Abstract

Reproduction and energy balance are inextricably linked in order to optimize the evolutionary fitness of an organism. With insufficient or excessive energy stores a female is liable to suffer complications during pregnancy and produce unhealthy or obesity-prone offspring. The quintessential function of the hypothalamus is to act as a bridge between the endocrine and nervous systems, coordinating fertility and autonomic functions. Across the female reproductive cycle various motivations wax and wane, following levels of ovarian hormones. Estrogens, more specifically 17β-estradiol (E2), coordinate a triumvirate of hypothalamic neurons within the arcuate nucleus (ARH) that govern the physiological underpinnings of these behavioral dynamics. Arising from a common progenitor pool of cells, this triumvirate is composed of the kisspeptin (Kiss1ARH), proopiomelanocortin (POMC), and neuropeptide Y/agouti-related peptide (AgRP) neurons. Although the excitability of these neuronal subpopulations is subject to genomic and rapid estrogenic regulation, kisspeptin neurons are the most sensitive, reflecting their integral function in female fertility. Based on the premise that E2 coordinates autonomic functions around reproduction, we will review the recent findings on the synaptic interactions between Kiss1, AgRP and POMC neurons and how the rapid membrane-initiated and intracellular signaling cascades activated by E2 in these neurons are critical for control of homeostatic functions supporting reproduction.

Keywords: Hypothalamus, synaptic transmission, peptides, kisspeptin neurons, proopiomelanocortin neurons, neuropeptide Y/agouti-related peptide neurons

1. 17 β-Estradiol and reproduction

The hypothalamus regulates both puberty and fertility through secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from neurons located primarily in the preoptic area in rodents [1] but extending caudally into the basal hypothalamus in sheep [2], guinea pigs [3], and primates including humans [4, 5]. GnRH stimulates the release of gonadotropins from the pituitary gland, controlling ovulation in females. This process is not linear, but rather relies on appropriately-timed GnRH pulses preceding a final surge to elicit luteinizing hormone (LH) release. Ovarian hormones are required for both negative and positive feedback actions that maintain a normal cycle. Classical estrogenic signaling is mediated by ERα [6, 7] and ERβ [8] receptors located in the cytosol which, upon binding E2, dimerize and enter the nucleus. These ERs interact with estrogen response elements (EREs) located within certain gene promotors to regulate transcription [9-11]. In addition, E2 may activate membrane-bound estrogen receptors (mERs) to mediate rapid, non-genomic actions [12, 13]. mERs can take the form of ERα/β [14, 15], G-protein coupled estrogen receptor (GPER1) [16-19], or an unidentified Gq-coupled receptor (Gq-mER) [20, 21]. However, GnRH neurons lack ERα [22, 23] suggesting the involvement of an extrinsic pulse generator or other estrogen signaling pathways (e.g. ERβ, GPER1, Gq-mER) [24, 25].

Neurons in the anteroventral periventricular (AVPV) and more caudal preoptic periventricular nucleus (PeN) co-express kisspeptin, a neuropeptide encoded by the Kissl gene, GABA [26], and tyrosine hydroxylase [27], Kisspeptin-54 is the endogenous ligand of G protein-coupled receptor 54 (GPR54, aka Kissl R) [28]. GPR54 is highly expressed in GnRH neurons [29], and mutations in GPR54 cause autosomal recessive idiopathic hypogonadism in humans and deletion of GPR54 or Kiss1 in mice results in defective sexual development and reproductive failure [30, 31]. Centrally administered kisspeptin robustly stimulates GnRH and gonadotropin secretion in both pre-pubertal and adult animals [32,33]. In vitro kisspeptin robustly excites GnRH neurons [34], and based on cell signaling studies, kisspeptin excites GnRH neurons primarily through activation of canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC) channels and to a lesser extent through inhibition of inwardly rectifying K+ channels [35-39].

The AVPV/PeN expresses high levels of ERα and ERβ, and the actions of the gonadal steroids on kisspeptin neurons are mediated, at least in part, via nuclear-initiated signaling (transcriptional) mechanisms [22, 40, 41], Kiss1 mRNA expression is increased in the AVPV/PeN following E2 treatment, while decreased in the more caudally located arcuate nucleus [42]. Importantly, endogenous currents involved in regulating neuronal excitability, including h-, T-type calcium and a persistent sodium current (lNaP), are all expressed in AVPV/PeN Kiss1 (Kiss1AVPV/PeN) neurons, and both currents and corresponding ion channels are highly upregulated by proestrus levels of E2 [43-46]. These findings combined with previous observations that lesions of or implants of ER antagonists into the AVPV/PeN in rodents abrogate the positive feedback effects of E2 [47-50] have led to the hypothesis that E2 acts on Kiss1AVPV/PeN neurons to induce positive feedback on GnRH and LH secretion. Finally, more recent experiments have shown that high frequency optogenetic stimulation of Kiss1AVPV/PeN neurons releases kisspeptin that excites (depolarizes) GnRH neurons through activation of TRPC channels [51].

2. Links between reproduction and energy homeostasis

Kiss1ARH, POMC and AgRP neurons arise from a common precursor [52, 53] and together these neurons govern both reproduction and energy homeostasis. The ARH stands well-positioned at the “headwaters” of the natural reward circuit. By virtue of close apposition to the median eminence, a circumventricular organ, ARH neurons act as first-order neurons, able to sense and respond to indicators of the energy state of the animal [54, 55]. ERs are densely expressed in this region [56-58], granting ARH neurons sensitivity to circulating steroid hormones. The ARH was also proposed to be the center of the GnRH “pulse generator” based on in vivo recordings of multi-unit activity [59-62]. More recently Kiss1ARH neurons have been identified as the source of this patterned activity [51, 63, 64]. Furthermore, the cellular underpinnings of synchronization, a network of reciprocal connections between Kiss1ARH neurons, has been elucidated [51]. When E2 levels are low, Kiss1ARH neurons produce and co-release the neuropeptides neurokinin B (NKB) and dynorphin. Through a network of reciprocal connections, Kiss1ARH neurons excite each other through NKB release. Dynorphin then presynaptically inhibits further release [51]. This sequence of events repeats, giving rise to synchronized oscillations in activity. As E2 rises in preparation of ovulation, mRNA expression of the peptide neurotransmitters NKB, dynorphin, and kisspeptin falls [42, 64, 65] with glutamate emerging as the dominant neurotransmitter [66]. This progression from peptidergic to amino acid transmission affects not just synapses with Kiss1ARH and Kiss1AVPV/PeN neurons, but two antagonistic ARH cell types (see below).

