Abstract

Background

Diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone), labeled with 64Cu (64Cu-ATSM) has been suggested as a promising tracer for imaging hypoxia. However, various controversial studies highlighted potential pitfalls that may disable its use as a selective hypoxic marker. They also highlighted that the results may be tumor location dependent. Here, we first analyzed uptake of Cu-ATSM and its less lipophilic counterpart Cu-Cl2 in the tumor over time in an orthotopic glioblastoma model. An in vitro study was also conducted to investigate the hypoxia-dependent copper uptake in tumor cells. We then further performed a comprehensive ex vivo study to compare 64Cu uptake to hypoxic markers, specific cellular reactions, and also transporter expression.

Methods

μPET was performed 14 days (18F-FMISO), 15 days (64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-Cl2), and 16 days (64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-Cl2) after C6 cell inoculation. Thereafter, the brains were withdrawn for further autoradiography and immunohistochemistry. C6 cells were also grown in hypoxic workstation to analyze cellular uptake of Cu complexes in different oxygen levels.

Results

In vivo results showed that Cu-ASTM and Cu-Cl2 accumulated in hypoxic areas of the tumors. Cu-ATSM also stained, to a lesser extent, non-hypoxic regions, such as regions of astrogliosis, with high expression of copper transporters and in particular DMT-1 and CTR1, and also characterized by the expression of elevated astrogliosis. In vitro results show that 64Cu-ATSM showed an increase in the uptake only in severe hypoxia at 0.5 and 0.2% of oxygen while for 64Cu-Cl2, the cell retention was significantly increased at 5% and 1% of oxygen with no significant rise at lower oxygen percentages.

Conclusion

In the present study, we show that Cu-complexes undoubtedly accumulate in hypoxic areas of the tumors. This uptake may be the reflection of a direct dependency to a redox metabolism and also a reflection of hypoxic-induced overexpression of transporters. We also show that Cu-ATSM also stained non-hypoxic regions such as astrogliosis.

Keywords: Hypoxia, Brain tumors, Cu-ATSM, PET radiotracers, Copper transporters

Background

Hypoxia, resulting from an inadequacy between oxygen supply and demand, is noticeably pronounced in various solid tumors such as glioblastoma (GB). While in the normal brain oxygen pressure ranges between 30 and 60 mmHg, it is suspected to be less than 10 mmHg in hypoxic brain tumors and can be less than 1 mmHg in some tumor areas [1, 2].

At the cellular level, hypoxia triggers numerous responses, in part mediated by the activation of the family of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs). HIFs are transcription factors that, in turn, induce the expression of various genes involved in several processes known to participate in tumor growth such as angiogenesis, regulation of intracellular pH, regulation of oxidative metabolism, glycolytic metabolism, invasion, and apoptosis. As a whole, hypoxia and the activation of the HIFs transcription factor is a factor of poor prognosis, in the context of solid tumors and particularly in glioblastoma [3, 4].

Hypoxia also induces resistance to anti-cancer treatments. Original experiments in the early 50s already demonstrated the importance of the oxygen effect in X-rays’ efficacy with the generation of reactive oxygen species. Thereby, hypoxia is involved in tumor radioresistance [5]. In addition, the efficacy of various chemotherapies is also linked to the presence of oxygen [6, 7].

At the tissue level, it is now demonstrated that hypoxia is not a binary effect and that intratumor gradients exist. The concept of diffusion limited hypoxia also referred to as chronic hypoxia (i.e., the ability of oxygen to diffuse from the nearest capillary, which represents a distance of ~ 70 μm) was described 70 years ago. More recently, the concept of perfusion limited hypoxia (also referred to as acute and cycling, dynamic hypoxia) resulting from blood obstruction, altered blood flow, poorly oxygenated blood, and increased transit time has been proposed [8]. The observation that hypoxia is heterogeneous over the tumor mass and also in time opens the avenue for more adapted treatments requiring more specific and/or sensitive imaging of hypoxia.

Various methods have been proposed to map hypoxia (see [9] for review) and various radiopharmaceuticals that could be used for positron emission tomography (PET) have been proposed. As examples, nitro-imidazole compounds have been extensively studied and 3-18F-fluoro-1-(2-nitro-1-imidazolyl)-2-propanol (18F-FMISO) has appeared as one of the most efficient tracers to non-invasively map hypoxia in brain tumors. Nitro-imidazole compounds enter in all cells where it suffers reductions. It is not a stable compounds in this state and then is either reoxidized if oxygen is present or binds to macromolecule if not oxygen is present in the cell. However, 18F-FMISO suffers from some drawbacks. It is sensitive to severe hypoxia (less than 10 mmHg) and fails to reveal regions with moderate to mild hypoxia [10]. FMISO may be sensitive to low potential redox. A low tumor-to-background contrast resulting from a low clearance in normoxic tissue and a low lipophilia is also an additional drawback. Moreover, the short half-life of 18F (109 min) also raises the problem of large-scale spread of this hypoxia imaging marker. In contrast, while the relationship between 18F-FMISO uptake and ptO2 is not linear, it is a robust and reproducible hypoxic marker thanks to its nitro-imidazole moiety.

More recently, diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone), labeled with various positron-emitting isotopes of copper, such as 64Cu-diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) (64Cu-ATSM), has been suggested as a promising tracer for imaging hypoxia due to its high membrane permeability and low redox potential [11, 12]. ATSM confers lipophilic properties to the molecule in comparison to 64Cu-Cl2. In the context of brain tumors, a good correlation was observed between 64Cu-ATSM and 18F-FMISO PET imaging [13], and also between high 64Cu-ATSM uptake and low pO2 [14]. Significant correlations between 62Cu-ATSM and HIF staining were also observed [15] in clinical situation, and this tracer has been recently proposed as an independent prognostic biomarker of survival in high-grade glioma [16]. However, the selectivity of 64Cu-ATSM to hypoxia has been challenged. As an example, in a study comparing four tracers of hypoxia in a single xenograft model chosen for its regional heterogeneity, 64Cu-ATSM failed to correlate to pimonidazole and carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) staining while the other three tracers did [17]. Likewise, studies on the microscopic intratumor distribution of 64Cu-ATSM showed no correlation between this radiotracer and hypoxia marker (pimonidazole) or perfusion marker (Hoechst-33342) [18]. Moreover, in the presence of hypercapnic gasses known to reduce intratumor hypoxia, Yuan and Colleagues failed to show significant changes in the uptake of Cu-ATSM [19]. It is worth mentioning that all experiments conducted on brain tumor model have been performed ectopically (in the flank) so far, and it is therefore necessary to study whether Cu-ATSM uptake is specific for hypoxia in an orthotopic model. Consequently, debates remain on the selectivity of 64Cu-ATSM to hypoxia, and several preclinical studies have focused on better understanding uptake and retention under hypoxic conditions.

Fujibayashi and his collaborators first proposed that the reduction of Cu(II) in Cu(I) would only occur in hypoxic cells because of the abnormally reduced state of their mitochondria [12]. Furthermore, it was also demonstrated that NADH and NADPH [12, 20] and also over-reduced states caused by mitochondrial dysfunction even in normoxia [21] were involved in the production of Cu(I). Cu(I) would dissociate slowly from the ATSM ligand in cells with low oxygen concentration, becoming irreversibly trapped. Intriguingly, Dearling and colleagues observed that retention of Cu-ATSM was partially reversible in hypoxic cells [22]. The selectivity to hypoxia would therefore be a competition between dissociation and re-oxidation of the reduced copper complexes. Holland and colleagues also proposed a revised mechanism that may influence the degree of Cu-ASTM uptake based on protonation leading to intracellular release of the copper ion and thereby forms mono-or di-protonated complexes which governs the in vivo behavior [23].

Burgman and colleagues demonstrated the efflux and decrease in 64Cu-ATSM in anoxic and hypoxic prostate tumor cells, in contradiction with models that suggest irreversible trapping under low-oxygen concentration conditions [24]. The authors proposed that after dissociation of Cu(I) and ATSM, Cu(I) would not be trapped but absorbed in the intracellular pool of copper and be subjected to cellular metabolism of copper. The level of expression and regulation of its transporters could vary with cell types, which may explain variations in copper retention. Thus, membrane transporters such as multidrug resistance protein 1 (MDR1) or other specific copper transporters in particular copper transporter 1 (CTR1) and divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) could also influence the retention of copper [25].

All together, these data suggest that further experiments are required to further assess the specificity of 64Cu-ATSM as an imaging marker of hypoxia, in particular in the context of brain tumors. Here, the selectivity of 64Cu-ATSM with respect to hypoxia was studied, at the preclinical level, in a glioblastoma (GB) model. By combining different experimental approaches, the specificity of 64Cu-ATSM for hypoxia was evaluated in vivo by PET imaging and compared to 18F-FMISO (the reference radiotracer for hypoxia) and 64Cu-Cl2 (used as a control of copper). In addition, cell retention of 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu Cl2 were determined in vitro in various oxygenation conditions. Imaging results were also supported by ex vivo autoradiography studies of brain sections of GB-bearing rats and immunolabeling for different hypoxia-induced proteins and copper transporters.

