Abstract

Cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is associated with an altered gut-liver-brain axis. Fecal microbial transplant (FMT) after antibiotics improves outcomes in HE, but the impact on brain function is unclear. The aim of this study is to determine the effect of colonization using human donors in germ-free (GF) mice on the gut-liver-brain axis. GF and conventional mice were made cirrhotic using carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) and compared to controls in GF and conventional state. Additional GF mice were colonized with stool from controls (Ctrl-Hum) and patients with cirrhosis (Cirr-Hum). Stools from patients with HE cirrhosis after antibiotics were pooled (pre-FMT). Stools from the same patients 15 days post-FMT from a healthy donor were also pooled (post-FMT). Sterile supernatants were created from pre-FMT and post-FMT samples. GF mice were colonized using stools/sterile supernatants. For all mice, frontal cortex, liver, and small/large intestines were collected. Cortical inflammation, synaptic plasticity and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) signaling, and liver inflammation and intestinal 16s ribosomal RNA microbiota sequencing were performed. Conventional cirrhotic mice had higher neuroinflammation, microglial/glial activation, GABA signaling, and intestinal dysbiosis compared to other groups. Cirr-Hum mice had greater neuroinflammation, microglial/glial activation, and GABA signaling and lower synaptic plasticity compared to Ctrl-Hum mice. This was associated with greater dysbiosis but no change in liver histology. Pre-FMT material colonization was associated with neuroinflammation and microglial activation and dysbiosis, which was reduced significantly with post-FMT samples. Sterile pre-FMT and post-FMT supernatants did not affect brain parameters. Liver inflammation was unaffected.

Conclusion:

Fecal microbial colonization from patients with cirrhosis results in higher degrees of neuroinflammation and activation of GABAergic and neuronal activation in mice regardless of cirrhosis, compared to those from healthy humans. Reduction in neuroinflammation by using samples from post-FMT patients to colonize GF mice shows a direct effect of fecal microbiota independent of active liver inflammation or injury.

Keywords: fecal microbial transplant, neuroinflammation, hepatic encephalopathy, germ-free

Patients with cirrhosis have a perturbed gut-liver-brain axis that can influence the development and progression of hepatic encephalopathy (HE)(1). Patients suffering from HE often have repeated episodes that can result in cumulative changes, leading to persistent cognitive impairment.(2, 3) These are often not completely halted by the current standard of care, such as rifaximin or lactulose.(4, 5)

The pathophysiology of HE is multifactorial, with hyperammonemia, neuroinflammation, systemic inflammation, bile acid changes, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transmission being implicated.(6, 7) In the carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) rodent model of cirrhosis, there is evidence of neuroinflammation in conventional mice with cirrhosis that is not present in the germ-free (GF) state, implicating the microbiota.(8) The specific changes in the gut-liver-brain axis brought on by bacterial colonization are unclear and could offer a pathophysiological insight into the contribution of the gut toward neuroinflammation in the absence of cirrhosis.

Prior studies have demonstrated that specific interventions, such as fecal microbial transplant (FMT), may improve brain functioning in recurrent HE and other alterations of the gut-brain axis.(9–11) Studies of FMT in diseases other than cirrhosis have also demonstrated that sterile supernatants could also benefit clinical outcomes.(12) However, the effect of gut microbiota compared to their sterile supernatants on brain function is unclear in cirrhosis.

Our aims were to (1) determine the impact of differential colonization with stools from patients with cirrhosis versus healthy controls of GF mice on brain inflammation, synaptic plasticity, and GABAergic activation as a reflection of the gut-brain axis; and (2) define the impact of transfer of sterile supernatants compared to entire stool from patients with cirrhosis before and after FMT on brain inflammation in GF mice. We hypothesized that brain inflammation in cirrhosis responds differentially based on the source of colonization, which is the reason for improvement after FMT in humans with HE, and that sterile supernatants from FMT recipients would have a similar impact on brain inflammation as the entire stool.

Methods:

Experimental design:

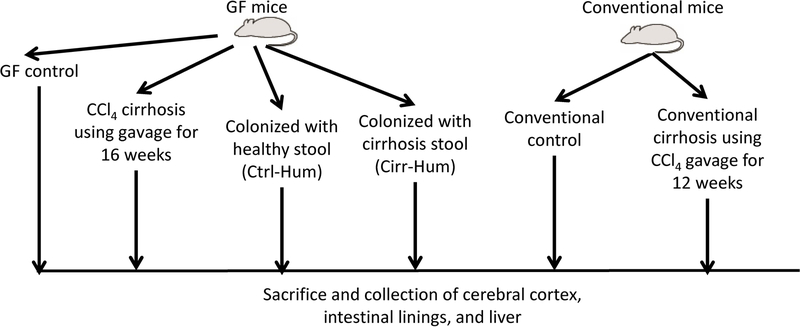

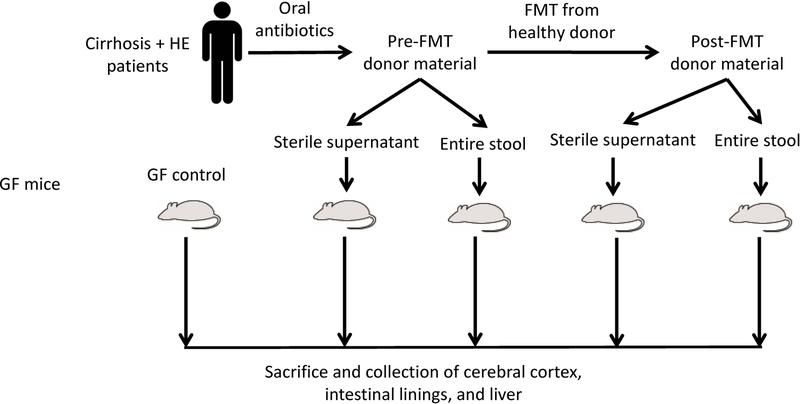

The study was divided into two parts. The goal of part 1 was to define the role of differential humanization with patients with cirrhosis and minimal HE or healthy subjects’ stool on brain inflammation and compare the resulting neuroinflammation to that occurring in conventional and GF mice with experimentally induced cirrhosis (Fig. 1A). The goal of part 2 was to determine the changes in neuroinflammation in GF mice before and after FMT or transfer of sterile fecal supernatants from the stools of patients with cirrhosis and recurrent HE (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Schematic of experiments. (A) Design of selective colonization experiment. (B) Fecal microbiota transplant experimental design. Abbreviations: CCl4, carbon tetrachloride; Cirr-Hum, mice colonized with stool from patients with cirrhosis with minimal hepatic encephalopathy; Ctrl-Hum, mice colonized with stool from healthy humans; FMT, fecal microbial transplant; GF, germ-free; HE, hepatic encephalopathy.

Selective colonization experiment:

Conventional mice: We used 10-week-old C57BL/6 mice in conventional housing conditions. Half underwent CCl4 gavage (1.0 mL/kg) twice a week for 12 weeks under careful monitoring per our prior protocols.(8) The CCl4 model was used as a model for patients with cirrhosis due to toxic-inflammatory etiologies. We did not use the bile duct ligation model, which reflects cholestatic cirrhosis etiologies, because the diversion of bile itself can cause microbial changes.(13) At week 12, the mice underwent necropsy (Fig. 1A).

GF mice: We used 10-week-old C57BL/6 mice in the National Gnotobiotic Rodent Resource Center (NGRRC) at University of North Carolina that were divided into four groups of at least six to eight mice each. Group 1 remained GF without cirrhosis, and group 2 underwent CCl4 gavage, as mentioned above, to develop cirrhosis in the GF condition. The remaining two groups underwent colonization using human donors. Group 2 was sacrificed at week 16 as the time frame to develop cirrhosis using CCl4 gavage in the GF state.(8)

Human donors:

We created pooled stool aliquots from the donors with cirrhosis and healthy donors, whose samples were obtained after written informed consent (Supporting Data). None of the human donors were on antibiotics or probiotics for the last 3 months or had alcohol use disorder. All donors had a comparable dietary intake for the prior week. The mixing was performed at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) clinical laboratories, and the stool was frozen in aliquots that were transported to NGRRC for selective colonization.

Cirrhosis:

A group of 10 patients with cirrhosis without decompensation and who were therefore not on beta-blockers, diuretics, or HE therapies were included. Patients provided stool that was frozen and then mixed to form pooled aliquots. All cirrhotic patients had evidence of minimal HE on the psychometric hepatic encephalopathy score (PHES) performed within a month of stool donation(5).