Neuropeptide Y/agouti related peptide (AgRP) neurons are considered orexigenic with their activation instigating robust food consumption within minutes, regardless of the energy state of the animal [67-70]. AgRP neurons do not synapse on GnRH neurons, but AgRP neurons synapse on Kiss1 neurons and inhibit their activity via GABA release [71]. Ablation of AgRP neurons markedly decreases presynaptic inhibition of Kiss1 projections [71] and fasting reduces fertility and expression of Kissl in the ARH [72]. The opposing, anorexigenic POMC neurons decrease food intake with sustained stimulation [67, 73, 74] and, in addition to GABA [75, 76] and glutamate [75], release a diverse complement of neuropeptides. The POMC precursor peptide is processed to produce α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH, excitatory) [77] and β-endorphin (inhibitory) [78]. GnRH neurons receive POMC inputs and are hyperpolarized by the μ-opioid receptor agonist DAMGO ([D-Ala2, N-Me-Phe4, Gly5-ol]-enkephalin) through activation of a K+ conductance [79-82]. Naloxone block of opioid signaling stimulates GnRH release [83-87] and increases LH production [88, 89]. This would suggest POMC signaling inhibits GnRH activity [90]. Therefore, excess opioid tone is inhibitory to reproductive function. However, selective activation of the α-MSH pathway can be stimulatory [90]. More straightforward are Kiss1 to POMC projections. Kisspeptin administered icv reduces food intake [91], optogenetic stimulation of Kiss1ARH neurons elicits glutamatergic excitation [66, 92], and kisspeptin depolarizes POMC neurons [93]. Though POMC neurons make reciprocal projections to Kissl neurons, these circuits are poorly understood [66, 90, 94, 95]. Perhaps POMC signaling uses Kiss1 neurons as an intermediary with GnRH neurons considering a subpopulation of Kiss1AVPV/PeN neurons expresses melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R) [26]. Blockade of melanocortin signaling in peripubertal females selectively decreases Kiss1 mRNA expression in the Kiss1AVPV/PeN neurons, and while MC4R knockout mice can reproduce, they are subfertile [96]. Overexpression of AgRP, an inverse agonist for MCRs, causes infertility [90, 97, 98]. Therefore, while the content and functional significance of POMC inputs to Kiss1 neurons remains unclear, AgRP neurons unmistakably act to inhibit reproduction during an energy deficit [71].

AgRP and POMC neurons are inversely regulated by glucose and metabolic hormones including leptin and insulin [99-101]. The involvement of ARH neurons in reproduction is predictable since pregnancy is metabolically demanding. A lack of sufficient energy stores increases the risk of miscarriage in underweight females [102], and women suffering from anorexia often display amenorrhea [103-105]. Leptin, a hormone produced by white adipocytes [106], signals the total body energy stores. Mutations in leptin production and signaling result in an infertile, obese phenotype [107, 108]; however, GnRH neurons lack leptin receptors [109, 110]. As this phenotype can be reversed by ablating AgRP neurons [97], leptin regulation of GnRH neurons is potentially indirect. Kiss1ARH neurons express leptin receptors [111, 112], and like with POMC neurons, leptin depolarizes and increase their firing [99, 112]. Without the hyperpolarizing influence of leptin [113], AgRP neurons become highly active, inhibiting Kiss1ARH and Kiss1AVPV/PeN neurons (Figure 1) [71]. In lean mice overexpression or injection of leptin accelerates puberty onset [114, 115], and obesity is associated with precocious puberty in women [116, 117]. Therefore, leptin levels and by proxy, adiposity affects not just fertility but pubertal development.

Figure 1.

Circuit diagram of neurons of the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus. Fasted State (left panel): When a female experiences an energy deficit, AgRP neurons become highly active and release GABA onto Kiss1 and POMC neurons, inhibiting fertility and satiety. Fed State (right panel): When the female is fed and/or in a high 17β-estradiol state (e.g., proestrus), AgRP neurons become less active and their inhibitory input onto Kiss1 and POMC neurons is diminished. Concurrently, the probability of glutamate release is enhanced in both Kiss1 and POMC neurons. While glutamate released onto AgRP neurons will activate excitatory α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors, the influence will be an overall inhibitory effect through Group II/III metabotropic glutamate channels. Conversely, POMC neurons express excitatory Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors and their increased activity may cause the release of neuropeptides such as β-endorphin, which will further inhibit AgRP neurons, decreasing food intake. POMC neurons also excite Kiss1 neurons via glutamate release.

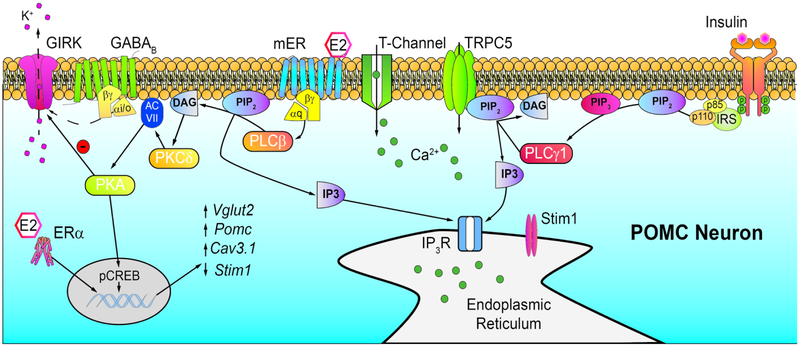

Short-term indicators of energy balance affect ARH function through both genomic and rapid mechanisms (Figure 2). In lean animals, insulin is released in response to higher blood glucose levels after meal consumption. Circulating insulin easily reaches the ARH neurons adjacent to the median eminence, and perfusion of insulin in vitro rapidly depolarizes POMC neurons through activation of TRPC5 channels [118]. In addition, insulin significantly increases Pomc mRNA expression in 72 hours following icv administration [119]. Both the canonical PI3K/AKT and calcium-activated signaling cascades, as a result of influx through the TRPC5 channels, can cause new gene (Pomc) transcription [120]. TPRC channels can function as both receptor- or store-operated channels opened, respectively, by membrane delimited receptors or depletion of Ca2+ stores [121, 122]. Obesity contributes to the development of insulin resistance, a core feature of metabolic disorders. Central nervous system (CNS) neurons, like other cells throughout the body, become insulin resistant. In the obese state, TRPC channels associate with the endoplasmic reticulum protein stromal-interaction molecule (STIM1) to function as store-operated and, hence, are no longer opened by insulin [122]. E2 protects females from developing CNS insulin resistance by downregulating STIM1 in POMC neurons, increasing their excitability, and preventing TRPC conversion to store-operated channels [123]. E2 also helps by preventing high-fat diet related upregulation of SOCS-3 (suppressor of cytokine signaling 3), preserving insulin signaling in females [123, 124]. Therefore, circulating estrogens are vital for maintaining insulin sensitivity throughout the female reproductive cycle and are neuroprotective against insulin resistance in obese states.

Figure 2.

E2 and insulin signaling cascades in POMC neurons. Insulin through its cognate receptor can activate phospholipase C (PLCγ) to cleave Phosphotidylinositol 4,5 biphosphate (PIP2) into Diacylglycerol (DAG) and Inositol triphosphate (IP3) opening TRPC5 channels and generating an inward cationic current to depolarize POMC neurons. Binding of E2 to Gαq-coupled mERs activates phospholipase C (PLCβ) – protein kinase C (PKCδ) – adenylyl cyclase (ACVII) – protein kinase A (PKA) signaling cascade to decouple GABAB (and μ-opioid) receptors from inhibitory G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+(GIRK) channels. PKA can also phosphorylate cAMP response element binding protein (pCREB) to generate new gene transcription through CRE’s. In addition, E2 binds to estrogen receptor α (ERα) in POMC neurons to increase Pomc, Vglut2, TRPC5 and CaV3.1 gene expression through ERE’s. On the other hand, stromal interacting molecule 1 (Stim1) expression is decreased, preserving TRPC5 channels as receptor operated channels for transmitting insulin’s (and leptin’s) effects. Note: E2 has similar actions in kisspeptin neurons with the exception that E2 downregulates the expression of the peptide.