Methods

In vivo studies

Ethics statement

The animal investigations were performed under the current European directive (2010/63/EU) in authorized laboratories (B14118001) and with the permission of the regional committee on animal ethics (CENOMEXA, APAFIS#1247). Data are reported according to ARRIVE guidelines. The global protocol is detailed l in Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Tumor models

The C6 cell line was purchased from ATCC (American Type Culture Collection). Tumor cells were cultured in DMEM 4.5 g/l glucose (Sigma-Aldrich, France) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (InVitrogen, France), 2 mM glutamine (Gln) (Sigma-Aldrich, France), and 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin (PS) (InVitrogen, France). Male Wistar rats (6–8 weeks old, n = 6 for PET 18F-FMISO/64Cu-ATSM and n = 11 for Cu-Cl2) were purchased from Janvier Labs (Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France). Isoflurane anesthesia was used for the rats (5% for induction and 2% for maintenance in 70% N2O/30% O2). Rectal temperature was monitored and maintained around 37.0 °C throughout the experiments as already described [26]. Rats were placed on a stereotactic head holder and a sagittal scalp incision was performed. A 1-mm diameter burr hole was drilled in the calvarium, 3 mm lateral to the bregma. C6 (1.105), in 3-μl PBS-glutamine 2 mM were injected over 6 min via a fine needle (30 G) connected to a Hamilton syringe. The injection site was the right caudate-putamen, at a depth of 6 mm beneath the calvarium. The needle was removed slowly 5 min after the end of the injection, and the burr hole was sealed with dental cement.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI was performed on day 2 using a 7-T horizontal magnet (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany; CYCERON biomedical imaging platform). A cross coil configuration was used (volume/surface coil, Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany).

After scout imaging, an anatomical exploration of the brain was performed using a T2w sequence (RARE, acceleration factor of 8; TR/TEeff = 5000/62.5 ms; Number of EXperiments (NEX) = 1; 20 contiguous slices; resolution = 0.15 × 0.15 × 0.75 mm; acquisition time = 2 min). TR and TE are respectively repetition time and echo time.

Positron emission tomography (PET)

On day 1, 18F-FMISO (produced by the LDM-TEP group, ISTCT) was intravenously injected in physiological saline (≈ 66 MBq.kg−1). At t = 1.5 h, the rats were transferred into the PET camera (Inveon®, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany; CYCERON biomedical imaging platform). An X-ray scan was first performed to obtain attenuation maps just prior to an emission scan of 20 min initiated at t = 2 h.

On day 0, 64Cu-ATSM (287 μCi/nmol) or 64Cu-Cl2 (276 μCi/nmol) (produced by ARRONAX, Nantes, France) were intravenously injected (≈ 90 MBq.kg−1), and PET imaging were performed at 3 h and 24 h (day+1) after the attenuation acquisition. All images were reconstructed by the iterative OSEM-2D algorithm. For some animals, a dynamic acquisition lasting 2 h and 20 min was performed. In parallel, blood samples were withdrawn for arterial input function determination over a period of 2 h.

Following the late acquisition (i.e., 24 h post-injection), rats were injected with a pimonidazole solution (Hypoxyprobe®-1, Hypoxyprobe Incorporation, USA) of 80 mg/kg i.p., 120 min before the animals were euthanized under deep anesthesia just after the completion of PET imaging examinations. Following the last PET session, the rat brains were withdrawn and immediately snap-frozen for subsequent autoradiography and immunohistochemistry.

Ex vivo studies

Autoradiography

Series of coronal sections (20 μm) were cut on a cryostat (Leica, Germany). Digital autoradiography was prepared by placing tissue section in a film cassette against a phosphor imaging plate for an overnight exposure. Phosphor imaging plates were then read at a pixel resolution of 50 μm with a Cyclone analyzer (PerkinElmer). Adjacent slices were used for immunohistochemistry studies.

Immunohistochemistry

First, slices were post-fixated in cold acetone for 10 min, then the nonspecific binding sites were blocked by bovine serum albumin (BSA) 3%/Tween 0.1%/Triton 0.5% in PBS solution for 90 min at room temperature. The slices were incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4 °C in BSA 1%/Tween 0.1%/Triton 0.5% in PBS solution (Additional file 2: Table S1), and the staining was revealed by fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies (Additional file 2: Table S1). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich, 10 μg/ml). Tissue sections were examined at × 10 magnification with a Leica DM6000, and whole brain slices were reconstructed using mosaic acquisitions (MetaMorph software).

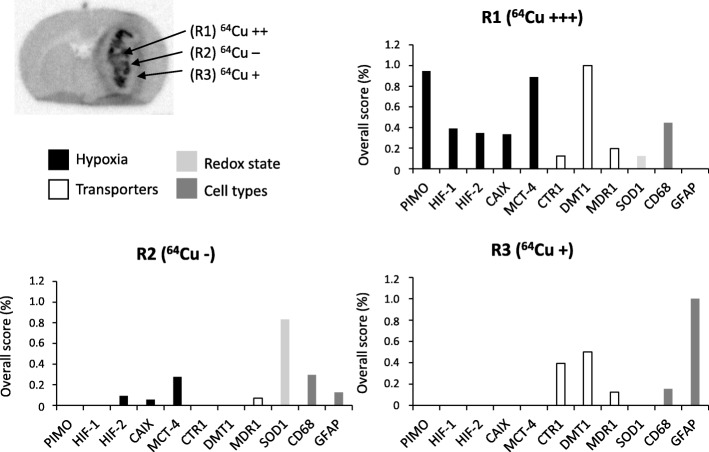

Quantification of immunohistochemistry

After co-registration of immunohistochemistry and autoradiography images for all rats (n = 9), a visual inspection was used for each region named (R1, R2, and R3 as presented on Fig. 4a). For each staining, two parameters were quantified: the number of positive samples determined when staining was visually detected and the staining intensity by assigning a score equivalent to 1 or 2 for low and high expression, respectively. Then, a global score, including all rats, was measured for each staining by multiplying the number of positive samples and total score of intensity staining.

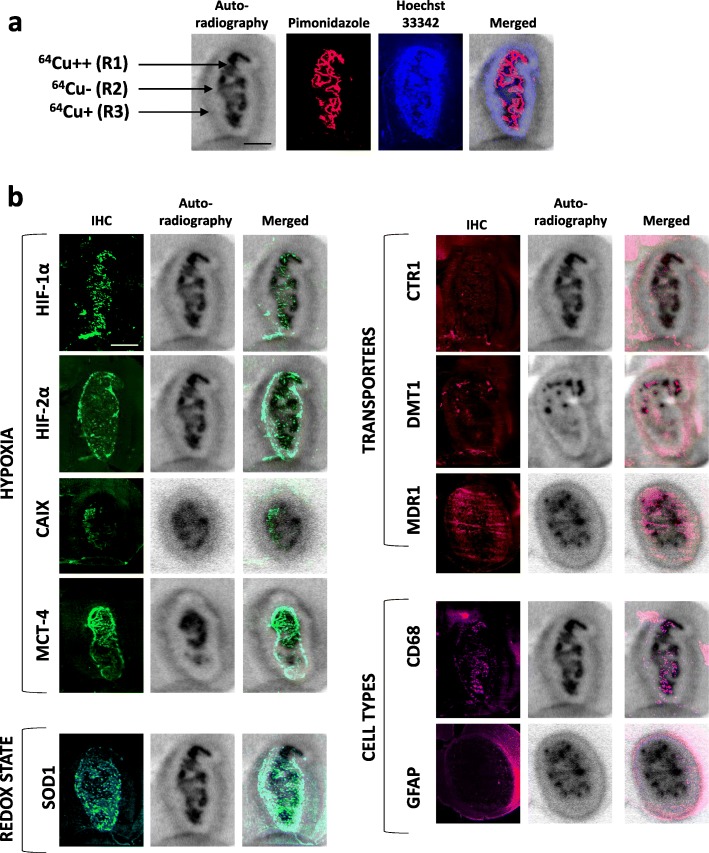

Fig. 4.

Relationships between the spatial heterogeneity of 64Cu uptake and hypoxia and expression of copper transporters. a Three areas with different intensities for 64Cu were distinguishable on the autoradiography: highly labeled area R1 (64Cu++), an unstaining intermediate region R2 (64Cu− and in the tumor periphery a moderate labeled region (64Cu+). Autoradiography was co-registered with pimonidazole staining to evaluate severe hypoxia and also Hoechst 33342 nucleic acid stain to identify the tumor mass. Scale bar = 200 μm. b Representative immunostaining of hypoxia markers (HIF-1α, HIF-2α, CAIX, MCT-4), specific or non-specific copper transporters (CTR1, DMT1, and MDR1), redox state (SOD1), and different cell types (CD68 for monocytes/macrophages and GFAP for reactive astrocytes). The autoradiography and immunohistochemistry studies were performed on same animals and consecutive sections. Scale bar = 200 μm

Data analysis

Image processing and analysis

Image analysis was performed with in-house macros based on the ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/, 1997-2012). PET analyses were performed with PMOD 3.1 software [27].

