Abstract

Denitrification may potentially alleviate excess nitrogen (N) availability in coral holobionts to maintain a favourable N to phosphorous ratio in the coral tissue. However, little is known about the abundance and activity of denitrifiers in the coral holobiont. The present study used the nirS marker gene as a proxy for denitrification potential along with measurements of denitrification rates in a comparative coral taxonomic framework from the Red Sea: Acropora hemprichii, Millepora dichotoma, and Pleuractis granulosa. Relative nirS gene copy numbers associated with the tissues of these common corals were assessed and compared with denitrification rates on the holobiont level. In addition, dinitrogen (N2) fixation rates, Symbiodiniaceae cell density, and oxygen evolution were assessed to provide an environmental context for denitrification. We found that relative abundances of the nirS gene were 16- and 17-fold higher in A. hemprichii compared to M. dichotoma and P. granulosa, respectively. In concordance, highest denitrification rates were measured in A. hemprichii, followed by M. dichotoma and P. granulosa. Denitrification rates were positively correlated with N2 fixation rates and Symbiodiniaceae cell densities. Our results suggest that denitrification may counterbalance the N input from N2 fixation in the coral holobiont, and we hypothesize that these processes may be limited by photosynthates released by the Symbiodiniaceae.

Subject terms: Molecular ecology, Ecophysiology

Introduction

Corals are holobionts consisting of the coral host and a diverse microbiome composed of Symbiodiniaceae (i.e., endosymbiotic dinoflagellates capable of photosynthesis), and prokaryotes, i.e. bacteria and archaea, among other microbes1. Complex symbiotic interactions within these holobionts render corals mixotrophic, that is they can obtain nutrients through both autotrophic and heterotrophic means2–4. The endosymbiotic dinoflagellates, belonging to the family Symbiodiniaceae5, provide the coral with a substantial part of their metabolic energy via autotrophy in the form of photosynthetically fixed carbon (C)6. In return, the Symbiodiniaceae require nutrients from the coral host, e.g. nitrogen (N) and phosphorous (P), which can be obtained via heterotrophic feeding or by uptake from the water column and/or internal (re)cycling7,8.

The involvement of prokaryotes in holobiont nutrient cycling has received increasing attention in recent years. Diazotrophs in particular (microbes capable of fixing atmospheric dinitrogen (N2)) ubiquitously occur in corals9–11 and are recognized as an important source of N for holobiont productivity12–16. Diazotrophs can provide the holobiont with bioavailable N in the form of ammonium, a preferred N source for Symbiodiniaceae17–19, in particular in times of N scarcity11.

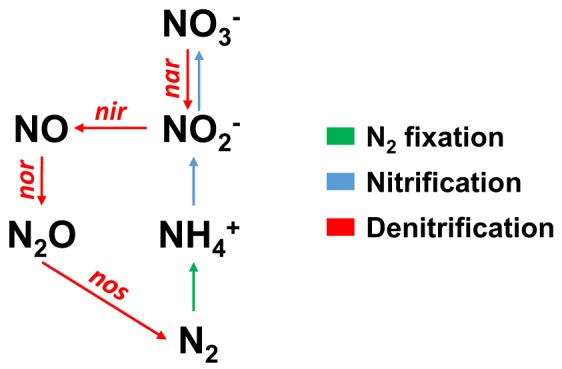

Excess (microbial) input of bioavailable N into the coral holobiont can potentially lead to a misbalance of the N:P ratio, i.e. a shift from N towards P limitation, thereby increasing bleaching susceptibility14,20,21. Previously, it was hypothesized that the activity of other N-cycling microbes could alleviate coral holobionts from nutrient stress via the removal of nitrogenous compounds22. Indeed, ammonium oxidizing (i.e. nitrifying) and nitrate reducing (i.e. denitrifying) prokaryotes occur ubiquitously on coral reefs23–27, including coral holobionts22,28,29. The denitrification pathway in particular may be important for holobiont functioning as it effectively removes bioavailable N. Here, nitrate is reduced to atmospheric N2 via the activity of four main enzymes, i.e. nitrate reductase (converting nitrate to nitrite), nitrite reductase (converting nitrite to nitric oxide), nitric oxide reductase (converting nitric oxide to nitrous oxide), and nitrous oxide reductase (converting nitrous oxide to N2) (Fig. 1)30,31. While Symbiodiniaceae cells are considered a major N sink in the coral holobiont32, excess N could potentially be removed by denitrifying microbes to help maintain an N-limited state14. However, whether removal of excess N via denitrification contributes to holobiont functioning and health remains poorly understood.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of three major pathways involved in nitrogen cycling, including the four gene clusters responsible for denitrification. N2 = atmospheric nitrogen, NH4+ = ammonium, NO2− = nitrite, NO3− = nitrate, NO = nitric oxide, N2O = nitrous oxide, nar = gene cluster for nitrate reductase, nir = gene cluster for nitrite reductase, nor = gene cluster for nitric oxide reductase, nos = gene cluster for nitrous oxide reductase.

Recently, Pogoreutz et al.10 demonstrated that N2 fixation rates may not only be species-specific, but align with relative gene copy numbers and expression of the nifH gene. This pattern was linked to heterotrophic capacity of the investigated corals. However, it is unknown how these patterns of N2 fixation activity ultimately relate to other N-cycling processes, i.e. denitrification, within the coral holobiont. The present study thus aimed to answer (i) whether patterns of denitrification are coral species-specific; (ii) whether relative abundances of the nirS gene (denitrification potential) can be related to denitrification rates; and (iii) whether denitrification aligns with other biological variables within the coral holobiont, specifically N2 fixation, photosynthesis, and cell density of Symbiodiniaceae. These questions were answered in a comparative taxonomic framework of three common Red Sea coral species. Relative gene copy numbers of the nirS gene, which encodes for a nitrite reductase containing cytochrome cd1, were assessed by qPCR to serve as a proxy for denitrification potential of coral tissue-associated prokaryotes. Relative quantification of nirS gene copy numbers was achieved by referencing against the ITS2 region of Symbiodiniaceae. Denitrification and N2 fixation rates were quantified indirectly using a COmbined Blockage/Reduction Acetylene (COBRA) assay (El-Khaled et al. unpublished). Finally, Symbiodiniaceae cell densities were manually counted and photosynthesis was assessed by measuring O2 fluxes.

