Abstract

Background

The 'Theory of Mind' (ToM) model suggests that people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have a profound difficulty understanding the minds of other people ‐ their emotions, feelings, beliefs, and thoughts. As an explanation for some of the characteristic social and communication behaviours of people with ASD, this model has had a significant influence on research and practice. It implies that successful interventions to teach ToM could, in turn, have far‐reaching effects on behaviours and outcome.

Objectives

To review the efficacy of interventions based on the ToM model for individuals with ASD.

Search methods

In August 2013 we searched CENTRAL, Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, ERIC, Social Services Abstracts, AutismData, and two trials registers. We also searched the reference lists of relevant papers, contacted authors who work in this field, and handsearched a number of journals.

Selection criteria

Review studies were selected on the basis that they reported on an applicable intervention (linked to ToM in one of four clearly‐defined ways), presented new randomised controlled trial data, and participants had a confirmed diagnosis of an autism spectrum disorder. Studies were selected by two review authors independently and a third author arbitrated when necessary.

Data collection and analysis

Risk of bias was evaluated and data were extracted by two review authors independently; a third author arbitrated when necessary. Most studies were not eligible for meta‐analysis, the principal reason being mis‐matching methodologies and outcome measures. Three small meta‐analyses were carried out.

Main results

Twenty‐two randomised trials were included in the review (N = 695). Studies were highly variable in their country of origin, sample size, participant age, intervention delivery type, and outcome measures. Risk of bias was variable across categories. There were very few studies for which there was adequate blinding of participants and personnel, and some were also judged at high risk of bias in blinding of outcome assessors. There was also evidence of some bias in sequence generation and allocation concealment. Not all studies reported data that fell within the pre‐defined primary outcome categories for the review, instead many studies reported measures which were intervention‐specific (e.g. emotion recognition). The wide range of measures used within each outcome category and the mixed results from these measures introduced further complexity when interpreting results.

Studies were grouped into four main categories according to intervention target/primary outcome measure. These were: emotion recognition studies, joint attention and social communication studies, imitation studies, and studies teaching ToM itself. Within the first two of these categories, a sub‐set of studies were deemed suitable for meta‐analysis for a limited number of key outcomes.

There was very low quality evidence of a positive effect on measures of communication based on individual results from three studies. There was low quality evidence from 11 studies reporting mixed results of interventions on measures of social interaction, very low quality evidence from four studies reporting mixed results on measures of general communication, and very low quality evidence from four studies reporting mixed results on measures of ToM ability.

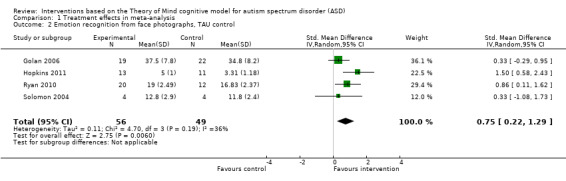

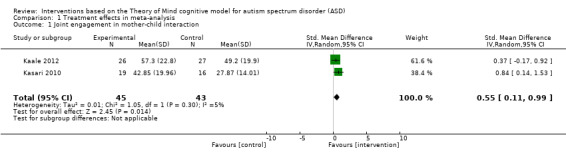

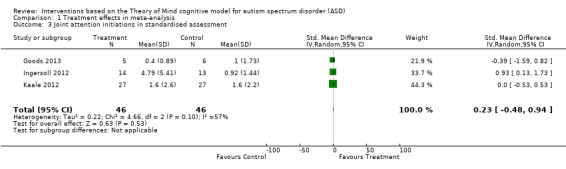

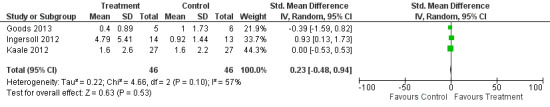

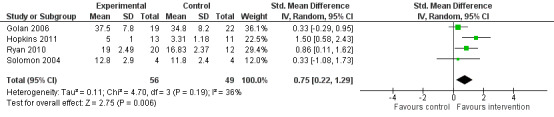

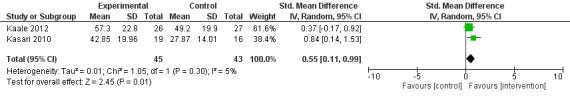

The meta‐analysis results we were able to generate showed that interventions targeting emotion recognition across age groups and working with people within the average range of intellectual ability had a positive effect on the target skill, measured by a test using photographs of faces (mean increase of 0.75 points, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.22 to 1.29 points, Z = 2.75, P < 0.006, four studies, N = 105). Therapist‐led joint attention interventions can promote production of more joint attention behaviours within adult‐child interaction (mean increase of 0.55 points, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.99 points, Z = 2.45, P value = 0.01, two studies, N = 88). Further analysis undermines this conclusion somewhat by demonstrating that there was no clear evidence that intervention can have an effect on joint attention initiations as measured using a standardised assessment tool (mean increase of 0.23 points, 95% CI ‐0.48 to 0.94 points, Z = 0.63, P value = 0.53, three studies, N = 92). No adverse effects were apparent.

Authors' conclusions

While there is some evidence that ToM, or a precursor skill, can be taught to people with ASD, there is little evidence of maintenance of that skill, generalisation to other settings, or developmental effects on related skills. Furthermore, inconsistency in findings and measurement means that evidence has been graded of 'very low' or 'low' quality and we cannot be confident that suggestions of positive effects will be sustained as high‐quality evidence accumulates. Further longitudinal designs and larger samples are needed to help elucidate both the efficacy of ToM‐linked interventions and the explanatory value of the ToM model itself. It is possible that the continuing refinement of the ToM model will lead to better interventions which have a greater impact on development than those investigated to date.

Keywords: Humans; Theory of Mind; Child Development Disorders, Pervasive; Child Development Disorders, Pervasive/psychology; Child Development Disorders, Pervasive/therapy; Emotions; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

A review of evidence on the use of interventions for people with autism spectrum disorder, based on the psychological model 'Theory of Mind'

Background

The 'Theory of Mind' model suggests that people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have a profound difficulty understanding the minds of other people, their emotions, feelings, beliefs, and thoughts. It has been proposed that this may underlie many of the other difficulties experienced by people with ASD, including social and communication problems, and some challenging behaviours. Therefore, a number of studies have attempted to teach theory of mind and related skills to people with ASD.

Review question

This review aimed to explore whether a) it is possible to teach theory of mind skills to people with autism and b) whether or not this evidence supports the theory of mind model. Having a 'theory of mind' may depend on developing related basic skills, including joint attention (sharing a focus of interest with another person), recognising other people's emotions from faces or stories, and imitating other people. Therefore, we included intervention studies that taught not just theory of mind itself, but also related skills.

Study characteristics

We found 22 research studies involving 695 participants, which reported on the efficacy of interventions related to theory of mind. The evidence is current to 7th August 2013.

Key results and the quality of the evidence

Despite all studies using a high‐quality basic methodology (the randomised controlled trial), there was concern over poor study design and reporting in some aspects. While there is some evidence that theory of mind, or related skills, can be taught to people with ASD, there is currently poor quality evidence that these skills can be maintained, generalised to other settings, or that teaching theory of mind has an impact on developmentally‐linked abilities. For example, it was rare for a taught skill to generalise to a new context, such as sharing attention with a new adult who was not the therapist during the intervention. New skills were not necessarily maintained over time. This evidence could imply that the theory of mind model has little relevance for educational and clinical practice in ASD. Further research using longitudinal methods, better outcome measures, and higher standards of reporting is needed to throw light on the issues. This is particularly important as the specific details of the theory of mind model continue to evolve.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Theory of Mind based interventions compared with wait‐list or treatment‐as‐usual control for autism spectrum disorder. | |||||

|

Patient or population: People with autism spectrum disorder Settings: Schools, home and clinical settings Intervention: Based on the Theory of Mind theoretical model of autism Comparison: Most studies incorporate an 'empty' control such as treatment‐as‐usual or wait‐list | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| [Control] | [Intervention] | ||||

| Symptom Level: Communication Various measures, including: Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) Conversation Skills Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) (level of eye‐contact) |

