Abstract

Exposure of lupus-prone female NZBWF1 mice to respirable crystalline silica (cSiO2), a known human autoimmune trigger, initiates loss of tolerance, rapid progression of autoimmunity, and early onset of glomerulonephritis. We have previously demonstrated that dietary supplementation with the ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) suppresses autoimmune pathogenesis and nephritis in this unique model of lupus flaring. In this report, we utilized tissues from prior studies to test the hypothesis that DHA consumption interferes with upregulation of critical genes associated with cSiO2-triggered murine lupus. A NanoString nCounter platform targeting 770 immune-related genes was used to assess the effects cSiO2 on mRNA signatures over time in female NZBWF1 mice consuming control (CON) diets compared to mice fed diets containing DHA at an amount calorically equivalent to human consumption of 2 g per day (DHA low) or 5 g per day (DHA high). Experimental groups of mice were sacrificed: (1) 1 d after a single intranasal instillation of 1 mg cSiO2 or vehicle, (2) 1 d after four weekly single instillations of vehicle or 1 mg cSiO2, and (3) 1, 5, 9, and 13 weeks after four weekly single instillations of vehicle or 1 mg cSiO2. Genes associated with inflammation as well as innate and adaptive immunity were markedly upregulated in lungs of CON-fed mice 1 d after four weekly cSiO2 doses but were significantly suppressed in mice fed DHA high diets. Importantly, mRNA signatures in lungs of cSiO2-treated CON-fed mice over 13 weeks reflected progressive amplification of interferon (IFN)- and chemokine-related gene pathways. While these responses in the DHA low group were suppressed primarily at week 5, significant downregulation was observed at weeks 1, 5, 9, and 13 in mice fed the DHA high diet. At week 13, cSiO2 treatment of CON-fed mice affected 214 genes in kidney tissue associated with inflammation, innate/adaptive immunity, IFN, chemokines, and antigen processing, mostly by upregulation; however, feeding DHA dose-dependently suppressed these responses. Taken together, dietary DHA intake in lupus-prone mice impeded cSiO2-triggered mRNA signatures known to be involved in ectopic lymphoid tissue neogenesis, systemic autoimmunity, and glomerulonephritis.

Keywords: omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, autoimmunity, nanostring, lung, kidney, systemic lupus erythematosus, silica, transcriptome

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a devastating multisystem autoimmune disease that primarily affects women of childbearing age and non-Caucasians (1, 2). SLE is initiated following breakdown of immune tolerance resulting from incompletely understood interactions between an individual's susceptibility genes and the environment. Early stage SLE involves a chronic autoimmune response, characterized by antibody production against self-antigens and the subsequent formation of immune complexes. The latter promote complement activation, cell death, chemokine/cytokine release, and mononuclear effector cell infiltration resulting in systemic inflammation and progressive organ damage that is often exacerbated by acute disease flares triggered by environmental stimuli. In the kidney, these responses can manifest as severe glomerulonephritis that often leads to end-stage renal failure. SLE is currently managed by decreasing disease symptoms in recently diagnosed persons and inhibiting further tissue damage in organs, such as the kidney, in long-term patients. Current therapies have multiple mechanisms of action including immunosuppression, lymphocyte depletion, and cytokine/chemokine neutralization. These approaches have serious limitations including unacceptable side effects, irreversible drug-induced organ damage, and high costs for new targeted monoclonal antibody/receptor therapies.

Murine models of SLE have been used to understand disease pathogenesis and show gradual accumulation of autoreactive B and T cells as well accumulation of autoantibodies followed by eventual onset of organ damage [reviewed in (3)]. Therefore, these models typify quiescent SLE prior to organ damage heralded by glomerulonephritis. However, flaring can be induced in these models and organ damage accelerated by injection of IFNα-expressing adenovirus (4–6), UV exposure (7, 8), and epidermal injury (9). Crystalline silica (cSiO2) is a respirable particle commonly encountered in occupations such as construction and mining that has been etiologically linked to SLE and other autoimmune diseases (10). Prior investigations in lupus-prone mice have demonstrated that airway exposure to cSiO2 rapidly accelerates the onset and progression of autoimmunity thus emulating flaring (11–14). We have determined that short-term cSiO2 instillation of female NZBWF1 mice triggers autoimmunity and glomerulonephritis 3 months earlier than vehicle-instilled controls (15, 16). Specifically, cSiO2 treatment mimics SLE flaring by initiating persistent sterile inflammation and cell death in the lung and initiating ectopic lymphoid structure (ELS) development. These tissue structures contain functional germinal centers that house B-cells, T-cells, follicular dendritic cells (FDC), and autoantibody-secreting plasma cells. Autoantibodies arising from ELS potentially form immune complexes with autoantigens formed in the lung following cSiO2 exposure that drive systemic autoimmunity and glomerulonephritis.

Recently, we utilized NanoString nCounter profiling to map dynamic transcriptome signature changes in cSiO2-exposed NZBWF1 mice (17). Dramatic upregulation mRNAs associated with interferon (IFN) activity, chemokine release, cytokine production, complement activation, and adhesion was observed in the lung during the first 2 months after cSiO2 treatment that corresponded closely with autoimmune pathogenesis. cSiO2 similarly induced robust changes in transcriptome signatures later in the kidney and in the spleen, to a lesser extent. Importantly, cSiO2-induced mRNA signatures consistent with the lung being central autoimmune nexus for initiating systemic autoimmunity and ultimately, glomerulonephritis.

Preclinical and clinical studies have shown that consumption of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), such as docosahexaenoic acid (C22:6 ω-3; DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (C20:5 ω-3; EPA), have the potential to prevent or treat many chronic inflammatory and autoimmune conditions [reviewed in (18)]. Western diets tend to exclude anti-inflammatory ω-3 PUFAs, and, more typically, contain high concentrations of proinflammatory ω-6 PUFAs, including linoleic acid (C18:2 ω-6; LA) and arachidonic acid (C20:4 ω-6; ARA) found in plant- and animal-derived lipids. Since Americans consume many times more ω-6s than ω-3s in the Western diet, their tissue phospholipid fatty acids skew heavily toward ω-3 insufficiency (19, 20). Several marine algae proficiently catalyze formation of DHA and EPA. Oily fish (e.g., salmon and mackerel) and small crustaceans (e.g., krill) bioconcentrate ω-3s into their membrane phospholipids by consuming marine algae (21). Individuals can increase DHA and EPA tissue incorporation, and correct ω-3 insufficiency, by consuming fish or dietary supplements with fish oil, krill oil, or microalgal oil. Intriguingly, ω-3 supplementation may be exploitable as a personalized medicine approach for individuals suffering from chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases to reduce dose and frequency of current therapies such as glucocorticoids that have myriad adverse effects.

Omega-3-rich fish oil supplementation has been shown to suppress autoantibody production, inflammatory gene expression, glomerulonephritis, and death from kidney failure in several different strains of lupus-prone mice (22–27), with DHA-enriched fish oil having the greatest potency (28, 29). Remarkably, we have found that dietary supplementation with DHA at realistic human equivalent Furthermore, we have demonstrated that pre-treating macrophages with DHA inhibited inflammasome activation by cSiO2 and linked this observation to suppression of NF-κB-driven proinflammatory genes (30). Understanding how DHA influences cSiO2-induced transcription signatures in vivo could provide insights into the underlying mechanisms by which ω-3s interfere with lupus flaring. In this investigation, we employed tissues from two recent published studies (17, 31) to test the hypothesis that DHA consumption interferes with upregulation of critical genes associated with cSiO2-triggered murine lupus. The results indicate that dietary DHA supplementation at clinically realistic levels impaired cSiO2-triggered expression of IFN- and chemokine-related genes that are likely to play critical roles in autoimmune pathogenesis and glomerulonephritis.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Diets

This investigation used materials and methods that have been more fully described in two previous published studies by our laboratory (17, 31). Experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Michigan State University (AUF #01/15-021-00). In both studies, female lupus-prone NZBWF1 mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were fed one of three diets that were based on the purified American Institute of Nutrition (AIN)-93G diet containing 70 g/kg fat (32). All diets contained 10 g/kg corn oil to ensure adequate basal essential fatty acids. The control diet (CON) contained 60 g/kg high-oleic safflower oil (Hain Pure Food, Boulder, CO). For DHA diets, high-oleic safflower oil was substituted with 10 g/kg (DHA low) or 25 g/kg (DHA high) microalgal oil containing 40% DHA (DHASCO, DSM Nutritional Products, Columbia MD). Resultant experimental diets contained 4 or 10 g/kg DHA, respectively, that equated, on a caloric basis, to human doses of 2 and 5 g per day, respectively. To prevent lipid oxidation, experimental diets were mixed weekly and stored at −20°C until use. Fresh feed was provided ad libitum to mice every 2 days.

Experimental Design

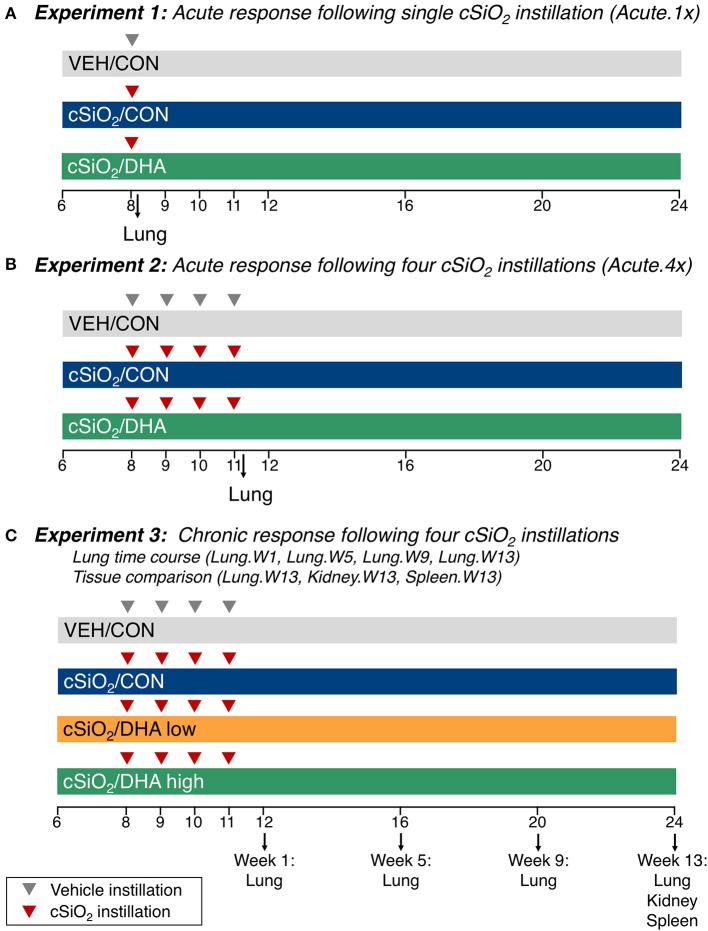

Experimental designs are depicted in Figure 1. For the acute studies (17), groups of 6 week old mice (n = 8) were fed CON or DHA high diets for the duration of the experiment. To model the acute response to one dose of cSiO2 (Acute.1x), a cohort of mice were anesthetized with 4% isoflurane and intranasally instilled with 1.0 mg cSiO2 (Min-U-Sil-5, 1.5–2.0 μm average particle size, Pennsylvania Sand Glass Corporation, Pittsburgh, PA) in 25 μl PBS or 25 μl PBS vehicle (VEH) (Figure 1A). To assess acute responses to short-term repeated exposure to cSiO2 (Acute.4x), a second cohort of mice received 1.0 mg cSiO2 or VEH once weekly for 4 weeks (Figure 1B). Cohorts were euthanized 24 h after the last cSiO2 instillation. Caudal lung lobes were removed, held in RNAlater (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE) for 16 h at 4°C, and then stored at −80°C until RNA isolation. For the time course study (31), groups of mice were treated with VEH or cSiO2 weekly for 4 weeks beginning at age 8 weeks, (Figure 1C). Afterward, cohorts were terminated at 1, 5, 9, and 13 weeks post final cSiO2 exposure and organs collected and stored in RNAlater as described above. Lungs were analyzed at 1 (Lung.W1), 5 (Lung.W5), 9 (Lung.W9), and 13 (Lung.W13) weeks post cSiO2 exposure; spleens (Spleen.W13) and kidneys (Kidney.W13) were analyzed at 13 weeks. These times correspond with pathological changes previously reported in NZBWF1 mice after cSiO2 exposure preceding and through glomerulonephritis onset (15, 16, 31). Fatty acid concentrations in erythrocytes were analyzed by gas liquid chromatogorphy at OmegaQuant (Sioux Falls, SD).