Results

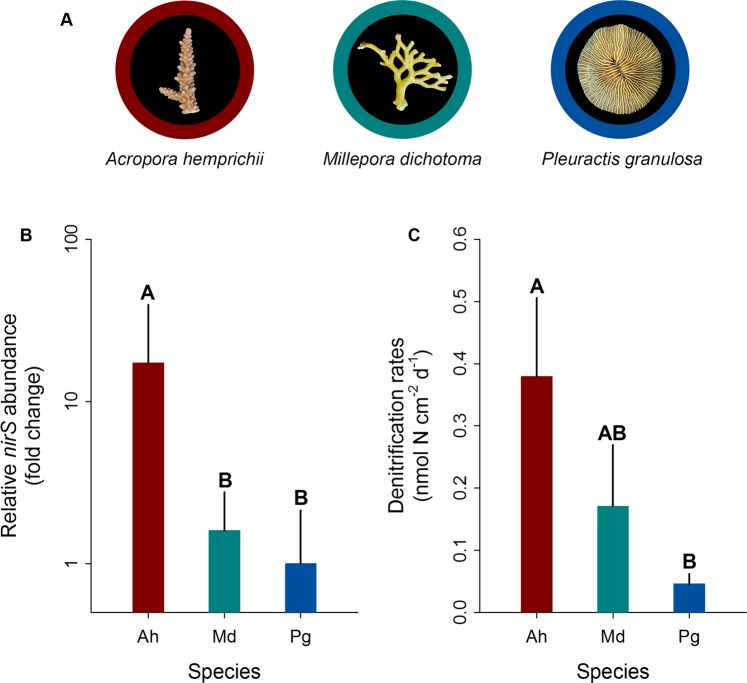

Relative abundances of the nirS gene and denitrification rates

The qPCR confirmed the presence of the nirS gene in the tissues of all investigated corals (Fig. 2A,B). Acropora hemprichii exhibited significantly higher relative nirS gene copy numbers compared to M. dichotoma (~16-fold; pair-wise PERMANOVA, t = 3.82, p = 0.015) and P. granulosa (~17-fold; pair-wise PERMANOVA, t = 3.25, p = 0.029). A similar pattern was found for denitrification rates (Fig. 2C). Acropora hemprichii exhibited the highest denitrification rates (~0.38 ± 0.13 nmol N cm−2 d−1), followed by M. dichotoma (~0.17 ± 0.10 nmol N cm−2 d−1) and P. granulosa (~0.05 ± 0.02 nmol N cm−2 d−1). Denitrification rates in A. hemprichii were significantly different from those in P. granulosa (pair-wise PERMANOVA, t = 2.75, p = 0.036), but not those measured in M. dichotoma (pair-wise PERMANOVA, t = 1.31, p = 0.237). Finally, denitrification rates in M. dichotoma were not significantly different from those in P. granulosa (pair-wise PERMANOVA, t = 1.23, p = 0.264).

Figure 2.

Relative nirS gene copy numbers and rates of denitrification associated with three Red Sea coral species. (A) Representative photographs of investigated species, (B) fold changes in relative nirS gene copy numbers normalized to ITS2 copy numbers as measured by quantitative PCR, and (C) denitrification rates measured indirectly via the combined blockage/reduction acetylene assay (COBRA-assay). Ah = A. hemprichii, Md = M. dichotoma, and Pg = P. granulosa. Fold changes were calculated in relation to P. granulosa; bars indicate the mean; error bars indicate upper confidence intervals (+ 1 SE); n = 4 per species, except Ah and Pg in (B) (n = 3). Different letters above error bars indicate statistically significant differences between groups within each figure (pair-wise PERMANOVAs, p < 0.05).

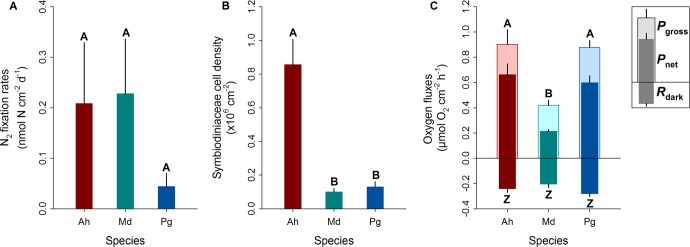

N2 fixation, Symbiodiniaceae cell density and O2 fluxes

N2 fixation rates were highest in M. dichotoma (0.23 ± 0.11 nmol N cm−2 d−1), followed by A. hemprichii (0.21 ± 0.12 nmol N cm−2 d−1), and lowest in P. granulosa (0.04 ± 0.03 nmol N cm−2 d−1) (Fig. 3A). Due to high biological variation in the samples, these differences between coral species were not significant (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Biological variables of three Red Sea corals. (A) N2 fixation rates measured indirectly using a COBRA assay, (B) Symbiodiniaceae cell densities, and (C) oxygen fluxes. Ah = Acropora hemprichii, Md = Millepora dichotoma, and Pg = Pleuractis granulosa. Pgross = gross photosynthesis, Pnet = net photosynthesis, Rdark = dark respiration. Bars indicate the mean; error bars indicate upper confidence intervals (+1 SE); n = 4 per species. Different letters above error bars indicate statistically significant differences within each plot (pair-wise PERMANOVAs, p < 0.05); differences in (C) apply to both Pgross and Pnet.

Cell densities of Symbiodiniaceae were significantly higher in A. hemprichii (0.86 ± 0.15 × 106 cells cm−2) compared to M. dichotoma (0.10 ± 0.02 × 106 cells cm−2; pair-wise PERMANOVA, t = 6.86, p < 0.001) and P. granulosa (0.13 ± 0.03 × 106 cells cm−2; pair-wise PERMANOVA, t = 5.03, p = 0.003) (Fig. 3B). Cell densities of Symbiodiniaceae in M. dichotoma and P. granulosa did not differ significantly (Fig. 3B).