See 'Corresponding Risk' | Wong 2010 and Young 2012 report positive effects of intervention on symptom level in the communication domain, while Hadwin 1996 found no effect on conversational skills (this specific outcome is reported in Hadwin 1997) | ADOS: n = 17 (Wong 2010) Conversation: n = 30 (Hadwin 1996) SCQ: n = 25 (Young 2012) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low [1] | Three included studies report outcomes in this area of clinical relevance. Each one uses a different assessment to capture change in this domain. One study uses an unstandardised measure, though it is designed to capture change over time Hadwin 1996). The other two studies use standardised measures of communication skills but neither of these were designed to capture change over time nor to be used as intervention outcome measures. |

| Symptom Level: Social Interaction Various measures, including: Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) Communication and Symbolic Behaviour Scale (CSBS) Early Social Communication Scales (ESCS) PDD‐BI social approach subscale Precursors of Joint Attention Measure Social (PJAM) Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) Social Emotional Scale (SES) (Bayley‐III) Social Skills Rating System (SSRS) Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales (socialisation) (VABS) and Other social interaction (SI) observations |

See 'Corresponding Risk' | Fewer than half of the relevant included studies report positive effects of intervention on symptom level in the social interaction domain (Ingersoll 2012; Kasari 2006; Hopkins 2011; Landa 2011; Wong 2010). In addition some studies report mixed findings across methods. For example, Goods 2013 and Kaale 2012 report some positive effects measured in observations, but null findings from the ESCS. Conversely Kim 2009 (outcomes reported in Kim 2008) and Wong 2013 find significant effects measured by the ESCS but not all other measures. In the case of Wong 2013 this is further complicated by a mixed output from the ESCS where a significant effect is found for one scored item but not another. Similar findings are reported by Schertz 2013 and Kasari 2010 who find positive effects of intervention on some observed behaviours but not others. Both studies which report the impact of an emotion recognition intervention on generalised social skills do not find significant effects on their chosen outcomes (Williams 2012; Young 2012) |

ADOS: n = 17 (Wong 2010) CSBS: n = 48 (Landa 2011) ESCS: n = 200 (Goods 2013; Ingersoll 2012; Kaale 2012; Kasari 2006; Kim 2009; Wong 2013) PDD‐BI: n = 10 (Kim 2009) PJAM: n = 23 (Schertz 2013) SCQ: n = 25 (Young 2012) SES Bayley: n = 27 (Ingersoll 2012) SSRS: n = 49 (Hopkins 2011) VABS Socialisation: n = 55 (Williams 2012) Other SI: n = 175 (Kasari 2006, Kim 2009; Kaale 2012; Kasari 2010; Goods 2013) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low [2] | Here we include both standardised assessments and direct observations of social behaviours. Eleven included studies report outcomes in this area of clinical relevance. There is wide variety in the choice of assessments to capture change in this domain, though most are based on standardised assessments and are often designed to capture change over time. |

| General Communication Ability (e.g. vocabulary) Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL) Reynell Developmental Language Scales |

See 'Corresponding Risk' | Schertz 2013 reports significant intervention effects on receptive language and a non‐significant but moderate sized effect (d = 0.78) for expressive language scores. At a one‐year follow‐up Kasari 2006 likewise report intervention effects on expressive language, which were significantly greater for the joint attention intervention compared with both control group and symbolic play interventions. However these effects on expressive vocabulary were not sustained four years later (Kasari 2012b). In addition, a methodologically strong study (Landa 2011) reports no effects on expressive language. | MSEL expressive: n = 71 (Landa 2011, Schertz 2013) MSEL receptive: n = 23 (Schertz 2013) Reynell: n = 58 (Kasari 2006) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low [3] | Though this has commonly been used as an outcome measure in generalised social skills interventions for children with ASD, only three of the studies included in this review report a general communication ability outcome measure. |

| Theory of Mind ability Various measures, including: False‐belief tasks Happe's Strange Stories Faux‐Pas Recognition Test NEPSY‐II ToM tasks The ToM Test |

See 'Corresponding Risk' | Two studies report some positive effects of intervention on ToM ability (Begeer 2011; Fisher 2005) one reports no impact on directly‐assessed ToM ability (Solomon 2004) and one reports a reduction at follow‐up in ToM ability for the intervention group specifically (Williams 2012). | False belief: n = 27 (Fisher 2005) Happe SS, & Faux‐Pas RT: n = 18 (Solomon 2004) NEPSY: n = 55 (Williams 2012) ToM Test: n = 36 (Begeer 2011) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝

very low [1] |

Four included studies report outcomes in this area of principally theoretical relevance. There is wide variety in the choice of assessments to capture change in this domain, though most are based on standardised assessments and are closely linked to the intervention target skill. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1. Risk of bias (‐1); inconsistency (‐2): Since the studies included here are of variable methodological quality and report mixed findings this evidence is considered to be of Very Low quality.

2. Risk of bias (‐1); inconsistency (‐1): The studies included here are of variable methodological quality and report mixed findings from a wide variety of measures. There is a collection of studies reporting on the ESCS (some of which are summarised in Analysis 1.1), but within this group findings are once again mixed. Indeed, even within a single study and measure there may be inconsistency in evidence for intervention efficacy. It is therefore impossible to be confident about the impact of Theory of Mind interventions on social interaction domain symptom level and the evidence quality is rated as Low.

3. Risk of bias (‐1); inconsistency (‐1); low sample size (‐1): These mixed outcomes from only a handful of studies must be judged of Very Low Quality until they can be resolved by additional high‐quality evidence.

It is challenging to divide communication and social interaction for measures which tap into both of these qualities. However for the purposes of this table, we have identified measures which are based on observation of an interpersonal interaction as falling into the Social Interaction Domain.

A number of included studies report on measures of emotion recognition and imitation skill. While these are suitable outcomes for the respective interventions, and highly associated with ASD profiles, these cannot be categorised into the domains for this Summary of Findings table, and therefore are not addressed here.

Background

Description of the condition

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is an umbrella term used to describe all people diagnosed as showing symptoms within two core criteria: communication and social deficits, and fixed or repetitive behaviours (APA 2013). The ASD label replaces former sub‐types, including autism, pervasive developmental disorder – not otherwise specified (PDD‐NOS), and Asperger’s syndrome (AS) (APA 1994). Likewise, the single communication and social interaction cluster is derived from what was originally two separate domains of impairment in communication and social interaction (APA 1994). These difficulties often make it very hard for people with ASD to be successful members of society and can present very serious challenges to parents, teachers, and other professionals.

Prevalence estimates of ASD diagnosis in children have been rising significantly in recent years with an authoritative systematic review estimating global prevalence of pervasive developmental disorders at 62 per 10,000 and autistic disorder at 17 per 10,000 (Elsabbagh 2012). Figures may be higher in more developed countries (e.g. Baird 2006). This represents a more‐than‐threefold increase on previously published figures, which estimated autism prevalence at about 5 per 10,000 (Fombonne 2001). While there are methodological differences between prevalence studies, the rising prevalence of ASD has been well‐documented across Western countries, including Europe, Australia, and the USA (e.g. Yeargin‐Allsopp 2003; Williams 2006; Atladottir 2007; Kogan 2009; Nassar 2009).

There has been significant debate about the cause of the recent rise in prevalence of ASD, but the influence of increased awareness of the disorder among health professionals and the community at large, and the role of diagnostic substitution, should not be underestimated (Croen 2002; Atladottir 2007). There are other candidate explanations, including the possibility of environmental causes of the rising prevalence estimates, though, as yet, there is no good empirical evidence for these (Rutter 2005). Baird et al (Baird 2006) conclude that "Whether the increase is due to better ascertainment, broadening diagnostic criteria, or increased incidence is unclear" (p. 210).

Within the disorder there is a male to female ratio of 4:1 or 5:1 (Baird 2006; Kogan 2009), as noted in the set of case studies, which defined the condition for the first time (Kanner 1943). ASDs have this feature in common with most other neurodevelopmental disorders (such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), dyslexia, dyspraxia), though to a greater extent. As yet, there is no empirical evidence for systematic differences between male and female individuals with ASD (Hartley 2009).

