Abstract

Extracellular purines (ATP and adenosine) are ubiquitous intercellular messengers. During tissular damage, they function as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). In this context, purines announce tissue alterations to initiate a reparative response that involve the formation of the inflammasome complex and the recruitment of specialized cells of the immune system. The present review focuses on the role of the purinergic system in liver damage, mainly during the onset and development of fibrosis. After hepatocellular injury, extracellular ATP promotes a signaling cascade that ameliorates tissue alterations to restore the hepatic function. However, if cellular damage becomes chronic, ATP orchestrates an aberrant reparative process that results in severe liver diseases such as fibrosis and cirrhosis. ATP and adenosine, their receptors, and extracellular ectonucleotidases are mediators of unique processes that will be reviewed in detail.

Keywords: Purinergic receptors, Ectonucleotidases, Liver, Fibrosis, Inflammation

Chronic hepatic diseases

Functional and cellular organization of the liver

The liver is one of the most active organs from a metabolic perspective. It is the only organ that can put together all the elements required to form purine and pyrimidine rings and then send them into the bloodstream to be used by other organs as energetic and signaling molecules [1]. In humans, the liver receives almost 30% of the blood supply and consumes one fifth of the available O2. The liver also plays immunological roles because it is essential to set an innate body defense during acute illnesses [2]. It has been said that the primary function of the hepatic tissue was immunological and that the biochemical role in the integration of intermediary metabolism evolved during further specialization [3].

Many functions of the liver are related to the metabolic conversions of nutrients and vitamins and the processing of xenobiotics [4]. Hepatic biochemical activities include glycogen metabolism and gluconeogenesis; synthesis of fatty acids, triacylglycerols, phospholipids, and bile acids; synthesis, secretion, and transformation of lipoproteins; ketogenesis; synthesis of albumin, blood clotting factors such as angiotensinogen, metal-handling proteins, apolipoproteins, and IGF-1; NH4+-handling by urea and glutamine; and endocytic protection (removal of bacteria and endotoxins by Kupffer cells).

The histological unit of the liver is the lobule. It is delimited by a central vein surrounded by six portal triads; each portal triad is formed by a branch of the portal vein, a branch of the hepatic artery, and a bile ductule. Portal triads and the central vein are connected by cords of hepatocytes; interestingly, the metabolic capabilities of the periportal hepatocytes are different from the ones shown by the pericentral hepatocytes. This metabolic zonation is caused by the O2 gradient that is established along the lobule, being the metabolic networks more oxidative in the periportal hepatocytes and more reductive in the pericentral hepatocytes [5]. Liver cell plates are divided by sinusoids, which are demarcated by endothelial cells. Within the sinusoids are resident macrophages known as Kupffer cells (KCs). There is a subendothelial region between the hepatocyte cords and the sinusoids, called Disse space. In this region, a non-parenchymal cell population, known as hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), can be found. HSCs are responsible for fibrogenic responses in the liver [6].

The liver is a complex organ that functions by the coordinated action of a variety of cell types [7]: (1) hepatocytes, which are the main parenchymal cells in the liver, constitute ~ 80% of the hepatic mass. Hepatocytes perform the principal metabolic activities of the liver. (2) Biliary epithelial cells, also known as cholangiocytes, are parenchymal cells that form the bile ducts. The intrahepatic biliary tract contains the bile canaliculi and the canals of Hering, whereas the extracellular biliary tract is composed of the gallbladder and the cystic duct. (3) HSCs, also known as lipocytes or Ito cells, are liver pericytes that present two phenotypes: a quiescent vitamin A-storing cell and an activated myofibroblast-like cell that is responsible for collagen deposition in situations of liver damage. (4) KCs, which are hepatic macrophages lining the walls of the sinusoids, and promote a pro-oxidant and inflammatory response that turns the HSCs into the collagen-forming phenotype that eventually leads to fibrosis. (5) Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs), which form a permeable barrier acting as an interface between blood cells, HSCs, and hepatocytes, have a very high endocytic capacity. (6) Pit cells, which are lymphoid entities located in the portal region, are crucial during liver inflammation and fibrogenesis. (8) Oval cells, which are adult stem cells derived from activated hepatic progenitor cells located in the terminal bile ducts, can differentiate into hepatocytes and cholangiocytes. Oval cell activation can be triggered in situations of severe liver injury such as in cirrhosis.

Liver pathology

The liver is a very plastic organ that is capable of showing discrete cellular turnover under circadian regulation and an exceptional regenerative potential in response to surgical hepatectomy (complete tissue renewal after 8 days of 2/3 hepatectomy in rodents). During this process, extracellular matrix molecules orchestrated by Ito cells play a key role in reestablishing the normal vascular structure of the liver [8]. However, the liver is also susceptible to suffering pathological alterations, as well as metabolic and endocrine disturbances by the action of drugs, environmental factors, and microorganisms. Given its regenerative potential, the liver can overcome acute damage in many circumstances; however, chronic injuries can promote homeostatic disequilibrium that leads to chronic hepatic diseases such as inflammation (hepatitis), fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (Fig. 1).

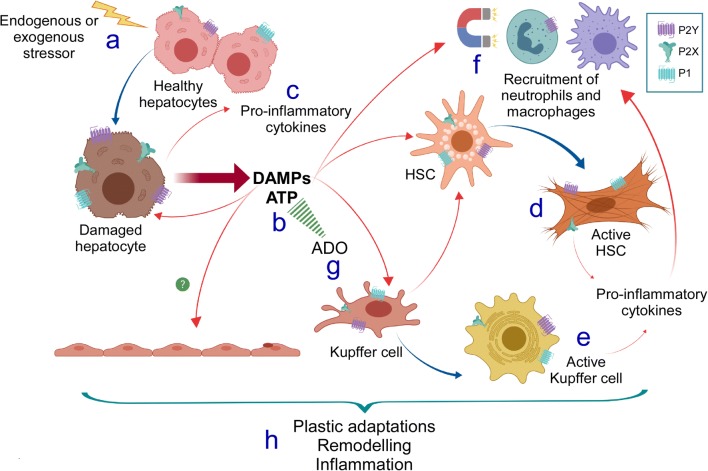

Fig. 1.

Pro-inflammatory responses mediated by purinergic signaling associated with hepatocellular damage. Upon hepatocellular injury or stress (a), damaged hepatocytes release DAMPs, particularly ATP, into the extracellular space (b). This nucleotide exerts its actions by interacting with specific P2X (mainly P2X7 and P2X4 in the liver) and P2Y membrane receptors (mainly P2Y2 in the liver). The autocrine/paracrine purinergic actions promote the production and release of pro-inflammatory molecules by the own hepatocyte or by other liver cell types (c), such as hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) and Kupffer cells, to induce their activated phenotype (d, e). Then, additional ATP and other pro-inflammatory signals released from activated HSCs and Kupffer cells act as chemoattractants for immune cells such as neutrophils and macrophages (f). At the same time, ATP is irreversibly turned into adenosine (ADO), which also contributes to the cellular events leading to liver fibrosis by acting through P1 receptors (g). Together, these signals support the wound-healing response that, after some time, promotes hepatocellular plastic adaptations, tissular remodeling, and chronic inflammation (h), culminating in a fibrotic state. In the picture, red arrows indicate released compounds to the extracellular space acting in autocrine or paracrine fashion, whereas blue arrows indicate phenotypic changes of the participating cells

Inflammation

This entity comprises several associated complex biological processes by which the tissues respond to harmful or pathogenic stimuli. The pro-inflammatory agents can be intrinsic (DNA damage, pro-oxidant reactions, metabolic deregulation) or extrinsic (pathogens, irritants). Inflammation can be related to molecular instabilities causing cellular damage or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), molecular patterns associated with microbes (MAMPs), or other pathogens (PAMPs) [9]. Inflammasomes will be addressed later.