Figure 1.

Design of experiments. At 8 weeks of age, female NZBWF1 mice were dosed intranasally with 25 μl PBS (VEH) or 25 μl PBS containing 1.0 mg cSiO2 once [experiment 1 (A)] or weekly for 4 weeks [experiments 2 and 3 (B–C)]. In experiments 1 and 2, mice were fed either a control diet (CON) or a diet supplemented with 5 g/kg DHA. In experiment 3, mice were fed either CON diet or diets supplemented with 2 g/kg DHA (low) or 5 g/kg DHA (high). Cohorts (n = 8) of mice were euthanized and necropsied 1 day (experiment 1 and 2) following the only/final instillation or 12, 16, 20, or 24 weeks of age corresponding to 1, 5, 9, or 13 weeks post the final instillation (experiment 3). Tissues obtained for nCounter digital transcript counting (NanoString PanCancer Immune Profiling gene set) are indicated above. In this manuscript, the primary comparisons of interest are the DHA-supplemented groups vs. the CON diet groups in cSiO2-exposed mice within each experiment. Please see Bates et al. (17) for detailed presentation and analysis of the impact of cSiO2 on gene expression vs. vehicle-exposed mice.

Gene Expression Analysis With NanoString nCounter

Total RNA was isolated from lung, spleen, and kidney using TriReagent (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and RNeasy Mini Kits with DNase treatment (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA integrity (RIN values > 7.0) in samples was verified using an LabChip Gx Analyzer (Caliper Life Sciences, Waltham, MA). RNA (n = 7–8/group) was analyzed utilizing the nCounter Mouse PanCancer Immune Profiling Panel (catalog # 115000142, probe annotations available in Supplementary File 1) as described in detail previously (17) (Supplementary Figures 1–3). NanoString's software nSolver v3.0.22 was utilized for differential gene expression analyses as outlined previously (17) and depicted in Supplementary Figure 4. Statistically significant, differentially expressed genes were delineated as those with expression levels corresponding to a 1.5-fold change with respect to the corresponding CON diet group and a false discovery rate (Benjamini–Hochberg method) q < 0.05 (Supplementary Figure 5). nSolver differential expression analysis outputs from are contained in Supplementary File 2. BioVenn (33) or Venny v2.1 (34) was used to produce Venn diagrams of significant differentially expressed genes in cSiO2 groups.

Annotated gene sets, global, and directed significance scores were calculated for each pathway to ascertain the effects of treatments as previously described (17). Global scores estimate the cumulative evidence for the differential expression of genes for specific pathway, whereas directed significance scores reflect tendency for pathway genes to be over- or under-expressed collectively. Additionally, pathway Z scores were used to summarize data from a pathway's genes into a single score calculated as the first principal component of the pathway genes' normalized expression and standardized by Z scaling. ClustVis (35) was employed to carry out unsupervised hierarchical cluster analyses (HCC) and principal components analyses (PCA) using log2 transcript count data. Summary tables for all significance and pathway Z scores can be found in Supplementary Files 3, 4.

Spearman rank correlations were done to assess overall patterns in the gene expression profiles compared to percent CD45R+ (B cells) and CD3+ (T cells) in lung tissues as markers for ectopic lymphoid tissue development (31) and with the percent of ω-3 highly unsaturated fatty acids (HUFA; fatty acids with 20 or more carbons and three or more double bonds) in the total HUFA of erythrocytes (ω-3 HUFA score) (19). Correlation analysis was conducted using cor and corrplot functions in R (www.R-project.org). Spearman ρ values were determined utilizing individual sample pathway Z scores and phenotype data from mice from 1, 5, 9, or 13 weeks cohorts (31). A correlation was considered significant when ρ > 0.5 or <-0.5 and p < 0.05.

STRING database version 10.5 (http://string-db.org/) was used for network analyses for interactions among significant genes significant genes identified by the nSolver data analysis at a confidence level for associations set at ≥0.7. Clusters were identified using the Markov Cluster (MCL) algorithm with inflation parameter of 1.5. Networks produced by STRING were mapped with Cytoscape v3.0, with nodes indicating significant genes and edge width designating combined interaction score. Data for STRING-db networks and the predicted clusters, including protein-protein interactions and functional annotations can be found in Supplementary File 5.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Mouse lungs (n = 2 to 3 per group) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5 μm thick sections by the histology core at Michigan State University. The lung tissue sections were then deparaffinized by incubation for 1 h at 60°C, followed by immersion in xylene for 15 min with two changes. Tissues were rehydrated by sequential 10 min incubations in 100, 90, 70, and 50% (v/v) ethanol, followed by two 5 min incubations with deionized water. Epitope retrieval was accomplished by 10 min incubation in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0), followed by another 5 min wash in deionized water. Tissues were permeabilized by incubation for 15 min in 1% (v/v) goat serum containing 0.4% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS (PBST). Blocking of non-specific binding was done by incubation in 5% (v/v) goat serum in PBST for 30 min at room temperature. Detection of Mx1 and Oas2 proteins was accomplished by incubation with primary polyclonal antibodies (Mx1 catalog no. 1370-1-AP and Oas2 catalog no. 1927-1-AP; Proteintech, Rosemont, IL) diluted to 1:50 in 1% goat serum PBST and incubation overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber. Next, tissue sections were washed twice with 1% goat serum PBST for 10 min and then incubated with Alexa FluorTM 594 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) diluted to 1:1000 in 1% goat serum PBST at room temperature for 1–2 h in the dark. Sections were rinsed twice with PBST for 10 min, and the nuclei were counterstained by incubating overnight in ProlongTM gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen). Samples were stored in the dark until imaged using the Evos FL Auto 2 cell imaging system; 5 to 6 fields of view for each animal for each treatment group were inspected qualitatively.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay for Cxcl10

The concentration of Cxcl10 protein in whole lung homogenate was determined by ELISA using a the mouse Cxcl10 DuoSet kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, snap-frozen lungs were thawed, weighed, and homogenized in cold lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors. Homogenates were then centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were used for measuring Cxcl10 by ELISA. Total protein concentrations in the lung tissue homogenates were determined using the Pierce BCA protein assay kit (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA).

Results

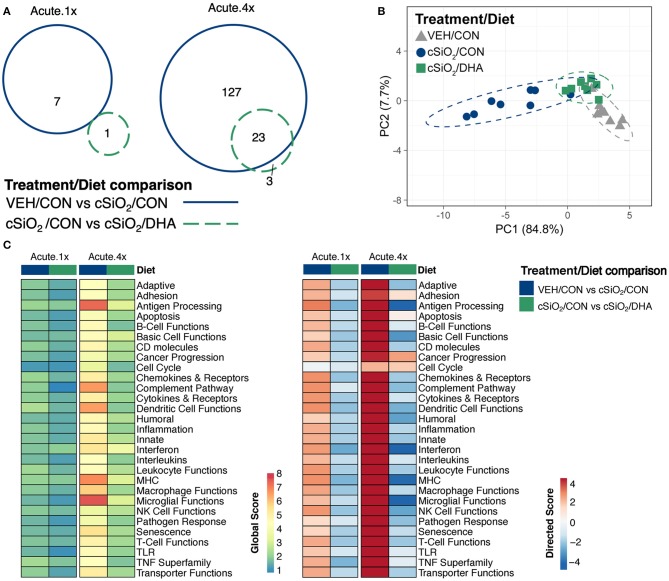

Acute immune gene responses 1 day after single (Acute.1x) or repeated (Acute.4x) intranasal dosing with cSiO2 were compared in mice fed CON or DHA high diets (Figures 1A,B). Transcriptomic analyses revealed that that 7 and 140 genes were differentially regulated (FDR q < 0.05, 1.5-fold change) in the lung 1 day after cSiO2 treatment in the Acute.1x and Acute.4x groups, respectively (Figure 2A). While DHA consumption did not affect cSiO2-induced changes in the single dose group, 23 genes were affected by DHA in mice treated with multiple doses of the particle. Principal component analysis of the Acute.4x responses indicated that DHA-fed cSiO2-treated mice clustered closely with the CON-fed VEH-treated mice, with both clusters being relatively distinct from CON-fed cSiO2-treated mice (Figure 2B). Heat mapping of global and directed significance scores showed that cSiO2-potentiated pathways were largely attenuated by DHA consumption (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Acute transcriptional response of immune-associated genes in DHA-supplemented mice that received either a single or four weekly instillations of cSiO2. (A) Venn diagram depicting overlap of genes differentially regulated by exposure to cSiO2 compared to those differentially regulated by DHA supplementation (FDR q < 0.05, 1.5-fold change). The overlap region indicates genes affected by cSiO2 exposure that were also altered by DHA supplementation. (B) PCA plot of differentially expressed genes for mice in the Acute.4x dosing group compared to a dosing-matched vehicle control group fed CON diet (VEH/CON). PC1 and PC2 are shown with 95% confidence interval bands (dashed ellipses). A PCA plot is not shown for the Acute.1x dosing group as only one gene was identified as differentially regulated by DHA for that dosing protocol. Hierarchical cluster analyses are provided in Supplementary Figure 6. (C) Global and directed significance scores for immune pathways were determined using nSolver (see section Materials and Methods) by comparing mice in the cSiO2/CON group to dosing-matched vehicle (VEH) controls fed CON diet or by comparing mice in the cSiO2/DHA group vs. cSiO2-exposed, CON-fed mice.

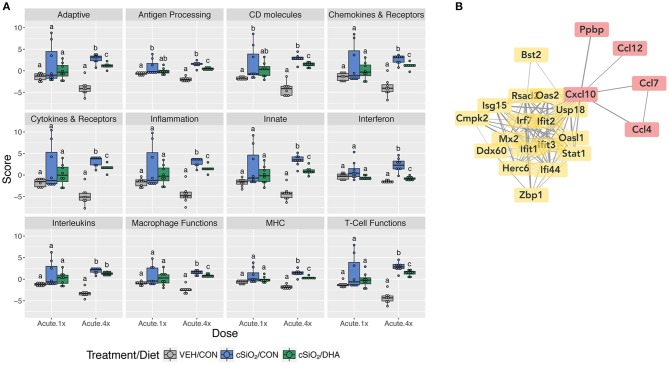

When gene expression pathway scores were calculated as the first principal component of the pathway genes' normalized expression and standardized by Z scaling, several cSiO2-induced immune pathways were found to be significantly downregulated by DHA supplementation in the Acute.4x group (Figure 3A; Supplementary Figure 7). Affected genes included those associated with inflammation; innate and adaptive immunity; IFN, chemokines, interleukins, cytokines; T-cell and macrophage function; and antigen processing and MHC expression. Network mapping showed that both IFN- and chemokine-related pathways were among the most prominently affected by DHA (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Pathway Z scores and network visualization for acute transcriptional response of immune-associated genes in DHA-supplemented mice that received either a single or four weekly instillations of cSiO2. (A) For cSiO2-exposed mice, gene expression pathway scores were calculated as the first principal component of the pathway genes' normalized expression and standardized by Z scaling. Immune pathway Z scores are presented as Tukey box-plots (n = 8) for select immune pathways of interest. Different letters indicate treatment/diet groups are significantly different (p < 0.05) as determined by the Steel-Dwass nonparametric test for all pairs. Heatmaps depicting individual pathway Z scores for all pathways captured by the NanoString PanCancer Immune Profiling gene panel are provided in Supplementary Figure 7. (B) Network interactions were modeled using the STRING database (string-db.org) with a minimum required interaction score ≥0.7, and clusters were identified using the Markov Cluster (MCL) algorithm with inflation parameter of 1.5. The network was visualized in Cytoscape, and edge widths reflect the combined interaction score (thicker edges indicate higher score). Note, a network for mice treated only once with cSiO2 (Acute.x1) was not made, as only one gene was significantly affected by DHA supplementation.

