Abstract

The Cre/lox system is a potent technology to control gene expression in mouse tissues. However, cardiac-specific Cre recombinase expression alone can lead to cardiac alterations when no loxP sites are present, which is not well understood. Many loxP-like sites have been identified in the mouse genome that might be Cre sensitive. One of them is located in the Dmd gene encoding dystrophin, a protein important for the function and stabilization of voltage-gated calcium (Cav1.2) and sodium (Nav1.5) channels, respectively. Here, we investigate whether Cre affects dystrophin expression and function in hearts without loxP sites in the genome. In mice expressing Cre under the alpha-myosin heavy chain (MHC-Cre) or Troponin T (TNT-Cre) promoter, we investigated dystrophin expression, Nav1.5 expression, and Cav1.2 function. Compared to age-matched MHC-Cre− mice, dystrophin protein level was significantly decreased in hearts from MHC-Cre+ mice of more than 12-weeks-old. Quantitative RT-PCR revealed decreased mRNA levels of Dmd gene. Unexpectedly, calcium current (ICaL), but not Nav1.5 protein expression was altered in those mice. Surprisingly, in hearts from 12-week-old and older TNT-Cre+ mice, neither ICaL nor dystrophin and Nav1.5 protein content were altered compared to TNT-Cre−. Cre recombinase unpredictably affects cardiac phenotype, and Cre-expressing mouse models should be carefully investigated before experimental use.

Subject terms: Cell biology, Molecular biology

Introduction

Over the past decades, different genome manipulation technologies have been developed to investigate the function of specific genes in vivo. The Cre/loxP system has been of particular interest since it offers the possibility to generate tissue-specific and time-dependent knock-in (KI) or knock-out (KO) mice1,2. To generate cardiomyocyte-specific KO mice, Cre recombinase is often placed under the α-myosin-heavy chain (MHC) and the Troponin T (TNT) promoters. To date, many murine MHC- and TNT-Cre strains have been generated on different genetic backgrounds. Constitutive Cre expression under the control of MHC promoter can however decrease the cardiac ejection fraction in an age-dependent manner3. One potential mechanism to explain the side effects of Cre expression is the presence of loxP-like sites in the wild-type genome that are sensitive to Cre activity3,4. One of these loxP-like site is localized in the Dmd gene that encodes the structural protein dystrophin3. This 427-kilodalton protein is crucial to maintain the integrity of the lateral membrane of cardiac myocytes5. The absence of dystrophin in dystrophinopathies such as Duchene muscular dystrophy alters the current mediated by the voltage-gated calcium channel Cav1.2 (ICaL) and the whole-cell protein content of voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.56–9. Based on these observations and knowing that Cav1.2 and Nav1.5 are pivotal players in cardiac function, we compared dystrophin protein expression, ICaL, and whole-cell Nav1.5 protein expression in hearts between MHC-Cre−, MHC-Cre+, TNT-Cre−, and TNT-Cre+ mice.

Results

Dystrophin expression is reduced in an age-dependent manner in MHC-Cre+ mouse hearts