Healthy controls:

A group of 10 healthy controls who were age and gender balanced to patients with cirrhosis were included. All controls were free of chronic diseases, had normal cognitive performance on PHES within a month of stool donation, and were not on any medications. Stool was collected and mixed to form aliquots for colonization.

Pre-FMT and post-FMT experiment:

As published, 10 patients with cirrhosis with recurrent HE on lactulose and rifaximin were treated with 5 days of broad-spectrum antibiotics (amoxicillin, metronidazole, and ciprofloxacin) followed by 90 mL of an FMT enema from a single donor enriched in Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae.(9) (Supporting Data). We collected stool from all 10 patients after antibiotics before they received FMT and mixed them to form the pooled pre-FMT stool inoculum. Samples collected from FMT recipients 15 days post-FMT were collected and pooled to form the post-FMT inoculum (Fig. 1B).

Stool collection from human donors:

Fresh stool from the subjects was collected and individually mixed with pre-reduced dilution solution under anerobic conditions. The samples were centrifuged at 16,000xg for 5 minutes to remove sediment to prevent clogging of gavage tubes. Finally, all samples from each category (controls, cirrhosis, pre-FMT, post-FMT) were pooled. We created aliquots of 0.5gm of mixed stool pellets, which were stored at –80°C. Before colonization, these were thawed, resuspended in 1.5ml of sterile PBS per tube/pellet and then gavaged 0.2ml per mouse per day. In our prior studies, stool treated in this manner, once thawed and inoculated, could effectively colonize GF mice without complications and with good retention of bacterial profiles.(14, 15) We used pooled material as the donor material to avoid interindividual variations and to reduce the analytic complexity, and logistic challenges.

Preparation of sterile supernatant:

An aliquot of each of the pooled fecal suspensions generated above was further centrifuged at 15,000g for 20 minutes to pellet whole cells. The supernatant fluid was filtered and sterilized by passage through a 0.22-micron filter to remove bacteria and other microorganisms. Sterile supernatants were monitored for contamination by inoculating on Brain Heart Infusion culture plates under aerobic and anerobic conditions and gram-stained for examination under oil immersion microscopy (1,000×). We gavaged 0.2ml of supernatant per mouse per day.

Using established protocols that the NGRRC has developed and published, intact fecal material was transferred to 10–15-week-old GF C57BL/6 mice (both male and female) by daily gavage for 3 days (6–8 mice/group).(14–16) The mice were observed in sterile individually filtered cages for 15 days after which they were harvested. A similar group of GF mice housed received filtered sterile supernatants by daily gavage for 3 days and were sacrificed after the last gavage. This duration has proven adequate to ensure satisfactory humanization and changes within mice in our prior studies.(15) Mice receiving different donor materials were housed in separate cages to prevent cross-contamination, and guidelines were followed.(16) At least six mice were used in each experiment.

At sacrifice, we extracted the small and large intestinal mucosa, liver, and frontal cortices. In the brain, we studied messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of (1) neuroinflammation (interleukin [IL]-6, IL-1β, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 [MCP1]); (2) glial/microglial activation (ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 [IAB1] and glial fibrillary acidic protein [GFAP]); (3) brain regeneration (brain-derived neurotrophic factor [BDNF]) and (4) GABA physiology (GABA A receptor, subunit B1 [GABRAB1] and gamma 1 [GABRAG1]).

Liver histology was studied by a pathologist who was blinded to the assignment. Microbiota analysis details in Supporting data.

Approvals were obtained from institutional review boards (IRBs) at VCU and McGuire VA Medical Center and from Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUCs) at University of North Carolina Chapel Hill and VCU before study initiation. All animals received humane care according to the criteria outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Results:

Selective colonization experiment:

Differential colonization results in cortical inflammation in GF mice:

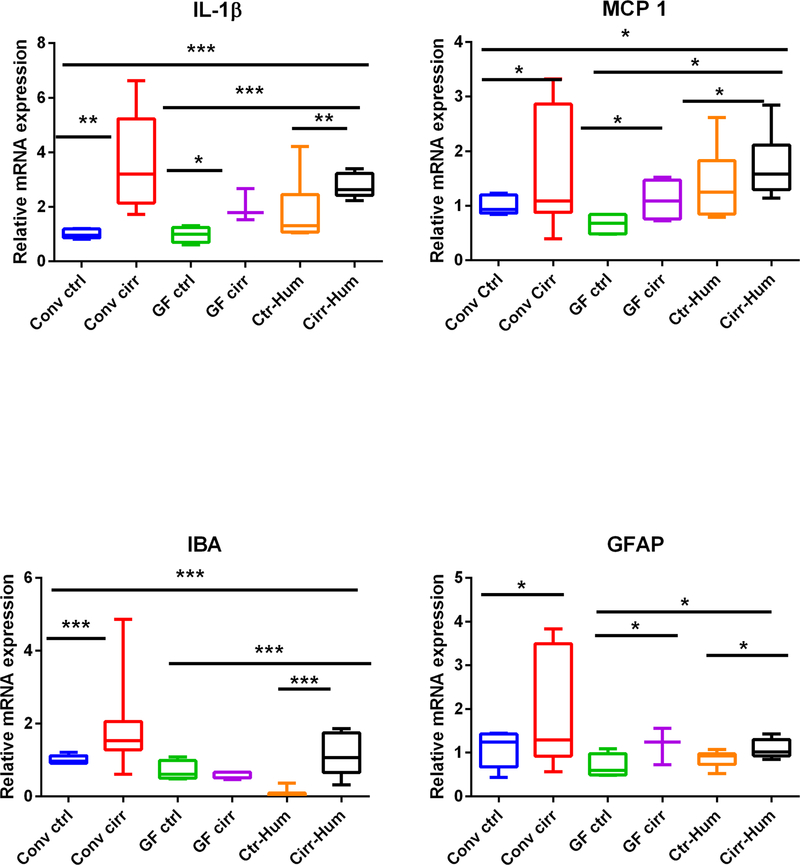

We found a significant increase in mRNA expression of IL-1β and MCP1 in the conventional cirrhotic mice compared to conventional controls, GF controls, and GF mice. In addition, IL-1β and MCP1 expression was higher in the ex-GF mice colonized with stool from patients with cirrhosis compared to control subjects’ stool. This pattern was also repeated with IBA and GFAP expression (Fig. 2A–D). GF cirrhotic mice had a higher mRNA expression of GFAP, IL-1β, and MCP1 compared to GF controls. Importantly, there was no statistically significant difference in IL-1β, MCP1, GFAP, and IBA expression between conventional experimentally cirrhotic mice and noncirrhotic ex-GF mice colonized with stool from patients with cirrhosis.

FIG. 2.

Expression of mRNA in mouse frontal cortex. (A) IL-1β expression was highest in conventional cirrhotic mice compared to the rest and was even higher in Cirr-Hum mice compared to Ctrl-Hum and other GF mice. (B) Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1) expression was again highest in conv cirr group and in Cirr-Hum frontal cortex. (C) Ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (IBA1) expression was also highest in conv cirr group and in Cirr-Hum frontal cortex. (D) Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) expression was highest in conv cirr group and in Cirr-Hum frontal cortex. (E) Neuronal N Fox 3 (NeuN/Fox3) expression was highest in conv cirrhosis compared to controls. No other significant differences were seen. (F) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) was only found to be high in Ctrl-Hum mice compared to the remaining GF mice. No other changes were seen. (G) GABA receptor, subunit B1 (GABAB1) was again highest in conv cirrhosis mice and in Cirr-Hum mice compared to the rest. (H) GABA receptor, subunit gamma 1 (GABAG1) expression was highest in Cirr-Hum and Ctrl-Hum mice compared to the remaining GF groups. Data are shown as median and 95% CI with comparisons using Kruskal-Wallis or Mann-Whitney tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Abbreviations: CCl4, carbon tetrachloride; Cirr-Hum, germ-free mice colonized with stool from patients with cirrhosis with minimal hepatic encephalopathy; conv cirr, conventional cirrhosis mice using CCl4 gavage; conv ctrl, conventional control mice; GF cirr, cirrhosis under germ-free conditions using Ctrl-Hum, germ-free mice colonized with stool from healthy humans; GF ctrl, germ-free control mice.

Although there was no difference in neuronal-N-Fox 3 (NeuN/Fox3) expression among the GF groups, regardless of humanization, there was a higher expression in conventional cirrhotic mice compared to the rest of the groups (Fig. 2E). On the other hand, there was a higher BDNF in mice who received healthy control stool compared to all other categories (Fig. 2F). GABRAB1 and GABRAG1 expression was higher in conventional mice compared to the GF and humanized groups but was relatively higher in the colonized groups (Fig. 2G,H).