PET

To quantify 18F-FMISO, 64Cu-ATSM, and 64Cu-Cl2 uptake, the measured concentration of tissue activity (counts, kBq/mL) were divided by the injected activity in kBq/g of body weight to give a standardized uptake value (SUV, g/mL).

Tumor delineation

The regions of interest corresponding to the tumor and the contralateral mirror tissue were manually delineated on all contiguous T2w slices. The ROI corresponding to the tumor or to the contralateral tissue was used thereafter for measurements of all other parameters. These ROIs defined on MRI were used for comparison between radiotracers.

MRI/PET co-registration

All MRI experiments were performed such that all MRI maps were anatomically colocalized. A first automatic registration (PMOD 3.1) was performed between T2w MRI (reference) and the X-ray scan (input) using a rigid registration algorithm based on mutual information. The transformation matrix so obtained was then applied to all PET emission scans. Registration was visually assessed and, when necessary, manually refined.

Image segmentation

A ROI in the contralateral tissue was manually delineated to obtain a mean ± SD value. Then, a mean ± 3.3 SD threshold was used for segmentation to obtain a hypoxic volume for both 18F-FMISO and 64Cu-ATSM. These segmented ROIs were used for spatial analyses between both tracers.

In vitro studies

In vitro studies were carried out on C6 glioblastoma cells for which the culture conditions have been previously described. Once at confluence, the cells were seeded at a density of 200,000 cells/mL in T25 flask 48 h prior to exposure to radiotracers.

In vitro uptake in hypoxic conditions

To study the uptake of 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-Cl2 by hypoxic cells, various oxygenation protocols were studied which were intended to modify various parameters: the degree of oxygenation (21%, 5%, 1%, 0.5%, and 0.2% O2), hypoxia preconditioning time (3 h and 24 h), and radiopharmaceutical exposure time (1 h and 4 h).

During exposures to 64Cu-ATSM or 64Cu-Cl2 that lasted 1 h or 4 h, the cells were cultured in the same oxygenation condition used before treatment. A dose of 0.148 MBq (4 μCi) was provided in a volume of 2 mL of medium for each culture dish, both for of 64Cu-ATSM (457 μCi/nmol) and 64Cu-Cl2 (453 μCi/nmol). For each experimental condition, three independent cell cultures were analyzed.

64Cu retention was then assessed in various samples withdrawn from dishes: cell supernatant (2 mL), washing buffer with PBS (2 mL), and cell lysate (prepared from 200 μL of RIPA buffer).

Counting radioactivity

Radioactivity was counted in 1 mL of supernatant derived from cell cultures, in 100 μL of cell lysate, and in 1 mL of washing and on the pipetting cones, by a gamma counter (Wizard). All calculations were expressed as the percentage of radionuclide incorporated in the cells (relative to the dose delivered). To avoid effects probably due to different cell number in culture flasks, the cellular uptake was then normalized by the biomass and express as % cell retention/mg protein. Cells were lysed by mechanical dissociation (scraping) on ice in RIPA buffer. The supernatants were then removed to recover total cell proteins using a spectrophotometric colorimetric assay (OD measured at 562 nm; Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit from Thermo-Scientific, France).

RT-qPCR analysis

RNA was withdrawn using Nucleospin® RNA II Kit (Macherey-Nagel, France) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. One microgram of total RNA from each sample was reverse-transcribed using the Promega RT system (Promega, France) (RT at 42 °C for 1 h). Forward (F) and reverse (R) primers were designed for each gene using Beacon Designer software (Bio-Rad, France) as detailed in Additional file 2: Table S2. Assays were run in duplicate on the iCycler iQ™ realtime PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, France). The amplification profile was as follows: Hot Goldstar enzyme activation, 95 °C for 3 min; PCR 50 cycles at 95 °C, 15 s, and 60 °C, 1 min. The PCR was done according to the manufacturer’s protocol using the PCR™ Core Kit Sybr™ Green I (Eurogentec, France). The results were analyzed using a comparative method between the fractional cycle number to reach a fixed threshold and the fractional cycle number of β-actin gene and expressed using the 2−ΔCt formula.

Western blot analysis

The remaining cell lysate used for in vitro uptake of radioactivity were then processed for western blot analyses. Cells exposed to decreasing percentage of oxygen were lysed with RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, France) supplemented with 1 μg/mL protease inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich, France) and 1 μg/mL phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich, France). Proteins (40 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Sweden). The protein expression of CAIX, CTR1, and DMT1 were evaluated by specific primary antibodies (Additional file 2: Table S1), and β-Actin expression was used to check the equal loading in proteins on the gel. Blots were exposed to peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies (Additional file 2: Table S1), and immunoreactive bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Thermo-Scientific, France). The band intensity was processed with ImageJ and was normalized to their corresponding actin signal. Western blot photographs are representative of three independent experiments.

Statistical analyses

All data are presented as mean ± SD, unless otherwise stated. Statistical analyses were performed with JMP® program (SAS Institute Inc., USA). The different tests used are detailed in each figure legend.

Results

In vivo uptake of Cu-ATSM and Cu-Cl2 in a GB model

In order to investigate the uptake of 64Cu-ATSM in GB and its specificity for hypoxia, C6 glioma cells were selected based on our previous studies showing that this preclinical model presents a pronounced hypoxic component [10, 28].

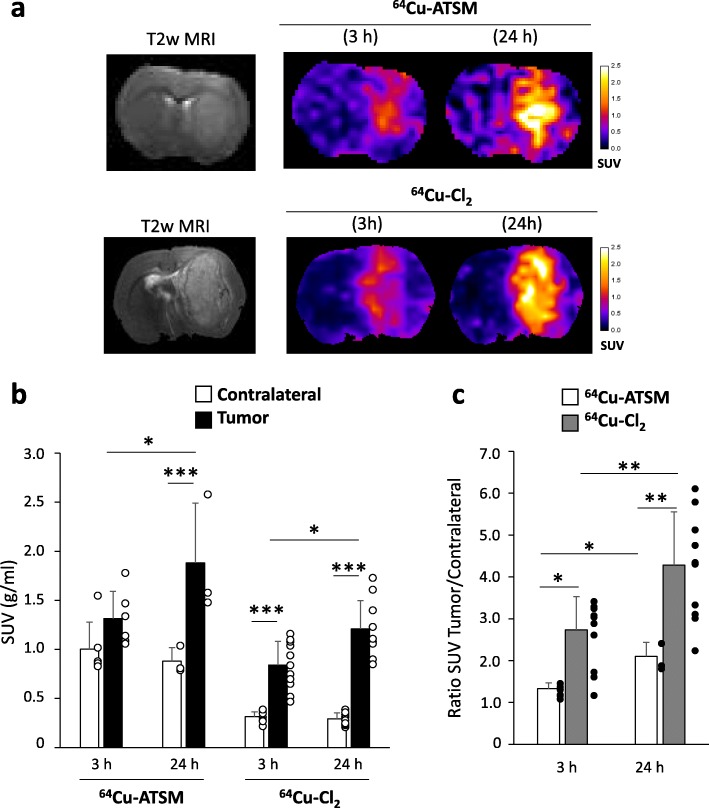

For both 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-Cl2, the initial uptake was detectable as early as 3 h following injection and, intriguingly, kept increasing until 24 h (Fig. 1a, b). Quantitatively, for 64Cu-ATSM, in the healthy brain, SUV was 1.00 ± 0.28 g/mL at 3 h and 0.88 ± 0.14 g/mL at 24 h post-injection. In the tumor, SUV was greater relative to the healthy brain reaching 1.31 ± 0.28 g/mL at 3 h (non-significant, p = 0.33 compared to contralateral) and 1.88 ± 0.61 g/mL at 24 h (p < 0.0001 relative to contralateral) (Fig. 1b). 64Cu-ATSM SUV quantified at 24 h in tumor was significantly higher compared to 3 h post-injection (p < 0.05) whereas contralateral SUV did not change over time (Fig. 1b). The increase in SUV over time is also displayed in the time activity curve (TAC) (Additional file 1: Figure S2A). Blood samples collected over a period of 2 h demonstrated a biphasic curve. After the initial peak observed 12 s after the injection and a very rapid decay to reach a minimum at 7 min 30 s, values tended to increase thereafter until the end of measurements (i.e., 2 h) (Additional file 1: Figure S2B). Interestingly, the scatterplot of blood activity and values in the tumor obtained during the first 2 h were correlated (R2 = 0.93) (Additional file 1: Figure S2B).