Theory of Mind

The term 'Theory of Mind' (ToM) describes the ability to understand another's thoughts, beliefs, and other internal states and was originally applied to the study of non‐human primate cognition (Premack 1978). The term has since been developed in a number of different directions (e.g. Carruthers 1996), including in research into ASD. The first application of the term in ASD research was in an experiment which used false‐belief paradigms to explore ToM in children with autism (Baron‐Cohen 1985). In this study, children were presented with a scenario in which a doll, Sally, 'believed' her marble was in the basket where she left it. However, the child and experimenter knew that while Sally was elsewhere, another doll had moved the marble into a box. The key question was "Where will Sally look for her marble?" Typically‐developing children from the age of four years, sometimes earlier, can correctly ascertain that Sally will look in the basket; she holds a false belief about the location of the marble (Wellman 2001). Children with ASD are much less likely to give a correct answer to this question at age four years. They normally claim that Sally will look in the box, in accordance with reality, but incompatible with Sally's knowledge of the situation.

Research into ToM in children and adults with ASD has been prolific over the last 25 years (e.g. Baron‐Cohen 2000). While the details are subject to debate, it is widely accepted that people with ASD do not possess a fully‐functioning theory of mind; even high‐functioning adults with ASD may struggle with complex ToM tasks (Ponnet 2004). ToM has been placed in a developmental context, consisting of a range of precursor skills, including following eye‐gaze, establishing joint attention, imitation, pretend play, and emotion recognition (Melzoff 1993; Baron‐Cohen 1995; Charman 2000; Wellman 2000; Ruffman 2001). ToM then also links to subsequent social and communication skills, including the development of language (Tager‐Flusberg 2000; Garfield 2001). As a result, many believe that failures of ToM are central to explaining the difficulties experienced by people with ASD (though not a sufficient explanation). Therefore, ToM and its precursor skills are targets for interventions.

Description of the intervention

A 'Theory of Mind intervention' is a treatment or therapy, which is explicitly or implicitly based on the Theory of Mind (ToM) cognitive model of ASD. ToM interventions target those skills which are either potential components or precursors of ToM (Swettenham 2000). One example of an intervention targeting such skills is using 'thought‐bubbles’ to teach children with ASD to understand others' thoughts and beliefs by illustrating these in bubbles (as in a cartoon) (Parsons 1999). Specific precursor skills can also be taught such as helping a child to make eye‐contact to accompany pointing to an object of interest (joint attention). More detail on which interventions are eligible for inclusion in this review is given in the Methods section, but we will only consider interventions that explicitly target ToM skills.

ToM interventions can be contrasted with other types of treatment for ASD. Many intervention models focus on behaviour management and personal skills training, using a basic conditioning model for learning (repetition; rewarding desirable behaviour; 'punishing' or ignoring behaviour that the therapist finds undesirable such as tantrums). In addition, most management strategies for ASD occur within a fairly structured timetable as people with ASD tend to feel more comfortable following familiar routines in a consistent environment, and respond very poorly to change.

How the intervention might work

In a chapter reviewing evidence for the possibility of teaching ToM to individuals with autism, Swettenham states (p. 442) that "a successful method for teaching theory of mind may alleviate the impairments in social interaction that are so debilitating in autism" (Swettenham 2000).

The ToM model of autism suggests that the social and communication difficulties that are characteristic of the syndrome stem from a failure to develop an intact ToM. Certainly there is evidence that ToM is correlated with real‐life social skills (Frith 1994) and symptomatology (Joseph 2004). Certain ToM precursor skills also have a direct relationship with symptoms (Mundy 1994). Therefore, training in ToM, or in the precursor or component skills of ToM, should alleviate the social and communication difficulties experienced by individuals with the disorder. For example, a targeted joint attention intervention for autism produced improvements in children's responsiveness to joint attention opportunities and also improved sharing and language (Kasari 2006; Kasari 2008), indicating that ToM interventions may have consequences for wider developmental abilities.

It is possible that interventions targeting different ToM skills will produce varied types of change in participants, and the extent of change may vary. The method of delivery of the intervention may also produce different outcomes. For example, one might expect an intervention delivered by a trained therapist to have greater impact than one delivered by parents. An intervention taught in school may have a different impact to one delivered in the home. The duration of the intervention may also be significant. Deficits in ToM and related skills vary with age (Happe 1995), IQ (Ozonoff 1991a; Happe 1994; Bowler 1997), specific diagnosis (Ozonoff 1991b; Bowler 1992) and verbal ability (Happe 1995; Garfield 2001). As a result, the specific skill being targeted, the method of intervention delivery, its duration and individual differences between participants in ToM intervention studies will be important factors for consideration and for statistical analysis in this review.

Why it is important to do this review

To date, there is no comprehensive review of ToM interventions for autism, despite the fact that the first study attempting to teach ToM to individuals with autism was published in 1995 (Ozonoff 1995). This review will be of relevance to both the clinical and academic research communities, since ToM interventions not only have the potential to benefit people with ASD, but also provide a unique and rigorous way to test the theoretical model on which they are based.

Objectives

To assess the effect of interventions, based on the Theory of Mind (ToM) model, for autism spectrum disorders (ASD), on symptoms in the core diagnostic domains of social and communication impairments in autism, and on language and ToM skills. In addition, in so‐doing, to test the applied value of the ToM model of autism.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised and quasi‐randomised trials (defined as trials in which allocation was made by, for example, alternate allocation or allocation by date of birth).

Types of participants

Participants of any age with a diagnosis of an ASD, including autism, atypical autism, Asperger’s syndrome, and PDD‐NOS, according to either ICD‐10 (Internal Classification of Diseases), DSM‐IV or DSM‐V (Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) criteria. All diagnostic categories could be included since the validity of differentiating between categories on the spectrum is not well established (Klin 2005). Furthermore, the ToM cognitive model does not distinguish, on a qualitative basis, between different forms of ASD. Participants must have received a ‘best estimate’ clinical diagnosis, confirmed by the study authors. That is, at a minimum, diagnosis by a multidisciplinary clinical team using standard procedures with reference to the international classification systems. Use of a particular diagnostic tool, such as the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) (Lord 2000) or the Autism Diagnostic Interview (ADI‐R) (Lord 1994), was desirable but not required. Co‐morbid cases were also eligible for inclusion since these individuals are just as needful of intervention for their specifically autistic difficulties.

Types of interventions

Interventions eligible for inclusion in this review:

explicitly state that they are designed to teach ToM; or

explicitly state that they are designed to teach precursor skills of ToM; or

explicitly state that they are based on or inspired by ToM models of autism; or

explicitly state that they aim to test the ToM model of autism.

We reiterate that ToM (theory of mind) describes the ability to understand another's thoughts, beliefs, and other internal states and is encapsulated in a test of false belief. Prior to the development of false‐belief understanding (at about four years old in typical development), associated precursor skills are in evidence such as joint attention, imitation, and emotion recognition. Relevant interventions include those which explicitly teach children to understand others' mental states (e.g. using visual representations of mental states McGregor 1998) and those which use naturalistic teaching to develop imitation skills (Heimann 2006).

The following kinds of interventions are not included in this review:

interventions which do not meet the criteria given above;

medical interventions (e.g. risperidone for aggression in ASD);

dietary interventions (e.g. gluten‐free and casein‐free diets);

interventions which target a particular behaviour rather than a cognitive skill (e.g. over‐sensitivity to light modified using colour spectacles; sleep difficulties modified using applied behavioural analysis);

language‐focused interventions (e.g. to make requests using the Picture Exchange Communication System or spoken single words);

interventions which have a broad‐base both in terms of methods (e.g. combining computerised learning with parent training and social skills groups) and targets (i.e. addressing a range of social communication skills, some which are ToM‐linked but also more general skills such as turn‐taking, friendship skills, and conversation).

ToM interventions are compared with the following conditions, where these are used:

treatment‐as‐usual/wait‐list control;

‘placebo’ interventions, for example a ‘contact control’ such as watching Thomas the Tank Engine DVDs (e.g. Young 2012);

intervention with no therapeutic content, (e.g. group leisure activities (Baghdadli 2013).

All ‘doses’ (that is the number and length of treatment sessions per week), durations, and methods were eligible for inclusion.

Types of outcome measures

Outcome measures do not form part of the criteria for inclusion of studies in this review.

Primary outcomes

Primary outcomes at a participant symptom level, measured using standardised diagnostic assessments or clinical report. Outcomes will be in each of two symptom domains that have until recently been used in clinical diagnosis and are followed by most diagnostic tests for autism. These are as follows, with examples of outcomes in each category as measured by the ADOS (Lord 2000) or ADI (Lord 1994).

