Abstract

Objective.

Adolescents living in rural regions of the United States face substantial barriers to accessing mental health services, creating needs for more accessible, non-stigmatizing, briefer interventions. Research suggests that single-session “growth mindset” interventions (GM-SSIs)—which teach the belief that personal traits are malleable through effort—may reduce internalizing and externalizing problems in adolescents. However, GM-SSIs have not been evaluated among rural youth, and their effects on internalizing and externalizing problems have not been assessed within a single trial, rendering their relative benefits for different problem types unclear. We examined whether a computerized GM-SSI could reduce depressive symptoms, social anxiety symptoms, and conduct problems in adolescent girls from rural areas of the U.S.

Method.

Tenth-grade girls (N=222, M age=15.2, 38% white, 25% Black, 29% Hispanic) from four rural, low-income high schools in the Southeastern United States were randomized to receive a 45-minute GM-SSI or a computer-based, active control program, teaching healthy sexual behaviors. Girls self-reported depression symptoms, social anxiety symptoms, and conduct problem behaviors at baseline and four-month follow-up.

Results.

Relative to girls in the control group, girls receiving the GM-SSI reported modest but significantly greater reductions in depressive symptoms (d=.23) and likelihood of reporting elevated depressive symptoms (d=.29) from baseline to follow-up. GM-SSI effects were nonsignificant for social anxiety symptoms, although a small effect size emerged in the hypothesized direction (d=.21), and nonsignificant for change in conduct problems (d=.01).

Conclusions.

A free-of-charge, 45-minute GM-SSI may help reduce internalizing distress, especially depression—but not conduct problems—in rural adolescent girls.

Keywords: Adolescence, depression, single-session intervention, mindset, rural youth

Mental health problems place fiscal and emotional burdens on youth, their families, and the systems that serve them. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2014), 20% of youth in the United States experience mental health challenges that interfere with learning, relationships, and daily functioning prior to the age of 18, and suicide has emerged as the second-leading cause of death among young people ages 10 to 24 (Perou et al., 2013). Although numerous evidence-based mental health interventions have been identified (Weisz et al., 2017), they tend to be costly in both money and time and are designed for delivery in brick-and-mortar clinics by professional therapists, making them difficult to disseminate. Indeed, up to 80% of young people with mental health needs in the United States do not access services (Kataoka, Zhang, & Wells, 2002; Konrad, Ellis, Thomas, Holzer, & Morrissey, 2009). Even among those who do, 28–59% drop-out prematurely (Harpaz-Rotem, Leslie, & Rosenheck, 2004; Kataoka et al., 2002; Konrad et al., 2009; Harpaz-Rotem et al., 2004). Barriers to treatment access are especially acute in rural regions of the U.S., where provider shortages, transportation barriers, and financial constraints are pervasive (Bellamy, Bolin, & Gamm, 2011). Thus, there is a critical need for accessible, lower-cost, effective alternatives to traditional psychotherapy, especially for youth in rural areas. To help address this need, we examined whether a single-session, computerized intervention teaching growth mindset, the belief that personal traits and abilities are malleable (rather than fixed), could reduce depressive symptoms, social anxiety symptoms, and conduct problems in adolescent girls from rural areas of the U.S. Adolescent girls are substantially more likely than same-aged boys to experience depression (Nolen-Hoeksema & Hilt, 2013) and anxiety (McLean & Anderson, 2009), and adolescent girls living in rural regions of the U.S. have endorsed higher levels of aggression than their male peers (Smokowski, Cotter, Robertson, & Guo, 2012). Thus, rural adolescent girls may represent an especially high-need, high-risk group. To our knowledge, this study is the first to assess whether a growth mindset intervention can reduce internalizing and externalizing problems among adolescent girls living largely low-income, rural U.S. communities.

Unmet mental health needs among rural youth.

Although youth living in rural and urban areas report similar rates of psychiatric disorders (Kessler, Petukhova, Sampson, Zaslavsky, & Wittchen, 2012), treatment uptake and completion is markedly lower in rural areas (Robinson et al., 2017). Rural communities tend to be largely populated by individuals with intersecting risk factors for lower help-seeking and reduced service access (low educational attainment, poverty, racial/ethnic minority status; Bussing, Zima, Gary, & Garvan, 2003; Byun, Meece, Irvin, & Hutchins, 2012; Smalley, Warren, & Barefoot, 2016). Concurrently, lower population density and denser social networks in rural areas generate stigma and hesitancy to seek mental health treatment (Harowski, Turner, LeVine, Schank, & Leichter, 2006). Even families who do seek treatment have trouble finding providers: across all U.S. regions with severe shortages of youth mental health professionals, 61.6% are rural (U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, 2016). Parents living in rural areas are more likely than those in urban areas to cite limited transportation, financial strain, and lack of anonymity as barriers to accessing mental health care for their children (Skinner & Slifkin, 2007; Smalley et al., 2010), which partly explain rural families’ higher rates of early dropout from youth behavioral health services (Kelleher & Gardner, 2017). Thus, a need exists for non-stigmatizing, accessible, briefer mental health interventions for rural youth. Such interventions are unlikely to replace intensive treatment for youth with severe difficulties, but they may benefit some portion of youths who would otherwise go without services entirely.

Single-session interventions for rural youths’ mental health.

Certain types of single-session interventions (SSIs) may help address the unmet mental health needs of rural youth. A growing body of literature suggests that SSIs can reduce and prevent youth psychopathology, from anxiety and fears (Simon, Driessen, Lambert, & Muris, 2019) and oppositional behaviors (Mejia, Calam, & Sanders, 2015) to depressive symptoms (Schleider & Weisz, 2018). In a meta-analysis of 50 randomized clinical trials (Schleider & Weisz, 2017; N = 10,508 youths), SSIs for youth psychological problems demonstrated a significant positive effect (g = .32). This effect did not differ for treatments (i.e., trials for youths with psychiatric diagnoses) and preventive interventions (which did not require diagnoses), suggesting SSIs’ capacity to benefit youth with low, moderate, and even severe symptoms. Further, significant effects emerged even for self-administered (e.g. computerized) SSIs completed without a therapist (g = .32). Numerically, SSIs’ overall effects are slightly smaller than those for traditional, multi-session youth psychotherapy (Weisz et al., 2017; mean g = .46 for treatments lasting 16 sessions, on average). However, their brevity and accessibility—especially self-administered, computerized SSIs—suggests their potential to exert scalable benefits, especially for rural youths, who may face barriers in accessing other support. Indeed, 89.7% of Americans living in rural regions have access to either terrestrial or mobile wireless internet (Federal Communications Commission, 2018), suggesting computerized interventions’ capacity to reach a large portion of this population.

