Abstract

Scope: Overnutrition in utero is a critical contributor to the susceptibility of diabetes by programming, although the exact mechanism is not clear. In this paper, we aimed to study the long-term effect of a maternal high-fat (HF) diet on offspring through epigenetic modifications.

Procedures: Five-week-old female C57BL6/J mice were fed a HF diet or control diet for 4 weeks before mating and throughout gestation and lactation. At postnatal week 3, pups continued to consume a HF or switched to a control diet for 5 weeks, resulting in four groups of offspring differing by their maternal and postweaning diets.

Results: The maternal HF diet combined with the offspring HF diet caused hyperglycemia and insulin resistance in male pups. Even after changing to the control diet, male pups exposed to the maternal HF diet still exhibited hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance. The livers of pups exposed to a maternal HF diet had a hypermethylated insulin receptor substrate 2 (Irs2) gene and a hypomethylated mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 (Map2k4) gene. Correspondingly, the expression of the Irs2 gene decreased and that of Map2k4 increased in pups exposed to a maternal HF diet.

Conclusion: Maternal overnutrition programs long-term epigenetic modifications, namely, Irs2 and Map2k4 gene methylation in the offspring liver, which in turn predisposes the offspring to diabetes later in life.

Keywords: DNA methylation, insulin receptor substrate, MAPK, maternal high fat diet, epigenetics

Introduction

The incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is dramatically increasing. T2DM has become a major public health problem worldwide. It is clear that genetic factors play important roles in the incidence of T2DM. However, the genetic loci identified by genome-wide association studies (GWASs) can account for only a small proportion of T2DM (<10%) (1, 2). Heritable factors cannot explain the dramatic increase in T2DM, thus recent research has focused on lifestyle as a major factor for the incidence of T2DM (3).

Among lifestyle factors, prenatal and postnatal nutrition imbalances lead to epigenetic programming, which is associated with increased T2DM incidence, including both undernutrition and overnutrition (4). Maternal nutrition is important in determining susceptibility to metabolic disease (5). Epidemiological studies in humans revealed that both under- and overnutrition of the mothers during pregnancy will have far-reaching and long-term outcomes for the health of the offspring in adult life (6, 7). For example, glucose intolerance and insulin resistance were reported in offspring whose mothers were exposed to undernutrition during gestation in the well-known study of the Dutch famine, demonstrating an association (8). Similarly, maternal obesity is associated with increased susceptibility to T2DM in offspring (9, 10). Female rat pups from mothers with high-fat (HF) diet-induced obesity were more prone to obesity (11). We have reported that a maternal low-chromium diet can also program the development of diabetes in offspring (12).

Intrauterine programming has been proposed in which the maternal nutrition environment could affect the metabolism of the offspring throughout life (13). The prenatal and early postnatal period is considered a critical time for adult life. Moreover, the maternal nutrition environment and health status induce epigenetic modifications that affect the incidence of T2DM in offspring. The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) concept has been proposed, and epigenetic mechanisms are considered to possibly underlie DOHaD (14, 15). Development programming in the early life period can increase the risk of T2DM in later life (14). Epigenetic modifications mainly consist of DNA methylation, histone modifications and non-coding RNAs. These epigenetic modifications can affect gene expression via environmental changes (16). DNA methylation is defined as the addition of a methyl group to a cytosine, usually in CpG islands (17). DNA methylation at CpG-rich promoters or gene regulatory regions is normally associated with the inhibition of gene expression (17).

Recently, a small number of studies have described the role of DNA methylation changes in fetal programming to metabolic disease in human and animal models. In human research, newborns with obese parents had altered methylation in multiple imprinted genes in their cord blood (18). In animal research, the results were not consistent. In one study, exposure to a maternal HF diet caused DNA hypermethylation in offspring mouse livers (19). However, Cannon et al. did not detect any effect of the maternal diet on DNA methylation in the male mouse liver (20). Another group reported that exposure of offspring to a maternal HF diet could remodel the hepatic epigenome, if they changed to a control diet during the postweaning period (21). Hence, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying the epigenetic changes induced by a maternal HF diet have not yet been thoroughly identified.

Thus, in this study, we sought to determine whether genome-wide changes in DNA methylation occur in the livers of offspring exposed to a maternal HF diet and a postweaning control diet. The liver was chosen because it is essential for maintaining metabolic homeostasis (22). We performed a genome methylation array to identify differentially methylated genes in 8-week-old postweaning control diet-fed offspring from HF diet-fed or control diet-fed dams. Differentially methylated genes were assessed in the offspring mouse genome to determine the epigenetic mechanism responsible for the maternal HF diet effects.

Materials and Methods

Animal Grouping and Treatments

All research procedures involving animals were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Peking Union Medical Hospital (Permit Number: MC-07-6004). Male and virgin female C57BL6/J mice were purchased from the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College (Beijing, China). All animals were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions. Mice were kept in a controlled environment (25 ± 1°C) under a 12-h light/dark cycle and allowed food and water ad libitum.

Five-week-old virgin females (n = 40) were divided into two groups at random. One group of mice was fed a standard AIN93G control diet (CON group, n = 20, Research Diets, Inc.; 16, 64, and 20% of calories from fat, carbohydrate, and protein, respectively), while the other group was fed a HF diet (n = 20; Research Diets, Inc.; 45, 35, and 20% of calories from fat, carbohydrate, and protein, respectively). Male mice were fed a normal diet throughout the experiment. After 4 weeks, female mice were housed overnight with males of the same age to mate at a ratio of 2:1 in each cage. The presence of a vaginal plug the following morning indicated the first day of pregnancy. During gestation and lactation, the diet scheme did not change. On postnatal day 21, one male pup was selected randomly from each dam. Male pups from control diet-fed dams were weaned onto the control diet (CON-CON, n = 10) or HF diet (CON-HF, n = 10). Meanwhile, male pups from HF diet-fed dams were weaned onto the control diet (HF-CON, n = 10) or HF diet (HF-HF, n = 10). This process created four groups of pups: CON-CON group, CON-HF group, HF-CON group, and HF-HF group. All animals were sacrificed at 8 weeks of age, and the livers were immediately collected and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at −80°C. The animal experiment timeline is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Timeline of animal experiment. CON-CON: control diet mother-post-weaning control diet; CON-HF, control diet mother-post-weaning high-fat diet; HF-CON, high-fat diet mother-post-weaning control diet; HF-HF, high-fat diet mother-post-weaning high-fat diet.

