Abstract

Objectives:

Despite the importance of immunological memory for protective immunity against viral infection, whether H7N9-specific antibodies and memory T-cell responses remain detectable years after the original infection is unknown.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted to investigate the immune memory responses of H7N9 patients who contracted the disease and survived during the 2013-2016 epidemics in China. Sustainability of antibodies and T-cell memory to H7N9 virus were examined. Healthy subjects receiving routine medical examination in physical examination center were recruited as control.

Results:

A total of 75 survivors were enrolled and classified into four groups based on the time elapsed from illness onset to specimen collection: three months (n=14), 14 months (n=14), 26 months (n=28), and 36 months (n=19). Approximately 36 months after infection, the geometric mean titers of virus-specific antibodies were significantly lower than titers in patients of three months after infection, but 16 of 19 (84.2%) survivors in the 36-month interval had microneutralization (MN) titer ≥ 40. Despite the overall declining trend, the percentages of virus-specific cytokines-secreting memory CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells remained higher in survivors at nearly all time points in comparison with control subjects. Linear regression analysis showed that severe disease (mean titer ratio 2.77, 95%CI 1.17-6.49) was associated with higher hemagglutination inhibition (HI) titer, and female sex for both HI (1.92, 1.02-3.57) and MN (3.33, 1.26-9.09) antibody, whereas female sex (mean percentage ratio 1.69, 95%CI 1.08-2.63), underlying medical conditions (1.94, 95%CI 1.09-3.46), and lack of antiviral therapy (2.08, 95%CI 1.04-4.17) were predictors for higher T-cell responses.

Conclusions:

Survivors from H7N9 virus infection produced long-term antibodies and memory T-cells responses. Our findings warrant further serological investigation in general and high-risk populations and have important implications for vaccine design and development.

Keywords: Influenza, H7N9, Antibodies, Immune Memory, T-Cells, Survivors

Introduction

The avian influenza A(H7N9) virus has caused five epidemic waves and spread to nearly all provinces of China since early 2013. As of January 18, 2019, a total of 1564 human cases, including 610 deaths, had been reported, with a case fatality rate about 39% [1]. The infection of virulent mutants of the H7N9 virus in both chickens and humans has been documented [2]. Limited person-to-person transmission between unrelated individuals in hospital settings further exemplifies the increasing threat of the virus to humans [3–5]. In addition, the H7N9 virus has the highest risk score among the 12 novel influenza A viruses, with moderate to high pandemic potential [6].

The importance of sustaining protective humoral immunity is widely recognized [7,8]. Although H7N9-specific antibody responses were identified in patients during acute and convalescent phases and was associated with disease severity [9–11], whether the antibody responses can persist for a long time remains unclear. In addition, cellular immune responses are known to protect against various viral infections [12] and play a key role in protection against symptomatic pandemic influenza [13–15]. Previous studies have shown that disease severity was associated with the antigen-presenting capacity of monocytes and with delayed T cell responses in H7N9 patients [16, 17], and patients who had prolonged hospitalization or died had delayed recruitment of CD8+/CD4+ T-cells [18]. Cellular memory responses to vaccination or infection with the 2009 pandemic H1N1 (pdmH1N1) can maintain at a quite high level one year after antigen encounter [19]. However, the profile of memory T-cell responses to the H7N9 virus years after the natural infection has not been investigated.

We conducted a cross-sectional study to delineate the temporal trend of antibody and memory T-cell responses in H7N9 survivors. Additionally, we examined the relationship between clinical outcomes and virus-specific immune responses.

Material and Methods

Study design

During March 1 to June 1, 2016, laboratory-confirmed H7N9 patients who were reported during the first four epidemic waves (2013-2016) and recovered from the disease were recruited by phone from Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and Shandong Provinces of China. Healthy individuals who lived in Inner Mongolian (where no H7N9 virus was detected), had no close contact with live poultry or live poultry markets during the previous 12 months, and had no known diseases or conditions that could have compromised their immune systems were also recruited from the people receiving routine medical examination in local physical examination center as controls. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the review board of the Academy of Military Medical Sciences in Beijing, China.

Data collection and sampling

Consented subjects completed a questionnaire at enrollment to provide information on demographic and clinical manifestation data, exposures to poultry in the recent two weeks, vaccination history of seasonal influenza, and experience of influenza-like illness in the recent two weeks. Blood samples were collected to separate serum and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs).

Serological assays

Serum hemagglutination inhibition (HI), neuraminidase inhibition (NI), microneutralization (MN), and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay measuring H7 hemagglutinin-specific IgG antibodies were performed as described in our previous study [20]. A H7N9 virus (A/Jiangsu/Wuxi05/2013) and a genetic reassortant H6N9 virus were used for detection of HI, MN, and NI antibodies as described in our previous study [20].