Fig. 1.

In vivo uptake of 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-Cl2 in C6 glioblastoma model. a MRI and PET images were acquired 15 days after tumor cell implantation into the striatum. 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-Cl2 uptake were evaluated at early (3 h) and late (24 h) times after radiotracer injection. Quantification of 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-Cl2 uptake from ipsilateral (tumor) and contralateral (healthy brain) SUVs (b) or ratio between tumor and contralateral SUVs (c) at the different imaging points. Mean ± SD, n = 6 rats for 64Cu-ATSM and n = 11 rats for 64Cu-Cl2. Tukey’s HSD test after significant two-ways ANOVA (group and time factors): *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001

Concerning 64Cu-Cl2, in the normal healthy brain, SUV was 0.31 ± 0.05 g/mL and 0.29 ± 0.06 g/mL at 3 h and 24 h respectively. These values were significantly lower than those observed for 64Cu-ASTM at 3 h and 24 h (Fig. 1b). In the tumor, 64Cu-Cl2 SUV was 0.84 ± 0.24 g/ml at 3 h (p < 0.001) and 1.21 ± 0.29 g/mL at 24 h (p < 0.001 relative to contralateral). As for 64Cu-ATSM, 64Cu-Cl2SUV significantly increased over time in the tumor (p < 0.05). The uptake in the tumor was significantly greater for 64Cu-ATSM than for 64Cu-Cl2 at 3 h and 24 h (Fig. 1b). Of note, as a result of the low uptake observed in the healthy tissue, the tumor/contralateral ratio was greater for 64Cu-Cl2 than 64Cu-ATSM at both 3 h (p < 0.05) and 24 h (p < 0.01) (Fig. 1c).

Retention of Cu-ATSM and Cu-Cl2 and hypoxia

In vitro results

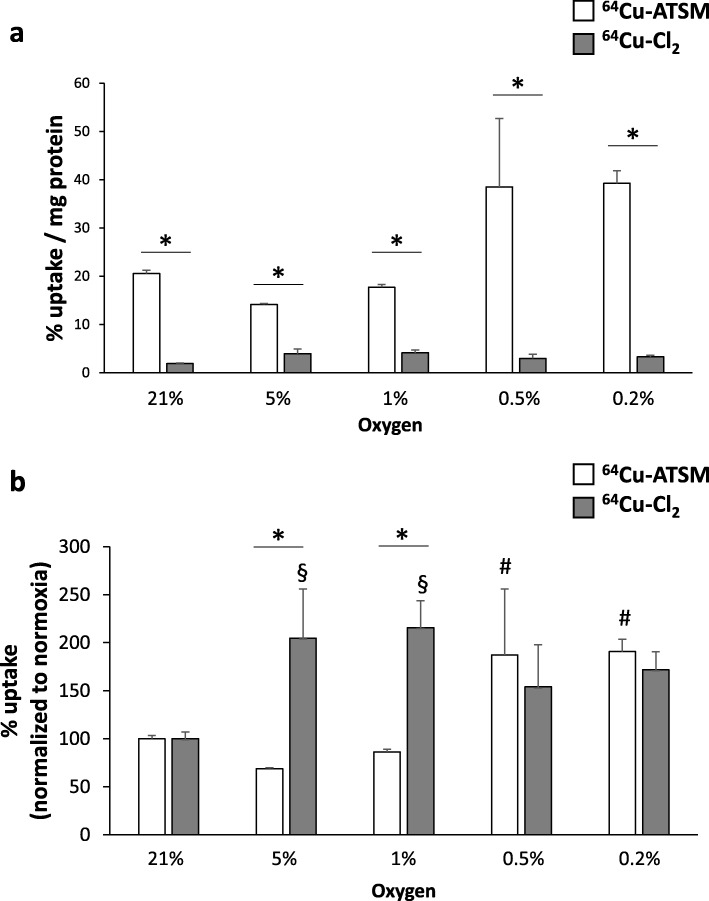

The relationship between 64Cu-ASTM and 64Cu-Cl2 uptake and hypoxia was analyzed in vitro at various oxygen levels (from 0.1 to 21% of oxygen). As expected, the uptake of 64Cu-ATSM was significantly greater than that of 64Cu-Cl2 both in normoxic and in hypoxic conditions (Fig. 2a). As instance, at 21% of oxygen, 64Cu-ATSM retention in C6 cells was 20.6 ± 0.7% uptake/mg protein whereas for 64Cu-Cl2, it was 1.9 ± 0.1% uptake/mg protein (p < 0.01). To better visualize the effect of hypoxia on cell retention, raw data were normalized relatively to the values obtained in normoxia for these two radiotracers (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, 64Cu-ATSM showed an increase in the uptake only in severe hypoxia at 0.5 and 0.2% of oxygen (187 ± 69% and 191 ± 13% respectively, compared to normoxia, p < 0.05) (Fig. 2b). Concerning 64Cu-Cl2, the cell retention was significantly increased at 5% and 1% of oxygen with no significant rise at lower oxygen percentages (Fig. 2b). Otherwise, the cellular uptake was not dependent on the incubation time (1 h or 4 h) for both radiotracers as mentioned in Additional file 1: Figures S3A and S3B. The hypoxia preconditioning time (3 h or 24 h before treatment with the radiotracers) had no effect (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

In vitro uptake of 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-Cl2 in tumor cells as a function of the degree of oxygenation. Quantification of cell retention of 64Cu-ATSM or 64Cu-Cl2 in normoxic (21% O2), moderate hypoxia (5% and 21% O2), or severe hypoxia (0.5% and 0.2% O2) for raw values (a) or normalized values relative to normoxic condition (b). Mean ± SD, n = 3 different cell cultures per condition. Tukey’s HSD test after significant two-ways ANOVA (group and time factors) was used. For comparison between 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-Cl2 for each oxygen condition, statistical significance was *p < 0.05. Statistical significances relative to normoxia were § < 0.05 for 64Cu-ATSM and #p < 0.05 for 64Cu-Cl2