Body Weight, Fasting Blood Glucose, Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT), and Insulin Analysis

Body weight was measured at weaning time in mothers and 8 weeks of age in pups. Fasting blood glucose (Contour TS glucometer, Bayer, Hamburg, Germany) and plasma insulin (ELISA, Millipore, Billerica, MA) levels were measured at 8 weeks of age. Insulin sensitivity was assessed using the HOMA-IR as previously described (23). After 10 h of food deprivation, the 8-week-old offspring underwent OGTT, and the blood glucose concentrations were immediately measured with a glucometer at 0, 30, 60, and 120 min post gavage (2.0 g/kg). The area under the glucose tolerance curve (AUC) of the OGTT was calculated as previously described (23).

DNA Methylation Profiling Using Array

To determine the effect of maternal HF diet on DNA methylation in offspring livers, genomic DNA was extracted from the livers of HF-CON and CON-CON pups (n = 3 in each group, selected randomly from different dams) using a DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Fremont, CA). Samples of genomic DNA were sonicated into random fragments in a size range of ~100–500 bp. Immunoprecipitation of methylated DNA fragments (MeDIP) was performed using a mouse monoclonal anti-5-methylcytosine antibody (Diagenode). The total input and immunoprecipitated DNA were labeled with Cy3- and Cy5-labeled random 9-mers, respectively, and hybridized to an Arraystar Mouse ReqSeq Promoter Array (Arrarystar Inc., Rockville, MD), which contains 22,327 well-characterized RefSeq promoter regions [from ~-1,300 to +500 bp of the transcription start sites (TSSs)] totally covered by ~180,000 probes. Scanning was performed with an Agilent Scanner G2505C (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany).

Methylation Enrichment and Peak-Finding

The results were obtained using a sliding-window (750 bp) peak-finding algorithm provided by NimbleScan v2.5 (Roche NimbleGen). NimbleScan detects peaks by searching for at least two probes above a minimum cutoff p-value (–log10) of 2. Peaks within 500 bp of each other are merged. The M’ value was calculated for each probe to compare differentially enriched regions between the HF-CON and CON-CON groups as follows:

M’ = Average()−Average().

The differential enrichment peaks (DEPs) called by the NimbleScan algorithm were filtered according to the following criteria:

At least one of the two groups has a median (log2 MeDIP/Input) ≥0.3 and M’ > 0.

At least half of the probes in a peak may have a coefficient of variability (CV) ≤ 0.8 in both groups.

To separate strong CpG islands from weak CpG islands, promoters were categorized into three levels: high CpG promoters/regions (HCPs), intermediate CpG promoters/regions (ICPs), and low CpG promoters/regions (LCPs) (24).

Pathway Analysis

DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.7 [http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/ (25)] was used to perform Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway and Gene Ontology (GO) functional enrichment analyses for the differentially methylated genes (DMGs).

Bisulfite Sequencing PCR (BSP)

For validation of the methylation array, bisulfite conversion of genomic DNA from offspring livers in the four groups (n = 10 in each group) was conducted using a kit (Zymo Research, CA). The primers were designed using Methyl Primers Express software 1.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and are shown in Table 1. The resulting PCR products were purified using a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) and cloned into the pMD18-T vector (Takara, Shiga, Japan). Individual clones were grown, and plasmids were purified using a PureLink Miniprep Kit (Invitrogen, Thermo Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA). At least 10 clones from each mouse were selected and sequenced.

Table 1.

PCR primer for bisulfite sequencing.

| Gene | Accession number | Primer sequences (from 5′ to 3′) | Production size | CpG number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irs2 | NM_001081212 | F: 5′-TTTAAGGGTATTTTTGGTTTGG−3′ R: 5′-ACCATTCACTTATCAAATTCCC−3′ |

301 | 30 |

| Map2k4 | NM_001316367 | F: 5′-TGTTTTTTGATTTTTTTTTTGG−3′ R: 5′-AAAAACTTACAACCCCAAAACT−3′ |

439 | 7 |

Irs2, insulin receptor substrate 2; Map2k4, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4.

Quantitative Reverse-Transcription PCR

Total RNA from offspring livers in the four groups (n = 10 in each group) was isolated using a Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription was conducted with total RNA using the TaKaRa RT kit (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan). Real-time PCR was performed on an ABI 7900 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the comparative Ct method (2−ΔΔCt). The relative mRNA expression levels of target genes were normalized to Gapdh. The sequences of the primers used are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

qPCR primer.

| Gene | Accession number | Primer sequences (from 5′ to 3′) | Production size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Irs2 | NM_001081212 | F: 5′- CGAGTCAATAGCGGAGACCC−3′ R: 5′ CCCCTGAGACCCTACGGTAA−3′ |

119 |

| Map2k4 | NM_001316367 | F: 5′- TCTGTGAAAAGGCACAAAGTAAGC−3′ R: 5′- TCTCAGTCTCTCTATGTGTGGGT−3′ |

134 |

Irs2, insulin receptor substrate 2; Map2k4, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4.

Statistical Analysis

The results were statistically analyzed by Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). All values are presented as the mean ± SEM. Dam body weights were compared by Student's t test. Body weight, blood glucose, plasma insulin, HOMA-IR, methylation, and mRNA expression in offspring were analyzed by two-way ANOVA (maternal diet x offspring diet). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

HF Dams had Greater Body Weight

Dams in the HF group had higher body weights than those in the CON group at weaning time (23.33 ± 1.40 g vs. 19.17 ± 1.14 g, P < 0.01).

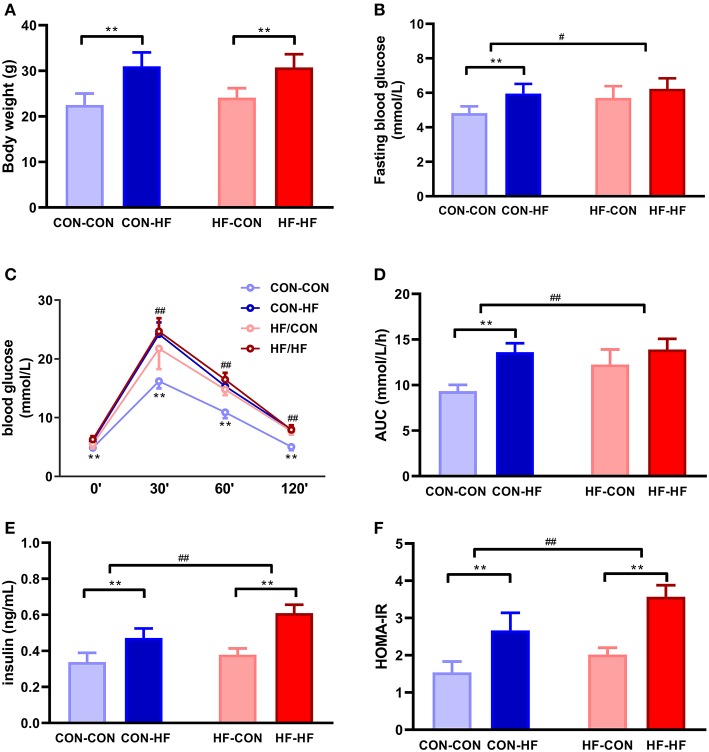

Maternal HF Diet Did Not Affect Body Weight in Male Mice

At 8 weeks of age, the mean body weight of mice in the CON-HF and HF-HF groups was significantly higher than that of CON-CON and HF-CON mice (P < 0.01, Figure 2A). There was no significant maternal HF diet effect on offspring body weight (P > 0.05, Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