Flow cytometry assay

The PBMCs were stimulated with RPMI medium (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) as the negative control, monensin (BD Biosciences) as the positive control, or live H7N9 virus (A/Jiangsu/Wuxi05/2013) for 1 hour. After that, 10% fetal bovine serum was added into the cultures and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 3 hours, and the cells were incubated for an additional 18 hours with the GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences, 1:2000 dilution). Cells were stained for surface markers and intracellular cytokines with at least 1 × 106 live cells for each sample. Data were obtained using the BD LSR Fortessa (BD Biosciences, Oxford, UK) machine and analyzed using FlowJo software Version 10 (Tree Star Inc).

Statistics analysis

Categorical and continues variables were analyzed using χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test or Student’s t-test where appropriate. We used the Kruskal-Wallis test to compare the difference in antibody titers and percentages of virus-specific cell responses between survivors of each epidemic wave and control subjects. Nonparametric Spearman’s test was performed for correlation analysis. Linear regression was used to assess potential predictors for log-transformed antibody and T-cell responses, with a stepwise procedure based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) for predictor selection. Covariate effects are presented as exponentiated regression coefficients, i.e., ratio of geometric mean responses. A two-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted with the R and GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Further details concerning sample processing, serological and flow cytometry assays, and regression analyses are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Results

Study participants’ characteristics

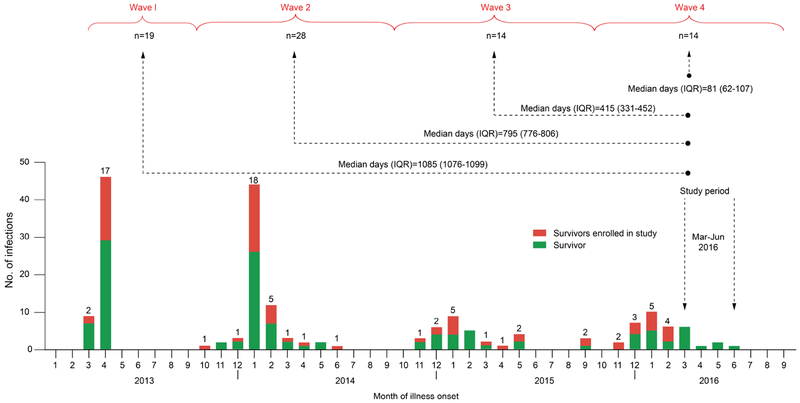

Of 193 laboratory-confirmed H7N9 patients who recovered from the disease in Zhejiang, Jiangsu and Shandong Provinces, China (Figure 1), 75 were enrolled into this study (Supplementary Table S1). Among these 75 survivors, 19 were infected during Wave 1, 28 during Wave 2, 14 during Wave 3, and 14 during Wave 4. The median duration (interquartile range) from symptom onset to enrollment was 1085 (1076-1099), 795 (776-806), 415 (331-452), and 81 (62-107) days for patients of epidemic waves 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. A total of 17 healthy subjects were recruited from the Inner Mongolian of China to serve as controls. There was no statistically significant difference among patients across the four waves regarding demographic and clinical characteristics or between patients and controls regarding demographics except that controls were notably younger and tended to be more often vaccinated than patients (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 1. Diagram of study population.

Temporal distribution of laboratory-confirmed human cases of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus infection in Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and Shandong Provinces, China, during the first four epidemic waves is shown by month. The monthly numbers of H7N9 survivors (defined by symptom onset month) enrolled in the present study from each Wave (Wave 1: February-September 2013, Wave 2: October 2013-September 2014, Wave 2: October 2014-September 2015, Wave 4: October 2015-September 2016) are shown in red, together with non-enrolled survivors (in green). Arrows between study enrollment and each Wave represent the median duration (interquartile range, IQR) of days from illness onset to enrollment collection of blood samples. The number of enrolled patients is shown by month (on the top of each bar) and by epidemic Wave (under each curly bracket).