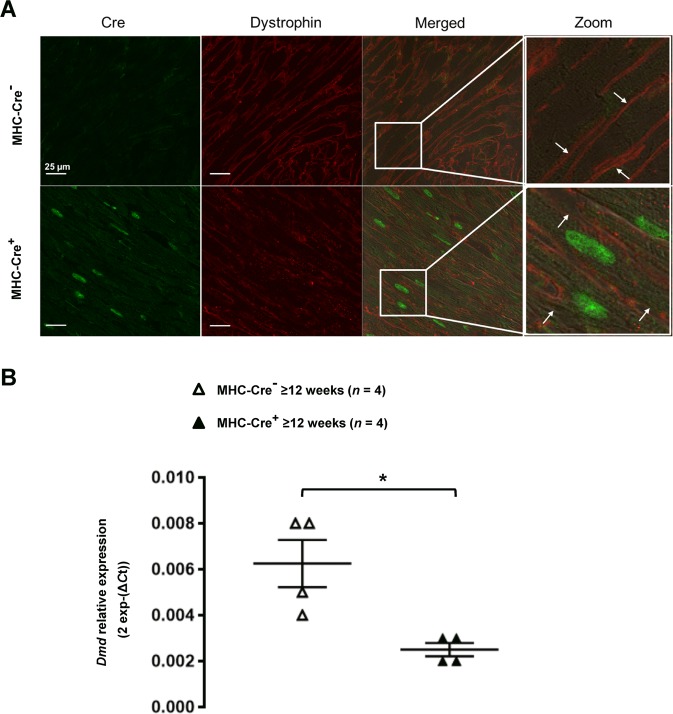

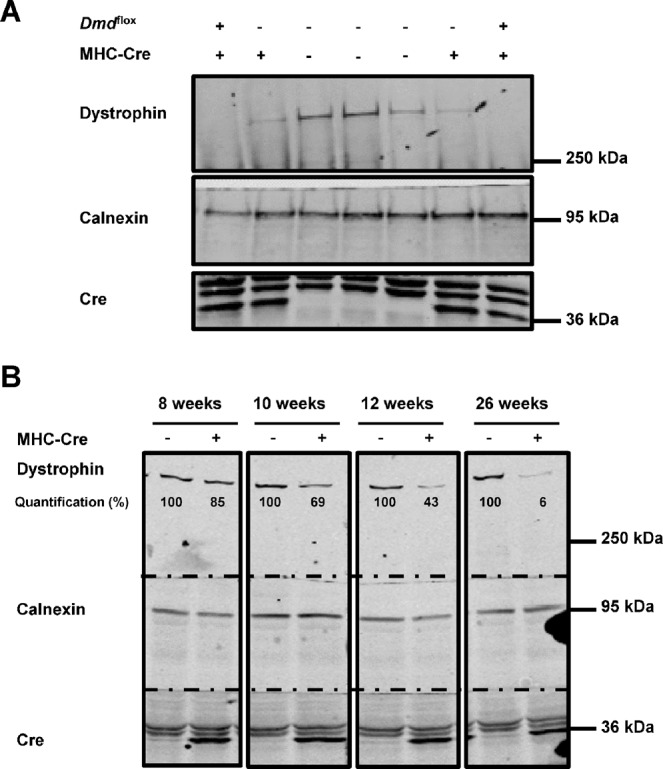

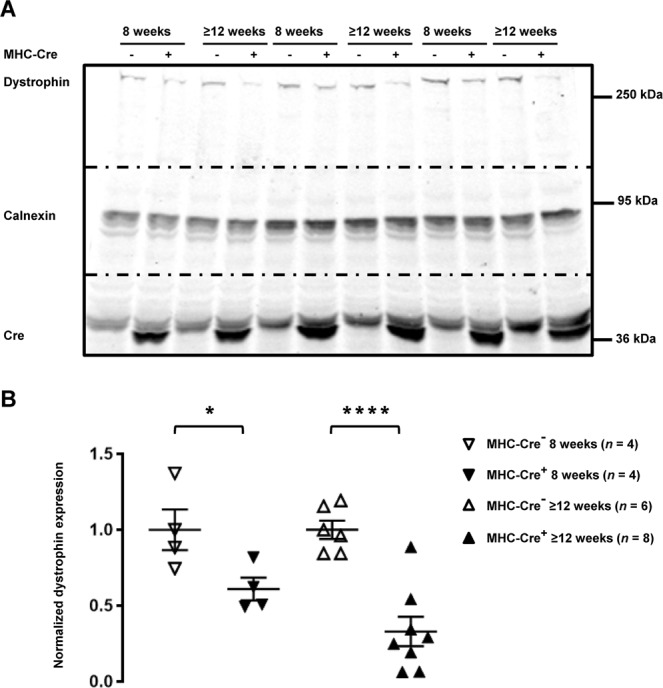

Dmdflox+ mice were generated (Suppl. Fig. 1) and used as a control for the Cre recombinase activity under the control of MHC promoter. Western blots were performed using heart lysates from 12-weeks-old wild-type (WT; Dmdflox−/MHC-Cre−), MHC-Cre+ (Dmdflox−/MHC-Cre+), and dystrophin KO (Dmdflox+/MHC-Cre+) littermate mice. Dystrophin expression was efficiently suppressed in dystrophin KO compared to WT hearts (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, dystrophin expression was also greatly reduced in the non-floxed MHC-Cre+ littermates (Fig. 1A, compare lane 2 and 6 with lane 3–5). In contrast, the presence of the floxed element did not affect the dystrophin expression in heart lysates (Suppl. Fig. 2). To address the time course of dystrophin decrease due to the expression of Cre only, western blots were performed on hearts from 8-, 10-, 12-, and 26-week-old mice. The reduction in dystrophin expression seemed to be more pronounced with age (Fig. 1B). To statistically confirm the age-dependent loss of dystrophin expression, western blots were performed on hearts from 8-, 12-, and ≥12-week-old MHC-Cre+ mice and control littermates (MHC-Cre−). While dystrophin expression differed only slightly between control and MHC-Cre+ hearts at 8 weeks, at ≥12 weeks dystrophin expression was significantly decreased by 70 ± 10% in MHC-Cre+ hearts compared to controls (MHC-Cre−) (Fig. 2A,B). Immunostainings on cardiac sections from ≥12-week-old MHC-Cre+ mouse hearts showed reduced dystrophin expression at the lateral membrane compared to their littermate controls (MHC-Cre−) (Fig. 3A).

Figure 1.

Dystrophin expression is decreased in adult mouse hearts expressing Cre. (A) Cropped western blots showing dystrophin expression in the hearts of WT (Dmdflox−, MHC-Cre−), MHC-Cre+ (Dmdflox−, MHC-Cre+), and cardiac-specific dystrophin-KO (Dmdflox+, MHC-Cre+) mice. (B) Cropped western blots showing dystrophin expression in mouse hearts at different ages with or without Cre recombinase expression. Dystrophin expression is quantified by normalizing band intensity to calnexin band intensity.

Figure 2.

Dystrophin expression is decreased in MHC-Cre+ mouse hearts in an age-dependent manner. (A) Cropped western blots showing dystrophin expression in MHC-Cre− and MHC-Cre+ mouse hearts from 8-week-old and more than 12-week-old (≥12 weeks) mice. (B) Quantification of dystrophin expression from 4 to 8 western blots. *p < 0.05 and ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 3.