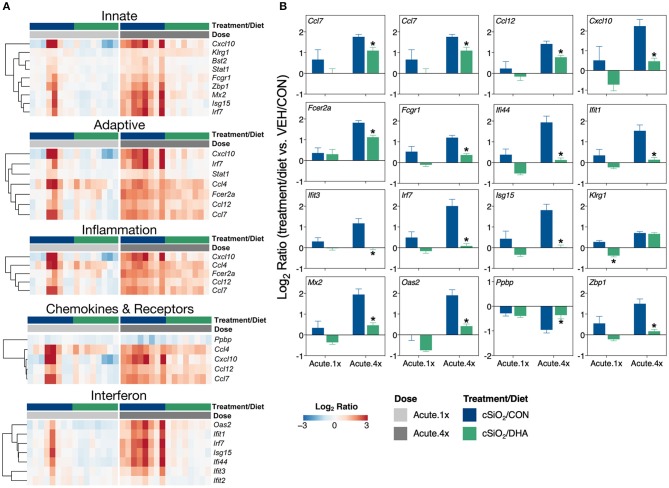

DHA's effects on representative pathway genes are depicted as heat maps and line plots in Figure 4. While only a few of the eight mice in the Acute.1x group responded strongly to cSiO2, the responses were very similar to those seen in all eight cSiO2-treated mice in the Acute.4x group (Figure 4A). DHA supplementation affected all cSiO2-induced genes by downregulation (Supplementary Figure 6). Consistent with the network analysis (Figure 3B), DHA significantly suppressed the upregulation of the IFN-related genes Zbp1, Mx2, Oas2, Ifit1, Ifit3, Ifit3, Irf7, Isg15, and Ifi44 and the chemokine-associated genes Ccl4, Cxcl10, Ccl7, Ccl12 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Comparison of DHA-responsive genes involved in immune response in lung tissues of mice that received either a single or four weekly instillations of cSiO2. Gene expression data are shown as log2 ratios for cSiO2-exposed mice fed either CON or DHA-supplement diets calculated with respect to dosing-matched, vehicle-exposed, CON-fed mice (VEH/CON, log2 ratio = 0). (A) For the selected immune pathways shown, heatmaps with unsupervised clustering (Euclidian distance method) by gene depict log2 expression values for all genes identified as significantly differentially expressed (FDR q < 0.05, 1.5-fold change) after a single (Acute.1x) or four repeated weekly doses (Acute.4x) of cSiO2. (B) The mean log2 ratio values + SEM for selected genes of interest are also shown. *, p<0.05 for DHA compared to CON diet as determined by nSolver statistical analyses (see Supplementary File 2 for test specifications and FDR-corrected q values).

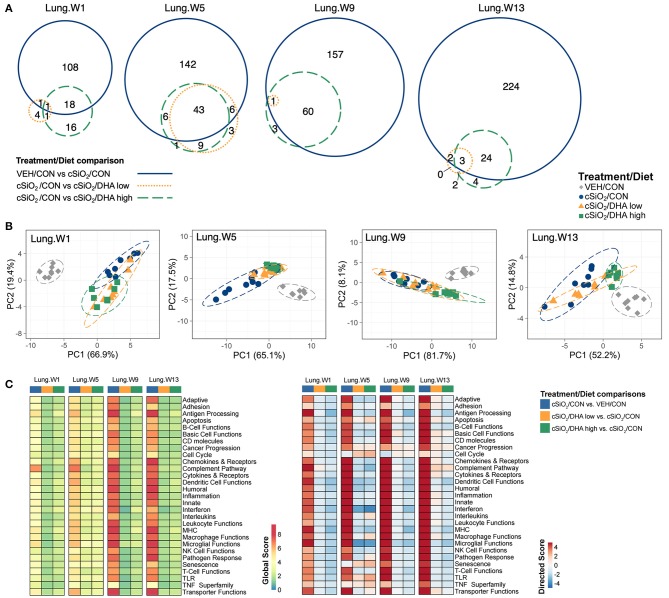

The effect of DHA low and high diets on chronic mRNA responses to short-term repeated cSiO2 were assessed in the lung over a 13 week period (Figure 1C). cSiO2 exposure elicited differential expression (FDR q < 0.05, 1.5-fold change) in the lung of 128, 197 genes, 218, and 253 genes at 1, 5, 9, and 13 weeks PI, respectively (Figure 5A). DHA low diet influenced 2, 49, 1, and 5 genes at these timepoints, respectively, whereas, the DHA high diet, affected 19, 49, 61, and 27 genes, respectively. Principal component analysis indicated strong separation of VEH-treated mice fed CON diet from all cSiO2-treated mice at all time points (Figure 5B). cSiO2-treated DHA low-fed mice responses clustered closely with cSiO2-treated DHA high-fed mice at 1 and 5 weeks PI, and with cSiO2-treated CON-fed mice at 9 and 13 weeks PI. Finally, cSiO2-treated DHA high-fed mice clustered distinctly from cSiO2-treated CON-fed mice at all time points. Hierarchal cluster analysis indicated that most of these genes were upregulated by cSiO2 treatment and suppressed by DHA (Supplementary Figure 8).

Figure 5.

Effect of DHA supplementation on cSiO2-induced transcriptional changes in lung tissues of mice 1, 5, 9, or 13 weeks post instillation. (A) Venn diagrams depicting overlap of genes differentially regulated by exposure to cSiO2 compared to those differentially regulated by supplementation with DHA low or DHA high diets (FDR q < 0.05, 1.5-fold change). The overlap regions indicate genes affected by cSiO2 exposure that were also altered by DHA supplementation. Hierarchical cluster analyses are provided in Supplementary Figure 9. (B) Principal components analyses of differentially expressed genes in lung tissues of DHA-supplemented mice exposed to cSiO2 at 1, 5, 9, or 13 weeks post instillation compared to time-matched vehicle (VEH/CON) and cSiO2-exposed (cSiO2/CON) control diets. PC1 and PC2 are shown with 95% confidence interval bands (dashed ellipses). (C) Global and directed significance scores for immune pathways were determined using nSolver (see section Materials and Methods) by comparing mice in the cSiO2/CON group to time-matched vehicle (VEH) controls fed CON diet or by comparing mice in the cSiO2/DHA low or the cSiO2/DHA high group vs. cSiO2-exposed, CON-fed mice.

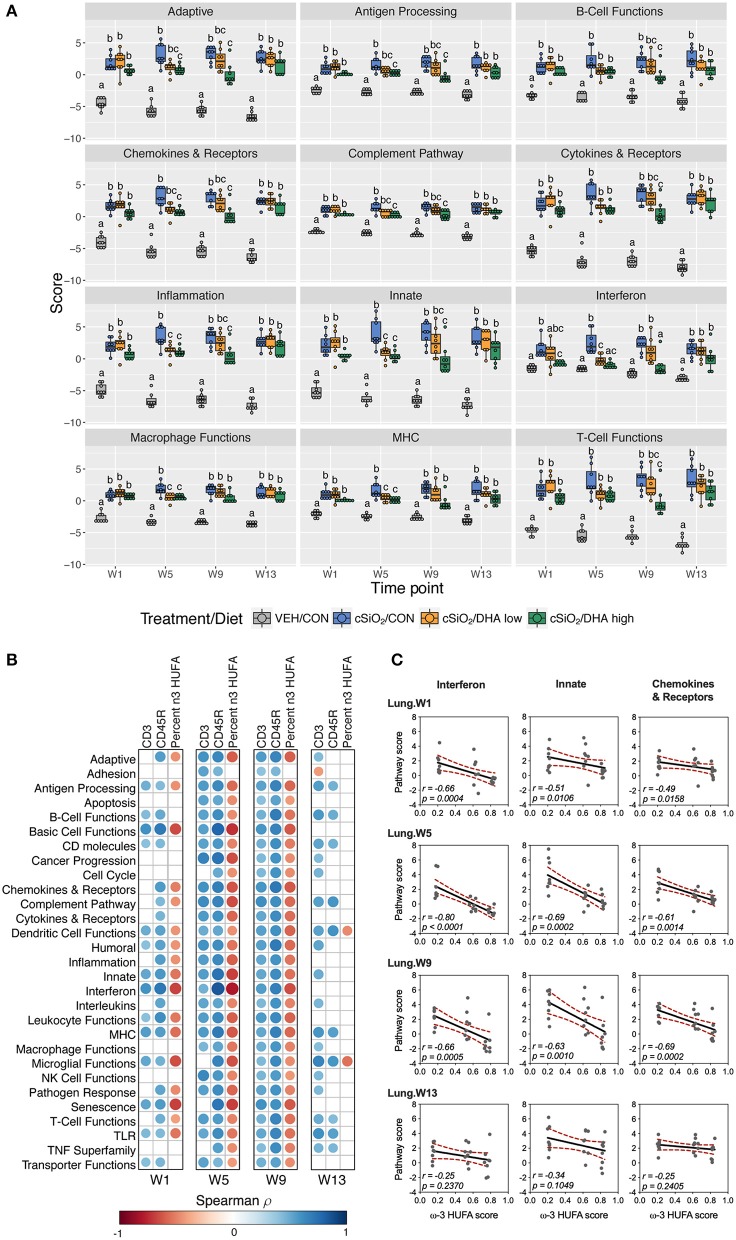

As observed in the Acute.4x study, DHA affected chronic expression of genes altered by cSiO2 exposure related to inflammation; innate and adaptive immunity; IFN, chemokines cytokines; B-cell, T-cell, and macrophage function; MHC expression and antigen processing; and complement (Figures 5C, 6A; Supplementary Figure 9). Most pathways in individual lungs of cSiO2-exposed lupus-prone mice time-dependently correlated with the presence of B cells and T cells (markers of ectopic lymphoid neogenesis) in the same lung tissues reported in the parent study (31) (Figures 6B,C). Significantly, most of these gene pathways were negatively correlated with ω-3 HUFA scores in erythrocytes from corresponding animals, with the strongest response noted for the IFN pathway at week 5.

Figure 6.

Lung tissue pathway Z scores and correlation analyses of immune-associated pathways. (A) Pathway Z scores are presented as Tukey box-plots (n = 8) for select immune pathways of interest. Different letters indicate treatment/diet groups are significantly different (p < 0.05) as determined by the Steel-Dwass non-parametric test for all pairs. Heatmaps depicting individual pathway Z scores for all pathways captured by the NanoString PanCancer Immune Profiling gene panel are provided in Supplementary Figure 9. (B) For all cSiO2-treated groups, spearman ρ values were calculated by correlating pathway Z scores with percent positive staining tissue (CD3 and CD45R) or the percent ω-3 HUFA in erythrocytes (ω-3 HUFA score). Significant correlation values (p<0.05) are represented as circles colored by the correlation value (blue, positive; red, negative); non-significant correlations are indicated by blank cells. (C) Scatter plots for pathway scores vs. the diet ω-3 HUFA score for selected pathways of interest. Linear regression lines with 95% confidence intervals (dashed red line) are shown along with the Spearman r value and p-value.