Virus-specific antibody response in survivors

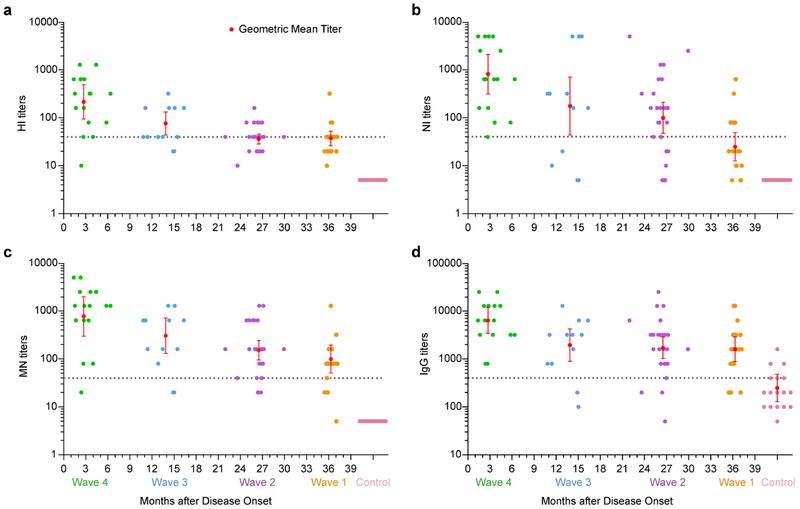

Figure 2 shows the geometric mean titers (GMTs) (Supplementary Table S3) and individual titers of antibodies from Wave 4 to Wave 1. At approximately three months after infection, HI, NI, MN, and IgG antibodies were detectable in all 14 patients of Wave 4, with the GMTs of 215 (95% confidence interval [CI] 94-492), 820 (95%CI 313-2147), 780 (95%CI 299-2038), and 6400 (95%CI 3416-11992), respectively. One patient had a titer <40 for both HI and MN antibodies, whereas all 14 patients had NI and IgG antibody titers ≥40 or ≥400. About 14 months after infection, the GMTs of HI (76, 95%CI 43.7-132.5), NI (176, 95%CI 43.8-712.1), MN (305, 95%CI 129.9-714), and IgG (1950, 95%CI, 897.8-4237) antibodies decreased in patients of Wave 3, and 12 (85.7%), 10 (71.4%), 12 (85.7%), and 12 (85.7%) of 14 patients had antibodies titers ≥ 40, respectively. Only one patient had a NI antibody titer <10. About 26 months after infection, lower antibody levels were shown by patients infected in Wave 2, and the GMT of HI antibody dropped to near 40. Two patients had NI antibody titers <10. At roughly 36 months after infection, HI antibody levels were ≥40 in 68% of patients of Wave 1. However, 84.2% of patients still had MN and IgG titers above 40 and 400, respectively. One patient became negative for NI antibody, and another patient had a titer <10 for both HI and MN antibodies. The HI, NI, MN, and IgG antibody titers were highly correlated with each other regardless of epidemic waves (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 2. Antibody responses to influenza A(H7N9) virus in survivors from Wave 1 to Wave 4.

(a-d) The geometric mean titers (red dashed line) are shown for the Serum hemagglutination inhibition (HI), neuraminidase inhibition (NI), microneutralization (MN) and IgG antibodies. Vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Each dot represents the titer for an individual. Gray dashed line indicates titer= 40 for HI, NI and MN antibodies, and 400 for IgG antibody. Undetectable antibody titers are replaced by an arbitrary value of 5 (HI, NI and MN) or 25 (IgG) to allow for the calculation of the geometric mean titer.

Virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in survivors

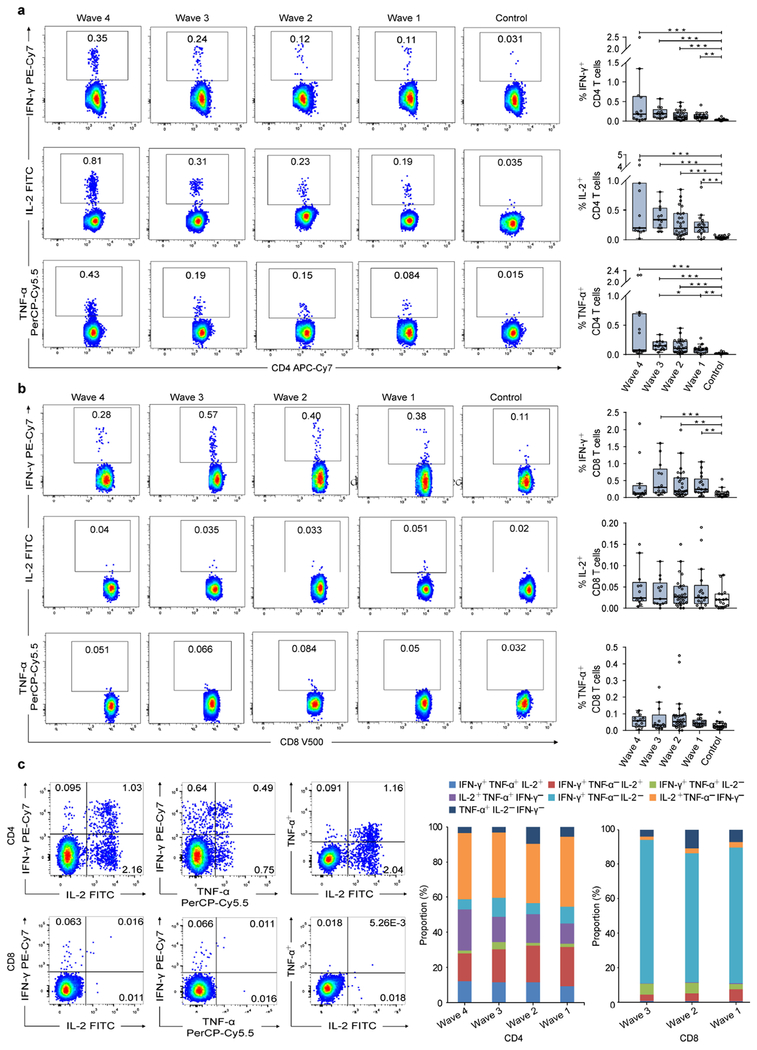

We first assessed the percentages of H7N9-specific gamma interferon-positive (IFN-γ+), interleukin-2-positive (IL-2+), and tumor necrosis factor alpha-positive (TNF-α+) T-cells. Overall, very few virus-specific IFN-γ+ (0.036±0.027), IL-2+ (0.041±0.026), and TNF-α+ (0.022±0.014) CD4+ T-cells were detected in controls, whereas patients had a high percentage of virus-specific CD4+ T-cells (Figure 3a). We observed a declining trend of the virus-specific CD4+ T-cell response in patients from Wave 4 to Wave 1. However, the patients infected in Wave 1 still maintained a much higher percentage of virus-specific CD4+ T-cells at approximately 36 months after infection in comparison to the controls (p< 0.01; Figure 3a).

Figure 3. PBMC-derived H7N9 virus-specific T-cells responses in H7N9 survivors.

(a, b) The representative FACS plots of IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α expression on virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ from a representative subject (left) and the percentage of virus-specific IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α secreting CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells in H7N9 survivors of each Wave (right). (c) The representative FACS plots of double positive cytokine-secreting CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells from a representative subject (Left) and the proportions of triple-positive (IFN-γ+IL-2+TNF-α+), double-positive (IFN-γ+IL-2+TNF-α-, IFN-γ+IL-2-TNF-α+ or IFN-γ-IL-2+TNF-α+), and single-positive (IFN-γ+IL-2-TNF-α-, IFN-γ-IL-2+TNF-α- or IFN-γ-IL-2-TNF-α+) cytokine-secreting CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells in survivors of each Wave (right). Proportions of CD8+ T-cells are not shown for Wave 4 as patients did not differ from controls in virus-specific CD8+ T-cells. In the box plots, the box represents the third quartile (75%) and first quartile (25%), with the horizontal line indicating the median (50%). The whiskers represent 1.5 times the IQR, with outliers shown. Each circle represents the percentage of cellular responses for an individual. The p values were determined by Kruskal-Wallis Test for comparing the differences across the waves and the control group. The p values reported are for descriptive purposes only and were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

Regarding the CD8+ T-cell responses, the percentage of virus-specific IFN-γ+ CD8+ T-cells in patients infected during Waves 1-3 were significantly higher than that in controls, but no significant difference was observed for patients of Wave 4 (Figure 3b). However, both patients and controls had very low levels of IL-2+ and TNF-α+ CD8+ T-cell responses. Further analysis showed that the H7N9-specific CD4+ T-cells were multifunctional because about half of these T-cells secreted triple and double-positive cytokines, whereas the CD8+ T-cells in patients of Wave 1-3 were predominantly IFN-γ-expressing cells (Figure 3c).