The effect of maternal high-fat diet on metabolic variables of male mice offspring. (A) body weight at weaning; (B) fasting blood glucose; (C) oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT); (D) area under curve (AUC) in OGTT; (E) plasma insulin; (F) HOMA-IR. **P < 0.01 offspring diet effect; #P < 0.05; ##P < 0.01 maternal diet effect. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 10). CON-CON: control diet mother-post-weaning control diet; CON-HF, control diet mother-post-weaning high-fat diet; HF-CON, high-fat diet mother-post-weaning control diet; HF-HF, high-fat diet mother-post-weaning high-fat diet.

Male Mice From HF Dams Exhibited Glucose Intolerance and Insulin Resistance

Fasting blood glucose was at similar higher levels in all HF groups (P < 0.01, Figure 2B). Offspring from HF diet-fed dams displayed higher fasting blood glucose (P < 0.05, Figure 2B). The HF diet caused significant glucose intolerance in offspring from control diet-fed dams (P < 0.01, Figure 2C). In particular, offspring from HF diet-fed dams had higher blood glucose levels at 30, 60, and 120 min and greater AUCs during OGTTs (P < 0.01, Figures 2C,D). Even when they were fed with a control diet, offspring from HF diet-fed dams had higher blood glucose levels and AUCs (P < 0.01, Figures 2C,D). The postweaning HF diet interacted with the maternal HF diet to increase fasting plasma insulin levels and HOMA-IR (P < 0.01, Figures 2E,F).

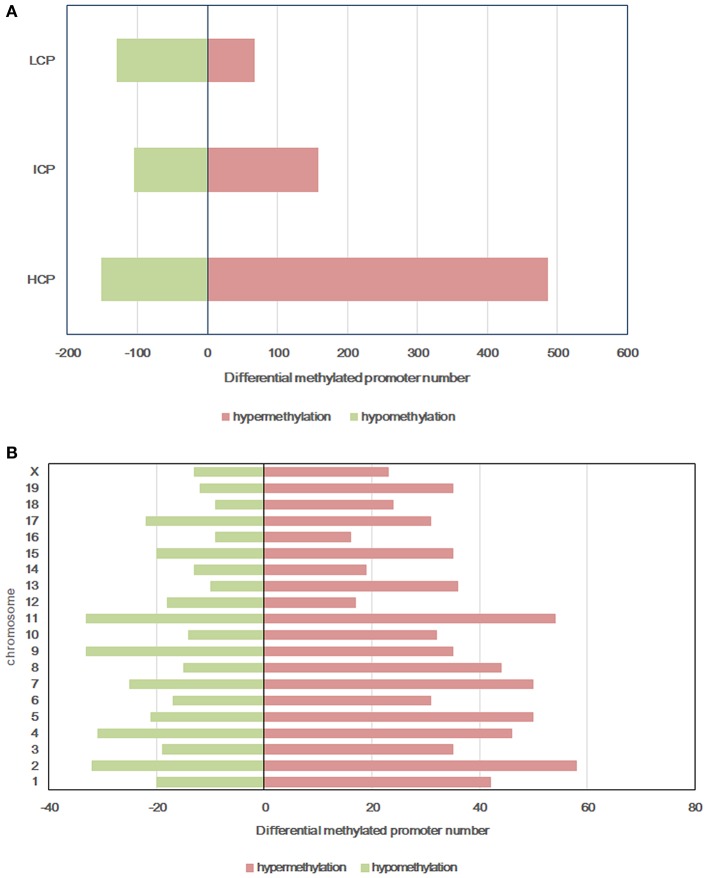

Intrauterine Environment of HF Damsaffects DNA Methylation Patterns in Male Mice

All microarray data have been deposited into the gene expression omnibus (GEO ID: GSE136814). To explore the mechanism of glucose intolerance and insulin resistance observed in the offspring from dams fed a HF diet, we performed methylation arrays on the livers of the HF-CON and CON-CON groups (n = 3). We found that a total of 1,099 differentially methylated regions (DMRs, 955 annotated genes) were identified on 20 chromosomes in the HF-CON group compared with the CON-CON group. Among these DMRs, 713 were hypermethylated and 386 were hypomethylated. Among the hypermethylated promoters, 487 (68.33%) were located in HCPs, 158 (22.1%) in ICPs, and 68 (9.5%) in LCPs. Among the hypomethylated promoters, 151 (39.1%) were located in HCPs, 105 (27.2%) in ICPs, and 130 (33.7%) in LCPs (Figure 3A). DMRs were mainly located on chromosomes 2, 4, 7, 9, and 11 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Differentially methylated promoters between HF-CON group and CON-CON group. (A) CpG density of differentially methylated promoters. (B) Chromosomal distribution of differentially methylated promoters. Red: differentially hypermethylated promoters; Green, differentially hypomethylated promoters. Classification of all promoters with high (HCP), intermediated (ICP), and low (LCP) CpG content.

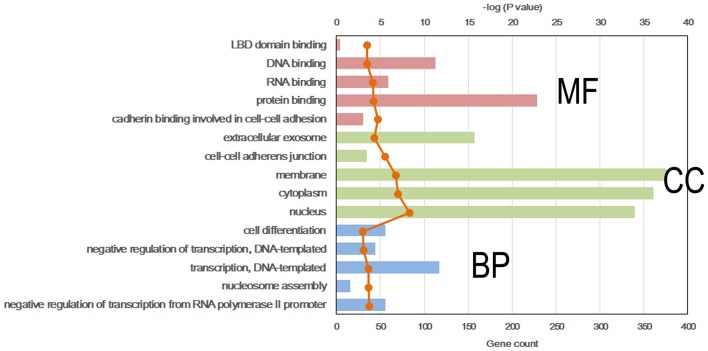

DMR-Related Gene Analysis

To further explore the molecular mechanism by which the offspring were exposed to a HF diet in an intrauterine environment, DMR-related genes were analyzed using GO functional analysis and KEGG enrichment analysis. Significantly enriched GO terms of DMR-related genes mainly participating in molecular function are LBD domain binding, DNA binding, RNA binding, protein binding, and cadherin binding involved in cell-cell adhesion (Figure 4, Supplemental Table 1). The top 25 KEGG pathways of DMGs are enriched in the adipocytokine signaling pathway, MAPK signaling pathway, pyruvate metabolism, toxoplasmosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Rap1 signaling pathway, regulation of actin cytoskeleton, protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum, dilated cardiomyopathy, pathways in cancer, citrate cycle, TGF-beta signaling pathway, systemic lupus erythematosus, biosynthesis of antibiotics, proteoglycans in cancer, RNA transport, signaling pathway regulating pluripotency of stem cells, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, Ras signaling pathway, FoxO signaling pathway, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, carbon metabolism, hippo signaling pathway, and gap junction (Figure 5, Supplemental Table 2).