For these reasons, capitalizing on the advantages of both computer-based interventions and SSIs may help maximize novel programs’ capacity to reach a large portion of rural adolescents using feasible, affordable, acceptable delivery systems. A systematic review of trials testing computerized cognitive-behavioral therapy programs found that, overall, adolescents living in rural areas were more likely than those in urban areas to prefer computerized treatment to in-person treatment, citing confidentiality concerns and stigma around seeking face-to-face services (Vallury, Jones, & Oosterbroek, 2015). Further, computerized and therapist-delivered interventions for adolescent depression and anxiety have yielded similar reductions in psychopathology (see Ebert et al., 2015, for a meta-analysis). By reducing the need for in-person treatment in some portion of youth, computerized programs hold promise to increase the cost-effectiveness of services overall. Thus, identifying especially brief, well-targeted computerized interventions, such as SSIs—which may be more likely than multi-session programs to be completed in full by adolescents receiving them—may be of considerable public health value.

The promise of computerized growth mindset SSIs.

One computerized SSI that has shown promise in reducing youth psychopathology is the growth mindset SSI, which teaches youth that personal traits and attributes are malleable, as opposed to a fixed mindset, or the belief that such traits are immutable (Chiu, Hong, & Dweck, 1997). Mindsets about personal traits are understood as guiding beliefs that can shape interpretations and responses to personally salient setbacks (Paunesku et al., 2015; Yeager, Lee, & Jamieson, 2016). During adolescence, social and academic difficulties grow more common and distressing; perceived failures in either domain can threaten self-worth and mental health (Dumont & Provost, 1999; Shortt & Spence, 2006). Thus, an adolescent’s mindset about their competencies in social and academic domains is thought to promote adaptive, approach-oriented responding, in the case of a growth mindset, or increase vulnerability for maladaptive, avoidance-oriented responding, in the case of a fixed mindset. Indeed, compared to growth mindsets, fixed mindsets of personal traits correlate with and predict higher levels of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology in adolescents (Romero, Master, Paunesku, Dweck, & Gross, 2014; Schleider, Abel, & Weisz, 2015; Schleider & Weisz, 2016; Yeager, Miu, Powers, & Dweck, 2013; Yeager, Trzesniewski, Tirri, Nokelainen, & Dweck, 2011). By teaching more adaptive self-views and beliefs, growth mindset SSIs may offer a means of reconceptualizing and coping with these self-threatening setbacks. If personal traits (e.g., social or coping skills) can change, then peer rejection and psychological distress become solvable problems, not innate deficits. Thus, a growth mindset SSI may be a well-targeted strategy for improving adolescents’ perceived control over their actions, coping, and outcomes, ameliorating psychological symptoms of various types.

Randomized trials support these possibilities. In psychologically healthy adolescent samples, SSIs teaching growth mindset of one’s personality have prevented adolescents’ self-reported increases in depressive symptoms across nine months (Miu & Yeager, 2015) and produced more adaptive threat appraisals and more rapid neuroendocrine and sympathetic nervous system recovery after lab-based social stress tasks (Yeager, Lee, & Jamieson, 2016) compared to psychoeducation controls. A multi-session, school-based program teaching growth mindset of social status led to larger reductions in conduct problems three months later, relative to a coping-skills program (Yeager et al., 2013). Separately, adolescents with elevated internalizing problems who received a computerized growth mindset of personality SSI (versus an active control) reported larger post-intervention increases in perceived control over their behavior (d = .34) and emotions (d = .19); recovered from a lab-based social stress task more than three times as rapidly as comparison-group adolescents (Schleider & Weisz, 2016); and showed larger 9-month reductions in depressive symptoms across informants (parent-report d = .60, youth-report d = .32) and anxiety symptoms per parent-report (d = .28) (Schleider & Weisz, 2018).

Although specific contents of these interventions have varied, they have shared some common features, including: (1) non-stigmatizing frames, with no explicit references to “treatment” or “psychopathology;” (2) lessons on brain science and neuroplasticity to normalize content and strengthen buy-in; and (3) opportunities to offer advice to same-aged peers via “saying-is-believing” writing exercises (Aronson, 1999). These features aim to enhance program acceptability and credibility to adolescents, regardless of their interest in formal treatment. They may also render the intervention well-suited to rural adolescents, for whom mental health stigma and low anonymity in seeking services may reduce help-seeking. However, none of the above-mentioned trials tested effects of growth mindset SSIs on rural adolescents’ mental health, for whom these SSIs might have great practical value.

Relative benefits of growth mindset interventions for youth internalizing and externalizing problems?

None of the trials noted above tested a growth mindset SSI’s effects on internalizing and externalizing problems within one youth sample, rendering their relative benefits for different symptom types unclear. However, these interventions might influence problems across both domains. Fixed mindsets have been conceptualized as a cognitive vulnerability factor for youth psychopathology (Schleider & Schroder, 2018; Schleider, Abel, & Weisz, 2015). Cognitive vulnerability-stress models posit that one’s characteristic interpretations of negative events can confer vulnerability to maladaptive coping—and, in turn, psychopathology—after negative events (e.g., Beck, 1967; Dodge, 1986). In several studies, fixed views of personal traits have elicited maladaptive attributions in adolescents after setbacks: thinking “I’m unlikeable” after a fight with a peer or “he’s a bully” after seeing others act aggressively (Yeager & Dweck, 2012). By fostering these attributions in the face of stress, fixed mindsets may facilitate helplessness, reactive aggression, or passive, emotion-focused coping, which have been shown to underlie internalizing and externalizing problems (Alloy et al., 1990; Swearer & Hymel, 2015).

Consistent with this hypothesis, fixed mindsets have predicted both internalizing and externalizing problems in adolescence through their effects on maladaptive coping and attributions. Across eight samples of high school students, fixed personality mindsets significantly, indirectly predicted adolescents’ aggressive desires through increases in hostile intent attributions following hypothetical social setbacks in which others’ intentions were ambiguous (Yeager, Miu, Powers, & Dweck, 2013). Likewise, Markovic and colleagues (2013) found that the link between shyness and internalizing coping (including avoidance of evaluation from others) after peer-related setbacks was twice as large for early adolescents with fixed mindsets of personality, versus those with growth mindsets. Results of recent SSI trials further supports the conceptualization of fixed mindsets as a cognitive vulnerability for adolescent psychopathology. Compared to a supportive-therapy control, a growth mindset SSI led to increases in perceived primary control (the ability to influence objective events through personal effort; Rothbaum et al., 1982) and secondary control (the ability to adapt to uncontrollable, adverse events; Weisz et al., 2010) in adolescents with elevated depression and anxiety. In turn, these improvements led to reductions in anxiety and depressive symptoms 9 months later (Schleider & Weisz, 2016; Schleider, 2017; Schleider & Weisz, 2018). Together, these results suggest that fixed mindsets might increase risk for internalizing and externalizing problems in adolescents by fostering maladaptive attributions of stress, whereas SSIs instilling growth mindsets might promote more adaptive attributions and symptom trajectories. However, more research is needed to discern whether a growth mindset SSI can successfully reduce internalizing and externalizing problems—or whether tailoring of SSI content to specific youth outcomes and problem types (e.g., through a focus on certain types of mindsets, or applications of mindsets to particular real-world challenges) might be more beneficial.