In vivo results

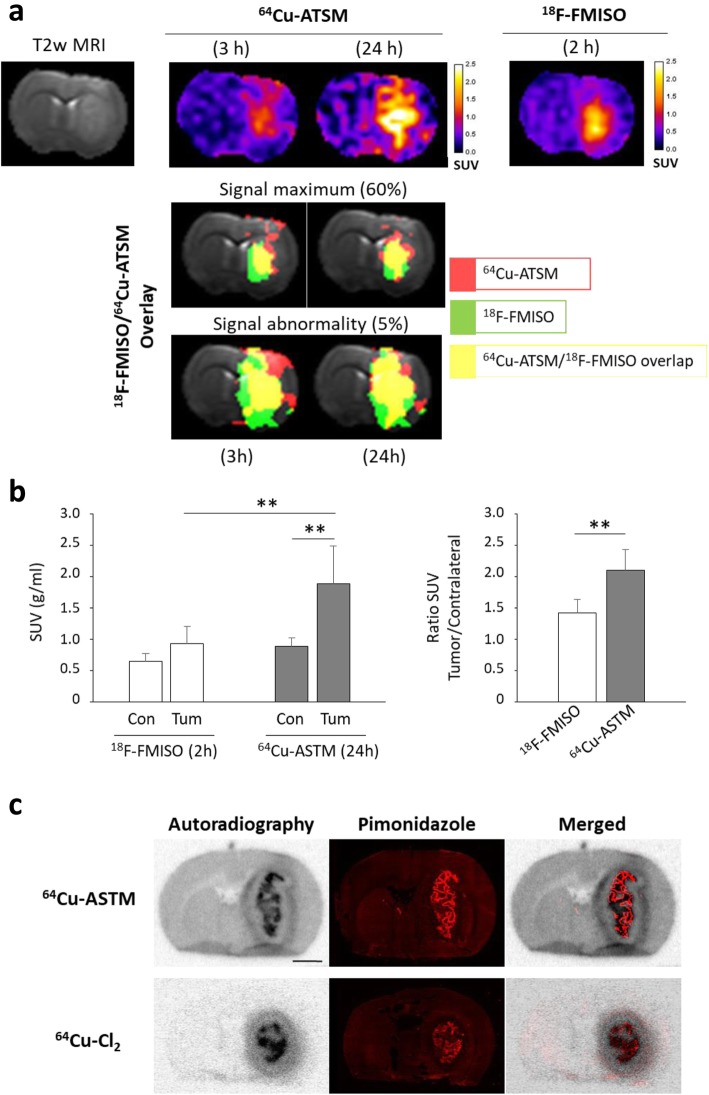

64Cu-ATSM uptake was compared in the C6 GB model to 18F-FMISO. PET images obtained 2 h after 18F-FMISO injection were compared to 64Cu-ATSM signals acquired at an early (3 h) or a late (24 h) post-injection time and were overlaid on the T2w IRM images used to delimit tumor masses (Fig. 3a). Interestingly, a large spatial overlap was observed between 18F-FMISO and 64Cu-ATSM by comparing 60% maximum signal or 5% signal abnormality. At this late time point, an elevated uptake of the tracer was observed with SUV values larger than those of 18F-FMISO (18F-FMISO SUV = 0.93 ± 0.28 g/mL and 64Cu-ATSM SUV = 1.88 ± 0.61 g/mL, p < 0.05). As showed on Fig. 3b, a similar uptake of 18F-FMISO and 64Cu-ATSM in healthy brain was observed (SUV = 0.64 ± 0.12 g/ml and 0.88 ± 0.14 g/ml, respectively). In the tumor, SUV for 18F-FMISO was slightly increased relative to the healthy brain reaching 0.93 ± 0.28 g/ml (non-significant, p = 0.17) whereas SUV for 64Cu-ATSM was significantly higher than the contralateral brain (SUV tumor = 1.88 ± 0.61 g/ml compared to healthy tissue, p < 0.01). Ultimately, 64Cu-ATSM uptake was greater than 18F-FMISO in tumor (p < 0.01) as evidenced by the quantification of ratio tumor/contralateral: ratio T/C = 1.42 ± 0.22 and 2.10 ± 0.33 for 18F-FMISO and 64Cu-ATSM, respectively (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Relationships between retention of 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-Cl2 and hypoxia. a Co-registration of 18F-FMISO PET signal (2 h post-injection) with 64Cu-ATSM PET signal (3 h or 24 h post-injection). The overlaid images corresponds to 60% signal maximum or 5% signal abnormality for 64Cu-ATSM (red), 18F-FMISO (green), or 64Cu-ATSM/18F-FMISO merged (yellow). b 18F-FMISO and 64Cu-ATSM uptake were evaluated at 2 h and 24 h after radiotracer injection, respectively. Quantification of 64Cu-ATSM and 18F-FMISO uptake from ipsilateral (tumor) and contralateral (healthy brain) SUVs (left part) or ratio between tumor and contralateral SUVs (right part) at the different imaging points. Mean ± SD, n = 5 rats for 18F-FMISO and n = 3 rats for 64Cu-ATSM. Tukey’s HSD test after significant two-ways ANOVA (radiotracer and ROI factors): **p < 0.01. c From same coronal rat brain sections performed 24 h after 64Cu-ATSM or 64Cu-Cl2 injection, autoradiography and pimonidazole immunostaining were done to evaluate overlapping of these two labeling. Scale bar = 250 μm

As presented in Fig. 3c, autoradiography confirmed a 64Cu-ATSM hypoxia-dependent tumor uptake as shown by spatial overlapping between autoradiography and pimonidazole staining. A similar result was observed for 64Cu-Cl2. The large difference in activity uptake in healthy brain between 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-Cl2 already observed in PET images was confirmed by autoradiography (Fig. 3c) and may be explained by the more lipophilic nature of 64Cu-ATSM compared to 64Cu-Cl2.

Interestingly, when looking at 64Cu-ATSM or 64Cu-Cl2 autoradiograms 24 h after the radiotracer injection, a spatial heterogeneity was observed and three distinct regions could be delimitated: (i) a central, highly labeled area corresponding to the dense tumor core and hypoxic tumor as observed on the Hoechst 33342 and pimonidazole staining (thereafter termed R1, 64Cu++); (ii) an intermediate region with no 64Cu labeling corresponding to a zone with high tumor cell density as seen on the Hoechst 33342 staining but without severe hypoxia as attested by pimonidazole staining (termed R2, 64Cu−); and (iii) a moderately labeled region at the periphery of the tumor which is not hypoxic, termed thereafter R3, 64Cu+ (Fig. 4a). To summarize, three areas could be delimitated by autoradiography: R1 (64Cu++/PIMO ++/Hoechst ++), R2 (64Cu−/PIMO−/Hoechst++), and R3 (64Cu+/PIMO−/Hoechst+). A similar regionalization of signal intensity for 64Cu was observed in the 3-h autoradiography (Additional file 1: Figure S4).

The 64Cu positive or negative regions were further characterized by immunohistochemistry in relation to the expression of several hypoxia and/or copper-related proteins in both 64Cu-ATSM or 64Cu-Cl2 injected animals (Fig. 4b). First, we compared the 64Cu uptake to hypoxic markers, namely HIF-1α, HIF-2α, CAIX, and MCT-4, by immunostaining (Fig. 4b). As shown in Fig. 4b, R1 (64Cu++) nicely superimposed to HIF-1α, CAIX, and MCT-4 staining. HIF-2α staining was observed in R1 (64Cu++) and mainly in R2 (64Cu−). Then, copper transporters were tested: the specific membrane transporter CTR1 (copper transporter 1) and the non-specific membrane transporters such as DMT1 (divalent metal transporter) and MDR1 (multidrug resistance protein 1). DMT1 was strongly expressed in R1 (64Cu++) and R3 (64Cu+) (Fig. 4b). CTR-1 was expressed mainly in R3 (64Cu+) while MDR1 was expressed in R1 (64Cu++) and R2 (64Cu−) (Fig. 4b). In parallel, SOD1 (superoxide dismutase 1 Cu-Zn) expression was studied because previous studies in other cancer types had suggested that redox state of tumor cells could be involved in 64Cu-ATSM uptake. In this study on GB, SOD1 was mainly present in area R2 (64Cu−) (Fig. 4b). Lastly, we analyzed some cellular reactions known to occur in parallel to tumor growth namely astrogliosis and inflammation and which might be related to 64Cu-ATSM or 64Cu-Cl2 uptake. CD68 and GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein) staining were used to assess inflammation and astrogliosis, respectively. The CD68 staining was higher in R1 (64Cu++) whereas GFAP staining was greater in R3 (64Cu+) (Fig. 4b).

For each region, the immunostaining was quantified according to two different parameters: the number of positive samples and the intensity score by attributing 1 point for low signal or 2 points for high signal (Additional file 2: Table S3). To have an overview of the different labeling, an overall score was measured by multiplying the number of positive samples and the intensity score (Fig. 5). Briefly, the overall score highlighted that the high intensity of 64Cu (R1) was strongly correlated to the uptake of pimonidazole and the expression of MCT-4 and DMT1; the moderate intensity of 64Cu (R3) corresponds to astrogliosis that also expressed CTR1 and DMT1.

Fig. 5.

Quantification of immunostaining for hypoxia, transporters, redox state, and cell types according to the spatial distribution of 64Cu uptake. For each region defined on the autoradiography (R1 (64Cu++), R2 (64Cu−), and R3 (64Cu+)), an overall score was measured by multiplying the number of positive samples and the intensity score for each immunolabeling (n = 9 rats)

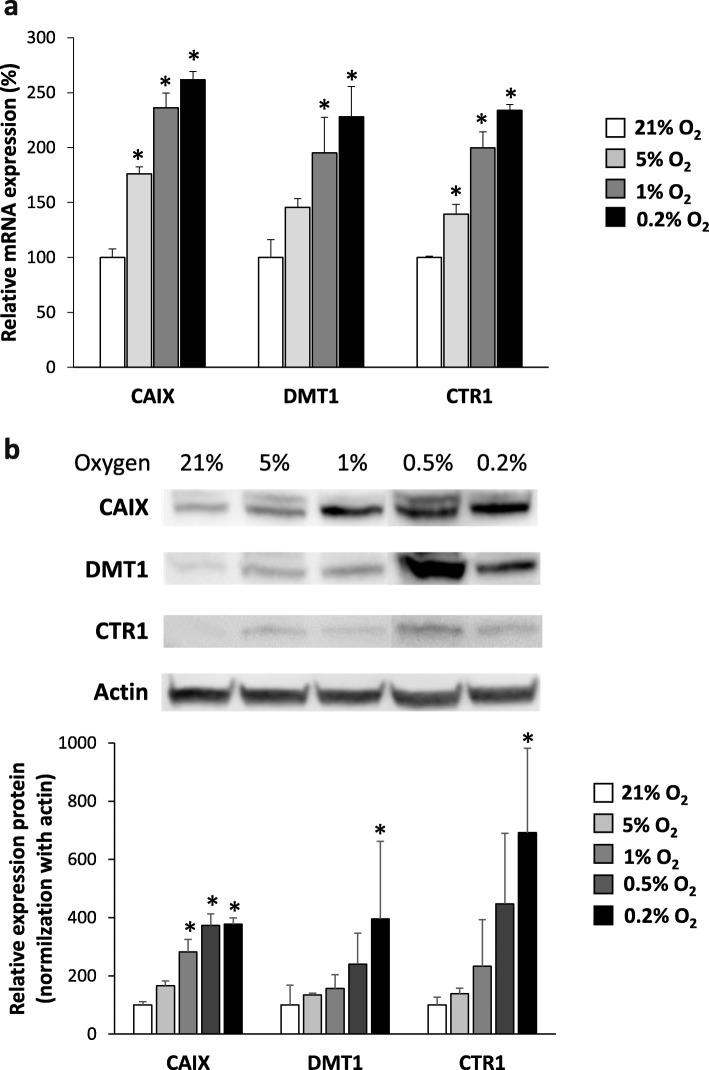

Expression of copper transporters (influx) as a function of hypoxia

To further address the dependency of copper transporters on hypoxia, we assessed the expression of both DMT1 and CTR1 at the mRNA (Fig. 6a) and protein levels (Fig. 6b). CAIX expression was used as a positive hypoxic control.