Communication: overall level of non‐echoed language; stereotyped or idiosyncratic use of words or phrases; pointing; gestures; conversation.

Social function: unusual eye‐contact; facial expressions directed to others; spontaneous initiation of joint attention; shared enjoyment in interaction; quality of rapport.

The third diagnostic domain of Restricted and Repetitive Behaviours (imaginative play or creativity; unusual sensory interests; unusually repetitive interests or stereotyped behaviours; compulsions or rituals) is not included as an expected primary outcome.

Secondary outcomes

In addition, the following secondary outcomes will be included.

PARTICIPANT, direct measurement

Intervention‐specific: change in targeted cognitive skill such as false‐belief understanding

Change in participant behaviour or quality of interpersonal interaction, or both, measured by direct observation.

PARENT, teacher (or other individual in caring or educational relationship to the participant) report

Change in participant behaviour and skills or deficits such as: adaptive skills; school success; challenging behaviours; social participation measured by parent, teacher or other report

Acceptability of intervention (time, cost)

OTHER

Intervention process measures e.g. rate of drop‐out

Economic data e.g. financial cost of intervention; time commitment required

Main outcomes for ’Summary of findings’ table

The following outcomes measures are specified for a 'Summary of findings' table:

symptom level, communication domain;

symptom level, social interaction domain;

general communication ability (e.g. vocabulary);

'Theory of Mind' ability (e.g. false‐belief test score).

Where data were available, we planned to organise outcomes into three time points: immediately post‐treatment; medium‐term outcome (up to six months post‐treatment); and long term (more than six months post‐treatment).

The Table 1 reports on these outcomes and also includes an estimate of the quality of evidence in each category.

Search methods for identification of studies

The complex nature of ToM interventions makes them difficult to capture adequately using search terms. Therefore, to avoid missing relevant studies, we used a highly sensitive search strategy with just two concepts: the condition (ASD) and a search filter to find RCTs. The core search strategy was developed in Ovid MEDLINE and uses the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for identifying randomised trials (Lefebvre 2008), The MEDLINE strategy was adapted for other databases using appropriate syntax and controlled vocabulary. The initial searches were run in July 2010 without any date or language restrictions. We last updated the searches on 6 August 2013, apart from ASSIA which was no longer available to us.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases in August 2013.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2013, Issue 7, part of The Cochrane Library.

Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to July Week 4 2013.

EMBASE 1980 to 2013 Week 31.

CINAHLPlus 1937 to current.

PsycINFO 1806 to July Week 5 2013.

ERIC 1966 to current.

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts: ASSIA (CSA) 1987 to current.

Social Services Abstracts 1979 to current.

metaRegister of Controlled Trials (controlled‐trials.com/mrct/).

ICTRP (apps.who.int/trialsearch/).

UKCRN ‐ UK Clinical Trials Network (public.ukcrn.org.uk/search/).

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/).

Autism Data (autism.org.uk/autismdata/).

The search strategies for each source are in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

In addition to searches of electronic databases, we contacted key authors in the field directly and asked them to provide any relevant published, unpublished or in‐progress data, including post‐graduate dissertations. We also searched the bibliographies of key articles for citations of papers not found electronically. Searches were made for in‐progress, or unpublished clinical trials. Finally, we searched the online databases of journals that regularly publish work on this topic. These journals were the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Autism: International Journal of Research and Practice. We also searched the proceedings of the International Meeting for Autism Research.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

All citations sourced from the search strategy were transferred to EndNote, a reference management programme. Initial screening of titles and abstracts by an experienced research assistant (EM or FMcC) eliminated all those citations obviously irrelevant to the topic, for example, prevalence studies, studies unrelated to ASD, and single case studies. Thereafter, two review authors (SFW and either EM or FMcC) assessed and selected studies for inclusion from the group of superficially relevant studies. In the event of a disagreement, resolution was reached in discussion with a third author (HM), if necessary following inspection of the full paper.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (SFW and either EM or FMcC) independently extracted data from selected trials using a specially designed data extraction form. Extracted data included methods (dose and frequency of intervention); diagnostic description of participants, and type of intervention, including target, intensity, duration, and method of application (parent‐mediated, therapist, school‐based etc.). Disagreements were resolved in consultation with a third author (HM).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (SFW and either EM or FMcC) independently assessed the risk of bias of included studies in the following domains: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants and personnel; blinding of outcome assessment; incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; other sources of bias. We used The Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias in these areas. The process involved recording the appropriate information for each study (e.g. describing the method used to conceal allocation in detail) and evaluating whether there was risk of bias in that area (e.g. was allocation adequately concealed?). Any disagreement was resolved by referral to a third author (HM).

We contacted authors to supply missing information from 16 included studies (Bolte 2002; Solomon 2004; Fisher 2005; Golan 2006; Kasari 2006; Kim 2009; Golan 2010; Kasari 2010; Ryan 2010; Wong 2010; Hopkins 2011; Ingersoll 2012; Young 2012; Baghdadli 2013; Schertz 2013; Wong 2013) and information was received from the majority of authors with the exception of (Solomon 2004; Fisher 2005; Golan 2006; Golan 2010; Wong 2010; Baghdadli 2013).

Studies were allocated to categories according to our evaluation of each area or potential risk of bias as follows:

Random sequence generation

Low risk of bias: adequate sequence generation as indicated by reference to, e.g., random number table, coin tossing, shuffled cards or envelopes, throwing dice, drawing lots.

Unclear (or moderate) risk of bias: indicates uncertainty about whether the sequence was randomly generated.

High risk of bias: a non‐random component is described such as sequence generation by odd or even date of birth, by geographical location or by date of entry to the study.

Allocation concealment

Low risk of bias: participants and investigators enrolling participants unable to foresee assignment as indicated by reference to, e.g., central allocation, opaque envelope procedure, allocation by an independent partner outside the research team.

Unclear (or moderate) risk of bias: indicates uncertainty about whether the allocation was concealed.

High risk of bias: participants and investigators enrolling participants may have been able to foresee assignment as indicated by reference to an open random allocation schedule (e.g. random numbers list), unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternate allocation, allocation by non‐random criteria such as date of birth.

Blinding of participants and personnel

Low risk of bias: participants and personnel blinded to study hypotheses and treatment condition, or incomplete blinding but authors judge that outcome is unlikely to be influenced by lack of blinding. Examples might be when participants are very young and/or low‐functioning people with autism and are unlikely to be aware of intervention targets, and where outcome is assessed using a measure resilient to performance bias such as computerised assessment. We note that in behavioural studies, such as those included in this review, it is rarely possible to blind participants and/or personnel.

Unclear (or moderate) risk of bias: indicates uncertainty about whether blinding was consistent, perhaps due to insufficient information being available, or partial blinding (e.g. of participants but not personnel).

High risk of bias: participants and personnel not blind to study hypotheses or treatment condition, and outcome likely to be influenced by this lack of blinding.

Blinding of outcome assessment

Low risk of bias: outcome examiners and scorers blinded to participant group membership, or blinding of some outcome assessors with good evidence of agreement between blinded and unblinded raters on outcome measures, or outcome assessors not blind but outcome measurement unlikely to be influenced by this lack of blinding.

Unclear (or moderate) risk of bias: indicates uncertainty about whether blinding was consistent, perhaps due to insufficient information being available.

High risk of bias: outcome examiners and scorers not blind to participant group membership, and outcome likely to be influenced by this lack of blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

Low risk: no missing data, or reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome, or missing data balanced across groups with similar reasons in each case.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient reporting of attrition or exclusions to permit accurate judgement.

High risk of bias: reasons for missing data likely to be related to true outcome, with imbalance in numbers between groups or different reasons between groups.

Selective reporting

Low risk: study protocol available and all pre‐specified outcomes are reported in the pre‐specified way, or clear from the published reports that all expected outcomes are included.

Unclear (moderate) risk of bias: insufficient information to permit accurate judgement.

High risk of bias: not all of the study's primary outcomes have been reported, or outcomes which were not pre‐specified are reported, or one or more primary outcomes have been reported for only a sub‐set of the sample, or one or more outcomes are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered into a meta‐analysis.