Figure 4.

Top 5 significant GO term of differentially methylated genes in each classification. Red, molecular function (MF); Green, cellular component (CC); Blue, biological process (BP).

Figure 5.

Top 25 significant KEGG pathways of differentially methylated genes.

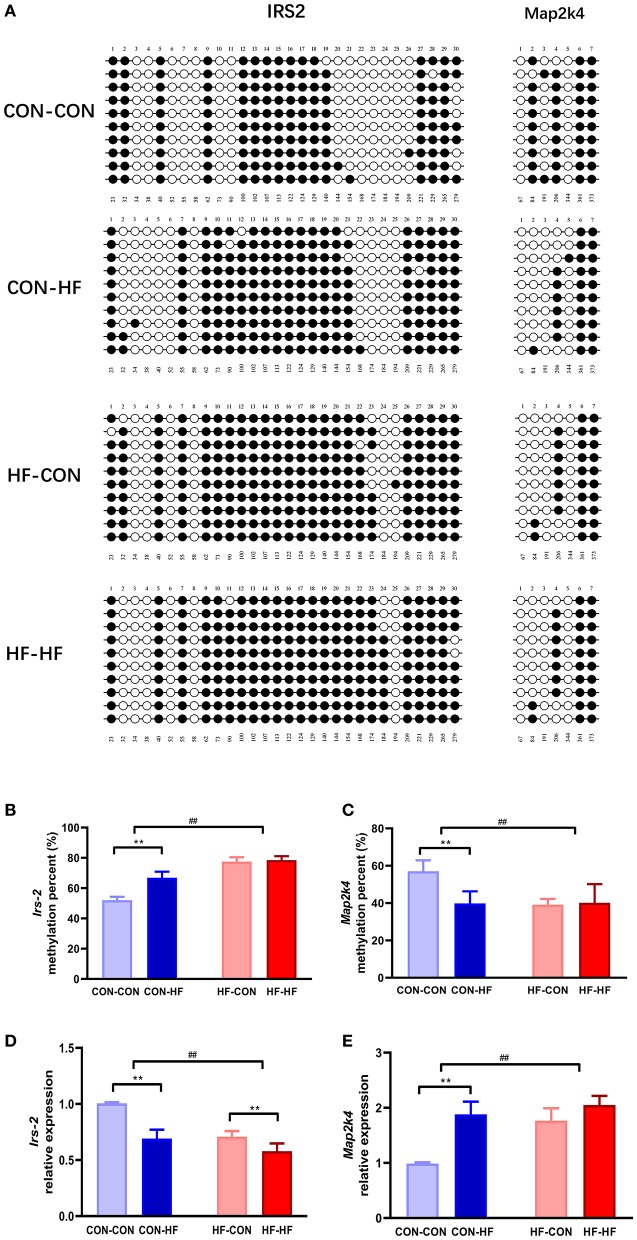

Overall Differential DNA Methylation of Irs2 and Map2k4

KEGG pathway analysis revealed that insulin signaling and MAPK may be mainly enriched among the DMGs regulated by pup livers from maternal HF diet-fed mice. To verify the methylation levels of candidate genes revealed by the methylation array, we further studied Irs2 and Map2k4, which are involved in the insulin signaling pathway and the MAPK pathway. As shown in Figures 6A,B, the Irs2 gene promoter region underwent a series of hypermethylations in all HF-fed groups, and this was more pronounced in pups from HF diet dams (P < 0.01). Map2k4 gene methylation was inhibited in CON-HF mice compared with CON-CON mice (P < 0.01, Figures 6A,C). The maternal HF diet had an inhibitory effect on Map2k4 gene methylation in offspring (P < 0.01, Figures 6A,C).

Figure 6.

Validation of methylation array using bisulphite sequencing. (A) Schematic diagram of bisulphite sequencing results on 30 CpG sites on Irs2 and 7 CpG on Map2k4. Open circles indicate unmethylated CpGs, and closed circles indicate methylated CpGs. Methylation ratio of Irs2 (B) and Map2k4 (C) in different groups. Relative gene expression of Irs2 (D) and Map2k4 (E) in different groups. **P < 0.01 offspring diet effect; ##P < 0.01 maternal diet effect. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 10). CON-CON, control diet mother-postweaning control diet; CON-HF, control diet mother-postweaning high-fat diet; HF-CON, high-fat diet mother-postweaning control diet; HF-HF, high-fat diet mother-postweaning high-fat diet.

Gene Expression of Irs2 and Map2k4

qPCR was applied to confirm the abnormal expression of Irs2 and Map2k4 in the livers from offspring exposed to a HF diet in utero or in adulthood. As illustrated in Figure 6D, the relative expression of Irs2 mRNA was decreased markedly by both a maternal HF diet and postweaning HF diet (P < 0.01). Map2k4 mRNA expression increased significantly in HF diet-fed mice (P < 0.01, Figure 6E). Furthermore, those exposed to maternal HF diet displayed increased Map2k4 mRNA levels (P < 0.01, Figure 6E).

Discussion

Our results showed that the postweaning HF diet increased body weight in mice. However, the maternal HF diet did not change pup body weight at 8 weeks of age. While some studies reported that HF diet-fed offspring exposed to a maternal HF diet had higher body weight in the adult period (26), other studies did not report any difference (27). This discrepancy may be because of different dietary components, fat sources or the strain and sex of the mice used. Our results revealed that both the maternal HF diet and postweaning HF diet led to glucose intolerance in male mice. Similar observations have been made in a previous study (26, 28–30). A systematic review of animal models found that male offspring exposed to a maternal HF diet independent of maternal obesity, birth weight or postweaning macronutrient intake had glucose intolerance (31). Additionally, a HF diet during fetal life, particularly if combined with the same insult during the suckling period, can induce the type 2 diabetes phenotype (32–34). Maternal obesity interacted with the postweaning HF diet to induce higher levels of glucose intolerance in offspring rodents (35, 36). This programming effect may have sex differences and lead to liver transcriptome changes (37). We also found that fasting insulin levels increased significantly both in mice exposed to the maternal HF diet and postweaning HF diet. In several studies on rats, offspring exposed in utero to a HF diet had increased fasting insulin levels (34, 38). In our study, both maternal HF diet and postweaning HF diet caused insulin resistance in pups. The discordance between an increased HOMA index and lack of an increase in plasma insulin levels may be because of the high fasting blood glucose levels in pups exposed to a maternal HF diet. Previous studies have reported that offspring exposed to a maternal HF diet in utero and/or postnatally developed manifestations of insulin resistance (29, 39).