Liver:

All mice with conventional and GF cirrhosis had development of cirrhotic nodules, as expected, at the time of sacrifice after CCl4. Control mice, either in GF or conventional condition, did not exhibit signs of fibrosis or inflammatory or fatty change (representative images in Supporting Fig. S2). Ctrl-Hum and Cirr-Hum mice did not show signs of inflammation, fibrosis, or fatty change.

Microbiota changes:

None of the specimens and cultures obtained from GF mouse controls, GF induced cirrhosis or those colonized with GF supernatants pre-FMT and post-FMT had any growth, as expected.

Changes in cirrhosis compared to control microbiota:

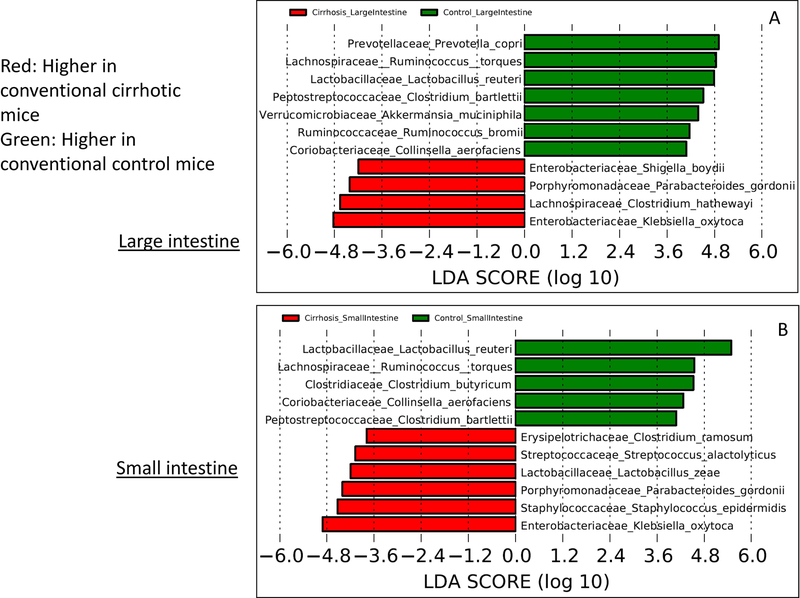

There was a higher relative abundance of potentially pathogenic families, such as Staphylococcaceae, Streptococcaceae, and Enterobacteriaceae, in the intestinal linings of cirrhotic compared to control mice. This was complemented by lower beneficial taxa, such as Bifidobacteriaceae and Lachnospiraceae (Table 1). At the species level, this was associated with higher Akkermansia muciniphila, Lactobacillus reuteri, and Ruminococcus torques and bromii and lower Shigella and Klebsiella spp. in control compared to cirrhotic mice in the large intestine (Fig. 3A). In the small intestine, similarly, species belonging to Lactobacillaceae and Lachnospiraceae were higher and species belonging to Porphyromonadaceae and Staphylococcaceae were lower in controls compared to cirrhotic mice (Fig. 3B).

TABLE 1.

LEfSe Changes at the Family Level for the Selective Colonization Experiment

| Higher in conventional control | Higher in conventional cirrhosis | |

|---|---|---|

| Small intestine | Actinobacteria_Coriobacteriaceae | Actinobacteria_Micrococcaceae Bacteroidetes_Bacteroidaceae Cyanobacteria_Chloroplast Firmicutes_Staphyloccaceae Firmicutes_Streptococcaceae Proteobacteria_Enterobacteriaceae |

| Large intestine | Actinobacteria_Bifidobacteriaceae Actinobacteria_Coriobacteriaceae Bacteroidetes_Rikenellaceae Bacteroidetes_Prevotellaceae Firmicutes_Heliobacteriaceae Firmicutes_Lachnospiraceae Firmicutes_Peptostreptococcaceae Firmicutes_Peptococcaceae Firmicutes_Clostridiaceae Tenericutes_Anaeroplasmataceae |

Actinobacteria_Propionibacteriaceae Firmicutes_Streptococcaceae Bacteroidetes_Marinillabiliaceae Proteobacteria_Methylobacteriaceae Proteobacteria_Enterobacteriaceae Verrucomicrobia_Verrucomicrobiaceae |

| Higher in conventional cirrhotic mice | Higher in mice colonized with cirrhosis stool | |

| Small intestine | Bacteroidetes_Bacteroidaceae Bacteroidetes_Porphyromonadaceae Bacteroidetes_Marinillabiliaceae Cyanobacteria_Chloroplast Firmicutes_Lactobacillaceae Firmicutes_Streptococcaceae Proteobacteria_Enterobacteriaceae Proteobacteria_Methylobacteriaceae |

Actinobacteriaceae_Coriobacteriacae Firmicutes_Lachnospiraceae Firmicutes_Eubacteriaceae Firmicutes_Peptococcaceae Firmicutes_Syntrophomonadaceae Proteobacteria_Burkholderiaceae |

| Large intestine | Bacteroidetes_Marinillabiliaceae Bacteroidetes_Prevotellaceae Bacteroidetes_Bacteroidales Incertae Sedis Bacteroidetes_Flammeovirgaceae Firmicutes_Streptococcaceae Proteobacteria_Enterobacteriaceae Proteobacteria_Methylobacteriaceae |

Actinobacteria_Bifidobacteriaceae Actinobacteriaceae_Coriobacteriacae Bacteroidetes_Rikenellaceae Firmicutes_Syntrophomonadaceae Firmicutes_Erysipelothricaceae Firmicutes_Lachnospiraceae Firmicutes_Ruminococcaceae Firmicutes_Peptococcaceae |

| Higher in mice colonized with control stool | Higher in mice colonized with cirrhosis stool | |

| Small intestine | Actinobacteria_Bifidobacteriaceae Firmicutes_Streptococaceae Firmicutes_Carnobacteriaceae Proteobacteria_Sutterellaceae |

Actinobacteria_Coriobacteriaceae Firmicutes_Eubacteriaceae Firmicutes_Peptococcaceae Firmicutes_Enterococcaceae Firmicutes_Erysipelothricaceae Firmicutes_Syntrophomonadaceae |

| Large intestine | Actinobacteria_Bifidobacteriaceae Bacteroidetes_Bacteroidaceae Firmicutes_Streptococaceae Firmicutes_Carnobacteriaceae Proteobacteria_Burkholderiaceae Proteobacteria_Sutterellaceae |

Actinobacteria_Coriobacteriaceae Firmicutes_Eubacteriaceae Firmicutes_Ruminococcaceae Firmicutes_Peptococcaceae Firmicutes_Erysipelothricaceae |

Higher in one group indicates lower in the group it is being compared to on LEfSe. Taxa are presented as Phylum_Family.

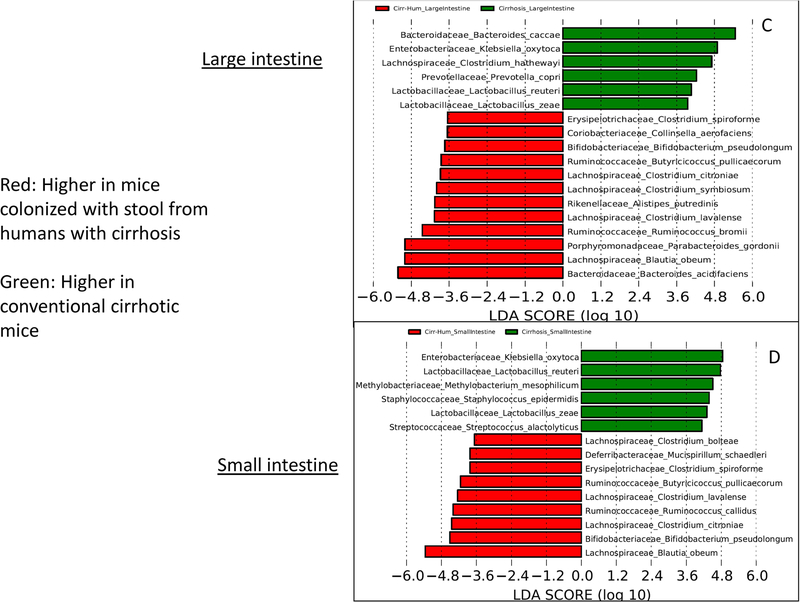

FIG. 3.

Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) comparisons of microbiota at the species level using QIIME2. x axis shows the score that differentiates between the two groups being compared. A higher LDA toward one color indicates that taxon is higher in that group and lower in the group it is being compared to. (A) Comparison of conventional cirrhosis (red) to conventional control (green) mouse large intestinal mucosal microbiota. (B) Comparison of conventional cirrhosis (red) to conventional control (green) mouse small intestinal mucosal microbiota. (C) Comparison of conventional cirrhosis (green) to mice colonized with stool from cirrhotic humans with minimal hepatic encephalopathy (Cirr-Hum, red) in the mouse large intestinal mucosal microbiota. (D) Comparison of conventional cirrhosis (green) to mice colonized with stool from cirrhotic humans (Cirr-Hum, red) in the mouse small intestinal mucosal microbiota. (E) Comparison of large intestinal microbiota of mice colonized with stool from cirrhotic humans (Cirr-Hum, red) to those colonized with stool from healthy controls (Ctrl-Hum, green). (F) Comparison of small intestinal microbiota of mice colonized with stool from cirrhotic humans (Cirr-Hum, red) to those colonized with stool from healthy controls (Ctrl-Hum, green).

Conventional cirrhosis compared to Cirr-Hum mice:

This comparison, performed to study the impact of cirrhosis, demonstrated that mice with experimentally induced cirrhosis had higher Enterobacteriaceae, Streptococcaceae, Porphyromonadaceae, and Lactobacillaceae and lower Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, and Bifidobacteriaceae compared to mice that were simply colonized with stool from patients with cirrhosis. This was also reflected in the species changes with higher intestinal Ruminococcaceae (Butyricicoccus and Ruminococcus) and Lachnospiraceae (Clostridial spp. and Blautia) and lower Klebsiella oxytoca and Prevotella copri in those colonized with stool from the patients with cirrhosis compared to cirrhotic mice (Fig. 3C,D). Ctrl-Hum and Cirr-Hum mucosal changes were largely similar between small and large intestine within each category. However, the differences between Ctrl-Hum and Cirr-Hum were related to higher Bifidobacteriaceae and Streptococcaceae and lower Enterococcaceae and other Firmicutes members in Ctrl-Hum compared to Cirr-Hum. At the species level, the changes were relatively modest, with Ruminococcus and Bifidobacterium species increased in both groups (Fig. 3E,F).

Pre-FMT and post-FMT experiments:

FMT before and after brain changes in GF mice:

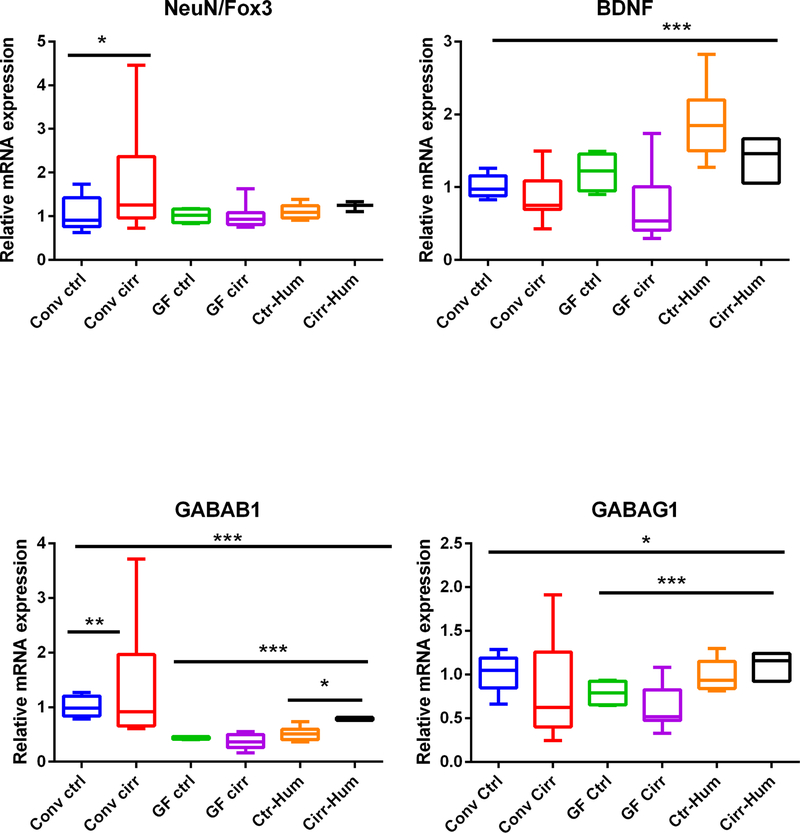

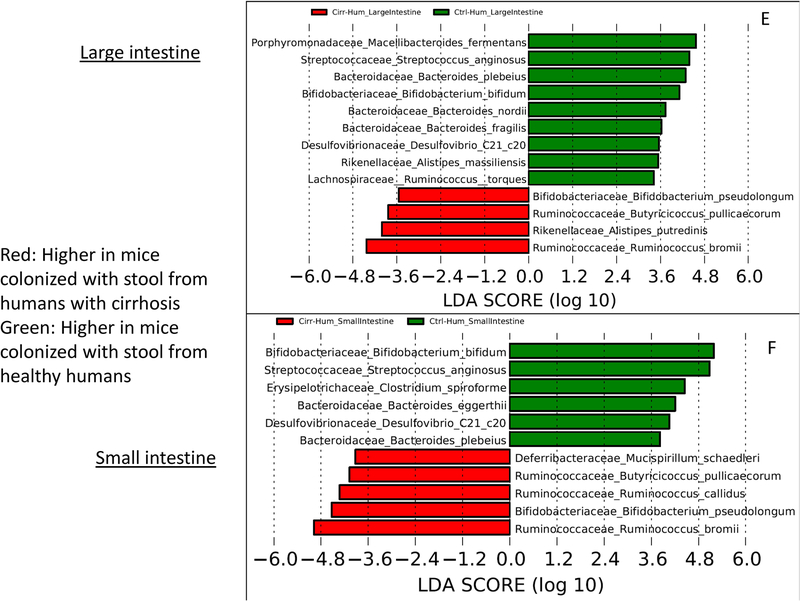

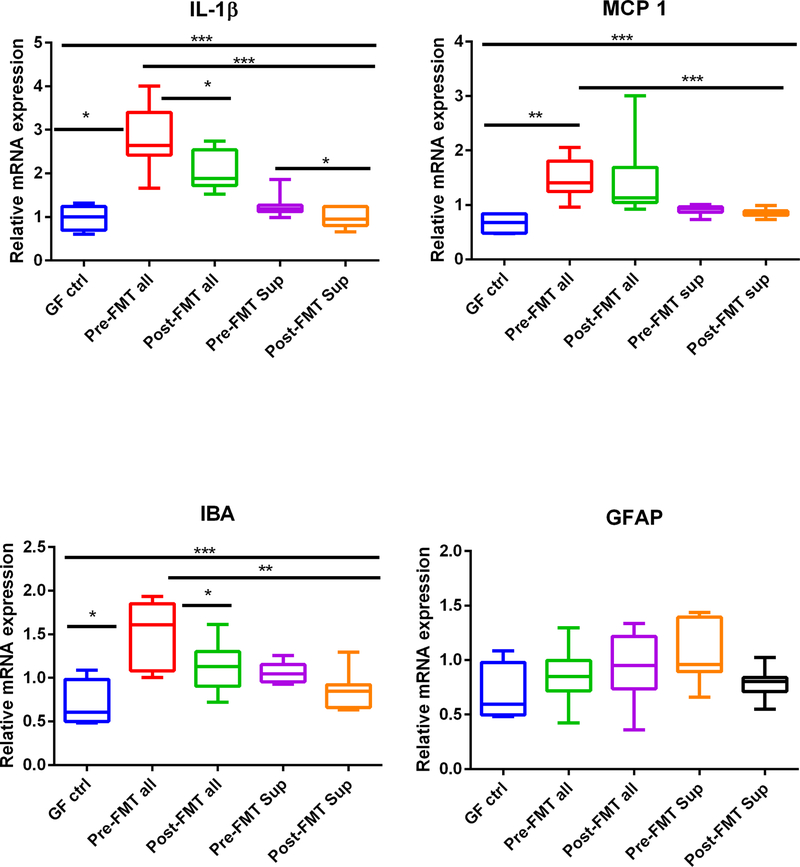

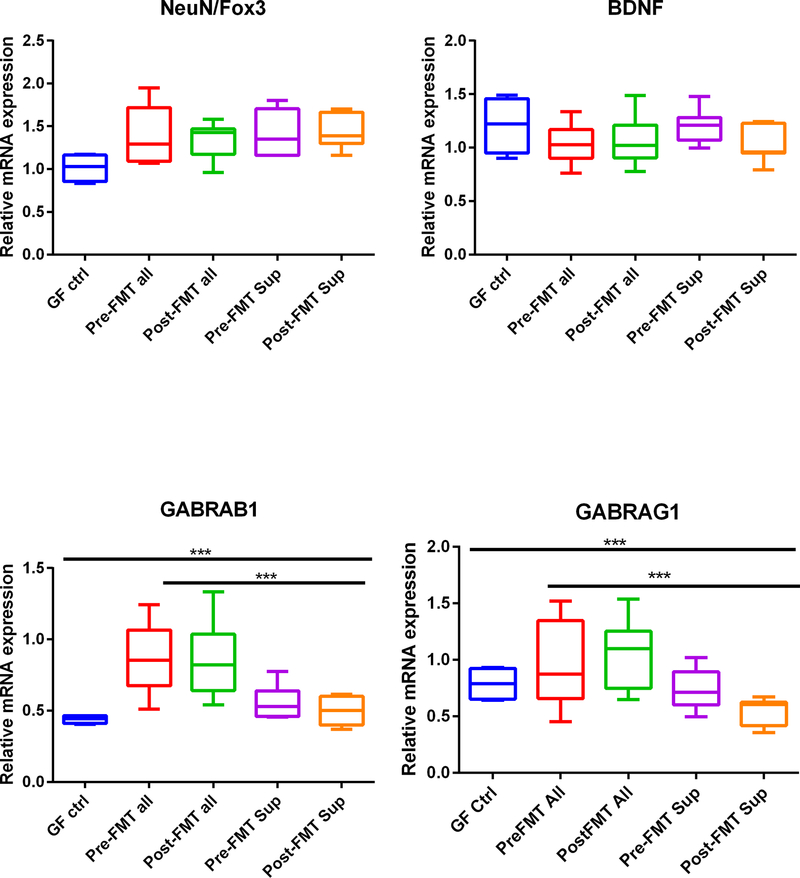

There was a higher expression of IL-1β, MCP1, IBA, GABAB1, and GI mRNA in mice colonized with the entire FMT material compared to GF controls and GF mice receiving the supernatants regardless of pre-FMT and post-FMT state (Fig. 4A–D,G–H). In all instances, the mice receiving the supernatants were like the GF control state. IBA and IL-1β expression was significantly lower in the frontal cortices of mice that received post-FMT compared to pre-FMT samples (Fig. 4A,C). Regardless of pre-FMT and post-FMT, there was greater GABAG1 and GABAB1 expression in those who received the entire stool (Fig. 4G,H). GFAP, NeuN/Fox3, and BDNF expression did not change between any group significantly (Fig. 4D–F).

FIG. 4.

Expression of mRNA in mouse frontal cortex. (A) IL-1β expression was highest in pre-FMT all mice, which reduced after post-FMT. This was higher than other GF groups, including the supernatants. The pre-FMT supernatant was also associated with higher IL-1β compared to post-FMT supernatants. (B) Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1) expression was higher in pre- and post-FMT all compared to GF mice regardless of whether they were given the supernatants or not. (C) Ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (IBA1) expression was highest in pre-FMT all mice, which reduced post-FMT. This was higher than other GF groups, including the supernatants. (D) Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) expression was not different between groups. (E) Neuronal N Fox 3 (NeuN/Fox3) expression was not different between groups. (F) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) was not different between groups. (G) GABA receptor, subunit B1 (GABAB1) was higher in pre- and post-FMT all compared to GF mice regardless of whether they were given the supernatants or not. (G) GABA receptor, subunit gamma 1 (GABAG1) expression was higher in pre- and post-FMT all compared to GF mice regardless of whether they were given the supernatants or not. Data are shown as median and 95% CI with comparisons using Kruskal-Wallis or Mann-Whitney tests, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Abbreviations: GF ctrl, germ-free control mice; post-FMT all, mixed stool from the same patients who gave stool for pre-FMT 15 days after FMT with a healthy human; post-FMT sup, germ-free supernatant of the stools in post-FMT all; pre-FMT all, mixed stool from patients with cirrhosis after antibiotics but before fecal microbial transplant (FMT); pre-FMT sup, germ-free supernatant derived from the stools from patients in pre-FMT all.

Liver:

Neither the pre-FMT nor post-FMT stools resulted in significant inflammation, steatosis, or fibrosis (representative H&E and trichrome stains in Supporting Fig. S3 collated data). Similarly, no significant liver pathology was noted when the corresponding sterile supernatants were introduced in the GF mice (representative images in Supporting Fig. S3).

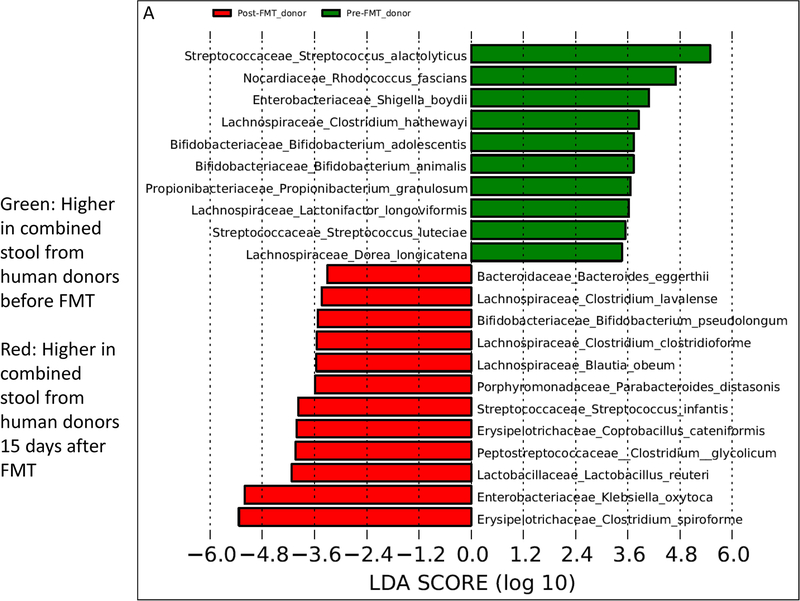

Microbiota changes pre- versus post-FMT:

The donor stools from pre-FMT subjects and the same patients’ post-FMT exhibited significant changes. Prominent among these differences were higher Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, Lactobacillaceae, and Enterobacteriaceae and lower Enterococcaceae and Streptococcaceae in the post-FMT human donor stools compared to pre-FMT values (Table 2). At the species level, the pre-FMT donor material contained higher relative abundance of Shigella boydii, Streptococcus spp., and components of Lachnospiraceae (Lactonifactor and Dorea) and Bifidobacteria (Bifidobacterium animalis and adolescentis). After FMT, where the donor enriched in Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae was introduced in the humans, there were significantly higher species belonging to Lachnospiraceae (Blautia and Clostridial spp.), Bifidobacteria (Bifidobacterium pseudolongum), Klebsiella oxytoca, Bacteroides eggerthii, and Lactobacillus reuteri (Fig. 5A).

TABLE 2.

LEfSe Differences Between Pre- Versus Post-FMT Groups at the Family Level

| Higher in pre-FMT group | Higher in post-FMT group | |

|---|---|---|

| Donor material | Actinobacteria_Micrococcaceae Actinobacteria_Propionibacteriacea Cyanobacteria_Chloroplast Firmicutes_Enterococcaceae Firmicutes_Streptococcaceae Firmicutes_Leuconostocaceae Firmicutes_Carnobacteriaceae Proteobacteria_Sphingomonadaceae Verrucomicrobia_Verrrucomicrobiaceae |

Firmicutes_Lachnospiraceae Firmicutes_Ruminococcaceae Firmicutes_Clostridiaceae Firmicutes_Lactobacillacae Firmicutes_Acidaminococcaeae Firmicutes_Peptostreptococcaceae Proteobacteria_Enterobacteriaceae Firmicutes_Erysipelothricacae |

| Large intestine | Firmicutes_Enterococcaceae Firmicutes_Erysipelothricacae |

Bacteroidetes_Porphyromonadaceae Bacteroidetes_Bacteroidaceae Bacteroidetes_Rikenellaceae Proteobacteria_Enterobacteriaceae Verrucomicrobia_Verrrucomicrobiaceae |

| Small intestine | Firmicutes_Erysipelothricacae Firmicutes_Clostridiaceae |

Actinobacteria_Coriobacteriaceae Bacteroidetes_Porphyromonadaceae Bacteroidetes_Bacteroidaceae Cyanobacteria_Chloroplast Firmicutes_Lachnospiraceae Proteobacteria_Enterobacteriaceae Proteobacteria_Xanthomonadaceae Verrucomicrobia_Verrrucomicrobiaceae |

Taxa are presented as Phylum_Family. Pre-FMT refers to mixed stool specimens obtained from patients with recurrent HE who were given broad-spectrum antibiotics in preparation for fecal microbial transplant (FMT), whereas post-FMT refers to specimens collected from the same individuals 15 days after receiving an FMT enema from a donor enriched with Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae. Higher in one group indicates lower in the group it is being compared to on LEFSe.