Dystrophin expression is altered in adult MHC-Cre+ mouse hearts at protein and mRNA level. (A) Representative immunostainings of three independent experiments showing decreased dystrophin signal (red) at the lateral membrane (white arrows), in cardiomyocytes expressing Cre (green). (B) Decreased mRNA levels for dystrophin are also observed in adult MHC-Cre+ mouse hearts compared with control littermates (MHC-Cre−). *p < 0.05.

Dmd mRNA expression is reduced in MHC-Cre+ hearts

The reduced expression of dystrophin, leaded us to perform quantitative RT-PCR on mRNAs extracted from ≥12-week-old mouse hearts. The relative decrease of 2exp−(ΔCT) measured with MHC-Cre+ hearts corresponded to a ~50% reduction in Dmd mRNA level in MHC-Cre+ compared to the control mice (MHC-Cre−) (Fig. 3B). This indicates that the Cre-mediated decrease of dystrophin protein correlates with a decrease of Dmd mRNA expression.

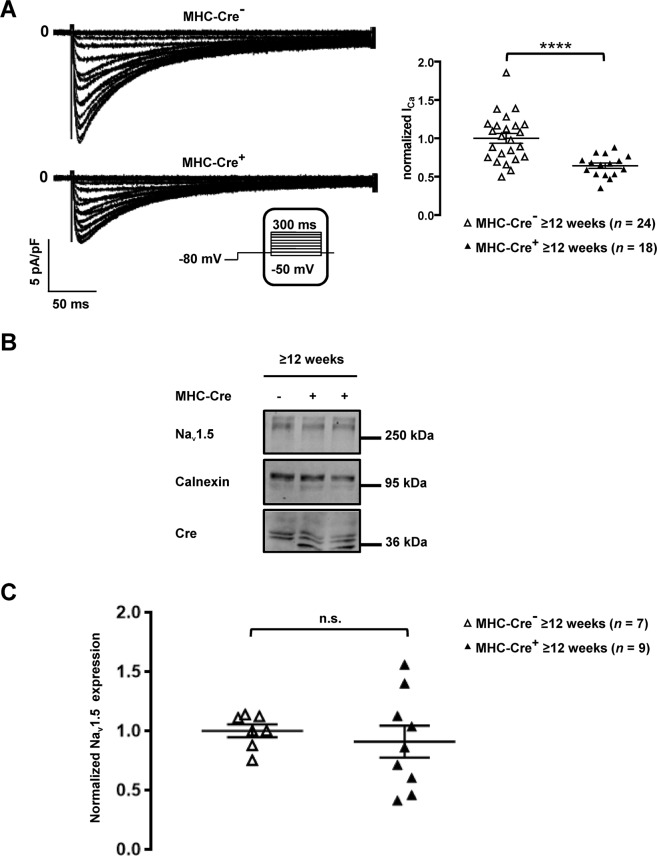

Calcium current ICaL but not Nav1.5 expression is altered in MHC-Cre+ cardiomyocytes

Considering the role of dystrophin in the regulation of Cav1.2 currents, we recorded calcium currents in MHC-Cre+ isolated cardiomyocytes9. Calcium current densities recorded in isolated cardiomyocytes were decreased in cardiomyocytes from ≥12-week-old MHC-Cre+ mice compared to controls (MHC-Cre−) in contrary to what it has been previously reported9 or observed in the dystrophin deficient mice used in this study (Fig. 4A and Suppl. Fig. 3). Since dystrophin regulates sodium channel stability in cardiac myocytes6,8, we also studied Nav1.5 expression in whole-heart lysates from ≥12-week-old mice. Surprisingly, Nav1.5 expression did not differ between MHC-Cre+ and MHC-Cre− hearts (Fig. 4B,C).

Figure 4.

Decreased ICaL and unaltered Nav1.5 expression in MHC-Cre+ mouse cardiomyocytes and mouse hearts respectively. (A) Representative traces of ICaL recorded in isolated cardiomyocytes (left panel) and quantification of ICaL (right panel) shown a significant downregulation of the calcium current in MHC-Cre+ cardiomyocytes compared to the control (MHC-Cre−) from ≥12-week-old mice. ****p < 0.0001. (B) Cropped western blots showing Nav1.5 expression in heart lysates from MHC-Cre+ and MHC-Cre− ≥12-week-old mice. The bottom panel shows the quantification of Nav1.5 expression normalized to calnexin expression from 7 to 9 western blots. n.s. indicates a non-statistically significant difference.