Other bias

Low risk of bias: the study appears to be free of other sources of bias.

Unclear (or moderate) risk of bias: there may be an additional risk of bias but there is insufficient information to fully assess this risk, or it is unclear whether the risk would introduce bias in study results.

High risk of bias: the study has one important additional risk of bias such as a source of bias related to the study design, or claims of fraudulence.

In each case, only studies where the assessment of overall risk falls into categories 'Low' or 'Unclear/Moderate' have been included in subsequent analyses.

Measures of treatment effect

Binary and categorical data

No studies reported binary outcome data in the current review version. Should they be included in future updates, methods for analysing them appear in the published protocol for the review (Fletcher‐Watson 2010).

Continuous data

Where standardised assessment tools generated a continuous score as the outcome measure, and means and standard deviations were reported or provided by the authors, comparisons were made between the means of these scores. When selecting studies for possible meta‐analysis the following criteria were of principal importance.

Similarity of trial design ‐ especially whether the 'control' condition had therapeutic content or not

Similarity of intervention target

Similarity of outcome measure ‐ the quality being measured, the unit of measurement, and the method of measurement (e.g. parent‐report, video coding, standardised assessment)

Where measures were on different scales but those scales were clinically homogeneous, meta‐analyses used standardised mean difference with Hedges' g correction for small sample sizes.

Unit of analysis issues

No cluster‐randomised trials were included in the current review version. Methods for analysis are recorded in additional Table 2.

1. Additional methods.

| Review section | Item | Methods |

| Unit of Analysis | Cluster‐randomised trials | Authors will use a summary measure from each cluster and conduct the analysis at the level of allocation (that is sample size = number of clusters). However, if there are very few clusters this would significantly reduce the power of the trial, in which case the authors will attempt to extract a direct estimate of the risk ratio using an analysis that accounts for the cluster design, such as a multilevel model, a variance components analysis or generalised estimating equations (GEEs). Statistical advice will be sought to determine which method is appropriate for the particular trials to be included. |

| Subgroup Analysis | Identification of dimensions for subgroup analysis | In future updates the following clinically‐relevant differences may be the focus of subgroup analyses:

|

| Sensitivity Analysis | Identification of variables for sensitivity analysis | In future updates the impact of factors such as high rates of loss to follow‐up or inadequate blinding on outcomes will be explored. |

| Dealing with Missing Data | Procedures for imputation in the event of issues with missing data | Should unacceptable levels and/or non‐random missing data be found in future studies for inclusion in the review, the authors will attempt to impute missing values. Imputation may use individual data (where available from the original report authors) OR group‐level summary statistics (which are normally included in published reports). Mean imputation will be used where variables are normally distributed, and the median will be used for non‐normal distributions. In either case the review will report how the imputed values appear to change the outcome of the study/meta‐analysis and use this variability to inform the strength of our conclusions. |

Dealing with missing data

Missing data were assessed for each individual study according to the reports provided by authors. For included studies reporting drop‐out, we reported the number of participants included in the final analysis as a proportion of those participants who began the intervention (see Characteristics of included studies). Reasons for missing data are also reported (that is, whether data are missing at random or not). In all cases, we concluded that data were missing at random, and the remaining data were analysed and the missing data ignored.

Where summary data are missing, trial authors were contacted. If no reply was forthcoming or the required summaries were not made available, the study was included in the review and we assessed and discussed the extent to which its absence from meta‐analysis affects the review results (e.g. Bolte 2002).

No studies reported the loss of significant quantities of data, without sufficient explanation, and there was no evidence of non‐random missing data. Therefore, the review authors agree that the conclusions of individual studies are not compromised by missing data. The extent to which the results of the review may be altered by the missing data is assessed and discussed (Quality of the evidence).

Additional procedures for dealing with non‐random missing data in future appear in the published review protocol (Fletcher‐Watson 2010) and Table 2.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Consistency of results was assessed visually and by a Chi2 test. Where meta‐analysis included only a small number of studies, or where studies had small sample sizes, a P value of 0.10 was applied for statistical significance. In addition, since Chi2 can have low power when only a few studies or studies of a small sample size are available, we used the I2 statistic to measure the amount of observed variability in effect sizes that can be attributed to true heterogeneity (Higgins 2008).

Assessment of reporting biases

Where sufficient studies were found, funnel plots were inspected to investigate any relationship between effect size and sample size. Such a relationship could be due to publication or related biases, or due to systematic differences between small and large studies.

Data synthesis

Data synthesis was performed using RevMan 5.2. Binary data were not reported in any of the included studies but could be assessed in future review versions. Where two or more studies suitable for inclusion were found, and the studies were considered to be homogenous, a meta‐analysis was performed on the results. Homogeneity decisions were based on examination of a series of factors identified in the review protocol including the following.

Similarity in intervention delivery type (e.g. therapist‐led, parent training)

Similarity in intervention target skill (e.g. emotion recognition, imitation, joint attention)

Similarity in participant populations (e.g. intellectual level in the normal or low range, specific autism diagnostic category, age)

In addition, the following two further factors were developed post hoc in response to the wide variability in study design and outcome measure found.

Similarity in primary outcome measurement

Similarity in comparison group status (e.g. did the study compare two different interventions or compare an intervention with a wait‐list or treatment‐as‐usual control)

It is essential to distinguish between measures of primary outcome when assessing intervention efficacy for two main reasons. The first is that there is significant evidence that people with ASD do not generalise skills across contexts. For example, Golan 2010 found differences in outcome measures by close and distant generalisation tasks even though these were all measures of emotion and mental state recognition. Therefore, studies measuring outcome using tasks which differ in complexity and in connection to the teaching context should not be compared directly. The second reason is that the method of measurement can produce widely varying distributions, which are not amendable to combination. For example, Kasari 2010 measured percentage of total time that a mother‐child dyad were jointly engaged, while Goods 2013 reported the number of instances that specific types of joint engagement were observed. It is not possible to combine these two variables, which have also been collected in different settings (laboratory artificial mother‐child play versus naturalistic classroom observation) and over different periods of time.

Comparison group status is another key consideration when combining studies. A study that shows an intervention effect compared with a 'placebo' group or compared with another intervention may have a smaller effect size than one comparing intervention and wait‐list control. However, the former study has the more powerful design and so this smaller effect should be more influential on conclusions.

A random‐effects model analysis was used since we do not assume that each study is estimating exactly the same quantity.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses were not possible in this version of the review. Dimensions for possible future subgroup analyses are included in additional Table 2.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was not possible for this version of the review. Details of planned future sensitivity analyses are included in additional Table 2.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

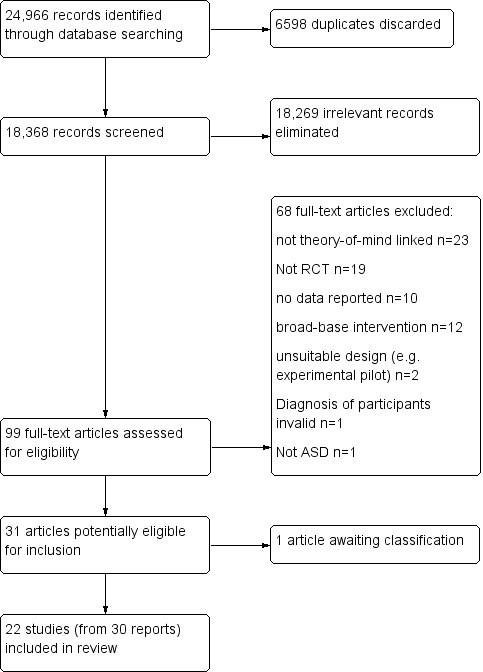

Searches were carried out in July 2010, and again in July 2012, and August 2013, yielding 18,368 records of potential relevance after de‐duplication (July 2010: 11,822 records, July 2012: 4171 records, August 2013: 2375 records). Assessment of titles and abstracts and elimination of duplicates between the searches resulted in a list of 99 records for closer examination (Figure 1). One of these articles is only available in French and is currently awaiting classification pending translation (Baghdadli 2010).