Present study.

We evaluated whether a computerized, 45-minute SSI teaching growth mindsets of personality, self-regulation, and intelligence (Growing Minds; https://www.projectgrowingminds.com) could reduce depressive symptoms, social anxiety symptoms, and conduct problems across four months in adolescent girls living in rural regions of the Southeastern United States (N = 222; ages 14–17). We predicted that Growing Minds would produce significant reductions in all three symptom types from baseline to four-month follow-up relative to an active, attention-matched comparison intervention.

This study represents a secondary analysis of data drawn from a clinical trial ( NCT02579135) testing the relative effects of Growing Minds and a computerized SSI promoting healthy sexual behavior (HEART; Health Education and Relationship Training). Both SSIs’ effects on primary and secondary outcomes (intervention acceptability and adolescent sexual health behaviors for HEART; growth mindset, motivation to learn, learning efficacy, and school belonging, and grades for Growing Minds) are reported elsewhere (Burnette, Russell, Hoyt, Orvidas, & Widman, 2018; Widman, Golin, Kamke, Burnette, & Prinstein, 2018; Widman, Golin, Kamke, Massey, & Prinstein, 2017). Previously, Growing Minds was found to predict significant increases in girls’ growth mindsets from baseline to immediate post-SSI and four-month follow-up (Burnette et al., 2018). The intervention, relative to HEART, also indirectly predicted increases in girls’ motivation to learn, learning efficacy, and grades, via shifts in growth mindsets (Burnette et al., 2018). Outcomes of interest in the current study (depressive symptoms, social anxiety symptoms, conduct problems) have not been examined or published elsewhere.

Method

Participants.

Participants were recruited from 4 rural, low-income high schools in the southeastern United States in fall, 2015. All four are designated as Title 1 schools, with 66% of students eligible for free or reduce-price lunch. At each school, all 10th grade girls with active parental consent were eligible to participate; there were no further inclusion or exclusion criteria. (One of the two interventions tested in this trial was a sexual health behavior intervention designed for girls; thus, the study sample was female-only). Girls in this study (N = 222) were 24.43% Black, 29.41% Hispanic, 37.55% white, and 8.59% another race (see Table 1 for additional demographic details). These demographics approximated the overall racial and ethnic makeup of students at the four participating schools (overall, students at these schools are 34% Hispanic; 21% Black; 40% white).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics at baseline assessment by intervention condition.

| Characteristics | Growing Minds (n = 115) M (SD) or No. (%) | HEART (n = 107) M (SD) or No. (%) | p* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15.2 (.5) | 15.3 (.5) | .49 |

| White race/ethnicity | 45 (39.1) | 38 (35.5) | .62 |

| Black race/ethnicity | 25 (21.7) | 29 (27.1) | .33 |

| Hispanic race/ethnicity | 34 (29.6) | 31 (28.9) | .96 |

| Mother’s education < high school | 28 (24.3) | 21 (19.6) | .38 |

| Single-parent home | 56 (48.7) | 48 (44.9) | .43 |

| Depressive symptom elevations at baseline (SMFQ ≥ 11) | 44 (38.2) | 40 (37.4) | .40 |

Note.

Using chi-square for categorical variables and independent samples t test for continuous variables.

With respect to these schools’ surrounding environment, the regions represented in this study are approximately 45 miles from the nearest urban area, based on U.S. Department of Agriculture definitions of “urban” and “rural” areas as having population densities above versus below 1,000 residents per square mile, respectively (National Agricultural Library, 2016). Based on 2010 U.S. census data, these regions had a mean population density of 227.0 residents per square mile.

Procedures.

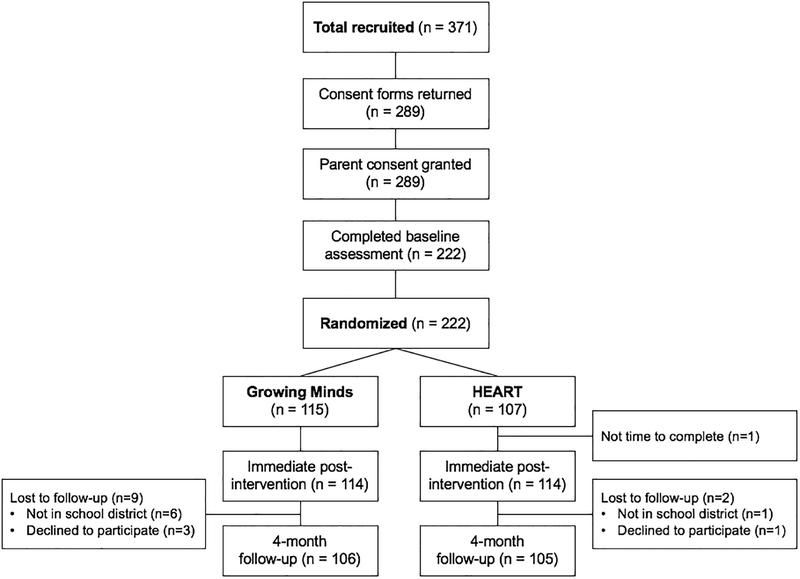

As indicated in the CONSORT diagram (Figure 1), 78% of eligible girls returned a parental consent form, and 79% of those girls’ parents granted consent for study participation. After consent and assent were obtained, participants completed a computerized, baseline questionnaire battery in a group-based classroom setting. Next, participants were randomly assigned to receive one of two computerized, 45-minute SSIs: Growing Minds (n = 115) or HEART (n = 107; interventions described below). An investigator independent of the study team conducted random assignment (stratified within school) per random sampling and allocation procedures in SPSS Version 22. Approximately two weeks after the baseline assessment, students completed their assigned SSI and an immediate post-SSI questionnaire battery. Research staff coordinated with school personnel to arrange for youths to complete their assigned SSI and immediate post-SSI questionnaires during school hours, during a single, individual session with a research assistant. Both of the SSIs were entirely self-administered by youths on computers; a research assistant was available to address students’ potential questions but did not actively facilitate SSI or questionnaire completion. Four months later, students completed a final questionnaire battery to gauge longer-term SSI effects. Thus, the study period extended from fall 2015 (when recruitment occurred) through spring 2016 (when the four-month follow-up occurred).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram

Participants were compensated with $10 for returning parental consent forms, regardless of whether consent was granted. Additionally, participants received $10 for the baseline assessment, $30 for the intervention and immediate post-test assessment, and $10 for the 4-month follow-up. The University Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures prior to the start of the study.