No alterations observed in TNT-Cre+ mouse line

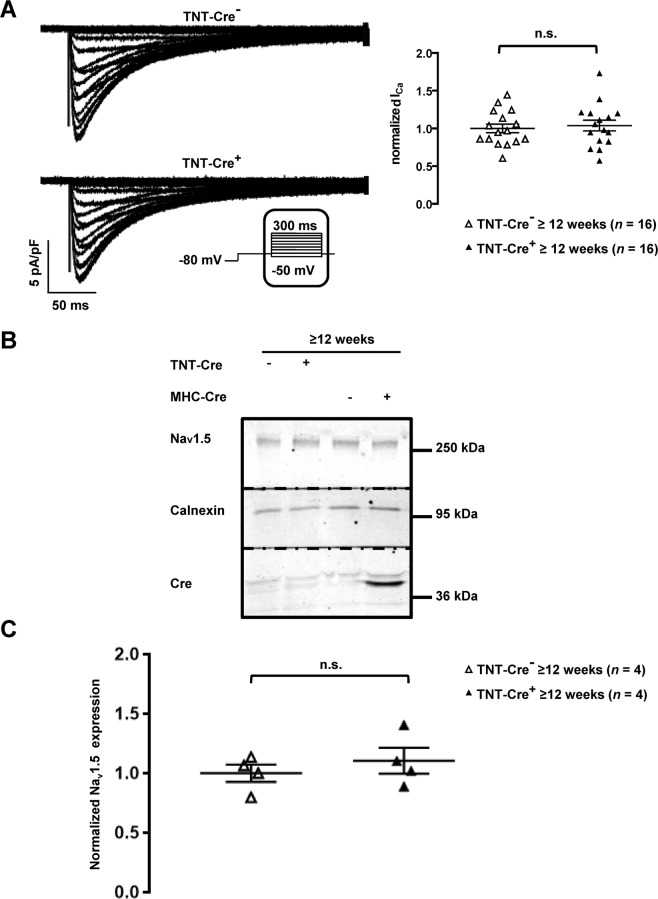

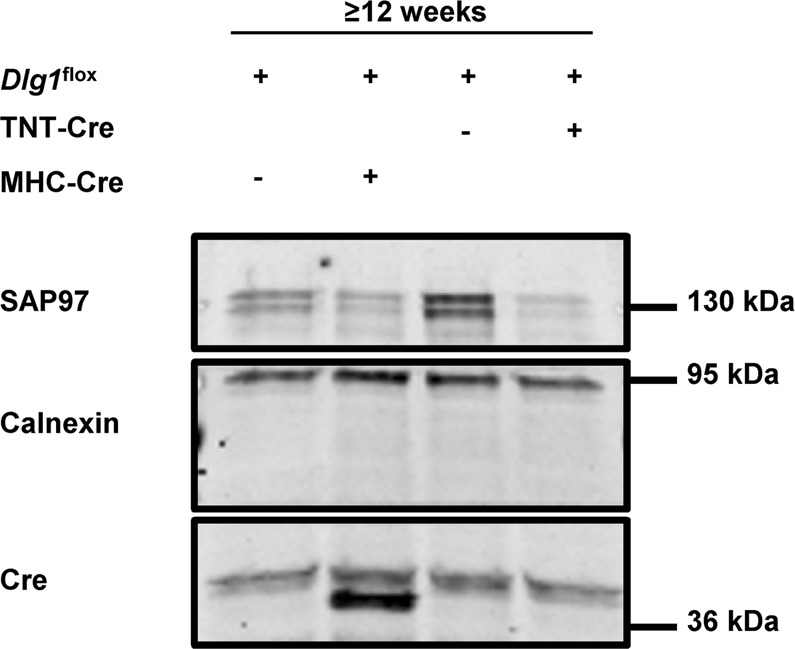

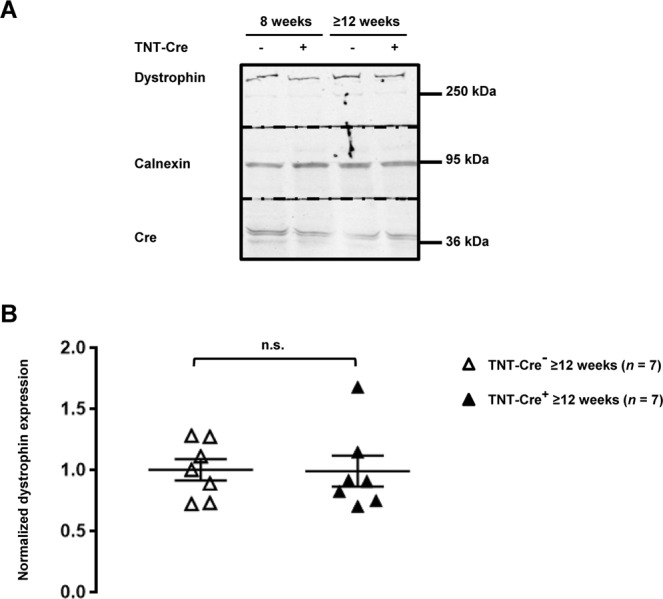

Based on our observations in MHC-Cre+ mouse line, we conducted similar experiments on TNT-Cre+ mice, in which Cre recombinase is under the control of the rat troponin T2 cardiac promoter10. This strain has been useful for generating early cardiomyocyte-specific mutants since Cre is mainly expressed during embryogenesis10. As expected, we observed Cre expression only in new-born TNT-Cre+ mouse hearts (Suppl. Fig. 3A,B)10. To validate the recombinase activity of the Cre enzyme under the control of the TNT promoter, we crossed TNT-Cre+ mice with mice previously characterized Dlg1flox mice in which the SAP97-coding gene Dlg1 was floxed, and compared them to MHC-Cre+ Dlg1flox mice11. SAP97 downregulation was similarly effective in MHC-Cre+ and TNT-Cre+ hearts from ≥12-week-old mice (Fig. 5). No decrease in dystrophin protein expression was observed in TNT-Cre+ hearts from ≥12-week-old mice compared to control littermates (TNT-Cre−) (Fig. 6A,B). Moreover, neither calcium currents (Fig. 7A) nor Nav1.5 expression (Fig. 7B,C) were altered in cardiomyocytes and heart lysates from ≥12-week-old and more TNT-Cre+ mice compared with their respective controls.