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

We included 22 studies involving 695 participants in this review; in each case the main study is reported in a published journal article and the dates of publication span from 1996 to 2013. There were 17 studies reported in a single published journal article: Solomon 2004; Fisher 2005; Golan 2006; Golan 2010; Kasari 2010; Landa 2011; Ryan 2010; Wong 2010; Begeer 2011; Hopkins 2011; Kaale 2012; Williams 2012; Young 2012; Baghdadli 2013; Goods 2013; Schertz 2013; Wong 2013. In the case of Golan 2006, two studies are reported of which only Experiment One is an RCT, and therefore only this first data set is included in the review.

In addition, there are five studies for which data have been reported in multiple outputs. These are a therapist‐led theory of mind intervention (Hadwin 1996), a computerised emotion recognition intervention study (Bolte 2002), an imitation intervention study (Ingersoll 2012), a music therapy study (Kim 2009), and a joint attention and symbolic play intervention conducted by Kasari and colleagues (Kasari 2006). In the case of the Kasari study, one output is an unpublished PhD thesis (Arora 2008).

All 22 studies described themselves as randomised controlled trials, and they were conducted in a wide variety of locations: Scandinavia (Bolte 2002; Kaale 2012); mainland Europe (Begeer 2011; Baghdadli 2013); the UK and Ireland (Hadwin 1996; Fisher 2005; Golan 2006; Golan 2010; Ryan 2010); the Far East (Kim 2009; Wong 2010); Australia (Williams 2012; Young 2012); and the USA (Solomon 2004; Kasari 2006; Kasari 2010; Landa 2011; Hopkins 2011; Ingersoll 2012; Goods 2013; Schertz 2013; Wong 2013).

Participant baseline characteristics

Participants varied widely in age‐range from preschoolers (e.g. Kasari 2006) to adolescents and adults (e.g. Bolte 2002) but a majority focused on either pre‐school or primary‐school aged children (see Characteristics of included studies). Almost all studies included both boys and girls, though the proportion of male participants was much higher than females, corresponding to the known greater prevalence of diagnosed ASD in males (Kogan 2009). Four studies reported an all‐male sample (Bolte 2002; Solomon 2004; Kim 2009; Baghdadli 2013).

For all studies, a diagnosis of an ASD was a requirement for inclusion. A large proportion confirmed diagnosis using a clinical instrument such as the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS, Lord 1994) or the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS, Schopler 1986). Two studies accepted prior clinical diagnosis as adequate (Hadwin 1996; Fisher 2005), but these also instituted a checklist confirming that all diagnostic criteria were met. Participants were reported as having a range of ASD diagnoses, including autism, autism spectrum disorder, pervasive developmental disorder ‐ not otherwise specified (PDD‐NOS), high‐functioning autism (HFA), and Asperger's syndrome (AS). Studies recruiting participants with HFA and/or AS had participants in the adolescent and adult age‐range (e.g. Bolte 2002; Golan 2006) or late childhood (Solomon 2004; Begeer 2011). Studies with young children and preschoolers largely described participants as having 'core' autism, or ASD.

All studies reported some measure of general intellectual ability such as verbal mental age. Almost half of the included studies included a sample in the normal intellectual range (Bolte 2002; Solomon 2004; Golan 2006; Kim 2009; Golan 2010; Ryan 2010; Begeer 2011; Young 2012; Baghdadli 2013) and the rest reported on a sample with intellectual disability. One study split the participant group into those with and without associated intellectual delay (Hopkins 2011).

Sample sizes varied widely from n = 10 (Bolte 2002; Kim 2009) to n = 61 (Kaale 2012). On the whole, very small proportions of participants failed to complete the interventions. The maximum drop‐out rate was 27% from a small sample (Goods 2013), but many studies reported no drop‐out at all.

Intervention target types

The reported intervention types can be assigned to the following categories, taken from the review protocol.

Interventions that explicitly state that they are designed to teach ToM = (Hadwin 1996; Solomon 2004; Fisher 2005; Begeer 2011; Baghdadli 2013).

Interventions that explicitly state that they are designed to teach precursor skills of ToM = (Bolte 2002; Golan 2006; Kasari 2006; Kim 2009; Golan 2010; Kasari 2010; Landa 2011; Ryan 2010; Wong 2010; Hopkins 2011; Ingersoll 2012; Kaale 2012; Williams 2012; Young 2012; Goods 2013; Schertz 2013; Wong 2013).

Interventions that explicitly state that they are based on or inspired by ToM models of autism.

Interventions that explicitly state that they are designed to test the ToM model of autism.

There were no studies falling into category three or four and the vast majority of studies stated that they were designed to teach precursor skills of ToM. Within this category we could also identify some common intervention targets including the following.

Emotion recognition (Bolte 2002; Golan 2006; Golan 2010; Ryan 2010; Hopkins 2011; Williams 2012; Young 2012)

Joint attention and social communication (Kasari 2006; Kim 2009; Kasari 2010; Landa 2011; Wong 2010; Kaale 2012; Goods 2013; Schertz 2013; Wong 2013)

Imitation skills (Ingersoll 2012)

Delivery methods, durations and dose

Three studies reported on the use of a computer program to deliver the intervention (Bolte 2002; Golan 2006; Hopkins 2011) and all of these studies had emotion recognition as the target skill. Three studies investigated the effect of a set of specially‐designed cartoons on emotion recognition (Golan 2010; Williams 2012; Young 2012). Other studies investigated the effects of one‐to‐one therapist‐led interventions (Hadwin 1996; Fisher 2005; Kasari 2006; Landa 2011; Ryan 2010; Wong 2010; Ingersoll 2012; Goods 2013) and two of these used the same manualised treatment program (Kasari 2006; Kaale 2012). Some used a therapist‐led approach in a group treatment setting (Solomon 2004; Begeer 2011; Baghdadli 2013) and one was a group music therapy approach (Kim 2009). Non‐expert intervention delivery was rare with only four studies reporting a parent‐training element (Solomon 2004; Kasari 2010; Begeer 2011; Schertz 2013) and one study reporting on teacher‐training for intervention delivery in the classroom (Wong 2013).

Intervention durations varied widely from two or three weeks (Hadwin 1996; Young 2012) to six months (Landa 2011). Dose was more consistent, with most falling within a range of 30 minutes per week (Kim 2009) to 3.5 hours per week (Hadwin 1996; Kasari 2006; Golan 2010), and one outlying intervention which reported therapist contact time of 2.5 hours per day (Landa 2011).

Most studies had wait‐list or treatment‐as‐usual control conditions. Six studies (Kim 2009; Landa 2011; Hopkins 2011; Williams 2012; Young 2012; Baghdadli 2013) included control conditions, which were not expected to have an impact on intervention outcome but were included as a contact control only. These included toy play, non‐synchronous one‐to‐one time, using art software, group leisure activities, and watching a Thomas the Tank Engine DVD.

Outcome measures

On the whole, studies rarely identified a single primary outcome measure. Those that organised outcomes into primary and secondary categories usually had multiple measures in each category.

The outcome measures used most commonly included the following.

Recognition of emotion from a variety of stimuli, including static images of faces, static images of the eyes, film clips, short stories, and cartoons (Bolte 2002; Solomon 2004; Golan 2006; Golan 2010; Ryan 2010; Hopkins 2011; Williams 2012; Young 2012; Baghdadli 2013)

Joint attention and joint engagement behaviours, often measured using video coding of parent‐child or teacher‐child interactions (Kasari 2006; Kim 2009; Kasari 2010; Landa 2011; Ingersoll 2012; Kaale 2012; Goods 2013; Schertz 2013; Wong 2013)

Direct assessment of ToM abilities (Hadwin 1996; Solomon 2004; Fisher 2005; Begeer 2011; Williams 2012)

Imitation skills (Landa 2011; Ingersoll 2012)

Diagnostic outcome (Wong 2010, Young 2012)

The studies below included the following additional outcome measures.

Caregiver measures such as quality of involvement, adherence to treatment, mental health or satisfaction surveys (Solomon 2004; Kasari 2010; Landa 2011, Wong 2010; Baghdadli 2013; Wong 2013)

General social skills measures, including rating scales and observation (Kim 2009; Begeer 2011; Hopkins 2011; Ingersoll 2012; Williams 2012)

Symbolic play measures (Hadwin 1996; Wong 2010) or assessments of play variety (Goods 2013; Wong 2013)

Language (Kasari 2006; Landa 2011) and conversational skills (Hadwin 1996)

fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging ‐ assessment of brain activity in facial recognition areas) (Bolte 2002)

Adaptive function (Kasari 2006; Schertz 2013) and general intellectual abilities (Landa 2011; Schertz 2013)

Selection for meta‐analyses

Using protocol criteria, three groups of studies were identified as eligible for meta‐analysis.