Significantly lower Pnet was found for M. dichotoma (0.21 ± 0.01 µmol O2 cm−2 h−1) compared to that of A. hemprichii (0.66 ± 0.09 µmol O2 cm−2 h−1; pair-wise PERMANOVA, t = 6.55, p = 0.002) and that of P. granulosa (0.60 ± 0.05 µmol O2 cm−2 h−1; pair-wise = PERMANOVA, t = 8.95, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3C). The same pattern was found for Pgross; M. dichotoma exhibited significantly lower Pgross (0.42 ± 0.04 µmol O2 cm−2 h−1) than that of A. hemprichii (0.90 ± 0.12 µmol O2 cm−2 h−1; pair-wise PERMANOVA, t = 4.14, p = 0.007) and that of P. granulosa (0.88 ± 0.06 µmol O2 cm−2 h−1; pair-wise PERMANOVA, t = 6.21, p = 0.002) (Fig. 3C). No significant differences were found for Rdark between species (PERMANOVA, Pseudo-F = 1.73, p = 0.243) (Fig. 3C).

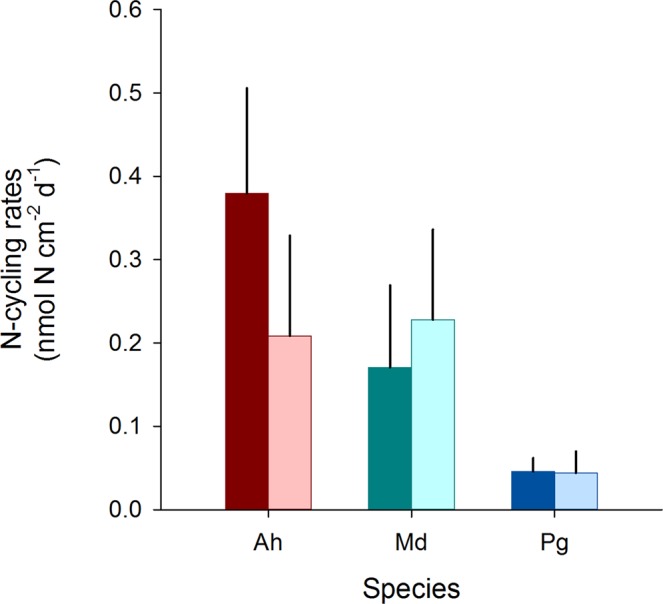

Comparison of denitrification rates and N2 fixation rates

No significant differences were found between denitrification and N2 fixation rates for either species (T-test, p > 0.05; Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison of denitrification rates and N2 fixation rates of three Red Sea coral species. Ah = Acropora hemprichii, Md = Millepora dichotoma, and Pg = Pleuractis granulosa. Bars indicate the mean; error bars indicate upper confidence intervals (+1 SE); dark bars represent denitrification rates; light bars represent N2 fixation rates; n = 4 per species.

Correlation analyses

The biological variable that best explained the denitrification rates was N2 fixation (BIOENV, r = 0.654, p = 0.004). The combination of biological variables that explained denitrification rates best were N2 fixation and Symbiodiniaceae cell density (BIOENV, r = 0.592, p = 0.002). Indeed, 85.6% of the variation in denitrification rates could be explained by N2 fixation and Symbiodiniaceae cell density (DistLM).

The biological variable that best explained the N2 fixation rates was denitrification (BIOENV, r = 0.651, p = 0.006). The combination of biological variables that explained N2 fixation best were denitrification and Symbiodiniaceae cell density (BIOENV, r = 0.342, p = 0.046). Indeed, 82.9% of the variation in N2 fixation rates could be explained by denitrification and Symbiodiniaceae cell density (DistLM).

Discussion

Despite the importance of N as a key nutrient for the metabolism of symbiotic corals33, relatively little is known about the removal of N by microbes in the internal N-cycling of coral holobionts12,14. Here, we assessed relative abundances of coral tissue-associated denitrifiers (using relative gene copy numbers of the nirS gene as a proxy), as well as denitrification and N2 fixation rates on the holobiont level in a comparative taxonomic framework using three common Red Sea corals. Our results suggest that denitrification is an active N-cycling pathway in coral holobionts and may be linked with diazotroph activity and Symbiodiniaceae cell density, the interplay of which may have important implications for coral holobiont nutrient cycling.

It was previously hypothesized that coral associated N-cycling microbes may have a capacity to alleviate nutrient stress via the removal of bioavailable N14,22,28,29. While the community structure and phylogenetic diversity of denitrifying microbes have been previously assessed in a soft and a hard coral29, we here present the first study to link relative coral tissue-associated abundances of denitrifying prokaryotes with denitrification rates. Our findings highlight that denitrification may play a role in removing bioavailable N from the coral holobiont. The contribution and hence potential functional importance of denitrification may depend on the host species.

In the present study, the highest relative nirS gene copy numbers were found in A. hemprichii, while lower relative numbers were observed in M. dichotoma and P. granulosa. The patterns in relative abundance of the nirS gene obtained through qPCR were largely reflected in denitrification rates measured using a COBRA assay. As such, these data suggest that relative nirS gene abundance may be a suitable proxy of denitrification potential in corals. Small deviations in the patterns observed for both measurements may be potentially explained by a) differences in the community composition of denitrifying microbes; fungi involved in N metabolism may be present in coral holobionts34 and likely lack a (homologous) nirS gene35, by b) the multi-copy nature of the ITS236,37; by relating nirS to ITS2, the relative abundances of nirS genes could potentially be underestimated, and by c) the potential presence of denitrifying microbes in the coral skeleton29,38–40.

The present study identified a positive correlation between denitrification and N2 fixation activity across the three Red Sea coral species investigated. As such, denitrification may have the capacity to counterbalance N input from N2 fixation in coral holobionts. We here propose that these processes may be indirectly linked by their similar environmental requirements and constraints.