Figure 5.

Characterization of adult TNT-Cre+ mouse hearts. (A) Cropped western blots showing the decrease of expression of SAP97 in transgenic mouse hearts in which SAP97 alleles (Dlg1) are floxed (Dlg1flox) and breed either with TNT-Cre+ or MHC-Cre+ mice.

Figure 6.

Dystrophin protein expression is not altered in TNT-Cre+ mouse hearts. (A) Cropped western blots showing dystrophin expression in TNT-Cre− and TNT-Cre+ from 8-week-old and 12 or more-week-old (≥12 weeks) mouse heart lysates. (B) Quantification of cardiac dystrophin expression from ≥12-week-old mice from 7 western blots. n.s. indicates a non-statistically significant difference.

Figure 7.

ICaL and Nav1.5 expression are unaltered in TNT-Cre+ mouse cardiomyocytes and mouse hearts. (A) Representative traces of ICaL recorded in isolated cardiomyocytes (left panel) and quantification of ICaL (right panel) show that the calcium current is not changed in TNT-Cre+ cardiomyocytes compared to the control (TNT-Cre−) from ≥12-week-old mice. n.s. indicates a non-statistically significant difference. (B) Cropped western blots showing Nav1.5 expression in heart lysates from ≥12-week-old MHC-Cre+, MHC-Cre−, TNT-Cre−, and TNT-Cre+ mice. (C) Nav1.5 expression quantification of 4 western blots normalized to calnexin band intensity. n.s. indicates a non-statistically significant difference.

Discussion

MHC-Cre mice have been extensively used to alter the expression of various cardiac genes12–14. Our present work however strongly suggests that the MHC-Cre model should be carefully characterized before using it for any experiment, mainly because Cre expression reduces dystrophin protein and mRNA expression. Dystrophin is a crucial protein in many cardiac processes, and dystrophin reduction has been observed in human diseased cardiomyocytes5. Secondly, the L-type calcium current density is decreased by about 40% in the MHC-Cre model. Calcium current is pivotal for cardiac excitation-contraction coupling, among other processes, and calcium current dysregulation has been implied in many cardiac arrhythmias15.

The observations that protein expression of the sodium channel Nav1.5 is not affected in MHC-Cre+ mice, although dystrophin-deficient mdx5cv mice show an overall reduction of Nav1.5 expression is unexpected6. These discrepancies may be explained by the fact that dystrophin expression is only reduced from 12 weeks of age in MHC-Cre+ mice whereas dystrophin is constitutively absent in mdx5cv mice.

In contrary to the dystrophin-deficient mdx mice showing an upregulation of the calcium current9, in MHC-Cre+ mice, the reduction of dystrophin expression correlates with a decrease of ICaL. In addition calcium current recordings using the dystrophin deficient mice presented in this study did not reproduced the aforementioned observations (upregulation of the calcium current9) (Suppl. Fig. 4). Although, overall all these data are puzzling, the consequences of the absence of dystrophin on the calcium current is still under debate. The gender, the age and probably the genetic background could explain such observations. For example although Rubi and colleagues have shown no alteration of calcium current in male aged dystrophin deficient mice (>25 weeks old)16, Li and co-workers reported an increase of this conductance in mixed-sex aged dystrophin deficient mice (>25 weeks old)17. In addition, the discrepancy of effects on calcium current in dystrophin deficient mice between our study and the one from Koenig9, using young adult mice (<25 weeks old), could be due to the genetic background of the mice used: C57BL/6J and C57BL/10ScSnJ respectively. Overall these data suggest again the importance of proper controls when working with animals.

These results presented in this study suggest also that the expression of other genes is probably altered in the MHC-Cre model leading to complex and unpredictable side effects.

Surprisingly, we observed that Cre expression under the rat troponin T2 cardiac promoter affected neither dystrophin expression nor the calcium current. Those differences of phenotype between MHC-Cre+ and TNT-Cre+ mice may be explain by two different hypothesis. The first one could be the difference of genetic background. Indeed, mice on mixed backgrounds seem to be more resistant to developing cardiac dysfunction in response to Cre expression than mice on a pure background18. The second hypothesis could be the “time window” of Cre activity. Cre recombinase under the TNT promoter is mainly expressed in new-born mice, whereas in MHC-Cre+ mice, Cre is constitutively expressed. It is tempting to hypothesize that the off-target effects of Cre mainly occur when Cre recombinase is constitutively expressed after the birth, however further investigations are required to challenge these hypotheses.

Interestingly, a recent study reported the presence of more than 600 loxP-like sites in the genome of C57Bl/6 mice one of which present in the gene coding for the dystrophin3. The decrease of mRNA coding for dystrophin observed in MHC-Cre+ mice could be due to the Cre recombinase activity on the dystrophin gene containing the loxP-like site. However further experiments should be performed to validate this hypothesis. Based on the amount of loxP-like sites, we may therefore speculate that other genes and proteins are dysregulated in MHC- and TNT-Cre models, which could have various unexpected effects including those observed in this study. Based on these observations, one hypothesis to explain the decrease of calcium current densities in MHC-Cre+ ventricular cardiomyocytes compared to the control may be due to an unspecific effect of the cre recombinase either on the gene coding for the voltage-gated calcium channel or on other genes coding for proteins involved in the regulation of the calcium current. A comprehensive proteomic analysis on MHC-Cre+ and TNT-Cre+ hearts would be required to address the effect of Cre expression on the non-floxed genome.