Emotion recognition studies, with a treatment‐as‐usual control, and outcome measures using judgements of emotional expressions from static photographs of faces (Analysis 1.2).

Joint attention and social communication studies, with a treatment‐as‐usual control, and outcome measures using coding of parent‐child interaction videos (Analysis 1.1).

Joint attention studies, with a treatment‐as‐usual control, and outcome measures of joint attention initiation frequency within a standardised assessment (the Early Social Communication Scales) (Analysis 1.3).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Treatment effects in meta‐analysis, Outcome 2 Emotion recognition from face photographs, TAU control.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Treatment effects in meta‐analysis, Outcome 1 Joint engagement in mother‐child interaction.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Treatment effects in meta‐analysis, Outcome 3 Joint attention initiations in standardised assessment.

Excluded studies

Examination of the abstracts and, where necessary, full texts of reports resulted in a number of exclusions, listed in Characteristics of excluded studies for the following reasons.

Not fitting the ToM‐linked criteria for inclusion (23 reports)

Not presenting any new data (10 reports)

Not randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials (18 reports)

Not reporting on a sample of people with ASD (one report)

Reporting on a broad‐based intervention without a specific ToM‐linked focus (12 reports)

Diagnosis of participants invalid (one report)

Reporting on an experimental pilot RCT with a very short intervention period (three reports)

Risk of bias in included studies

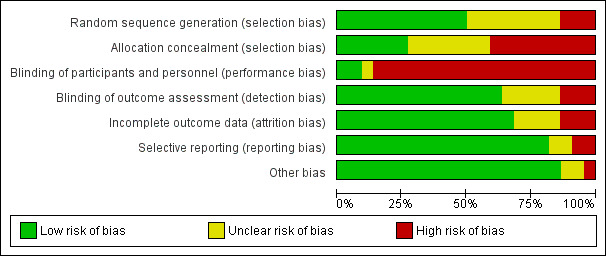

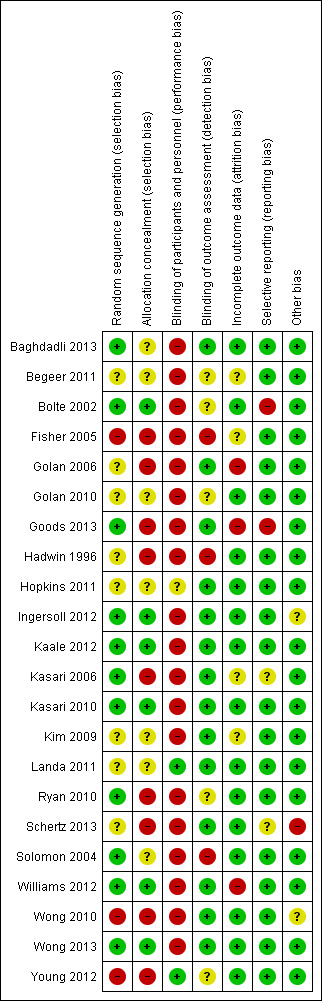

Further information was requested from the majority of authors as papers were not always complete in their reporting. The summaries of 'Risk of bias' judgements are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

All studies in this review described themselves as randomised controlled trials and were included on this basis. One was later revealed to have used a non‐random allocation procedure (Young 2012). This study states that participants were "randomly allocated to two groups" (Young 2012, p. 986) but email correspondence to clarify the exact allocation procedure revealed that in fact this study used alternate allocation by study enrolment. In other studies, a similar statement is made but rarely is full detail provided.

Thus, only half of the included studies (11 reports) were judged to have 'low' risk of bias in terms of the description of the method of randomisation. Only six were judged to have adequately described allocation concealment. Therefore, the majority of included studies have either 'unclear' or 'high' risk of bias in this category.

In some cases, efforts were made to conceal allocation, for example, using randomisation within blocks to ensure random allocation and smooth delivery of the intervention (Goods 2013). However, the use of blocks of fixed length meant that the final case within each block would be allocated to a known condition.

Blinding

The majority of studies were judged at high risk of bias in this category (19/22 studies, 86%). The three exceptions are Landa 2011 and Hopkins 2011 where partial blinding was achieved, and Young 2012 who created a study design with full blinding as the intervention was delivered not by a therapist but on a DVD.

Blinding of participants and personnel was rarely possible in the studies included in this review, as behavioural interventions were being used and these were often therapist‐led. Blinding of outcome assessors is easier to achieve and 14 studies (64%) clearly reported blinding at this stage, though in a further five cases it was unclear whether this was completed adequately.

Though risk of bias must be judged as high when blinding is not achieved, a number of mitigating factors might help to reduce the impact of this risk.

When working with very young children or those severely affected by autism and/or intellectual disabilities, it is reasonable to judge that participants are relatively oblivious to the intervention content and certainly to the expected outcomes.

Likewise, although participants and parents may be aware of their group they may not be apprised of the hypotheses of the study. For example, Golan 2006 worked with able adults with autism who were asked to "help in the evaluation of a piece of new software" (p. 600) rather than being told the software was designed to help them learn to understand emotions.

Many studies used automated outcome measures, especially when using a computerised intervention (e.g. Bolte 2002; Golan 2006), which are more resilient to bias than experimenter‐led methods.

Studies using multiple outcome measures often achieved blinding for a sub‐set of those outcomes (e.g. Hopkins 2011).

Incomplete outcome data

There was very little evidence of attrition among the studies reported here, and only three of the included studies were judged to be at high risk of bias. The most extreme case of likely bias was (Goods 2013) who reported 73% retention and analysed outcome data for intervention completers only. Ten studies (45%) reported outcome data for all of the original sample and where there was participant drop‐out this was usually described with clear reasons to help the reader judge the impact of this drop‐out. Where studies were judged at unclear risk of bias, this was due to either a lack of sufficient detail in the published report (e.g. Begeer 2011) or because it was difficult to evaluate the impact of the drop‐out on findings (e.g. Kim 2009; Kasari 2006).

Selective reporting

Selective reporting was not evident among the papers included and 18 studies (82%) were judged at low risk of bias in this category. However, it must be noted that the tendency not to identify a primary outcome measure and to use multiple outcomes does hinder conclusions about intervention efficacy.

One study (Bolte 2002) did not report means for a relevant outcome measure ‐ the International Affective Pictures System or IAPS ‐ for which there was no significant group difference. The study authors were contacted to provide mean scores but were unable to provide these due to the time elapsed since the study and records not having been kept. One further study (Ryan 2010) reported data in graphical form only, but the authors kindly provided accurate means and SDs for these data. Conversely, Goods 2013 reported non‐significant findings in a table of results but these were not discussed in the text.

Other potential sources of bias

One study reported a significant difference in ratings provided by mothers and ratings provided by independent examiners (Kim 2009) with professional ratings providing a more positive estimate of intervention efficacy. This bias is judged to be of low risk for two reasons. First, the professional ratings used to construct the primary outcome for the intervention were blind to group. Second, the authors provided a reasonable justification for the underestimation of intervention efficacy by parent ratings, which is that mothers over‐estimate pre‐intervention abilities of their children, and thus under‐estimate efficacy of the intervention.

Another study combined the wait‐list control group with the intervention group to provide a larger sample size for analysis of some intervention efficacy measures (Wong 2010). However, prior to this stage in the analysis, between group comparisons were also made and these provided the primary outcomes for the study. The impact of this bias is judged to be unclear as while a between group comparison was made, the long‐term maintenance of intervention gains is disguised by the combination of data sets at the final time point.

Schertz 2013 adopted a variable intervention period which could have weighted findings towards a positive conclusion regarding intervention efficacy. Their strategy was to recruit participants who were demonstrably lacking the target joint attention skills. Participants were then paired and randomly assigned to intervention or treatment‐as‐usual control groups. Intervention then proceeded until an individual participating child had achieved the target skill. At this point, exit assessment measures were taken for that child and their matched pair. Therefore, within each pair, participants experienced the same interval between baseline and post‐intervention assessment. However, when analysed as a group, this system ensured that every child in the intervention group had shown significant gains in the target skill, thus biasing the study towards a positive conclusion.