A HF diet may affect the epigenetic status through several pathways. On the one hand, a HF diet can provoke inflammation and hormone secretion and alter DNA methylation (40). On the other hand, a HF diet can also act directly on epigenetic modification and methylation pathways. A short-term HF diet in healthy men induces widespread DNA methylation changes in the skeletal muscle. These changes were only partially reversed after 6–8 weeks (41). Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB)-induced weight loss is associated with the restoration of DNA methylation changes caused by obesity in skeletal muscle (42) and adipose tissue (43, 44). These DNA methylation changes involve pathways that control lipid metabolism and mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle (42), adipogenesis (43), and insulin-mediated glucose (44) uptake in adipose tissue.

A maternal HF diet may also induce DNA methylation changes in several metabolic genes (45) and their expression (37) in male offspring livers. In rats, the hepatic cell cycle inhibitor Cdkn1a was hypomethylated in offspring from HF diet-fed mothers (46). Increased methylation of the leptin promoter and decreased methylation of Ppar-α was also observed in the liver of female offspring from HF diet-fed dams (47). The maternal diet also increased Ppar-γ and liver X receptor α (LXRα) DNA methylation levels in male mouse livers (48). The present study used genomic DNA methylation technologies to examine DNA methylation profiles in mice exposed to a HF diet. First, to address whether maternal HF diet exposure induced methylation changes, we compared HF-CON and CON-CON mice. One thousand 99 DMRs were identified, and gene-associated DMRs clustered mainly in 25 pathways. We then compared DNA methylation in the identified regions among all four groups of mice to uncover the impact of HF diet intake regardless of timing. From these metabolic pathways, we concluded that the HF diet decreases Map2k4 DNA methylation and increases Irs2 DNA methylation, as all of the HF-CON, CON-HF, and HF-HF groups generally had lower Map2k4 DNA methylation and higher Irs2 DNA methylation than the CON-CON group.

Previous studies revealed that exposure to both undernutrition and overnutrition in utero induces gene-specific DNA methylation modification (49–52) in animal models. Several clinical studies revealed that genome-wide DNA methylation significantly changed in offspring born to overweight, obese or malnourished mothers (53–57). These DNA methylation modifications in offspring cord blood involve cardiovascular, inflammatory and apoptosis pathways (55, 57). Moreover, exposure to a maternal HF diet in utero might affect glucose and lipid metabolism of female offspring through epigenetic modifications to adiponectin and leptin genes even for multiple continuous generations (58). Exposure to normal diet in utero in the subsequent generations after HF diet exposure for three generations did not completely reverse the changes (59). However, maternal short-term transition from a HF diet to a normal diet before and during pregnancy and lactation without weight loss is not beneficial and even aggravated offspring obesity (60).

These observed methylation modifications affected by a maternal HF diet may result from several mechanisms during early life. In the perinatal period, de novo methyltransferases, such as Dnm3a and Dnm3b, block de novo methylation, which is important in normal development and disease (61). However, during the postweaning period, DNA methyltransferase DNMT1 carried out de novo and non-CG methylation (62). A HF diet in utero may affect these methyltransferases. Folate- and methyl-deficient diets in utero affect methyltransferase expression, including DNMT1 and DNMT3 (63–66). The HF diet affected the expression of DNMTs and their binding to the leptin promoter (67).

The molecular pathway analysis based on the KEGG database revealed that the differentially methylated Mapk gene was enriched. In our research, the Map2k4 gene was hypomethylated in pups exposed to a maternal HF diet. Map2k4 gene expression increased in the HF-CON, CON-HF, and HF-HF groups compared with expression in the CON-CON group. MAPKs consist of p38 MAPK, JNK, and ERK (68, 69). Activated MAPKs can inhibit expression of multiple targets, including insulin receptor substrate (IRS) proteins (70, 71) and resulting in the inhibition of insulin activity (72, 73).

Our results demonstrated that the Irs2 methylation level increased in offspring exposed to a HF diet in utero. Moreover, Irs2 gene expression was reduced in the livers of mice exposed to a HF diet as adults and in utero. IRS proteins are key components in the insulin signaling pathway (74, 75). Once stimulated by insulin, IRS is phosphorylated and then triggers intracellular signaling through the recruitment of proteins with the Src homology-2 domain, including PI3K, Grb-2, Nck, fyn, and Shp-2, among others (74, 76–78). Murine experiments reveal that targeted depletion of IRS-1 or IRS-2 leads to insulin resistance (79–82). Clinical and animal experiments prove that T2D patients and insulin-resistant rodents have defects in the phosphorylation of IRS proteins in vivo and in vitro (83, 84). This evidence proves that IRS defects are the molecular basis for insulin resistance. Hence, our results demonstrated that the maternal HF diet activated hepatic Irs2 methylation and reduced Irs2 gene expression. These findings suggest that the potent insulin resistance induced by a maternal HF diet may occur via activation of the key insulin signaling pathway molecule IRS, methylation, and reduced Irs2 expression.

Conclusions

In summary, we characterize the epigenetic alteration profile in the livers of postweaning control diet-fed offspring exposed to a maternal HF diet throughout gestation and lactation. In particular, decreases in Map2k4 DNA methylation and increases in Irs2 DNA methylation may play a central role in the livers of pups exposed to a maternal HF diet (Figure 7). More evidence needs to focus on the association of the epigenetic genome-wide status of the liver with the diabetes status in offspring. Furthermore, detailed studies exploring the function of candidate genes in the regulation of the liver are needed and could contribute to the prevention of the morbidity of metabolic-related diseases resulting from maternal HF diets.

Figure 7.

Epigenetic mechanism of high-fat diet in utero and adult on offspring. In utero expose to high-fat diet modify Irs2 and Map2k4 gene methylation and gene expression in offspring, led glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance.

Data Availability Statement

All microarray data have been deposited into the gene expression omnibus (GEO ID: GSE136814) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE136814).

Ethics Statement

All research procedures involving animals were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Peking Union Medical Hospital (Permit Number: MC-07-6004).