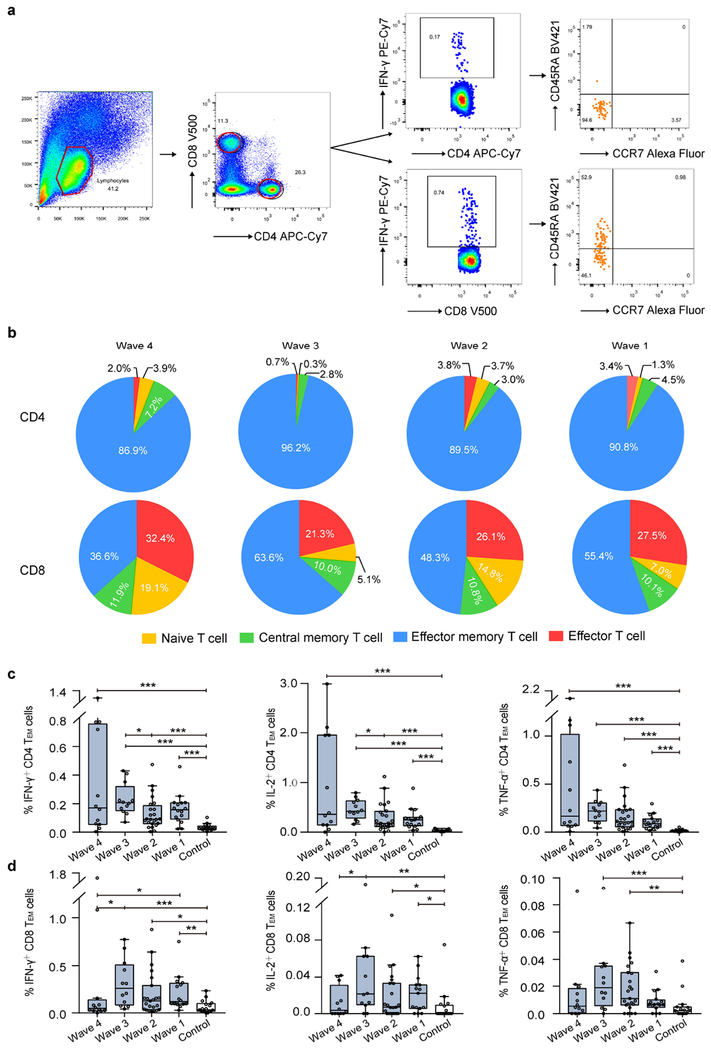

Phenotypic memory of virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in survivors

The H7N9-specific IFN-γ+ CD4+ T-cells were phenotypically effector memory CD45RA-CCR7- cells (Figure 4a) which account for around 90% of this T-cell population in patients of each wave (Figure 4b). The proportions of effector memory CD45RA-CCR7- cells were similar for IL-2+ and TNF-α+ CD4+ T-cells (Supplementary Figure S2). In contrast, H7N9-specific IFN-γ+ CD8+ T-cell populations included a substantial proportion (21.3%-32.4% across waves) of effector memory CD45RA+CCR7- cells in addition to effector CD45RA-CCR7- cells. The percentages of virus-specific IFN-γ+, IL-2+, and TNF-α+ effector memory CD4+ T-cells tended to decline with time but were higher in patients than in the control group (p< 0.001; Figure 4c). Relatively high percentages of IFN-γ+ effector memory CD8+ T-cells were detected among patients in Waves 1-3, significantly higher than controls (p< 0.01). Although percentages of IL-2+ and TNF-α+ effector memory CD8+ T-cells were generally low in patients, those in patients of Waves 1-3 were still significantly higher than those in the controls (Figure 4d).

Figure 4. Phenotypic memory of virus-specific T-cells in Survivors.

Phenotypic memory (naϊve, CD45RA+CCR7+; central memory, CD45RA-CCR7+; effector memory, CD45RA-CCR7-; and late effector, CD45RA+CCR7-) analysis of virus-specific cytokines-secretin CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells. (a) The representative FACS analytic process of CD45RA and CCR7 expression on virus-specific IFN-γ secreting CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells. (b) The constitution ratio of naϊve, central memory, effect memory, and late effect T-cells on virus-specific IFN-γ secreting CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells in survivors of each Wave. Data on control subjects were not shown due to few virus-specific cytokine-secreting T-cells was detected. (c and d) The percentage of virus-specific effector memory T-cells in CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells in survivors of each Wave. In the box plots, the box represents the third quartile (75%) and first quartile (25%), with the horizontal line representing the median (50%). The whiskers represent 1.5 times the IQR, with outliers shown. Each circle represents the percentage of cellular responses for an individual. The p values were estimated by Kruskal-Wallis Test for comparing the differences across waves and the control group. The p values reported are for descriptive purposes only and were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

Association between potential factors and immune response

Linear regression analysis of potential factors affecting antibody titers or T-cell response revealed that male patients tended to have lower HI and MN antibody titers on average than female patients, with GMT ratios of 0.52 (95%CI 0.28-0.98) and 0.30 (95%CI 0.11-0.79), respectively (Table 1). In addition, patients with severe infections had significantly higher titer of HI (GMT ratios 2.77, 95%CI 1.17-6.49) antibody than those with mild infections. Regarding the T-cell responses, underlying medical conditions was a predictor for higher percentage of both H7N9-specific IL-2+ (geometric mean percentage ratio 1.94, 95%CI 1.09-3.46) and TNF-α+ (1.69, 95%CI 0.99-2.86) CD4+ T-cell response, and antiviral therapy for lower percentage of virus-specific IL-2+ CD4+ T-cell responses (0.48, 95%CI 0.24-0.96). Male patients had a lower percentage of IL-2+ CD8+ T-cell response than female patients (0.59, 95%CI 0.38-0.92).