Intervention Conditions

Growing Minds.

Growing Minds is a 45-minute, self-administered, computerized SSI, which is publicly available at www.projectgrowingminds.com. It follows a general structure utilized in other growth mindset SSIs (e.g., Miu & Yeager, 2015; Schleider & Weisz, 2016; Schleider & Weisz, 2018), but unlike other mindset interventions, Growing Minds includes content related to multiple types of mindsets (personality; intelligence; self-regulation) across four interactive modules. The first module serves as an introduction to mindsets, and the remaining modules provide information and self-change strategies linked to intelligence mindsets, self-regulation mindsets, and personality mindsets, respectively. Each module includes scientific information about the brain or recent scientific studies; an explanation of why abilities in a given domain have potential for growth and change, via personal effort and support from others; ‘tips’ from older, college-aged peers about applying a given mindset type to coping with setbacks; and a “saying-is-believing” writing exercise, designed to facilitate message internalization, in which students use newly-acquired information about our potential for change to advise peers on coping with setbacks. Growing Minds also includes interactive quizzes (including feedback and opportunities for self-correction, in the case of incorrect responses) to gauge content retention and understanding.

HEART.

HEART (Health Education and Relationship Training) served as an attention-matched, active comparison intervention. Like Growing Minds, HEART is a computerized SSI; it is designed to cultivate healthy sexual decision-making and communication skills in adolescent girls (Widman, Golin, Noar, Massey, & Prinstein, 2016). Although its message is positive and it teaches evidence-based, helpful skills, HEART does not mention “growth mindset,” nor does it make explicit reference to the malleability of personal traits. Using a risk reduction framework, HEART targets five areas of sexual decision-making: safer sex motivation, knowledge regarding sexually transmitted diseases, sexual norms and attitudes, safer sex self-efficacy, and sexual communication skills. Participants engage with audio and video clips, tips from older adolescents, complete interactive games and quizzes throughout the program’s sequential modules. Additional details about the development, acceptability, and efficacy of HEART are detailed elsewhere (e.g., Widman et al., 2018). By design, HEART and Growing Minds take approximately the same amount of time to complete and included similarly engaging content, including videos, writing exercises, and quizzes across sequential modules.

Measures.

Below are descriptions of youth self-report questionnaires used in the present study. Information regarding the other assessments is available in prior reports of RCT outcomes (Burnette et al., 2018; Widman et al., 2018) and the study’s pre-registration ( NCT02579135 ). Notably, mental health outcomes were assessed at baseline and four-month follow-up only, as changes in symptoms were not expected to occur at immediate post-SSI. Thus, the only post-intervention data reported relate to growth mindsets, which served as a manipulation check for Growing Minds.

Growth mindsets of intelligence and personality.

Beliefs regarding the malleability of personality and intelligence, respectively, were assessed in brief (3-item) measures at baseline and immediate post-SSI and were modeled after mindset questionnaires used previously (Yeager et al., 2011, 2013). Here, mindsets from baseline to post-SSI served as a manipulation check for Growing Minds’ capacity to strengthen growth mindsets. Items included “You can learn new things, but you can’t really change your intelligence” and “People can do things differently, but the important parts of who they are can’t really be changed.” Students rated items on 1-to-7 Likert scale reflecting agreement with each statement, such that higher mean scores for all items indicated stronger growth mindsets, and lower scores, stronger fixed mindsets. Alphas for intelligence mindset items were α = .86 at baseline and α = .87 at post-SSI, and for personality mindset items, α =.79 at baseline and α = .83 at post-SSI.

Depressive symptoms.

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ; Angold, Costello, & Messer, 1995), a widely employed self-report measure of depressive symptoms in youth. The SMFQ includes 13 items, such as “feeling miserable or unhappy” and “I was very restless,” referencing the past month. Responses are made on a three point scale (0, “not true”; 1, “sometimes true”; 2, “true”) and summed to yield a total depressive symptom severity score. The SMFQ correlates highly with other widely-used youth depression measures (Angold et al., 1995; Turner, Joinson, Peters, Wiles, & Lewis, 2014). A score of ≥ 8 (on a 0–26 scale) has demonstrated 60% sensitivity and 85% specificity in detecting elevations in depressive symptoms, as well as validity in gauging “need for a mental health referral,” in community and school-based adolescent samples (Angold et al, 1995; Vander Stoep et al., 2005). Here, we assessed SSI effects on depressive symptoms via change in both continuous and binary (≥ 11 versus < 11) SMFQ scores from baseline to four-month follow-up. Alphas for the SMFQ were α = .93 and α = .94 baseline and follow-up.

Social anxiety symptoms.

Social anxiety symptoms, and specifically avoidance behaviors, were assessed using an adapted version of the 5-item Avoidance subscale from the Social Phobia Inventory, or SPIN (Connor et al., 2000). The phrasing of each item was altered to maximize relevance to adolescent participants in a high school setting (e.g., “I avoid parties” was modified “I avoid going to school social events”; “I avoid talking to authorities” was modified to “I avoid speaking with my teachers at school”). Participants rate agreement with each of the five items on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) Likert scale; higher total summed scores reflect greater social anxiety, indexed by avoidance of social interactions of various types. The SPIN and its subscales have shown adequate internal consistency and discriminant validity (Connor et al., 2000). Alphas were α = .79 at baseline and α = .80 at follow-up.

Engagement in conduct problem (antisocial) behaviors.

A measure of conduct problem behaviors, including violent and non-violent antisocial behaviors, was drawn from the Rochester Youth Development Study (Smith & Thornberry, 1994). Respondents indicated whether or not they had engaged in 13 different behaviors in the past thirty days. Items included: “Skipped classes without an excuse;” “Tried to steal or actually stole money or things;” “Hit someone with the idea of actually hurting them;” and “Damaged, destroyed, or marked up somebody else’s property on purpose.” Summed scores reflected the total number of conduct problem behaviors each participant had engaged in at baseline and follow-up.

Power analysis.

Before the start of data collection, a power analysis was conducted to determine appropriate sample size. The study was designed to achieve 80% power at = .05 to detect differences in primary and secondary study outcomes, assuming an effect size of d = 0.5 and a correlation of 0.4 between assessments across time-points. Final enrollment (n = 222) exceeded the targeted sample size (n = 150) to meet this objective.

Missing data and attrition.

There were no subject- or item-level missing data from baseline questionnaires. Figure 1 reports nonresponse rates at 4-month follow-up. Overall retention was high (95%). Likelihood of retention by 4-month follow-up did not differ by race or baseline levels of mindsets, depression, social anxiety, or conduct problems. However, fewer girls assigned to Growing Minds (92%) completed the four-month follow-up assessment than girls assigned to HEART (98%), χ2 = 4.18, p = .04. This difference was primarily due to the fact that 6 girls in the Growing Minds group (and only 1 girl in the HEART group) transferred school districts during the study. Because data were best characterized by the missing at random assumption, (Little & Rubin, 2014), whereby incomplete data arise due to observed trends in the sample, we used Full Estimation Maximum Likelihood (FIML) to address missing data concerns. FIML estimates parameters based on all available data, including cases with incomplete data, and yields unbiased results across wide-ranging parameter estimates that are comparable to those produced by multiple imputation (Schlomer, Bauman, & Card, 2010).