Cre expression alone likely induces a disease-like phenotype that may confound the effects of any Cre-mediated gene deletion. Indeed, Buerger et al. have observed dilated cardiomyopathy in MHC-Cre+ mice, further highlighting a potential deleterious effect of the Cre recombinase under the control of the MHC promoter14. Pugach et al. also reported that prolonged expression of Cre recombinase decreases cardiac function and leads to DNA damage, fibrosis, and cardiac inflammation in MHC-Cre+ mice3. Although the constitutive expression of Cre in the MHC-Cre model may underlie the aforementioned problems, alternative models all have sizeable shortcomings. Firstly, the MHC-MerCreMer mouse line allows inducible rather than constitutive cardiac-specific expression of Cre driven by the MHC promoter19. MerCreMer is a fusion protein containing Cre recombinase with two modified estrogen receptor ligand-binding domains at both ends. Treatment with oestrogen receptor modulators such as tamoxifen induce Cre expression. Stec et al. however reported that systolic function is impaired in a MHC-MerCreMer mouse strain20. Subsequently, two groups showed that tamoxifen-induced Cre expression is linked to cardiac fibrosis and DNA damage, leading to heart failure and death21,22.

Cre recombinase expression can also be regulated by a reverse tetracycline transactivator that is specifically expressed in the heart23. Cre is produced once the Cre expression repressor doxycycline is removed from food and water23. However, to our knowledge, the effect of this approach on cardiac function has not been investigated yet.

Recently, Werfel and colleagues established a promising approach for cardiac gene inactivation by transfer of the Cre recombinase gene using adeno-associated viral vectors serotype 9 (AAV9)24. This technology may induce cardiac-specific inactivation of the floxed gene without adverse side effects on cardiac function24. However, more research is required.

In view of these problems, Olson and colleagues have generated a cardiac-specific transgenic mouse using the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeat (CRISPR)-associated (Cas) 9 approach. Cardiac-specific overexpressing of Cas 9 did not have side effects25. Then, they delivered a single-guide RNA to the heart using AAV9. This elegant method may be a better alternative to the Cre/lox system25.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study serve as a warning to researchers who use engineered mouse lines. Our results strongly suggest that experimenters should carefully chose the proper controls when using Cre-expressing mouse models to avoid any misinterpretation.

Methods

Parts of these methods have already been published previously11,26,27.

Animals

All experiments involving animals were performed according to the Swiss Federal Animal Protection Law and have been approved by the Cantonal Veterinary Administration, Bern. This investigation conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH publication no. 85-23, revised 1996)11,27. All the experiments have been approved by the veterinary office of Bern, Switzerland. (TVB number: BE 28/19). Male mice from four different transgenic mouse lines were used in this study. Firstly, the B6.FVB-Tg(Myh6-cre) 2182Mds/J line, also known as MHC-Cre, in which the cardiac-specific α-myosin-heavy chain (Myh6) promoter drives expression of Cre, was purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (stock no. 011038). Secondly, the STOCK Tg (Tnnt2-cre) 5Blh/JiaoJ line, also called TNT-Cre, where Cre recombinase expression is under the control of the rat cardiac troponin T2 promoter, was purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (stock no. 024240). These mice were bred from a mixed background to C57BL/6J for at least one generation upon arrival at the Jackson Laboratory. Thirdly, the Dmdflox and Dlg1flox mouse strains have been generated by by PolyGene AG (Rümlang, Switzerland) (Supplementary Fig. 1)11.

For all experiments, animals were anesthesised by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/xylazine solution (200 mg/kg ketamine and 20 mg/kg xylazine) and killed by cervical dislocation.

Protein extraction and western blot

Whole hearts were extracted from mice, the atria were removed, and ventricles were homogenized in 1 mL lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 10% glycerol, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and Complete® protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland)) using a Polytron. Triton X-100 in lysis buffer was then added to make a final concentration of 1% (final lysate volume 2 mL). Samples were lysed on a rotating wheel for 1 hour at 4 °C. Soluble fractions of the mouse heart lysate were obtained by subsequent centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4 °C. To be able to load similar protein amounts from each sample on a gel, protein concentrations were measured in triplicate by Bradford assay and extrapolated on a bovine serum albumin (BSA) standard curve. Samples were denatured at 95 °C for 5 minutes prior to gel loading. To analyse and compare protein expression, 80 μg of each ventricular mouse heart lysate sample was loaded on a homemade 1.5 mm-thick 8–15% SDS-PAGE gel for high molecular weight proteins. Gels were run at 150 V for 1 hour and proteins were subsequently transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using the Biorad Turbo Transfer System (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA). All membranes were stained with Ponceau as a qualitative check for equivalent total protein loading and transfer. Membranes were then rinsed twice with PBS before western blotting using the SNAP i.d. system (Millipore, Zug, Switzerland). Membranes were blocked with 1% BSA (Sigma) for 10 minutes, followed by incubation with primary antibodies for 10 minutes. Membranes were subsequently washed four times in PBS + 0.1% Tween before incubating with secondary fluorescence antibodies for 10 minutes. After four more washes with PBS + 0.1% Tween and three washes in PBS, fluorescently labelled proteins were detected on a Odyssey® Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences, Bad Homberg, Germany). The protein content was subsequently quantified by measuring and comparing band densities (equivalent to fluorescence intensities of the bands) using the Image Studio software version 5.2.511,26,27.