Fibrosis

Unlike other organs and tissues, the liver lacks a proper basement membrane and its histological organization, based on the configuration of the Disse space, is suited to facilitate the rapid bidirectional exchange between plasma and the hepatocytes. This specialization is achieved by the abundant fenestrations and gaps of the sinusoidal endothelial cells and an extracellular matrix mostly consisting of fibronectin, some collagen type 1, and minor quantities of collagen types III to VI [10]. Due to repetitive injuries, either by drugs, virus, or stressful metabolic conditions, the regenerative capacity of the liver becomes compromised. At early phases, little to mild hepatic damage occurs. However, as the cellular damage continues, so does a disorder of the extracellular matrix known as scarring or fibrosis. This condition can be reversed if the cause(s) stop before too much tissue alteration occurs [11].

Cirrhosis

If the scarring process continues over time, fibrosis becomes permanent. The histological deformation becomes more evident with the formation of thick collagen bands (fibrous septa) throughout the liver, involving dynamic changes in matrix stiffness, flexibility, and density. The regenerative ability of the liver is obliterated, and hepatic function is severely compromised; this state is called cirrhosis. The cirrhotic liver shows profound alterations in the structure of the extracellular matrix: (1) exacerbated elevation of elastin and reduced collagen I and III content; (2) collagen VI forms branched filamentous networks by the enhanced expression of protein COL6A1; (3) a basement membrane formed by basal lamina appears, disrupting the exchange of factors and metabolites between hepatocytes and the plasma; and (4) endothelial fenestration is lost [11]. On the onset and establishment of cirrhosis, HSCs play a preponderant role: because of the presence of inflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress, and growth factors, the retinoid-containing quiescent HSCs become transdifferentiated into activated myofibroblasts. Vitamin A deposits are greatly reduced, whereas the expression of α-smooth muscle actin is importantly enhanced. Myofibroblasts promote fibrogenesis (by transforming growth factor-β1 [TGF-β1] and CTGF), matrix restructuration (by MMP-2 and 9, and TIMP-1 and 2), leukocyte chemoattraction (by MCP-1), cytokine secretion, Ito cell chemotaxis (by PDGF), and hepatocyte proliferation [12].

Hepatocellular carcinoma

It is a primary malignancy of the liver that is usually the culmination of a previous hepatic chronic disorder such as cirrhosis, prolonged alcohol intake, and viral hepatitis. At present, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a major cause of death associated with neoplastic illness. Molecular characterization of this malignancy describes a complex and heterogeneous entity with a vast array of genetic (punctual mutations, chromosomal rearrangements, and gain/loss of genomic DNA) and epigenetic modifications [13]. Among the signaling pathways that have been related to the onset and development of HCC are WNT/β-catenin, receptor tyrosine kinases, VEGF and other angiogenic pathways, TGF-β, JAK/STAT, and ubiquitin proteasome.

Purines and cell signaling

It is now well established that intercellular signaling regulated by purines is a form of ubiquitous cellular communication. The concept of purinergic signaling was introduced by Geoffrey Burnstock in 1972 [14]. After the purinergic signaling theory gained wider acceptance, research focused on the identification of cell membrane receptors sensitive to extracellular nucleotides and nucleosides. Receptors were classified as P1, sensitive to adenosine, and P2, sensitive to ATP. From the P1 family, four receptors were cloned and characterized (A1, A2A, A2B, and A3). These receptors are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that are differentially coupled to Gs/Gi signaling pathways and activate the mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ and changes in cAMP concentration levels [15, 16].

On the other hand, P2 receptors were subsequently divided into two subfamilies, P2X and P2Y, as evidence suggested that both had different pharmacological and molecular properties, and their activation led to differences in signaling pathways [17, 18]. P2X receptors are ligand-gated cation channels from which seven subunits have been cloned and described (P2X1–7) [19]. P2Y receptors belong to the GPCR superfamily and their activation leads to Gi/q-mediated signaling. From this subfamily, eight receptor subtypes have been cloned and characterized (P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6, P2Y11, P2Y12, P2Y13, and P2Y14) [20].

The intracellular concentration of ATP can reach [mM] levels; in contrast, ATP in the extracellular space is in the much lower [nM] range. Due to the vast amount of ATP-dependent processes, there is a fine and tight intracellular regulation of ATP exchange [21, 22]. Because ATP can act as a molecular messenger, it has been demonstrated in neurons and many endocrine cells that this molecule can be stored in small synaptic vesicles alongside several neurotransmitters and in large granular (dense-cored) vesicles along with peptides [23–26]. ATP can be released from these same vesicles through exocytosis in mechanisms both dependent on and independent of calcium dynamics [21, 27]. Moreover, it is now well described that ATP can be released to the extracellular space through several other physiologically relevant mechanisms, including connexin/pannexin membrane hemichannels, and by activation of membrane transporters [28]. Nucleotides can also be released from apoptotic cells in a damage setting to serve as “find-me” signals that promote phagocyte recruitment [29], as well as from necrotic cells when their contents are overturned to the extracellular space, where they can act as DAMPs to activate inflammatory signaling through the inflammasome complex [30].

Nucleotide hydrolysis is a very efficient and swift process that occurs in the extracellular space through the actions of membrane-bound ectonucleotidases, and its ultimate product is generally the nucleoside adenosine. Ectonucleotidases tightly control the availability and ratios of nucleotides/nucleosides and can be powerful regulators of purinergic signaling in a variety of processes. Four main families of ectonucleotidases have been characterized: ectonucleotidase triphosphate diphosphohydrolases (E-NTPDases), ecto-5′-nucletidases (eNs), ectonucleotidase pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterases (E-NPPs), and alkaline phosphatases [31].

Due to the characterization of the wide expression of most purinergic receptors in almost all cell types in many tissues in both invertebrates and vertebrates, a great body of research has focused on the relevance of their expression in regulating a variety of physiological functions. Evidence has demonstrated the participation of purines in short-term processes, such as neurotransmission and cytokine release [15, 32], as well as in biological processes that include proliferation, epithelial to mesenchymal transition, regulation of metabolic processes, platelet aggregation, differentiation, and inflammation in various other tissues [33, 34].

Purines in liver fibrosis

ATP

The physiological actions related to the purinergic receptor P2Y2 have been widely described in the liver [35–37]. This receptor is essential for hepatic regeneration; for example, in P2Y2R−/− mice, the early events in cell cycle progression and cell proliferation (associated with ERK/Egr-1/AP-1 pathway) were impaired after 70% partial hepatectomy [38]. This notable role of the P2Y2 receptor acting as a modulator of liver regenerative response suggests that ATP and its specific receptors, not only P2Y2, could be playing a role in the cellular response related to tissular damage during liver disease.

A possible role for the purinergic system has been investigated in different models of liver disease. In rats, experimental liver damage by systemic administration of dimethylnitrosamine for 10 weeks or carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) for 6 to 8 weeks was attenuated by the blockade of purinergic receptors using the antagonist pyridoxalphosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonic acid (PPADS), which inhibited the appearance of fibrotic markers in the liver, specifically the increased deposition of type I collagen. To explain this observation, it was proposed that the effect of antagonizing the purinergic receptors with PPADS regulated the activation of HSCs. Interestingly, the action mediated by PPADS was selective because it did not have an effect on the liver fibrosis produced by bile duct ligation [39].