Analytic plan.

We conducted descriptive statistics to summarize sociodemographic variables and baseline levels of each outcome variable. We assessed pre-intervention equivalence on mental health symptoms via independent-samples t and tests, where appropriate, and we used linear regression to assess Growing Minds’ immediate, post-SSI effects on growth mindsets, relative to HEART. To assess four-month effects of Growing Minds on depressive symptom severity, clinically-significant elevations in depressive symptoms, social anxiety symptom severity, and number of conduct-related problem behaviors, we ran four generalized estimating equation (GEE) models using a 2 (intervention condition) × 2 (time; baseline, 4-month follow-up) design. GEE is an extension of linear mixed modeling that permits correlated repeated observations within subjects. It accommodates binary, continuous, and count outcomes and offers greater precision and power than alternate approaches, including ANCOVA (Hanley, Negassa, Edwardes, & Forrester, 2003). All four GEE models included time, intervention condition, and their interaction; covariates were school placement and student race/ethnicity (because the sample included only 10th grade girls, we did not adjust for age); and outcomes were depressive symptom scores (linear GEE model), elevations in depressive symptoms (binary logistic GEE model), social anxiety symptom scores (linear GEE model), and number of conduct-related problem behaviors (poisson log-linear GEE model, given an observed zero-inflated count distribution). A significant time X intervention condition interaction indicated that Growing Minds, relative to HEART, led to differential shifts in a mental health outcome. All models used an autoregressive error structure. Additionally, for continuous study outcomes (depressive and social anxiety symptom severity), we calculated effect sizes (ESs) using estimated marginal means, adjusting for covariates in each GEE model. These ESs compared mean gain scores (Cohen’s d) reflecting changes in each outcome from baseline to 4-month follow-up for youths receiving Growing Minds versus HEART. Positive Cohen’s d values indicated larger relative improvements for girls in the Growing Minds group.

Results

Sample characteristics and descriptive statistics.

Sample characteristics of the 222 participating adolescent girls are displayed in Table 1 by intervention condition. Based on a cut-off score of 11 on the SMFQ, 37.80% of the sample endorsed some degree of elevated depressive symptoms at baseline. The most common conduct problem behaviors endorsed at baseline were “skipped class without an excuse” (13.08%), “been loud or rowdy in a public place where somebody complained and you got in trouble (10.30%), and “hit someone with the idea of hurting them” (9.35%). No girls endorsed having “used a weapon or force to make someone give you money or things,” “attacked someone with a weapon with the idea of seriously hurting them,” or “sold illegal drugs or prescription medication.” No significant group differences emerged at baseline on sociodemographic factors or symptom levels, indicating that randomization was successful.

Manipulation check.

Compared to girls receiving HEART, girls who received Growing Minds reported greater increases from baseline to immediate post-SSI in growth mindsets of personality, F(2, 219) = 53.52, R2 = 0.13, p < .001 and in growth mindsets of intelligence, F(2, 218) = 63.79 R2 = 0.04, p < .001, controlling for baseline mindsets.

Depression severity outcomes.

With regard to youth depressive symptom severity, no significant effects emerged for time, Wald χ2 (1, N = 222) = 0.14, p = 0.71, or intervention condition, Wald χ2 (1, N = 222) = 0.18, p = 0.77. However, a significant time X intervention condition interaction emerged, Wald χ2 (1, N = 222) = -1.78, 95% CI [-3.47, -0.09], p = 0.039, d = 0.23 (reflecting group differences in mean gain scores, computed from estimated marginal means; see Table 2), such that girls who received Growing Minds showed larger reductions in depressive symptoms than did girls who received HEART. No significant effects on emerged for school or identified racial/ethnic group (ps > 0.09).

Table 2.

Estimated Marginal Means Generated From Generalized Estimating Equation Models Reflecting Mean (Standard Error) Levels of Mental Health Problems by Intervention Condition at Baseline and 4-Month Follow-Up

| Baseline depressive symptoms, M (SE) | 4-month depressive symptoms, M (SE) | Baseline social anxiety symptoms, M (SE) | 4-month social anxiety symptoms, M (SE) | Baseline conduct problem total, M (SE) | 4-month conduct problem total, M (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growing Minds | 9.95 (1.23) | 8.39 (1.21) | 18.82 (0.73) | 18.83 (0.75) | 0.67 (0.20) | 0.84 (0.24) |

| HEART | 9.66 (1.13) | 9.89 (1.17) | 18.99 (0.77) | 19.95 (0.73) | 0.43 (0.13) | 0.56 (0.15) |

Note. Estimated marginal means generated from GEE models reflecting M (SE) levels of mental health problems by intervention condition at baseline and 4-month follow-up.

Likewise, with regard to rates of depressive symptom elevations (SMFQ ≥ 11), no significant effects emerged for time, Wald χ2 (1, N = 222) = 0.23, p = 0.27, or intervention condition, Wald χ2 (1, N = 222) = 0.23, p = 0.40, and no significant effects emerged for school or identified racial/ethnic group (ps > 0.10). However, a significant time X intervention condition interaction emerged, Wald χ2 (1, N = 222) = -0.64, 95% CI [-1.21, -0.07], p = 0.033, d = 0.29 (reflecting Wald and p values), such that girls who received Growing Minds showed larger reductions in their odds of reporting elevated depressive symptoms than did girls who received HEART across the study period. More specifically, from baseline to four-month follow-up, the percentage of girls with SMFQ scores ≥ 11 shifted from 38.26% to 29.56% in the Growing Minds group and from 37.38% to 40.19% in the HEART group.

Social anxiety severity outcomes.

With regard to youth social anxiety symptom severity, no significant effects emerged for time, Wald χ2 (1, N = 222) = 0.14, p = 0.71, intervention condition, Wald (1, N = 222) = 0.18, p = 0.77, or their interaction, Wald χ2 (1, N = 222) = -1.78, 95% CI [-3.84, 0.28, p = 0.09, d = 0.21 (reflecting group differences in mean gain scores, computed from estimated marginal means). Although this ES was comparable in size to the ES for depressive symptom changes and in the predicted direction (favoring Growing Minds), we did not view this result as evidence supporting Growing Minds’ effects on social anxiety due to the non-significant p-value.

Conduct problem outcomes.