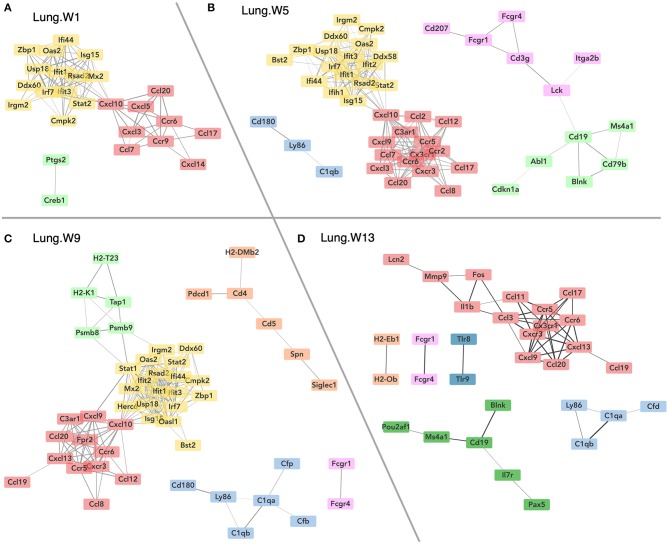

Figure 7 illustrates gene networks affected by dietary DHA supplementation during the course of cSiO2-induced disease development in the lungs. Consistent with the Acute.4x findings, DHA dramatically affected IFN- and chemokine-related genes at 1, 5, 9 weeks PI and, to a lesser extent, at 13 weeks PI. Also of note, expression of genes associated with the complement pathway (C1qb, C1qa, Cfd, and Cfb) was affected at weeks 5, 9, and 13 PI and with B-cell signaling and differentiation (Pou2af1, Ms4a1, Cd19, Pax5, and Blnk) at week 13 PI.

Figure 7.

Network visualization of genes significantly affected by DHA supplementation in lung tissues obtained 1 (A), 5 (B), 9 (C), or 13 (D) weeks post instillation with cSiO2. Network interactions for genes differentially regulated by either DHA low or DHA high supplementation at each time point were modeled using the STRING database (string-db.org) with a minimum required interaction score ≥0.7, and clusters were identified using the Markov Cluster (MCL) algorithm with inflation parameter of 1.5. The network was visualized in Cytoscape, and edge widths reflect the combined interaction score (thicker edges indicate higher score).

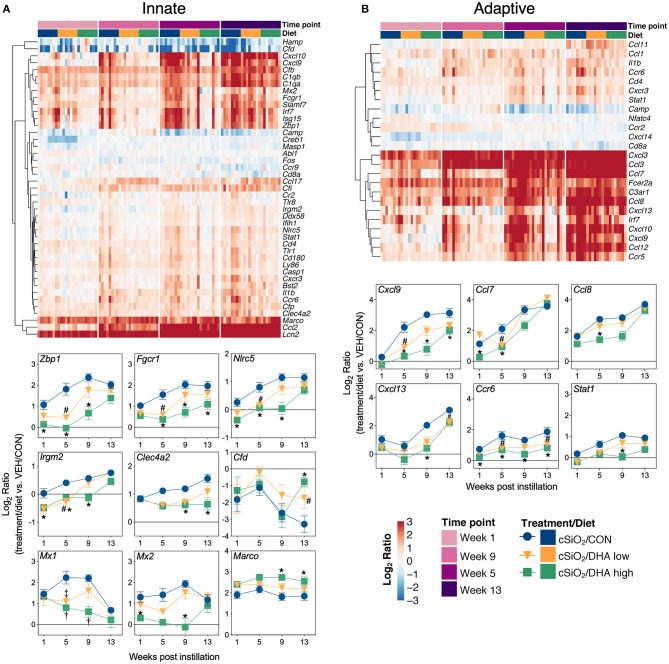

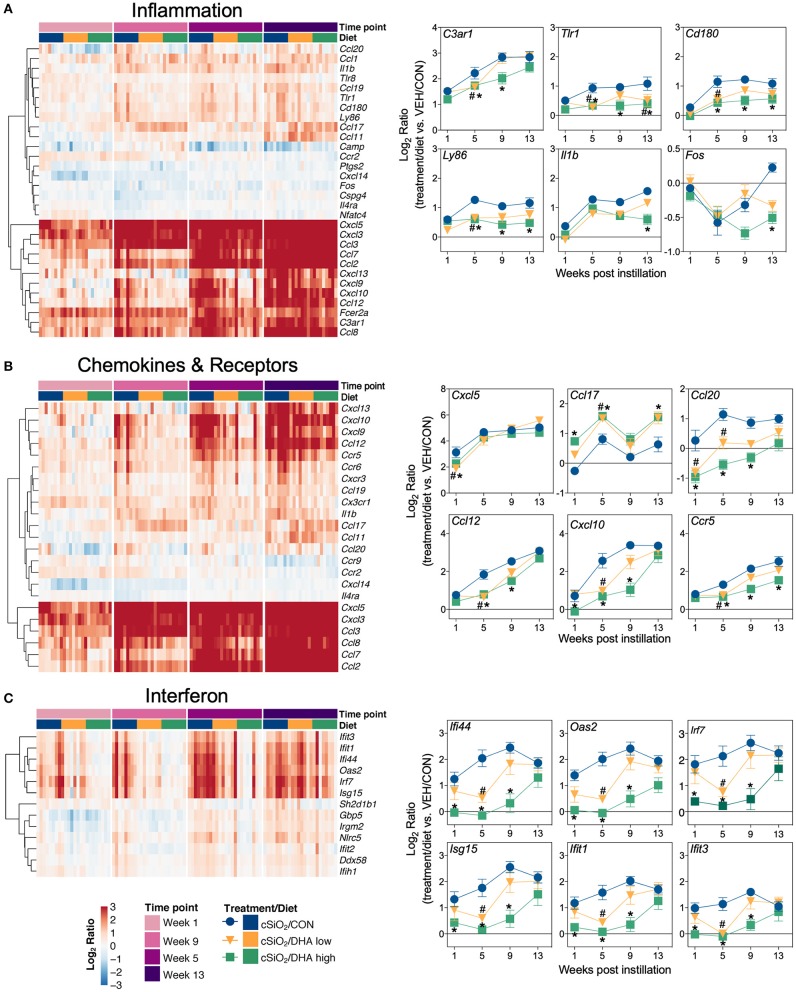

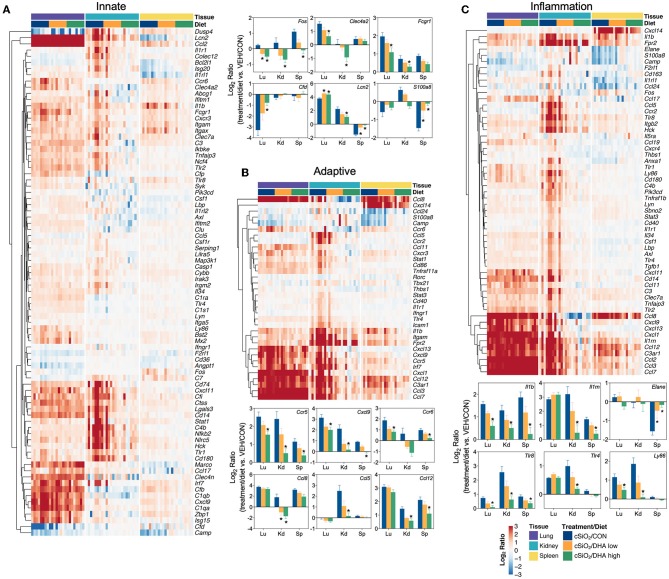

Heat maps and line plots as a function of time were constructed for representative genes associated with innate and adaptive immunity (Figures 8A,B) and with inflammation, IFN, and chemokines (Figures 9A–C). Particularly striking was the impact of DHA on IFN and chemokine genes, which were among the earliest and most highly suppressed. Specifically, consumption of the DHA low diet significantly suppressed cSiO2-induced gene expression at 1 week post installation (PI) and/or 5 weeks PI (e.g., Ccl12, Ccl20, Cxcl10, Oas2, Isg15, and Ifit1), whereas effects of the DHA high diet were longer lasting with significant effects also being observed at 9 weeks PI (Mx2, Cxcl10, Ccl12, Ifi44, Oas2, Ift1) and 13 weeks PI (e.g., Il1b, Fgcr1, Cxcl9).

Figure 8.

Time course of DHA-responsive genes associated with innate and adaptive immune pathways in lung tissues of mice 1, 5, 9, or 13 weeks post instillation with cSiO2. Gene expression data were obtained using the NanoString PanCancer Immune Profiling gene panel and are shown as log2 ratios for cSiO2-exposed mice fed CON, DHA low, or DHA high diets calculated with respect to time-matched, vehicle-exposed, CON-fed controls (VEH/CON; log2 ratio = 0). For innate (A) or adaptive (B) immune pathways, heatmaps with unsupervised clustering (Euclidian distance method) by gene depict log2 expression values for all genes identified as significantly differentially expressed (FDR q < 0.05, 1.5-fold change) at any one of the indicated time points. The mean log2 ratio values ± SEM for selected genes of interest are also shown. *p < 0.05 for DHA high compared to CON diet and #p < 0.05 for DHA low compared to CON diet as determined by nSolver statistical analyses (see Supplementary File 2 for test specifications and FDR-corrected q-values). †p < 0.05 for DHA high compared to CON diet and ‡p < 0.05 for DHA low compared to CON diet as determined by non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test (for Mx1 only).

Figure 9.

Time course of DHA-responsive genes associated with inflammation, chemokines & receptors, or immune pathways in lung tissues of mice 1, 5, 9, or 13 weeks post instillation with cSiO2. Gene expression data were obtained using the NanoString PanCancer Immune Profiling gene panel and are shown as log2 ratios for cSiO2-exposed mice fed CON, DHA low or DHA high diets calculated with respect to time-matched, vehicle-exposed, CON-fed controls (VEH/CON; log2 ratio = 0). For inflammation (A), chemokines and receptors (B), or interferon (C) pathways, heatmaps with unsupervised clustering (Euclidian distance method) by gene depict log2 expression values for all genes identified as significantly differentially expressed (FDR q < 0.05, 1.5-fold change) at any one of the indicated time points. The mean log2 ratio values ± SEM for selected genes of interest are also shown. *p < 0.05 for DHA high compared to CON diet and #p < 0.05 for DHA low compared to CON diet as determined by nSolver statistical analyses (see Supplementary File 2 for test specifications and FDR-corrected q values).