Fig. 6.

Expression of copper transporters, CTR1 and DMT1, in hypoxia. Quantification of expression of CTR1 and DMT1 at mRNA (a) or protein levels (b) from cells exposed for 24 h in hypoxic conditions (5%, 1%, 0.5%, and 0.2% O2) relative to normoxia (21% O2). CAIX expression was used as positive hypoxic control. Mean ± SD, n = 3 different cell cultures per condition. Tukey’s HSD test after significant one-way ANOVA: *p < 0.05

At the mRNA level, CAIX expression was significantly increased at 5% of oxygen and kept increasing at lower oxygen percentages (Fig. 6a). DMT1 was significantly overexpressed at 1% and 0.2% of O2 while CTR1 was overexpressed at 5% of oxygen and kept increasing at oxygen percentage. Similar trends were observed at the protein level for the three proteins studied (Fig. 6b). Interestingly, we demonstrated that copper transporter expression is strongly dependent of oxygen level (Additional file 1: Figure S5). The protein expression of DMT1 and CTR1 are almost return at the baseline as soon as 6 h of reoxygenation. The results sustain that if a reperfusion occurs in case of transient hypoxia in the tumor, copper transporter expression rapidly return to basal level.

Discussion

Cancer patients ought to benefit from hypoxia mapping to deal with hypoxia-induced radioresistance and chemoresistance. 64Cu-ATSM is a PET radiopharmaceutical that exhibits a low redox potential. It has been proposed as a selective marker of tissue hypoxia. In the present study, using a combination of both in vitro and in vivo experiments, we showed that 64Cu-ATSM accumulates in severe hypoxia (pimonidazole positive areas in vivo and less than 1% of oxygen in vitro). However, an uptake of 64Cu-ATSM was also observed at the outer periphery of the tumor where no evidence of hypoxia was detected (pimonidazole, HIF-1α, HIF-2α, CAIX, and MCT4 negative) but where specific cellular reactions such as the astrogliosis were observed. Interestingly, an increase in the expression of copper transporters was detected in this region. We also observed a marked uptake of 64Cu-Cl2 in tumors with a similar uptake regionalization. Interestingly, for both tracers, the uptake was more pronounced at 24 h than at 3 h post-injection. However, greater uptake values, measured in vivo and also in vitro, confirmed the interest of 64Cu-ATSM compared to 64Cu-Cl2. So, 64Cu-ATSM is actually a neutral lipophilic molecule with high cell membrane permeability that diffuses readily from the bloodstream to surrounding cells.

One of the first observations in this study was the uptake of both 64Cu-ATSM (and 64Cu-Cl2) in C6 glioma tumors. This uptake was detected in the tumor core, a region where nitroimidazole uptake was also detected. In previous studies, we already demonstrated a pronounced uptake of both 18F-FMISO and pimonidazole in this C6 glioma model [10, 28], and oxygen measurements with EPR probes confirmed that ptO2 was less than 10 mmHg of oxygen [29]. The present results highlight that 64Cu-ATSM (and 64Cu-Cl2) could be considered as selective tracers of hypoxia, which is in line with previous studies performed in the flank of rats that demonstrated correlations between 64Cu-ATSM and 18F-FMISO uptakes and between 64Cu-ATSM uptake and low pO2 [13, 14]. However, autoradiography also demonstrated that uptake occurred in regions where severe hypoxia was not evidenced (region R3). This observation raises some question about the specificity of 64Cu complexes as already discussed [30]. In our experiments, we observed similarities between 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-Cl2 uptake in the tumor hypoxic core (R1). These observations have already been described in head and neck cancer models and human colorectal models [31]. Similar behaviors have already been reported when comparing Cu-ATSM and Cu-Acetate [32]. As discussed, these data support the idea that the in vivo uptake may be the reflection of copper metabolism by the host organism and the tumor cells [22].

The expression of copper transporters may be increased by hypoxia and that may also explain the similar uptake of both 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-Cl2. In the ex vivo study, we confirmed that DMT1 is overexpressed in the pimonidazole positive region and that both DMT1 and CTR1 are also expressed in the outer ring of the tumor where pimonidazole staining is negative. These results support the idea that, while Cu-complexes could be retained in hypoxic cells following redox metabolism, they could also be detected in non-hypoxic cells expressing high amounts of transporters. Various situations may explain an increase in copper transporters. For instance, hypoxia is known to induce the expression of DMT1 through the activation of HIF-1α [33, 34] and the expression of CTR1 through HIF-2α [35]. In vitro, we also confirm that the expression of both influx transporters for copper is increased by hypoxia. Interestingly, we also observed a correlation between the uptake of Cu-complexes, CTR1 and DMT1 expression, and the astrogliosis at the outer periphery of the tumor. Astrocytes have already been described as a cornerstone in copper metabolism in the brain [36]. It is known that cultured astrocytes efficiently take up copper ions predominantly by the copper transporter CTR1 and the divalent metal transporter DMT1 [37]. In the study of Jorgensen and colleagues [38], the authors did not show correlation between the uptake of 64Cu and the expression of CTR1. However, when CTR1 was overexpressed in human breast cancer cells, it resulted in an increased uptake of 64Cu-Cl2 [39] while inhibition of CTR1 in prostate cancer cells resulted in a decreased uptake of 64Cu-Cl2 [40]. These data highlight the relationships that exist between copper transporters and imaging results. Interestingly, in the context of GB, hypoxia is well known as a poor prognosis factor. We analyzed the relationships between copper transporters and patient survival using the REMBRANDT database. We observed that CTR1 expression is also predictive of patient survival (Additional file 1: Figure S6A) but not DMT1 (Additional file 1: Figure S6B). No study has so far analyzed the dependency of DMT1 expression on Cu-complex uptake.

Another observation was the increase in 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-Cl2 uptake between 3 h and 24 h post-injection. This observation was in line with the arterial concentrations of 64Cu. While the initial exponential decay following the peak that occurred at about 7 min, an increase occurred thereafter and the blood activity kept increasing until the end of the measurements. One explanation lies on the fact that organs like liver could metabolize the 64Cu-ATSM complex and non-tracer-bound radioactive copper that may influence PET measurements could be transported into the blood stream, stored in hepatobiliary stores and released thereafter [38, 41] as either free 64Cu or protein-bound (albumin, ceruloplasmin… )[42, 43]. This metabolic pathway has been confirmed using D-penicillin which reduced liver uptake of Cu-ATSM [44]. Therefore, late PET imaging is influenced by the metabolic pathway.

Lastly, the development of novel therapeutic approaches to GB is essential and those based on radionuclide therapy could be of significant clinical impact. It was proposed in preclinical models that 64Cu-Cl2 [45] and also 64Cu-ATSM [46] could be pertinent theranostic agents for brain tumors. In this direction, the present study suggests a double interest in using 64Cu complexes internal radiotherapy for GB: target hypoxic areas (region R1 in the autoradiography) as well as the invasive areas localized at the periphery of tumors that are very rich in reactive astrocytes because of the invasion of tumor cells (region R3 on the autoradiography).

Considering hypoxia and based on our results, Cu-ATSM offers some benefits to FMISO. As an example, tumor to background ratio is greater owing to its lipophilicity. Cu-ATSM may enable to see hypoxia in brain tumors with intact BBB. Thanks to its elevated half-life, 64Cu offers widespread dissemination.

Our results show that the uptake is mediated through the overexpression of copper transporters induced by changes in oxygen tension.