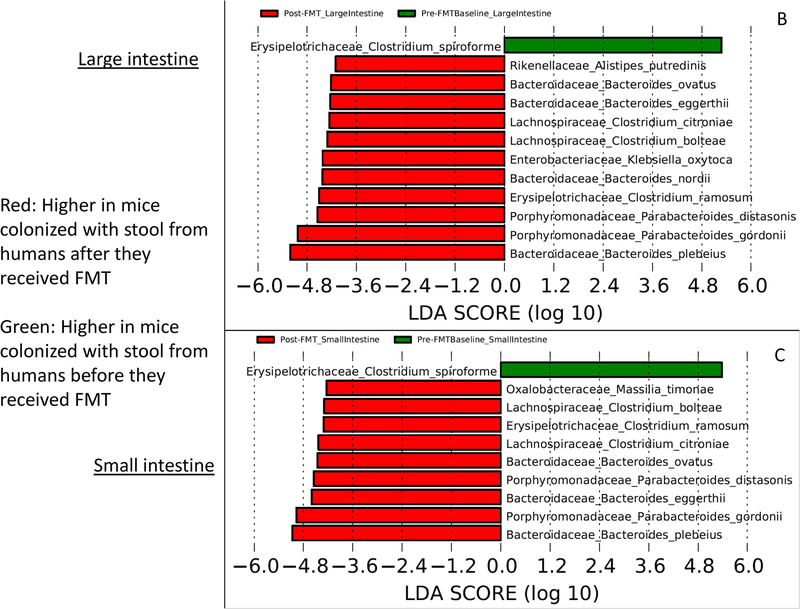

FIG. 5.

Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) comparisons of microbiota at the species level using QIIME2. x axis shows the score that differentiates between the two groups being compared. A higher LDA toward one color indicates that taxon is higher in that group and lower in the group it is being compared to. (A) Comparison between pre-FMT human donor stool (red) and post-FMT human donor stool (green). (B) Comparison between large intestine of mice colonized with pre-FMT donor stool (green) and post-FMT donor stool (red). (C) Comparison between small intestine of mice colonized with pre-FMT donor stool (green) and post-FMT donor stool (red)

When mice were colonized with these human stools, these changes were reflected in the small intestinal microbiota more so than the large intestine with higher Lachnospiraceae, Enterobacteriaceae, and Bacteroidaceae post-FMT (Table 2). This was similarly found at the species level with higher Clostridial spp. and species that were greater in the donors post-FMT compared to pre-FMT small intestine and large intestine (Fig. 5 B,C).

Discussion:

Our results demonstrate that differential colonization of GF mice with stools from healthy controls versus patients with cirrhosis with or without FMT is associated with changes in brain inflammatory expression. The colonization of GF mice with stool obtained from patients with HE after antibiotics results in greater brain inflammation compared to those mice that received feces obtained after successful FMT. These changes in brain inflammatory expression after FMT were not seen to the same extent using GF supernatants, signifying that transferred microbiota mediated the neuroinflammation.

An altered gut-brain axis is important for the development of HE in cirrhosis. Changes in liver function and altered gut microbial composition result in brain dysfunction. Our results demonstrate that expression of certain genes involved in inflammatory response, such as cytokine IL-1β and chemokine MCP1; markers of microglia and active macrophages, such as IBA1; and markers of astrocytes, such as GFAP, was increased in the frontal cortex of conventional cirrhotic mice as compared to conventional controls.(8, 17) These markers of inflammation were also augmented in the frontal cortex of GF cirrhotic mice as compared to GF control mice. Considering that these four markers of immune activation were also increased in GF mice colonized with stool from patients with cirrhosis, together our findings provide evidence linking cirrhosis-associated dysregulation of gut microbiota to frontal cortical inflammation.

Although not as striking as inflammatory markers, we observed similar results with genes involved in neuronal synaptic plasticity, particularly NeuN, BDNF, and GABRAB1.(18, 19) Importantly, these effects of gut microbiota transplantation on expression of markers of inflammation were recapitulated in GF mice receiving entire stool material from cirrhosis patients prior to FMT. However, the impact of transfer from cirrhosis patients to GF mice on frontal cortex markers of neuroinflammation was not observed after transfer of feces from healthy donors. This shows how manipulation of microbiota-gut-brain axis communication may potentially change the onset of neuroinflammation in patients with cirrhosis. Considering that this important difference between pre-FMT and post-FMT donor material was not observed when GF mice received sterile supernatant from the same donor material (either pre-FMT or post-FMT), these data also suggest that additional work is needed to unravel the molecular mechanism by which specific taxa from cirrhosis patients positively and negatively affect cortical neuroinflammation. The translational significance of this finding is high considering the fundamental role of the frontal cortex in processes, such as cognition, perception, sensorimotor gating, and mood.

Our results demonstrate that the mouse brain is sensitive to changes in the gut microbiota composition with respect to inflammatory expression; microglial, glial, and neuronal activation; and GABA signaling. These multimodal changes have been shown to impact the pathogenesis of HE in humans and in animal models of cirrhosis.(6, 20–22) In these animal models and humans, hepatic inflammation is present, which could contribute to the brain inflammation and can often serve as the trigger for development of HE.(23) In our study, we determined that stool from patients with cirrhosis could induce cortical neuroinflammation and microglial and glial activation in GF mice that was comparable to that seen in conventional cirrhotic mice in the absence of significant liver injury. Interestingly, these brain changes were significantly worse than that induced by stool from healthy human controls, which defines that this is not simply a nonspecific result of introducing microbiota into GF mice.

The relative contribution of the liver toward the altered gut-liver-brain axis in cirrhosis is important to delineate because each of these organs are affected simultaneously in humans. Comparing intestinal microbiota from conventional cirrhotic mice after CCl4-induced hepatic injury with Cirr-Hum mice, we found that Cirr-Hum mice had a relatively higher abundance of potentially beneficial taxa belonging to Bifidobacteriaceae, Lachnospiraceae, and Ruminococcaceae and lower potentially pathogenic Streptococcaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, and Porphyromondaceae.(1, 24) This indicates that continuing liver dysfunction or cirrhosis, which was present in the conventional cirrhotic mice, has the potential to worsen the gut milieu over and above that found when stool was simply transferred from a donor into a mouse without cirrhosis. This was further demonstrated when the intestinal microbiota of conventional cirrhotic mice were compared to conventional healthy mouse controls. Microbial families associated with poor outcomes, such as Enterobacteriaceae, Streptococaceae, and Staphylococcaceae, were higher, and those associated with benefit, such as Lachnospiraceae and Bifidobacteriaceae, were lower in cirrhotic mice compared to controls.(1, 25–27) Despite these bacterial changes, the relative impact on the brain inflammation in Cirr-Hum mice was like conventional cirrhotic mice. This was not the case when neuronal inflammation, GABAergic expression, and BDNF analysis were performed. NeuN/Fox3 and GABRAB1/G1 signaling were higher in conventional cirrhotic mice compared to GF mice colonized with stools from any donor. NeuN/Fox3 is a well-recognized marker of post-mitotic neurons and is involved in pathways related to neuronal circuit balance, neurogenesis, and dendritic spine density(28). GABRAB1 and G1 receptors are associated with older age and alcoholism in humans and animal models.(29–31) Our results demonstrate the need for liver disease to be present to induce GABRAB1 and G1 and neuronal expression changes in the mouse brain, regardless of gut microbiota composition, and shed light on the multifaceted impact of these alterations.