3. E2 regulation of ARH neurons

More subtle influences are present during normal healthy reproductive cycles. Food intake, specifically sweet foods, decreases during the follicular phase (high E2) of the menstrual cycle [125-127]. The degeneration of AgRP neurons, induced via cell-specific deletion of the mitochondrial transcription factor A gene, eliminates cyclic changes in ingestive behavior [128]. Ovariectomy leads to a decrease in motor activity [129-131] and increased food intake [21, 132-137], but E2 replacement is sufficient to restore normal energy balance [21, 129- 131, 133, 138]. On the receptor side of estrogenic signaling, ERα knockout mice develop an obese phenotype similar to that seen following ovariectomy [139]. Metabolic deficits are reversed by restoration of ERα, despite lacking the ERE targeting domain, which emphasizes the importance of non-classical signaling [140]. Interestingly, POMC-specific deletion of ERα is sufficient to induce hyperphagia and increased heat production [54]. This phenotype could be due to higher circulating levels of E2, which is suggested by blunted negative feedback of E2 on LH release that produces abnormal estrous cycles. Therefore, estrogenic signaling is of tantamount importance to the anorexigenic function of POMC neurons in females. Perhaps, Kiss1 and POMC neurons set the tone of homeostatic circuits based on the reproductive state of the female. The neuronal activity of AgRP neurons is suppressed until energy reserves reach critical low levels. For example, fasting enhances AgRP activity and signaling by rapidly rewiring circuits and affecting gene transcription [141, 142]. However, under normal physiological conditions rapid E2 signaling in AgRP neurons may be a more appropriate means of adjusting their activity. For example, E2 quickly alters AgRP excitability, enhancing or attenuating the excitability (i.e., coupling of GABAB receptors to activate G protein inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) channels), possibly depending on the relative expression of ERα to mER [14,, 15]. These findings suggest that estrogenic signaling uses both genomic and rapid mechanisms to regulate POMC and Kiss1 function but relies more on membrane-initiated signaling for AgRP neurons.

For some time now, it has been accepted that AgRP neurons send inhibitory GABAergic projections to POMC neurons [70, 99]. More recently evidence has emerged that POMC neurons send reciprocal projections to AgRP neurons, primarily releasing β-endorphin and glutamate (Figure 1) [78]. A previous report found GABAergic inhibitory currents to be the most common response in unidentified ARH neurons following optogenetic stimulation of POMC neurons [75]. Surprisingly, optogenetic activation of POMC neurons rarely elicits a fast GABAergic or a slow excitatory (e.g. α-MSH) postsynaptic current in AgRP neurons [67, 70, 78]. While very few ARH NPY neurons express MC4R, nearly half express MC3R [143]. Therefore, the infrequency of GABA and melanocortin mediated responses suggests segregated neurotransmission [144-147]. The predominance of POMC glutamatergic, not GABAergic, inputs is counterintuitive as one would not expect a satiety neuron to excite a hunger neuron. However, glutamatergic input from POMC neurons would still be inhibitory in a high E2 state since Group II/III mGluRs are the most highly expressed in AgRP neurons [66]. High E2 will directly enhance the efficacy of POMC signaling through greater precursor peptide processing [148, 149] and increased expression of Vglut2 [78]. Furthermore, acutely applied E2 or STX increases the probability of glutamate release [78], possibly by decoupling GABAB and G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) channels in POMC nerve terminals (Figure 2) [21, 150]. Together these effects will support POMC inhibition of AgRP neurons. Kiss1ARH neurons also display increased expression of Vglut2 and glutamate release probability onto POMC and AgRP neurons [66]. Therefore when E2 is low, POMC activity will be minimal, generating a trickle of glutamate release onto AgRP neurons (Figure 1). When an animal is fed, AgRP neurons become less active, reducing inhibitory input onto POMC neurons [151]. POMC activity will increase to higher (20 Hz) frequencies [152], which are capable of eliciting β-endorphin release to inhibit AgRP neurons via activation of μ-opioid receptors [78]. In a high-E2 state, POMC and Kiss1 neurons will also have enhanced glutamate release, inhibiting AgRP neurons through Group II/III metabotropic glutamate receptors [66, 78]. Concurrently, Kiss1ARH neurons will excite POMC neurons through Group I mGluRs [66]. This arrangement between ARH neurons prevents minor fluctuations in the energy state of the animal from triggering drastic changes in ARH function [151], but also allows E2 to bias the system towards reduced food intake. Rapid estrogenic signaling will smooth the state transitions as slower, transcriptional mechanisms are engaged. The functional relevance of these circuit dynamics could be realized in shifts in food motivation. Assuming the female has sufficient energy stores, ovulation is induced, and reward salience is shifted from food to potential mates. Without estrogen ovariectomized female rodents retain food motivation and find sucrose more rewarding than E2-treated females [153]. When Vglut2 is deleted from Kiss1ARH neurons, this protective effect of E2 is abrogated [66], suggesting glutamatergic inhibition of AgRP neurons and excitation of POMC neurons may be an underlying mechanism (Figure 1). Therefore, there is little doubt that estrogenic signaling is necessary for Kiss1 neurons to control GnRH and LH release. However, it is also becoming clear that estrogens orchestrate communication between Kiss1, AgRP, and POMC neurons to optimize reproductive success.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank current and former members of their laboratories who contributed to the work described herein. Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institute of Health R01 grants NS 38809 (MJK), NS 43330 (OKR) and DK 68098 (MJK & OKR).