On the other hand, acute hepatitis induction by administration of concanavalin A in mice induced hepatic ATP release and an increment in P2Y2 expression; in agreement, P2Y2R−/− mice showed reduced damage in response to the same treatment and were less sensitive to acetaminophen (APAP)-induced liver damage [40]. These observations suggest that extracellular ATP and purinergic receptors participate in the early mechanisms associated with liver damage by toxic treatments.

P2X receptors are also expressed in the liver, where transcripts for P2X1, P2X2, P2X3, P2X4, and P2X7 have been detected. In isolated hepatocytes, transcripts and proteins corresponding to P2X4 and P2X7 receptors have been reported. In these cells, the stimulation with 2′(3′)-O-(4-benzoylbenzoyl)adenosine-5′-triphosphate (BzATP) induced a reduction in glycogen content and elicited Na+ conductances as well as the release of intracellular Ca2+. The biophysical and biochemical characterization indicated that P2X4 is the receptor involved in these responses in hepatocytes [41]. Moreover, partial hepatectomy in P2X4R−/− mice showed impaired biliary adaptation post hepatectomy, resulting in a delay in the proliferation response and apoptotic induction in hepatocytes [42]. This suggests that P2X4 participates in the adaptive response to liver tissue damage.

Additionally, the fibrotic response (estimated by the expression level of procollagen-1 transcript and collagen deposition within the tissue) elicited by bile duct ligation or a high-fat diet is less in P2X4R−/− mice compared to wild type (WT) mice; interestingly, P2X4R−/− mice did not show differences in the fibrotic induction when damage was induced by CCl4, unlike in the P2Y2/PPADS experiments. This sensitivity to a fibrotic stimulus was mediated by P2X4 signaling that drove the phenotype of hepatic myofibroblasts (MFBs)—mainly portal MFBs—to a profibrotic profile [43].

Purinergic signaling can also mediate the activation and recruitment of immune cells in the liver, increasing the severity of hepatic diseases. In a mouse model of primary sclerosing cholangitis (KO of multidrug resistance protein 2 knockout, Mdr2−/−), deletion of CD39 (CD39−/−) induced an increment of CD8+ T cells exacerbating liver injury and fibrosis, suggesting that extracellular ATP signaling favors CD8+ T cells infiltration to the damaged region [44]. In agreement, in a sepsis-induced liver injury model, CD39 expression limits P2X7 pro-inflammatory signaling and cytokine production [45], and a more severe effect of the hepatotoxic CCl4 has been also demonstrated in ENTPD2 null mice [46]. P2Y2R has also been related to activate an immune response in acute liver damage. P2Y2R−/− mice reduced the expression of chemoattractants compared to WT mice in response of concanavalin A, directly impacting on hepatic immune cell infiltration [40].

Adenosine

Accumulated evidence suggests that adenosine (ADO) is a profibrotic intracellular messenger acting through A2A receptors (A2AR). The systemic administration of A2AR antagonists, caffeine, or ZM241385 prevented liver fibrosis induced by the administration of CCl4 or thioacetamide [47]; moreover, neither of the profibrotic substances had any effect when they were administered to A2AR−/− but not A3AR−/− mice. Regarding these observations, it was proposed that in response to profibrotic agents, liver cells release ADO to the extracellular space to establish an autocrine-paracrine loop in which the nucleoside interacts with A2AR to favor fibrosis induction. In agreement, it was observed that in cultured liver sections, the administration of ethanol or methotrexate induced an increment in the release of ADO to the extracellular milieu [47]. These studies suggested that ADO released by a profibrotic stimulus, acting through A2AR, promoted liver fibrosis. Moreover, in liver damage induced by lipotoxicity and experimental non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), the pharmacological blocking of A2AR reduced liver damage by a pathway that inhibited JNK 1/2 activation [48].

On the other hand, the role of A1 adenosine receptors (A1AR) in fibrotic induction is controversial [49, 50]. In mice lacking this receptor (A1AR−/−), the induction of liver fibrosis (collagen accumulation and HSC activation) associated with CCl4 administration was attenuated [50]. Similar findings were observed during treatment with hepatotoxic α-naphthylisothiocyanate [49]; but when liver damage was induced by bile duct ligation (BDL), fibrosis was potentiated. Moreover, the gene expression pattern of A1AR−/− was differential in hepatic tissue when comparing CCl4 and BDL-treated animals [50]; this notable differential role of ADO signaling in response to a different type of damage reveals that diverse and plastic pathways lead to fibrosis and require specific characterization. Further, mice lacking A1AR were more susceptible to acute ethanol-induced liver damage than WT mice; this sensitivity was related to increased lipogenesis and lipid peroxidation as well as to the depletion of superoxide dismutase resulting in hepatic steatosis in these subjects [51].

Altogether, the available data make it possible to visualize that in liver damage induced by chemical toxins, such as CCl4, ADO establishes an autocrine-paracrine loop acting through A2AR and A1AR, but the role of the nucleoside in other hepatotoxic models is unclear. Information concerning the purinergic actions in liver damage are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Purinergic receptors in the liver damage

| Receptor or ligand | Injury | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| P2X | Diethylnitrosamine or CCl4 | Administration of the antagonist PPADS, inhibit expression of fibrotic markers | Dranoff et al. [39] |

| APAP-induced hepatotoxicity | Reduced hepatotoxicity after blockade of P2X receptors | Amaral et al. [52] | |

| P2X4 | Partial hepatectomy | P2X4−/− mice showed impaired biliary adaptation post hepatectomy | Besnard et al. [42] |

| P2X7 | APAP-induced hepatotoxicity | P2X7R antagonist, Brilliant Blue G, together with an antagonist for NF-κB, reduced hepatocellular injury and death | Abdelaziz et al. [53] |

| A438079 protected against liver injury, possibly through an effect upstream of inflammasome | Xie et al. [54] | ||

| Both, mice administered A438079 and P2X7R-deficient mice, presented decreased liver necrosis | Hoque et al. [55] | ||

| Ethanol-induced alcoholic liver disease | A438079 reduced chronic inflammation by preventing lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells | Shang et al. [56] | |

| CCl4-induced liver fibrosis | Administration of A438079 inhibited P2X7, collagen, SMA-α, and TGF-β expression, induced by CCl4 | Huang et al. [57] | |

| Non-alcoholic liver disease | ASC, IL-18, and NLRP3 KO mice showed increased severity of the disease | Henao-Mejía et al. [58] | |

| Steatohepatitis | Reduction of the activation of P2X7R was the protective effect found with berberine | Vivoli et al. [59] | |

| Sepsis-induced injury | Pharmacological blockade of P2X7R prevented tissue damage, apoptosis, and cytokine production | Savio et al. [45] | |

| Phthalate ester-induced liver injury | P2X7R inhibitor abolished NLRP3 expression and cleavage of caspase 1 and IL-1β | Ni et al. [60] | |

| Cholestatic injury | Injury induced by activation of NLRP3 in this model include participation of P2X7R | Gong et al. [61] | |

| P2Y2 | Partial hepatectomy | P2Y2−/− mice have a less proliferative rate in the early stage of liver regeneration | Tackett et al. [38] |

| Acute hepatitis induced by concanavalin A | P2Y2 is upregulated and P2Y2−/− showed reduced immune cell infiltration | Ayata et al. [40] | |

| A2AR |

CCl4 Thioacetamide Lipotoxicity NASH |

Antifibrotic effect of A2AR antagonist and no effect in A2AR−/− mice |

Chan et al. [47] Imarisio et al. [48] |

| A1AR | CCl4 | Fibrosis was attenuated in A1AR−/− mice |

Yang et al. [50] Yang et al. [49] |

| A1AR |

BDL Ethanol (acute) |

Fibrosis was potentiated in A1AR−/− mice | Yang et al. [51] |

| A2AR | Ethanol-induced injury | Antagonists of A2ARs inhibited HSCs activation | Szuster-Ciesielska et al. [62] |

| CD39 | Biliary fibrosis | CD39−/− mice show an increase in hepatic CD8+ T cells and exacerbated liver injury and fibrosis | Peng et al. [44] |

| Sepsis-induced liver injury | Expression of CD39 diminishes P2X7 inflammatory signaling and attenuates liver injury | Savio et al. [45] | |

| ENTPD2 | CCl4-induced and biliary-type fibrosis | Entpd2 null mice present more severe liver injury and fibrosis | Feldbrügge et al. [46] |

Purines as regulators of hepatic stellate cell activation

HSCs are resident mesenchymal liver cells located in the Disse space and are characterized by their ability to store vitamin A and secrete extracellular matrix elements; however, these cells are mostly known for their pivotal role in fibrosis. As a response to liver injury, HSCs transdifferentiate and activate to an MFB phenotype. MFBs lack vitamin A storage and express enhanced α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA). Activated MFBs promote the synthesis of type I collagen and are thus considered the main fibrogenic cells in liver damage [63].