Author Contributions

XX conceived and designed the experiments. QZ, JZ, TW, and XW performed the experiments. MY, ML, and FP analyzed the data. XX contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools. QZ wrote the paper.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Beijing Compass Biotechnology Company for excellent technical assistance with the microarray experiments.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the grants from National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFC1309603), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFA0101002), Medical Epigenetics Research Center, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (2017PT31036 and 2018PT31021), the Non-profit Central Research Institute Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Nos. 2017PT32020 and 2018PT32001), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81170736, 81570715, 81870579, and 81870545), National Natural Science Foundation for Young Scholars of China (No. 81300649), China Scholarship Council foundation (201308110443), PUMC Youth Fund (33320140022), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and Scientific Activities Foundation for Selected Returned Overseas Professionals of Human Resources and Social Security Ministry.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2019.00871/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, Justice AE, Pers TH, Day FR, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature. (2015) 518:197–206. 10.1038/nature14177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raciti GA, Longo M, Parrillo L, Ciccarelli M, Mirra P, Ungaro P, et al. Understanding type 2 diabetes: from genetics to epigenetics. Acta Diabetol. (2015) 52:821–7. 10.1007/s00592-015-0741-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng Z, Zheng L, Almeida FA. Epigenetic reprogramming in metabolic disorders: nutritional factors and beyond. J Nutr Biochem. (2018) 54:1–10. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2017.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Dijk SJ, Tellam RL, Morrison JL, Muhlhausler BS, Molloy PL. Recent developments on the role of epigenetics in obesity and metabolic disease. Clin Epigenetics. (2015) 7:66. 10.1186/s13148-015-0101-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barker DJ. Maternal nutrition, fetal nutrition, and disease in later life. Nutrition. (1997) 13:807–13. 10.1016/S0899-9007(97)00193-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker DJ. The origins of the developmental origins theory. J Intern Med. (2007) 261:412–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01809.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oken E, Taveras EM, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards JW, Gillman MW. Gestational weight gain and child adiposity at age 3 years. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2007) 196:322.e321–328. 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.11.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roseboom T, de Rooij S, Painter R. The Dutch famine and its long-term consequences for adult health. Early Hum Dev. (2006) 82:485–91. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2006.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juonala M, Jaaskelainen P, Sabin MA, Viikari JS, Kahonen M, Lehtimaki T, et al. Higher maternal body mass index is associated with an increased risk for later type 2 diabetes in offspring. J Pediatr. (2013) 162:918–23.e911. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.10.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paliy O, Piyathilake CJ, Kozyrskyj A, Celep G, Marotta F, Rastmanesh R. Excess body weight during pregnancy and offspring obesity: potential mechanisms. Nutrition. (2014) 30:245–51. 10.1016/j.nut.2013.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bahari H, Caruso V, Morris MJ. Late-onset exercise in female rat offspring ameliorates the detrimental metabolic impact of maternal obesity. Endocrinology. (2013) 154:3610–21. 10.1210/en.2013-1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Q, Sun X, Xiao X, Zheng J, Li M, Yu M, et al. Dietary chromium restriction of pregnant mice changes the methylation status of hepatic genes involved with insulin signaling in adult male offspring. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0169889. 10.1371/journal.pone.0169889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucas A. Role of nutritional programming in determining adult morbidity. Arch Dis Child. (1994) 71:288–90. 10.1136/adc.71.4.288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barker DJ. The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. Bmj. (1990) 301:1111. 10.1136/bmj.301.6761.1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Cooper C, Thornburg KL. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N Engl J Med. (2008) 359:61–73. 10.1056/NEJMra0708473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marx V. Epigenetics: reading the second genomic code. Nature. (2012) 491:143–7. 10.1038/491143a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jang HS, Shin WJ, Lee JE, Do JT. CpG and Non-CpG methylation in epigenetic gene regulation and brain function. Genes. (2017) 8:148. 10.3390/genes8060148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soubry A, Murphy SK, Wang F, Huang Z, Vidal AC, Fuemmeler BF, et al. Newborns of obese parents have altered DNA methylation patterns at imprinted genes. Int J Obes. (2015) 39:650–7. 10.1038/ijo.2013.193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seki Y, Suzuki M, Guo X, Glenn AS, Vuguin PM, Fiallo A, et al. In utero exposure to a high-fat diet programs hepatic hypermethylation and gene dysregulation and development of metabolic syndrome in male mice. Endocrinology. (2017) 158:2860–72. 10.1210/en.2017-00334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cannon MV, Buchner DA, Hester J, Miller H, Sehayek E, Nadeau JH, et al. Maternal nutrition induces pervasive gene expression changes but no detectable DNA methylation differences in the liver of adult offspring. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e90335. 10.1371/journal.pone.0090335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moody L, Chen H, Pan YX. Postnatal diet remodels hepatic DNA methylation in metabolic pathways established by a maternal high-fat diet. Epigenomics. (2017) 9:1387–402. 10.2217/epi-2017-0066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bechmann LP, Hannivoort RA, Gerken G, Hotamisligil GS, Trauner M, Canbay A. The interaction of hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism in liver diseases. J Hepatol. (2012) 56:952–64. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Q, Sun X, Xiao X, Zheng J, Li M, Yu M, et al. Maternal chromium restriction induces insulin resistance in adult mice offspring through miRNA. Int J Mol Med. (2018) 41:1547–59. 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber M, Hellmann I, Stadler MB, Ramos L, Paabo S, Rebhan M, et al. Distribution, silencing potential and evolutionary impact of promoter DNA methylation in the human genome. Nat Genet. (2007) 39:457–66. 10.1038/ng1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, et al. DAVID: database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol. (2003) 4:P3. 10.1186/gb-2003-4-9-r60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Srinivasan M, Katewa SD, Palaniyappan A, Pandya JD, Patel MS. Maternal high-fat diet consumption results in fetal malprogramming predisposing to the onset of metabolic syndrome-like phenotype in adulthood. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. (2006) 291:E792–9. 10.1152/ajpendo.00078.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dias-Rocha CP, Almeida MM, Santana EM, Costa JCB, Franco JG, Pazos-Moura CC, et al. Maternal high-fat diet induces sex-specific endocannabinoid system changes in newborn rats and programs adiposity, energy expenditure and food preference in adulthood. J Nutr Biochem. (2018) 51:56–68. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2017.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunn GA, Bale TL. Maternal high-fat diet promotes body length increases and insulin insensitivity in second-generation mice. Endocrinology. (2009) 150:4999–5009. 10.1210/en.2009-0500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashino NG, Saito KN, Souza FD, Nakutz FS, Roman EA, Velloso LA, et al. Maternal high-fat feeding through pregnancy and lactation predisposes mouse offspring to molecular insulin resistance and fatty liver. J Nutr Biochem. (2012) 23:341–8. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong M, Zheng Q, Ford SP, Nathanielsz PW, Ren J. Maternal obesity, lipotoxicity and cardiovascular diseases in offspring. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2013) 55:111–6. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ainge H, Thompson C, Ozanne SE, Rooney KB. A systematic review on animal models of maternal high fat feeding and offspring glycaemic control. Int J Obes. (2011) 35:325–35. 10.1038/ijo.2010.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gniuli D, Calcagno A, Caristo ME, Mancuso A, Macchi V, Mingrone G, et al. Effects of high-fat diet exposure during fetal life on type 2 diabetes development in the progeny. J Lipid Res. (2008) 49:1936–45. 10.1194/jlr.M800033-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parente LB, Aguila MB, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA. Deleterious effects of high-fat diet on perinatal and postweaning periods in adult rat offspring. Clin Nutr. (2008) 27:623–34. 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cerf ME, Louw J. High fat programming induces glucose intolerance in weanling Wistar rats. Horm Metab Res. (2010) 42:307–10. 10.1055/s-0030-1248303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen H, Simar D, Morris MJ. Hypothalamic neuroendocrine circuitry is programmed by maternal obesity: interaction with postnatal nutritional environment. PLoS ONE. (2009) 4:e6259. 10.1371/journal.pone.0006259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uddin GM, Youngson NA, Doyle BM, Sinclair DA, Morris MJ. Nicotinamide mononucleotide. (NMN) supplementation ameliorates the impact of maternal obesity in mice: comparison with exercise. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:15063. 10.1038/s41598-017-14866-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lomas-Soria C, Reyes-Castro LA, Rodriguez-Gonzalez GL, Ibanez CA, Bautista CJ, Cox LA, et al. Maternal obesity has sex-dependent effects on insulin, glucose and lipid metabolism and the liver transcriptome in young adult rat offspring. J Physiol. (2018) 596:4611–28. 10.1113/JP276372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mitra A, Alvers KM, Crump EM, Rowland NE. Effect of high-fat diet during gestation, lactation, or postweaning on physiological and behavioral indexes in borderline hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. (2009) 296:R20–28. 10.1152/ajpregu.90553.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Volpato AM, Schultz A, Magalhaes-da-Costa E, Correia ML, Aguila MB, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA. Maternal high-fat diet programs for metabolic disturbances in offspring despite leptin sensitivity. Neuroendocrinology. (2012) 96:272–84. 10.1159/000336377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burdge GC, Hanson MA, Slater-Jefferies JL, Lillycrop KA. Epigenetic regulation of transcription: a mechanism for inducing variations in phenotype. (fetal programming) by differences in nutrition during early life? Br J Nutr. (2007) 97:1036–46. 10.1017/S0007114507682920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacobsen SC, Brons C, Bork-Jensen J, Ribel-Madsen R, Yang B, Lara E, et al. Effects of short-term high-fat overfeeding on genome-wide DNA methylation in the skeletal muscle of healthy young men. Diabetologia. (2012) 55:3341–9. 10.1007/s00125-012-2717-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barres R, Kirchner H, Rasmussen M, Yan J, Kantor FR, Krook A, et al. Weight loss after gastric bypass surgery in human obesity remodels promoter methylation. Cell Rep. (2013) 3:1020–7. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dahlman I, Sinha I, Gao H, Brodin D, Thorell A, Ryden M, et al. The fat cell epigenetic signature in post-obese women is characterized by global hypomethylation and differential DNA methylation of adipogenesis genes. Int J Obes. (2015) 39:910–9. 10.1038/ijo.2015.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Multhaup ML, Seldin MM, Jaffe AE, Lei X, Kirchner H, Mondal P, et al. Mouse-human experimental epigenetic analysis unmasks dietary targets and genetic liability for diabetic phenotypes. Cell Metab. (2015) 21:138–49. 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keleher MR, Zaidi R, Shah S, Oakley ME, Pavlatos C, El Idrissi S, et al. Maternal high-fat diet associated with altered gene expression, DNA methylation, and obesity risk in mouse offspring. PLoS ONE. (2018) 13:e0192606. 10.1371/journal.pone.0192606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dudley KJ, Sloboda DM, Connor KL, Beltrand J, Vickers MH. Offspring of mothers fed a high fat diet display hepatic cell cycle inhibition and associated changes in gene expression and DNA methylation. PLoS ONE. (2011) 6:e21662. 10.1371/journal.pone.0021662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ge ZJ, Luo SM, Lin F, Liang QX, Huang L, Wei YC, et al. DNA methylation in oocytes and liver of female mice and their offspring: effects of high-fat-diet-induced obesity. Environ Health Perspect. (2014) 122:159–64. 10.1289/ehp.1307047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu HL, Dong S, Gao LF, Li L, Xi YD, Ma WW, et al. Global DNA methylation was changed by a maternal high-lipid, high-energy diet during gestation and lactation in male adult mice liver. Br J Nutr. (2015) 113:1032–9. 10.1017/S0007114515000252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Plagemann A, Roepke K, Harder T, Brunn M, Harder A, Wittrock-Staar M, et al. Epigenetic malprogramming of the insulin receptor promoter due to developmental overfeeding. J Perinat Med. (2010) 38:393–400. 10.1515/jpm.2010.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vucetic Z, Kimmel J, Totoki K, Hollenbeck E, Reyes TM. Maternal high-fat diet alters methylation and gene expression of dopamine and opioid-related genes. Endocrinology. (2010) 151:4756–64. 10.1210/en.2010-0505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Begum G, Stevens A, Smith EB, Connor K, Challis JR, Bloomfield F, et al. Epigenetic changes in fetal hypothalamic energy regulating pathways are associated with maternal undernutrition and twinning. FASEB J. (2012) 26:1694–703. 10.1096/fj.11-198762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mahmood S, Smiraglia DJ, Srinivasan M, Patel MS. Epigenetic changes in hypothalamic appetite regulatory genes may underlie the developmental programming for obesity in rat neonates subjected to a high-carbohydrate dietary modification. J Dev Orig Health Dis. (2013) 4:479–90. 10.1017/S2040174413000238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guenard F, Deshaies Y, Cianflone K, Kral JG, Marceau P, Vohl MC. Differential methylation in glucoregulatory genes of offspring born before vs. after maternal gastrointestinal bypass surgery. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2013) 110:11439–44. 10.1073/pnas.1216959110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu X, Chen Q, Tsai HJ, Wang G, Hong X, Zhou Y, et al. Maternal preconception body mass index and offspring cord blood DNA methylation: exploration of early life origins of disease. Environ Mol Mutagen. (2014) 55:223–30. 10.1002/em.21827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morales E, Groom A, Lawlor DA, Relton CL. DNA methylation signatures in cord blood associated with maternal gestational weight gain: results from the ALSPAC cohort. BMC Res Notes. (2014) 7:278. 