Table 1.

Effects of potential factors affecting antibodies and T cell response.

| Immune response, predictor | Ratio* (95%CI) |

|---|---|

| HI | |

| Gender | |

| Male (n=49) | 0.52 (0.28-0.98) |

| Female (n=26) | Reference |

| Disease severity | |

| Severe (n=64) | 2.77 (1.17-6.49) |

| Mild (n=11) | Reference |

| MN | |

| Gender | |

| Male (n=49) | 0.30 (0.11-0.79) |

| Female (n=26) | Reference |

| Disease severity | |

| Severe (n=64) | 3.32 (0.89-12.43) |

| Mild (n=11) | Reference |

| IL-2+ CD4 | |

| Chronic disease | |

| Yes (n=51) | 1.94 (1.09-3.46) |

| No (n=24) | Reference |

| Antiviral therapy | |

| Yes (n=63) | 0.48 (0.24-0.96) |

| No (n=12) | Reference |

| IL-2+ CD8 | |

| Gender | |

| Male (n=49) | 0.59 (0.38-0.92) |

| Female (n=26) | Reference |

CI confidence interval, HI hemagglutination inhibition, MN microneutralizing.

geometric mean titer ratios for antibody responses and geometric mean percentage ratios for T-cell responses. Significant wave differences are not shown

Discussion

In this study, we identified the levels of virus-specific antibody and memory T-cell responses among H7N9 survivors after natural infection. We found that, although virus-specific antibodies and polyfunctional virus-specific T-cell responses to the H7N9 virus waned over time, most survivors maintained detectable antibody titers and a high level of virus-specific T-cell responses at about 36 months after infection.

Previous studies have shown that HI antibodies induced by natural infection with the pdmH1N1 virus persisted at constant high titers (>1:40) for at least 15 months [21], and that the HI and MN antibodies against the H5N1 virus infection lasted even longer, at stable titers (≥1:40) for nearly 5 years [22]. Our study showed that the H7N9 virus infection was also able to induce long-term presence of antibodies in most patients. We observed a decline in HI titer among survivors from Wave 4 to Wave 1 (representing shorter to longer times after infection), and over 60% survivors of Wave 1 maintained HI titers ≥40 at about three years after infection. The NI antibody level decreased more rapidly, and only about 30% survivors in Wave 1 maintained titers ≥40 three years post infection. Evidence for the contribution of NA antibody to the protection against seasonal influenza, independent of the effect of HA antibody, has been suggested by patterns of infection during the 1968 pandemic and more recently using multivariable regression analyses [23–25]. Given the ephemerality of NI titers observed here in comparison with HI titers, natural infection or vaccine-induced response to NA might have short duration of protection even when HA drifts and NA does not. On the other hand, we observed a relatively slow decline in MN and IgG titers over time. Based on the protective effect of MN observed for seasonal influenza, if MN antibody is indeed a better correlate for protection than HI antibody and if a titer of ≥40 is associated with 50% protection against infection [26–28], we could anticipate that a proportion of H7N9 survivors would remain protected against the H7N9 virus at about 36 months after the initial infection, but has not been proven so.

We identified high levels of T-cell responses in most survivors even three years after infection. The H7N9-specific cytokines-secreting CD4+ T-cells were polyfunctional and CD45RA-CCR7- effector memory CD4+ T-cells were dominant. In contrast, the H7N9-specific CD8+ T-cells seemed to be mostly single functional of IFN-γ secreting and comprised of predominantly CD45RA-CCR7- effector-memory and CD45RA+CCR7- effector T-cells. However, we observed a delayed IFN-γ+ CD8+ T-cell response in patients of Wave 4 that the IFN-γ+ CD8 T-cells remained at a low level at about 3 months after infection, which is similar to our previous study [29] and suggests a prolonged impairment of immune responses after recovery [17, 29]. Because of conserved T-cell epitopes shared between H7N9 and seasonal influenza viruses, cross-reactivity between the two viruses cannot be ruled out [30–33]. Therefore, the T-cell responses measured in our study might be derived from both H7N9 and seasonal influenza encounters. However, H7N9-specific responses are likely to be dominant because very few T-cell responses to H7N9 virus were detected in the controls.