ATP

Key studies done before cloning of purinergic receptors showed that the stimulation of isolated HSCs with purinergic ligands elicited inositol phosphate formation, increased the intracellular concentration of Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i), and induced phenotypic changes in HSCs. The potency order was UTP > ATP > ADP [64], clearly showing that HSCs expressed purinergic receptors mainly responsive to UTP, probably P2Y2 and/or P2Y4 receptors.

Molecular analysis confirmed the expression and functionality of P2Y receptors in HSCs: Quiescent HSCs expressed P2Y2 and P2Y4 and the ectonucleotidase NTPD-2; and their stimulation with ATP and UTP induced an increment in [Ca2+]i. Importantly, researchers observed that the fibrogenic process induced evident changes when HSCs were transformed into MFBs, since these cells lost the expression of both P2Y2 and P2Y4 and acquired P2Y6 expression. Similarly, MFB stimulation with UDP elicited an increment in [Ca2+]i as well as an augmented expression of the procollagen 1 transcript [65], suggesting a direct role for P2Y6 in the onset and maintenance of the fibrotic phenotype. In experiments of fibrosis induction in rats, the blockade of purinergic receptors with PPADS resulted in a reduced fibrotic response. In isolated HSCs, the antagonist prevented the phenotypic transformation and inhibited cell proliferation and the expression of procollagen-1 and fibronectin [39]. Altogether, these data suggest that the purinergic system is deeply modified during the activation of HSCs, and that the role played by P2Y receptors in MFB is profibrotic through positive regulation of procollagen I and α-SMA expression.

Similarly, purinergic receptor activation by different nucleotides (UTP being the most potent) in HSCs induced the synthesis of phosphatidic acid (PA) through activation of both phospholipase D (PLD) and the extracellular mitogen-activated kinases (ERK) [66]. However, the exact role of these signals promoting the phenotypic appearance of MFB is not well understood.

On the other hand, the purinergic ligand-gated channel P2X4 enabled the acquisition of the profibrotic phenotype of liver MFB, mainly from portal MFB and not from HSC-derived MFB. Signaling by this receptor regulated α-SMA accumulation, contraction capability, and lysosomal exocytosis of pro-fibrogenic messengers such as growth factors and interleukins (ILs) [43].

Adenosine

The role for ADO in HSC phenotype transformation is controversial. Some evidence supports the fact that ADO, acting through A2AR, induces HSC activation [62, 67–69]. In primary cultures of rat HSCs, the nucleoside was able to induce a concomitant increase of procollagen I and III transcripts and their respective proteins. The signal transduction pathway leading to these effects was analyzed in the human HSC line LX2, and it was found that the regulation of both collagen I and III depends on A2AR activation by a pathway that involves protein kinase A, Src, and ERK for collagen I and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases (p38-MAPK) for collagen III [69]. Similar findings were obtained in the HSC-derived cell line HSC-T6 [68] and in primary cultures of mouse HSCs [67].

Also, in the LX2 cell line, ADO blocked the intracellular Ca2+ increment and cell migration elicited by PDGF, a potent inducer of the proliferation and migration of this hepatic cell type [70], by activating A2AR. ADO also concomitantly induced the production of TGF-β and collagen I, indicating HSC activation. Altogether, these data support the idea that ADO is a profibrotic factor that could also function as a stop signal for the migration induced by PDGF when activated HSCs reach a damaged site [71].

Reports suggest that ADO participates as a permissive factor in the acetaldehyde-induced HSC activation since the incubation of quiescent rat HSCs with this metabolite promoted an increment in the transcripts for A2AR and A1AR while A2BR and A3R remained unchanged. Moreover, the acetaldehyde-dependent HSC activation was blocked by the antagonist for both A2AR or A1AR [72]. Nevertheless, the signal transduction pathway is still controversial because A2AR and A1AR are coupled to distinct G proteins; thus, researchers have not yet defined the mechanism(s) mediating the effects of extracellular ADO.

In apparent contradictory findings, the administration of the aspartate salt of ADO (IFC-305 compound) in primary cultures of rat HSCs maintained the quiescent phenotype, as revealed by cell morphology, the presence of lipid droplets, the inhibition of profibrotic proteins α-SMA and procollagen-1 expression, and the increment in the levels of anti-fibrogenic proteins MMP-13, Smad7, and PPARγ [73]. These findings were consistent with previous observations describing the reversion of CCl4-induced cirrhosis by systemic administration of IFC-305 in rats [74]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated in co-cultures that platelets can suppress HSC activation by releasing ATP and generating ADO, as was shown by the reduction of several fibrotic markers, such as α-SMA and type I collagen [75]. Table 2 provides information on purinergic action in non-parenchymal cells in liver damage.

Table 2.

Purinergic receptors in non-parenchymal cells

| Receptor or ligand | Phenotype in which they were detected | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

P2Y2 P2Y4 |

Quiescent HSC | UTP elicits an increment in [Ca2+]i | Dranoff et al. [65] |

| P2Y6 | Activated HSC | UDP elicits an increment in [Ca2+]i | Dranoff et al. [65] |

| P2X4 | Portal MFB but not HSC-derived MFB | Induces a profibrotic phenotype | Le Guilcher et al. [43] |

| P2X7 | Quiescent Kupffer cells | In hepatotoxic damage, cholestatic liver disease or cell exposure to nanoparticles induces the assembly of NLRP3 inflammasome |

Hoque et al. [55] Toki et al. [76] Gong et al. [61] Kojima et al. [77] |

| A2AR | Quiescent HSC | Mediates the acetaldehyde-induced HSC activation |

Che et al. [69] Szuster-Ciesielska et al. [62] Wang et al. (2014) Yamaguchi et al. [67] Yang et al. [72] |

| Aspartate salt of ADO (IFC-305 compound) acting through an unidentified adenosine receptor | Quiescent HSC | Maintains quiescent phenotype | Velasco-Loyden et al. [73] |

HSC hepatic stellate cells, MFB myofibroblasts, [Ca2+]i intracellular concentration of Ca2+

DAMPs, inflammation, and purinergic signaling

Inflammation and inflammasomes

As result of cellular or tissular injuries, damaged cells release distinct molecules that function as alert signals to trigger the innate immune response. These molecules, known as DAMPs, comprise a diverse group of factors such as foreign nucleic acids, uric acid, proteins like keratin-18, and nucleotides (mainly ATP) [78]. This primary response drives cells to release cytokines to induce inflammation. Release of IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-6 is a finely regulated two-step process: first, the synthesis and cytosolic accumulation of immature proteins that depend on the activation of transcriptional factor NF-κB; second, the proteolytic processing of immature proteins that is mediated by inflammasomes. If maturation does not occur, immature ILs will be subjected to proteasome-mediated degradation [79, 80].