Denitrification as well as N2 fixation are anaerobic processes31,41. However, in the present study, no relationship was found between O2 fluxes and denitrification and N2 fixation rates. This strongly suggests that the activity of these anaerobic processes may be spatially or temporally separated from O2 evolution in the coral holobiont, or that the involved N-cycling prokaryotes are capable of supporting these processes in the presence of O242–45. In addition to anaerobic conditions, most denitrifiers and diazotrophs require organic C as their energy source, i.e. are heterotrophic9,46–48. Besides the uptake of organic C from the water column49 and heterotrophic feeding by the coral host, the Symbiodiniaceae are the main source of C-rich photosynthates within the holobiont50. Notably, the present study showed a positive correlation between denitrification rates with N2 fixation combined with Symbiodiniaceae cell density. In addition, a positive correlation was also shown for N2 fixation, namely with denitrification combined with Symbiodiniaceae cell density. This suggest that the heterotrophic prokaryotes of both N-cycling pathways may rely partially on Symbiodiniaceae for obtaining organic C for respiration. As such, the correlation of denitrification and N2 fixation may be the result of a shared organic C limitation within the holobiont14. However, a potential functional relationship between N-cycling prokaryotes and phototrophic Symbiodiniaceae remains yet to be determined.

The observed positive correlation between the two N-cycling pathways, i.e. denitrification and N2 fixation, may have important implications for the general understanding of nutrient cycling within coral holobionts, and hence our understanding of coral ecology. In a stable healthy holobiont, N input from N2 fixation may be compensated for by N removal via denitrification. As such, the activity of these two processes should be interpreted in relation to each other to understand their overall effect on holobiont N availability, and hence nutrient dynamics.

Environmental stress may directly affect the equilibrium of these processes, as both eutrophication and the increase in sea surface temperatures directly affect N-cycling within the coral holobiont14. Increases in inorganic N availability may lead to a reduction of diazotroph activity in coral holobionts due to the so called “ammonia switch-off”51, which is evidenced by negative correlations between N availability and N2 fixation for both planktonic and benthic diazotrophs52–54. Denitrification, on the one hand, may even be stimulated by increased nitrate availability31. This hypothesized interplay of denitrification and N2 fixation would hence allow coral holobionts to effectively remove excessive N14.

Increased sea surface temperatures, on the other hand, may directly stimulate N2 fixation55. While the environmental drivers for stimulated N2 fixation activity are not fully resolved yet, increased diazotrophy may affect holobiont functioning if not compensated for by denitrification activity10. However, with increasing water temperature, Symbiodiniaceae may retain more photosynthates for their own metabolism56, potentially limiting organic C availability not only for the coral host, but also for heterotrophic microbes, including denitrifiers. Thus, microbial N-cycling may be more important in highly autotrophic coral holobionts, as they rely more on the Symbiodiniaceae for organic C and may be more susceptible to potential nutrient imbalances due to e.g. increased diazotrophic activity10. Indeed, the capacity for heterotrophic feeding has been linked to having a lower susceptibility to warming57–60 and eutrophication61. However, besides the potential ability to remove bioavailable N from the coral holobiont, the role of denitrifiers under (non-)stressful scenarios remains speculative at this point. Thus, future research could focus on several aspects to disentangle a potential role of denitrification in the context of microbial N-cycling within coral holobionts by (a) identifying the spatial niche that denitrifiers occupy and in which abundances; (b) identifying the denitrifiers’ primary energy source(s) under regular and stressed (e.g. eutrophic or warming) conditions; (c) by quantifying and assessing the interplay of denitrification with other N-cycling processes (potentially) ubiquitous in coral holobionts, e.g. N2 fixation, nitrification and ANAMMOX, through molecular, physiological and/or isotope analyses; and (d) how the interplay of N-cycling processes in the coral holobiont is altered in global change scenarios.

Methods

Sample collection, aquarium facilities, and maintenance

This study was conducted at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) in Saudi Arabia. Three common coral species were selected (Fig. 2A) and collected at approx. 5 m water depth at the semi-exposed side of the inshore reef Abu Shosha (N22°18′15″, E39°02′56″) located in the Saudi Arabian central Red Sea in November 2017; specifically, the acroporid coral Acropora hemprichii (n = 4 colonies), the hydrozoan Millepora dichotoma (n = 4 colonies), and the fungiid coral Pleuractis granulosa (n = 8 polyps). Coral colonies of the same species were sampled at least 10 m apart to account for genetic diversity. After collection, the corals were transferred to recirculation aquaria filled with reef water on the vessel, and subsequently transported to the wet lab facility of the Coastal and Marine Resources (CMOR) Core Lab at KAUST. The branching corals A. hemprichii and M. dichotoma were immediately fragmented into two fragments of similar size each. Fragments were distributed into four independent replicate 150 L flow-through tanks, i.e. each tank held two distinct fragments of each branching coral species (see Supplementary Fig. S1). Individual polyps of P. granulosa were not fragmented and distributed randomly over the four tanks. Fragments/polyps were left to acclimate for two weeks prior to the start of measurements. All tanks were continuously supplied with sediment-filtered seawater (flow through rate 300 L h−1) from inshore reefs located 1.5 km off KAUST with the following parameters: temperature 27 °C, salinity 40 PSU, and dissolved oxygen (O2) 6.4 mg O2 L−1. All fragments were exposed to a photon flux of ~150 µmol m−2 s−1 62 on a 12:12 h light/dark cycle. Corals were kept in nutrient-rich seawater (nitrate ~3 µM, phosphate ~0.40 µM) to stimulate denitrification response in coral holobionts63–65. For each measurement, one fragment/polyp of each species per tank was taken, avoiding sampling fragments that originated from the same colony. This resulted in four fragments/polyps per species from four different colonies for each measurement (see Supplementary Fig. S1).