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].King JC, Tobet SA, Snavely FL, and Arimura AA, The LHRH system in normal and neonatally androgenized female rats. Peptides, 1980. 1: p. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lehman MN, Robinson JE, Karsch FJ, and Silverman AJ, Immunocytochemical localization of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone(LHRH) pathways in the sheep brain during anestrous and the mid-luteal phase of the estrous cycle. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 1986. 244: p. 19–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Silverman AJ, Distribution of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LH-RH) in the guinea pig brain. Endocrinology, 1976. 99: p. 30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Silverman AJ, Antunes JL, Abrams GM, Nilaver G, Thau R, Robinson JA, Ferin M, and Krey LC, The luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone pathway in rhesus(Macaca mulatta) and pigtailed (Macaca nemestrina) monkeys: New observations on thick, unembedded sections. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 1982. 211: p. 309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].King JC, Anthony ELP, Fitzgerald DM, and Stopa EG, Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons in human preoptic/hypothalamus: differential intraneuronal localization of immunoreactive forms. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 1985. 60: p. 88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jensen EV and DeSombre ER, Estrogen-receptor interaction. Science, 1973. 182(4108): p. 126–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Greene GL, Gilna P, Waterfield M, Baker A, Hort Y, and Shine J, Sequence and expression of human estrogen receptor complementary DNA. Science, 1986. 231(4742): p. 1150–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kuiper GG, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, and Gustafsson JÅ, Cloning of a novel estrogen receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1996. 93: p. 5925–5930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gruber CJ, Gruber DM, Gruber IM, Wieser F, and Huber JC, Anatomy of the estrogen response element. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2004. 15(2): p. 73–8. 10.1016/j.tem.2004.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Muramatsu M and Inoue S, Estrogen receptors: how do they control reproductive and nonreproductive functions? Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2000. 270(1): p. 1–10. 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].O'Malley BW and Tsai MJ, Molecular pathways of steroid receptor action. Biology of Reproduction, 1992. 46(2): p. 163–7. 10.1095/biolreprod46.2.163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kelly MJ and Levin ER, Rapid actions of plasma membrane estrogen receptors. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2001. 12(4): p. 152–6. 10.1016/S1043-2760(01)00377-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kelly MJ and Rønnekleiv OK, Mini-review: neural signaling of estradiol in the hypothalamus. Molecular Endocrinology, 2015. 29(5): p. 645–657. 10.1210/me.2014-1397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Smith AW, Bosch MA, Wagner EJ, Rønnekleiv OK, and Kelly MJ, The membrane estrogen receptor ligand STX rapidly enhances GABAergic signaling in NPY/AgRP neurons: Role in mediating the anorexigenic effects of 17;β-estradiol. American Journal of Physiology: Endocrinology and Metabolism, 2013. 305(5): p. E632–E640. 10.1152/ajpendo.00281.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Smith AW, Rønnekleiv OK, and Kelly MJ, Gq-mER signaling has opposite effects on hypothalamic orexigenic and anorexigenic neurons. Steroids, 2014. 81: p. 31–35. 10.1016/j.steroids.2013.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Carmeci C, Thompson DA, Ring HZ, Francke U, and Weigel RJ, Identification of a gene (GPR30) with homology to the G-protein-coupled receptor superfamily associated with estrogen receptor expression in breast cancer. Genomics, 1997. 45(3): p. 607–17. 10.1006/geno.1997.4972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].O'Dowd BF, Nguyen T, Marchese A, Cheng R, Lynch KR, Heng HH, Kolakowski LF Jr., and George SR, Discovery of three novel G-protein-coupled receptor genes. Genomics, 1998. 47(2): p. 310–3. 10.1006/geno.1998.5095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Owman C, Blay P, Nilsson C, and Lolait SJ, Cloning of human cDNA encoding a novel heptahelix receptor expressed in Burkitt's lymphoma and widely distributed in brain and peripheral tissues. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 1996. 228(2):p. 285–92. 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Takada Y, Kato C, Kondo S, Korenaga R, and Ando J, Cloning ofcDNAs encoding G protein-couple receptor expressed in human endothelial cells exposed to fluid shear stress. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 1997. 240: p. 737–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Qiu J, Bosch MA, Tobias SC, Grandy DK, Scanlan TS, Rønnekleiv OK, and Kelly MJ, Rapid signaling of estrogen in hypothalamic neurons involves a novel G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor that activates protein kinase C. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2003. 23(29): p. 9529–9540. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-29-09529.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Qiu J, Bosch MA, Tobias SC, Krust A, Graham S, Murphy S, Korach KS, Chambon P, Scanlan TS, Rønnekleiv OK, and Kelly MJ, A G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor is involved in hypothalamic control of energy homeostasis. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2006. 26: p. 5649–5655. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0327-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wintermantel TM, Campbell RE, Porteous R, Bock D, Grone HJ, Todman MG, Korach KS, Greiner E, Perez CA, Schutz G, and Herbison AE, Definition of estrogen receptor pathway critical for estrogen positive feedback to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons and fertility. Neuron, 2006. 52(2): p. 271–80. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chu Z, Andrade J, Shupnik MA, and Moenter SM, Differential regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron activity and membrane properties by acutely applied estradiol: dependence on dose and estrogen receptor subtype. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2009. 29(17): p. 5616–27. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0352-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kallo I, Butler JA, Barkovics-Kallo M, Goubillon ML, and Coen CW, Oestrogen receptor β-immunoreactivity in gonadotropin releasing hormone-expressing neurones: regulation by oestrogen. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 2001. 13(9): p. 741–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Terasawa E and Kenealy BP, Neuroestrogen, rapid action of estradiol, and GnRH neurons. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 2012. 33(4): p. 364–75. 10.1016/j.yfrne.2012.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Cravo RM, Margatho LO, Osborne-Lawrence S, Donato JJ, Atkin S, Bookout AL, Rovinsky S, Frazão R, Lee CE, Gautron L, Zigman JM, and Elias CF, Characterization of Kiss 1 neurons using transgenic mouse models. Neuroscience, 2011. 173: p. 37–56. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.11.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Clarkson J and Herbison AE, Dual phenotype kisspeptin-dopamine neurones of the rostral periventricular area of the third ventricle project to GnRH hormones. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 2011. 23: p. 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kotani M, Detheux M, Vandenbogaerde A, Communi D, Vanderwinden JM, Le Poul E, Brezillon S, Tyldesley R, Suarez-Huerta N, Vandeput F, Blanpain C, Schiffmann SN, Vassart G, and Parmentier M, The metastasis suppressor gene KiSS-1 encodes kisspeptins, the natural ligands of the orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR54. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2001. 276(37): p. 34631–6. 10.1074/jbc.M104847200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bosch MA, Tonsfeldt KJ, and Rønnekleiv OK, mRNA expression of ion channels in GnRH neurons: subtype-specific regulation by 17β-Estradiol. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 2013. 367(1–2): p. 85–97. 10.1016/j.mce.2012.12.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Seminara SB, Messager S, Chatzidaki EE, Thresher RR, Acierno JS, Shagoury JK, Bo-Abbas Y, Kuohung W, Schwinof KM, Hendrick AG, Zahn D, Dixon J, Kaiser UB, Slaugenhaupt SA, Gusella JF, O'Rahilly S, Carlton MBL, Crowley WF, Aparicio SAJR, and Colledge WH, The GPR54 gene as a regulator of puberty. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2003. 349: p. 1614–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].d'Anglemont de Tassigny X, Fagg LA, Dixon JPC, Day K, Leitch HG, Hendrick AG, Zahn D, Franceschini I, Caraty A, Carlton MBL, Aparicio SAJR, and Colledge WH, Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in mice lacking a functional KiSS 1 gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2007. 104: p. 10714–10719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gottsch ML, Cunningham MJ, Smith JT, Popa SM, Acohido BV, Crowley WF, Seminara S, Clifton DK, and Steiner RA, A role for kisspeptins in the regulation of gonadotropin secretion in the mouse. Endocrinology, 2004. 145(9): p. 4073–7. 