We found that severe illness led to a stronger HI antibody response compared to mild illness. This difference was also observed between severely ill patients admitted to intensive care units or presenting acute respiratory distress syndrome and patients with mild disease [29]. Moreover, female patients had a stronger HI and MN antibody responses than male patients. It has been shown in animal models that, after infection with the H7N9 virus, female mice had significantly higher morbidity with increased inflammatory host responses [34]. However, a large gap still exists in our understanding about how sex influences immune responses to influenza infection, which needs further studies. A previous study has shown that H7N9-specific T-cell memory was prolonged in older and severe patients [29], but no such association was observed in the current study. We found that underlying medical conditions and antiviral therapy, and female sex were associated with higher virus-specific T-cell responses. However, the underlying biological mechanisms remain to be elucidated.

The current study had several limitations. Firstly, this is a cross-sectional rather than longitudinal study. The lack of serial blood samples from same patients has limited our ability to quantify the heterogeneity in the individual trend of immune responses to the H7N9 virus. For instance, our previous study on a longitudinal cohort of H7N9 survivors from the fifth wave showed that 36.4% of the survivors had HI titers ≥40 at 300 days, in contrast to 85.7% at about 14 months after infection among patients from the third wave in the current study [20]. Secondly, blood samples of H7N9 patients during the acute phase were not collected, creating a gap in the understanding of the dynamic changes of antibody and T-cells response to the H7N9 virus over time. Thirdly, the controls are younger age and more frequent vaccination of seasonal influenza, which might be confounding factors influencing the virus-specific T-cell response.

In summary, our study suggests that virus-specific antibody and memory T-cell responses can be detected in H7N9 patients three years after natural infection, which may imply partial protection against subsequent H7N9 infections. Our findings could inform the design of future serological studies and the development of H7N9-targeting vaccines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients for their participation in the study and the staff of the local CDCs whose collaboration for sampling made this study possible.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (81773494, 81402730, 81621005, and 81401312), the Beijing Science and Technology Nova program (Z171100001117088); China Mega-Project on Infectious Disease Prevention (2017ZX10303401-006 and 2016ZX10004222-003), the Zhejiang Province Major Science and Technology Program (2014C03039), US NIH/National Institute of General Medical Sciences (U54-GM111274) and NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R37-AI32042-19).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Transparency declaration

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Chinese National Influenza Center, Chinese Influenza Weekly Report, 2017. www.chinaivdc.cn/cnic/en/Surveinance/WeeklyReport/201711/P020171107473615189687.pdf. (Accessed November 7 2017).