DNA extraction and relative quantification of the nirS gene via quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Quantitative PCR was used to quantify relative gene copy numbers of the nirS gene as a proxy for abundance of denitrifying prokaryotes in the coral tissues, i.e. denitrification potential. To this end, the coral tissue was removed from the skeleton by airblasting with RNase free water and pressurized air using a sterilized airbrush (Agora-Tec GmbH, Schmalkalden, Germany). For P. granulosa, tissue was blasted off from both top and bottom surfaces and was pooled subsequently. The resulting tissue slurries were homogenized using an Ultra Turrax (for approx. 20 s) and stored at -20 °C until further processing. Total DNA was extracted from 100 µL of tissue slurry using the Qiagen DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions. DNA extraction yields were determined using a NanoDrop 2000C spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). DNA concentrations were adjusted to 2 ng µL−1 and stored at −20 °C until further processing.

qPCR assays were performed in technical triplicates for each coral fragment or polyp. Each assay contained 9 μL reaction mixture and 1 μL DNA template. Reaction mixture contained Platinum SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States), 0.2 μL of each primer (10 µM, see below and details of primer assessment in the Supplementary Methods), 0.2 μL of ROX dye and 3.4 μL of RNAse-free water. Negative controls (i.e., reactions consisting of only qPCR reagents and nuclease-free water without any DNA added) were included in the assay in technical triplicates to account for potential laboratory and kit contamination. The relative number of nirS gene copies (i.e. relative abundance of denitrifiers) was determined by normalization against the multi copy gene marker ITS2 of Symbiodiniaceae as previously used for the normalization of nifH gene copy numbers in a comparative taxonomic coral framework10. A total of 18 primers covering all main enzymes in the denitrification pathway (Fig. 1) were tested for this study and yielded ten primer pairs that produced PCR products in the suggested size range (see details of primer assessment in the Supplementary Methods). Temperature gradient PCRs were applied (from 51 °C to 62 °C) to assess the optimal annealing temperature of every primer pair (see details of primer assessment in the Supplementary Methods). Due to substantial differences in amplification performance of primer pairs, we selected a primer pair for nirS which encodes for a nitrite reductase containing cytochrome cd1 as the target gene. For the amplification of nirS, the primers cd3aF 5′-GTSAACGTSAAGGARACSGG-3′ and R3cd 5′-GASTTCGGRTGSGTCTTGA-3′ were used66. This primer pair was previously found to perform well with DNA from other marine templates, such as coral rock24, marine sediments67, as well as environmental samples from intertidal zones68, and terrestrial ecosystems47,69,70. To amplify the ITS2 region of Symbiodiniaceae the primers SYM_VAR_5.8S2 5′-GAATTGCAGAACTCCGTGAACC -3′ and SYM_VAR_REV 5′-CGGGTTCWCTTGTYTGACTTCATGC -3′ were used71. The thermal cycling protocol used for the amplification of both target genes was 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 2 min, 50 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 51 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 1 min, and a final 72 °C extension cycle for 2 min. Amplification specificity was determined by adding a dissociation step. All assays were performed on the ABI 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). Standard calibration curves were run simultaneously covering 5 orders of magnitude (103–107 copies of template per assay for the ITS2 and nirS gene). The qPCR efficiency (E) of both primer pairs was 84% and 86%, respectively, calculated according to the equation E = [10(−1/slope)-1]. Relative fold change of nirS gene copies were calculated as 2(−∆∆Ct) against ITS2 Ct values using P. granulosa samples as the reference.

Throbäck et al.72 assessed a range of nirS primer pairs and concluded that the primer pair used in the present study (i.e. cd3aF and R3cd) had the largest range and worked best for nirS gene assessments. Currently, there are no optimal universal primers for the amplification of the nirS gene available73. Any quantification of nirS abundances is hence biased by the primer pair used and its suitability strongly depends on the phylogenetic diversity of the template. Thus, while the primer combination used here shows a high coverage of 67% of known nirS diversity73, our results can only provide an approximation of the relative abundance of denitrifying bacteria across samples until more (meta)genomic data for coral-associated denitrifiers are available.

Denitrification and N2 fixation measurements

To measure denitrification and N2 fixation rates simultaneously, we incubated corals using a COBRA assay, as described in El-Khaled et al. (unpublished). Of note, acetylene inhibits the production of nitrate in the nitrification pathway74,75. As nitrate serves as a substrate for denitrification, the inhibition of nitrification may thus result in an underestimation of denitrification rates. To compensate for such effects, nutrient-rich incubation water was used to preclude substrate limitation63–65.

Briefly, incubations were conducted in gas-tight 1 L glass chambers, each filled with 800 mL of nutrient-rich sediment-filtered seawater (DIN = ~3 µM, phosphate = ~0.40 µM) and a 200 mL gas headspace. Both incubation water and headspace were enriched with 10% acetylene. Each chamber contained a single A. hemprichii or M. dichotoma fragment or P. granulosa polyp. Incubations of four biological replicates per species were performed (see Supplementary Fig. S1), and three additional chambers without corals served as controls to correct for planktonic background metabolism. During the 24 h incubations, chambers were submersed in a temperature-controlled water bath and constantly stirred (500 rpm) to create a constant water motion and homogenous environment (27 °C, 12:12 h dark/light cycle, photon flux of ~150 µmol m−2 s−1). Nitrous oxide (N2O; as a proxy for denitrification) and ethylene (C2H4; as a proxy for N2 fixation) concentrations were quantified by gas chromatography and helium pulsed discharge detection (Agilent 7890B GC system with HP-Plot/Q column, lower detection limit for both target gases was 0.3 ppm). To facilitate comparisons of both N-cycling processes, N2O and C2H4 production rates were converted into N production using molar ratios of N2O:N2 = 1 and C2H4:N2 = 376, and multiplying by 2 to convert N2 to N, resulting in rates of nmol N cm−2 d−1. Gas concentrations were normalized to coral surface area, which was calculated using cloud-based 3D models of samples (Autodesk Remake v19.1.1.2)77,78.

Symbiodiniaceae cell density

Tissue slurry for DNA extraction was also used to obtain cell densities of Symbiodiniaceae (see Supplementary Fig. S1). Symbiodiniaceae cell densities were obtained by manual counts of homogenized aliquots of 20 µL, which were diluted 5 times, using a Neubauer-improved hemocytometer on a light microscope with HD camera (Zeiss, Germany). Resulting photographs were analysed using the Cell Counter Notice in ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, USA). Cell counts for each individual were done in duplicates and subsequently averaged. Finally, cell counts were normalized to coral surface area to obtain cell densities of Symbiodiniaceae for each fragment or polyp.