DAMPs regulate the second stage of IL release, acting on a sophisticated machinery of proteins named inflammasomes. This machinery is comprised of the following: (1) an adapter protein named apoptosis-associated speck-like protein (Pycard-ASC) with a characteristic caspase association domain; (2) an effector enzyme, usually caspase-1 or caspase-11, involved in the proteolytic maturation of IL-18 and 1β [9]; and (3) the DAMP sensor protein. All these cytosolic proteins are receptors that are activated by specific signals (NLPR inflammasomes and its components have been reviewed elsewhere) [81–83].

Of particular interest for this review is the role played by ATP as a DAMP to regulate the inflammatory response through the assembly of the NLRP3 inflammasome. When a tissue is damaged, ATP is released to the extracellular space; since the intracellular concentration of ATP is of millimolar order and the volume of the extracellular compartment is small, the nucleotide reaches a high concentration in the extracellular space, sufficient to activate the low affinity purinergic receptor P2X7 [84]. P2X7 ligation induces the aggregation of the NLRP3 inflammasome that is the best characterized pathway driven by ATP acting as an inflammatory promoter. The main signal conducing to inflammasome assembly elicited by P2X7 is the K+ drop resulting from the efflux of this ion induced by P2X7 receptor activity [85–87]. Downstream of this K+ efflux, inflammasomes are assembled by binding the NEK7 kinase to the LRR of NLRP3; this interaction is necessary for the binding of ASC and caspase-1 to the whole complex [88, 89]. Besides, it has been demonstrated that although the P2X7 receptor is not a constituent of the inflammasome, it associates through protein-protein interactions with NLRP3 in discrete regions where the K+ drop is transduced to inflammasome activation, making the inflammatory response elicited by extracellular ATP more efficient [90].

Moreover, there is evidence that the P2X4 receptor contributes with inflammasome activation in renal disease and spinal cord injury, since the lack of this receptor or its pharmacological inhibition impairs the assembly of the inflammasome, suggesting collaborative actions with P2X7 and other factors in the inflammasome activation. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying these actions remain elusive [91, 92].

Inflammasomes and liver

A high concentration of nucleotides and nucleosides in the extracellular space during DAMP actions can regulate processes such as inflammation and immune responses in the liver [93] (Fig. 1). Pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β are both products of inflammasome signaling activation, and their presence in the liver has been detected in response to a challenge with LPS or APAP [94, 95]. Furthermore, an increased presence of the components of the inflammasome machinery, markedly mRNA of TRL4, NLRP3, CARD protein, and caspase-1, has been found in LPS-induced liver injury [96]. Moreover, the two-signal pathway of inflammasome activation has been observed in the liver during APAP-induced damage. Authors found that the hepatotoxic stimulus led to hepatocyte death, which triggered the activation of Tlr9 in sinusoidal endothelial cells and subsequent activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [97].

Hepatocytes are the first cells to respond when hepatocellular damage occurs. Studies have found the several elements of the inflammasome pathway expressed in these cells [98], although some evidence has suggested that the transcriptional activation of NLRP3 only occurs after an LPS challenge in primary rat hepatocytes [99]. Inflammasome pathway components, such as NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1, increase their protein expression level in an ethanol-induced liver injury in BRL-3A cells, a normal rat hepatocyte cell line [100], as well as in primary hepatocytes isolated from a model of NASH [101].

HSCs activation is induced in inflammatory environments such as those in many hepatic diseases that are associated with the liver inflammasome activation pathway. The activation of the inflammasome in HSCs mediates processes such as the expression of collagen-1 and the imbalance of ECM/MMP [102] that induces liver fibrosis in mice [103], in an NLRP3-dependent manner. NLRP3 inflammasome and fibrosis marker expression were also observed in primary HSCs and the LX-2 human HSC line of Schistosoma japonicum-infected mice [104].

KCs also become activated and drive an inflammatory response mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome upon liver cell damage [104]. IL-18 is an important regulatory cytokine that can induce the production of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and promote the secretion of other inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [105] and NLRP3 inflammasome activation is crucial for the maturation of IL-18, which can also be cleaved by caspase-1 following inflammasome activation. It has been observed that Kupffer macrophages release IL-18, following NLRP3 inflammasome activation, after liver injury induction using LPS. Notably, IL-18 release by Kupffer cells only occurred after sensitization with a bacterial pre-treatment [106].

P2X7

Activation of P2X7 receptor of the inflammasome pathway has been widely documented as a pro-inflammatory factor that contributes to the toxicity of several hepatic diseases (Fig. 1, Table 1). The P2X7 receptor can mediate the release of IL-1β as well as mRNA expression of several elements of the inflammasome activation pathway. In this work, authors have also described that an ATP-mediated stimulus can potentiate LPS-induced hepatotoxic response [107]. Furthermore, blockade of P2X7 with antagonist A438079 or P2X7R−/− mice showed significantly decreased APAP-induced necrosis [55]. Protective effects of the reduction of P2X7 activation in the inflammasome pathway were also seen in a murine model of steatohepatitis [108]. The mechanisms involved in the protective effects of the P2X7 blockade are not fully elucidated. Evidence has shown a direct effect on the downregulation of the inflammasome pathway and its components [109], but a modulatory interaction with the NF-κB pathway has also been suggested [53].

Activation of P2X7 by ATP in the extracellular space promotes the opening of membrane-bound pannexin-1 hemichannels, which have also been associated with the inflammatory response. It has been reported that pannexin-1 channels are necessary for the maturation and release of IL-1β, as well as for the recognition of bacterial products in the cytosol, in both dependent and independent of TLR signaling [110, 111]. In the liver, the expression of pannexin-1 hemichannels was found to increase after a challenge with LPS, in parallel with other components of the inflammasome [96].

Involvement of the P2X7 in inflammasome-mediated responses has also been described in the BRL-3A cell line. A blockade of this receptor, with knockdown techniques and A438079, was found to underlie the protective effects of zeaxanthin dipalmitate on ethanol-induced liver injury [109]. P2X7 receptor has also been associated with NLRP3 inflammasome activation in a phthalate ester-induced liver injury in L02 and HepG2 cells, a normal and transformed hepatocyte cell line, respectively [60].

Moreover, activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in Kupffer cells, and the concomitant release of IL-1β mediated by ATP, is dependent on the P2X7. The role played by this purinergic receptor was demonstrated using the pharmacological antagonist A438079 in a clonal mouse Kupffer cell line (KUP5) [76]. Others have also used P2X7-deficient mice in a model of hepatotoxicity [55] as well as in a model of cholestatic liver injury [61]. Similar findings were obtained from the P2X7 antagonist A438079 when KCs were exposed to nanoparticles, thus confirming their effects on inflammation [77].

Others groups have reported that A438079 may also have an effect upstream and independent of the inflammasome signaling; for example, by inhibiting P450 isoenzyme activities [54]. This result could be due to different release mechanisms for IL-1β after P2X7 receptor activation in inflammation, both dependent on and independent of inflammasome activation, in different types of macrophages [112, 113].

Other purinergic mediators

The accumulation and proportion of extracellular nucleotides can be a relevant factor during the activation of the inflammasome machinery; thus, the regulation of such dynamics by ectonucleotidases is crucial in the inflammation pathways. CD39 is an ectoenzyme capable of generating AMP and ADP from the breakdown of ATP, thus reducing nucleotide levels in the extracellular space. Accordingly, several authors have found that eliminating the activity of the CD39 ectonucleotidase promotes the elevation of ATP levels and increases liver injury in an acute model of sepsis and APAP-induced hepatotoxicity [45, 55].

