 301(23):2462–71. 10.1001/jama.2009.878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Serretti A, Cristina S, Lilli R, Cusin C, Lattuada E, Lorenzi C et al. Family-based association study of 5-HTTLPR, TPH, MAO-A, and DRD4 polymorphisms in mood disorders. Am J Med Genet 2002; 114(4):361–9. 10.1002/ajmg.10356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noskova T, Pivac N, Nedic G, Kazantseva A, Gaysina D, Faskhutdinova G et al. Ethnic differences in the serotonin transporter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) in several European populations. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 2008; 32(7):1735–9. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie P, Kranzler HR, Poling J, Stein MB, Anton RF, Brady K et al. Interactive Effect of Stressful Life Events and the Serotonin Transporter 5-HTTLPR Genotype on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Diagnosis in 2 Independent Populations. PSYCH 2009; 66(11):1201–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu X, Oroszi G, Chun J, Smith TL, Goldman D, Schuckit MA. An expanded evaluation of the relationship of four alleles to the level of response to alcohol and the alcoholism risk. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2005; 29(1):8–16. 10.1097/01.alc.0000150008.68473.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wendland JR, Martin BJ, Kruse MR, Lesch K-P, Murphy DL. Simultaneous genotyping of four functional loci of human SLC6A4, with a reappraisal of 5-HTTLPR and rs25531. Mol Psychiatry 2006; 11(3):224–6. 10.1038/sj.mp.4001789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wüst S, Kumsta R, Treutlein J, Frank J, Entringer S, Schulze TG et al. Sex-specific association between the 5-HTT gene-linked polymorphic region and basal cortisol secretion. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009; 34(7):972–82. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kohen R, Cain KC, Mitchell PH, Becker K, Buzaitis A, Millard SP et al. Association of Serotonin Transporter Gene Polymorphisms With Poststroke Depression. PSYCH 2008; 65(11):1296–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brüne M, Belsky J, Fabrega H, Feierman HR, Gilbert P, Glantz K et al. The crisis of psychiatry—insights and prospects from evolutionary theory. World Psychiatry 2012; 11(1):55–7. 10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monroe SM, Simons AD. Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: implications for the depressive disorders. Psychol Bull 1991; 110(3):406–25. 10.1037/0033-2909.110.3.406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boyce WT, Ellis BJ. Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary-developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity. Dev Psychopathol 2005; 17(2):271–301. 10.1017/s0954579405050145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH. Oxytocin receptor (OXTR) and serotonin transporter (5-HTT) genes associated with observed parenting. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2008; 3(2):128–34. 10.1093/scan/nsn004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Belsky J, Pluess M. Beyond diathesis stress: differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychol Bull 2009; 135(6):885–908. 10.1037/a0017376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science 2003; 301(5631):386–9. 10.1126/science.1083968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clarke H, Flint J, Attwood AS, Munafo MR. Association of the 5- HTTLPR genotype and unipolar depression: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2010; 40(11):1767–78. 10.1017/S0033291710000516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karg K, Burmeister M, Shedden K, Sen S. The serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR), stress, and depression meta-analysis revisited: evidence of genetic moderation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68(5):444–54. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Culverhouse RC, Saccone NL, Horton AC, Ma Y, Anstey KJ, Banaschewski T et al. Collaborative meta-analysis finds no evidence of a strong interaction between stress and 5-HTTLPR genotype contributing to the development of depression. Mol Psychiatry 2018; 23(1):133–42. 10.1038/mp.2017.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pluess M, Belsky J, Way BM, Taylor SE. 5-HTTLPR moderates effects of current life events on neuroticism: differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2010; 34(6):1070–4. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.05.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuepper Y, Wielpuetz C, Alexander N, Mueller E, Grant P, Hennig J. 5-HTTLPR S-allele: a genetic plasticity factor regarding the effects of life events on personality? Genes Brain Behav 2012; 11(6):643–50. 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2012.00783.