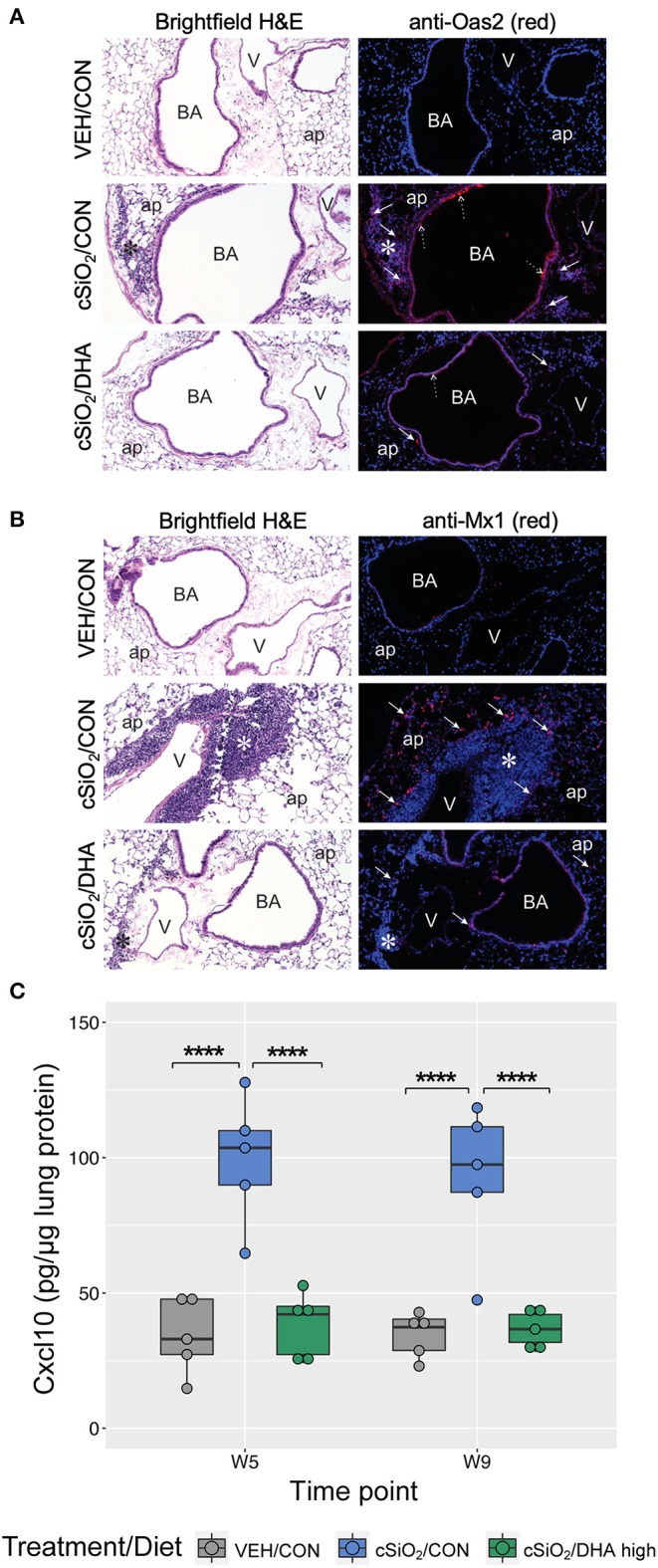

Immunofluorescence microscopy of lung tissues of mice obtained a 9 wk PI with cSiO2 revealed increased expression of Oas2 protein in ectopic lymphoid tissues and the airway epithelium, whereas dietary supplementation with DHA appeared to suppress expression of Oas2 at these sites (Figure 10A). Similarly, DHA supplementation suppressed the over-expression of Mx1 protein in the alveolar parenchyma triggered by cSiO2 exposure (Figure 10B). Of note, while Mx1 gene expression was induced by cSiO2 and then repressed by DHA, these changes in gene expression were not statistically significant as determined by the nSolver data analysis workflow. This result was likely due to failure of the mean to meet the threshold (10× background signal) for some treatment groups resulting in the use of the much less powerful Wald test. Separate analysis using the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test (GraphPad Prism, San Diego, CA) suggested that DHA supplementation indeed suppressed Mx1 expression induced by silica treatment at 5 and 9 weeks post installation (Figure 8A), a determination that agrees with the immunofluorescence microscopy results (Figure 10B). Lastly, measurement of Cxcl10 protein (also known as interferon gamma protein 10 (IP-10) or small-inducible cytokine B10) in lung homogenate using a standard ELISA revealed a profound 3-fold increase in its expression in tissues of cSiO2-exposed mice at both 5 and 9 weeks PI (Figure 10C). Remarkably, dietary supplementation with DHA entirely blocked that response such at Cxcl10 expression was not different from VEH/CON mice.

Figure 10.

Immunofluorescence detection of interferon-responsive genes Oas2 and Mx1 in lung tissues at 9 weeks post instillation with cSiO2 and expression of Cxcl10 in lung homogenates. (A,B) Representative light photomicrographs depict H&E-stained lung sections from VEH/CON, cSiO2/CON, and cSiO2/DHA high groups at 9 wk post-installation, while representative fluorescence microscopy images depict immunofluorescence staining of the same tissues for either Oas2 (A) or Mx1 (B) proteins (red channel) and Hoechst stain for nuclei (blue channel). For (A), Oas2-expressing cells are apparent in the ectopic lymphoid tissue (solid arrow) and the airway epithelium (dashed arrow). For (B), Mx1-expressing cells are apparent in the alveolar parenchyma (solid arrow). ap, alveolar parenchyma; BA, bronchiolar airway; V, blood vessel, *, ectopic lymphoid tissues; solid arrow, MX1-positive staining cells in the alveolar parenchyma. (C) Expression values for Cxcl10 protein in lung homogenates are shown as Tukey box-plots (n = 5). ****p < 0.0001 for comparisons among treatment groups within each time point as determined by two-way ANOVA (main effect of time point p = 0.6785; main effect of treatment group p < 0.0001; interaction p = 0.8908).

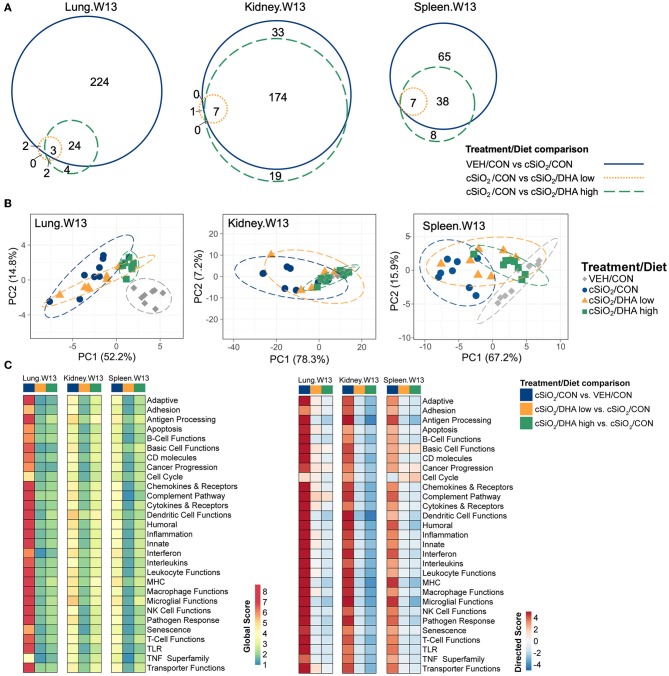

The effects of DHA supplementation on cSiO2-induced transcriptional changes were compared in lung, kidney and spleen tissues of mice at 13 weeks PI (Figure 11A; Supplementary Figure 10). Consumption of the DHA high diet influenced 11 percent of cSiO2-affected genes in the lung at this timepoint, while in the kidney and spleen, 85 and 59 percent of the induced transcriptomes were modulated, respectively. Many fewer cSiO2-altered genes in the lung (1%), kidney (3%), and spleen (5%) were affected in the mice fed the DHA low diet. Principal component analyses of the kidney indicated close associations among VEH/CON, cSiO2/DHA low, and cSiO2/DHA high groups as compared to cSiO2/CON group (Figure 11B). In the spleen, there were substantial overlaps between the VEH/CON and cSiO2/DHA high groups and between the cSiO2/DHA low and cSiO2/CON groups.

Figure 11.

Effect of DHA supplementation on cSiO2-induced transcriptional changes in lung, kidney or spleen tissues of mice 13 weeks post instillation. (A) Venn diagrams depicting overlap of genes differentially regulated by exposure to cSiO2 compared to those differentially regulated by supplementation with DHA low or DHA high diets (FDR q < 0.05, 1.5-fold change). The overlap regions indicate genes affected by cSiO2 exposure that were also altered by DHA supplementation. Hierarchical cluster analyses are provided in Supplementary Figure 10. (B) Principal components analyses of differentially expressed genes compared to tissue-matched vehicle control (VEH/CON) and cSiO2-exposed (cSiO2/CON) control diets. PC1 and PC2 are shown with 95% confidence interval bands (dashed ellipses). (C) Global and directed significance scores for immune pathways were determined using nSolver (see section Materials and Methods) by comparing mice in the cSiO2/CON group to dosing-matched vehicle (VEH) controls fed CON diet or by comparing mice in the cSiO2/DHA low or the cSiO2/DHA high group vs. cSiO2-exposed, CON-fed mice.

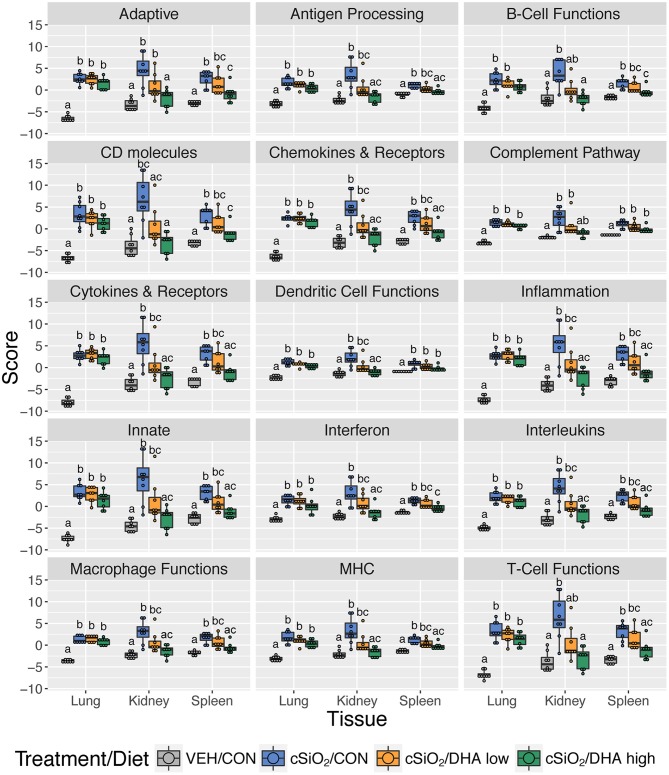

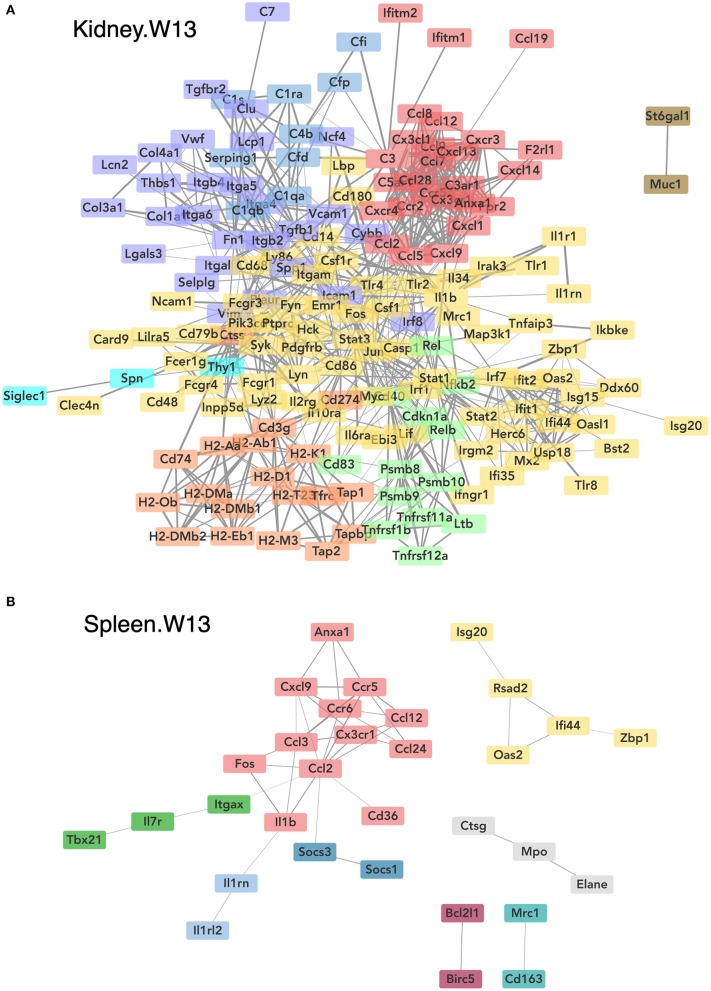

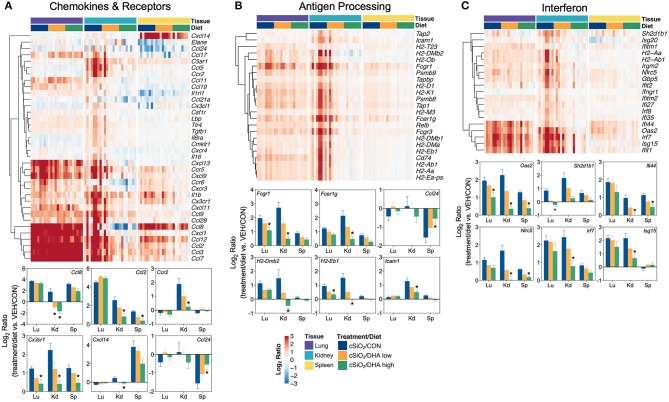

Consistent with DHA's effects in the lung in earlier weeks, its supplementation affected a broad array of cSiO2-induced pathways in the kidney and spleen at week 13 (Figures 11C, 12, 13). Network analysis revealed that DHA had robust effects on critical genes associated with glomerulonephritis including those related to IFN signaling (e.g., Irf7, Ifit1, Oas2, Isg15); cytokines and chemokines (e.g., Ccl8, Ccl2, Ccr2, Cx3cr1); and antigen processing and MHC (e.g., H2-Dmb2, Fcgr1, Fcer1g, H2-Eb1) (Figure 13A). Lastly, heat mapping and line plotting revealed that DHA dose-dependently suppressed induction of many genes in the kidney associated with innate and adaptive immunity and inflammation (Figure 14), and chemokines, IFN and antigen processing (Figure 15), whereas the effects were much more modest in the spleen with only a few genes uniquely affected by DHA in this tissue (e.g., Elane and Ccl124).