Although P2X7 has been widely associated with inflammatory signaling responses, evidence has shown that P2Y receptors could also be implicated in the inflammation process. P2Y2 receptor expression in hepatocytes has been implicated in promoting neutrophil infiltration and cellular damage in a model of acute liver injury as an outcome of inflammation signaling [40].

Concluding remarks

Purinergic signaling is an extremely complex system that participates not only in regulating several processes in the various cell types within the liver, but also in the context of a cellular environment that is dynamically changing in response to a damaged or diseased state. Substantial evidence now shows that extracellular nucleotides and nucleosides are important mediators in hepatic disease and could potentially become pharmacological targets to regulate a variety of pathophysiological responses in the liver.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jessica González Norris for proofreading.

Funding information

This work was funded by PAPIIT-UNAM, number IN201017 to FGV-C and IN201618 to MD-M, and CONACyT-México, number 284-557 to MD-M.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

E. Velázquez-Miranda declares that he has no conflict of interest.

M. Díaz-Muñoz declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Francisco Gabriel Vázquez-Cuevas declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fustin J-M, Doi M, Yamada H, et al. Rhythmic nucleotide synthesis in the liver: temporal segregation of metabolites. Cell Rep. 2012;1:341–349. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ananian P, Hardwigsen J, Bernard D, Le Treut YP. Serum acute-phase protein level as indicator for liver failure after liver resection. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52(63):857–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rőszer T. The invertebrate midintestinal gland (“hepatopancreas”) is an evolutionary forerunner in the integration of immunity and metabolism. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;358:685–695. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-1985-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mataix Verdú J, Martínez de Vitoria E. Treaty of nutrition and feeding. Spain: OCEÁNO/ergon; 2009. Chapter 48. Liver and biliary tract; pp. 1355–1369. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jungermann K, Katz N. Functional specialization of different hepatocyte populations. Physiol Rev. 1989;69:708–764. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1989.69.3.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishibashi H, Nakamura M, Komori A, et al. Liver architecture, cell function, and disease. Semin Immunopathol. 2009;31:399–409. doi: 10.1007/s00281-009-0155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang G-P, Xu C-S. Reference gene selection for real-time RT-PCR in eight kinds of rat regenerating hepatic cells. Mol Biotechnol. 2010;46:49–57. doi: 10.1007/s12033-010-9274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez-Hernandez A, Amenta PS. The extracellular matrix in hepatic regeneration. FASEB J. 1995;9(14):1401–1410. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.14.7589981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-β. Mol Cell. 2002;10:417–426. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez-Hernandez A, Amenta PS. The hepatic extracellular matrix. I. Components and distribution in normal liver. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1993;423:1–11. doi: 10.1007/BF01606425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baiocchini A, Montaldo C, Conigliaro A, et al. Extracellular matrix molecular remodeling in human liver fibrosis evolution. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151736. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elpek GÖ. Cellular and molecular mechanisms in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis: an update. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7260–7276. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i23.7260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKillop IH, Moran DM, Jin X, Koniaris LG. Molecular pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Res. 2006;136:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burnstock G. Purinergic nerves. Pharmacol Rev. 1972;24:509–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Virgilio F, Vuerich M. Purinergic signaling in the immune system. Auton Neurosci. 2015;191:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, et al. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXI. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors—an update. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:1–34. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webb TE, Simon J, Krishek BJ, et al. Cloning and functional expression of a brain G-protein-coupled ATP receptor. FEBS Lett. 1993;324:219–225. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81397-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burnstock G, Kennedy C. Is there a basis for distinguishing two types of P2-purinoceptor? Gen Pharmacol. 1985;16:433–440. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(85)90001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling: from discovery to current developments. Exp Physiol. 2014;99:16–34. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.071951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Kügelgen I, Harden TK. Molecular pharmacology, physiology, and structure of the P2Y receptors. Adv Pharmacol. 2011;61:373–415. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385526-8.00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonora M, Patergnani S, Rimessi A, et al. ATP synthesis and storage. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8:343–357. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9305-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramzan R, Staniek K, Kadenbach B, Vogt S. Mitochondrial respiration and membrane potential are regulated by the allosteric ATP-inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:1672–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui JD, Xu ML, Liu EYL, et al. Expression of globular form acetylcholinesterase is not altered in P2Y1R knock-out mouse brain. Chem Biol Interact. 2016;259:291–294. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2016.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braun M, Wendt A, Karanauskaite J, et al. Corelease and differential exit via the fusion pore of GABA, serotonin, and ATP from LDCV in rat pancreatic beta cells. J Gen Physiol. 2007;129:221–231. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pablo Huidobro-Toro J, Verónica Donoso M. Sympathetic co-transmission: the coordinated action of ATP and noradrenaline and their modulation by neuropeptide Y in human vascular neuroeffector junctions. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;500:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi RCY, Siow NL, Cheng AWM, et al. ATP acts via P2Y1 receptors to stimulate acetylcholinesterase and acetylcholine receptor expression: transduction and transcription control. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4445–4456. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04445.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cotrina ML, Lin JH, López-García JC, et al. ATP-mediated glia signaling. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2835–2844. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02835.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abudara V, Retamal MA, Del Rio R, Orellana JA. Synaptic functions of hemichannels and pannexons: a double-edged sword. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11:435. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elliott MR, Chekeni FB, Trampont PC, et al. Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance. Nature. 2009;461:282–286. doi: 10.1038/nature08296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Idzko M, Ferrari D, Eltzschig HK. Nucleotide signalling during inflammation. Nature. 2014;509:310–317. doi: 10.1038/nature13085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zimmermann H, Zebisch M, Sträter N. Cellular function and molecular structure of ecto-nucleotidases. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8:437–502. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9309-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G, Verkhratsky A, Zimmermann H. Purinergic signalling in the nervous system: an overview. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martínez-Ramírez AS, Vázquez-Cuevas FG. Purinergic signaling in the ovary. Mol Reprod Dev. 2015;82:839–848. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burnstock G, Verkhratsky A. Long-term (trophic) purinergic signalling: purinoceptors control cell proliferation, differentiation and death. Cell Death Dis. 2010;1:e9. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2009.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dixon CJ, White PJ, Hall JF, et al. Regulation of human hepatocytes by P2Y receptors: control of glycogen phosphorylase, Ca2+, and mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:1305–1313. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.082743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thevananther S, Sun H, Li D, et al. Extracellular ATP activates c-jun N-terminal kinase signaling and cell cycle progression in hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2004;39:393–402. doi: 10.1002/hep.20075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keppens S, De Wulf H. Characterization of the liver P2-purinoceptor involved in the activation of glycogen phosphorylase. Biochem J. 1986;240:367–371. doi: 10.1042/bj2400367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tackett BC, Sun H, Mei Y, et al. P2Y2 purinergic receptor activation is essential for efficient hepatocyte proliferation in response to partial hepatectomy. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;307:G1073–G1087. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00092.