O2 fluxes

Net photosynthesis (Pnet) and dark respiration (Rdark) were assessed from O2 evolution/depletion measurements with the same fragments/polyps 2 days prior to using them for denitrification and N2 fixation rate measurements. Corals were incubated for 2 h in individual gas-tight 1 L glass chambers, filled with nutrient-rich sediment-filtered seawater (DIN = ~3 µM, phosphate = ~0.40 µM). Each chamber contained a single A. hemprichii or M. dichotoma fragment or P. granulosa polyp. Incubations of four biological replicates per species were performed (see Supplementary Fig. S1), and three additional chambers without corals served as controls to correct for planktonic background metabolism. During the incubations, chambers were submersed in a temperature-controlled water bath (kept at 27 °C) and constantly stirred (500 rpm) to create a continuous water motion and homogenous environment. Light incubations for Pnet were performed under a photon flux of ~150 µmol m−2 s−1. Rdark was obtained by incubating in complete darkness. O2 concentrations were measured at the start and end of the respective incubation period using an optical oxygen multiprobe (WTW, Germany). O2 concentrations at the start of the incubation were subtracted from O2 concentrations at the end, corrected for controls and normalized to incubation time and surface area of the corals. Rdark is presented as a negative rate. Finally, gross photosynthesis (Pgross) was calculated as the difference between Pnet and Rdark as follows:

Statistical analyses

Data were analysed using non-parametric permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) using PRIMER-E version 6 software79 with the PERMANOVA+ add on80. To test for differences in relative nirS gene copy numbers, denitrification rates, N2 fixation rates, Symbiodiniaceae cell densities and O2 fluxes between species, 1-factorial PERMANOVAs were performed, based on Bray-Curtis similarities of square-root transformed data. Therefore, Type III (partial) sum of squares was used with unrestricted permutation of raw data (999 permutations), and PERMANOVA pairwise tests with parallel Monte Carlo tests were carried out when significant differences were found.

Differences between denitrification and N2 fixation rates within each coral species were assessed using SigmaPlot 12.0 (Systat software). T-tests were performed for normally distributed data and Mann-Whitney U tests were performed when data were not normally distributed .

Additionally, to identify the biological variable (single trial variable) and combination of biological variables (multiple trial variables) that “best explains” the denitrification rate pattern of the coral samples, a Biota and/or Environment matching routine (BIOENV) was performed with 999 permutations based on Spearman Rank correlations. A distance-based linear model (DistLM) using a step-wise selection procedure with AICc as a selection criterion was used to calculate the explanatory power of correlating biological variables79,81. Finally, the same BIOENV and DistLM routine was performed for N2 fixation rates of the coral samples.

As P. granulosa consisted of four individual polyps per measurement (no technical replicates originating from the same polyp), data for each variable were averaged and used as a single data point in analyses unless the same individuals were used (see Supplementary Fig. S1). All values are given as mean ± SE.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank KAUST CMOR staff and boat crews for their support with diving operations.

Author contributions

All authors conceived and designed the experiment. A.T. and Y.E.K. conducted the experiments and analysed samples. A.T. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors revised drafts of the manuscript.

Data availability

Raw data of the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-55408-z.

References

- 1.Rohwer F, Seguritan V, Azam F, Knowlton N. Diversity and distribution of coral-associated bacteria. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2002;243:1–10. doi: 10.3354/meps243001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furla P, et al. The symbiotic anthozoan: A physiological chimera between alga and animal. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2005;45:595–604. doi: 10.1093/icb/45.4.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahav O, Dubinsky Z, Achituv Y, Falkowski PG. Ammonium metabolism in the zooxanthellate coral, Stylophora pistillata. Proc. R. Soc. 1989;337:325–337. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1989.0026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Houlbrèque F, Ferrier-Pagès C. Heterotrophy in tropical scleractinian corals. Biol. Rev. 2009;84:1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LaJeunesse TC, et al. Systematic revision of Symbiodiniaceae highlights the antiquity and diversity of coral endosymbionts. Curr. Biol. 2018;28:2570–2580.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muscatine L, Porter JW. Reef corals: mutualistic symbioses adapted to nutrient-poor environments. Bioscience. 1977;27:454–460. doi: 10.2307/1297526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muscatine L, et al. Cell-specific density of symbiotic dinoflagellates in tropical anthozoans. Coral Reefs. 1998;17:329–337. doi: 10.1007/s003380050133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yellowlees D, Rees TAV, Leggat W. Metabolic interactions between algal symbionts and invertebrate hosts. Plant, Cell Environ. 2008;31:679–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lema KA, Willis BL, Bourne DG. Corals form characteristic associations with symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:3136–3144. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07800-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pogoreutz C, et al. Nitrogen fixation aligns with nifH abundance and expression in two coral trophic functional groups. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:1187. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cardini U, et al. Functional significance of dinitrogen fixation in sustaining coral productivity under oligotrophic conditions. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015;282:20152257. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benavides M, et al. Diazotrophs: a non-negligible source of nitrogen for the tropical coral Stylophora pistillata. J. Exp. Biol. 2016;219:2608–2612. doi: 10.1242/jeb.139451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benavides, M., Bednarz, V. N. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. Diazotrophs: Overlooked key players within the coral symbiosis and tropical reef ecosystems? Front. Mar. Sci. 4 (2017).