On the other hand, there was a significant increase in BDNF mRNA expression, which was higher in the brains of Ctrl-Hum compared to Cirr-Hum or any of the conventional mice. BDNF is a neutrotrophin that is important for neurogenesis, supporting memory and learning and mediating the beneficial impact of exercise on the brain.(32, 33) The relative increase of BDNF in Ctrl-Hum compared to Cirr-Hum is likely another reflection of the beneficial impact of certain types of gut microbiota on brain function, which was enhanced by the absence of cirrhosis in the GF recipients. This was supported by the trend toward BDNF expression in cirrhotic mice compared to controls, regardless of the conventional and GF state. These findings indicate that the beneficial microbiota may modulate these changes by not only reducing inflammation but by potential neurotrophic mechanisms.

Trials of gut microbial modification in patients with cognitive impairment and HE in cirrhosis have been largely successful.(5, 34) Use of medications, such as lactulose and rifaximin, are mainstays in HE therapy.(35, 36) However, a substantial proportion of HE patients recur and have evidence of persistent cognitive impairment despite this standard of care.(35, 37, 38) The gut milieu of this population is also adversely affected by multiple antibiotic courses that are often prescribed.(39) Our human trial demonstrated a short-term and long-term improvement in cognitive function after antibiotics and FMT, which was not seen in the group that received only standard of care.(9, 40) Therefore, our translational results of the pre-FMT and post-FMT stool and supernatant analysis on brain inflammatory expression in GF mice is a highly relevant approach to explore mechanisms and eliminate clinical variables.

We found that mice administered pre-FMT stool developed significantly greater cortical inflammatory and microglial activation expression compared to those given stools from patients with cirrhosis post-FMT, which could mimic human cirrhosis whose HE worsens with inflammation, infections, and antibiotic use.(41) The use of antibiotics in the pre-FMT period was associated with higher Enterococcaceae and Streptococcaceae in the stools.(42) Because the healthy FMT donor was enriched in Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae, we found a higher relative abundance of these bacterial families and constituent species post-FMT in the mixed stool from post-FMT material.(9) This was accompanied by higher potentially beneficial Lactobacillaceae and Clostridial spp.(43) The higher Enterobacteriaceae is likely a response to reconstitution of the microbiota after antibiotics in the pre-FMT period because there was no accompanying inflammation in the liver or the brain in these patients.(44) The human FMT profiles were largely reflected in the post-FMT intestinal lining with greater potentially beneficial taxa and Enterobacteriaceae with lower Enterococcaceae.(44) A criticism of the human study was that, ultimately, the role of pre-FMT antibiotics alone vis-à-vis FMT on brain function could not be separated. Our findings, with greater brain inflammation and microglial activation after antibiotics received by the human donors that is improved significantly post-FMT, demonstrates that the FMT is the likely reason behind the brain function improvement rather than antibiotics and FMT together.

It is also interesting that the small bowel changes reflected the FMT-associated changes better than the colon. This could reflect the gavage route of colonization. We used the gavage approach since this is the broadly accepted and validated way to transfer human fecal material to mice(45). The advantage of oral gavage administration is that larger volumes can be administered with more reliable retention than by enemas. Prior studies have shown the engraftment to be stable and reflective of the human donor, and only a small minority of strains are lost(46). This could also be because the small bowel is a major interface between microbiota, intestinal barrier integrity and local inflammation in cirrhosis(47). In humans, recent studies in liver disease using FMT from the oral capsular and naso-jejunal route have shown beneficial outcomes and improvement in small intestinal barrier and dysbiosis, indicating that this route could be relevant in cirrhosis(48, 49).

The association of Verrucomicrobiaceae with its major constituent Akkermansia is interesting. This family was higher in pre-FMT human donor material but was increased in the intestinal linings of the post-FMT mice. Akkermansia is associated with a beneficial impact on the intestinal barrier integrity in several studies in conditions such as alcoholic hepatitis.(50) This family was also higher in control compared to cirrhotic mice. Further studies are needed to determine whether the relatively higher Verrucomicrobiaceae in the pre-FMT stool may be a compensatory mechanism or a response to antibiotics. However, it is likely that the post-FMT increase in relative abundance reflects the overall beneficial milieu that is seen in this population and is supported by the relatively higher abundance in control compared to cirrhotic mice. Overall, these findings emphasize the important role played by the gut microbiota in alleviating HE with FMT.

Because prior studies demonstrated that sterile supernatants can potentially improve outcomes after FMT in some human studies, we studied sterile supernatants of our pooled pre-FMT and post-FMT human stools in our GF mice.(12) We did not use healthy human donor supernatants in this study. Although cortical IL-1β expression was higher in mice given the sterile supernatant of pre-FMT versus post-FMT donors, this pattern was not sustained across the remaining analyses of the mouse cortex. In most cases, the supernatant-related activation was lower than that of the stools and was statistically similar to levels in the GF controls. These findings suggest that active microbial constituents mediate the positive and negative aspects of altered gut milieu.

Our study is limited by studying activation of frontal cortical brain inflammatory and other changes rather than behavior/cognitive changes in the mice. However, prior guidelines have shown that the major readout of CCl4 mice-related HE is inflammation.(7) We also did not measure systemic cytokines or use pre-FMT pre-antibiotic human samples for colonization of the GF mice. We focused on bacterial constituents rather than their functional products, especially because the sterile supernatants did not show brain inflammatory changes. However, it is quite possible that oral administrations of sterile fecal supernatants do not replicate the continuous luminal production of complex microbial metabolites that occur in mice colonized with resident microbiota. While donors in cirrhosis in the first experiment did not have overt HE on lactulose and rifaximin like the donors in the second experiment, they had minimal HE. Importantly, they were able to induce neuro-inflammation in the colonized mice and these results could be interpreted without potential interference from HE-related therapies.

We conclude that differential human fecal microbial colonization results in different degrees of neuroinflammation and activation of GABAergic and neuronal activation in mice regardless of cirrhosis. Cirrhosis-associated neuroinflammation is more robust compared to that induced by colonization for fecal microbiota from individuals with cirrhosis. However, the reduction in the neuroinflammation by using samples from patients with successful FMT to colonize GF mice shows a direct effect of fecal microbiota independent of active liver inflammation or injury. Taxa related to improved neuroinflammation included Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae, which supports using donors enriched in these constituents in future human FMT studies.

Supplementary Material

Financial Support:

This study was supported in part by VA Merit Review Award I0CX001076 and NIH NCATS grant R21TR002024 to J.S.B; NIH grants R01 DK104893 and R01DK-057543 to H.Z. and P.B.H.;; VA Merit Award I01BX004033 and I01BX001390 to H.Z.; Research Career Scientist Award IK6BX004477 to H.Z.; and NIH grants P40OD010995 and P30 DK034987 and Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation grant 2434 to R.B.S.

Abbreviations:

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CCl4

carbon tetrachloride

- Cirr-Hum

germ-free mice colonized with stools from patients with cirrhosis

- Ctrl-Hum

germ-free mice colonized with stools from healthy controls

- FMT

fecal microbial transplant

- GABA

gamma-aminobutyric acid

- GABRAB1

GABA A receptor, subunit B1

- GABRAG1

GABA A receptor, subunit gamma 1

- GF

germ-free

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- HE

hepatic encephalopathy

- IBA1

ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1

- IL

interleukin

- LDA

linear discriminant analysis

- LEfSe

linear discriminant analysis effect size

- MCP1

monocyte chemoattractant protein 1

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- NeuN/Fox3

neuronal N Fox 3

- NGRRC

National Gnotobiotic Rodent Resource Center

- QIIME

Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology

- VCU

Virginia Commonwealth University

- PHES

psychometric hepatic encephalopathy score

Footnotes

Presentation: Portions of this manuscript were presented orally at the Liver Meeting in San Francisco in 2018.