With regard to youth conduct problem behaviors, a significant effect emerged for time, Wald χ2 (1, N = 222) = 5.68, p = 0.014 but not for intervention condition, Wald χ2 (1, N = 222) =2.83, p = 0.09, or their interaction, Wald χ2 (1, N = 222) = -0.03, 95% CI [-0.44, 0.39, p = 0.91, d = .01 (reflecting group differences in mean gain scores, computed from estimated marginal means). Thus, girls’ conduct problem behaviors increased significantly across the follow-up period regardless of intervention condition.

Discussion

The present study evaluated whether a 45-minute, computerized SSI teaching growth mindsets of intelligence, personality, and self-regulation (called Growing Minds) reduced depressive symptoms, social anxiety symptoms, and conduct problem behaviors in adolescent girls living in rural regions of the United States. Compared to girls who received an attention-matched, active comparison SSI (called HEART, which taught healthy sexual behaviors), girls who received Growing Minds showed significantly greater improvements in self-reported depressive symptom severity (d = .23) and likelihood of reporting elevated versus non-elevated depressive symptoms (d = .29) from baseline to four-month follow-up. Four-month intervention effects were nonsignificant for self-reported social anxiety symptom severity, although the effect size was in the small-to-medium range numerically (d = .21) and in the hypothesized direction (favoring girls in Growing Minds). Four-month intervention effects were also nonsignificant for changes in self-reported conduct problem behaviors; conduct problem behaviors increased in girls across the study period regardless of intervention condition.

Contextualizing Growing Minds’ effects on depressive symptoms.

Growing Minds produced modest benefits for girls’ depressive symptoms: Effect sizes were in the small-to-medium range, representing mean sum-score group differences of 1.5 points on the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire. Nonetheless, results hold clinical utility and practical value for at least three reasons. First, rural adolescents with mental health needs are relatively unlikely to access any mental health treatment due to a host of difficult-to-modify logistical barriers. Thus, even modest symptom improvements following a free-of-charge, one-session, self-administered interventions suggest Growing Minds’ potential to support efficient clinical benefits, which may be magnified at the public-health scale. Second, findings support and extend a growing body of literature indicating that growth mindset SSIs can reduce adolescent depressive symptoms, both in high-symptom and unselected samples (Schleider & Weisz, 2018; Miu & Yeager, 2015). To our knowledge, this study is the first to observe such effects in a sample of rural adolescents, suggesting its acceptability and utility in a demographic group with chronically underserved mental health needs. Third, several design features of this study—including the use of an active comparison program that yielded benefits in other areas (e.g., positive sexual health attitudes) and the four-month follow-up period—lend support to the program’s promise. Overall effects of SSIs on youth mental health often reduce to near-zero following follow-ups of three months or more (Schleider & Weisz, 2017), and are significantly smaller comparison to active versus inactive controls (as is the case for full-length psychosocial interventions; Weisz et al., 2017). Growing Minds’ focus on modifying beliefs of particular relevance to adolescent stress-coping might help explain its relatively sustained effects, even when compared to an active control. Further, this SSI may be similarly helpful for depressive symptoms in community and high-symptom adolescents: In another trial, a computerized growth mindset SSI (versus an active, supportive therapy control) reduced depressive symptoms across a nine-month period in adolescents with elevated levels of internalizing psychopathology (Schleider & Weisz, 2018).

The SSI’s effects on depressive symptoms as especially notable because the need for more effective depression prevention and reduction strategies is critically high. Depression is now the leading cause of youth illness and disability worldwide (World Health Organization, 2014), yet the overall effect size for interventions targeting depression in youth has significantly decreased from 1960 to the present—for depression interventions for non-treatment-seeking youth in nonclinical settings (Weisz, Kuppens, et al., 2018, in press). Thus, Growing Minds and other SSIs targeting growth mindsets may serve as one (of many) valuable strategies for reversing these trends—one with high potential for scalability given its brevity and low-cost.

Understanding nonsignificant effects for social anxiety and conduct problems.

Growing Minds did not produce significant benefits for adolescent girls’ social anxiety or conduct problem behaviors in adolescent girls, relative to the control. There are several possible reasons for this result. With respect to social anxiety, the content of the comparison program may have played a role. HEART taught a number of clinically-relevant skills, including healthy, direct communication around challenging topics; relational and romantic competence skills; and personal assertiveness. This content, and the intervention’s positive effect on relevant outcomes (Widman et al., 2018), may have reduced our ability to detect positive effects for Growing Minds in this domain. However, it is equally possible that growth mindset interventions are more effective in reducing depressive symptoms than anxiety symptoms in adolescents—a possibility supported by a prior study testing a growth mindset SSI for adolescents with internalizing distress (Schleider & Weisz, 2018). Replications in non-clinical samples are needed to parse these competing possibilities.

With respect to conduct problems, it is notable that girls in both intervention groups reported increased externalizing behaviors over the course of the four-month follow-up period. This overall increase might reflect the fact that baseline study assessments occurred at the start of the school year—just following participants’ summer vacation, when there were fewer opportunities to engage in some of the most frequently-endorsed behaviors assessed here (e.g., skipped class). Still, Growing Minds did not buffer against this increase, which may relate to the program’s specific content. Growth mindset interventions that have previously reduced adolescent aggression have targeted mindsets regarding social hierarchies: the notion that students are not stuck being a “bully” or a “victim,” but rather, that social standing can change over time (Yeager et al., 2011, 2013). Growing Minds focused on different types of mindsets (regarding overall personality, self-regulation and intelligence), which may have rendered it less applicable to externalizing behaviors. However, the possibility remains that growth mindset SSIs might be less effective for adolescent conduct outcomes. Ascertaining this possibility will require replications including repeated assessments of internalizing and externalizing difficulties in youth.

Study Limitations.

Several study limitations warrant consideration. First, despite its brevity, Growing Minds included multiple components, teaching three different types of mindsets (intelligence, personality, self-regulation). Thus, the “active ingredients” of the SSI are impossible to disentangle. Previous studies have found that SSIs teaching just one type of mindset (personality) produced reductions in adolescent depression (Miu & Yeager, 2015; Schleider & Weisz, 2018), but we were unable to determine whether such was the case in the present study. Additional component-analysis evaluations may ascertain the necessity of teaching intelligence and/or self-regulation mindsets in reducing adolescent depression. Second, although adolescents who received HEART and Growing Minds were not informed of their intervention condition assignments, they did attend the same schools and might have learned from one another the differences between their assigned conditions. We were unable to evaluate the role that any “un-masking” of condition assignment might have played in present results. Third, data regarding girls’ access to other mental health supports were not collected, preventing us from examining the potential effects of receipt of concurrent psychological services during the study period. However, in a recent RCT, adolescents’ 9-month symptom reductions following a growth mindset SSI was unrelated to receipt of concurrent psychiatric and/or psychosocial intervention (Schleider & Weisz, 2018). Fourth, we focused on a fairly particular sample of non-treatment-seeking, racially diverse adolescent girls living in rural regions of the Southeastern United States. Thus, generalizability of present results to other samples, including to youth living in other rural U.S. regions, is unclear. Nonetheless, given historically low rates of mental health treatment-seeking/-access among this sociodemographic group, results may carry clinical utility for the population studied here. Lastly, it is worth noting that participants in this study were compensated for participating in the study, including the SSI. Additional field trials are needed to determine whether SSI effectiveness, and rates of SSI uptake, are maintained outside research contexts offering compensation.