Figure 12.

Effect of DHA supplementation on selected immune pathways in lung, kidney and spleen tissues of mice 13 weeks post instillation. Mice fed either CON, DHA low, or DHA high diets received four repeated weekly doses of cSiO2 via intranasal instillation. Gene expression was determined by nCounter digital transcript counting in lung, kidney or spleen tissues obtained 13 weeks post instillation. Pathway Z scores are presented as Tukey box-plots (n = 8) for select immune pathways of interest. Different letters indicate treatment/diet groups are significantly different (p < 0.05) as determined by the Steel-Dwass non-parametric test for all pairs. Heatmaps depicting individual pathway Z scores for all pathways captured by the NanoString PanCancer Immune Profiling gene panel are provided in Supplementary Figure 11.

Figure 13.

Network visualization of genes significantly affected by DHA supplementation in kidney (A) or spleen (B) tissues obtained 13 weeks post instillation with cSiO2. Network interactions for genes differentially regulated by either DHA low or DHA high supplementation at each time point were modeled using the STRING database (string-db.org) with a minimum required interaction score ≥0.7, and clusters were identified using the Markov Cluster (MCL) algorithm with inflation parameter of 1.5. The network was visualized in Cytoscape, and edge widths reflect the combined interaction score (thicker edges indicate higher score).

Figure 14.

Comparison of DHA-responsive genes associated with innate, adaptive, and inflammation immune pathways in lung, kidney, or spleen tissues 13 weeks post instillation with cSiO2. Gene expression data were obtained using the NanoString PanCancer Immune Profiling gene panel and are shown as log2 ratios for cSiO2-exposed mice fed CON, DHA low or DHA high diets calculated with respect to tissue-matched, vehicle-exposed, CON-fed controls (VEH/CON; log2 ratio = 0). For the innate (A), adaptive (B), and inflammation (C) pathways, heatmaps with unsupervised clustering (Euclidian distance method) by gene depict log2 expression values for all genes identified as significantly differentially expressed (FDR q < 0.05, 1.5-fold change) in any one of the indicated tissues. The mean log2 ratio values + SEM for selected genes of interest are also shown. *p < 0.05 for DHA high compared to CON diet (see Supplementary File 2 for test specifications and FDR-corrected q-values).

Figure 15.

Comparison of DHA-responsive genes associated with chemokines & receptors, antigen processing and interferon immune pathways in lung, kidney, or spleen tissues 13 weeks post instillation with cSiO2. Gene expression data were obtained using the NanoString PanCancer Immune Profiling gene panel and are shown as log2 ratios for cSiO2-exposed mice fed CON, DHA low, or DHA high diets calculated with respect to tissue-matched, vehicle-exposed, CON-fed controls (VEH/CON; log2 ratio = 0). For the chemokines & receptors (A), antigen processing (B), and interferon (C) pathways, heatmaps with unsupervised clustering (Euclidian distance method) by gene depict log2 expression values for all genes identified as significantly differentially expressed (FDR q <0 .05, 1.5-fold change) in any one of the indicated tissues. The mean log2 ratio values + SEM for selected genes of interest are also shown. *p < 0.05 for DHA high compared to CON diet (see Supplementary File 2 for test specifications and FDR-corrected q-values).

Discussion

DHA and other ω-3s potentially quell lupus flaring and progression by altering intracellular signaling, transcription factor activity, gene expression, bioactive lipid mediator production, and membrane structure and function [reviewed in (36)]. We show here for the first time how DHA supplementation at translationally relevant doses influenced cSiO2-induced changes in gene regulation in the NZBWF1 female mouse model. Over the course of the chronic study, DHA suppressed a broad array of cSiO2-induced inflammatory, innate, and adaptive gene responses in the lung that correlated with inhibition of ectopic lymphoid neogenesis previously described in these same tissues (31). Based on ELISA data in previous studies (15, 16), we expected proinflammatory genes to be critically affected here, however, cSiO2-induced genes specifically associated with the IFN signature and chemokines were among the earliest and most robustly downregulated by DHA treatments. Furthermore, we determined that expression of the IFN-responsive proteins Mx1, Oas2 and Cxcl10 in the lung was similarly markedly induced by cSiO2 treatment and were suppressed by dietary intervention with DHA. In the kidney, DHA suppressed the expression of a broad array of gene pathways related to inflammation, innate/adaptive immunity, IFN, chemokines, antigen processing that likely contribute to cSiO2-triggered glomerulonephritis. Finally, the observation that lupus-associated mRNA signatures negatively correlated with erythrocyte ω-3 HUFA scores is of high relevance from a translational perspective.

Investigation of cSiO2-triggered lupus in the NZBWF1 mouse offers an exquisite window for exploring how environmental factors contribute to this devastating autoimmune disease as well as for understanding how potential interventions might prevent or diminish SLE flaring and progression. At the mechanistic level, polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) and alveolar macrophages (AMΦs) are the primary responders to cSiO2 and other particles in the lung. Both cell types were increased in the alveolar fluids from the lungs of cSiO2-exposed NZBWF1 mice used for the present study (31). AMΦ death occurs following lysosomal membrane permeabilization with inflammasome activation and involves pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necrosis (37, 38). cSiO2 induces death in PMN by necroptosis, a process associated with release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) (39, 40). Because cSiO2 clearance in animal models is limited (41–43), exposure to this particle drives a vicious cycle in AMΦs and PMNs involving phagocytosis of SiO2, cell death, autoantigen release, cSiO2 particle escape, and renewed cSiO2 phagocytosis [reviewed in (30)]. This feedback loop perpetuates recurrent pulmonary exposure to cSiO2 potentially saturating the efferocytotic capacity of the lung with cell corpses and autoantigens that can override tolerogenic mechanisms, particularly in animals genetically prone to autoimmunity, such as NZBWF1 mice (16, 31). In agreement with this scenario, in this study, cSiO2 induced expression of genes in the lung indicative of sustained IFN activity, chemokine release, cytokine production, complement activation, and adhesion molecule expression. These transcriptome signatures correlated with the particle's capability to evoke in the lung an early and persistent sterile inflammation, ectopic lymphoid tissue development, autoantibody production, and, in the longer term, elicit systemic autoimmunity and glomerulonephritis (17).

In the present study, short-term repeated exposure to cSiO2 evoked mRNA signatures in the lung that reflected wide-scale activation of inflammatory, innate, and adaptive gene pathways. Although comparable genes were elevated at 1 d and 1, 5, 9, and 13 weeks PI, the responses increased in both extent and intensity with time. This observation suggested that the effects of cSiO2 were not self-limiting and were consistent with a perpetual feedback loop. These gene pathways correlated with ectopic lymphoid neogenesis previously reported in the lungs from which the RNA samples were obtained for this study (17, 31). Strikingly, in the chronic experiment, consumption of the DHA high diet provided early and long-lasting protective effects against cSiO2-induced gene expression. Exhaustion of DHA's protective effects by week 13 is likely attributable to the low clearance rate of cSiO2 from the lung and continual reentry into the aforementioned inflammation cycle. Nevertheless, it might be speculated that such exhaustion might not occur in the cases of transient lupus triggers, such as infections, drugs, UV light, and stress.

While only three out of eight mice in the single dose group fed the CON diet showed altered gene response 24 h after a single cSiO2 dose, the responders' transcriptomes closely matched those for all eight mice 24 h after four weekly cSiO2 treatments. Notably, IFN- and chemokine-related genes were among those most affected. The inconsistency of the former might have resulted because of slow and incomplete cSiO2 distribution to the lower lung airways of some mice at 1 d following a single intranasal dose (25). Nonetheless, dietary DHA similarly suppressed cSiO2-triggered gene responses, suggesting that supplementation with this fatty acid could influence some of the very earliest effects of the particle.

Type I IFNs (IFNs), particularly IFN-α, induce an assemblage of up to 2000 genes referred to as the “IFN signature” that is a hallmark of SLE and other autoimmune diseases (44). In SLE patients, levels of type I IFN and IFN-inducible genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) are elevated and correlate with disease severity (45–48). GWAS investigations have further established a linkage between genes associated with type I IFN production and human lupus (49–53). The nCounter module used here contained 36 of the 63 genes in the human IFN signature designed by Li et al. (54). cSiO2 induced two-thirds of these genes in the lung, and remarkably, all were suppressed by DHA supplementation. The IFN-related genes most highly affected by DHA in this study have been associated with human SLE, including Irf7 (55, 56), Oas2 (57–60), Ifi44 (60–63), Ifit1 (64), Ifit3 (64), Isg15 (65), Nrlc5 (66), and Mx2 (67).

Consistent with our findings, cSiO2 induced a type 1 IFN response in C57Bl/6 mice within 1 week of instillation (68). Moreover, cSiO2 instillation induced accumulation of macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes and marked expression of Ifnb, Irf7, and Ccl2 in the lungs of 129SV mice, whereas these responses were significantly reduced in corresponding interferon α/β receptor knockout mice (69).

Also in agreement with our results here, preclinical studies suggest that type 1 interferons promote autoimmunity. For example, IFN-α administration to NZBWF1 mice quickened lupus onset (70, 71) and diminished the effectiveness of pharmacological interventions (4, 71). Furthermore, type I IFN overexpression hastened autoantibody production and autoimmune disease progression in NZBWF1 mice (71). Finally, type I IFN receptor deletion diminished autoantibody production and disease activity in NZBWF1 mice (72) and four other lupus-prone models (73–75). Together, these reports support our findings that the IFN signature was closely linked to cSiO2-induced autoimmune disease progression in NZBWF1 mice and, furthermore, that both the signature and disease were ablated by DHA supplementation.

Our observation that cSiO2 exposure altered IFN-related gene expression provides unique insight into putative early targets and mechanisms of action for the particle and how its effects are ameliorated by ω-3 fatty acids. A candidate cell type for the effects of cSiO2 and DHA is the plasmacytoid dendritic cell (pDC), a primary producer of IFN-α (76). pDC depletion in lupus-prone mice prior to disease initiation resulted in reduction in autoimmune pathology (77–79). Lupus-prone mice haplodeficient for a pDC-specific transcription factor contained fewer pDCs and exhibited reduced disease symptoms, particularly those related to germinal center development and autoantibody production (80). pDCs contain endosomal toll-like receptor (TLR)-7 and TLR-9 that recognize single-strand RNA and DNA, respectively (81–84). The IFNα-producing capacity of pDCs obtained from lupus patients was enhanced following TLR stimulation and these responses correlated with disease activity and serum IFN-α (85). Importantly, cSiO2 induced dsDNA release into the alveolar space in mice, and patients with silicosis had increased circulating dsDNA (68). RNA/DNA-containing immune complexes have been shown to elicit robust IFN-α production in pDCs (86–89). Indeed, prior studies have established that airway instillation of lupus-prone mice with cSiO2 triggers early and robust autoantibody responses to dsDNA, nuclear antigens, and histones coupled with increases in circulating immune complexes (11, 12, 15, 16). Thus, further investigation is needed to determine how cSiO2 affects pDC activation and type 1 IFN release and, furthermore, how DHA supplementation impairs this process.