Immunohistochemistry of mouse ventricular section

Following removal of atria, hearts were cut transversally, embedded in Tissue-Tek® O.C.T™ Compound (Sakura Finetek, Zoeterwoude, the Netherlands), and cryo-preserved. Frozen 10 μm-thick sections were stored at −80 °C until later use. Sections were then thawed to room temperature for 30 minutes and subsequently fixed in ice-cold acetone for 10 minutes. Samples were dried at room temperature for 10 minutes. After rinsing in PBS, sections were blocked in PBS with 0.5% Triton X-100, 1% BSA, and 10% normal goat serum for 30 minutes. Sections were rinsed again in PBS before addition of primary antibodies (in PBS with 0.5% Triton X-100, 1% BSA, and 3% normal goat serum). After 2 hours of incubation, sections were rinsed again in PBS and then incubated for 1 hour with secondary antibodies. After a final wash with PBS, FluorSave™ Reagent (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA) was applied to the sections, which were then stored at 4 °C and analysed on a confocal microscope (Zeiss Z-710)26.

Antibodies

For western blots, a mouse monoclonal anti-dystrophin antibody (NCL-DYS2, Novocastra, Muttenz, Switzerland) was used at a dilution of 1/250. A mouse monoclonal antibody against SAP97 (VAM-PS005F, Enzo life science, Lausen, Switzerland) was used at a dilution of 1/500. Against Nav1.5, a custom-made rabbit polyclonal antibody (Pineda Antibody Service, Berlin) was used at a dilution of 1/200. A rabbit polyclonal antibody against Cre (69050; Novagen, EMD Millipore-MERK, Schaffhausen, Switzerland) was used at a dilution of 1/500 and a rabbit polyclonal antibody against calnexin (C4731; Sigma-Aldrich, Saint-Louis Missouri, USA) was used at 1/100011,26,27.

For immunostainings, rabbit polyclonal antibody against Cre (69050; Novagen, EMD Millipore-MERK, Schaffhausen, Switzerland) was used at a dilution of 1/500 and mouse monoclonal anti-dystrophin (Dys NCL-DYS2, Novocastra, Muttenz, Switzerland) was used at a dilution of 1/25011,26,27.

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from mouse heart pieces with the ExpressArt RNAready kit (Amp Tec GmbH, Germany, provided by the lab of professor Jaggi, Bern, Switzerland). The High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, Switzerland) was used to synthesize cDNA. Subsequently, 25 ng of cDNA was mixed with TaqMan Universal Master Mix (Invitrogen) and 1 µL of either dystrophin (Dmd) or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) probe/primer mix (Applied Biosystems; Mm00464475_m1 and Mm99999915_g1, respectively). GAPDH was used as the reference gene to which experimental data was normalized. All samples were loaded in quadruplicates. On an ABI 7500 RT-PCR machine, samples were run with the following thermal cycling conditions: holding stage at 95 °C for 20 seconds, then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 3 seconds and 60 °C for 30 seconds. Relative Dmd expression (ΔCT) was calculated by subtracting the signal threshold cycle (CT) of the control (GAPDH) from the CT value of Dmd. Results were then linearized by calculating 2exp−(ΔCT)11.

Isolation of mouse ventricular myocytes

Single cardiomyocytes were isolated according to a modified procedure of established enzymatic methods. Briefly, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation. Hearts were rapidly excised, cannulated and mounted on a Langendorff column for retrograde perfusion at 37 °C. Hearts were rinsed free of blood with a nominally Ca2+-free solution containing (in mM): 135 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 10 HEPES, 11 glucose, pH 7.4 (NaOH adjusted), and subsequently digested by a solution supplemented with 50 µM Ca2+ and collagenase type II (1 mg/mL, 300 U/mg, Worthington, Allschwil, Switzerland) for 15 minutes. Following digestion, the atria were removed and the ventricles transferred to nominally Ca2+-free solution, where they were minced into small pieces. Single cardiac myocytes were liberated by gentle trituration of the digested ventricular tissue and filtered through a 100 µm nylon mesh. Ventricular mouse cardiomyocytes were used after an extracellular calcium increase procedure to avoid calcium overload when applying extracellular solutions in electrophysiology assays11,26,27.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell currents were measured at room temperature (22–23 °C) using a VE-2 amplifier (Alembic Instrument, USA). The internal pipette solution was composed of (in mM) 60 CsCl, 70 Cs-aspartate, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 11 EGTA and 5 Mg-ATP, pH 7.2, with CsOH. The external solution contained (in mM) 130 NMDG-Cl, 5 CsCl, 2 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES and 5 D-glucose, pH 7.4, with CsOH. Data were analysed using pClamp software, version 10.2 (Axon Instruments, Union City, California, USA). Calcium current densities (pA/pF) were calculated dividing the peak current by the cell capacitance11,26,27.