10.1186/1756-0500-7-278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tobi EW, Goeman JJ, Monajemi R, Gu H, Putter H, Zhang Y, et al. DNA methylation signatures link prenatal famine exposure to growth and metabolism. Nat Commun. (2014) 5:5592. 10.1038/ncomms6592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sharp GC, Lawlor DA, Richmond RC, Fraser A, Simpkin A, Suderman M, et al. Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain, offspring DNA methylation and later offspring adiposity: findings from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Int J Epidemiol. (2015) 44:1288–304. 10.1093/ije/dyv042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Block T, El-Osta A. Epigenetic programming, early life nutrition and the risk of metabolic disease. Atherosclerosis. (2017) 266:31–40. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Masuyama H, Mitsui T, Nobumoto E, Hiramatsu Y. The effects of high-fat diet exposure in utero on the obesogenic and diabetogenic traits through epigenetic changes in adiponectin and leptin gene expression for multiple generations in female mice. Endocrinology. (2015) 156:2482–91. 10.1210/en.2014-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fu Q, Olson P, Rasmussen D, Keith B, Williamson M, Zhang KK, et al. A short-term transition from a high-fat diet to a normal-fat diet before pregnancy exacerbates female mouse offspring obesity. Int J Obes.. (2016) 40:564–72. 10.1038/ijo.2015.236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Okano M, Bell DW, Haber DA, Li E. DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo methylation and mammalian development. Cell. (1999) 99:247–57. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81656-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pradhan S, Bacolla A, Wells RD, Roberts RJ. Recombinant human DNA. (cytosine-5) methyltransferase. I Expression, purification, and comparison of de novo and maintenance methylation. J Biol Chem. (1999) 274:33002–10. 10.1074/jbc.274.46.33002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ghoshal K, Li X, Datta J, Bai S, Pogribny I, Pogribny M, et al. A folate- and methyl-deficient diet alters the expression of DNA methyltransferases and methyl CpG binding proteins involved in epigenetic gene silencing in livers of F344 rats. J Nutr. (2006) 136:1522–7. 10.1093/jn/136.6.1522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kovacheva VP, Mellott TJ, Davison JM, Wagner N, Lopez-Coviella I, Schnitzler AC, et al. Gestational choline deficiency causes global and Igf2 gene DNA hypermethylation by up-regulation of Dnmt1 expression. J Biol Chem. (2007) 282:31777–88. 10.1074/jbc.M705539200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pogribny IP, Tryndyak VP, Bagnyukova TV, Melnyk S, Montgomery B, Ross SA, et al. Hepatic epigenetic phenotype predetermines individual susceptibility to hepatic steatosis in mice fed a lipogenic methyl-deficient diet. J Hepatol. (2009) 51:176–86. 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ding YB, He JL, Liu XQ, Chen XM, Long CL, Wang YX. Expression of DNA methyltransferases in the mouse uterus during early pregnancy and susceptibility to dietary folate deficiency. Reproduction. (2012) 144:91–100. 10.1530/REP-12-0006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xia L, Wang C, Lu Y, Fan C, Ding X, Fu H, et al. Time-specific changes in DNA methyltransferases associated with the leptin promoter during the development of obesity. Nutr Hosp. (2014) 30:1248–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guastamacchia E, Resta F, Triggiani V, Liso A, Licchelli B, Ghiyasaldin S, et al. Evidence for a putative relationship between type 2 diabetes and neoplasia with particular reference to breast cancer: role of hormones, growth factors and specific receptors. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord. (2004) 4:59–66. 10.2174/1568008043339965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Giovannucci E, Michaud D. The role of obesity and related metabolic disturbances in cancers of the colon, prostate, and pancreas. Gastroenterology. (2007) 132:2208–25. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Paz K, Hemi R, LeRoith D, Karasik A, Elhanany E, Kanety H, et al. A molecular basis for insulin resistance. Elevated serine/threonine phosphorylation of IRS-1 and IRS-2 inhibits their binding to the juxtamembrane region of the insulin receptor and impairs their ability to undergo insulin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. (1997) 272:29911–8. 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Birnbaum MJ. Turning down insulin signaling. J Clin Invest. (2001) 108:655–9. 10.1172/JCI200113714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Evans JL, Goldfine ID, Maddux BA, Grodsky GM. Oxidative stress and stress-activated signaling pathways: a unifying hypothesis of type 2 diabetes. Endocr Rev. (2002) 23:599–622. 10.1210/er.2001-0039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Evans JL, Maddux BA, Goldfine ID. The molecular basis for oxidative stress-induced insulin resistance. Antioxid Redox Signal. (2005) 7:1040–52. 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.White MF. The insulin signalling system and the IRS proteins. Diabetologia. (1997) 40 (Suppl. 2):S2–17. 10.1007/s001250051387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.White MF. The IRS-signaling system: a network of docking proteins that mediate insulin and cytokine action. Recent Prog Horm Res. (1998) 53:119–38. 10.1007/978-3-642-80481-6_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pawson T, Gish GD. SH2 and SH3 domains: from structure to function. Cell. (1992) 71:359–62. 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90504-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cherniack AD, Klarlund JK, Conway BR, Czech MP. Disassembly of Son-of-sevenless proteins from Grb2 during p21ras desensitization by insulin. J Biol Chem. (1995) 270:1485–8. 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hadari YR, Kouhara H, Lax I, Schlessinger J. Binding of Shp2 tyrosine phosphatase to FRS2 is essential for fibroblast growth factor-induced PC12 cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. (1998) 18:3966–73. 10.1128/MCB.18.7.3966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Patti ME, Sun XJ, Bruening JC, Araki E, Lipes MA, White MF, et al. 4PS/insulin receptor substrate (IRS)-2 is the alternative substrate of the insulin receptor in IRS-1-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. (1995) 270:24670–3. 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tobe K, Tamemoto H, Yamauchi T, Aizawa S, Yazaki Y, Kadowaki T. Identification of a 190-kDa protein as a novel substrate for the insulin receptor kinase functionally similar to insulin receptor substrate-1. J Biol Chem. (1995) 270:5698–701. 10.1074/jbc.270.11.5698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Withers DJ, Gutierrez JS, Towery H, Burks DJ, Ren JM, Previs S, et al. Disruption of IRS-2 causes type 2 diabetes in mice. Nature. (1998) 391:900–4. 10.1038/36116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Backhed F. 99th Dahlem conference on infection, inflammation and chronic inflammatory disorders: the normal gut microbiota in health and disease. Clin Exp Immunol. (2010) 160:80–4. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04123.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gao J, Katagiri H, Ishigaki Y, Yamada T, Ogihara T, Imai J, et al. Involvement of apolipoprotein E in excess fat accumulation and insulin resistance. Diabetes. (2007) 56:24–33. 10.2337/db06-0144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rask-Madsen C, Li Q, Freund B, Feather D, Abramov R, Wu IH, et al. Loss of insulin signaling in vascular endothelial cells accelerates atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E null mice. Cell Metab. (2010) 11:379–89. 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All microarray data have been deposited into the gene expression omnibus (GEO ID: GSE136814) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE136814).