10.1210/en.2004-0431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kinoshita M, Tsukamura H, Adachi S, Matsui H, Uenoyama Y, Iwata K, Yamada S, Inoue K, Ohtaki T, Matsumoto H, and Maeda K, Involvement of central metastinin the regulation of preovulatory luteinizing hormone surge and estrous cyclicity in female rats. Endocrinology, 2005. 146(10): p. 4431–6. 10.1210/en.2005-0195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Han S-K, Gottsch ML, Lee KJ, Popa SM, Smith JT, Jakawich SK, Clifton DK, Steiner RA, and Herbison AE, Activation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons by kisspeptin as a neuroendocrine switch for the onset of puberty. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2005. 25: p. 11349–11356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Liu X, Lee K, and Herbison AE, Kisspeptin excites gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons through a phospholipase C / calcium-dependent pathway regulating multiple ion channels. Endocrinology, 2008. 149: p. 4605–4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zhang C, Roepke TA, Kelly MJ, and Rønnekleiv OK, Kisspeptin depolarizes gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons through activation of TRPC-like cationic channels. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2008. 28(17): p. 4423–4434. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5352-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Pielecka-Fortuna J, Chu Z, and Moenter SM, Kisspeptin acts directly and indirectly to increase gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron activity and its effects are modulated by estradiol. Endocrinology, 2008. 149(4): p. 1979–86. 10.1210/en.2007-1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Constantin S, Caligioni CS, Stojilkovic S, and Wray S, Kisspeptin-10 facilitates a plasma membrane-driven calcium oscillator in gonadotropin-releasing hormone-1 neurons. Endocrinology, 2009. 150(3): p. 1400–12. 10.1210/en.2008-0979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kroll H, Bolsover S, Hsu J, Kim SH, and Bouloux PM, Kisspeptin-evoked calcium signals in isolated primary rat gonadotropin- releasing hormone neurones. Neuroendocrinology, 2011. 93(2): p. 114–20. 10.1159/000321678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Shughrue PJ, Lane MV, and Merchenthaler I, Comparative distribution of estrogen receptor-α and -β mRNA in the rat central nervous system. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 1997. 388: p. 507–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Clarkson J, d'Anglemont de Tassigny X, Moreno AS, Colledge WH, and Herbison AE, Kisspeptin-GPR54 signaling is essential for preovulatory gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron activation and the luteinizing hormone surge. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2008. 28:p. 8691–8697. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1775-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Smith JT, Cunningham MJ, Rissman EF, Clifton DK, and Steiner RA, Regulation of Kiss1 gene expression in the brain of the female mouse. Endocrinology, 2005. 146(9): p. 3686–92. 10.1210/en.2005-0488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Piet R, Boehm U, and Herbison AE, Estrous cycle plasticity in the hyperpolarization-activated current Ih is mediated by circulating 17β-estradiol in preoptic area kisspeptin neurons. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2013. 33(26): p. 10828–10839. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1021-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Zhang C, Tonsfeldt KJ, Qiu J, Bosch MA, Kobayashi K, Steiner RA, Kelly MJ, and Rønnekleiv OK, Molecular mechanisms that drive estradiol-dependent burst firing of Kiss1 neurons in the rostral periventricular preoptic area. American Journal of Physiology: Endocrinology and Metabolism, 2013. 305(11): p. E1384–E1397. 10.1152/ajpendo.00406.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Zhang C, Bosch MA, Rønnekleiv OK, and Kelly MJ, 17β-estradiol increases persistent Na+ current and excitability of AVPV/PeN Kiss1 neurons in female mice. Molecular Endocrinology, 2015. 29(4): p. 518–527. 10.1210/me.2014-1392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wang L, DeFazio RA, and Moenter SM, Excitability and burst generation ofAVPV kisspeptin neurons are regulated by the estrous cycle via multiple conductances modulated by estradiol action. eNeuro, 2016. 3(3). 10.1523/ENEURO.0094-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Wiegand SJ, Terasawa E, and Bridson WE, Persistent estrus and blockade of progesterone-induced LH release follows lesions which do not damage the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Endocrinology, 1978. 102: p. 1645–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Rønnekleiv OK and Kelly MJ, Plasma prolactin and luteinizing hormone profiles during the estrous cycle of the female rat: effects of surgically induced persistent estrus. Neuroendocrinology, 1988. 47(2): p. 133–41. 10.1159/000124903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Petersen SL and Barraclough CA, Suppression of spontaneous LH surges in estrogen-treated ovariectomized rats by microimplants of antiestrogens into the preoptic brain. Brain Research, 1989. 484: p. 279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Ma YJ, Kelly MJ, and Rønnekleiv OK, Pro-gonadotropin-releasing hormone (ProGnRH) and GnRH content in the preoptic area and the basal hypothalamus of anterior medial preoptic nucleus/suprachiasmatic nucleus-lesioned persistent estrous rats. Endocrinology, 1990. 127(6): p. 2654–64. 10.1210/endo-127-6-2654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Qiu J, Nestor CC, Zhang C, Padilla SL, Palmiter RD, Kelly MJ, and Rønnekleiv OK, High-frequency stimulation-induced peptide release synchronizes arcuate kisspeptin neurons and excited GnRH neurons. eLife, 2016. 5: p. e16246. 10.7554/eLife.16246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Padilla SL, Carmody JS, and Zeltser LM, Pomc-expressing progenitors give rise to antagonistic neuronal populations in hypothalamic feeding circuits. Nature Medicine, 2010. 16(4): p. 403–5. 10.1038/nm.2126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Sanz E, Quintana A, Deem JD, Steiner RA, Palmiter RD, and McKnight GS, Fertility-regulating Kiss1 neurons arise from hypothalamic POMC-expressing progenitors. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2015. 35(14): p. 5549–56. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3614-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Xu Y, Nedungadi TP, Zhu L, Sobhani N, Irani BG, Davis KE, Zhang X, Zou F, Gent LM, Hahner LD, Khan SA, Elias CF, Elmquist JK, and Clegg DJ, Distinct hypothalamic neurons mediate estrogenic effects on energy homeostasis and reproduction. Cell Metabolism, 2011. 14(4): p. 453–65. 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Belgardt BF, Okamura T, and Brüning JC, Hormone and glucose signalling in POMC and AgRP neurons. The Journal of Physiology, 2009. 587(22): p. 5305–5314. 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.179192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Lauber AH, Mobbs CV, Muramatsu M, and Pfaff DW, Estrogen receptor messenger RNA expression in rat hypothalamus as a function of genetic sex and estrogen dose. Endocrinology, 1991. 129: p. 3180–3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Romano GJ, Krust A, and Pfaff DW, Expression and estrogen regulation of progesterone receptor mRNA in neurons of the mediobasal hypothalamus: an in situ hybridization study. Molecular Endocrinology, 1989. 3(8): p. 1295–300. 10.1210/mend-3-8-1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Shughrue PJ, Komm B, and Merchenthaler I, The distribution of estrogen receptor-β mRNA in the rat hypothalamus. Steroids, 1996. 61: p. 678–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Knobil E, The electrophysiology of the GnRH pulse generator in the rhesus monkey. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry, 1989. 33(4B): p. 669–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Wakabayashi Y, Nakada T, Murata K, Ohkura S, Mogi K, Navarro VM, Clifton DK, Mori Y, Tsukamura H, Maeda K-I, Steiner RA, and Okamura H, Neurokinin B and dynorphin A in kisspeptin neurons of the arcuate nucleus participate in generation of periodic oscillation of neural activity driving pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion in the goat. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2010. 30: p. 3124–3132. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5848-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Okamura H, Tsukamura H, Ohkura S, Uenoyama Y, Wakabayashi Y, and Maeda K, Kisspeptin and GnRH pulse generation. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 2013. 784: p. 297–323. 10.1007/978-1-4614-6199-9_14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Kinsey-Jones JS, Li XF, Luckman SM, and O'Byrne KT, Effects of kisspeptin-10 on the electrophysiological manifestation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator activity in the female rat. Endocrinology, 2008. 149(3): p. 1004–8. 10.1210/en.2007-1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Clarkson J, Han SY, Piet R, McLennan T, Kane GM, Ng J, Porteous RW, Kim JS, Colledge WH, Iremonger KJ, and Herbison AE, Definition of the hypothalamic GnRH pulse generator in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2017. 114(47): p. E10216–E10223. 10.1073/pnas.1713897114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Navarro VM, Gottsch ML, Chavkin C, Okamura H, Clifton DK, and Steiner RA, Regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion by kisspeptin/dynorphin/neurokinin B neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the mouse. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2009. 29(38): p. 11859–66. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1569-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Lehman MN, Coolen LM, and Goodman RL, Minireview: kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) cells of the arcuate nucleus: a central node in the control of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. Endocrinology, 2010. 151(8): p. 3479–89. 10.1210/en.2010-0022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Qiu J, Rivera HM, Bosch MA, Padilla SL, Stincic TL, Palmiter RD, Kelly MJ, and Rønnekleiv OK, Estrogenic-dependent glutamatergic neurotransmission from kisspeptin neurons governs feeding circuits in females. eLife, 2018. 7: p. e35656. 10.7554/eLife.35656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Aponte Y, Atasoy D, and Sternson SM, AGRP neurons are sufficient to orchestrate feeding behavior rapidly and without training. Nature Neuroscience, 2011. 14(3): p. 351–355. 10.1038/nn.2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Krashes MJ, Koda S, Ye C, Rogan SC, Adams AC, Cusher DS, Maratos-Flier E, Roth BL, and Lowell BB, Rapid, reversible activation of AgRP neurons drives feeding behavior in mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2011. 121(4): p. 1424–8. 10.1172/JCI46229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Krashes MJ, Shah BP, Koda S, and Lowell BB, Rapid versus delayed stimulation of feeding by the endogenously released AgRP neuron mediators GABA, NPY, and AgRP. Cell Metabolism, 2013. 18(4): p. 588–95. 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Atasoy D, Betley JN, Su HH, and Sternson SM, Deconstruction of a neural circuit for hunger. Nature, 2012. 488(7410): p. 172–7. 10.1038/nature11270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Padilla SL, Qiu J, Nestor CC, Zhang C, Smith AW, Whiddon BB, Rønnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ, and Palmiter RD, AgRP to Kiss1 neuron signaling links nutritional state and fertility. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2017. 114(9): p. 2413–2418. 10.1073/pnas.1621065114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Matsuzaki T, Iwasa T, Kinouchi R, Yoshida S, Murakami M, Gereltsetseg G, Yamamoto S, Kuwahara A, Yasui T, and Irahara M, Fasting reduces the kiss1 mRNA levels in the caudal hypothalamus of gonadally intact adult female rats. Endocrinologia Japonica, 2011. 58(11): p. 1003–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Wei Q, Krolewski DM, Moore S, Kumar V, Li F, Martin B, Tomer R, Murphy GG, Deisseroth K, Watson SJ, and Akil H, Uneven balance of power between hypothalamic peptidergic neurons in the control of feeding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2018. 115(40): p. E9489–E9498. 10.1073/pnas.1802237115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Zhan C, Zhou J, Feng Q, Zhang JE, Lin S, Bao J, Wu P, and Luo M, Acute and long-term suppression of feeding behavior by POMC neurons in the brainstem and hypothalamus, respectively. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2013. 33(8): p. 3624–32. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2742-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Dicken MS, Tooker RE, and Hentges ST, Regulation of GABA and glutamate release from proopiomelanocortin neuron terminals in intact hypothalamic networks. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2012. 32(12): p. 4042–8. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6032-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Hentges ST, Nishiyama M, Overstreet LS, Stenzel-Poore M, Williams JT, and Low MJ, GABA release from proopiomelanocortin neurons. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2004. 24(7): p. 1578–83. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3952-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Vrang N, Larsen PJ, Clausen JT, and Kristensen P, Neurochemical characterization of hypothalamic cocaine- amphetamine-regulated transcript neurons. The Journal of Neuroscience, 1999. 19(10): p. RC5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Stincic TL, Grachev P, Bosch MA, Rønnekleiv OK, and Kelly MJ, Estradiol drives the anorexigenic activity of proopiomelanocortin neurons in female mice. eNeuro, 2018. 5(4). 10.1523/eneuro.0103-18.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Leranth C, MacLusky NJ, Shanabrough M, and Naftolin F, Immunohistochemical evidence for synaptic connections between pro-opiomelanocortin-immunoreactive axons and LH-RH neurons in the preoptic area of the rat. Brain Research, 1988. 449: p. 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Thind KK and Goldsmith PC, Infundibular gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons are inhibited by direct opioid and autoregulatory synapses in juvenile monkeys. Neuroendocrinology, 1988. 47(3): p. 203–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Chen WP, Witkin JW, and Silverman AJ, Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons are directly innervated by catecholamine terminals. Synapse, 1989. 3(3): p. 288–90. 10.1002/syn.890030314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Lagrange AH, Rønnekleiv OK, and Kelly MJ, Estradiol-17β and μ-opioid peptides rapidly hyperpolarize GnRH neurons: A cellular mechanism of negative feedback? Endocrinology, 1995. 136: p. 2341–2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Masotto C, Sahu A, Dube MG, and Kalra SP, A decrease in opioid tone amplifies the luteinizing hormone surge in estrogen-treated ovariectomized rats: comparisons with progesterone effects. Endocrinology, 1990. 126(1): p. 18–25. 10.1210/endo-126-1-18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Zhang Q and Gallo RV, Effect of prodynorphin-derived opioid peptides on the ovulatory luteinizing hormone surge in the proestrous rat. Endocrine, 2002. 18(1): p. 27–32. 10.1385/ENDO:18:1:27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Lustig RH, Pfaff DW, and Fishman J, Opioidergic modulation of the oestradiol-induced LH surge in the rat: roles of ovarian steroids. Journal of Endocrinology, 1988. 116(1):p. 55–69. 10.1677/joe.0.1160055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Lustig R, Pfaff D, and Fishman J, Induction of LH hypersecretion in cyclic rats during the afternoon of oestrus by oestrogen in conjunction with progesterone antagonism or opioidergic blockade. Journal of Endocrinology, 1988. 117(2): p. 229–235. 10.1677/joe.0.1170229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Van Vugt DA, Bakst G, Dyrenfurth I, and Ferin M, Naloxone stimulation of luteinizing hormone secretion in the female monkey: influence of endocrine and experimental conditions. Endocrinology, 1983. 113(5): p. 1858–64. 10.1210/endo-113-5-1858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Babu GN, Marco J, Bona-Gallo A, and Gallo RV, Steroid-independent endogenous opioid peptide suppression of pulsatile luteinizing hormone release between estrus and diestrus 1 in the rat estrous cycle. Brain Research, 1987. 416(2): p. 235–242. 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90902-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Rossmanith WG, Mortola JF, and Yen SS, Role of endogenous opioid peptides in the initiation of the midcycle luteinizing hormone surge in normal cycling women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 1988. 67(4): p. 695–700. 10.1210/jcem-67-4-695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Manfredi-Lozano M, Roa J, Ruiz-Pino F, Piet R, Garcia-Galiano D, Pineda R, Zamora A, Leon S, Sanchez-Garrido MA, Romero-Ruiz A, Dieguez C, Vazquez MJ, Herbison AE, Pinilla L, and Tena-Sempere M, Defining a novel leptin–melanocortin–kisspeptin pathway involved in the metabolic control of puberty. Molecular Metabolism, 2016. 5(10): p. 844–857. 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Stengel A, Wang L, Goebel-Stengel M, and Tache Y, Centrally injected kisspeptin reduces food intake by increasing meal intervals in mice. Neuroreport, 2011. 22(5):p. 253–7. 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32834558df [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Nestor CC, Qiu J, Padilla SL, Zhang C, Bosch MA, Fan W, Aicher SA, Palmiter RD, Rønnekleiv OK, and Kelly MJ, Optogenetic stimulation of arcuate nucleus Kiss1 neurons reveals a steroid-dependent glutamatergic input to POMC and AgRP neurons in male mice. Molecular Endocrinology, 2016. 30(6): p. 630–44. 10.1210/me.2016-1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Fu LY and van den Pol AN, Kisspeptin directly excites anorexigenic proopiomelanocortin neurons but inhibits orexigenic neuropeptide Y cells by an indirect synaptic mechanism. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2010. 30(30): p. 10205–19. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2098-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Backholer K, Smith JT, Rao A, Pereira A, Iqbal J, Ogawa S, Li Q, and Clarke IJ, Kisspeptin cells in the ewe brain respond to leptin and communicate with neuropeptide Y and proopiomelanocortin cells. Endocrinology, 2010. 151(5): p. 2233–43. 10.1210/en.2009-1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Smith J, Backholer K, and Clarke IJ, Melanocortins may stimulate reproduction by activating orexin neurons in the dorsomedial hypothalamus and kisspeptin neurons in the preoptic area of the ewe. Endocrinology, 2009. 150(12): p. 5488–5497. 10.1210/en.2009-0604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Sandrock M, Schulz A, Merkwitz C, Schöneberg T, Spanel-Borowski K, and Ricken A, Reduction in corpora lutea number in obese melanocortin-4-receptor-deficient mice. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, 2009. 7(1): p. 24. 10.1186/1477-7827-7-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Wu Q, Whiddon BB, and Palmiter RD, Ablation of neurons expressing agouti-related protein, but not melanin concentrating hormone, in leptin-deficient mice restores metabolic function and fertility. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2012. 109: p. 3155–3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Granholm NH, Jeppesen KW, and Japs RA, Progressive infertility in female lethal yellow mice (Ay/α;strain C57BL/6J). Journal of Reproduction and Fertility, 1986. 76(1): p. 279–287. 10.1530/jrf.0.0760279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Cowley MA, Smart JL, Rubinstein M, Cerdán MG, Diano S, Horvath TL, Cone RD, and Low MJ, Leptin activates anorexigenic POMC neurons through a neural network in arcuate nucleus. Nature, 2001. 411: p. 480–484. 10.1038/35078085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Faouzi M, Leshan R, Bjornholm M, Hennessey T, Jones J, and Munzberg H, Differential accessibility of circulating leptin to individual hypothalamic sites. Endocrinology, 2007. 148(11): p. 5414–23. 10.1210/en.2007-0655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Ibrahim N, Bosch MA, Smart JL, Qiu J, Rubinstein M, Rønnekleiv OK, Low MJ, and Kelly MJ, Hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin neurons are glucose responsive and express KATP channels. Endocrinology, 2003. 144(4): p. 1331–40. 10.1210/en.2002-221033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Balsells M, García-Patterson A, and Corcoy R, Systematic review and meta-analysis on the association of prepregnancy underweight and miscarriage. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 2016. 207: p. 73–79. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Chan JL and Mantzoros CS, Role of leptin in energy-deprivation states: normal human physiology and clinical implications for hypothalamic amenorrhoea and anorrexia nervosa. Lancet, 2005. 366: p. 74–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Allaway HCM, Southmayd EA, and De Souza MJ, The physiology of functional hypothalamic amenorrhea associated with energy deficiency in exercising women and in women with anorexia nervosa. Hormone Molecular Biology and Clinical Investigation, 2016. 25(2): p. 91–119. 10.1515/hmbci-2015-0053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Golden NH and Shenker IR, Amenorrhea in anorexia nervosa neuroendocrine control of hypothalamic dysfunction. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 1994. 16(1): p. 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, and Friedman JM, Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature, 1994. 372(6505): p. 425–32. 10.1038/372425a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Ingalls AM, Dickie MM, and Snell GD, Obese, a new mutation in the house mouse. Journal of Heredity, 1950. 41(12): p. 317–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Halaas JL, Gajiwala KS, Maffei M, Cohen SL, Chait BT, Rabinowitz D, Lallone RL, Burley SK, and Friedman JM, Weight-reducing effects of the plasma protein encoded by the obese gene. Science, 1995. 269(5223): p. 543–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Finn PD, Cunningham MJ, Pau KY, Spies HG, Clifton DK, and Steiner RA, The stimulatory effect of leptin on the neuroendocrine reproductive axis of the monkey. Endocrinology, 1998. 139(11): p. 4652–62. 10.1210/endo.139.11.6297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Quennell JH, Mulligan AC, Tups A, Liu X, Phipps SJ, Kemp CJ, Herbison AE, Grattan DR, and Anderson GM, Leptin indirectly reulates gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal function. Endocrinology, 2009. 150: p. 2805–2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Donato JJ, Cravo RM, Frazão R, Gautron L, Scott MM, Lachey J, Castro IA, Margatho LO, Lee S, Lee C, Richardson JA, Friedman J, Chua S Jr., Coppari R, Zigman JM, Elmquist JK, and Elias CF, Leptin's effect on puberty in mice is relayed by the ventral premammillary nucleus and does not require signaling in Kiss1 neurons. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2011. 121: p. 355–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Qiu J, Fang Y, Bosch MA, Rønnekleiv OK, and Kelly MJ, Guinea pig kisspeptin neurons are depolarized by leptin via activation of TRPC channels. Endocrinology, 2011. 152(4): p. 1503–14. 10.1210/en.2010-1285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].van den Top M, Lee K, Whyment AD, Blanks AM, and Spanswick D, Orexigen-sensitive NPY/AgRP pacemaker neurons in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus. Nature Neuroscience, 2004. 7(5): p. 493–4. 10.1038/nn1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Yura S, Ogawa Y, Sagawa N, Masuzaki H, Itoh H, Ebihara K, Aizawa-Abe M, Fujii S, and Nakao K, Accelerated puberty and late-onset hypothalamic hypogonadism in female transgenic skinny mice overexpressing leptin. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2000. 105(6): p. 749–755. 10.1172/JCl8353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Ahima RS, Dushay J, Flier SN, Prabakaran D, and Flier JS, Leptin accelerates the onset of puberty in normal female mice. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 1997. 99(3): p. 391–395. 10.1172/JCI119172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Aksglaede L, Juul A, Olsen LW, and Sørensen TIA, Age at puberty and the emerging obesity epidemic. PLOS ONE, 2009. 4(12): p. e8450. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].De Leonibus C, Marcovecchio ML, Chiavaroli V, de Giorgis T, Chiarelli F, and Mohn A, Timing of puberty and physical growth in obese children: a longitudinal study in boys and girls. Pediatric Obesity, 2014. 9(4): p. 292–299. 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2013.00176.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Qiu J, Zhang C, Borgquist A, Nestor CC, Smith AW, Bosch MA, Ku S, Wagner EJ, Rønnekleiv OK, and Kelly MJ, Insulin excites anorexigenic proopiomelanocortin neurons via activation of canonical transient receptor potential channels. Cell Metabolism, 2014. 19(4): p. 682–93. 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Benoit SC, Air EL, Coolen LM, Strauss R, Jackman A, Clegg DJ, Seeley RJ, and Woods SC, The catabolic action of insulin in the brain is mediated by melanocortins. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2002. 22: p. 9048–9052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Dodd GT and Tiganis T, Insulin action in the brain: Roles in energy and glucose homeostasis. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 2017. 29(10): p. e12513. 10.1111/jne.12513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Birnbaumer L, The TRPC class of ion channels: a critical review of their roles in slow, sustained increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 2009. 49: p. 395–426. 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Salido GM, Jardin I, and Rosado JA, The TRPC ion channels: association with Orai1 and STIM1 proteins and participation in capacitative and non-capacitative calcium entry. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 2011. 704: p. 413–33. 10.1007/978-94-007-0265-3_23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Qiu J, Bosch MA, Meza C, Navarro UV, Nestor CC, Wagner EJ, Rønnekleiv OK, and Kelly MJ, Estradiol protects proopiomelanocortin neurons against insulin resistance. Endocrinology, 2018. 159(2): p. 647–664. 10.1210/en.2017-00793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Boucher J, Kleinridders A, and Kahn CR, Insulin receptor signaling in normal and insulin-resistant states. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 2014. 6(1): p. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009191. 10.1101/cshperspect.a009191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Asarian L and Geary N, Sex differences in the physiology of eating. American Journal of Physiology:Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 2013. 305(11):p. R1215–67. 10.1152/ajpregu.00446.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Bowen DJ and Grunberg NE, Variations in food preference and consumption across the menstrual cycle. Physiology & Behavior, 1990. 47(2): p. 287–291. 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90144-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Fong AK and Kretsch MJ, Changes in dietary intake, urinary nitrogen, and urinary volume across the menstrual cycle. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 1993. 57(1): p. 43–6. 10.1093/ajcn/57.1.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Olofsson LE, Pierce AA, and Xu AW, Functional requirement of AgRP and NPY neurons in ovarian cycle-dependent regulation of food intake. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2009. 106(37): p. 15932–7. 10.1073/pnas.0904747106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Colvin GB and Sawyer CH, Induction of running activity by intracerebral implants of estrogen in overiectomized rats. Neuroendocrinology, 1969. 4(4): p. 309–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Ahdieh HB and Wade GN, Effects of hysterectomy on sexual receptivity, food intake, running wheel activity, and hypothalamic estrogen and progestin receptors in rats. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 1982. 96(6): p. 886–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Shimomura Y, Shimizu H, Takahashi M, Sato N, Uehara Y, Fukatsu A, Negishi M, Kobayashi I, and Kobayashi S, The significance of decreased ambulatory activity during the generation by long-term observation of obesity in ovariectomized rats. Physiology & Behavior, 1990. 47(1): p. 155–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Geary N, The estrogenic inhibition of eating, in Handbook of behavioral neurobiology, Strieker EM and Woods SC, Editors. 2007, Kluwer Academic/Plenum: New York, NY. p. 307–345. [Google Scholar]