Future Directions.

Present findings suggest promising next-steps for work in this area. For instance, as has been noted in past trials and reviews of SSIs (Schleider & Weisz, 2018; Schleider & Weisz, 2017; Schleider & Weisz, 2017b), some youths who receive evidence-based SSIs will still require further clinical attention. Future trials may test Growing Minds as an adjunct to multi-session EBTs. Instilling the belief that personal traits, and psychological symptoms, are malleable rather than fixed may be help buffer against dropout or improve homework compliance in the context of change-focused treatments delivered in clinical settings. Future studies may test this prospect directly.

Second, because the present study was a secondary data analysis, we were unable to test theoretically-driven change mechanisms underlying Growing Minds’ effects on mental health outcomes. Identifying theory-informed mechanisms of change—which may differ across different clusters of symptoms—may help strengthen the programs precision and potency. To our knowledge, only one study has evaluated possible mediators of a computerized growth mindset SSI on youth mental health outcomes: in at RCT of 96 youths with elevated internalizing symptoms, Schleider (2017) found that shifts in perceived behavioral and emotional control from baseline to three-month follow-up mediated the SSI’s effects on youth anxiety and depressive symptoms, respectively, at nine-month follow-up. Evaluating the strength and specificity of multiple potential change mechanisms for growth mindset SSIs—such as increases in inter-related cognitive protective factors, like perceived control or hopefulness—and testing these mediators with respect to internalizing and externalizing outcomes may help improve the program’s capacity to improve youth mental health trajectories.

Conclusions.

Adolescent girls are more likely to experience depression than same-aged boys, and rural adolescents’ mental health needs are chronically underserved due to logistical, financial, and stigma-related barriers. Results of this study suggest that a free-of-charge, non-stigmatizing SSI teaching growth mindsets may reduce depressive symptoms in rural adolescent girls across a four-month period. Symptom reductions were modest and did not extend to social anxiety or conduct problems; however, the critical importance of reducing adolescent depression in a scalable, cost-effective manner—especially among youths least likely to access care through traditional means—suggests this study’s value for clinical and public health. Our use of an active comparison program and four-month follow-up period, combined with a low attrition rate, supports the strength of observed effects. Future studies and replications may help ascertaining the specificity of observed effects to depression, relative to social anxiety and externalizing problems; the utility of Growing Minds as an adjunct to multi-session treatment; and whether testing theoretically-driven mediators might guide future efforts to enhance the program’s potency.

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development at the National Institutes of Health (R00 HD075654, K24 HD069204), the North Carolina State College of Humanities and Social Sciences Research Office, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI50410) and the University of North Carolina Communication for Health Applications and Interventions Core, a National Institutes of Health-funded facility (P30 DK56350, P30 CA16086).

References

- Alloy LB, Kelly KA, Mineka S, & Clements CM (1990). Comorbidity of anxiety and depressive disorders: A helplessness-hopelessness perspective In Maser JD & Cloninger CR (Eds.), Comorbidity of mood and anxiety disorders (pp. 499–543). Arlington, VA, US: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson E (1999). The power of self-persuasion. The American Psychologist, 54(11), 875–884. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT (1967). Depression: Clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bellamy GR, Bolin JN, & Gamm LD (2011). Rural Healthy People 2010, 2020, and Beyond. Family & Community Health, 34(2), 182–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette JL, Russell MV, Hoyt CL, Orvidas K, & Widman L (2017). An online growth mindset intervention in a sample of rural adolescent girls. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(3), 428–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussing R, Zima BT, Gary FA, & Garvan CW (2003). Barriers to detection, help-seeking, and service use for children with ADHD symptoms. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 30(2), 176–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byun S-Y, Meece JL, Irvin MJ, & Hutchins BC (2012). The Role of Social Capital in Educational Aspirations of Rural Youth. Rural Sociology, 77(3), 355–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu C-Y, Hong Y-Y, & Dweck CS (1997). Lay dispositionism and implicit theories of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(1), 19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor KM, Davidson JR, Churchill LE, Sherwood A, Foa E, & Weisler RH (2000). Psychometric properties of the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN). New self-rating scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 176, 379–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA (1986). A social information processing model of social competence in children In Perlmutter M (Ed.), Minnesota symposium on child psychology (Vol. 18, pp. 77–125). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont M, & Provost MA (1999). Resilience in Adolescents: Protective Role of Social Support, Coping Strategies, Self-Esteem, and Social Activities on Experience of Stress and Depression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28(3), 343–363. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert DD, Zarski AC, Christensen H, Stikkelbroek Y, Cuijpers P, Berking M, & Riper H (2015). Internet and computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in youth: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled outcome trials. PloS one, 10, e0119895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JA, Negassa A, Edwardes MDD, & Forrester JE (2003). Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: an orientation. American Journal of Epidemiology, 157(4), 364–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harowski K, Turner AL, LeVine E, Schank JA, & Leichter J (2006). From Our Community to Yours: Rural Best Perspectives on Psychology Practice, Training, and Advocacy. Professional Psychology Research and Practice, 37(2), 158–164. [Google Scholar]