- 14.Rädecker Nils, Pogoreutz Claudia, Voolstra Christian R., Wiedenmann Jörg, Wild Christian. Nitrogen cycling in corals: the key to understanding holobiont functioning? Trends in Microbiology. 2015;23(8):490–497. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lesser MP, et al. Nitrogen fixation by symbiotic cyanobacteria provides a source of nitrogen for the scleractinian coral Montastraea cavernosa. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2007;346:143–152. doi: 10.3354/meps07008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robbins Steven J., Singleton Caitlin M., Chan Cheong Xin, Messer Lauren F., Geers Aileen U., Ying Hua, Baker Alexander, Bell Sara C., Morrow Kathleen M., Ragan Mark A., Miller David J., Forêt Sylvain, Voolstra Christian R., Tyson Gene W., Bourne David G. A genomic view of the reef-building coral Porites lutea and its microbial symbionts. Nature Microbiology. 2019;4(12):2090–2100. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0532-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Elia CF, Domotor SL, Webb KL. Nutrient uptake kinetics of freshly isolated zooxantellae. Mar. Biol. 1983;75:157–167. doi: 10.1007/BF00405998. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taguchi S, Kinzie RA., III Growth of zooxanthellae in culture with two nitrogen sources. Mar. Biol. 2001;138:149–155. doi: 10.1007/s002270000435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grover R, Maguer J-F, Allemand D, Ferrier-Pagès C. Nitrate uptake in the scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2003;48:2266–2274. doi: 10.4319/lo.2003.48.6.2266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiedenmann J, et al. Nutrient enrichment can increase the susceptibility of reef corals to bleaching. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013;3:160–164. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1661. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pogoreutz C, et al. Sugar enrichment provides evidence for a role of nitrogen fixation in coral bleaching. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2017;23:3838–3848. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siboni N, Ben-Dov E, Sivan A, Kushmaro A. Global distribution and diversity of coral-associated Archaea and their possible role in the coral holobiont nitrogen cycle. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;10:2979–2990. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobolev D, Boyett MR, Cruz-Rivera E. Detection of ammonia-oxidizing Bacteria and Archaea within coral reef cyanobacterial mats. J. Oceanogr. 2013;69:591–600. doi: 10.1007/s10872-013-0195-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuen YS, Yamazaki SS, Nakamura T, Tokuda G, Yamasaki H. Effects of live rock on the reef-building coral Acropora digitifera cultured with high levels of nitrogenous compounds. Aquac. Eng. 2009;41:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaeng.2009.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Capone DG, Dunham SE, Horrigan SG, Duguay LE. Microbial nitrogen transformations in unconsolidated coral reef sediments. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1992;80:75–88. doi: 10.3354/meps080075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaidos E, Rusch A, Ilardo M. Ribosomal tag pyrosequencing of DNA and RNA from benthic coral reef microbiota: community spatial structure, rare members and nitrogen-cycling guilds. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;13:1138–1152. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rusch A, Gaidos E. Nitrogen-cycling bacteria and archaea in the carbonate sediment of a coral reef. Geobiology. 2013;11:472–484. doi: 10.1111/gbi.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kimes NE, Van Nostrand JD, Weil E, Zhou J, Morris PJ. Microbial functional structure of Montastraea faveolata, an important Caribbean reef-building coral, differs between healthy and yellow-band diseased colonies. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;12:541–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang S, Sun W, Zhang F, Li Z. Phylogenetically diverse denitrifying and ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in corals Alcyonium gracillimum and Tubastraea coccinea. Mar. Biotechnol. 2013;15:540–551. doi: 10.1007/s10126-013-9503-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jetten MSM. The microbial nitrogen cycle. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;10:2903–2909. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zumft WG. Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1997;61:533–616. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.4.533-616.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pernice M, et al. A single-cell view of ammonium assimilation in coral-dinoflagellate symbiosis. ISME J. 2012;6:1314–1324. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Béraud E, Gevaert F, Rottier C, Ferrier-Pagès C. The response of the scleractinian coral Turbinaria reniformis to thermal stress depends on the nitrogen status of the coral holobiont. J. Exp. Biol. 2013;216:2665–2674. doi: 10.1242/jeb.085183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wegley L, Edwards R, Rodriguez-Brito B, Liu H, Rohwer F. Metagenomic analysis of the microbial community associated with the coral Porites astreoides. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;9:2707–2719. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shoun H, Fushinobu S, Jiang L, Kim S-W, Wakagi T. Fungal denitrification and nitric oxide reductase cytochrome P450nor. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2012;367:1186–1194. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arif C, et al. Assessing Symbiodinium diversity in scleractinian corals via next-generation sequencing-based genotyping of the ITS2 rDNA region. Mol. Ecol. 2014;23:4418–4433. doi: 10.1111/mec.12869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.LaJeunesse TC. Diversity and community structure of symbiotic dinoflagellates from Caribbean coral reefs. Mar. Biol. 2002;141:387–400. doi: 10.1007/s00227-002-0829-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marcelino VR, van Oppen MJH, Verbruggen H. Highly structured prokaryote communities exist within the skeleton of coral colonies. ISME J. 2018;12:300–303. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang S-H, et al. Metagenomic, phylogenetic, and functional characterization of predominant endolithic green sulfur bacteria in the coral Isopora palifera. Microbiome. 2019;7:3. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0616-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pernice, M. et al. Down to the bone: the role of overlooked endolithic microbiomes in reef coral health. ISME J. 10.1038/s41396-019-0548-z (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Compaoré J, Stal LJ. Effect of temperature on the sensitivity of nitrogenase to oxygen in two heterocystous cyanobacteria. J. Phycol. 2010;46:1172–1179. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2010.00899.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silvennoinen H, Liikanen A, Torssonen J, Stange CF, Martikainen PJ. Denitrification and N2O effluxes in the Bothnian Bay (northern Baltic Sea) river sediments as affected by temperature under different oxygen concentrations. Biogeochemistry. 2008;88:63–72. doi: 10.1007/s10533-008-9194-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lloyd D, Boddy L, Davies KJP. Persistence of bacterial denitrification capacity under aerobic conditions: the rule rather than the exception. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1987;45:185–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1987.tb02354.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berman-Frank I, et al. Segregation of nitrogen fixation and oxygenic photosynthesis in the marine cyanobacterium Trichodesmium. Science (80-.). 2001;294:1534–1537. doi: 10.1126/science.1064082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bednarz VN, et al. Contrasting seasonal responses in dinitrogen fixation between shallow and deep-water colonies of the model coral Stylophora pistillata in the northern Red Sea. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0199022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Her J-J, Huang J-S. Influences of carbon source and C/N ratio on nitrate/nitrite denitrification and carbon breakthrough. Bioresour. Technol. 1995;54:45–51. doi: 10.1016/0960-8524(95)00113-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen S, et al. Organic carbon availability limiting microbial denitrification in the deep vadose zone. Environ. Microbiol. 2018;20:980–992. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olson ND, Ainsworth TD, Gates RD, Takabayashi M. Diazotrophic bacteria associated with Hawaiian Montipora corals: Diversity and abundance in correlation with symbiotic dinoflagellates. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 2009;371:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2009.01.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sorokin YI. On the feeding of some scleractinian corals with bacteria and dissolved organic matter. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1973;18:380–385. doi: 10.4319/lo.1973.18.3.0380. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Falkowski PG, Dubinsky Z, Muscatine L, Porter JW. Light and the bioenergetics of a symbiotic coral. Bioscience. 1984;34:705–709. doi: 10.2307/1309663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kessler PS, Daniel C, Leigh JA. Ammonia switch-off of nitrogen fixation in the methanogenic archaeon Methanococcus maripaludis: mechanistic features and requirement for the novel GlnB homologues, Nifl1 and Nifl2. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:882–889. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.3.882-889.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tilstra A, et al. Effects of water column mixing and stratification on planktonic primary production and dinitrogen fixation on a northern Red Sea coral reef. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:2351. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bednarz VN, Cardini U, van Hoytema N, Al-Rshaidat MMD, Wild C. Seasonal variation in dinitrogen fixation and oxygen fluxes associated with two dominant zooxanthellate soft corals from the northern Red Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2015;519:141–152. doi: 10.3354/meps11091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rix L, et al. Seasonality in dinitrogen fixation and primary productivity by coral reef framework substrates from the northern Red Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2015;533:79–92. doi: 10.3354/meps11383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Santos HF, et al. Climate change affects key nitrogen-fixing bacterial populations on coral reefs. ISME J. 2014;8:2272–2279. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baker DM, Freeman CJ, Wong JCY, Fogel ML, Knowlton N. Climate change promotes parasitism in a coral symbiosis. ISME J. 2018;12:921–930. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0046-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McClanahan TR, Baird AH, Marshall PA, Toscano MA. Comparing bleaching and mortality responses of hard corals between southern Kenya and the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2004;48:327–335. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2003.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tremblay, P., Gori, A., Maguer, J. F., Hoogenboom, M. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. Heterotrophy promotes the re-establishment of photosynthate translocation in a symbiotic coral after heat stress. Sci. Rep. 6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Wooldridge SA. Formalising a mechanistic linkage between heterotrophic feeding and thermal bleaching resistance. Coral Reefs. 2014;33:1131–1136. doi: 10.1007/s00338-014-1193-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grottoli AG, Rodrigues LJ, Palardy JE. Heterotrophic plasticity and resilience in bleached corals. Nature. 2006;440:1186–1189. doi: 10.1038/nature04565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seemann, J. et al. Importance of heterotrophic adaptations of corals to maintain energy reserves. Proc. 12th Int. Coral Reef Symp. 9–13 (2012).