References

- 1.Bajaj JS, Betrapally NS, Gillevet PM. Decompensated cirrhosis and microbiome interpretation. Nature 2015;525:E1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bajaj JS, Schubert CM, Heuman DM, Wade JB, Gibson DP, Topaz A, Saeian K, et al. Persistence of cognitive impairment after resolution of overt hepatic encephalopathy. Gastroenterology 2010;138:2332–2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riggio O, Ridola L, Pasquale C, Nardelli S, Pentassuglio I, Moscucci F, Merli M. Evidence of persistent cognitive impairment after resolution of overt hepatic encephalopathy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9:181–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bajaj JS, Sanyal AJ, Bell D, Gilles H, Heuman DM. Predictors of the recurrence of hepatic encephalopathy in lactulose-treated patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;31:1012–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, Cordoba J, Ferenci P, Mullen KD, Weissenborn K, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology 2014;60:715–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ochoa-Sanchez R, Rose CF. Pathogenesis of Hepatic Encephalopathy in Chronic Liver Disease. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2018;8:262–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butterworth RF, Norenberg MD, Felipo V, Ferenci P, Albrecht J, Blei AT, Members of the ICoEMoHE. Experimental models of hepatic encephalopathy: ISHEN guidelines. Liver Int 2009;29:783–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang DJ, Betrapally NS, Ghosh SA, Sartor RB, Hylemon PB, Gillevet PM, Sanyal AJ, et al. Gut microbiota drive the development of neuroinflammatory response in cirrhosis in mice. Hepatology 2016;64:1232–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bajaj JS, Kassam Z, Fagan A, Gavis EA, Liu E, Cox IJ, Kheradman R, et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplant from a Rational Stool Donor Improves Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Hepatology 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Mangiola F, Ianiro G, Franceschi F, Fagiuoli S, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A. Gut microbiota in autism and mood disorders. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:361–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang DW, Adams JB, Gregory AC, Borody T, Chittick L, Fasano A, Khoruts A, et al. Microbiota Transfer Therapy alters gut ecosystem and improves gastrointestinal and autism symptoms: an open-label study. Microbiome 2017;5:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ott SJ, Waetzig GH, Rehman A, Moltzau-Anderson J, Bharti R, Grasis JA, Cassidy L, et al. Efficacy of Sterile Fecal Filtrate Transfer for Treating Patients With Clostridium difficile Infection. Gastroenterology 2017;152:799–811 e797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fouts DE, Torralba M, Nelson KE, Brenner DA, Schnabl B. Bacterial translocation and changes in the intestinal microbiome in mouse models of liver disease. J Hepatol 2012;56:1283–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang DJ, Hylemon PB, Gillevet PM, Sartor RB, Betrapally NS, Kakiyama G, Sikaroodi M, et al. Gut microbial composition can differentially regulate bile acid synthesis in humanized mice. Hepatology Communications 2017;1:61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang DJ, Kakiyama G, Betrapally NS, Herzog J, Nittono H, Hylemon PB, Zhou H, et al. Rifaximin Exerts Beneficial Effects Independent of its Ability to Alter Microbiota Composition. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2016;7:e187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim SC, Tonkonogy SL, Albright CA, Tsang J, Balish EJ, Braun J, Huycke MM, et al. Variable phenotypes of enterocolitis in interleukin 10-deficient mice monoassociated with two different commensal bacteria. Gastroenterology 2005;128:891–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kronfol Z, Remick DG. Cytokines and the brain: implications for clinical psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:683–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koleske AJ. Molecular mechanisms of dendrite stability. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013;14:536–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spruston N Pyramidal neurons: dendritic structure and synaptic integration. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008;9:206–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butterworth RF. Hepatic Encephalopathy in Cirrhosis: Pathology and Pathophysiology. Drugs 2019;79:17–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dasarathy S, Mookerjee RP, Rackayova V, Rangroo Thrane V, Vairappan B, Ott P, Rose CF. Ammonia toxicity: from head to toe? Metab Brain Dis 2017;32:529–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Felipo V Hepatic encephalopathy: effects of liver failure on brain function. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013;14:851–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shawcross DL, Davies NA, Williams R, Jalan R. Systemic inflammatory response exacerbates the neuropsychological effects of induced hyperammonemia in cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2004;40:247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahluwalia V, Betrapally NS, Hylemon PB, White MB, Gillevet PM, Unser AB, Fagan A, et al. Impaired Gut-Liver-Brain Axis in Patients with Cirrhosis. Sci Rep 2016;6:26800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Z, Zhai H, Geng J, Yu R, Ren H, Fan H, Shi P. Large-scale survey of gut microbiota associated with MHE Via 16S rRNA-based pyrosequencing. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1601–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qin N, Yang F, Li A, Prifti E, Chen Y, Shao L, Guo J, et al. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in liver cirrhosis. Nature 2014;513:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bajaj JS, Heuman DM, Hylemon PB, Sanyal AJ, White MB, Monteith P, Noble NA, et al. Altered profile of human gut microbiome is associated with cirrhosis and its complications. J Hepatol 2014;60:940–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin YS, Wang HY, Huang DF, Hsieh PF, Lin MY, Chou CH, Wu IJ, et al. Neuronal Splicing Regulator RBFOX3 (NeuN) Regulates Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Synaptogenesis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0164164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu R, Ahluwalia V, Kang JD, Ghosh SS, Zhou H, Li Y, Zhao D, et al. Effect of Increasing Age on Brain Dysfunction in Cirrhosis. Hepatol Commun 2019;3:63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agusti A, Llansola M, Hernandez-Rabaza V, Cabrera-Pastor A, Montoliu C, Felipo V. Modulation of GABAA receptors by neurosteroids. A new concept to improve cognitive and motor alterations in hepatic encephalopathy. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2016;160:88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones JD, Comer SD, Kranzler HR. The pharmacogenetics of alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2015;39:391–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bekinschtein P, Cammarota M, Katche C, Slipczuk L, Rossato JI, Goldin A, Izquierdo I, et al. BDNF is essential to promote persistence of long-term memory storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:2711–2716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delezie J, Handschin C. Endocrine Crosstalk Between Skeletal Muscle and the Brain. Front Neurol 2018;9:698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dhiman RK, Rana B, Agrawal S, Garg A, Chopra M, Thumburu KK, Khattri A, et al. Probiotic VSL#3 reduces liver disease severity and hospitalization in patients with cirrhosis: a randomized, controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2014;147:1327–1337 e1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bass NM, Mullen KD, Sanyal A, Poordad F, Neff G, Leevy CB, Sigal S, et al. Rifaximin treatment in hepatic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1071–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma BC, Sharma P, Lunia MK, Srivastava S, Goyal R, Sarin SK. A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial comparing rifaximin plus lactulose with lactulose alone in treatment of overt hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1458–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Volk ML, Tocco RS, Bazick J, Rakoski MO, Lok AS. Hospital readmissions among patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:247–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bajaj JS, Reddy KR, Tandon P, Wong F, Kamath PS, Garcia-Tsao G, Maliakkal B, et al. The 3-month readmission rate remains unacceptably high in a large North American cohort of patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 2016;64:200–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piano S, Brocca A, Mareso S, Angeli P. Infections complicating cirrhosis. Liver Int 2018;38 Suppl 1:126–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bajaj JS, Fagan A, Gavis EA, Kassam Z, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet PM. Long-term Outcomes After Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Merli M, Riggio O. Interaction between infection and hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol 2015;62:746–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Llorente C, Jepsen P, Inamine T, Wang L, Bluemel S, Wang HJ, Loomba R, et al. Gastric acid suppression promotes alcoholic liver disease by inducing overgrowth of intestinal Enterococcus. Nat Commun 2017;8:837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buffie CG, Bucci V, Stein RR, McKenney PT, Ling L, Gobourne A, No D, et al. Precision microbiome reconstitution restores bile acid mediated resistance to Clostridium difficile. Nature 2015;517:205–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bajaj JS, Kakiyama G, Savidge T, Takei H, Kassam ZA, Fagan A, Gavis EA, et al. Antibiotic-Associated Disruption of Microbiota Composition and Function in Cirrhosis is Restored by Fecal Transplant. Hepatology 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Britton GJ, Contijoch EJ, Mogno I, Vennaro OH, Llewellyn SR, Ng R, Li Z, et al. Microbiotas from Humans with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Alter the Balance of Gut Th17 and RORgammat(+) Regulatory T Cells and Exacerbate Colitis in Mice. Immunity 2019;50:212–224 e214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turnbaugh PJ, Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, Rey FE, Knight R, Gordon JI. The effect of diet on the human gut microbiome: a metagenomic analysis in humanized gnotobiotic mice. Sci Transl Med 2009;1:6ra14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wiest R, Albillos A, Trauner M, Bajaj JS, Jalan R. Targeting the gut-liver axis in liver disease. J Hepatol 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Philips CA, Pande A, Shasthry SM, Jamwal KD, Khillan V, Chandel SS, Kumar G, et al. Healthy Donor Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Steroid-Ineligible Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis: A Pilot Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:600–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bajaj JS, Salzman NH, Acharya C, Sterling RK, White MB, Gavis EA, Fagan A, et al. Fecal Microbial Transplant Capsules are Safe in Hepatic Encephalopathy: A Phase 1, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Hepatology 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Grander C, Adolph TE, Wieser V, Lowe P, Wrzosek L, Gyongyosi B, Ward DV, et al. Recovery of ethanol-induced Akkermansia muciniphila depletion ameliorates alcoholic liver disease. Gut 2018;67:891–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.