Conclusions

As a conclusion, in the present study, we show that Cu complexes undoubtedly accumulate in hypoxic areas of the tumors. This uptake may be the reflection of a direct dependency to a redox metabolism and also a reflection of hypoxic-induced overexpression of transporters. We also show that Cu-ATSM also stained, to a lesser extent, non-hypoxic regions with high expression of copper transporters and in particular DMT-1 and CTR1 such as astrogliosis.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Schematic representation of the protocol used for in vivo experiments. Figure S2. Evaluation of 64Cu-ATSM activity in the brain and the plasma. (A) Time activity curve (TAC) measured for 24 hours after the radiotracer injection in the tumor, peritumoral area and healthy brain. (B) Superposition of TAC in the blood and in the tumor quantified during 2 hours after 64Cu-ATSM injection. Figure S3. In vitro uptake of 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-Cl2 in tumor cells according the time incubation with radiotracer. Quantification of cell retention of 64Cu-ATSM (A) and 64Cu-Cl2 (B) in normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic (0.5% and 0.2% O2) conditions after 1 hour or 4 hours of incubation of the tumor cells with the radiotracer brought into the culture medium. Mean ± SD, n = 3 different cell cultures per condition. Tukey’s HSD test after significant two-ways ANOVA (oxygen and time factors) was used: no significant difference was obtained. Figure S4. Spatial distribution of 64Cu-ATSM uptake in autoradiography at 3 hours or 24 hours after radiotracer injection. Figure S5. Protein expression of copper transporters, CTR1 and DMT1, in transient hypoxia. Cells were exposed to hypoxia (0.2% O2) during 24 hours and then reoxygenated (21%O2) during different times (6, 24 or 24 hours). Representative western-blot of DMT1 and CTR1 (A) and quantification of their protein expression (B). CAIX expression was used as positive hypoxic control. Mean ± SD, n = 3 different cell cultures per condition. Tukey’s HSD test after significant one-way ANOVA: * p < 0.05. Figure S6. Survival analyses of patients with glioblastoma according to the expression of copper transporters CTR1 and DMT1. Kaplan-Meier survival plot of glioblastoma patients were assessed according to the level of CTR1 or DMT1 gene expression from the REMBRANT database by using Betastasis online software (http://www.betastasis.com/, date of last access: 4.2.2012).

Additional file 2: Table S1. Details of primary and secondary antibodies used. IF=immunofluorescence, WB=western-blot. Table S2. Details of rat primers used for RT-qPCR analysis. Table S3. Quantification of immunostaining performed on brain slices with 64Cu-ATSM or 64Cu-Cl2 uptake in different areas R1, R2 and R3. Numbers in bold reflect immunolabeling greater than 75%.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Jacques Barbet and Dr Ferid Haddad for their critical evaluation of the paper.

Abbreviations

- 18F-FMISO

3-18F-fluoro-1-(2-nitro-1-imidazolyl)-2-propanol

- 64Cu-ATSM

Diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone)

- CAIX

Carbonic anhydrase IX

- CTR1

Copper transporter 1

- DMT-1

Divalent metal transporter 1

- HIFs

Hypoxia-inducible factors

- MDR1

Multidrug resistance protein 1

Authors’ contributions

EP, JT, LPP, DD, MC, MB, and SV designed the study, performed the experiments, and analyzed the results. MI, SG, and LB were involved in the synthesis of 18F-FMISO. AV and MB were involved in the synthesis and characterization of 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-CuCl2. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Région Normandie, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), the Université de Caen Normandie (UNICAEN), the European Union-Fonds Européen de Développement Régional (FEDER), the Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche and the French National Agency for Research “Investissements d’Avenir” no ANR-11-LABEX-0018-01, IGO Labex no ANR-11- LABX-0016-01, ArronaxPlus Equipex no ANR-11-EQPX-0004, SIRIC ILIAD (INCa-DGOS-Inserm_12558), i-Site NexT (ANR-16-IDEX-0007), and Fédération pour la recherche sur le cerveau (FRC).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The animal investigations were performed under the current European directive (2010/63/EU) in authorized laboratories (B14118001) and with the permission of the regional committee on animal ethics (CENOMEXA, APAFIS#1247).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Myriam Bernaudin and Samuel Valable contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13550-019-0586-6.