Statistical analyses

Data are represented as means ± S.E.M. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism7 GraphPad™ software. Mann-Whitney two-tailed U test was used to compare two groups. One-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare more than two groups. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Stephan Sonntag and Doron Shmerling from Polygene, for the generation of the Dmdflox mouse strain, and to Sarah Vermij for editing and proofreading. This work was supported by EUTrigTreat and from the Swiss National Science Foundation to the Abriel group (310030B_14706035693).

Author contributions

Conception and design of the experiments: L.G., S.G., M.E., J.S.R. and H.A. Collection, analysis and interpretation of data: L.G., S.G., M.E. and J.S.R. Drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content: L.G., J.S.R. and H.A.

Data availability

All data underlying the results are available as part of the article and no additional source data are required.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-55950-w.

References

- 1.Gerlai R. Gene Targeting Using Homologous Recombination in Embryonic Stem Cells: The Future for Behavior Genetics? Front Genet. 2016;7:43. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2016.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsien JZ. Cre-Lox Neurogenetics: 20 Years of Versatile Applications in Brain Research and Counting. Front Genet. 2016;7:19. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2016.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pugach EK, Richmond PA, Azofeifa JG, Dowell RD, Leinwand LA. Prolonged Cre expression driven by the alpha-myosin heavy chain promoter can be cardiotoxic. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;86:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thyagarajan B, Guimaraes MJ, Groth AC, Calos MP. Mammalian genomes contain active recombinase recognition sites. Gene. 2000;244:47–54. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vatta M, et al. Molecular remodelling of dystrophin in patients with end-stage cardiomyopathies and reversal in patients on assistance-device therapy. Lancet. 2002;359:936–941. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavillet B, et al. Cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 is regulated by a multiprotein complex composed of syntrophins and dystrophin. Circ Res. 2006;99:407–414. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000237466.13252.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rougier JS, Gavillet B, Abriel H. Proteasome inhibitor (MG132) rescues Nav1.5 protein content and the cardiac sodium current in dystrophin-deficient mdx (5cv) mice. Front Physiol. 2013;4:51. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albesa M, Ogrodnik J, Rougier JS, Abriel H. Regulation of the cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 by utrophin in dystrophin-deficient mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;89:320–328. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koenig X, et al. Enhanced currents through L-type calcium channels in cardiomyocytes disturb the electrophysiology of the dystrophic heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;306:H564–H573. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00441.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiao K, et al. An essential role of Bmp4 in the atrioventricular septation of the mouse heart. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2362–2367. doi: 10.1101/gad.1124803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillet L, et al. Cardiac-specific ablation of synapse-associated protein SAP97 in mice decreases potassium currents but not sodium current. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wasala NB, et al. Genomic removal of a therapeutic mini-dystrophin gene from adult mice elicits a Duchenne muscular dystrophy-like phenotype. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25:2633–2644. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molkentin JD, Robbins J. With great power comes great responsibility: using mouse genetics to study cardiac hypertrophy and failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buerger A, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy resulting from high-level myocardial expression of Cre-recombinase. J Card Fail. 2006;12:392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Q, Chen J, Qin Y, Wang J, Zhou L. Mutations in voltage-gated L-type calcium channel: implications in cardiac arrhythmia. Channels (Austin) 2018;12:201–218. doi: 10.1080/19336950.2018.1499368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubi, L., Todt, H., Kubista, H., Koenig, X. & Hilber, K. Calcium current properties in dystrophin-deficient ventricular cardiomyocytes from aged mdx mice. Physiol Rep6, 10.14814/phy2.13567 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Li Y, et al. Blunted cardiac beta-adrenergic response as an early indication of cardiac dysfunction in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;103:60–71. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanford LP, Kallapur S, Ormsby I, Doetschman T. Influence of genetic background on knockout mouse phenotypes. Methods Mol Biol. 2001;158:217–225. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-220-1:217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sohal DS, et al. Temporally regulated and tissue-specific gene manipulations in the adult and embryonic heart using a tamoxifen-inducible Cre protein. Circ Res. 2001;89:20–25. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.092687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall ME, Smith G, Hall JE, Stec DE. Systolic dysfunction in cardiac-specific ligand-inducible MerCreMer transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H253–260. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00786.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lexow J, Poggioli T, Sarathchandra P, Santini MP, Rosenthal N. Cardiac fibrosis in mice expressing an inducible myocardial-specific Cre driver. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6:1470–1476. doi: 10.1242/dmm.010470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bersell K, et al. Moderate and high amounts of tamoxifen in alphaMHC-MerCreMer mice induce a DNA damage response, leading to heart failure and death. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6:1459–1469. doi: 10.1242/dmm.010447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiong D, et al. Cardiac-specific, inducible ClC-3 gene deletion eliminates native volume-sensitive chloride channels and produces myocardial hypertrophy in adult mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Werfel S, et al. Rapid and highly efficient inducible cardiac gene knockout in adult mice using AAV-mediated expression of Cre recombinase. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;104:15–23. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carroll KJ, et al. A mouse model for adult cardiac-specific gene deletion with CRISPR/Cas9. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:338–343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523918113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shy D, et al. PDZ domain-binding motif regulates cardiomyocyte compartment-specific NaV1.5 channel expression and function. Circulation. 2014;130:147–160. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rougier JS, et al. A Distinct Pool of Nav1.5 Channels at the Lateral Membrane of Murine Ventricular Cardiomyocytes. Front Physiol. 2019;10:834. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data underlying the results are available as part of the article and no additional source data are required.