- [2].Ma MJ, Yang Y, Fang LQ. Highly Pathogenic Avian H7N9 Influenza Viruses: Recent Challenges. Trends Microbiol 2019;27:93–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fang CF, Ma MJ, Zhan BD, Lai SM, Hu Y, Yang XX, et al. Nosocomial transmission of avian influenza A (H7N9) virus in China: epidemiological investigation. BMJ 2015;351:h5765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chen H, Liu S, Liu J, Chai C, Mao H, Yu Z, et al. Nosocomial Co-Transmission of Avian Influenza A(H7N9) and A(H1N1)pdm09 Viruses between 2 Patients with Hematologic Disorders. Emerg Infect Dis 2016;22:598–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Farooqui A, Liu W, Zeng T, Liu Y, Zhang L, Khan A, et al. Probable Hospital Cluster of H7N9 Influenza Infection. N Engl J Med 2016;374:596–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Burke SA, Trock SC. Use of Influenza Risk Assessment Tool for Prepandemic Preparedness. Emerg Infect Dis 2018;24:471–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dorner T, Radbruch A. Antibodies and B cell memory in viral immunity. Immunity 2007;27:384–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Amanna IJ, Carlson NE, Slifka MK. Duration of humoral immunity to common viral and vaccine antigens. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1903–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Guo L, Zhang X, Ren L, Yu X, Chen L, Zhou H, et al. Human antibody responses to avian influenza A(H7N9) virus, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis 2014;20:192–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhang A, Huang Y, Tian D, Lau EH, Wan Y, Liu X, et al. Kinetics of serological responses in influenza A(H7N9)-infected patients correlate with clinical outcome in China, 2013. Euro Surveill 2013;18:20657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Huang R, Zhang L, Gu Q, Zhou YH, Hao Y, Zhang K, et al. Profiles of acute cytokine and antibody responses in patients infected with avian influenza A H7N9. PLoS One 2014;9:e101788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ahmed R, Gray D. Immunological memory and protective immunity: understanding their relation. Science 1996;272:54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Greenbaum JA, Kotturi MF, Kim Y, Oseroff C, Vaughan K, Salimi N, et al. Pre-existing immunity against swine-origin H1N1 influenza viruses in the general human population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:20365–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sridhar S, Begom S, Bermingham A, Hoschler K, Adamson W, Carman W, et al. Cellular immune correlates of protection against symptomatic pandemic influenza. Nat Med 2013;19:1305–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tan S, Zhang S, Wu B, Zhao Y, Zhang W, Han M, et al. Hemagglutinin-specific CD4(+) T-cell responses following 2009-pH1N1 inactivated split-vaccine inoculation in humans. Vaccine 2017;35:5644–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Diao H, Cui G, Wei Y, Chen J, Zuo J, Cao H, et al. Severe H7N9 infection is associated with decreased antigen-presenting capacity of CD14+ cells. PLoS One 2014;9:e92823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chen J, Cui G, Lu C, Ding Y, Gao H, Zhu Y, et al. Severe Infection With Avian Influenza A Virus is Associated With Delayed Immune Recovery in Survivors. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wang Z, Wan Y, Qiu C, Quinones-Parra S, Zhu Z, Loh L, et al. Recovery from severe H7N9 disease is associated with diverse response mechanisms dominated by CD8(+) T cells. Nat Commun 2015;6:6833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bonduelle O, Carrat F, Luyt CE, Leport C, Mosnier A, Benhabiles N, et al. Characterization of pandemic influenza immune memory signature after vaccination or infection. J Clin Invest 2014;124:3129–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ma MJ, Liu C, Wu MN, Zhao T, Wang GL, Yang Y, et al. Influenza A(H7N9) Virus Antibody Responses in Survivors 1 Year after Infection, China, 2017. Emerg Infect Dis 2018;24:663–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sridhar S, Begom S, Hoschler K, Bermingham A, Adamson W, Carman W, et al. Longevity and determinants of protective humoral immunity after pandemic influenza infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:325–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kitphati R, Pooruk P, Lerdsamran H, Poosuwan S, Louisirirotchanakul S, Auewarakul P, et al. Kinetics and longevity of antibody response to influenza A H5N1 virus infection in humans. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2009;16:978–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Couch RB, Atmar RL, Franco LM, Quarles JM, Wells J, Arden N, et al. Antibody correlates and predictors of immunity to naturally occurring influenza in humans and the importance of antibody to the neuraminidase. J Infect Dis 2013;207:974–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Monto AS, Petrie JG, Cross RT, Johnson E, Liu M, Zhong W, et al. Antibody to Influenza Virus Neuraminidase: An Independent Correlate of Protection. J Infect Dis 2015;212:1191–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Monto AS, Kendal AP. Effect of neuraminidase antibody on Hong Kong influenza. Lancet 1973;1:623–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hobson D, Curry RL, Beare AS, Ward-Gardner A. The role of serum haemagglutination-inhibiting antibody in protection against challenge infection with influenza A2 and B viruses. J Hyg (Lond) 1972;70:767–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hannoun C, Megas F, Piercy J. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of influenza vaccination. Virus Res 2004;103:133–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Coudeville L, Bailleux F, Riche B, Megas F, Andre P, Ecochard R. Relationship between haemagglutination-inhibiting antibody titres and clinical protection against influenza: development and application of a bayesian random-effects model. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zhao M, Chen J, Tan S, Dong T, Jiang H, Zheng J, et al. Prolonged Evolution of Virus-Specific Memory T Cell Immunity after Severe Avian Influenza A (H7N9) Virus Infection. J Virol 2018;92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Quinones-Parra S, Grant E, Loh L, Nguyen TH, Campbell KA, Tong SY, et al. Preexisting CD8+ T-cell immunity to the H7N9 influenza A virus varies across ethnicities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:1049–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Richards KA, Nayak J, Chaves FA, DiPiazza A, Knowlden ZA, Alam S, et al. Seasonal Influenza Can Poise Hosts for CD4 T-Cell Immunity to H7N9 Avian Influenza. J Infect Dis 2015;212:86–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].van de Sandt CE, Kreijtz JH, de Mutsert G, Geelhoed-Mieras MM, Hillaire ML, Vogelzang-van Trierum SE, et al. Human cytotoxic T lymphocytes directed to seasonal influenza A viruses cross-react with the newly emerging H7N9 virus. J Virol 2014;88:1684–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Liu WJ, Tan S, Zhao M, Quan C, Bi Y, Wu Y, et al. Cross-immunity Against Avian Influenza A(H7N9) Virus in the Healthy Population Is Affected by Antigenicity-Dependent Substitutions. J Infect Dis 2016;214:1937–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hoffmann J, Otte A, Thiele S, Lotter H, Shu Y, Gabriel G. Sex differences in H7N9 influenza A virus pathogenesis. Vaccine 2015;33:6949–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.