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dranoff JA, Kruglov EA, Abreu-Lanfranco O, et al. Prevention of liver fibrosis by the purinoceptor antagonist pyridoxal-phosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonate (PPADS) In Vivo. 2007;21:957–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ayata CK, Ganal SC, Hockenjos B, et al. Purinergic P2Y2 receptors promote neutrophil infiltration and hepatocyte death in mice with acute liver injury. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1620–1629. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emmett DS, Feranchak A, Kilic G, et al. Characterization of ionotrophic purinergic receptors in hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2008;47:698–705. doi: 10.1002/hep.22035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Besnard A, Gautherot J, Julien B, et al. The P2X4 purinergic receptor impacts liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in mice through the regulation of biliary homeostasis. Hepatology. 2016;64:941–953. doi: 10.1002/hep.28675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Le Guilcher C, Garcin I, Dellis O, et al. The P2X4 purinergic receptor regulates hepatic myofibroblast activation during liver fibrogenesis. J Hepatol. 2018;69:644–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peng Z-W, Rothweiler S, Wei G, et al. The ectonucleotidase ENTPD1/CD39 limits biliary injury and fibrosis in mouse models of sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatol Commun. 2017;1:957–972. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Savio LEB, de Andrade MP, Figliuolo VR, et al. CD39 limits P2X7 receptor inflammatory signaling and attenuates sepsis-induced liver injury. J Hepatol. 2017;67:716–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feldbrügge L, Jiang ZG, Csizmadia E, et al. Distinct roles of ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-2 (NTPDase2) in liver regeneration and fibrosis. Purinergic Signal. 2018;14:37–46. doi: 10.1007/s11302-017-9590-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chan ESL, Montesinos MC, Fernandez P, et al. Adenosine A(2A) receptors play a role in the pathogenesis of hepatic cirrhosis. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:1144–1155. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Imarisio C, Alchera E, Sutti S, et al. Adenosine A(2a) receptor stimulation prevents hepatocyte lipotoxicity and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in rats. Clin Sci. 2012;123:323–332. doi: 10.1042/CS20110504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang P, Chen P, Wang T, et al. Loss of A(1) adenosine receptor attenuates alpha-naphthylisothiocyanate-induced cholestatic liver injury in mice. Toxicol Sci. 2013;131:128–138. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang P, Han Z, Chen P, et al. A contradictory role of A1 adenosine receptor in carbon tetrachloride- and bile duct ligation-induced liver fibrosis in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;332:747–754. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.162727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang P, Wang Z, Zhan Y, et al. Endogenous A1 adenosine receptor protects mice from acute ethanol-induced hepatotoxicity. Toxicology. 2013;309:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Amaral Sylvia S, Oliveira André G, Marques Pedro E, Quintão Jayane L D, Pires Daniele A, Resende Rodrigo R, Sousa Bruna R, Melgaço Juliana G, Pinto Marcelo A, Russo Remo C, Gomes Ariane K C, Andrade Lidia M, Zanin Rafael F, Pereira Rafaela V S, Bonorino Cristina, Soriani Frederico M, Lima Cristiano X, Cara Denise C, Teixeira Mauro M, Leite Maria F, Menezes Gustavo B. Altered responsiveness to extracellular ATP enhances acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Cell Communication and Signaling. 2013;11(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-11-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abdelaziz HA, Shaker ME, Hamed MF, Gameil NM. Repression of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity by a combination of celastrol and brilliant blue G. Toxicol Lett. 2017;275:6–18. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xie Y, Williams CD, McGill MR, et al. Purinergic receptor antagonist A438079 protects against acetaminophen-induced liver injury by inhibiting p450 isoenzymes, not by inflammasome activation. Toxicol Sci. 2013;131:325–335. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoque R, Sohail MA, Salhanick S, et al. P2X7 receptor-mediated purinergic signaling promotes liver injury in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G1171–G1179. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00352.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shang Y, Li XF, Jin MJ, Li Y, Wu YL, Jin Q, Zhang Y, Li X, Jiang M, Cui BW, Lian LH, Nan JX (2018) Leucodin attenuates inflammatory response in macrophages and lipid accumulation in steatotic hepatocytes via P2x7 receptor pathway: A potential role in alcoholic liver disease. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 107:374–381 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.HUANG CHANGSHAN, YU WEI, CUI HONG, WANG YUNJIAN, ZHANG LING, HAN FENG, HUANG TAO. P2X7 blockade attenuates mouse liver fibrosis. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2013;9(1):57–62. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Henao-Mejia Jorge, Elinav Eran, Jin Chengcheng, Hao Liming, Mehal Wajahat Z., Strowig Till, Thaiss Christoph A., Kau Andrew L., Eisenbarth Stephanie C., Jurczak Michael J., Camporez Joao-Paulo, Shulman Gerald I., Gordon Jeffrey I., Hoffman Hal M., Flavell Richard A. Inflammasome-mediated dysbiosis regulates progression of NAFLD and obesity. Nature. 2012;482(7384):179–185. doi: 10.1038/nature10809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vivoli E., Cappon A., Milani S., Piombanti B., Provenzano A., Novo E., Masi A., Navari N., Narducci R., Mannaioni G., Moneti G., Oliveira C. P., Parola M., Marra F. NLRP3 inflammasome as a target of berberine in experimental murine liver injury: interference with P2X7 signalling. Clinical Science. 2016;130(20):1793–1806. doi: 10.1042/CS20160400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ni J, Zhang Z, Luo X, et al. Plasticizer DBP activates NLRP3 inflammasome through the P2X7 receptor in HepG2 and L02 cells. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2016;30:178–185. doi: 10.1002/jbt.21776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gong Z, Zhou J, Zhao S, et al. Chenodeoxycholic acid activates NLRP3 inflammasome and contributes to cholestatic liver fibrosis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:83951–83963. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Szuster-Ciesielska A, Sztanke K, Kandefer-Szerszeń M. A novel fused 1,2,4-triazine aryl derivative as antioxidant and nonselective antagonist of adenosine A(2A) receptors in ethanol-activated liver stellate cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2012;195:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Friedman SL. Hepatic stellate cells: protean, multifunctional, and enigmatic cells of the liver. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:125–172. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Takemura S, Kawada N, Hirohashi K, et al. Nucleotide receptors in hepatic stellate cells of the rat. FEBS Lett. 1994;354:53–56. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dranoff JA, Ogawa M, Kruglov EA, et al. Expression of P2Y nucleotide receptors and ectonucleotidases in quiescent and activated rat hepatic stellate cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G417–G424. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00294.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Benitez-Rajal J, Lorite M-J, Burt AD, et al. Phospholipase D and extracellular signal-regulated kinase in hepatic stellate cells: effects of platelet-derived growth factor and extracellular nucleotides. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G977–G986. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00041.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamaguchi M, Saito S-Y, Nishiyama R, et al. Caffeine suppresses the activation of hepatic stellate cells cAMP-independently by antagonizing adenosine receptors. Biol Pharm Bull. 2017;40:658–664. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b16-00947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang H, Guan W, Yang W, et al. Caffeine inhibits the activation of hepatic stellate cells induced by acetaldehyde via adenosine A2A receptor mediated by the cAMP/PKA/SRC/ERK1/2/P38 MAPK signal pathway. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92482. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Che J, Chan ESL, Cronstein BN. Adenosine A2A receptor occupancy stimulates collagen expression by hepatic stellate cells via pathways involving protein kinase A, Src, and extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 signaling cascade or p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:1626–1636. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.038760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pinzani M. PDGF and signal transduction in hepatic stellate cells. Front Biosci. 2002;7:d1720–d1726. doi: 10.2741/A875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hashmi AZ, Hakim W, Kruglov EA, et al. Adenosine inhibits cytosolic calcium signals and chemotaxis in hepatic stellate cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G395–G401. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00208.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang Y, Wang H, Lv X, et al. Involvement of cAMP-PKA pathway in adenosine A1 and A2A receptor-mediated regulation of acetaldehyde-induced activation of HSCs. Biochimie. 2015;115:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Velasco-Loyden G, Pérez-Carreón JI, Agüero JFC, et al. Prevention of in vitro hepatic stellate cells activation by the adenosine derivative compound IFC305. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:1690–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pérez-Carreón JI, Martínez-Pérez L, Loredo ML, et al. An adenosine derivative compound, IFC305, reverses fibrosis and alters gene expression in a pre-established CCl(4)-induced rat cirrhosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ikeda N, Murata S, Maruyama T, et al. Platelet-derived adenosine 5′-triphosphate suppresses activation of human hepatic stellate cell: in vitro study. Hepatol Res. 2011;42:91–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Toki Y, Takenouchi T, Harada H, et al. Extracellular ATP induces P2X7 receptor activation in mouse Kupffer cells, leading to release of IL-1β, HMGB1, and PGE2, decreased MHC class I expression and necrotic cell death. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;458:771–776. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kojima S, Negishi Y, Tsukimoto M, et al. Purinergic signaling via P2X7 receptor mediates IL-1β production in Kupffer cells exposed to silica nanoparticle. Toxicology. 2014;321:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mihm S. Danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs): molecular triggers for sterile inflammation in the liver. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:E3104. doi: 10.3390/ijms19103104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Englezou PC, Rothwell SW, Ainscough JS, et al. P2X7R activation drives distinct IL-1 responses in dendritic cells compared to macrophages. Cytokine. 2015;74:293–304. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ainscough JS, Frank Gerberick G, Zahedi-Nejad M, et al. Dendritic cell IL-1α and IL-1β are polyubiquitinated and degraded by the proteasome. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:35582–35592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.595686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ting JP-Y, Lovering RC, Alnemri ES, et al. The NLR gene family: a standard nomenclature. Immunity. 2008;28:285–287. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Davis BK, Wen H, Ting JP-Y. The inflammasome NLRs in immunity, inflammation, and associated diseases. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:707–735. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Di Virgilio F. The therapeutic potential of modifying inflammasomes and NOD-like receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;65:872–905. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.006171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Coddou C, Yan Z, Obsil T, et al. Activation and regulation of purinergic P2X receptor channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:641–683. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Muñoz-Planillo R, Kuffa P, Martínez-Colón G, et al. K+ efflux is the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins and particulate matter. Immunity. 2013;38:1142–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pétrilli V, Papin S, Dostert C, et al. Activation of the NALP3 inflammasome is triggered by low intracellular potassium concentration. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1583–1589. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Perregaux D, Gabel CA. Interleukin-1 beta maturation and release in response to ATP and nigericin. Evidence that potassium depletion mediated by these agents is a necessary and common feature of their activity. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15195–15203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shi H, Wang Y, Li X, et al. NLRP3 activation and mitosis are mutually exclusive events coordinated by NEK7, a new inflammasome component. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:250–258. doi: 10.1038/ni.3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.He Y, Zeng MY, Yang D, et al. NEK7 is an essential mediator of NLRP3 activation downstream of potassium efflux. Nature. 2016;530:354–357. doi: 10.1038/nature16959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Franceschini A, Capece M, Chiozzi P, et al. The P2X7 receptor directly interacts with the NLRP3 inflammasome scaffold protein. FASEB J. 2015;29:2450–2461. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-268714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.de Rivero Vaccari JP, Bastien D, Yurcisin G, et al. P2X4 receptors influence inflammasome activation after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2012;32:3058–3066. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4930-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chen K, Zhang J, Zhang W, et al. ATP-P2X4 signaling mediates NLRP3 inflammasome activation: a novel pathway of diabetic nephropathy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45:932–943. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Burnstock G, Vaughn B, Robson SC. Purinergic signalling in the liver in health and disease. Purinergic Signal. 2014;10:51–70. doi: 10.1007/s11302-013-9398-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cover C, Liu J, Farhood A, et al. Pathophysiological role of the acute inflammatory response during acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;216:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lang CH, Silvis C, Deshpande N, et al. Endotoxin stimulates in vivo expression of inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-1beta, -6, and high-mobility-group protein-1 in skeletal muscle. Shock. 2003;19:538–546. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000055237.25446.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ganz M, Csak T, Nath B, Szabo G. Lipopolysaccharide induces and activates the Nalp3 inflammasome in the liver. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4772–4778. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i43.4772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Imaeda AB, Watanabe A, Sohail MA, et al. Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice is dependent on Tlr9 and the Nalp3 inflammasome. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:305–314. doi: 10.1172/JCI35958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Masumoto J, Taniguchi S, Nakayama J, et al. Expression of apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain, a pyrin N-terminal homology domain-containing protein, in normal human tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 2001;49:1269–1275. doi: 10.1177/002215540104901009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Boaru SG, Borkham-Kamphorst E, Tihaa L, et al. Expression analysis of inflammasomes in experimental models of inflammatory and fibrotic liver disease. J Inflamm (Lond) 2012;9:49. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-9-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Xiao J, Zhu Y, Liu Y, et al. Lycium barbarum polysaccharide attenuates alcoholic cellular injury through TXNIP-NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Int J Biol Macromol. 2014;69:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Csak T, Ganz M, Pespisa J, et al. Fatty acid and endotoxin activate inflammasomes in mouse hepatocytes that release danger signals to stimulate immune cells. Hepatology. 2011;54:133–144. doi: 10.1002/hep.24341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Watanabe A, Sohail MA, Gomes DA, et al. Inflammasome-mediated regulation of hepatic stellate cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G1248–G1257. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90223.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Inzaugarat ME, Johnson CD, Holtmann TM, et al. NLR family pyrin domain-containing 3 inflammasome activation in hepatic stellate cells induces liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology. 2019;69:845–859. doi: 10.1002/hep.30252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang W-J, Fang Z-M, Liu W-Q. NLRP3 inflammasome activation from Kupffer cells is involved in liver fibrosis of Schistosoma japonicum-infected mice via NF-κB. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:29. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-3223-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wang F, Guan M, Wei L, Yan H. IL-18 promotes the secretion of matrix metalloproteinases in human periodontal ligament fibroblasts by activating NF-κB signaling. Molecular Medicine Reports; Athens. 2019;19:703. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.9697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Imamura M, Tsutsui H, Yasuda K, et al. Contribution of TIR domain-containing adapter inducing IFN-beta-mediated IL-18 release to LPS-induced liver injury in mice. J Hepatol. 2009;51:333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Jiang S, Zhang Y, Zheng J-H, et al. Potentiation of hepatic stellate cell activation by extracellular ATP is dependent on P2X7R-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Pharmacol Res. 2017;117:82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Vivoli E, Cappon A, Milani S, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome as a target of berberine in experimental murine liver injury: interference with P2X7 signalling. Clin Sci. 2016;130:1793–1806. doi: 10.1042/CS20160400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gao H, Lv Y, Liu Y, et al. Wolfberry‐derived zeaxanthin dipalmitate attenuates ethanol‐induced hepatic damage. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2019;63:e1801339. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201801339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kanneganti TD, Lamkanfi M, Kim YG, et al. Pannexin-1-mediated recognition of bacterial molecules activates the cryopyrin inflammasome independent of Toll-like receptor signaling. - PubMed - NCBI. Immunity. 2007;26(4):433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Pelegrin P, Surprenant A. Pannexin-1 mediates large pore formation and interleukin-1beta release by the ATP-gated P2X7 receptor. EMBO J. 2006;25:5071–5082. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gicquel T, Victoni T, Fautrel A, et al. Involvement of purinergic receptors and NOD-like receptor-family protein 3-inflammasome pathway in the adenosine triphosphate-induced cytokine release from macrophages. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;41:279–286. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Pelegrin P, Barroso-Gutierrez C, Surprenant A. P2X7 receptor differentially couples to distinct release pathways for IL-1beta in mouse macrophage. J Immunol. 2008;180:7147–7157. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]