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®): American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lehrl S, Merz J, Burkhard G, Fischer S. Mehrfachwahl-Wortschatz-Intelligenztest (MWT-A). Manual. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davis MH. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1983; 44(1):113–26. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paulus C. Saarbrücker Persönlichkeits-Fragebogen (SPF)[[Saarbrücken personality questionnaire]. Based on the interpersonal reactivity index (IRI) including new items (V3. 0); 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wolf OT, Schulte JM, Drimalla H, Hamacher-Dang TC, Knoch D, Dziobek I. Enhanced emotional empathy after psychosocial stress in young healthy men. Stress 2015; 18(6):631–7. 10.3109/10253890.2015.1078787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nomura K, Akai S. Empathy with fictional stories: reconsideration of the fantasy scale of the interpersonal reactivity index. Psychol Rep 2012; 110(1):304–14. 10.2466/02.07.09.11.PR0.110.1.304-314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klinitzke G, Romppel M, Häuser W, Brähler E, Glaesmer H. Die deutsche Version des Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ)–psychometrische Eigenschaften in einer bevölkerungsrepräsentativen Stichprobe. Psychother Psych Med 2012; 62(02):47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–71. 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res 1988; 16(3):1215 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang A-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods 2009; 41(4):1149–60. 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Greenberg BD, Li Q, Lucas FR, Hu S, Sirota LA, Benjamin J et al. Association between the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism and personality traits in a primarily female population sample. Am J Med Genet 2000; 96(2):202–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pezawas L, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Drabant EM, Verchinski BA, Munoz KE, Kolachana BS et al. 5-HTTLPR polymorphism impacts human cingulate-amygdala interactions: a genetic susceptibility mechanism for depression. Nat Neurosci 2005; 8(6):828–34. 10.1038/nn1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stoltenberg SF, Christ CC, Carlo G. Afraid to help: social anxiety partially mediates the association between 5-HTTLPR triallelic genotype and prosocial behavior. Soc Neurosci 2013; 8(5):400–6. 10.1080/17470919.2013.807874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach New York: The Guilford Press; 2013. (Methodology in the social sciences). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH. For Better and For Worse: Differential Susceptibility to Environmental Influences. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2007; 16(6):300–4. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Flasbeck V, Moser D, Kumsta R, Brüne M. The OXTR Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism rs53576 Moderates the Impact of Childhood Maltreatment on Empathy for Social Pain in Female Participants: Evidence for Differential Susceptibility. Front Psychiatry 2018; 9:359 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Belsky J, Jonassaint C, Pluess M, Stanton M, Brummett B, Williams R. Vulnerability genes or plasticity genes? Mol Psychiatry 2009; 14(8):746–54. 10.1038/mp.2009.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Owens M, Goodyer IM, Wilkinson P, Bhardwaj A, Abbott R, Croudace T et al. 5-HTTLPR and early childhood adversities moderate cognitive and emotional processing in adolescence. PLoS One 2012; 7(11):e48482 10.1371/journal.pone.0048482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gotlib IH, Joormann J, Minor KL, Hallmayer J. HPA axis reactivity: a mechanism underlying the associations among 5-HTTLPR, stress, and depression. Biol Psychiatry 2008; 63(9):847–51. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Markus CR, Raedt R de. Differential effects of 5-HTTLPR genotypes on inhibition of negative emotional information following acute stress exposure and tryptophan challenge. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011; 36(4):819–26. 10.1038/npp.2010.221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Booij L, Wang D, Lévesque ML, Tremblay RE, Szyf M. Looking beyond the DNA sequence: the relevance of DNA methylation processes for the stress–diathesis model of depression. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2013; 368(1615):20120251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Steiger H, Richardson J, Joober R, Gauvin L, Israel M, Bruce KR et al. The 5HTTLPR polymorphism, prior maltreatment and dramatic-erratic personality manifestations in women with bulimic syndromes. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2007; 32(5):354–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]