References

- 1.Chakhoyan A, Guillamo J-S, Collet S, Kauffmann F, Delcroix N, Lechapt-Zalcman E, et al. FMISO-PET-derived brain oxygen tension maps: application to glioblastoma and less aggressive gliomas. Sci Rep. 2017;7:10210. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08646-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans SM, Judy KD, Dunphy I, Jenkins WT, Nelson PT, Collins R, et al. Comparative measurements of hypoxia in human brain tumors using needle electrodes and EF5 binding. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1886–1892. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bekaert L, Valable S, Lechapt-Zalcman E, Ponte K, Collet S, Constans J-M, et al. [18F]-FMISO PET study of hypoxia in gliomas before surgery: correlation with molecular markers of hypoxia and angiogenesis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:1383–1392. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3677-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Q, Cao P. Clinical and prognostic significance of HIF-1α in glioma patients: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:22073–22083. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray LH, Conger AD, Ebert M, Hornsey S, Scott OC. The concentration of oxygen dissolved in tissues at the time of irradiation as a factor in radiotherapy. Br J Radiol. 1953;26:638–648. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-26-312-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haar CP, Hebbar P, Wallace GC, Das A, Vandergrift WA, Smith JA, et al. Drug resistance in glioblastoma: a mini review. Neurochem Res. 2012;37:1192–1200. doi: 10.1007/s11064-011-0701-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pérès EA, Gérault AN, Valable S, Roussel S, Toutain J, Divoux D, et al. Silencing erythropoietin receptor on glioma cells reinforces efficacy of temozolomide and X-rays through senescence and mitotic catastrophe. Oncotarget. 2015;6:2101–2119. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michiels C, Tellier C, Feron O. Cycling hypoxia: a key feature of the tumor microenvironment. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1866:76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corroyer-Dulmont A, Chakhoyan A, Collet S, Durand L, MacKenzie ET, Petit E, et al. Imaging modalities to assess oxygen status in glioblastoma. Front Med. 2015;2:57. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2015.00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valable S, Corroyer-Dulmont A, Chakhoyan A, Durand L, Toutain J, Divoux D, et al. Imaging of brain oxygenation with magnetic resonance imaging: a validation with positron emission tomography in the healthy and tumoural brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab Off J Int Soc Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016;37:2584–2597. doi: 10.1177/0271678X16671965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bourgeois M, Rajerison H, Guerard F, Mougin-Degraef M, Barbet J, Michel N, et al. Contribution of [64Cu]-ATSM PET in molecular imaging of tumour hypoxia compared to classical [18F]-MISO--a selected review. Nucl Med Rev Cent East Eur. 2011;14:90–95. doi: 10.5603/NMR.2011.00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujibayashi Y, Taniuchi H, Yonekura Y, Ohtani H, Konishi J, Yokoyama A. Copper-62-ATSM: a new hypoxia imaging agent with high membrane permeability and low redox potential. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 1997;38:1155–1160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dence CS, Ponde DE, Welch MJ, Lewis JS. Autoradiographic and small-animal PET comparisons between (18)F-FMISO, (18)F-FDG, (18)F-FLT and the hypoxic selective (64)Cu-ATSM in a rodent model of cancer. Nucl Med Biol. 2008;35:713–720. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis JS, Sharp TL, Laforest R, Fujibayashi Y, Welch MJ. Tumor uptake of copper-diacetyl-bis(N(4)-methylthiosemicarbazone): effect of changes in tissue oxygenation. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 2001;42:655–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tateishi K, Tateishi U, Nakanowatari S, Ohtake M, Minamimoto R, Suenaga J, et al. (62)Cu-diacetyl-bis (N(4)-methylthiosemicarbazone) PET in human gliomas: comparative study with [(18)F] fluorodeoxyglucose and L-methyl-[(11)C]methionine PET. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35:278–284. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toriihara A, Ohtake M, Tateishi K, Hino-Shishikura A, Yoneyama T, Kitazume Y, et al. Prognostic implications of 62Cu-diacetyl-bis (N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) PET/CT in patients with glioma. Ann Nucl Med. 2018;32:264–271. doi: 10.1007/s12149-018-1241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlin S, Zhang H, Reese M, Ramos NN, Chen Q, Ricketts S-A. A Comparison of the imaging characteristics and microregional distribution of 4 hypoxia PET tracers. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 2014;55:515–521. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.126615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCall KC, Humm JL, Bartlett R, Reese M, Carlin S. Copper-64-diacetyl-bis(N(4)-methylthiosemicarbazone) pharmacokinetics in FaDu xenograft tumors and correlation with microscopic markers of hypoxia. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:e393–e399. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan H, Schroeder T, Bowsher JE, Hedlund LW, Wong T, Dewhirst MW. Intertumoral differences in hypoxia selectivity of the PET imaging agent 64Cu(II)-diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 2006;47:989–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Obata A, Yoshimi E, Waki A, Lewis JS, Oyama N, Welch MJ, et al. Retention mechanism of hypoxia selective nuclear imaging/radiotherapeutic agent cu-diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) (Cu-ATSM) in tumor cells. Ann Nucl Med. 2001;15:499–504. doi: 10.1007/BF02988502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshii Y, Yoneda M, Ikawa M, Furukawa T, Kiyono Y, Mori T, et al. Radiolabeled Cu-ATSM as a novel indicator of overreduced intracellular state due to mitochondrial dysfunction: studies with mitochondrial DNA-less ρ0 cells and cybrids carrying MELAS mitochondrial DNA mutation. Nucl Med Biol. 2012;39:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dearling JLJ, Packard AB. On the destiny of (copper) species. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 2014;55:7–8. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.132480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holland Jason P., Barnard Peter J., Collison David, Dilworth Jonathan R., Edge Ruth, Green Jennifer C., McInnes Eric J. L. Spectroelectrochemical and Computational Studies on the Mechanism of Hypoxia Selectivity of Copper Radiopharmaceuticals. Chemistry - A European Journal. 2008;14(19):5890–5907. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burgman Paul, O'Donoghue Joseph A., Lewis Jason S., Welch Michael J., Humm John L., Ling C. Clifton. Cell line-dependent differences in uptake and retention of the hypoxia-selective nuclear imaging agent Cu-ATSM. Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 2005;32(6):623–630. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu J., Hajibeigi A., Ren G., Lin M., Siyambalapitiyage W., Liu Z., Simpson E., Parkey R. W., Sun X., Oz O. K. Retention of the Radiotracers 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-PTSM in Human and Murine Tumors Is Influenced by MDR1 Protein Expression. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2009;50(8):1332–1339. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.061879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corroyer-Dulmont Aurélien, Pérès Elodie A., Petit Edwige, Guillamo Jean-Sébastien, Varoqueaux Nathalie, Roussel Simon, Toutain Jérôme, Divoux Didier, MacKenzie Eric T., Delamare Jérôme, Ibazizène Méziane, Lecocq Myriam, Jacobs Andréas H., Barré Louisa, Bernaudin Myriam, Valable Samuel. Detection of glioblastoma response to temozolomide combined with bevacizumab based on µMRI and µPET imaging reveals [18F]-fluoro-l-thymidine as an early and robust predictive marker for treatment efficacy. Neuro-Oncology. 2012;15(1):41–56. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corroyer-Dulmont Aurélien, Pérès Elodie A., Gérault Aurélie N., Savina Ariel, Bouquet Fanny, Divoux Didier, Toutain Jérôme, Ibazizène Méziane, MacKenzie Eric T., Barré Louisa, Bernaudin Myriam, Petit Edwige, Valable Samuel. Multimodal imaging based on MRI and PET reveals [18F]FLT PET as a specific and early indicator of treatment efficacy in a preclinical model of recurrent glioblastoma. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2015;43(4):682–694. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3225-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valable S, Petit E, Roussel S, Marteau L, Toutain J, Divoux D, et al. Complementary information from magnetic resonance imaging and (18)F-fluoromisonidazole positron emission tomography in the assessment of the response to an antiangiogenic treatment in a rat brain tumor model. Nucl Med Biol. 2011;38:781–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Khan Nadeem, Li Hongbin, Hou Huagang, Lariviere Jean P., Gladstone David J., Demidenko Eugene, Swartz Harold M. Tissue pO2 of Orthotopic 9L and C6 Gliomas and Tumor-Specific Response to Radiotherapy and Hyperoxygenation. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2009;73(3):878–885. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colombié M, Gouard S, Frindel M, Vidal A, Chérel M, Kraeber-Bodéré F, et al. Focus on the controversial aspects of (64)Cu-ATSM in tumoral hypoxia mapping by PET imaging. Front Med. 2015;2:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Li F., Jorgensen J. T., Forman J., Hansen A. E., Kjaer A. 64Cu-ATSM Reflects pO2 Levels in Human Head and Neck Cancer Xenografts but Not in Colorectal Cancer Xenografts: Comparison with 64CuCl2. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2015;57(3):437–443. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.155663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hueting R, Kersemans V, Cornelissen B, Tredwell M, Hussien K, Christlieb M, et al. A comparison of the behavior of (64)Cu-acetate and (64)Cu-ATSM in vitro and in vivo. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 2014;55:128–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Legendre Claire, Garcion Emmanuel. Iron metabolism: a double-edged sword in the resistance of glioblastoma to therapies. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2015;26(6):322–331. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qian Zhong-Ming, Mei Wu Xiao, Fan Ming, Yang Lin, Du Fang, Yung Wing-Ho, Ke Ya. Divalent metal transporter 1 is a hypoxia-inducible gene. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2011;226(6):1596–1603. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pourvali K, Matak P, Latunde-Dada GO, Solomou S, Mastrogiannaki M, Peyssonnaux C, et al. Basal expression of copper transporter 1 in intestinal epithelial cells is regulated by hypoxia-inducible factor 2α. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:2423–2427. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scheiber IF, Dringen R. Astrocyte functions in the copper homeostasis of the brain. Neurochem Int. 2013;62:556–565. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dringen R, Scheiber I, Bulcke F. Copper metabolism of astrocytes. SpringerPlus. 2015;4:L3. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-4-S1-L3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jørgensen JT, Persson M, Madsen J, Kjær A. High tumor uptake of (64)Cu: implications for molecular imaging of tumor characteristics with copper-based PET tracers. Nucl Med Biol. 2013;40:345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim KI, Jang SJ, Park JH, Lee YJ, Lee TS, Woo KS, et al. Detection of increased 64Cu uptake by human copper transporter 1 gene overexpression using PET with 64CuCl2 in human breast cancer xenograft model. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 2014;55:1692–1698. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.141127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cai H, Wu J, Muzik O, Hsieh J-T, Lee RJ, Peng F. Reduced 64Cu uptake and tumor growth inhibition by knockdown of human copper transporter 1 in xenograft mouse model of prostate cancer. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 2014;55:622–628. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.126979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Hodgkinson V, Zhu S, Weisman GA, Petris MJ. Advances in the understanding of mammalian copper transporters. Adv Nutr Bethesda Md. 2011;2:129–137. doi: 10.3945/an.110.000273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laurie SH, Pratt DE. Copper-albumin: what is its functional role? Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;135:1064–1068. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(86)91036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Linder MC. Ceruloplasmin and other copper binding components of blood plasma and their functions: an update. Met Integr Biometal Sci. 2016;8:887–905. doi: 10.1039/C6MT00103C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshii Y, Matsumoto H, Yoshimoto M, Furukawa T, Morokoshi Y, Sogawa C, et al. Controlled administration of penicillamine reduces radiation exposure in critical organs during 64Cu-ATSM internal radiotherapy: a novel strategy for liver protection. PloS One. 2014;9:e86996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrari C, Asabella AN, Villano C, Giacobbi B, Coccetti D, Panichelli P, et al. Copper-64 dichloride as theranostic agent for glioblastoma multiforme: a preclinical study. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:129764. doi: 10.1155/2015/129764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoshii Y, Matsumoto H, Yoshimoto M, Zhang M-R, Oe Y, Kurihara H, et al. Multiple administrations of 64Cu-ATSM as a novel therapeutic option for glioblastoma: a translational study using mice with xenografts. Transl Oncol. 2018;11:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Schematic representation of the protocol used for in vivo experiments. Figure S2. Evaluation of 64Cu-ATSM activity in the brain and the plasma. (A) Time activity curve (TAC) measured for 24 hours after the radiotracer injection in the tumor, peritumoral area and healthy brain. (B) Superposition of TAC in the blood and in the tumor quantified during 2 hours after 64Cu-ATSM injection. Figure S3. In vitro uptake of 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-Cl2 in tumor cells according the time incubation with radiotracer. Quantification of cell retention of 64Cu-ATSM (A) and 64Cu-Cl2 (B) in normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic (0.5% and 0.2% O2) conditions after 1 hour or 4 hours of incubation of the tumor cells with the radiotracer brought into the culture medium. Mean ± SD, n = 3 different cell cultures per condition. Tukey’s HSD test after significant two-ways ANOVA (oxygen and time factors) was used: no significant difference was obtained. Figure S4. Spatial distribution of 64Cu-ATSM uptake in autoradiography at 3 hours or 24 hours after radiotracer injection. Figure S5. Protein expression of copper transporters, CTR1 and DMT1, in transient hypoxia. Cells were exposed to hypoxia (0.2% O2) during 24 hours and then reoxygenated (21%O2) during different times (6, 24 or 24 hours). Representative western-blot of DMT1 and CTR1 (A) and quantification of their protein expression (B). CAIX expression was used as positive hypoxic control. Mean ± SD, n = 3 different cell cultures per condition. Tukey’s HSD test after significant one-way ANOVA: * p < 0.05. Figure S6. Survival analyses of patients with glioblastoma according to the expression of copper transporters CTR1 and DMT1. Kaplan-Meier survival plot of glioblastoma patients were assessed according to the level of CTR1 or DMT1 gene expression from the REMBRANT database by using Betastasis online software (http://www.betastasis.com/, date of last access: 4.2.2012).

Additional file 2: Table S1. Details of primary and secondary antibodies used. IF=immunofluorescence, WB=western-blot. Table S2. Details of rat primers used for RT-qPCR analysis. Table S3. Quantification of immunostaining performed on brain slices with 64Cu-ATSM or 64Cu-Cl2 uptake in different areas R1, R2 and R3. Numbers in bold reflect immunolabeling greater than 75%.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.