- [133].Asarian L and Geary N, Cyclic estradiol treatment normalizes body weight and restores physiological patterns of spontaneous feeding and sexual receptivity in ovariectomized rats. Hormones and Behavior, 2002. 42(4): p. 461–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Czaja JA and Goy RW, Ovarian hormones and food intake in female guinea pigs and rhesus monkeys. Hormones and Behavior, 1975. 6(4): p. 329–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [135].Butera PC and Czaja JA, Intracranial estradiol in ovariectomized guinea pigs: effects on ingestive behaviors and body weight. Brain Research, 1984. 322(1): p. 41–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [136].Czaja JA, Sex differences in the activational effects of gonadal hormones on food intake and body weight. Physiology & Behavior, 1984. 33(4): p. 553–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [137].McCaffrey TA and Czaja JA, Diverse effects of estradiol-17 β: concurrent suppression of appetite, blood pressure and vascular reactivity in conscious, unrestrained animals. Physiology & Behavior, 1989. 45(3): p. 649–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [138].Roepke TA, Xue C, Bosch MA, Scanlan TS, Kelly MJ, and Rønnekleiv OK, Genes associated with membrane-initiated signaling of estrogen and energy homeostasis. Endocrinology, 2008. 149(12): p. 6113–24. 10.1210/en.2008-0769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [139].Heine PA, Taylor JA, Iwamoto GA, Lubahn DB, and Cooke PS, Increased adipose tissue in male and female estrogen receptor-α knockout mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2000. 97(23): p. 12729–34. 10.1073/pnas.97.23.12729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [140].Park CJ, Zhao Z, Glidewell-Kenney C, Lazic M, Chambon P, Krust A, Weiss J, Clegg DJ, Dunaif A, Jameson JL, and Levine JE, Genetic rescue of nonclassical ERα signaling normalizes energy balance in obese ERα-null mutant mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2011. 121: p. 604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [141].Pinto S, Roseberry AG, Liu H, Diano S, Shanabrough M, Cai X, Friedman JM, and Horvath TL, Rapid rewiring of arcuate nucleus feeding circuits by leptin. Science, 2004. 304(5667): p. 110–5. 10.1126/science.1089459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [142].Roepke TA, Qiu J, Smith AW, Rønnekleiv OK, and Kelly MJ, Fasting and 17β-estradiol differentially modulate the M-current in neuropeptide Y neurons. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2011. 17(33): p. 11825–11835. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1395-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [143].Mounien L, Bizet P, Boutelet I, Vaudry H, and Jegou S, Expression of melanocortin MC3 and MC4 receptor mRNAs by neuropeptide Y neurons in the rat arcuate nucleus. Neuroendocrinology, 2005. 82(3– 4): p. 164–70. 10.1159/000091737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [144].Kavalali ET, The mechanisms and functions of spontaneous neurotransmitter release. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2015. 16(1): p. 5–16. 10.1038/nrn3875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [145].Lee S, Zhang Y, Chen M, and Zhou ZJ, Segregated glycine-glutamate co-transmission from vGluT3 amacrine cells to contrast-suppressed and contrast-enhanced retinal circuits. Neuron, 2016. 90(1): p. 27–34. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.02.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [146].Nishimaru H, Restrepo CE, Ryge J, Yanagawa Y, and Kiehn O, Mammalian motor neurons corelease glutamate and acetylcholine at central synapses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2005. 102(14): p. 5245–9. 10.1073/pnas.0501331102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [147].Fortin GM, Ducrot C, Giguère N, Kouwenhoven WM, Bourque M-J, Pacelli C, Varaschin RK, Brill M, Singh S, Wiseman PW, and Trudeau L-É, Segregation of dopamine and glutamate release sites in dopamine neuron axons: regulation by striatal target cells. The FASEB Journal, 2018. 33(1): p. 400–417. 10.1096/fj.201800713RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [148].Bethea CL, Hess DL, Widmann AA, and Henningfeld JM, Effects of progesterone on prolactin, hypothalamic β-endorphin, hypothalamic substance P, and midbrain serotonin in guinea pigs. Neuroendocrinology, 1995. 61(6): p. 695–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [149].Thornton JE, Loose MD, Kelly MJ, and Rønnekleiv OK, Effects of estrogen on the number of neurons expressing β-endorphin in the medial basal hypothalamus of the female guinea pig. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 1994. 341: p. 68–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [150].Qiu J, Rønnekleiv OK, and Kelly MJ, Modulation of hypothalamic neuronal activity through a novel G-protein coupled estrogen membrane receptor. Steroids, 2008. 73(9-10):p. 985–991. 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [151].Yang Y, Atasoy D, Su HH, and Sternson SM, Hunger states switch a flip-flop memory circuit via a synaptic AMPK-dependent positive feedback loop. Cell, 2011. 146(6): p. 992–1003. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [152].Moss RL, Kelly M, and Riskind P, Tuberoinfundibular neurons: dopaminergic and norepinephrinergic sensitivity. Brain Research, 1975. 89(2): p. 265–77. 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90718-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [153].Galea LA, Wide JK, Paine TA, Holmes MM, Ormerod BK, and Floresco SB, High levels of estradiol disrupt conditioned place preference learning, stimulus response learning and reference memory but have limited effects on working memory. Behavioural Brain Research, 2001. 126(1-2): p. 115–126. 10.1016/S0166-4328(01)00255-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]