- 62.Roth F, et al. Coral reef degradation affects the potential for reef recovery after disturbance. Mar. Environ. Res. 2018;142:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2018.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Haines JR, Atlas RM, Griffiths RP, Morita RY. Denitrification and nitrogen fixation in Alaskan continental shelf sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1981;41:412–21. doi: 10.1128/aem.41.2.412-421.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Joye SB, Paerl HW. Contemporaneous nitrogen fixation and denitrification in intertidal microbial mats: rapid response to runoff events. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1993;94:267–274. doi: 10.3354/meps094267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miyajima T, Suzumura M, Umezawa Y, Koike I. Microbiological nitrogen transformation in carbonate sediments of a coral-reef lagoon and associated seagrass beds. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2001;217:273–286. doi: 10.3354/meps217273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Michotey V, Méjean V, Bonin P. Comparison of methods for quantification of cytochrome cd1-denitrifying bacteria in environmental marine samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:1564–1571. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.4.1564-1571.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nakano M, Shimizu Y, Okumura H, Sugahara I, Maeda H. Construction of a consortium comprising ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and denitrifying bacteria isolated from marine sediment. Biocontrol Sci. 2008;13:73–89. doi: 10.4265/bio.13.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dini-Andreote F, Brossi MJL, van Elsas JD, Salles JF. Reconstructing the genetic potential of the microbially-mediated nitrogen cycle in a salt marsh ecosystem. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:902. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jung J, et al. Change in gene abundance in the nitrogen biogeochemical cycle with temperature and nitrogen addition in Antarctic soils. Res. Microbiol. 2011;162:1018–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jung J, Yeom J, Han J, Kim J, Park W. Seasonal changes in nitrogen-cycle gene abundances and in bacterial communities in acidic forest soils. J. Microbiol. 2012;50:365–373. doi: 10.1007/s12275-012-1465-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hume BCC, et al. An improved primer set and amplification protocol with increased specificity and sensitivity targeting the Symbiodinium ITS2 region. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4816. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Throbäck IN, Enwall K, Jarvis Å, Hallin S. Reassessing PCR primers targeting nirS, nirK and nosZ genes for community surveys of denitrifying bacteria with DGGE. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2004;49:401–417. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bonilla-Rosso G, Wittorf L, Jones CM, Hallin S. Design and evaluation of primers targeting genes encoding NO-forming nitrite reductases: Implications for ecological inference of denitrifying communities. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–8. doi: 10.1038/srep39208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hynes RK, Knowles R. Inhibition by acetylene of ammonia oxidation in Nitrosomonas europaea. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1978;4:319–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1978.tb02889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Oremland Ronald S., Capone Douglas G. Advances in Microbial Ecology. Boston, MA: Springer US; 1988. Use of “Specific” Inhibitors in Biogeochemistry and Microbial Ecology; pp. 285–383. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hardy RWF, Holsten RD, Jackson EK, Burns RC. The acetylene - ethylene assay for N2 fixation: laboratory and field evaluation. Plant Physiol. 1968;43:1185–1207. doi: 10.1104/pp.43.8.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lavy A, et al. A quick, easy and non-intrusive method for underwater volume and surface area evaluation of benthic organisms by 3D computer modelling. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015;6:521–531. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gutierrez-Heredia L, Benzoni F, Murphy E, Reynaud EG. End to end digitisation and analysis of three-dimensional coral models, from communities to corallites. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149641. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Clarke, K. R. & Gorley, R. N. PRIMER v6: Users Manual/Tutorial. 1–192 (2006).

- 80.Anderson MJ. A new method for non parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001;26:32–46. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Anderson, M. J., Gorley, R. N. & KR, C. PERMANOVA + for PRIMER: Guide to software and statistical methods. (2008).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw data of the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.