Both type 1 IFNs and pDCs are therapeutic targets for SLE. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase IIb clinical trials have suggested the efficacies of sifalimumab, an anti-IFNα monoclonal antibody (90) and anifrolumab, a type I interferon (IFN) receptor antagonist (91, 92), for treating moderate-to-severe SLE. Very recently, a large double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical trial (TULIP-2) was completed that reported that intravenous anifrolumab was superior to placebo for multiple efficacy endpoints, including overall disease activity, skin disease, and oral corticosteroid tapering (93). Blood dendritic cell antigen 2 (BDCA2), a pDC specific receptor, has been targeted for preclinical and clinical investigation of lupus treatment (94). In non-human primates, anti-BDCA2 antibodies suppress both IFNα-production by pDCs (95). Recently, it was reported that the humanized anti-BDCA2 antibody suppressed the IFN signature and ameliorated cutaneous lesions in human lupus patients (96).

DHA's capacity to ameliorate cSiO2-upregulation of chemokine genes is also remarkable. Affected genes included chemokine ligands/receptors with C-X-C motif including Cxcl3, Cxcl9, Cxcl10, Cxcl12, Cxcl13, Cxcr1, and Cxcr3. Of particular relevance, Cxcl13 (a.k.a. B-lymphocyte chemoattractant [BLC]), is preferentially produced by follicular dendritic cells in B-cell follicles of lymphoid organs (97), a population that is upregulated in the lungs by cSiO2 (31). Treatment with anti-CXCL13 antibodies mitigated disease in murine models of autoimmune disease (98). Recently, Denton et al. (99) demonstrated in C57BL/6 mice that type I IFN produced after influenza infection induced CXCL13 expression in a lung fibroblasts, driving recruitment of B cells and initiating ectopic germinal center formation. Thus, type I IFN induces CXCL13, which, in combination with other stimuli, could provide the requisite stimuli to promote ELS. CXCL9 and CXCL10 share the receptor CXCR3 and are also induced by IFN (100). These chemokines direct activated T cell and natural killer cell migration.

Of further note, DHA mitigated cSiO2-driven upregulation of mRNAs for C-C-L motif ligands and their receptors (Ccl2, Ccl7, Ccl8, Ccl12, Ccl20 Ccr2, Ccr5, Ccr6). CCL2 (also known as monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 [MCP-1]) stimulates monocyte trafficking by binding to CCR2, and it is produced by mononuclear phagocytes, endothelial, and smooth muscle cells (101). cSiO2 exposure promoted MCP-1 elevation in BALF and plasma (15). Importantly, elevated plasma MCP-1 has been associated with increased disease severity in lupus patients (102, 103). CCL7 (MCP-3), CCL8 (MCP-2), and CCL12 (MCP-5) are structurally related and share properties with CCL2. Finally, CCR6 and its ligand CCL20 (MCP-3α) coordinate regulation of effective humoral responses also have been linked to autoantibody-driven autoimmune diseases including lupus (104).

Our prior histological assessment (33) of the kidneys employed in this study indicated that 13 weeks after cSiO2 instillation, CON-fed mice exhibited proteinuria with moderate to severe diffuse glomerulonephritis. Consistent with this observation, we found here that there was extensive upregulation of immune genes in kidney tissue, most notably those associated with IFN, chemokines, antigen presentation, and MHC expression. Mice fed DHA exhibited marked reduction of these histopathological lesions reflecting the dramatic suppression of massive cell recruitment and gene expression during cSiO2-driven inflammation. Since cSiO2 is retained the lung and its associated lymph nodes (41, 42), the cellular and gene responses in the kidney most likely result from autoantibodies and immune complexes originating in the lung. We speculate that these travel via the systemic compartment and consequently deposit in the kidney evoking vigorous inflammation and ultimately glomerulonephritis. Accordingly, the kidney histological and mRNA profiles very likely were an outcome of cSiO2-triggered ELS formation in the lung. Since DHA supplementation impeded pulmonary ectopic lymphoid neogenesis in the lung, it follows that DHA also prevented downstream cell recruitment and gene expression in the kidney. Finally, it should be noted that gene responses in the spleen to cSiO2 and DHA treatments were very modest compared to the lung and kidney. This result may be expected because the spleen contains many more non-activated cells than lung which would dilute expression of immune genes.

Our finding that DHA supplementation impeded genes associated with lupus flaring and glomerulonephritis are consistent with several clinical trials suggesting that there are potential benefits of ω-3 intake by SLE patients. To date, nine controlled clinical studies have tested ω-3-containing fish oil supplements on lupus. Supplementation duration varied from 10 to 52 weeks, and patients per trial ranged from 12 to 85 subjects. ω-3 intake ranged from 0.54 to 3.60 g/d EPA and 0.30 to 2.25 g/d DHA. Five investigations showed ω-3 supplementation modulated and improved SLE scores (105–109). Another trial included both non-nephritic SLE patients and lupus nephritis patients and found significant improvements in several SLE markers in blood (110). One study reported improvement in clinical parameters after 3 months but not at 6 months (111). In contrast, two other clinical studies reported no therapeutic benefits of ω-3 for patients with SLE (112) or lupus nephritis (113). General limitations of the clinical studies run to date include low numbers of patients, short study length, insufficient ω-3 dosage, lack of corroborating fatty acid analyses, and/or not controlling impact of concurrent SLE therapies. It should be noted that the clinical studies to date have typically used between 1 to 5 g of ω-3 mixtures of DHA plus EPA. The observation that diets providing human energy equivalents of 5 g/d DHA elicited more marked and longer lasting effects than the DHA low diet is potentially a critical consideration for future clinical studies. Thus, additional studies are required to examine the potential differential effects of DHA and EPA.

Conclusion

Taken together, the findings reported herein that DHA supplementation impeded IFN and chemokine gene expression associated with lupus flaring and nephritis supports the contention that dietary supplementation with ω-3 fatty acids may be a viable adjunct for the prevention and treatment of SLE. A potential mechanism linking dietary ω-3 supplementation to the observed transcriptional changes is the alteration of the cell membrane lipid profile, as DHA elevates membrane ω-3 HUFAs at the expense of ω-6 HUFAs. Consequently, this shift in membrane lipids could modify HUFA-derived metabolite profiles. Lipid metabolites derived from the ω-6 HUFA arachidonic acid (ARA) include the proinflammatory prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and thromboxanes. Alternatively, metabolites derived from ω-3 HUFAs, including DHA, docosapentaenoic acid (DPA) and EPA have been termed specialized pro-resolving mediators due to their capacity to resolve inflammatory responses. These mediators, as well as the free fatty acids from which they are metabolized, have been shown to participate in anti-inflammatory signaling pathways inhibiting the transcription of pro-inflammatory genes. We chose to assess levels of membrane ω-3 HUFAs as a percent of total HUFA (ω-3 HUFA score) (Figure 6), as defined by Lands and coworkers (19), to accentuate the competition between metabolism of ω-3 and ω-6 HUFAs. We found robust negative correlations between the ω-3 HUFA score and many of the gene pathways induced by cSiO2, providing strong evidence that incorporation into the phospholipid membrane is central to DHA's protective effects. Additional research is needed to determine how the ω-3 HUFA score and IFN signature could be used in a precision medicine approach to identify lupus patients that may benefit from ω-3 supplementation.

Data Availability Statement

The data output from nSolver analyses for this study can be found at https://doi.org/10.26078/4697-1p77. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Michigan State University (AUF #01/15-021-00).

Author Contributions

AB: data analyses and interpretation, statistical analysis, figure preparation, and manuscript preparation and submission. MB: study design, animal study coordination, necropsy, RNA analysis, data analyses and interpretation, manuscript preparation, and project funding. PC: experimental design, immunohistochemistry, and cytokine analyses. KW: fatty acid analyses, data analyses, and manuscript preparation. KG: animal study coordination, RNA analysis, data analyses, and manuscript preparation. AH: experimental design, data interpretation, manuscript writing, and project funding. JH: study design, lung and kidney histopathology, morphometry, data analyses, manuscript preparation, and project funding. JP: planning, coordination, oversight, manuscript preparation and submission, and project funding.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. James Wagner, Dr. Ning Li, Dr. Daven Humbles-Jackson, Amy Freeland, Lysie Eldridge, and Ryan Lewandowski for their excellent technical support, and Amy Porter and Kathy Joseph from the Michigan State University Histopathology Laboratory.

Footnotes

Funding. This research was supported by NIH ES027353 (JP, JH, and AH), Lupus Foundation of America (AB and JP), the Dr. Robert and Carol Deibel Family Endowment (JP) and by Hatch Capacity Grant no. UTA-01407 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (AB), NIEHS Training Grant T32ES007255 (KW), Ruth L. Kirschstein Individual Predoctoral NRSA F31ES030593 (KW), and USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture HATCH Project 1020129 (JP).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2019.02851/full#supplementary-material

File with Supplementary Figures 1–11.

The supplementary data files are available at: https://doi.org/10.26078/4697-1p77.

Customized probe annotation file for the NanoString nCounter Mouse PanCancer Immune Profiling Panel.

Microsoft Excel document with output from nSolver for differential expression analyses.

Microsoft Excel document with output from nSolver for global and directed significance scores for immune pathways.

Microsoft Excel document with output from nSolver for immune pathway Z scores for pairwise comparisons.

Microsoft Excel document with protein networks obtained from STRING database and clusters predicted by the MCL algorithm.