No other potential sources of bias were identified in the studies selected for inclusion in this review. Also, the authors note some examples of particularly good practice in the prevention of bias, including close measurement of treatment adherence in therapist‐led (Baghdadli 2013) and parent‐training studies (Schertz 2013).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Studies in this review used a wide variety of outcome measures, often using measures specific to their intervention target and sometimes designed specifically for that study. In addition, effect sizes, mean differences reported as standardised mean differences (SMD) and confidence intervals (CI) were not always reported, though we include these below where available. Intervention measures are listed in additional Table 3 and discussed below, organised by primary and secondary outcome category. In addition, primary outcome results are collated in the Table 1.

2. Outcome measures used.

| Outcome | Category | Measure | Study |

| Primary | Communication (standardised measure) | Semi‐structured conversation task: telling a story from a picture book | Hadwin 1996 |

| Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) | Young 2012 | ||

| Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS): Language and Communication | Wong 2010 | ||

| Social Function (standardised measure) | Joint Attention: Early Social Communication Scale (ESCS) |

Kaale 2012 Kasari 2006 Ingersoll 2012 Goods 2013 Kim 2009 Wong 2013 |

|

| Communication and Symbolic Behaviour Scales developmental profile | Landa 2011 | ||

| Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS): Reciprocal Social Interaction | Wong 2010 | ||

| Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) | Young 2012 | ||

| Social Emotional Scale (SES), Bayley Scales of Infant Development, 3rd Edition | Ingersoll 2012 | ||

| Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales (VABS), Socialisation subscale | Williams 2012 | ||

| Flexibility & imagination (standardised measure) | none | ||

| Secondary | Intervention specific: ToM | ToM test: standardised interview for Tom understanding Levels of emotional awareness scale for children (LEAS‐C): performance assessment |

Begeer 2011 |

| False‐belief tasks (unexpected transfer and deceptive box): behavioural ToM task Penny Hiding Deception Task: behavioural ToM task Seeing Leads to Knowing Task: behavioural ToM task Knowing/Guessing Task: behavioural ToM task |

Fisher 2005 | ||

| Level of training reached (ToM skills, pretend play skills, emotion understanding) Generalisations to non‐taught tasks (ToM skills, pretend play skills, emotion understanding) Generalisation across skill sets and intervention groups (e.g. effects of ToM intervention on pretend play skills and so on) |

Hadwin 1996 | ||

| ToM: Strange Stories and Faux Pas Recognition Test | Solomon 2004 | ||

| NEPSY‐II ToM task | Williams 2012 | ||

| Intervention specific: emotion recognition | FEFA test module: computerised facial emotion recognition test International Affective Picture System (IAPS) facial emotion recognition test fMRI evidence of change in neural response to emotional stimuli |

Bolte 2002 | |

| Diagnostic Analysis of Nonverbal Accuracy2 (DANVA2) Faces test: emotion recognition |

Solomon 2004 Baghdadli 2013 |

||

| Reading‐the‐Mind‐in‐the‐Eyes task: interpreting mental states from images of eyes |

Fisher 2005 Golan 2006 |

||

| Cambridge MindReading face‐voice battery: computerised emotion recognition test (close generalisation) Emotion recognition from novel film clips (holistic distant generalisation) |

Golan 2006 Williams 2012 |

||

| Matching familiar emotional situations to familiar facial expressions (close generalisation) Matching novel emotional situations to novel facial expressions but familiar characters (unfamiliar close generalisation) Matching novel emotion situations to novel facial expressions on novel faces (distant generalisation) |

Golan 2010 | ||

| Emotion Recognition Test: photographs of faces Emotion Vocabulary Comprehension Test |

Ryan 2010 | ||

| Recognition of emotional expressions from photographs Recognition of emotional expressions from line drawings Benton Facial Recognition Test (short form) |

Hopkins 2011 | ||

| NEPSY: Affection Recognition subtest (recognising emotions from photos of faces) The Faces Task: recognising emotions from photos of faces |

Williams 2012 Young 2012 |

||

| Intervention specific: imitation | Motor Imitation Scale: performance measure of object and gesture imitation Unstructured Imitation Assessment |

Ingersoll 2012 | |

| Socially engaged imitation: observed during examiner/child play session | Landa 2011 | ||

| Participant behaviour: observation | Social Skills Observation: two x 5 minutes, during recess or free time in school | Hopkins 2011 | |

| Joint attention and joint engagement during teacher‐child or therapist‐child play |

Kaale 2012 Kim 2009 |

||

| Joint attention and joint engagement during mother‐child play |

Kaale 2012 Kasari 2006 Kasari 2010 Schertz 2013 |

||

| Structured Play Assessment |

Goods 2013 Wong 2013 |

||

| Symbolic Play Test | Wong 2010 | ||

| Social skills during classroom observation |

Goods 2013 Wong 2013 |

||

| Participant behaviour: report | Index of Empathy for Children and Adolescents: self‐report Children's Social Behaviour Questionnaire (CSBQ): parent report |

Begeer 2011 | |

| ToM Questionnaire: teacher report | Fisher 2005 | ||

| Social Skills Rating System: parent report | Hopkins 2011 | ||

| KidScreen, parent‐report quality of life measure | Baghdadli 2013 | ||

| Problem Behaviour Logs: parent report | Solomon 2004 | ||

| Ritvo‐Freeman Real Life Rating Scale (RFRLRS): parent report | Wong 2010 | ||

| PDD‐BI social approach, rated by both parent and teacher | Kim 2009 | ||

| Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales (VABS) | Schertz 2013 | ||

| Participant behaviour: direct assessment | Reynell Developmental Language Scales (post‐test; six‐month follow‐up, 12‐month follow‐up) | Kasari 2006 | |

| Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL) |

Landa 2011 Schertz 2013 |

||

| Expressive vocabulary test (five‐year follow‐up) | Kasari 2006 | ||

| Differential Abilities Scale (five‐year follow‐up) | Kasari 2006 | ||

| Test of Problem Solving (executive function) | Solomon 2004 | ||

| Acceptibility of Intervention | Parent Adherence to Treatment & Competence: parent report Caregiver Quality of Involvement Scale: observational measure during parent‐child play |

Kasari 2010 | |

| Teacher acceptability of intervention report | Wong 2013 | ||

| Children's Depression Inventory: self‐report Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (to assess parent depression) self‐report |

Solomon 2004 | ||

| Parenting Stress Index short form | Wong 2010 | ||

| Economic data | None |

Unlike the 'Summary of findings' table and the discussion of intervention effects in the main text, the principal organising element for this table is the methodology of each outcome measure. This underscores the great difficulty in comparing findings across studies due to wide variety in assessment scoring systems.

Evaluating primary outcomes: communication

Primary outcome measures in this section were those using standardised assessments to assess communication skills of diagnostic relevance (i.e. more than just expressive language).

Two studies employed diagnostic assessment measures to evaluate change in symptom level within the communication domain. Wong 2010 used a sub‐set of ADOS (Lord 2000) items to evaluate communication gains in response to intervention, finding improvements in relevant items (vocalisation directed to others, gestures, pointing) in the intervention group (median difference = 4 points), but not in the control group (median difference = 2.5 points). This finding is weakened by the fact that these analyses compared change from baseline to outcome in each group separately and there was no between‐group comparison. Furthermore, the ADOS is not intended as an intervention outcome measure, and it is not usual to analyse a sub‐set of items. On the other hand, this finding is strengthened by a comparison that shows no intervention group gains in items pre‐identified as non‐relevant to the intervention. Young 2012 similarly reported change for individual items of the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) (Rutter 2003). Of specific relevance in this outcome category, they analysed change in eye contact and gaze aversion, and found no intervention effects on these items (effect sizes: ηp2 = 0.001 and ηp2 = 0.002 respectively).

For participants at a higher level of communicative sophistication, Hadwin 1996 (reported in Hadwin 1997) evaluated the impact of ToM intervention on complex language skills. They found no effect of intervention on conversational skills, and also raised additional evidence that language level may moderate intervention effects when teaching ToM skills (Hadwin 1996) though this is not explored elsewhere.