- Harpaz-Rotem I, Leslie D, & Rosenheck RA (2004). Treatment retention among children entering a new episode of mental health care. Psychiatric Services, 55(9), 1022–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka SH, Zhang L, & Wells KB (2002). Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(9), 1548–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher KJ, & Gardner W (2017). Out of Sight, Out of Mind - Behavioral and Developmental Care for Rural Children. The New England Journal of Medicine, 376(14), 1301–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, & Wittchen H-U (2012). Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 21(3), 169–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konrad T, Ellis A, Thomas K, Holzer C, & Morrissey J (2009). County-Level Estimates of Need for Mental Health Professionals in the United States. Psychiatric Services, 60, 1323–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, & Rubin DB (2014). Missing Data in Experiments. Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Markovic A, Rose-Krasnor L, & Coplan RJ (2013). Shy children’s coping with a social conflict: The role of personality self-theories. Personality and Individual Differences, 54, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Mejia A, Calam R, & Sanders MR (2015). A pilot randomized controlled trial of a brief parenting intervention in low-resource settings in Panama. Prevention Science:The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 16(5), 707–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miu AS, & Yeager DS (2014). Preventing Symptoms of Depression by Teaching Adolescents That People Can Change. Clinical Psychological Science, 3(5), 726–743. [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Heflinger CA, Suiter SV, & Brody GH (2011). Examining Perceptions About Mental Health Care and Help-Seeking Among Rural African American Families of Adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(9), 1118–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Hilt LM (2013). Handbook of Depression in Adolescents. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Paunesku D, Walton GM, Romero C, Smith EN, Yeager DS, & Dweck CS (2015). Mind-set interventions are a scalable treatment for academic underachievement. Psychological Science, 26(6), 784–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perou R, Bitsko RH, Blumberg SJ, Pastor P, Ghandour RM, Gfroerer JC, … Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2013). Mental health surveillance among children--United States, 2005–2011. MMWR Supplements, 62(2), 1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson LR, Holbrook JR, Bitsko RH, Hartwig SA, Kaminski JW, Ghandour RM, … Boyle CA (2017). Differences in Health Care, Family, and Community Factors Associated with Mental, Behavioral, and Developmental Disorders Among Children Aged 2–8 Years in Rural and Urban Areas - United States, 2011–2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries, 66(8), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero C, Master A, Paunesku D, Dweck CS, & Gross JJ (2014). Academic and emotional functioning in middle school: the role of implicit theories. Emotion, 14(2), 227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum F, Weisz JR, & Snyder SS (1982). Changing the world and changing the self: A two-process model of perceived control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 5–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rural Information Center (U.S.) Beltsville, MD: USDA, National Agricultural Library, Rural Information Center; Revised and updated by Louise Reynnells. May, 2016. Original edition: 2006 by Patricia La Caille John Web: https://www.nal.usda.gov/ric/what-is-rural [Google Scholar]

- Schleider JL (2017). Effects of a single-session implicit theories of personality intervention on social stress recovery and long-term psychopathology in early adolescents. Unpublished dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Schleider JL, Abel MR, & Weisz JR (2015). Implicit theories and youth mental health problems: a random-effects meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 35, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleider JL, & Schroder HS (2018). Implicit theories of personality across development: impacts on coping, resilience, and mental health In Ziegler-Hill V & Shackelford TK (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Personality and Individual Differences. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Schleider JL, & Weisz JR (2015). Implicit Theories Relate to Youth Psychopathology, But How? A Longitudinal Test of Two Predictive Models. Psychiatry and Human Development, 47(4), 603–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleider JL, & Weisz JR (2016). Reducing risk for anxiety and depression in adolescents: Effects of a single-session intervention teaching that personality can change. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 87, 170–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleider JL, & Weisz JR (2017). Little Treatments, Promising Effects? Meta-Analysis of Single-Session Interventions for Youth Psychiatric Problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(2), 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleider JL, & Weisz JR (2018). A single-session growth mindset intervention for adolescent anxiety and depression: 9-month outcomes of a randomized trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 59(2), 160–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlomer GL, Bauman S, & Card NA (2010). Best practices for missing data management in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(1), 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortt AL, & Spence SH (2006). Risk and Protective Factors for Depression in Youth. Behaviour Change: Journal of the Australian Behaviour Modification Association, 23(01), 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Simon E, Driessen S, Lambert A, & Muris P (2019, in press). Challenging anxious cognitions or accepting them? Exploring the efficacy of the cognitive elements of cognitive behaviour therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy in the reduction of children’s fear of the dark. International Journal of Psychology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner AC, & Slifkin RT (2007). Rural/urban differences in barriers to and burden of care for children with special health care needs. The Journal of Rural Health: Official Journal of the American Rural Health Association and the National Rural Health Care Association, 23, 150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalley KB, Bryant Smalley K, Thresa Yancey C, Warren JC, Naufel K, Ryan R, & Pugh JL (2010). Rural mental health and psychological treatment: a review for practitioners. Journal of Clinical Psychology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalley KB, Warren JC, & Barefoot KN (2016). Differences in health risk behaviors across understudied LGBT subgroups. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 35(2), 103–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, Cotter KL, Robertson CIB, & Guo S (2012). Anxiety and Aggression in Rural Youth: Baseline Results from the Rural Adaptation Project. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 44(4), 479–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swearer SM, & Hymel S (2015). Understanding the psychology of bullying: Moving toward a social-ecological diathesis–stress model. American Psychologist, 70(4), 344–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner N, Joinson C, Peters TJ, Wiles N, & Lewis G (2014). Validity of the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire in late adolescence. Psychological Assessment, 26(3), 752–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallury KD, Jones M, & Oosterbroek C (2015). Computerized Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Anxiety and Depression in Rural Areas:A Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17, e139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Stoep A, McCauley E, Thompson KA, Herting JR, Kuo ES, Stewart DG, … Kushner S (2005). Universal Emotional Health Screening at the Middle School Transition. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 13(4), 213–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb TL, Miles E, & Sheeran P (2012). Dealing with feeling: a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of strategies derived from the process model of emotion regulation. Psychological Bulletin, 138, 775–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Francis SE, & Bearman SK (2010). Assessing secondary control and its association with youth depression symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 883–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Kuppens S, Ng MY, Eckshtain D, Ugueto AM, Vaughn-Coaxum R, … Fordwood SR (2017). What five decades of research tells us about the effects of youth psychological therapy: A multilevel meta-analysis and implications for science and practice. The American Psychologist, 72(2), 79–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widman L, Golin CE, Kamke K, Burnette JL, & Prinstein MJ (2018). Sexual Assertiveness Skills and Sexual Decision-Making in Adolescent Girls: Randomized Controlled Trial of an Online Program. American Journal of Public Health, 108(1), 96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widman L, Golin CE, Kamke K, Massey J, & Prinstein MJ (2017). Feasibility and acceptability of a web-based HIV/STD prevention program for adolescent girls targeting sexual communication skills. Health Education Research, 32(4), 343–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widman L, Golin CE, Noar SM, Massey J, & Prinstein MJ (2016). ProjectHeartforGirls.com: Development of a Web-Based HIV/STD Prevention Program for Adolescent Girls Emphasizing Sexual Communication Skills. AIDS Education and Prevention: Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education, 28(5), 365–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager DS, & Dweck CS (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47(4), 302–314. [Google Scholar]

- Yeager DS, Lee HY, & Jamieson JP (2016). How to Improve Adolescent Stress Responses: Insights From Integrating Implicit Theories of Personality and Biopsychosocial Models. Psychological Science, 27(8), 1078–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager DS, Miu AS, Powers J, & Dweck CS (2013). Implicit theories of personality and attributions of hostile intent: a meta-analysis, an experiment, and a longitudinal intervention. Child Development, 84(5), 1651–1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager DS, Trzesniewski KH, Tirri K, Nokelainen P, & Dweck CS (2011). Adolescents’ implicit theories predict desire for vengeance after peer conflicts: correlational and experimental evidence. Developmental Psychology, 47(4), 1090–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]