References

- 1.Pons-Estel GJ, Ugarte-Gil MF, Alarcon GS. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. (2017) 13:799–814. 10.1080/1744666X.2017.1327352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flores-Mendoza G, Sanson SP, Rodriguez-Castro S, Crispin JC, Rosetti F. Mechanisms of tissue injury in lupus nephritis. Trends Mol Med. (2018) 24:364–78. 10.1016/j.molmed.2018.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sang A, Yin Y, Zheng YY, Morel L. Animal models of molecular pathology systemic lupus erythematosus. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. (2012) 105:321–70. 10.1016/B978-0-12-394596-9.00010-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Z, Bethunaickan R, Huang W, Lodhi U, Solano I, Madaio MP, et al. Interferon alpha accelerates murine SLE in a T cell dependent manner. Arthr Rheum. (2011) 63:219–29. 10.1002/art.30087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dai C, Wang H, Sung SS, Sharma R, Kannapell C, Han W, et al. Interferon alpha on NZM2328.Lc1R27: enhancing autoimmunity and immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis without end stage renal failure. Clin Immunol. (2014) 154:66–71. 10.1016/j.clim.2014.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacob N, Guo S, Mathian A, Koss MN, Gindea S, Putterman C, et al. B Cell and BAFF dependence of IFN-alpha-exaggerated disease in systemic lupus erythematosus-prone NZM 2328 mice. J Immunol. (2011) 186:4984–93. 10.4049/jimmunol.1000466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ansel JC, Mountz J, Steinberg AD, DeFabo E, Green I. Effects of UV radiation on autoimmune strains of mice: increased mortality and accelerated autoimmunity in BXSB male mice. J Invest Dermatol. (1985) 85:181–6. 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12276652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolf SJ, Estadt SN, Theros J, Moore T, Ellis J, Liu J, et al. Ultraviolet light induces increased T cell activation in lupus-prone mice via type I IFN-dependent inhibition of T regulatory cells. J Autoimmun. (2019) 103:102291. 10.1016/j.jaut.2019.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark KL, Reed TJ, Wolf SJ, Lowe L, Hodgin JB, Kahlenberg JM. Epidermal injury promotes nephritis flare in lupus-prone mice. J Autoimmun. (2015) 65:38–48. 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parks CG, Miller FW, Pollard KM, Selmi C, Germolec D, Joyce K, et al. Expert panel workshop consensus statement on the role of the environment in the development of autoimmune disease. Int J Mol Sci. (2014) 15:14269–97. 10.3390/ijms150814269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown JM, Archer AI, Pfau IC, Holian A. Silica accelerated systemic autoimmune disease in lupus-prone New Zealand mixed mice. Clin Exp Immunol. (2003) 131:415–21. 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02094.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown JM, Pfau JC, Holian A. Immunoglobulin and lymphocyte responses following silica exposure in New Zealand mixed mice. Inhal Toxicol. (2004) 16:133–9. 10.1080/08958370490270936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown JM, Schwanke CM, Pershouse MA, Pfau JC, Holian A. Effects of rottlerin on silica-exacerbated systemic autoimmune disease in New Zealand mixed mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. (2005) 289:L990–8. 10.1152/ajplung.00078.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown JM, Swindle EJ, Kushnir-Sukhov NM, Holian A, Metcalfe DD. Silica-directed mast cell activation is enhanced by scavenger receptors. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. (2007) 36:43–52. 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0197OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bates MA, Brandenberger C, Langohr I, Kumagai K, Harkema JR, Holian A, et al. Silica triggers inflammation and ectopic lymphoid neogenesis in the lungs in parallel with accelerated onset of systemic autoimmunity and glomerulonephritis in the lupus-prone NZBWF1 mouse. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0125481. 10.1371/journal.pone.0125481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bates MA, Brandenberger C, Langohr II, Kumagai K, Lock AL, Harkema JR, et al. Silica-triggered autoimmunity in lupus-prone mice blocked by docosahexaenoic acid consumption. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0160622. 10.1371/journal.pone.0160622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bates MA, Benninghoff AD, Gilley KN, Holian A, Harkema JR, Pestka JJ. Mapping of dynamic transcriptome changes associated with silica-triggered autoimmune pathogenesis in the lupus-prone NZBWF1 mouse. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:632. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calder PC. Omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: from molecules to man. Biochem Soc Trans. (2017) 45:1105–15. 10.1042/BST20160474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lands B, Bibus D, Stark KD. Dynamic interactions of n-3 and n-6 fatty acid nutrients. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. (2018) 136:15–21. 10.1016/j.plefa.2017.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris WS. The Omega-6:Omega-3 ratio: a critical appraisal and possible successor. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. (2018) 132:34–40. 10.1016/j.plefa.2018.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adarme-Vega TC, Thomas-Hall SR, Schenk PM. Towards sustainable sources for omega-3 fatty acids production. Curr Opin Biotechnol. (2014) 26:14–8. 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson DR, Prickett JD, Makoul GT, Steinberg AD, Colvin RB. Dietary fish oil reduces progression of established renal disease in (NZB x NZW)F1 mice and delays renal disease in BXSB and MRL/1 strains. Arthr Rheum. (1986) 29:539–46. 10.1002/art.1780290412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson DR, Xu LL, Tateno S, Guo M, Colvin RB. Suppression of autoimmune disease by dietary n-3 fatty acids. J Lipid Res. (1993) 34:1435–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim BO, Jolly CA, Zaman K, Fernandes G. Dietary (n-6) and (n-3) fatty acids and energy restriction modulate mesenteric lymph node lymphocyte function in autoimmune-prone (NZB × NZW)F1 mice. J Nutr. (2000) 130:1657–64. 10.1093/jn/130.7.1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jolly CA, Muthukumar A, Avula CP, Troyer D, Fernandes G. Life span is prolonged in food-restricted autoimmune-prone (NZB x NZW)F(1) mice fed a diet enriched with (n-3) fatty acids. J Nutr. (2001) 131:2753–60. 10.1093/jn/131.10.2753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhattacharya A, Lawrence RA, Krishnan A, Zaman K, Sun D, Fernandes G. Effect of dietary n-3 and n-6 oils with and without food restriction on activity of antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxidation in livers of cyclophosphamide treated autoimmune-prone NZB/W female mice. J Amer Coll Nutr. (2003) 22:388–99. 10.1080/07315724.2003.10719322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halade GV, Rahman MM, Bhattacharya A, Barnes J, Chandrasekar B, Fernandes G. Docosahexaenoic acid-enriched fish oil attenuates kidney disease and prolongs median and maximal life span of autoimmune lupus-prone mice. J Immunol. (2010) 184:5280–6. 10.4049/jimmunol.0903282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halade GV, Williams PJ, Veigas JM, Barnes JL, Fernandes G. Concentrated fish oil (Lovaza(R)) extends lifespan and attenuates kidney disease in lupus-prone short-lived (NZBxNZW)F1 mice. Exp Biol Med. (2013) 238:610–22. 10.1177/1535370213489485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pestka JJ, Vines LL, Bates MA, He K, Langohr I. Comparative effects of n-3, n-6 and n-9 unsaturated fatty acid-rich diet consumption on lupus nephritis, autoantibody production and CD4+ T cell-related gene responses in the autoimmune NZBWF1 mouse. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e100255. 10.1371/journal.pone.0100255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wierenga KA, Harkema JR, Pestka JJ. Lupus, silica, and dietary omega-3 fatty acid interventions. Toxicol Pathol. (2019). 10.1177/0192623319878398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bates MA, Akbari P, Gilley KN, Wagner JG, Li N, Kopec AK, et al. Dietary docosahexaenoic acid prevents silica-induced development of pulmonary ectopic germinal centers and glomerulonephritis in the lupus-prone NZBWF1 mouse. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:2002. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reeves PG, Nielsen FH, Fahey GC, Jr. AIN-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: final report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the AIN-76A rodent diet. J Nutr. (1993) 123:1939–51. 10.1093/jn/123.11.1939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hulsen T, de Vlieg J, Alkema W. BioVenn - a web application for the comparison and visualization of biological lists using area-proportional Venn diagrams. BMC Genomics. (2008) 9:488. 10.1186/1471-2164-9-488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oliveros JC. Venny. An Interactive Tool for Comparing Lists With Venn's Diagrams. (2007). Available online at: http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html (cited January 6, 2019).

- 35.Metsalu T, Vilo J. ClustVis: a web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using Principal Component Analysis and heatmap. Nucl Acids Res. (2015) 43:W566–70. 10.1093/nar/gkv468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calder PC. Marine omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: effects, mechanisms and clinical relevance. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2015) 1851:469–84. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rabolli V, Lison D, Huaux F. The complex cascade of cellular events governing inflammasome activation and IL-1beta processing in response to inhaled particles. Part Fibre Toxicol. (2016) 13:40. 10.1186/s12989-016-0150-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joshi GN, Knecht DA. Silica phagocytosis causes apoptosis and necrosis by different temporal and molecular pathways in alveolar macrophages. Apoptosis. (2013) 18:271–85. 10.1007/s10495-012-0798-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Y, Cao X, Liu Y, Zhao Y, Herrmann M. Neutrophil extracellular traps formation and aggregation orchestrate induction and resolution of sterile crystal-mediated inflammation. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:1559. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Desai J, Foresto-Neto O, Honarpisheh M, Steiger S, Nakazawa D, Popper B, et al. Particles of different sizes and shapes induce neutrophil necroptosis followed by the release of neutrophil extracellular trap-like chromatin. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:15003. 10.1038/s41598-017-15106-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Absher MP, Hemenway DR, Leslie KO, Trombley L, Vacek P. Intrathoracic distribution and transport of aerosolized silica in the rat. Exp Lung Res. (1992) 18:743–57. 10.3109/01902149209031705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vacek PM, Hemenway DR, Absher MP, Goodwin GD. The translocation of inhaled silicon dioxide: an empirically derived compartmental model. Fund Appl Toxicol. (1991) 17:614–26. 10.1016/0272-0590(91)90211-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawasaki H. A review of the fate of inhaled α-quartz in the lungs of rats. Inhal Toxicol. (2019) 31:25–34. 10.1080/08958378.2019.1597218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bengtsson AA, Ronnblom L. Role of interferons in SLE. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. (2017) 31:415–28. 10.1016/j.berh.2017.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hooks JJ, Moutsopoulos HM, Geis SA, Stahl NI, Decker JL, Notkins AL. Immune interferon in the circulation of patients with autoimmune disease. N Engl J Med. (1979) 301:5–8. 10.1056/NEJM197907053010102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bengtsson AA, Sturfelt G, Truedsson L, Blomberg J, Alm G, Vallin H. Activation of type I interferon system in systemic lupus erythematosus correlates with disease activity but not with antiretroviral antibodies. Lupus. (2000) 9:664–71. 10.1191/096120300674499064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crow MK, Kirou KA, Wohlgemuth J. Microarray analysis of interferon-regulated genes in SLE. Autoimmunity. (2003) 36:481–90. 10.1080/08916930310001625952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kirou KA, Lee C, George S, Louca K, Papagiannis IG, Peterson MG, et al. Coordinate overexpression of interferon-α-induced genes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. (2004) 50:3958–67. 10.1002/art.20798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harley JB, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Criswell LA, Jacob CO, Kimberly RP, Moser KL. Genome-wide association scan in women with systemic lupus erythematosus identifies susceptibility variants in ITGAM, PXK, KIAA1542 and other loci. Nat Genet. (2008) 40:204–10. 10.1038/ng.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hom G, Graham RR, Modrek B, Taylor KE, Ortmann W, Garnier S. Association of systemic lupus erythematosus with C8orf13-BLK and ITGAM-ITGAX. N Engl J Med. (2008) 358:900–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa0707865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen N, Fu Q, Deng Y, Qian X, Zhao J, Kaufman KM. Sex-specific association of X-linked Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) with male systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2010) 107:15838–43. 10.1073/pnas.1001337107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Joseph S, George NI, Green-Knox B, Treadwell EL, Word B, Yim S, et al. Epigenome-wide association study of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in systemic lupus erythematosus: Identifying DNA methylation signatures associated with interferon-related genes based on ethnicity and SLEDAI. J Autoimmun. (2019) 96:147–57. 10.1016/j.jaut.2018.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hiramatsu S, Watanabe KS, Zeggar S, Asano Y, Miyawaki Y, Yamamura Y, et al. Regulation of Cathepsin E gene expression by the transcription factor Kaiso in MRL/lpr mice derived CD4+ T cells. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:3054. 10.1038/s41598-019-38809-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li Q-Z, Zhou J, Lian Y, Zhang B, Branch VK, Carr-Johnson F, et al. Interferon signature gene expression is correlated with autoantibody profiles in patients with incomplete lupus syndromes. Clin Exp Immunol. (2010) 159:281–91. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.04057.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu WD, Zhang YJ, Xu K, Zhai Y, Li BZ, Pan HF, et al. IRF7, a functional factor associates with systemic lupus erythematosus. Cytokine. (2012) 58:317–20. 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kawasaki A, Furukawa H, Kondo Y, Ito S, Hayashi T, Kusaoi M, et al. Association of PHRF1-IRF7 region polymorphism with clinical manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus in a Japanese population. Lupus. (2012) 21:890–5. 10.1177/0961203312439333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ye S, Guo Q, Tang JP, Yang CD, Shen N, Chen SL. Could 2'5'-oligoadenylate synthetase isoforms be biomarkers to differentiate between disease flare and infection in lupus patients? A pilot study. Clin Rheumatol. (2007) 26:186–90. 10.1007/s10067-006-0260-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tang J, Gu Y, Zhang M, Ye S, Chen X, Guo Q, et al. Increased expression of the type I interferon-inducible gene, lymphocyte antigen 6 complex locus E, in peripheral blood cells is predictive of lupus activity in a large cohort of Chinese lupus patients. Lupus. (2008) 17:805–13. 10.1177/0961203308089694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grammatikos AP, Kyttaris VC, Kis-Toth K, Fitzgerald LM, Devlin A, Finnell MD, et al. A T cell gene expression panel for the diagnosis and monitoring of disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Immunol. (2014) 150:192–200. 10.1016/j.clim.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bing PF, Xia W, Wang L, Zhang YH, Lei SF, Deng FY. Common marker genes identified from various sample types for systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0156234. 10.1371/journal.pone.0156234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rodriguez-Carrio J, Lopez P, Alperi-Lopez M, Caminal-Montero L, Ballina-Garcia FJ, Suarez A. IRF4 and IRGs delineate clinically relevant gene expression signatures in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:3085. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ulff-Moller CJ, Asmar F, Liu Y, Svendsen AJ, Busato F, Gronbaek K, et al. Twin DNA methylation profiling reveals flare-dependent interferon signature and b cell promoter hypermethylation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthr Rheum. (2018) 70:878–90. 10.1002/art.40422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]